ABSTRACT

In this paper, we develop a new, integrative, approach to theorising and research in the field of mediated communication (MC): the Social Dynamics Approach (SoDA). It builds on current developments in the literature that outline MC as a dynamic process where behaviour unfolds in continuous interaction between medium and user. The SoDA extends this view by acknowledging the collaborative and collective nature of interaction, thereby placing special focus on the social dynamics involved. The SoDA integrates the MC literature with theories and empirical findings from related fields, such as philosophy and social psychology. Applying the SoDA can aid MC researchers in developing a more nuanced and deeper understanding of social dynamics within different media and thereby of differences between communication media. We show how the SoDA can lead to methodological and theoretical advancements, and how it can help resolve existing contradictions related to media richness, online disinhibition, and online polarisation.

Abundant research and thinking in the domain of computer-mediated communication (CMC) examines how properties of technology determine the force and form of social impact. For example, online misunderstandings and conflict have been attributed to a lack of cues leading receivers to interpret online messages more negatively than the sender intended (the “negativity effect”, Byron, Citation2008; Sillars & Zorn, Citation2021), to anonymity making online users feel that they can be aggressive and hostile without consequences (“toxic disinhibition”, Stuart & Scott, Citation2021; Suler, Citation2004), or to users’ opportunity to self-select sources and contacts that confirm their worldviews and strengthen prior convictions in so-called “echo chambers” (e.g., Cinelli et al., Citation2021). More recent CMC literature acknowledges, however, that the user is not passively affected by the medium but actively decides how to use it and thereby influences the effects it has. That is, the behavioural and cognitive outcomes of mediated interaction depend on how the user’s needs and goals interact with the possibilities the medium offers. For example, interaction partners can be very sensitive to social norms online (Huang & Li, Citation2016; Postmes et al., Citation1998) and they can use online technologies to build very intimate social relationships (Antheunis et al., Citation2020; Walther & Whitty, Citation2021).

In the current paper, we propose to take this a step further. We argue that the widely adopted approach to studying mediated communication, with its focus on individual thoughts and behaviours, is insufficient in an era of pervasive, contextually nuanced, and socially embedded digital communications. It is necessary to also consider the collective nature of and the social dynamics within interactions that are mediated by technology. To address this, we present the Social Dynamics Approach (SoDA) to mediated communication. In short, we propose that, within an interaction context, the technological possibilities (and constraints) of the medium, personal goals, and social norms are jointly constructed by interaction partners through a dynamic process in which they make sense of the situated social structure: their shared ideas about their relationship and collective goals within the interaction. The SoDA can be considered an integration of social structuration or constructivist approaches into the CMC literature. Acknowledging that the boundaries of acceptable behaviour are constantly (re)negotiated within social interactions can help explain the wide variety of sometimes unexpected (and unintended) social practices that can emerge online (see DeSanctis & Poole, Citation1994; Giddens, Citation1984, for a broader perspective). The SoDA emphasises, in line with the broader CMC literature, that the form social interactions take is further bounded by technology. As we will illustrate below, the SoDA enables us to better understand the processes and outcomes of mediated communication, and helps us explain some apparently contradictory findings across literatures.

The structure of this paper reflects its five aims. First, we present a short outline of the historical development of the CMC literature and a reflection on the current state of the field. Second, we build on and extend this literature by incorporating theoretical and empirical insights from related fields (e.g., philosophy, social psychology), and describe the SoDA’s theoretical approach which aims to give direction to future thinking about and conceptualising mediated communication. Third, we aim to give guidance on how to translate this theoretical approach to empirical realities through presenting the SoDA’s methodological approach. Fourth, we will describe a recent line of research as a concrete example of how the SoDA can be put into practice, which, importantly, generated novel insights about three prominent research areas in the mediated communication literature: media richness, online disinhibition, and online polarisation. The fifth and final contribution of this paper is an outline of possible applications and implications of the SoDA for the mediated communication literature. We will highlight a couple of promising research directions where the SoDA might help resolve contradictory findings.

The effect of the medium

Ever since people started to use computers for communicating in the early 1980s, scholars have been interested in the way the medium changes the behaviour and cognitions of its users. In early empirical CMC research, the communication medium and its properties (e.g., anonymity) were the independent variables: a stimulus that generates a response. This was then compared to other media or properties, and in this comparison, face-to-face (FtF) interactions and their characteristics were typically seen as a baseline. In this way, CMC research emerged from an often implicit set of standards and expectations about what is “normal” in FtF interactions. For example, based on the observation that people tend to use more rude and threatening language (response) when they communicate via online media (stimulus) than when they communicate FtF, researchers concluded that online media use, by increasing anonymity, reduces people’s social concerns and disinhibits their behaviour (Kiesler et al., Citation1984; Suler, Citation2004). We can call this a mechanistic approach where the user’s behaviour is enabled and constrained by the medium, and where a stimulus (the medium and its properties) leads to a response (individual cognitions and behaviours).

Coinciding with computer-mediated communication becoming more common place and widespread, the user in CMC research changed from being viewed as a passive reactor to an active user. This is most clearly visible in the shifting focus to affordances. Affordances are the possibilities that a particular environment offers for behaviour (Gibson, Citation1979), and can in this case be seen as the link between the mediating technology and the outcome. Many recent empirical CMC studies study the (cor)relations of certain (sets of) affordances with user’s behaviours and/or cognitions. For example, comparing the degree of social presence in media differing in synchronicity (Tang & Hew, Citation2020), contrasting the degree of politeness in media channels differing on identifiability and networked information access (Halpern & Gibbs, Citation2013), comparing platforms that differ on visibility and persistence on the degree of jealousy they engender (Utz et al., Citation2015), or assessing perceived effectiveness of social support and relational closeness across platforms differing in the availability of “likes” or “upvotes” (Hayes et al., Citation2016).

Moreover, as is widely recognised, whether and how these affordances actually affect a user’s behaviour crucially depends on the user’s goals (e.g., Rice et al., Citation2017). For example, the anonymity afforded by an online chat environment might be “used” to flame or troll by a user that wants to insult someone without consequences (e.g., Alonzo & Aiken, Citation2004), or to present the self in a very socially desirable way by a user that aims to woo someone (Walther, Citation1996). Affordances, defined as possibilities for behaviour, would thus only materialise in the interaction between the user’s goals and the medium: affordances are used strategically (Evans et al., Citation2016). This changes the focus of theorising from “people reacting” to the context of the medium to “people acting” inside an environment equipped with affordances and the user’s personal and interpersonal goals. In line with this trend, Carr (Citation2020) proposed to rename the field to mediated communication (MC), thus removing the term “computer”. We will observe this recommendation in the remainder of this manuscript. These developments suggest a different way of looking at mediated communication: rather than examining the impact of a stimulus environment on behaviour and cognition, we need to examine the process by which behaviour and cognition unfolds in the interaction between user and environment. So, besides technological constraints, there are personal constraints to behaviour and cognition.

One step further: structuration and construction

We argue that it would be worthwhile to take this a step further by acknowledging that the process of interpersonal interaction is inherently social and collaborative. Although (almost) all the outcome behaviours and cognitions that recent MC studies focus on are interpersonal, that is, in reference to one or more other person(s) – e.g., expressing one’s opinion to someone, sharing knowledge with someone, feeling jealousy towards someone, perceiving social support from someone – they all involve the assumption that the users are interacting as relatively independent entities. But from the broader communication literature we know that social interactions are essentially co-operative acts of two or more individuals (e.g., Bavelas et al., Citation2000; Clark, Citation1996). In line with the scientific traditions on the philosophy of mind and language (e.g., Searle, Citation1990, Citation1995) and sociological theory of knowledge (e.g., Giddens, Citation1984), we therefore propose to look at mediated communication as joint action (DeSanctis & Poole, Citation1994; Fulk, Citation1993).

In order to collaborate (and interact) effectively, interaction partners form cognitions about the actions that they are performing together. Searle (Citation2010) calls this “collective intentionality”. Collective intentionality refers to the capacity of different minds to be jointly directed at some object or situation and can take the form of, amongst others, shared intentions, joint attention, shared beliefs, shared knowledge, and collective emotions. While collective intentionality is held by individuals, it is not a simple aggregation of individual intentionalities. Instead, it is irreducibly collective: an intentional state of the group rather than its members as separate entities (Searle, Citation1990, Citation1995). For example, if I plan to have a Team’s call this afternoon and I know you plan to have a Team’s call this afternoon, I could say that “we have a Team’s call this afternoon”, but here our intentions are still individual. Our intentions become truly collective when we plan to have a Team’s call together. Of course, this still means that I plan to have a Team’s call and you plan to have a Team’s call, but the crucial element here is that we plan to do this collectively, which we cannot accomplish as individuals. Collective intentionality enables interaction partners to successfully coordinate their actions and achieve their collective goals.

To understand how interaction partners shape this collective understanding of where they are going and what they are doing, it is informative to look at the literature on social structuration and construction. Social structure is a rather abstract term, originating from sociology, that broadly refers to the regularities of interactions within a given social entity (Calhoun, Citation2002). According to Structuration Theory (Giddens, Citation1984), social structure steers interaction but is also emergent from interaction as it needs to be negotiated and established by interaction partners together (the “duality of structure”). First, social structure steers interaction by providing the norms that prescribe how the participants in the interaction ought to behave. Second, social structure is emergent from interaction as its content depends on interaction partners’ behaviours: when people act in line with the structure’s norms, the structure is reinforced, but when they act outside of the structure’s norms, their behaviour can be corrected, or the structure can be modified (see also Koudenburg et al., Citation2017, Citation2021). This process whereby people jointly establish norms has been referred to as social construction. So, any interaction behaviour simultaneously reflects and defines the group norm, and interaction partners collectively shape and reshape the social structure in which they act.

At the start of the Digital Revolution, DeSanctis and Poole (Citation1994) introduced Adaptive Structuration Theory (AST) to recognise that technology also “structures” human action. That is, technology brings with it a new set of constraints and possibilities for behaviour, which can affect social norms. But, in line with the duality of structure, DeSanctis and Poole specified that people can still use technology in different ways and thereby affect the structure that technology provides. This means that the use of technology can be an invention of the users themselves, that is, socially constructed. In short, technology use will affect the social structure, but the social structure can also affect technology use.

The structuration and construction theories are highly abstract and remain somewhat opaque about the exact process of structuration within real-life interactions. Research in the tradition of the Social Identity model of Deindividuation Effects (or SIDE model) has given more insight into this by empirically showing how, in the context of online interactions, participants infer social norms from interaction in the process of conforming to the prevalent communication style and content (Postmes et al., Citation2000). The different chatgroups in the study by Postmes and colleagues developed group-specific interaction norms over the course of their interactions, for example, in their use of slang or the average length of a message. Groups even differed in the extent to which they were socioemotionally supportive or relatively impersonal and cold. In this way, in a specific social interaction setting (implicit) behavioural norms or conventions are induced from the interaction as it unfolds, and these norms constrain how technology is subsequently used. Thus, in contrast with many MC approaches, the social construction and structuration perspectives do not consider interaction behaviour an outcome on an individual level but part of an infinite cyclical process with collective consequences. We can pit this relatively organic and non-deterministic approach against the more mechanistic approach described earlier. Where the mechanistic approach states that the medium determines behaviour, the organic approach argues that mediated interaction is so context-specific that we cannot reliably predict it.Footnote1 The SoDA integrates these two perspectives.

Departing from a mechanistic approach where technology steers individual cognition and behaviour, the current MC literature examines how technology interacts with the user’s needs and goals to produce behaviours and cognitions. Based on social structuration and construction theories, we suggest to add social norms to this system since these also, in interaction with technology and personal goals, influence the user’s cognitions and behaviours. Moreover, we propose to complement this with a consideration of the collective nature of interaction: interaction behaviour occurs within a certain social structure and reflects back on that structure. In this way, technology, in interaction with personal goals and social norms, shapes the construction of collectives. This comes down to considering the interaction partners (with their goals) and their (technological and normative) interaction environment a social dynamical system of interdependent elements, where change to one of these elements changes the entire system. We call this integrated perspective the Social Dynamics Approach (SoDA) to mediated communication, which we will explain in more detail below.

The SoDA: theoretical approach

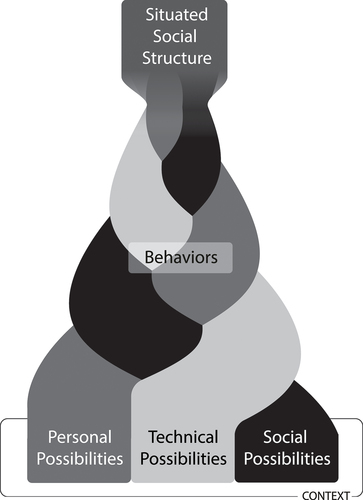

The SoDA consists of a theoretical and a methodological approach. We will first describe the theoretical approach (see below for a schematic representation) and outline the methodological approach in the next section.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the Social Dynamics Approach (SoDA) to mediated communication.

To provide a short and concrete overview of the SoDA, we start with a summary of the processes included in the theoretical approach. We will explain these processes in more detail in the subsequent paragraphs. In short, the SoDA posits that the way participants behave, and thereby the form that their interaction takes, functions as a constant gauge of their understandings of who they are and what they are doing collectively – the social structure as situated in the interaction (the tip of the braid in ). Before their interaction starts, the situated social structure is based on participants’ previous experiences and the associated expectations, in a top-down fashion. During the conversation, participants’ understanding of the situated social structure is constantly being updated by new experiences, in a bottom-up fashion. When their behaviour is in line with these understandings, the conversation runs smoothly which will lead participants to reconfirm their beliefs about the situated social structure. But when behaviour is not in line with their understandings, the conversation is disrupted and participants conclude that there is a misunderstanding between them in terms of the situated social structure, stimulating them to reconsider and potentially change these understandings. In other words, participants use the smoothness of their interaction as evidence to update their beliefs about the social structure. The SoDA proposes that interaction behaviour is shaped by social (norms), personal (goals), and technological (medium) possibilities and constraints – the three strands of the braid in . The dynamic interplay between these three factors takes place within and is influenced by a certain social and medium context (the bottom square in ). The SoDA also contains an important feedback loop (see also the duality of structure): the situated social structure is not only affected by, but also affects the social, personal, and technological possibilities that participants perceive. We will now explain these processes in more detail and explain how they are embedded in the broader literature.

Collaboratively building situated social structure

To have an effective interaction, participants need to collaborate and therefore coordinate their actions – interaction is joint action (Bavelas et al., Citation2000; Clark, Citation1996; Sebanz et al., Citation2006). In psycholinguistics, there is substantial theoretical and empirical work on how interaction partners either unconsciously align (Pickering & Garrod, Citation2004) or consciously coordinate (Clark & Brennan, Citation1991) their understanding of the meaning of their communication. Interaction partners need to have similar representations to understand what the other is talking about (e.g., a shared understanding of the meaning of a certain technical term). But also more generally, interaction partners need to establish common understandings of the content and the process of their interaction. They need to align on what they are doing in the interaction: their personal and collective goals (see also collective intentionality), and how they will do this: their mutual behavioural expectations or social norms (see also social constructivism). This process of collaboratively shaping and updating shared understanding and shared viewpoints has been referred to as building common ground (Kashima et al., Citation2007).

Building common ground is not merely a process that facilitates the interaction. By collaboratively establishing what they do and how they act, interaction partners also come to form a sense of who they are as a collective. Together, we call this the situated social structure: participants’ sense of who they are and what they are doing collectively within a social interaction – their collective identity and goals. Acting in line with the mutual expectations about how they should behave to accomplish their collective goals and perpetuate their social relations, the co-acting interaction partners experience their interaction as well-coordinated and effortless and conclude from this that they share a social structure. This does not only rely on what is being said (i.e., interaction content) but also, sometimes even more so, on how things are being said: the form of interaction, and especially the subjective experience thereof (Koudenburg et al., Citation2014, Citation2017). To use a metaphor: the body of interaction is experiencedFootnote2 by those individuals as the embodiment of the relationship that they have with each other (Kashima et al., Citation2007; Koudenburg et al., Citation2017).

There is quite a large literature that has empirically demonstrated how this works. One strand of research has studied how people form a sense of social structure inductively, bottom-up, simply by having an interaction and forming a sense of shared understanding (e.g., Koudenburg et al., Citation2017; Postmes et al., Citation2005; Swaab et al., Citation2007). For example, when some unacquainted participants in an online discussion discover that they agree about government funding for education, they can infer a sense of we-ness from this. But this process also works the other way around; deductively or top-down: by shaping the goals and expectations of interaction partners, the pre-existing social structure affects the form of the conversation and thereby partners’ sense of shared understanding (Postmes et al., Citation2005; Swaab et al., Citation2007). For example, one may expect that sexist talk is ok among young men, and make a sexist statement in one’s male friends group. When such a statement is rejected, one learns that this behaviour is, in fact, not in line with the norms of this situated social structure, and the non-sexist norms are strengthened. When the behaviour is not rejected, however, sexism might become more normative in the group (Koudenburg et al., Citation2021). Thus, the social norms in society influence the goals and norms that participants bring to an interaction and thereby affect their communication behaviour. These goals and norms then become situated in the interaction. But partners’ behaviour, and the extent to which this is in line with these situated structures, can also change them. In this way, the situated social structure is emergent in the social dynamics of the interaction.

Disrupting the situated social structure

When interaction, even slightly, diverges from the way it is supposed to go, such as an unexpectedly long silence or people speaking simultaneously, interaction partners notice this immediately (see also expectancy violations theory, Burgoon, Citation1993; Burgoon & Hale, Citation1988). Since the form of their interaction is so strongly tied to interaction partners’ situated social structure, a disturbance in this collaboration is experienced as a social threat (Koudenburg et al., Citation2017). Such disruptions raise questions about their shared identity and goals as a collective. But note that what counts as a disruption depends crucially on interaction partners’ expectations that are based on the existing social structure. For example, where unacquainted interaction partners take a silence or other delay to their conversation as a signal of misunderstanding and maybe even conflict, partners in a secure relationship might take these same signals as a sign of mutual understanding and validation (Koudenburg et al., Citation2014). As another example, when a subordinate interrupts a higher status other, this might threaten their established social hierarchy, but when it is the other way around, this will confirm their situated social structure (Koudenburg et al., Citation2013). It is worth noting that the effect sizes in this empirical literature are considerable: this suggests that people are very sensitive to these social signals and even very miniscule deviations from social expectations can lead to quite drastic re-assessments of the situated social structure (see, for example, Koudenburg et al., Citation2013; Koudenburg et al., Citation2021).

The role of technology

People’s ability to behave in line with mutual expectations and thereby maintain the expected form of conversation depends not only on their correct understanding (perceived norms) and motivation (personal goals) to do so, but is also restrained and enabled by the technological features of the (online) context in which the interaction takes place. Besides goals and norms, the form of social interaction is importantly shaped by the technological constraints and possibilities that partners perceive (which can also be partly socially constructed as partners might point out or demonstrate behavioural opportunities to each other). This could be termed “affordances” but we opt for a more concrete description (e.g., Dings, Citation2021; Oliver, Citation2005). We propose that conversation goals, perceived social norms, and perceived technological possibilities together determine what range of behavioural options people perceive they have within the conversation, which sets the boundaries for the kinds of behaviour they are likely and willing to perform. That is, there is an interplay between personal (goals), social (norms), and technological (medium) constraints and possibilities for behaviour in each interaction context. This implies that the three factors are not independent nor static but influence each other continuously within a conversation: when one of the factors changes, the other factors can change too. For example, when one would start to use Reddit, a platform for discussing issues, for dating and others would follow suit, this could drastically change what behaviour is perceived possible and expected. Here personal goals influence the technological possibilities one perceives as well as the norms one associates with the platform. There are abundant real-life examples of this process of usage shaping technology, such as the early online messaging service Minitel which developers expected to be used for person-to-business communication but which became popular and successful because users discovered loopholes that allowed them to send erotically tinted messages (“messageries roses”) for which there was an unexpectedly high demand (Feenberg, Citation1992).

Problems arise when interaction partners’ goals and behavioural expectations are incompatible with the technological possibilities. Even when participants have a correct (that is, shared) understanding of the situated social structure and are motivated to act in line with it, they might not be able to due to technological constraints. This can have social consequences as people get the misguided impression that their interaction partners do not have the same goals and/or do not subscribe to the same social norms. For example, a person who is telling their friend about their holidays over the phone would expect to receive backchannel signals from this friend at certain intervals, like “wow”, “ooh nice!, “hmmm”, as evidence of the friend’s continued attention. But when a delay on the line prevents the friend from meeting this expectation, this results in a disrupted conversation. Research shows that this will lead interaction partners to the conclusion there is a problem between them: there must be a misunderstanding and their social relationship is threatened. This threat is experienced even when the external cause – a technological problem – is evident (Koudenburg et al., Citation2013). So, interaction behaviours are influenced by the technological context but tend to be internally attributed, which has relational consequences.

In sum, social interaction is a collaborative act in which structures such as norms, conventions and identities are formed, shaped and maintained. More concretely: interaction partners establish and re-establish shared ideas about who they are and what they are doing (their situated social structure) based on how their interaction behaviour fits their expectations based on these ideas. We argue that technological constraints impose solid restrictions on behaviour and thereby can and do shape the social dynamics in interaction. What relational outcomes this ends up having is a product of how the interaction unfolds, which also depends on interaction partners’ personal goals and the perceived and practiced social norms. This perspective means that making between-medium comparisons (e.g., face-to-face vs. online chat) can be very informative, as long as we compare, across different technological contexts, the dynamical emergence of social structures.

The SoDA: methodological approach

The theoretical approach outlined above implies a certain way of conducting research – a methodological approach. The SoDA proposes to study mediated communication by closely examining actual conversational behaviour and its collective causes and consequences within the dynamical system of an interaction. In line with the current MC literature, we put behaviour centre stage: how do people (strategically) act within the behavioural possibilities and constraints a certain interaction context provides? We additionally propose that a better understanding of why these behaviours lead to certain outcomes is reached by analysing the social context (i.e., situated social structure) in which it occurs. Technological possibilities shape social dynamics by shaping how interaction partners act to realise goals and conform to social norms. The ensuing social dynamics reshape the situated social structure and therefore have collective outcomes.

Many current MC studies focus on isolating (sets of) technological possibilities, to test their consequences for the interacting individual in experiments or observational studies. We believe, however, that we need to understand how these technological possibilities are put to work in a specific situated social structure, made up of people that hold certain assumptions about their identities and goals, both as individuals and collectively. We need to study mediated communication in situ because behaviour and its meaning emerges in the ecology of the social setting. Indeed, the same technological possibilities might lead to differing, even contradictory, behaviours depending on the situated social structure. Interaction partners can strategically use technological possibilities in different ways, enabling different forms of behaviour, depending on their goals and the social expectations they associate with a particular interaction context. For example, being able to express oneself anonymously, creates particular opportunities for the expression of positive (e.g., prosocial, Shifrin & Giguère, Citation2018) as well as negative (e.g., hostile and aggressive, Rösner & Krämer, Citation2016) emotions, depending on intentions or goals and the local social norm that prevails (see also Klein et al., Citation2007; Postmes et al., Citation1998). Also, interaction partners’ interpretation of each other’s behaviour might radically differ depending on the interaction context in which it is perceived. Media environments have social norms, which may echo the social functions they fulfil. Whereas you may end your email to a colleague with “Best wishes, [your name]”, writing this at the end of a WhatsApp message may be perceived as overly formal, and saying the same thing when you are meeting this colleague in person would be outright weird. Relational inferences of communication behaviours are thus partly medium and social context dependent.

The SoDA methodological approach invites us to compare how the same people with the same situated social structure interact via different media (or contexts with differing technological possibilities), or, the other way around, to compare how people with differing situated social structures interact within the same medium. This makes the close study of interaction partners’ social behaviours and collective perceptions within media central, in such a way that cross-media comparisons can be made: how do interaction partners respond to the restrictions and possibilities of technology in their interactions and how is this behaviour interpreted, attributed, and reacted to in the context of a certain situated social structure?

Operationalization

Concretely, the SoDA’s methodological approach proposes to measure social dynamics 1) by tracking behaviour within individual interactions, and 2) by assessing experiences and perceptions at a collective level (such as social conflict or love). This has two implications for the ways in which MC research is conducted.

First, the analysis of big data with complex and technologically advanced methods has become increasingly popular in MC research. Big data often comprises countable metrics, such as the number of likes or replies or automated analysis of content (often based on word counts) as measures of interaction behaviour (see, for example, a recent review of Reddit studies: Proferes et al., Citation2021). These data are readily available and easy to analyse, and, as there are so many datapoints, they can reliably expose large-scale patterns that cannot be identified otherwise. The risk is, however, that they provide a somewhat simplified image of what happens in social interaction. Even though the limitations of automated content analysis are widely recognised and many researchers stress the importance of always validating these with manual coding (e.g., Van Atteveldt et al., Citation2021), in reality, it appears that this micro-level check-up is often forgotten (see also Song et al., Citation2020). Big data analysis might be especially ill-suited for studying social dynamics within an interaction. For example, one might perform an automated analysis on the quality of relations on an online forum by counting the frequency of words classified as uncivil behaviour, such as instances of aggressive or hostile language, swearing, derogatory names, etc. But, whereas this shows how negatively valenced the posts are, it does not tell us whether this negativity was aimed at other participants in the discussion or towards a common enemy, who might not be present in the conversation (e.g., the government). To be able to distinguish conflict from consensualisation, a more in-depth and contextualised analysis of interaction behaviours is needed, in which relations between posts take centre stage. We therefore suggest to use mixed-method approaches and to complement big data with in-depth manual content or discourse analyses of interaction behaviours. A particularly suitable approach for this is the Computer-mediated Communication Discourse Analysis (CMCDA; Herring, Citation2004). CMCDA can be used to assess various forms of textual online behaviour, such as the use of emoji in online humour (Sampietro, Citation2021), psychosocial support requesting and giving in online communities (Zayts-Spence et al., Citation2023), or the construction of group solidarity through language style (Kleinke et al., Citation2018). Like, CMCDA, we emphasise the need to interpret these language-based phenomena in a broader medium and situational context (Herring, Citation2004), and recommend to analyse these manifest behaviours in tandem with self-report measures of more covert social processes.

This brings us to the second methodological implication: there is a need for tools that can assess conversational experiences and collective perceptions (experiences of “us”) within a single interaction. Currently there are only a few such scales available, which is not surprising considering that the process of interaction and its social dynamics are rarely studied. Most scales used in the MC literature, and communication literature more broadly, measure general perceptions of and feelings towards either the self (e.g., self-esteem, Rosenberg, Citation1965; generalised communication apprehension; McCroskey, Citation1982), partner(s) (e.g., individualised trust, Wheeless & Grotz, Citation1977; partner responsiveness; Reis et al., Citation2018), or relationship(s) (e.g., attraction, Montoya & Insko, Citation2008; relationship satisfaction; Hendrick, Citation1988). These scales are not specific to one interaction episode and do not allow a combined assessment of the self and the other and the relationship. Two recent exceptions that do assess people’s appreciation of the social interaction with others are Roos and colleagues’ (Roos et al., Citation2023) Feeling Heard scale that measures the experience of being heard within an interaction, an important component of which is the experience of mutual understanding, and Koudenburg and colleagues’ (Koudenburg et al., Citation2013) measure of shared cognition which essentially assesses whether partners experienced a sense of common ground during their interaction.

Beyond these quantitative measures of conversational experiences at a collective level, there is a need for qualitative assessments because people’s behavioural intentions and interpretations can differ greatly between different media contexts, in ways we cannot predict. This might take the form of post-conversation interviews or open-ended survey questions in which interaction partners are asked about their experiences of their joint action and their relationship. Moreover, since we are looking at social dynamics, it would also be very valuable to measure conversational experiences during interactions. There are tools for this that enable the coding of “the stream” of experiences in real-time (e.g., the mouse paradigm, Vallacher et al., Citation1994; see Jans et al., Citation2019 for an application in the context of a collective experience: sense of belonging).

The SoDA applied: new insight into online discussions

We believe that the Social Dynamics Approach to mediated communication outlined above can provide important new insights into existing MC research and theorising. In this section, we will illustrate this with a recent line of research that applied the SoDA and that offers a new perspective on three prominent MC literatures: 1) media richness, 2) online disinhibition, and 3) online polarisation. We will first summarise this research line and then outline how the resulting insights complement the three MC research areas.

Online social regulation

In a recent line of research, Roos and colleagues attempted to uncover processes behind the apparent greater propensity of text-based online discussions to misunderstanding and polarisation compared to FtF discussions (e.g., Anderson et al., Citation2018; Coe et al., Citation2014). The authors set out to find explanations for this between-medium difference by looking at social dynamics within media. Small groups of unacquainted participants were asked to discuss controversial political topics via text-based online chats and face-to-face (Roos, Koudenburg, et al., Citation2020; Roos, Postmes, et al., Citation2020). In line with Social Information Processing theory (Walther, Citation1992), the authors assumed that most people seek to prevent conflict and maintain harmonious social relationships, also in online discussions (see also Papacharissi, Citation2004, who shows online uncivility is rare). It follows that, in the interactions Roos and colleagues studied, the situated social structure consists of a group of strangers who likely expect to have a civil and constructive discussion about a controversial topic, aiming for consensus and/or common understanding. Participants’ (inter)personal goals in this context are likely sharing their opinion and maybe even convincing others of that opinion. These personal goals are also influenced by the situated social structure, however, such that participants need to balance the wish to share their opinion with the aim of maintaining harmony. In order to protect this situated social structure while accomplishing their personal goals, participants will have to show diplomatic behaviours: diplomacy is the social norm.

The pragmatics literature shows that two behaviours with an important diplomatic function are ambiguity and responsiveness. First, people in difficult FtF discussions tend to pre-empt conflict by ambiguating their message rather than expressing their disagreement clearly (Bavelas et al., Citation1990; Pomerantz, Citation1984). People can ambiguate with disclaimers (e.g., “I do not know for sure”), hedges (e.g., “maybe,” “sort of”), and vocalisations that express doubt (e.g., a drawn out “hmmm”) or tentativeness (e.g., “uhm,” Brennan & Clark, Citation1996). Many of these expressions result from people probing what is acceptable to say while speaking. People do so by continuously gauging their partners’ (mostly non-verbal) expressions of (dis)approval and editing their message accordingly. This tentativeness communicates tact and concern for the feelings of (potentially disagreeing) others (Roos, Koudenburg, et al., Citation2020; Roos, Postmes, et al., Citation2020). Second, people in FtF interactions are responsive. That is, they continuously provide each other with feedback by sending backchannel signals during their interlocutor’s speaking turn, such as humming, saying “yes” or nodding one’s head, or by initiating a relevant next turn (Beňuš et al., Citation2011; Clark & Brennan, Citation1991). This shows interpersonal attention and interest, and is taken as signal of understanding and friendliness (Davis & Perkowitz, Citation1979; Koudenburg et al., Citation2013; Koudenburg et al., Citation2017). In sum, probably unknowingly, by putting effort in phrasing a statement that will receive their partners’ approval or at least will not offend them (ambiguity) and by making reference to their partners’ contributions to the conversation (responsiveness), participants jointly reinforce the situated social structure in which they have a constructive discussion.

Roos and colleagues (Roos, Koudenburg, et al., Citation2020; Roos, Postmes, et al., Citation2020) found, however, that, while participants still appeared to subscribe to this same situated social structure online, the technological constraints of the text-based medium limited their ability to act accordingly. First, presumably due to the text-based character of the online chats, participants wrote very clear statements with little ambiguity, for example, when presented with a statement against affirmative action for females in top-positions: “I don’t agree with it” rather than “So, then I do not really agree with it. But I do a little bit actually, because, say, it is also true that women always, well, women have children and, ehm, yes” as some did FtF (quotes taken from Roos, Koudenburg, et al., Citation2020). It even appeared that, to compensate for the lack of visibility and synchronicity in the chats, participants preferred to think through and carefully formulate their messages before sending any of it to, and potentially offending, their interaction partner(s) (Roos et al., Citation2022). Secondly, due to the relative lack of visibility and synchronicity, participants could not send backchannel signals during each other’s speaking turns and often “talked” at the same time. This resulted in an “interaction” that looked more like a list of self-contained statements than a responsive dialogue (Dennis et al., Citation2008; Roos, Utz, et al., Citation2023).

The resulting lack of diplomatic behaviours – ambiguity and responsiveness – online thus appeared to be caused by technological constraints, but people did not appear to acknowledge this. Roos and colleagues (Roos, Koudenburg, et al., Citation2020) found that participants felt ignored and thought that their partners became disinhibited (i.e., unrestrained by social concerns) online. Participants also experienced more disagreement and misunderstanding, and felt less solidarity towards their interaction partners than in their FtF discussions (Roos, Koudenburg, et al., Citation2020; Roos, Postmes, et al., Citation2020).

In sum, in the context of a controversial discussion where the goal is to maintain good relations while expressing one’s opinion, and the norm and therefore the implicit expectation is to behave diplomatically (by expressing oneself ambiguously and being responsive), the technological constraints of text-based media can limit people’s ability to do so. But, rather than acknowledging that their partners’ non-normative behaviour is due to the medium, people conclude that these partners do not endorse the situated social structure of constructive discussion and as such are not motivated to preserve social harmony and reach consensus.

Interaction technology and norms

This does not mean that social norms are static and overrule technology. In a series of studies, Roos and colleagues (Roos et al., Citation2021, Citation2022) found that participants resisted interventions that aimed to make their online messages more responsive and more ambiguous, and that observers experienced ambiguity in the online chats as weird and even indicative of conflict. Together, these results suggest that, over time and with repeated interaction experiences, technological constraints and possibilities might affect the behavioural norms associated with that specific medium. This is a telling example of the mutual influence of the technological and social factors in the SoDA: technology use shapes norms and these norms subsequently shape the possibilities participants perceive the technology to offer, even when these possibilities suddenly change. For instance, the increase in character length on X (previously Twitter) did not immediately lead to an increased nuance in posts. The social norms resulting from these technological constraints and possibilities are not equally functional in maintaining social relationships, however. Although participants perceive a lack of diplomatic behaviour online as normative, it is still interpreted negatively, in the sense that it reduces their experience of harmonious social relations. It seems as if people adjust their behavioural expectations to the medium, but attribute the source of these new norms to the underlying situated social structure rather than the technological constraints.

Three areas of insight

By applying the SoDA, this line of research gained important insights that shed new light on existing findings and explained contradictory results in the MC literature. We discuss the novel insights in relation to three influential literatures: 1) media richness, 2) online disinhibition, and 3) online polarisation.

Media richness

By zooming in on the dynamics of social interactions, Roos and colleagues’ research contradicted one of the key tenets of Media Richness Theory (MRT; Daft & Lengel, Citation1986). While MRT was developed in the organisational or work context, it has also been applied to other contexts, such as relational communication (Tong & Walther, Citation2015) and education (Shepherd & Martz, Citation2006). MRT distinguishes communication media based on their ability to transmit communication cues and thereby information from sender to receiver. The central tenet of MRT is that richer media can forward more cues and thus more information than leaner media. For example, the phone is considered a leaner medium than FtF communication because the former cannot transmit non-verbal signals while the latter can. MRT further holds that a primary driver for selecting a medium of a certain richness is the degree of equivocality of the message. A highly equivocal message is unclear and more difficult to understand correctly. Equivocality can thus be considered a synonym of Roos and colleagues’ ambiguity. To prevent misunderstanding by the receiver, a highly equivocal or ambiguous message needs to be sent through a rich medium: in a rich context, communicators can reduce the unclarity by increasing the number of cues and thus the amount of information contained in the message (e.g., winking while making a sarcastic statement). So, according to MRT, ambiguous or unclear messages are undesirable because they can lead to misunderstanding between sender and responder, and richer media enhance a message’s clarity by transferring more cues (Runions et al., Citation2013).

The SoDA would add the nuance that the communicative function of equivocality or ambiguity depends on the specific situated social structure in which it occurs and the associated behavioural norms. Ambiguity fits one situated social structure (e.g., one in which controversial issues are discussed) better than the other, and it can be interpreted differently and thus have different social consequences depending on the situated social structure. Applying the SoDA, Roos and colleagues (Roos, Koudenburg, et al., Citation2020; Roos, Postmes, et al., Citation2020) found that unclear messages can be desirable because they signal people’s endorsement of a situated social structure of harmonious and constructive discussion. The authors further found that the text-based online medium, which is leaner than FtF, stimulates users to write clear and succinct messages because less cues can be transferred. In fact, the richer medium offers communicators the opportunity to reduce their message’s clarity and they appear to use this opportunity liberally. This sounds incompatible with MRT, but these contradictions can be resolved by considering the situated social structure and the associated collective goal of conversation, and how this relates to the common distinction between the content message, i.e., the actual content about the topic, and the relational message, i.e., the perception of the sender towards the receiver (Adler et al., Citation2006; Trenholm & Jensen, Citation2008).

A clearly formulated message is probably very desirable in a situated social structure where the collective intention is accurate information transmission, such as when planning a meeting with colleagues (at the time MRT was developed, 1986, this resembled the typical setting in which online communication took place). However, in the situated social structure Roos and colleagues studied, where people aimed for a constructive discussion of a controversial topic, a clear message can come across as insensitivity to other people’s opinions. So, there is an inverse relationship between the degree of clarity of appearance vs. intentions here: by ambiguating a message content-wise, one clarifies, and prevents misunderstandings about, the message’s underlying social intentions. Online is very clear in content and this leads to unclarity on the relational level: social intentions are misunderstood.

This exemplifies how the SoDA differs from and complements the MRT literature. Where MRT focusses on how a communication technology, in interaction with a user’s goals, affects the transfer of a message from person A to person B, the SoDA adds that this message is also affected by social norms and is interpreted against the backdrop of a certain situated social structure.

Online disinhibition

A second influential assumption is that the online medium disinhibits people (Suler, Citation2004). It is proposed that in many online communication environments, due to the affordance of anonymity, people lose the social constraints that normally guide their behaviour. As a result, people dare to say anything they want, not limited by their concerns about the consequences for impression management and social relationships. This can have both benign or prosocial and toxic or antisocial consequences, depending on the context. In a romantic context, disinhibition can take the form of increased self-disclosure that helps build relationships (e.g., Joinson, Citation2001). In the context of controversy, disinhibition can take the form of unbridled aggression that breaks relationships, like calling names or using rude language (e.g., Lapidot-Lefler & Barak, Citation2012). While evidence for the online disinhibition effect is inconsistent (Clark-Gordon et al., Citation2019; Lea et al., Citation1992), the idea that being online disinhibits remains widespread in the MC literature (e.g., Casale et al., Citation2015; Cheung et al., Citation2021; Voggeser et al., Citation2018).

The SoDA adds that behaviour can appear disinhibited, and even have consequences for social relationships, without resulting from a state of disinhibition. Rather, interaction partners’ perceptions of each other’s disinhibition can be based on their interpretation of (technology-steered) interaction behaviours in light of a certain situated social structure.

In line with this, Roos and colleagues closely examined interaction behaviour and the way this is socially interpreted. Notably, they did not find evidence for actual disinhibited behaviour in the online discussions they studied: zero instances of aggressive or hostile language, swearing, derogatory names, etc (Roos, Koudenburg, et al., Citation2020). If anything, participants seemed to carefully construct their message before sending it (Roos et al., Citation2022). Due to their clear and unresponsive form, however, messages appeared more extreme to receivers, and senders appeared less concerned with how their message might be received by others. Perceived disinhibition, in turn, was positively related to perceived disagreement and conflict (Roos, Koudenburg, et al., Citation2020). The disinhibited interaction partner did not seem to be invested in maintaining the situated social structure of constructive and harmonious discussion. Interestingly, it was found that, while they perceived their partners as more disinhibited, participants did not consider themselves more (or less) disinhibited online than FtF (Roos, Koudenburg, et al., Citation2020). So, visual anonymity does not necessarily make people feel less accountable for their actions (psychological change), increasing their self-disclosure or rude language use,Footnote3 but the technological constraints of a medium directly affect the way they can and do communicate (behavioural change), which has social psychological consequences when this changed behaviour is perceived as evidence of disinhibition by others. The SoDA thus suggests a shift away from considering disinhibition an individual psychological state that causes individual behaviour to treating it as a form of interpersonal misunderstanding that is emergent from the social dynamics within interaction.

Online polarisation

There is considerable concern about increasing polarisation in Western societies. According to many scholars and pundits, this trend is caused by social media and its algorithms. Consequently, much empirical and theoretical research on online polarisation has been dedicated to explaining and reducing this. Theoretically, scholars commonly distinguish between ideological polarisation, i.e., increasing disagreement about issues or values (e.g., DiMaggio et al., Citation1996), and affective polarisation, i.e., increasing dislike and distrust between groups (Iyengar et al., Citation2012). Recently, Yarchi and colleagues (Yarchi et al., Citation2021) aptly summarised the wide range of empirical approaches by distinguishing three key aspects of ideological and affective polarisation: homophilic interaction patterns, aggravating opinion differences, or pronounced intergroup hostility. For current purposes, the most relevant theoretical aspect is affective polarisation, which could be translated to the conflict experienced by different parties, and should be empirically observable from hostile interaction behaviours. Research tends to measure online polarisation indirectly based on self-reported users’ perceptions, or, increasingly, on “hard” metrics from social media data (e.g., Iandoli et al., Citation2021), such as retweeting, hashtag use, following behaviour (e.g., Garimella & Weber, Citation2017), network analysis (e.g., Kaiser & Puschmann, Citation2017), etc. Studies often focus on what medium characteristics positively correlate with online polarisation, for example, selective exposure, that is, a lack of exposure to cross-cutting opinions (e.g., Mutz, Citation2006, but see; Bail et al., Citation2018), exposure to uncivil online discussion (e.g., Hwang et al., Citation2014) or dissemination of fake news and misinformation (e.g., Törnberg & Bauch, Citation2018). The literature tends to look at how technology affects individuals’ polarised (i.e., extreme) behaviours and cognitions, sometimes depending on their goals: what does the technology expose the individual to, what does the individual do with the technology (who or what do they interact with), and/or how do they feel as a consequence of using the technology?

Taking a situated approach, the SoDA goes beyond individuals’ interactions with technology, or individuals’ behaviour within technological contexts, to include the social dynamics with the interaction partner. Importantly, the SoDA sees the experience of polarisation as contingent on interaction partners’ interpretation of each other’s (technology-steered) behaviour in light of their situated social structure. Regardless of the actual degree of disagreement with their partner, people’s experience of polarisation will depend on how they see their partner behave and how this behaviour can be interpreted considering their situated social structure.

Essentially, Roos and colleagues found that the text-based medium limits people’s ability to act in line with constructive discussion norms and that interaction partners, and outside observers alike, perceive this as polarisation (Roos et al., Citation2021; Roos, Koudenburg, et al., Citation2020; Roos, Postmes, et al., Citation2020). Regardless of the actual difference of opinion between interaction partners, people conclude they must be polarised because the form of their interaction – unresponsive and unambiguous – does not match that of a constructive discussion. In fact, online forum discussions (like those on Reddit) can appear to be polarised simply because there is no dialogue and people are broadcasting their opinion (see also Roos, Utz, et al., Citation2023).

Whereas an excessive focus on (clearly) venting one’s own opinion at the expense of listening to others is often considered a symptom of polarisation, this same phenomenon can thus be the cause of polarisation online when it induces misperceptions of polarisation, which might, in the long run, cause real polarisation (Davis & Dunaway, Citation2016). Rather than being deliberate and maleficent, polarising behaviour might be unintentional or even result from benevolent intentions (when people try to formulate their statements very precisely to prevent misunderstandings, see Roos et al., Citation2022). Thus, rather than looking at how online media might invite purposeful uncivil and polarising behaviour or how online media might induce polarised views or negative impressions of others, the SoDA proposes to look at how online media directly affect interaction behaviours and how these behaviours affect participants’ inferences about their situated social structure.

Implications and future directions

In this paper, we introduced a new way of thinking about and studying mediated communication (MC) phenomena that takes social dynamics into account: the Social Dynamics Approach (SoDA) to mediated communication. In short, besides the constraints and possibilities for behaviour the mediating technology offers and their interplay with the user’s goals and needs, we recommend MC researchers to also consider the social dynamics of the interaction itself which are importantly affected by, and affect, interaction partners’ sense of collective identity and goals – their situated social structure. What this all boils down to is that when people communicate, they always communicate information about their relationship. This is not new and in fact widely recognised in communication science (see also the common distinction between the content and relational component of a message; Adler et al., Citation2006; Trenholm & Jensen, Citation2008), but we add that the mediating technology, by limiting and enabling communication behaviours, affects what people communicate about their relationship. This proposed adjustment, seemingly subtle and simple, implies a significant change in conceptualising about and operationalising MC phenomena.

We illustrated how this new theoretical and methodological approach can be applied to a particular kind of interaction context: that of controversial discussions amongst strangers in text-based chats. But we believe the SoDA can be applied to any situation in which people are involved in an interaction. For example, it would be interesting to apply the approach to romantic relationship formation. How do people act romantically via different media? Maybe some media are inherently unsuited for romantic advances. Or maybe people adapt and behaviours that are considered neutral in one medium come to have a romantic or sexual connotation in another. Another example of an interesting application context would be a work setting where status differences are prominent in many situated social structures and behavioural expectations differ depending on the individual’s relative standing (i.e., dominant vs. subservient behaviours). Again, some media might be better suited to perpetuate this social structure than others. Or people might adapt their behaviour to technological constraints and use different status markers in different media.

We think that by taking into account the entire set of interconnected parameters specified in the SoDA, the MC literature can develop a more nuanced and deeper understanding of within-medium interaction behaviours and their consequences for between-medium differences. This may help resolve some well-known contradictions in the literature. For example, there are contradictory findings about the consequences of the exposure to dissenting or cross-cutting views. Some researchers purport that exposure to dissent can reduce group polarisation by making people more aware of the counter arguments to their own opinion (e.g., Price et al., Citation2002; Strandberg et al., Citation2019). But, on the other hand, others hold that cross-cutting exposure can be met with defensiveness and thereby exacerbate polarisation (e.g., Bail et al., Citation2018; Settle, Citation2018). We propose that such outcomes may both occur and that which of the two prevails ultimately depends on the social dynamics of the interaction and how this exchange is interpreted in light of the situated social structure. Depending on the setting and dynamics, an essentially similar exchange can either be experienced as an argument between (political) opponents, as a constructive discussion between like-minded group members or as venting of a set of individuals (see also Koudenburg & Kashima, Citation2021). In fact, recent research shows that making people with opposing opinions aware of non-political similarities between them (such as common interests and demographics) – in effect changing their situated social structure from one of opposing partisans to similar peers – makes them feel closer to each other, which increases their open-mindedness and decreases their opinion polarisation (Balietti et al., Citation2021). Therefore, understanding the social dynamics better can be key to explaining these seemingly contradictory effects.

As another example, the effect of anonymity on self-disclosure, as a benign disinhibition effect, is inconclusive (Clark-Gordon et al., Citation2019; Nguyen et al., Citation2012). Some studies find that people self-disclose more online than face-to-face (Joinson, Citation2001; Lapidot-Lefler & Barak, Citation2015), but others show that they do not (Hollenbaugh & Everett, Citation2013; Schiffrin et al., Citation2010). This contradiction could potentially be explained by taking into account the interplay between technological, personal and social possibilities in the SoDA, and their relation with the situated social structure. For example, on Tinder, the general assumption of many users appears to be that it is a platform for people looking for casual sex (e.g., Bulman, Citation2016). If this is indeed seen as a common goal by users, then it is unlikely that they expect or provide much self-disclosure because they do not expect or intend to build a relationship. It then becomes counter-normative to be intimate and involved. The technological possibilities of Tinder might reinforce this by encouraging users to create profiles without in-depth personal details that lend themselves to being evaluated based on a quick scan of outward features (i.e., swiping photographs). eHarmony, another online dating platform, has similar characteristics and could potentially be used in a similar way, with users not disclosing much about themselves. Users of eHarmony behave quite differently, however, because this platform attracts people looking for a serious relationship (see https://www.eharmony.co.uk/about/). Users will therefore mutually expect and perform self-disclosures as this is needed to find the perfect match: the interactions engaged in by users thereby perpetuate the situated social structure. Here, again, goals and norms shape the use of the platform. In sum, the differing degrees of self-disclosure found in online platforms can be better understood by considering the interplay between personal, social, and technological factors.

Lastly, besides applying the SoDA to these and other domains of interpersonal interaction, we think future work could expand the SoDA to also consider interaction observers and non-human actors. Whereas we left observers or so-called “lurkers” (those who only read online content) out of the description of the SoDA for simplicity, research shows that they do make inferences about the situated social structure based on interaction behaviours and these inferences are similar to those of interaction partners (Roos et al., Citation2021). Lurkers are also an important group, because they comprise 90% of many online communities and their (offline) attitudes can be strongly affected by their reading of online discussions (Preece et al., Citation2004; Sung & Lee, Citation2015). On a related note, the SoDA is developed based on research with WEIRD – Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic – samples, so we still have to establish the generalisability of the SoDA to other samples. A further future expansion of the SoDA is related to the rapidly evolving field of technologies such as generative AI, extended reality, and the internet of things, calling for an in-depth exploration of the very nature of human communication. The SoDA in its current form does not incorporate human-non-human interactions as we focus on situations where both interaction parties are open to the development of social relationships and can form cognitions about their situated social structure. It might be interesting to see whether and how the SoDA can also accommodate these human-non-human interactions. There is reason to suspect that this might be the case as people can and do attribute human characteristics and intentions to non-human agents (for a review see Rapp et al., Citation2021). For designers of chat-agents it would then be important to know the user’s perceived social structure and make the agent show behaviours that shape that understanding.

Broader theoretical implications

To reflect briefly on the broader theoretical implications of this work, we discerned two historical streams of thinking within the MC literature that the SoDA integrates: 1) a mechanistic and deterministic approach stating that the medium determines behaviour, and 2) an organic and non-deterministic approach arguing that mediated interaction is so context-specific that we cannot reliably predict it. These two approaches could be seen as a specific and situated form of a broader distinction spanning scientific fields. In this broader view, deterministic approaches assume that a complex system can be broken down and analysed in its component parts (e.g., atoms, words, or in the case of our research individual people), and that the behaviour of these components follows certain “rules” by which the behaviour of the system as a whole becomes predictable. They can be pitted against non-deterministic approaches assuming that the interactions within the system are so complex (and/or the number of parameters and processes involved is so large) that the system as a whole becomes chaotic. This implies that regularity or predictability is inherently limited, and entails a focus on variability, fluidity and emergence. There are some parallels between the streams of thinking we have identified and these two more general approaches, but we emphasise that there are also many differences. The theories in the field of mediated communication have developed in idiosyncratic ways to deal with specific issues and questions. This makes it problematic to generalise from the MC theorising to the more general level. Indeed, our development of the SoDA was driven by the limitations we encountered in our research, not by a desire to speak to the more general theoretical issues involved.

Nevertheless, there are parallels between what we have proposed here and writings about the possibility of integrating such broader approaches: some proponents of the complex or dynamic systems perspective have argued that “rules” on the individual level decide the behaviour of the emergent system and that the system, in turn, influences the rules for individual behaviour, which is similar to what we proposed (e.g., Heylighen, Citation2008; see also Solomon et al., Citation2023 for a similar argument concerning the usefulness of dynamic system approaches in studying social interaction). But we want to also caution against too easily extrapolating or drawing general-level conclusions from our work: the domain of mediated interactions is a very specific case which means that any general-level parallels may be incidental and may not generalise to other research domains. We therefore choose to restrict ourselves to this specific field.

Conclusion

We have suggested a new approach to studying mediated communication effects: the Social Dynamics Approach, or the SoDA. The SoDA seeks to explain how the technological features of the communication medium influence the inherently collaborative act of interacting. This allows us to study and better understand interaction partners’ behaviours and experiences within a certain communication environment with inherent possibilities and constraints for their exchange. By closely observing how interactive behaviours unfold within communication environments, and by designing these observations in such a way they are comparable across media, we believe we can further enhance our understanding of why and how behaviours and experiences differ between media. Taking into account both the material constraints imposed by media as well as the social processes by which users seek to achieve their personal and social objectives (sometimes to overcome these constraints or sometimes to use them strategically), we believe, is one way for our field to further grow and develop its understanding of how mediated interactions are transforming society at a rapid pace in ways that will no doubt continue to arouse controversy, but which clearly fascinate us all.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Dr. Emiel Krahmer and Professor Dr. Marjolijn Antheunis for their valuable theoretical and conceptual input on an early version of this paper. We further thank Jannis Kreienkamp for designing - the SoDA figure. No grant was received from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 As we will elaborate upon in the Implications and Future Directions section at the end of this paper, these two approaches show parallels with a more general scientific distinction between deterministic and non-deterministic approaches.

2 Is this always the case? Most certainly not. Humans’ capacity for meta-awareness means that there are other ways of conversing (e.g., as a therapist, diplomat, etc.) in which the pleasant and empathetic form of interaction is totally separate from the higher order cognitions about me, you and us. These people might be seen as manipulators with a double agenda, as they pretend to care about social relations but in reality do not. And of course there might be other reasons why a person in the interaction is not psychologically involved in this dynamic: they might be preoccupied or distracted by more pressing matters, they might be on drugs, and so on. So it is important to clarify that what is written here applies to conversations between people who attend to the topic of the interaction and who are psychologically involved in the interaction: they must be open to the potential formation of relationships.

3 Roos and colleagues (Roos et al., Citation2020) observed no effects of visual anonymity on any of the behaviours or psychological outcomes.

References

- Adler, R. B., Rosenfeld, L. B., & Proctor, R. F. (2006). Interplay: The process of interpersonal communication. Oxford University Press.

- Alonzo, M., & Aiken, M. (2004). Flaming in electronic communication. Decision Support Systems, 36(3), 205–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-9236(02)00190-2

- Anderson, A. A., Yeo, S. K., Brossard, D., Scheufele, D. A., & Xenos, M. A. (2018). Toxic talk: How online incivility can undermine perceptions of media. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 30(1), 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edw022

- Antheunis, M. L., Schouten, A. P., & Walther, J. B. (2020). The hyperpersonal effect in online dating: Effects of text-based CMC vs. videoconferencing before meeting face-to-face. Media Psychology, 23(6), 820–839. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2019.1648217

- Bail, C. A., Argyle, L. P., & Brown, T. W. (2018). Exposure to opposing views on social media can increase political polarization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(37), 9216–9221. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1804840115

- Balietti, S., Getoor, L., Goldstein, D. G., & Watts, D. J. (2021). Reducing opinion polarization: Effects of exposure to similar people with differing political views. PNAS, 118(52), e2112552118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2112552118

- Bavelas, J. B., Black, A., Chovil, N., & Mullet, J. (1990). Equivocal communication. SAGE.

- Bavelas, J. B., Coates, L., & Johnson, T. (2000). Listeners as co-narrators. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(6), 941–52. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.6.941

- Beňuš, Š., Gravano, A., & Hirschberg, J. (2011). Pragmatic aspects of temporal accommodation in turn-taking. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(12), 3001–3027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2011.05.011

- Brennan, S. E., & Clark, H. H. (1996). Conceptual pacts and lexical choice in conversation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 22(6), 1482–1493. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.22.6.1482

- Bulman, M. (2016, January 12). Tinder Makes Users Less Likely to Commit to Relationships, Experts Warn. Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/tech/tinder-makes-users-less-likely-to-commit-to-relationships-experts-warn-a6807731.html

- Burgoon, J. K. (1993). Interpersonal expectations, expectancy violations, and emotional communication. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 12(1–2), 30–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X93121003

- Burgoon, J. K., & Hale, J. L. (1988). Nonverbal expectancy violations: Model elaboration and application to immediacy behaviors. Communication Monographs, 55(1), 58–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637758809376158

- Byron, K. (2008). Carrying too heavy a load? The communication and miscommunication of emotion by email. Academy of Management Review, 33(2), 309–327. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2008.31193163

- Calhoun, C. (2002). Dictionary of the Social Sciences. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acref/9780195123715.001.0001

- Carr, C. T. (2020). CMC is dead, long live CMC! Situating computer-mediated communication scholarship beyond the digital age. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 25(1), 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmz018

- Casale, S., Fiovaranti, G., & Caplan, S. (2015). Online disinhibition: Precursors and outcomes. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, & Applications, 27(4), 170–177. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000136

- Cheung, C., Wong, R. Y. M., & Chan, T. (2021). Online disinhibition: Conceptualization, measurement, and implications for online deviant behavior. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 121(1), 48–64. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-08-2020-0509

- Cinelli, M., De Francisci Morales, G., Galeazzi, A., Quattrociocchi, W., & Starnini, M. (2021). The echo chamber effect on social media. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(9), e2023301118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2023301118

- Clark, H. H. (1996). Using language. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.2277/0521561582

- Clark, H. H., & Brennan, S. E. (1991). Grounding in communication. In L. B. Resnick, J. M. Levine, & S. D. Teasley (Eds.), Perspectives on socially shared cognition (pp. 127–149). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10096-006

- Clark-Gordon, C. V., Bowman, N. D., Goodboy, A. K., & Wright, A. (2019). Anonymity and online self-disclosure: A meta-analysis. Communication Reports, 32(2), 98–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/08934215.2019.1607516

- Coe, K., Kenski, K., & Rains, S. A. (2014). Online and uncivil? Patterns and determinants of incivility in newspaper website comments. Journal of Communication, 64(4), 658–679. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12104

- Daft, R. L., & Lengel, R. H. (1986). Organizational information requirements, media richness and structural design. Management Science, 32(5), 554–571. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.32.5.554