ABSTRACT

Path dependence has become a multi-disciplinary concept, employed across various literatures to explain why the past matters for decision-making. Debate within ‘new institutionalist’ scholarship has provided a detailed critique of the term over several decades. Some scholars argue that it is hampered by poor conceptual clarity and highlight its limitations in explaining institutional reform. Yet, this paper demonstrates how neglecting antecedent conditions and associated decision pathways is particularly inappropriate for politico-spatial issues like disaster risk and natural resource governance. Doing so risks omitting key material and perceptual contingencies influencing contemporary institutions. Examining southeast Queensland’s flooding disaster of 2011, the paper proposes that path contingency provides a useful theoretical bridge between institutionalist theories of stability and reform, and the geographic contexts within which disaster risk governance proceeds. The analysis then addresses the potential generalisability of path contingency beyond its application to disaster management, for consideration across a broader range of institutionalist research.

Introduction

Path dependence is a concept used across a range of governance-focused scholarship, including new institutionalism, human geography and urban studies (e.g. Choi et al. Citation2019; Coe Citation2011; Sorensen Citation2018). The term has frequently been used without mechanistic explanation or elucidation of its standing in relation to theories of structure and agency in government decision-making (see overview below). Historical institutionalists, by contrast, have explored decision pathways in detail, along with the propensity (or otherwise) for path dependencies to influence governance outcomes. What is often missing from institutionalist research, however, is discussion of the influence that material contingencies (e.g. in relation to infrastructure management) can have on institutional structure and reform.Footnote1 This paper proposes that path contingency provides one appropriate conceptual bridge between institutionalist perspectives seeking to understand the influence of structure on agency, and the material and geographic variables that can and do influence the governance challenges arising from disaster events.

To this end, this paper re-examines the 2011 flooding disaster in Queensland, Australia. This case has been explored in detail by a range of political science, human geography and historical scholarship (Cook Citation2016; Heazle et al. Citation2013; Tangney Citation2020; Citation2017, 203–212; Citation2015). Perhaps most notable was an important analysis by Stark (Citation2018) in this journal. Using an institutionalist lense, Stark examined Queensland state government’s response to the disaster in terms of infrastructure management, regulation, natural resource strategy, and party political rhetoric in the aftermath of the floods. His analysis emphasises the importance of the critical juncture as a mechanism for understanding institutional reform for disaster risk governance. In doing so, however, Stark largely neglects the role of preceding decision pathways or antecedent conditions and the propensity for institutional reform given the geographic contexts in which those changes occurred.

In this paper, I seek to specifically examine the geographic contingencies at play in the Queensland case to elaborate on processes of policy stasis and reform, before and after the events in question. Stark (Citation2018, 26) sought to provide a more nuanced approach to what he perceived to be dichotomous accounts of either punctuated equilibrium or gradual incrementalism common in institutionalist research. He proposes that ‘post-crisis reform periods can be moments in which sudden change, gradual change and no change can all occur concurrently’. This author shares Stark’s concerns about unhelpful ‘either/or’ dichotomies that may be drawn between contrasting accounts of institutional reform. By neglecting the influence of decision pathways in particular, as I demonstrate here, we can but paint an incomplete picture of the institutional factors that may influence varying outcomes in the aftermath of disaster events. This paper therefore specifically examines the influence of physical infrastructure constraints and related antecedent conditions in processes of institutional reform for Queensland’s disaster risk governance.

This paper demonstrates that, while deterministic notions of path dependence unduly simplify our understanding of stability and change, materially-contingent institutional structures can nonetheless play a significant role in constraining the quantum, locus and timing of governments’ post crisis policy reforms. Path contingency (Johnson Citation2003, 292), I argue, is an important explanatory mechanism for understanding the evolution of institutional disaster risk governance. As I show here, the contrasting outcomes for policy reform in Queensland are most meaningfully explained by incorporating path contingent variables in play before, during and after the flooding events in question. I conclude that the examination of path contingencies should play a more meaningful role in explaining institutional stasis and reform relating to the governance of natural resources and the management of environmental risk.

To begin, the paper examines evolving perspectives on the concept of path dependence and how we might consider a less deterministic alternative (path contingency) for understanding institutional function and policy development. Next, I provide an overview of the Queensland case and demonstrate how path contingencies were influential in disaster management outcomes and policy reform in response to the floods. In the discussion, I address some key criticisms of historical institutionalism and path dependence that might also be wielded against path contingency, or used to otherwise justify omission of antecedent conditions and decision pathways from considerations of institutional reform. While institutional analyses of natural resource and disaster management governance are likely necessarily incomplete without understanding the influence of material interventions in space, I propose that path contingency may have broader applicability across a range of historical and other institutional analyses.

Path dependence

Peters (Citation2019, 63) defines path dependent variables as ‘choices made when an institution is being formed, or when a policy is being initiated, [that] will have a continuing and largely determining influence […] far into the future’. Kay (Citation2005, 553), similarly, proposes that ‘A process is path dependent if initial moves in one direction elicit further moves in that same direction’. A range of scholarship appears to find the concept intuitively appealing to help explain institutional stability and why policy outcomes can arise in apparently path-limited ways. This intuition, and the extent to which it holds validity, has been a topic of prolonged debate amongst institutionalist theorists for over 40 years (Krasner Citation1984; Pierson Citation2000, 489; Koning Citation2016). Despite multiple potential modes by which decision pathways may be formed and induce institutional stability or divergence, however, there remains confusion about what the path dependence concept is, theoretically speaking, and how it should be used (Rixen and Viola Citation2015, 303–305).

Kay (Citation2005, 554) argues that path dependence constitutes neither a policy framework nor a policy theory, but rather an organising concept or empirical category to help retrospective understanding of temporal policy processes. Path dependence alone neither explains underlying assumptions and their inter-relationships much as a policy ‘framework’ can, nor provides testable hypotheses as a policy theory should (see Jenkins-Smith et al. Citation2018, 138). Howlett (Citation2009, 244) and Levin et al. (Citation2010, 10–12), on the other hand, allow path dependence greater theoretical weight, implying that the concept can be considered a type of policy ‘mechanism’ to help explain observed processes and to bolster substantive theories within a given framework.

Both historical institutionalism and punctuated equilibrium theory often envisage path-dependent mechanisms influencing policy reform as a result of institutions’ inherent conservatism and their propensity for gradual change. Beyond this perspective, however, path dependence continues to be deployed uncritically across several disciplines to imply that the past matters (e.g. Jungblut and Jungblut Citation2022, 823; Korinek and Veit Citation2015, 104). Alternatively, the term is used in more precise ways, albeit without elaborating the exact mechanisms by which it occurs (e.g. Davidescu, Hiteva, and Maltby Citation2018, 613; Hay Citation2011, 178). Djelic and Quack (Citation2007, 164–166) thereby distinguish between a ‘weak historicist’ conceptualisation that does not specify clear mechanisms by which institutional stability or policy legacies become established, entrenched or reproduced, versus a strong historicist form originating from economic theory and political science that highlights both processes of initiation and stabilisation of policy pathways.

Although path-dependent processes were originally conceptualised in terms of increasing economic returns, the political sciences have since identified ‘non-utilitarian’ path dependencies associated with political interaction, or arising from feedback mechanisms of the policy process. Page (Citation2006) and Sarigil (Citation2015) discuss utilitarian and non-utilitarian (or normative) path-dependent mechanisms evident in the accumulated literature that can be ascribed to theories of policy development and change as well as to theories of rational decision-making. Likewise, Gains, John, and Stoker (Citation2005, 27–30) and Levin et al. (Citation2010, 12–14) discuss a variety of institutional factors at play that could produce path contingent, or indeed, path divergent outcomes, but are more or less likely depending on circumstance. The short time horizons of political decision-making, for instance, may dissuade deviation from a policy pathway if gains from such a change will likely be accrued over the long term while the political costs are felt within electoral cycles. Institutions’ conservativism may make them resistant to all but incremental changes to avoid disrupting existing hierarchies, ideological assumptions or established networks (Baumgartner, Jones, and Mortensen Citation2018, 57; Gains, John, and Stoker Citation2005, 28). Alternatively, it may be expedient for policymakers to push for radically path-divergent trajectories if they can secure short-term political capital (e.g. as a result of proposing audacious or imaginative reforms), the costs of which will only be accrued over the long term (Gains, John, and Stoker Citation2005, 29). Given the variety of contrasting dynamics and variables in play, Johnson (Citation2003, 291–294) suggests that path dependence is often wielded in overly-deterministic ways. She argues for path contingency as a more appropriate descriptor for the influence of historical arrangements on policy development, particularly in extraordinary political circumstances arising at a critical juncture.

Path contingency

This paper also seeks an intermediate conceptualisation for the influence of decision pathways, that eschews over-simplistic assumptions concerning the trajectories of institutional decision-making as a result of random events, from process sequence, from incrementally increasing returns, or for that matter, the rejection of decision pathways entirely. The challenge for understanding policy reform for disaster risk management, I argue, is to explain the likely interactions between possible institutional decision pathways, socio-economic contingencies and the biophysical environments in which they operate. Studies integrating the concept of path dependence with considerations for the design, arrangement, construction, management, operation or public/governments’ perceptions of physical objects in space, are somewhat rare in the literature (see, e.g. Berkhout Citation2002; Meecham Citation2009; Smith, Stirling, and Berkhout Citation2005; Sorensen Citation2015). I seek to demonstrate how these material contingencies can arise and interact with governance institutions in ways that necessarily have an instrumental effect on institutional functioning, stability and susceptibility to change.

For this purpose, I expand on Johnson’s (Citation2003, 292) proposal that path contingency better explains the interplay between structure and agency when seeking to understand institutional outcomes arising from critical junctures. Johnson explored path contingencies as a means to understand the aftermath of the partial or total collapse of legacy institutions in communist jurisdictions at the end of the Soviet Union. She used the concept to account for the contrasting outcomes of policy design choices made when establishing refurbished or replacement institutions. In this context, Johnson conceives of legacy institutional arrangements and capacities as ‘intervening variables’ (292) to be accounted alongside the independent variable of policy design choice. For Johnson, in the context of institutional collapse, it is clear that agency holds primacy over institutional legacy, but she nonetheless sought to account for antecedent conditions when understanding policy outcomes without the heavy-handed determinism implied by path dependency. Here, I seek to reinvigorate the concept of path contingency to allow for its applicability beyond the extraordinary political circumstances that she examined. Nonetheless, I seek a similar explanatory goal: to account for antecedent conditions in a way that balances consideration of decision pathways alongside the agency of institutional actors without giving either variable undue deterministic weight. I thereby define path contingency as the mechanism by which institutional legacies and antecedent conditions affect the relative likelihoods of alternative potential governance reforms.

For the purposes of examining the Queensland case-study, I use a mechanistic and analytic framework previously developed for path dependence by Page (Citation2006, 99–109), amended by Levin et al. (Citation2010, 11–14) and tailored further for my discussion of path contingencies here. I use four categories of path contingency, including:

Lock-in: a policy intervention holds immediate durability upon initiation, due to some significant benefit accrued by those affected by it, or some disbenefit inevitable from its subsequent removal.

Increasing Returns: the benefits of a policy intervention increase over time.

Self-reinforcement: an initial intervention necessitates complementary activities that encourage the perpetuation of that intervention, either through reinforcing the value of the original intervention, or increasing the costs of reversal.

Positive feedbacks: a policy intervention gains momentum as a result of increasing benefits to supporters of the intervention when additional supporters are accrued.

Here, these categories are used to explain the role and influence of infrastructure provision in the disaster management practices of regional and local governments of southeast Queensland. The Queensland case-study revolves around the physical design and policy and administrative processes established for the management of Wivenhoe Dam. This public asset has become central to any robust understanding of the flooding events of 2010–2011, if not also Queensland’s disaster risk and natural resource governance over the past 50 years or so. My analysis suggests that an understanding of the path contingencies arising from the existence, operation of, and expectations for, public infrastructure provides some predictive ability as to the types of policy reform that are likely in the aftermath of a critical juncture arising from a crisis event.

My analysis is focused on a single case-study given the need for a ‘micro-foundational’ explanation (Thelen Citation1999, 377) of variables to elucidate path contingent mechanisms. Such elaboration is necessary given the intricate nature of the contingencies influencing the relative likelihoods of possible reform outcomes arising from antecedent conditions. Comparative case-study analysis, although potentially useful, would demand much more space than I have available here.

The Queensland floods 2011 – how critical infrastructure shapes a critical juncture

The flooding events in southeast Queensland during the winter of 2010–2011 have been documented by various academic studies (e.g. Cook Citation2016; Heazle et al. Citation2013; Stark Citation2018; Tangney Citation2015; Citation2020), as well as independent public inquiries and judicial proceedings (QFCI Citation2011; Citation2012; Supreme Court of New South Wales Citation2019). Most notably, an independent Commission of Inquiry – established in the immediate aftermath of the events – produced lengthy and detailed analysis (QFCI Citation2011; Citation2012). Given the number of published studies that have recounted these events, this paper will not attempt a full synopsis and instead focuses on those aspects relevant to this paper’s arguments concerning the path contingencies arising from infrastructure development and operation, and their influence on Queensland’s governance institutions.

The southeast Queensland region has a long history of flooding, owing to its subtropical Pacific coastal location and exposure to non-annual weather variability arising from the El Nino Southern Oscillation. So-called La Nina weather events under this climate regime tend to make annual wet seasons in southeast Queensland particularly prone to extreme prolonged rainfall. The winter of 2010–2011 marked just such a La Nina period for Brisbane and its surroundings so that, by 11 January 2011, after months of prolonged rainfall the Brisbane River broke its banks causing severe inundation of properties at several locations, including at the city’s central business district. Flooding peaked on 13 January 2011 and by the time the waters subsided, 35 people had been killed and approximately $35 billion in damages accrued. The events leading up to the flood peak were subject to extensive investigation by the Commission of Inquiry, most particularly in relation to the operation of the Wivenhoe and Somerset dams through which approximately 50% of the flood waters had passed (QFCI Citation2011, 39). The operation of the Wivenhoe Dam had been particularly scrutinised by the Commission given its proximity to Brisbane City and accompanying perceptions that its operation was especially instrumental for the extent of flooding experienced in the city.

The Wivenhoe Dam was commissioned in 1976, in the aftermath of the last major flooding event in the region. The floods of 1974 exceeded the 2011 floods in terms of peak flood height, even though the particular dynamics of the 2011 floods were likely more hazardous. The exact rationale for building the Wivenhoe Dam is somewhat opaque from the available literature. It appears to have been motivated in part by a reaction to the 1974 floods, and before that, the 1893 floods which had first prompted considerations of a dam network for the river (Tangney Citation2020, 362). However, Wivenhoe’s construction was also motivated by the impacts of prolonged drought in the region, and the expected water resource needs of the growing downstream urban population (QFCI Citation2011, 38–39; Cook Citation2016, 541).

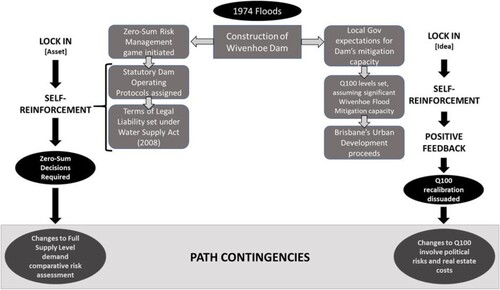

Either way, the dam was completed in 1985 and we can identify, with its completion, the initiation of significant path contingent mechanisms that would – for the lifetime of this public asset at least – constrain disaster management options for both state and local governments (see ). This path contingency arose upon completion of the dam because this asset ‘locked-in’ an unavoidable zero-sum game arising between the competing priorities for flood mitigation and water resource management. If the water reservoir behind the dam is at full capacity, flood mitigation is necessarily maximally constrained. Conversely, the reservoir’s water supply capacity is inevitably constrained by the dam’s flood mitigation role. The dam’s dual operation, therefore, balances conflicting objectives demanding an inevitable zero-sum trade-off in times of concurrent contrasting climatic extremes.

To maximise the flood mitigation potential of the Wivenhoe Dam to address the volume of water presented by the La Nina rains of 2010/2011, sufficient storage capacity could only have been made available in the reservoir by pre-emptively releasing water. Such releases, however, necessarily constrain the capacity of the Wivenhoe Reservoir to meet the water resource needs of surrounding communities. The means of balancing these competing priorities in practice has been to assign virtual ‘compartments’ in the reservoir’s storage capacity; one of which (1,165,000 megalitres) is left full to ensure a minimum volume of water supply (the so-called ‘Full Supply Level’ (FSL)), the other (1,420,000 megalitres) is left empty to ensure a minimum level of flood mitigation capacity (QFCI Citation2011, 39). At times of extreme climate stress, as experienced during the so-called Millennium Drought (2001–2009), and during the Queensland Floods 2010–2011, however, neither of these compartments are sufficient for the purposes of mitigating drought, or flooding, respectively.

The official accounts of the 2011 floods demonstrated that the responsible parties for the operation of the dam were placed under some pressure to release waters in advance of the expected floods, but they declined to do so (QFCI Citation2011, 45–46). The reasons for this demurral can be inferred from the deliberations between the dam operator, the relevant state government department and the responsible state government minister, which the Commission’s investigation records in some detail from sworn testimony. The decision not to pre-emptively release water from behind the dam appears to have been principally motivated by fear of the political implications of doing so in the context of the nine-year drought which had preceded the rains of 2010–2011, and which emphasised the potential for public outcry resulting from any reduction of water supplies for surrounding communities (Stark Citation2018, 30–32). Moreover, those with political responsibility for a reservoir drawdown (the state Department of Environment and Resource Management and the appointed state government minister) sought to pass the decision-making responsibility to technical experts, despite the clear normative implications associated with the decision (QFCI Citation2011, 46–49). Ultimately, despite the existence of ascribed compartments to balance the competing needs for flooding and drought mitigation, the dam’s zero-sum game must play out when dam operators are faced with abnormally extreme weather events.

The path contingent impact of this zero-sum game becomes more fully apparent when we then examine other considerations of local and state governance that are impacted by the imposition of the aforementioned limits to the dam’s risk mitigation capacity. The initial path-contingency arising from asset lock-in was (perhaps inevitably) compounded by self-reinforcing mechanisms arising from government’s perceived need for precise engineering protocols that would ensure the dam was operated safely and in a way that could effectively balance the competing needs for flood and drought mitigation. In order to codify the dam’s operation, the state government oversaw the development of an operational manual to direct dam engineers. Additionally, the manual was subsequently accommodated in state legislation under the Water Supply Act 2008. Although the manual is not mandated under the legislation, section 374(2) of the Act stipulates that a dam operator who follows the operational procedures set out in a manual approved by government, will not incur civil liability in the event of any adverse consequences arising from the dam’s operation (QFCI Citation2011, 37). Thereby, we can observe a process of self-reinforcement in addition to the initial lock-in arising from the construction of the Wivenhoe Dam. Successive governments have sought to ensure appropriate operational procedures, and to limit their legal liability associated with those operations. The legislative strictures provided by the manual and the terms of the Water Supply Act meant that the terms of legal liability relating to dam operations were set. The dam operators cannot be prosecuted as long as they adhere to the manual, irrespective of whether the particular circumstances might justify deviation from that protocol in reaction to, or anticipation of, extreme climatic conditions.

The compounding mechanisms of path contingency that were initiated by the construction of the dam, however, did not end with state government’s provisions for the safe operation of this asset. The Commission’s investigation also reveals how the original commissioning of the dam in 1976 and the codification of its operation within state legislation had a knock-on impact on the local governance of flood risk management. Brisbane City Council’s urban planning process had been informed since the 1970s by a flood mapping tool developed from calculations of the Annual Exceedance Probabilities of extreme flooding events. The so-called Q100 calculation, derived from hydraulic and hydrologic modelling of the Brisbane River floodplain, provides an indication of potential flood heights with a 1% probability of occurrence in any given year, at various locations across the city. Q100 zones, thereby, denote areas of particularly high flood risk across the city. The values calculated for this risk management metric are determined by a model that incorporates historic extreme rainfall events and the hydraulic/hydrologic characteristics pertaining to those locations (QFCI Citation2012, 43). On the basis of modelled Q100 flood heights, Brisbane City Council has drawn up successive city plans outlining the types and extent of property development allowable in different locations around the city since 1976. The underlying modelling and its determination of Q100 levels, however, was ultimately shaped by Brisbane City Council’s starting assumptions about how the Wivenhoe Dam would be operated in practice.

As revealed by the Commission of Inquiry (QFCI Citation2012, 48–51) and elaborated in further document analysis by Tangney (Citation2015), the Council commissioned a total of six assessments to derive Q100 calculations in the period between the commissioning of the Wivenhoe Dam in 1976 and the 2011 floods. None of these successive assessments made fully precautionary assumptions about the dam’s operation. That is, none of the Q100 calculations incorporated an assumption that the Dam would be at, or above, FSL and therefore maximally limited (within the rules of the operational manual) in its ability to attenuate flooding beyond the capacity of its default flooding compartment (Tangney Citation2015, 499–502). The assumptions used to underpin the Council’s Q100 calculations appear to have been that dam water-levels in practice would be significantly below this FSL. Irrespective of this faulty assumption (Wivenhoe Dam was in fact at FSL in advance of the 2011 floods), we can see how the approval for construction of the dam in 1976 established a path contingent influence on local government policymaking with regard to urban spatial planning and property development at various locations around the city. Q100 limits were set on both the extent of property development in flood-prone locations, as well as on the design of properties within Q100 flooding zones. These limits have ultimately determined the level of vulnerability of urban properties to flooding. Because those limits had not taken a precautionary approach to their working assumptions about dam operations, however, the Q100 zones set out in successive city plans have ultimately left properties more exposed and vulnerable to flooding than they might otherwise have been, or than property owners believed (Tangney Citation2015, 502).

Moreover, the path contingency arising from the establishment of Q100 that was instigated by the dam proposal, has compounded over time. As property development in the Q100 zone has proceeded, the incentives for an upward revision of Q100 levels in line with more accurate FSL assumptions have correspondingly diminished. Any upward adjustment of Q100 levels and corresponding stringency of urban development regulations would have had a significant impact on properties and property development within an increasingly dense urban space (Tangney Citation2015, 502). Increasing the size of the Q100 zone, and/or enhancing the design requirements for properties within this zone would likely have adversely impacted property values. Properties within the zone might require retrofitting of flood defence measures to account for higher flood risk. Similarly, properties once on the periphery of the city’s Q100 zones might be re-situated within a higher flood risk zone as a result of any recalibration of assumptions about dam operation. Both possibilities could decrease the market value of those properties and/or otherwise incur significant expense to property owners. Therefore, any such change in urban planning flood zones would likely present significant political risks for the elected members of Brisbane City Council.

What propensity for institutional change?

The path contingent mechanisms described above provide a useful example for understanding the challenges facing institutions that rely on public infrastructure assets for disaster risk management. The susceptibility of institutional arrangements to post-crisis reform in the Queensland case, I propose, depended in significant measure on the ongoing constraints imposed by physical infrastructure, its associated operating protocols and the derivative risk management perspectives of state and local government, and the public. This is not to suggest that either policy stasis or change was determined entirely by those contingencies. Nonetheless, the identification of significant path contingent mechanisms may provide some ability to assess the relative likelihood of success – all else being equal – of a range of potential reforms arising from a critical juncture. For this, I join Stark (Citation2018, 27) in deploying Soifer’s (Citation2012, 1573) characterisation of necessary but insufficient permissive conditions that determine the scope and duration of a critical juncture, along with necessary productive conditions that determine what reforms are effected.

Tangney (Citation2020, 363–365) and Stark (Citation2018) describe several concurrent institutional responses associated with critical junctures arising in the aftermath of the Queensland floods. As Stark (Citation2018, 30–34) describes, those reforms that were low cost in economic, political or bureaucratic terms in the aftermath of the flood proceeded quite quickly. For instance, state government were asked, and declined, to reduce the dam reservoir volumes below the FSL in advance of the anticipated floods (QFCI Citation2011, 46). In the immediate aftermath of the peak flood event of 13 January 2011, however, they ordered a 25% reduction of dam water levels. This policy U-turn exemplified a punctuated change of a sort that demonstrates the potential for crisis events to effect the permissive conditions that can lead to critical junctures, resulting in the possibility of significant policy reform.

A U-turn from state government in relation to dam water levels would have presented a politically risky move in advance of the floods, given prevailing perceptions about the value of dam waters that had been established during Queensland’s extended drought over the preceding decade. However, the floods provided the permissive conditions for a critical juncture during which government could justifiably reverse their pre-crisis position. In this instance we can identify media scrutiny, criticism of the opposition political party’s pre-crisis rhetoric, and heightened public flood risk perceptions as the productive conditions allowing for this policy u-turn (Stark Citation2018, 31,34,35). Fundamentally, government sought to appease public concerns about any further flooding that might have followed the peak on the 13th January. However, this policy change was also undertaken within the limitations of existing structural constraints that hindered more substantial policy reforms. For instance, no attempt was made, immediately post-crisis, to recalibrate the dam’s assigned FSL.

However, government did take steps to amend the dam’s operating manual in line with the Commission of Inquiry’s recommendations. This reform related to the extent and timing of water releases allowable during crisis flooding events, not to the aforementioned prioritisation between flood risk versus water supply as codified by the FSL. As with the post-crisis reduction of dam water levels, the reform of dam protocols constituted a low-hanging fruit in terms of its political and technical feasibility. The productive conditions needed for these reforms (i.e. media scrutiny, public risk management concerns, the Commission of Inquiry’s reports) presented themselves during the critical juncture in the immediate aftermath of the floods. These reforms carried few if any direct implications in terms of diverging from the decision pathways established from the construction of Wivenhoe Dam, or the subsequent constraining decisions about the comparative trade-offs between flood risk and water security. They related principally to the drawdown of water levels in the midst of a flooding event. The Commission of Inquiry identified limitations in the manual’s operating procedures that could be easily remedied, without drawing political fire concerning policies that had codified the comparative risks and benefits of holding more or less water behind the dam.

Conversely, we can also identify areas of reform that were not subject to punctuated change despite the opening of a critical juncture. We can surmise that these were hindered by an absence of the productive conditions necessary to overcome the path contingencies at play. Reforms to legislation, regulation and FSL calibration, appear to have been particularly constrained by the path contingencies arising from the existence and operation of the dam, since they related to the codification of governments’ normative priorities, and the political and economic implications associated with any deviation from those priorities. In particular, state government’s priorities for water security versus flood risk, and local government’s relative prioritisation between sustaining urban development and managing flood risk. Any adjustment of the dam manual’s codified risk prioritisation, of the terms of the Water Supply Act (2008), of Queensland’s water strategy and related policies, or Brisbane’s Q100 calculation would have required significant deviation from the path contingencies established as a result of the Wivenhoe Dam.

Punctuated reforms to these governance instruments would have required consideration of a set of risk prioritisations that were highly complex and contentious with the potential for political controversy over both present and historic decision-making in relation to dam management. Such considerations would be limited by both the bounded rationality of institutional actors over short timescales, and the political repercussions of any proposed changes at a time of heightened public awareness of disaster risks. Governments’ adjustment of path contingent regulatory instruments or operating protocols during a crisis-induced critical juncture, I propose, was therefore considerably less likely given the technical, political and strategic challenges of prioritising between flood and water security risk management at a time of heightened sensitivity to disaster events.

The productive conditions needed for a significant strategic change to legislation and regulatory instruments might have included political deliberation over the relative risks of flooding and drought and the implications of any preferences in this regard for how public infrastructure assets were managed. Yet, such productive conditions were unlikely to manifest sufficiently within a relatively brief post-crisis critical juncture given what such a deliberative exercise might reveal. As Stark’s (Citation2018, 32–35) analysis shows, this deliberation did begin to occur in the aftermath of the floods, along with a slow process of institutional reform in relation to risk prioritisation, but this proceeded on timescales more aligned with gradual incrementalism, rather than a policy punctuation.

The implications of existing risk prioritisation and associated path contingencies are likely to have also impeded punctuated reforms by local government. The path contingencies in play for Brisbane City Council related to their Q100 metric and its assumptions about dam management. As discussed above, any reform of Q100 would likely have raised significant political intrigue concerning the assumptions made in preceding Q100 calculations. Indeed, the Q100 calculation has been a controversial issue at several points in the past, garnering significant media attention and highlighting the bounded rationality of local governments because of the technical challenges of developing this flood risk metric (Tangney Citation2015, 500). So, the productive conditions that allowed government to reduce dam levels and to marginally adjust the dam manual during the critical juncture arising from the 2011 floods had previously been insufficient to effect institutional change by local government in relation to Q100 recalibration. Even in the aftermath of the 2011 floods, with potentially permissive conditions available, those path contingencies meant that the productive conditions for Q100 reform were likely much more substantial than merely heightened public risk perception and accompanying media scrutiny.

Adjustments to Brisbane’s Q100 maps would create significant material constraints with political implications: a likely expansion of the Q100 flood zone in the city to account for state government’s operational commitment to maintaining FSL, likely downward adjustments by the market to property prices, and costs incurred for property owners from the need for retrofitting to account for properties’ recalibrated flood risk exposure (Tangney Citation2015, 500). These adjustments would likely present significant corresponding political risks for Brisbane’s elected city council. Under such conditions, it was unlikely that Q100 recalibration would occur. However, that is not to say that no action was taken by Brisbane City Council in the aftermath of the floods. Since the events of 2011 and the scrutiny provided by the Commission of Inquiry, the explicit use of Q100 has been abandoned entirely by Brisbane City Council. No mention of it has appeared in their subsequent city plans, much less any discussion of the assumptions concerning dam operations that underpin their current flood risk calculations (Tangney Citation2020, 365). We thereby see the potent limitations imposed by the path contingencies arising from the Wivenhoe Dam.

None of the institutional arrangements that underwent punctuated reforms in the aftermath of the floods were substantially constrained by the path contingencies arising from the Wivenhoe Dam. Conversely, each of those reforms that proceeded incrementally (i.e. water strategy and related policy reforms and political deliberation over risk prioritisations, dam management and FSL recalibration), as well as significant non-changes (e.g. Q100 recalibration) were either directly or indirectly impeded by those path contingencies. Appropriate understanding of such contingencies and the pathways they established, I argue, can assist in anticipating the likely focus of punctuated reforms, while identifying those areas of reform less likely to occur as punctuations given that they would require exceptionally strong productive conditions within the window of a given critical juncture. This case-study thereby demonstrates how understanding of path contingencies allows for analysis of which plausible reforms are more or less likely.

Discussion

The preceding analysis indicates that for governance contexts involving institutions’ material interventions in space, antecedent conditions and associated decision pathways can be important explanatory variables for understanding processes of stability and reform. For institutional governance of natural resource and disaster risk management in particular, I argue, these variables should receive greater accommodation in institutional analyses. However, to make use of the mechanistic insight provided by path contingencies across the broadest range of institutionalist research, here I wish to address some extant criticisms of historical institutionalism (HI) and path dependence to which this less deterministic alternative may also be susceptible. I then discuss the general utility of this concept for institutionalism and the potential for its use in future research.

The explanatory worth of exogenous shocks and critical junctures:

Past critiques of HI have focused on at least two issues that may have contributed to the limited use of path dependence as an explanatory mechanism. The first is a perceived over-reliance by HI on exogenous shock as a necessary constituent for explaining institutional formation and change via punctuated equilibrium theory (PET), and a perceived inability to explain change in terms of concurrent endogenous institutional factors (Harty Citation2005, 59). This characterisation of HI suggests that decision pathways can only be surmounted via exogenous shock, and that path contingency may be poorly equipped to explain institutional change in its absence. Yet, as Koning (Citation2016, 640) notes, much institutionalist literature in the last 20 years has emphasised the influence of endogenous institutional characteristics on decision pathways and policy change (e.g. Rixen and Viola Citation2015, 305). Moreover, the PET that has often been wielded by HI to explain the impact of exogenous shock, is by no means dependent on this concept. As Cairney (Citation2013, 147) notes, PET ‘focuses on the ways in which institutions process information disproportionately to produce huge amounts of small, and small amounts of huge policy changes’. Exogenous shock, under contemporary interpretations of PET, is but one driver of possible change amongst a variety, albeit one that has particular relevance for disaster risk governance.

More importantly, perhaps, this critique unduly simplifies the relationship between institutions and exogenous variables. As Harty (Citation2005, 60) argues, the distinction between discrete exogenous and endogenous factors is less useful than once assumed:

it is worth considering the possibility that in some cases the line between exogeneity and endogeneity is in fact blurred. An exogenous shock might emerge in response to factors that are endogenous to an institutional system.

As Stark (Citation2018, 26) notes, institutionalist analysis of disaster risk governance has good reasons for retaining exogenous shock in its conceptual framework. However, the extent to which exogenous shocks are conceptually useful in isolation from endogenous factors when explaining policy reform for disaster management, appears substantially diminished. One cannot understand institutional change in the Queensland case without considering the interplay between both endogenous path contingent arrangements and consecutive exogenous shocks. By enhancing our understanding of institutions in a way that accounts for path contingent mechanisms, I argue, we can augment existing institutional theories of change. Doing so, I argue, enhances the utility of PET for understanding the interplay between exogenous and endogenous factors and, thereby, the range and likelihood of alternative potential post-crisis reforms.

A second critique of HI relevant for the viability of path contingency concerns a perceived over-reliance on the concept of the critical juncture. On this view, HI is oriented to explain stability and stasis at the expense of understandings of change (e.g. James Citation2016, 89-90; Bell Citation2011, 885; Peters, Pierre, and King Citation2005, 1277). A counterargument is that gradual incrementalism is also a key characteristic of both stability and change of a sort that does not necessitate critical junctures (Harty Citation2005, 61). Nonetheless, for the specific application of HI to disaster risk and natural resource management, there is little doubt that critical junctures play a role in policy reform given the inevitable impact of extreme events on institutional function (Howes et al. Citation2015). Taking Stark (Citation2018, 26) and others’ proposal that punctuated change, incremental change and no change at all are equally conceivable outcomes of disaster-induced critical junctures, and given Soifer’s (Citation2012) important characterisation of permissive and productive conditions for explaining critical junctures, I argue that decision pathways provide an important means to understand the propensity for change as much as for stability.

As seen in the Queensland case, without accounting for path contingencies arising from considerations of space and place, Stark’s analysis only goes so far as to identify that multiple post-disaster outcomes were conceivable; it does not identify which outcomes were more or less likely, and why. Taking path contingencies into consideration, however, understandings of stability and change appear to go hand in glove. One cannot fully understand or predict change without also understanding the contingencies influencing preceding or concurrent institutional continuity (Koning Citation2016, 641). For disaster risk governance, augmented understandings of space and place and their influence upon institutional function helps us to understand the path contingencies that influence the extent to which crisis-induced critical junctures result in either punctuated or incremental change.

The Queensland case demonstrates a direct line of contingency between physical interventions in space, compounding path contingent policy/regulatory provisions and stable institutional arrangements which, in turn, present significant impediments to the timing, range and likelihood of potential reforms that may be considered by policy decision-makers at critical junctures. Queensland’s water management reforms arose from a combination of punctuations and incrementalism, depending on political and technical feasibility at any given point. Accounting for the interactions between physical arrangements and institutional functions in the analysis above, the Queensland case indicates that an appreciation of path contingencies can better account for continuity and change that accommodates the possibility of, and opportunities arising from, post-crisis critical junctures, without being overdependent on those junctures for the purposes of explanation. Contemporary elaboration of HI is not wholly dependent upon critical junctures for its conceptual or explanatory coherence (Koning Citation2016, 643–647), much as contemporary PET makes ample provision for policy reform in the absence of punctuation (Baumgartner, Jones, and Mortensen Citation2017, 59, 61). However, crisis events and the opportunities that arise in their aftermath are inevitable constituents of disaster risk governance, and therefore the concept of critical juncture will continue to be important for understanding both institutional stasis and reform in that context.

On the generalisability of path contingency

Finally, it seems worth reflecting on the worth of path contingency as an explanatory mechanism of institutional stasis and change across a broader range of contexts and portfolios than just disaster risk or infrastructure management. This case-study identifies a clear interaction between institutions’ material interventions in space, and the propensity (or otherwise) for governance reform. One might envisage similar path contingencies evident across a range of publicly administered infrastructure that would enhance our understanding of the roles played by antecedent material conditions in processes of institutional reform. Yet, as Johnson’s (Citation2003) analysis showed, this concept has applicability beyond the material contingencies of infrastructure management demonstrated here. Applied judiciously, I propose, path contingency might allow greater understanding of the relative influences of antecedent conditions in comparison to agentic variables, in a way that may be appealing for non-HI scholars wary of over-emphasising (and yet not disregarding) the structural determinants of institutional stasis and change. Much as Johnson (Citation2003) achieved with her analysis, path contingency provides an intermediary mechanistic device allowing agency to credibly retain its status as primary independent variable. Alternatively, path contingency may provide additional utility for HI scholarship, as a counterpoint to path dependency, thereby allowing more nuanced characterisations of the relative influence of structural variables across a range of antecedent conditions and decision pathways. These contrasting applications point to a potential for further case-study research across a range of non-infrastructure-related governance concerns, to explore the extent to which this concept may be usefully applied.

Conclusion

This paper shows that accounting for path contingency can allow for a more meaningful examination of the influence of antecedent conditions and decision pathways on the institutional outcomes associated with infrastructure management and disaster risk governance. When interpreted as a non-deterministic mechanism influencing the likelihood of institutional stability or reform, path contingency allows for enhanced understanding of human interventions in physical space and their impact on the structure and function of responsible institutions. By accounting for path contingencies, infrastructure-focused institutionalist research might better integrate exogenous and endogenous influences and the extent to which critical junctures in the aftermath of exogenous shocks are likely to result in punctuated or incremental change. On the basis of this case-study, I propose that path contingency may also find useful application across a broader range of institutionalist analyses to help accommodate considerations of both structure and agency in policy reform.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Peter Tangney

Peter Tangney is Assistant Professor of Public Policy and Governance in the Department of Political Science at University of Amsterdam, Netherlands. His research interests include disaster risk and environmental governance; he worked for ten years in Australia exploring these challenges.

Notes

1 A significant exception being Elinor Ostrom’s Institutional Analysis and Development Framework (Ostrom, Gardner, and Walker Citation1994)

References

- Baumgartner, Frank R., Bryan D. Jones, and Peter B. Mortensen. 2018. “Punctuation Equilibrium Theory: Explaining Stability and Change in Public Policymaking.” In Theories of the Policy Process, edited by Christopher M. Weible and Paul A. Sabatier, 4th ed., 55–102. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429494284

- Bell, Stephen. 2011. “Do we Really Need a New ‘Constructivist Institutionalism’ to Explain Institutional Change?” British Journal of Political Science 41 (4): 883–906. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123411000147.

- Berkhout, Frans. 2002. “Technological Regimes, Path Dependency and the Environment.” Global Environmental Change 12 (1): 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-3780(01)00025-5.

- Cairney, Paul. 2013. Understanding Public Policy - Theories and Issues. 2nd ed. London, UK: RedGlobe Press. https://doi.org/10.1111/1478-9302.12016_5

- Choi, Chang G., Sugie Lee, Heungsoon Kim, and Eun Y. Seong. 2019. “Critical Junctures and Path Dependence in Urban Planning and Housing Policy: A Review of Greenbelts and New Towns in Korea’s Seoul Metropolitan Area.” Land Use Policy 80: 195–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.09.027.

- Coe, Neil M. 2011. “Geographies of Production I: An Evolutionary Revolution?” Progress in Human Geography 35 (1): 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510364281.

- Cook, Margaret 2016. “Damming the ‘Flood Evil’ on the Brisbane River.” History Australia 13 (4): 540–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/14490854.2016.1231161.

- Davidescu, Simona, Ralitsa Hiteva, and Tomas Maltby. 2018. “Two Steps Forward, one Step Back: Renewable Energy Transitions in Bulgaria and Romania.” Public Administration 96 (3): 611–625. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12522.

- Djelic, Marie-laure, and Sigrid Quack. 2007. “Overcoming Path Dependency: Path Generation in Open Systems.” Theory and Society 36 (2): 161–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-007-9026-0.

- Gains, Francesca, Peter C. John, and Gerry Stoker. 2005. “Path Dependency and the Reform of English Local Government.” Public Administration 83 (1): 25–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0033-3298.2005.00436.x.

- Harty, Siobhán 2005. “Theorizing Institutional Change.” In New Institutionalism: Theory and Analysis, edited by André Lacours, 1–26. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press. https://doi.org/10.3138/9781442677630-003

- Hay, Colin 2011. “Interpreting Interpretivism Interpreting Interpretations: The new Hermeneutics of Public Administration.” Public Administration 89 (1): 167–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2011.01907.x.

- Heazle, Michael, Peter Tangney, Paul Burton, Michael Howes, Deana Grant-Smith, Kim Reis, and Karen Bosomworth. 2013. “Mainstreaming Climate Change Adaptation: An Incremental Approach to Disaster Risk Management in Australia.” Environmental Science & Policy 33: 162–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2013.05.009.

- Howes, Michael, Peter Tangney, Kim Reis, Deanna Grant-Smith, Michael Heazle, Karen Bosomworth, and Paul Burton. 2015. “Towards Networked Governance: Improving Interagency Communication and Collaboration for Disaster Risk Management and Climate Change Adaptation in Australia.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 58 (5): 757–776. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2014.891974.

- Howlett, Michael 2009. “Process Sequencing Policy Dynamics: Beyond Homeostasis and Path Dependency.” Journal of Public Policy 29 (3): 241–262. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X09990158.

- James, Toby S. 2016. “Neo-Statecraft Theory, Historical Institutionalism and Institutional Change.” Government and Opposition 51 (1): 84–110.

- Jenkins-Smith, Hank C., Daniel Nohrstedt, Christopher M. Weible, and Karin Ingold. 2018. “The Advocacy Coalition Framework: An Overview of the Research Program.” In Theories of the Policy Process, edited by Christopher M. Weible and Paul A. Sabatier, 4th ed., 135–172. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429494284

- Johnson, Juliet 2003. “Past” Dependence or Path Contingency? Institutional Design in Postcommunist Financial Systems.” In Capitalism and Democracy in Central and Eastern Europe, edited by Grzegorz Ekiert and Stephen E. Hanson, 253–316. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Jungblut, Marc, and Jens Jungblut. 2022. “Do Organizational Differences Matter for the use of Social Media by Public Organizations? A Computational Analysis of the way the German Police use Twitter for External Communication.” Public Administration 100(4), 821–840. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12747.

- Kay, Adrian 2005. “A Critique of the use of Path Dependency in Policy Studies.” Public Administration 83 (3): 553–571. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0033-3298.2005.00462.x.

- Koning, Edward A. 2016. “The Three Institutionalisms and Institutional Dynamics: Understanding Endogenous and Exogenous Change.” Journal of Public Policy 36 (4): 639–664. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X15000240.

- Korinek, Rebecca-Lea, and Sylvia Veit. 2015. “Only Good Fences Keep Good Neighbours! The Institutionalization of Ministry–Agency Relationships at the Science–Policy Nexus in German Food Safety Policy.” Public Administration 93 (1): 103–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12117.

- Krasner, Stephen D. 1984. “Approaches to the State: Alternative Conceptions and Historical Dynamics.” Comparative Politics 16 (2): 223–246. https://doi.org/10.2307/421608.

- Levin, Kelly, Benjamin Cashore, Steven Bernstein, and Graeme Auld. 2010. Playing it Forward: Path Dependency, Progressive Incrementalism, and the ‘Super Wicked’ Problem of Global Climate Change. Chicago, IL: The International Studies Association Convention. USA February 28-March 3. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi = 10.1.1.464.5287&rep = rep1&type = pdf.

- Meecham, Megan 2009. Path Dependency of Infrastructure: Implications for the Sanitation System of Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Masters Thesis, Stockholm University, Sweden. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid = diva2%3A329209anddswid = −938.

- Ostrom, Elinor, Roy Gardner, and Jimmy Walker. 1994. Rules, Games, and Common Pool Resources. Ann Arbor MI: University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.9739.

- Page, Scott E. 2006. “Path Dependence.” Quarterly Journal of Political Science 1 (1): 87–115. https://doi.org/10.1561/100.00000006.

- Peters, B. Guy 2019. Institutional Theory in Political Science: The ‘New Institutionalism’. Washington, DC, USA: Pinter Press. https://doi.org/10.2478/nispa-2019-0024

- Peters, B. Guy, Jon Pierre, Desmond S. King. 2005. “The Politics of Path Dependency: Political Conflict in Historical Institutionalism.” The Journal of Politics 67: 1275–1300.

- Pierson, Paul 2000. “Increasing Returns, Path Dependence, and the Study of Politics.” American Political Science Review 94 (2): 251–267. https://doi.org/10.2307/2586011.

- Queensland Floods Commission of Inquiry [QFCI]. 2011. Queensland Floods Commission of Inquiry: Interim Report (August 2011). Queensland Floods Commission of Inquiry. http://www.floodcommission.qld.gov.au/publications/interimreport.

- Queensland Floods Commission of Inquiry [QFCI]. 2012. Queensland Floods Commission of Inquiry: Final Report (March 2012). Queensland Floods Commission of Inquiry. www.floodcommission.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/11698/QFCI-Final-Report-March-2012.pdf.

- Rixen, Thomas, and Lora A. Viola. 2015. “Putting Path Dependence in its Place: Toward a Taxonomy of Institutional Change.” Journal of Theoretical Politics 27 (2): 301–323. https://doi.org/10.1177/0951629814531667.

- Sarigil, Zeki 2015. “Showing the Path to Path Dependence: The Habitual Path.” European Political Science Review 7 (2): 221–242. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773914000198.

- Smith, Adrian, Andy Stirling, and Frans Berkhout. 2005. “The Governance of Sustainable Socio-Technical Transitions.” Research Policy 34 (10): 1491–1510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2005.07.005.

- Soifer, Hillel D. 2012. “The Causal Logic of Critical Junctures.” Comparative Political Studies 45 (12): 1572–1597.

- Sorensen, Andre 2015. “Taking Path Dependence Seriously: An Historical Institutionalist Research Agenda in Planning History.” Planning Perspectives 30 (1): 17–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2013.874299.

- Sorensen, André 2018. “Multiscalar Governance and Institutional Change: Critical Junctures in European Spatial Planning.” Planning Perspectives 33 (4): 615–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2018.1512894.

- Stark, Alastair 2018. “New Institutionalism, Critical Junctures and Post-Crisis Policy Reform.” Australian Journal of Political Science 53 (1): 24–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/10361146.2017.1409335.

- Supreme Court of New South Wales. 2019. "Judgment – Queensland Flood Class Action: 10.00 AM (AEDT) Friday 29 November 2019." https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YJXVTEg7TT4&list=WL&index=27&t=0s.

- Tangney, Peter 2015. “Brisbane City Council’s Q100 Assessment: How Climate Risk Management Becomes scientised.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 14 (4): 496–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2015.10.001.

- Tangney, Peter 2017. Climate Adaptation Policy and Evidence: Understanding the Tensions Between Politics and Expertise in Public Policy. London, UK: Routledge-Earthscan.

- Tangney, Peter 2020. “Dammed if you do, Dammed if you Don’t: The Impact of Economic Rationalist Imperatives on the Adaptive Capacity of Public Infrastructure in Brisbane, Australia and Cork, Ireland.” Environmental Policy and Governance 30 (6): 359–372. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1893.

- Thelen, Kathleen 1999. “Historical Institutionalism in Comparative Politics.” Annual Review of Political Science 2 (1): 369–404. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.2.1.369.