ABSTRACT

To understand human prosocial behaviour, one must consider not only the helpers and the requesters, but also the characteristics of the beneficiaries. To this aim, this articles reviews research on beneficiary effects in prosocial decision making, which implies that some human lives are valued higher than others. We focus on eight beneficiary attributes that increase willingness to help: (1) Temporal proximity, (2) Young age, (3) Female gender, (4) Misery, (5) Innocence, (6) Ingroup, (7) Identifiability (8) High proportion. We demonstrate that different psychological mechanisms explain different beneficiary effects, that the size and direction of beneficiary effects varies as a function of response mode (separate evaluation, joint evaluation, or forced choice), and outcome measure (attitudes or helping behaviour). We propose that beneficiary attributes differ in their evaluability, justifiability, and prominence, and conclude by discussing theoretical, moral, and applied aspects of beneficiary effects.

Beneficiary effects imply that some individuals or groups in need are consistently valued higher – and therefore helped more – than others with the same need due to attributes differentiating the potential beneficiaries.Footnote1 Specifically, we showcase eight beneficiary effects that have attracted considerable attention from researchers: (1) The temporal effect (current beneficiaries are valued higher than beneficiaries in the future). (2) The age effect (child and teenage beneficiaries are valued higher than adult beneficiaries). (3) The gender effect (female beneficiaries are valued higher than male beneficiaries). (4) The misery effect (poor and sad beneficiaries are valued higher than rich and happy beneficiaries). (5) The innocence effect (moral beneficiaries in need because of bad luck are valued higher than immoral beneficiaries in need because of their bad decisions). (6) The ingroup effect (beneficiaries from the same social group as the helper are valued higher than beneficiaries from other social groups). (7) The identifiability effect (identified beneficiaries are valued higher than statistical beneficiaries). (8) The proportion effect (beneficiaries presented as part of a smaller group are valued higher than beneficiaries presented as part of a larger group).

We first define the concept of beneficiary effects and explain the significance of research on this topic. Next, we summarise empirical evidence for each of the eight beneficiary effects, and suggest that different effects are primarily driven by different psychological mechanisms (emotional reactions, perceived impact, and personal responsibility), and that beneficiary attributes differ in their relative evaluability (i.e., whether the attribute is interpretable without comparison), justifiability (i.e., whether the attribute is perceived as morally relevant), and prominence (i.e., whether the attribute influences choices more than valuations). We conclude with a forward-looking discussion on theoretical and applied research on beneficiary effect, a reflection on the moral implications of (un)equal valuations of lives, and the promises and pitfalls of investigating beneficiary effects in different contexts. Key terms used in the review are explained in .

Table 1. Key terms used in this review.

Beneficiary effects and Charitable Triad Theory

Helping is a social behaviour typically involving multiple actors. Helping can be done in various ways (such as volunteering or blood donations), but charitable giving is one of the most investigated manifestations of helping. According to the Charitable Triad Theory (Chapman et al., Citation2022), the identity and characteristics of (1) benefactors (those offering help), (2) fundraisers (those requesting help), and (3) beneficiaries (those who benefit from the help given) together influence helping decisions. This review focuses on beneficiary effects, or how attributes (or characteristics) of the beneficiaries can promote or inhibit charitable giving as well as other forms of helping.

There is already ample evidence of benefactor effects, implying that some people are generally more inclined to help than others (Casale & Baumann, Citation2015; Pittarello et al., Citation2023; Wiepking & Bekkers, Citation2012). To exemplify, women help more often than men (Einolf, Citation2011; Mesch et al., Citation2011), older people help more than the young (Steinberg et al., Citation2005), and the educated and religious help more than non-educated and atheists (Bekkers & Wiepking, Citation2011). Individual differences in personality (e.g., Bekkers, Citation2006; Graziano et al., Citation2007), ideology and worldviews (e.g., Margolis & Sances, Citation2017; Nilsson et al., Citation2020), and trust (Chapman et al., Citation2021) also represent benefactor attributes that can predict helping. Similarly, potential benefactors can become more helpful after being induced to feel a specific emotion or when asked to use a specific way of thinking. For instance, people donate more after their personal norms have been made salient (e.g., by stating what the right thing to do is; Capraro & Perc, Citation2021; Capraro et al., Citation2019), and after they have consumed alcohol (Karlsson et al., Citation2021).

There are also many studies focusing on fundraiser effects, which occur when the behaviour, identity, or reputation of the person (or organisation) asking for help influence helping (Bhati & Hansen, Citation2020; Goswami & Urminsky, Citation2016). For instance, direct requests presented face-to-face or by personalised email affect generosity differently than indirect requests such as media advertising (Cain et al., Citation2014; Castillo et al., Citation2014, and more attractive and charismatic fundraisers or observers are more likely to successfully persuade people (especially men) to donate to charitable causes (Chaiken, Citation1979; Landry et al., Citation2006; Raihani & Smith, Citation2015). In a peer-to-peer context, actions that make it clear that a fundraiser is highly invested in the outcome – such as asking for gifts through more channels and personalising the fundraising page – are associated with greater fundraising success (Chapman et al., Citation2019).

There is less research devoted to understanding which beneficiaries (recipients) elicit more donations. A recent systematic review of research on charitable giving over the last 40 years revealed that 75% of the reviewed research focused on the benefactor, 15% focused on the fundraiser, but only 8% considered beneficiaries (Chapman et al., Citation2022).Footnote2 This suggests that beneficiary effects are understudied in charitable giving and that new insights are needed. In this review, we suggest that one way to better understand beneficiary effects in charitable giving is to examine how beneficiaries influence other types of prosocial decisions (such as health care prioritisation and choices in moral dilemmas).

Eight beneficiary effects

In the following sections, we introduce eight beneficiary effects: (1) the temporal effect, (2) the age effect, (3) the gender effect, (4) the misery effect, (5) the innocence effect, (6) the ingroup effect, (7) the identifiability effect, and (8) the proportion effect (see ). These effects do in no way constitute an exhaustive list of beneficiary effects, but are selected because they have received significant empirical attention (by us and by others), which allows us to explicitly compare them to one another.Footnote3 The eight beneficiary effects outline broad tendencies in which some human lives are typically valued over others.

Table 2. Summary of the eight beneficiary effects, including beneficiary attributes that increase helping, with their suggested psychological mechanisms and profile in terms of evaluability (EV), justifiability (JU), and prominence (PR).

Each of the eight beneficiary attributes can be manipulated independently, but we acknowledge that some of them typically co-occur in real life (such as age and innocence, or existence and ingroup). Likewise, some of the effects are umbrella concepts and contain more than one beneficiary attribute (see ). We elaborate these nuances when discussing each beneficiary effect below.

The temporal effect

The temporal effect occurs when beneficiaries who exist at the present moment are valued higher than future beneficiaries (people who will exist sometime in the future; Halpern et al., Citation2020; O’Donoghue & Rabin, Citation2015). If exemplified within a cancer context – which we will use to illustrate each effect in turn – the temporal effect predicts that people will be more willing to donate money to an organisation fighting cancer if doing so can cure patients currently suffering from cancer (e.g., by trialling a promising treatment), than if it can cure people who will suffer from the same type of cancer 20 years from now (e.g., by funding research to develop future treatments). To quantify the size of the temporal effect, one study estimated that one beneficiary today is valued the same as six people from 25 years into the future (Cropper et al., Citation1994).

The temporal effect is related to intertemporal choices and to the discounted utility model which suggests that positive consequences in the future are perceived as weaker by their delay (Bischoff & Hansen, Citation2016; Cairns & van Der Pol, Citation1997; Chapman & Elstein, Citation1995; Samuelson, Citation1937). Whereas suffering experienced at this very moment is certain, there is always some amount of uncertainty whether future suffering will occur or not (Wade‐Benzoni, Citation2008), and this can decrease the perceived impact of helping. In line with this, peoples’ most common post-hoc justifications for preferring to save present beneficiaries rather than future beneficiaries was that they hoped that new solutions would be invented in the meantime (Cropper et al., Citation1992). The second most common justification was that the helper’s friends and family members currently alive have a larger chance of profiting from help provided now, than from help provided in the future, suggesting that the temporal effect could partially be explained by the ingroup effect summarised later.

The temporal effect could also be understood in terms of levels of construal (Trope & Liberman, Citation2012). Whereas existing beneficiaries are temporally proximate and concretely perceived, future beneficiaries are temporally distant and therefore interpreted in more abstract terms. Relatedly, the temporal effect is likely a contributing psychological barrier for combatting climate-related threats as the primary beneficiaries of this type of helping are the future generations (Wade Benzoni & Tost, Citation2009). Although most people value the lives and well-being of future generations, few are prepared to sacrifice the well-being of present beneficiaries in favour of future beneficiaries.

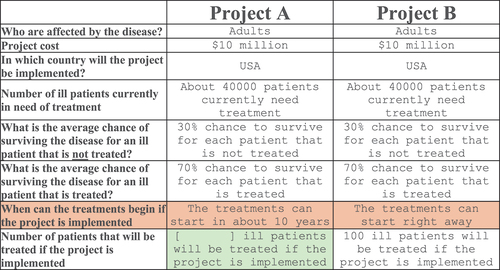

The temporal effect is robust, but studies show that the degree of temporal discounting varies substantially as a function of how the question is asked (Frederick, Citation2003; Johannesson & Johansson, Citation1997). In Erlandsson et al. (Citation2020), we tested the temporal effect (and four other beneficiary effects) in two response modes; an initial matching task and a subsequent choice task. Participants (Swedish undergraduate students in Study 1, US MTurk participants in Study 2) were exposed to a medical dilemma including two helping projects. In the initial matching task, participants were asked to write a number in a green box in order to make the two projects exactly equally attractive and worth implementing (see ). A participant who responded “100” in this task expresses that future patients are equally valuable as existing patients, whereas a participant responding “150” (or any number over 100) expresses that existing patients are more valuable as a greater number of treated future patients is necessary to make Project A equally attractive as Project B which can treat 100 existing patients. Most participants valued existing patients higher than future patients in this matching task (72.2% in Study 1 and 74.9% in Study 2, see left column of ).

Figure 1. Example of the matching task in the temporal effect dilemma in Erlandsson et al. (Citation2020).

Table 3. Distribution of preferences in each dilemma expressed with matching and with forced choice in Erlandsson et al. (Citation2020). For preferences expressed with matching, “equally valued” denotes the proportion of participants who wrote 100 in the blank box in each matching task. For preferences expressed with forced choice, different rows illustrate how participants who expressed different preferences in the matching task choose during the choice task.

At a later point, the same participants completed the choice tasks, where they read the dilemma again and were asked to choose which of the two helping projects they would implement if they had to choose one. Importantly, the number written by that very participant during the matching task was inserted in that box, implying that each participant was asked to choose between two helping projects that she/he had previously matched to be equally worth implementing. Participants had to choose one project but were explicitly encouraged to flip a coin or use an online number generator in case they found the two projects equally worth implementing (whether they did so or not was not recorded). Logically, if participants were indifferent when faced with the two matched projects, they would be equally likely to choose either of the projects which would render a 50–50 distribution on a group level. Despite choosing between two projects earlier matched as equally attractive, a large majority preferred the project helping existing patients (see right column in ).

In another study (Erlandsson, Citation2021), we systematically tested the direction and size of the temporal effect (and six other beneficiary effects) in three different response modes (separate evaluation, joint evaluation and forced choice). Moreover, we studied the “weak” and the “strong” form of each effect (Mata, Citation2016). To illustrate, the weak temporal effect is present when a project helping existing patients is systematically preferred over an otherwise identical project helping equally many future patients (equal efficacy, e.g., helping 6 now vs. 6 in one year). In contrast, the strong temporal effect is present when a project helping fewer existing patients is systematically preferred over a project helping more future patients (unequal efficacy, e.g., 4 now vs. 6 in one year). When a weak effect occurs, it is possible to claim that the differing beneficiary attribute (here temporal proximity) is merely a tiebreaker that decides preferences when everything else is equal. When a strong effect occurs, this implies that the differing beneficiary-attribute overrides the efficacy attribute (here the number of beneficiaries).Footnote4

Participants who expressed preferences in the separate evaluation mode were randomly assigned to rate one out of three helping projects (6 existing, 4 existing, or 6 future patients). Rating of the single help project was done by responding to three questions (on a 0–100 visual analogue scale), and these questions were later aggregated into a general project attractiveness rating: (I) How good does Project A seems to you? (II) How worthy of financing does Project A seems to you? (III) How much do you approve of implementing Project A? The weak temporal effect was tested by comparing the attractiveness of the projects helping 6 existing and 6 future patients (equal efficacy), whereas the strong temporal effect was tested by comparing the projects helping 4 existing against 6 future patients (unequal efficacy).

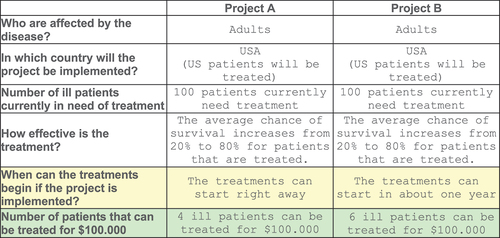

Participants assigned to the joint evaluation mode rated two helping projects presented next to each other. Half of them rated the projects helping 6 existing and 6 future patients (weak temporal effect), whereas the other half rated the projects helping 4 existing and 6 future patients (strong temporal effect, see ). Evaluation was done with the same scales as in separate evaluation. Participants assigned to the forced choice mode read the same information as participants in the joint evaluation mode but were simply asked to choose which of the two helping projects they preferred to implement.

Figure 2. Two helping projects in joint evaluation or forced choice in Erlandsson (Citation2021).

As seen in , the projects helping existing and future beneficiaries were rated as similarly attractive when evaluated separately, but the project helping existing beneficiaries was rated as more attractive, and chosen more often, when the projects were presented next to each other. When forced to choose, 79.7% even preferred the project helping 4 patients now over the project helping 6 patients in the future.

The age effect

The age effect occurs when the lives of children and teenagers are valued higher than the lives of adults (Cropper et al., Citation1994; Goodwin & Landy, Citation2014; Li et al., Citation2010; Moche et al., Citation2023; Rodríguez & Pinto, Citation2000). The age effect illustrates ageism, which implies discrimination of people based on their age (Palmore, Citation2005). People of all age-groups can be the victims of ageism, but in health-care situations it is typically manifested by younger beneficiaries being prioritised over older beneficiaries in similar need. If applied to the cancer-context introduced above, it predicts that people will be more willing to donate money to an organisation devoted to fighting child cancer, than to an organisation devoted to fighting cancer among adults.

There is ample evidence for this effect; in their moral machine experiment, Awad et al. (Citation2018) asked millions of people from 233 countries to judge how autonomous (self-driving) cars should behave when they were faced with moral dilemmas, which always implied that someone would get killed. They found that people have strong preferences for cars being programmed to spare young children, infants, and even pregnant women, even at the cost of other people. In another study, participants read a charity appeal that would help either child or adults beneficiaries suffering from bullying or cancer and were more likely to donate to children (Moche & Västfjäll, Citation2021). Kawai et al. (Citation2014) report that it is seen as less acceptable to sacrifice a 5-year-old than a 70-year-old, to save five unknown others, and if a child and an adult are sick and only one could receive treatment, most people choose to help the child (Lewis & Charny, Citation1989). Bachke et al. (Citation2014) find that people donate more to aid projects helping children (vs. adults), and that this effect is stronger among men. Chapman et al. (Citation2020) found that when donors are asked to justify why they support their favourite charity, it was very common to mention that the organisation helps children whereas it was rare to mention adults or elders.

In our own work (Erlandsson et al., Citation2020), we tested the age effect using the initial matching and subsequent choice paradigm described above. Many participants (33.3% in Study 1, 56.8% in Study 2) stated that projects helping 100 children and 100 adults are equally attractive, but when the same participants were forced to choose between the two matched projects, the vast majority implemented the project helping children (Erlandsson et al., Citation2020, see ). In Erlandsson (Citation2021), a project helping 6 children was preferred over an identical project helping 6 adults when the projects were presented side by side (but not when evaluated separately), whereas a project helping 4 children was preferred over a project helping 6 adults only when people were forced to choose (Erlandsson, Citation2021, see ).

There are several possible reasons for the age effect (Goodwin & Landy, Citation2014; Tsuchiya et al., Citation2003). One is that the evolved instinct to protect one’s offspring can extrapolate to behaviour towards children in general. Another is that children are perceived as more dependent and worthier of care than adults (Chapman et al., Citation2022). Young children are rarely held responsible for their own plight (Back & Lips, Citation1998) implying that the age effect can partially be explained by the innocence effect presented below. A third, more utilitarian, impact-based reason for helping children is that the anticipated number of quality-adjusted life years (QALY; Bravo Vergel & Sculpher, Citation2008) is higher for a child than for an adult, and people perceive the death of a 19-year-old as more unjust than the death of a 79-year-old (Chasteen & Madey, Citation2003).

The gender effect

The gender effect typically occurs when female beneficiaries are valued higher than male beneficiaries. Both women and men (and other gender identities) can be the victims of sexism which implies discrimination based on a person’s sex or gender identity. Traditionally, men have enjoyed more privileges and freedoms, and there are still many explicit rules and implicit norms that limit women’s opportunities even in modern western societies. Still, gender-based discrimination seems to go in the opposite way in helping situations and moral dilemmas (Dufwenberg & Muren, Citation2006; Eagly & Crowley, Citation1986). For instance, the Birkenhead drill “Women and children first” suggests that female passengers should be prioritised when there are not enough lifeboats on a sinking ship (Elinder & Erixson, Citation2012). The gender effect predicts that people in general will donate more money to an organisation devoted to helping exclusively women (e.g., fighting ovarian cancer) than to an organisation devoted to helping exclusively men (e.g., fighting testicular cancer).

Consistent with this, people express a preference for autonomous cars saving women’s lives over men’s lives (Awad et al., Citation2018), people donate more to women in dictator games (Holm & Engseld, Citation2005), and propose more severe punishment for offenders when the victim was a woman than when it was a man (Curry et al., Citation2004; Goodwin & Benforado, Citation2015; Herzog, Citation2017). In the allocation-justification study by Chapman et al. (Citation2020), several participants justified giving to their favourite organisation by mentioning that it focused on women and girls, but no participants mentioned that it focused on men or boys.

In Erlandsson et al. (Citation2020) we found that although over 90% of the participants matched help projects so that male and female patients were equally valuable, over 80% of them later chose to implement the project helping 100 females over the project helping 100 males (see ). Likewise, a project helping 6 males was rated as equally attractive as a project helping 6 females, but when forced to pick one project, over 75% chose to help females (Erlandsson, Citation2021, see ). However, the same study showed that there was no sign of a strong gender effect. Most participants clearly preferred a project helping 6 male patients over a project helping 4 female patients. These results suggest that equal valuation is normative but, when pressed to decide between helping men and women, most default to help women.

One explanation of the gender effect is that women are more motivated to help other women because of gender-based ingroup favouritism or self-interest (i.e., women may donate more to ovarian cancer research and men more to testicular cancer research), but men also seem to help women more than men (Bachke et al., Citation2014; Erlandsson, Citation2021; Holm & Engseld, Citation2005). One reason for this is that helping by men can be used to signal affluence and agreeableness towards women (Raihani & Smith, Citation2015; Van Vugt & Iredale, Citation2013), and therefore serve to signal high status (Nadler, Citation2002). The gender effect is also likely driven by benevolent sexism where attitudes towards women seem positive but carry the connotation that women are inferior to men because they are more fragile, less competent and warrant protection (Glick & Fiske, Citation1997). Consequently, because of gender stereotypes, both men and women tend to perceive females as less aggressive, more delicate, and more disadvantaged than men, and therefore both more deserving and in more need of protection (Bradley et al., Citation2019; Paolacci & Yalcin, Citation2020); evoking in turn the innocence and misery effects discussed below. One study found that female victims of cyberbullying were attributed less blame and were more likely to receive help than male victims (Weber et al., Citation2019), and Chapman et al. (Citation2022) hypothesised that women elicit more donations because they are stereotyped as higher in warmth than men.

The innocence effect

The innocence effect occurs when people who are suffering because of external reasons such as bad luck or other’s mistakes are valued higher than those suffering because of internal reasons such as their own character or bad decisions (Edlin et al., Citation2012; Gross & Wronski, Citation2021; Seacat et al., Citation2007; Weiner, Citation1995). We acknowledge that children and women are typically stereotyped as more innocent than adult men, but to isolate the innocence effect we keep those aspects constant and instead focus on other innocence cues of the beneficiary. Understood this way, the innocence effect predicts that people will: (1) be more motivated to donate when doing so can help cancer patients who suffer despite living a healthy life rather than cancer patients who seemingly got ill because of smoking, drinking, or excessive eating; (2) donate more to treat good-hearted “moral” patients suffering from cancer, than to help “morally questionable” patients such as those with a criminal record; and (3) prefer beneficiaries who are trying to help themselves over beneficiaries who are exclusively relying on others’ help (Body & Breeze, Citation2016; Fong, Citation2007; Weiner, Citation1993).

In line with this, the moral machine experiment revealed that people expressed a weak preference for autonomous cars to save fit over overweight people and a stronger preference to save the lawful (those obeying traffic rules) rather than the unlawful (Awad et al., Citation2018). Similarly, people expressed a greater willingness to donate when a charity advertisement displayed a blameless beneficiary compared to a beneficiary who had self-inflicted harm (by smoking or drunk driving; Shanahan et al., Citation2012). Feeny and Clarke (Citation2007) used archival data to show that Australians donate more money to disasters occurring in “innocent” countries with high political and civil freedom, and Fehse et al. (Citation2015) found that people report feeling less compassion and exhibit less neural activity in areas associated with emotions when hearing about beneficiaries that are perceived as non-innocent. Everything else being equal, victims who already tried to improve their own situation elicit more help than passive victims (Zagefka et al., Citation2011; see also Shurka et al., Citation1982), and people to some extent dehumanise beneficiaries who partially caused their own plight (e.g., drug addicts) to regulate their emotions about not helping (Cameron et al., Citation2015). Bennett and Kottasz (Citation2000) go so far as recommending that charities should avoid references to warfare, which may be interpreted as a human-caused disaster.

In our own studies, we found no clear group-level preferences when participants matched a project helping patients who smoke and drink with a project helping patients who exercise and eat healthy (Erlandsson et al., Citation2020), but when the same participants were asked to choose, a clear majority implemented the project helping “innocent” patients (see ). Likewise, in Erlandsson (Citation2021), the preference for the project helping 6 “gymmers” over 6 “smokers” was clearly stronger when people had to choose one, than when they rated how attractive each project was. The project helping 4 gymmers was preferred slightly more often than a project helping 6 smokers when people were forced to choose, but not when rating project attractiveness (see ).

As noticed, different situational antecedents can increase perceived innocence, including absence of causal responsibility (the beneficiary did not cause his/her own plight), absence of previous immoral behaviour (the beneficiary is a good person), and absence of learned passiveness (the beneficiary is trying to help oneself). The motive for the reduced helping towards beneficiaries low on innocence might be different depending on the antecedents. For instance, we would perhaps help non-smokers (vs. smokers) with cancer less because we believe it will have low impact, while we would perhaps help child-molesters with cancer less because we think they deserve to suffer.

The misery effect

The misery effect occurs when unprivileged beneficiaries are valued higher than privileged beneficiaries (Brañas-Garza et al., Citation2007; Paolacci & Yalcin, Citation2020). This effect occurs when people behave more prosocially towards beneficiaries from a lower social class (Van Doesum et al., Citation2017, Citation2022), and towards beneficiaries appearing distraught and sad, rather than safe and happy (Small & Simonsohn, Citation2009). In our example, it predicts that people will donate more money if they think doing so will benefit cancer patients worse off (financially or psychologically speaking), than if they think it will benefit cancer patients who are better off.

Behavioural tendencies related to the misery effect include the reference-dependence effect, which means that we are more motivated to help a beneficiary who is perceived to have experienced a loss (e.g., went from perfectly healthy to seriously ill) than a beneficiary who was born with a chronic illness (Small, Citation2010); the dead people effect, which means that people base their disaster responses more on the number of casualties than the number of people in need (Evangelidis & Van den Bergh, Citation2013); and the negative trend effect, which means that we allocate more money to beneficiaries suffering from plights that are perceived as getting worse (vs. getting better; Erlandsson, Hohle et al., Citation2018).

Studies have found that people tend to allocate resources to the beneficiaries and charities who appear worst off and suggest that this is driven by both impact concerns (a belief that they are in a greater need) and by inherent sympathies with the underdog (Bradley et al., Citation2019; Paolacci & Yalcin, Citation2020; Saito et al., Citation2019). In dictator games, people give more money to those with low (vs. high) socioeconomic status (Holm & Engseld, Citation2005), and a suggested reason for this is that people like outcome fairness which imply that they prefer to help fewer poor people over more rich people (even when the poor have partially themselves to blame; Edlin et al., Citation2012). Helping those who are financially or psychologically worst off could be a reasonable rule of thumb in some situations as the increasing marginal utility of additional money is higher among those with less resources. However, excessive reliance on this decision rule can lead to ineffective helping efforts either because the chance of success could be very low if always helping the ones worst off (e.g., in a Triage situation), or because a greater number of people can be helped instead.

In one study, we investigated the misery effect by comparing the effectiveness of negative vs. positive charity appeals (Erlandsson, Nilsson & Västfjäll, Citation2018). Negative appeals describe beneficiaries who are experiencing (or have experienced) severe suffering and try to motivate people to help by inducing distress and feelings of guilt. In contrast, positive appeals portray beneficiaries who already recovered from a plight and try to motivate people to help by inducing happiness and warm glow (the emotional reward of helping others). In a total of four studies, we compared how people reacted and behaved when presented with a negative or a positive charity appeals in various contexts.

We assessed prosocial responses with three outcome variables in each study: (1) attitude towards the appeal (“I liked the ad”), (2) attitude towards the fundraiser (“The ad made me feel angry towards the organisation behind the ad”), and (3) actual donations to the organisation behind the appeal (participants could donate endowed scratch lottery tickets).

Importantly, our different outcome variables pointed in different directions. Specifically, results from all four studies indicated that the positive charity appeals were preferable if operationalising effectiveness as attitudes towards the appeal (people reading the positive appeal liked it better than those reading the negative), or as attitudes towards the organisation (people reading the negative appeal became angrier at the organisation). In contrast, the very same participants donated significantly more lottery tickets if they read the negative rather than the positive appeal in two of the studies (there were no differences in donations in the other two studies). In two follow-up studies, we tested participants’ lay-beliefs of appeal effectiveness and found that people erroneously think that positive appeals will elicit more donations than negative appeals. This suggests that people overuse their own intuitive reaction when reading a charity appeal and predicting how effectively it motivates people to help. A similar pattern was found by Allred and Amos (Citation2018) where a negative shock appeal made people feel more empathy for the beneficiaries but was also anticipated to be less effective in eliciting donations. Based on this, we argue that appeal effectiveness should be measured with actual donation behaviour or at the very least with self-reported donation intention, rather than with attitudes towards the ad or the fundraiser.

The ingroup effect

The ingroup effect occurs when beneficiaries from the helper’s own social group (i.e., ingroup) are valued higher than beneficiaries from other social groups (i.e., outgroups, e.g., Balliet et al., Citation2014; Baron et al., Citation2013; Chapman et al., Citation2020; Duclos & Barasch, Citation2014; Erlandsson et al., Citation2019; Fiedler et al., Citation2018; James & Zagefka, Citation2017; Levine & Thompson, Citation2004; Schwartz-Shea & Simmons, Citation1991). This effect predicts, for example, that people will be more likely to donate money to treat cancer patients who are part of their family (kin-based ingroup), friendship circle (social ingroup), co-partisans (political ingroup), community (proximity-based ingroup), same job or hobby (occupational ingroup), or country (nation-based ingroup) than they are to help cancer-patients part of their outgroups.Footnote5 As noted by Chapman et al. (Citation2022), the ingroup effect (unlike e.g., the age and gender effects) represents the relation between helpers and beneficiaries. Whereas an Australian 3-year-old girl in need is a young female beneficiary for everyone, she is an ingroup beneficiary for helpers in Australia but an outgroup beneficiary for helpers in Sweden.

According to the Social Identity Theory (Tajfel, Citation1974; Tajfel & Turner, Citation2004), people tend to categorise themselves and others as members of different groups, resulting in a classification of others as either ingroup or outgroup members. Different group dimensions can be salient at different times or in different contexts so a person perceived as an outgroup member at one time (a player of the opposing team during a college football game) can be perceived as an ingroup at another (a fellow American).

There are multiple dimensions that predict sense of ingroup such as holding similar opinions (Bilancini et al., Citation2020; Levine et al., Citation2005; Sole et al., Citation1975) and having shared experiences (Small & Simonsohn, Citation2008; Smith & Schwarz, Citation2012; Wiepking, Citation2010; Zagefka et al., Citation2013). Still, shared family-based and geographic social identities were the most spontaneously cited reasons for preferring a specific charity organisation in the study by Chapman et al. (Citation2020), and in our research, we have primarily focused on nation-based (Baron, Citation2012; Baron & Miller, Citation2000), and kin-based ingroups and outgroups (Burnstein et al., Citation1994; Burum et al., Citation2020).

In Erlandsson et al. (Citation2020), we found that although clear majorities (72.8% and 81.4%) matched help projects so that nation-based ingroup and outgroup patients were equally valuable, close to 90% of them later chose to implement the project helping 100 compatriots over the project helping 100 foreigners (see ). Likewise, a project helping 6 compatriots was rated as similarly attractive as a project helping 6 foreigners (in both separate and joint evaluation), but when forced to pick one project, 85% chose to help compatriots (Erlandsson, Citation2021; see ). The same study showed that attractiveness ratings were significantly higher for the project helping 6 foreigners than for the project helping 4 compatriots when evaluated jointly, but that close to 50% helped 4 compatriots rather than 6 foreigners when forced to choose.

A similar pattern was found for the kin-based ingroup effect. The project helping 3 relatives was rated as slightly more attractive than the project helping 3 non-relatives both in separate and joint evaluation, but the preference for helping relatives became much more pronounced when people were forced to choose (Erlandsson, Citation2021; see ). Forced choice also increased the strong ingroup effect. The project helping 3 unknown patients was given a higher attractiveness rating more frequently than the project helping 1 relative when the projects were evaluated jointly, but 70.2% chose the project helping the one relative.

The ingroup effect has been argued to be driven by attitudes (e.g., ingroup-love and outgroup-hate; Brewer, Citation1999; De Dreu et al., Citation2011), beliefs (e.g., anticipated social consequences for oneself; Everett et al., Citation2015), and by a greater perceived duty to help the ingroup (Baron et al., Citation2013; McManus et al., Citation2020). In addition, studies suggest that whereas ingroup-helping is predicted primarily by empathy, outgroup helping seems best predicted by interpersonal attraction (Stürmer & Snyder, Citation2010; Stürmer et al., Citation2005). Social distance (together with temporal distance) is likely one of the most robust predictors of unequal valuations of lives, but preference for the ingroup is typically stronger for universal ingroups such as one’s family, and weaker (and more culturally dependent) for other types of ingroups (e.g., nationality), or for artificially created ingroups (Diehl, Citation1990).

The identifiability effect

The identifiability effect occurs when identified people in need are valued higher than generic or statistical victims (Bergh & Reinstein, Citation2021; Butts et al., Citation2019; Erlandsson et al., Citation2016; Kogut & Ritov, Citation2015; Lee & Feeley, Citation2016; Moche et al., Citation2020). This effect predicts, for instance, that people will donate more money when the beneficiary is an identified cancer patient presented with a name, picture, and background story, then when no beneficiary of cancer treatment is specified. The identifiability effect can come in various forms, and we have previously argued that it can be dissected into three factors: determinedness, vividness, and singularity (Erlandsson, Citation2014).

A determined beneficiary means that it is already decided who the recipient of your help will be (e.g., your blood will be given to a specific person that currently is in need). An undetermined beneficiary means that the identity of the recipient will be determined at a later stage (e.g., your blood will be given to an unspecified person currently in need). In a study by Small and Loewenstein (Citation2003), participants were more likely to donate money to help an unknown poor family if they learned that the family had already been chosen than if they learned that a family is yet to be chosen.

Vividness refers to the amount of personal detail that is provided about the beneficiary. Kogut and Ritov (Citation2005a) demonstrated that adding the age and name of a child increases helping motivation and that an additional picture increases it further (see also Dickert et al., Citation2011; Sah & Loewenstein, Citation2012; Thornton et al., Citation1991). Other ways to increase vividness are to describe the plight of the beneficiaries in graphic terms (Bagozzi & Moore, Citation1994), or to include a narrative and let the beneficiary tell her story in her own words. One can also create a more vivid appeal by anthropomorphising a non-living object (Zhou et al., Citation2019). Participants who saw a tree, bulb, or trash bin with a painted face donated more money to environmental causes than participants who saw these objects without the face (Ahn et al., Citation2014).

The positive effect of determinedness and vividness on helping has been suggested to be stronger when there is a single beneficiary than if there are multiple beneficiaries (Moche et al., Citation2022; Västfjäll et al., Citation2014). An individual but not a group is seen as a psychologically coherent unit (Hamilton & Sherman, Citation1996) and when presenting either eight identified children with name and picture or eight statistical children, there is either no difference, or even a higher helping motivation towards the eight statistical children (Kogut & Ritov, Citation2005a, Citation2005b). In a study by Dickert et al. (Citation2011), one child received more help than five children when they were all identified by pictures, whereas the opposite was the case when the children were described non-vividly as a statistic.

Although interrelated, determinedness, vividness, and singularity are independent attributes. In its most extreme form, the identifiability effect compares helping motivation towards a determined, vividly presented single beneficiary against yet to be determined, statistically presented, multiple beneficiaries. It is also possible to manipulate only determinedness and vividness, whilst keeping the number of beneficiaries constant to test the weak and strong forms of the identifiability effect. In two studies reported in Erlandsson (Citation2021), we did precisely this, and found some support for the weak identifiability effect in all three response modes meaning that a project helping 3 identified patients was typically preferred over an identical project helping 3 statistical patients. However, the pattern dramatically reversed when testing the strong identifiability effect in joint evaluation and in forced choice. When presented next to each other, the project helping 3 statistical patients was rated as much more attractive and chosen much more often than the projects helping 1 identified patient (see ).

The identifiability effect is considered one of the clearest demonstrations of biased prosocial decision making (Slovic, Citation2007; Slovic et al., Citation2017). However, it should be emphasised that although the identifiability effect is influential and widely investigated, its robustness and replicability has been questioned (Hart et al., Citation2018; Lesner & Rasmussen, Citation2014; Majumder et al., Citation2022; Moche, Citation2022; Perrault et al., Citation2015; Wiss et al., Citation2015), and it seems to have several boundary conditions (Ein-Gar & Levontin, Citation2013; Friedrich & McGuire, Citation2010; Kogut, Citation2011; Kogut & Kogut, Citation2013; Kogut & Ritov, Citation2007; Smith et al., Citation2013; Van Esch et al., Citation2021).

The proportion effect

The proportion effect occurs when a beneficiary that is part of a smaller group is valued higher than a beneficiary that is part of a larger group (Baron, Citation1997; Bartels, Citation2006; Erlandsson et al., Citation2014; Kleber et al., Citation2013; Mata, Citation2016). This effect predicts that, for instance, people will donate more to a cancer treatment project estimated to cure all 10 patients currently suffering from a very unusual type of cancer (a rescue proportion of 100%), than to a treatment project estimated to cure 10 (or more) of the tens of thousands of patients suffering from a very common form of cancer (a rescue proportion smaller than 1%).

The proportion and identifiability effects have occasionally been confused as a single identified beneficiary is typically its own reference group. However, it is possible to distinguish the two effects by either keeping the degree of identifiability or the size of the reference group constant. In the early article by Jenni and Loewenstein (Citation1997), proportionality was included as one factor of the identifiable victim effect, and it was found to be the only factor that robustly predicted helping motivation. Participants were more motivated to support a helping project framed as being able to save 25 out of 25 people killed every year at a highway intersection, than to support a project framed as being able to save 25 out of 50,000 people killed at the entire highway. Friedrich et al. (Citation1999) showed that most people think that more lives must be saved to justify a $850 M expenditure if 41,000 lives are at risk compared to when 9,000 lives are at risk, and Fetherstonhaugh et al. (Citation1997) found that each refugee life was valued more when the refugee camp was relatively small (11,000) than when it was large (250,000). Bartels and Burnett (Citation2011) suggested that the proportion effect is stronger when the beneficiaries are perceived as a cohesive group (e.g., a flock of animals) than when they are perceived as a collection of separate individuals.

According to a related phenomenon called pseudoinefficacy, helping motivation is not only a function of the number of people possible to help, but also a function of the number of people not possible to help (Västfjäll et al., Citation2015), implying that knowing about beneficiaries that we cannot save reduces motivation to help beneficiaries that we can help. In a study by Dickert and Slovic (Citation2009), participants expressed lower helping motivation and sympathy towards a single child in need when the child was one among many, than if the child was presented alone.

In two studies reported in Erlandsson (Citation2021), we found the weak proportion effect in all three response modes. Participants rated a project helping 6 out of 6 people in need as more attractive, and chose it more often, than a project helping 6 out of 100 in need. The strong proportion effect clearly emerged in separate evaluation as the mean attractiveness was higher for the project helping 4 out of 4 than for projects helping 6 out of 100, weakened in joint evaluation, and even reversed when people were forced to choose (see ).

The proportion effect (and pseudoinefficacy) implies that we are more likely to prefer interventions that solve the problem at hand (i.e., treat all victims at risk) rather than interventions that do more good but do not solve the problem completely (Li & Chapman, Citation2009; Ubel et al., Citation1996). This can be problematic as there are several problems in the world where the amount of good one can do is high in absolute, but low in proportionate, terms (e.g., spending money on mitigating problem X is a cost-effective way to save many lives, but most of those suffering from problem X will not make it anyway).

Different beneficiary effects are best explained by different psychological mechanisms

As part of his doctoral thesis, the first author and his supervisors set out to investigate if different beneficiary effects are primarily driven by different psychological mechanisms (Erlandsson et al., Citation2014, Citation2015, Citation2017). These articles zoomed in on three beneficiary effects (identifiability, proportion, and ingroup), and on three psychological mechanisms that have been suggested to motivate prosocial behaviour: (1) emotional reactions elicited by learning about the plight of the beneficiaries (Batson, Citation2011; Slovic et al., Citation2017), (2) perceived impact of helping (Caviola, Schubert & Nemirow Citation2020; Duncan, Citation2004), (3) perceived personal responsibility or obligation to help (Bekkers & Ottoni-Wilhelm, Citation2016; Tomasello, Citation2020).

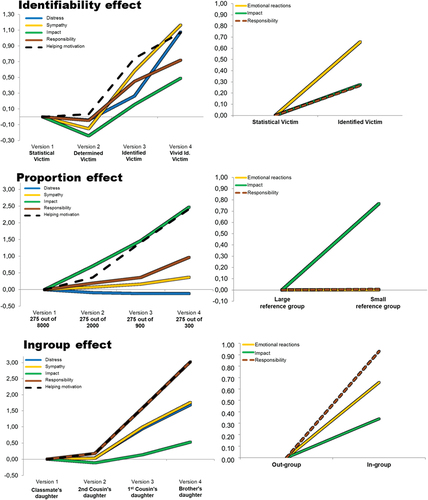

In Studies 1–3 in Erlandsson et al. (Citation2015), situational factors were manipulated within subjects, meaning that participants read four versions of a need description and, after each version, responded to statements such as “I feel intense compassion” (for measuring emotional reactions), “I think one can do a lot of good” (perceived impact), and “I have a moral obligation to help to the best of my ability” (personal responsibility). After doing this for all four versions, they also reported their motivation to help in each version.

When gradually increasing the identifiability of the described beneficiary, emotional reactions increased at a steeper rate than perceived impact or personal responsibility (see left column of ), and only sympathy (an emotional reaction) mediated the identifiability effect when comparing helping motivation towards statistical vs. vividly described identified beneficiaries. When gradually increasing the proportion of beneficiaries possible to save, perceived impact increased at a steeper rate than emotional reactions or personal responsibility, and only perceived impact mediated the proportion effect when comparing helping motivation towards the lowest and highest rescue-proportion versions. When gradually increasing the ingroupness of beneficiaries, personal responsibility to help increased at a steeper rate than emotional reactions or perceived impact, and only responsibility mediated the kin-based ingroup effect when comparing helping motivation towards relative outgroup vs. ingroup beneficiaries. Study 4 in the same article revealed similar results in a between-group paradigm where each participant responded to only one version for each effect (see right column of ). When controlling for shared variance, only emotional reactions uniquely mediated the identifiability effect, whereas only perceived impact uniquely mediated the proportion effect. Although all three mechanisms uniquely mediated the nation-based ingroup effect, personal responsibility was a significantly stronger mediator.

Figure 3. Participants’ emotional reactions (distress and sympathy), perceived impact and personal responsibility when varying identifiability, rescue proportion and ingroupness. Left column illustrates results from studies 1–3. Right column illustrates results from study 4 in Erlandsson et al. (Citation2015). Reprinted from Erlandsson et al. (Citation2015). Emotional reactions, perceived impact and perceived responsibility mediate the identifiable victim effect, proportion dominance effect and in-group effect respectively. Organizational behavior and human Decision Processes, 127, 1–14, with permission from Elsevier.

Another set of studies investigated participants’ justifications after choosing which of two help projects to implement (Erlandsson et al., Citation2017). Only emotional reaction reasons were used more to justify choices in line with (rather than contrary to) the identifiability effect; only impact reasons were used more to justify choices in line with (rather than contrary to) the proportion effect; and only responsibility reasons were used more to justify choices in line with (rather than contrary to) the ingroup effect.

Taken together, these studies illustrate that three different beneficiary effects seem driven by three different psychological mechanisms. We help identified beneficiaries more than statistical because of more intense emotional reactions, we help beneficiaries part of a small group more than beneficiaries part of a large group because of a greater perceived impact, and we help ingroup-beneficiaries more than outgroup-beneficiaries because of a stronger sense of personal responsibility.

Beneficiary attributes differ in how evaluable, justifiable, and prominent they are

Based on the summarised results from our studies testing multiple beneficiary effects in identical experimental paradigms (Erlandsson, Citation2021; Erlandsson et al., Citation2020), we believe that we tentatively can say something meaningful about the relative evaluability (Hsee & Zhang, Citation2010), justifiability (Li & Hsee, Citation2019), and prominence (Tversky et al., Citation1988) of some of the beneficiary attributes. Below, we explain these three dimensions and summarise the perceived patterns (see also ).

Evaluability

A beneficiary attribute with high evaluability is easy to understand and interpret also when it is presented in isolation (as in separate evaluation) whereas an attribute with low evaluability is difficult to interpret unless one has a point of direct comparison (as in joint evaluation).

Several weak beneficiary effects (age, innocence, and especially the temporal effect) emerged in joint evaluation but not in separate evaluation, implying that these beneficiary attributes are low on evaluability. Other weak beneficiary effects (kin-based ingroup, identifiability, and especially the proportion effect) emerged in both separate and joint evaluation (and were similar in size), implying that these beneficiary attributes are more inherently evaluable.

Justifiability

A beneficiary attribute with high justifiability is perceived as something that should influence helping decisions, and this can be driven by both personal norms and by social norms (how easy it is to justify unequal valuation of different lives to oneself and to observers respectively; Capraro & Perc, Citation2021). We argue that the number of individuals possible to help is a highly justifiable attribute. Everything else equal, most people will prefer to help more rather than fewer beneficiaries (Garinther et al., Citation2022), and it would be very difficult to justify preferring an otherwise identical project helping fewer individuals. The relative justifiability of a specific beneficiary attribute (e.g., age) versus the efficacy-attribute (e.g., number of beneficiaries) will determine people’s preferences in situations where both attributes differ (e.g., 4 children vs. 6 adults).

Large majorities of participants matched so that 100 women and 100 men, as well as 100 compatriots and 100 foreigners were equally valued, suggesting that discriminating patients based on their gender, or their nationality, is difficult to justify (left panel of ). The age and innocence attributes were slightly more justifiable with mixed matchings, whereas temporal proximity was the most justifiable beneficiary attribute with over 72% matching so that existing patients were valued higher than future patients.

Likewise, several strong beneficiary effects absent in separate evaluation became clearly reversed in joint evaluation. Specifically, this was the case for innocence, ingroup, gender, and especially the identifiability effect; right panel of ). This suggests that the number of patients possible to save (an efficiency attribute) is more justifiable than each of these beneficiary attributes. The only strong effect that emerged was the temporal effect, meaning that temporal proximity (existing vs. future beneficiaries) is more justifiable than the number of beneficiaries (more vs. fewer).

Prominence

Finally, a beneficiary attribute is prominent when it influences preferences more in choices than in evaluations. One way to test the relative prominence of different attributes is to first ask people to perform a matching task to make two options equally attractive, and at a later point ask them to choose one of these (equally attractive) options (Slovic, Citation1975). Another way is to have people express preferences with or without the option of expressing indifference.

Many beneficiary attributes were prominent in that they influenced choices more than evaluations. In Erlandsson et al. (Citation2020) this was demonstrated by a significant majority of participants choosing to implement the projects helping existing (vs. future), child (vs. adult), female (vs. male), innocent (vs. partially responsible), and compatriot (vs. foreign) beneficiaries, even when these projects had earlier been matched as equally attractive by themselves, and when this implied helping fewer patients.

Prominence was also illustrated in Erlandsson (Citation2021), where going from joint evaluation (where it is possible to express indifference) to forced choice (where it is impossible) made most effects stronger. To illustrate, the probability of a participant preferring the project helping children increased from 61.6% to 88.7% for the weak age effect (6 children vs. 6 adults), and from 38.1% to 60.3% for the strong age effect (4 children vs. 6 adults). Likewise, the probability of a participant preferring the project helping kin increased from 66.4% to 85.7% for the weak kin-ingroup effect (6 kin vs. 6 non-kin), and from 37.5% to 70.2% for the strong kin-ingroup effect (4 kin vs. 6 kin).

Still, not all beneficiary attributes are equally prominent. The identifiability effect does not change much when going from joint evaluation to forced choice, and the strong proportion effect even decreases when doing so (60.7% to 46.5% in Study 1, and 56.5% to 39.0% in Study 2). In sum, temporal proximity, age, gender, innocence and ingroup are more prominent attributes than number of beneficiaries, whereas the number of beneficiaries is more prominent than proportion rescued.

Discussion

This review article makes three key contributions: (1) It highlights the centrality of the beneficiary when determining the outcome of a helping situation; (2) It articulates and empirically demonstrates similarities and differences of various beneficiary attributes; (3) It uses insights from diverse academic disciplines to inform beneficiary effects in charitable giving.

As proposed by Charitable Triad Theory, charitable giving is determined not only by the characteristics of the benefactors, but also by characteristics of fundraisers and beneficiaries (Chapman et al., Citation2022). Despite this, most of the research on charitable giving to date has focused on the benefactors (donors), meaning that a better understanding of the effects of beneficiary (and fundraiser) characteristics on giving is needed (Chapman et al., Citation2022). This review article puts the beneficiary front and centre and demonstrates what has previously been proposed by Charitable Triad Theory: (a) that the identities and characteristics of beneficiaries are instrumental in determining charitable decisions; and (b) that it is crucial to consider both the relation between beneficiaries and donors (such as when testing the ingroup effect), and the interaction between beneficiaries and fundraisers (such as when fundraisers decide how to portray beneficiaries in charitable advertising).

One overarching take-home message is that different beneficiary attributes increase (or decrease) helping through different pathways. This is illustrated both by research systematically testing beneficiary effects in different response modes (discussed next), and by research testing underlying mechanisms of different beneficiary effects (discussed later).

Forced choices reveal “hidden” beneficiary effects

One striking finding is that several beneficiary effects primarily emerge when people are forced to choose, but less so when expressing their preferences in other ways. We connect these findings to the prominence effect which predicts that when two available options differ on two attributes, the relatively more prominent attribute will influence choices more than it will influence valuations (Slovic, Citation1975; Tversky et al., Citation1988). An important contribution of the present research is that we identify some beneficiary attributes that are more prominent than the number of beneficiaries (presence, age, innocence, and ingroup) whereas others are less prominent (proportion).

Two clear demonstrations of how choices may reveal “hidden” moral preferences are the weak forms of the gender and nation-based ingroup effects that are totally absent when expressed in a matching or in a joint evaluation mode, but clearly present when tested with forced choices. This can be interpreted as many people preferring to express valuations of lives that are as easy to defend as possible. Given contemporary public rhetoric in democratic countries, arguably the most justifiable and “politically correct” approach is to value men and women and people from different countries equally (a kind of equality heuristic, perhaps). When a choice is forced however, people do not choose randomly but rather fall back on the gender and ingroup effects because preferring women and ingroup beneficiaries is more justifiable than preferring men and outgroup beneficiaries. This suggests that people are aware of how they come across to others, and that they choose the most justifiable option that is available to them.

Other studies have shown that when people are asked to choose between two similar donation targets, they are more likely to opt out of giving altogether than if they are only asked to donate to a single target, because the choice creates a conflict between being prosocial and being fair (Ein‐Gar et al., Citation2021; see also Carroll et al., Citation2011; Gordon-Hecker et al., Citation2017). Accordingly, Sharps and Schroeder (Citation2019) demonstrate a general preference to distribute resources across multiple individuals in need rather than concentrating resources on a single individual, and that this effect is driven by procedural fairness, and Andreoni and Bernheim (Citation2009) argue that this tendency is stronger in public situations as people first and foremost want to be perceived as fair. One proposed explanation for this is that most people do not have clear moral preferences regarding the relative moral value of efficiency or equity (or of different beneficiaries), but are instead motivated to “do the right thing” or “what is approved by others”, which implies that they will choose the alternative that is framed as the more socially desirable one in a given situation (Capraro & Rand, Citation2018; Tappin & Capraro, Citation2018).

Taken together, these findings provide strong support for the notion that helping decisions are often constructed in the moment when people are confronted by the need of others. Rather than making these decisions based on pre-set preferences, they depend on the way beneficiaries are presented and how the helping decision can be expressed. This is reminiscent of research on preference construction (e.g., Lichtenstein & Slovic, Citation2006; Slovic, Citation1995) which showcases the importance of understanding the underlying processes of judgements and decisions. Moreover, these findings illustrate that it is possible to influence or “nudge” peoples’ moral preferences by changing the way they can express them (Thaler & Sunstein, Citation2009).

Future directions for research on underlying mechanisms of beneficiary effects

We believe that our work showing how different beneficiary effects are primarily driven by different psychological mechanisms is important and encourage researchers to include and compare multiple mediators when trying to determine the underlying psychological mechanisms of helping (see Fiedler et al., Citation2018; Pieters, Citation2017 for discussions about meaningful mediation analysis). At the same time, we acknowledge the inherent limitations of asking people about their prosocial motives in both qualitative (e.g., self-generated justifications) or quantitative research (e.g., self-reported emotional reactions).

At times, experimental approaches could elucidate which motives that drive helping towards different beneficiaries. Experimentally manipulating the motives for helping would be especially promising for investigating to what extent different egoistic motives for helping explain different beneficiary effects. For example, anticipated material costs and benefits (Gneezy et al., Citation2011; Lacetera et al., Citation2014; Rubaltelli et al., Citation2020) could be manipulated by varying the asking amount (e.g., $10 or $100), or by offering (or not offering) a compensation to those who help different beneficiaries. Anticipated social costs and benefits (Everett et al., Citation2018; Raihani & Power, Citation2021; Silver & Silverman, Citation2022) could be manipulated by letting people make their helping decisions or allocations either in private or in public, or by manipulating the injunctive norm among observers (i.e., which type of beneficiaries that others believe should be valued, e.g., Andersson et al., Citation2020). Finally, anticipated psychological costs and benefits due to helping or not helping (Anik et al., Citation2011; Erlandsson et al., Citation2016) could be manipulated, for instance, by varying how potential helpers think they will feel after their decision (Gaertner & Dovidio, Citation1977; Schroeder et al., Citation1988), by varying exposure to the beneficiary after the decision has been made (Batson et al., Citation1991; Toi & Batson, Citation1982), or by varying the descriptive social norms (how do other people behave; Andersson et al., Citation2022; Batson et al., Citation1988).

Another opportunity for future research would be to examine how helper attributes moderate different beneficiary effects. This is an inherent part of analysing the ingroup effect, but a perceived shared identity can influence other beneficiary effects as well. For instance, the gender effect is likely stronger among female than among male helpers, and the age effect is likely stronger among helpers who have their own children. Moreover, the identifiability effect might be more applied more by people who are more emotional or intuitive, whereas the proportion effect may be more pronounced among analytical and deliberative people (Friedrich & Dood, Citation2009; Friedrich & McGuire, Citation2010; Kleber et al., Citation2013; Mata, Citation2016). The misery and innocence effects may also be stronger among some people than others; one study testing mediated moderation found that helpers with a strong moral identity (those who believe morality is important) help more when they hear about innocent beneficiaries (and this effect was mediated by sympathy), but less when they hear about partially liable beneficiaries (and this effect was mediated by personal responsibility; Lee et al., Citation2014).

Are beneficiary effects immoral?

We argue that beneficiary effects imply that different individuals’ lives and wellbeing are valued unequally, noting that willingness to help is only one of many ways people may express valuation. We do not, however, claim that unequal valuations of lives are necessarily irrational or the result of biased thinking, as this ultimately depends on the moral values and beliefs applied to the situation. Although there are stronger moral arguments for some beneficiary effects (e.g., the age effect) than for others (e.g., the identifiability effect), it is difficult – and beyond the scope of this article – to distinguish moral (normative) from immoral (non-normative) beneficiary effects (but see Baron & Szymanska, Citation2011; Caviola et al., Citation2021; Dickert et al., Citation2012).

The perceived morality of different beneficiary effects is interesting in its own right. A possible path for future research would be to focus on impression formation (also known as person perception) and empirically test which types of prosocial decisions are perceived more favourably. We already know that people typically perceive a helper donating a small sum but experiencing the “right” emotions as more moral than an equally affluent helper donating a large sum but with mixed motives (Erlandsson, Wingren & Andersson, Citation2020; Newman & Cain, Citation2014), but an area worth further investigation is whether the perceived morality of helping differs as a function of the beneficiary. For instance, in relation to the gender effect, one could test how people evaluate hypothetical individuals who express preferences in favour of helping male or female patients in a medical dilemma, whilst varying both the number of beneficiaries in the contrasting projects (3 males vs. 3 females, or 6 males vs. 3 females), the gender of the individual expressing the preference (man or woman), and the response mode the preference is expressed in (joint evaluation or forced choice). Similar studies can of course be done on other beneficiary effects (see e.g., Fowler et al., Citation2021; Hughes, Citation2017), and these studies have potential to contribute to our understanding of why it is perceived as sometimes acceptable and sometimes unacceptable to express that different beneficiaries are valued unequally.

Beneficiary effects in various literatures

As previously noted, beneficiary effects are understudied within the charitable giving literature (Chapman et al., Citation2022). Still, we believe that some insights about charitable giving can be obtained by looking at research on other forms of prosocial decision-making such as modern moral social psychology and judgement and decision making (e.g., Awad et al., Citation2018; Uhlmann et al., Citation2015), dictator games (e.g., Brañas-Garza, Citation2007; Capraro & Perc, Citation2021), and health economics (e.g., Edlin et al., Citation2012; Tsuchiya et al., Citation2003), where beneficiary identities have traditionally had a more central role. Consequently, our review contains research from multiple diverse fields, where the common denominator is the focus on beneficiary attributes.

We believe that beneficiary effects and unequal valuations of lives occur when people respond to medical and non-medical moral dilemmas, when they play dictator games in the lab, and when they decide which charity organisations to donate to. That said, we also suspect that people understand these decisions quite differently. Whereas medical life and death decisions are likely perceived as inherently moral and dependent on objective rules and prescriptions, charitable giving is typically perceived as supererogatory and therefore optional, and preferences regarding charitable giving are perceived more in terms of subjective taste (Berman et al., Citation2018). Expressed differently, we expect that people will moralise and have more dogmatic opinions about right and wrong regarding beneficiary effects in medical decision making, than regarding the same beneficiary effects in charitable giving. People who donate to charity in a way that expresses that they value different beneficiaries unequally might be perceived as relatively moral as this behaviour is intuitively compared to not making any charitable donation, whereas a person who expresses unequal valuation of lives in a medical context could be perceived as relatively immoral as this behaviour is intuitively compared against a medical decision which values lives equally (Zlatev & Miller, Citation2016).

The “effective altruism” movement strongly advocates that charitable giving should be based more on efficacy concerns and less on the feelings and personal experiences of the helper (see Caviola et al., Citation2020; MacAskill, Citation2015; Singer, Citation2009). According to an effective altruist, a person who decides which cause or organisation to donate to is making a moral decision akin to deciding which patient will receive treatment and who will not. Effective altruists evaluate charitable causes against stringent, utilitarian priorities. They argue that any giving that does not maximise quality-adjusted life years saved is, by definition, ineffective and (implied to be) immoral. Although the number of beneficiaries is central for an effective altruist, this should not always be understood in terms of equal valuation of lives. For instance, saving the life of a skilled surgeon rather than six homeless can be justified as the surgeon is likely to save additional lives in the future (Caviola et al., Citation2021), and saving fewer 18-year-olds rather than more 90-year-olds can be justified as the expected number of healthy life years is greater.

Concluding remarks

We have highlighted and provided evidence for eight beneficiary effects: the tendency for people to prefer helping beneficiaries that are existing now (vs. in the future), younger (vs. older), female (vs male), miserable (vs. thriving), innocent (vs. immoral or responsible), ingroup (vs outgroup), identified (vs. non-identified), and part of small (vs. large) group. These effects will manifest themselves differently for different people and under different conditions. We demonstrate that these effects vary in terms of their evaluability, justifiability, and prominence, and put forward a research agenda for future research to isolate the likely mechanisms (i.e., mediators) that underpin the eight beneficiary effects, and additional factors that could influence the relative strength of the effects (i.e., moderators). Inspired by Charitable Triad Theory (Chapman et al., Citation2022), we also encourage research that considers the dynamics between the benefactors (those in a position to help), fundraisers (those requesting help) and beneficiaries (those needing help).

Many beneficiary effects highlight potentially problematic assumptions, stereotypes, and biases in the way people make helping decisions. To change behaviour, one must first understand it. By articulating these effects explicitly, we hope that non-profit fundraisers will find ways to navigate these tendencies in ways that allow them to garner the most support possible under the specific conditions relevant to their cause. Our ideas for future research will hopefully encourage social psychologists as well as researchers from other fields to further understand the social dynamics (and indeed biases) inherent in helping decisions with a view to positive change.

Positionality and constraints on generality statements

When this manuscript was drafted, the first author (AE) was 41 years old and identified as a privileged white cisgender man, but more strongly as a “quantitative” psychology researcher with a preference for randomised controlled experiments. The group of authors is diverse in terms of gender identity, nationality, ethnicity, background and held worldviews, but united by a shared interest in human prosociality.

There are constraints on generality in all psychological research, and these constraints are arguably even stronger in controlled experiments with homogenous convenience samples as these studies tend to sacrifice external validity to maximise internal validity. We are the first to acknowledge that the size and direction of the eight beneficiary effects will likely differ across cultures, groups, and contexts, as well as over time, and we welcome future research to examine these boundary conditions empirically.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Non-human animals or the environment can be beneficiaries, but this paper focuses on human beneficiaries.

2 Charitable Triad Theory further argues that one must consider how benefactors, beneficiaries, and fundraisers interact to inform helping responses. Whereas some beneficiary effects presented in this review focus exclusively to beneficiary attributes (e.g., age and gender), others – such as the ingroup effect – might be better understood as the relation between the beneficiary and the benefactor. In addition, several of the beneficiary effects included in this review can be constructed or activated by the fundraiser, for instance by presenting or portraying beneficiaries in different ways (e.g., misery, identifiability, and proportion) or by making specific social identities salient (e.g., ingroup; Charnysh et al., Citation2015; Kessler & Milkman, Citation2018).

3 Beneficiary effects represent a sub-category of the broader concept of helping effects which we have used previously (Erlandsson, Citation2014, Citation2021). Helping effects occur when a situational factor influences subsequent helping behaviour. As the beneficiary is part of the situational package, all beneficiary effects are helping effects. However, not all helping effects are beneficiary effects. Examples of helping effects that cannot easily be considered beneficiary effects include the observer effect which posits that people usually help more in public situations than in private situations (Andersson et al., Citation2020; Bradley et al., Citation2018; Haley & Fessler, Citation2005), the bystander effect highlighting that the presence of other potential helpers influences one’s own helping behaviour (Cryder & Loewenstein, Citation2012; Darley & Latane, Citation1968; Fischer et al., Citation2011), the social norm effect, which suggests that information about others’ behaviour influences one’s own helping (Chapman et al., Citation2023; d’Adda et al., Citation2017; Farrow et al., Citation2017; Lindersson et al., Citation2019; Van Teunenbroek et al., Citation2020), and the goal-gradient effect which shows that people are more likely to help when learning that e.g., 85% (vs. 15%) of the necessary money has already been collected (Cryder et al., Citation2013; Koo & Fishbach, Citation2008). All these are helping effects (i.e., situational factors that influence helping behaviour), but not beneficiary effects because the situational factor is unrelated to the beneficiary.

4 There are obviously different degrees of strong beneficiary effects, and preferring 4 existing patients over 6 future patients does not imply that one will also necessarily prefer 4 existing over 100 future patients. In all studies reported in Erlandsson (Citation2021), the less efficient project could help two fewer patients than the more efficient project (see ).

Table 4. Mean attractiveness-rating of the helping projects in separate and joint evaluation, and number of participants preferring each project in joint evaluation and forced choice in Erlandsson (Citation2021).

5 People can form social identities also based on their gender or age, but we omit these here in order to not confound the beneficiary effects.

References