ABSTRACT

Entrepreneur coaches face increased well-being challenges due to their demanding roles. However, they also often report experiencing flow – an immersive, enjoyable state of intense focus that positively affects well-being. In this qualitative study of 20 self-employed career, executive, health, leadership, and life coaches, we aimed to understand entrepreneur coaches’ experience of flow and relationships with recovery at work. We found that recovery was important for entering flow and coaches actively scheduled recovery activities, such as regular breaks, to support recovery and to enter and sustain flow. These findings contribute to research on how the interplay between flow and recovery can contribute to the well-being and sustainable working lives of entrepreneur coaches.

Implications for practitioners

Our study highlights the benefits of experiencing flow at work and the role of recovery and flow in the performance and well-being of entrepreneur coaches. Coaches, supervisors, and trainers of coaches will benefit by understanding that

experiencing flow boosts performance, motivation, sense of achievement and well-being

recovery fuels flow and was found to be crucial for entering and sustaining flow

entrepreneur coaches can purposefully craft recovery strategies to increase flow at work

1. Introduction

Globally, the small business sector is estimated to provide over 70% of employment (International Labour Organization (ILO), Citation2023). In the European Union (EU) in 2022, there were 27.6 million self-employed people representing 17% of employed persons (Eurofound, Citation2024). As the rate of entrepreneurship increases, so too does the need to develop our understanding of how to balance entrepreneurs’ well-being and performance to support sustainable enterprises. Entrepreneurship plays a key role in economic development and is recognised as an important driver of economic recovery in the face of crises such as climate change, the Covid-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, the energy crisis, and economic crisis (GEM (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor), Citation2023). Entrepreneurship and well-being are recognised as part of the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals of Decent work and economic growth and Good health and well-being, strengthening the importance of research on entrepreneurship (United Nations, Citation2015). Coaches were chosen as a focus for this study as coaching represents a growing segment of entrepreneurs globally. A recent survey of 14,591 coaches from 157 countries by the International Coaching Federation (ICF) showed a 54% increase in the number of coach practitioners worldwide between 2019 and 2022 and this growth is expected to continue (ICF, Citation2023).

Entrepreneurs face increased pressures on their physiological and psychological resources due to work intensity, technostress (Michalik & Schermuly, Citation2022) and responsibility for personal and business performance which can lead to stress and feeling overwhelmed (Patzelt & Shepherd, Citation2011; Stephan, Citation2018; Stephan et al., Citation2022; Wach et al., Citation2021). In this study, we will focus on two core factors that support entrepreneurs in performing their challenging and demanding roles: recovery and flow (Williamson et al., Citation2021).

Recovery is defined as the process by which an individual’s functional systems return to pre-stressor levels after a period of stress (Meijman & Mulder, Citation1998). There is some empirical evidence that recovery can assist entrepreneur well-being (Wach et al., Citation2021; Williamson et al., Citation2019, Citation2021). Flow refers to a mental state of total cognitive immersion and intense focus in a work-related activity and may also serve as a buffer against stress (Rivkin et al., Citation2018).

Accordingly, the purpose of our study was to understand if and how entrepreneur coaches can increase their flow at work to counterbalance the stressors of entrepreneurship and improve well-being, and whether recovery may play a role in this process.

1.1. Entrepreneurs’ flow

When individuals experience intense engagement in their work, they can enter a state of flow. Flow is a term introduced by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1975) to describe people´s optimal experience: a mental state of total cognitive immersion and intense focus in an activity. During a state of flow, one loses track of time, loses a sense of self-consciousness, feels in control, and finds the experience intrinsically rewarding (Csikszentmihalyi & LeFevre, Citation1989). Paradoxically, during a flow state, one can have a sense of time standing still – or time might seem to pass quickly. During flow, one can face an extreme challenge – yet the task can feel effortless, and even though one might feel fully present – one can lose all sense of self.

Flow can be experienced alone or with others and differences have been noted in the dynamics of these experiences. While the concept of flow was initially developed in the study of solitary activities (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1975), social flow was later identified as the experience of flow with others in groups or teams (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2003; Kaye, Citation2015; Ryu & Parsons, Citation2012; Walker, Citation2010). Still, knowledge on these types of flow is limited thus far.

Flow has been linked to the building of personal resources and shown to have a positive relationship with well-being and performance in employees (Csikszentmihalyi & LeFevre, Citation1989; Demerouti, Citation2006; Ilies et al., Citation2017; Pimenta de Devotto et al., Citation2020; Rivkin et al., Citation2018; Zito et al., Citation2019) as well as in entrepreneurs (Kauanui et al., Citation2014; Sherman et al., Citation2016). However, there is little qualitative research on the phenomenology of entrepreneurial flow, and none known focusing on the flow experience of entrepreneur coaches which this study addresses. Updated research is needed to increase our knowledge of how flow is experienced among different professionals and its effect on performance and well-being.

1.2. Entrepreneurs’ recovery

Adequate physiological and psychological recovery has been shown to reduce stress and contribute to entrepreneurs’ well-being (Wach et al., Citation2021). Recovery includes the activities, experiences, and states that replenish mental and physiological resources in response to work-related stressors (Zijlstra & Sonnentag, Citation2007). The effort-recovery (E-R) model (Meijman & Mulder, Citation1998), suggests that recovery occurs when job demands are no longer present. Psychological detachment, the complete mental detachment from work that allows one to ‘switch off’ and recover from work-related stressors, has been shown to be a strong recovery mechanism (Minkkinen et al., Citation2021; Skurak et al., Citation2021; Sonnentag & Kruel, Citation2006). Earlier studies found that recovery resulting from lunchtime and other workday detachment breaks resulted in better concentration, increased work engagement, reduced fatigue, and higher well-being (Binnewies et al., Citation2009; Debus et al., Citation2014; Demerouti et al., Citation2012; Kühnel et al., Citation2017; Sianoja et al., Citation2016, Citation2018; Sonnentag et al., Citation2010; Sonnentag & Fritz, Citation2015).

The often boundaryless nature of entrepreneurs’ work and non-work life implies that it can be particularly challenging to mentally detach from the stressors of entrepreneurial activities (GEM (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor), Citation2023; Williamson et al., Citation2021). However, the flexible working patterns of entrepreneurs enable them to manage their work differently from employees who are usually required to work within defined core working hours, for a set number of hours per day and at certain locations. For instance, studies have shown that employees may have limited opportunities to engage in energy management behaviours and low levels of control over their breaks (de Bloom et al., Citation2015). In contrast, entrepreneurs usually have more freedom to craft their recovery by taking breaks when and how they want and choosing work tasks that are more energising over work that is draining. An earlier empirical study of coaches, many of whom were also self-employed, found that proactive self-regulation activities including recovery, supported coach well-being (McEwen & Rowson, Citation2022).

Together, it can be presumed that recovery and flow may act as powerful buffers against the stresses and strains of entrepreneurship. In this study, we examined the working lives of entrepreneur coaches by exploring (1) the characteristics of entrepreneur coaches’ experience of flow at work, (2) the possible impact of flow on recovery, well-being and performance and, (3) whether and how entrepreneur coaches purposefully crafted recovery experiences to enter, sustain and re-enter flow. Our study brings new insights into the vital role flow and recovery plays in entrepreneur coaches’ well-being and performance. We also provide new insights into the different types of flow experienced by entrepreneur coaches including solitary and shared flow (Liu & Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2020; Magyaródi & Oláh, Citation2015; Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2014; Walker, Citation2010, Citation2021) and the role recovery plays in shaping these flow experiences.

2. Methods

In this study, participants (N = 20) were entrepreneur coaches whose core business activities included external professional coaching in the areas of career, executive, health, leadership, and life coaching. In addition to coaching, participants also performed other activities as part of their entrepreneurial activity such as supervision, training, mentoring, writing and consulting. Some participants also produced coaching-related products like books, coaching tools, courses and other resources. Participants were recruited from various professional associations including the Association for Coaching (AC), the Career Development Institute (CDI), the European Mentoring & Coaching Council (EMCC) and the International Coaching Federation (ICF). Others responded to an open call posted in various coaching and consulting groups on LinkedIn and Facebook in February 2022. Interviews were conducted between February 2022 and June 2022.

Study participants were engaged in their business for two years or more with an average length of entrepreneurship of 8.6 years. Most of the participants (n = 18) were solopreneurs apart from two. One of which had a single business partner and the other employed three team members in their business. All participants were English-speaking, self-employed coaches in the UK (n = 13), France (n = 5), Portugal (n = 1) and Ireland (n = 1). Study participants were aged between 30 and 62 years old (average age of 45.6), 70% female (n = 14), 30% male (n = 6) and 90% held a bachelor’s degree or above (55% master’s degree, 25% bachelor’s degree, 10% PhD and 10% other, non-degree coaching qualifications).

Consent was obtained from participants who were informed that the interviews would be audio-recorded and pseudo-anonymised. Interviewees were provided with a brief description of flow including the known pre-conditions and characteristics of flow as defined by Csikszentmihalyi (Citation1997) and (Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2014).

One-hour semi-structured interviews were scheduled and conducted online via Microsoft Teams with an average length of 43:58 min. The interviews were conducted by the main researcher who is also a professional coach, consultant and entrepreneur. Participants were asked a variety of questions including reasons for entering into entrepreneurship, to describe their business activity and the daily work tasks they performed. This was followed by a series of open-ended questions about how they organised their work, their experience of flow, recovery, hindrances to flow and antecedents of flow. Finally, participants were asked about the effects of flow on their performance and well-being.

Audio interviews were transcribed and analysed in ATLAS.ti 22, a digital qualitative analysis tool. The data were analysed using Braun & Clarke’s (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) thematic analysis to identify, analyse and report the emerging themes within the data. This method was chosen as it allows for rich qualitative data to be effectively organised, analysed, and described in addition to identifying similarities and differences across data sets, generating deep insights.

Interview audio files and transcripts were pseudo-anonymised to protect the identity of interviewees. Using an inductive approach, the interviews were listened to, and the transcripts were read multiple times. Notes were taken during the interviews and during reading to record early observations and questions emerging from the data. Initial codes were generated to organise the interview data into broad categories. The codes were further developed by considering the research questions and relevant identified theories. The data were then classified using thematic codes resulting in several codes and sub-codes which were further analysed and refined to remove duplicate codes. Three main themes were subsequently formed from five code group categories which are described in the results section.

It should be noted that interviewees were likely aware that the interviewer was also an experienced, practising coach. This may have impacted what interviewees shared and did not share. For example, interviewees may have highlighted best practice and potentially, not described behaviours or practices they felt might be judged as unethical or unprofessional.

3. Results

Interview data were coded into five initial categories or code groups including characteristics of flow (with subcategories of types of flow, feelings during flow, feelings after flow), antecedents to flow, hindrances to flow, effects of flow and reasons for entrepreneurship. These code groups were expanded to include recovery, performance, well-being, absence of flow, and comprised a total of 558 codes. Further thematic analysis revealed three main themes: the role of recovery in flow, crafting recovery experiences for flow, and the effects of flow on entrepreneurial well-being and performance.

The results revealed that all 20 entrepreneur coaches interviewed stated they had experienced flow in their work. While most of the interviewees said they experienced flow daily, some experienced flow just a few times per week. Interviewees detailed specific actions they took to cultivate flow at work and described the strategies they used to manage energy levels before, during and after flow. Furthermore, they explained the numerous positive effects of flow for them, their clients and their coaching business as well as the costs of flow. In the next sections, we will describe the identified characteristics of flow, how interviewees sustained flow, their capacity for flow, and how they felt in the absence of flow. We also present findings in relation to the positive effects of flow, the costs of flow and how entrepreneur coaches crafted recovery for flow.

3.1. Characteristics of entrepreneur coaches’ flow

3.1.1. Solitary, dyadic and group flow

The first aim of the study was to understand how entrepreneur coaches experience flow at work by asking them to describe a recent flow event. When recalling their flow experiences, interviewees described three distinct forms of flow in their work namely: solitary, dyadic and group flow. Solitary flow was experienced when working alone either in isolation or in a public setting such as a co-working space or café for example. Dyadic flow, was typically reported between a coach and coachee but could also occur with co-workers, project collaborators and others. Group flow, was flow experienced in a group setting while interacting with more than one other person. For the participants in this study, these were typically group coaching or supervision sessions, presentations, teaching, or facilitating workshops.

Solitary flow was most frequently experienced by interviewees and was typically a longer-lasting experience than other types of flow. Aligning with the definition of flow (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1975), coaches greatly enjoyed the experience of flow, lost track of time and felt they had performed at their best.

‘I feel energized, and I'm kind of excited, but I can also sometimes, wish I wasn't having to come out of it. I can have this resistance to leaving it. Whereas I don't generally get that with the people stuff. But I do with the individual stuff. Sometimes I'm like: Oh, I've got to now stop this, and go here and do this, or be involved in that. So sometimes there can be a resistance to leave that flow.’ [Interviewee 20]

‘When I was doing a lot of content writing for my website, I might have flowed for six hours. So, if I'm kind of sat down, and I get an idea for something to write about, or a blog post then I'd sit down and I'd write for six hours.’ [Interviewee 9]

‘I've hesitated from using the word spirituality because it's not just that oneness when things come together, a connectedness. I think that it’s a particularly heightened experience, it's profound, something meaningful, it's very distinct from the normal mundane experience. And there's a oneness, there is something spiritual, but it's not related to a God or something like that. It’s a oneness, a connectedness of being completely in that moment.’ [Interviewee 12]

‘I feel I'm doing a good job. I'm making a difference. You know, I'm working hard. I'm using my skills, my knowledge and expertise and I'm putting all of that to good use. It might be hard work and it might be challenging but in a good way. I produce something that is good and that makes a difference to other people. And that makes me feel good, I may have worked hard and that made the difference to somebody else that makes me feel good about myself.’ [Interviewee 9]

‘I became quite energized, whereas usually, if you were getting extra work, it would be like oh that's more work. But I was actually very energized. Technically it was meant to be an hour, but it turned out I was with her for two hours and ten minutes and I didn't notice that. At first, I didn't notice the first half an hour, and then I didn't notice the rest of the time pass.’ [Interviewee 20]

‘I mostly access flow every time I present or train for a day, usually I get into a flow. And in any group work that I do. So that's like, four to six hours, twice a week, once or twice a week. And then there's the individual clients and I don't access flow every time I'm with a client. But it does happen a couple of times a day.’ [Interviewee 20]

3.2. Sustaining flow

Interviewees were found to embed feedback mechanisms into their work which helped them enter and sustain flow. Monitoring performance and seeking feedback from coaches during a coaching session for example or checking in with participants in the case of group work. Sometimes this was verbal, other times it was an observation of the level of engagement of others in the case of dyadic and group flow for instance. This allowed them to gauge and adjust their performance during the flow experience to keep the flow going.

‘ … going into that flow event, I had all the bits and pieces that I needed to ensure that it was going to be successful, I was prepared and organized. I think as a result of that, during the flow event, I could see that being reciprocated by the client as well. And I could see that they were in the moment and in the zone with it. So, there was that kind of connection I think that we had. And after it, this always happens – after that type of thing I get an enormous amount of adrenaline whenever that works. And I feel like my energy's very high. It's very positive.’ [Interviewee 18]

‘I'll probably prep, so like so right now I have two drinks in front of me, I'd have two or three drinks, so that they're in front of me. So that's the other thing I can stay in flow if the stuff I need is in front of me. And if I know that tomorrow I had a load of writing to do, or a load of client work, I would put snacks out and about so that I wouldn't have to think of them, they'd just be there.’ [Interviewee 20]

3.3. Capacity for flow

Some interviewees recognised that they only have so much capacity for flow and managed their work in such a way as to maintain a high level of job performance and avoid burnout.

‘Whilst flow, especially the positive flow, is really engaging and I feel great afterwards, I generally find that there's only so much flow I can achieve in a day because my brain gets tired. It's a bit like running a marathon, or, you know, you put all your energy into that activity, that there's a bit less of it for other activities.’ [Interviewee 2]

‘I think it (flow) makes me incredibly productive. So obviously, the more I experience it, the more I want it, and the more I seek it. And it's, you know, and I think that's when I generate the most ideas. And as I said, it does lead to feeling productive. So I will actually be very speedy at designing things and producing things and get a lot done. So the speed level, you know, it's, I can, when I'm in that state, I can do a lot and achieve a lot. And I can look back at the end of the day and think oh gosh that's an incredibly productive day.’ [Interviewee 12]

3.4. Absence of flow

The absence of flow left some entrepreneurs feeling dissatisfied. They expressed feeling that their work had less meaning and impact. This led to questioning what they could do differently in the future to increase the likelihood of achieving flow.

‘If I didn't access flow in my week, a couple of times, I would feel like the week wasn't very successful.’ [Interviewee 20]

3.5. Positive effects of flow

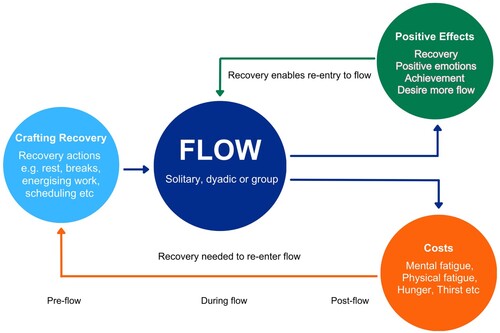

It was observed that different types of flow (dyadic, solitary and group) could result in varied recovery effects (see ). This differed between interviewees and appeared to be related to personality traits, psychological and physiological states, and external situational factors such as task demands and environment. Some flow events were energy-giving leading to a virtuous cycle (Foulk et al., Citation2019) of peak experience and recovery, while other flow events could be energy-depleting. The cyclic process is depicted in the figure.

Numerous interviewees described feeling their energy levels were boosted by flow (particularly dyadic flow) and reported feeling energised, excited, and rejuvenated.

‘I can get energy; I feel energized from it [flow] rather than drained.’ [Interviewee 12]

‘I would say energized. Yeah, they [flow events] leave me feeling very energized.’ [Interviewee 13]

‘I don't feel drained. I feel fulfilled, I feel satisfied that I've helped somebody. I've done a good job. You know, that's important to me. I've done it to the best of my ability. I've done it excellently, that's important to me. I don’t like to do things sloppy and whatever. So when all those things come together, I recognize yeah – there's been flow so it’s been a good day today.’ [Interviewee 10]

‘I also feel like the days I find flow, it's easier to disconnect from work at the end of the day. Because I know I've been productive, and I've been successful.’ [Interviewee 7]

‘I think it [flow] makes me incredibly productive. So obviously, the more I experience it, the more I want it, and the more I seek it. And it's, you know, and I think that's when I generate the most ideas. And as I said, it does lead to feeling productive. So, I will actually be very speedy at designing things and producing things and get a lot done. So the speed level, you know, it's, I can, when I'm in that state, I can do a lot and achieve a lot. And I can look back at the end of the day and think oh gosh that's an incredibly productive day.’ [Interviewee 12]

3.6. Costs of flow

While flow was described as a positive experience by interviewees, the costs of flow were also recognised. After some flow experiences, interviewees expressed feeling physically tired, mentally drained and even exhausted, in the case of intense and long-lasting flow for instance. Hunger, thirst, and the need to tend to pain or other physical needs were also described as after-effects of flow events. Shorter flow episodes were reported to be less physiologically and psychologically draining than longer ones.

‘Whilst flow, especially the positive flow, is really engaging and I feel great afterwards, I generally find that there's only so much flow I can achieve in a day because my brain gets tired. It's a bit like running a marathon, or, you know, you put all your energy into that activity, that there's a bit less of it for other activities.’ [Interviewee 2]

‘How do I feel after flow? Satisfied but tired. I think when you’re in that groove, there is a big sense of satisfaction. And there are times when it is, it's almost when you step back and think about it, just by thinking about what you've achieved, can be quite mentally draining. So, it's almost as if your body's on catch-up. I kind of liken it to, if you're in a, I don't know, like in a fight or flight situation or stressful situation that you can get through it and then once the incident has finished, your body plays a little bit of catch-up, and then you feel quite exhausted.’ [Interview 11]

‘When I'm doing the coaching. I feel really energetic, a mild euphoria. And afterwards, I feel quite drained. But the thing is, I have something that kicks in, like I said, where it's just you and the task at hand. And I can do that for really quite an extensive time. And actually, I'm not sure that I feel tired. I might feel wired afterwards, maybe. And it might take a little bit of time to kind of wind down.’ [Interviewee 4]

‘I think it's interesting because you become so focused, and my guess is there is that the neuro chemistry is such that your adrenaline is flowing to a degree. So, when you stop, the adrenaline drain happens, and you go: ‘Oh, I'm quite tired, actually’, or ‘I'm quite hungry’, or, you know, I just need to stop being ‘on’.’ [Interviewee 14]

3.7. Crafting for recovery

Adequate recovery and effective energy management were found to be vital to entrepreneur coaches experiencing flow. Interviewees described how in the lead-up to a flow event, they took steps to be as recovered as possible. Getting a good night’s sleep, eating well, exercising (e.g., yoga, stretching and walking) and mindfulness were common recovery activities.

‘If I've had a couple of weeks with not enough sleep, or if I have quite big worries, it might be harder to access flow in general.’ [Interviewee 20]

‘If I'm writing, doing business stuff or website work, it's interspersing that with exercise. Because I will consciously take time out, I mean, I've got two dogs anyway, so they want to go out for a run or for a walk or whatever. So, you know, they're a good barometer, that means I can't just sit there for 10 h writing because you know, the dogs would be most unhappy with that. So, the dogs insist that I take some time out and go, but actually going out, whether that's for a walk, or for a run, or whether I go to the gym, or whatever, that kind of breaks that up a little bit but that also then helps me enter and stay in flow.’ [Interview 9]

‘I need a break, I can’t maintain a constant state of flow. Because I think it could be quite exhausting. So, I take a break from flow, just you know, do something else, step away, clear my head, do something that just doesn't require it. It can be a really boring dull exercise that I really don't want to do. But actually, it's probably beneficial for me mentally to do it so that my flow is focused on the right aspects of my business.’ [Interviewee 2]

‘The kind of obvious is leaving space in between meetings or sessions. I do that in my diary. As the coach, or the facilitator, I think you have to be okay. My way of looking after my mental health is by going for a walk every day. Sometimes I can only fit in 20 min, or the maximum would be an hour that I do every day. And I'll do a mindful walk or just get out and see some green space. I kind of try to look after my mental health, I try to practice mindfulness and meditation, I think that helps me.’ [Interviewee 1]

‘Regular pauses. And so, it's not only you know the hour where I go for a walk, but it's also making sure that during the day I pause, so it's listening to my body and knowing when it's time to actually have a short break and leave my office so not staying in my office. I will go to another room; I will prepare a cup of tea. I will spend five minutes in the garden. I will watch a short video, but whatever I do is leaving physically, my office going to another room to actually give my brain a break. And that I would say I do it at least five or six times a day.’ [Interviewee 8]

4. Discussion

This study represents the first qualitative examination of the phenomenology of flow and recovery in entrepreneur coaches. While a few previous studies explored coaches’ flow experiences in coaching (McBride, Citation2013; Wesson, Citation2010), they did not examine non-coaching flow, nor did they focus on entrepreneur coaches whose flow experiences may be different to those of employed coaches. Equally, there has been very little research into the flow experiences of entrepreneurs (Ruiz-Martínez et al., Citation2021; Sherman et al., Citation2016). Our investigation encompassed a range of flow experiences, including solitary, dyadic and group flow, across the various activities of entrepreneur coaches. While previous research has explored different types of flow, there has been little research investigating the experiences of entrepreneurs or coaches. Additionally, we shed light on the proactive self-regulation strategies employed by entrepreneur coaches to achieve recovery, enter and sustain flow, and the impact on well-being and performance. This study also adds to the recognised need for research into entrepreneurs’ well-being and recovery (Wach et al., Citation2021).

Table 1. Workday recovery breaks.

4.1. Flow’s impact on performance and well-being

Our study saw a strong relationship between flow, intrinsic motivation and performance which had a positive impact on entrepreneurs’ well-being aligning with earlier findings (Kauanui et al., Citation2014; Sherman et al., Citation2016). Aside from the numerous positive emotions resulting from flow, interviewees linked flow to increased productivity and performance leading to a sense of achievement. As has been observed in employees (Salanova et al., Citation2006), a relationship between resources and flow was observed in this study suggesting an upward spiral. The broaden-and build-theory of positive emotions (Fredrickson, Citation1998) posits that positive emotions can build an individual’s physical, intellectual, and social resources. This upward spiral not only increases performance and well-being (Fredrickson, Citation2001; Laguna et al., Citation2017) but may also play an important role in entrepreneurial sustainability due to increased engagement, enjoyment and success (Laguna & Razmus, Citation2019; Tang, Citation2020). Participants’ descriptions of post-flow feelings of positive emotions (such as joy, pride and satisfaction), optimal performance and achievement, and how these feelings made them desire more flow, points to an upward spiral. Feeling a sense of pride for instance, is thought to boost self-esteem, optimism and motivation (see Fredrickson, Citation2000). Considering the increased demands on entrepreneurs, broaden-and build-theory shows how positive emotions can act as a buffer for negative emotions through the development of psychological capital (Garland et al., Citation2010).

4.2. Recovery and flow

Recovery played a threefold role with respect to flow. First, our study demonstrated that recovery was crucial to experiencing flow per se. Second, entrepreneur coaches were also found to take proactive self-regulatory actions to craft recovery to access and sustain flow, and finally, flow also represented recovery. Participants reported that if they were not well-rested or recovered, they struggled to achieve flow. This supports previous findings that the reduction of feelings of exhaustion was needed to increase the likelihood of experiencing flow at work (Mäkikangas et al., Citation2010). An earlier qualitative study of coaches also found that flow was more likely to be experienced when coaches were well-rested and had sufficient energy (Wesson, Citation2010). Given the established link between recovery and the ability to achieve flow, it is understandable that entrepreneur coaches in our study made concerted efforts to devise and implement a range of recovery strategies. Participants in our study reported both positive effects and costs of flow which they explained as being related to the type of flow experienced (solitary, dyadic or group), the tasks, the amount of flow (frequency and duration) and their level of recovery. One explanation might be that entrepreneurs find some activities (an impactful coaching session for instance) to be more intrinsically rewarding and meaningful than for example, invoicing. Our study also found that experiencing flow could result in feelings of recovery for many interviewees. This aligns with earlier research into flow in employees that found that experiencing flow at work can increase vigour and decrease exhaustion (Demerouti et al., Citation2012).

The most important finding from the study was the extent to which entrepreneurs purposefully crafted recovery actions to directly support their well-being and performance and to increase their chances of (re-) entering flow. Being recovered at the start of the workday was bolstered by further recovery actions purposefully scheduled during the workday. Taking regular breaks, both scheduled and as needed, was a common recovery strategy for entrepreneurs that increased the likelihood of entering flow. While participants in our study employed a variety of recovery strategies, psychological detachment was found to be a highly effective and well-used recovery strategy. Psychological detachment is known to be a powerful recovery strategy during and outside of the workday (Bennett et al., Citation2018; Bosch et al., Citation2018; Sianoja et al., Citation2018; Sonnentag & Fritz, Citation2015; Zijlstra & Sonnentag, Citation2007). Another interesting observation was that some interviewees mentioned that when they had experienced flow at work, they were better able to psychologically detach from work at the end of the day. This is consistent with earlier research that found that those who experience flow at work are more likely to experience improved psychological detachment from work during non-work hours (Demerouti et al., Citation2012).

5. Limitations and future research

As this study was conducted through single, semi-structured interviews, it would be beneficial to conduct a longitudinal study that follows entrepreneurs’ flow and recovery across an extended period. This would allow for even richer insight into the experience of flow and the impact recovery has on flow experiences, well-being and performance. Participants in this study were located in Europe and were predominately solo entrepreneur coaches working alone and performing coaching, consulting and related activities. As such, they managed their entrepreneurial activity alongside their main work as coaches. It would be interesting to see if the findings of this study could be replicated in other types of entrepreneurs. For instance, employer coaches may be subject to different types of tasks, pressures, and responsibilities and have access to different resources that support the engagement of flow and recovery. Our study thus highlights the need for further research into the dispositional, situational and contextual factors that can impact the experience of flow, recovery, performance and well-being. Overall, it is clear that more research, particularly experimental or quasi experimental research establishing causal relationships, is needed to better understand the relationship between entrepreneurs’ flow, recovery, well-being and performance and sustainable work.

6. Conclusions

This qualitative study aimed to understand entrepreneur coaches’ experience of flow at work as well as its relationship to recovery and well-being. Results showed how entrepreneur coaches purposefully crafted recovery experiences to enter, sustain and re-enter flow to achieve high levels of performance and well-being. The study also revealed that being well-rested, focused and in a positive mental state were benefits of recovery that aided the flow experience. While recovery was found to be a strong antecedent to entrepreneur coaches’ ability to enter and sustain flow, we also found that flow itself may contribute to recovery. The study showed that regular recovery breaks and experiencing flow are a powerful combination for coaches’ performance and well-being. These findings provide a basis for further empirical research to support entrepreneur coaches’ well-being, performance, and entrepreneurial sustainability.

Informed consent

Permission to conduct the interviews for the purposes of this research was obtained by all respondents, who were fully informed about the purposes of this research and how their responses would be used and stored.

Ethics statement

This study has been conducted in accordance with the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity TENK guidelines 2019 and is exempt from ethical approval.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [LL], upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lisa LaRue

Lisa LaRue is an EMCC-accredited Master Practitioner Coach and Career Coach working in private practice. She holds a master’s degree in career development from Edith Cowan University and a degree in social science from Southern Cross University. Her doctoral research at the Faculty of Social Sciences (Psychology) at Tampere University focuses on the impact of flow on workplace well-being and performance.

Anne Mäkikangas

Anne Mäkikangas, PhD in psychology, is a Director of the Work Research Centre and Professor of Work Research at Tampere University. She has substantive expertise in the research of work stress and well-being at work from various perspectives including flow and recovery. She has published over 130 scientific publications on these topics.

Jessica de Bloom

Dr. Jessica de Bloom is a Work and Organizational Psychologist at the University of Groningen (Netherlands). As a full professor in Human Resource Management, Occupational Health and Wellbeing, her area of expertise concerns the interface between work and non-work, job stress, recovery, e-mental health and occupational interventions to improve well-being at work. In her research, she aims to integrate perspectives from several academic disciplines such as psychology, leisure sciences and human resource management.

References

- Bennett, A. A., Bakker, A. B., & Field, J. G. (2018). Recovery from work-related effort: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(3), 262–275. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2217

- Binnewies, C., Sonnentag, S., & Mojza, E. J. (2009). Daily performance at work: Feeling recovered in the morning as a predictor of day-level job performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(1), 67–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.541

- Bosch, C., Sonnentag, S., & Pinck, A. S. (2018). What makes for a good break? A diary study on recovery experiences during lunch break. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 91(1), 134–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12195

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1975). Beyond boredom and anxiety. Jossey-Bass.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Finding flow: The psychology of engagement with everyday life. Basic Books.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2003). Good business: Leadership, flow and the making of meaning. Penguin Books.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., & LeFevre, J. (1989). Optimal experience in work and leisure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(5), 815–822. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.5.815

- de Bloom, J., Kinnunen, U., & Korpela, K. (2015). Recovery processes during and after work: Associations with health, work engagement, and job performance. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 57(7), 732–742. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000000475

- Debus, M. E., Sonnentag, S., Deutsch, W., & Nussbeck, F. W. (2014). Making flow happen: The effects of being recovered on work-related flow between and within days. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(4), 713–722. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035881

- Demerouti, E. (2006). Job characteristics, flow, and performance: The moderating role of conscientiousness. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 11(3), 266–280. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.11.3.266

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Sonnentag, S., & Fullagar, C. J. (2012). Work-related flow and energy at work and at home: A study on the role of daily recovery. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(2), 276–295. https://doi.org/10.1002/JOB.760

- Eurofound. (2024). Self-employment in the EU: Job quality and developments in social protection. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Foulk, T. A., Lanaj, K., & Krishnan, S. (2019). The virtuous cycle of daily motivation: Effects of daily strivings on work behaviors, need satisfaction, and next-day strivings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 104(6), 755–775. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000385

- Fredrickson, B. (1998). What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 300–319. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.300

- Fredrickson, B. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2000). Why positive emotions matter in organizations: Lessons from the broaden-and-build model. The Psychologist-Manager Journal, 4(2), 131–142.

- Garland, E. L., Fredrickson, B., Kring, A. M., Johnson, D. P., Meyer, P. S., & Penn, D. L. (2010). Upward spirals of positive emotions counter downward spirals of negativity: Insights from the broaden-and-build theory and affective neuroscience on the treatment of emotion dysfunctions and deficits in psychopathology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.002

- GEM (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor). (2023). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2022/2023 Global Report Adapting to a ‘New Normal’. https://gemconsortium.org/report/20222023-global-entrepreneurship-monitor-global-report-adapting-to-a-new-normal-2

- Ilies, R., Wagner, D., Wilson, K., Ceja, L., Johnson, M., DeRue, S., & Ilgen, D. (2017). Flow at work and basic psychological needs: Effects on well-being. Applied Psychology, 66(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12075

- International Coaching Federation (ICF). (2023). ICF Global Coaching Study 2023 Executive Summary. https://coachingfederation.org/app/uploads/2023/04/2023ICFGlobalCoachingStudy_ExecutiveSummary.pdf

- International Labour Organization (ILO). (2023). World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2023. https://doi.org/10.54394/SNCP1637

- Kauanui, S. K., Gulf, F., Sherman, C. L., & Randall, C. (2014). Entrepreneurs’ subjective well-being: Examining flow, self-rated success, and productivity. International Council for Small Business (ICSB). https://scholarscommons.fgcu.edu/esploro/outputs/99383895135006570

- Kaye, L. K. (2015). Exploring flow experiences in cooperative digital gaming contexts. Computers in Human Behavior, 55(Part A), 286–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.023

- Kühnel, J., Zacher, H., de Bloom, J., & Bledow, R. (2017). Take a break! Benefits of sleep and short breaks for daily work engagement. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 26(4), 481–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2016.1269750

- Laguna, M., & Razmus, W. (2019). When I feel my business succeeds, I flourish: Reciprocal relationships between positive orientation, work engagement, and entrepreneurial success. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(8), 2711–2731. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-0065-1

- Laguna, M., Razmus, W., & Żaliński, A. (2017). Dynamic relationships between personal resources and work engagement in entrepreneurs. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 90(2), 248–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/JOOP.12170

- Liu, T., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2020). Flow among introverts and extraverts in solitary and social activities. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110197

- Magyaródi, T., & Oláh, A. (2015). A cross-sectional survey study about the most common solitary and social flow activities to extend the concept of optimal experience. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 11(4), 632–650. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v11i4.866

- Mäkikangas, A., Bakker, A. B., Aunola, K., & Demerouti, E. (2010). Job resources and flow at work: Modelling the relationship via latent growth curve and mixture model methodology. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(3), 795–814. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317909X476333

- McBride, B. (2013). Coaching, clients, and competencies: How coaches experience the flow state [Doctoral dissertation, Fielding Graduate University]. https://researchportal.coachingfederation.org/Document/Pdf/abstract_3153

- McEwen, D., & Rowson, T. (2022). Saying yes when you need to and no when you need to’ an interpretative phenomenological analysis on coaches’ well-being. Coaching. https://doi.org/10.1080/17521882.2022.2030380

- Meijman, T., & Mulder, G. (1998). Psychological aspects of workload. In P. J. D. Drenth, H. Thierry, & C. J. de Wolff (Eds.), A handbook of work and organizational psychology (pp. 5–33). Psychology Press/Erlbaum (UK) Taylor & Francis.

- Michalik, N. M., & Schermuly, C. C. (2022). Is technostress stressing coaches out? The relevance of technostress to coaches’ emotional exhaustion and coaches’ perception of coaching success. Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice, 16(2), 155–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/17521882.2022.2128386

- Minkkinen, J., Kinnunen, U., & Mauno, S. (2021). Does psychological detachment from work protect employees under high intensified job demands? Scandinavian Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 6(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.16993/sjwop.97

- Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). The concept of flow. In: Flow and the foundations of positive psychology. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9088-8_16

- Patzelt, H., & Shepherd, D. A. (2011). Negative emotions of an entrepreneurial career: Self-employment and regulatory coping behaviors. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(2), 226–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.08.002

- Pimenta de Devotto, R., Freitas, C. P. P., & Wechsler, S. M. (2020). The role of job crafting on the promotion of flow and wellbeing. Revista de Administração Mackenzie, 21(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-6971/eRAMD200113

- Rivkin, W., Diestel, S., & Schmidt, K. H. (2018). Which daily experiences can foster well-being at work? A diary study on the interplay between flow experiences, affective commitment, and self-control demands. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(1), 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1037/OCP0000039

- Ruiz-Martínez, R., Kuschel, K., & Pastor, I. (2021). Craftswomen entrepreneurs in flow: No boundaries between business and leisure. Community, Work & Family, 38(5), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2021.1873106

- Ryu, H., & Parsons, D. (2012). Risky business or sharing the load? Social flow in collaborative mobile learning. Computers & Education, 58(2), 707–720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.09.019

- Salanova, M., Bakker, A. B., & Llorens, S. (2006). Flow at work: Evidence for an upward spiral of personal and organizational resources. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-005-8854-8

- Sherman, C. L., Randall, C., & Kauanui, S. K. (2016). Are you happy yet? Entrepreneurs’ subjective well-being. Journal of Management, Spirituality and Religion, 13(1), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2015.1043575

- Sianoja, M., Kinnunen, U., de Bloom, J., Korpela, K., & Geurts, S. (2016). Recovery during lunch breaks: Testing long-term relations with energy levels at work. Scandinavian Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 1(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.16993/sjwop.13

- Sianoja, M., Syrek, C. J., de Bloom, J., Korpela, K., & Kinnunen, U. (2018). Enhancing daily well-being at work through lunchtime park walks and relaxation exercises: Recovery experiences as mediators. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(3), 428–442. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000083

- Skurak, H. H., Malinen, S., Näswall, K., & Kuntz, J. C. (2021). Employee wellbeing: The role of psychological detachment on the relationship between engagement and work-life conflict. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 42(1), 116–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X17750473

- Sonnentag, S., Binnewies, C., & Mojza, E. J. (2010). Staying well and engaged when demands are high: The role of psychological detachment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 965–976. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020032

- Sonnentag, S., & Fritz, C. (2015). Recovery from job stress: The stressor-detachment model as an integrative framework. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(S1), S72–S103. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1924

- Sonnentag, S., & Kruel, U. (2006). Psychological detachment from work during off-job time: The role of job stressors, job involvement, and recovery-related self-efficacy. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 15(2), 197–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320500513939

- Stephan, U. (2018). Entrepreneurs’ mental health and well-being: A review and research agenda. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 17(3), 290–322. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2017.0001

- Stephan, U., Rauch, A., & Hatak, I. (2022). Happy entrepreneurs? Everywhere? A meta-analysis of entrepreneurship and wellbeing. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 47(2), 553–593. https://doi.org/10.1177/10422587211072799

- Tang, J.-J. (2020). Psychological capital and entrepreneurship sustainability. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(866). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00866

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. UN Publishing. https://sdgs.un.org/publications/transforming-our-world-2030-agenda-sustainable-development-17981

- Wach, D., Stephan, U., Weinberger, E., & Wegge, J. (2021). Entrepreneurs’ stressors and well-being: A recovery perspective and diary study. Journal of Business Venturing, 36(5), 106016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2020.106016

- Walker, C. J. (2010). Experiencing flow: Is doing it together better than doing it alone? The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760903271116

- Walker, C. J. (2021). Social flow. In C. Peifer & S. Engeser (Eds.), Advances in flow research (pp. 263–286). Springer International Publishing.

- Wesson, K. J. (2010). Flow in coaching conversation. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring Special Issue, 4. http://www.business.brookes.ac.uk/research/areas/coaching&mentoring/

- Williamson, A. J., Battisti, M., Leatherbee, M., & Gish, J. J. (2019). Rest, zest, and my innovative best: Sleep and mood as drivers of entrepreneurs’ innovative behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 43(3), 582–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258718798630

- Williamson, A. J., Gish, J. J., & Stephan, U. (2021). Let’s focus on solutions to entrepreneurial ill-being: Recovery interventions to enhance entrepreneurial well-being. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 45(6), 1307–1338. https://doi.org/10.1177/10422587211006431

- Zijlstra, F. R. H., & Sonnentag, S. (2007). After work is done: Psychological perspectives on recovery from work. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 15(2), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320500513855

- Zito, M., Cortese, C., & Colombo, L. (2019). The role of resources and flow at work in well-being. SAGE Open, 9(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019849732