Abstract

The literature widely reports that pre-service teachers repeatedly demonstrate inadequate argumentation skills. Through a mixed-methods research approach, this study investigated the effectiveness of a holistic online scaffolding design for guiding the development of pre-service teachers’ argumentation skills. Participants were randomly assigned to either a control or experimental group and then applied argumentation skills to solve case-based problem scenarios on teaching methods for two weeks. The experimental group had a significant improvement in the following argumentation skills: evidence, alternative theory, and counterargument. Qualitative data collected shows diverse metacognition concerning argumentation skills within experimental group. This study suggests that embedding a holistic online scaffolding approach into teacher training programs for the development of argumentation skills offers meaningful learning opportunities for pre-service teachers.

1. Introduction

Argumentation skills are recognized as a key educational goal in preparing students for academic and professional roles (Khishfe, Citation2022; QAA, 2014; Rapanta et al., Citation2021; Sadler, Citation2017; Zohar & Nemet, Citation2002). Application of argumentation skills involves developing a claim, supporting it with reasons and evidence, and thinking of alternative and counter perspectives to this claim (Kuhn, Citation1991). Thus, argumentation skills serve as a means for testing uncertainties, deriving meaning, and attaining a more profound comprehension on the issue under examination (Jeong & Joung, Citation2007). Argumentation skills have been shown as beneficial in enhancing conceptual change (Schwarz, Citation2009), co-construction of disciplinary understanding (Nussbaum, 2008), epistemic thinking (Asterhan & Schwarz, Citation2016), higher-order thinking skills including decision making (Torun, 2019), problem solving (Cho & Jonassen, Citation2002), and critical thinking (Sanders et al., Citation2009).

As future teachers, pre-service teachers are expected to not only model argumentation skills in classrooms but also to diagnose their students’ current levels in argumentation skills and guide the students for improving these skills (Lytzerinou & Iordanou, Citation2020; Osborne et al., Citation2004). Several lines of evidence suggest that lacking sufficient argumentation skills is one significant barrier for pre-service teachers to carry these skills into classrooms (Garcia-Mila et al., Citation2023; Jonassen & Kim, Citation2010; Mcdonald, 2014). Consequently, pre-service teachers must hold a certain level of mastery in argumentation skills to successfully fulfill these responsibilities (Simon et al., Citation2006). Argumentation skills are also foundational for pre-service teacher proficiency (Wess et al., Citation2023), as they can empower pre-service teachers to make informed decisions in their teaching practices (Reynolds et al., Citation2019), to deal with moral issues and dilemmas (Özçinar, Citation2015) and to solve complex problems such as classroom management (Oh & Jonassen, Citation2007). However, despite its importance, a considerable amount of literature has revealed that pre-service teachers have weak argumentation skills (Aydeniz & Gürçay, Citation2013; Garcia-Mila et al., Citation2023; Lytzerinou & Iordanou, Citation2020; Martín-Gámez & Erduran, Citation2018; Reynolds et al., Citation2019; Xie & So, Citation2012). Therefore, it is important to understand the ways to better support pre-service teachers’ argumentation skills (Garcia-Mila et al., Citation2023).

During their engagement with argumentation skills, pre-service teachers are likely to encounter various difficulties, possibly because of their different knowledge levels in argumentation skills, or the process of learning these skills itself (Oh & Jonassen, Citation2007). One possible approach to support the development of argumentation skills and minimize the challenges pre-service teachers encounter is integrating a scaffolding strategy (Kim et al., Citation2018). Scaffolding offers a temporary support on which pre-service teachers can improve their proficiency in argumentation skills (Andriessen, Citation2006). With the growing prominence of online learning, integrating scaffolding with online settings for facilitating higher-order thinking skills such as argumentation has become important (Noroozi, Citation2020). Due to its complex and ill-structured nature, without appropriate guidance and facilitation, students are less likely to effectively achieve and engage with argumentation skills in online settings (Noroozi & McAlister, Citation2017). Therefore, this study focuses on scaffolding in online learning environments, referred to as online scaffolding.

To date, several studies have investigated whether online scaffolding improves argumentation skills within pre-service teacher context. Although these studies suggest that online scaffolding can be an effective strategy for the development of pre-service teachers’ argumentation skills (e.g. Özçinar, Citation2015; Stegmann et al., Citation2012; Su & Long, Citation2021; Zheng et al., Citation2023), several issues remain unanswered. Previous studies have not adopted a comprehensive approach to the development of argumentation skills in online scaffolding designs (Lin et al., Citation2012). This lack of a comprehensive approach to argumentation skills continues to persist in the related literature (Ucar-Longford et al., in press). For example, Uçar and Demiraslan Çevik (Citation2020) and Weinberger et al. (Citation2010) provided online scaffolding which targets the connections between argumentation skills through argument maps and scripts. This kind of scaffolding is particularly useful in visualizing abstract nature of argumentation skills through the step-by-step applications (Hoffman, 2011). Similarly, Oh and Jonassen (Citation2007) used sentence openers to scaffold only pre-service teachers’ articulation of argumentation skills. However, such scaffolding design applications focus solely on a single aspect of skill development in argumentation. Therefore, these studies are often limited in meeting the needs of students with different levels of capability in argumentation skills (Puntambekar, Citation2021). Secondly, most of the previous studies have investigated the improvement in total argumentation skills scores (Özçinar, Citation2015; Stegmann et al., Citation2012; Su & Long, Citation2021; Uçar & Demiraslan Çevik, Citation2020; Zheng et al., Citation2023). Whilst this approach can help us understand the effectiveness of scaffolding intervention, it does not reflect the range of specific knowledge and skills acquired in argumentation (Arum & Roksa, Citation2011). In response to these knowledge gaps, we evaluated the effectiveness of a holistic online scaffolding design in terms of the learning outcomes related to argumentation skills. As we are interested in deeper understanding rather than just operational abilities, this investigation provides the change in specific argumentation skills, as well as identifying what types of metacognitions related to argumentation skills pre-service teachers demonstrate after the online scaffolding. Recently, a considerable body of evidence has shown a strong relationship between metacognition and argumentation skills (Iordanou, Citation2022; Jin & Kim, Citation2021; Öztürk, Citation2017). However, there is dearth of research exploring metacognition related to argumentation skills in online scaffolding literature (Jin & Kim, Citation2021). Existing accounts have reported that although pre-service teachers can practice argumentation skills at a cognitive level, they are unable to verbalize which argumentation skill they used, or what counts as qualified evidence (Zhao et al., Citation2021, i.e. metacognitive skills/awareness). Accordingly, the research questions that guide our study are as follow:

To what extent does online scaffolding develop pre-service teachers’ argumentation skills?

What types of metacognitions related to argumentation skills do pre-service teachers demonstrate after online scaffolding?

2. Background

2.1. Argumentation skills

To understand argumentation skills, it is important to start by defining what an argument is. Argument can be broadly defined as a product comprising of, at minimum, a claim and its justification (Kuhn & Udell, Citation2007). An argument becomes more complex when it includes opposite and alternative claims as well as their justifications (Glassner, Citation2017). In the present study, we employed Kuhn’s (Citation1991) argumentation skills framework, which defines five specific skills which allows an individual to fully engage with identifying, creating and analyzing arguments (see ).

Table 1. Argumentation skills framework by Kuhn (Citation1991).

Among these five skills, causal theory is the simplest level of skill as it only requires one to provide reasons for the claim (Kuhn, Citation1991). Compared to causal theory, skill to evidence is a relatively more sophisticated because it requires not only understanding the concept of evidence but also evaluating the strength and relevance of evidence (Miralda-Banda et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, a more proficient use of evidence demands individuals to employ it for different purposes, including supporting or rebutting a theory (Iordanou & Constantinou, Citation2014). Finally, alternative theory, counterargument, and rebuttal are classified as advanced argumentation skills as they involve exploration of the claim from multiple perspectives (Kuhn, Citation1991).

Previous research indicates that pre-service teachers often exhibit limited abilities in creating and recognizing argumentation skills (Garcia-Mila et al., Citation2023; Lytzerinou & Iordanou, Citation2020; Xie & So, Citation2012). Additionally, there is a common struggle among pre-service teachers to differentiate between theory and evidence (Aydeniz & Gürçay, Citation2013), as well as incorporate complex skills such as alternative theory, counterargument and rebuttal (Martín-Gámez & Erduran, Citation2018). Researchers argue that acquisition of argumentation skills requires a metacognition of these skills (Kuhn, Citation2005; Zohar, Citation2007). Thus, in the next section, we explain the connections between argumentation skills and metacognition.

2.2. Metacognition for argumentation skills

Metacognition has two facets, ones’ knowledge about the cognition and the regulation of the cognition (Flavell, Citation1979). The knowledge about cognition encompasses four types of knowledge in argumentation skills: declarative, procedural, epistemological and conditional (Jiménez-Aleixandre, Citation2007; Rapanta et al., Citation2013; Zohar, Citation1999). The declarative knowledge is related to knowing each argumentation skill (causal theory, evidence, alternative theory, counterargument, and rebuttal). The procedural knowledge is about knowing how to generate each argumentation skill. Finally, the epistemological knowledge refers to knowing the standards and quality considerations about argumentation skills. For example, epistemological knowledge on evidence pertains to knowing what counts as evidence, if the evidence is strong, or it is related to causal theory, if evidence provided for the alternative and counter perspectives (Kuhn et al., Citation2013). Epistemological knowledge is stated as fundamental to have an advanced understanding of argumentation skills (Iordanou, Citation2022). Finally, the conditional knowledge is the knowledge about when or why to use argumentation skills (Schraw et al., Citation2006). Conditional knowledge is also associated with the disposition of argumentation skills (Reznitskaya et al., Citation2009).

Regulatory aspect of metacognition involves planning, monitoring, and evaluating (Jacobs & Paris, Citation1987). Planning involves thinking about goal setting, deciding required resources, and planning how to perform argumentation skills. Monitoring implies one to assess and to monitor their comprehension of argumentation skills. Finally, evaluating is the judgment on if the goals related to argumentation skills are achieved or the strategies used for learning. Previous research highlights that metacognitive regulation is interrelated with metacognitive knowledge (Schraw, Citation1994; Teng, Citation2020). Exemplifying from an argumentation skills perspective, this means that if a person knows that the quality of evidence changes according to types of evidence (epistemological knowledge and declarative knowledge of argumentation skills) then that person would monitor the quality of evidence and select higher quality evidence (Jin & Kim, Citation2021).

2.3. Online scaffolding

Scaffolding is traditionally defined as a process in which an expert, generally a teacher, supports students toward the learning task until they become independently capable of the intended task (Hannafin & Land, Citation2000). Scaffolding is often conceptualized based on Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) which defines a gap between what student can accomplish with and without assistance (Vygotsky, 1924/Citation1978). Assistance involves a dynamic assessment of each student’s performance to determine their ZPDs and scaffolding which match with these ZPDs. However, in classrooms with a large cohort of students with different ZPDs, it often would be an unrealistic expectation for a teacher to be able to deliver adequate bespoke scaffolding for each student. As a result, source of scaffolding has been broadened to include other forms of media such as text, visual, audio or tools (Belland, Citation2016). This scaffolding designed based on an expert understanding provides a generic structure to support novice students and is delivered through online settings (Sharma & Hannafin, Citation2007). This type of scaffolding is commonly referred to as online scaffolding.

Online scaffolding comprises five functions: conceptual, procedural, reflective and strategic (Kim & Hannafin, Citation2011). Conceptual scaffolding supports students with necessary information, concepts, or facts related to learning topic, basically on what to know to fulfill that task. Conceptual scaffolding has been applied in various forms to support students to consider components of argumentation skills. Providing students with explanations of each argumentation skill (Lin et al., Citation2020) or the examples of argumentation skills (Oh & Kim, Citation2016) are among the common conceptual scaffolding approaches. Another way to incorporate conceptual scaffolding involves expert modeling in which an expert explains and model each argumentation skill on a video (Hefter et al., Citation2018). Procedural scaffolding guides students through the steps or procedures to complete a task or apply a skill. Procedural scaffolding can be in the form of question prompts directing students on how to generate argumentation skills (Tawfik et al., Citation2018) or sentence openers (Schnaubert & Vogel, Citation2022). Additionally, the scaffolding can be delivered through argument maps which invites students to generate and connect each argumentation skill (Uçar & Demiraslan Çevik, Citation2020). Reflective scaffolding encourages students to evaluate and reflect on their own thinking. One way to incorporate reflective scaffolding is using question prompts which assists students to evaluate and monitor the quality of argumentation skills they generated (Kim et al., Citation2022). Further methods include implementing check-lists for students to compare their argumentation skills against quality criteria or goal setting prompts (Kim & Hannafin, Citation2016). Finally, strategic scaffolding guides students on the ways to analyze and approach to the learning task. Strategic scaffolding is often applied as chunking the argumentation skills tasks to decrease complexity (Belland et al., Citation2015) or hints on how to turn the gathered information into claim or evidence (Kim et al., Citation2022). In next section, we explain a holistic approach to designing online scaffolding to develop argumentation skills.

2.4. Toward a holistic online scaffolding design

Online scaffolding is often premised on Vygotsky’ Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) (1924/1978). ZPD describes a scaffolding process based on the interactions between teacher and student. In this process, the teacher serves as the source of the support, adapting this support to match students’ ZPD. As the student progresses and demonstrates increased competency, the teacher gradually withdraws this support, ultimately transferring responsibility or learning to the student. While ZPD emphasizes teacher’s role in these interactions, it assigns a passive role to the student in the scaffolding process (Lefstein et al., Citation2018). However, online scaffolding has more self-directed nature where teacher is not the active provider of this assistance, instead students undertake dual roles as learner and mediator roles with their interactions with the scaffolding support (Doo et al., Citation2020). Therefore, ZPD approach to online scaffolding can be limited in explaining how to adjust the support based on students’ needs (Puntambekar, Citation2021).

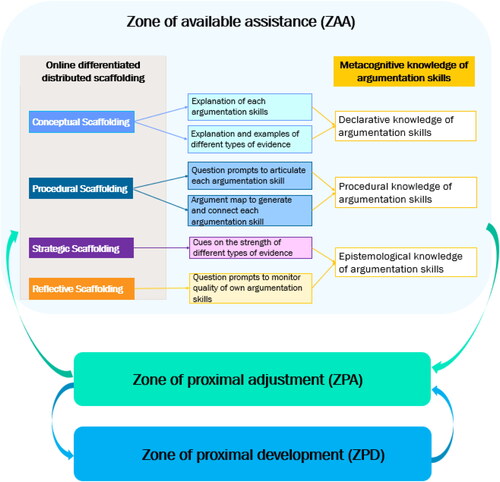

In response to this issue in ZPD, Luckin (Citation2010) expanded ZPD with Zone of available assistance (ZAA) and zone of proximal adjustment (ZPA), a framework that emphasizes the importance of designing a dynamic and personalized online scaffolding experience. ZAA refers to a selection of scaffolding functions which learners may need to acquire the targeted skills or knowledge, while ZPA describes students choosing appropriate scaffolds based on their current needs from ZAA. The concepts of ZAA and ZPA attribute online scaffolding to a self-directed learning aspect rather than a social interaction between a more knowledgeable agent (teacher or peer) and learner. This allows students define the level of their interactions with online scaffolding in ZAA (Puntambekar, Citation2021). Luckin’s framework (Citation2010) to online scaffolding can be effective in promoting an active interaction process between the students and the scaffolding (Jose, Citation2016). This approach has also been associated with facilitating students to take more ownership and autonomy in their learning (Suárez et al., Citation2018).

To be able design an effective ZAA, it is important to consider what aspects of argumentation skills to scaffold and how to scaffold (Puntambekar, Citation2021). In this research, we adopted a distributed online scaffolding approach based on a differentiated method in the design of ZAA (Tabak, Citation2009). Distributed scaffolding defines a collection of various forms of scaffolds working together to assist leaners’ different needs in a learning task (Puntambekar, Citation2021). In differentiated distributed scaffolding approach, each scaffolding function targets a separate aspect of a particular learning task through one or more support (Tabak, Citation2009).

We defined pre-service teachers’ needs based on the reported weakness in their argumentation skills in section 2.1. To address these needs, we designed conceptual, reflective, strategic, and procedural online scaffolding functions (Belland, Citation2016) and associated each function with metacognitive knowledge of argumentation skills (declarative, procedural, and epistemological) (Rapanta et al., Citation2013). visualizes the online scaffolding applied in this research.

Conceptual scaffolding was incorporated to assist declarative knowledge of argumentation skills. We have provided two conceptual scaffolds. The first one offers prompts through the explanation of argumentation skills in order to address pre-service teachers’ need related to clarifying what these skills composes of Weng et al. (Citation2017). The second one provides examples and explanations of various types of evidence to strength pre-service teachers’ understanding concept of evidence (Miralda-Banda et al., Citation2019). Procedural scaffolding supported the procedural knowledge of argumentation skills through the question prompts to articulate argumentation skills (Kuhn, Citation1991) and argument map to connect these skills (Uçar & Demiraslan Çevik, Citation2020). Finally, strategic, and reflective scaffoldings targeted epistemological knowledge of argumentation skills. Strategic scaffolding took the form of visual cues aimed at informing pre-service teachers about the strengths of different types of evidence (Miralda-Banda et al., Citation2019). Reflective scaffolding was introduced through self-monitoring question prompts designed to help students evaluate the quality of their argumentation skills (Glassner, Citation2017).

Exposing students to the same amount and type of scaffolding while it is no longer needed can cause a cognitive overload and hinder the learning (Belland, Citation2014). However, previous studies generally provided students with a sustained scaffolding where the support remains consistent regardless their needs (Ucar-Longford et al., in press). This kind of design fails to reflect the fading and transfer of responsibility aspects of online scaffolding (Kim et al., Citation2018). To address these shortcomings, we embedded each scaffolding support into buttons and provided labels on what kind of support each button involves. By clicking on these buttons, students can view the scaffolding they need from the ZAA. This would allow students to have greater control over which supports they interacted with based on their individual needs.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research method

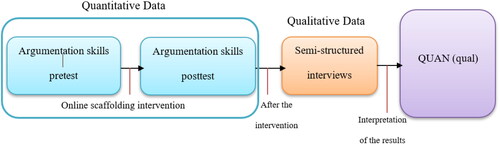

The study uses an explanatory mixed methods design to gain a detailed understanding of how online distributed scaffolding supports pre-service teachers’ learning of argumentation skills (see in ). In explanatory mixed methods, the researcher integrates the qualitative part after the quantitative data collection to build on the quantitative results (Plano Clark et al., Citation2013). Accordingly, we followed up quantitative data derived from the true-experimental design in the form of pretest and post-test control group through the qualitative data obtained from semi-structured interviews.

3.2. Participants and context

ParticipantsFootnote1 of the study consisted of 20 (12 female, 8 male) pre-service teachers who are studying at Computer Education and Instructional Technology in Turkey. All participants were either taking or had previously taken the Teaching Methods course and Special Teaching Methods course which focuses on learning and teaching theories, teaching methods, strategies and techniques, and the research applied in computer science education. The majority of the participants were 3rd year (n = 12) and 4th year (n = 6) undergraduates while there were two participants in the first semester of their Masters’ degree program. 12 of the participants had teaching experience up to one year as a part of their internship or voluntary based work while remaining 8 participants did not have any teaching experience. Only one participant had experience with argumentation skills as a part of a selective module. Pre-service teachers were randomly assigned to the control group or the experimental group in equal numbers (n = 10 per group). In the pretest, there was no difference between experimental (M = 0.36) and control group (M = 0.40) regarding argumentation skills (p > 0.05).

3.3. Instruments

3.3.1. Argumentation skills test

Case scenarios were used as pretest and post-test to examine pre-service teachers’ argumentation skills quantitatively. These case scenarios describe a teacher who wants to choose an appropriate teaching method in the given context to achieve the learning objectives in Information Technologies and Software in 5th and 6th grades (10–12 years old) in Turkey (see Appendix A). Pre-service teachers were expected to choose a teaching method to address the learning objective considering the context given in the scenarios and discuss why that teaching method was appropriate to solve the problem. Both case scenarios were examined by two experts in computer science teacher education who agreed on appropriacy and authenticity of the cases to investigate pre-service teachers’ argumentation skills. The case scenarios did not include any explicit practice or naming of argumentation skills to prevent response shift bias from pretest to post-test (Howard, 1980).

3.3.2. Interviews

Semi-structured interviews were employed to explore and understand pre-service teachers’ metacognition of argumentation skills in experimental group after the intervention. Two pre-service teachers did not reply to the interview invitation. The interviews were conducted with 8 pre-service teachers in Turkish via online video conferencing tool Zoom and average the length of interviews was 30 min. Each interview was recorded and then transcribed. In the beginning of the interview, pre-service teachers were informed about the interview process and aims. Then, they were reassured of the confidentiality and secure storage of the interview data and informed that they can withdraw from the interview any time they want. One potential risk of semi-structured interviews is the possibility of the pre-service teachers’ inability to recall or impairment of their memories about their performance and interactions during the research due to the time delay between the actual activity and in-depth interviews (Veenman, Citation2005). Therefore, we presented the week 1 and week 2 screens of each participant as a cue to ease them to remember their interactions with the scaffolding, after the questions related to metacognitive knowledge of argumentation skills (Appendix B).

3.4. Procedure

Before launching the intervention, instructional instruments were piloted with a group of six individuals, consisting of three teachers and three newly graduated pre-service teachers, which we hoped this varying experience in the pilot group would bring diverse perspectives on the approachability of our instruments. This testing mainly focused on usability, accessibility, effectiveness, efficiency and learnability aspects in online learning environment, learning tasks (argumentation skills development and evaluation), online scaffolding and case scenarios (Lu et al., Citation2022). Based on the result of this test, we did the necessary revisions.

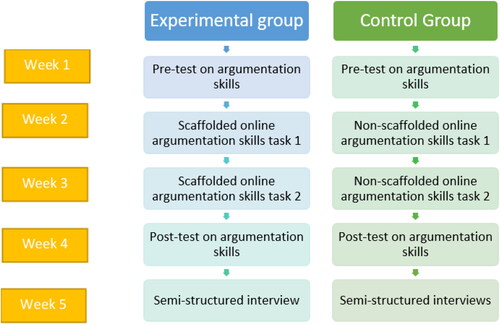

The study lasted 5 wk in total (). In the first week, all participants took the 40 min of pretest to assess argumentation skills. Following the pretest, online learning platform was introduced separately to both control and experimental groups. The open source and commonly used, Moodle platform, was used to deliver the intervention for both groups.

At the start of the study, both groups were introduced the interface and were given instructions on how to navigate and interact with the features. In this introduction, experimental group was provided an overview and explanation of each scaffolding embedded in the buttons. On Moodle platform, all groups engaged with the same tasks which were argumentation skills development and argumentation skills assessment. In argumentation skills development task, both groups were asked to answer case scenarios related to teaching methods. In this task, experimental group received scaffolding which guides them to apply argumentation skills in their answers to these case scenarios (section 3.2.1). However, the control group did not receive any explicit support on argumentation skills. In argumentation skills assessment task, both groups participated in peer feedback activity. In this task, participants were informed about the expectations on giving and receiving feedback. During argumentation skills assessment task, peer feedback groups were created randomly each week and participants worked anonymously to encourage providing honest and constructive feedback. In the fourth week, all participants took the post-test followed by an interview invitation for the experimental group. The interview date was scheduled with participants who volunteered. At the end of the research the control group was offered an hour of argumentation skills workshop to minimize any disadvantages due to the lack of access to the same materials as the intervention group.

3.5. Data analysis

For the first research question, to what extent does online scaffolding support pre-service teachers to learn argumentation skills, we assessed pre-service teachers’ argumentation skills quantitatively through the rubric developed by Uçar and Demiraslan Çevik (Citation2020). In the rubric, each criterion for the individual argumentation skill is presented in three levels of accuracy Level 0, Level 1, and Level 2 representing increasing levels of sophistication. Based on the rubric, each argumentation skill is scored according to which level it fell into. For example, if it was Level 1 evidence, then it was scored as 1. A worked example of rubric shared in Appendix C. An independent lecturer in computer education and instructional technology rated 20% of randomly selected post-tests. The results showed a good agreement between readers (Cohen’s к = 0.72). Then we compared the change in argumentation skills from pretest to post-test through a mixed-design analysis of variance via SPSS 28. Argumentation skills (causal theory, evidence, alternative theory, counterargument, and rebuttal), and test time (pretest and post-test) were dependent variables and intervention type (control group = not scaffolded and experimental group = scaffolded) was independent variable.

As to the second research question, what type of metacognition related to argumentation skills do pre-service teachers demonstrate after online scaffolding, transcripts from semi-structured interviews explored through thematic analysis approach. We analyzed the qualitative data thematically by using NVivo 12. For the thematic analysis, we followed Clarke and Braun’s 6 steps framework (2017): which are: familiarization with the data, producing initial codes, searching for the themes, reviewing the themes, defining, and naming themes and finally producing the report. The thematic analysis was based on deductive approach. By following these steps, we read all the data multiple times and highlighted some possible codes. This followed by re-reading the initial codes and quotes and matching them with the possible themes and sub-themes based on the literature review in 2.2. At the end of these steps, we obtained 2 major themes as metacognitive knowledge of argumentation skills and metacognitive regulation of argumentation skills. Themes, sub-themes, and codes are presented in Appendix D.

4. Results

4.1. RQ1: to what extent does online scaffolding develop pre-service teachers’ argumentation skills?

shows that in pretest, participants in both groups were able to produce causal theory, however, neither of the groups interacted with other skills such as evidence, alternative theory, counterargument, and rebuttal in the pretests. This suggests that in the beginning of the intervention, participants were pre-dominantly focused on justifying their own perspectives and probably did not have a clear concept of evidence to engage with this skill. In post-test, argumentation skills of control group remained almost the same, while the experimental group showed some improvement in their engagement with argumentation skills including evidence, alternative theory, counterargument, and rebuttal. This suggests that after the intervention, experimental group is likely to develop the concept of evidence and recognize the opposite and alternative perspectives. However, despite these improvements in argumentation skills, the application of alternative theory, counterargument and rebuttal remained low. To test if these patterns were statistically significant, we ran a mixed-design analysis of ANOVA.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of argumentation skills scores in pretest and post-test by groups.

The results of the mixed-design analysis of ANOVA () showed a significant main effect of time in groups’ argumentation skills F (1, 18) = 14.781, p = 0.01. Further, we discovered that this effect was qualified by a significant interaction in time x group F (1, 18) = 10.49, p = 0.005, and argumentation skills x time x group F (2.15, 38.85) = 3.03, p = 0.05. Then we conducted a post-doc analysis to delve into the results in detail.

Table 3. The results of mixed-design analysis of ANOVA.

4.2. RQ2: What type of metacognition related to argumentation skills do pre-service teachers demonstrate after online scaffolding?

This section provides the themes derived from the interview data of experimental group. The two themes of metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive regulation of argumentation skills were derived from the qualitative data analysis. Below we share the themes and sub-themes with the quotes in detail.

4.2.1. Metacognitive knowledge of argumentation skills

Explanations and descriptions of participants in experimental group revealed that they hold different types of metacognitive knowledge of argumentation skills including declarative, procedural, epistemological and conditional. We present subthemes and an example of participant’s comments below.

4.2.1.1. Declarative knowledge of argumentation skills

Participants demonstrated examples of various declarative knowledge during their talks about argumentation skills. For example, all participants were able to list the components of argumentation skills by using the specific terminology:

HocamFootnote2, for example, when developing an argument, we employ skills such as causal theory then evidence to support it, alternative theory, counterargument, and rebuttal to underpin a claim (Student 8).

So, the causal theory explains why the claim might be true. Evidence also tries to support these causal theories. There were different types of evidence, for example personal experience, analogy, or research results. In counterargument, we discuss situations in which this causal theory and evidence were weak. Alternative theory is similar to the counterargument, but it focuses on alternative perspectives and reasons for the claim. There was rebuttal to discuss against these alternative and opposing views. (Student 6)

4.2.1.2. Procedural knowledge of argumentation skills

Students exhibited examples of their knowledge on how to perform argumentation skills. Majority of the participants focused on how to obtain strong evidence to support their causal theories:

“How to develop a strong evidence? This requires scanning research papers and choosing the suitable one. I had a serious return from this as a skill (Student 2).”

I defend an opinion, so I provide the causal theory of defending that opinion. I tried to strengthen this theory through evidence from studies. Then I discuss the drawbacks and disadvantages of this theory and evidence in counterargument. Finally, I found the ways that I can rebut this counterargument again by supporting with the previous research. (Student 1)

4.2.1.3. Epistemological knowledge of argumentation skills

For many participants, the importance of providing relevant and strong evidence for supporting their theories became evident in the interviews:

Hocam, for instance, when developing evidence, that evidence has different degrees of strength. For example, an evidence based on scientific research is stronger evidence than the evidence from analogies or personal experiences which are more basic level. (Student 4)

For example, when we write a rebuttal or counterargument, I think it must be backed to evidence. There is an opposite view but why? Is there a point where this opposing view based on? Or it is purely a personal opinion? With this training, I saw that this questioning turned into a normal skill with me. Strong evidence must be asked for. (Student 3)

4.2.1.4. Conditional knowledge of argumentation skills

In this subtheme, many participants expressed future areas where they can use argumentation skills. These areas were mainly associated with their future career as a teacher. For example, to improve students’ critical thinking skills, “because argumentation skills offer critical and different views, in terms of students, I plan to use in teaching thinking skills for example regarding programming, it requires thinking different/multiple aspects. I believe it will develop both teachers and students in this regard (Student 3).”, to achieve higher level learning outcomes, “I will relate argumentation skills to higher level of learning outcomes. I do not think that I could apply argumentation skills in the learning outcomes in knowledge level…I can see myself using argumentation skills for teaching cognitive domains requiring higher levels of skill (Student 6).”, to support students’ meaningful learning, “when I become a teacher, if there is a topic that students do not understand or if students are not that actively engaging to involve students to lesson and improve their understanding of that topic I can incorporate argumentation skills. In this way I believe that I will use argumentation skills in future (Student 4).” and to make informed decision making in their pedagogical choices “thanks to the argumentation skills, I can plan like this before I go to class. What if my 5th grade students are 30 people, when I will explain this learning outcome, I think that whatever teaching method I use for this learning outcome will be useful or not useful, can I not work if this class is crowded, if there are any problems, I think I can clearly see this by using argumentation skills (Student 1).” Some participants also talked about the value of argumentation skills in daily life:

I think argumentation skills are really important for us in every aspect of life, or this is my personal opinion. This is not only in academic aspects and in work life, but in fact, we can use this method even in daily problems. Even when solving a problem… so when we are in trouble that we can’t solve it like this, it is easier to come to a conclusion by showing it like this and processing it step by step like this. (Student 5)

4.2.2. Metacognitive regulation of argumentation skills

Participants articulated diverse examples on the metacognitive regulation of argumentation skills during their engagement with the supports in weekly tasks. These examples included planning, monitoring, and evaluating. Below we share the examples each of these sub-themes.

4.2.2.1. Planning

Participants mainly reflected on their planning about what type of evidence required to support their causal theories and how they access it during the application of argumentation skills. One participant explained:

I tried to use various types of evidence in my argument. I especially focused on strong and the strongest types of evidence which I reached from articles and statistics. (Student 8)

4.2.2.2. Monitoring

Monitoring participants frequently talked about their monitoring when generating argumentation skills through online scaffolding. In this sub-theme, some students focused on their efforts to improve their skill to evidence by thinking the strength of evidence:

First week, I did not engage with the online scaffolding much, I used my personal experiences as evidence. Second week, I remember that in the feedback I got a comment on the strength of my evidence then I started to think of how my evidence is weaker and have looked at the support related to evidence. Then I realized that I was using the weakest evidence source. Then I asked myself how I can strengthen my evidence and then read through the related support more, and I went to YÖKSİSFootnote3 and searched for the studies that are suitable for my causal theory. (Student 1)

I can explain that first week, in the claim, for example, rather than using a bit more certain phrases I used evidence within the claim, I even used unnecessary words in evidence and counterargument. However, after reading this support I realized my these mistakes. As I practice by using the supports, I understood how I should express, how long or short my expressions should be. (Student 8)

4.2.2.3. Evaluating

It is worth noting that in this theme that although majority of the participants reported their confidence in application of argumentation skills such as causal theory and evidence, for some of them, counterargument and alternative theory were still difficult to generate:

First week, I had difficulty to develop strong evidence but through the support, scanning the articles and choosing the appropriate evidence, for example, gave me a serious return as a skill. I can develop claim causal theory and support it with evidence however I am not sure if I can do counterargument and alternative theory. (Student 7)

An interesting finding in this theme was the differences in the way participants used and valued the online scaffolding. For example, some participants explained that in the first week, they used online scaffolding for understanding argumentation skills however in the second week the reason for engagement with the scaffolding was for control purposes:

First week I needed to look at the support many times however, second week, this started to decrease. I looked at in the beginning and at the end. I believe as my thinking way adapted to argumentation skills, I did not require to use the supports much. I used them to control if what I did was suitable. (Student 2)

I looked at it in detail first week to understand how I cand develop however after examining it in detail first week, I focused on providing strong evidence and I did not need to look through this support second week. (Student 5)

First two weeks, I used the supports so heavily, if there was third and fourth weeks, I think I would use them heavily at those weeks as well. Maybe in last weeks I could ask the questions by myself. (Student 7)

5. Discussion

This research aimed to determine the effectiveness of a holistic online scaffolding design for developing argumentation skills in a pre-service teacher context. The study investigated the effectiveness of the online scaffolding design in two aspects: the change in the argumentation skills and metacognition related to argumentation skills.

The results show that implementation of online scaffolding led to a significant improvement in argumentation skills of experimental group whereas no change was observed in control group. This is in line with previous research which demonstrates the effectiveness of online scaffolding in improving argumentation skills (Jeong & Joung, Citation2007; Stegmann et al., Citation2012; Uçar & Demiraslan Çevik, Citation2020; Weinberger et al., Citation2010). Upon further investigation, a significant increase was noted in argumentation skills including the ability to present evidence, alternative theory, and counterargument in the experimental group. The qualitative results not only supported these quantitative findings but also expanded our understanding of these results. The qualitative findings reveal that pre-service teachers demonstrated diverse metacognitive knowledge regarding argumentation skills. This diversity implies a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of argumentation skills (Rapanta et al., Citation2013). This finding is also a promising sign that pre-service teachers in the experimental group not only applied argumentation skills at the cognitive level but also developed a sense of meta-level understanding of these skills (Kuhn, Citation2001).

The results related to metacognitive knowledge indicate that students were able to articulate declarative knowledge regarding argumentation skills. This was evidenced by their accurate use of terminology to talk about and define these skills. This result regarding declarative knowledge of argumentation skills is reassuring since previous studies drew the lack of such knowledge in these skills among pre-service teachers (Garcia-Mila et al., Citation2023; Zhao et al., Citation2021). Moreover, the results highlight that pre-service teachers were able to talk about procedural knowledge on how to generate argumentation skills. Finally, the findings indicate that pre-service teachers demonstrated epistemological knowledge on evidence standards, relevance, and the different functions it serves. Furthermore, students demonstrated an awareness of the significance of considering alternative and counter positions while engaging in argumentation skills.

These outcomes concerning procedural and epistemological knowledge are particularly important for two reasons. Firstly, the mastery of these two types of knowledge is considered more advanced compared to declarative knowledge, which involves remembering the each argumentation skill and their names (Hefter et al., Citation2014). Therefore, even two weeks after the intervention, pre-service teachers to be able to articulate procedural and epistemological knowledge regarding argumentation skills suggests a more in-depth development of these skills. Secondly, pre-service teachers’ articulation of these two types of knowledge indicates an important epistemological growth within the online scaffolding group (Iordanou, Citation2022). This is because experimental group transitioned from solely focusing on their own perspective to recognizing the existence of alternative and counter perspectives on the issue as well as openness of a claim to evaluation (Kuhn & Udell, Citation2007). Finally, participants’ comments also revealed that pre-service teachers in experimental group hold conditional knowledge on why and when to apply argumentation skills. Schunk (Citation2012) discusses that many students can apply declarative and procedural aspects of a task however it does not mean they can apply it appropriately without conditional knowledge. According to these results, we can infer that holistic online scaffolding design which includes various types of scaffolding to assist different aspects of metacognitive knowledge related to argumentation skills lead to a more comprehensive development of these skills.

In this study, holistic online scaffolding design was delivered through an adaptable approach. So, students had control over to determine the extent and type of scaffolding they need. The qualitative findings indicate that this online scaffolding design decision supports students to assume more ownership in learning argumentation skills. Furthermore, as students assume this ownership, they actively take dual roles as both learner and mediator when adjusting the scaffolding. This is evidence in the finding showing that participants transitioned from using online scaffolding naively to learn the terms and connections related to argumentation skills, to becoming more strategic and selective in their use of online scaffolding, which inclines with the findings by Sharma and Hannafin (Citation2005). This observation may support the hypothesis that online scaffolding approaches which give students greater control over customization of the support, not only empowers them to be more autonomous but also facilitates their adoption of sophisticated learning strategies over time (Lefstein et al., Citation2018). Additionally, the results also show that different degrees of dependencies on online scaffolding among the participants. While some participants shared their tendency to independent application of argumentation skills, others explained their dependency on the online scaffolding. This finding indicates that our online scaffolding design was effective in supporting students at various stages of argumentation skills development.

6. Limitations

Despite its promising findings about the effectiveness of a holistic online scaffolding designs for developing argumentation skills, we do acknowledge some limitations. A limitation of this study was the relatively modest sample size for the two groups and short study duration therefore perhaps a future study should look at larger experimental setting. Nevertheless, significant differences were found between the groups and the quantitative data was supplemented by qualitative data to provide more nuanced understanding as to why the quantitative differences were being found. Additionally, further work is needed to establish transfer aspect of argumentation skills in similar and different contexts. It would be valuable to test empirically whether pre-service teachers can transfer argumentation skills and, what aspects of argumentation skills are transferable.

7. Conclusion

This study set out to explore the effects of a holistic online scaffolding design approach on pre-service teachers’ argumentation skills. We found that online scaffolding design improved pre-service teachers’ argumentation skills including evidence, alternative theory, and counterargument. Findings also suggest that pre-service teachers were able to demonstrate multiple metacognition specific to argumentation skills.

Several implications can be derived from this study. Firstly, in order to support the development of higher-level argumentation skills, it is recommended that pre-service teachers should be provided with scaffolding specifically designed for these skills, rather than relying solely on active teaching methods such as case-based problem solving and peer feedback. Previous studies showed that pre-service teachers struggle with skill to evidence, alternative theory and counterargument (Garcia-Mila et al., Citation2023). However, the current results show that participants provided with the opportunity to engage in holistic scaffolding, exhibit a capacity for the development these skills. In addition, the results suggests that this holistic scaffolding approach not only improves pre-service teachers’ ability to apply argumentation skills at the procedural level but also supports the development of meta-level knowledge related to these skills (Iordanou & Constantinou, Citation2014). This has been shown as an important factor in pre-service teachers’ application of these skills in their future classrooms (Zohar, Citation2007). Taken together, these results highlight the importance of embedding a holistic approach to online scaffolding for obtaining more meaningful learning outcomes in argumentation skills development within teacher education programs. Educators can integrate this online scaffolding design into post-class assignments on online learning platforms within existing teacher training courses. Another way can be following this scaffolding design within in class exercises. Finally, evidence from this study strengthens the idea that online scaffolding designers should consider empowering students with greater responsibility in their interactions with the scaffolding to offer a more individualized learning experience that accommodates the diverse needs of students.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Edward Longford for his valuable contributions in proof reading of our paper. The first author acknowledges the PhD funding to pursue her degree in the United Kingdom provided by Ministry of National Education of Turkish Republic. Finally, I dedicate this paper to the 100th anniversary of Republic of Türkiye which provided women with basic fundamental rights and allowed me to pursue higher education.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Beyza Ucar-Longford

Beyza Ucar-Longford is currently a PhD student at Surrey Institute of Education. She holds her bachelors’ degree and master degree from Hacettepe University in Computer Education and Instructional Technology. Her research interests lie understanding and examining the use of technology to support the development of thinking skills such as argumentation in teacher education context.

Dr Anesa Hosein is an Associate Professor in Higher Education at the Surrey Institute of Education. Her research centers around the pathways of young people and academics into, within and out of higher education particularly those with marginalized identities and in STEM disciplines.

Anesa Hosein

Marion Heron is Associate Professor in Educational Linguistics at the University of Surrey. She researches and publishes in the areas of classroom discourse and classroom interaction, genre, educational dialogue, and academic speaking.

Notes

1 Ethical approval obtained with reference number of CENT 20-21 006 EGA.

2 ‘Hocam’ is a Turkish word that is used to refer to a more qualified person, a teacher, a religious authority in a mosque or sometimes a new acquaintance at school or work. We wrote it in Turkish because as far as we know there is no available direct translation for ‘Hocam’ in English.

3 YÖKSİS is the database where Turkish theses are stored.

References

- Andriessen, J. E. B. (2006). Arguing to learn. In R. K. Sawyer (Ed.). The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 443–459). Cambridge University Press.

- Arum, R., & Roksa, J. (2011). Limited learning on college campuses. Society, 48(3), 203–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-011-9417-8

- Asterhan, C. S., & Schwarz, B. B. (2016). Argumentation for learning: Well-trodden paths and unexplored territories. Educational Psychologist, 51(2), 164–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2016.1155458

- Aydeniz, M., & Gürçay, D. (2013). Assessing quality of pre-service physics teachers’ written arguments. Research in Science & Technological Education, 31(3), 269–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/02635143.2013.834883

- Belland, B. R., Gu, J., Armbrust, S., & Cook, B. (2015). Scaffolding argumentation about water quality: A mixed-method study in a rural middle school. Educational Technology Research and Development, 63(3), 325–353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-015-9373-x

- Belland, B. R. (2014). Scaffolding: Definition, current debates, and future directions. In Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology: Fourth Edition (pp. 505–518). Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3185-5_39

- Belland, B. R. (2016). Instructional scaffolding in STEM education: Strategies and efficacy evidence. In Instructional Scaffolding in STEM Education: Strategies and Efficacy Evidence. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02565-0

- Cho, K. L., & Jonassen, D. H., & (2002). The effects of argumentation scaffolds on argumentation and problem solving. Educational Technology Research and Development, 50(3), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02505022

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 297–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613

- Doo, M. Y., Bonk, C., & Heo, H. (2020). A meta-analysis of scaffolding effects in online learning in higher education. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 21(3), 60–80.

- Dorey, F. (2010). In brief: The P value: What is it and what does it tell you? Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research, 468(8), 2297–2298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-010-1402-9

- Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive–developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906–911. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.906

- Garcia-Mila, M., Felton, M., Miralda-Banda, A., & Castells, N. (2023). Pre-service teachers’ knowledge, beliefs and predispositions to teach argumentation in their disciplines. Journal of Education for Teaching, 49(4), 648–666. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2022.2150536

- Glassner, A. (2017). Evaluating arguments in instruction: Theoretical and practical directions. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 24, 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2017.02.013

- Hannafin, M. J., & Land, S. M. (2000). Technology and student-centered learning in higher education: Issues and practices. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 12(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03032712

- Hefter, M. H., Berthold, K., Renkl, A., Riess, W., Schmid, S., & Fries, S. (2014). Effects of a training intervention to foster argumentation skills while processing conflicting scientific positions. Instructional Science, 42(6), 929–947. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11251-014-9320-Y/FIGURES/2

- Hefter, M. H., Renkl, A., Riess, W., Schmid, S., Fries, S., & Berthold, K. (2018). Training interventions to foster skill and will of argumentative thinking. The Journal of Experimental Education, 86(3), 325–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2017.1363689

- Iordanou, K., & Constantinou, C. P. (2014). Developing pre-service teachers’ evidence-based argumentation skills on socio-scientific issues. Learning and Instruction, 34, 42–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2014.07.004

- Iordanou, K. (2022). Supporting strategic and meta-strategic development of argument skill: The role of reflection. Metacognition and Learning, 17(2), 399–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11409-021-09289-1/FIGURES/3

- Jacobs, J. E., & Paris, S. G. (1987). Children’s metacognition about reading: Issues in definition, measurement, and instruction. Educational Psychologist, 22(3–4), 255–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.1987.9653052

- Jeong, A., & Joung, S. (2007). Scaffolding collaborative argumentation in asynchronous discussions with message constraints and message labels. Computers & Education, 48(3), 427–445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2005.02.002

- Jiménez-Aleixandre, M. P. (2007). Designing argumentation learning environments. In S. Erduran & M. P. Jiménez-Aleixandre (Eds.), Argumentation in science education: Perspectives from classroom-based research (pp. 91–115). Springer.

- Jin, Q., & Kim, M. (2021). Supporting elementary students’ scientific argumentation with argument-focused metacognitive scaffolds (AMS). International Journal of Science Education, 43(12), 1984–2006. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2021.1947542

- Jonassen, D. H., & Kim, B. (2010). Arguing to learn and learning to argue: Design justifications and guidelines. Educational Technology Research and Development, 58(4), 439–457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-009-9143-8

- Jose, K. (2016). Digital literacy matters: Increasing workforce productivity through Blended English Language Programs. Higher Learning Research Communications, 6(4), 354. https://doi.org/10.18870/hlrc.v6i4.354

- Khishfe, R. (2022). Nature of science and argumentation instruction in socioscientific and scientific contexts. International Journal of Science Education, 44(4), 647–673. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2022.2050488

- Kim, M. C., & Hannafin, M. J. (2011). Scaffolding problem solving in technology-enhanced learning environments (TELEs): Bridging research and theory with practice. Computers & Education, 56(2), 403–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.08.024

- Kim, N. J., Belland, B. R., & Axelrod, D. (2018). Scaffolding for optimal challenge in K–12 problem-based learning. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 13(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.7771/1541-5015.1712

- Kim, N. J., Vicentini, C. R., & Belland, B. R. (2022). Influence of scaffolding on information literacy and argumentation skills in virtual field trips and problem-based learning for scientific problem solving. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 20(2), 215–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10763-020-10145-Y/TABLES/4

- Kim, S. M., & Hannafin, M. J. (2016). Synergies: Effects of source representation and goal instructions on evidence quality, reasoning, and conceptual integration during argumentation-driven inquiry. Instructional Science, 44(5), 441–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-016-9381-1

- Kuhn, D., & Udell, W. (2007). Coordinating own and other perspectives in argument. Thinking & Reasoning, 13(2), 90–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/13546780600625447

- Kuhn, D., Zillmer, N., Crowell, A., & Zavala, J. (2013). Developing norms of argumentation: Metacognitive, epistemological, and social dimensions of developing argumentive competence. Cognition and Instruction, 31(4), 456–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2013.830618

- Kuhn, D. (2005). Education for thinking. Harward University Press.

- Kuhn, D. (2001). How do people know? Psychological Science, 12(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00302

- Kuhn, D. (1991). The skill of argument. Cambridge University Press.

- Lefstein, A., Vedder-Weiss, D., Tabak, I., & Segal, A. (2018). Learner agency in scaffolding: The case of coaching teacher leadership. International Journal of Educational Research, 90, 209–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2017.11.002

- Lin, H., Hong, Z.R., & Lawrenz, F. (2012). Promoting and scaffolding argumentation through reflective asynchronous discussions. Computers & Education, 59(2), 378–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.01.019

- Lin, Y.-R., Fan, B., & Xie, K. (2020). The influence of a web-based learning environment on low achievers’ science argumentation. Computers & Education, 151, 103860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.103860

- Lu, J., Schmidt, M., Lee, M., & Huang, R. (2022). Usability research in educational technology: A state-of-the-art systematic review. Educational Technology Research and Development, 70(6), 1951–1992. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-022-10152-6

- Luckin, R. (2010). Re-designing learning contexts: Technology-rich, learner-centred ecologies. Routledge.

- Lytzerinou, E., & Iordanou, K. (2020). Teachers’ ability to construct arguments, but not their perceived self-efficacy of teaching, predicts their ability to evaluate arguments. International Journal of Science Education, 42(4), 617–634. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2020.1722864

- Martín-Gámez, C., & Erduran, S. (2018). Understanding argumentation about socio-scientific issues on energy: A quantitative study with primary pre-service teachers in Spain. Research in Science & Technological Education, 36(4), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02635143.2018.1427568

- Miralda-Banda, A., Garcia-Mila, M., & Felton, M. (2019). Concept of evidence and the quality of evidence-based reasoning in elementary students. Topoi, 40(2), 359–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-019-09685-y

- Noroozi, O., & McAlister, S. (2017). Software tools for scaffolding argumentation competence development. In Technical and vocational education and training (Vol. 23, pp. 819–839). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-41713-4_38

- Noroozi, O. (2020). European journal of open education and E-learning studies argumentation-based computer supported collaborative learning (ABCSCL): The role of instructional supports. European Journal of Open Education and E-Learning Studies, 5(2), 3279. https://doi.org/10.46827/ejoe.v5i2.3279

- Oh, E. G., & Kim, H. S. (2016). Understanding cognitive engagement in online discussion: Use of a scaffolded, audio-based argumentation activity understanding cognitive engagement in online discussion. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 17(5), 28. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v17i5.2456

- Oh, S., & Jonassen, D. H. (2007). Scaffolding online argumentation during problem solving. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 23(2), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2006.00206.x

- Osborne, J., Erduran, S., & Simon, S. (2004). Enhancing the quality of argumentation in school science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 41(10), 994–1020. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20035

- Özçinar, H. (2015). Scaffolding computer-mediated discussion to enhance moral reasoning and argumentation quality in pre-service teachers. Journal of Moral Education, 44(2), 232–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2015.1043875

- Öztürk, A. (2017). An investigation of prospective science teachers’ socio-scientific argumentation processes in terms of metacognition: A causal-comparative study. Pegem Eğitim ve Öğretim Dergisi, 7(4), 547–582. https://doi.org/10.14527/pegegog.2017.020

- Plano Clark, V. L., Schumacher, K., West, C., Edrington, J., Dunn, L. B., Harzstark, A., Melisko, M., Rabow, M. W., Swift, P. S., & Miaskowski, C. (2013). Practices for embedding an interpretive qualitative approach within a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 7(3), 219–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689812474372

- Puntambekar, S. (2021). Distributed Scaffolding: Scaffolding students in classroom environments. Educational Psychology Review, 34(1), 451–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09636-3

- Rapanta, C., Garcia-Mila, M., & Gilabert, S. (2013). What is meant by argumentative competence? An integrative review of methods of analysis and assessment in education. Review of Educational Research, 83(4), 483–520. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654313487606

- Rapanta, C., Vrikki, M., & Evagorou, M. (2021). Preparing culturally literate citizens through dialogue and argumentation: Rethinking citizenship education. The Curriculum Journal, 32(3), 475–494. https://doi.org/10.1002/curj.95

- Reynolds, K. A., Triant, J. H., & Reeves, T. D. (2019). Patterns in how pre-service elementary teachers formulate evidence-based claims about student cognition. Journal of Education for Teaching, 45(2), 140–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2018.1548170

- Reznitskaya, A., Kuo, L., Clark, A., Miller, B., Jadallah, M., Anderson, R. C., & Nguyen Jahiel, K. (2009). Collaborative reasoning: A dialogic approach to group discussions. Cambridge Journal of Education, 39(1), 29–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640802701952

- Sadler, T. D. (2017). Promoting discourse and argumentation in science teacher education. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 17(4), 323–346. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10972-006-9025-4

- Sanders, J. A., Wiseman, R. L., & Gass, R. H. (2009). Does teaching argumentation facilitate critical thinking. Communication Reports, 7(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/08934219409367580

- Schnaubert, L., & Vogel, F. (2022). Integrating collaboration scripts, group awareness, and self-regulation in computer-supported collaborative learning. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 17(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11412-022-09367-9/FIGURES/1

- Schraw, G., Crippen, K. J., & Hartley, K. (2006). Promoting self-regulation in science education: Metacognition as part of a broader perspective on learning. Research in Science Education, 36(1–2), 111–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-005-3917-8

- Schraw, G. (1994). The effect of metacognitive knowledge on local and global monitoring. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 19(2), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1994.1013

- Schunk, D. H. (2012). Social cognitive theory. In K. R. Harris, S. Graham, T. Urdan, C. B. McCormick, G. M. Sinatra, & J. Sweller (Eds.), APA educational psychology handbook, Vol. 1. Theories, constructs, and critical issues (pp. 101–123). American Psychological Association.

- Schwarz, B. B. (2009). Argumentation and learning. In N. Muller Mirza & A.-N. Perret-Clermont (Eds.), Argumentation and education: Theoretical foundations and practices. (pp. 91–126). Springer.

- Sharma, P., & Hannafin, M. J. (2007). Scaffolding in technology-enhanced learning environments. Interactive Learning Environments, 15(1), 27–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820600996972

- Sharma, P., & Hannafin, M. (2005). Learner perceptions of scaffolding in supporting critical thinking. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 17(1), 17–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02960225

- Simon, S., Erduran, S., & Osborne, J. (2006). Learning to teach argumentation: Research and development in the science classroom. International Journal of Science Education, 28(2–-3), 235–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690500336957

- Stegmann, K., Wecker, C., Weinberger, A., & Fischer, F. (2012). Collaborative argumentation and cognitive elaboration in a computer-supported collaborative learning environment. Instructional Science, 40(2), 297–323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-011-9174-5

- Suárez, Á., Specht, M., Prinsen, F., Kalz, M., & Ternier, S. (2018). A review of the types of mobile activities in mobile inquiry-based learning. Computers & Education, 118, 38–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.11.004

- Su, G., & Long, T. (2021). Is the text-based cognitive tool more effective than the concept map on improving the pre-service teachers’ argumentation skills. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 41, 100862. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2021.100862

- Tabak, I. (2009). Synergy: A complement to emerging patterns of distributed scaffolding. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(3), 305–335. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls1303_3

- Tawfik, A. A., Law, V., Ge, X., Xing, W., & Kim, K. (2018). The effect of sustained vs. faded scaffolding on students’ argumentation in ill-structured problem solving. Computers in Human Behavior, 87, 436–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.01.035

- Teng, F. (2020). The role of metacognitive knowledge and regulation in mediating university EFL learners’ writing performance. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 14(5), 436–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2019.1615493

- Uçar, B., & Demiraslan Çevik, Y. (2020). The effect of argument mapping supported with peer feedback on pre-service teachers’ argumentation skills. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 37(1), 6–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/21532974.2020.1815107

- Veenman, M. V. J. (2005). The assessment of metacognitive skills. In B. Moschner & C. Artelt (Eds.), Lernstrategien und Metakognition: Implikationenfür Forschung und Praxis (pp. 75–97). Waxmann.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

- Weinberger, A., Stegmann, K., & Fischer, F. (2010). Learning to argue online: Scripted groups surpass individuals (unscripted groups do not). Computers in Human Behavior, 26(4), 506–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.08.007

- Weng, W. Y., Lin, Y. R., & She, H. C. (2017). Scaffolding for argumentation in hypothetical and theoretical biology concepts. International Journal of Science Education, 39(7), 877–897. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2017.1310409

- Wess, R., Priemer, B., & Parchmann, I. (2023). Professional development programs to improve science teachers’ skills in the facilitation of argumentation in science classroom – a systematic review. Disciplinary and Interdisciplinary Science Education Research, 5(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43031-023-00076-3

- Xie, Q., & So, W. W. M. (2012). Understanding and practice of argumentation: A pilot study with Mainland Chinese pre-service teachers in secondary science classrooms. In Asia-Pacific Forum on Science Learning and Teaching, 13(2), 1–20.

- Zhao, G., Zhao, R., Li, X., Duan, Y., & Long, T. (2021). Are preservice science teachers (PSTs) prepared for teaching argumentation? Evidence from a university teacher preparation program in China. Research in Science & Technological Education, 41(1), 170–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/02635143.2021.1872518

- Zheng, X.-L., Huang, J. U. N., Xia, X.-H., Hwang, G.-J., Tu, Y.-F., Huang, Y.-P., & Wang, F. (2023). Effects of online whiteboard-based collaborative argumentation scaffolds on group-level cognitive regulations, written argument skills and regulation patterns. Computers & Education, 207, 104920. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2023.104920

- Zohar, A., & Nemet, F. (2002). Fostering students’ knowledge and argumentation skills through dilemmas in human genetics. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 39(1), 35–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.10008

- Zohar, A. (2007). Science teacher education and professional development in argumentation. In S. Erduran & M. P. Jiménez-Aleixandre (Eds.), Argumentation in science education: Perspectives from classroom-based research (pp. 245–268). Springer Netherlands.

- Zohar, A. (1999). Teachers’ metacognitive knowledge and the instruction of higher order thinking. Teaching and Teacher Education, 15(4), 413–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(98)00063-8

Appendix A

Pretest: Information Technologies and Software Teacher Burak, who has just graduated from the university, has been working in an educational institution affiliated to the Ministry of National Education for five months as responsible for the 5th grade. Burak Teacher’s school has six 5th grade branches, and each branch has a maximum of thirty-three students. At the same time, in this institution; There is also a computer lab for thirty-three people with equipment such as internet, sound system, smart board and printer. Burak Teacher usually teaches his lessons with the lecture method. He also prepares presentations on the topics he will cover and teaches his lesson by reflecting this presentation on the board. Burak Teacher does not use any visual elements while preparing his presentations and generally prepares presentations consisting of detailed texts of at least 30 slides. In addition, Buarak Teacher ends the lesson by asking a few questions to the students about the topics he teaches. However, a group of students consisting of the same people always attend the questions asked by Burak Teacher, while the others are indifferent to the lesson. In his next lesson, Burak Teacher realizes the situations that will be encountered as a result of the violation of ethical principles. will process the gain. Before going to this lesson, Burak Teacher decides to change his teaching method. Accordingly, Burak Teacher realizes the situations that will be encountered as a result of the violation of ethical principles. Which teaching method(s) should he choose to process his learning outcome? Why do you think the teaching method(s) you have chosen is more suitable for handling this outcome? Discuss.

Post-test: Pelin, who is a teacher of Information Technologies and Software, has been working in an educational institution affiliated to the Ministry of National Education as responsible for 6th grades for five years. Pelin Teacher’s school has four 6th grade branches, and each branch has a maximum of thirty-five students. At the same time, in this institution; There is also a computer laboratory for thirty-five people with equipment such as internet, sound system, smart board and printer. Pelin Teacher, in her lessons one week later, "Develops algorithms that include decision structures." Students will encounter this topic for the first time in the Information Technologies and Software course. Therefore, students have very little prior knowledge about the subject. Pelin Teacher usually teaches her lessons with the lecture method. She prepared a presentation on the subject that she will deal with for this lesson as usual, and she taught her lesson by reflecting this presentation on the board. However, these presentations prepared by Pelin Teacher usually consist of dense and detailed texts. In addition, Pelin Teacher ends her lesson by asking a few questions to the students about the topics she teaches. However, a group of students consisting of the same people always attend the questions asked by Pelin Teacher, while the others are indifferent to the lesson. Thereupon, Pelin Teacher decides to change her teaching method before going to her next lesson. Accordingly, Pelin Teacher “Develops algorithms that include decision structures.” Which teaching method(s) should she choose to describe her achievement? Why do you think the teaching method(s) you have chosen is more suitable for handling this outcome? Discuss.

Appendix B.

Interview protocol

Thank you for taking part in this study. The interview session aims to understand your learning experience with online support when learning argumentation skills. As stated in the participant information sheet and consent form, your responses will only serve to understand your learning process and will not carry any identifiable information. The interview should take roughly an hour. You are always free to leave the interview regardless of which process it is. In the interview, I will first share an episode from your engagement with online learning environment, you will be expected to reflect on your learning experience based on this episode and questions prompts.

General questions for all groups

Can you give examples of what you learned on argumentation skills in this training?

How confident do you feel with your argumentation skills in general?

What would be helpful for you to improve … skill more? Why?

How confident do you feel in teaching argumentation skills? Why?

How do you see argumentation skills fitting into your classroom/discipline as a future teacher?

How can you teach or support the development of argumentation skills in classroom? Describe.

If you had to teach argumentation skills, what do you anticipate will be the possible challenges? Why?

This is your learning screen from week 1 and week 2, can you talk about your learning experience when you were using this support to learn argumentation skills? How did you use the supports? How did you learn argumentation skills?

What was the role of argument development task in your learning of argumentation skills?

To what extent did the supports which are how should I construct an argument, how do I prove my causal theory, and is my argument strong in this task assist your learning of argumentation skills? Can you describe your experience with each support in detail?

Do you remember how did you use these supports in the first and second weeks? If the study was longer, how long do you anticipate you would need each of these supports?

Appendix C

Worked example of the rubric with evidence.