ABSTRACT

International Organisations (IOs) can expand their mandate by employing deliberately chosen strategies. I propose that IOs' mandate expansion follows a two-step sequence: First, IOs branch out into a domain that lies outside of their initial mandate area. Second, IOs further increase their relevance within the domain and move their position from a marginal to a more focal one. To accomplish the two-step expansion, individual IOs use a particular mix of strategies, reflecting their organisation-specific contexts as well as external environments. The two-step sequence is explored in the case of the OECD's growing involvement in the health policy field from the organisation's establishment in 1961 until 2022. I employ a mixed-method approach, combining structural topic modeling and qualitative document analysis. This article highlights the different stages of IOs' mandate expansion and contributes to enriching the research streams of IOs' institutional changes and dynamics in global health governance.

1. Introduction

Global health governance has undergone manifold transformations over the past decades. Pertinent scholarly engagement illustrates the rapid proliferation of multi-level actors in the institutional landscape and the pluralisation of approaches to and agendas for global health (Hanrieder Citation2018; Kaasch Citation2010; McInnes Citation2018). Among various actors, International Organisations (IOs) are one of the most prominent actors that have increasingly expanded their involvement in health policy (Niemann, Krogmann, and Martens Citation2023, 284). Multiple IOs with their initial mandates far away from the health sector successfully expanded their work into the health policy field. The World Bank (WB), for instance, became a preeminent actor in promoting Universal Health Coverage through its developmental programmes, which does not belong to the initial mandate of stablising the postwar international economic order. Combined with several other factors, the increase of IOs involved in health policy reshaped the ecology of global health governance by weakening the World Health Organization’s (WHO) focal position and diffusing authority across global health horizontally as well as vertically (McInnes Citation2018).

Although not as known as the WHO or WB, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has rapidly expanded into the health domain, notably since the early 2000s with the OECD Health Project (2001-2004) and the subsequent institutionalisation of the health work through the creation of the Health Division (Carroll and Kellow Citation2011, 243; Kaasch Citation2010, 183). Today, the OECD’s health portfolio consists of an extensive range of health topics, from public health management to the adoption of AI in health care. Moreover, the IO responded to the COVID-19 pandemic with nearly 250 policy briefs and further voluminous data, assisting policymakers of the OECD countries and beyond in the crisis management process. In other words, the OECD’s health-related activities suggest that the IO has not only expanded its mandate into a new policy domain of health but is also increasingly stretching within it.

Surprisingly, most scholarly works on global health governance do not count the OECD as a health actor despite the IO’s ever-growing commitment. While only a handful of literature examines the OECD in the context of health policy, they provide us excellent insights into the IO’s relevance in the health sector: Some studies shed light on the environment within which the OECD was situated with a particular focus on the internal dynamic within the organisation during the expansion into the health policy field (Carroll and Kellow Citation2011; Citation2021; Kaasch Citation2010). Other studies examine the ideological principles embedded in the IO’s policy ideas and recommendations for specific health topics (Deacon and Kaasch Citation2008; Deeming and Smyth Citation2017; Kaasch Citation2021). Yet, no previous study analysed the OECD’s mandate expansion in global health governance by comprehensively investigating the IO’s health activities throughout its organisational history from 1961 to today. As a result, we know little about to what extent, in which time periods, and through which strategies the OECD has moved beyond its initial mandate into the health domain and enhanced its relevance within the new field.

This research gap is intriguing, particularly because International Relations (IR) scholars have recently drawn vast attention to the phenomenon of IOs’ mandate expansion (Barnett and Coleman Citation2005; Barnett and Finnemore Citation2004; Hall Citation2013; Citation2015; Kreuder-Sonnen and Tantow Citation2022; Lenz et al. Citation2022; Lesage and Van de Graaf Citation2013; Littoz-Monnet Citation2017; Citation2021; Ruger Citation2005). In principle, IOs receive mandates from states. A mandate is a states’ formal delegation to take charge of sets of problems in specific policy fields, which confer IOs rational-legal authorities to act as legitimate actors (Barnett and Finnemore Citation2004). Mandates, however, are often broad and do not precisely outline what has to be done or how. Thus, IOs are expected to interpret and adjust the given mandates by defining their responsibilities and activities (Bradlow and Grossman Citation1995, 412). In this process, “the agenda, interests, experience, values, and expertise of IO staff heavily color any organisations’ response to delegated tasks” (Barnett and Duvall Citation2005, 172). Given that IOs are purposive actors with independent interests (Barnett and Coleman Citation2005; Barnett and Finnemore Citation2004), they remain flexible to new ideas and (re)develop their goals and strategies (Béland and Orenstein Citation2013). As a result, some IOs outgrow the tasks initially given to them, “taking on new missions, mandates, and responsibilities in ways not imagined by their founders” (Barnett and Finnemore Citation2004, 3). Despite valuable achievements, previous studies tend to be limited in IOs’ mandate expansion into a new policy domain, leaving the further expansion within that domain unaddressed. In other words, it remains obscure how IOs, after successfully placing themselves in a new policy arena, further advance their relevance within that newly joined area.

Connecting the unanswered question of the OECD’s actorness in global health governance to the IR literature of IOs’ mandate change, I propose that IOs’ mandate expansion follows a two-step sequence, which IOs achieve by employing a range of deliberately chosen strategies. The first step pertains to mandate expansion into a new policy field. In this step, IOs branch out into a domain that was not contained in their initial mandate. The second step is mandate expansion within the new policy field, in which IOs increase the extent of their involvement and become a more focal actor within the policy area. For accomplishing the two-step mandate expansion, each IO identifies and utilises a set of strategies. IOs are known to apply subtle mechanisms and tactics to expand their work domains (Littoz-Monnet Citation2021; Schemeil Citation2013), and their choice of strategies reflects the negotiation between the internal and external environments, in which they operate (Barnett and Coleman Citation2005). The two-step sequence of IOs’ mandate expansion through each IO’s context-specific strategies is explored in the case of the OECD’s mandate expansion in global health governance. By tracing the growth of the OECD’s health work in the last six decades, this article contributes to enriching the research streams of IOs’ institutional change and the architecture of global health governance.

The article is structured into five sections. The first section outlines the theoretical framework for the analysis of IOs’ mandate expansion. This section also contextualises the OECD to investigate its practice of mandate expansion. The second section explains the data collection criteria and methodology applied to this article. I use the OECD’s health-related publications between 1961 and 2022 as data and apply a mixed-method approach that integrates structural topic model and qualitative document analysis. Then, I show the results of the topic model that reveal how the OECD has increasingly dilated its work in health policy. In the next section, I analyse the OECD’s mandate expansion into and within the health policy field in complementing the topic model results with in-depth document analysis. Finally, the conclusion gives a brief summary of the evolution of the OECD’s health mandate in two phases and includes the implication of the findings to future research.

2. Theories for analysing IOs’ two-step mandate expansion strategies

In this section, I first theorise the two-step sequence of IOs’ mandate expansion that is composed of expansion into and within a new policy field. After introducing the theoretical framework, I contextualise the OECD and introduce my hypothesis on the OECD’s strategic mandate expansion.

2.1. IOs’ mandate expansion in a two-step sequence

IOs’ mandate expansion consists of a two-step sequence. The two-step model presents two different types of expansion, i.e. expansion into and within a new policy field, which take place in consecutive order. The first step is moving into a new field beyond the initial mandates. Some IOs do not remain in the mandate they were once given but broaden their work by expanding into other policy domains, for instance, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees into climate change displacement (Hall Citation2013). For numerous IOs, this first step of expansion is a matter of “adapt or perish.” (Schemeil Citation2013, 221). In particular, most IOs that were established to fulfil a temporary mission in the post-World War II reconstruction phase needed to enlarge their mandates in line with changing contexts in order to survive (Schemeil Citation2013, 220). IOs’ attempt at the first step of expansion is identifiable in their activities in a new policy field, which can be materialised as conducting projects, authoring reports, and participating in the pre-existing networks in the new field. Completing the first step means obtaining the formal mandate to act in the field by member states. The formal acknowledgment of a new mandate varies depending on each IO’s context, such as the working modus and bureaucratic structure. It may lead to, for instance, changes in an IO’s organisational structure with the creation of a new unit that is in charge of the activities regarding the new policy area, as well as the integration of the new work into the IO’s mission statement.

The second step of mandate expansion takes place when an IO moves its marginal position towards a more central place by increasing involvement and relevance within the policy field the IO entered. After a successful expansion into a new policy sector, IOs can enlarge their involvement further in the new policy domain and advance their relevance.Footnote1 This step is different from IOs’ consolidation in their original mandate areas to the extent that the second step of expansion is a consecutive step following IOs’ mandate expansion into a new policy sector. In a policy field where several IOs operate, individual IOs cooperate with each other and, at the same time, demarcate their position vis-à-vis other IOs (Kranke Citation2022). This constellation formulates organisational complexities, in which status differences among IOs emerge. As a result, some IOs are more focal and consequential than others, and possess the power to mobilise other actors in the framework of their governance goals (Abbott et al. Citation2015, 7). Those IOs in a central position are considered more relevant and thus authoritative, while IOs in a peripheral position play a rather marginal role and orientate themselves to the central IOs (Vetterlein and Moschella Citation2014, 150–151). New IOs in an established policy field have a higher chance of being placed in a rather marginal position just after the first step of expansion. They are thus expected to seek for cooperation with the pre-existing focal IOs within the field, since such collaboration benefits them to broaden their pool of networks, legitimacy, and resources (Hanrieder Citation2015, 192). A marginal IO also deepens its involvement and intensifies relevance by widening the approach, scope, and scale of relevant activities in the new field, and making more plausible claims based on solid evidence (Sellar and Lingard Citation2013). IOs’ efforts to progress in this step can lead to, among other activities, the specialisation of their perspectives and competence that elevate their engagement, and the diversification and proliferation of their policy portfolios. When an IO, started as a marginal one, moves its status to a more central one, the second step of expansion can be considered achieved.

Reference to the quantifiable aspects of an IO’s activities relevant to mandate expansion, such as the amounts of projects, research topics, and publications, allows us to operationalise the assumptions. However, it is noteworthy that the expansion of an IO’s relevance in a policy sector or the temporal span of such expansion is not absolute but relative. Given that each IO has different organisational features, such as working modus, governing mechanisms, and resources, I do not provide a quantitative benchmark or metric to measure IO’s mandate expansion. Instead, for the purpose of this study, I suggest some indicators to identify the completion of each step of expansion. The accomplishment of the first step of expansion can be visible in formal mandate delegation from member states to an IO. Mandate delegation to an IO may lead to, for instance, changes in an IO’s organisational structure with the creation of a new unit that is responsible for the new policy area, as well as the member states’ formal commission of projects with budget allocations in the new policy domain. When it comes to the completion of the second step of expansion, a marginal IO’s position transformation to a more focal one can be reflected in the IO’s global leadership in exerting influence over other actors and promoting cooperation with them for joint efforts to achieve its governance aims and activities (Abbott et al. Citation2015). In this sense, if an IO takes the lead in setting global aims, designing initiatives, and formulating and facilitating a network of collaboration with broader actors, the IO is considered to have completed the second step of expansion.

In order to carry out the two-step sequence of mandate expansion, IOs mobilise various strategies (Littoz-Monnet Citation2017; Citation2021). Although a number of strategies should exist for mandate expansion, I borrow Littoz-Monnet’s (Citation2021) three-fold tactics to patternise IOs’ strategies: First, IOs naturalise their expansion by framing the intervention as a legitimate action for the policy area and connecting the new domain with their mandates (“naturalisation”). Second, IOs rationalise their expansion by putting forward their expert authority, which often involves representing expert knowledge, including statistical information and analytical skills, and joint work with renowned experts within the field by joining the epistemic community constituting global authority (“expertisation”). Third, IOs technicalise their expansion, proclaiming their role in the new domain as neutral managers or mediators that facilitate exchanges and coordination (“technicalisation”). As Littoz-Monnet (Citation2021, 860) puts it, these tactics can “be mobilized alternatively or simultaneously”. While she does not specify what determines the different mix of the three strategies among IOs, I assume that IOs decide and flexibly change their strategy sets during the first and second steps of mandate expansion by adapting to external environments surrounding them (Barnett and Colemann Citation2005; Schemeil Citation2013), and internal features, such as bureaucratic structure (Trondal Citation2016), the logic of behaviours (Hall Citation2013), available resources and internal dynamics (Meier and Martens Citation2024).

In the specific context of global health governance, this article applies four health dimensions that an IO can approach, namely, bio-medicine, economism, security, and human rights (Lee Citation2009). In global health governance, constituting these perspectives, IOs can focus on single or multiple dimensions of health agendas. According to Lee’s (Citation2009) categorisation, the bio-medical dimension advocates for efforts to control major diseases based on scientific research and technology. Economism approaches global health with economic rationalism to increase political attention to, and resources for, specific health issues. The security perspective defines global health as a new security agenda and focuses on issues such as acute epidemic infections and bioterrorism. Lastly, the dimension of human rights, understanding health as a fundamental right, underlines more equitable health access and services for marginalised groups. For instance, while the WHO’s work covers all four categories, the WB’s activities in the health field focuses on economism, heralding the spread of neoliberal health policies (Lee Citation2009, 32). Building on this classification, IOs can broaden their spectrum of health work by diversifying their approach to health or specialising in a certain dimension. An investigation on which domains the OECD entered and specialised in further helps us understand the OECD’s position within the architecture of global health governance.

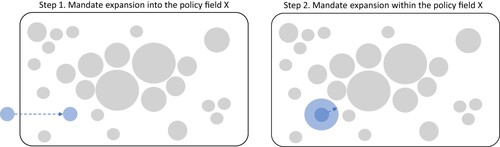

The two-step sequence of IOs’ mandate expansion, which consists of expansion into and within a new policy area, can be described as . Each circle represents an IO in the architecture of a policy field. The size of each circle symbolises the relevance of the IO within the policy field. The first step of mandate expansion is visualised as the blue circle, representing an IO, moves into the policy field X. In the following second step, the IO expands its relevance within the policy field X. This article narrows down the strategies IOs use in both steps to naturalisation, expertisation, and technicalisation (Littoz-Monnet Citation2021). Moreover, it applies four health dimensions that an IO can expand into, namely, bio-medicine, economism, security, and human rights (Lee Citation2009). The two-step sequence model sheds light on IOs’ strategic behaviours of increasing their involvement and relevance in two respective stages.

2.2. Contextualising OECD’s mandate expansion in health governance

The OECD is a constantly evolving IO with the economic focus at the core. While Article 1 of the OECD Convention explicitly states the purpose of the IO as promoting economic growth (OECD Citation1960), the IO’s view on the “ideal” look and the correspondent conditions of economic advancement have continued to change over time (Leimgruber and Schmelzer Citation2017; Woodward Citation2022). The Convention allows sufficient room for new interpretations since it does not prescribe through which specific instruments and measures the economic growth should be pursued (Carroll and Kellow Citation2011, 258). As a result, by applying the evolving economic view, the OECD has increasingly enlarged its activities across various policy fields, such as education (Niemann and Martens Citation2018; Sellar and Lingard Citation2013) and family policy (Mahon Citation2019). Particularly, Sellar and Lingard (Citation2013, 921) describe the OECD’s way of stretching the economic orientation to education policy as a simultaneous process of “economisation” of education policy and “educationisation” of economic policy. In other words, while the OECD’s economic-centered view is an institutionalised pillar that constitutes the norms, routines, and operating procedures of the IO, the economic philosophy is not fixed in its nature. This flexibility, in turn, enables the IO to augment its tasks in diverse policy fields. Drawing on this salience, one can assume that mandate expansion is a routinised practice for the OECD rather than a rare or shunned event. Moreover, given the IO’s proactive reconstruction of the meaning of its initial mandate in economic growth, I expect that the OECD relies on the naturalisation strategy by associating the economic mandate with the health policy field, and its primary health focus lies in the health domain of economism.

The OECD’s other organisational trait consists of its extensive data collection and comparative analysis skills. By framing issues, providing tools to measure those issues, and recommending policies backed by data, the OECD socialised itself as an expert that serves member states and beyond (Leimgruber and Schmelzer Citation2017; Martens and Jakobi Citation2010). The statistics the OECD produces “extensive, expensive, hard to gather, statistical portraits” that “no one can avoid using” (Marmor, Freeman, and Okma Citation2005, 340). The OECD’s policy ideas and recommendations based on expertise exert so exponential influence that even a critic of the IO admits the quality of expertise in scoffingly describing the OECD as having “nothing but the better argument” (Marcussen and Trondal Citation2011, 601). Expertise is of particular importance for the OECD because it relies on soft law as the primary governing mechanism. The OECD contributes to global governance, not through funding capacities like the WB or the International Monetary Fund (IMF), but through its expertise that convinces member states and even further actors beyond the OECD countries to adhere to the OECD’s arguments (Martens and Jakobi Citation2010; Trondal et al. Citation2010, 68). Accordingly, the OECD’s expertise is widely acknowledged as the IO’s core currency of power. This leads to the frequent comparisons of the IO to an epistemic community, think tank, or research institution (De Francesco and Radaelli Citation2023; Kallo Citation2021; Marcussen and Trondal Citation2011; Rautalin, Syväterä, and Vento Citation2021; Woodward Citation2022). Considering the OECD’s expertise-drivenness, I posit that expertisation may have served the IO as a crucial strategy in expanding the mandate into and within the health policy field.

3. Methodology

The approach taken in this study is a mixed methodology of computational and qualitative text analysis. The study examines documents because documents are the tools that serve politics and governments to (re)produce their ways of thinking and translate scientific knowledge into social practices (Freeman Citation2006, 52). Hence, an analysis on the OECD’s health-related publications can reveal how the IO approaches global health, what knowledge and ideas it produces, and which specific intent it wants to be read. To investigate the OECD’s two-step mandate expansion in the health sector, I first apply topic modeling. While computational methods for text analysis have seen a huge surge across disciplines in social science over the past decade, the topic modeling method is still relatively new in IO studies. Since topic modeling makes it easier to work with a large corpus of documents by treating each text as a combination of topics, this research benefits from this method to examine the OECD’s health-related documents published between 1961 and 2022. The reason to focus on topics within documents is that the OECD works on specific health policy issues chosen among the broad spectrum of health subjects, based on the particular importance the issues imply to its member states (Kaasch Citation2010, 181–182). The resulting topics from the documents selected for this study are supposed to be the IO’s most important health subjects and hint at when the OECD started, amplified, and diversified its activity in the health policy area. This way, the model discloses the organisation’s mandate expansion scope and speed as well as the specific time points of expansion into and within the health policy sector. Then, the topic model is complemented by qualitative document analysis for further investigation of the OECD’s mandate expansion strategies. I focus on some of the OECD’s health-related publications from the entire corpus used for topic modeling, which present the IO’s most highlighted health topics of each decade according to the topic model result. I also refer to additional documents released by the OECD, which show the Secretariat’s internal vision and orientation, as well as academic articles on the OECD’s engagement in the global health sector. The qualitative analysis also examines the interactions between the OECD and its environment, such as the IO’s responses to global socioeconomic developments and dynamics between the IO and relevant actors in the field, sine the evolution of exogenous environment and IOs’ intrinsic features are intertwined (Abbott, Green, and Keohane Citation2016).

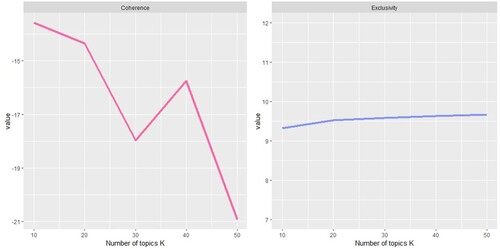

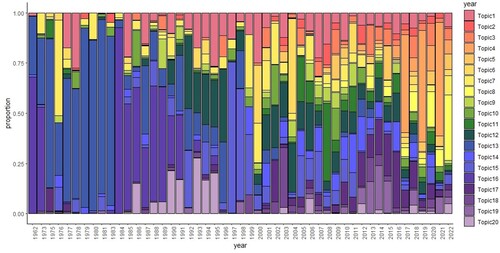

Among multiple topic modeling tools, I apply the Structural Topic Model (STM), because this study applies the time variable to unfold the changing composition of the OECD’s health topics in the last six decades. In general, STM is a framework of unsupervised algorithms that incorporate a covariate and identify latent topic presentations within a text corpus (Roberts, Stewart, and Tingley Citation2018). When feeding an STM with a text corpus, the model extracts multiple sets of words and each set counts as a topic. The words belonging to each topic are supposed to be coherent with each other while distant to words belonging to other topics. The extent of semantic coherence within and exclusivity between topics varies depending on how many topics one computes. Based on the coherence and exclusivity calculation for the OECD case study, the optimal outcome is predicted when extracting 20 topics (). The topic model posits that a single document consists of multiple topics with different proportions. For instance, a document can consist of 75% of words belonging to topic A, 15% of words from topic B, and 10% of words from topic C. Based on this principle, a topic model can assign each document in the text corpus to a single topic, which makes up the highest proportion of the document. This listing helps identify documents belonging to specific topics to conduct the subsequent in-depth analysis.

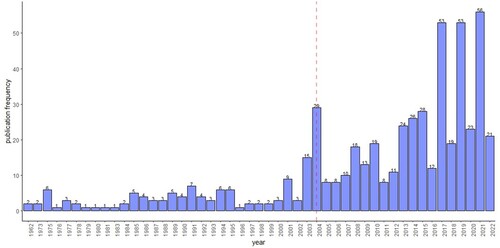

The text corpus used for this study consists of the 548 health-related publications that the OECD released from its founding in 1961 until September 2022 (). The documents were primarily collected from the IO’s online archive between September and October 2022, and then supplemented by additional collection at the offline archive of the OECD Paris headquarters in November 2022. The data was all accessible publicly at the time of collection. The search criteria included the following conditions: the search keyword “health”; classified as “publication” containing working papers, policy briefs, and monographs; written in English; and authored by the OECD. No data was available for 1961, 1974, 1982, and the years between 1963 and 1972. The selected data are produced by numerous directorates, divisions, and committees (Appendix 1), either by individual working units or as a result of cross-unit collaboration. Since the creation of the Health Division in 2004 (red-dotted), the Health Division has been the principal author.

4. Results

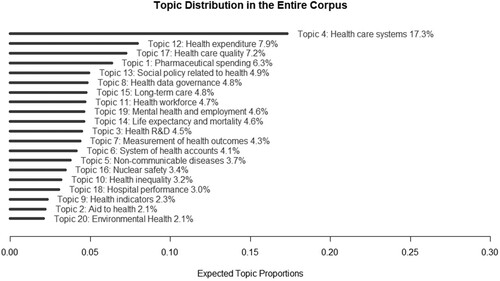

The STM results show the enlargement of the OECD’s involvement in the health sector from the modest beginning to today’s proactive actorness with an outstretched spectrum of health topics and publication volumes. In , The 20 most prioritised health topics reveal the OECD’s general preference in the long-term concerning its health-related activities; the IO’s primary concern has revolved around the topic Health care system. Given that the second to fourth most highlighted health topics are also associated with financial and quality aspects of the health care systems, it becomes even clearer that the IO puts special emphasis on the health care system. , in complementing , presents the accelerated speed of the IO’s engagement around the early to mid-2000s. Before the 2000s, especially starting from the 1980s, the annual publication volumes had inconsistently increased and topics became diversified to a modest extent at a relatively slow speed. This trend has been sharply contrasted since the 2000s, showing remarkable amplification in both publication volumes and contents. The publication volume after 2004 articulates circa 80% of the entire health publications between 1961 and 2022, while the IO’s topic preference spread across various topics, bringing divergence into the IO’s portfolio of health issues it deals with (; ).

Table 1. Most highlighted health topics in each decade.

5. The OECD in global health governance

This section unfolds the OECD’s two-step mandate expansion into and within the health policy field by juxtaposing the STM results and the closer examination of the IO’s specific activities in each period (). The OECD’s first step of expansion into the health policy field dates back to the 1970s with the recognition of the attachment of health to economic growth. After completing the first step of expansion by the mid-2000s, the OECD’s involvement in the health sector became further elaborated in both quantity and quality, which indicates the IO’s further expansion within the field.

Table 2. Overview of the OECD’s two-step mandate expansion.

5.1. Frist step of mandate expansion into health policy

5.1.1. The 1970s

The minor role, if any, in the health policy field in the 1960s slowly began to change during the 1970s through naturalisation and expertisation in the context of the topic Social policy related to health in particular. First, it was the OECD’s repeated reconstructions of its economic philosophy that justified the inclusion of health in the agenda. In the early 1970s, a lively debate was underway within the organisation on the nature and meaning of the initial mandate in promoting economic growth. This debate resulted in reinterpreting the use of economic advancement to help improve human well-being (Leimgruber and Schmelzer Citation2017, 37–38; Woodward Citation2022, 23–24). Consequently, the IO selected eight qualitative indicators to consider in economic planning processes, which included health as one of them (OECD Citation1973). In this way, health became linked to the IO’s initial mandate, naturalising the IO’s concerns about health. Second, the OECD expertised its involvement in health policy by comparing the OECD countries’ health expenditure as a part of social expenditure and problematising the rising social spending in the face of the global economic turbulence after the collapse of the Bretton Woods System (1971), the Oil Crisis (1973), and the subsequent stagflation (e.g. OECD Citation1977a; Citation1977b). Particularly, while urging for better controlling and improving efficiency and effectiveness of health expenditures, it provided analytics of the estimated financial benefits and costs of different health policies that were conducted in various OECD countries (OECD Citation1977b). Those analytics drew remarkable attention from the member states because the WHO’s analytics put its focus on Global South countries (Carroll and Kellow Citation2011, 237–238). The OECD also pointed out the need to improve the quantity and quality of data in measuring and comparing the effectiveness of health care systems (OECD Citation1977b, 7), and, simultaneously, it initiated the development of an extensive database of public health expenditures.

In this phase, the OECD’s involvement displays heterogeneous views on health. On the one hand, given that the IO integrated health into one of the essential factors to improve the quality of human life in the early 1970s, to some extent the OECD’s approach can be seen to reflect the human rights perspective. However, the IO’s health-related work at this stage involved the human rights dimension only marginally, without being developed into further discussion on addressing the health issues of marginalised groups, such as inequity in health care access and health outcomes. Indeed, the humane aspect only had a short life and almost disappeared soon after the economic turmoil unfolded with far-reaching repercussions on public expenditures. Since the mid-1970s, the view based on economism shaped the OECD’s health work. The policy solutions the IO suggested implied market orientation, for instance, increasing individual charges for health services and promoting competition in health services that “extract payment for things […] people might well be willing to pay” (OECD Citation1978, 100). Hence, the IO’s interests focused on the economic domain of health, with only a limited orientation towards the human rights domain during the 1970s.

5.1.2. The 1980s

The IOs’ stretch into the health sector through dealing with the topic Nuclear safety shows a mix of three strategies and the approach to health based on the security perspective. First, in the aftermath of the two oil crises in the 1970s and the OECD countries’ interest in nuclear power as an economical alternative energy source (Char and Cshik Citation1987), the OECD mobilised the Nuclear Energy Agency (OECD/NEA) as the main body to naturalise its participation in the growing global debate on the nuclear safety issue. Stressing the magnitude of the economic impacts of radioactive accidents as well as the economic benefits of nuclear energy over oil, the OECD/NEA expanded its work that previously focused on the R&D for commercial and industrial development of nuclear energy into the new role in the health, safety, and regulatory area (OECD/NEA Citationn.d.; Citation1985; OECD Citation1983). Second, the OECD built the authority to act in this matter by utilising in-house expertise to produce analysis reports on the health impacts of radioactive exposures and existing regulatory policies in the OECD countries (OECD/NEA Citation1984a; Citation1985; Citation1987). For instance, one part of the study analyses human health effects divided into early, late, and genetic effects of accidental exposure to radioactive material to the succeeding generations as well as exposed populations (OECD/NEA Citation1984a). After the Chernobyl accident (1986) that called for joint global efforts for safety regulation, the OECD also joined the network of experts in the nuclear and health sector, including the WHO, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), and national authorities. In this fashion, it joined the epistemic community constituting global authority and increased the credibility of its involvement in the health aspects of nuclear energy. Third, the IO technicalised its work in nuclear safety issues by taking the role of a mediator for exchanges among countries and evaluator of national safety programmes. The OECD/NEA’s main contribution during the 1980s was to develop guidelines, standards, and criteria for operational radiological protection and public health (OECD/NEA Citation1984b). In addition, in the framework of the IAEA’s safety evaluation programmes, the OECD/NEA participated in the Incident Reporting System, in which it facilitated international conversations and information dissemination on the nuclear plant operations experience. Taken together, the IO profited from all of the three strategies to stretch into nuclear power-related health issues during the 1980s.

5.1.3. The 1990s

The 1990s witnessed the OECD’s intensive use of expertisation and naturalisation in the health domain of economism, which led to the centralization of data collection within the IO and the deeper embedment of the organisation-wide economic philosophy in health policies. On the one hand, the OECD’s expertise justified the IO’s work on the topics of Health expenditure and Long-term care. The in-house expertise on health, which was scattered across a range of directorates before the 1990s, became coordinated under the leadership of the Directorate for Employment, Labour and Social Affairs (DELSA). The coordinated efforts enabled the IO to centralise health data collection that was previously conducted fragmentarily by multiple units and thus conduct more comprehensive comparisons on various aspects of health expenditure. For instance, the OECD’s analysis of health care systems started to include a range of policies, techniques, and models for health care system reforms (e.g. OECD Citation1992; Citation1994, Citation1995). In a study to compare seven European countries’ reform experiences from the mid-1980s to early 1990s, the comparison factors scaled up to include not only macroeconomic efficiency measured by health expenditure shares of GDP, but also microeconomic efficiency measured by health outcome, patient satisfaction, and costs of provision for the available share of GDP expended on health services (OECD Citation1992). Moreover, the IO began to host meetings with national health authorities and experts to further cultivate in-house health expertise. In this framework, it organised a high-level meeting with 12 OECD Health Ministers in 1994 for the discussion on health reforms and an ad hoc meeting of expertise in health statistics in 1996. This shift, from participating in external networks during the 1980s to building its own networks with experts from the OECD countries also indicates the OECD’s elaboration on expertisation.

On the other hand, the contents of the OECD’s health work presented enhanced coherence with the organisation-wide economic philosophy that championed neoliberal policies (Carroll and Kellow Citation2011, 239; Leimgruber and Schmelzer Citation2017, 39). Connecting the neoliberal principles to health expenditure, the IO naturalised its work in the health dimension of economism. As a result, the IO’s health work in this period shows the stark tendency to advocate for more extensive use of market-type mechanisms as an effective solution to restrain public expenditure. For instance, it argued for establishing and promoting competition between hospitals to create a market-type link between the hospitals and their access to public funds (OECD Citation1993). Picking up on the issue of the continuously rising health expenditures in the OECD countries, the IO also suggested further multiple cost-containment policy optionsbased on comparing national policy experiences (OECD Citation1994). The OECD’s activities in the economism-based health domain profited from the naturalisation straightforwardly, as the majority of the OECD countries were struggling to control spiraling health costs in the aging society (Woodward Citation2022, 44).

5.1.4. Early to mid-2000s: complement of the first step of mandate expansion

The efforts to expand into health policy from the 1970s to the 1990s resulted in the formal institutionalisation of the health activities in the IO’s mandate by the mid-2000s, which signifies the accomplishment of the first step. In this process, the OECD’s expertisation strategy was combined with the internal and external dynamics, namely, the changing architecture of global health governance, member states’ search for an alternative IO to transpose the delegation of health mandate, the OECD Secretary General’s mainstreaming of the health sector, and the high-quality health expertise the OECD steadily advanced in the previous decades. By the early 2000s, global health actors had increased and diversified exponentially, transforming global health governance from a WHO-centered space to a plural environment, where numerous initiatives began to operate involving emerging actors, such as the private sector, foundation, civil society as well as other IOs. Especially, the rapidly spreading AIDS pandemic and the mobilisation around the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) now afforded countries more varied options to channel their health-related goals, agendas, and resources (Lidén Citation2013; Pantzerhielm, Holzscheiter, and Bahr Citation2020). Simultaneously, the WHO was unprecedentedly accused of a lack of leadership to set and implement global health agendas (Lidén Citation2014). The WHO’s World Health Report 2000, in particular, caused a vehement reaction from several OECD countries because of the questionable measurements used in the report (Almeida et al. Citation2001; Carroll and Kellow Citation2011:247; Deacon and Kaasch Citation2008). As a result, OECD member states, specifically the USA and Australia with greater dissatisfaction, were looking for another IO to replace the work previously done by the WHO to analyse and compare domestic health care systems. At this point, the OECD was not only well equipped with its database that it had developed since the 1970s but also had the necessary expertise to undertake the work on health care systems in an improved way as wished by the OECD countries. For instance, the OECD’s publication on the topic System of Health Accounts in 2000 demonstrated the IO’s robust work on international comparisons of health data and economic analysis of health policy by outlining the methodologies for international health and health-related financial data across member states (OECD Citation2000). Importantly, the fact that the OECD’s expertise exclusively focused on the OECD countries may have been a decisive reason for the countries to choose the OECD over the WB. While both IOs became known for their expertise and their activities in the health domain of economism, the WB’s health work put stress on basic health in the context of reducing poverty in economically less advanced countries. At the same time, the OECD Secretary General of that time, Don Johnston, put health to the forefront of the IO’s agenda, encouraging the development of a proposal for a major health project within the OECD and promoting high-level support by working closely with the USA and Australia (Carroll and Kellow Citation2011:246; Johnston Citation2004).

Under this circumstance, the Health Project 2001-2004 was approved by the member states with the creation of the ad hoc Group on Health as the responsible body for it (OECD Citation2001). The project was financed by a contribution from the Secretary General’s Central Priorities Fund and a voluntary budget contributed by the member states. The three-year project focused on addressing the challenges to improving health systems’ performance, pursuing answers for what to be done to increase value for money and how to ensure the affordability of health spending in the future (OECD Citation2004a). Interestingly, in the final report of the project, the IO reflects on its role as to offer “a means for officials in member countries to learn from each other’s experience […] (and) to draw upon the best expertise available across OECD member countries” (OECD Citation2004b:3), which pertains to the strategy of technicalisation, presenting itself as a forum to facilitate exchanges.

The Health Project ran successfully, which resulted in the establishment of the Health Division in 2004. The Council’s view on the Group on Health’s performance was highly positive, assessing that “it [Group on Health] has succeeded in establishing itself and is performing well […] The Group’s mandate should therefore be renewed” (OECD Citation2006a:5). As a result, the Group on Health earned the status of a standing committee and subsequently transformed into the Health Committee in 2007 (OECD Citation2006b). Moreover, from 2005 onwards, the budget structure became more stabilised, as the IO’s regular budget started to finance part of the health work along with the voluntary contributions made by the member states, which has significantly increased since 2004 (OECD Citation2006a). Considering the institutionalisation of the health mandate in the OECD, it is fair to say that the OECD’s first step mandate expansion into the health policy sector was achieved by the mid-2000s.

5.2. Second step of mandate expansion within health policy

5.2.1. Mid- to late 2000s

While the IO’s topic diversification dispersed its previous focus on a few number of topics across multiple health issues starting from the mid-2000s, noteworthy attention was paid to the newly emerged topic of Health workforce. To include this topic in the health policy portfolio, the OECD first naturalised its relevance by framing the growing shortages of health professionals in high-income countries in this period as the OECD countries’ “looming crisis” (OECD Citation2008a). The IO then expertised its involvement in the topic area by presenting comparative and in-depth case studies based on its data collection that had been enriched and sophisticated both in quantity and quality. For instance, to identify the development of the health workforce status in the OECD countries, it juxtaposed data that showed multidimensional aspects of the changing size of the health workforce and policy responses, including age distribution of practicing health professionals, migration rate and average stay duration of foreign-born health professionals, and the ratio of foreign-trained professionals (OECD Citation2008b).

Moreover, the IO continued to specialise in the health dimension of economism. Adopting the market mechanism to the health workforce deficit in OECD countries, it focused on balancing the supply and demand in the global market for health workers, with fairly limited consideration of the impacts of health workforce migration in origin countries. While calling for a mutual responsibility between origin and destination countries in addressing the problems origin countries face, the OECD held the workforce drain as the logical result of market principles (OECD Citation2008a, 34–35). Along with this view, it presented a more nuanced one to attribute the accountability to origin countries, claiming that “push factors in origin countries also contribute to generating high levels of migration” (OECD Citation2008a, 9). Specifically pointing out less attractive working conditions for health workers, the OECD recommended that origin countries “improve working conditions and encourage better management of their workforce” (OECD Citation2008a, 57). As such, the IO’s market-oriented view accompanied the intensification of its involvement in the economic dimension of health.

5.2.2. The 2010s

The expansion practice in the 2010s shows a similar yet accelerated course compared to the mid to late 2000s in the spread of health concerns over a wide range of topics. Among diversified health issues in the OECD’s health policy portfolio, the three topics, Health care quality, Mental health and unemployment, and Health care systems reveal the IO’s more enhanced economist approach to health with the application of naturlisation and expertisation to increase the relevance within the field. First, the IO naturalised its special focus on Health care quality and Mental health and unemployment in the earlier half of the 2010s by linking its economic mandate to the repercussions of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. The crisis not only put pressure on the public budgets for health in most of the OECD countries but also caused a deterioration of the mental health in the population through the increased unemployment rates and job insecurity (OECD Citation2010; Citation2012; Citation2014). While stressing efficient health spending to respond to the financial pressure (OECD Citation2010), the OECD problematised the loss of potential labour supply and reduction in productivity at work due to the increasing mental illness in prospective and current working populations in the economic shock (OECD Citation2012). Second, the OECD advanced its relevance regarding the topic Health care systems by extending the scope and scale of analysis. Along with the globally rising importance of evidence-based policymaking (Littoz-Monnet Citation2017), the OECD further expanded its database, which enabled the IO’s analysis to incorporate more diverse aspects of measuring objects. The Health at a Glance, the OECD’s flagship publication series which began in 2001, is a good example that showcases this tendency. The scope of the indicators that the study applied introduced – new measurement areas with a list of multiple indicators to assess the performance of health systems in the 2010s, such as access to care, quality and outcomes of care, health workforce, and ageing and long-term care. At the same time, the initial indicators have been subdivided to measure additional aspects, as seen by the incorporation of avoidable mortality into general mortality measurement and the consideration of income level in the analysis of self-rated health status. Also, while the project was initiated to cover only OECD countries in 2001, it began to include comparable data for non-OECD member states and branched into additional region-focused versions for Asia-Pacific and European countries in 2010, and Latin America and the Caribbean in 2020.

Furthermore, some remarkable changes have been made in this period in the expertisation strategy by widening and deepening the cooperation nexus with central international and regional institutions. The collaboration with the European Commission (EC) is particularly extensive. Acknowledging the OECD’s added value in analysing and making health system information, expertise, and best practices accessible to policymakers (EC Citationn.d.), the EC commissioned joint work with the OECD. In this framework, Health at a Glance with an exclusive focus on Europe was launched in 2010 to bring out biannual reports. Implying the intensification of cooperation between the two institutions, an extension in the scope of research has been observed since 2018, as each report began to include two additional thematic chapters on current issues. In 2018, for instance, the special topics consisted of the economic impacts of mental illness and reducing waste in hospitals and pharmaceuticals, which dominantly reflected the OECD’s economist view (OECD Citation2018). Moreover, in 2017, the EC and the OECD launched an additional project to produce Country Health Profiles, which focuses on individual EU countries to consider national specificities to assess the effectiveness, accessibility, and resilience of their respective health systems. A joint arrangement between the OECD, the WHO, and the Eurostat, the statistical office of the EU, was also initiated during the 2010s, with the goal of improving health data comparability across the European countries. These joint projects reveal the EC’s perception of the OECD as an appropriate evaluator to find what “best” policies and practices should be for the EU countries.

The growing influence of the OECD’s health work was also visible in the G20-OECD nexus. The OECD accompanied the G20’s growth in the role as a global steering committee with a broad range of policy issues, as the Secretary General of that time, Angel Gurria, proactively used the G20 as the platform to advance the OECD agendas and shore up the IO’s position in the global governance architecture (Woodward Citation2022, 134–135). The OECD’s contribution to the G20 stretched into health work during the 2016 Hangzhou summit when the G20 called on the OECD, WHO, Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) to collectively develop evidence-based measures to prevent and mitigate antimicrobial resistance (G20 Citation2016). During the 2017 Hamburg Summit one year under the German Presidency, the G20 established the Health Working Group to share international agenda and issues, in which the OECD was counted as one of the relevant experts and invited to work further on antimicrobial resistance (G20 Citation2017). This partnership, which continues today, indicates the extension of the OECD’s relevance in the health sector beyond the European context into the economically advanced Global North countries.

5.2.3. Early 2020s: ongoing process of the second step of mandate expansion

Between 2020 and 2022, the world experienced uncertain and turbulent times due to the COVID-19 pandemic. During this period, the OECD’s organisation-wide focus was laid on responding to and recovering from the pandemic. The organisation-wide crisis management, in which all directorates analysed the impacts of the pandemic and recommended policy response options in all policy fields, naturalised and expertised the IO’s work in the health domain based on the security perspective (OECD Citation2020a). By mobilising the pre-existing expertise, the majority of the health topics were framed in the pandemic context to serve OECD countries (Meier and Martens Citation2024). For instance, the Country Health Profile series in 2021 included the analysis of the pandemic’s impacts on EU countries’ population health status and health system performance. The topic Health data Governance also shows this feature, which became one of the OECD’s health priorities in the late 2010s. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the IO legitimised its expansion of the work on health data governance into policies to prevent and respond to public health crises through health data by referring to the OECD Council’s RecommendationFootnote2 and employing the policy analysis it had continued over a few years (OECD Citation2020b; Citation2022).

Interestingly, the OECD’s engagement during the pandemic hinted at the potential augmentation of its approaches to health by re-involving itself in the security domain. Depicting the COVID-19 pandemic as “the most serious global pandemic crisis in a century” (OECD Citation2020b, 1), the IO framed the public health emergency as a significant threat to health care systems and emphasised to strengthen the ability of health care systems to prepare for, respond to, and adapt to shocks (OECD Citation2020b; Citation2020c; Citation2021). This was the first time during the process of the second step of expansion that the IO stretched into another health domain. Although the OECD had already worked in the security-based health area in the 1980s, its health work specialised in the domain of economism since then. Yet, while the approach during the 1980s was made in attempts to secure human health from radiation, the approach in the early 2020s pointed to secure health care systems. Accordingly, the IO’s major policy solutions produced during the crisis were associated with the policies that could enhance the capability of health care systems to react to the surge in health demand (OECD Citation2020b). Whereas the OECD’s health work during the pandemic implies the security-based perspective, whether it becomes an established part of the IO’s health mandate is not known yet.

Given the advancement made in the OECD’s relevance in the global health policy field, the OECD’s second step of mandate expansion within the health policy field has continued to progress after accomplishing the first step of expansion. On the one hand, the IO established its actorness in the economic domain of health and increased its relevance by improving expertise, with the extended scope and scale of analysis and data collection. On the other hand, collaboration with central international and regional networks – the G20 and the EC – has intensified, which indicates the growing recognition of the IO’s importance in the health sector. However, the collaborating partners were limited to the actors in the Global North. While such collaboration implies the appreciation of the OECD as one of the most important health actors by the global leaders in the Global North, that does not necessarily mean the equal weight of the IO to broader actors, including the Global South countries, NGOs, and private-public partnership institutions. In addition, the OECD lacks the experience in proactively launching a large-scale project involving broader external health actors and initiating joint efforts in achieving the goals it set. In other words, the IO’s activities do not pertain to a leading role in comprehensive global health governance. Therefore, the OECD’s second step mandate expansion is yet to be accomplished.

6. Conclusion

IOs expand their activities into and within new domains. The case of the OECD’s expansion in global health governance brings to light the practices of the two-step sequence of mandate expansion through employing organisation-specific strategies. The OECD primarily relied on the strategy of naturalisation and expertisation to enter and establish its position in the health policy field. On the one hand, the IO naturalised its relevance as a legitimate operator in the health sector by linking health concerns that acquired prominence in the global and regional contexts in each time period with the organisation’s primary mandate of fostering economic growth. The naturalisation strategy led the OECD to specialise in the health domain of economism as the IO adaptively applied the organisational economic philosophy, which has continuously evolved, to new health-related issues to expand its health policy portfolio. On the other hand, the practice of mobilising expertisation strategy differed in each phase of mandate expansion. In the first step of expansion, the OECD began to accumulate in-house expertise through extensive data collection. In the second step of expansion, the expertise built in the previous decades rationalised the organisation’s enlargement into new health topics. Moreover, the IO’s ever-elaborating database and analytical skills not only broadened the scope and scale of its health work but also shored up the IO’s position in global health governance along with the growing significance of evidence-based policy recommendations. The OECD’s expertise attracted collaboration with leading international and regional institutions, such as the G20 and EC. Interestingly, the OECD’s competence to sense the contextual opportunity was also important in mandate expansion. In the early to mid-2000s, when a majority of economically advanced countries expressed their dissatisfaction over the WHO’s work, the OECD presented its in-house expertise focusing on the OECD countries that included most of the discontented parties, successfully selling itself as a credible alternative actor to the WHO. Also, the IO picked up the topics that were the most pressing issues in the OECD countries in each decade, which derived their support for extending the list of health topics the IO deals with. Therefore, next to the appropriate choice of strategies, the wise use of contexts appears to have played a decisive role in mandate expansion.

The OECD’s position has been increasingly consolidated vis-à-vis other IOs in global health governance in the last two decades by specialising in the health domain of economism and targeting the OECD countries. The OECD demarcated itself from the WHO by approaching health from the economism-based view, as the WHO’s accentuated focus lies in the biomedical and human rights aspects of health. Against the WB, which is also known for the economism-based approach to health and health expertise, the OECD drew the boundary by differing the target group. While the WB primarily addresses health issues of low- to middle-income countries, the OECD exclusively focuses on its member states, namely high-income countries. Hence, the OECD’s selective commitment to its member states and particular health issues in the domain of economism has helped the IO to find its place in global health governance, defining the boundary from other IOs. However, it is also this exclusiveness that limits the IO from expanding its influence beyond the Global North-specific goals, agendas, and activities. As a result, the OECD lacks acknowledgment by broader health actors and thus comprehensive relevance in global health governance. This salience delays the accomplishment of the OECD’s unfinished work of the second step of mandate expansion.

In classifying IOs’ mandate expansion practices into two separate stages, this article contributes to the examination of IOs’ organisational change and strategic actorness. It sheds light on the underestimated phenomenon of IOs’ consolidation in a new policy domain after successfully entering the domain. Furthermore, this study uncovers the OECD’s activities in the health policy sector throughout the organisaion’s history, which has steadily gained relevance in the global health governance architecture. However, the findings in this article are subject to the limitation that the analysis is conducted based on publicly accessible documents as data. Hence, classified documents as well as undocumented data such as exchanges within the OECD and between it and other actors in global health governance are exempted from the analysis. In this sense, future studies can include more comprehensive forms of data to pinpoint the OECD’s mandate and position in global health governance more precisely. Moreover, future research might explore to which extent the OECD has contributed to consolidating the global health policy field, turning around the focus from the OECD’s growth within the field to the global health governance’s development with the OECD’s contribution.

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank Kerstin Martens, Matthias Kranke, and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments. I also thank Tim Frei and Duncan MacAulay for editing the draft. A previous version of this work has been presented at the Sektionstagung der DVPW-Sektion Internationale Beziehungen 2023 and at the BIGSSS colloquium. I thank the panels for their helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 However, not all IOs necessarily proceed with the second step of expansion. They can engage with the policy domain they entered only temporarily and leave out, or remain in the tasks they earned when they expanded into the domain.

2 In December 2016, the OECD Council adopted the Recommendation on Health Data Governance which calls for an integrated health information system to improve digital data governance, produce more timely and accurate health statistics, and facilitate health data usage (OECD Citation2016).

References

- Abbott, K., P. Genschel, D. Snidal, and B. Zangl. 2015. International Organizations as Orchestrators. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Abbott, K., J. Green, and R. Keohane. 2016. “Organizational Ecology and Institutional Change in Global Governance.” International Organization 70 (2): 247–277. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818315000338

- Almeida, C., P. Braveman, M. Gold, C. Szwarcwald, J. Ribeiro, A. Miglionico, J. Millar, et al. 2001. “Methodological Concerns and Recommendations on Policy Consequences of the World Health Report 2000.” The Lancet 357 (9269): 1692–1697. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04825-X

- Barnett, M., and L. Coleman. 2005. “Designing Police: Interpol and the Study of Change in International Organizations.” International Studies Quarterly 49 (4): 593–619. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2005.00380.x

- Barnett, M., and R. Duvall. 2005. Power in Global Governance. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Barnett, M., and M. Finnemore. 2004. Rule for the World: International Organizations in Global Politics. New York, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Béland, D., and M. A. Orenstein. 2013. “International Organizations as Policy Actors: An Ideational Approach.” Global Social Policy 13 (2): 125–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468018113484608

- Bradlow, D., and C. Grossman. 1995. “Limited Mandates and Intertwined Problems: A New Challenge for the World Bank and the IMF.” Human Rights Quarterly 17 (3): 411–442. https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.1995.0026

- Carroll, P., and A. Kellow. 2011. The OECD: A Study of Organisational Adaption. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Carroll, P., and A. Kellow. 2021. The OECD: A Decade of Transformation: 2011–2021. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Char, N. L., and Bela Csik. 1987. “Nuclear Power Development: History and Outlook.” International Atomic Energy Agency Bulletin 29 (3): 19–25.

- Deacon, B., and A. Kaasch. 2008. “The OECD’s Social and Health Policy: Neoliberal Stalking Horse or Balancer of Social and Economic Objectives?” In The OECD and Transnational Governance, edited by M. Rianne and S. McBride, 226–441. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Deeming, C., and P. Smyth. 2017. Reframing Global Social Policy: Social Investment for Sustainable and Inclusive Growth. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- De Francesco, F., and C. Radaelli. 2023. The Elgar Companion to the OECD. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- EC. n.d. “Public Health: State of Health in the EU.” https://health.ec.europa.eu/state-health-eu/overview_en#latest-updates.

- Freeman, R. 2006. “The Work the Document Does: Research, Policy, and Equity in Health.” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 31 (1): 51–70. https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-31-1-51

- G20. 2016. G20 Leaders’ Communique: Hangzhou Summit. https://www.og20germany.de/Content/DE/_Anlagen/G7_G20/2016-09-04-g20-kommunique-en_nn=2186554.html.

- G20. 2017. G20 Leaders’ Declaration: Shaping an Interconnected World. https://www.g20germany.de/Content/EN/_Anlagen/G20/G20-leaders-declaration_nn=2186554.html.

- Hall, N. 2013. “Moving Beyond its Mandate? UNHCR and Climate Change Displacement.” Journal of International Organizations Studies 4 (1): 91–108.

- Hall, N. 2015. “Money or Mandate? Why International Organizations Engage with the Climate Change Regime.” Global Environmental Politics 15 (2): 79–97. https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP_a_00299

- Hanrieder, T. 2015. “WHO Orchestrates?” In International Organizations as Orchestrators, edited by K. Abbott, P. Genschel, and B. Zangl, 191–213. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Hanrieder, T. 2018. “The Politics of International Organizations in Global Health.” In The Oxford Handbook of Global Health Politics, edited by C. McInnes, K. Lee, and J. Youde, 346–365. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Johnston, D. 2004. “Increasing Value for Money in Health Systems.” The European Journal of Health Economics 5 (2): 91–94.

- Kaasch, A. 2010. “A New Global Health Actor? The OECD’s Careful Guidance of National Health Care Systems.” In Mechanisms of OECD Governance: International Incentives for National Policymaking?, edited by K. Martens, and A. P. Jakobi, 180–197. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kaasch, A. 2021. “Characterizing Global Health Governance by International Organizations: Is There an Ante- and Post-COVID-19 Architecture?” In International Organizations in Global Social Governance, edited by K. Martens, D. Niemann, and A. Kaasch, 233–254. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kallo, J. 2021. “The Epistemic Culture of the OECD and Its Agenda for Higher Education.” Journal of Education Policy 36 (6): 779–800. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2020.1745897

- Kranke, M. 2022. “Exclusive Expertise: The Boundary Work of International Organizations.” Review of International Political Economy 29 (2): 453–476. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1784774

- Kreuder-Sonnen, C., and P. Tantow. 2022. “Crisis and Change at IOM: Critical Juncture, Precedents, and Task Expansion.” In IOM Unbound?: Obligations and Accountability of the International Organizations for Migration in an Era of Expansion, edited by M. Bradely, C. Costello, and A. Sherwood, 187–212. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Lee, K. 2009. “Understanding of Global Health Governance: The Contested Landscape.” In Global Health Governance: Crisis, Institutions and Political Economy, edited by A. Kay, and O. Williams, 27–41. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Leimgruber, M., and M. Schmelzer. 2017. The OECD and the International Political Economy Since 1948. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lenz, T., B. Ceka, L. Hooghe, and G. Marks. 2022. “Discovering Cooperation: Endogenous Change in International Organizations.” The Review of International Organizations 18: 631–666. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-022-09482-0

- Lesage, D., and T. Van de Graaf. 2013. “Thriving in Complexity? The OECD System’s Role in Energy and Taxation.” Global Governance 19: 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-01901007

- Lidén, J. 2013. “The Grand Decade for Global Health. 1998–2008” (Centre on Global Health Security Working Group Papers – Working Group on Governance, Paper No.2). April. https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/public/Research/Global%20Health/0413_who.pdf.

- Lidén, J. 2014. “The World Health Organization and Global Health Governance: Post-1990.” Public Health 128 (2): 141–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2013.08.008

- Littoz-Monnet, A. 2017. The Politics of Expertise in International Organizations: How International Bureaucracies Produce and Mobilize Knowledge. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Littoz-Monnet, A. 2021. “Expanding Without Much Ado. International Bureaucratic Expansion Tactics in the Case of Bioethics.” Journal of European Public Policy 28 (6): 858–879. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1781231

- Mahon, R. 2019. “Broadening the Social Investment Agenda: The OECD, the World Bank and Inclusive Growth.” Global Social Policy 19 (1-2): 121–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468018119826404

- Marcussen, M., and J. Trondal. 2011. “The OECD Civil Servant: Caught Between Scylla and Charybdis.” Review of International Political Economy 18 (5): 592–621. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2011.603665

- Marmor, Ted, Richard Freeman, and Kieke Okma. 2005. “Comparative Perspectives and Policy Learning in the World of Health Care.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 7 (4): 331–348.

- Martens, K., and A. Jakobi. 2010. Mechanisms of OECD Governance: International Incentives for National Policymaking? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- McInnes, C. 2018. “Global Health Governance.” In The Oxford Handbook of Global Health Politics, edited by C. McInnes, K. Lee, and J. Youde, 264–279. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Meier, S., and K. Martens. 2024. “A Global Crisis Manager During the COVID-19 Pandemic? The OECD and Health Governance.” Frontiers in Political Science 6: 1332684. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2024.1332684

- Niemann, D., D. Krogmann, and K. Martens. 2023. “Torn Into the Abyss? How Subpopulations of International Orgnizations in Climate, Education, and Health Policy Evolve in Times of a Declining Liberal International Order.” Global Governance 29: 271–294. https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-02903004

- Niemann, D., and K. Martens. 2018. “Soft Governance by Hard Fact? The OECD as a Knowledge Broker in Education Policy.” Global Social Policy 18 (3): 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468018118794076

- OECD. 1960. “Convention on the OECD.” https://www.oecd.org/about/document/oecd-convention.htm#Text.

- OECD. 1973. The OECD Social Indicator Development Programme: List of Social Concerns Common to Most OECD Countries. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 1977a. Health, Higher Education and the Community: Towards a Regional Health University. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 1977b. Public Expenditure on Health (OECD Studies in Resource Allocation, Paper No.4). OECD.

- OECD. 1978. Planning for Growing Populations. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 1983. The World of Appropriate Technology: A Quantitative Analysis. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 1992. The Reform of Health Care: A Comparative Analysis of Seven OECD Countries. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 1993. “Market Emulation in Hospitals” (Occasional Papers on Public Management – Market-type Mechanisms Series, Paper No.7). OECD.

- OECD. 1994. Health: Quality and Choice. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 1995. The Future of Health Care Systems. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 2000. A System of Health Accounts. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 2001. Summary Record of the 1008th Session (C/M(2001)14/PROV).

- OECD. 2004a. Towards High-Performing Health Systems. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 2004b. Towards High-Performing Health Systems: Policy Studies. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 2006a. In-Depth Evaluation of the Group on Health (C/ESG(2006)5/REV1).

- OECD. 2006b. Summary Record of the 1146th Session (C/M(2006)20/PROV).

- OECD. 2008a. The Looming Crisis in the Health Workforce: How Can OECD Countries Respond?. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 2008b. “International Mobility of Health Professionals and Health Workforce Management in Canada: Myths and Realities” (OECD Health Working Papers, Paper No.40). https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/international-mobility-of-health-professionals-and-health-workforce-management-in-canada_228478636331.

- OECD. 2010. Improving Value in Health Care: Measuring Quality. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 2012. Sick on the Job? Myths and Realities About Mental Health and Work. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- OECD. 2014. Making Mental Health Count: The Social and Economic Costs of Neglecting Mental Health Care. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- OECD. 2016. Recommendation of the Council on Health Data Governance (OECD/LEGAL/0433).

- OECD. 2018. Health at a Glance: Europe 2018: State of Health in the EU Cycle. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- OECD. 2020b. Beyond Containment: Health Systems Responses to COVID-19 in the OECD (OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19)). https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/beyond-containment-health-systems-responses-to-covid-19-in-the-oecd-6ab740c0/.

- OECD. 2020c. Realising the Potential of Primary Health Care. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- OECD. 2021. “Strengthening the Frontline: How Primary Health Care Helps Health Systems Adapt during the COVID-19 Pandemic (OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19)).” https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/strengthening-the-frontline-how-primary-health-care-helps-health-systems-adapt-during-the-covid-19-pandemic_9a5ae6da-en.

- OECD. 2022. Health Data Governance for the Digital Age: Implementing the OECD Recommendation on Health Data Governance. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- OECD/NEA. 1984a. International Comparison Study on Reactor Accident Consequences Modeling. Paris: OECD.

- OECD/NEA. 1984b. Radiation Protection: The NEA’s Contribution. Paris: OECD.

- OECD/NEA. 1985. Concepts of Collective Dose in Radiological Protection. Paris: OECD.

- OECD/NEA. 1987. Proceedings of an NEA Workshop on Epidemiology and Radiation Protection. Paris: OECD.

- OECD/NEA. n.d. “History of the NEA.” https://www.oecd-nea.org/jcms/pl_40042/history-of-the-nea.

- OEDC. 2020a. Joint Actions to Win the War. https://www.oecd.org/washington/newsarchive/covid-19jointactionstowinthewar.htm.

- Pantzerhielm, L., A. Holzscheiter, and T. Bahr. 2020. “Power in Relations of International Organisations: The Productive Effects of ‘Good’ Governance Norms in Global Health.” Review of International Studies 46 (3): 395–414. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210520000145

- Rautalin, M., J. Syväterä, and E. Vento. 2021. “International Organizations Establishing Their Scientific Authority: Periodizing the Legitimation of Policy Advice by the OECD.” International Sociology 36 (1): 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580920947871

- Roberts, M., B. Stewart, and D. Tingley. 2018. “Stm: R Package for Structural Topic Models.” Journal of Statistical Software 91 (2): 1–40.

- Ruger, J. 2005. “The Changing Role of the World Bank in Global Health.” American Journal of Public Health 95 (1): 60–70. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.042002

- Schemeil, Y. 2013. “Bringing International Organization In: Global Institutions as Adaptive Hybrids.” Organization Studies 34 (2): 219–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840612473551

- Sellar, S., and B. Lingard. 2013. “The OECD and Global Governance in Education.” Journal of Education Policy 28 (5): 710–725. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2013.779791

- Trondal, J. 2016. “Advances to the Study of International Public Administration.” Journal of European Public Policy 23 (7): 1097–1108. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1168982

- Trondal, J., M. Marcussen, T. Larsson, and F. Veggeland. 2010. Unpacking International Organisations: The Dynamics of Compound Bureaucracies. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Vetterlein, A., and M. Moschella. 2014. “International Organizations and Organizational Fields: Explaining Policy Change in the IMF.” European Political Science Review 6 (1): 143–165. https://doi.org/10.1017/S175577391200029X

- Woodward, R. 2022. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). 2nd ed. London: Routledge.