Abstract

Women are still significantly underrepresented in management positions, even though they have been able to increase their share to a small extent in recent years. Using arguments derived from signalling theory, this study examines whether organisational family-friendly flexible working arrangements (FFWAs) help to increase internal promotions of women to supervisory or managerial positions and thus reduce the existing gender leadership gap. This effect is investigated using longitudinal data for German workplaces and employees covering 1631 firms and 314,201 employees and fixed effects logistic regression models. The results demonstrate that the implementation of FFWAs improves the chances of internal promotions to supervisory or managerial positions for employees, with women and men benefiting equally. However, if I use a broader definition that also includes highly qualified specialist roles, implementing FFWAs can provide better promotion opportunities for women. Second, FFWAs increase the likelihood of being promoted to managerial positions with reduced working hours, and this effect is slightly stronger for men. Third, surprisingly, no significant positive effects of FFWAs were found on mothers’ promotion of managerial positions. These results show that, even with organisational support, it remains difficult for women to reach management positions and combine family and career at the same time.

Introduction

Empirical labour market research has long pointed to clear gender-specific discrepancies in working hours, remuneration, and career opportunities for women (Ilieva & Wrohlich, Citation2022). Women are still significantly less represented in management positions in all industrialised countries (Blau & Kahn, Citation2013; Eurofound, Citation2018; Kohaut & Möller, Citation2023a) than in their share of employment. In recent years, women in Germany have made some progress in increasing their participation in management positions. However, despite having one of the highest employment rates for women among all OECD countries (OECD, Citation2023a), Germany’s rate still falls in the bottom third across Europe (Destatis, Citation2021). Moreover, organisations can benefit from having more women in management positions. Research has shown that this approach can lead to better organisational results (Harel et al., Citation2003) and help to reduce the gender pay gap (Hirsch, Citation2013).

In the extensive research literature, several factors have been identified to explain the persistent under-representation of women in managerial positions and their lower chances of promotion compared to men. This can be attributed not only to individual factors, such as personality traits, different endowments of human capital, or life course approaches but also to homophily arguments, discrimination theories, or occupational segregation. Institutional influences, such as signalling theory (Spence, Citation1973, Citation1978) or structural theory approaches (Acker, Citation1990) can also be used to explain the gender leadership gap. According to institutional approaches, the reasons for the generation of gender-specific labour market opportunities and social inequalities lie in firm structures. Organisational policies that can reduce gender inequalities are highly important because they can counteract stereotyping and resulting discrimination in hiring, promotion, and pay (Busch-Heizmann et al., Citation2018). Such a personnel policy includes, in particular, measures to improve the compatibility of family and career, as such measures can help to remove barriers to women’s employment opportunities and promote their career advancement. In addition, family-friendly policies in the firm signal to employees with family responsibilities in particular that they are supported in balancing work and private life. In this article, I would like to build on this strand of related research and examine the effect that the implementation of family-friendly flexible working time arrangements in organisations has on the internal promotion prospects of employees, especially women, in management positions.

An increasing number of organisations in industrialised countries, including Germany, have introduced family-friendly measures (Chen et al., Citation2018; Lauber et al., Citation2015; Rohwer, Citation2011). Most of the related research (for an overview, see also Garg & Agrawal, Citation2020) has focused on the determinants of family-friendly HR policies (Bloom et al., Citation2011; Budd & Mumford, Citation2006; Fakih, Citation2014; Gray & Tudball, Citation2003; Joecks et al., Citation2021), access to family-friendly work practices (Bainbridge & Townsend, Citation2020; Chung, Citation2018), job satisfaction (Ko et al., Citation2013), turnover intentions (Chen et al., Citation2018), performance (Guedes et al., Citation2023), pay inequality (Huffman et al., Citation2017), or career interruptions for women (Bächmann & Frodermann, Citation2020). While the impact of flexible work practices on career paths and employee attitudes has been well-studied (Chen & Fulmer, Citation2018; Formánková & Křížková, Citation2015; Leslie et al., Citation2012; Tomlinson & Durbin, Citation2010), only a few studies have explicitly examined the impact of organisational, family-friendly working practices on employee promotions (Fehre et al., Citation2014). Currently, there is limited research on whether implementing family-friendly flexible working arrangements (FFWAs) at the firm-level results in improved promotion opportunities for management positions (Fehre et al., Citation2014; Moore, Citation2020). Therefore, this study contributes to the limited empirical research results on the effects of family-friendly flexible organisational practices on achieving leadership positions. It also examines how FFWAs can help reduce gender inequality by considering the influence of gender, maternity, and part-time work.

This connection is particularly interesting to analyse in the German context. Germany is considered the ideal type of conservative welfare state. In recent decades, the traditional breadwinner and housewife model has changed in all industrialised countries in favour of greater female labour force participation. However, different welfare state orientations lead to very different country-specific policies and patterns of labour force participation, especially among women (Joecks et al., Citation2021). Germany is considered a classic representative of a model that still promotes a traditional division of labour between men and women (Esping-Andersen, Citation1990) by indirectly promoting and subsidising the unpaid care work of wives (Blome & Fuchs, Citation2017). The majority of women in Germany work part-time, while this is still the exception for most men (Wanger, Citation2020). The legal entitlement to part-time work, which has been enshrined in law since 2001, has also contributed to the expansion of part-time work. In Germany, the male breadwinner model is predominant, with women serving as supplementary earners (Wanger, Citation2020).

Only in the last two decades have reforms been initiated to break up the model of the ‘male breadwinner/female part-time career model’ (Esping-Andersen, Citation1990) to improve the compatibility of work and family and to increase women’s participation in the labour market. With these reforms made to parental leave, German policy is increasingly aiming to steer parents’ career and family preferences towards a more egalitarian division of paid and unpaid work and shorter career breaks (Bünning & Hipp, Citation2022; Samtleben et al., Citation2019; Zimmert & Zimmert, Citation2020). The gradual expansion of childcare in Germany has also significantly increased the employment rate of mothers, their agreed upon and desired weekly working hours (Zimmert, Citation2023; Zoch, Citation2020), and the social acceptance of employment for mothers (Barth et al., Citation2020). In addition, there have been efforts made to increase the share of women in management positions through women’s quotas or voluntary firm agreements and to introduce organisational measures to promote women’s labour market opportunities. By now, however, relatively few firms have implemented such measures (Bächmann et al., Citation2020a); thus, despite various legislative initiatives in recent years, women remain significantly underrepresented on the management floors of private-sector firms (Kohaut & Möller, Citation2023a).

Overall, the current framework conditions in Germany provide contradictory impulses for women’s life plans, leading to a conflict of objectives between starting a family and working. While false incentives in the German tax and transfer system promote the asymmetrical division of labour among couples, family policy reforms are aimed at increasing the scope of employment, particularly among women. In contrast to their US counterparts (Doran et al., Citation2019; Grunow et al., Citation2011), German employees are entitled to generous ‘family-friendly’ support services (Ahrens, Citation2019) that are granted to all employed parents by the state and not by their employers. These regulations include, above all, paid parental leave, statutory part-time entitlements, and paid time off in the event of children falling ill. Countries with generous family policies at the national level can ‘crowd out’ informal care relationships and family-friendly arrangements at the professional and organisational levels (Grunow et al., Citation2011). In Germany, this is reflected in the fact that only a relatively small proportion of firms offer special family-friendly measures that go beyond what is required by law (Bächmann et al., Citation2020a). In comparison to other European countries, German firms do not assign such an important role to the topic of family friendliness (Rohwer, Citation2011), even though its prevalence has increased in recent years (Bächmann et al., Citation2020a).

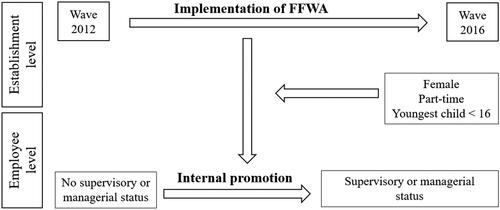

The theoretical contribution of this study to the literature on gender equality practices in the workplace is that, on the one hand, I incorporate organisational theory explanations into the analysis and link the employer level with the employee level. I use arguments from signalling theory (Spence, Citation1973) to examine how the internal promotion prospects of employees in traditional managerial positions change in the German context described here when firms signal FFWAs. Additionally, the analysis examines whether the effect of FFWAs on promotion chances is consistent across all employees or limited to certain groups, such as those based on gender, part-time work, or maternity (refer to ). If family-friendly working time models are designed to address the challenges faced by these groups, then their chances of reaching a management position should increase. If formalised FFWA measures help ensure that management tasks can be carried out despite family obligations, then these positions will become more accessible, especially for women. Especially in times of a shortage of skilled workers, firms can have a strong interest in retaining qualified employees in the long term and enabling management positions beyond the usual ‘ideal worker norm’.

To date, there has been little empirical research on the effect of FFWAs on the promotion of employees to managerial positions. Research indicates that family-friendly policies can help to decrease the gender pay gap (Huffman et al., Citation2017; Zimmermann, Citation2022). However, it remains uncertain how these HR practices affect the achievement of managerial positions. Thus, I provide the first empirical evidence for the effects of FFWAs in the particular German context using an innovative combination of survey and register data based on a German linked employer–employee dataset (Ruf et al., Citation2021a) and individual fixed effect (FE) logistic regression models. This unique dataset makes it possible to control for individual and organisational factors that may influence the promotion of women to management positions. The use of linked data represents a methodological advance compared to previous studies. The main problem with these previous studies is that they use cross-sectional data and do not consider the fact that employees do not gain access to FFWAs by chance. Preferences for certain working time arrangements may result in employees choosing certain occupations or firm positions that may or may not allow access to management positions. This approach may be especially pertinent for women who transition to lower-status jobs or professions after starting a family to balance family and career. While these jobs may provide shorter working hours, they may also offer limited access to management positions. If workers are more likely to self-select into FFWA jobs, then FFWA estimates of worker advancement opportunities would be biased upwards. Therefore, a major advantage of the dataset used is that its panel design allows for causal analysis and considers the self-selection of employees.

Literature review and research hypotheses

FFWAs and management positions

The objective of an HR policy that is family-friendly is to alleviate the tensions that arise from the conflict between work and family life, as such policies are ‘designed to support employees who are faced with balancing the conflicting demands of work, family, and personal time in today’s complex environment’ (Lee & Hong, Citation2011, p. 870). Family-friendly benefits typically fall into two categories: dependent care and flexible working arrangements. This study focuses on the latter, namely, measures that particularly consider the needs of employees with care responsibilities when organising working hours and working places (e.g. flextime, working from home, family-friendly part-time models). In this article, family-friendly flexible working arrangements (FFWAs) are therefore defined as arrangements that make it easier for employees to reconcile their employment with their caring responsibilities and their private life outside the workplace. These arrangements combine flexible working time and work location models with special consideration of family obligations. To be labelled ‘family friendly’, it is therefore not enough to simply offer individual working time arrangements, such as part-time work, working time accounts, or trust-based working hours. Rather, the measures must be embedded in a family-conscious corporate culture. For example, in addition to individual working time instruments, family commitments are accounted for with regard to appointments or meetings at the workplace, arrangements are made for short-term emergency cover, and managers act as role models in their commitment to reconciling work and family life (Ahrens, Citation2019). Demographic change and the associated shortage of skilled workers are driving the importance of family-oriented HR policies (Ahrens, Citation2019; Gauthier, Citation2005; Hammermann et al., Citation2019). This is because a family- and life-phase-conscious HR policy benefits not only employees but also firms in various areas, including increased loyalty, motivation, and retention of employees, greater productivity, and employer attractiveness (Bourhis & Mekkaoui, Citation2010), as well as shorter vacancy periods (Kohaut & Möller, Citation2009; Schein & Schneider, Citation2017). This is also the reason why firms that rely on well-educated, highly qualified women and their continued employment are more likely to offer gender equality measures. Here, the costs arising from the loss of human capital and new hires are the highest (Kohaut & Möller, Citation2009). Therefore, not all employees in a firm have equal access to family-friendly policies. Interestingly, there is no correlation between having dependent children and the likelihood of having access to family-friendly working conditions (Gray & Tudball, Citation2003). The mere fact that family-friendly policies exist does not necessarily mean that they are used (Den Dulk & Peper, Citation2007).

Previous research on the effects of organisational family-friendly work practices has focused in particular on their influence on the satisfaction of workers, on wage inequality, and on career interruptions of women. Family-friendly, flexible working time arrangements in particular have a positive effect on job satisfaction (Artz, Citation2010). Regarding earnings structures, these studies have shown that with bindingly formalised corporate policy practices, the average earnings of women and men increase, while the gender pay gap decreases (Huffman et al., Citation2017; Zimmermann, Citation2022). Organisational family-friendly measures can positively accelerate the return of women to the labour market after the birth of a child (Bächmann et al., Citation2020b; Bächmann & Frodermann, Citation2020).

Structural approaches reveal the reasons for gender-specific labour market opportunities and social inequalities, primarily in organisational structures. Therefore, corporate policies that can contribute to reducing gender inequalities are highly important. Inequalities in occupational status and pay are largely due not only to people’s qualifications but also to firms’ personnel policies. Firms recruit employees, match employees with positions, and structure professional career paths. Firms can use HR policies to promote equal opportunities for men and women in the workplace by counteracting stereotypes and the resulting discrimination in hiring, promotion, and remuneration (Busch-Heizmann et al., Citation2018). Such measures aim to prevent decision makers from acting solely based on preferences and stereotypical assumptions (Reskin et al., Citation1999) by undermining the phenomenon that homogeneous groups—for example, male managers in larger firms—tend to reproduce (Allbright Stiftung, Citation2017).

However, it is not only external discrimination, such as the lack of female role models or an organisational culture based on male stereotypes but also internal discrimination caused by personal or situational barriers that make it difficult for disadvantaged employees to advance (Meeussen et al., Citation2022; Singh et al., Citation2008). Whether a promotion can be realised depends strongly on situational factors, for example, flexibility in terms of time and location. This, especially the aspect of control over one’s work, is seen as a labour resource, which is consistent with the theory of work demands and resources (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2017; Hill et al., Citation2001). According to this theory, working conditions can be divided into two categories: demands, which are associated with stress and burnout, and resources, which are associated with motivation and commitment (Demerouti et al., Citation2001). Resources are likely to have a positive effect, particularly in high-demand work contexts (Bakker et al., Citation2007; Hill et al., Citation2001).

I continue to draw on signalling theory to examine the relationship between FFWAs and the promotion of leadership positions (Spence, Citation1973). Signalling theory is increasingly being used by HR researchers as a theoretical framework for explaining how internal target groups (employees) interpret organisational characteristics and what effects, for example, family-friendly HR practices, have on employees (Bainbridge & Townsend, Citation2020; Begall et al., Citation2022; Veld & Alfes, Citation2017). Employees perceive the observable, tangible results of firm decisions as evidence of underlying, unobservable firm characteristics. Since organisational support and care for employees are not directly observable, employees have less information about these characteristics than do employers. Therefore, if a firm introduces an FFWA, this influences how employees perceive support for work-life balance. An FFWA is a visible formalised HR policy that states that the organisation cares about work-life balance and supports employees in their careers. An FFWA can be a key signal to employees that promotion opportunities are supported even despite caring responsibilities, thus counteracting the risk of foregoing career options. Employees interpret FFWAs as signals that the firm is prepared to support them with existing promotion preferences. From a signalling theory perspective, documented family-friendly work practices are a public signal of the extent to which the organisation supports employees with family responsibilities. These practices have a signalling effect. These findings provide a tangible indication of the firm’s commitment to employees with family responsibilities. The diverse options offered by FFWAs create capacities that allow the professional and family demands of a promotion to be managed simultaneously. In my conceptual model, I assume that observable characteristics in the form of family-friendly HR policies can influence the career progression of employees (see ), as they help to overcome organisational and situational barriers that may prevent promotion to managerial positions.

Against this background, I expect that

Hypothesis 1: If a firm implements FFWAs, this will lead to an increase in the internal chances of employees being promoted to management positions.

The role of reduced working hours

Part-time work is widespread in the German labour market; in 2019, three-quarters of part-time employees were female (Wanger, Citation2020). This is also related to institutional regulations in Germany, as part-time work is promoted by various legal regulations and is also often caused by the predominant half-day school model in Germany. However, despite the enormous prevalence of part-time employment in Germany—the part-time employment rate is one of the highest in an OECD comparison (OECD, Citation2023b)—only a small proportion of part-time employees also work in a management position (Kohaut & Möller, Citation2023a). Although there are significant differences between countries, part-time work among managers is not widespread in Europe. In particular, part-time culture and a gender-egalitarian attitude in a country have positive effects on the realisation of many managers’ wishes for shorter working hours (Hipp & Stuth, Citation2013). Numerous other reasons for the relatively low prevalence of part-time work in managerial positions have been discussed in the literature. Part-time work at the management level is associated with greater coordination efforts and additional costs in the work organisation. In addition, work processes must be reorganised, and information flows and communication within the firm are more difficult. Thus, the lower professional experience of part-time employees results in significant career disadvantages, as productivity is estimated to be lower (Kohn & Breisig, Citation1999). The implementation of part-time models among managers is hampered by time restrictions, expected career losses, and a lack of role models (Durbin & Tomlinson, Citation2014; Gascoigne & Kelliher, Citation2018).

However, such implementation also offers advantages to firms. Kohn and Breisig (Citation1999) cite a disproportionate willingness to perform, productivity advantages, and an increase in attractiveness as an employer to be related to the retention of highly qualified employees. When firms allow part-time management positions, this increases the presence of women in management positions (Ellguth et al., Citation2017); furthermore, since part-time arrangements at the managerial level are rare, employees who exploit them feel committed to the organisation (Tomlinson & Durbin, Citation2010). In particular, Ochsenfeld (Citation2012) highlights the importance of the working time mechanism in advancing to management positions. Thus, time availability conflicts are also a result of work organisation, and these conflicts lie in the design area of the firms. Thus far, for example, while job-sharing models among managers (top sharing) are hardly to be found in German firms, such models would be one of the possible levers to attract more women to management positions (Bellmann, Citation2019).

Full-time employment is a prerequisite for many management positions (Blau & Kahn, Citation2013; Deschacht, Citation2017; Holst & Marquardt, Citation2018), and it is often associated with long working hours and high demands on availability. These working time arrangements are oriented towards the ideal worker norm, where (mostly male) workers are employed full-time and are available to the firm without time constraints due to family or private commitments. These include overtime, atypical working hours, business trips, and relocation (Williams, Citation2000). For example, Lochner and Merkl (Citation2022) show that such flexible job requirements are also important reasons why women are less likely to apply for these jobs. Managers are seen as role models who have to exercise control and steering functions. Therefore, it can be particularly difficult for women with family responsibilities to take on a management role. This is where organisational measures, such as FFWAs come in; they are primarily intended to reduce the time conflicts that arise in certain phases of one’s life due to professional and private double burdens. Management positions with reduced working hours are more important for women than for men. Part-time models at the management level or top sharing can be instruments for women, particularly those who take on positions with leadership responsibility. Especially, the possibility of working from home allows women to work longer hours, as they no longer have to commute (Gärtner et al., Citation2016). This approach also allows for more interesting jobs with more development opportunities (Carstensen, Citation2020, Arntz et al., Citation2019). Reduced working hours combined with mobile working enable employees to adapt their working hours to their needs and better coordinate them with institutional childcare and their partner’s working hours.

The work culture of firms with FFWAs allows them to be more understanding and flexible in responding when employees are struggling with work-life conflicts and when the acceptance of part-time management positions is likely to be greater. In this context, the design of the measures is probably of particular importance, as the effectiveness of the measures depends on the corporate culture. This includes firms questioning traditional gender images and making their corporate cultures more egalitarian. Only if the measures also fit the values of the firm, i.e. if they go hand in hand with an ‘egalitarian’ corporate culture and are also filled with content, do they seem to be able to unfold their effect; otherwise, they tend to function more as a legitimisation façade and can, for example, promote a ‘flexibility stigma’ (Chung, Citation2020; Williams et al., Citation2013).

I therefore assume that it is easier for employees in firms with FFWAs to take on management tasks part-time, as greater flexibility, more innovative working models, and greater acceptance and consideration of family concerns offer more opportunities to take on a management position with fewer working hours. Thus, I hypothesize that

Hypothesis 2: If a firm implements FFWAs, this leads to an increase in the internal chances of employees being promoted to management positions with reduced working hours.

The role of gender and children

When providing FFWAs, firms may have specific target groups in mind, especially individuals with caring-related responsibilities. For most women who take parental leave and return to work part-time, the path to management is very difficult. Especially for highly qualified women, the phase of starting a family clearly overlaps with career-intensive professional development. The birth of children and the return to work part-time thus significantly reduce women’s chances of advancement (Deschacht, Citation2017, Blau & Kahn, Citation2013; Holst & Marquardt, Citation2018). A professional career and family are apparently incompatible for women in the current leadership image. Women in high-management positions more often live in nonmarital relationships and without children in the household. Children have a particular career-inhibiting effect when long working hours are generally needed, but mothers (can) typically only work part-time (Holst & Friedrich, Citation2016). This reflects the professional expectations of managers, who are still oriented towards the realities of men’s lives. For managerial roles in the firm, full-time employment and thus unrestricted availability of the employee is still an important factor regarding recruiting and promoting managers.

Deschacht (Citation2017) shows that 40% of the ‘promotion gap’ between men and women can be explained by gender differences in contractual working hours, working overtime, and occasional late work. When women become mothers, the probability of being in a management position ten years after graduation is halved. For men, on the other hand, parenthood is not associated with career interruption (Ochsenfeld, Citation2012). Family-related career interruptions and the widespread part-time work of women thus contribute decisively to their underrepresentation in management positions.

As women still perform the majority of care work, they should also be the most likely to benefit from FFWA regulations. The firm’s commitment to providing good work-life balance options and enabling customised working time models is highly valued by women who seek to balance family and career. By being able to choose their own working hours and place of work, women can adapt their work to their family responsibilities instead of adapting their family responsibilities to their work.

Flexibility in the timing and location of work, particularly job control, is considered a labour resource, consistent with the theory of work demands and resources (Demerouti et al., Citation2001). Flexibility in terms of time and location is therefore a situational factor that can have a positive influence on promotion (ambitions), especially for women and women with children (Bear, Citation2021). Implementing FFWAs can have a positive impact on women in the workplace by reducing concerns about work-life balance conflicts and boosting career aspirations. Empirical studies show that family-friendly measures in firms and female careers are closely linked (Bächmann & Frodermann, Citation2020). For example, the results of Bear (Citation2021) show that emphasising flexibility and schedule control increase women’s desire for promotion. Therefore, FFWAs should improve the promotion prospects of women with children, as they signal that the position in question can be held at the same time as caring responsibilities. In addition, employers who are committed to a family-friendly policy may also be more open to women in management positions. Regarding the different career opportunities of men and women in relation to management positions, measures taken by firms to promote equal opportunities and formalised HR processes can help to reduce the gender promotion gap and break through the ‘glass ceiling’ for women (Ryan et al., Citation2016) or unravel the ‘labyrinth’ of career advancement (Carli & Eagly, Citation2016).

I therefore assume that gender and, in particular, the presence of children influence the effect of FFWAs on the internal promotion of employees in management positions (see ). I also hypothesise that this interaction is additionally affected by reduced working hours. Overall, these considerations lead to the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3: If a firm implements FFWAs, this leads to an increase in the internal chances of women being promoted to management positions.

Hypothesis 4: If a firm implements FFWAs, this will lead to an increase in the internal chances of women being promoted to management positions with reduced working hours.

Hypothesis 5: If a firm implements FFWAs, this leads to an increase in the internal chances of mothers being promoted to management positions.

Hypothesis 6: If a firm implements FFWAs, this will lead to an increase in the internal chances of mothers being promoted to management positions with reduced working hours.

Methods

Data and sample

To investigate the effect of FFWAs on women’s career opportunities, I analyse German linked employer-employee data (LIAB_LM_9319_v1; for detailed information, see Ruf et al., Citation2021a). For the analyses, I use the LIAB longitudinal model (Ruf et al., Citation2021b), which consists of the IAB Establishment Panel data (Bellmann et al., Citation2020) and is supplemented by individual data on the employees in these panel establishments. These individual data are generated from the Employment Statistics Register of the German Federal Employment Agency and are of high quality as process-produced data as part of the employer’s notification of social security. The Employment Statistics Register is the basic population from which the employment biographies of the person data in the LIAB can be generated. Since civil servants, self-employed individuals, and family workers are not included in the data, the Employment Statistics Register represents ∼80% of the employed population in Germany. With this data, I can follow employees backwards over the 1975–2016 period.

The IAB Establishment Panel (Bechmann et al., Citation2021) is an annual representative survey of almost 16,000 German establishments in both western and eastern Germany that employ at least one employee who is subject to social security contributions. The 2012 and 2016 waves of the Establishment Panel contain questions on various measures taken to promote equal opportunities for women and men, as well as family-friendly working conditions (see Supplemental Online Material, Table S1 and FDZ IAB, Citation2023). In addition, I restrict the analysis to establishments with 50 or more employees since formalised measures are less frequently taken in small establishments due to the relatively high costs; informal agreements can be reached more easily in such situations (Kohaut & Möller, Citation2009). The data collected in the IAB Establishment Panel can be linked to the relevant individual data of the employees in the respective establishment via the establishment number. The LIAB consists of extensive information on the surveyed establishments and the employment biographies of the individuals who worked in these establishments.

Table 1. Promotions to management positions by gender, in the period 2012–2016, shares in percent.

The sample includes employees who are subject to social security contributions (without special characteristics) and marginally employed persons aged between 18 and 64 who worked in the same establishment during the observation period. The data of the Employment Statistics Register of the Federal Employment Agency do not include self-employed managing directors or firm managers, senior civil servants, or family workers with supervisory or managerial functions, as they are not subject to the obligation to register for social security. For the matching and preparation of the LIAB data, the references of Dauth and Eppelsheimer (Citation2020) and Müller et al. (Citation2022) are used. Furthermore, I restrict the sample to persons who were employed in one of the surveyed establishments and who did not change their establishment during the observation period. This approach is advantageous for two reasons. On the one hand, changes in establishment can be observed only to a below-average extent in the LIAB since both the old and the new establishment of employees would have to be included in the sample of the establishment panel; on the other hand, unobservable effects that are due to a change in establishment can be excluded. Finally, the balanced panel data used in this paper contains data on 314,201 employees (thereof 108,495 women) in 1631 establishments. However, changes in the variable ‘managerial position’ were observed for only 7017 employees, of whom 1060 were women.

Measures

Management position

The delimitation and definition of management positions are possible based on different concepts (Körner & Günther, Citation2011). For the analysis in the LIAB, the occupational classification 2010 (KldB2010, cf. Bundesagentur für Arbeit, Citation2010, Citation2019) can be used to identify whether people hold a management position. Occupations with supervisory or managerial responsibilities are each grouped in their own occupational subgroup within the respective occupational group. In addition to these occupations, I also include—following the procedure of the Federal Employment Agency—expert occupations as managers. The dependent variable ‘managerial position’ takes the value 1 if a managerial position as defined above is held and indicates promotions. In addition, the robustness analyses also model additional definitions of management positions and formal promotions.

FFWAs

The IAB Establishment Panel contains different questions on gender equality measures in the firm (see Supplemental Online Material, Table S1). One of these is the question about formalised measures that consider the special needs of employees with care responsibilities in the organisation of working time and place (e.g. flexible working hours, working time accounts, telework, working from home, family-friendly part-time jobs). With respect to this dummy variable (yes/no), the independent key variable ‘family-friendly flexible working arrangements (FFWAs)’ was formed. In addition, other equal opportunity measures are also included in the analysis as control variables, as firms tend to use several measures. These variables are the targeted promotion of women in the establishment, support for childcare, and support for employees with dependents in need of care.

Part-time

The LIAB also contains information on ‘working time’, which distinguishes between full-time and part-time employees but does not provide any information on working hours. The decisive factor here is the relationship between the individually agreed upon working hours and the working hours normally worked in the firm. Employees are considered part-time employees if their working hours are less than the collectively agreed upon or normal working hours of the firm. In the case of the part-time variable, employers may not update the information in the administrative data when working hours are reduced. For example, during the modernisation of the notification procedure for social security in 2011, it became apparent that employers had not always recorded and reported the change of an employee from full-time to part-time in a timely manner (Fitzenberger & Seidlitz, Citation2020). Frodermann et al. (Citation2013) suggest correcting employment post-motherhood that is recorded as full-time work to part-time work if the daily wage is at least 10% lower than that in the last employment spell before motherhood that was recorded as full-time by the same employer. In addition, I correct a full-time job to a part-time job if the daily wage has decreased by more than 40% compared to the median full-time daily wage with the same employer (this is the ratio of the average part-time daily wage to the full-time daily wage).

Children

Information on births is not directly available in the administrative data of the Federal Employment Agency. However, other information indirectly helps to identify births. For example, a notification is given in the employment notification, which is used to calculate a woman’s expected date of childbirth. This date can be calculated based on the reasons for termination or interruption of employment given in the employment notification. This procedure is explained in Müller et al. (Citation2022). This option is not available for men. Children are considered to be in school until the end of the compulsory schooling period (up to the age of 15). The younger the child is, the more important work-life balance arrangements are; however, very few promotions of women with preschool-age children can be found in the data. Due to the number of cases, I therefore consider preschool and school-age children together. A dummy variable for the age of the youngest child up to 15 years is derived from the birth dates of the children.

Control variables

The analyses include additional control variables that reflect the current state of research and account for the fixed effects model used (Bächmann et al., Citation2020a; Bächmann & Frodermann, Citation2020; Ellguth et al., Citation2017; Huffman et al., Citation2017; Zimmermann, Citation2022). To control for differences in women’s previous career steps and possible differences in commitment and attachment to employers, I consider employment history using the following variables: tenure in months and experience in the establishment in years. Empirical studies show that prospects for managerial roles increase with the level of educational resources and work experience (Granato, Citation2017). Tenure also enters the model in quadratic form, as the chance of a managerial position should decrease again with increasing work experience. Previous unemployment experience in months is also accounted for. In addition, I include daily gross income as a relevant aspect. Daily wages can be observed only up to the pension insurance contribution assessment limit valid in the respective year of observation. Above this limit, income is reported at the level of the contribution assessment limit, which is why this variable is right-censored. As employment progresses, the share of right-censored daily earnings increases significantly due to dynamic development; the salary increases associated with promotion, leading to a growing share of managers being above the contribution assessment ceiling. This problem is solved by wage imputation in the preparation of the data. For this purpose, the method explained in Dauth and Eppelsheimer (Citation2020) is used. All the work and earnings history variables listed are taken from the longitudinal register data for the 1975–2016 period.

At the firm level, I control for the proportion of women and skilled employees in the firm. In addition, I include other firm variables that can influence firm decisions. As an indirect indicator of the situation in the firm, workforce fluctuation is used as a measure of employment stability in the firm. Labour turnover is defined as the sum of hiring and departures divided by the average number of employees in the first six months of a year. Labour turnover is an indicator of a firm’s economic situation, as employment is less stable during economic difficulties. The mean tenure of the establishments’ staff, which characterises the degree of job security and the level of firm-specific human capital, points in a similar direction. The mean age of the establishments staff can also be a significant measure of the need for future skilled workers, and such firms could also be more open to women in management positions. Women tend to have less power than men and are generally responsible for fewer subordinates (Kohaut & Möller, Citation2023b). To capture this factor, the manager-to-employee ratio, i.e. the ratio of the number of management positions to the number of employees in the firm, is included in the models. In addition, I include the existence of a works council or staff council as a dummy variable, as this is a firm institution that can influence working conditions in many ways and is an essential part of corporate culture (Ellguth et al., Citation2017). I also consider whether the firm is covered by collective agreements (industry-level collective agreements, firm-level collective agreements, or individual agreements) and whether there have been organisational developments that resulted in the integration of other establishments or establishment units into the firm (incorporations).

One of the reasons given for the underrepresentation of women in management positions is the lack of flexibility associated with their double family burden. However, an FFWA interacts with existing flexible working time arrangements in the establishment; therefore, I include additional working time flexibility variables in the estimates. These include the possibility of using working time accounts, which offer employees a certain amount of flexibility, as well as self-determined working hours, in which employees determine their own working and attendance times without firm control. Both working time arrangements are considered in the models as dummy variables for the flexible organisation of working time.

In addition, I enrich the LIAB data with structural information, such as the childcare rate for individuals under 3 years old at the district level based on the women’s place of residence or the labour market tension, i.e. the ratio of unemployed individuals to vacancies at the federal-state level of the establishment. With these variables, temporary regional fluctuations in the labour market and thus different macroeconomic opportunities can be considered.

The Supplemental Online Material (Table S2) presents descriptive statistics for all variables used in the FE regression models.

Analytic strategy

Linking the data from 2012 and 2016 opens up the possibility of a longitudinal analysis. Since the dependent variables are coded as binary variables, logistic panel regression models based on individual data can be used to estimate the effect of organisational measures on attaining a managerial position (Allison, Citation2009; Torres-Reyna, Citation2007; Wooldridge, Citation2010). I consider only establishments that implemented FFWAs between 2012 and 2016, as well as internal promotions of employees to supervisory or managerial positions, i.e. promotions of employees who were already employed in the establishment before the implementation of FFWAs, and control for changes in the work and salary histories of employees. Thus, FE estimates are also available for nonlinear models; for binary dependent variables, a consistent FE estimate can be made using the conditional maximum likelihood method (Chamberlain, Citation1980). For my study, I estimate FE and control for unobserved heterogeneity at the person level. FE estimators compare the same person over time and therefore rely solely on intraindividual changes. In this way, stable characteristics or traits that do not change over time—which may be either measured or unobserved—can be controlled for even if they are not included in the model. This applies, for example, to characteristics, such as personality, intelligence, or ambition. Consequently, the estimated coefficients cannot be biased by omitted time-invariant differences, as FE models can address unobserved heterogeneity. The FE estimate is based only on those individuals for whom a change in status is observed. Variables with little or no variation, such as education or nationality, are therefore not included in the FE model.

Since the FE estimator eliminates all group-specific constants from the estimation equation, a correct calculation of the FE and thus also of the marginal effects is not possible with logistic panel models (King, Citation2001). Instead, coefficient estimates should be used for analysis and interpretation (Crisman-Cox, Citation2021).

As mentioned above, FE estimators compare the same person over time and are therefore based solely on intraindividual changes. Therefore, FE models can be used to address unobserved heterogeneity, e.g. because of individual differences due to omitted variables. FE models control for all time-invariant characteristics between employees; consequently, the estimated coefficients cannot be biased due to omitted time-invariant differences. The FE estimations, therefore, account for the self-selection of employees, which means selection into jobs with special working time arrangements. The most important advantage of estimating FEs is that causal effects can be identified from observations by examining how the result changes when the same person changes over time from the control to the treatment state.

Results

Descriptive results

According to the LIAB (see Table S3, Supplemental Online Material), 3.4% of female employees and 8.8% of male employees in German establishments were in managerial positions in 2016. The share of part-time managerial positions was significantly lower for men (2.5%) than for women (23.6%). Overall, the share of women in all managerial positions was 19.1%, and the share of women in all part-time managerial positions was 68.7%. As the sample is restricted to firms with 50 or more employees, the proportion of women in management positions was lower, as small firms employ more women, including in managerial positions than larger firms do; therefore, the proportion of women decreases when small firms are excluded.

In addition, I can use the LIAB to distinguish how a management position was achieved within the same establishment. shows the different career paths of women and men in firms with 50 or more employees. For men, management positions are obtained almost exclusively through promotion through full-time employment (97.4%). Although such a classic promotion is also predominant among women (82.9%), the change to a part-time management position plays a significantly greater role than among men. Only 21% of women’s promotions involved mothers with children under 16 years of age.

shows the dynamics of FFWAs. In a total of 12.2% of establishments with 50 or more employees, there was a change in FFWAs between 2012 and 2016. Looking at the direction of these changes, FFWAs were introduced in 6.7% of establishments, and FFWAs were withdrawn in 5.5% of establishments. In a large part of the establishments, there was no change; 5.4% had FFWAs in the firm in both years, while 82.4% had no corresponding regulations. Overall, the importance of FFWAs in firms increased slightly between 2012 and 2016 but remained the exception for larger firms, at 9.2%.

Table 2. FFWA firm types: absence and presence of FFWA in establishments with 50 or more employees, 2012 compared to 2016, shares in percent.

Multivariate results

For my purposes, data analysis is performed in two steps. First, I analyse whether the implementation of FFWAs has different effects on internal promotions to supervisory or managerial positions for women than for men and on promotions during reduced working hours. Therefore, the promotions of all employees are regressed on the FFWA and part-time work variables, and an interaction effect for women is recorded. The interaction variable indicates whether and how the relationship between promotion to a managerial position and FFWAs varies when gender is considered. Although the effects of time-constant variables cannot be estimated in FE models, interaction effects between time-varying and time-constant variables can be modelled (Allison, Citation2009). In the second step, I restrict the analyses to women and examine whether the implementation of FFWAs changes the internal promotion chances of women and, in particular, whether effects for mothers can be identified.

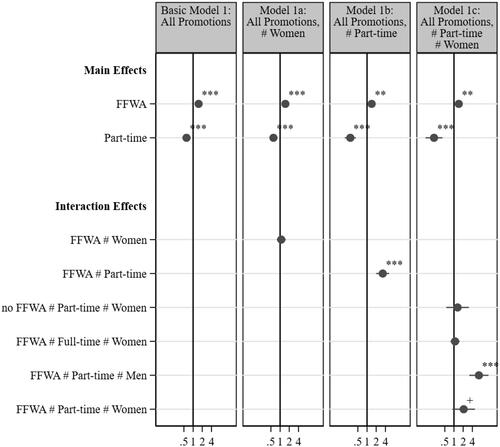

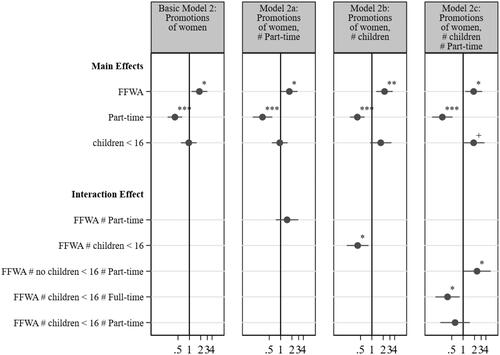

and show the odds ratios (ORs) of the individual FE estimates. These findings indicate the strength of the relationship between two characteristics, namely, how does the probability of a promotion change when a firm implements an FFWA? The figures graphically depict the effects of relevance: odds ratios >1 indicate an increased chance of moving into a leadership position; odds ratios <1 indicate that the chances of promotion are lower for this group. Note that for logistic and other nonlinear regression models, the coefficients should not be compared between different models. If additional independent variables are added to a logistic regression model, then the effects of the variables already included in the model change, even if the additional independent variables are uncorrelated with the previous ones (Mood, Citation2010). The detailed regression results of the coefficients of the base models can be found in Table S4 in the Supplemental Online Material.

Figure 2. FE logistic regression estimates (odds ratios): chances of advancing to management positions (Interaction variables: #women, #part-time). + p < 0.1, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Note: Restricted to employees in establishments with 50 or more employees with valid data in 2012/2016 who are employed in the same establishment, balanced panel. The dependent variable is the advancement to managerial or supervisory positions. N: 14,034 observations of 7017 employees. Table S2 in the Supplemental Online Material for a list of the control variables.

Source: Own calculations using LIAB_LM_9319_v1.

Figure 3. FE logistic regression estimates (odds ratios): women’s chances of advancing to management positions (Interactions: #part-time, # children). +p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Note: Restricted to female employees in establishments with 50 or more employees with valid data in 2012/2016 who are employed in the same establishment, balanced panel. The dependent variable is the advancement to managerial or supervisory positions. N: 2120 observations of 1060 women. See Table S2 in the Supplemental Online Material for a list of the control variables.

Source: Own calculations using LIAB_LM_9319_v1.

, Model 1 shows that, regardless of gender, FFWAs had a positive effect on promotions (OR 1.5) with a 0.001 confidence interval. Therefore, H1 is supported by the results. A p-value above the significance level of 0.001 means that the null hypothesis that FFWAs have no influence on the probability of promotion cannot be rejected with the usual required significance level of 0.001 at most. As many previous empirical studies have shown (f. e. Cetnarowski et al., Citation2013), switching to part-time work significantly reduces the chances of promotion (OR 0.6; p < 0.001), illustrating the effect of reduced working hours on career opportunities. The ‘ideal worker norm’ (Williams, Citation2000) still prevails in firms, and employees are also subject to the ‘flexibility stigma’; i.e. they have career disadvantages in the form of lower promotion prospects if they use flexibility for private reasons. If gender is also considered, no positive interaction effect is found for women (, Model 1a), which indicates that the positive effects of FFWAs are not less or more influential on women than on men. Thus, H3 is not verified by the results. When the results are considered regarding an interaction between part-time employment and FFWAs (, Model 1b), FFWAs are found to have a greater impact on employees reaching a managerial position when this coincides with a move to part-time work (OR 3.3; p < 0.001). Since part-time work is often associated with care responsibilities, this variable also reflects the effects of parenthood or the care of relatives; FFWAs are primarily aimed at this target group. Thus, H2 is confirmed. Notably, the child variable cannot be controlled for in the model for all employees. While information on children and births in the Employment Statistics Register can be derived from different reporting reasons and interruption periods for women according to the approach developed by Müller et al. (Citation2022), there is no corresponding option for men. However, the results from the Netherlands (Stojmenovska & England, Citation2021) show that the impact of parenthood on the probability of working in a managerial position can be fully explained by part-time work when considering all employed women and men.

Although FFWAs are found to have a positive effect on the promotion of managerial positions for both men and women, no statistically significant interaction effect is found for women in particular. This finding suggested that FFWAs are not significantly more beneficial for women than for men in terms of career progression to managerial positions. This is a surprising result, as it contradicts the fact that FFWAs are often marketed as a tool to promote gender equality in the workplace. However, this surprising result can be better understood by considering a broader definition of managerial positions (see also Robustness Analyses and Figure S1 in the Supplemental Online Material). With a broader identification strategy, which includes more highly qualified professional positions and lower management levels, the results shift. While internal promotion opportunities for all employees decrease significantly with the implementation of FFWAs, there is a significant positive interaction effect for women, indicating that FFWAs are particularly effective for women at lower management levels.

In , Model 1c, I include part-time employment in the interaction term with FFWAs in addition to gender. The implementation of FFWAs has a positive effect on promotions to managerial positions with reduced working hours; interestingly, men benefit slightly more from FFWAs than women do. Thus, H4 is not confirmed. As men are generally promoted more often than women and because FFWAs do not increase women’s chances of promotion to a greater extent, it is unlikely that FFWAs will make a difference in the underrepresentation of women in leadership positions and thus contribute to reducing the gender leadership gap in organisations.

In the following models (), I now consider only women and display the results of the effects of FFWAs on women’s promotions; the child variable is now included in these models.

First, the probability of women being promoted to a management position without interaction effects is estimated (, Model 2a). The implementation of FFWAs is found to have a statistically significant effect on the chances that a woman is promoted to an internal managerial position (OR 1.8; p < 0.05) compared to women without FFWAs. However, role conflicts are still prevalent in more highly qualified professions because women who change to part-time jobs still have significantly lower chances of advancing to a management position (OR 0.4; p < 0.001). It should also be emphasised that the results regarding women working part-time are consistent with previous findings (Deschacht, Citation2017; Holst & Marquardt, Citation2018; Hotz et al., Citation2018). The basic model indicates that motherhood does not have a statistically significant effect on the likelihood of being promoted to leadership positions. Instead, parenthood is more likely to be reflected in the negative impact of part-time work (Stojmenovska & England, Citation2021).

As a next step, I insert an interaction term and examine whether FFWAs influence women’s chances of achieving management positions on a part-time basis. Model 2a in shows a corresponding effect. The chances of an advancement into management positions with reduced working hours are not greater when FFWAs are implemented; the interaction effect of part-time work and FFWAs is positive but not statistically significant. For women in highly qualified professions, conflicts between work and family are still significant. Even with FFWAs, female part-time workers still have significantly fewer opportunities for advancement, suggesting that FFWAs alone cannot overcome deep-rooted work culture and societal expectations.

Again, different results emerge when a broader identification strategy is used, including higher skilled professional positions and lower management levels (see Figure S2 in the Supplemental Online Material). For these positions, there are no benefits for women’s internal promotion opportunities with the introduction of FFWAs, and there is a significant negative influence of motherhood, in addition to the negative effect of part-time work. However, there is a positive interaction effect of reduced working hours, suggesting that FFWAs are particularly effective at helping women access lower levels of management in part-time jobs. The supportive work environment provided by FFWAs makes it easier to take on managerial roles with reduced working hours but only at lower hierarchical levels.

FFWAs are intended to make it easier for mothers, in particular, to reconcile their family and career. Therefore, I investigate how their chances of advancement change as a result of the implementation of FFWAs (, Model 2b). However, in contrast to H5, the implementation of FFWAs has no significant impact on maternal advancement opportunities; women with children younger than 16 in the household are less likely to progress. This finding points in the same direction as Grey and Tudball’s (2003) findings that there is no relationship between dependent children and the likelihood of having access to family-friendly working conditions. FFWAs are generally seen as mechanisms for helping working mothers balance work and family responsibilities. However, the results suggest that even with FFWAs, mothers are less likely to be promoted to a managerial position. This raises the question of whether FFWAs are being implemented in workplaces in a way that truly supports working mothers.

In the following, the part-time work and children in the household are included together as an interaction to test how they influence the relationship between advancement and FFWAs. , Model 2c shows in particular a positive effect of FFWAs on the career prospects of women without children (<16) moving into part-time managerial jobs. This suggests that careers beyond the full-time norm are supported but not for mothers. H6 is therefore not verified by the results. Even with FFWAs and reduced hours, reconciling children and careers remains difficult for women. Furthermore, as the wide confidence interval of the interaction terms shows, the number of cases becomes very small due to the strong differentiation, and the individual groups contain only a few observations with changes compared to the previous period.

Robustness analyses

The definition of careers that are reflected in the pure managerial profession is limited. Therefore, as mentioned above, another dependent variable is modelled using a broader definition of the leadership variable. The use of the KldB2010 to identify management roles may underestimate the actual proportion, as the definition of managers or employees in management positions according to this classification is much stricter than survey data, for example, would suggest (Collischon, Citation2023). Therefore, I use a variable for managerial and supervisory positions identified according to Collischon’s (Citation2023) strategy. He also uses survey data to predict management or supervisory positions in the LIAB data. Using this method involves a broader definition of supervisory or managerial positions, which is arguably more consistent with survey data and identifies more people as managers than using only the KldB2010 codes. This identification process is likely to consider highly qualified specialists and lower-level management positions, in particular. According to the modelling results in the Supplemental Online Material (Figures S1 and S2), the variant is used in which Collischon’s model (2023), which includes the 3-digit KldB, predicts a more than 70% chance of becoming a manager. The results vary when management positions with lower status are accounted for, as the explanations in the previous section show.

Promotion to a management position is the classic career path. Focusing solely on the concept of management may be too narrow for a promotion. The world of work has undergone significant changes. Currently, employees are expected to be highly adaptable in terms of their job responsibilities and organisational roles. In addition, tasks are more often processed in the form of projects. This has resulted in positions held by highly qualified employees who often shoulder significant responsibilities but do not have any disciplinary management authority. I therefore model additional possibilities for internal promotions, specifically changing from a lower requirement level to a higher one. This demarcation is used to map formal promotions, which are typically accompanied by an increase in the complexity of activities. This can significantly advance careers and may be associated with a higher salary (Vicari et al., Citation2023). The grades are also obtained from the KldB2010 through the four levels of requirements. These categorise occupational activities according to their qualification requirements into (1) assistants, (2) skilled workers, (3) specialists, and (4) experts. Figures S3 and S4 in the Supplemental Online Material display the model results for promotion to the specialists group (3) and the experts group (4). To summarise, there are still weak positive effects and no gender effects on formal promotion to expert positions when FFWAs are implemented. In contrast, there are weak interaction effects of FFWAs for women regarding formal promotion to specialist occupations. There are also no deviating promotion opportunities for mothers when looking at formal advancements.

Since I want to analyse the effect of the introduction of FFWAs on the internal promotion opportunities of employees in management positions, the logistic FE model is suitable (see also the Methods section). RE regressions are also estimated for verification purposes. To decide between FE or RE models, a Hausman test can be performed where the null hypothesis is that the preferred model is random effects over the fixed effects alternative (Giesselmann & Windzio, Citation2013). Basically, it is tested whether the unique errors correlate with the regressors. The null hypothesis states that this is not the case. The FE specification, which accounts for unobserved, individual-specific effects, is preferred over RE because the F test (with probability > F = 0.000) rejects the null hypothesis of zero individual-specific, unobserved heterogeneity.

The model specification should be particularly dependent on content considerations; logistic regression is therefore particularly appropriate for my dataset (large sample with rare events) (Allison, Citation2015; Von Hippel, Citation2015). Binary choice models can also be estimated using alternative empirical approaches. To enhance the robustness of the results and their sensitivity to different model specifications, further model specifications were therefore made. The Supplemental Online Material (Tables S5 and S6) presents the results of various models, including logistic RE models, linear probability models (LPMs) with fixed and random effects, generalized estimation equations (GEEs), and correlated random effects (CRE) probit models, in addition to the logistic model with fixed person effects. With the exception of the LPM, the results of these analyses point in the same direction, although the statistical significance differs in some cases.

Research into the links between gender equality policies and career outcomes is challenging because, within the data, certain effects are difficult to quantify in terms of time and often emerge only with a time lag. These time lags are compounded by the interdependencies between different policies. According to the LIAB data used for this paper, the presence of FFWAs was queried only at an interval of 4 years. It is therefore not known exactly at what time the FFWAs were introduced (or withdrawn again). The introduction of any HR policy requires a period of implementation, and it may take some time for FFWAs to take full effect and become embedded in the culture. However, to account for period-specific effects of advancement in leadership positions, I estimate event-historical models in additional analyses and consider different FFWA types (see Figures S5 and S6; Table S7 in the Supplemental Online Material). When looking at different FFWA types, a significant impact on the likelihood of reaching a managerial position is found, especially for firms with longer FFWAs. Here, women’s chances of promotion increase after a shorter period over the entire observation period. In firms that reported on FFWAs for the first time in 2016, a positive impact on women’s promotion prospects can especially be found from 2016 onwards, but not in previous years. This indicates that even though the exact date of the introduction of the FFWA was not known, the FFWA started to have an effect in 2016.

Discussion

Women continue to be significantly underrepresented in leadership positions. This study presents new empirical evidence on the question of whether the implementation of FFWAs in firms can increase women’s chances of advancement in leadership positions. For the analysis, I use extensive German linked employer–employee data and FE logistic regression models. In addition to the FFWA, the estimation models also consider various personal, occupational, and firm characteristics, which are intended to cover the explanatory approaches for a transition into a leadership position.

The results initially show that FFWAs give workers an advantage on the path to a managerial position, irrespective of gender. However, the ‘ideal worker norm’ (Williams, Citation2000) is still prevalent, which means that deviations from the full-time norm still bring career disadvantages even in firms with FFWAs and that there is still a need for a more flexible approach to working models. I expected FFWAs to have a positive impact on women’s promotion prospects. However, the results for Germany suggest that FFWAs do not contribute to the advancement of women in management positions. However, when the definition of leadership is broadened to include women in higher skilled professional and lower management positions, FFWAs are found to have a positive effect specifically on the advancement of women.

FFWAs have the potential to have concrete effects on the career opportunities of women and men, especially when interactions with part-time work are considered. However, the empirical analyses do not show concrete advantages for women compared to men. Since women do not benefit more from FFWAs than men, it is unlikely that FFWAs will lead to an increase in the proportion of women in managerial positions, even if increasingly more careers are pursued in working time models beyond the full-time norm. It is positive that men are also increasingly considering such career paths, as this increases the acceptance of such models. However, FFWAs have no effect on mothers’ career progression, even when mothers are not subjected to full-time norms. While FFWAs have an overall positive effect on the careers of employees—including disadvantaged groups of employees, such as part-time workers—I do not find a career effect for mothers; here, the ‘hurdles’ related to holding a management position while reconciling one’s family and work seem to be too high, even with organisational support. Therefore, FFWAs work well for groups that are not immediately considered in the context of FFWAs, namely, women without children in the household and men who move up to leadership positions part-time.

Theoretical and practical implications

I focus on the arguments of signalling theory and structural theory, which form the theoretical framework for the impact of FFWAs at the organisational level. At the employee level, this is linked to the theory of job demands and job resources. Combining both theories, I argue that FFWAs can signal to employees that their employer supports careers beyond the ‘ideal employee norm’ and provides resources for leadership positions. This can make it easier for disadvantaged groups to advance to leadership positions. Various interactions are tested to examine whether the effect of the FFWA on internal promotion opportunities is the same for all employees or whether it is influenced by gender, reduced working hours, or maternity. By using an innovative combination of employee and establishment data from two waves, a longitudinal model can be estimated. This approach enables a causal interpretation of the results and represents a methodological advance over existing studies. Previous studies use cross-sectional data and do not account for that employees do not obtain random access to FFWAs.

The empirical results add to the existing research in significant ways. The hypotheses that FFWAs primarily benefit disadvantaged groups of employees could only be partially confirmed. The results suggest that FFWAs are not significantly more beneficial for women than for men regarding internal career advancement. The results further suggest that mothers do not have increased chances of being promoted even when FFWAs are in place. This raises questions about whether FFWAs are being implemented in workplaces that genuinely support working mothers. For women in highly qualified professions, the conflict between work and family roles continues to be significant. Even with FFWAs, part-time female employees still have significantly lower chances of promotion, suggesting that FFWAs alone cannot overcome deeply ingrained work culture and societal expectations. This runs counter to what might be expected given that FFWAs are often marketed as tools for assessing gender equality in the workplace. However, it is also shown that the effect of FFWAs on women also depends on how the management position under investigation is conceptualised and identified. Only the promotion of women to lower-level management positions is positively affected by FFWAs.

Firms still need to revise their practices and organisational culture to make FFWAs a truly successful instrument for promoting the careers of mothers in particular. Organisational cultural barriers continue to hamper the use of flexible models for promoting management positions. This suggests that additional efforts are needed to ensure that HR practices are more consistently targeted and utilised. If organisational equality measures do not achieve the desired success for individuals, this could be because they are not actually implemented but rather established for legitimacy to the outside world (Busch-Heizmann et al., Citation2018). According to MacDermid et al. (Citation2001), supervisors have a significant impact on the success or failure of flexible models in professional careers. HR practitioners are therefore encouraged to offer their employees individualised, tailored, and innovative models, as these practices are likely to increase employees’ availability and provide career options. These HR practices are important tools for communicating family-friendly values and organisational goals to employees, creating internal culture change. Furthermore, due to the growing shortage of skilled workers and managers in many countries, it is sensible to utilise the potential of well-educated and highly qualified women in the labour market. The growing diversity within organisations has led to a greater need for career paths that enable all employees to succeed rather than just those following an ‘ideal worker career’.

Limitations

Similar to most related research, this study has numerous limitations, despite the novel research findings. A first limitation is that, due to the lack of survey elements on the exact design of FFWA practices, it is not possible to carry out a comprehensive review of these individual instruments. Thus, only the overall effect of the FFWA instrument mixture can be analysed. This means that individual practices that are particularly promising, such as top sharing or mobile working, cannot be identified. Closely related to this is the problem that the self-reported family-friendly measures of the firms used herein may be subject to response bias. For example, individual aspects of flexible working time arrangements, as considered herein, may be disregarded in the measures reported by the firm, which would lead to an underestimation of the effect of FFWAs. On a positive note, the study can control for the availability of working time accounts and self-determined working hours, as well as for part-time employment. These are among the most influential flexible FFWA practices at the employee and organisational levels (Hammermann et al., Citation2019). Although not all working time practices have been checked, I have included some effective working time tools that can remedy some of these weaknesses.

A further limitation is that the dataset does not contain any information on the hours worked by employees but rather only a distinction as to whether they are engaged in full-time, part-time, or marginal employment. Based on human capital theory, it could be argued that a part-time employee working 80% of the hours may experience less career loss than a part-time employee working 50% of the hours. According to a study conducted in Germany, women who work part-time have significantly lower chances of being promoted, regardless of the extent of their part-time work (Cetnarowski et al., Citation2013). This finding indicates that the part-time variable used is suitable for measuring the career disadvantage of reduced working hours.

In addition, other limitations must be addressed. Since I estimate individual FEs, the endogeneity of firms’ decision to adopt FFWAs and thus organisational changes is problematic. Although employees who changed firms during the observation period were not included in the analysis, there may be other unobservable factors that influence the adoption of FFWAs by firms, such as changes in management and a shortage of skilled labour. One way to overcome the endogeneity of firm decisions is to use methods with instrumental variables (Bastardoz et al., Citation2023). These instruments affect FFWAs but not leadership probability. However, these methods cannot be applied to non-linear panel models, such as logistic FE regression (Foster, Citation1997). The model therefore considers various variables that influence corporate decisions, e.g. labour market tension, which can be significant for securing skilled labour if firms introduce measures to appear more attractive as employers and to increase the firm’s image. However, it is possible that variables could not be found for all relevant firm characteristics, even if a lot of establishment information available in the LIAB is used as a control variable to keep the bias of the estimators as low as possible. Thus, despite the exogenous variables on the characteristics of the firm, the problem of endogeneity may not be completely resolved.