ABSTRACT

Central banking as an avenue of research has been of interest to scholars from International Political Economy (IPE) and Public Policy and Administration (PPA) disciplines. Nevertheless, there is very little dialogue between these two perspectives to bridge macro, meso, micro-level analyses and examine the reciprocal relationship between the global and domestic political economy context and monetary policy conduct. This article investigates the Turkish experience to bridge IPE and PPA scholarship on central banking in emerging economies. In doing so, we adopt an analytic eclectic approach combining multiple structural, institutional, and agential causal explanations with particular reference to the Structure, Institution, and Agency (SIA) theoretical framework. This is because analytic eclecticism complements, speaks to, and selectively incorporates theoretical approaches such as the New Independence Approach (NIA) of IPE and institutional and ideational PPA approaches. Drawing on the empirical context of the historical evolution of the Turkish political economy, we explore domestic and international interactions among micro, meso, and macro levels that shape central banking behavior. Our analysis also reveals how global dynamics are translated into domestic policy choices and how particular ideas influence the policymaking process. The analysis underscores the constraining and enabling influence of international dynamics, politics of ideas on emerging economy central banking, and the essential role individual and organizational agency play in the policymaking process.

Introduction

Central banks operate under significant uncertainty (Katzenstein & Nelson, Citation2013; Nelson & Katzenstein, Citation2014). Since the onset of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the cycles of capital flows emanating from the unconventional policies of the Federal Reserve (Fed), European Central Bank, Bank of England, and Bank of Japan have amplified uncertainties for emerging economy central banks (Ahmed & Zlate, Citation2014; Bauerle Danzman, Winecoff, & Oatley, Citation2017; Borio & Disyatat, Citation2010). With increasing volatility and risks in managing these capital flows, emerging economies devised several measures, including unconventional monetary policy tools (Gallagher, Citation2014; Yağcı, Citation2017). Because of the complex interdependence in the international financial system, uncertainties create an unlevel playing field for emerging economy central banks when compared to their counterparts in advanced industrialized countries; these uncertainties also expose the asymmetric power relations present in global finance (Bauerle Danzman et al., Citation2017; Farrell & Newman, Citation2016; Kahler, Citation2016; Oatley, Citation2019).

Since the GFC stemmed from advanced industrialized countries and because the central banks in these countries have been at the forefront of responding to the crisis, there has been much less academic focus on central banking in emerging economies and the global, domestic political economy context within which they operate (Yağcı, Citation2020). It is critical to examine the emerging economy central banks in order to reflect on how the complex interdependence in the global financial system influences their policy choices (Farrell & Newman, Citation2016; Kahler, Citation2016; Oatley, Citation2019), how ideational influences are translated into domestic practices (Ban, Citation2016; Campbell, Citation1998; Campbell & Kaj Pedersen, Citation2001), and how a global comprehension of central banking enhances an understanding of the contextual forces in play (Yağcı, Citation2020).

In this article, we examine the historical evolution of the Turkish political economy and the central bank (The Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey – CBRT), as well as how the CBRT's policy choices are influenced by the interaction of global and domestic structural, institutional, and agential factors. The Turkish case is illustrative in several respects, as the Turkish economic development experience has been prone to global shifts in the international system, and CBRT activities reflect the interactions between global and domestic forces (Bakır, Citation2007). This allows for an examination of how emerging economy central banks cope with evolving complex interdependence in the international financial system. Accordingly, four main structural factors shaped the context within which institutions and actors related to central banking are embedded in Turkey. First, capital account liberalization in 1989 made central banking an increasingly esoteric (i.e. technical and expert-led) issue. Second, the Turkish financial crisis in 2001 opened a structural-level window of opportunity at the national level for institutional/policy entrepreneurship, which resulted in legal reform granting formal independence to the CBRT. Third, the 2008 GFC opened a structural-level window of opportunity at a systemic level for the institutional/policy entrepreneurship whereby a price stability objective accompanied the financial stability pursuit. Finally, the fourth factor is the formalization of the de facto presidential system of government with a tradition of strong leadership following the 2018 presidential and parliamentary elections whereby presidential decrees (as key formal institutions) and the President’s ideas and preferences informed the central bank's decisions.

Our analysis is informed by the analytic eclectic Structure, Institution, and Agency (SIA) framework (Bakır, Citation2013, Citation2017) because it accounts for various causal factors that matter most and combines various political economy explanations and public policy scholarship with analytic eclecticism.Footnote1 In this respect, we focus on how structural (i.e. broader temporal, material, and cultural contexts within which institutions and agents are embedded), institutional (i.e. formal and informal rules that inform agential action), actors (i.e. individuals, organizations, and collective entities) interact whereby central banking decisions and actions are shaped. We argue that central banking actions and outcomes are the products of multiple enabling conditions that facilitate intentional agential action through motivating and empowering the CBRT to deliver the desired or preferred policy and/or institutional outcomes. Enabling conditions arise from multiple structural, institutional, and agential levels, affecting purposeful agential actions through empowering the actor’s access to and mobilization of various resources (Bakır, Citation2013; Battilana, Leca, & Boxenbaum, Citation2009).

Our analysis of the CBRT highlights both the global and domestic political economy context within which emerging economy central banks are embedded while examining the policymaking process that links inputs, outputs, and outcomes (Guidi, Guardiancich, & Levi‐Faur, Citation2020). Our analytic eclectic perspective benefits from the New Interdependence Approach (NIA) of IPE (Farrell & Newman, Citation2016) and the politics of ideas perspective in Public Policy and Administration (PPA) (Beland Citation2019; Quirk, Citation1988). In our analysis of the historical evolution of the Turkish political economy and CBRT, we focus on three critical episodes of institutional/policy change: central bank legal independence, the CBRT's pursuit of financial stability following the GFC, and the state of central banking after the shift to the presidential system. In our quest to bridge IPE and PPA scholarship, we underline the crucial role played by individual and organizational agency in the form of institutional/policy entrepreneurship leading to institutional/policy change.Footnote2

While there have been calls to bridge different levels of analysis in PPA (Roberts, Citation2020), neglect of the international dimension risks missing crucial influences in the policymaking process (Beland Citation2009). Moreover, PPA scholars have pointed to the neglect of macroeconomic issues in their field, calling for a redefinition of PPA’s intellectual boundaries (Han, Xiong, & Frank, Citation2020). PPA research also recognizes the need to develop and test theories in developing countries in order to inform a better understanding of PPA (Bertelli, Hassan, Honig, Rogger, & Williams, Citation2020). We believe that bridging IPE and PPA scholarship while focusing on the evolution of the Turkish political economy and central bank behavior in order to account for complex causal structural, institutional, and agential explanations addresses the gaps identified in these studies.

This article is organized as follows: Section two examines the evolving IPE and PPA scholarship on central banking and recommends a path with which to bridge them; section three focuses on the evolution of the Turkish political economy, with subsections on central bank independence, the pursuit of financial stability after the GFC, and the state of central banking after a shift to the presidential system; section four discusses this study’s contributions and recommends more engagement with analytic eclecticism in social science research.

Evolving IPE and PPA Research on central banking

IPE scholarship offers pertinent insight into the international financial system within which emerging economy central banks struggle to find policy space. The international movement of capital and its structural influence (Abdelal, Citation2007; Andrews, Citation1994; Gill & Law, Citation1989), the cycles of international capital flows and the vulnerability it causes for emerging economies (Bauerle Danzman et al., Citation2017), international financial regulation (Singer, Citation2007), the structural power of the United States in exporting its problems to the rest of the world through the Fed’s actions (Schwartz, Citation2016), and the dependence of central banks on the Fed's swap arrangements to ease liquidity shortages (Sahasrabuddhe, Citation2019) are important examples. Chaudoin and Milner (Citation2017) underline that the most potent systemic pressures in the international monetary system come from the distribution of capabilities in finance (e.g. US hegemony), capital flow pressures, and the power of transnational capital. Thus, emerging economy central banks are forced to operate and find policy space under these systemic pressures.

There are several invaluable studies on the political economy of central banking in emerging economies (Dönmez & Zemandl, Citation2019; Gallagher, Citation2014; Hamilton-Hart, Citation2002; Johnson, Citation2016; Maxfield, Citation1994; Takagi, Citation2016; Zayim, Citation2020; Zhang, Citation2005). These studies make critical contributions to the literature by underlining the interactions between domestic and international forces, and highligting these interactions constrain or enable central banking activity in emerging economies.Footnote3 However, because these studies exclude discussion of the policymaking process, they overlook the political struggles, tensions, and ideational forces influential in it. As such, our knowledge of how international forces are translated into specific policy choices (with attention to the influence of key actors, their ideas, tensions, and contestations involved in the policymaking process) is limited.

Public policies can be defined as government actions that represent previously agreed responses to specified circumstances, and governments can be assumed to design public policies to extend the public good (Mintrom & Williams, Citation2012, p. 4). Central banks are political organizations (Binder & Spindel, Citation2017, Citation2018), and their decisions have a substantial impact on overall social and economic well-being, with distributional consequences (Jacobs & King, Citation2016). In other words, central banks are not neutral when it comes to the social and economic implications of their policies (Adolph, Citation2018). Thus, situating central banking and monetary policy within a broader PPA framework allows for scrutiny of why and how central banks make specific policy decisions, as well as of these decisions' ensuing consequences for society. The PPA perspective offers some tools to explore various processes and dimensions of policymaking.

In PPA research, scholars mostly focus on the policy process in order to examine consecutive stages of policymaking. The successive stages and continuous cycle of the policymaking process are generally conceptualized as agenda-setting, policy formulation, decision-making, policy implementation, and policy evaluation (Howlett & Giest, Citation2012). This policy process framework helps to analyze the temporal and spatial dimension of policymaking as an analytical tool by identifying the key actors and examining the evolution of a policy from its inception. The stages approach in policymaking recognizes that overreliance on policy output may not capture the tensions, struggles, and interactions involved in the policymaking process; therefore, a closer examination of these dynamics may reveal why and how policy change occurs. John (Citation2018) posits that integrating political economy studies with a more sophisticated understanding of the stages of policy processes and the political economy of public policy perspective would open new research avenues for scholars. Beland (Citation2019, p. 23–24) maintains that theories of the policy process are unclear about their explanatory logic, do not define the role of ideational processes as explanatory factors, and pay limited attention to the influence of political institutions, policy legacies, transnational actors, and their interaction with domestic actors and institutions. Theories on policy change and policy process might be integrated with IPE research in order to examine how global influences are translated into local practices and policies (Hay, Citation2006; Perl, Citation2012).

PPA scholars apply the Principal-Agent Theory (PAT) to answer questions on the extent of control the principal (elected officials) has over the agent (bureaucrats), how the bureaucratic moral hazard based on informational asymmetry can be prevented, and how the principle can take advantage of its formal authority to impose incentives on the agent (Miller, Citation2005). Nevertheless, PAT studies neglect the political moral hazard problem and omit that public agency autonomy can ensure credible commitment with checks and balances on the executive (Corder, Citation2014; Knott & Miller, Citation2006, Citation2008; Miller & Whitford, Citation2016). The focus on the United States and its domestic politics in these studies necessitate investigation of the interaction between international and domestic forces that shape central bank independence in emerging economies, with consequences on the credible commitment of monetary policy (North & Weingast, Citation1989).

How might international pressures and the domestic policymaking process be integrated in discussion of emerging economies? With its interest-based mechanistic explanations, analysis of domestic politics in isolation from international pressures, and aim for empirical regularities without concern for contextualizing action, Open-Economy Politics (OEP) cannot explain the behavior of emerging economy central banks (Nelson, Citation2020; Oatley, Citation2011). In OEP, applying the assumptions of micro or macroeconomics to IPE scholarship has resulted in disregard of the social structure of the global economy (Samman & Seabrooke, Citation2016).

The New Interdependence Approach (NIA) aims to overcome these limitations by using a structural explanation to illustrate complex interdependence, suggesting that globalization is an endogenous process whereby global rules and principles of markets clash, resulting in rule overlap (Farrell & Newman, Citation2016). These global interactions have implications for domestic institutions and policymaking that can constrain or enable agential action in a policy space by offering opportunity structures for collective actors. In addition, NIA recognizes the power asymmetries resulting from rule overlap and opportunity structures so that not all entities take advantage of evolving globalization patterns. NIA also draws attention to the agency in a complex global governance that behaves strategically in response to global and domestic pressures (Kahler, Citation2016). Studying the agency of emerging economy central banks with the NIA framework explains rule overlaps, opportunity structures, and power asymmetries at both the global and domestic levels. In this respect, diffusion studies offer explanations for how the complex interdependence and transnational processes are reflected in domestic institutions and policymaking.

Diffusion studies view policy choices in different countries as interdependent and subject to international influence. Relatedly, diffusion research identifies four fundamental mechanisms through which interdependent decision-making occurs: coercion, competition, learning, and emulation (Simmons, Dobbin, & Garrett, Citation2006). Research on the diffusion of central bank independence norm finds that states are subject to international pressures. As a result, they experience a reconfiguration or reorganization toward more technocratic management to legitimize their activities (Polillo & Guillén, Citation2005). Nevertheless, many diffusion studies view states as primary actors in their analysis and do not allow individual or organizational agency to influence institutional/policy change (Samman & Seabrooke, Citation2016).

Several PPA scholars highlight the crucial role individual and organizational agency plays in policymaking and the necessity of examining the context within which they are embedded (Bertelli, Citation2012; Hammond & Knott, Citation1999; Miller, Citation1992). Accordingly, we accentuate the relevance of individual and organizational agency leading to institutional/policy change in consideration of the global and domestic political economy context within which they are embedded. In other words, the agency in our explanation is not only crucial for institutional/policy change but also context-dependent (Bakır, Citation2009; Bakır and Jarvis Citation2017; Battilana et al., Citation2009; Kingdon, Citation1984); this distinguishes our investigation from other agency-based studies.

The trajectory of the Turkish political economy and resulting central banking practices highlight the role of key individuals and organizations in the policymaking process. Key individual actors indicated in the analysis are Kemal Derviş, a minister who played a critical role in restructuring the Turkish political economy and central bank independence decision in the aftermath of the 2000–2001 twin economic and financial crises, and Erdem Başçı, the Governor of the CBRT during the GFC. Başçı formulated and implemented unconventional monetary policy measures in order to tame the negative impact of surging capital flows, gaining political support for the pursuit of financial stability from the Turkish Treasury. The CBRT's organizational agency has been essential to the pursuit of financial stability and the implementation of macroprudential monetary policy measures since 2010. The key individual actors underline the crucial role political support plays in public organizations’ activities, as well as how these individuals acted as institutional/policy entrepreneurs for institutional/policy change.

In PPA scholarship, institutional and ideational analysis helps to examine the preferences and interests of key policy actors, the role of ideas across the policy cycle, asymmetrical power relations among policy actors, and the effect of these relations on the politics of ideas (Béland, Citation2019; Derthick & Quirk, Citation1985). Similarly, extensive IPE scholarship recognizes that, in addition to structural, institutional, or interest-based factors, ideas are consequential for social, political, and economic phenomena (Blyth, Citation2002; Campbell, Citation1998; Hall, Citation1989; Levingston, Citation2020; Nelson, Citation2017). The Turkish case highlights the critical role powerful politicians’ ideas play in constraining central bank policy space and reducing credible commitment (North & Weingast, Citation1989). It demonstrates that President Erdoğan’s vocal opposition to high interest rates because of his belief that they cause high inflation has significantly constrained the CBRT’s policy space and has resulted in political contestations and tensions in the policymaking process. These constraints have intensified after the shift from a parliamentary to a presidential system in Turkey.

The political economy of central banking in Turkey: international influences and domestic policy choices

The role of structural, institutional, and agential-level enabling conditions on 2001 CBRT legal reform

Liberalization of the capital account in 1989 and the establishment of the domestic debt market created a conducive environment for a hot money policy (Ersel, Citation1996). High real interest rates were offered so that government securities could attract short-term, speculative, and unproductive capital inflows (Gemici, Citation2012). The weak coalition governments during the 1990s increasingly relied on the CBRT to finance budget deficits through inflationary short-term advances to the Treasury (i.e. the CBRT’s monetization of public debt). Nevertheless, the CBRT, along with the Turkish Treasury, increasingly moved to the center of macroeconomic policymaking as monetary governance increasingly became a technical issue in the deregulated Turkish financial market (Bakır, Citation2007, p. 29–39).

As a result of the politicization of bank lending, the populist economic cycles, the democratic deficit, and the unaccountable and non-transparent nature of public administration, problems in fiscal policy were amplified, and the Turkish economy experienced the persistence of high public debt, high inflation, and interest rates during the 1990s (Alper & Öniş, Citation2003; Bakır & Öniş, Citation2010). This resulted in severe economic and financial crises in the 1990s and early 2000s. In the post-crisis context, the policy entrepreneurship process was reflected primarily in granting legal independence to the CBRT (Bakır, Citation2009). From the SIA perspective, the 2001 Turkish financial crisis opened a structural window of opportunity for legal reform in central banking. This was because political actors and prevailing policy ideas lost their legitimacy in the crisis environment. In this context, Kemal Derviş, then Vice President for Poverty Reduction and Economic Management at the World Bank, was appointed Minister of State for Economic Affairs in March 2001. The homegrown 2001 financial and economic crisis in Turkey played a pivotal role in enabling Derviş to undertake an individual, institutional/policy entrepreneur role in the microeconomic reform (Bakır, Citation2009). At the structural material level, a financial crisis resulted in currency devaluation, bank collapses, and sharp economic contraction. Following the crisis, there were also radical political implications in the form of a legitimacy crisis in Turkish politics, involving strong public distrust and anger at politicians within the parliament. This was the principal structural enabling condition that opened a space for agential action. Further, one policy impact was the loss of legitimacy in the then-existing programmatic policy ideas and their formal institutional arrangements in the realm of macroeconomic governance.

At the institutional level, the failures of existing ideas, practices, and formal arrangements to offer solutions to existing problems such as high inflation and unsustainable debt dynamics were the critical institutional level conditions that opened an enabling space for agential action. Consequently, the government lost its domestic and international credibility. In the crisis environment, Derviş was perceived by the domestic policy community and network as a nonpartisan, international technocrat. In short, the financial crisis and institutional failures made up the material structural context that offered enabling conditions for Derviş. In addition, the availability of programmatic monetary and fiscal policy ideas of the neoliberal paradigm sponsored by the IMF (e.g. central bank independence, budget discipline, and public debt management), as well as sound governance principles (e.g. transparent and accountable public sector management) in the public sector informed by the New Public Management perspective, enabled Derviş’s policy/institutional entrepreneurship.

Regarding organizational-level enabling conditions, The Ministry of Economy carried a vital social status: It had control over the central macroeconomic bureaucracies- namely the central bank, the financial regulator, the Treasury, the bank resolution authority, and the capital markets board (Bakır, Citation2009). Thus, it was at the center of the macroeconomic policy network and carried the highest organizational status in the public sector, especially during the crisis era. Furthermore, Derviş entered into a well-prepared economic bureaucracy, since the underlying technical studies for establishing the Banking Regulation and Supervision Agency (BRSA) and law granting independence to the CBRT had already been introduced by economic bureaucracy before the 2001 crisis (Kutlay, Citation2019, p. 88). The CBRT drafted a central banking law between 1996–2000 that included four radical provisions toward CBRT independence: ‘(1) price stability is stated as a primary objective, (2) short-term interest rates are to be determined by the bank independently of the government, (3) the bank is not to lend to the public sector under any conditions, and (4) the government cannot give orders to the bank under any condition’ (Bakır, Citation2009, p. 584–585). Thus, Derviş was part of a very well-prepared economic bureaucracy conducive to the implementation of reforms that facilitated the transition to a new economic program.

Regarding the individual-level enabling conditions, Derviş had specific resources and capabilities that enabled him to play the role of policy entrepreneur (e.g. setting the governmental agenda) and institutional entrepreneur (e.g. steering the institutional change process). At the agency level, Derviş’s social position was not limited to his formal position as a resourceful new economy minister (Bakır, Citation2009). As an academic, economist, and bureaucrat during his 24-year career at the World Bank, he was also a member of the transnational epistemic community, that shared the basic programmatic policy ideas, beliefs, values, and norms of liberal economic ideas. Further, he had strong social ties with elite decision-makers, from the U.S. Treasury, World Bank, and International Monetary Fund (IMF) to Turkish politicians and bureaucrats. As a strategic actor, he held the key to the government’s access to IMF lending. Derviş was not only a former academic who published influential policy-relevant academic articles but was also equipped with specific policy prescriptions to address economic problems.

Thus, his multiple professional identities as a former advisor to the Turkish Prime Minister, an academic economist at Princeton University with a Ph.D. from LSE, gave him legitimacy and knowledge authority. His professional skills as a framer enabled him to legitimize programmatic policy ideas in various constituencies. His role as a mediator between domestic and transnational policy communities gave him access to and control over various resources. As an institutional entrepreneur, his multiple identities allowed him to operate in different ideational realms and across domestic and transnational policy networks. He mobilized various ideas and discourses to build coalitions, resolve conflicts, and steer the policy network towards institutional/policy changes (Bakır, Citation2009).

Influenced by these enabling conditions, one of the most important institutional changes under the IMF program was in the CBRT Law 1211, amended by Law 4651 on 25 April 2001; the law granted the CBRT legal independence with a single mandate on achieving and maintaining price stability. Derviş’s institutional/policy entrepreneurship was critical in giving legal independence to the CBRT, since he could utilize the IMF for coercion and quick implementation of the reform program and could successfully negotiate with them for amendments in critical policy decisions (Bakır, Citation2009, p. 587–91). For instance, when the IMF insisted on the establishment of a currency board, Derviş rejected the proposal, using experts' views in his favor during IMF negotiations (Bakır, Citation2009, p. 591). Consequently, an imperfect free-floating exchange regime was accepted with CBRT interventions in the market, despite the IMF's objections. This decision helped to avoid another rapid devaluation of the Turkish lira after the 2001 crisis (Derviş, Citation2005, p. 91). Derviş also persuaded the IMF to temporarily make an exception for CBRT funding to the Turkish Treasury, a decision that facilitated government expenditures on insolvent banks; in addition, he influenced the IMF to accept a feasible inflation target of 35% for 2001, instead of the proposed 20% (Bakır, Citation2009, p. 591).

In terms of diffusion, the implementation of central bank independence reform can be explained by both learning by the economic bureaucracy and the coercive influence of the IMF program facilitated by the institutional/policy entrepreneurship of Kemal Derviş, who set governmental and public agendas and steered their implementation in the various stages of public policymaking. Thus, Derviş performed the combined roles of institutional/policy entrepreneur.

Structural, institutional, and agential-level enabling conditions that informed the financial stability turn and unconventional monetary policy measures of the CBRT

After the CBRT gained legal independence, achievement and maintenance of price stability became its principal mandate, and the inflation rate was reduced to single digits for the first time in several decades. However, at the structural level, the GFC opened a structural window of opportunity for a paradigm change in central banking at the national and international levels, indicating that price stability alone could not ensure financial stability (Baker, Citation2013; Galati & Moessner, Citation2013). At the institutional level, programmatic macroprudential policy ideas emerged as one of the main factors that informed worldwide central banking practices (Baker, Citation2013). Accordingly, systemic stability has been a de facto agenda item for the CBRT in the post-GFC period.

The CBRT initiated its active pursuit of financial stability with a surge of capital flows occurring because of the Fed’s quantitative easing policy, leading to the overheating of the Turkish economy (Kara, Citation2016). Subsequently, the Turkish economy witnessed several challenges: the private credit growth rate reached 40%, the Turkish lira appreciated rapidly, the current account deficit deteriorated, and short-term ‘hot’ portfolio flows were used at high proportions to finance it (Kara, Citation2016, p. 86). The CBRT’s early engagement with emerging risks underlines its leading role in all the policy stages of the macroprudential turn in Turkey.

As an institutional/policy entrepreneur, the Governor of the CBRT, Erdem Başçı, facilitated the CBRT’s active role by coupling problems (macro-financial risks) with solutions (macroprudential regulation) and politics (a sympathetic economy minister who shaped governmental agenda). Specifically, in the governmental agenda-setting stage, starting from 2010, the CBRT was the only public organization to draw attention to global imbalances and macro-financial risks in the Turkish economy; in the policy formulation stage, the CBRT devised unconventional monetary tools of the reserve option mechanism and asymmetric interest rate corridorFootnote4; in the policy implementation stage, the CBRT was compelled to take action with unconventional monetary policy tools and other measures because of inaction in other public entities; in the policy evaluation stage, the CBRT recognized that its policies needed to be supported by BRSA measures so that the CBRT (led by Governor Başçı) could become instrumental in the establishment of the Financial Stability Committee (FSC), leading to BRSA's implementation of financial stability-oriented measures (Yağcı, Citation2017). The CBRT's active pursuit of financial stability also underlines its organizational learning or organizational policy capacity (Bakır and Çoban Citation2019) in the policymaking process, which emanates from a combination of factors such as organizational capability, clear policy goals and strategy, feedback mechanisms, learning-friendly environment, and political support (Yağcı, Citation2017).

Informed by the SIA perspective, several structural and agential-level conditions enabled Governor Başçı to undertake combined policy and institutional entrepreneurship roles. At the organizational level, the CBRT has six primary internal sources of policy capacity that advance its bureaucratic agenda. These are:

(1) Ready availability of quality data; (2) human capital with high technical knowledge and expertise in evidence-based policy analysis and advice; (3) recruitment and career development practices enhancing policy analysis; (4) horizontal organizational arrangements that facilitate more interdepartmental interaction, communication and collaboration; (5) an organizational culture that is based on open discussions and risk-taking, promoting policy innovation; (6) policy learning and transfer capabilities arising from interactions with transnational epistemic community of central bankers. (Bakır & Kerem Çoban, Citation2019, p. 81-82)

At the individual level, Başçı had multiple professional identities as a respected academic, policy advisor to economy minister, deputy governor, and decision-maker. Furthermore, there was strong interpersonal ties and mutual trust between then-governor Başçı and then-minister Babacan based on their childhood friendship (Bakır & Kerem Çoban, Citation2019, p. 87). Organizational learning at the CBRT, combined with the institutional/policy entrepreneurship of CBRT Governor Erdem Başçı and political support from a critical minister, facilitated proactive policy design in Turkey (Yağcı, Citation2017). The professional identities and resources enabled him as an institutional entrepreneur to operate at the intersection of policy design and implementation in the institutionalization of macroprudential ideas through inter-bureaucratic sensemaking processes (Bakır, Akgünay, & Çoban, Citationforthcoming).

From an NIA perspective, the newly emerging macroprudential shift in the central banking paradigm allowed the CBRT opportunity structures with which to implement unconventional policies to reduce fragilities in the Turkish economy. The CBRT’s organizational competence and organizational learning facilitated by the institutional/policy entrepreneurship of Governor Başçı contributed to the macroprudential turn. In terms of diffusion, it can be claimed that emulation and learning played a critical role in the financial stability pursuit of the CBRT. Moreover, by framing its unconventional, experimental policies as macroprudential tools, the CBRT aimed to legitimate its policy framework in the eyes of domestic and international observers (Broome & Seabrooke, Citation2020). Nevertheless, CBRT’s active financial stability orientation created a political backlash.

In emerging economies, macroprudential measures in the aftermath of the GFC aimed to abate the negative consequences of capital flow surges. These countries aimed to reduce overheating in their economies by addressing the fragilities reflected in increasing debt levels for individuals and companies. In the case of rapid capital outflow, high debt levels would result in economic contraction and recession. On the other hand, the downside of the macroprudential measures would be a dampening of economic growth to reduce risks in the economy. The sharp decline of economic growth in 2012 after high growth rates in 2010 and 2011 made the CBRT the main culprit in the eyes of politicians (Yağcı, Citation2018). This was reinforced by the firmly held ideas by the then Prime Minister and later President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

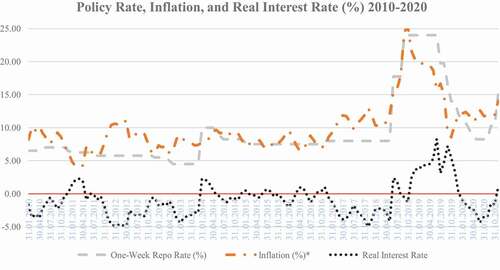

Erdoğan has long held the belief that high interest rates are the main cause of high inflation rates (Ant, Citation2019). In addition to his assertion that high interest rates would stall private sector investment and dampen economic growth (Dombey and Guler Citation2015), he sees interest rates as a ‘tool of exploitation’ (Pitel, Citation2018) and ‘mother of all evil’ (Coşkun, Citation2019), indicating a religious standpoint. His constant criticisms against high interest rates have forced the CBRT to use the asymmetric interest rate corridor to circumvent political pressure by maintaining a lower policy interest rate while keeping the real market funding rate or the weighted average funding rate determined by the CBRT’s liquidity policy at a much higher level (Yağcı, Citation2018). In other words, the policy interest rate became irrelevant for market players, and the credibility of the CBRT was significantly undermined. Thus, the interaction between global and domestic dynamics, compounded by the ideas held by powerful politicians, constrained central bank policy space and damaged CBRT independence and credibility. Nevertheless, political pressure against the CBRT escalated after the shift to a presidential system in 2018.

Central banking under the presidential system: President Erdoğan and his influence on monetary policyFootnote5

The June 2018 presidential election in Turkey, which was part of general and parliamentary elections, formalized the de facto presidential regime.Footnote6 In the presidential system of government, the Prime Minister’s office was abolished and replaced with the President’s office; the officeholder also became the head of the state, government, and ruling party. The Constitution of the Republic of Turkey, laws, and presidential decrees are the principal institutional resources that enable the President’s agency. Thus, the formal structural context (e.g. political regime change) and institutional context (e.g. legal changes) aligned with the informal institutions (e.g. the actions of the President). The presidential system of government with a strong leader tradition, is characterized by an ‘impositional and proactive policy style, and extensive use of institutional resources as tools such as presidential decrees with the effect of law in the appointment, dismissal, transfer, and promotion of politicians, judges, and senior bureaucrats’ (Bakır, Citation2020, p. 425). The result is ‘the presidentialisation of the executive branch and presidential bureaucracy’:

While presidentialisation of the executive branch and presidential bureaucracy offer more insights into quick and decisive policy responses than a parliamentary system of government, they are more likely to produce policy design and implementation failures … The quick and decisive policy responses are due to strong political and bureaucratic loyalty, obedience and commitment to implement the directions of the president and/or the presidential office without delays, vetoes or being watered down, which would otherwise occur in a parliamentary system of government. However, there are risks of policy design and implementation failures when policy problems are wrongly diagnosed, their policy solutions mistaken and/or complementary policy instrument mixes poorly implemented. This is because (1) there is both a limited delegation of discretionary authority and autonomy to executive branch and bureaucracy and a limited incentive for public sector actors to take discretionary actions; and (2) there is limited inclusiveness, and social diversity in relation to the definition of problems, and articulation and deliberation of policy solutions outside the ‘inner-cycle’ in the policy design process. Thus, there is a limited space for a genuine policy feedback and instrument calibration, and potential for failures in policy design and implementation process. (Bakır, Citation2020, p. 425, emphases in original)

The President presides over a centralized, hierarchical system of government in the presidential administration. Unsurprisingly, the President’s desires, preferences, choices, and decisions shape monetary policy decisions and actions. In other words, presidential policy preferences are embraced rather than contested or reversed by the central bankers. ‘Here, the normative values of the presidential executive and presidential bureaucracy include “loyalty”, “obedience” and “commitment” rather than professional norms such as a merit system, career civil service, and autonomous will, preference and action in public policymaking and bureaucratic processes’ (Bakır, Citation2020, p. 429). Turkey now maintains ‘a “strong leader tradition”, which encompasses the “presidentialisation” of the executive and “presidential” administration, referring to the greater use of the president’s unilateral power over the government, judiciary and bureaucracy in setting respective agendas and steering their implementation through the institutions and actors of the presidential system of government’ (Bakır, Citation2020, p. 428).

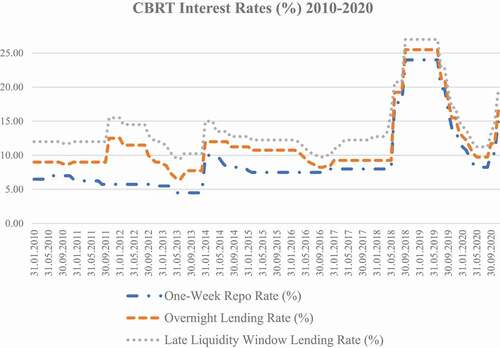

In the wake of the 2018 presidential elections, Erdoğan forcefully reinstated his normative and cognitive ideas on the interest rate instrument of the CBRT: ‘If my people say continue on this path in the elections, I say I will emerge with victory in the fight against this curse of interest rates … Because my belief is: interest rates are the mother and father of all evil’ (Edwards, Citation2018). Under this new structural, institutional environment dominated by the preferred decisions and actions of the strong political leader, the Turkish lira started to rapidly lose its value against major currencies such as the US dollar in 2018, and the CBRT was compelled to raise interest rates to halt the depreciation. According to reports, several government officials worked on a plan to obtain Erdoğan’s support for the rate hike, and in May 2018, the CBRT raised the late-liquidity rate by 300 basis points to 16.5% (Ant, Citation2018). In late May 2018, the CBRT announced that the one-week repo rate would be the policy rate, equal to the funding rate of 16.5% as of 1 June 2018 (CBRT, Citation2018). Later in June, the CBRT raised the interest rate to 17.75%, and since the depreciation of the Turkish lira persisted, CBRT raised the interest rate again in September 2018 by 625 basis points to 24% (). One day before the CBRT’s September rate hike, Erdoğan called interest the ‘tool of exploitation’ and criticized the CBRT for not meeting the inflation targets, maintaining that high interest rates were the main cause of high inflation rates in Turkey (Pitel, Citation2018).

CBRT Governor Murat Çetinkaya, who was appointed in 2016 and had one more year of service before the end of his term, was sacked from his position by a presidential decree in July 2019 for not cutting the CBRT interest rates to boost the economy. In the absence of a political actor, like Babacan, the new central bank governors became highly vulnerable to the President’s interventions. In the words of the President, ‘We believed that the person who was not conforming to instructions given on this subject of monetary policy, this mother of all evil called interest rates, needed to be changed’ (Coşkun, Citation2019). The new Governor, Murat Uysal, cut the interest rates by 425 basis points, from 24% to 19.75% in his first monetary policy meeting on July 25th, 2019. President Erdoğan passionately supported this decision but warned that it was not enough, urging the CBRT to continue rate cuts (Pitel, Citation2019). The CBRT reduced the policy interest rate to 8.25% with successive rate cuts by May 2020 (). However, low interest rates resulted in hot money outflows and a 30% plunge in the Turkish lira’s value against major currencies during this period, making it the worst-performing currency. The newly-appointed Governor Murat Uysal, who adopted the President directed monetary policy, was blamed for this outcome and dismissed by the President in November 2020, after 16 months of service as the Governor of the CBRT (Yackley, Citation2020).

Drawing on the Turkish state’s responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, Bakır (Citation2020) argued that in a crisis environment, ‘a temporal, albeit a temporary space for principal executive and bureaucratic agents are opened to exercise discretionary autonomy and authority in authoritative actions, and to adopt inclusive and diverse approach to effective policy design and implementation’. Indeed, the new Governor of the CBRT, Naci Ağbal, began his term in November 2020 with a 425 basis points interest rate hike, increasing the policy interest rate to 15%; he claimed that the CBRT would sustain tight monetary policy in consideration of achieving and maintaining price stability by ‘adopting transparency, predictability and accountability principles of the inflation targeting regime’ (CBRT, Citation2020). Temporary policy space for conventional monetary policy decisions and actions opened when the Turkish lira became the worst-performing emerging market currency by November 2020.

Since 2010, CBRT policies have resulted in negative real interest rates (). However, the insistence on low interest rates could not keep the Turkish economy on a sustainable growth path, did not reduce the Turkish economy’s fragilities, and accelerated the Turkish lira’s rapid depreciation against major currencies since 2018. The Turkish experience illustrates power asymmetries in international finance and the constraints placed upon emerging economy central banks by both global and domestic pressures in policymaking.

Discussion and conclusion

Since the onset of the GFC, there has been a pressing need for a better understanding of why and how central banks make specific policy decisions; how international and domestic dynamics influence these decisions; the role that structures, institutions, and agency play; and how these policies impact economic, social, and political phenomena (Bakır, Citation2013, Citation2017). We argue that an analytic eclectic perspective can bridge macro, meso, micro-level analyses, thereby unravelling the interaction of international and domestic forces that are translated into specific policy choices. Moreover, a global comprehension of central banking necessitates going beyond the analysis of central banks in advanced industrialized countries (Yağcı, Citation2020).

In this article, we explore the evolution of the Turkish political economy and resulting central bank practices from an interdisciplinary perspective in our attempts to bridge IPE and PPA scholarship. Informed by the SIA framework, our eclectic approach employs the NIA of IPE, suggesting that power asymmetries reflected in the interdependent international finance system create both opportunities and constraints for emerging economy central banks (Farrell & Newman, Citation2016). Furthermore, our analysis suggests that international influences should be examined in consideration of the domestic political economy context and the key actors involved in the policymaking process. We posit that the structural and agency-level focus of NIA can complement PPA scholarship with regard to how the politics of ideas influence the policymaking process, revealing the tensions, struggles, and contestations in monetary policymaking by linking inputs, outputs, and outcomes (Guidi et al., Citation2020). By combining macro, meso, and micro-level analyses, we also highlight the crucial role that individual and organizational agency play in institutional/policy change.

Our investigation also underlines how the ideas held by powerful politicians constrain central bank behavior. In this respect, by untangling political tensions and struggles in the policymaking process, assessing how politicians support or undermine monetary policy decisions, and analyzing how stakeholders perceive and evaluate central banking activity, we uncover the complex dynamics that influence central bank behavior. Moreover, these investigations reveal the forces operating behind the strength or weakness of a monetary policy regime in diverse contexts (Yağcı, Citation2018). Relatedly, contextualization of the global diffusion of ideas and norms is critical in enhancing our understanding of why and how central bank activities shape and influence social, political, and economic life in different countries (Bakır, Citation2017).

We share the commitment to the issues raised in debates on IPE scholarship (including the importance of problem-driven research) by focusing on ambitious questions and preserving the pluralism and diversity present in theoretical and methodological approaches. We also share the predisposition of one of the leading figures of IPE discipline, Susan Strange, who posits that IPE should be an eclectic research venue open to all disciplines and methodological/theoretical orientations so that it may account for different aspects of social, political, and economic phenomena (Strange, Citation1991). Similarly, there is a need to dismantle the disciplinary boundaries of PPA scholarship through the investigation of macroeconomic issues and the introduction of analytic eclectic perspectives that combine various explanations of divergent research traditions (Han et al., Citation2020). The complex interdependence in the global system and implications for particular countries in different policy areas can best be examined by analytic eclecticism so that diverse and flexible frameworks can be pragmatically combined to address multidimensional research questions relating to policy and practice (Sil & Katzenstein, Citation2010). IPE and PPA dialogue offer one particular avenue of achieving analytic eclecticism, and we maintain that this dialogue enhances our understanding of not only central banking but also many other research areas awaiting exploration by researchers of diverse backgrounds.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mustafa Yagci

Mustafa Yagci is an Assistant Professor of International Political Economy at the Political Science and Public Administration Department of Istinye University, Istanbul.

Caner Bakir

Caner Bakir is a Professor of Political Science with particular emphasis on International and Comparative Political Economy, and Public Policy and Administration of the College of Administrative Sciences and Economics at Koç University.

Notes

1 For analytic eclecticism, see Sil and Katzeinstein (Citation2010).

2 Following Kingdon (Citation1984) policy entrepreneurs set the governmental agenda through coupling multiple policy, problem and politics streams. Institutional entrepreneurs use discursive and powering strategies for the institutionalisation of policy ideas (Bakır et al., Citationforthcoming).

3 For an exception, see Bakır (Citation2009).

4 The asymmetric interest rate corridor aims to create a managed uncertainty about short-term yields to discourage short-term capital flows (Aysan, Fendoglu, & Kilinc, Citation2014). The reserve option mechanism allows banks to deposit foreign currencies or gold for their Turkish lira reserve requirements to limit their exposure to external funding (Alper, Kara, & Yorukoglu, Citation2013). The asymmetric interest rate corridor is a known but rarely used monetary instrument (Goodhart, Citation2013). The reserve option mechanism, on the other hand, was first developed and utilized by the CBRT. CBRT officials indicate that it was examined closely by IMF officials, but they could not find any flaw in its design and implementation (Yağcı, Citation2017). Along with these unconventional monetary policy measures, the CBRT adopted a one week repo auction rate as the main policy instrument and began flexible use of liquidity management for its pursuit of financial stability.

5 In this section our focus is on the interest rate decisions of the CBRT but we believe that other economic policies under the presidential system require further, more detailed examination in a separate study.

6 Following his election by popular vote in August 2014 in the parliamentary regime, the President was re-elected in the presidential elections. Following the June 2018 presidential election, the ruling party of the President regained its absolute majority in the parliament with 317 of 550 seats.

References

- Abdelal, R. (2007). Capital rules: The construction of global finance. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Adolph, C. (2018). The missing politics of central banks. PS: Political Science & Politics, 51(4), 737–742.

- Ahmed, S., & Zlate, A. (2014). Capital flows to emerging market economies: A brave new world? Journal of International Money and Finance, 48, 221–248.

- Alper, C. E., & Öniş, Z. (2003). Emerging market crises and the IMF: Rethinking the role of the IMF in light of Turkey’s 2000-2001 financial crisis. Canadian Journal of Development Studies-Revue Canadienne D Etudes Du Developpement, 24(2), 267–284.

- Alper, K., Kara, H., & Yorukoglu, M. (2013). Reserve options mechanism. Central Bank Review, 13(1), 1–14.

- Andrews, D. M. (1994). Capital mobility and state autonomy: Toward a structural theory of international monetary relations. International Studies Quarterly, 38(2), 193–218.

- Ant, O. (24 May 2018). How markets won: Erdogan concedes a hated rate hike to save lira. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-05-24/how-markets-won-erdogan-concedes-a-hated-rate-hike-to-save-lira

- Ant, O. Behind Erdogan’s strange ideas about interest rates. Bloomberg, August 2, 2019. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-08-02/behind-erdogan-s-strange-ideas-about-interest-rates-quicktake.

- Aysan, A. F., Fendoglu, S., & Kilinc, M. (2014). Managing short-term capital flows in new central banking: Unconventional monetary policy framework in Turkey. Eurasian Economic Review, 4(1), 45–69.

- Baker, A. (2013). The New Political Economy of the Macroprudential Ideational Shift. New Political Economy, 18(1), 112–139.

- Bakır, C. (2007). Merkezdeki Banka ve Uluslararası Bir Karşılaştırma. İstanbul: İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları.

- Bakır, C. (2009). Policy entrepreneurship and institutional change: Multi-level governance of central banking reform. Governance, 22(4), 571–598.

- Bakır, C. (2013). Bank behavior and resilience: The effects of structures, institutions and agents. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bakır, C. (2017). How can interactions among interdependent structures, institutions, and agents inform financial stability? What we have still to learn from global financial crisi. Policy Sciences, 50(2), 217–239.

- Bakır, C. (2020). The Turkish state’s responses to existential COVID-19 crisis. Policy and Society, 39(3), 424–441.

- Bakır, C., Akgünay, S., & Çoban, K. (forthcoming). Why does the combination of policy entrepreneur and institutional entrepreneur roles matter for the institutionalization of policy ideas? Policy Sciences.

- Bakır, C., & Darryl, S. L. J. (2017). Contextualising the context in policy entrepreneurship and institutional change. Policy and Society, 36(4), 465–478.

- Bakır, C., & Kerem Çoban, M. (2019). How can a seemingly weak state in the financial services industry act strong? the role of organizational policy capacity in monetary and macroprudential policy. New Perspectives on Turkey, 61, 71–96.

- Bakır, C., & Öniş, Z. (2010). The regulatory state and turkish banking reforms in the age of Post‐Washington consensus. Development and Change, 41(1), 77–106.

- Ban, C. (2016). Ruling ideas: How global neoliberalism goes local. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Battilana, J., Leca, B., & Boxenbaum, E. (2009). How actors change institutions: Towards a theory of institutional entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), 65–107.

- Bauerle Danzman, S. W., Winecoff, K., & Oatley, T. (2017). All crises are global: Capital cycles in an imbalanced international political economy. International Studies Quarterly, 61(4), 907–923.

- Béland, D. (2009). Ideas, institutions, and policy change. Journal of European Public Policy, 16(5), 701–718.

- Béland, D. (2019). How ideas and institutions shape the politics of public policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bertelli, A. M., Hassan, M., Honig, D., Rogger, D., & Williams, M. J. (2020). An agenda for the study of public administration in developing countries. Governance, 33(4), 735–748.

- Bertelli, A. M. (2012). The political economy of public sector governance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Binder, S., & Spindel, M. (2017). The myth of independence: How congress governs the federal reserve. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Binder, S., & Spindel, M. (2018). Why Study Monetary Politics? PS: Political Science & Politics, 51(4), 732–736.

- Blyth, M. (2002). Great transformations: Economic ideas and institutional change in the twentieth century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Borio, C., & Disyatat, P. (2010). Unconventional monetary policies: An appraisal. The Manchester School, 78(1), 53–89.

- Broome, A., & Seabrooke, L. (2020). Recursive recognition in the international political economy. Review of International Political Economy, 28(2), 369-381 .

- Campbell, J. L. (1998). Institutional analysis and the role of ideas in political economy. Theory and Society, 27(3), 377–409.

- Campbell, J. L., & Kaj Pedersen, O. (ed). (2001). The rise of neoliberalism and institutional analysis. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- CBRT 2018. Press release on the operational framework of the monetary policy. May 28, https://www.tcmb.gov.tr/wps/wcm/connect/EN/TCMB+EN/Main+Menu/Announcements/Press+Releases/2018/ANO2018–21.

- CBRT 2020. Press release on interest rates. November 19, https://www.tcmb.gov.tr/wps/wcm/connect/EN/TCMB+EN/Main+Menu/Announcements/Press+Releases/2020/ANO2020–68.

- Chaudoin, S., & Milner, H. V. (2017). Science and the system: IPE and international monetary politics. Review of International Political Economy, 24(4), 681–698.

- Corder, K. (2014). Central bank autonomy: The federal reserve system in American politics. London: Routledge.

- Coşkun, O. Turkey’s central bank governor was sacked after resisting 300 point rate cut: Sources. Reuters, July 22, 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/usturkey-cenbank-governor/turkeys-central-bank-governor-was-sacked-after-resisting-300-point-rate-cut-sources-idUSKCN1UH142.

- Derthick, M., & Quirk, P. J. (1985). The politics of deregulation. Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Derviş, K. (2005). Returning from the brink: Turkey’s efforts at systemic change and structural reform. In T. Besley & R. Zagha (Eds.), Development Challenges in the 1990s: Leading policymakers speak from experience (pp. 81–102). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dombey, D., & Güler, F. Turkey’s lira slides as erdogan attacks central banker. Financial Times, March 4, 2015. https://www.ft.com/content/c0eaf6a0-c287-11e4-ad89-00144feab7de.

- Dönmez, P. E., & Zemandl, E. J. (2019). Crisis of capitalism and (de-)politicisation of monetary policymaking: reflections from Hungary and Turkey. New Political Economy, 24(1), 125–143.

- Edwards, J. 2018. Turkey’s lira Crisis may be down to erdogan’s fundamental misunderstanding of how ‘evil’ interest rates work. Business Insider August 10, https://www.businessinsider.com/turkish-lira-crisis-erdogan-interest-rates–2018–8.

- Ersel, H. (1996). The timing of capital account liberalization: The Turkish experience. New Perspectives on Turkey, 15, 45–64.

- Farrell, H., & Newman, A. (2016). The new interdependence approach: Theoretical development and empirical demonstration. Review of International Political Economy, 23(5), 713–736.

- Galati, G., & Moessner, R. (2013). Macroprudential policy–a literature review. Journal of Economic Surveys, 27(5), 846–878.

- Gallagher, K. P. (2014). Ruling capital: Emerging markets and the reregulation of cross-border finance. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Gemici, K. (2012). Rushing toward currency convertibility. New Perspectives on Turkey, 47, 33–55.

- Gill, S. R., & Law, D. (1989). Global hegemony and the structural power of capital. International Studies Quarterly, 33(4), 475–499.

- Goodhart, C. A. (2013). The potential instruments of monetary policy. Central Bank Review, 13(2), 1–15.

- Guidi, M., Guardiancich, I., & Levi‐Faur, D. (2020). Modes of Regulatory Governance: A Political Economy Perspective. Governance, 33(1), 5–19.

- Hall, P. A. (ed). (1989). The political power of economic ideas: Keynesianism across nations. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Hamilton-Hart, N. (2002). Asian states, Asian Bankers: Central banking in Southeast Asia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Hammond, T. H., & Knott, J. H. (1999). Political institutions, public management and policy choice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 9(1), 33–86.

- Han, Y., Xiong, M., & Frank, H. A. (2020). Public administration and macroeconomic issues: Is this the time for a marriage proposal? Administration & Society, 52(9), 1439-1462.

- Hay, C. (2006). Globalization and public policy. In M. Moran, M. Rein, & R. E. Goodin (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of public policy (pp. 587–605). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Howlett, M., & Giest, S. (2012). The policy-making process. In E. Araral, S. Fritzen, M. R. Michael Howlett, & W. Xun (Eds.), Routledge handbook of public policy (pp. 35–46). London: Routledge.

- Jacobs, L. R., & King, D. S. (2016). Fed power: How finance wins. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- John, P. (2018). Theories of policy change and variation reconsidered: A prospectus for the political economy of public policy. Policy Sciences, 51(1), 1–16.

- Johnson, J. (2016). Priests of prosperity: How Central bankers transformed the postcommunist world. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Kahler, M. (2016). Complex governance and the New Interdependence Approach (NIA). Review of International Political Economy, 23(5), 825–839.

- Kara, H. (2016). A brief assessment of turkey’s macroprudential policy approach: 2011–2015. Central Bank Review, 16(3), 85–92.

- Katzenstein, P. J., & Nelson, S. C. (2013). Reading the right signals and reading the signals right: IPE and the financial crisis of 2008. Review of International Political Economy, 20(5), 1101–1131.

- Kingdon, J. W. (1984). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. Boston: Little, Brown.

- Knott, J. H., & Miller, G. J. (2006). Social Welfare, corruption and credibility: Public management’s role in economic developmen. Public Management Review, 8(2), 227–252.

- Knott, J. H., & Miller, G. J. (2008). When ambition checks ambition: Bureaucratic trustees and the separation of powers. The American Review of Public Administration, 38(4), 387–411.

- Kutlay, M. (2019). The political economies of Turkey and Greece: Crisis and change. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Levingston, O. (2020). Minsky’s moment? The rise of depoliticised keynesianism and ideational change at the federal reserve after the financial crisis of 2007/08. Review of International Political Economy, 1–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1772848

- Maxfield, S. (1994). Financial incentives and central bank authority in industrializing nations. World Politics, 46(4), 556–588.

- Miller, G. J. (1992). Managerial dilemmas: The political economy of hierarchy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Miller, G. J. (2005). The political evolution of principal-agent models. Annual Review of Political Science, 8(1), 203–225.

- Miller, G. J., & Whitford, A. B. (2016). Above politics: Bureaucratic discretion and credible commitment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mintrom, M., & Williams, C. (2012). Public policy debate and the rise of policy analysis. In E. Araral, S. Fritzen, M. R. Michael Howlett, & W. Xun (Eds.), Routledge handbook of public policy (pp. 3–16). London: Routledge.

- Nelson, S. C. (2017). The currency of confidence: How economic beliefs shape the IMF’s relationship with its borrowers. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Nelson, S. C. (2020). Constructivist IPE. In E. Vivares (Ed.), The routledge handbook to global political economy: Conversations and Inquiries (pp. 211–228). London: Routledge.

- Nelson, S. C., & Katzenstein, P. J. (2014). Uncertainty, risk, and the financial crisis of 2008. International Organization, 68(2), 361–392.

- North, D. C., & Weingast, B. R. (1989). Constitutions and commitment: The evolution of institutions governing public choice in seventeenth-century England. The Journal of Economic History, 49(4), 803–832.

- Oatley, T. (2011). The reductionist gamble: Open economy politics in the global economy. International Organization, 65(2), 311–341.

- Oatley, T. (2019). Toward a political economy of complex interdependence. European Journal of International Relations, 25(4), 957–978.

- Perl, A. (2012). International dimensions and dynamics of policy-making. In E. Araral, S. Fritzen, M. R. Michael Howlett, & W. Xun (Eds.), Routledge handbook of public policy (pp. 44–56). London: Routledge.

- Pitel, L. Turkey’s erdogan calls interest rates ‘tool of exploitation Financial Times, September 13, 2018. https://www.ft.com/content/e15f8e00-b734-11e8-bbc3-ccd7de085ffe

- Pitel, L. Turkey’s president calls for further interest rate cuts Financial Times, July 26, 2019. https://www.ft.com/content/974c1b5a-af9d-11e9-8030-530adfa879c2.

- Polillo, S., & Guillén, M. F. (2005). Globalization pressures and the state: The worldwide spread of central bank independence. American Journal of Sociology, 110(6), 1764–1802.

- Quirk, P. J. (1988). In defense of the politics of ideas. The Journal of Politics, 50(1), 31–41.

- Roberts, A. (2020). Bridging levels of public administration: How macro shapes meso and micro. Administration & Society, 52(4), 631–656.

- Sahasrabuddhe, A. (2019). Drawing the line: The politics of federal currency swaps in the global financial crisis. Review of International Political Economy, 26(3), 461–489.

- Samman, A., & Seabrooke, L. (2016). International political economy. In X. Guillame & P. Bilgin (Eds.), Routledge handbook of international political sociology (pp. 46–59). London: Routledge.

- Schwartz, H. M. (2016). Banking on the FED: QE1-2-3 and the rebalancing of the global economy. New Political Economy, 21(1), 26–48.

- Sil, R., & Katzenstein, P. J. (2010). Analytic eclecticism in the study of world politics: Reconfiguring problems and mechanisms across research traditions. Perspectives on Politics, 8(2), 411–431.

- Simmons, B. A., Dobbin, F., & Garrett, G. (2006). Introduction: The international diffusion of liberalism. International Organization, 60(4), 781–810.

- Singer, D. A. (2007). Regulating capital: Setting standards for the international financial system. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Strange, S. (1991). An eclectic approach. In N. M. Craig & T. Roger (Eds.), The new international political economy (pp. 33–49). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Takagi, Y. (2016). Central banking as state building: Policymakers and their nationalism in the Philippines, 1933–1964. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press.

- Yackley, A. J. (November 7, 2020). Erdogan ousts head of Turkish central bank after lira plunge, Financial Times, https://www.ft.com/content/4e65286e-a33b-49b2-a5c4-b21b5cfa01fb.

- Yağcı, M. (2017). Institutional entrepreneurship and organizational learning: financial stability policy design in Turkey. Policy and Society, 36(4), 539–555.

- Yağcı, M. (2018). The political economy of central banking in Turkey: The macroprudential policy regime and self-undermining feedback. South European Society and Politics, 23(4), 525–545.

- Yağcı, M. (ed). (2020). The political economy of central banking in emerging economies. London: Routledge.

- Zayim, A. (2020). Inside the black box: Credibility and the situational power of central banks. Socio-Economic Review, mwaa011, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwaa011, 1–31.

- Zhang, X. (2005). The changing politics of central banking in Taiwan and Thailand. Pacific Affairs, 78(3), 377–401.