Abstract

Ethics management remains a grey area, especially in how developing countries organise and manage their public finances and administrative activities. This paper draws on a descriptive statistical analysis to explore managers’ perceptions of whether appropriate procedures and sanctions exist against fraud or wrongdoing and whether organisational mechanisms and management of human resources promote ethical conduct in Uganda and Kenya. It explores the central tendencies of Ugandan (N = 122) and Kenyan (N = 104) managers’ perceptions of ethics management in their own organisations. The findings show that despite critical challenges, there is progress towards improving ethics management conditions through the drafting of specific anti-fraud policies and guidelines, the promotion of ethical conduct, and the higher individual propensities to report observed fraud by managers.

Ethics management has been at the core of public administration discourses. Its theory and practice have witnessed evolving organisational methods since ancient times, gaining impetus over the years and becoming a well-developed research and practice area (Cooper, Citation2000; Frederickson & Frederickson, Citation1995; Maesschalck, Citation2004; Lawton et al., Citation2013; Andersson & Ekelund, Citation2022). Because public life and leadership have historically been moralistic, public ethics and integrity remain the stables of public affairs—governmental or otherwise—as long as the related transactional processes affect public welfare. This way, public ethics and integrity set the tone of how public affairs, especially public finance and administrative activities, are organised and supposed to be managed for the sake of public or organisational interest (Lilla, Citation1981; Cooper, Citation2000; Farazmand, Citation2002; Lawton & Macaulay, Citation2015; Miceli et al., Citation2009; Menzel, Citation2019). Most African governments today have instituted more locally informed legislation and structures at all levels to determine, define, guide, monitor and enforce public ethics and integrity in public affairs. Ethics management approaches, such as enforcing compliance, as anchored in a code of ethics (Sakyi & Bawole, Citation2009), regulatory procedures, internal controls, and integrity building (Yeboah‐Assiamah et al., Citation2016), like auditing and staff training about ethical decision-making skills (Manyaka & Sebola, Citation2013), are now widespread in public organisations to address public trust deficits.

It is essential to mention that some ethics management models have become part of performance contracting indicators in these contexts, too, and have been used to define and measure the quality of control systems, including mapping transparency of government enterprises and how they relate to private business organisations in public service delivery (Beeri et al., Citation2013; Chapman, Citation1998; Bowman and West, Citation2021; Menzel, Citation2019). However, realising effective ethical management structures and promoting related norms like whistleblowing remains a grey area in African public management, as elsewhere globally. More specifically, ethics management has been incredibly challenging in African countries whose administrative structures are still developing and are yet to acquire democratic norms, which is a consequence of their own colonial history and state politics of consolidation (Onyango, Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Citation2023a). No wonder ethics and organisational integrity deficits like corruption and low public trust are ever-persistent (Uys, Citation2022; Onyango, Citation2023b).

This notwithstanding, little is known, and much remains perceptive about managers’ insights into this state of affairs in public management. Notably, limited data exist on managers’ own perceptions and evaluations of ethics management in African public management contexts. But not only that. A few studies provide empirical works on the general ethics management attitudes in public and private organisations across African contexts, as this paper seeks to do.

Furthermore, the kind of analysis presented by this article becomes more critical for public sector managers and their private sector stakeholders in their collaborative journeys to create ethical environments for business. It provides more informed insights into the ethics and integrity environments for the African public sector, which has recently rebranded itself as a business-friendly destination for local and international practitioners and investors (Vincent & Evans, Citation2022; Osei & Gbadamosi, Citation2011). In this paper, ethics management is understood in light of Menzel’s (Citation2019, p. 355) definition of it, that is, as “[…] the cumulative actions taken by managers to engender an ethical sensitivity and consciousness that permeates all aspects of getting things done in a public service agency [and other actors involved in public service delivery]. It is, in short, the promotion and maintenance of a strong ethics culture in the public workplace.”

Drawing on descriptive statistical analysis, this paper explores managers’ perceptions and attitudes on their organisational procedures and sanctions against fraud or wrongdoing and whether their organisations and themselves perceive, promote, and demonstrate ethical conduct. It explores different dimensions of ethics management. This specifically interrogates dimensions such as whether appropriate procedures and sanctions exist against fraud or wrongdoing; whether public service or organisational conditions and management of human resources promote ethical conduct; whether management policies, procedures and practices promote ethical conduct; whether managers demonstrate and promote ethical conduct; and whether there are clear guidelines or written policies against fraudulent/dishonest activities. Doing so located the central tendencies of managers towards fraudulent and mismanagement concerns in their organisations. The following sections present the study’s methodology, findings, discussion, and conclusive remarks on areas for further research.

Data and methods

The survey data

The questionnaire used for this study is a revised version of the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board survey questionnaire, which had been previously used in a major study of employee whistleblowing within federal agencies since the 1980s (e.g., USMSPB, Citation1981) and other studies recently to map ethics management in other contexts (e.g., Keenan, Citation2007). Some terminologies were changed to reflect the work environments of public and private sector managers in Uganda and Kenya. The data were collected simultaneously by research assistants in Kenya (N = 104) and Uganda (N = 122) from June to September 2018. This brings the total number of respondents to 226, a considerably adequate sample size for mapping issues under discussion. The two countries were selected based on the researcher’s own networks and familiarity, which are extensive in both countries.

The survey questionnaire measured managers’ opinions and perceptions about ethics management and investigated various organisation practices that determine, define, monitor and enforce norms like whistleblowing, etc. Most respondents were middle and senior managers with an average age of 45 drawn across public agencies and enterprises like public universities, Kenya Ports Authority and other government institutions and private sector organisations like banks, hospitals, research organisations, and the United Nations. The respondents were purposively selected depending on their position in the organisation.

The survey targeted those with managerial roles who have worked in the organisation for at least 5 years. However, considerations were also made in cases where respondents, by the time of data collection, had served in management positions or worked for their organisations or departments for less than 5 years. Snowballing sampling was applied in cases where respondents recommended those within their networks to research assistants. These data were tabulated using the Excel spreadsheet, where the inbuilt Excel spreadsheet data analysis tool was used to analyse findings on each question using graphs, tables, and charts. This study’s uniqueness lies in its cross-cutting investigation of how ethical issues appear in the public and private sectors, which remains rare in management ethics literature, especially in Africa. This cross-cutting analysis is essential in understanding the ethical environment of public governance, given the increased integration of the private sector into public sector realms through contracting out public service delivery. As governments do business with private sectors, it is important to understand the everyday ethical environment concerning fraud/dishonesty and mismanagement issues that have characterised public management activities like procurement processes in countries like Uganda and Kenya (Onyango & Akinyi, Citation2023; Odhiambo & Kamau, Citation2003; Basheka, Citation2021).

Study variables

Using descriptive statistical analysis, the focus looked into the central tendencies of managers towards fraudulent and mismanagement concerns in their organisations. The survey focused on management ethics repertoires, like written policy on reporting fraud/dishonesty and mismanagement, job satisfaction, employee-management relations, training and incentives to blow the whistle or report fraud/dishonest or mismanagement situations. These would provide insights into how organisations in Kenya and Uganda determine, define, guide, monitor and enforce ethical issues. Doing so specifically explored issues like Moral Perceptions, where questions tested the degree of fear of retaliation or reprisal for blowing the whistle. A total of 9 scales were used in this regard. These included scales to measure;

Moral perceptions of major fraud [3 items],

Moral perceptions of minor fraud [3 items],

Moral perceptions harm to others [3 items],

The degree of likelihood of blowing the whistle on major fraud [3 items],

The degree of likelihood of blowing the whistle on minor fraud [4 items],

The degree of likelihood of blowing the whistle on harm to others [3 items],

Organisational propensity for whistleblowing [3 items],

Individual propensity for whistleblowing [6 items], and,

Degree of fear of retaliation for whistleblowing [4 items].

Moral perceptions were further examined using a 9-item scale, which was originally based on responses by managers attending management development programs over several years about various kinds of incidences commonly faced related to fraud and illegal behaviour in previous studies of comparative whistleblowing in Africa and other contexts (e.g., Domfeh & Bawole, Citation2011; Keenan, Citation2007). Perceptions of minor fraud, major fraud, and harm to others are examined using three items. For example, respondents were asked to rate one of the “minor fraud/illegality” items on a 5-point scale ranging from not a fraud/illegality to a very serious fraud/illegality. It is important to note that only relevant data to the scope of this study were retrieved from the extensive data collected on different dimensions of ethics management, like whether employees are fairly recognised and rewarded according to their performance. Or whether managers manipulate and return the organisation’s property after use if they happened to have used them remotely.

Likelihood of blowing the whistle

This scale includes ten items measuring the following three factors: “Likelihood of Reporting Major Fraud,” “Likelihood of Reporting Minor Fraud,” and “Likelihood of Reporting Harm to Others.” Using a Likert-type format, respondents were asked to indicate the degree to which they would be likely to report activities, such as willingness to report fraudulent activities and whether reporting fraudulent activities can be considered in the organisation’s best interest. This part also covered Personal Propensity, where a 5-item scale was used in a Likert-type format. Questions included items asking respondents to indicate that they approved such behaviours as blowing the whistle on illegal and wasteful activities, felt personally obliged to blow the whistle if they observed wrongdoing, and perceived that whistleblowing was in the company’s best interest.

Organisation propensity

This 3-item scale used a similar Likert-type format. Respondents were asked to indicate the degree to which they perceived their organisations as encouraging blowing the whistle on wrongdoing and providing sufficient information on where to blow the whistle. This also explored Retaliation within a 4 items scale. First, respondents indicated the degree of adequacy of protection their company offers to employees reporting illegal or wasteful activities. Two other questions concerned the degree of confidence that one’s supervisor and those above one’s supervisor would not take action against the respondent if they were to report illegal or wasteful activities within organisation operations. A final question asked whether the respondent’s organisation could effectively protect an employee from reprisal.

Results

To test moral perception, questions asked ranged from the organisational policy on ethics and integrity to related attitudes and behaviours in public and private sectors’ organisational contexts. When respondents were asked whether their organisations provided a formal, written policy for suspected fraudulent/dishonest activities that included a description of what they should do if they observed or suspected wrongdoing, the responses slightly varied between Ugandan and Kenyan managers. In Uganda, all respondents, accounting for a 100% response rate, said their organisations provided a formal written policy for suspected fraudulent and dishonest activities. This was against Kenya’s 85.44% who said yes and 14.56% responses who said no.

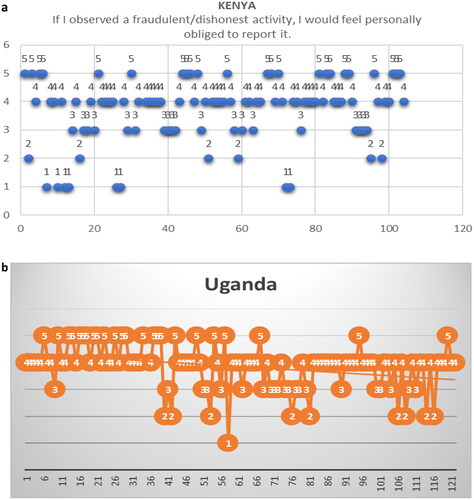

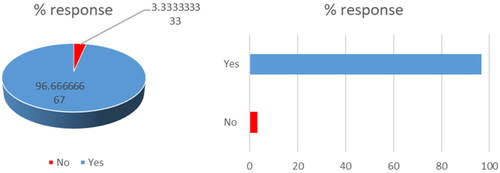

This may show that most organisations in both countries take fraudulent/dishonest activities seriously and may be considering written policies on fraud as a critical compliance tool against organisational waste and mismanagement. The pie chart and bar graphs in below represent 96.67% of the total responses on the need to have a written policy, with 3.33% of the responses indicating no.

Figure 1. Total response rate in Uganda and Kenya on availability of a written policy.

Source: Author.

Further, when asked whether they had attended ethics training, of those who responded to Kenyan managers (43) said yes, against 56 who said no. In Uganda, 35 said yes out of 84 responses to this question. Further probing the length of ethics training for those who attended, most Ugandan managers stated between 2 to 21 days. In contrast, Kenyan managers indicated they attended between 1 and 4 training days, as shown in .

These findings may imply organisational efforts to improve management ethics in Kenya and Uganda. That said, respondents were asked questions testing the effectiveness of these management ethics efforts in their organisations. For example, when asked whether their organisations try to ensure written policy for suspected fraudulent/dishonest activities is communicated to all employees, an overwhelming majority (65.57%) said no in Uganda against 68% in Kenya, and less than half (34.43%) said yes in Uganda against 33% in Kenya.

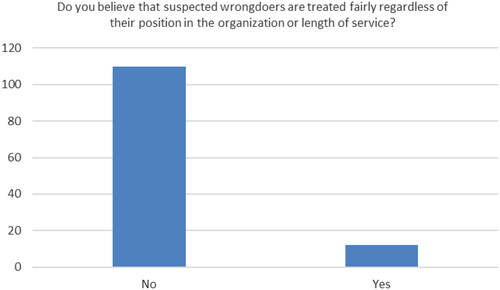

This may mean that whilst both countries’ organisations seem keen on regulating fraudulent/dishonest activities, they need more internal engagement mechanisms with managers to improve the internalisation of written policies on fraud and other mismanagement concerns. In other words, these findings imply that internal organisational environments do not emphasise communicating the written policy to their employees effectively, pointing to the enforcement or implementation gaps within studied Ugandan and Kenyan formal organisations. In addition, when asked whether they thought those suspected of wrongdoing would be treated fairly regardless of their position in the organisation or length of service, most respondents, approximately 80%, said no in Uganda, as shown in .

In Kenya, there were relative variations whereby 60 (58.25%) managers who responded to this question said no, against 43 (41.75%) who said yes. Also, even though most feel unfairness exists in how suspected wrongdoers are treated, there are pockets of fairness. It would appear that fairness would be more likely if a manager has no powerfully placed connections. In other words, how managers respond to fraud or ethical responsiveness by managers may be determined by organisational externalities like political clientelism or informal connections that transcend managerial hierarchies and accountability mechanisms.

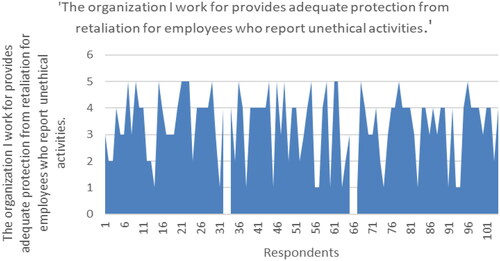

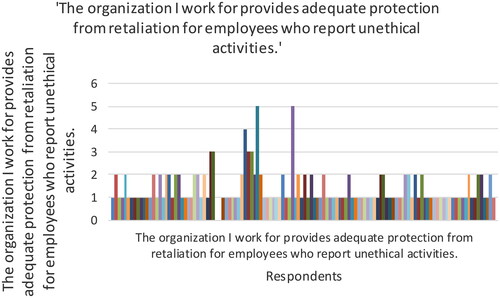

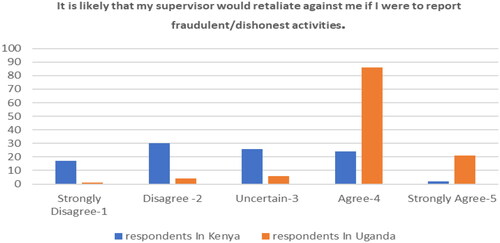

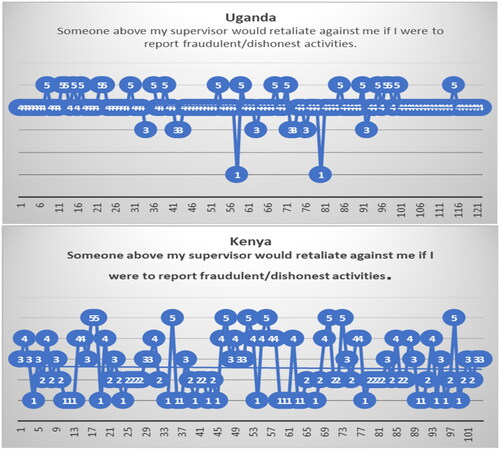

In a further interrogation, the respondents were asked to indicate (Strongly Disagree-1, Disagree-2, Uncertain-3, Agree-4, Strongly Agree-5): (i) whether their organisation provides adequate protection from retaliation for employees who report unethical activities, (ii) whether their organisation encourages employees to report fraudulent/dishonest activities, (iii) whether they are likely that their supervisor would retaliate against them if they were to report fraudulent/dishonest activities, (iv) whether someone above their supervisor would retaliate against them if they were to report fraudulent/dishonest activities, and (v) whether their coworkers would retaliate against them if they were to report fraudulent/dishonest activities. Responses are shown in and .

Table 1. Encouraging employees to report fraudulent/dishonesty in Uganda and Kenya.

Table 2. Response table by numbers in Uganda and Kenya.

On whether their organisations provide adequate protection from retaliation for employees who report unethical activities, twenty of them, representing 66.67%, are uncertain about the phenomenon. In contrast, six of them, representing 20%, agree. Five respondents, representing 16.67%, disagree that their organisations encourage employees to report fraudulent and dishonest activities. Seventeen of them, representing 56.67%, are uncertain about the statement. Eight of them, representing 26.67%, agree with it. Eight of the 26.67% of respondents disagree that their supervisors would likely retaliate against them if they were to report fraudulent and dishonest activities. Eighteen, representing 60%, are uncertain about the statement, while 4, representing 13.33%, agree with the statement.

Four respondents, representing 13.33% of Ugandans and nine or approximately 16.89%, strongly disagree that their organisations encourage employees to report fraud/dishonest activities. Overall, most agreed that their organisations encourage reporting of fraud/dishonest activities in both countries, where more than half (74 respondents) and 45 Kenyan respondents agreed. This goes in tandem with the responses concerning the availability of written policies, which may also mean that despite anti-fraud policies not being well communicated to managers and organisations, efforts are in place to encourage fraud reporting in organisations. Perhaps respondents may have interpreted the availability of a written policy against fraudulent activities as an organisational effort to encourage reporting such activities rather than considering the complexities of implementing or realising these policies when managers respond to fraudulent/dishonest activities.

The results of the likelihood that their supervisor would retaliate against them if they were to report fraudulent/dishonest activities are shown in .

From the above figure, most respondents (over 80%) in Uganda agreed that their supervisors might retaliate against them if they were to report fraudulent activities, with approximately 20% saying they agree strongly. Interestingly, in Kenya, less than half (slightly 30%) disagreed with this statement, followed by those who said they were uncertain (27%) and those who agreed (25%). These findings align with previously mentioned findings on protecting those willing to report fraud and whether suspects will be treated fairly regardless of their positions in the organisation. However, when further asked whether someone above their supervisor would retaliate against them if they were to report fraudulent/dishonest activities, Ugandan managers mostly agreed and strongly agreed, respectively. This differed from Kenyan managers, who gave more varied responses, with a relative majority of those who responded to this question disagreeing. The second majority either equally remained uncertain or agreed (15 respondents each) concerning this statement. shows the results.

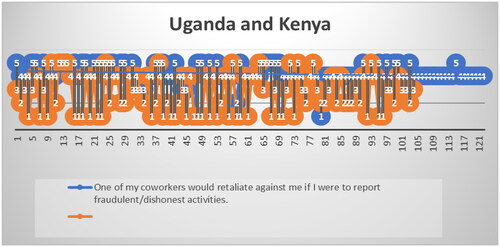

Besides considering how the above vertical organisational relations affect their responses to fraudulent/dishonest and mismanagement activities, Ugandan (blue bar) and Kenyan (orange bar) managers agreed that horizontal relations also matter. When asked whether their co-workers would retaliate against them if they were to report fraudulent/dishonest activities, the results are displayed in . Most agreed that coworkers are more likely to retaliate against managers if they report fraud within their ranks or organisations. A good number also strongly agreed with horizontal retaliation against those reporting fraud in Kenyan and Ugandan organisations. This may imply a prevailing organisational culture that tolerates fraud/dishonest activities in Kenyan public spaces. As indicated in the discussion section, where these data are further explained in light of the qualitative data findings, Ugandan and Kenyan managers’ responses to fraudulent activities are determined by their internal in addition to previously mentioned external organisational environments.

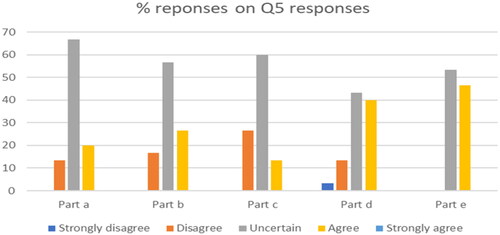

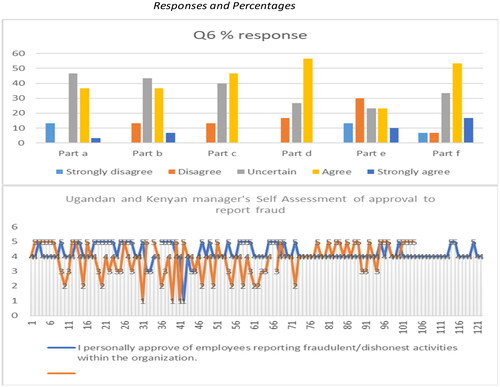

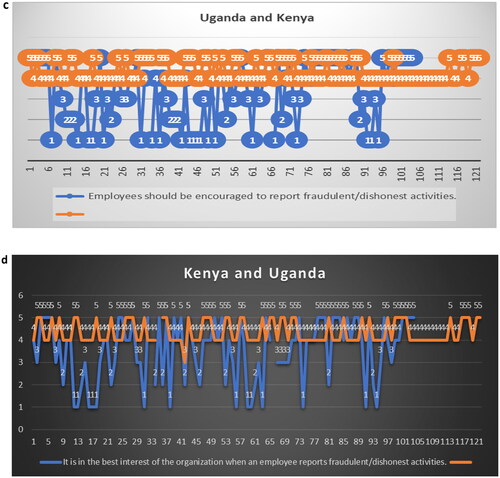

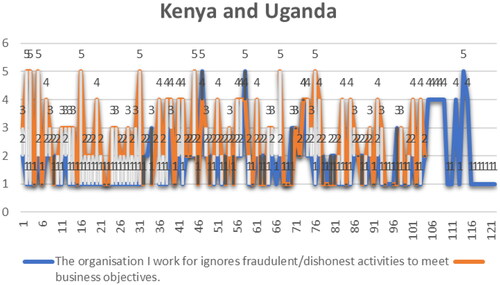

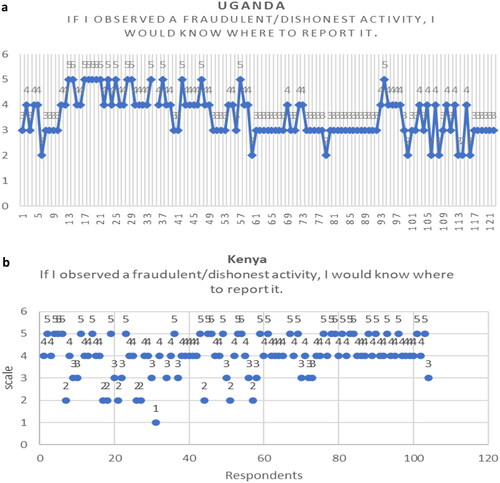

Furthermore, respondents were asked to indicate whether they agreed with the following statement (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). (i) I approve of employees reporting fraudulent/dishonest organisational activities. (ii) If I observed fraudulent/dishonest activity, I would know where to report it. (iii) If I observed fraudulent/dishonest activity, I would feel personally obliged to report it. (iv) If it is in the organisation’s best interest when an employee reports fraudulent/dishonest activities. (v) Employees should be encouraged to report fraudulent/dishonest activities. (vi) The organisation I work for ignores fraudulent/dishonest activities to meet business objectives. The findings were as shown in and below.

From , most Ugandan (represented by blue bar) and Kenyan (orange bar) managers agreed they would approve reporting fraud in their organisations. As individual self-assessment, responses to this question demonstrate managers’ consciousness of the need to entrench whistleblowing norms if they are to improve the ethical environments of their organisations. This may mean they would report fraudulent activities when they observe them. Therefore, when asked if they would feel personally obliged to report an observed fraud, most agreed and strongly agreed, but a good number also remains uncertain in both countries, as shown in and .

Figure 11. (a) Managers personally obliged to report fraud in Kenya. (b) Managers personally obliged to report fraud in Kenya. (c) Encouraging employees to report fraud (Uganda orange bar; Kenya blue bar). (d) Reporting fraud/dishonest activities is in the organisation’s best interest.

Even so, managers in both countries gave varied responses as to whether employees should be encouraged to report fraud. Ugandan managers were more optimistic than their Kenyan colleagues, mostly agreeing and strongly agreeing that employees should be encouraged to report fraud. In contrast, Kenyan managers showed uncertainty and disagreement on whether employees should be encouraged to report fraud, as shown in . This presents interesting insights and may paint a grim picture of organisational propensities toward improving ethical environments for potential whistleblowers.

Relatedly, when asked whether reporting fraud was in the organisation’s best interest, the findings reflect the findings made on whether employees should be encouraged to report it, as shown in . The result shows that most Ugandan (represented by the orange bar) and Kenyan (blue bar) managers agree and strongly agree that employees should report fraudulent activities because it is in the organisation’s best interest.

In addition, when asked whether they knew where to report fraudulent activities, the responses differed, with most Ugandan managers (53 in total) saying they were uncertain but also relatively agreeing (41), respectively, with this statement, as shown in . In contrast, most Kenyan managers agreed (47) against (35), who said they strongly agreed they knew where to report observed fraudulent activities in their organisations, as shown in . These findings may demonstrate the relative awareness of Ugandan and Kenyan managers concerning the existing mechanisms towards addressing fraudulent/dishonest and mismanagement challenges in their organisations. However, given the previous findings on whether employees should be encouraged to report fraud, where most Kenyan managers either strongly disagree or are uncertain, there could be issues with confidence in these mechanisms, especially in ensuring that potential whistleblowers are protected from retaliation. The latter has emerged more prominently in Uganda than in Kenya, as shown in the previous findings.

Figure 12. (a) Managers knowing where to report observed fraudulent/dishonest activity in Uganda. (b) Manager reporting observed fraudulent/dishonest activity in Kenya.

This positive attitude was further tested by investigating the general organisational propensity towards reporting fraud. Respondents were asked whether their organisations ignore fraudulent/dishonest activities to meet business or related organisational objectives. The findings provide hopeful trajectories, with most managers disagreeing and strongly disagreeing with this statement, shown in .

However, these findings differ between Kenya and Uganda, with most of the former disagreeing more strongly than the latter. Still, almost a significant number of respondents also felt that their organisations could ignore fraud if it threatens organisational or business objectives. For example, 28 respondents of the total number of respondents who answered this question agreed, 25 were uncertain, and 11 strongly agreed. In other words, even though most organisations may be encouraging fraud reporting, despite organisations inclined more towards addressing fraud/dishonest activities, Kenyan and Ugandan managers still feel there is a need to do more. These findings closely align with those concerning retaliatory actions within organisations if managers’ report fraud. The next section discusses these findings further.

Discussions

The implication of the findings above on ethics management can be discussed in three broad areas as follows.

Written policies and effective communication within organisations

Since ethics is a moral issue, its management relies on the moral perceptions of managers and workers. The moral perceptions of fraudulent activities, waste and mismanagement may go a long way to determining the likelihood of blowing the Whistle and other ethics management instruments. A written policy describing what employees should do when they observe or suspect wrongdoing is one step toward influencing these perceptions and normalising whistleblowing. It also nurtures an ethical culture and empowers employees. Written anti-fraud policies are essential in determining and defining integrity functions as part of ethics management instruments. The studied cases show intentional efforts by Kenyan and Ugandan managers based on the availability of anti-fraud policies in their organisations. This may indicate a development towards creating ethical behaviour and rectifying the problems that have come with the lack of written or ethical guidelines in African contexts, as was shown two decades ago in the case of Zimbabwe by Ngulube (Citation2000).

However, written policies should go beyond the broader provisions of the codes of conduct to stipulate regulations and mechanisms pertinent to fraudulent activities as ethics and integrity management issues. Due to their broader dispensations, codes of ethics alone have been ineffective in handling fraud and other related activities in public and private organisations (Shaibu et al., Citation2021; Shava & Mazenda, Citation2021). Therefore, one way of resolving ethical conundrums lies in drafting specific policies on what entails fraudulent activities. Determining and defining integrity functions are founded on whether organisations’ specific policies for suspected fraudulent/dishonest activities exist. This would be the first step in matching ethical behaviour to organisational objectives in public management.

Ugandan and Kenyan organisations seem to be on the right path by having these policies in place. In particular, whereas ethics management remains a challenge in both countries (e.g. Okpara & Mamman-Muhammad, Citation2022), these findings confirm those of Mayanja and Perks (Citation2017), showing that business managers in Uganda are concerned about “their management practices and ensure that all employees are knowledgeable [about] what ethical business conduct entails or how to apply it in the workplace.” This may imply that private organisation managers may be doing better at enforcing, monitoring, and guiding ethical management than public organisation managers in Uganda and Kenya. This may also explain why Ugandan managers experienced more extended ethics training than in Kenya.

Another issue, however, is whether the length of training would correlate positively with improved ethical behaviour. Studies have often related practical training to organisational performance in all areas, including ethics (Manyaka & Sebola, Citation2013; Kim & Lee, Citation2023). This would imply that the more managers are trained on ethics, the easier it will be to address ethical conundrums arising from their ignorance of codes of conduct and improve the chances of internalising written policies to define and determine fraud, waste, and mismanagement.

Moreover, consistent training is more likely to convert managers into champions of ethical behaviour, notwithstanding the pace of this conversion. In other words, if deontological logic is anything to go by, behavioural change within organisations may be a product of consistent and intentional training of managers on the general good, such as ethics being good for the overall interest of the organisation. This could explain the positive findings above, showing that most managers in Kenya and Uganda agreed that reporting fraud is generally good for their organisations’ best interests. However, it is not clear why Ugandan managers, despite having longer ethics training, were more uncertain than Kenyan managers on where to report fraud. Still, Ugandan managers are more likely to encourage others to report fraud than Kenyan managers, an issue that can be further deliberated on below.

Likelihood of blowing the whistle on fraudulent/dishonest activities

The findings indicate an extensive underlying culture of intolerance towards whistleblowing in the two countries, with Ugandan contexts slightly scoring lower than Kenya. The same trajectory is also reflected in the 2022/2023 survey findings by Afrobarometer, looking into ordinary citizens’ moral perceptions towards corruption and bribery. An overwhelming number of ordinary Kenyans (83.3%) against Ugandans (80.8%) stated that they feared retaliation if they reported corruption in the public sector. According to this survey, those who said they could report corruption without fear were 15.8% Kenyans against Ugandans at 17.3%. Similar country trajectories were reflected in the entire continent, confirming studies that have shown that in Africa, higher perceptions of corruption in public administration and the persecution of whistleblowers have exacerbated public trust deficits in oversight institutions (Uys, Citation2022), as many fears reporting wrongdoing to concerned authorities.

According to the Afrobarometer round 9 survey findings, 75.4% across Africa fear retaliation, against 22.6% who feel they can report corruption without fear (https://www.afrobarometer.org/online-data-analysis/; also see Tumuramye et al., Citation2018; Onyango, Citation2023a). In all, whistleblowing parameters are critical in mapping the quality of organisational or public leadership. It is essential to audit human resource policies on employees’ voices and citizenship or how employees and citizens engage in corporate or public affairs. Another thing is that whistleblowing parameters are central to employee voice and citizenship, which is critical for ethics management (see Mitonga-Monga, Citation2018; Kasekende et al., Citation2020).

This study provides insights into how Ugandan and Kenyan managers sit within these generally negative public moral perceptions in their countries and how they respond to fraud/dishonesty and mismanagement activities in their organisations. It agrees with studies that show that anti-fraud activities and waste policies are more likely to be normalised within organisational contexts through effective whistleblowing policies (Onyango, Citation2021b; Keenan, Citation2007). This should be done through staff training and other capacity-building strategies to improve the ethics management environment. Previous whistleblowing studies in Kenya (e.g., Hellmann et al., Citation2021; Onyango, Citation2021a) and Uganda (e.g., Tumuramye et al., Citation2018) show that whistleblowing in these contexts is informed by a complex mix of factors, including social demographics or social groupings, culture, and organisational variables. In addition, issues with high power distance or unequal power relations and informal social networks in Ugandan and Kenyan organisations (Matusitz & Musambira, Citation2013; Onyango, Citation2017), as evidenced by responses on whether fraud suspects will be treated fairly regardless of their position in the organisation.

However, their focus notwithstanding, most findings recommend a more intentional need to inculcate norms and develop effective feedback mechanisms to improve managers’ organisational responsiveness in Kenya and Uganda. The results show managers are still wrestling with issues of retaliation that could promote whistleblowing as a norm. This means anti-fraud and related ethics monitoring systems are needed to promote anti-fraud policies in public management in Kenya and Uganda.

Despite having policies in place, the Kenyan and Ugandan managers have not been adequately engaged and trained in the positive role of whistleblowing as an ethics management instrument. This could mean a problematic organisational culture and explain uncertain responses around whether managers could report fraud when they observe it and retaliatory fears from supervisors and co-workers. Studies show that for whistleblowing to become a fundamental policy tool against fraud and waste in organisations (Adeleye et al., Citation2020; Zipparo, Citation1998; Bowman & Knox, Citation2008), managers or organisations need to address legitimacy issues around it, as reported about Uganda (Mbago et al., Citation2018; Onyango, Citation2021a). Legitimacy building includes, as shown in this study, training managers and ensuring effective organisational responsiveness without discrimination, encouraging employees, through more intentional incentives, to report fraud and punishing culprits, their organisational position notwithstanding.

Encouraging and protecting whistleblowers

To enforce ethics management effectively, Kenyan and Ugandan organisations must be more intentional in encouraging and protecting managers and employees willing to report fraudulent activities. Current systems need improvement to protect whistleblowers. While the findings show managers’ will to report fraud, scepticism seems to prevail, indicating the existence of organisational and inter-personnel trust crises. Such scepticism or lack of trust has been found to prevail when there is a lack of adequate and non-discriminatory mechanisms and culture to take fraudulent reports seriously (Sakyi & Bawole, Citation2009; Miethe, Citation2019; Onyango, Citation2021a). As a result, encouraging and protecting potential whistleblowers remain a grey area in most organisational contexts in Uganda and Kenya.

Notably, reporting fraud, protecting whistleblowers, and taking action against culprits or their fair treatment should go hand in hand. It cannot be fragmented into units that may engage in sovereignty wars between managers. This is important in inculcating a whistleblowing culture in organisations (Shava & Mazenda, Citation2021; Zipparo, Citation1998; Brown et al., Citation2014). This study shows whistleblowing remains an issue that Ugandan and Kenyan organisations need to put more effort into guiding ethics management and integrity. A lack of whistleblowing mechanisms and culture reduces public trust (Brown et al., Citation2014; Onyango, Citation2023b) and threatens the effective implementation of anti-corruption policies (Onyango, Citation2021a).

Whistleblowing culture is a measure of knowing management ethics’ bill of health within organisational contexts and is central to building and sustaining public integrity. It only creates functional ethical systems if whistleblowers are encouraged and protected, so managers should score high on ethical activities. However, the fear of retaliation from supervisors and co-workers and the possibility that organisations may ignore fraudulent reports demonstrates a critical gap in ethics management in Uganda and Kenya. It confirms common findings that whistleblowing is likelier to be condemned and whistleblowers are likely to be considered snitches, informants, spies, moles, and traitors (Akerstrom, Citation2017; Miethe, Citation2019; Leys & Vandekerckhove, Citation2014). Consequently, even though managers mostly approved of reporting fraud, the retaliatory fears could promote silence instead of voice responses towards fraudulent activities and organisational mismanagement.

Conclusion

In ethics management, especially with regard to public affairs, understanding public and private managers’ moral perceptions and inclinations towards reporting and responding to fraud, waste and mismanagement in public service goes a long way toward informing the functionalities of public ethics infrastructures in developing contexts. An important focus in this paper broadly relates to and draws implications for the functions of the integrity management mechanisms for determining and defining integrity functions, guiding integrity norms, and monitoring and enforcing integrity functions. The findings above provide insights into current efforts to create an ethical climate in Uganda and Kenya while drawing implications for similar contexts in Africa. They inform practitioners on the status of implementing anti-fraud and wastage initiatives. Most importantly, it is shown that ethics management and integrity may be inadequate without the norms needed to make them work. Effective communication strategies are necessary for managers to internalise anti-fraud and written policies on waste or mismanagement in organisations. Also, managers need more than symbolic whistleblowing encouragement.

Moving forward, more research should show how African-based organisations can devise practical incentives and proactive responses to address fraudulent activities effectively and develop appropriate tools and ethics training to address retaliation from supervisors and co-workers. However, context matters, and researchers need to find ways that allow practitioners or managers to devise contextually specific tools that can be used to complement public management’s best practice approaches. This paper’s findings may shed light on ways African practitioners can strengthen ongoing regulatory reforms to promote organisational accountability mechanisms.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adeleye, I., Luiz, J., Muthuri, J., & Amaeshi, K. (2020). Business ethics in Africa: The role of institutional context, social relevance, and development challenges. Journal of Business Ethics, 161(4), 717–729. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04338-x

- Afrobarometer 2021/2023. Round 9 survey findings. Retrieved from https://www.afrobarometer.org/online-data-analysis/

- Akerstrom, M. (2017). Betrayal and betrayers: The sociology of treachery. Routledge.

- Andersson, S., & Ekelund, H. (2022). Promoting ethics management strategies in the public sector: Rules, values, and inclusion in Sweden. Administration & Society, 54(6), 1089–1116. https://doi.org/10.1177/00953997211050306

- Basheka, B. C. (2021). Public procurement governance: Toward an anti-corruption framework for public procurement in Uganda. In Public procurement, corruption and the crisis of governance in Africa (pp.113–141).

- Beeri, I., Dayan, R., Vigoda-Gadot, E., & Werner, S. B. (2013). Advancing ethics in public organisations: The impact of an ethics program on employees’ perceptions and behaviors in a regional council. Journal of Business Ethics, 112(1), 59–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1232-7

- Brown, A. J., Vandekerckhove, W., & Dreyfus, S. (2014). The relationship between transparency, whistleblowing, and public trust. Ala’i, P. and Vaughn, R.G. eds., 2014. Research handbook on transparency. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Bowman, J. S., & Knox, C. C. (2008). Ethics in government: No matter how long and dark the night. Public Administration Review, 68(4), 627–639. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2008.00903.x

- Bowman, J. S., & West, J. P. (2021). Public service ethics: Individual and institutional responsibilities. Routledge.

- Chapman, R. A. (1998). Problems of ethics in public sector management. Public Money and Management, 18(1), 9–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9302.00098

- Cooper, N. S. (2000). Speaking and listening to nature: Ethics within ecology. Biodiversity and Conservation, 9(8), 1009–1027. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008962316747

- Domfeh, K. A., & Bawole, J. N. (2011). Muting the whistleblower through retaliation in selected African countries. Journal of Public Affairs, 11(4), 334–343.

- Farazmand, A. (2002). Privatization and globalization: A critical analysis with implications for public management education and training. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 68(3), 355–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852302683004

- Frederickson, H. G., & Frederickson, D. G. (1995). Public perceptions of ethics in government. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 537(1), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716295537000014

- Hellmann, A., Endrawes, M., & Mbuki, J. (2021). The role of ethnicity in whistleblowing: The case of Kenyan auditors. International Journal of Auditing, 25(3), 733–750.

- Kasekende, F., Nasiima, S., & Otengei, S. O. (2020). Strategic human resource practices, emotional exhaustion and OCB: The mediator role of person-organization fit. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 7(3), 275–295. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-04-2020-0056

- Keenan, J. P. (2007). Comparing Chinese and American managers on whistleblowing. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 19(2), 85–94.

- Kim, M. Y., & Lee, H. J. (2023). Finding triggers for training transfer: Evidence from the National Human Resource Development Institute in Korea. Public Money & Management, 43(8), 825–832. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2023.2209904

- Lawton, A., Rayner, J., & Lasthuizen, K. (2013). Ethics and management in the public sector. Routledge.

- Lawton, A., & Macaulay, M. (2015). Ethics management and ethical management. In Ethics and integrity in public administration: Concepts and cases (pp. 107–119). Routledge.

- Leys, J., & Vandekerckhove, W. (2014). Whistleblowing duties. In Brown, A.J., Lewis, D., Moberly, R. and Vandekerckhove, W. eds. International handbook on whistleblowing research. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Lilla, M. T. (1981). Ethos, “Ethics,” and the Public Service. Public Interest, 63(1), 3–17.

- Maesschalck, J. (2004). Approaches to ethics management in the public sector: A proposed extension of the compliance-integrity continuum. Public Integrity, 7(1), 20–41.

- Manyaka, R. K., & Sebola, M. P. (2013). Ethical training for effective anti-corruption systems in the South African public service. Journal of Public Administration, 48(1), 75–88.

- Mayanja, J., & Perks, S. (2017). Business practices influencing ethical conduct of small and medium-sized enterprises in Uganda. African Journal of Business Ethics, 11(1), 43–62. https://doi.org/10.15249/11-1-130

- Matusitz, J., & Musambira, G. (2013). Power distance, uncertainty avoidance, and technology: Analyzing Hofstede’s dimensions and human development indicators. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 31(1), 42–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2012.738561

- Mbago, M., Mpeera Ntayi, J., & Mutebi, H. (2018). Does legitimacy matter in whistleblowing intentions? International Journal of Law and Management, 60(2), 627–645. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLMA-02-2017-0017

- Menzel, D. C. (2019). Ethics management in public organizations: What, why, and how? In Handbook of administrative ethics (pp. 355–366). Routledge.

- Miceli, M. P., Near, J. P., & Dworkin, T. M. (2009). A word to the wise: how managers and policy-makers can encourage employees to report wrongdoing. Journal of Business Ethics, 86(3), 379–396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9853-6

- Miethe, T. (2019). Whistleblowing at work: Tough choices in exposing fraud, waste, and abuse on the job. Routledge.

- Mitonga-Monga, J. (2018). Ethical climate influences on employee commitment through job satisfaction in a transport sector industry. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 28(1), 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2018.1426710

- Ngulube, P. (2000). Professionalism and ethics in records management in the public sector in Zimbabwe. Records Management Journal, 10(3), 161–173. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000007262

- Odhiambo, W., & Kamau, P. (2003). Public procurement: Lessons from Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. In OECD Development Centre: Working Paper No. 208; OECD iLibrary:, 2003; pp. 1–20. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1787/804363300553(accessed on 28 January 2024).

- Okpara, N., & Mamman-Muhammad, A. (2022). Imperatives of Anti-corruption Initiatives in Enhancing Public Service Delivery in Africa. In Ethics and accountable governance in Africa’s public sector, volume II: Mapping a path for the future (pp. 105–129). Springer International Publishing.

- Onyango, G., & Akinyi, O. M. (2023). Gender-responsiveness of public procurement and tendering policies in Kenya. In Gender, vulnerability theory and public procurement (pp. 119–135). Routledge.

- Onyango, G. (2023a). The post-COVID-19 economic recovery, government performance and lived poverty conditions in Kenya. Public Organization Review, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-023-00732-2

- Onyango, G. (2023b). How mafia-like bureaucratic cartels or thieves in suits run corruption inside the bureaucracy, or how government officials Swindle Citizens in Kenya!. Deviant Behavior, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2023.2263136

- Onyango, G. (2021a). Whistleblowing behaviours and anti-corruption approaches in public administration in Kenya. Economic and Political Studies, 9(2), 230–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/20954816.2020.1800263

- Onyango, G. (2021b). Whistleblower protection in developing countries: A review of challenges and prospects. SN Business & Economics, 1(12), 169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43546-021-00169-z

- Onyango, G. (2017). Collectivism and reporting of organisational wrongdoing in public organizations: The case of county administration in Kenya. International Review of Sociology, 27(2), 353–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/03906701.2017.1298429

- Osei, C., & Gbadamosi, A. (2011). Re‐branding Africa. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 29(3), 284–304. https://doi.org/10.1108/02634501111129257

- Sakyi, E. K., & Bawole, J. N. (2009). Challenges in implementing code of conduct within the public sector in Anglophone West African countries: Perspectives from public managers. Journal of Public Administration and Policy Research, 1(4), 68–78.

- Shaibu, S., Kimani, R. W., Shumba, C., Maina, R., Ndirangu, E., & Kambo, I. (2021). Duty versus distributive justice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nursing Ethics, 28(6), 1073–1080. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733021996038

- Shava, E., & Mazenda, A. (2021). Ethics in South African public administration: A critical review. International Journal of Management Practice, 14(3), 306–324. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMP.2021.115107

- Tumuramye, B., Ntayi, J. M., & Muhwezi, M. (2018). Whistle-blowing intentions and behaviour in Ugandan public procurement. Journal of Public Procurement, 18(2), 111–130. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOPP-06-2018-008

- USMSPB. (1981). Sexual Harassment in the Federal Workplace: Is it a Problem. A report of the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board Office of Merit Systems Review and studies. Retrieved on 12/02/2024 from https://www.mspb.gov/studies/studies/Sexual_Harassment_in_the_Federal_Workplace_Is_it_a_Problem_240744.pdf

- Uys, T. (2022). Whistleblowing and the sociological imagination (pp. 1–23). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vincent, O., & Evans, O. (2022). Public sector branding in Africa: Some reflections. In Public sector marketing communications, Volume I: Public relations and brand communication perspectives (pp. 19–40). Springer International Publishing.

- Yeboah‐Assiamah, E., Asamoah, K., Bawole, J. N., & Buabeng, T. (2016). Public sector leadership‐subordinate ethical diffusion conundrum: Perspectives from developing African countries. Journal of Public Affairs, 16(4), 320–330. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.1589

- Zipparo, L. (1998). Factors which deter public officials from reporting corruption. Crime, Law and Social Change, 30(3), 273–287. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008326527512