ABSTRACT

Three decades after the argumentative turn in policy analysis and planning, interpretive approaches have become part of mainstream policy analysis. Increasingly, researchers work within these traditions. Researchers new to these approaches might struggle to make conceptual and methodological choices. We therefore compare three prominent interpretive approaches: discourse analysis, framing analysis and narrative analysis. Discourse analysis is the study of hegemonic, dominant and recessive discursive structures. It explores how power is embedded in language and (re)produces dominant social structures. Framing analysis involves studying processes of meaning construction. It explores what elements of reality are strategically or tacitly foregrounded or backgrounded in conversations and text, and how this includes and excludes voices, ideas and interests in policy and decision-making. Narrative analysis investigates the work of storytelling. It explores how people make sense of events through the selection and connection of story elements: events, settings and characters. These approaches share ontological and epistemological starting points, but offer different results. In this paper, we show what they each contribute to critical policy analysis and develop a heuristic for selecting or combining approaches. We give a renewed entry point for interpretive work and contribute to dialogs on commonalities and differences between approaches.

Introduction

Three decades after the argumentative turn in policy analysis and planning (Fischer and Forester Citation1993; Yanow Citation1993), interpretive approaches have become part of mainstream policy analysis. Standing groups have been established at international conferences, and there is a large body of well-cited publications (see for instance: Bevir and Rhodes Citation2006; Fischer Citation2003; Fischer and Gottweis Citation2012; Hajer and Wagenaar Citation2003; Stone Citation1997; Van Hulst and Yanow Citation2016; Wagenaar Citation2011; Yanow Citation2000). When we look at studies of policy across the social sciences, a broader pattern of critical interpretive research becomes visible. Over time, an increasing number of researchers in policy studies, planning and related disciplines such as political science and public administration, environmental studies, conflict studies and science and technology studies have sought to understand and explain patterns of social construction, the role of discursive power and the dynamics of in- and exclusion in policymaking and policy implementation through concepts such as discourse, framing, narrative, practice and metaphor. They have done so for several reasons (Fischer and Forester Citation1993; Wagenaar Citation2011; Yanow Citation2000).

A first reason is to gain attention for the influential role of language in understanding and making decisions about policy and the broad variety of ways in which groups of people understand these issues. Rather than the organizational structures, actors and institutions, scholars point out that language is very influential and its role should be better understood and studied in the policy sciences. A second reason to turn to interpretive approaches has been to be able to deconstruct power relations in society beyond understanding them as mere struggles of interests. The less visible expression of power through language is at the core of the interpretive approaches in critical policy studies. Many scholars also work with critical theories, including those coming from gender studies, post colonialism and theories on justice, and some engage in critical investigations of dominant neo-liberal discourses. A third reason is to better acknowledge the social and political construction of researchers’ own knowledge production. All knowledge on policy issues is mediated by language and interpretation. Therefore, objective and universal knowledge claims cannot be made. By appreciating the role of interpretation in all sorts of knowledge production – interpretivists also aim to critically investigate the power of science and scientific knowledge production.

Interpretive approaches in critical policy studies, as we see it, provide theories, concepts and methods to critically investigate current policymaking processes and policy outcomes. They also share ontological assumptions about the nature of the world and of human beings; epistemological assumptions about how we are able to know what we know and how we develop knowledge; and methodological assumptions on how we best ‘capture’ the object of research. Researchers working in an interpretive paradigm are, in particular, interested in perspectives on the socio-political world we live in (Yanow Citation2000). These perspectives are filled with meaning and are ‘shaped, incrementally and painfully, in the struggle of everyday people with concrete, ambiguous, tenacious, practical problems and questions’ (Hajer, and Wagenaar Citation2003, 14). Moreover, epistemologically, in the interpretive tradition, the socio-political world is considered not to have ‘brute’ facts whose meaning is universal and beyond dispute. All knowledge claims are constructed and influence the world under investigation (Hajer, and Wagenaar Citation2003). And finally, interpretive approaches always look for the perspective of their ‘research subjects’, whether citizens, professionals or others whose lives and work are part of our investigations. Interpretivists often aim to create hermeneutic circles and engage with practice and practitioners not only as something or someone to be observed but to co-generate knowledge.

Interpretivism in policy analysis encompasses a range of approaches with a family resemblance. There are many introductions and overviews of critical, interpretive research in the policy sciences (e.g. Fischer Citation2003; Wagenaar Citation2011; Yanow Citation2000). There are many more texts that introduce or apply one of the familiar concepts and a specific approach linked to it (e.g. contributions to Fischer and Forester Citation1993; Fischer and Gottweis Citation2012, Van den Brink and Metze Citation2006; Fischer et al. Citation2015; Hajer and Wagenaar Citation2003; Schön and Rein Citation1994; Yanow Citation1995). In Critical Policy Studies, various approaches have been used and discussed from the very first issue onwards (e.g. Fairclough Citation2013; Howarth Citation2010; Yanow Citation2007). However, the approaches are typically discussed side by side. Yanow (Citation2000), for example, discusses metaphor, category and narrative analysis. Wagenaar (Citation2011) discusses varieties of interpretation in policy analysis and gives a practical guide toward strategies for research for what he calls ‘a Policy Analysis of Democracy’. Individual articles use a particular (versions of an) approach to a certain case. Even though some scholars endeavored to generate a coherent overall interpretive approach (Bevir and Rhodes Citation2006; Yanow Citation2000). Hence, only a few researchers in policy analysis and related fields have tried to compare across approaches, concepts and analyses in order to understand how these relate to each other (Glynos and Howarth Citation2007; Wagenaar Citation2011).

The editors of Critical Policy Studies (de Freitas Boullosa, Paul, and Smith-Carrier Citation2023, 2) recently called for ‘cross-fertilization between the critical examination of the – often colonial – genealogy and politics of key concepts in policy studies – including policy, development, state, governance, and evidence – and the development of more inclusive practices of doing research “on the ground”’. What we offer in this paper supports this endeavor. We provide a comprised way of understanding three prominent interpretive approaches in policy studies: discourse, framing and narrative analysis, to seek cross-fertilization within the interpretive, critical policy-analytical ‘toolbox’.Footnote1 We chose these three as they are well-known concepts with connected approaches in policy studies, public administration and planning, without assuming comprehensiveness. We are very well aware that other categorizations could have been made. As a team of authors, we do not give preference to one approach. Individually, we are specialized in one or two of them. We present only one of these several ‘sub’-approaches – our take on discourse, framing and narrative – in order to contrast at the level of approaches. And we leave other approaches, such as those that start from concepts like ‘category’ or ‘metaphor’ out (Yanow Citation2000). We thus do not provide a comprehensive overview of interpretive approaches, but we develop a heuristic that differentiates and demonstrates complementarity of the three much-used approaches.Footnote2 Inevitably, with our endeavor we lose nuances. Working toward a heuristic always involves ignoring many alternatives, details and finesses in the approaches. Our analytical efforts are not meant to settle debates but to offer a renewed entry point that enables researchers to explore possibilities for their own critical work. We expect researchers new to these approaches to benefit most from seeing them side-by-side. In particular, seeing more actor and more structure-focused analyses can help better understand how in the realities we study each is vital to the other. As each approach has developed over the last 30 years, more specializations and sub-approaches within them have been developed. It is therefore tempting to stick with the approach one first became acquainted with, as there is a large library on it. As a consequence, researchers might miss out on a lot of richness, both conceptually and empirically.

In what follows, we will first present the three approaches by sketching their background, describing the concepts and work they do when we apply them. We will draw on ideas within but certainly also beyond the policy analysis literature. Second, we will apply the three approaches to an empirical case, a short fragment from the Iraq Inquiry. Third, we describe the (dis)similarities between these different approaches as we use them and, last but not least, we will provide a way to combine or appreciate the different lenses to understand and analyze phenomena in policy and planning.

Three interpretive approaches: discourse, framing, narrative

Discourse

Background

Discourse analysis has roots in theory and analysis of ideologies and power, the sociology of science and the philosophy of language. Discourse theory assumes that ‘the relationships between human beings and the world are mediated by means of collectively created symbolic meaning systems or orders of knowledge’ (Keller Citation2012, 2). There are several studies providing an overview of discourse theory (Griggs and Howarth Citation2013). Discourse theorists have different philosophical roots: many are building on post-structuralism and normative – deliberative theories. Those who lean most on post-structuralism are inspired by Foucault, Pêcheux and also Derrida, Lacan and Wittgenstein. These discourse theorists study the emergence of hegemonic discourses through time and their power to discipline individuals vis-a-vis (governmental) institutions. Next to this, the work of Jürgen Habermas has been highly influential for normative – deliberative theories while other strands of discourse theory have more affinity with sociological theories of social and cultural inequality, for example Marxist critique of ideology and Bourdieu’s work on symbolic domination. Other well-known examples are Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) (Fairclough Citation1992, Citation2013) and Laclau and Mouffe’s Discourse Theory and its further development (Griggs and Howarth Citation2013; Laclau and Mouffe Citation1985). In policy analysis, Hajer’s (Citation1995) is probably the best known contribution.

Concept: what it is

Despite all the variance, a commonality in discourse theory is that discourse – language in use – is assumed not only to describe but also to constitute socio-political realities. Therefore, discourse analysis aims to understand power, dominance and resistance by studying language not as a neutral means but as a problematized medium through which actors not just describe but actively create the world (Wagenaar Citation2011). Discourse theory and analysis consider language as constitutive of power and dominance, and as intertwined with practice (Van den Brink and Metze Citation2006). There are many different definitions of discourse, but for reasons of clarity, we will define discourse as ‘an ensemble of ideas, concepts, and categories through which meaning is given to social and physical phenomena, and which is produced and reproduced through and identifiable set of practices’ (Hajer Citation1995, 44).

Work: what it does

Discursive scholars consider discourse as a social practice, in other words, it is through structures in our language that taboos are created, biases are mobilized and dominant ideas get institutionalized (Hajer Citation1995). Discourses are the expressions of power, ideology, dominance and resistance in policy, politics and society and at the same time discourses constitute social realities. Discourse analysts aim to understand the work discourses do. Language does not simply ‘float’ in society, but it is intertwined with particular practices in which it is employed (Fischer and Forester Citation1993). Discourse theory and analysis have shown how discursive practices, techniques or mechanisms are produced and reproduced in institutional systems. As such, discourse as a linguistic structure disciplines common-sense norms, which is especially relevant in politics and policymaking, such as punishment, health care, sexuality (in Foucault’s work), environment (Hajer Citation1995), energy controversies (Metze and Dodge Citation2016) and migration (van Ostaijen Citation2016, Citation2020).

Discourse theory and analysis also study how power of hegemonic discourses is contested by countervailing discourses. Discourse analysis aims not only to show how discourses become and remain dominant over time but also how alternative discourses contest dominations and open up new ways of understanding phenomena (Laclau and Mouffe Citation1985). Text – in a general sense – figures as a site of struggle in which voices contest and struggle for dominance (Fairclough Citation1992). Scholars in discourse theory focus on language as a structure much more than on the agency of actors or organizations in the production and reproduction of language. In that focus, there is some agency in the formation of discursive networks of actors, around floating or empty signifiers (Laclau and Mouffe Citation1985), around storylines (Hajer Citation1995) or boundary objects (Metze and Dodge Citation2016). These ‘nexus’ enable the study of competing linguistic structures that are tied together by these storylines, boundary objects, empty or floating signifiers (Griggs and Howarth Citation2013).

Without stepping into structuralism versus poststructuralism or early versus old Foucauldian disputes (Wagenaar Citation2011), generally, a discourse analytical approach provides tools to understand and analyze how certain relations of ‘truth’, power and dominance are structured and reproduced by ‘truth claims’, not only discursively but also in practices. From a discursive perspective, discourses as disciplinary structures are everywhere, but there is always the possibility of resistance. Therefore, the potential of empirical sources of investigation is numerous. But for some guidance in how to determine what an ‘ensemble of concepts, ideas and categories’ are, discourse analysis can be conducted on three levels: textual, contextual and sociological (Jorge Citation2009). At the textual level, a corpus or text itself can be studied: the words, the structure and semiotics. At the contextual level, it is language-in-use that is studied such as the conversational or intertextual analysis in order to understand the meaning of words. At the sociological level, the language uttered is considered a social product. It can be approached as a (dominant) system which can be analyzed as institutionalized, or marginalized, neglected even silenced with practical consequences in society (Smith Ochoa Citation2020). Therefore, a discursive analysis can be enabled but is not limited to textual sources, for example policy documents, newspaper articles, interviews, transcripts of meetings and so on. A combination of textual, contextual and sociological elements can, for example, be seen in the analysis of discourse coalitions which relates texts, context and institutionalization of practices since a discourse coalition is ‘... the ensemble of a set of story lines, the actors who utter these story lines, and the practices in which this discursive activity is based’ (Hajer Citation1995, 65).

Framing

Background

Framing gained traction as a concept in a diversity of disciplinary fields, including decision-making (Tversky and Kahneman Citation1986), communication and media studies (Entman Citation1993), social movement studies (Benford and Snow Citation2000), political science (Chong and Druckman Citation2007), conflict and negotiation studies (Dewulf et al. Citation2009), and public administration and policy studies (Schön and Rein Citation1994; Van Hulst and Yanow Citation2016). This has led to a variety of conceptualizations of what frames are and what framing entails and a variety of methods to study framing. Experimental studies generally try to establish evidence for or against framing effects, such as studies that aim to find the different effects of gain and loss frames on decision preferences (Tversky and Kahneman Citation1986). Interpretive studies, among others, use framing as a conceptual and methodological tool to understand and analyze processes of meaning-making and to capture differences between actors in how they construct meaning of and in policy processes or to understand how frames emerge, evolve or become dominant (Dewulf and Bouwen Citation2012). While another string of literature deals with the (un)intended use of framing and its power effects (Van Lieshout et al. Citation2017). Probably the best known frame analysis in policy studies is Schön and Rein’s (Citation1994) but is somewhat outdated (Van Hulst and Yanow Citation2016).

Concept: what it is

A common denominator in the diverse usage of frames seems to be that something, like a notion of a problem or solution, can be understood in different ways, according to different frames, highlighting specific aspects and leaving out others. In this sense, frames are never neutral and can be powerful, they can influence public opinion and policymaking – and sort reality effects (Entman Citation1993). Or, dominant discourses make some frames resonate better and more powerful. In communication studies, Entman (Citation1993) has proposed the following often-cited definition of framing: ‘To frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described’ (p. 52). A frame, as it is used most often, is a definition of an issue or a situation.

Framing relies on establishing a relation between a cue and a frame, in which a cue is a piece of information, notion or event that is framed in a certain way. For example, news about increased oil drilling in the Arctic Sea, which can be framed as environmental problem, economic opportunity for the region or the answer to global energy demands. According to Weick (Citation1995, 110), ‘a cue in a frame is what makes sense, not the cue alone or the frame alone’. Ambiguity or the phenomenon that multiple possible frames can be connected to a cue, and multiple possible cues can be connected to a frame, is at the core of framing (Stone Citation1997). Selecting and arranging issue elements into cues and frames does not happen in an abstract universe but at the level of discourse or language-in-use, in the way issue frames are forged out of language and the way issue elements are linguistically formulated. In that sense, framing is a much more fundamental process than spinning, because language-based frames constitute socio-political realities, through which entitlements of powerful elites and precarity of vulnerable social groups can be repeatedly normalized as ‘the way things are’ (Dewulf et al. Citation2019).

Interactional approaches to framing focus on how the meaning of issues, identities and processes are framed in interaction between people (Dewulf et al. Citation2009). In this approach, framing is defined as the interactive construction of issues, identities and processes, and frames are defined as transient communication structures, to be understood within the relevant interactional context. Power is enacted in the relationships between these interacting agents, through the ways they make, e.g. their resource entitlements, hierarchical positions, discursive legitimacy or reframing of what the issue is about, relevant to the issue and interaction at hand.

Work: what it does

In framing, specific cues are embedded in a specific frame. In this way framing accomplishes a number of things, creating particular understandings and ruling out others (Dewulf et al. Citation2011): First, by selecting both cues and frames, it includes and it excludes certain aspects or meanings, and thus establishes boundaries. Second, within the selected cues, some get the focus of attention and become foreground, while others are relegated to the periphery and become background. Third, by the process of embedding, some aspects become part and others become whole. By highlighting certain aspects of the situation at the expense of others, by drawing different boundaries around the issue and by putting different elements at the core of the issue, people from different backgrounds construct frames about the situation in a specific frame context, that may differ considerably from how others frame the issues, or how the issue would be framed in different contexts (Dewulf et al. Citation2013; Van Hulst and Yanow Citation2016). From an interactional framing perspective, framing is a form of action in a specific interactional context, for example, in a multilateral negotiation, in a discussion on Twitter, in a court plea or in a hallway conversation between a civil servant and the minister. These frame interactions may take the form of constructing shared ways of framing the situation; proceed in conflictive ways ending up in a process of frame polarization (Dewulf and Bouwen Citation2012) or situations in which certain frames become suppressed or dominant over others (Dewulf et al. Citation2019). Interactional framing analysis pays particular attention to how frame differences are being constructed and addressed by participants, through analyzing how they use language to forge, connect or undermine framings in spoken or written interaction.

Framing allows people to make a graceful normative leap from is to ought (Schön and Rein Citation1994), because different frames point toward different responses or action strategies. Framing, therefore, is an action influencing consequent interactions and actions (e.g. decisions, policies). Whoever is able to set the terms of the debate steers the debate in a certain direction. This susceptibility of people, including policymakers, experts and citizens, to the way issues are framed creates the possibility for strategic framing. Through highlighting positive versus negative aspects of the situation, through setting reference points or through including and excluding particular aspects or people in a communicative act, one can try to influence frames that others will rely on for taking decisions. While most framing happens subconsciously, framing can thus be used as a strategy to reach communicational, commercial or political goals (Benford and Snow Citation2000). When more actors are trying to influence a policy debate through framing, frame contests may be the result, in which frames and counter-frames are constructed, promoted or undermined. Through framing, implicitly or explicitly, and intentionally or unintentionally, particular interests are advocated or undermined, power positions are maintained or challenged, and particular actors are included or excluded from policy debates.

Narrative

Background

Research on story and narrative (which we treat as synonyms here, Riessman Citation2008) has its roots in social studies of language (e.g. Labov Citation1972). An interest in studying stories has slowly but steadily becomes more popular across the social sciences (Riessman Citation2008). Narrative analysis has developed especially strong in the field of organizational studies (Boje Citation1991). Basic assumptions underlying most studies are that the human being is a story-telling animal, that narrative is important in making sense of experience (Boje Citation1991). We can distinguish different approaches in narrative research. Relevant to policy analysis are those that focus on how language can be used to shape people’s action, also attributing agency to narratives (Miller Citation2020; Roe Citation1994) and investigating human intentions (Ospina and Dodge Citation2005). We think, to do this properly, one has to look at the elements of stories as they are told (Labov Citation1972). Other approaches have focused more on the way stories are told in interaction, how they result from interaction between storytellers and audiences (Boje Citation1991). In policy analysis, the work of Stone (Citation1988; 1997) is probably the best known contribution in policy analysis.

Concepts: what it is

Here, we define a story as a description of events involving characters (human and non-human) who are placed in a temporal and spatial setting (Van Hulst Citation2012). Storytelling is about someone telling someone else that something happened (Smith Citation1980). Most of the people we know would be able to recognize a story when they would hear one and also to be able to tell a story if asked for – on the spot. In fact, most of us tell at least a handful and perhaps many stories on a daily basis. In everyday life, storytelling manifests itself most often as ‘an exchange between two or more persons during which a past or anticipated experience [is] referenced, recounted, interpreted, or challenged’ (Boje Citation1991, 111). Everyday questions like, ‘How was your weekend?’ or ‘What happened yesterday at that the meeting?’ typically lead to storytelling. In organizations, and in other social contexts, actors often tell each other stories. News reports, policy documents and political speeches are other examples of story-rich materials. Also in the context of research, in interviews, when offered the opportunity, interviewees often tell stories (Mishler Citation1986). And even academic articles can be conceived of as stories (van Bommel et al. Citation2013). As such, storytelling is everywhere, although not everything is a story (Roe Citation1994).

Work: what it does

Stories do not just entertain but they do all sorts of work (Forester Citation1993; Riessman Citation2008). Telling stories is not just listing events. Through the specific way in which stories represent what has happened, they ‘emplot’ the past (Czarniawska 2004). The work of Stone (Citation1997) shows, for example, that some policy problems can be seen as stories of decline with the following plot: ‘In the beginning, things were pretty good. But they got worse. In fact, right now, they are intolerable. Something has to be done’ (Stone Citation1997, 139). Such plots, with their recognizable structure, have cultural resonance. Van Hulst (Citation2012) describes a case in which an alderman tells the story of a heartless town in need of a new town center. His talks about the long process leading up to the telling as one of slow decline, legitimizing a renewed planning process to save the town. The story obscures the idea that residents might have lost their interest a new town center. The alderman was a powerful teller who does not just describe reality but also models it to fit his plans (Van Hulst Citation2012). Stories thus can help us to understand the world and to act upon it through policy. Narrative analysis, then, might ‘help researchers parse through the swampland of entangled politics that often characterizes public policy discourse through all its stages and evolving dynamics’ (Miller and Lofaro Citation2023, 46).

The effect of a story depends, in big part, on its performance, how it is brought to life, its interpretation and its fit with other discursive structures (de Vries et al. Citation2014). Tierney et al. (Citation2006) shows how following Hurricane Katrina, the media reports initially told a story of ‘civil unrest’ which included disaster victims ‘looting’ shops. The New York Times reported that ‘Chaos gripped New Orleans on Wednesday as looters ran wild […] looters brazenly ripped open gates and ransacked stores for food, clothing, television sets, computers, jewellery, and guns’ (Tierney et al. Citation2006 66). This story quickly evolved into a story of urban warfare when the government decided to send in armed forces to restore order. A New York Times story shows the military intervention of the US government: ‘Partly because of the shortage of troops, violence raged inside the New Orleans convention center, which interviews show was even worse than previously described. Police SWAT team members found themselves plunging into the darkness, guided by the muzzle flashes of thugs’ handguns’ (Tierney et al., Citation2006, 71). This shows that storytelling is not only about knowing and describing certain realities but it is also about creating these realities by describing them.

Of course, the elements of stories help to do this work. Story elements help attribute blame, victimhood, and other things to the characters who play a role in them, just as they select and highlight some events and acts as relevant to the plot, while others are not mentioned. Stories are key elements of social organization. In their creation, stories order and re-order the wider societal context. Importantly, if we say that stories do work, we mean to say that storytellers, through the use of story elements, suggest a certain way to make sense of events and in that way can get things done. Narrative researchers, therefore, should critically look at who has the power to tell stories and be heard, how their stories might relate to their position, interests, values and which stories remain untold and which storytellers are silenced. We do not all have (equal) access to the stage to speak. Some narrative researchers actively intervene in the situation by asking questions that elicit silenced stories or proposing narrative shifts, thereby empowering participants and voicing new stories to emerge through contestation and negotiation (Acosta et al. Citation2020).

summarizes the three interpretive approaches and provides some exemplary studies that can serve as a starting point to develop theoretical, analytical and methodological thinking.

Table 1. Three approaches.

Applying the approaches: the Iraq hearings

In this section, we illustrate and apply the three approaches through the analysis of a short text fragment (see Iraq Inquiry, Friday, 29 January 2010 2010-01-29-transcript-blair-s1.pdf (nationalarchives.gov.uk) pages 5–8). This fragment we chose because it is a publicly available interaction on policymaking. The fragment comes from the Chilcot Inquiry on the (second) Iraq War, with its hearings taking place in the period 2009–2011. It is a transcript of a small part of the hearings, one in which former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair visits the commission to share his experiences about the policy processes that led to the invasion of Iraq. In the fragment, commission member Sir Roderic Lyne speaks with Tony Blair.

Inquiry fragment Iraq Inquiry fragment: a discourse analysis

One could start a discourse analysis on the Iraq Inquiry that was instigated to investigate to what extent the participation of the United Kingdom (UK) in the Iraq war was legitimate, by creating a helicopter view based on all policy documents, newspapers and news footage. A timeline with the most important moments, critical moments, important actors and shifts in understanding the policy issue will help create this overview. For further analysis from a sociological perspective, one could, for example, zoom in on important moments in the decision-making process of going to war, focussing whom constructed ‘evidence’ for Iraq possessing ‘weapons of mass destruction’, but also when and why there were protests against the war. One could also position the hearing in the whole process and ask: what was the reason for having these hearings, and what were political and legal consequences of the words being used and the argumentation explicated?

An interesting angle from a contextual perspective could be to question the formal authority of Roderick Lyne to speak, and what intersectional personal characteristics does he bring that legitimate him to speak and substantiate his part of the conversation? In what kind of setting did this conversation take place and with what kind of (public) audience? What kind of discursive function does this conversation address and which kind of power is questioned here? On the textual level, one could search for similar words used in the sources and aim to interpret what message they convey. One could find answers to contextual and sociological questions formulated in the previous steps. For example, one could deconstruct how former UK prime minister Tony Blair legitimizes the concept of a ‘strategy of problematisation’. He reflects and memorizes that ‘Saddam was still a problem, a major problem’. Tony Blair defines former Iraq president Saddam Hussein as a problem, what the problem is about and why it needed interventions. In the excerpt, other words stand out: Tony Blair reflects on the decision-making process and connects the words: ‘risk calculus’ and ‘trying to contain the risk’ to ‘containment strategies’ and a ‘smart sanctions framework’ that was put in place. He argues that after the critical moment 9/11 this general ‘risk’ calculus changed – and therefore, the strategy had to change.

The process of problematization, included in this small excerpt of the Iraq hearings, already shows the stages of defining the problem (Saddam), claiming what the problem is about (‘risk’ or ‘missile development’), legitimizing the problem (‘change in risk calculus’) and suggestions about rational interventions (‘smart sanctions resolution’). This has been legitimized by authorization (‘previous witnesses’, ‘under your leadership’ and ‘President Clinton’), rationalization (‘risk calculus’) and by – what is called ‘mythopoesis’, which are references to the past (‘very long history’) and disciplining time before and after 9/11, supported by a novel concept such as the ‘calculus of risk’. A discursive analysis could question the legitimacy of discursive structures such as containment, prevention and threat which are anything but neutral to think about the legitimacy of policy interventions. In such a study of policy discourse, one could investigate if others in other documents would make similar or dissimilar ‘truth claims’. Hence, deconstructing leads to questions such as: what is the problem represented to be, what is seen as the problem and who or what is seen as the cause (Bacchi Citation2009)? Such an approach enables to investigate the legitimacy of this particular discursive ordering.

Finally, one could investigate which discursive structures are most prominent in the texts – and what other discursive structures are marginalized or silenced. For example, analysis of other policy documents may reveal that the United States’ Bush administration used similar wordings as Tony Blair did in this hearing and talked about ‘containment’. But protesters argued, for example, that the USA had provided Iraq with ‘weapons of mass destruction’ and made a different problematization, since the war was not about Saddam Hussein being a risk – but about oil (‘no blood for oil’). Within a discursive analysis one could identify a network of meaning to understand better to what extent words and arguments are related and in what ways. By problematizing such a network of meaning makes it possible to defamiliarize the legitimacy of certain events in structured and effective ways.

Iraq Inquiry fragment: a framing analysis

A framing analysis would first try to establish what is the issue, or what is it that is being framed. On page 2 of this text, the chair frames the purpose of the Iraq inquiry as ‘to establish a reliable account of the UK’s involvement in Iraq between 2001 and 2009 and to identify lessons for future governments facing similar circumstances’ (lines 16–19); in addition, the focus of the initial questions for this hearing is framed as ‘the evolution of the strategy towards Iraq up to 2002’ (p.3, line 16). Through the questions of Roderic Lyne and the answers of Tony Blair, the UK policy strategy on Iraq is being framed in particular ways. A more elaborate framing analysis, aiming to surface the variety of frames on this topic, would not stick to this text alone. Interesting comparisons could be made with how the issues were framed in the UK or international press, by different actors and how this has influenced international politics around postwar Iraq.

The language register used to talk about the issue of the ‘UK strategy on Iraq’ is policy language about the ‘strategy’ of ‘sanctions’ for the ‘containment’ of ‘Saddam’. The combination of the phrases ‘contain/containment’ (p.5, line 9, p.6 lines 3, 10 and 12, p.7, lines 9 and 13) and ‘breaking out’ (p.5, line 17 and frequently in the remainder of the hearing) reveal a powerful metaphor through which the issue is framed – invoking images of keeping a dangerous creature (‘Saddam’) in a confined physical space through deterrence (‘sanctions’). In this way, not only issues are framed but also the identities of, and the relationships between the key actors like Tony Blair (in terms of his responsibility to ‘contain’) and Saddam Hussein (as a ‘problem’ and ‘threat’). The process of interaction itself is also framed, e.g. by Roderick Lyne as ‘summarizing the situation’ (p.5, lines 7–8) and giving a ‘fair summary’ (p.7, line 22), framing the hearing as a search for an objective and fair representation of the situation at the time.

The elaborate opening question formulated by Roderick Lyne (p.6–7) does important framing work by highlighting Tony Blair’s responsibility by referring to ‘the government, under your leadership’ (p.5, line 5), and ‘summarizing the situation since 1991’. He does this in three steps: 1) in terms of a ‘strategy of containment’ (p5., line 9) that had ‘prevented Saddam Hussain from threatening his neighbors or from developing nuclear weapons’ (p.5, lines 12–14), thereby framing the strategy as effective; (2) in terms of concerns about ‘his efforts to break out’ (p.5, line 17); and (3) in terms of the resulting policy to reinforce the containment strategy through ‘smart sanctions’ (p.6., lines 4–5) that were eventually adopted in 2002. This selection of issue elements is framed as a story of sanctions, concerns and better sanctions, developing over time between 1991 and 2002. At the end of his speaking turn, Roderic Lyne invites Tony Blair to share his view on the strategy of containment, starting with the period ‘before 9/11’ (p.6, lines 9–12).

In a question-answer setting like an interview or this hearing, questioners get the first chance to frame the issues, but respondents have the option to either go along with the framing implied by the question or to challenge it explicitly or implicitly. In his response, Tony Blair picks up on the event of 9/11 and turns it into a central point of his argument, while Roderic Lyne has not even mentioned 9/11 in his story about sanctions between 1991 and 2002 and proposed the date merely as a device to structure the discussion, namely to start with discussing the period before 9/11. In his response, Tony Blair reframes the issue in an implicit way, by ostensibly agreeing with the questioner (‘it is absolutely right to divide our policies …’, p.6, lines 13–14), but creating a different and very prominent reference point for the respondent’s story. In his discussion of the sanctions, the framing changes as well: compare, for example, concerns about ‘the enforcement of the No Fly Zone’ (Lyne on p.5, line 22,) to ‘continual breaches of the No Fly zone’ (Blair on p.6, line 18). The strategy in place, and therefore the background sketched for 9/11 and its aftermath, is thus framed differently by Roderick Lyne (as largely effective) and Tony Blair (as largely ineffective).

Tony Blair goes on to refer to ‘the attempt to put in place … smart sanctions’ (p6., lines 21–22) and to earlier ‘military action’ (p6., line 25) – this could be interpreted as a relevant precedent for the later military action – but Roderick Lyne disconnects this point from the current conversation by stating ‘We will come back to that later’ (p.7, line 2). Tony Blair responds by again emphasizing the importance of this earlier military action and continues to frame 9/11 as causing a turning point in what he terms ‘the calculus of risk’, using words from the register of rationality. Although we don’t have the contrasting frames in other arenas at hand here, it is interesting to consider what others might frame as having changed after 9/11 in the UK’s strategy, such as ‘the availability of an excuse to invade Iraq’, ‘the need for a scapegoat’ or ‘generalized suspicion against Muslim countries’. Roderick Lyne takes the discussion back to the effectiveness of the sanctions, ‘had been effective, was still sustainable, needed reinforcing, was expensive and difficult’ (p.7, lines 14–15) as a ‘fair summary’ (line 22) to Tony Blair, who ever so gently disagrees: ‘the way I would put this is this: that the sanctions were obviously eroding’ (p.7, lines 23–24). In this way, the frame difference regarding the sanctions is interactionally continued here. A more elaborate interactional framing analysis would search for patterns in how questioner and questioned deal with each other’s framings in this kind of hearings and related power relations and identify the discursive devices that are deployed to achieve this (Dewulf and Bouwen Citation2012).

Iraq Inquiry fragment: a narrative analysis

A narrative analysis starts with observing that the storytellers in this fragment construct various narratives. Roderick Lyne introduces a couple of events, actions, characters and he indicates the contours of the setting. He starts with the acts that together form a strategy: […] since 1991, a strategy of containment had prevented Saddam Hussein from threatening his neighbors or from developing nuclear weapons. However, as Roderick Lyne indicates, there had also been a development, a slow change of setting, resulting in a problem that had to be dealt with: ‘there were concerns by 2001, as there had been all along in many ways.’ He then identifies new acts that, in reaction to the problem that had developed, were meant to strengthen the general line of action (‘the containment strategy’). Blair continues the story Lyne started to tell. He starts from the suggestion Lyne ends with, that there is a difference between before and after September 11. He typifies the strategy before September 11 as ‘doing our best, hoping for the best’ and also points out that they had taken military action. Roderick Lyne, in his turn, goes back to the events leading up to September 11. He wants Tony Blair to support the part of the story he has developed, i.e. that the strategy had been working, but wasn’t sustainable. In the last bit, Tony Blair admits that they were in a difficult spot, while also taking the opportunity to repeat that they had taken military action and stress that dealings with Saddam Hussein had a long history.

Narratives in politics and policymaking often have a basic plot structure with certain moves, as Stone (Citation1997) showed. These are powerful in that they are culturally shared ways of understanding. There seem to be two main moves in Roderick Lyne’s narrative: making clear that actions had not been successful enough and making clear Tony Blair is responsible. Roderick Lyne says, first, that what had happened had been more or less successful, ’but at the same time’ a set of concerns had developed that needed attending. The problem-solving effort, that Tony Blair had been engaged in, included getting support (from the United Nations) and they failed to do so (before September 11). The second move concerns the blame for events that had taken place. Roderick Lyne puts forward Tony Blair as a main character, stressing that what British government had done, was done ‘under your leadership’. If someone is to blame for failure of policy, it is Tony Blair. To support his narrative, Roderick Lyne also brings in another storyteller: John Sawers. Lyne suggests that he should know what he is talking about, as he was working for Blair at the time. Working for Blair (not just for the British government) also indicates that he felt directly under Tony Blair’s responsibility.

Therefore, first, he points out that he was not acting on his own. Talking about ‘we’ mostly defuses the blame. Furthermore, he claims that they were ‘doing their best, hoping for the best’. In other words, we did what we could do (do not blame us for not trying), but we were not in control. As important is that Tony Blair points at a particular set of events, ‘September 11’, to have made an important change. In somewhat technical language, Tony Blair says that their ‘calculus of risk’ changed. In narrative terms, Tony Blair claims that the setting in which action was to take place changed dramatically, which forced them to act differently. The change of setting, thus, gives the characters valid reasons to act differently, which is something else then, for instance, seeing ‘September 11’ as a good excuse to do what you were planning all along but did not find good enough reasons for. Interesting, finally, is the way Saddam Hussein is made a character in both narratives. There is no distinction made between the Iraq government or Iraq as a country and Saddam Hussein. It is all Saddam Hussein (Lyne: his missile development programme, intelligence about his CW, his chemical weapons and biological weapons capabilities; Tony Blair: Saddam was still a problem, he was a risk).

In the end, for a narrative analysis, it is not enough to merely present different ways of narrating events side-by-side. Because telling a narrative in policy contexts is a public and political act, it works to, for instance, assign blame and often has consequences for the way stories will be continued beyond the telling, ‘in real life’. A hearing is a moment that those who are heard get the chance to select and connect events, characters and setting. It is also a moment that an active audience can critically question the moves made, the plots used and more. We see, in the telling, the struggle over meaning. Where do storytellers start their story, what events do they make central, who is made what kind of character? Those who elicit a story in the hearing, in a quite straightforward manner, help to tell it. We, as researchers, also help others to tell stories, (re)tell stories and should offer an understanding of the way storytellers and their audiences struggle over (narrative) truth and how this struggle works out for the different actors involved. This would also mean establishing which stories and storytellers might have been left out or silenced in the process.

Discussion and conclusion: a heuristic with entry points

Since the argumentative turn in policy analysis and planning, many publications have appeared that have used and extended approaches like the ones we have highlighted here. What unites those working in its tradition is that they encourage the development of critique of policy and with that the support of a more democratic, just and sustainable world (de Freitas Boullosa, Paul, and Smith-Carrier Citation2023). Researchers, since the turn, have broadened interest to include themes and concepts such as emotion, practice(s), justice, conflict, protest, equality and deliberation (Durose and Lowndes Citation2023; Fischer and Gottweis Citation2012; Fischer et al. Citation2015; Hajer and Wagenaar Citation2003; Wolf and Van Dooren Citation2017; Li and Wagenaar Citation2019). They have become all the more sensitive to power dynamics and the question who and, to include Latourian thinking, what gets re-presented. Although their critical potential is clear, we think it is important that researchers new to policy analysis see that and how they offer vital insights into policy issues, on their own and in combination.

To those who have come across approaches presented separately, however, interpretive approaches in critical policy studies might seem to have lived parallel lives in our discipline and wonder about fertilization across them. There has always been, however, a dialogue between researchers working with different approaches. Even though we have not investigated it, our own experience tells us that at least those who have used a certain approach in critical policy studies for some years have been in contact and often have considered using alternatives. Seeing more actor and more structure-focused analyses side-by-side can help better understand how in the realities we study one is vital to the other. It suggests that those who have studied multiple approaches have taken lessons and thinking on board in the use of their particular approach. Indeed, we can see in some work the use of multiple approaches, where researchers use a particular approach in a way that clearly signals the knowledge and use of another approach. Miller’s work (Miller Citation2020; Miller and Lofaro Citation2023) is a good example of a narrative approach that is clearly informed by a discursive one. And finally, some have used various approaches throughout their career (e.g. Metze Citation2018; Metze and Dodge Citation2016; Van Hulst Citation2012; Van Hulst and Yanow Citation2016; Yanow Citation2000). Even though the concepts and approaches we discussed here have historical roots and connotations that afford certain uses and make others less apt, there clearly are ways to blend, borrow and bricolage. Still, to a large extent, researchers using a particular approach have not shown how it relates to other approaches and we therefore believed it to be useful bringing approaches together in this article.

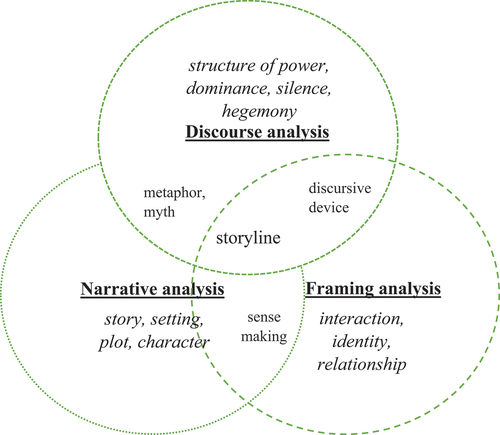

We offered an analysis of a short piece of text in this article. The text is over a decade old and refers to events taking place over two decades ago – some just after the argumentative turn in policymaking and planning. It is, however, relevant to readers of this journal, as it is an exemplary example of a highly contentious policy issue, with devastative consequences for citizens and governments across the globe, but resonates with current interpretive struggles around climate change, the pandemic and recent wars. Our three approaches are helpful in understanding how such issues are interpreted. From different angels, they help to understand what and who is highlighted and hidden. They help to show how this is done and with what results. In the heuristic in , the differences and overlap between the approaches are deliberately imagined as Venn diagrams. Although the differences are broadly sketched and we lose nuance in the overview, the figure shows how the three approaches have clear conceptual points of divergence and convergence.

They show overlap in terms of studying interpretation and meaning in action, and understanding language as action-in-use by different methods and concepts. The three approaches all include a critical stance toward the performativity of power in language-in-use. In discourse analysis, the concept of power is central and (discursive) structures are expected to discipline agents. Discourse analysts aim to unveil these disciplinary linguistic structures, rather than examining the role of participants in a conversation that sustain these power dynamics. Some scholars also recognize that discourses need to be uttered, and elements need to be ‘articulated’ in spoken and written text, in order for discursive structures to be produced and reproduced (e.g. Griggs and Howarth Citation2019; Metze and Dodge Citation2016). What stands out most in our analysis of the Iraq case is the network the discursive analysis wants to trace to other texts. Framing analysis, as we use it here, takes issues, relationship and the interaction process as anchor points. By contrast to a discursive analysis, from a framing approach, ‘power’ is located in the talk-in-action. Individuals define language and society and it is in the everyday interactions that issues such as gender or expertise are performed. In interaction, individuals create a certain social order, and by that also power relations between individuals and groups. In narrative analysis, the storyteller is granted (narrative) power or agency. In telling a story, different story elements can be selected (Van Hulst Citation2012). Actors, events and setting are the anchor points here. In the Iraq case, more than anything, the acting character became the focus of this struggle. In this way, we saw both Lyne and Blair as storytellers, bringing their particular perspectives (Ospina and Dodge Citation2005). We should, however, not underestimate the potential power of audiences, who can bring their own experiences and interpretations to a narrative, who might become co-tellers or tell counter-narratives. In the hearings, we saw not only distinct narratives but also a struggle over meaning. When zooming out, a narrative analysis might focus on the manner in which stories evolve and how they co-evolve traveling through narrative landscapes, being told, retold and edited.

There is a link between discourse analyses and narrative analyses at the textual level, having an eye for the usage of metaphors, myths, tropes and legitimation strategies. Both put the question on the table of the agency of language. Stories or storylines, for instance, can be seen as having powers apart from or over human agents who tell them. We might see them as evolving, adapting and competing for dominance (Miller Citation2020, 498). In both narrative and framing analysis, the analysis of storylines is often mentioned as a way to be able to construct the narrative or frame. Similarly, in one vein of discourse analysis, most notably the formation of discourse coalitions, storylines also play a prominent role and have the ability to act as a kind of ‘discursive cement’ (Hajer Citation1997, 63). Framing and discursive approaches share an interactional focus on discursive devices. The three approaches have different accents in their analysis – but most prominent differences are that narrative analysis does take the selected and connected elements of stories narrated by persons as the core subject of study; framing analysis is much more interested in the framings and reframings that happens in relation between actors uttered in their conversations, speeches, media outlets and so on. In discourse analysis, the discursive networks around truth claims are the main focus – and how competing discourses struggle over dominance and create political meaning (Smith Ochoa Citation2020). We also see that narrative analysis and framing analysis – more than discourse analysis – are focused on how storytellers try and make sense of policy and political issues.

Taken together, our analysis demonstrates what more analysists can see if they use multiple analyses side-by-side. It might be tempting to want to integrate approaches into a coherent critical-interpretive approach. Bevir and Rhodes (Citation2006), for instance, starting a decade after the argumentative turn, have offered a strong integrative interpretive approach using a set of concepts different from the ones used here. The benefit of is the possibility to come to a coherent theoretical framework that brings balances out various requirements (e.g. attention for both structure and agency). The risk of such endeavors would be a slow loss of connection with dialogs that feed separate approaches and increasing rigidity needed to preserve the coherence attained. Our diagram may be a useful heuristic to start asking questions and decide about what type of interpretive analysis fits best with researchers’ (a) empirical puzzle (b) research aims and results (c) ways of data collection (d) conceptual and theoretical fascinations. First, the empirical puzzle and surprise for critical scholars in policy analysis: as a researcher we often start with unsolved puzzles or surprising phenomena. This leads us to problematize empirical phenomena: how come that climate change policy takes so long? How did policy agents make sense of Covid-19? How do they interpret new acts of violence across the globe? These empirical puzzle guides one in a direction for a particular interpretive approach and the particular approach also shapes what is puzzling. As we can see in the example, a discourse analysist might be more interested in the broader social processes surrounding the Iraq war and how this is connected to what happens in the Iraq hearings, than the other two. Scholars in discourse theory focus more on language as a disciplining structure than on the agency of actors speaking. The framing analyst shows a particular interest in what happens in the interaction, zooming in on the details of the exchanges between different actors: what is being articulated, what is not? The narrative analyst, finally, is interested in the interaction as well, but primarily focuses on the manner in which events, settings and characters beyond the interactional context can be subsumed under a particular plot, whilst wondering about the inequalities in access to the storytelling stage and the silencing of particular possible stories.

Second, the choice for a particular approach also lies with the research aim. There are differences between the approaches presented as well. Discourse analysis typically aims at deconstructing or understanding of what structures of linguistic power are in place, and explaining how particular policy decisions, institutionalization of rules and regulations come about. Framing analysis helps to better understand how interactions work, and how identities and relationships develop within these interactions. Narrative analysists try to see how particular storytellers emplot events, settings and characters into particular, and with what consequences for sense made of what has been or is still happening.

Third, the type of data that one will analyze. In the study of policy, a discourse analyst unlikely only focusses on a small piece of a conversation. For example, Foucault was famously uninterested in individuals or the details of social interactions. For this type of analysis typically a longer time frame is necessary, and a set of different types of documents (policy documents, newspapers, social media, perhaps in combination with interviews) from which discourses can be reconstructed. By contrast, framing analysists are interested in the fine grain of everyday conversations, how issues, relations and processes are framed and reframed in interaction, and they can offer discourse analysists a very different perspective on social order and change. For this type of analysis, participatory observations but also shadowing and more ethnographic data are more appropriate. This is also the case for scholars analyzing storytelling who are interested in how stories are performed in relation to their contexts, how they reproduce or are built out of (elements of) other stories, disappear and sort effect. Some understandings use naturally occurring conversations in everyday life and institutional situations while others use conversations that are generated specifically for the research project such as interviews or focus group discussions.

Fourth, by the selection of literature, one positions oneself within a certain disciplinary and theoretical tradition. In a way, this is about engaging a conversation with a specific scientific community. This could be all sorts of theories, for example coming from organizational studies, about policy change and stasis, or critical theories, for example on post-colonialism, gender and queer theories and so on. These theories may guide research questions and the selection of specific interpretive approaches. As we saw, each of the interpretive approaches described in this paper also has its theoretical roots. In themselves, they have also led to development of new theories. Discourse analysis comes out from political sciences, philosophy and linguistics. Theories of legitimacy and democracy and theories in international relations have been developed through discourse analysis. Framing analysis has been used more in conflict studies, social psychology and social movement studies (mobilization, escalation, seduction, risk communication). Storytelling, which also has some of its roots in (socio)-linguistics (Labov Citation1972), has a stronger embedding in organizational studies, where it seems to have replaced previously popular concepts such as organizational culture (Czarniawska 1997). Part of deciding ‘which approach is appropriate’ is also deciding about which conversation one wants to join, which does not stand in the way of attempting to combine approaches to enrich our understanding. When used for the critical analysis of policy, each approach does well by looking for ways in which power works through language and how (in)equalities are (re)produced and might in that way be useful for new critical analyses that draw on gender studies, post colonialism and theories of justice (e.g. Ahmed Citation2023; Laruffa and Hearne Citation2023).

To conclude, three decades after the argumentative turn in policymaking and planning, this paper assembled some distinct perspectives into a heuristic that may help to start thinking about what interpretive approach, or combination of approaches, may help to conduct critical policy research. While there are good reasons to choose for a certain approach, we believe it is useful for researchers to study and read broadly beyond them. It is not obvious that researchers new to critical, interpretive policy analysis will get acquainted with multiple approaches presented side-by-side (Fischer and Forester Citation1993; Wagenaar Citation2011; Yanow Citation2000), let alone in comparison. We aimed to renew fruitful deliberations about the rich variety of approaches and enable a more deliberate understanding for scholars and students in their selection or combination of approaches. This is not an exhaustive attempt to come to closure or to silence confrontations and discussions, between or within approaches. Indeed, we hope that readers will feel more eager than ever to broaden their analytical reach and study all three approaches and others we did not discuss here. CPS, as a journal, has and will no doubt contribute to this endeavor. We also hope and trust that with unfolding the possible points of convergence and divergence we contribute to developing new research frontiers and support the work of new generations talented interpretive students.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants of panel ‘Framing the future’ at the Interpretive Policy Analysis Conference 2017, anonymous reviewers and editor Regine Paul for their very helpful suggestions in developing this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Merlijn van Hulst

Merlijn van Hulst is an associate professor at Tilburg University. His research focuses on the work practices employed in the governance of public challenges. He has studied the practices of civil servants, police officers and neighborhood actors. In addition, he has studied storytelling in local government and at the police. Furthermore, he specializes in interpretive analyses, narrative and frame analysis in particular, and in ethnographic fieldwork.

Tamara Metze

Tamara Metze is full professor in Public Administration at the Faculty of Technology, Policy and Management (TBM, TU Delft). In her research, she focusses on emerging conflicts and transdisciplinary collaborations in the governance of sustainability transitions. Metze is a member of the college of the International Public Policy Association and principal investigator of the Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Metropolitan Solutions.

Art Dewulf

Art Dewulf obtained a PhD in Organisational Psychology (Leuven) and is Personal Professor of “Sensemaking and decision-making in policy processes” at the Public Administration and Policy group (Wageningen University). He studies complex problems of natural resource governance with a focus on interactive processes of sensemaking and decision-making in water and climate governance.

Jasper de Vries

Jasper de Vries is associate professor at the Landscape Architecture and Spatial Planning Cluster of Wageningen University. His interests are in the role of trust in area-based processes, communication and participation processes in environmental governance and sustainable agriculture.

Severine van Bommel

Severine van Bommel, Senior Lecturer at the University of Queensland’s School of Agriculture and Food Sustainability, specializes in rural development and agricultural extension. Taking an interpretive approach, her research focuses on the integration of local knowledge into sustainable development strategies. Committed to empowering farmers and promoting social equity, her work shapes inclusive approaches to global agricultural development and natural resource management.

Mark van Ostaijen

Mark van Ostaijen is an assistant professor affiliated to the Department of Public Administration and Sociology, Erasmus University Rotterdam. He is managing director of the Leiden-Delft-Erasmus centre Governance of Migration and Diversity and coordinates several research projects which investigate how diversity is being done.

Notes

1. Browsing the most cited articles in CPS of the last 3 years, we encounter range of articles using narrative, framing or discourse analysis.

2. We do not aim to give an overview of the whole literature or work with all strands available. In our discussion of narrative analysis, for instance, we do not get into a discussion of the so-called Narrative Policy Framework, which we do not consider an interpretive (sub-)approach. This has been extensively discussed in CPS before (Volume 9, Issue 3).

References

- Acosta, M., M. van Wessel, S. van Bommel, E. L. Ampaire, L. Jassogne, and P. H. Feindt. 2020. “The Power of Narratives.” Development Policy Review 38 (5): 555–574. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12458.

- Ahmed, B. 2023. “Decolonizing Policy Research as Restorative Research Justice.” Critical Policy Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2022.2158481.

- Bacchi, C. 2009. Analysing Policy: What’s the Problem Representation to Be. Australia: Pearson Education.

- Benford, R. D., and D. A. Snow. 2000. “Framing Processes and Social Movements.” Annual Review of Sociology 26 (1): 611–639.

- Bevir, M., and R. Rhodes. 2006. “Defending Interpretation.” European Political Science 5 (1): 69–83. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.eps.2210059.

- Boje, D. M. 1991. “The Storytelling Organization.” Administrative Science Quarterly 36 (1): 106–126. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393432.

- Chong, D., and J. N. Druckman. 2007. “Framing Theory.” Annual Review of Political Science 10:103–126.

- de Freitas Boullosa, R., R. Paul, and T. Smith-Carrier. 2023. “Democratizing Science is an Urgent, Collective, and Continuous Project: Expanding the Boundaries of Critical Policy Studies.” Critical Policy Studies 17 (1): 1–3.

- de Vries, J. R., P. Roodbol-Mekkes, R. Beunen, A. M. Lokhorst, and N. Aarts. 2014. “Faking and Forcing Trust: The Performance of Trust and Distrust in Public Policy.” Land Use Policy 38:282–289.

- Dewulf, A., and R. Bouwen. 2012. “Issue Framing in Conversations for Change.” The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 48 (2): 168–193.

- Dewulf, A., M. Brugnach, C. J. A. M. Termeer, and H. Ingram. 2013. “Bridging Knowledge Frames and Networks in Climate and Water Governance.” In Water Governance as Connective Capacity, edited by J. Edelenbos, N. Bressers, and P. Scholten, 229–247. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Dewulf, A., B. Gray, L. Putnam, R. Lewicki, N. Aarts, R. Bouwen, and C. van Woerkum. 2009. “Disentangling Approaches to Framing in Conflict and Negotiation Research.” Human Relations 62 (2): 155–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726708100356.

- Dewulf, A., T. Karpouzoglou, J. Warner, A. Wesselink, F. Mao, J. Vos, P. Tamas, et al. 2019. “The Power to Define Resilience in Social–Hydrological Systems: Toward a Power‐Sensitive Resilience Framework.” WIREs Water 6 (6): 210.

- Dewulf, A., M. Mancero, G. Cárdenas, and D. Sucozhanay. 2011. “Fragmentation and Connection of Frames in Collaborative Water Governance: A Case Study of River Catchment Management in Southern Ecuador.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 77 (1): 50–75.

- Durose, C., and V. Lowndes. 2023. “Gendering Discretion: Why Street-Level Bureaucracy Needs a Gendered Lens.” Political Studies 00323217231178630. https://doi.org/10.1177/00323217231178630.

- Entman, R. M. 1993. “Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm.” Journal of Communication 43 (4): 51–58.

- Fairclough, N. 1992. Discourse and Social Change. Cambridge: Polity.

- Fairclough, N. 2013. “Critical Discourse Analysis and Critical Policy Studies.” Critical Policy Studies 7 (2): 177–197.

- Fischer, F. 2003. Reframing Public Policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fischer, F., and J. Forester. 1993. The Argumentative Turn in Policy Analysis and Planning. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Fischer, F., and H. Gottweis. 2012. “Introduction.” In The Argumentative Turn Revisited, edited by F. Fischer and H. Gottweis, 1–30. London: Duke University Press.

- Fischer, F., D. Torgerson, A. Durnová, and M. Orsini, Eds. 2015. Handbook of Critical Policy Studies. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Forester, J. 1993. “Practice stories.” In The Argumentative Turn in Policy Analysis and Planning, edited by F. Fischer and J. Forester, 186–210. London: Duke University Press.

- Glynos, J., and D. Howarth. 2007. Logics of Critical Explanation in Social and Political Theory. London: Routledge.

- Griggs, S., and D. Howarth. 2013. The Politics of Airport Expansion in the United Kingdom. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Griggs, S., and D. Howarth. 2019. “Discourse, Policy and the Environment.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 21 (5): 464–478.

- Hajer, M. A. 1995. The Politics of Environmental Discourse. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Hajer, M., M. A. Hajer, and H. Wagenaar. 2003. Deliberative Policy Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Howarth, D. 2010. “Power, Discourse, and Policy.” Critical Policy Studies 3 (3–4): 309–335.

- Jorge, R. R. 2009. “Sociological Discourse Analysis: Methods and Logic [71 Paragraphs].” Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research 10 (2): Art. 26. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0902263

- Keller, R. 2012. Doing Discourse Research: An Introduction for Social Scientists. London: Sage.

- Labov, W. 1972. Language in the Inner City. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Laclau, E., and C. Mouffe. 1985. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy. London: Verso.

- Laruffa, F., and R. Hearne. 2023. “Towards a Post-Neoliberal Social Policy: Capabilities, Human Rights and Social Empowerment.” Critical Policy Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2023.2232432.

- Li, Y., and H. Wagenaar. 2019. “Revisiting Deliberative Policy Analysis: Introduction.” Policy Studies 40:427–436.

- Metze, T. 2018. “Framing the Future of Fracking.” Journal of Cleaner Production 197:1737–1745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.04.158.

- Metze, T., and J. Dodge. 2016. “Dynamic Discourse Coalitions on Hydro-Fracking in Europe and the United States.” Environmental Communication 10 (3): 365–379.

- Miller, H. T. 2020. “Policy Narratives: The Perlocutionary Agents of Political Discourse.” Critical Policy Studies 14 (4): 488–501.

- Miller, H. T., and R. Lofaro. 2023. “Political contestation in policy implementation.” Critical Policy Studies 17 (1): 43–62.

- Mishler, E. 1986. The Analysis of Interview-Narratives. edited by T. Sarbin, 233–255. New York, NY: Praeger.

- Ospina, S. M., and J. Dodge. 2005. “It’s About Time: Catching Method Up to Meaning—The Usefulness of Narrative Inquiry in Public Administration Research.” Public Administration Review 65 (2): 143–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2005.00440.x.

- Riessman, C. 2008. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences. London: Sage.

- Roe, E. 1994. Narrative Policy Analysis. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Schön, D., and M. Rein. 1994. Frame Reflection. New York: Basic Books.

- Smith, B. H. 1980. “Narrative Versions, Narrative Theories.” Critical inquiry 7 (1): 213–236.

- Smith Ochoa, C. 2020. “Trivializing Inequality by Narrating Facts: A Discourse Analysis of Contending Storylines in Germany.” Critical Policy Studies 14 (3): 319–338.

- Stone, D. A. 1997. Policy Paradox. New York: Scott.

- Tierney, K., C. Bevc, and E. Kuligowski. 2006. “Metaphors Matter: Disaster Myths, Media Frames, and Their Consequences in Hurricane Katrina.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 604 (1): 57–81.

- Tversky, A., and D. Kahneman. 1986. “Rational Choice and the Framing of Decisions.” The Journal of Business 59 (4): S251–S278.

- van Bommel, S., and M. van der Zouwen. 2013. “Creating Scientific Narratives.” In Forest and Nature governance. Arts et Al, edited by B. Arts, J. Behagel, S. Van Bommel, J. De Koning, and E. Turnhout, 217–239. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Van den Brink, M. and T. Metze. 2006. Words Matter in Policy and Planning. Utrecht: Netherlands Graduate School of Urban and Regional Research.

- Van Hulst, M. 2012. “Storytelling, a Model of and a Model for Planning.” Planning Theory 11 (3): 299–318.

- Van Hulst, M., and D. Yanow. 2016. “From policy ‘frames’ to ‘framing’: Theorizing a More Dynamic, Political Approach.” The American Review of Public Administration 46 (1): 92–112.

- Van Lieshout, M., A. Dewulf, N. Aarts, and C. Termeer. 2017. “The Power to Frame the Scale?” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 19 (5): 550–573.

- van Ostaijen, M. 2016. “Between Migration and Mobility Discourses.” Critical Policy Studies 11 (2): 166–190.

- van Ostaijen, M. 2020. “Legitimating Intra-European Movement Discourses: Understanding Mobility and Migration.” Comparative European Politics 18 (1): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-019-00152-x.

- Wagenaar, H. 2011. Meaning in Action. London: ME Sharpe.

- Weick, K. E. 1995. Sensemaking in Organizations. London: Sage.

- Wolf, E. E. A., and W. Van Dooren. 2017. “How Policies Become Contested: A Spiral of Imagination and Evidence in a Large Infrastructure Project.” Policy Sciences 50 (3): 449–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-017-9275-3.

- Yanow, D. 1993. “The Communication of Policy Meanings.” Policy Sciences 26 (1): 41–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01006496.

- Yanow, D. 1995. “Practices of Policy Interpretation.” Policy Sciences 28 (2): 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00999671.

- Yanow, D. 2000. Interpretive Policy Analysis. London: Sage.

- Yanow, D. 2007. “Interpretation in Policy Analysis.” Critical Policy Analysis 1 (1): 110–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2007.9518511.