?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The paper examines one of many actions that civilians employ to resists peacefully armed actors during civil wars: protests. I argue that the costs for mobilizing against armed actors depend on the level of control that armed actors exert in the territory. By examining the civil war in Colombia between 1990 and 2004, I find that civilians protest against the weaker actor to reveal their loyalty to the dominant actor and to prevent the strong side from conducting future violent actions against the population. Protesting works as a costly signal of loyalty. I reveal that non-combatants protest against the stronger actor when both civilians and combatants share the same political ideology. In that circumstance, punishment by the strong combatants is improbable as protesting against them is likely to be interpreted as a renegotiation of the contract or a reminder of its terms. Finally, I show that civilians in contested zones declare themselves neutral and protest against both sides. Non-combatants take advantage of the power contestation to improve their current situation. Any punishment by combatants in contested zones would lead to defection, and citizens protest against both actors knowing that armed actors cannot afford to punish non-combatants for their hostile attitude.

Introduction

OnFootnote1 4 February 2008, thousands of people marched in more than one hundred cities in Colombia demanding that the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) stop its attacks against civilians. This mobilization channeled non-combatants’ anger and dissatisfaction toward the rebel organization (La marcha de la rabia Citation2008). Although citizens were tired of the insurgents’ actions, some sectors began to wonder why people mobilized against FARC instead of the paramilitaries, state forces, or even all sides in the confrontation. Why had people chosen to protest not against the other military organizations, which had all executed similar outrageous actions against the population, but only against FARC?

In the midst of war, civilians develop a broad set of actions to manage their relationships with armed actors. One of these actions is resistance, defined as the opposition to the rule of armed actors. Some of this resistance may be invisible to military organizations, but other actions, such as the protest against FARC, may be perceptible by armed actors (García Durán Citation2005). Scholars analyzing case studies of civilian resistance have reviewed how citizens were able to organize and bargain with armed actors during armed conflicts (Anderson and Wallace Citation2013; EPICA and CHRLA Citation1993; Valenzuela Citation2009; Wilson Citation1992). Noncombatants, for example, can attempt to shape armed actors behavior and convince them to restrict their violence in their community. Despite acknowledging civilian resistance against one or both sides of the confrontation, scholars have disregarded how the target of protests influences the cost-benefit analysis that civilians carry out before they mobilize against armed actors. In this paper, I adopt a strategic framework in trying to understand the conditions under which civilians protest against armed actors and their choice of target selection.

I argue in this paper that civilians are exposed to different risks when they protest against one or both combatants in war. The variance of the risks heavily depends on the level of control that armed actors exert over the territory. When one side is stronger than the other, civilians prefer to mobilize against the weaker side. Protest then becomes a costly signal that civilians use to show their allegiance to the powerful actor and, in turn, prevent future attacks from the dominant force. Civilians could also mobilize against the stronger actor if civilians share the same ideological affinity. Under such conditions, common ideological affinity serves as a signal of loyalty to the strong combatant, and demonstrations then become a mechanism for civilians to renegotiate their contract or remind its terms. In contrast, when neither side holds control over the territory, civilians prefer to mobilize neutrally, demanding the halt of violence from both combatants. In such zones, armed actors should shy away from inflicting any punishment lest civilians seek safety in the arms of the other side. Thus, non-combatants, knowing the vulnerability of the combatants, can utilize contestation as an opportunity to improve their conditions during the war.

This paper proceeds as follows. In the next section, I discuss the dynamics of non-violent resistance in civil wars. Then I define the scenarios in which civilians are more likely to protest. I follow with a discussion of the research design and the results of my empirical analysis. In the last section, I conclude.

Non-Violent Resistance During Civil Wars

In recent years, scholars have highlighted the negative impact of civil wars on non-combatants (Fearon and Laitin Citation2003), reviewing different conditions under which armed actors use violence against civilians (Kalyvas and Kocher Citation2007; Metelits Citation2010; Weinstein Citation2007). Some have studied the strategies that civilians employed to avoid or, at least, mitigate the undesirable consequences of military confrontation (Baines and Paddon Citation2012; Lubkemann Citation2008). This work has basically focused on three different choices open to civilians in civil wars: Citizens can flee and seek a place where they cannot be harmed by armed actors, stay and collaborate with one of the sides in the confrontation, or stay and oppose armed actors (Barter Citation2012; E. Wood Citation2003). Indeed, resistance is one of the most intriguing behaviors in civil wars given that unarmed civilians defy a set of armed actors knowing full well that they can be punished for their defiance.Footnote2

Some acts of resistance are invisible to the combatants (Uribe de Hincapié Citation2009). For example, in the Afghan district of Jaghori, the Hazaras developed an interesting way to resist the strict social regulations of the Taliban without putting themselves at risk. The Hazaras embraced each of the Taliban’s commands while Taliban authorities visited their towns, but followed their own rules in the absence of Taliban supervision (Anderson and Wallace Citation2013). However, civilians can also publicly defy armed actors (García Durán Citation2005). For instance, civilians have created ‘Zones of Peace’ with the aim of bargaining with armed actors. In many cases, these organizations helped convince violent organizations to moderate their behavior toward civilians (Anderson and Wallace Citation2013; Hernández Delgado Citation2004; Wilson Citation1992).

The possibility of reaching such agreements, however, heavily depends on civilians’ capability to overcome their collective action problem (Arjona Citation2016; Kaplan Citation2017). Civilians must be willing to work together despite enjoying the benefits of the struggle without assuming the costs of mobilization. There are three reasons in the literature that explain why civilians are capable of solving this problem: First, communities possessing legitimate and effective institutions before the war began, such as indigenous communities in Colombia, Muslim minorities in Rwanda, or Christian organizations in Mozambique, are better able to coordinate their efforts with the purpose of establishing an agreement with the armed actors (Anderson and Wallace Citation2013; Hernández Delgado Citation2004; Wilson Citation1992). Second, foreign aid distribution through NGOs can empower individuals to take action by providing selective incentives for mobilization (Moreno León Citation2021). Furthermore, NGOs can boost civilian mobilization by using their transnational channels for naming and shaming combatants that hurt civilians (Mahony and Eguren Citation1997; Mampilly Citation2011). Finally, high levels of violence, up to a certain threshold, increase the costs of non-participation and hence induce civilian action (Moreno León Citation2021; Vüllers and Krtsch Citation2020).

One piece is still missing from the puzzle of understanding resistance in civil wars. Civilians choose to whom they address their grievances. Sometimes they mobilize against the state forces. In the regions of El Quiché and Ixcán in Guatemala in 1991, a group of civilians created a set of organizations called the Communities of Population in Resistance that specifically fought the government’s counter-insurgency policy (EPICA and CHRLA Citation1993). In other contexts, civilians confronted insurgents. In 2004, the Nepalese community in Dullu, a small village, carried out a campaign against the Communist Party of Nepal-Maoist. They requested the immediate departure of the guerrillas from their territory (Shah Citation2008). In contrast to the previous options, non-combatants have sometimes declared themselves neutral in the confrontation. That was the case of the Peace Community of San José de Apartadó, Colombia. A group of civilians, with the assistance of the Catholic Church and several NGOs, created an autonomous organization, whose only purpose was to protect its members, and refused to collaborate with either side of the conflict (Valenzuela Citation2009). If the targets of these protests differ, when do non-combatants find it in their best interest to mobilize against one armed actor rather than another? When does neutrality become the best option for resisting military organizations? And more importantly, can this selection process help civilians facilitate their collective action problem?

When Selection Becomes Important

Civil wars are marked by blurred lines between territories controlled by different factions and the integration of supporters into the general populace. In such a context, armed groups often resort to violence to deter disloyalty and punish dissidence among civilians. The success of this strategy hinges on the precise identification of enemy supporters; failure to do so may lead civilians to seek protection from adversaries. A key challenge in these situations is the information asymmetry between armed actors and civilians. Armed groups employ various methods to bridge this gap, though none are entirely foolproof. Armed actors may depend on informants from within the civilian population. However, this approach is unreliable as informants could manipulate information for personal motives (Kalyvas Citation2006). To address the risk of wrongly punishing innocents, military organizations sometimes analyze voting patterns to deduce community allegiances (Balcells and Steele Citation2016).

Armed groups, however, are not the only entities striving to overcome informational asymmetry in civil wars. Civilians also play a proactive role, as evidenced by their actions in Peru during the 1990s. There, civilians joined counter-insurgent groups to demonstrate support for state forces, aiming to prevent indiscriminate military actions against them (Schubiger Citation2021). This example underscores that civilians are not merely passive players in the conflict; they actively engage in strategies to safeguard themselves and their communities. However, understanding the decision-making process that leads civilians to take such proactive steps is complex. I argue that civilians’ decision to mobilize against one or both armed actors is a strategic signal of their allegiance.Footnote3 This choice, however, depends on a careful calculation of the risks and benefits. Civilians will likely mobilize only if it increases their security.

Civilians in conflict zones thus adopt strategies to convey information that maximizes their safety. Civilians in conflict zones, acting as rational actors, strategically align their actions to achieve two main objectives: maximizing benefits and minimizing risks. The way they make these decisions is profoundly influenced by the distribution of power and control within their territory. This involves a careful assessment of which factions hold the upper hand when it comes to military capabilities and control of resources. This is because, in conflict situations where both sides may seek to punish enemy supporters or defectors, it is typically only the more powerful actors who possess the actual capability to enforce such punishments effectively (R. Wood Citation2014). Therefore, it is in the civilians’ interest to demonstrate their allegiance to the stronger party, often by mobilizing against the weaker side. This tactic not only signals their loyalty but also positions them to receive protection or patronage from the dominant force.

However, the question arises as to why civilians wouldn’t simply choose non-participation or neutrality, essentially free-riding in the conflict. While non-participation might seem a safer route, it carries its own set of risks that can make active participation in mobilization a more appealing option (Kalyvas and Kocher Citation2007). Protesting serves as a visible and credible demonstration of allegiance. In conflict zones, visibility is crucial; it is relatively easy to distinguish those who are actively mobilizing from those who are not, especially with the help of local networks and information. In conflict situations, there is a possibility that stronger factions may choose to focus their patronage at an individual level, rather than on entire communities. This strategy would entail giving preference to individuals who have explicitly shown their support. Although the probability of such targeted patronage might not be high in every context, the implications for those who have not visibly aligned themselves with the dominant faction can be serious. Consequently, individuals who choose not to participate may be left vulnerable, as their lack of visible support could be interpreted as disloyalty or opposition.

In smaller communities, the risks associated with non-participation are even more acute. The close-knit nature of these communities often results in greater social cohesion and a heightened capacity for mutual surveillance (Petersen Citation2001). Community leaders, and the community at large, are more likely to notice and take action against those who fail to actively support the community’s interests. This internal sanctioning can manifest as social exclusion or other penalties aimed at perceived free-riders (Kaplan Citation2017). Allowing free-riding behavior, therefore, can lead to detrimental consequences for the community. It could result in insufficient collective action against the weaker side in the conflict, which in turn could jeopardize the community’s chances of securing support or protection from the stronger side. In such a scenario, non-participation not only fails to provide safety but may also act against the broader interests of the community. This complex interplay of risks and benefits often makes active participation, despite its inherent dangers, a strategically sound choice for civilians in conflict zones.

In summary, civilians in civil war contexts must strategically navigate their interactions with armed actors. The decision to protest, and against whom, is influenced by a complex interplay of factors including power dynamics, potential risks, and the need to demonstrate loyalty to ensure safety.

Therefore,

H1:

People are more likely to protest against an armed actor that is not dominant in the area.

So far, I have argued that citizens find it more beneficial to protest against the weak actor. The logical next questions are: do citizens ever protest against a strong actor? Given that a strong combatant has the capability to punish defection or disloyalty, protesting against a strong actor can only be undertaken when the citizen is absolutely sure there will be no retaliation. When does that happen?

Victory in civil wars hinges on the level of civilian support. Non-combatants provide resources and useful information to gain advantage in the struggle (Mao Citation1961). It is common for armed actors to use violence as mechanism to enforce loyalty. Such behavior can even define an agreement in which civilians commit to sharing part of the economic benefits from the territory with armed actors in return for protection and provision of public goods (Arjona Citation2016; Mampilly Citation2011; Metelits Citation2010). However, those agreements do not necessarily guarantee an ideological connection. Although armed actors’ use of violence is common, what really joins citizens and combatants in a web of loyalty is ideological proximity (Jhonson Citation1962; Steele Citation2011). In such contexts, selective incentives are unnecessary. When armed actors and communities share the same ideological identity, they are capable of forming a lasting relationship (Weinstein Citation2007). Committed civilians support the war effort because they find satisfaction in helping their side win the struggle, knowing that their sacrifice is a step forward in achieving future benefits for their community (E. Wood Citation2003). However, the intensity of such a relationship should also be correlated with the strength of the armed actor that is ideologically proximate to the population’s attitudes. Not only do stronger actors signal a greater potential to succeed against their enemy and fulfill future promises, but they also have the means to protect their supporters (Tokdemir et al. Citation2021). When the military organization is powerful, its sympathizers will be committed to defeating the enemy (R. Wood Citation2010). Otherwise, the costs of participation will be high, and few civilians would be expected to take the risk of supporting their ally. In fact, as I argued previously, ideological affinity is not expected to play a large role when the actor in question is weak. In such cases, the high risks of punishment by the stronger armed actor should push most of the sincere supporters towards the enemy camp. So, I argue that ideological affinity only plays a role in target selection when one’s ally happens to be the strong actor. Civilians then can mobilize against the stronger armed actor in the region. But what about the costs of punishment? Do the citizens not expect to be punished by their ally for publicly protesting against it?

I argue that the stronger armed actor should be reluctant to harm its devout supporters – those ideologically connected to the group – despite having the resources and the opportunity to detect and punish those who challenge its control (R. Wood Citation2014). Ideological affinity generates committed recruits who are willing to engage in the high-risk/cost types of participation with which the armed actor seeks to defeat the enemy. These committed civilians show a proclivity to building a long-term relationship with armed actors with the aim of achieving the same political goals (Weinstein Citation2007). Therefore, any type of violence directed toward ideological supporters would tarnish the group’s reputation, destroy grassroots support, and fast alienate its constituency (Angstrom Citation2001). While forcing people to support the group by coercion or through sharing resources and selective goods helps the group continue its activities and its survival in the short run, what really sets the group apart from other armed actors is its long-term support, which is determined by the number of people who are truly loyal to the group because of their beliefs and ideals. In this sense, the powerful actor must differentiate the communities in two: towns that can legitimately address their concerns; and municipalities in which any mobilization against the strong group will be interpreted as treacherous (Tilly Citation2003). The tolerance of the dominant group towards resistance against its control will heavily depend on the political identity that inhabitants embrace. When loyal communities mobilize against the strong actor, the armed actor should find it rational to accommodate the grievances of the population. But, when unreliable communities mobilize against the strong actor, it is in its best interest to reprehend such conduct.

But the argument above heavily hinges on the armed actors’ recognition of citizens’ ideology. The question then is, how evident is the ideological connection of the inhabitants? Some evidence suggests that armed actors observe electoral results in the town where they are located and thus detect the citizens’ ideological positions (Steele Citation2011). Unlike protests, elections provide an anonymous venue in which citizens can pronounce their sincere inclination while keeping their identity hidden. Nevertheless, there is a chance that some risk-averse voters may still behave strategically. That is, they may vote in favor of political parties affiliated with the strong actor despite being sincere supporters of the opposite party. But, such behavior is expected to be low given the risks of residing in the enemy’s loyal constituency where the number of committed informants is likely to be higher. Now, if strategic civilians can effectively mimic with the rest of the population, I argue that the dominant force should still shy away from punishing protestors since it lacks the means to differentiate perfectly between sincere and strategic voters. If the group hurts the community for its contested behavior, it takes the chance that the victims may in fact be genuine sympathizers, in which case, committing violence against them will only alienate the base of the political movement. Thus, while the general tendency of the stronger actor is to punish potential sympathizers of the enemy, including those who protest against its actions in the territory, powerful actors should hesitate to retaliate against protests that originate from the communities that share their political views. In sum, it is rational for armed actors not to punish mobilizations by supporters who they believe are ideologically connected to them.

But, why would ideological supporters of the group need to protest against their own ally? Sometimes, despite the presence of an ideological contract between citizens and combatants, the latter may behave in ways that supporters do not like. In the dynamics of war, combatants sometimes engage in some violent and reprehensible actions – even if not directed at their ideological supporters – that may violate the tenets of the movement that the citizens found so appealing initially. The citizens then remind the combatants the rules of the initial ideological contract, in expectation that the combatant will respond positively. In that situation, if the armed actor is assured of its supporters’ loyalty and ideological proximity, it is not expected to hurt the protestors. That is, the armed actor should see the protest movement not as a signal of defection but as a renegotiation of the contract or a reminder of its terms. Knowing the decision calculus of the strong actor, citizens may choose to protest against their ally knowing that the costs of protesting are low while the benefits are high. Citizens can then urge their ally, who is not likely to hurt them, to respond to their demands.

For example, on 11 April 1988, workers on oil palm plantations ceased their activities for three days in San Alberto, a town in the Department of Cesar, Colombia. The employees were protesting because one of their colleagues had been assassinated by the paramilitaries. The peasants asked the government to improve its protection of civilians (CINEP Citation2002). Even though state forces and paramilitaries held control over the territory, they did not punish the community for its behavior . I argue that the political affiliation of the region is the key to understanding such an outcome. Indeed, the majority of the community supported the Conservative Party. In elections held one month before the protest, the citizens of San Alberto had actually elected most of their local representatives, the Mayor and Municipal Council members, from the Conservative Party and did not support left parties. The neighboring municipalities showed similar political inclinations, also leaning toward the Conservative Party (Registraduria Nacional del Estado Civil Citation1988). Therefore, the plantation workers’ protest was not interpreted as a signal of their loyalty to the rebels as the mobilization was a demand from a population that opposed the insurgents. The state forces and paramilitaries, knowing full well that any violent action against the protestors would only tarnish their support within the territory, chose not to punish the protestors.

Therefore,

H2:

Civilians are more likely to protest against the dominant armed actor in the area if both civilians and the dominant actor share similar ideologies.

Until now, I have discussed cases in which civilians resisted against one specific armed actor. However, civilians may also choose to mobilize against both sides of the civil conflict. In such situations, citizens declare themselves neutral and eliminate the possibility of establishing an alliance with any armed actor. This poses a dangerous situation given that such a decision also eliminates the possibility of receiving protection from any of the parties. If this position can be more hazardous than other alternatives, why and when do they do it?

Violence against civilians is a function of the balance of power between the armed actors within any territory (Kalyvas Citation2006). Armed actors use violence as a mechanism to deter and/or punish defection. However, the effectiveness of such a tool heavily depends on the ability to harm only those who support the enemy (Kalyvas Citation2006). In regions where one side is stronger than the other, the powerful actor can effectively perform such an action because it has the manpower and resources to eliminate mostly the enemy supporters (R. Wood Citation2010). However, armed actors avoid repressing civilians when they operate in contested zones, where neither side holds territorial control. Civilians also refrain from denouncing or informing on enemy supporters because lacking full protection from their ally may make them a target for the victim’s relatives and friends who could counter-denounce them (Kalyvas Citation2006). In the end, armed actors who fail to gather sufficient information from the civilians cannot differentiate foes from allies. Violence in such cases is likely to target the innocent as much as the guilty, leading to defections in a zone where both armed actors seek more control and civilian support. Therefore, armed actors find it rational to refrain from repressing civilians in contested zones in an effort to avoid driving civilians to the enemy side (Kalyvas Citation2006).

In contested zones, civilians should refuse to mobilize against any side of the confrontation given they lack full protection from a strong armed actor. Since control is equally distributed among the military organizations, neither party in the conflict can effectively guarantee its supporters’ safety (Kalyvas Citation2006). Therefore, making any armed actor a target of protests would only reveal toward whom they devote their allegiance. The aggrieved armed actor can then act upon this information, eliminating the guilty party while not pushing the rest of the civilians toward its enemy. What happens if civilians mobilize against both armed actors? In that case, neither combatant can afford to punish this belligerent attitude since such conduct would definitely convince the population to support the other armed party. Under such conditions, it is optimal for both sides to accommodate and fulfill the citizens’ demands (Moreno León Citation2017). Otherwise, their violence may provide incentives for a massive defection, shifting the balance of power in favor of their enemy. Thus, contested zones provide civilians the means to rise up as autonomous actors who can improve their conditions in their community without putting themselves at great risk (Kaplan Citation2017, Vüllers and Krtsch Citation2020). In the end, the absence of territorial control offers civilians the opportunity to increase their bargaining power against all combatants (Uribe de Hincapié Citation2009).

Therefore,

H3:

Civilians are more likely to declare themselves neutral and protest against all sides of the confrontation in contested zones.

Research Design

The long duration of the Colombian civil conflict has driven civilians to consider the war as part of daily life (Pecaut Citation2001). As such, non-combatants have learned to survive while caught in the crossfire (Lubkemann Citation2008). Besides autonomous organizations that encourage dialog between civilians and armed actors (Hancock and Mitchell Citation2007; Hernández Delgado Citation2004), civilians also implement public demonstrations against insurgents, paramilitaries, and state forces to shape the combatants’ preferences towards violence. According to the Social Struggles Dataset from the Center for Research and Popular Education (CINEP), 14% of the total number of demonstrations in Colombia between 1975 and 2010 are protests against one or more armed actors in the war. Protesting against armed actors is commonplace in Colombia despite their risks for civilians.

This study attempts to evaluate how civilians make decisions according to the local dynamics of war. To do so, the unit of analysis I employ in this study is municipality-year. Unfortunately, little cross-national information is available about the local dynamics of civil war and protest behavior. Furthermore, social mobilization data are not typically aggregated by town, and focus solely on anti-government protests. In Colombia, however, private and public organizations have made an effort to collect local-level information about the dynamics of the civil war and protest behavior (Restrepo, Spagat, and Vargas Citation2006). As a result, Colombia presents a good case for testing the conditions under which non-combatants in civil conflicts resist violent organizations.

Such an assessment is more complicated than it may at first seem. Resistance is not the exception. Civilians must make a target selection for their protests in order to maximize their expected utility. However, selecting one alternative does not always exclude the others. For example, civilians from the same territory can mobilize against one group and later hold a protest against both sides of the confrontation. This indicates that the behavior of civilians violates the Independence of Irrelevant Alternatives (IIA) assumption; therefore, analyzing their behavior requires a statistical model that allows for correlation between the choices made by non-combatants (Alvarez and Nagler Citation1998).Footnote4 This challenge drives me to choose the multivariate probit regression as the statistical model. This estimation relaxes the IIA assumption and handles the correlation between the unobservable factors within choices, in this case, the different targets of the protest (Alvarez and Nagler Citation1998). In this case, I estimate three equations with correlated error terms distributed trivariate normal. Moreover, I implement the Geweke-Hajivassiliou-Keane (GHK) smooth recursive conditioning simulator (Cappellari and Jenkins Citation2003).Footnote5

The first two equations evaluate the conditions under which non-combatants protest against one side, insurgents or state forces/paramilitaries, in the war. In both types of protests people ask towards a specific actor to cease its violent actions against civilians. I use both equations to test my first two hypotheses. Meanwhile, the last equation assesses the circumstances that drive civilians to call for a reduction of violent actions from all parties and mobilize as unbiased actors.

My first dependent variable is mobilization against insurgents. This variable equals 1 when there are protests against insurgents in the municipality and 0 otherwise. The second dependent variable is mobilization against state forces and/or paramilitaries. This variable equals 1 when there are protests against the state forces and/or paramilitaries in the municipality and 0 otherwise. The last dependent is neutral mobilization. This variable equals 1 when there are unbiased protestsFootnote6 in the municipality and 0 otherwise. I have taken the information from the Social Struggles Database of CINEP. This dataset uses national and regional newspapers, interviews with social movement leaders, and reports from social organizations to collect information about protests, which CINEP defines as any public demonstration with at least ten participants. I selected all the civilian protests held against guerrillas, paramilitaries, state forces, or any armed actors between 1990 and 2004.Footnote7 Since this is a non-free dataset and my resources are scarce, I used the information of the most intense years of the conflict.

I evaluate my first hypothesis by measuring the capacity of rebel organizations to keep a stable zone of control, defined as areas where insurgents are capable of maintaining the territory despite the enemy’s efforts (McColl Citation1969). The belligerent processes are examined in areas beyond the legal limits of the towns, including neighboring territories (Kalyvas Citation2006). Under these terms, armed actors who hold control over an extensive territory are less likely to be exposed to frequent shifts in power. Then, both armed actors and civilians can set stable expectations about their future strategic interactions. For that reason, I create the variable relative power by dividing the number of casualties of state forces and paramilitaries by the number of casualties among all forces in the conflict within a radius of 25 km (15.53 miles) around the municipality.Footnote8 When the value of this variable is near one, the balance power favors the insurgents. But, when this value is near zero, the balance of power favors the state and paramilitaries.Footnote9 I use the information from the Observatory on Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law.

For my second hypothesis, I use three variables: First, I use relative power, described above. Second, I make the variable presence of left parties by aggregating the number of seats that left parties have in the local council within a radius of 25 km (15.53 miles) around the municipality.Footnote10 I code this information from the electoral statistics of the National Civil Registry. In this case, I address the extent to which the preferences of non-combatants are aligned with the rebels in the area. So, if the presence of left parties is high as in Cumbal, Nariño, then guerrillas (state forces) should perceive the citizens of the town as allies (as enemies). In contrast, when the presence of left parties is low as in Cienaga, Magdalena, rebels (state forces) should identify the citizens as foes (as friends). Finally, I create an interaction variable to evaluate how the variation in the people’s loyalty toward insurgents and the relative regional power influence the probability of protesting against the stronger armed actor.

As mentioned above, I use the last equation to test my last hypothesis. In this case, I again use relative power. In contrast to the previous two equations, I include the square of this variable to assess its potential non-linearity effect on the probability of having a neutral mobilization. I expect that the probability of neutral protest increases when the strength of the insurgents increases but decreases when rebels are extremely powerful.

In all three equations I use the same control variables. All of them explain the conditions under which people are more likely to mobilize (bias and unbiased), but they do not necessarily shed light on the selection process that civilians use at the moment of protesting. First, I account for the number of ethnic autonomies located in the municipality. I use the registers from the Ministry of the Interior, Colombia. Autonomous communities count with the institutional strength to mobilize against armed actors. Second, I use the number of foreign aid projects in each municipality per year. I build this variable based on the reports of the Presidential Agency for International Cooperation, Colombia. NGOs, through the provision of foreign aid, increase the levels of organization within the community and facilitate the mobilization of the population by distributing selective incentives. Third, I create a victimization rate using the number of civilians killed and injured by armed actors, taken from Conflict Analysis Resource Center (CERAC) and the population projection data from the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE) (Restrepo, Spagat, and Vargas Citation2006). Fourth, I employ the square of the victimization rate. I use the last two variables to assess how violence in the territory shapes the probability of protest. Fifth, I account for the number of protests unrelated to war. I use the Social Struggles Database of CINEP. I use this measure to assess the ease with which towns reached the minimum threshold required for mobilization. Sixth, I include the number of Catholic and Christian churches in each municipality in 1995. I use data from Social Foundation. With this variable, I evaluate the role of religious communities in organizing communities for action. Seventh, I employ population density by using population projection data from DANE and geographic area data from the Agustin Codazzi Geographical Institute. Because of the variance of this variable, I log it. I use population density to assess the relative ease with which the population organizes a demonstration. Finally, I use a dummy variable to evaluate the impact of regional capitals on mobilization. This variable equals 1 when the city is the regional capital and 0 otherwise. Political centers are more likely to have the resources and community relationships required for mobilization.Footnote11

Discussion

In the multivariate probit regression, the interpretation of the estimates of one of the equations has to take into account the estimates from the other equations that are part of the model since the disturbances are correlated. However, in this case, despite the fact that ,

, and

are distinguishable from zero, the values of those estimates are negligible and unlikely to considerably alter the prediction made by the model (Greene Citation2003, 716-717). For that reason, I assume the values of

,

, and

are zero when interpreting the estimates of the three equations.

My empirical test supports my first hypothesis. In the first equation of Model 1, for a standard deviation increase in relative power, the odds of having a protest against rebels decrease by 14.5%, holding all other variables constant. In contrast, in the second equation of Model 1, for a standard deviation increase in relative power, the odds of having a protest against state forces and paramilitaries increase by 12.9%, holding other variables at their mean. Therefore, civilians are aware that the costs of mobilizing vary according to the target of the protest. By giving a costly signal, citizens reveal toward whom they devote their loyalty, even if insincerely, with the goal of solving the asymmetric information problem and, avoiding harm by the armed actors. Non-combatants expect to be punished if they protest against the mightier actor. This evaluation does nothing but discourage people from making a public statement against the stronger side. In contrast, when civilians protest against the weaker side, they may expect the powerful actor to protect them from any violent action that the debilitated group could inflict on non-combatants.

Can protest behavior changes if there is a shift in the balance of power? Circumstantial evidence suggests it does. The Uraba’s region was a stronghold of the insurgency by the end of the 1980’s (González, Bolívar, and Vásquez Citation2002). Local elites and the national government implemented a strategy to overcome the security issues that flourished from such situation. On the one hand, local elites supported and sponsored paramilitary organizations with the purpose of deterring guerrilla actions against them (Suárez Citation2007). On the other, the national authorities increased their presence in the territory by establishing more battalions (Carroll Citation2011). Such offensive augmented the human rights violations by paramilitaries and state forces (Suárez Citation2007); civilians protest against state forces and paramilitaries at first (CINEP Citation2002). However, the shift in power began to be noticeable in different areas of the zone (González, Bolívar, and Vásquez Citation2002). In that context, mobilizations against guerrillas became more common, and demonstrations against state forces and paramilitaries were less frequent (CINEP Citation2002).

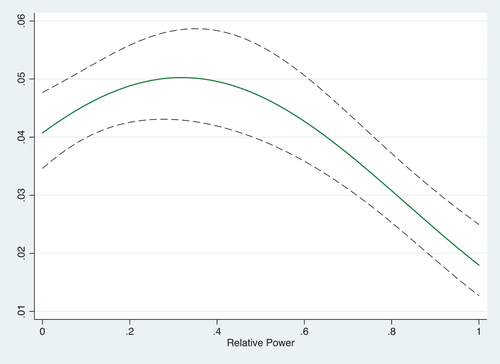

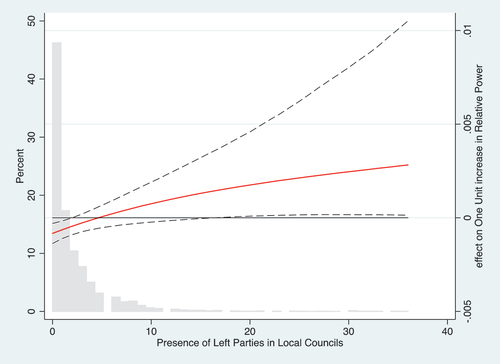

In my second hypothesis, I argue that civilians are more likely to protest against the stronger side as long as they know that the armed actor is assured of their ideological proximity. In the first equation of Model 2, my expectation is that when insurgents are powerful, civilians are more likely to protest against rebels when their electoral preferences favor left parties (See ). My empirical tests support that claim. shows how the effect of the relative power of insurgents on the probability of protesting against insurgents varies according to the number of seats that left parties have in the region. In this case, an increase in the presence of left parties in the zone has a positive effect on the probability of having a protest against insurgents. This effect is positive and significant when the number of seats that left parties occupy in the region is higher than 17.

Figure 1. Effect of unit increase in relative power on the probability of having a protest against insurgents.

Table 1. Civilians protest choice: multivariate probit estimates.

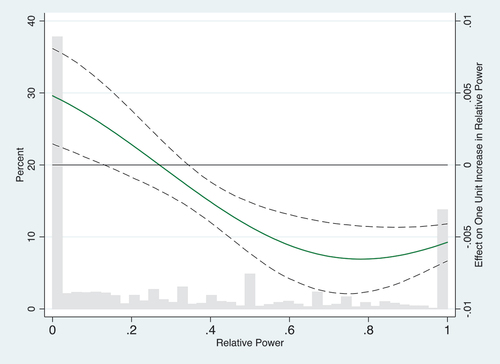

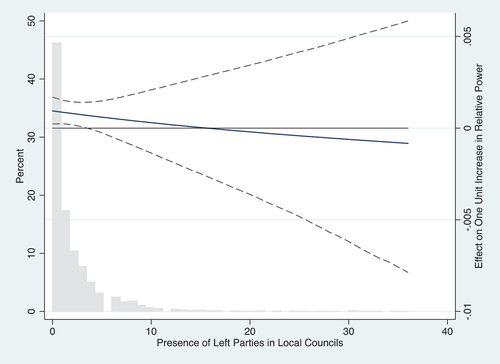

In contrast, in the second equation of Model 2, my expectation is that when state forces and paramilitaries are strong, civilians are prone to mobilizing against the government when their electoral preferences favor non-leftist parties. My empirical test supports that hypothesis. represents the effect of relative power of insurgents on the probability to protest against state forces and paramilitaries as it varies according to the number of seats that left parties have in the region. In this case, the absence of leftist support in the region increases the chances of protest against the government side. Moreover, this effect declines and becomes insignificant when the number of seats that left parties occupy is higher than 3.Footnote12

Figure 2. Effect of unit increase in relative power on the probability of having a protest against state forces and paramilitaries.

Both tests show the importance of citizens’ political alignment. When armed actors are in control of the territory, civilians are more likely to mobilize against the armed actors as long as both share the same political attitudes. Non-combatants expect no punishment by the dominant force who finds it optimal to preserve the web of loyalty from its constituency that helps it maintain control of the territory. Thus, as I predicted, when both the population and the powerful combatant are ideologically linked in a web of loyalty, the armed actor is likely to interpret protest behavior targeting itself not as a signal of alignment with its enemy but as a renegotiation of the contract with its constituency or a reminder of its terms.Footnote13

My final hypothesis argues that civilians are more likely to mobilize as neutral actors when neither of the combatants holds total control of the territory. When the relative power of insurgents increases, the probability of protesting against both sides also rises. However, when the insurgents’ force is too strong, civilians are reluctant to mobilize as neutral actors. illustrates this point precisely, with an inverted U-shaped curve showing that the probability of protesting against both sides increases when the governmental side becomes weaker and that this probability starts to decrease when the relative power is around 0.32. The non-linear effect is significant between 0 and .13 and it is also different zero in the highest part of the curve – around 0.35 (see ). This shows that civilians in contested zones tend to hold neutral protests.

Furthermore, I did a likelihood-ratio test to evaluate if relative power had a non-linear effect on the probability of having a neutral protest. I compared two models: one in which the square term of the relative power was included and another in which it was excluded. The likelihood-ratio test rejected the null hypothesis; the coefficient of the square term of the relative power was different from zero. The test therefore confirmed the nonlinear effect of relative power on the probability of having a neutral protest. Thus, I conclude that while the first part of curve is indistinguishable from zero in the graph, the likelihood test confirms that the probability of having a mobilization against both sides of the confrontation is highest when neither of the armed actors holds total control over the territory.

Robustness Checks

Mobilizing against armed actors is not necessary a discrete decision. In different occasions, civilians prefer to mobilize more than once in a year against armed actors. For that reason, I develop a set of negative binomial regressions to test how the relative power of insurgents and the political preferences of the community shapes the probability of having an additional protest against armed actors. I found that civilians tend to mobilize more frequently against the less dominant actor on the region. I also review how the presence of left parties might influence the probability of having an additional protest against the predominant force in the area. An increase in the presence of left parties in the zone has a positive effect on the probability of having protests against insurgents. In contrast, the absence of leftist support in the region increases the chances of protest against the government side. Political loyalties shapes the probability of having more protests against the strong actor in the area. Additionally, I analyze if the number of neutral protests are more frequent in contested zones. Civilians then are more prone to mobilize against both sides in contested zones.Footnote14

On the other hand, civilians might use other strategies to display their loyalty besides protests. One alternative that civilians might use is voting in favor of political candidates near to the preferences of the dominant actor. Despite the electoral results are concealed and do not help to individually identify who supports whom, the aggregate results might help armed actors to target collectively non-combatants. If both protesting and voting are substitutes, civilians might not participate in demonstrations because they are using other mechanism to reveal their preferences towards armed actors. So, I estimate a series of zero-inflated models to analyze how those voting behavior impinge on the non-mobilization. My first two hypotheses still hold. Furthermore, the evaluations show that there is small evidence that an increase in leftist electoral results increases the probability of having no protests against insurgents. So, civilians might use voting as a signal of loyalty towards combatants.Footnote15

Conclusion

Lately, the literature has moved towards understanding the dynamics of civil conflict as a relationship between armed actors and civilians. Scholars have tried to understand how civilians carry out negotiations with military organizations with the intention of mitigating the effects of the conflict in their communities. However, the behavior of civilians goes beyond those negotiations. In some instances, non-combatants protest and demand better behavior from armed actors. This paper precisely attempts to understand the conditions under which this kind of resistance takes place and, more importantly, against whom civilians show their discontent.

This study argues that the risks that civilians assume by mobilizing vary according to the balance of power between combatants in the territory. Citizens mobilize against the force that has the least chance to punish them. When the level of control favors one side of the confrontation in a region, non-combatants are inclined to protest against the weakest actor. However, when neither actor holds control over the territory, noncombatants are prone to mobilize as neutral. In the first case, civilians preventively act by revealing their allegiance to the strong actor. Ultimately, protest becomes a costly signal that discourages future violent actions by the dominant force. In the latter case, civilians take advantage of the power instability in the region to improve their current situation. Armed actors cannot afford to punish a hostile attitude since such conduct would definitely convince the population to support the other party. As a result, expecting combatants to accommodate and fulfill the population’s demands without retribution, civilians protest neutrally.

Another option is for civilians to mobilize against the stronger actor in the region. In this case, the complaints should come from the people that the armed actor claims to represent. Armed actors rely on a net of loyalty based on their ideological attitudes to nourish their power in the territory. When civilians and armed actors are ideologically proximate, military organizations tend to interpret protest against them not as a signal of alignment with the enemy but as a renegotiation of the contract or a reminder of its terms.

In this paper, I develop my argument under the assumption that civilians are rational actors. According to a cost-benefit analysis, noncombatants choose strategically the target of the protest according to the balance of power among armed actors and their political affiliation. However, self-respect and defiance might drive some civilians to engage in dangerous situations and mobilize against the parties at war. Civilians may simply find pleasure in protest participation because they are making a public statement about the moral standards that the community should have (E. Wood Citation2003). Civilians, in this case, may not be driven by instrumental rationality. Varshney (Citation2003) for example assumes that instrumental rationality is a difficult assumption to make, he claims most civilian behavior is shaped by value rationality where citizens are sensitive to costs but much less so than assumed by instrumental rationality. However, my hypotheses should still hold even under the assumption of value rationality as citizens still care about costs in that setting, even if other factors also play a role in their calculations. That is, the argument is about the elasticity of the cost function, not its existence. If citizens hold some level of cost sensitivity, the strategic setting in this paper is expected to shed light on the behavior of citizens and armed actors.

Future research should delve further into understanding how civilian resistance works. For example, it may be interesting to observe how ethnic lines shape protest behavior against armed actors in ethnic conflicts and compare those findings with mobilization in ‘revolutionary’ wars such as Colombia’s civil war. Moreover, scholars should also analyze how civilian resistance changes over time. During the initial phases of a war, people might be reluctant to mobilize due to uncertainty about the outcome of confrontation, but once war becomes part of their daily lives, as it did in Colombia, civilians may be more inclined to mobilize against the armed groups.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (1.5 MB)Cover Letter Defense and Peace Economics.pdf

Download PDF (97.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2024.2332166.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Earlier version of this paper have been presented in the fourth Dr. Han-Jyun Hou Conference at Binghamton University. The author thanks to Seden Akcinaroglu, Michael Weintraub, David Cingranelli, Ricardo Laremont, and Juan Pablo Milanese.

2. Sometimes civilian resistance can be violent, such as the Rondas Campesinas in Peru and the Naprama Movement in Mozambique, but this is rare (Weinstein Citation2007; Wilson Citation1992), so I will assume in this paper that civilian resistance is non-violent.

3. In some occasions, rallies in favor of one of the parties might be organized, but those actions cannot be considered as costly signals of their loyalty.

4. The IIA assumption states the preferences of an individual over two alternatives in the environment remain the same despite the existence of a third option under the same conditions.

5. Cappellari and Jenkins (Citation2003) recommend using samples of thousands in running the GHK simulation with the square root of the sample. In this case, I use 111 draws for my estimate since my sample is nearly 12,400 observations.

6. These protests are defined as neutral when civilians manifest that they protest against all armed actors involve in civil conflict or when they march against the violence of the civil conflict.

7. According to the codebook, the dataset includes all political struggles from different sectors of the society (e.g. peasants, indigenous people, students, women, conflict victims, workers). All coded protests are collective actions that intentionally make demands to the government, private organizations and, in this case, armed actors in order to correct injustices, inequalities, and exclusions in the society. Therefore, protests that are part of this study do not include rallies in favor of specific political forces since they are organized by the parties in conflict. For further description, please read the appendix.

8. Casualties refers to members of armed groups who were killed. For further description of the construction of this variable, please review the appendix.

9. Some analysts might find troubling using Colombia as a study case for this research since this conflict has multiple rebel groups. According to CERAC’s dataset, there is evidence that in some municipalities is more than one rebel group between 1990 and 2004 . However, such situation only represents .6 percent of the sample. Such outcome confirms Kalyvas’ statement: ‘[n]on-dyadic interactions may be overblown, however, when it comes to the study of the dynamics of violence because non-dyadic conflict may be compatible with locally dyadic conflict’ (Kalyvas Citation2012, fn. 21). Despite Colombia has multiple armed groups, the assumption of a dyadic confrontation still holds to analyze this civil conflict since most of the struggle at the local level is driven by a dyadic tension. I estimate a model without those observations, you can find the estimation and its analysis in the appendix.

10. The left parties included are: Alianza Nacional Popular, Vía Alterna, Movimiento Frente Esperanza, Frente Social y Político, Movimiento Obrero Independiente Revolucionario, Unidad Democrática, Movimiento Ciudadano, Autoridades Indígenas de Colombia, Opción Siete, Partido Comunista de Colombia, Partido Social Democrático, Corriente de Renovación Socialista, Educación, Trabajo y Cambio Social, Polo Democrático Independiente, Alianza Democrática M-19, Partido de los Trabajadores de Colombia, Unión Patriótica, Partido Socialista de los Trabajadores y Frente Democrático.

11. I estimate some models with fewer control variables. Please review the appendix.

12. Despite the predictions of the first two equations support my second hypothesis, I must acknowledge that the standard errors are big and, therefore, the prediction works for a small set of municipalities.

13. Of course, there might be a concern about the impact of the armed actors’ relative power over voting behavior. That is, voting behavior may not be sincere at all, so using it as a measurement of ideological proximity may simply be wrong. The logic could dictate that an increase in the insurgent’s strength may have a positive effect on the number of seats that left parties hold in the local council. That is, citizens’ voting decision may be driven by fear. However, the correlation between the variables relative power and the presence of left parties is −0.01 between 1990 and 2004. Such a result suggests that, at least in the sample used for this study, left parties occupy fewer seats in the local councils when insurgents are the stronger force in the territory.

14. For further details of this analysis, please review the Appendix.

15. For further details of this analysis, please review the Appendix.

References

- Alvarez, M., and J. Nagler. 1998. “When Politics and Models Collide: Estimating Models of Multiparty Elections.” American Journal of Political Science 42 (1): 55–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/2991747.

- Anderson, M., and M. Wallace. 2013. Opting Out of War. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Angstrom, J. 2001. “Towards a Typology of Internal Armed Conflict: Synthesising a Decade of Conceptual Turmoil.” Civil Wars 4 (3): 93–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698240108402480.

- Arjona, A. 2016. Rebelocracy: Social Order in the Colombian Civil War. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Baines, E., and E. Paddon. 2012. “’this Is How We survived’: Civilian Agency and Humanitarian Protection.” Security Dialogue 43 (3): 231–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010612444150.

- Balcells, L., and A. Steele. 2016. “Warfare, Political Identities, and Displacement in Spain and Colombia.” Political Geography 51:15–29.

- Barter, S. 2012. “Unarmed Forces: Civilian Strategy in Violent Conflicts.” Peace & Change 37 (4): 544–571. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0130.2012.00770.x.

- Cappellari, L., and S. Jenkins. 2003. “Multivariate Probit Regression Using Simulated Maximum Likelihood.” The Stata Journal 3 (3): 278–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X0300300305.

- Carroll, L. 2011. Violent Democratization: Social Movements, Elites, and Politics in Colombia’s Rural War Zones, 1984–2008. South Bend: University of Notre Dame Press.

- CINEP. 2002. Base de Datos de Luchas Sociales. Bogota.

- Durán, G. M. 2005. “Repertorio de Acciones Colectivas en la Movilización por la Paz en Colombia (1978-2003).” Controversia 184:149–173.

- EPICA and CHRLA. 1993. “Out of the Shadows: The Communities of Population in Resistance in Guatemala.” Social Justice 20 (3/4): 143–162.

- Fearon, J., and D. Laitin. 2003. “Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil War.” American Political Science Review 97 (1): 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055403000534.

- González, F., I. Bolívar, and T. Vásquez. 2002. Violencia Política en Colombia: de la nación fragmentada a la construcción del Estado. Bogotá: CINEP.

- Greene, W. 2003. Economic Analysis. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

- Hancock, L., and C. Mitchell. 2007. Zones of Peace. Bloomfield: Kumarian Press.

- Hernández Delgado, E. 2004. Resistencia Civil Artesana de Paz: Experiencias indígenas, afrodescendientes and campesinas. Bogotá: Pontificia Universidad Javeriana.

- Jhonson, C. 1962. “Civilian Loyalties and Guerrilla Conflict.” World Politics 14 (4): 646–661. https://doi.org/10.2307/2009313.

- Kalyvas, S. 2006. The Logic of Violence in Civil War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kalyvas, S. 2012. “Micro-Level Studies of Violence in Civil War: Refining and Extending the Control-Collaboration Model.” Terrorism and Political Violence 24 (4): 658–668.

- Kalyvas, S., and M. Kocher. 2007. “How “Free” Is Free Riding in Civil Wars?: Violence, Insurgency, and the Collective Action Problem.” World Politics 59 (2): 177–216. https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.2007.0023.

- Kaplan, O. 2017. Resisting War: How Communities Protect Themselves. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- La marcha de la rabia. February 2, 2008. http://www.semana.com/nacion/articulo/la-marcha-rabia/90798-3.

- Lubkemann, S. 2008. Culture in Chaos: An Anthropology of Social Condition of War. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Mahony, L., and L. Eguren. 1997. Unarmed Bodyguards : International Accompaniment for the Protection of Human Rights. West Hartford: Kumarian Press.

- Mampilly, Z. 2011. Rebel Rulers: Insurgent Governance and Civilian Life During War. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Mao, T.-T. 1961. On Guerrilla Warfare. US Marine Corps.

- McColl, R. 1969. “The insurgent state: territorial bases of revolution.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 59 (4): 613–631. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.1969.tb01803.x.

- Metelits, C. 2010. Inside Insurgency: Violence, Civilians, and Revolutionary Group Behavior. New York: New York University Press.

- Moreno León, C. 2017. “Chronicle of a Survival Foretold: How Protest Behavior Against Armed Actors Influenced Violence in the Colombian Civil War, 1988–2005.” Latin American Politics and Society 59 (4): 3–25.

- Moreno León, C. 2021. “Migrate, Cooperate, or Resist: The Civilians’ Dilemma in the Colombian Civil War, 1998–2010.” Latin American Research Review 56 (2): 318–333.

- Pécaut, D. 2001. “Guerra contra la sociedad.” Espasa.

- Petersen, R. D. 2001. Resistance and Rebellion: Lessons from Eastern Europe. Cambridge University Press.

- Registraduria Nacional del Estado Civil. 1988. Estadisticas Electorales 1988. Bogotá: Registraduria Nacional del Estado Civil.

- Restrepo, J., M. Spagat, and J. F. Vargas. 2006. “Special Data Feature; the Severity of the Colombian Conflict: Cross-Country Datasets versus New Micro-Data.” Journal of Peace Research 43 (1): 99–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343306059924.

- Schubiger, L. 2021. “State Violence and Wartime Civilian Agency: Evidence from Peru.” The Journal of Politics 83 (4): 1383–1398. https://doi.org/10.1086/711720.

- Shah, S. 2008. “Revolution and Reaction in the Himalayas: Cultural Resistance and the Maoist “New regime” in Western Nepal.” American Ethnologist 35 (3): 481–499. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1425.2008.00047.x.

- Steele, A. 2011. “Electing Displacement: Political Cleansing in Apartadó, Colombia.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 55 (3): 423–445. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002711400975.

- Suárez, A. 2007. Identidades Políticas y Exterminio Recíproco: Masacres y Guerra en Urabá. Bogotá: La Carreta.

- Tilly, C. 2003. The Politics of Collective Violence. Cambridge University Press.

- Tokdemir, E., E. Sedashov, S. Hande Ogutcu-Fu, C. Moreno León, J. Berkowitz, and S. Akcinaroglu. 2021. “Rebel Rivalry and the Strategic Nature of Rebel Group Ideology and Demands.” The Journal of Conflict Resolution 65 (4): 729–758.

- Uribe de Hincapié, M. 2009. “Notas Preliminares sobre Resistencias de la Sociedad Civil en un Contexto de Guerras y Transacciones.” Estudios Políticos (Medellín) 29 (29): 63–78. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.espo.1296.

- Valenzuela, P. 2009. Neutrality in Internal Armed Conflicts: Experiences at the Grassroots Level in Colombia. Uppsala: Uppsala University.

- Varshney, A. 2003. “Nationalism, Ethnic Conflict, and Rationality.” Perspectives on Politics 1 (1): 85–99.

- Vüllers, J., and R. Krtsch. 2020. “Raise Your Voices! Civilian Protest in Civil Wars.” Political Geography 80:102183.

- Weinstein, J. 2007. Inside Rebellion: The Politics of Insurgent Violence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wilson, K. B. 1992. “Cults of Violence and Counter-Violence in Mozambique.” Journal of Southern African Studies 18 (3): 527–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057079208708326.

- Wood, E. 2003. Insurgent Collective Action and Civil War in El Salvador. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wood, R. 2010. “Rebel Capability and Strategic Violence Against Civilians.” Journal of Peace Research 47 (5): 601–614. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343310376473.

- Wood, R. 2014. “Opportunities to Kill or Incentives for Restraint? Rebel Capabilities, the Origins of Support, and Civilian Victimization in Civil War.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 31 (5): 461–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/0738894213510122.