Abstract

This multiple case study-based investigation examined teacher language awareness (TLA) for content and language integrated learning (CLIL). This study was carried out in three teacher education programmes in Argentina, Colombia, and Ecuador during two consecutive academic years (2019–2020, 2020–2021), and it sought to explore teacher educators’ (n = 5) and student-teachers’ (n = 58) understanding and practice of (teacher) language awareness for CLIL settings. Data were collected through interviews, online forums, teaching resources (e.g. slides, lesson plans, assignments) and classroom observations (online and face-to-face), and analysed following an interpretivist and inductive approach. Findings show that the participants approached TLA as explicit knowledge about language, and associated it to notions of basic interpersonal skills, general academic language, and subject-specific terminology when TLA was embedded in CLIL. Based on Morton’s (Citation2018) construct of language knowledge for content learning, the paper puts forward a data-driven model of teacher language awareness for CLIL teacher education.

RESUMEN

Esta investigación basada en un estudio de casos múltiples examinó la conciencia lingüística de los docentes (TLA por sigla en inglés) para el aprendizaje integrado de contenidos y lenguas extranjeras (AICLE por su sigla en español). Este estudio se llevó a cabo en tres programas de formación del profesorado en Argentina, Colombia y Ecuador durante dos años académicos consecutivos (2019–2020, 2020–2021), y buscó explorar las actitudes de los formadores de profesores (n = 5) y de los educadores en formación (n = 58) sobre la comprensión y práctica de la conciencia lingüística en entornos AICLE. Los datos se recopilaron a través de entrevistas, foros en línea, así como recursos didácticos (por ejemplo, diapositivas, planificaciones de clases, tareas), y observaciones en aula (en línea y de forma presencial), y se analizaron siguiendo un enfoque interpretativista e inductivo. Los hallazgos muestran que los participantes abordaron el TLA como conocimiento explícito sobre el lenguaje y lo asociaron con nociones de habilidades interpersonales básicas, lenguaje académico general y terminología específica de sus especialidades cuando el TLA estaba integrado en AICLE. Basado en el concepto de conocimiento lingüístico para el aprendizaje de contenidos de Morton (Citation2018), el artículo presenta un modelo basado en datos de conciencia lingüística de los docentes para la formación del profesorado AICLE.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

The increasing use and popularity of content and language integrated learning (CLIL) education in diverse instructional settings has posed new challenges and opportunities in teacher education programmes. In particular, few studies have attempted to explain the specific tenets understood and enacted when transforming teacher language awareness (TLA) processes into concrete pedagogical actions when using CLIL approaches. To address this issue, this multiple case study examined three pre-service teacher education programmes in three South American nations (Argentina, Colombia and Ecuador) using a multi-layered set of data collection methods to explore the teaching perceptions and practices of five teacher educators and 58 student-teachers (i.e. pre-service teachers). The findings showed the importance of educating prospective teachers on CLIL’s components to improve bilingual education endeavours. Participants demonstrated various experiences and understandings regarding teacher language awareness despite the repeated tendency to emphasise explicit (language) knowledge as a core element to develop generic and specialised registers. Our study highlights a four-component framework: (i) exploration, (ii) inductive input, (iii) reflection, and (iv) informed use regarding TLA for CLIL teacher education. The findings of this study suggest the pivotal relevance of educating the next generations of teachers in the integration of language and content in any of its forms, given the high probability that teachers may work in CLIL contexts in the future.

Introduction

Content and language integrated learning (CLIL) is often understood as a dual-focused approach through which learners develop subject-matter knowledge (e.g. science) together with an additional language as instruction occurs in this language. As Sylvén and Tsuchiya (Citation2023) note, CLIL has become an umbrella term which includes different forms or models of implementation depending on contextual factors (e.g. curriculum, goals, material and human resources). In general terms, CLIL models could be placed along a continuum (Met, Citation1999): as an educational approach, often labelled as content-driven CLIL or ‘hard’ CLIL, or as a language teaching approach, i.e. language-driven CLIL or ‘soft’ CLIL (Ball, Citation2016). Content-driven CLIL, usually refers to a content teacher (i.e. a teacher who trained in a subject such as Mathematics) delivering a subject in an L2, usually English. This teacher usually has some level of proficiency in the L2 but may not have formal preparation in language education. Conversely, language-driven CLIL refers to a language teacher (i.e. a teacher trained as an L2 specialist) teaching an L2 (e.g. English as a foreign language) by utilising topics from the school curriculum to contextualise L2 learning. While in theory, the distinction is clear-cut, in practice, there are several variations. For example, an L2 English language teacher may be responsible for subject-matter instruction even when they may not be subject specialists (Lo, Citation2020).

With the heterogeneous spread of CLIL around the world, the concomitant preparation of CLIL teachers has become crucial (Yuan & Lo, Citation2023). In relation to CLIL teacher education, Banegas and del Pozo Beamud (Citation2022) note that such preparation could range from one-off sessions or whole modules in pre-service (language) teacher education programmes, to master’s programmes solely devoted to CLIL (e.g. Pérez-Cañado, Citation2021). Within this diversity, a few studies (e.g. DelliCarpini, Citation2021; Fürstenberg et al., Citation2021; Xu & Harfitt, Citation2019), have examined CLIL teachers’ language awareness to enable CLIL teachers to develop balanced knowledge of content and language (see also He & Lin, Citation2018). Such studies recognise that further efforts and research projects are needed at the level of CLIL teacher preparation with pre-service teachers so that teacher language awareness becomes a concerted intention translated into informed action. In their complex and sometimes contested identity as content-language teachers (Bárcena Toyos, Citation2022; He & Lin, Citation2018), CLIL student-teachers (i.e. pre-service teachers) should be enabled to offer their future learners equal support in both content and language.

Against this backdrop, our focal point is the exploration of teacher educators’ and student-teachers’ understanding and practices of language awareness in three teacher education programmes from Argentina, Colombia, and Ecuador, which include different forms of CLIL teacher education.

Conceptual framework

This study is informed by two central constructs: content and language knowledge for teachers and teacher language awareness, both oriented towards CLIL teacher education.

Content and language knowledge for teachers

The teacher knowledge base continues to be informed by Shulman’s (Citation1987) seminal model which comprises three intertwined areas: content knowledge, pedagogical content knowledge, and general pedagogical knowledge. These are explained below.

Content knowledge (CK) is ‘the knowledge of the specific subject and related to the content teachers are required to teach’ (König et al., Citation2016, p. 321). For example, for content teachers this could be biology, and for language teachers this could include linguistics. However, given the dual focus of CLIL teacher education, this refers to knowledge of both biology and language. Pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) refers ‘subject-specific knowledge for the purpose of teaching’ (König et al., Citation2016, p. 321). This type of knowledge entails developing subject-specific didactics, but for CLIL teachers this includes how to teach biology through an additional language, which should also be pedagogically supported. Authors (e.g. Anglada, Citation2020; He & Lin, Citation2018) agree that in teacher education, particularly in CLIL given its dual aim, CK and PCK involve developing teachers’ language awareness, since language is the main mediation tool through which teaching and learning are constructed (Lantolf, Citation2012). Last, general pedagogical knowledge (GPK) refers to knowledge about education, learners, and the contexts in which teaching and learning occur.

Shulman’s (Citation1987) knowledge base has informed models for the integration of content and knowledge in language teacher education, such as Morton’s (Citation2016, Citation2018) content and language knowledge for teaching (CLKT) and language knowledge for content teaching (LKCT). Since the locus of our study is within teacher language awareness for CLIL, LKCT is described below.

Based on Loewenberg Ball et al.'s (Citation2008) knowledge for teaching model, Morton’s (Citation2018) LKCT is a data-driven construct designed to highlight the types of language knowledge which teachers need to display for successful CLIL implementation. LKCT consists of two sub-domains: common language knowledge for content teaching (CLK-CT) and specialised language knowledge for content teaching (SLK-CT). The first sub-domain, CLK-CT, ‘consists of linguistic competence and knowledge about language that teachers share with others who use the language for a wide range of non-teaching purposes. This includes both everyday non-academic language use and the more subject-specific language required to communicate about the academic content they teach’ (Morton, Citation2018, p. 278). CLK-CT also includes Cummins’s (Citation1980) basic interpersonal communicative skills (BICS) and cognitive academic language proficiency (CALP) as these account for the types of language needed for interactional and academic purposes within (and beyond) the context of schooling.

The second domain, SLK-CT, refers to ‘the unique ways in which teachers use language to represent content knowledge and make it accessible to learners’ (Morton, Citation2018, p. 279). These ‘ways’ are deeply connected to, and shaped by, the specialised knowledge teachers help learners develop within their subjects. To a certain extent, SLK-CT may draw teachers’ attention to the features and roles of disciplinary literacies, for example, the language of history, or the language of literature. Therefore, the relationship between SLK-CT and disciplinary literacies occurs at a pedagogical level as it refers to how language becomes a pedagogical tool to scaffold learning. In sum, Morton’s (Citation2018) LKCT model shows that if teachers are required to use common as well as specialised language knowledge for content teaching, then their own preparation should allow them to develop their awareness of such language knowledge. In this regard, the model has the potential to inform and enhance language teacher education as well as teacher educators’ own language awareness.

Teacher language awareness in CLIL

It may suffice to state that teacher language awareness (TLA) seeks to delineate educators’ professional and explicit knowledge about the language system to reflect on conscious language use in different domains, especially for pedagogical purposes (Andrews, Citation2009). According to Lindahl (Citation2016), TLA entails that teachers should monitor language use based on a three-role model: (i) language users (e.g. teachers’ ability to operate in English as an additional language), (ii) language analysts (i.e. professional knowledge of language systems), and (iii) language teachers (i.e. their ability to support language learning among students) simultaneously.

The interplay between TLA and the teacher knowledge base is complex. Indeed, the explicit mastery of language rules should not be connected only with advanced L2 proficiency (Andrews & Lin, Citation2018; Díaz-Magiolli, Citation2017). It must also include knowledge about the language (subject matter) to make sense of the specific language of learners in context as well as to monitor language production by monitoring self-correction and error correction. However, with CLIL approaches, teacher knowledge should surpass these competencies to comprise expertise in subject areas as well (He & Lin, Citation2018). These additional layers of teacher knowledge include technical know-how about academic language and specialised genres to deal with subject-specific domains.

This complex array of capabilities means that teacher education not only needs to prepare student-teachers to utilise language functionally. Indeed, student-teachers should receive support to break down language patterns in order to explain them pedagogically, and focus on the terminology and discourses associated with the different content-based areas of the curriculum. For instance, there is no guarantee that a language teacher will be able to monitor their linguistic choices all the time as ‘subject matter alone is not sufficient to ensure the effective application of TLA in pedagogical practice’ (Andrews, Citation2009, p. 24). In this landscape, the gap between the language teacher and the content specialist of specific areas needs to be bridged (Fürstenberg et al., Citation2021), and as proposed by Hansen-Thomas et al. (Citation2018), there is ‘the need for increased teacher training in the area of teacher language awareness’ (p. 194). This could be achieved by including teacher preparation courses on, for example, academic literacies and language awareness across teacher education programmes (e.g. Navarro, Citation2021). To illustrate this point, in line with Cammarata and Cavanagh’s (Citation2018) study on immersion teacher educators’ knowledge base, we believe that such a type of teacher preparation requires that teacher educators themselves engage in exploring their own understanding and practices around language awareness.

A few studies have addressed this gap with different nuances in the juxtaposition with CLIL contexts. For example, these have included examining the development of CLIL teacher identity (He & Lin, Citation2018), the demands and challenges behind CLIL teaching practices (Hu & Gao, Citation2021), the teachers’ conceptualisation of language knowledge (Xu & Harfitt, Citation2019) and the need to investigate the initial beliefs about language awareness (Lo, Citation2019). Nevertheless, there is an agreement that there is an ‘urgent need for a greater understanding of the language knowledge they (teachers) need to carry out their everyday teaching tasks’ (Morton, Citation2018, p. 285).

Finally, TLA can also be improved by employing a plurilingual mindset. Teacher educators can use the existing linguistic resources of their students as an asset to scaffold the learning process of the new language - what is known as translanguaging - including the support the L1 can provide (García & Li, Citation2014). In particular, pedagogical translanguaging can provide a suitable foundation (Li & Lin, Citation2019). This refers to a planned educational intervention in which the linguistic units of different languages can be exploited didactically to foster classroom multilingual experiences (Sánchez & García, Citation2022). In the case of CLIL settings, for instance, Lin and Lo (Citation2017) investigated the role of (trans)languaging in knowledge (co-)construction and academic language learning in CLIL science lessons. The findings stressed that teachers need to develop content knowledge in the L2 as well as knowledge about learners’ language use, which can be supported by utilising what students already know from the languages they already speak.

Against this backdrop, two research questions guided this study:

How do teacher educators and student-teachers understand TLA in initial teacher education with a CLIL orientation?

How do teacher educators and student-teachers translate their understanding of TLA into practice in CLIL teacher education?

Methodology

This study followed an interpretivist paradigm (Crotty, Citation1998), particularly adopting a longitudinal multiple-case study design (Yin, Citation2018). According to Duff (Citation2020), ‘case study offers strong heuristic properties as well as analytic possibilities for illustrating a phenomenon in a very vivid, detailed, and highly contextualized ways from different perspectives’ (p. 145). In this investigation, we included three cases of initial teacher education programmes (i.e. undergraduate programmes for pre-service teachers) from three South American countries to illustrate the diversity of CLIL teacher education. Data were collected over the span of two consecutive academic years (2019–2020, 2020–2021). This longitudinal design allowed us to strengthen the trustworthiness (Bryman, Citation2016) of the findings by collecting data at various points in time over two years. The study obtained ethical approval from Author 1’s institution as well as from the institutions in which the cases were located.

The cases

The three cases were selected through convenience sampling as we had direct professional contact with them. These cases were selected because they were prototypical of the types of CLIL teacher education models described in the literature (Lo, Citation2020). The three programmes had CLIL either as a topic, unit of work, or module in their curriculum (). It should be clarified that the study involved all the CLIL-related courses in each programme, and that all the student-teachers in each cohort agreed to participate. Pseudonyms were used to refer to the participants as shows.

Table 1. The cases.

Case 1: Argentina

In Argentina, CLIL as a content-driven approach is usually found in private bilingual schools and it is led by content teachers (e.g. a Geography teacher) who are also L2 users. To a lesser extent, state primary and secondary schools adopt language-driven CLIL (e.g. Banegas, Citation2019), which is led by teachers of English. As described in Banegas and del Pozo Beamud (Citation2022), professional knowledge about CLIL is only found in language teacher education programmes in the form of a module, or a unit or session within a larger module such as Specific Didactics (i.e. additional language pedagogy).

The case was a four-year initial English language teacher education programme offered by a national university. The programme sought to prepare teachers to work in primary and secondary education for teaching general English for communicative purposes. From this programme, a two-term module called English Language Teaching Didactics II was selected as it provided knowledge of language teaching approaches from a CLIL perspective. As part of the module, the student-teachers planned language-driven CLIL lessons.

The module was delivered by two teacher educators, Amaia (module leader) and Belinda. Amaia held a master’s degree in language education and had 20 years of experience as a teacher educator. Belinda had a diploma in online teaching and had 4 years of experience in teacher education. While Amaia led the lecture-component (direct input) of the sessions and designed the follow-up activities, Belinda delivered them. Both led discussion-based activities or supported learning sets (small groups) during sessions. The 20 student-teachers were in their third year of the programme, and only five of them had teaching experience as private language tutors. In their own trajectories, they had not had first-hand experience with CLIL and were not aware of the approach until they enrolled on this module. According to internal exams, their proficiency level oscillated between B2 and C1 according to the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) levels.

Case 2: Colombia

In Colombia, CLIL, usually as content-driven, is implemented from kindergarten to higher education across institutions, primarily among those in the private sector (Corrales & Poole, Citation2023). In terms of who leads such implementation, it could be either content teachers or language teachers, the latter usually in state education (Garzón-Díaz, Citation2021). CLIL teacher education is often found in the form of (1) units/topics within a larger module in a language teacher education programme, or (2) modules in subject-specific (e.g. biology) or language teacher education programmes at undergraduate and master’s level (Corrales & Poole, Citation2023).

The case was a four-year initial natural sciences teacher education programme offered by a private university. The programme prepared practitioners as well as educational researchers for a wide range of environments. CLIL was a distinctive feature of the programme, which was realised through the inclusion of seven modules on English language development (aimed at enhancing student-teachers’ proficiency as well as their future learners’ language proficiency), a module on CLIL delivered in English, and two other English-medium modules, Science Didactics and International Education. In addition, the student-teachers could also enrol for two English-medium disciplinary-oriented elective modules. As the student-teachers would graduate as CLIL Science teachers, they planned content-driven CLIL science lessons.

Two one-term, English-medium modules were part of this study: (1) CLIL led by Carlos, a teacher educator with 30 years of experience in bilingual education, whose first degree was a bachelor’s in English language teaching, and (2) Science Didactics led by Diana, an experienced science educator who identified herself as Spanish-English bilingual and who had experience with teaching science through English in a private school in Colombia. The 15 student-teachers had no teaching experience and only four of them had attended bilingual programmes in primary and/or secondary education. Their level of English was B1 (CEFR).

Case 3: Ecuador

In Ecuador, CLIL has been implemented through language-driven models ‘in the national English curriculum with the goal of enhancing students’ English learning through the use of CLIL pedagogies’ (Argudo et al., Citation2023, p. 434). It is also used in undergraduate programmes such as international relations or tourism. Depending on human resources available at each private/state institution, CLIL can be led by content or English language teachers. In terms of CLIL teacher education, it is often included as a unit within a large module, or as a module in postgraduate programmes.

The case was a four-year initial English language teacher education programme offered by a state university. The aim of the programme is to prepare teachers for teaching English in primary, secondary, and higher education. From this programme, a one-term module called Situated Practice was selected. The module was conceived as the application of theory to practice in terms of language teaching approaches and methodologies. The module had a special emphasis on promoting guided discovery and language noticing (Scrivener, Citation2011); hence, language awareness was a core topic in the syllabus. CLIL was a core topic in the module, and it was mainly addressed as language-driven.

The module was led by Eliana, a teacher educator with 10 years of experience in teaching teenagers and student-teachers. By the end of this study, she completed her doctoral programme in language education. The 23 student-teachers had no teaching experience in formal education, though eleven of them had participated in small-scale initiatives such as summer schools or short courses for children from underprivileged backgrounds. Their level of English was B1 (CEFR).

Data collection

After obtaining written consent for ethical reasons, data were collected through a process which was similar with each case. It included four instruments:

Interviews: Individual interviews were conducted with the teacher educators at the beginning, middle, and end of each academic year. These were carried out online and in Spanish (the participants’ and researchers’ L1) and had a mean length of 32 minutes. Interview questions included: Do you support student-teachers’ language development? Does knowledge about language play any role in your module delivery? What is language awareness to you in the context of your teacher education practice? Do you draw the student-teachers’ attention on how to cater for their future learners’ language learning in a CLIL lesson? If so, how? (or why not?)

Online forums: The student-teachers participated in two fora in which they conceptualised language awareness and proposed ways in which it could be supported with themselves and their learners.

Teaching artefacts: We first collected teacher educators’ slides, lesson plans, and assignments. We then selected those which exhibited an intended focus on language awareness. The samples included below are illustrative of the practices in general within each case.

Online and in-person classroom observations: Each teacher educator was observed between four and six times during the two years depending on the duration of the module they led. The aim of the observations was to record via field notes any teaching strategies, including discourse, and tools the teacher educators used to support language awareness.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis (Cohen et al., Citation2018) was utilised to understand the data which were transcribed and imported into ATLAS.ti version 8 for qualitative data analysis. Thematic analysis involved analysing each data set individually, and it entailed reading and re-reading the data before linking them to pre-conceived codes (e.g. Morton’s Citation2018 model) and emerging codes (e.g. language awareness as disciplinary literacy) which were identified through open coding. Therefore, coding combined deductive and inductive processes. Through axial coding, the initial codes were first arranged into categories and subsequently into themes. These themes were used to combine the diverse data sets. For the purpose of ensuring confirmability, trustworthiness, and transparency (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985), a colleague not familiarised with the study acted as an inter-rater of 50% of each data set. Discrepancies were discussed and the Krippendorff’s alpha-reliability coefficient for multi-valued nominal data (Krippendorff & Craggs, Citation2016) was calculated. The alpha value was .805, which is reasonably close to perfect agreement.

Findings

The findings are presented according to each case, moving from participants’ understandings of TLA to their practices around TLA in CLIL teacher education in each of the contexts investigated. This organisation gives readers the opportunity to understand each case more fully. Readers should be aware that the cases remain mostly separate, with a few cross-references, until the Discussion section, in which we advance a model for TLA in CLIL teacher education.

Understandings from Argentina

The two teacher educators understood language awareness as (a) explicit knowledge about language, and (b) disposition to analyse language in context. Regarding the former, Amaia said,

I view language awareness as my formal and explicit professional knowledge about language, be it English or Spanish, or how languages in general work. Perhaps this is more associated with linguistics, and linked to forms and meanings and functions in context, but as language teaching professionals, that’s the core of our job and role. (Amaia, Extract 1)

It is worth noting that Amaia situates language awareness as a ‘core’ component of the language teacher’s knowledge base which pertains to a teacher’s ability to understand and explain linguistic rules. In her verbalisation of language awareness, she seems to reveal a perspective congruent with the importance of context as a pivotal component of her teaching practice. Belinda holds a similar view adding that:

Language awareness is also about wanting to analyse language. This disposition is about a teacher stopping to think about language in use, how speakers use language in natural settings and so on. Language awareness is about wanting to analyse and explicitly demonstrate one’s knowledge about language, which in the case of CLIL, would be leaned towards understanding how language is used with specific topics and school subjects, so it’d be like academic language awareness. (Belinda, Extract 2)

In turn, 13 student-teachers also equated language awareness to explicit knowledge about language. The rest of the student-teachers (n = 20) emphasised two other aspects: (a) explicit knowledge about the language to support learners’ metalinguistic reflection, and (b) language learning in (in)formal settings. For example, in one forum, Chiara wrote:

When I think of language awareness, I think of our ability to engage in and guide metalinguistic reflection, like identifying there’s a mistake, offering a correct or ‘better’ version, and explaining why it should be X and Y. This is what happens when we ask kids to find mistakes in a text, or when we only give them feedback by underlining a phrase or sentence, encouraging them to look at it more closely. (Chiara, Extract 3)

In relation to language learning in (in)formal settings, one student-teacher wrote:

Language awareness for teachers can also be about reflecting on how languages are taught and learnt in formal as natural settings, for example, at home, or online. I mean learning your L1 or L2 at school or elsewhere. (Graciana, Extract 4)

Practices from Argentina

In the four lessons observed, Amaia provided direct input on TLA in CLIL through tutor-fronted explanation. In particular, the student-teachers were encouraged to use Coyle et al.’s (Citation2010) Language TriptychFootnote1 as a pedagogical tool to organise language support in language-driven CLIL lesson planning. She utilised PowerPoint slides to show key quotes or examples from coursebooks. These examples demonstrated activities which encouraged learners to understand and explain lexico-grammatical rules and textual cohesion (Martin & Doran, Citation2015).

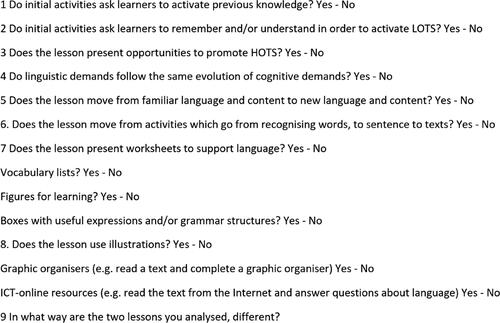

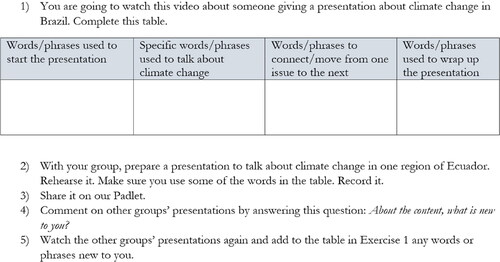

During the other three sessions, the student-teachers worked in groups to analyse lesson plans which featured CLIL as a content-driven or language-driven approach. For example, in Session 3, they analysed a lesson planFootnote2 using a guide ().

shows that Questions 7 and 8 prompted the student-teachers to analyse the ways in which learners were guided through language use in relation to content. Thus, the Argentinian teacher educators practised language awareness by asking student-teachers to analyse and develop (see below) lesson plans which may feature explicit attention to language learning and use, but with no reference to their own TLA, i.e. what language they would require to support learners. During the four observations, the teacher educators enacted TLA by drawing student-teachers’ attention only on how to promote learners’ metalinguistic reflection. Hence, TLA was associated with positioning student-teachers as language teachers but not as language analysts (Lindahl, Citation2016) as the teacher educators expressed in Extracts 1 and 2.

In Session 4, the student-teachers developed a language-driven CLIL lesson plan for an imaginary group of secondary school students. The lesson plan had to feature a topic within the arts as content, particularly the life and work of Argentinian artists. The analysis of the student-teachers’ lesson plans showed that they planned attention to language awareness through the inclusion of inductive learning activities (). The student-teachers sought to direct learners’ attention to form (simple past tense).

The Argentinian case reveals a fracture. On the one hand, the teacher educators and the student-teachers coincided in viewing language awareness as comprising linguistic and pedagogical elements embedded in their knowledge base, as discussed in Anglada (Citation2020). They also recognised the importance of meanings and functions, CALP, the knowledge of specific terminology, learners’ metalinguistic reflection (identification, correction, explanation) and their in-context language learning (Andrews & Lin, Citation2018). However, their practices only exhibited TLA as supporting learners’ identification of discrete forms and explanation of grammar patterns at sentence level. It seems that language awareness in language-driven CLIL was only a learner’s issue, not a teacher’s issue. When mapped against Morton’s (Citation2018) LKCT, the case illustrated traces of CLK-CT only, which means that for the participants language-driven CLIL may be more aligned with BICS than with CALP. This position may be the product of this case being a language teacher education programme which is primarily focused on general English language teaching for communicative/interactional purposes beyond schooling.

Understandings from Colombia

Teacher educator Carlos’s espoused knowledge of language awareness did not differ from that of his counterparts in Argentina, possibly because they shared the same language education background. However, Diana, whose background was in science education, understood language awareness as the ability to identify the features of disciplinary literacies as well as academic language:

I think of language awareness as a teacher’s ability to notice what the language of science is, specific phrases, constructions, key words, and so on. But of course it’s not just that, it’s also about being able to identify common academic language features which appear across the curriculum like formality, hedging, referencing. Science teachers in CLIL need to identify them and then draw their students’ attention to them directly, like showing them, or indirectly, like ‘Do you notice how definitions are constructed in this paragraph or how an experiment is reported?’ (Diana, Extract 5)

The Colombian student-teachers’ understanding of language awareness oscillated between self-correction of form, i.e. accuracy at phrase or word level (e.g. subject-verb agreement, orthography), and ability to use general academic as well as subject-specific language. Regarding the latter, while Diana’s focus was on identifying, her student-teachers’ interest was on learner use. When they were asked about their views on the roles of language in the CLIL science classroom, the 15 student-teachers agreed that while language was an inherent element of teaching and learning science in an additional language, in their case English, they identified themselves as science teachers, not as language teachers, despite the distinctiveness of their teacher education programme. For example, a forum post explained:

The kids should be able to use English correctly, grammar, vocabulary, and academic language for science, but it’s not my job to teach them English. I can help if I notice that something doesn’t look right, or if I want them to use some specific vocabulary, like technical terms, but I don’t know enough English to do that, to make them aware of the language in the discipline. So, my teacher language awareness goes as far as making them aware of writing in science. (Gabriel, Extract 6)

Practices from Colombia

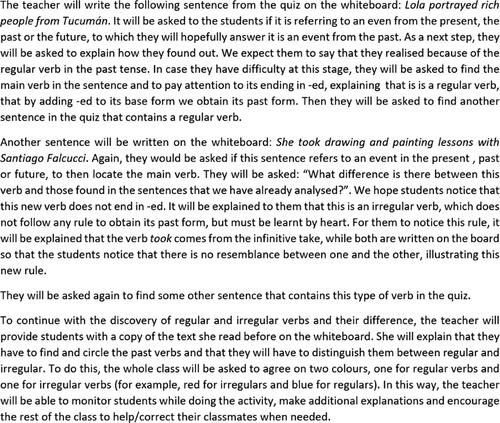

In the CLIL module, Carlos displayed an inductive/experiential approach by inviting the student-teachers to complete different activities such as: (1) read a text about cellular respiration containing lexico-grammatical mistakes, which they had to identify, correct, and explain, (2) watch an instructional video on cellular respiration and discuss what ‘kind of language’ the learners would need to develop to be able to understand the content, (3) re-arrange a jumbled-up text on oxidation and then explain what linguistic/content cues they used to re-organise the paragraphs, (4) listen to a teacher explain the parts of a human cell and use a table to record general academic and content-specific terms, (5) label a representation of a human and an animal cell using both English and Spanish to notice cognates. Drawing on the student-teachers’ answers and reflections on the activities, Carlos introduced the notions of BICS, CALP, coherence, cohesion, and disciplinary literacies, and provided them with a glossary of key terms on language (). The glossary contained not only definitions but also instances of pedagogical translanguaging at word level (Moore, Citation2023). For example, it contained ‘noun’ and ‘sustantivo’ (‘noun’ in Spanish, which was the learners’ dominant language) to support learning as discussed in Sánchez and García (Citation2022). During the lessons observed, the student-teachers would add more terms to the glossary to respond to their own understandings and needs.

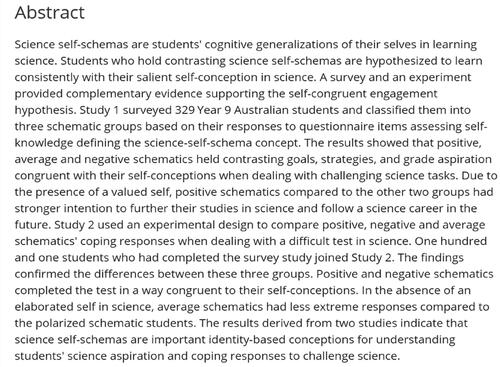

In the delivery of her module on the didactics of science, Diana followed a similar approach to Carlos’ by drawing student-teachers’ attention to textual features. For example, in one session on learner identity in science learning, the student-teachers were asked to read an article on science learning by Ng (Citation2021). Diana first gave the student-teachers a copy of the article abstract () and asked them to answer the following questions in pairs: (1) What verb is used to define ‘science self-schemas’? (2) What is the specific and general language you would need to understand this abstract? (3) How is the abstract organised, what information does it include and in what order? The first two questions illustrate Diana’s view of language awareness (Extract 5) in terms of CALP and subject-specific terminology, which seems to point in the direction of Morton’s (Citation2018) SLK-CT, whereas Question 2 refers to awareness about abstracts as a genre.

Figure 4. Article abstract (extracted from Ng, Citation2021).

During the classroom observations, several of the students struggled with completing the activities because, as some of them said in class, they did not ‘have the words to explain’ or ‘were not good at writing in Spanish or English’. The self-assessment of students’ competences may explain the student-teachers’ position illustrated in Extract 6.

This case shows that both teacher educators’ activities focused on developing the student-teachers’ TLA for CLIL through experiential learning, i.e. they did not start with drawing their attention to their future learners’ language awareness, but to their own. When Diana asked the students to develop similar activities to those designed by Carlos and herself, the student-teachers exhibited a tendency to create the following activities: (1) gap-filling exercises in which content-specific words had been removed and placed in a box above the text, (2) underline cognates, (3) find a video on YouTube on the topic of the lesson and make a glossary of key words either in Spanish or English, and (4) include a table with key terms in English-Spanish at the top of a worksheet.

In the Colombian case, the understandings and practices responded to a focus on content-driven CLIL. Carlos and Diana’s understanding and practice of TLA was congruent, and it illustrates how Morton’s (Citation2018) LCKT model can be enacted in teacher education. In addition, they demonstrated how translanguaging could support the linguistic and pedagogical dimensions of TLA (Andrews & Lin, Citation2018). Notwithstanding, the student-teachers struggled with developing their TLA particularly from a linguistic perspective, i.e. understanding of language rules. However, this finding should be understood considering (1) the programme context, which does not provide specialised knowledge of language teaching and linguistics, and (2) the student-teachers’ identifying themselves as science teachers instead of CLIL teachers.

In their practices, they sought to support learners’ language awareness by providing specialised language knowledge and the use of pedagogical translanguaging (L1 cognates, and definitions) (Sánchez & García, Citation2022). In conclusion, while there was a disposition to develop CLK-CT and SLK-CT, the student-teachers’ LA practices remained at the superficial attention to specific terminology in context.

Understandings from Ecuador

Teacher educator Eliana’s understanding of language awareness did not differ from that of the teacher educators in Argentina and Carlos in Colombia since she also shared the same professional background. In her interview, she underscored that professional knowledge of (L2 proficiency) and about English (subject-matter knowledge) were key in the teacher knowledge base, regardless of whether teacher preparation was orientated towards ELT or CLIL. She added:

There’s always language involved in content learning, and our own TLA should help us draw students’ attention to common as well as disciplinary language, for interaction, for instruction, and so on. (Eliana, Extract 9)

TLA is important for teachers because we can use it to guide students to come up with rules of language use by themselves they derive from examples. Language awareness is not only helpful for grammar or writing, but important for speaking. So, for example, if the students have to make an individual or group presentation they can watch some recorded presentation or take note of pronunciation, pace, intonation, apart from cohesive devices for fluency and organisation. (Melania, Extract 8)

Practices from Ecuador

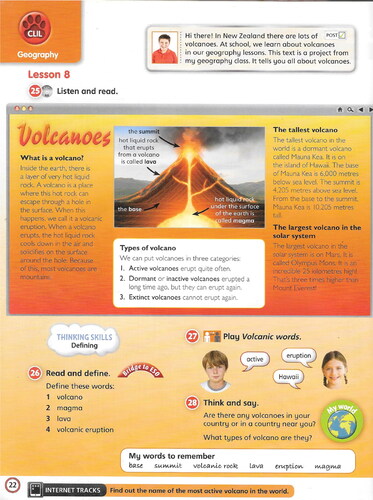

Classroom observations of Eliana’s practice confirmed her interest in developing student-teachers’ understanding of CLK-CT and SLK-CT (Morton, Citation2018). She supported TLA by establishing links to Coyle et al.’s (Citation2010) Language Triptych. Also framed in inductive/experiential learning, she asked the student-teachers to examine a language learning coursebook page () by answering these questions:

(1) What subject-specific words and phrases would you need to teach the students for them to understand the content on volcanoes? (2) Look at activity 28, what language will the learners need in order to complete this activity orally in pairs? (3) What words/phrases can you anticipate they might ask for as a result of their understanding?

The questions are connected to the language of (Question 1), for (Question 2), and through (Question 3) of learning in the Language Triptych. In turn, the questions illustrate that for Eliana, TLA included knowledge of common as well as specialised language for content teaching. Once the students completed the activity, she introduced the Language Triptych and provided different sample activities.

Connected to Eliana’s teaching, the student-teachers designed language-driven CLIL activities. They used topics from social studies to frame language learning. Analysis of their materials and lesson plans indicated that, in line with their understanding of language awareness, activities were developed to support guided discovery primarily for (1) understanding general academic and subject-specific language, and (2) using general and subject-specific language to plan and deliver group presentations. For example, a group of student-teachers designed this activity ():

illustrates that activities 1, 2 (‘Make sure…’), and 5 sought to drive learners’ attention to helpful language related to presentation skills as well as content-related language.

In the Ecuadorian case, the participants understood TLA in both its linguistic as well as pedagogical dimensions. The teacher educator referred to L2 proficiency. We also noted congruent practices, which confirmed the participants’ interest in developing their own CLK-CT and SLK-CT (Morton, Citation2018) so that they could support learners’ development of both general as well as subject-specific language, particularly through identification for use in oral tasks.

Discussion

From understanding to practice

The teacher educators with a language background (Amaia and Belinda in Argentina, Carlos in Colombia, and Eliana in Ecuador) shared an understanding of TLA as explicit knowledge about language, including linguistic and pedagogical components, as previously found in the literature (e.g. Andrews, Citation2009; Andrews & Lin, Citation2018). Despite this shared understanding, their practices differed. For example, the practices by Amaia, Belinda, and Eliana concentrated on providing activities (analysis of lesson plans or coursebooks) that would prompt their student-teachers to design language-driven CLIL activities aimed at developing their future learners’ language awareness. In the case of Colombia, Carlos and Diana (her understanding of TLA as identifying disciplinary literacies differed from everyone else possibly due to her science education background) provided content-driven CLIL activities with a dual purpose: to raise their student-teachers’ TLA and to provide sample activities they could use with their own future learners.

Regarding the student-teachers’ understanding and practices, there were commonalities and differences. In Argentina and Ecuador, the student-teachers conceptualised language awareness as explicit knowledge about language. In addition, the Argentinian student-teachers saw themselves as language teachers who would draw learners’ attention to linguistic forms to support learners’ L2 development. In contrast, the participants from Colombia identified themselves as science teachers and even though they understood language awareness as language in use, their practices concentrated on designing activities aimed at raising future learners’ awareness of disciplinary terminology. Following Lindahl’s (Citation2016) three-role model, while in Argentina, the student-teachers saw themselves as language users (Lindahl, Citation2016), the Colombian and Ecuadorian student-teachers embraced TLA in their roles as as language users and language teachers not only in connection to scaffolding learning but also in relation to their own needs and professional development. Nonetheless, it should be acknowledged that, in the case of the Colombian student-teachers, they demonstrated confidence with SLK-CT but needed further support with CLK-CT (Morton, Citation2018), this latter being strong among their Argentinian and Ecuadorian counterparts.

The differences in understanding and practices synthesised above need to be understood in relation to the different goals and contexts of the teacher education programmes under scrutiny. Notwithstanding, the teaching programme orientation cannot be canvassed as the only factor in divergent TLA practices. The Argentinian and Ecuadorian cases were initial English language teacher education programmes, but only the latter showed the teacher educator’s and student-teachers’ understanding and practice of TLA for CLIL inclusive of CLK-CT as well as SLK-CT. The gap in knowledge about language between content and language teachers (Fürstenberg et al., Citation2021) can be attributed to the depth and breadth of teacher educators’ informed practices. Drawing on the interplay between espoused knowledge and practices, the difference may reside in teacher educators’ degrees of knowledge about TLA and their congruent practices, or their ability to translate declarative knowledge of LA into pedagogical possibilities. This issue not only lends support to Lo’s (Citation2019) call for investigating teachers’ beliefs of language awareness, but it also accentuates the need to examine TLA praxis in teacher preparation, which our study has explored.

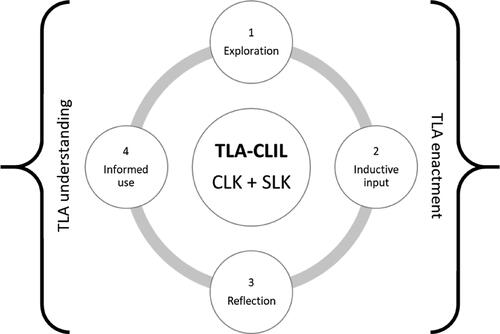

A model of TLA for CLIL teacher education

The pedagogical model proposed in has been informed by our data, Morton’s (Citation2018) LKCT model, and other key notions as mentioned below. The model seeks to support the congruent inclusion of TLA for CLIL teacher education in ways that offer student-teachers the possibility of experiencing awareness-raising in their own teacher education around (1) CLK-CT as illustrated by the student-teachers’ practices from Argentina and Colombia, and (2) SLK-CT as demonstrated by the teacher educators and student-teachers from Colombia and Ecuador.

The pedagogical model necessitates that teacher educators are professionally prepared to engage student-teachers in understanding and using language as a meaning-making system for CLIL.

At the centre of the model of TLA-CLIL, future teachers need to be supported in the development of common as well as specialised language knowledge for content teaching. This support can be achieved by following a pedagogical cycle which is symbiotic to formal understanding of TLA and its enactment both in teacher preparation practices and student-teachers’ practicum. The cycle consists of four stages in this suggested order:

Exploration: Teacher educators invite student-teachers to experience activities that lead them to analyse CLK and SLK within the content of a course such as providing them with a video on for example sociocultural theory and asking them to identify general academic and specific vocabulary, or the textual/multimodal organisation. For example, in our findings, Colombian teacher educators Carlos and Diana involved student-teachers in exploration through experiential activities that promoted content development in tandem with raising their awareness of disciplinary and general academic literacy.

Inductive input: Through the use of examples from the exploration stage and guided questions for personal discovery, the teacher educators introduce knowledge of language use for content teaching. This includes the teaching of rules and language-specific terminology. In our data, all the teacher educators employed sample lesson activities or coursebook analysis to scaffold their student-teachers’ guided discovery. However, there was potential to help student-teachers build stronger connections between knowledge of language and content learning.

Reflection: Drawing on the input provided, student-teachers are invited to reflect on their answers to the exploration stage and propose ways in which their understanding of language use could be enhanced. In our data, the student-teachers from Colombia exhibited a need for enhancing their language use even if they did not see themselves as language teachers.

Informed use: In this stage, student-teachers are invited to act as language users and language teachers through the design of learning events (lesson plans) and materials that contain language awareness-embedded activities for CLIL teaching. The learning events need to promote language appropriateness to accomplish content learning. In our data, all the student-teachers developed lesson plans and activities that sought to raise language awareness in different forms.

Based on our findings, teacher educators and student-teachers may need to develop their TLA, which is a prerequisite, at least concerning teacher educators, for successful TLA in CLIL as suggested in Cammarata and Cavanagh (Citation2018). It can also harness teacher educators’ and student-teachers’ interest, knowledge, and experiences with supporting CLIL by reconciling the linguistic and pedagogical dimensions of TLA through experiential learning. From this perspective, the model stresses that first-hand experience with TLA-CLIL can help student-teachers design lesson plans and materials based on their own reflection as well as research-based knowledge. The model can not only help student-teachers move from implicit to explicit awareness of language support in class (Xu & Harfitt, Citation2019), it can also advance the design of teacher education practices. These can translate declarative knowledge of language, pedagogical translanguaging, and content teaching into situated, praxis-driven knowledge which can assist teacher educators and future teachers with the informed integration of language and content, as discussed in Andrews and Lin (Citation2018), and the prediction of what features of language (Humphrey & Hao, Citation2019) learners may require in CLIL.

Conclusion

This study has proposed a TLA-CLIL model which seeks to capture instances of good practices and strengthen those teaching events which may pose problems such as the disjuncture between declarative knowledge and experiences with TLA at linguistic and pedagogical levels. However, we must recognise that the data leading to the model may not represent the totality of the practices unfolding within and beyond the cases under scrutiny. In addition, due to lack of student-teachers’ availability, they could not be interviewed.

As mentioned above, the proposed TLA-CLIL model implies teacher educators’ preparation on current notions of TLA, CLIL, and pedagogical translanguaging so that their own informed practices can act as pivots on which student-teachers develop their teaching-oriented understanding of language awareness. In this regard, teacher educators investigating their own TLA practices can become a powerful source of professional development that accompanies and encourages student-teachers’ development in relation to CLIL practices which recognise and exploit the inescapable interconnectedness between content and language in bilingual education. Further research can then examine in what ways CLIL teacher educators make sense of the TLA-CLIL model to interrogate and improve their practices, and how their explorations can contribute to a more nuanced understanding of TLA in CLIL teacher education. Also, future studies could examine whether the proposed model might become helpful in other teacher education settings (e.g. a mathematics teacher education programme) beyond CLIL.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Darío Luis Banegas

Darío Luis Banegas is Lecturer in Language Education at Moray House School of Education and Sport, University of Edinburgh (UK). He leads a module on second language teaching curriculum and a research group on intersectionality in language teacher education. He has conducted extensive research on CLIL in South America. He is the lead editor of the Routledge Handbook of Content and Language Integrated Learning.

Rodrigo Arellano

Rodrigo Arellano is a lecturer at Universidad de la Frontera (Chile) and he currently teaches TESOL methodology courses. He holds a PhD in Applied Linguistics from the University of New South Wales (Australia), where he has taught various postgraduate courses in Linguistics. He is interested in Teacher Education, Discourse Analysis and Second Language Acquisition.

Notes

1 The Language Triptych is a pedagogical tool that consists of: (1) language of learning, subject-specific language (e.g. specific terminology, frequent syntactic structures) needed to understand and communicate subject content; (2) language for learning, which refers to transactional/classroom language needed in order to communicate and negotiate meaning in the classroom as learners complete the activities assigned to them; and (3) language through learning, i.e., language that emerges through learners’ knowledge construction and spontaneous need of language as a vehicle for learning (Banegas & Mearns, Citation2023; Coyle et al., Citation2010).

2 Link to access the lesson plan https://www.scribd.com/document/176036051/3%C2%BA-ESO-WEATHER-AND-CLIMATE.

References

- Andrews, S. (2009). Teacher language awareness. Cambridge University Press.

- Andrews, S., & Lin, M. Y. (2018). Language awareness and teacher development. In P. Garrett & J. M. Cots (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of language awareness (pp. 57–74). Routledge.

- Anglada, L. (2020). Reflections on English grammar instruction in EFL/ESL educational settings. In D. L. Banegas (Ed.), Content knowledge in English language teacher education: International experiences (pp. 49–64). Bloomsbury.

- Argudo, J., Fajardo-Dack, T., & Abad, M. (2023). CLIL in educator. In D. L. Banegas & S. Zappa-Hollman (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of content and language integrated learning (pp. 433–445). Routledge.

- Ball, P. (2016). Using language(s) to develop subject competences in CLIL-based practice. Pulso. Revista de Educación, 39(39), 15–34. https://doi.org/10.58265/pulso.5073

- Banegas, D. L. (2019). Teacher professional development in language-driven CLIL: A case study. Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning, 12(2), 242–264. https://doi.org/10.5294/laclil.2019.12.2.3

- Banegas, D. L., & Mearns, T. (2023). The language quadriptych in content and language integrated learning: Findings from a collaborative action research study. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. Advance online publication. 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2023.2281393

- Banegas, D. L., & del Pozo Beamud, M. (2022). Content and language integrated learning: A duoethnographic study about CLIL pre-service teacher education in Argentina and Spain. RELC Journal, 53(1), 151–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688220930442

- Bárcena Toyos, P. (2022). Teacher identity in CLIL: A case study of two in-service teachers. Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning, 15(1), e1516–23. https://doi.org/10.5294/laclil.2022.15.1.6

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods. (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Cammarata, L., & Cavanagh, M. (2018). In search of immersion teacher educators’ knowledge base: Exploring their readiness to foster an integrated approach to teaching. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education, 6(2), 189–217. https://doi.org/10.1075/jicb.18009.cam

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education. (8th ed.). Routledge.

- Corrales, K., & Poole, P. (2023). CLIL in Colombia. In D. L. Banegas & S. Zappa-Hollman (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of content and language integrated learning (pp. 446–460). Routledge.

- Coyle, D., Hood, P., & Marsh, D. (2010). CLIL: Content and language integrated learning. Cambridge University Press.

- Crotty, M. (1998). The foundations of social research: Meaning and perspective in the research process. SAGE.

- Cummins, J. (1980). The cross-lingual dimensions of language proficiency: Implications for bilingual education and the optimal age issue. TESOL Quarterly, 14(2), 175–187. https://doi.org/10.2307/3586312

- DelliCarpini, M. (2021). Developing the C in content and language integrated learning: Teacher preparation that builds learners’ content knowledge and academic language through teacher collaboration and integrated pedagogical training. In C. Hemmi & D. L. Banegas (Eds.), International perspectives on CLIL (pp. 217–238). Palgrave.

- Díaz-Magiolli, G. (2017). Ideologies and Discourses in the Standards for Language Teachers in South America: A Corpus-based Analysis. In L. D. Kamhi-Stein, G. Díaz-Maggioli & L. C. de Oliveira (Eds.), English language teaching in South America: Policy, preparation, and practices (pp. 31–53). Multilingual Matters.

- Duff, P. (2020). Case study research: Making language learning complexities visible. In J. McKinley & H. Rose (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of research methods in applied linguistics (pp. 144–153). Routledge.

- Fürstenberg, U., Morton, T., Kletzenbauer, P., & Reitbauer, M. (2021). “I wouldn’t say there is anything language specific”: The disconnect between tertiary CLIL teachers’ understanding of the general communicative and pedagogical functions of language. Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning, 14(2), 293–322. https://doi.org/10.5294/laclil.2021.14.2.5

- García, O., & Li, W. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Garzón-Díaz, E. (2021). Translanguaging in science lessons: Exploring the language of science in L2 low achievers in a public school setting in Colombia. In C. Hemmi & D. L. Banegas (Eds.), International perspectives on CLIL (pp. 85–106). Palgrave.

- Hansen-Thomas, H., Langman, J., & Farias, T. (2018). The role of language objectives: Strengthening math and science teachers’ language awareness with emergent bilinguals in secondary classrooms. Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning, 11(2), 193–214. https://doi.org/10.5294/laclil.2018.11.2.2

- He, P., & Lin, A. M. Y. (2018). Becoming a “language-aware” content teacher: Content and language integrated learning (CLIL) teacher professional development as a collaborative, dynamic, and dialogic process. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education, 6(2), 162–188. https://doi.org/10.1075/jicb.17009.he

- Hu, J., & Gao, A. (2021). Understanding subject teachers’ language-related pedagogical practices in content and language integrated learning classrooms. Language Awareness, 30(1), 42–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2020.1768265

- Humphrey, S., & Hao, J. (2019). New descriptions of metalanguage for supporting English language learners’ writing in the early years: A discourse perspective. In L. C. de Oliveira (Ed.), The handbook of TESOL in K-12 (pp. 213–230). Wiley.

- König, J., Lammerding, S., Nold, G., Rohde, A., Strauß, S., & Tachtsoglou, S. (2016). Teachers’ professional knowledge for teaching English as a foreign language: Assessing the outcomes of teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 67(4), 320–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487116644956

- Krippendorff, K., & Craggs, R. (2016). The reliability of multi-valued coding of data. Communication Methods and Measures, 10(4), 181–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2016.1228863

- Lantolf, J. (2012). Sociocultural theory: A dialectical approach to L2 research. In S. Gass & A. Mackey (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 57–72). Routledge.

- Lin, A. M. Y., & Lo, Y.-Y. (2017). Trans/languaging and the triadic dialogue in content and language integrated learning (CLIL) classrooms. Language and Education, 31(1), 26–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2016.1230125

- Li, W., & Lin, A. M. Y. (2019). Translanguaging classroom discourse: Pushing limits, breaking boundaries. Classroom Discourse, 10(3–4), 209–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2019.1635032

- Lincoln, Y., & Guba, E. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. SAGE.

- Lindahl, K. M. (2016). Teacher language awareness among pre-service K-12 educators of English language learners. In J. Crandall & M. Christison (Eds.), Teacher education and professional development in TESOL: Global perspectives (pp. 127–140). Routledge.

- Llinares, A., Morton, T., & Whittaker, R. (2012). The roles of language in CLIL. Cambridge University Press.

- Lo, Y.-Y. (2019). Development of the beliefs and language awareness of content subject teachers in CLIL: Does professional development help? International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 22(7), 818–832. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2017.1318821

- Lo, Y.-Y. (2020). Professional development of CLIL teachers. Springer.

- Loewenberg Ball, D., Hoover, M., & Phelps, G. (2008). Content knowledge for teaching: What makes it special? Journal of Teacher Education, 59(5), 389–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487108324554

- Martin, J., & Doran, Y. (2015). Systemic functional linguistics. Routledge.

- McDougald, J. (2023). Teachers’ perceptions, beliefs, and attitudes on CLIL. In D. L. Banegas & S. Zappa-Hollman (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of content and language integrated learning (pp. 255–267). Routledge.

- Met, M. (1999). Content-based instruction: Defining terms, making decisions. NFLC Reports. The National Foreign Language Center.

- Moore, P. (2023). Translanguaging in CLIL. In D. L. Banegas & S. Zappa-Hollman (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of content and language integrated learning (pp. 28–42). Routledge.

- Morton, T. (2016). Conceptualizing and investigating teachers’ knowledge for integrating content and language in content-based instruction. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education, 4(2), 144–167. https://doi.org/10.1075/jicb.4.2.01mor

- Morton, T. (2018). Reconceptualizing and describing teachers’ knowledge of language for content and language integrated learning (CLIL). International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 21(3), 275–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2017.1383352

- Navarro, F. (2021). Más allá de la alfabetización académica: Las funciones de la escritura en educación superior. Revista Electrónica Leer, Escribir y Descubrir, 9(1), 38–56.

- Ng, C. (2021). What kind of students persist in science learning in the face of academic challenges? Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 58(2), 195–224. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21652

- Pérez-Cañado, M. L. (2021). CLIL-ising EMI: An analysis of student and teacher training needs in monolingual contexts. In C. Hemmi & D. L. Banegas (Eds.), International perspectives on CLIL (pp. 171–192). Palgrave.

- Sánchez, M. T., & García, O. (Eds.) (2022). Transformative translanguaging espacios: Latinx students and teachers rompiendo fronteras sin miedo. Multilingual Matters.

- Scrivener, J. (2011). Learning teaching: The essential guide to English language teaching. (3rd ed.). Macmillan.

- Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.57.1.j463w79r56455411

- Skinnari, K., & Bovellan, E. (2016). CLIL teachers’ beliefs about integration and about their professional roles: Perspectives from a European context. In T. Nikula, E. Dafouz, P. Moore & U. Smit (Eds.), Conceptualising integration in CLIL and multilingual education (pp. 145–168). Multilingual Matters.

- Sylvén, L. K., & Tsuchiya, K. (2023). CLIL in various forms around the world. In D. L. Banegas & S. Zappa-Hollman (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of content and language integrated learning (pp. 373–386). Routledge.

- Xu, D., & Harfitt, G. J. (2019). Teacher language awareness and scaffolded interaction in CLIL science classrooms. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education, 7(2), 212–232. https://doi.org/10.1075/jicb.18023.xu

- Yin, R. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods. (6th ed.). SAGE.

- Yuan, L., & Lo, Y.-Y. (2023). CLIL and professional development. In D. L. Banegas & S. Zappa-Hollman (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of content and language integrated learning (pp. 160–176). Routledge.