ABSTRACT

This study focused on the Japanese cyber-fandom of Thai boys’ love (BL) dramas, examining how their perception of Thailand was transformed through viewership and participation in fandom activities and how it affected the fans themselves and the broader Japanese society. In the Japanese cyberfandom of Thai BL dramas, people with diverse gender identities and sexualities intermingle, learn, and become aware of their changing gazes toward Thai and Japanese culture, queerness, and other related issues. Through a qualitative analysis of audience ethnography and interviews with 25 participants, this study shows that Thailand’s culture contrasts with others, particularly the cultures of the West, and an Oriental gaze from the Japanese point of view has emerged in this context. A movement beyond the national Thailand–Japan framework has also emerged, which explores the multifaceted nature of BL dramas within a single-issue context. Thus, Thai BL drama fandom extends beyond an Oriental perspective, practising inter-Asian referencing and reflecting on the national framework by watching BL dramas and participating in fandom. In other words, this study presents new possibilities for BL: (1) overcoming an oriental perspective and reflecting on a national framework for the acceptance and consumption of BL content and (2) cultural experience and real social connection through fandom activities and discourse through inter-Asian referencing in practice.

Introduction

This exploratory study used inter-Asia referencing (Chen Citation2012; Takeuchi Citation2005) to analyse how Japanese fans of Thai boys’ love (BL) dramas perceive and accept them along with other fans and Japanese mass media. Fandoms of non-U.S. and non-English cultures have created a bottom-up contra-flow to U.S.-centric popular culture (Thussu Citation2007), leading cultural trends originating in twenty-first-century Asia to spread globally through social media, creating a de-Westernisation of global media markets (Iwabuchi Citation2002; Kim Citation2008). One such transnational artifact of popular culture recently has been Thai BL dramas.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a key impact on the functioning of cultural markets and the global flow of digital cultural content due to global streaming platforms, which display a more abundant and affordable range of cultural goods and wider accessibility of cultural content (Vlassis Citation2021). Bolstered by the pandemic, both creators and audiences have rapidly pivoted for digital means of creation and distribution (Jeannotte Citation2021). The audience’s participation in developing content and material for entertainment has increased, and one of the fast-expanding genres of entertainment is that of “boys’ love” (Abueg Citation2021). In Japan, a Thai BL drama fandom known as tai-numaFootnote1 emerged during COVID-19 pandemic. The popular Thai production company GMMTV’s drama 2gether was watched globally on YouTube and ranked first in global trends on X (Twitter) in 2020 (Hori Citation2020b). When the Japanese government encouraged social restrictions during the initial expansion of the pandemic, people had more time to watch online dramas and commit to cyber fandoms, such as tai-numa. The fanbase expanded rapidly through the use of hashtags, allowing people to share their thoughts (Shimauchi Citation2023a), and this communal experience reinforced social capital (including trust and belonging) and cultural capital (including personal empowerment and quality of life; Jeannotte Citation2021).

Thai BL dramas have become increasingly popular recently. Over 30,000 people visited the GMMTV exhibition featuring Thai BL dramas organised by TV Asahi, which toured major cities across Japan. Thai BL dramas were the most streamed content in the annual overall ranking of the video distribution service Rakuten TV (Nihon Keizai Shimbun Citation2022). Numerous magazines specialising in Thai dramas and actors have been published and dozens of fan meetings with BL drama actors have been held in Japan after the spread of COVID-19 infection has calmed down.

In Japanese popular culture, BL is a genre that centres on the romantic relationships between handsome male youths known as bishōnen (McLelland and Welker Citation2015, 3), and it is originally designed for heterosexual female audience. The cultural creation of BL has a long history in Japan, spanning manga, anime, light novels, films, dramas, fan fiction, and other cultural products. Scholars have argued that such BL liberates audiences from traditional values in Japanese society, such as patriarchy, gender dualism, and heteronormativity (Hori and Mori Citation2020; Welker Citation2006; Citation2019).

Beyond Japan, however, BL fandoms are situated in specific cultural, historical, and geographical contexts and should be interpreted differently. Japanese BL manga has become increasingly popular among young middle-class Thai women since the late 1990s (Keenapan Citation2001). Baudinette (Citation2019) analyses Thai BL dramas—usually called Series Y (wai)—to “hybridize Thai understandings of sex and gender with explicitly Japanese models of reading same-sex attraction to create a ‘glocalized’ code that is becoming increasingly influential” (Baudinette Citation2019, 116).

Similarly, Thai BL dramas that emerged in the 2010s are also accepted and interpreted differently depending on the cultural context. Shi (Citation2020) discusses the recent popularity of Thai BL dramas in China as a result of Chinese restrictions on South Korean cultural products and their distribution through global platforms (e.g. YouTube) and the cheap import price of Thai BL dramas. Jirattikorn (Citation2021) argues that Chinese audiences perceive Thai BL dramas as a nostalgic foreign “Other” and enjoy their exotic image. Baudinette (Citation2020) asserted that Thai BL is an empowering space for gay Filipino men to explore their same-sex desires. Ho (Citation2022) states that, unlike Japanese BL fans, Southeast Asian BL fans tend to associate the male homoerotic relations they encounter in BL media with their real-life sexual desires.

At this point, the transnational cultural flow from Thailand to Japan is a novel phenomenon, and only a few studies cover the Japanese audience’s perception of Thai BL media (e.g. Baudinette Citation2023; Shimauchi Citation2023a). This study critically examined the context in which Thai BL is transnationally accepted in Japan using inter-Asian referencing and Oriental Orientalism as a framework of analysis.

Inter-Asia referencing and orientalist consideration for approaching Thai BL culture

Cultural exchanges across Asia have involved asymmetrical supply and demand (Chua Citation2004; Chua and Iwabuchi Citation2008). The region’s uneven cultural flows rely on Asian languages and cultures as historical entities with colonial backgrounds, as well as unequal political and economic power (Yoshimi Citation2011). The failure to move beyond a Western versus non-Western framework in analyses of cultural hybridisation has created the need to analyse the dynamic aspects of cultural traffic (Iwabuchi Citation2016). Chen (Citation2012) theorises that late developing countries including Japan embody a binary mindset in confronting Euro-America, and this attitude of “catching up” represses objective analysis (Chen Citation2012, 322).

Yoshimi (Citation2011) argued that, since the 1980s, East Asia has changed from a society in which only Japan enjoyed postwar prosperity to one in which this affluence has spread to the entire region, and a new form of cultural consumption has formed between Asian mega-cities. Japan’s history of imperialism, colonialism, and economic exploitation is closely related to imbalanced relationships and cultural flows, which have been generally accepted as a one-way expansion of popular Japanese culture in Southeast Asia.

Furthermore, Japan had maintained its dominance in Asia by accepting Western hegemony. Iwabuchi elaborated on the developmental time gap between Japan and the rest of Asia because Japan deliberately isolated itself from other Asian countries (Iwabuchi Citation2016, 236). He describes a self-perception of Japan being “similar but superior” and “in but above Asia” (Iwabuchi Citation2016, 10).

Historically, Japan’s perception of Asia has been based on a persistent form of thinking and preconception that it was the only country to modernise. Although Japan is located in Asia, it has been inclined toward a vision of “Asia and Japan,” rather than “Japan within Asia,” and has emphasised Japan’s uniqueness with respect to Asia and its differentiation from the rest of Asia (Namiki Citation2008). Takeuchi (Citation1993) says that Japan, which invaded and occupied Asia through colonialism, lost its proactive attitude toward Asia as soon as it lost the war and began to ally far away from Japan (Takeuchi Citation1993). Iwabuchi and Shimauchi (Citation2023) discussed Japanese attitudes toward Asia, classifying them into two categories: (i) a sense of superiority and (ii) pan-Asianism and paternalism. In addition to a sense of superiority by examining Asia, the idea of Japan as a leader in Asia was used to justify the prewar invasion of Asia. Orientalism, once explained by Said ([Citation1978] Citation1994, 1) as “a way of coming to terms with the Orient that is based on the Orient’s special place in European Western experience” and understood as the “West’s skewed self-projection upon the East” (Rath Citation2004, 344) is also applicable in Japan. Although Japan is geographically located in the Orient, the Japanese people tend to objectify Asia, which we can call Oriental Orientalism (Iwabuchi Citation2016, 9) or Mass Orientalism (Kawamura Citation1993). Similarly, Kim (Citation2020, 244) found that Japanese BL fans undeniably hold Orientalist and racist fantasies that reflect the consciousness of Japanese society.

To examine the forces at work and the perceptions and practices produced when Japanese fans of Thai BL dramas observe BL dramas as Asian others in contemporary society, this study employed Asia as the method and inter-Asia referencing as the analytical framework. Japanese Sinologist Yoshimi Takeuchi first conceived of Asia as a method, which was further elaborated by Kuan-Hsing Chen (Citation2010) in his seminal work. Chen (Citation2010) explains that “using the idea of Asia as an imaginary anchoring point, societies in Asia can become each other’s points of reference, so that the understanding of the self may be transformed, and subjectivity rebuilt” (Chen Citation2010, 212). Asia denotes that the culture of one’s own country (in this study, Japan) is seen from an Asian perspective (in this study, Thailand).

Traditionally, Asian intellectuals have used the West unreflectively (Anderson Citation2012). However, Japan has its own mass culture studies, which started focusing on the grassroots movement in popular culture before Western academia began to discuss participatory culture. Since the end of the Asia-Pacific War, in Japan, the Shisou no Kagaku (Science of Thought) Study Group led by Tsurumi Shunsuke and others had been interested in the everyday practices and mentalities of those who reinterpreted mass media texts and rewrote them in their journals published between 1946 and 1996; in this practice, they found an active and cultural fundamental power (Tsurumi Citation1999). Moreover, in various contemporary cultural domains, the internet is home to grassroots movements in which new ideas and communal formations beyond national frameworks are realised (Hirota Citation2018, 207). Previous studies on the fandoms of BL dramas and manga have shown that countercultures to national discourses are generated through fan interaction and cultural production (Chang and Tian Citation2021), as well as non-essentialist understandings of national culture (Turner Citation2016) and subcultural resistance to hegemonic heterosexuality (Wood Citation2013).

While focusing on the exchange and practical activities of tai-numa, this study examines how fans perceived and understood BL dramas from Thailand through viewership and participation in fandom activities, how their gaze on Thailand was perceived and transformed, and how it changed the views of Japan’s broader society and fans themselves in the process of inter-Asian referencing.

Research methods

In this study, the author takes the stance of an acafan who self-identifies as a member of an academic community and a fandom, treating the subculture as part of their scholarly work (Jenkins Citation2011). Acafans can facilitate relationships with other fans as insiders by demonstrating their commitment to the culture under study (Lee Citation2021). The author engages in research, both emotionally (as a fan) and academically, by conducting interviews and scholarly analyses (Hellekson Citation2011). Simultaneously, the author aims to explore the potential of transcultural fandom as a movement for social change, while extending the meaning of “crossing borders” to include cultures and those who transnationally consume, accept, and practise culture daily.

The methods employed included audience ethnography through qualitative research with participant observation and interviews (Fujita and Kitamura Citation2013). Fans are not simply consumers of media and content but also creative beings who produce meaning, interpret cultural texts, and create communities (Fiske Citation2002; Jenkins Citation2021). In this sense, fans are not only active and diverse interpreters of culture but also proactive creators or dissenters of cultural hegemony.

Ethnographic and qualitative research provide detailed descriptions of fans’ modes of media consumption, cultural production, and interpretative communities, considering the broader social context and its impact. This study developed an intimate understanding of this fandom, which is difficult to achieve without interacting with others (Beaulieu Citation2004). Although fan activities were mainly online during the pandemic, fandom activities are also taking place in the real world space in the form of “co-creative” and “spillover effect to others” (Shimauchi Citation2023a). Fandom is a space in which the communication of feelings and thoughts with others is linked to real-world actions and activities in the real world (Baudinette Citation2023; Shimauchi Citation2023b).

The author is Japanese (she/her) with international living and academic experience, and has been participating in Thai BL drama and fandom trends on X (Twitter), Instagram, and other platforms in real time since March 2020, gaining knowledge, participating in online audio interaction, and making observations. She has also participated in dozens of fan events and live performances in both Thailand and Japan to enjoy emotionally as a fan and to observe more objectively as a scholar.

Twenty-five subjects, all native Japanese speakers (although this does not guarantee that they were all Japanese) recruited through X (Twitter), were interviewed. She was the only interviewer. The interviews were conducted, transcribed into Japanese and translated into English. As many members of cyber-fandoms are anonymous (Dym and Fiesler Citation2020), the author never asked them to share personal details (e.g. real name, age, region of residence, gender, and sexuality) to protect their privacy and feelings of safety, unless they voluntarily disclosed them. However, some indicated their gender identity and/or sexual orientation on their social networking account or showed their queerness or support for LGBTQ+ (e.g. by using the rainbow and/or transgender flag on their account name). Approximately one-fourth of the participants openly showed queerness, whereas others did not specifically define themselves as cisgender or heterosexual women. From the stories they shared in the interviews, their age was presumed to range between 20s and 50s; some were students and others were workers or stay-at-home caretakers. When quoting them, pseudonyms unrelated to their social networking IDs or personal characteristics were used to protect their anonymity.

The interviews were conducted in a closed setting, with permission to record and provide consent for appropriate data management. The subjects were interviewed via Zoom on a first-come, first-serve basis, under the condition that they had been in the tai-numa fandom continuously since 2020. Participants were provided with a summary of the study and questions and were informed that they could stop the interview at any time or request that their data be removed. This study was subjected to an institutional ethics review at the authors’ home institution. A semi-structured interview was conducted from February to November 2022 with a pre-prepared set of questions through which the participants’ experiences were elicited in depth, with questions added and modified during the interview process.

The core questions were the following: (1) How did they perceive and understand BL dramas, Thailand, and fan culture, and what new perspectives, changes in perceptions, and behaviours they experienced? (2) What issues or struggles with whom and what (e.g. fandom members and media) did they face in tai-numa?

In the data analysis, the keywords, concepts, and experiences from the transcripts were organised into codes representing fans’ thoughts and behaviours. To organise and interpret the patterns and themes, previous studies, such as fan and cultural studies, media studies, and cultural sociology were utilised in the discussion.

Analysis and discussion

Disproportionate cultural flows and the oriental gaze

Unlike other Asian countries, Thailand has no colonial history with Japan. These two countries have a long history of exchange spanning 600 years, with close economic ties in bilateral trade. After World War II, Japanese companies expanded into Thailand and currency boycotts occurred in 1972 and 1984 to protest Japan’s pervasiveness. However, this anti-Japanese sentiment subsided amidst the liberalisation of industrial investment, and in 2007, the Japan-Thailand Economic Partnership Agreement was signed (The Japan Society of Thai Studies Citation2009). Thailand has the most historical overseas association with the Japanese (celebrating its 100th anniversary in 2013) and has long been a target of direct Japanese investment (Kakizaki Citation2016; The Japan Society of Thai Studies Citation2009). According to a study examining country-specific high receptivity to 20 foreign countries, Thailand remains the most favoured country in Asia, while the Japanese have a “high West, low East” phenomenon of high receptivity to Western countries (Tanabe Citation2008).

However, the cultural exchanges between Japan and Thailand are uneven. Japanese anime and manga were popular among urban Thai children in the early 1990s, before the Korean Wave began (Tidarat Citation2002). Japanese pop culture, including BL and cuisine, is also popular in Thai society (The Japan Society of Thai Studies Citation2009). In contrast, the reception of Thai popular culture in Japan has been limited. Thai food, Muay Thai kickboxing, and massage culture have been slowly gaining popularity since the 1990s (Kakizaki Citation2016). Even for Thai BL fans in Japan, the infiltration of Thai cultural elements is a recent experience.

Participants described their perceptions of Thailand before joining the tai-numa. Some believed that it was “just another Asian country, a developing country” (Nim) or that “when I said I liked Thai dramas, my friends would say: ‘You mean the ones where they dance a lot?’”Footnote2 (Sandee) and that “I had a monolithic view of Asia” (Ayan). “Orientalism from the West to the East, which lumps the Third World together” (Shioiri Citation2019, 210), is also present when looking at the rest of Asia from Japan. Without a clear outline of Thailand as a cultural and societal entity, it was “totalised as a mental map that was separate from Japan” (Iwabuchi Citation2016, 8).

Kat, for example, stated, “I had never been aware of Thailand before. I had never looked at Asia.” The perception of Asia as a separate entity from Japan is manifested in the form of indifference in comparison with Western cultures as described by Pear, who stated that “I think the centre of culture and its market is in the U.S. and Europe, and my sense of cultural elitism has grown up with so-called Western things. I think I have failed to look at Asia” (Pear).

The perception toward Asia is also reflected in the everyday practice of imagining the Western world as “overseas,” making Thailand/Asia distinctive. The top five subscription-based streaming websites in Japan including Amazon Prime, Netflix, Disney+, Hulu, and U-NEXT, according to a Just Watch streaming chart (3rd quarter, 2022), are good examples of the defaulting of the West in the term “overseas” and the exclusion of Asian countries from the concept. Amazon Prime, U-NEXT, and Hulu use the label Kaigai (meaning “overseas”) to categorise Western products, predominantly from the United States and the United Kingdom, and exclude Asian products. U-NEXT features separate categories called “Hallyu and Asia” from “oversea” dramas, comprising productions from Korea, China, Taiwan, and Thailand productions, while Amazon Prime and Hulu use the labels “Korean Drama” and “Asia” to include Korean and Chinese products, respectively. Netflix uses more accurate labels: “Oubei (Europe and America),” “Korea,” and “Hualiu (China).”

The word “overseas” (kaigai) literally means “all regions and countries other than Japan”; however, as shown above, in Japan, it refers to Western countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom. This resonates with the criticism by Perez (Citation2020) that a gender-neutral generic term is not actually neutual term but is interpreted as referring to men.Footnote3 Similarly, Asia and Asian countries are tagged with the name of the region and country as a category different from “overseas” because the default “overseas” means Western world. This proves that the existence of Asian cultures, which had not been recognised as a category before, is now attracting attention; however, they are being considered different than the default “overseas” existence. This labelling system represents how the Japanese understanding of “overseas” exclusively focuses on the Western world.

Furthermore, whereas Asian culture is mostly reminiscent of Hallyu or Hualiu, Southeast Asian culture is rarely included. Thai cultural productions, including movies such as The Iron Ladies and Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, have attracted attention, but are separate from the recent boom. After the birth of tai-numa, “Thai” is finally becoming a national category visible to Japanese audiences. Fans had a favourable perception of Thailand before joining tai-numa, but this involved a vague perception of Asian others. This perception appears to have encouraged the viewership of Thai BL dramas, as explained by two participants:

I think my reason for being into Thai BL was because I really liked Korean dramas before, but it became too much for me. … because I had made friends in Korea and got to know them better, and with all the problems between Japan and Korea, I could see Korean dramas about me and Japan, so it made me think a lot, and it became hard to watch (Jean).

In previous studies, transnational culture in Asia has often been portrayed as a common Confucian concept or desire of urban dwellers, and the role of commonality has been highlighted during its cultural reception (Iwabuchi Citation2016). However, the fact that there is little understanding of Thailand—a country that seems distant from Japanese fans in language, culture, and politics—cannot be simply explained by cultural proximity. This posits that viewers prefer media products from culturally closer countries and regions. Thai BL content evokes a sense of cultural remoteness that may make fans feel secure and increase their interest in Thai culture. With a vague positive view of Thailand, tai-numa fans in Japan can watch Thai BL dramas as the product of an Asian other without feeling guilty about colonial history or the mind being troubled by shared social and cultural challenges.

Fans encounter a popular Oriental perspective (Kawamura Citation1993) that views Asia as undeveloped, not only through content originating from actors and their agencies, but also through cross-cultural experiences of Thai society and fandoms when discussing cultural encounters and experiences both positively and negatively on social networking sites. According to one participant:

Sometimes, we find cultural differences interesting, not simply because they are different but also because we find them interesting in a teasing way. For example, we find it “funny” to hear about how big the fried chicken at a Thai street stall is, or how money is sent to BL actors as a bouquet of flowers, or how there are lizards walking around the town. I don’t think it’s wrong to be surprised by other cultures, but I think we need to look at whether there is a disdain in the attitude that it’s okay to tease people in a funny way (Kim; emphasis by the author).

These statements, with their nuances of “unexpectedness” and “more than expected,” expose a dismissive perspective on Thai content hidden behind praise, exemplifying benevolent Orientalism. The term “Walking Louvre” to describe a popular Thai actor was initially generated in the tai-numa, and in this sense, fan discourse does not differ from that of the media but demonstrates complicity. Fans, however, also frequently acknowledged lookism and hidden disdain by emphasising handsomeness. One interviewee admitted: “I think that the language is used in a way that would not be said in other Western culture or actors. Thai content in Japan is treated with less care and respect than that in Japan or the West” (Ayan).

Iwabuchi and Shimauchi (Citation2023) identified the “strategy of ignorance” as the reason why Japanese university students do not choose Asian countries as studying abroad destinations. In contrast to students’ knowledge of the West, which leads to their recognition of differences with Japan and their behaviour of wanting to know more, ignorance about Asia was not a reason to want to explore Asia more, but to avoid Asia without showing any overt hostility or clear superiority toward Asia. Japan has imaginaries about Asia, including Thailand, which suggests that Oriental Orientalism (Iwabuchi Citation2016, 9; Kawamura Citation1993) toward Asia remains. Fans’ ignorance about Thailand, which allows them to enjoy cultural production without pressure, is a new type of “strategy of ignorance” by finding different Asian others, but it may also underline the Orientalist gaze toward Thai content.

Discovering and bridging Thai BL drama and the societies

Japan is known as the birthplace of yaoi—content featuring intimate relationships, romance, and sexual love between men (Azuma Citation2015; Hori and Mori Citation2020; Welker Citation2019). The term “boys’ love,” or BL, spread from the late 1990s onwards (Hori and Mori Citation2020) and is recognised as a subcultural and trans-regional formation that has spread across Asia, particularly in Chinese-speaking regions. BL and its localised danmeiFootnote5 culture have challenged mainstream heteronormative narratives (Wong Citation2020; Xu and Yang Citation2013; Ye Citation2022).

However, Japanese BL audiences do not always have such resistant readings. While fans’ experience of BL culture before tai-numa is varied, including those who enjoy “relationship moe” (fascination with relationships) or have been “CP stans” (fans of a particular couple) in K-pop, as well as those who follow Japanese pop idols, athletes and musical actors or have avoided BL culture (Shimauchi Citation2023a). Their preference and fan activities have been “in the closet” in a sense because, according to an interviewee, “[BL interests are] embarrassing” (Sandee); “I used to read BL manga behind my family’s back” (Ice); “I think there was a prejudice that BL was something to be looked at in secret, and I think they internalised it, consuming BL as fantasy” (Miw).

Sato and Ishida’s (Citation2022) report on BL readers and non-readers also found that more than 60% of the women surveyed considered loving BL as something that should be “hidden and enjoyed.” Hori (Citation2020a) also notes that a norm within the fujoshi (women who love BL content) community is to “hide their interests and tastes outside of their peer group.”

During the interviews, tai-numa fans discovered new ways to enjoy BL content in Thai BL dramas. Looking at BL dramas is not simply a process of consuming fantasy; it affects one’s own thoughts and behaviours and extends into contemporary society. Recognition of the Thai BL fan market in consumer society has led to Japanese productions such as live-action BL dramas, special features, and other media content targeting these fans. The fact that it is now acceptable to “publicly” declare one’s love for BL is a major change in Japanese society:

I was attracted to the level of awareness of LGBTQ+ in Thai BL dramas, the lack of prejudice in the drama against homosexuality … that there is a world where people don’t deny that there are people like that and don’t feel bad about it (Jean).

Thai dramas have homosexual couples, and people approve of them as a matter of course. There are still parental objections, but homosexuality is normal; there is no making fun of it among friends. I think that there is still an atmosphere of teasing in Japan (Lian).

The breadth of themes explored by Thai BL dramas—not only regarding same-sex romances—and the diversity of how they are presented facilitate cultural and social understanding for readers of different backgrounds. A interviewee stated:

I think they used the BL framework to create intersectional work. The themes depicted are diverse, for example, what it means for a child born into a family with no money to attend school, poverty, young carers of children, and the social difficulties brought about by sexuality. I was impressed by the fact that it could be offered as an “BL drama” (Ayan).

NOT ME interacted with Thai audiences’ anti-authoritarian sentiments through head-on depictions of marriage equality. The reception of NOT ME was also a testament to the interaction between fans and the industry and the political potential of that interaction, with BL media helping Asian fans rethink LGBTQ+ issues (Prasannam and Chan Citation2023). Not only do dramas convey political messages regarding LGBTQ+ rights and social inequalities, but BL drama fandom has also responded.

The dialogue between activism and the BL industry in Thailand is an important aspect of Thai BL (Prasannam Citation2023), in which fans and audiences play a major role. In Episode 7 of Cutie Pie (2022), a character complains that “the country is not moving forward because there are outdated people who think male-male relationships are wrong,” and their same-sex partner insists that “love is not enough, we need rights and laws to support ourselves.” The episode was watched simultaneously by actors and fans at a cinema in Bangkok as a fan meeting, and the reaction footage is available on YouTube ().Footnote6 Fans in the theatre cheered and clapped in support, and the actors responded. At the Pride Parade in Thailand, many actors from the Thai BL drama were present and supported the event alongside fansFootnote7; watching BL implied facing LGBTQ+ rights.

Figure 1. Reaction to “Cutie Pie” EP7: Fans and actors cheered and applauded in the scene the character said “just love is not enough if there is no right and law to support us.”

By watching these shows, Thai BL drama fans in tai-numa in Japan become aware that Thai BL dramas are connected to real society. The examples seen in the viewing of Thai BL drama presented a new perspective for Japanese BL fans, who used to consume BL drama as something to hide behind or as fiction.

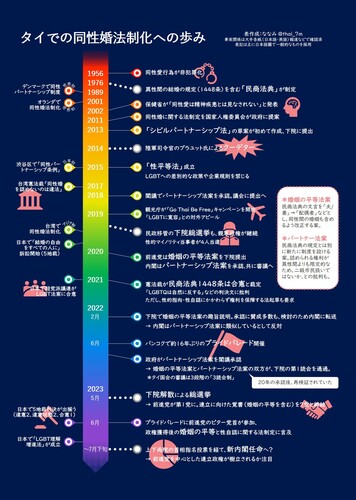

Moreover, watching Thai BL drama leads to a variety of ways to engage in real society by individuals in each of the fandoms, from participating in the Pride March to submitting opinions on the legalisation of same-sex marriage in Japan, expressing opposition to transphobic discrimination, and online activism. Within the fandom of tai-numa, one Japanese BL fan has created a chart comparing Thailand’s progress toward same-sex marriage legislation with the Japanese trend (), and another led online activism using the tag #TaiNumaPrideMonth to express opinions and present creative work regarding Thai BL drama and LGBTQ+, queer and Pride (). These fan behaviours indicate that BL fans became more likely to be open to being BL fans and that their personal preference for BL is directly connected to real-world political issues.

Figure 2. Progress toward the legalisation of same-sex marriage in Thailand: the left-hand side summarises developments related to same-sex marriage in the world, including Japan, and the right-hand side summarises the steps towards legalisation in Thailand. (Source: https://x.com/thai_7m/status/1674336131897520130?s=20 As of 29 June 2023).

Figure 3. “Let's get PRIDE MONTH going in tai-numa!” (Source: https://x.com/niyari_niyari/status/1644687588249473026?s=20 As of 8 April 2023).

Inter-Asia referencing and transformation of Japan(ese)selves

Although tai-numa encompasses various subcultural fandoms, many participants in this study were not originally fans of Japanese BL visual works. One fan who has read Japanese BL comics and fanfiction expressed feeling “distant and uncomfortable” with Japanese BL dramas because of the “strong heteronormative norms, such as the feminisation of one of the characters” (Miw). While many BL dramas have been created in Japan between 2020 and 2022, starring popular Japanese actors, Thai BL dramas and the attitudes of their creators and actors toward BL culture are countinuously interpreted as sincere and diverse compared to Japanese ones. This issue has been discussed from a relative perspective in Japan. Fans may unconsciously employ the lens of inter-Asian referencing, which is evident in how fandoms react to Japanese media coverage of Thai BL content. One interviewee said:

After watching Thai BL dramas and their behind-the-scenes content, I think I have become stricter about the attitude of the production team. My critical activity was directed not only at drama, but also at the directors and the BL industry. What I disliked the most here in Japan was the use of advertising slogans such as “This is not BL” or “It’s beyond BL.” Every time Thai BL fans are angry and seem to be on fire on X (Twitter), they do not receive it at all. This is rude from many perspectives (Way).

In Japanese mass media, expressions such as “love has nothing to do with gender,” “this is universal love that transcends the boundaries of BL” and “normal love that transcends gender” have been frequently used to promote BL productions.Footnote8 In the country where BL content is still something to enjoy in secret, the media is trying to reach a general public who are unaware of BL culture by describing it as relatable “universal” and “normal” love stories. However, Hall (Citation2004) argues that media messages are not always conveyed as intended by the sender, and that meaning is dependent on the social context. Tai-numa fans are more likely to view these expressions negatively, as they may regard these messages as whitewashing same-sex attractions. The discourse that the majority can enjoy BL because it is “universal” and “normal” love, not different from the majority, leads to the assumption of heterosexuality norms being unquestioned and to the bleaching of homosexuality (Shimauchi Citation2023b).

Generally, male Japanese actors starring in BL dramas with mostly female fans are vehicles of heteronormative sexual consumption. Magazines and other mass media in Japan constantly ask questions to male celebrities related to imaginary “girlfriends.” In contrast, Thai BL dramas usually use the gender-neutral term “lovers” when expressing peoples’ love lives. One self-identified queer, a tai-numa fan, felt that they were not included in the fandom of Japanese male idols. When they discovered Thai BL, they said, “I was happy. Like we were not being ignored.” Significantly, this kind of empowerment inspired by content and actors is more common in Thai BL dramas than in Japanese-produced dramas.

Similarly, through being Thai BL drama fans, the initially favourable but vague contours of Thai society become clearer and update the social recognition of Thailand. For instance, when Japanese mass media coverage about Thai BL dramas writes that “Thailand is ‘tolerant’ of LGBTQ+ people,” fans deem these slogans as merely performative pleasantries. A participant stated:

In Thailand, I know that the country is sending out BL dramas, but LGBTQ+ people are not yet fully accepted in the real society. I think that more people, including myself, have become interested in gender, society, and politics by watching Thai BL dramas, and I want to determine exactly what is going on (Win).

Thai BL dramas drive fans to start to learn about politics, culture, and society. One visible change is that the asymmetrical balance of language learners changed after the Thai BL flow in Japan.Footnote9 More than half of the 25 interviewees were learning Thai, and it was observed that online university courses to study Thai are filling up and Thai books are selling well (Sakaguchi Citation2021). If the task of cultural studies is “to understand, share and sympathize with the material and mental conditions of people living in that specific nation” (Chen Citation2012, 218), not only are these activities fulfilling the fans’ fantasies and personal satisfaction, but Thai BL drama provides opportunities to explore new cultures and engage in social activities.

In addition to the attitude toward learning from Thailand in cultural terms, there has also been a transformation in the use of Thailand as a point of inter-Asian referencing in political terms. As of July 2020, when the Democratic movement intensified in Bangkok, there were calls from fans to not use hashtags for dramas and actors because of the clash between citizens and leadership in Thailand. Furthermore, some actors staring KinnPorsche were given the opportunity to interview a gender studies professor on the show’s official YouTube channel.Footnote10 In Japan, people have a strong aversion to political statements by celebrities,Footnote11 so an interviewee stated, “I personally thought that national affairs and subcultures were two different things, so I found it refreshing to use our influence politically” (Ice).

Inter-Asia references to Thai politics by fans occur on issues relating to the social and institutional status of LGBTQ+ people, particularly in relation to BL’s portrayal of homosexuality. According to Chan (Citation2021), Thai society is a “moderate heteropatriarchy,” and the logic of familism with the king as father of the nation supports Thai nationalism. While patriarchal values are strong but not absolute, and Thailand has passed four draft bills on same-sex marriage as of 21 December 2023 (Reuters Citation2023), but this does not mean that discrimination against LGBTQ+ people does not exist in Thailand. Problems of representation exist beyond gender and sexuality, as the people represented by Thai BL dramas are also biased toward portraying the extremely wealthy, and the actors who appear in them are often of Chinese descent.

Nevertheless, Thai BL dramas ranging from depicting queer hardships, such as societal and familial conflict, to promoting marriage equality and equal rights for both queer identities and other minorities give Japanese audiences reference to BL and its politics. For instance, fans employ inter-Asia referencing when they watch Japanese BL dramas Ossan’s Love Returns in comparison with Thai BL series. The series started in 2018 and was one of the fastest-selling BL drama series in Japan. Ossan’s Love Returns, aired in January 2024, depicts the “newly married life” of two men (), but in real life in Japan, same-sex marriage is still not allowed. There is a scene in the drama where a same-sex couple is told that “it’s good enough just to have the blessing of your peers like you guys” even without legal guarantees, and criticism was raised in the fandom that the drama is portrayed in a way that does not challenge heterosexual norms and the current system. One fan criticises the common discourse that BL is fantasy, citing the aforementioned scene in the Thai BL drama Cutie Pie where LGBTQ+ rights and legal support are discussed, and argues that “there are already many works that mention marriage equality in BL drama,”Footnote12 notably Thai BL.

Figure 4. Visual image of the drama Ossan's Love Returns. The headline says: “World, this is Japanese love!” (Source: https://x.com/ossans_love/status/1735664760018890967?s=20 As of 15 December 2023).

Through its transnational cultural content, Thai BL provides a relative perspective on the contours of Japanese and Thai societies and an intersectional space to explore gender, society, and politics through the lens of BL. This suggests that Thailand may transcend the asymmetries of previous cultural and economic exchanges, emerging as an “ideal image in contrast to Japanese society” and existing as a “possible alternative image that is more spiritually uplifting toward self-transformation” (Iwabuchi Citation2016, 298).

Conclusion

Japanese society enthusiastically embraced the United States as a model to emulate and reconstruct the Japanese self through this relationship (Yoshimi Citation2007). As stated in the interviews, the West was the default reference point for examining views on Asia. On this basis, “Oriental Orientalism” (Iwabuchi Citation2016, 9; Kawamura Citation1993), that is, an Oriental-based Japanese gaze (“in but above Asia” mentality) toward Thailand as an imagined national entity still exists.

However, regarding the Thai-Japanese cross-cultural exchange within the tai-numa fandom, this transnational culture does not exist as a counterpart to the West, nor is it under strong Western influence. In tai-numa, BL dramas are analysed and accepted with inter-Asian referencing and a comparison between Thailand and Japan. The fandom experience has also led to a self-reflective reimagination of the national frameworks of Japan and Thailand. Therefore, the transnational cultural reception of Thai BL dramas through tai-numa has been a process of relativisation and reflection in both Thai and Japanese societies.

Japanese youth are not really aware of Asian culture, and its cultural distribution and consumption in Asia are still based on asymmetrical relationships (Ching Citation2021; Iwabuchi and Shimauchi Citation2023). A survey about Japanese people’s awareness of Japan conducted by the NHK Broadcasting Culture Research Institute in 2020 showed that the proportion of respondents who regarded Japan as a first-class country increased in 2013, which is analysed as an increase in self-evaluation of Japan’s science, technology, and culture. However, self-esteem declined between 2013 and 2018 due to the passing of the peak of the Japanese praise boom and a decline in trust in science, technology, and research capabilities. Interestingly, this period was immediately after the second and middle of the third Hallyu boom in Japan, when Korean culture, including KPOP and Korean dramas, became popular in Asian regions, while Cool Japan, the political strategy for the overseas expansion of Japanese culture that started in 2013, began to be reported as a failure. In particular, university students perceive Japan’s standing in the world as declining, as exemplified by its declining population, politics, and failure to respond to the pandemic (Iwabuchi and Shimauchi Citation2023).

As noted earlier, an Orientalist perspective emerged when Thailand was viewed within a transnational framework. However, fans’ experiences of looking beyond national frameworks have focused on multifaceted nature of BL. In Japan, a patriarchal society with limited acceptance of sexual minorities, BL challenges gender and sexuality (Welker Citation2019) and can facilitate the awareness and dissemination of these new ideas. The change in gaze can be attributed to fans’ active engagement with BL content.

In exploring tai-numa from a transnational and transcultural perspective, this study presents new possibilities for BL: (1) overcoming an Oriental perspective and reflecting on a national framework through the consumption of BL content and (2) using inter-Asia referencing to discover Asian others, building bridges between BL narratives and real society, and reflecting on one’s own society seeking for better social and political changes.

The study consisted of observations of fan participation on X (Twitter) and interviews with fans. As an acafan, the researcher has a reflective perspective on the observations and interviews, but it is possible that the critical and reflective view may be a confirmation bias in the first place. There are many fans within the Thai BL fandom who enjoy BL regardless of society, and this study does not deny the diverse ways in which BL is enjoyed. Although this study is limited to an analysis from an acafan perspective and cannot address every aspect, it reflects a part of tai-numa’s dynamic image.

In June 2023, the National Diet of Japan enforced the act to promote LGBTQ+ understanding instead of legalising same-sex marriage, and many tai-numa fans protested on X (Twitter) that the act is not enough to prohibit discrimination toward LGBTQ+. On 14 March 2024, courts in Tokyo and Sapporo ruled the nation's current ban on same-sex marriage was “unconstitutional.” Thus, the author argues for the potential of the consumption of a transnational BL culture to lead to social change because of its democratic, social, and political awareness.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sae Shimauchi

Sae Shimauchi, Ph.D. is an Associate Professor at Tokyo Metropolitan University, International Center. Her expertise lies in the area of internationalisation of higher education and cultural studies. She is particularly interested in the impact of international education and study abroad on students and society, and how transnational popular culture in Asia are transforming people and societies. Her academic publication includes books in Japanese Paradigm Shift on International Student Mobility in East Asia (Toshindo, 2016), Global Studies of Undergraduate Education (Yonezawa, A., Shimauchi, S. and Yoshida, A.,eds. Akashishoten, 2022), the latest articles “Thai Boys Love Drama Fandom as a Transnational and Trans-subcultural Contact Zone in Japan” Continuum 37(3), 381–394 (2023) and “Inter-Asian Perceptions of Studying ‘Abroad’ in Asia: Analysis of Japanese Students’ Discourse” (by Iwabuchi, K., & Shimauchi, S.). Globalisation, Societies and Education, 1–12 (2023).

Notes

1 Tai-numa literally translates as “Thai Swamp” because it is hard to get out (to quit being a fan) once one gets hooked (attracted). This became a self-description of the Thai BL drama fandom.

2 It implies that the interviewee’s friend did not have a particular image about Thai culture; they might confuse them with Indian films, which show lots of dancing.

3 For example, the term otaku (a person extremely knowledgeable about the minute details of a particular hobby) in Japanese, which is included in the Oxford English Dictionary, is used by default to refer to male otaku, while female otaku are tagged as “On-na (female) otaku” (Outani Citation2020). In Japan, there are many other examples such as “science girls.”

4 Johnny and Associates (Johnny’s) was the name of a Japanese entertainment production company but also a generic term for the male idols belonging to the company. The name was changed to STARTO ENTERTAINMENT in October 2023 due to sexual assault issues by its founder, Johnny Kitagawa.

5 Chinese genre of literatures and other fictional media that portrays male–male romance.

6 REACTION CUTIE PIE EP7. It shows the actors, staff and fans in the audience cheering and applauding in the scene described above. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XprGMS1OSwQ&t=1122s (accessed 4 March 2024).

7 List of BL actors that posted about Pride or went to Pride Parade https://www.reddit.com/r/ThaiBL/comments/140se14/list_of_bl_actors_that_posted_about_pride_this/?rdt=52630&onetap_auto=true&one_tap=true (accessed 4 March 2024).

8 The term is also used in various newspaper media and magazines, for example, in the prestigious Galaxy Awards sent by the Broadcast Criticism Roundtable, where the award-winning BL drama work was described as “going beyond BL and being completed as a universal adolescent romantic drama” as a reason for winning the award. https://twitter.com/houkon_jp/status/1524947655641530368?s=20&t=er0sZEpqMx7uokmaZBA3nQ (As of 13 May 2022. Accessed 15 January 2024).

9 “Results of the 2021 survey of Japanese language institutions” (As of 2022. Accessed 11 March 2024) https://www.jpf.go.jp/j/project/japanese/survey/area/country/2022/thailand.html#JISSHI

Den-ichi Thaigo mojibu “Review of the Thai language boom since 2020” https://note.com/thaigo/n/n398cdab9135e (As of 31 July 2023).

10 Video of two actors from KinnPorsche asking the Gender Studies professor at Chulalongkorn University about the issues LGBTQIA+ people face ahead of Pride Month 2022. Be On Cloud, TongSprite X PrideMonth EP1 (2022/6/15). Accessed 24 April 2023. https://youtu.be/p9qLVeN02g0

11 Recently, the actor in the Japanese gay movie Egoist (2023) argued that “legalisation should be hastened, especially with regard to same-sex marriage”; however, it is rare for actors in Japan to speak about political issues. AERA.dot (issued 13 February 2023). Accessed 8 March 2023. https://news.yahoo.co.jp/articles/497876484f32af3b46f117fb8facd26549763827?page=3

12 https://twitter.com/sabon_b_l/status/1745369268013916595?s=20 (as of 11 January 2024).

References

- Abueg, L. C. 2021. “What Can Gender Economics Learn from the Pinoy BL Genre of the Covid-19 Pandemic?” Review of Women’s Studies 31 (1): 35–62.

- Anderson, W. 2012. “Asia as Method in Science and Technology Studies.” East Asian Science, Technology and Society 6 (4): 445–451. https://doi.org/10.1215/18752160-1572849.

- Azuma, S. 東園子. 2015. 宝塚・やおい、愛の読み替え:女性とポピュラーカルチャーの社会学 [Transreading of Takarazuka and Yaoi: Sociology of Women and Popular Culture]. Tokyo: 新曜社 [Shinyosha].

- Baudinette, T. 2019. “Lovesick, The Series: Adapting Japanese ‘Boys Love’ to Thailand and the Creation of a New Genre of Queer Media.” South East Asia Research 27 (2): 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/0967828X.2019.1627762.

- Baudinette, T. 2020. “Creative Misreadings of Thai BL by a Filipino Fan Community: Dislocating Knowledge Production in Transnational Queer Fandoms Through Aspirational Consumption.” Mechademia 13 (1): 101–118. https://doi.org/10.5749/mech.13.1.0101

- Baudinette, T. 2023. Boys Love Media in Thailand: Celebrity, Fans, and Transnational Asian Queer Popular Culture. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Beaulieu, A. 2004. “Mediating Ethnography: Objectivity and the Making of Ethnographies of the Internet.” Social Epistemology 18 (2-3): 139–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/0269172042000249264.

- Bunyavejchewin, P. 2022. “The Queer if Limited Effects of Boys Love Manga Fandom in Thailand.” In Queer Transfigurations: Boys Love Media in Asia, edited by J. Welker, 181–193. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Chan, Y. K. 2021. “A Heteropatriarchy in Moderation: Reading Family in a Thai Boys Love Lakhon.” East Asian Journal of Popular Culture 7 (1): 81–94. https://doi.org/10.1386/eapc_00040_1.

- Chang, J., and H. Tian. 2021. “Girl Power in Boy Love: Yaoi, Online Female Counterculture, and Digital Feminism in China.” Feminist Media Studies 21 (4): 604–620. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2020.1803942.

- Chen, K. H. 2010. Asia as Method—Toward Deimperialization. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Chen, K. H. 2012. “Takeuchi Yoshimi’s 1960 ‘Asia as Method’ Lecture.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 13 (2): 317–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649373.2012.662937.

- Ching, L. T. S. レオ・チン. 2021. 反日 東アジアにおける感情の政治 [Anti-Japan: The Politics of Sentiment in Postcolonial East Asia]. Supervised translation by Kohei Kurahashi. Kyoto: 人文書院 [Jinbunshoin].

- Chua, B. H. 2004. “Conceptualizing an East Asian Popular Culture.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 5 (2): 200–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/1464937042000236711.

- Chua, B. H., and K. Iwabuchi, eds. 2008. East Asian Pop Culture: Analysing the Korean Wave. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Dym, B., and C. Fiesler. 2020. “Ethical and Privacy Considerations for Research Using Online Fandom Data.” Transformative Works and Cultures 33. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2020.1733.

- Edris, A. M. 2020. “Motivational Dimension and Social Reality in the Creation and Consumption of BL Materials.” Accessed July 11, 2023. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343150126_Motivational_Dimension_and_Social_Reality_in_the_Creation_and_Consumption_of_BL_Materials.

- Fiske, J. 2002. “The Cultural Economy of Fandom.” In The Adoring Audience, edited by L. A. Lewis, 30–49. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Fujita, Y., and F. Kitamura 藤田結子, 北村文. 2013. 現代エスノグラフィー:新しいフィールドワークの理論と実践 [Contemporary Ethnography: New Fieldwork Theories and Practices]. Tokyo: 新曜社 [Shinyosha].

- Fukui, M. 福井求. 2022. “日本で「タイBLドラマ」がこれだけ盛り上がるワケ” [Why ‘Thai BL Drama’ is So Popular in Japan]. 東洋経済ONLINE [Toyo Keizai Online], November 20. Accessed February 28, 2023. https://toyokeizai.net/articles/-/632706.

- Hall, S. 2004. “Encoding/Decoding.” In Culture, Media, Language: Fan Culture and Popular Culture, edited by S. Hall, D. Hobson, A. Lowe, and P. Willis, 117–127. London: Routledge.

- Hellekson, K. 2011. “Affect and Interpretation: Acafandom and Beyond: Week Two, Part One.” June 20. Accessed June 20, 2022. http://henryjenkins.org/blog/2011/06/acafandom_and_beyond_week_two.html.

- Hirota, F. 廣田ふみ. 2018. “実践としてのトランスナショナル” [Transnational as a Practice]. In 越境する文化・コンテンツ・想像力 [Transnational Culture, Contents, Imagination], edited by K. Kouma and K. Matsumoto 高馬京子, 松本健太郎, 203–219. Kyoto: ナカニシヤ出版 [Nakanishiya Publishing].

- Ho, M. H. S. 2022. “‘Queer’ Media in Inter-Asia: Thinking Gender and Sexuality-Transnationally.” In Media in Asia: Global, Digital, Gendered and Mobile, edited by Y. Kim, 226–238. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hori, A. 堀あきこ. 2020a. “社会問題化するBL” [BL, Becoming a Social Problem].” In BLの教科書 [Textbook of BL], edited by A. Hori and Y. Mori, 堀あきこ, 守如子, 206–220. Tokyo: 有斐閣 [Yuhikaku].

- Hori, A. 堀あきこ. 2020b. “Thai BL Drama ‘2gether’ Lands in Japan for the First Time! But Why Fans are Disappointed.” Gendai Business, August 29. Accessed March 11, 2024. https://gendai.ismedia.jp/articles/-/75122.

- Hori, A., and Y. Mori. 堀あきこ, 守如子. 2020. BLの教科書 [Textbook of BL]. Tokyo: 有斐閣[Yuhikaku].

- Iwabuchi, K. 2002. Recentering Globalization: Popular Culture and Japanese Transnationalism. London: Duke University Press.

- Iwabuchi, K. 2011. “Ekkyou Suru Koukyousei” [Publicness Crossing Borders]. In カルチュラル・スタディーズで読み解くアジア [Reading Asia Through Cultural Studies], edited by M. Iwasaki, G. Chen, and S. Yoshimi. 岩崎稔, 陳光興, 吉見俊哉, 256–270, Tokyo: せりか書房 [Serica Shobo].

- Iwabuchi, K. 岩渕功一. 2016. トランスナショナル・ジャパン ポピュラー文化がアジアをひらく[Transnational Japan: Popular Culture Opens Asia]. Tokyo: 岩波書店 [Iwanami Shoten].

- Iwabuchi, K., and S. Shimauchi. 2023. “Inter-Asian Perceptions of Studying ‘Abroad’ in Asia: Analysis of Japanese Students’ Discourse.” Globalisation, Societies and Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2023.2272739.

- Jeannotte, M. S. 2021. “When the Gigs are Gone: Valuing Arts, Culture and Media in the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Social Sciences & Humanities Open 3 (1): 100097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2020.100097

- Jenkins, H. 2011. “The Origins of ‘Acafan’.” Accessed July 20, 2022. http://henryjenkins.org/blog/2011/06/acafandom_and_beyond_week_two.html.

- Jenkins, H. ヘンリー・ジェンキンス. 2021. コンバージェンス・カルチャー ファンとメディアがつくる参加型文化 [Convergence Culture: Participatory Culture Created by Fans and Media]. Translated by 渡部宏樹, 北村紗衣, 阿部康人 K. Watabe, S. Kitamura, and Y. Abe. Tokyo: 晶文社 [Shobun-sha].

- Jirattikorn, A. 2021. “Between Ironic Pleasure and Exotic Nostalgia: Audience Reception of Thai Television Dramas among Youth in China.” Asian Journal of Communication 31 (2): 124–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2021.1892786.

- Kakizaki, I. 柿崎一郎. 2016. タイの基礎知識 [Basic Knowledge of Thailand]. Tokyo: めこん [Mekong].

- Kawamura, M. 川村湊. 1993. “大衆オリエンタリズムとアジア認識” [Mass Orientalism and Asian recognition]. In 近代日本と植民地〈7〉文化の中の植民地』 [Modern Japan and its Colony-Colony in Culture], edited by S. Oe, K. Asada, T. Mitani, K. Goto, H. Kobayashi, S. Takasaki, M. Wakabayashi and M. Kawamura 大江志乃夫, 浅田喬二, 三谷太一郎, 後藤乾一, 小林英夫, 高崎宗司, 若林正丈, 107–136. Tokyo: 岩波書店 [Iwanami Shoten].

- Keenapan, Nattha. 2001. “Japanese Boys Love’ Comics a Hit among Thais.” Kyodo News, August 31.

- Kim, Y. 2008. Media Consumption and Everyday Life in Asia. London: Routledge.

- Kim, H. 金孝眞. 2020. “BLとナショナリズム” [BL and Nationalism], In BLの教科書 [Textbook of BL], edited by A. Hori and Y. Mori 堀あきこ, 守如子, 238–254. Tokyo: 有斐閣 [Yuhikaku].

- Lee, K. 2021. “Acafan Methodologies and Giving Back to the Fan Community.” Transformative Works and Cultures 36. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2021.2025.

- McLelland, M., and J. Welker. 2015. “An Introduction to ‘Boys Love’ in Japan.” In Boys Love Manga and Beyond: History, Culture, and Community in Japan, edited by M. McLelland, K. Nagaike, K. Suganuma, and J. Welker, 3–22. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press.

- Namiki, Y. 並木頼寿. 2008. 日本人のアジア認識 [Japanese Perception of Asia]. Tokyo:山川出版社 [Yamakawa Shuppansha].

- Nihon Keizai Shimbun 日本経済新聞. 2022. “タイBLドラマ、世界に拡散 「本家」日本も逆輸入” [Thai Boys Love Drama Spreading to the World: Japan, the “Original Home,” Reimported], April 3. Accessed January 12, 2023. https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXZQOKC1466M0U2A310C2000000.

- Outani, A. 2020. “王谷晶. 推しと萌えとオタクと女” [My Bias, Moe, Otaku and Female]. In ユリイカ 9月号 [EUREKA September issue], 54–57, Tokyo: 青土社 [Seidosha].

- Perez, C. C. キャロライン・クリアド=ペレス. 2020. 存在しない女たち:男性優位の社会にひそむ見せかけのファクトを暴く [Invisible Women: Data Bias in a World Designed for Men]. Tokyo: 河出書房新社 [Kawade Shobo Shinsha].

- Prasannam, N. 2023. “Authorial Revisions of Boys Love/Y Novels: The Dialogue between Activism and the Literary Industry in Thailand.” Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific 49. https://doi.org/10.25911/PJHM-E120

- Prasannam, N., and Chan Y. K. 2023. “Thai Boys Love (BL)/Y (aoi) in Literary and Media Industries.” Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific 49. https://doi.org/10.25911/FC44-RB16

- Rath, S. P. 2004. “Post/past-’Orientalism’ Orientalism and Its Dis/Re-Orientation.” Comparative American Studies An International Journal 2 (3): 342–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477570004045596.

- Reuters. 2023. “Thailand Edges Closer to Legalising Same-Sex Marriage,” December 21. Accessed January 12, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/thailand-edges-closer-legalising-same-sex-marriage-2023-12-21/.

- Said, E. [1978] 1994. Orientalism. New York: Vintage Book Company.

- Sakaguchi, S. 坂口さゆり. 2021. “主演俳優の美しさは「歩くルーブル美術館」?タイBLドラマが人気沸騰 タイ語教室受講者も急増” [Is the Beauty of the Lead Actor a “Walking Louvre”? Thai BL Dramas Soar in Popularity and the Number of Students Taking Thai Language Classes Also Soars]. AERA dot, December 21. Accessed February 28, 2024. https://dot.asahi.com/aera/2021121700055.html?page=1.

- Sato, M., and H. Ishida. 佐藤麻衣, 石田仁. 2022. BL読者/非読者に対する調査 [Survey of BL Readers/Nonreaders Report]. Accessed February 29, 2024. https://researchmap.jp/ishidahitoshi/published_works.

- Shi, Y. 2020. “An Analysis of the Popularity of Thai Drama in China, 2014–2019.” Proceedings of the 2020 3rd International Coonference on Humanities Education and Social Sciences. Accessed March 13, 2024. https://www.atlantis-press.com/proceedings/ichess-20/125949124.

- Shimauchi, S. 2023a. “Thai Boys Love Drama Fandom as a Transnational and Trans-subcultural Contact Zone in Japan.” Continuum. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2023.2237709.

- Shimauchi, S. 嶋内佐絵. 2023b. “日本におけるタイBLドラマの受容とファンダム” [The Reception and Fandom of Thai BL in Japan]. In BLの国際的な広がりと、各国のLGBTQ [LGBTQ Issues and the Globalization of “BL”], International Symposium, Meiji University, November 26. Accessed February 29, 2024. https://www.meiji.ac.jp/nippon/info/2023/mkmht000000nkm5p.html.

- Shinsan, N. 辛酸なめ子. 2020. 辛酸なめ子の「おうちで楽しむ」イケメン2020 Vol.5「まさに沼 … !」『2gether』のタイBLイケメン」 [Nameko Shinsan’s “Fun at Home” Ikemen 2020 vol. 5 “A Veritable Swamp..!” Thai BL Handsome Men of “2gether”], August 6. CLASSY. Accessed February 29, 2024. https://classy-online.jp/lifestyle/96833/.

- Shioiri, S. 塩入すみ. 2019. ロケーションとしての留学 台湾人留学生の批判的エスノグラフィー [Studying Abroad as a Location: Critical Ethnography of Taiwanese Students]. Tokyo: 生活書院 [Seikatu Shoin].

- Takeuchi, Y. 竹内好. 1993. 日本とアジア [Japan and Asia]. Tokyo:ちくま学芸文庫 [Chikuma Gakugei Bunko].

- Takeuchi, Y. 2005. “Asia as Method.” In What is Modernity? Writings of Takeuchi Yoshimi, edited and translated by R. F. Calichman, 149–166. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Tanabe, S. 田辺俊介. 2008. “日本人の外国好感度とその構造の実証的検討” [An Empirical Investigation Into the Structure of Foreign-Favouritism Among the “Japanese”]. 社会学評論 [Japanese Sociological Review] 59 (2): 369–387.

- The BL Xpress. 2023. “The Rise in Symbolic Storytelling in the BL Industry.” The BL Express, June 18. Accessed March 13, 2024. https://theblxpress.wordpress.com/2023/06/18/the-rise-in-symbolic-storytelling-in-the-bl-industry/.

- The Japan Society of Thai Studies 日本タイ学会. 2009. タイ事典 [The Cyclopedia of Thailand]. Tokyo: めこん [Mekong].

- Thussu, D. K. 2007. Media on the Move: Global Flow and Contra-Flow. London: Routledge.

- Tidarat, R. 2002. “The Popularization of Japanese Youth Culture in the Media in Thailand.” MA diss., Chulalongkorn University.

- Tsurumi, S. 鶴見俊輔. 1999. 限界芸術論 [Theory of Marginal Art]. Tokyo:ちくま学芸文庫 [Chikuma Gakugei Bunko].

- Turner, S. 2016. “Making Friends the Japanese Way: Exploring Yaoi Manga Fans’ Online Practices.” Mutual Images Journal 1: 47–70. https://doi.org/10.32926/2016.1.TUR.makin

- Vlassis, A. 2021. “Global Online Platforms, COVID-19, and Culture: The Global Pandemic, an Accelerator Toward Which Direction?” Media, Culture & Society 43 (5): 957–969. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443721994537

- Welker, J. 2006. “Beautiful, Borrowed, and Bent: ‘Boys’ Love’ as Girls’ Love in Shôjo Manga.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 31 (3): 841–870. https://doi.org/10.1086/498987.

- Welker, J., ed. ジェームズ・ウェルカー編著. 2019. BLが開く扉 変容するアジアのセクシャリティとジェンダー [BL Opening Doors: Transfiguring Sexuality and Gender in Asia]. Tokyo:青土社 [Seidosha].

- William, K.-C. I. 2022. “The Insatiable Hunger of BL Drama KinnPorsche.” Teen VOGUE, May 16. Accessed March 11, 2024. https://www.teenvogue.com/story/kinnporsche-stars-apo-mile-interview.

- Wong, A. K. 2020. “Toward a Queer Affective Economy of Boys’ Love in Contemporary Chinese Media.” Continuum 34 (4): 500–513. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2020.1785078.

- Wood, A. 2013. “Boys’ Love Anime and Queer Desires in Convergence Culture: Transnational Fandom, Censorship and Resistance.” Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics 4 (1): 44–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/21504857.2013.784201.

- Xu, Y., and L. Yang. 2013. “Forbidden Love: Incest, Generational Conflict, and the Erotics of Power in Chinese BL Fiction.” Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics 4 (1): 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/21504857.2013.771378

- Ye, S. 2022. “Word of Honor and Brand Homonationalism with ‘Chinese Characteristics’: The Dangai Industry, Queer Masculinity and the ‘Opacity’ of the State.” Feminist Media Studies 23 (4): 1593–1609. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2022.2037007.

- Yoshimi, S. 吉見俊哉. 2007. 親米と反米 [Pro-American and Anti-American]. Tokyo: 岩波新書 [Iwanami Shinsho].

- Yoshimi, S. 吉見俊哉. 2011. “東アジアのカルチュラル・スタディーズとは何か” [What is Cultural Studies in East Asia]. In カルチュラル・スタディーズで読み解くアジア [Reading Asia Through Cultural Studies], edited by M. Iwasaki, G. Chen, and S. Yoshimi 岩崎稔, 陳光興, 吉見俊哉, 256–270. Tokyo: せりか書房 [Serica Shobo].