ABSTRACT

Critical decolonial assessments of International Political Economy (IPE) curricula have found a continued dominance of Euro-Western perspectives. However, these critical assessments have often been of specific programs or courses. In this article, we open the canvas wider in our quantitative assessment of privilege and marginalization, by conducting an analysis of IPE curricula from universities from around the world as well as of one of the most widely used introductory textbooks in the field. We find that scholars based outside of the Euro-West are marginal, while those based in the Euro-West continue to be dominant – in all the assessed course offerings. We also find that female voices are marginal, in all locations. Knowledge production systems privilege Euro-Western male voices and perspectives, furthering a process of systemic cognitive and epistemic injustices. Building upon our analysis of teaching and learning content, this article critically reflects on the implications of when IPE meets policy, and offers avenues for the policy engagement to avoid the same processes of privileging and marginalizing, and thereby better situating policy making to avoid repeating failures resulting from the identified entrenched biases.

Introduction

The academic knowledge production system is plagued by power asymmetries, whereby the voices of some are privileged, and others marginalized (Grosfoguel, Citation2007; Mignolo, Citation2011a; Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Citation2018). There have been waves of resistance against the structures that uphold these systems, one recent example of which being the Rhodes Must Fall movements in South Africa. A component of contestation amidst demands for the decolonization of such academic knowledge production systems relates to how the products are used in teaching and learning in higher education, such as calls for decentering and recentering voices and perspectives, thereby embracing diverse ecologies of knowledges (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Citation2018; Zondi, Citation2018). Epistemological silencing and the exclusion of the voices of those considered as ‘others’ are part of the outcomes of the European Enlightenment and Euro-Western modernity (Icaza, Citation2017; Mignolo, Citation2011b), wherein racism is entrenched (e.g. Eze, Citation2008). One reason for this, as Ndlovu-Gatsheni (Citation2018) has explained, is that knowledge produced in the Euro-West is considered ‘international’ and positioned to add value on a global scale, while knowledge produced anywhere else is viewed as ‘local’ knowledge, a framing that perpetuates epistemic hegemony. Another reason is what has been considered important for teaching and learning within international political economy (IPE) and global political economy (GPE), which has tended to exclude issues of coloniality, race, gender and certain forms of power. The continued selection of Euro-Western ideas and thinkers for teaching IPE and GPE is not a matter of the ‘best ideas floating to the top’, rather this is a process of exclusion and prioritization that results in the killing of diverse knowledge systems, what Hall and Tandon (Citation2017) call systemic epistemicide. As the scholars in this thematic issue explore the engagements between IPE and policy, we critically question the foundations of IPE in this interaction and the implications thereof.

Despite changes to the architecture of knowledge production around the world, such as efforts to centre national language and promote the establishment of new journals, the Euro-Western voice remains dominant in the teaching and learning of IPE and GPE (for the sake of readability, this article refers to IPE from this point on, which is inclusive of GPE). This dominance manifests in various ways, such as who sits on editorial boards, acts as keynote speakers, participates in conferences, publishes in journals, designs curricula and authors textbooks. Having been involved in these conversations in the Global South and the Global North (terms we use drawing upon the history of the Bandung Conference of 1955 and the member states of the Non-Aligned Movement), we experienced that while there is often a recognition of exclusion, the response tends to be tokenistic (e.g. creating an elective course or adding an additional reading to the syllabus). Without a quantitative assessment of curricula and textbooks, we struggled to make a more forceful case regarding a systemic issue, which would warrant more substantive responses. Relatedly, without such quantitative data, we have encountered barriers in calling for academic democracy and ecologies of epistemology and knowledges. The purpose of this article is to analyze the preponderance of epistemic dominance in IPE curricula and the need for decolonization. Building upon those findings, we then critically reflect on what these findings imply for the engagement between IPE and policy.

Located within the ongoing debate on decolonization and recentering the diverse voices of humanity in IPE, this article is an attempt to offer a quantitative assessment of privilege and marginalization, by conducting an analysis of curricula from universities in the Euro-West and around the world as well as one of the most widely used introductory textbooks in the field. While some previous works have looked at curricula within the Euro-West (e.g. Mantz, Citation2019), we build upon that by also looking at IPE curricula globally. In both political-geographic spaces, we focus on universities offering IPE courses and/or degrees (albeit this process was challenged by limited accessibility to syllabi, as described below).

Within the teaching and learning of IPE, we find that scholars living outside of the Euro-West are marginal, while those based in the Euro-West are dominant – we found this to be the case in all the syllabi assessed, in all locations. We also find that female voices are marginal, particularly in syllabi, in all locations. In other words, the asymmetries of power embedded within knowledge production systems continue to privilege Euro-Western male voices and perspectives, while marginalizing and others, thereby furthering a process of systemic epistemicide. The asymmetries inculcated and encultured through the training of future policymakers within IPE courses and programs facilitate the replication of privilege and marginalization in policy. This results in the continuation and entrenchment of silencing all other perspectives and priorities while privileging the Euro-Western ones.

Decolonizing curricula is not simply a matter of tokenistic inclusion, but one of thoughtful and critical engagement with a range of epistemic and ontological traditions, each offering their own linguistic, historical and socio-cultural foundations. Before a call for democratizing knowledge can be made, we must assess if such a call is indeed needed, or, as some learning materials proclaim, that Euro-Western biases have been sufficiently addressed. This paper offers such an assessment. After this introduction, the rest of the paper proceeds as follows: In the next section, we situate the paper within the past and contemporary critique of IPE. The third section contains the methodology used for data collection and analysis. In the fourth section, we analyze the data on curricula and textbooks used in IPE programs in universities around the world. In the fifth section, we place the analysis within the ongoing configuration of the global politics of knowledge production and relate this to the engagement IPE has with policy. In the concluding section, we affirm and reinforce the ongoing debates on the decolonization of IPE, calls for changes in the pedagogy of teaching IPE, and demands for the democratization of knowledge.

Situating the study

The subjugations put in place through the twin processes of imperialism and colonialism created the conditions for the coloniality of power, being and knowledge (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Citation2015a, Citation2021; Mignolo, Citation2003). In Africa, for instance, some European historians denied the existence of any form of history, suggesting that any history of Africa was that written by European historians. Hegel went as far as arguing that Africa was not part of history (see Afolayan, Yacoob-Haliso, & Oloruntoba, Citation2021). While other historians were less explicit, their choice to exclusively rely on the colonial record served the same purpose. Apart from the reification of European history and knowledge as the only authentic forms of knowing, border thinking has dominated the study of international relations and global politics for a long time. Border thinking is based on the hegemony of Euro-Western epistemology as the main source of knowledge, ‘grounded in one dimensional self- the one able to observe, scrutinize, and analyze the international, including other selves as well as their places and communities, who are there to be observed, scrutinized, and analyzed’ (Icaza, n.d:1). Epistemicide, the destruction and decentering of other knowledges, is normalized by positioning knowledge in the singular: Euro-Western modernity and science.

An analysis of the ongoing debates on the decolonization of IPE also must take, as a point of departure, the constitution of the ‘international’ and the power asymmetry that underpins the global political economy. In other words, we must ask the question, what is the epistemological meaning of the word international as a prefix to political economy? This question is important because of binary thinking and the importance of geography as a strong determinant factor in orienting the locus of enunciation (Icaza, Citation2017). Ndlovu-Gatsheni (Citation2018:20–21) takes the argument on the problematic nature of the word ‘international’ by highlighting its ontological bias. In this respect, he argues that Europe and North America constitute the ‘international’ and the rest of the world is ‘local’. Ndlovu-Gatsheni raised this point specifically within the context of knowledge production, such as the location of high impact journals and publishing houses, through which scholars seek validation to affirm their scholarship (and/or are required to be validated in for the purposes of hiring, promotion, tenure, granting of funding, et cetera). The framing of ‘international’ is but one example of many colonial frames that need to be questioned and critiqued (Vogel, Citation2021).

Contesting what ideas are valued and taught is not a new venture of critique in IPE. Phillips (Citation2005) and Taylor (Citation2005) challenged the geographic exclusion and universalizing of Euro-Western experiences in IPE. Hobson (Citation2012a, Citation2013) detailed the colonial, imperialist and Eurocentric origins of IPE, including an analysis of the narrow ideological and individual contributions worthy of in-depth consideration within the field. The former of these works (Hobson, Citation2012b), has been widely read and cited, providing a foundation for a wide range of critiques of IPE as a field of study and research. Building on the works of Hobson (Citation2012a, Citation2013), as well as Grosfoguel (Citation2007, Citation2011, Citation2013) and Ndlovu-Gatsheni (Citation2015a, Citation2015b, Citation2018), Mantz (Citation2019) reflected on a personal experience of an IPE graduate program in an unnamed UK university, outlining its Eurocentric nature and continuation of the coloniality of knowledge, calling for a decolonization of IPE. Critical reflections of the origins, development and utilization of ideas, as well as those that continue to be taught are important. However, the history and experience of one university does not necessarily reflect IPE as a field of research today, nor the international experience of teaching and learning. IPE may be Eurocentric and perpetuate colonial structures of knowledge in the UK, but does that apply generally? To answer this question, broader data sets would be required. This study provides one means to quantitatively answer this question.

Scholars of political economy, critical studies, development studies, and political anthropology, have critiqued knowledge production systems, which include identifying epistemic, ideological, and methodological biases. Relating this to critiques of IPE, we think it is important to recognize the diversity of paths taken to arrive at these critiques and contestations, and the specificity of our own. Our arrival to this line of questioning the politics and power of knowledge production follows revolutionary and critical scholars, specifically Fanon (Citation1952, Citation1963, Citation1964), Kwame Nkrumah (Citation1968, Citation1970, Citation1973), Cabral (Citation1977), Thiong’o (Citation1986, Citation1993, Citation2012), Samir Amin (Citation1976, Citation1989, Citation1997, Citation2004) and Achille Mbembe (Citation2001, Citation2013, Citation2016). Others have trodden different paths, such as through Mignolo (Citation2000, Citation2003, Citation2011b) via Anzaldúa (Citation1987) and Quijano (Citation2000), through Bhambra (Bhambra, Citation2007; Bhambra, Gebrial, & Nişancıoğlu, Citation2018) or Dabashi (Citation2015) via Said (Citation1979), amongst other routes. The terminologies that emerged along these pathways have varied: neocolonial, post-colonial, de-colonial; that is not our focus here. What we are concerned about is the potential for IPE curricula to have dehumanizing impacts. We are also concerned about the suffocating of other knowledge systems, ways of knowing and worldviews.

In response to the recognition of the challenges, many have moved well beyond critique and crafted and/or supported the creation of alternatives. We have worked to contribute content that can enable such a re-centering. One of us has led an effort to produce The Palgrave Handbook of African Political Economy (Oloruntoba & Falola, Citation2020), which includes contributions that specifically address the intersection between political economy and policy. Our experience, however, is that the emerging pedagogical alternatives have remained exceptional; found in area studies or critical studies, without altering the Euro-Western dominance of IPE as a field of inquiry. As an example, while The Palgrave Handbook of African Political Economy is an impressive collection of contributions spanning over a thousand pages, we have seen that it is being found within Africa-specific courses, a tokenism like the changes that came before it, or an exception that continues to prove the embedded and accepted norm. Therein lies our interest to assess and contest the dominant narrative: IPE claims to have overcome biases, with new textbooks prolcaiming a non-Eurocentric approach. This paper inquires if the knowledge base, perspectives, and voices remain dominantly Euro-Western and male, or if significant changes have been brought about.

Methods and limitations

This study draws upon two sets of data: (1) course outlines/syllabi for IPE courses offered by universities around the world, (2) the bibliography of a commonly used IPE textbook in English-speaking universities. Each of the publications listed in the two data sets was put into an Excel database and analyzed based on a range of factors (namely: name of first author, gender of first author, place of employment of first author, country of place of employment of first author, region of place of employment of first author, publisher, type of publication, country of publisher). This categorization gave us a wealth of data to work with; however, the focus of this paper is upon two categories: country of place of employment of first author and gender of first author. The data was obtained through a manual search process, and all details input accordingly. Regarding the data: gender was as expressed on faculty or other relevant websites; place of employment was the primary place of employment (not a temporary fellowship, secondment or sabbatical position); country of the publisher was the primary headquarters. In the textbook bibliography, there were 984 references. In the set of 12 course outlines, there were 778 readings. A total of 1,762 references were individually analyzed and input into the database for analysis.

There are a number of limitations that are important to elaborate upon before delving into the results. One of the limitations of analyzing IPE course outlines/syllabi from around the world is that we only analyzed English language offerings. This presents a serious limitation in our attempt to offer a global perspective of IPE. As an example, many universities in Central and South America teach in Spanish or Portuguese and use materials in those languages. Similarly, many countries in Central and West Africa teach in French and use material in that language. Our study does not cover these geographies or languages, nor many others. While this is a limitation for this study, we believe this presents an opportunity for future research to complement this study, allowing for comparative analyses of geographic and linguistic trends. These are studies that we keenly look forward to seeing. Similarly, we use one of the most widely adopted textbooks globally, but others also require assessment. We hope future research will expand this type of study to build upon what was done within this work.

A second key limitation of this study is the focus solely on first authors. This decision was made because first authors tend to be those who made the largest contribution to the publication; however, we recognize that there are a wide range of practices regarding determining author order. This also presents a limitation because the other authors are not included in our analysis, which may further the under-representation of global contributions. However, we made this decision intentionally. Far too often ‘partners’ based outside of the Euro-West are relegated to data collection roles and listed as authors who have made less of a contribution to the publication and therefore are listed later in the ordering of authors. This power dynamic is not only one of appearances because employers regularly assess applicants based on sole-author or first-author publications when making hiring and promotion decisions. This is also the case for research funding applications. In other words, author ordering matters, hence our decision to focus upon it within our analysis. We have thus focused on first authors in this paper; however, in order to address this limitation, future research could consider a proportional weighting approach of multi-author publications so as to include all authors and compare those results to the ones presented here.

One of the categorizations that we anticipate reviewers and readers may find the most controversial or problematic is the focus on current place of employment. Is it not, as Simukai Chigudu (Citation2021) articulated, that change and decolonization is necessary in the Euro-West as well? For this to occur, do we not need radical scholarship from a global background within those institutions? Are we not making invisible critical scholars based within the Euro-West? In focusing upon the place of employment, we are not discounting the role of critical scholars wherever they may be; however, our decision to focus upon this factor is not necessarily to speak of origins or traditions of thought but of the politics and power of knowledge production. Both of us have spent time in the Euro-West as researchers and professors. We recognize how challenging this division is, however, the alternatives we explored seemed, from our perspective, even more problematic (e.g. attempting to categorize epistemologies or individuals). We suggest that the asymmetries of power in the knowledge production system are also intertwined within the ways in which some critical voices are elevated over others, a point of critical self-reflection for those engaged within efforts of decentering and recentering. We have seen that papers published in New York, London and Toronto – regardless of who wrote them – were more valued than those published in Dhaka, Kampala and Kingston. By valued we do not mean quality, we mean in terms of being taught as important contributions to the field of IPE as required readings in syllabi and included as references in textbooks. This study was an attempt to explore if our experiences were reflective of the broader experience, or not.

When we started this study, we began by listing the top ranked IPE graduate programs around the world. We consulted various indices and listings, however, when we set about searching for course outlines with detailed reading lists it was apparent that most faculty do not place their course reading lists online. Due to the linguistic and availability barriers, this selection presents some limitations (note: there is no global repository of course outlines to draw upon for a more systematic approach). Our inclusion of course outlines is broadly influenced by well-regarded university programs as well as by those course outlines that were publicly available. We attempted to include the most recently available course outlines, but we intentionally do not include the course numbers or instructor names. Our purpose is not to put the spotlight on specific individuals, but rather to identify systemic issues. From the Euro-West, we included outlines from six universities: Harvard University, John Hopkins University (JHU), George Washington University (GWU), Waterloo University, University of Hamburg and the London School of Economics (LSE). From around the world, we included outlines from six universities: International University of Japan (IUJ), National University of Singapore (NUS), the American University of Beirut (AUB), the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits), Catholic University of Chile (PUC), and the University of Ghana (UGhana).

Curricula

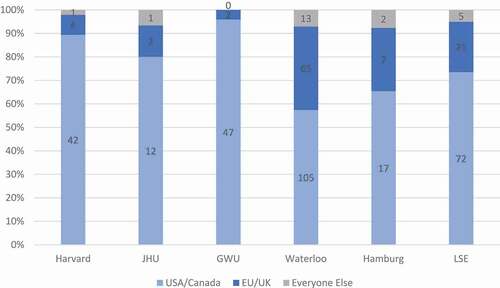

The following presents an analysis of the course readings listed for students to read, first exploring geographies and then gender. Within universities in the Euro-West (), the readings that were included in the course syllabi were dominated by contributors based in the United States and Canada (none had less than 50% of all readings from there), followed by readings from the EU/UK. When the USA/Canada readings are combined with readings from the EU and UK, we find that over 90% of all readings, in all courses, were written by authors based in the Euro-West. In the GWU syllabus, zero readings were written by authors based outside of the Euro-West. In other instances, such as at LSE, there were a few ‘others’ included (readings from authors based everywhere else in the world), however the authors from the five readings at LSE that were not located in the Euro-West were written by scholars based in either Australia or Israel. Looking across all of these curricula, we find that scholars based in the Euro-West continue to have an overwhelmingly dominant voice in IPE course readings.

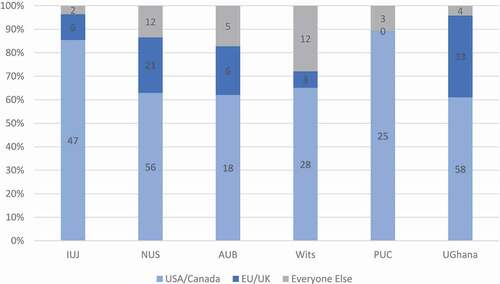

Within universities around the world (), the situation does not look much different: no less than 60% of all readings were written by authors based in the US or Canada, and when combined with those based in the EU or UK, the large majority of readings in all programs were written by scholars based in the Euro-West. Wits (South Africa) appears slightly more diverse than all others (with 28% of readings being written by scholars based beyond those Euro-Western geographies). However, on closer inspection, the readings at Wits that were written by scholars living outside of the Euro-West tended to be South African authors providing case study material, which was not necessarily IPE content but contextual (e.g. on financial institutions, trade, commodities). Nonetheless, Wits was the only university of the 12 analyzed to have materials written by authors beyond the Euro-West that exceeded 20% of the readings. On the whole, we find, regardless of where one studies or teaches IPE, the ideas and scholars that are valued enough to be placed on reading lists within curricula are those based in the Euro-West. We reiterate that this is not necessarily epistemologically or ontologically uniform but is reflective of the asymmetrical power within systems of knowledge production.

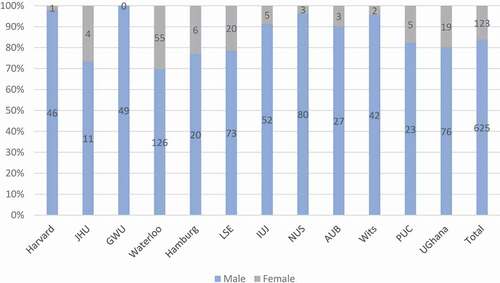

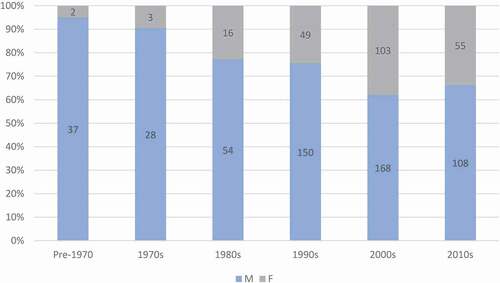

In addition, regardless of where one studies or teaches, there is a secondary systemic bias toward male authorship (). Across the 12 university courses analyzed, the highest percentage of female authors was 30% (at Waterloo), with GWU have zero female authors on the course readings list. Combining all the readings across all 12 universities, one-fifth of first authors are female. The privileging of male voices and perspectives in knowledge production is not specific to IPE and is reflective not only of the field but also of most disciplines. This systemic bias is prevalent in much of academic knowledge production. However, these results also show that there are options available, which could be integrated into course readings, as shown in the significant variation (between 0% and 30% of course readings haivng female first authors). Furthermore, when the two findings are taken together, in there is a compounding of exclusion whereby female authors based outside the Euro-West are particularly marginalized, whose contributions are made almost entirely absent.

The three figures above confirm our assumption that power asymmetries remain pronounced in the teaching and learning of IPE. The implications of this are multiple: yet another generation of students are being trained within this narrow perspective; graduates may later make decisions upon this biased basis; graduates may later teach these traditions to others as that is what they were taught; because of this continuation current and future students may devalue others via this learning process, and may dehumanize those whose perspectives, voices, histories, and ideas were deemed not sufficiently valuable for inclusion in their IPE learning experience. The preference of authors based in the Euro-West in the reading lists is reflective of a long-held culture of epistemic silencing and erasure.

Assessing source material in an IPE textbook

In conducting this study, we found that certain textbooks were commonly used, around the world. One of the prominent textbooks used globally, now in its 6th edition, was Global Political Economy: Evolution and Dynamics, by O’Brien and Williams (Citation2020), amongst two or three others, all of which were written by scholars in the Euro-West and also published in the Euro-West. In addition to being widely used, the back of the 6th version of the O’Brien and Williams textbook states that a key features of the 2020 edition is ‘a non-Eurocentric approach to the global economy’. Indeed, the authors cite some of the critical works we have mentioned, such as those of Phillips (Citation2005) and Taylor (Citation2005), which highlight that the majority of humanity and their diverse perspectives are excluded in IPE, as well as the fact that issues of race are absent in much of IPE. In the textbook, O’Brien and Williams (Citation2020) argue that there are many good reasons to expand IPE. In addition to its wide adoption, in selecting this textbook for detailed analysis, we are – at least in theory – selecting a textbook that should be the counter to the norm of what has been an area of study where Euro-Western ideas and people have dominated. We have not selected a textbook that is explicitly biased toward the Euro-West, indeed this textbook claims to offer the opposite; hence, we view it as a useful candidate for assessing how transformed this ‘non-Eurocentric approach’ is.

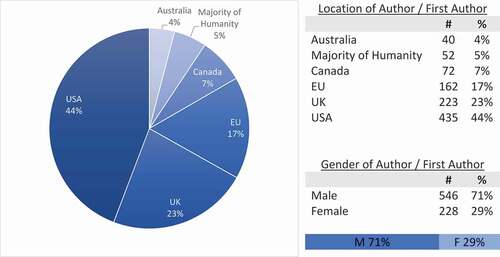

In analysing all of the source materials that O’Brien and Williams (Citation2020) cited in their textbook, nearly a thousand references in the bibliography, we find that authors based in the Euro-West are dominant (). As with the course readings, scholars based in the US and Canada account for more than half (US 44% and Canada 7%, total 51%), when combined with the EU and UK, scholars based in the Euro-West account for 91% of all the publications that are cited. Of the remaining 9% of the ‘others’ of humanity that are included, 4% are based in Australia, leaving 5% of the references to the remainder of humanity – the vast majority of humanity we might emphasize. As Samir Amin (Citation2015) has noted, the majority, 85% of humanity, is made into a minority. Of the 984 references, only 16 readings had first authors based in Africa (1.6%). outlines the exact countries where ‘everyone else’ was based.

Table 1. Representation of the majority of humanity, country and # of first authors

Compared to the course readings from the twelve universities we analyzed, the source material used by O’Brien and Williams (Citation2020) has a higher percentage of female first authors in their bibliography. Given that there has been a historical gendered bias in the production of knowledge we analyzed the data by decade to see how these dynamics have changed over time (). In sum: we do find that historical gendered biases are strong, with materials published before 1970 being almost entirely written by male scholars based in the Euro-West, while female scholarship increased in the four decades that followed to a peak of 38% in the 2000–2010 decade, and then declined in the most recent decade.

Barriers to decolonizing curricula

The hierarchy of knowledge production power influences and shapes (via metrics and dissemination; see: Chen & Chan, Citation2021; Larivière, Haustein, & Mongeon, Citation2015; Posada & Chen, Citation2018) what is considered as 'authentic' knowledge and what is passed on to students as 'exemplary' scholarship. This poses challenges for the decolonization of knowledge, and specifically in the teaching and learning of IPE. Despite critiques contesting such trends (Mbembe, Citation2001), decades have passed and the knowledge produced continues to be dominated by articles and books written by scholars in the Euro-West (e.g. Medie & Kang, Citation2018). Materials in these archives that exihibt such biases are privileged over and above materials produced by scholars based in the majority of nations, and indeed that produced by the majority of humanity. One might suggest this is an issue of accessibility; however, many university libraries in the Euro-West have acquired books and articles written by scholars based around the world, and yet our findings show that these hardly make it onto the reading lists of courses nor are they used as source material for textbooks.

Another challenge in the knowledge production system is that the ‘top’ journals of IPE are primarily located in the Euro-West. This location affects the level of access that scholars from around the world have in publishing in these journals (in several ways, such as being on editorial boards, as peer reviewers, as readers barred by gated access). In addition to barriers in the processes of participation, another reason for the difficulty of contributing to these journals is the prioritizations of methodological approaches; on this, Emmons and Moravcsik (Citation2020) refer to a disciplinary crisis in political science graduate training. Using case studies from several top universities, they argue that quantitative methods are preferred above qualitative methods. Due to the continued coloniality of relationships between the researcher and the researched, and who is able to claim authorship and ownership of data and published products, scholars based in the Global South tend to be at a disadvantage compared to those in the Euro-West when it comes to having sufficient funding to conduct national or multi-national research projects. Due to these power asymmetries, it is doubly challenging for scholars based in the Global South to be lead authors and publish in the so-called ‘top tier’ journals of IPE. More broadly, the emphasis on quantitative approaches in development economics became something of an article of faith from the 1950s when economics itself became embedded in 'rational' thoughts and methods, when firm level analysis was transposed to macroeconomic analysis (Fine, Citation2009). The cost barrier increased further with the ‘gold standard’ of random control trial research, studies often costing millions of dollars. The methodological prioritizations that underpin mainstream economics have found their way into IPE. Although these approaches have merit, its increasing hegemony in determining the quality of an article makes it increasingly difficult for scholars who are not grounded in quantitative analysis to be able to publish in the top journals. Yet, for economics and IPE to make sense and sufficiently grapple with the challenges that neoliberalism has brought on the global economy, an interdisciplinary approach is required that incorporates not only politics, but sociology, anthropology, psychology, and culture, among others. Thus, disciplinary pluralism and methodological democratization are required to ensure that articles based on qualitative research from scholars based around the world are also accepted and published in 'top' IPE journals.

Related to these methodological turns, IPE is comparatively less taught in universities in the Global South. The neoliberal inspired reforms of the 1980s and the rationalizations that followed (see Mamdani, Citation2007) created conditions in which departments were merged. In this process, economics as a discipline took ascendancy, with little or no space for the teaching of IPE Fine (Citation2009, p. 886) describes this phenomenon thus:

First and foremost, as a discipline, mainstream economics is increasingly subject to an esoteric and intellectually bankrupt technicism that is absolutely intolerant of alternatives and only allows for them to survive on its margins. The technical apparatus that this involves, utility and production functions, are well-known to students of economics at every level of the discipline, as is the methodological focus of relying upon optimising individuals in single-minded pursuit of self-interest, embedded within formal mathematical models centred on (deviations from) efficiency and equilibrium, and reputedly tested against the evidence statistically through econometrics. Despite its considerable and longstanding methodological and theoretical fragilities, especially from the perspectives of other social sciences, there is no sign that this situation of mono-economic dominance within the discipline is liable to change as a result of internally or externally generated critique. Indeed, mainstream economics continues to strengthen its stranglehold through research, publications and training with Americanisation to the fore

Fine further notes that the mathematical turn in economics ‘involves an extraordinary reductionism of the social to informational or market imperfections and pursuit of self-interest, while also providing considerable scope for inscribing (bringing back in) the social by plunder of concepts and insights from other social sciences (ranging from trust and customs to institutions, etc.)’ (Fine, Citation2009, p. 887).

Yet another challenge identified in our analysis is that universities around the world heavily rely on materials and textbooks from the Euro-West. This reinforces the coloniality of knowledge for several reasons. University faculty and administrators still believe (and perpetuate the idea that) the Euro-West is the source of authentic knowledge. Thus, even when scholars publish papers in national or regional publishing houses, these may not make it to the reading lists. We have thus far outlined the pedagogical problem; however, what is learned in IPE does not only affect the individuals influenced by it, amongst a wide range of professions, graduates of IPE programs inform and draft policy. When the privileging and silencing found in the IPE training is weaved into policy, the asymmetries and systemic epistemicide take new forms. We explore counters to the status quo in what follows, albeit this remains an exploratory process to which we invite others to contribute.

Ways forward for IPE and its engagement with policy

It has long been recognised that IPE, like many other disciplines, has been decidedly Eurocentric in content and outlook (Ake, Citation1979). Despite several calls for decolonization of the curricula, IPE continues to be dominated by male voices based in the Euro-West. The dominance of perspectives from the Euro-West reinforces what Robert Wade (Citation2013) refers to as an art of power maintenance. Wade made this reference in relation to the maintenance of the exploitative global capitalist systems and institutions that continue to protect and privilege the interests of western countries, which is one of many areas where IPE meets policy. Basking in the benefits derived from the long durée of exploitation through imperialism and colonialism, actors in the Euro-West (largely private sector, for-profit companies) have amassed vast resources (financial as well as repositories of knowledge) that allow them not only to control knowledge flows and constitute what is considered ‘authentic’ knowledge (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Citation2014, Citation2018) but also to influence policy making. Political financing and threats to withdraw funding from intergovernmental institutions are but two of many potential examples. Less explored, however, is how the knowledge base of decision makers is critical to sustaining the entrenched domination. Although critical IPE scholars have pointed out the limitations of the neoliberal market, the ideas have predominated. The historical components of the IPE curricula reflect the views of western scholars, some of whom justified colonialism as beneficial to the colonised societies (whose work we choose not to cite, lest the metrics of knowledge production acknowledge these contributions as positive). We posit that it is not coincidental that it is from the same geographies that benefited from colonization where arguments are made are pointing to its supposed benefits. Despite critiques against the organization of the global economy (Amin, Citation1997; Chang, Citation2008; Polanyi, Citation2001; Stiglitz, Citation2002), the hegemonic global knowledge industry is still underpinned by the idea that there is no alternative to the market or free trade (Bhagwati, Citation2007; Friedman, Citation1999). We posit that it is not coincidental that it is the same Euro-Western nations that engaged in protectionism in their own history are the ones now necessitating market liberalization for everyone else today (as per Chang, Citation2002, Citation2008). Appropriate, responsive and proactive policymaking is rooted in situated and contextualized knowledge; however, IPE graduates are only obtaining knowledge that is useful for, or in service of, the Euro-West. The preponderance of this thought in IPE and the deleterious effects that they have in the development processes of countries around the world necessitates a change in the foundation of IPE knowledge and its practice. Examples of the negative impacts of such a narrow, Euro-Western oriented training, include repeated policy failures and the inability to address localized systemic challenges (e.g. in the economic, political, environmental and social realms).

The way forward for IPE, and in its engagement with policy, requires us to move beyond the rhetoric and tokenism of decolonization. This will take a diversity of forms. As it relates to decentering and recentering within the production of knowledge, this requires a democratization of knowledge production and accessibility. For IPE as an academic field, we mean publicly owned knowledge that is available for all to read and contribute to; not Open Access that shifts the burden of costs from readers to authors, channeling funding to publishers in innovative ways while creating new barriers for participation for those without access to financial privilege. We do not have a specific vision for what this should look like or how it should operate; however, the emergence of new platforms and the development of fully Open Access journals, run by public universities around the world, are positive signs of ongoing transformations. We are also encouraged by new journals publishing in a diversity of languages. For IPE in its engagement with policy we mean democratization of power, as in international financial institutions, the security council, amongst others, that are reflective of today’s realities, not that of the post WWII period. We view the continuation of the status quo in these two apparently disconnected realms as inherently connected, and thereby disruptions in one will enable transformations in another.

At the theoretical and epistemological levels, the transformations must be in content, as well as in form. This consists in the reconstitution of the international to reflect different regions of the world, as it should, rather than the current centering of Euro-Western knowledge as the authentic knowledge to which all must subscribe. For global governance, this has direct implications. For example, it seems to be taken as truth that Sub-Saharan African and the Middle East and North Africa are ‘regions’ that are grouped logically. All indications suggest otherwise. The dominance of market fundamentalism in much of IPE scholarship from the Euro-West is another of many such examples, which influence graduates of IPE to orient decision-making in a certain way, which may not be in the best interests of their own nation or people. The colonial framing and logic taught in IPE are continued in policy, without critical reflection. The connections alluded to above are tied to the serial policy failures experienced in the Global South, as well as in the Global North. From the Washington Consensus to the Structural Adjustment Programs, and austerity measures both in the Global North and South, policy advice based on market fundamentalist ideas have not yielded the much-touted development outcomes that the protagonists predicted (see, Blyth Citation2013, Stiglitz, Citation2002). The failure of these policy prescriptions point to the need to rethink the teaching and the curricula of IPE.

The way forward for IPE involves moving from universalism – as if there is only one knowledge base – to pluriversalism. This translates as a greater recognition and integration of other knowledges to the design of publications, and in the curricula and the teaching of IPE. In order for this to happen, Wallerstein’s idea of unthinking social sciences is fundamental (Wallerstein, Citation2001). In other words, universities must make conscious efforts to acknowledge the dominance of Eurocentric knowledge and make systemic changes that recognise the plurality of knowledges on the key components of IPE, such as development, international institutions, global finance, migration, trade, finance, intellectual property rights and so on. All of these topic areas have policy implications that will be transformed as the status quo of knowledge in IPE is disrupted. We do not think substantive change can be achieved through quotas or percentage mandates, as this may encourage continued tokenism. However, regular reviews of curricula, as we have done, might be internal institutional practices to assess if exclusions are persisting, and in what form. We have heard many scholars argue something along the lines that ‘they cannot teach what they do not know’. This seems a pathetic and unacceptable response for those employed in an institution of learning; nonetheless, institutions might be more proactive in mandating training (as is done with many other areas of academic life, alongside individualized assessments and guidance). As Ndlovu-Gatsheni (Citation2018) had noted, we cannot only focus on the products of IPE education, but also the producers of it.

All of the above must be framed within the context of decolonial thought, which has so forcefully brought into fore the continuity of colonial structures of power, being and knowledge. Decolonial thought takes as its point of departure that the claim to Euro-Western modernity does not exist in isolation of coloniality (see Icaza, Citation2017; Mignolo, Citation2013). Decolonial thinkers challenge the locus of enunciation of a particular knowledge in relation to social realities. According to Icaza (Citation2017, p. 1) ‘the locus of enunciation means that hegemonic histories of modernity as a product of the [European] Renaissance or the Industrial Revolution are not accepted but challenged to undo Eurocentric power projection inherent to them’. Implicit in decolonial thought is border thinking. Citing Mignolo (Citation2013), Icaza (Citation2017) argues that 'border thinking is an epistemological position, which exposes the violence of the dominant epistemology grounded in abstract universality as a ‘zero point’ of observation and of knowledge seen as disdainful by all other perspectives and forms of knowing’. Border thinking is also seen as a ‘fracture of the zero-point’ and as a possibility for a critical re-thinking of the geo and body politics of the modern/colonial foundations of political economy analysis and of gender’ (2018: 2). Thus, in addressing the asymmetries of IPE, which we have shown in curricula and textbooks, it is imperative for universities around the world to find creative ways to enable the recentering of more diverse voices and perspectives. As we have noted, the implications here are not bound by the university and its participants, we cannot lose sight that those encultured within these institutions are members of society. Within IPE, many graduates move into the political and economic decision-making realms directly influencing policy. This is particularly important when one considers the interconnection of knowledge production to the global economy and how knowledge of IPE continues to shape that relationship. The crisis of global capitalism, which Harvey (Citation2014) creatively identified, has created uncertainties and inequalities, which were borne even more clear with the ongoing global pandemic. Much as political economy has become important in addressing the crisis of capitalism at the domestic level through recentering the role of the state in redistribution (see Hobson Citation2012a; Citation2012b), a plural approach to teaching IPE would go a long way in equipping future leaders and policymakers with the knowledge they require to grasp the complexity of the global economy. Rethinking the foundation of the knowledge of IPE and changing the content of the discipline is critical to enabling policy change in ways that can foster plurality of thoughts and approach to the formulation of policy conceptualizations.

Conclusion

This article sought to move beyond specific analyses of programs, courses, and journals, and attempt to offer an analysis of the broader curricula of IPE. We did so by analyzing the syllabi of IPE courses from 12 universities around the world as well as one of the most widely used textbooks. We situated our study within the unequal power that defines knowledge production, and set forth evaluating where the authors selected for inclusion in syllabi reside as well as where authors reside who were selected as important for providing the source material used in textbooks. We found a continuation of asymmetry of voice that privileges male voices in the Euro-West over the rest. While there have been calls and claims of decolonization, we find a continuation of a Euro-Western male voice that should make us all uncomfortable in our reflexivity. In a practice that dates to the colonial conquest of many of the countries in the Global South, during which denialism of history and knowledges was made part of the strategies of domination and control, epistemological subjugation, silences and otherizing continue to define the teaching of IPE. Based upon this finding, we reflect upon what those trained with this education go on to do, and specifically in influencing and making policy. Given the interconnectedness of the global economy, the crisis of global capitalism and the current turn in epistemic disobedience, we conclude that the teaching of IPE needs to move beyond tokenism lest it foster its own irrelevancy. In our exploration of ways forward, we look to emerging trends but avoid ‘recommendations’ that might appear dictatorial about how transformation of power and systems of knowledge production can occur. We put forth ideas for consideration and keenly look forward to seeing more disruptive options continue to emerge. We argue that the colonial framing given in IPE training is directly connected to the policies entrenching power asymmetries. However, due to the engagements between IPE and policy, we view that disruptions have the potential to foster transformations across the spaces where IPE and policy meet.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Logan Cochrane

Logan Cochrane is an Associate Professor in the College of Public Policy at HBKU. His research includes diverse geographic and disciplinary foci, covering broad thematic areas of food security, climate change, social justice and governance. For the last 15 years, he has worked in non-governmental organizations internationally, including in Afghanistan, Benin, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Egypt, Ethiopia, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, South Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda.

Samuel O. Oloruntoba

Samuel Ojo Oloruntoba is an Adjunct Research Professor at the Institute of African Studies, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, and an Honorary Professor at the Thabo Mbeki School of Public and International Affairs, University of South Africa. He is also a Faculty Associate at the African School of Governance and Policy Studies. He obtained Ph.D. in Political Science from the University of Lagos, Nigeria. He was previously a Visiting Scholar at the Program of African Studies, Northwestern University, Evanston, and a Fellow of Brown International Advanced Research Institute, Brown University, Rhode Island, United States of America. Oloruntoba is the author, editor, and co-editor of several books including Regionalism and Integration in Africa: EU-ACP Economic Partnership Agreements and Euro-Nigeria Relations, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, USA, 2016 and co-editor with Toyin Falola of the Palgrave Handbook of African Political Economy, 2020. His research interests are in Political Economy of Development in Africa, Regional Integration, Migration, Democracy and Development, Global Governance of Trade and Finance, Politics of Natural Resources Governance, and EU-African Relations.

References

- Afolayan, A., Yacoob-Haliso, O., & Oloruntoba, S. O. (2021). Introduction: Alternative epistemologies and the imperative of an afrocentric mythology. In A. Afolayan, O. Yacoob-Haliso, & S. O. Oloruntoba (Eds.), Pathways to alternative epistemology (pp. 1–16). Cham: Springer.

- Ake, C. (1979). Social science as imperialism: A theory of political development. Ibadan: Ibadan University Press.

- Amin, S. (1976). Unequal development: An essay on the social formations of peripheral capitalism. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Amin, S. (1989). Eurocentrism. Monthly Review Press: New York.

- Amin, S. (1997). Capitalism in the age of globalization: The management of contemporary society. London: Zed.

- Amin, S. (2004). The liberal virus: Permanent war the Americanization of the world. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Amin, S. (2015) The path of development for underdeveloped countries and marxism speech. Accessed 14 April 2021. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F07FgOx7FVc

- Anzaldúa, G. E. (1987). Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco: Aunt Lute.

- Bhagwati, J. (2007). In Defense of Globalization. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bhambra, G. (2007). Bhambra, Gurminder. Rethinking Modernity: Postcolonialism and the sociological imagination. New York: Palgrave.

- Bhambra, G., Gebrial, D., & Nişancıoğlu, K. (2018). De-Colonising the University. Pluto: London.

- Blyth, M. (2013). Austerity. The history of a dangerous idea. Oxford University Press: Oxford

- Cabral, A. (1977). Resistance and Decolonization. Rowman & Littlefield: London.

- Chang, H. (2002). Kicking away the ladder: Development strategy in historical perspective. London: Anthem Press.

- Chang, H. (2008). Bad Samaritans: The myth of free trade and the secret history of capitalism. London: Bloomsbury.

- Chen, G., & Chan, L. (2021). University rankings and governance by metrics and algorithms. Zenodo. doi:https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4730593

- Chigudu, S. (2021) Colonialism had never really ended': my life in the shadow of Cecil Rhodes. Accessed 25 May 2021 https://www.theguardian.com/news/2021/jan/14/rhodes-must-fall-oxford-colonialism-zimbabwe-simukai-chigudu

- Dabashi, H. (2015). Can non-Europeans think? London: Zed.

- Emmons, C. V., & Moravcsik, A. M. (2020). Graduate Qualitative Methods Training in Political science: A disciplinary crisis. PS: Political Science & Politics, 53(2), 258–264.

- Eze, E. C. (2008). On reason: Rationality in a world of cultural conflict and racism. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Fanon, F. (1952). Black skin, white masks. New York: Grove.

- Fanon, F. (1963). The wretched of the earth. Grove: New York.

- Fanon, F. (1964). Toward the African revolution. Grove: New York.

- Fine, B. (2009). Development as zombieconomics in the age of neoliberalism. Third World Quarterly, 30(5), 885–904.

- Friedman, T. (1999). The lexus and the olive tree: Understanding globalization. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

- Grosfoguel, R. (2007). The epistemic decolonial turn. Cultural Studies, 21(2–3), 211–223.

- Grosfoguel, R. (2011). Decolonizing post-colonial studies and paradigms of political-economy: Transmodernity, decolonial thinking, and global coloniality. Transmodernity: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World, 1(1), 1–38.

- Grosfoguel, R. (2013). The structure of knowledge in westernized universities – epistemic racism/sexism and the four genocides/epistemicides of the long 16th century. Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge, 11(1), 73–90.

- Hall, B. L., & Tandon, R. (2017). Decolonization of KNOWLEDGE, EPISTEMICIDE, PARTICIPATORY RESEARCH AND HIGHER EDUCAtion’. Research for All, 1(1), 6–19.

- Harvey, D. (2014). Seventeen Contradictions and the End of Capitalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hobson, C. (2012a). Liberal democracy and beyond: Extending the sequencing debate. International Political Science Review, 33(4), 441–454.

- Hobson, J. M. (2012b). The eurocentric conception of world politics: Western international theory 1760-2010. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hobson, J. M. (2013). Part 1 – revealing the eurocentric foundations of IPE: A critical historiography of discipline from the classical to the modern era. Review of International Political Economy, 20(5), 1024–1054.

- Icaza, R. (2017) Border thinking and vulnerability as a knowing otherwise, e-International relations. accessed May 3, 2021. available at: https://www.e-ir.info/2017/06/09/border-thinking-and-vulnerability-as-a-knowing-otherwise/

- Larivière, V., Haustein, S., & Mongeon, P. (2015). The oligopoly of academic publishers in the digital era. PLoS One, 10(6), 6.

- Mamdani, M. (2007). Scholars in the marketplace. The dilemmas of neo-liberal reform at Makerere University, 1989–2005. CODESRIA: Dakar.

- Mantz, F. (2019). Decolonizing the IPE syllabus: Eurocentrism and the coloniality of knowledge in International political economy. Review of International Political Economy, 26(6), 1361–1378.

- Mbembe, A. (2001). On the postcolony. University of California Press: Berkeley.

- Mbembe, A. (2013). Critique of black reason. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Mbembe, A. (2016). original, 2019 translation). Necropolitics. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Medie, P., & Kang, A. J. (2018). Power, knowledge and the politics of gender in the global south. European Journal of Politics and Gender, 1(1), 37–53.

- Mignolo, W. (2000). Local histories/global designs: Coloniality, subaltern knowledges, and border thinking. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Mignolo, W. (2003). The darker side of the renaissance: Literacy, territoriality, and colonization. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Mignolo, W. (2011a). Geopolitics of sensing and knowing: On (de)coloniality, border thinking and epistemic disobedience. Postcolonial Studies, 14(3), 273–283.

- Mignolo, W. (2011b). The darker side of western modernity: Global futures, decolonial options. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Mignolo, W. (2013). Dewesternization, rewesternization and decoloniality: The racial distribution of capital and knowledge, public lecture at the centre for the humanities. University of Utrecht, May 13.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. (2014). Global coloniality and the challenges of creating African futures. Strategic Review for Southern Africa, 36(2), 181–2002.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. (2015a). Empire, global coloniality and African subjectivity. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. (2015b). Genealogies of coloniality and implications for Africa’s development. Africa Development, 40(3), 13–40.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. (2018). Epistemic freedom in Africa – deprovincialization and decolonization. London: Routledge.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. (2021). The afterlives of racial slavery in global coloniality. Cambridge legacies of enslavement inquiry and the centre for African studies seminar series. University of Cambridge, United Kingdom, 17(May), 2021.

- Nkrumah, K. (1968). Handbook of revolutionary warfare. PANAF: London.

- Nkrumah, K. (1970). Class struggle in Africa. PANAF: London.

- Nkrumah, K. (1973). The Struggle Continues. PANAF: London.

- O’Brien, R., & Williams, M. (2020). Global political economy: Evolution and dynamics (6th ed.). London: Macmillan.

- Oloruntoba, S. O., & Falola, T. (2020). The palgrave handbook of African political economy. Palgrave: New York.

- Phillips, N. (Ed). (2005). Globalizing International political economy. Palgrave: New York.

- Polanyi, K. (2001). The great transformation: The political and economic origin of our time (2nd ed.). Boston: Beacon Press.

- Posada, A., & Chen, G. (2018). Inequality in knowledge production: The integration of academic infrastructure by big publishers. ELPUB 2018. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01816707/

- Quijano, A. (2000). Coloniality of power, eurocentrism, and Latin America. Nepantla: Views from the South, 1(3), 533–580.

- Said, E. (1979). Orientalism. Pantheon: New York.

- Stiglitz, J. (2002). Globalization and its Discontent. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

- Taylor, I. (2005). Globalisation studies and the developing world: Making international political economy truly global. Third World Quarterly, 26(7), 1025–1042.

- Thiong’o, N. (1986). Decolonizing the mind. James Currey: London.

- Thiong’o, N. (1993). Moving the Centre: The Struggle for Cultural Freedom. London: James Currey.

- Thiong’o, N. (2012). Globalectics. Columbia University Press: New York.

- Vogel, C. (2021) Colonial frameworks: Networks of political and economic order. Accessed 25 May 2021 https://roape.net/2021/05/11/colonial-frameworks-networks-of-political-and-economic-order/

- Wade, R. (2013). The Art of Power Maintenance. Challenge, 56(1), 5–39.

- Wallerstein, I. (2001). Unthinking social science: The limits of nineteenth-century paradigms. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

- Zondi, S. (2018). Decolonising International relations and its theory: A critical conceptual meditation. Politikon, 45(1), 16–31.