ABSTRACT

This article explores the idea that learning can be best understood as a life project. This entails recognition that socio-experiential (being), cognitive (knowing) and behavioural (doing) dimension are crucial, and that the future is of central importance – more than the past – in teaching and learning processes. Based on the concepts of “affinity space” and “activity ecology”, it is also suggested that teaching and learning processes are across settings and time. This proposition is illustrated through two worked examples linked to biographical processes of identity construction in the field of art and the acquisition of English as a foreign language. The article concludes considering the need to recontextualize the school within the perspective outlined here.

Introduction

There are many ways to conceptualize and characterize learning. These “traditions” vary across time, cultures and contexts. One of these theoretical and research lines have considered mostly the behavioural and cognitive processes involved in the processes of content acquisition, and construction of knowledge in formal situations of instruction (Bransford et al., Citation2000).

In fact, most of the theories developed in the twentieth century start from the temporal vector of the past as a critical dimension to define learning. This is the case of behavioural theory according to which behaviour is explained by the accumulation, and impact of its consequences, “contingencies of reinforcement” (Skinner, Citation1954, p. 86). Alternatively, the cognitive-constructivist theory asserts that learning always involves “re-learning”, that is, returning to previous knowledge either to enrich, adjust or modify it (Ausubel, Citation1963; Posner et al., Citation1982).

The thesis we defend in this article is that learning is an unfinished project, occurring throughout the length and breadth of life (Banks et al., Citation2007; Chavez, Citation2021), and committed to biographical processes of identity construction and reconstruction. That is to say, learning is a process of being, knowing and doing in the life course, and ultimately learning is a form of becoming. This affirmation supposes a triple rupture with the aforementioned theories. First, the supremacy of content or the cognitive and behavioural dimension (“knowing” and “doing”) is problematized in favour of a socio-experiential dimension (“being-feeling”). Second, the scenario (ecology) where learning processes – indissoluble with teaching processes – take place is expanded. Third, emphasis is placed on the critical role of the future in teaching-learning processes.

Before discussing this notion, we will present two situations, by way of worked examples, which will allow us to illustrate the perspective outlined here. As it has been considered in other contexts (Gee, Citation2009), we use the notion of worked examples with the intention of making public a certain understanding, in this case about human learning, which should facilitate debate and exchange in an emerging area or conceptualization, rather than as an instructional device designed to model a solution to a problem given by an expert (Atkinson et al., Citation2000).

Art as a way of life, the case of Joan Mateu

Joan Mateu is an artist born in Salt (Girona, Catalonia) in 1976. The story of his life is intimately linked to painting, since he grew up in a family of watercolourists, surrounded by art books, with painting already being a passion as a child. However, his early paintings, and his current works, have little in common. Far from being an innate competence, Joan Mateu says that he learned to paint. The question is, how?

In 1999, he decided to devote himself exclusively to art and, with this objective, he moved to Barcelona to study Applied Arts at La Llotja School of Art and Design. Although initially, influenced by his father and uncle, both watercolourists, he painted watercolours; at La Llotja, he discovered acrylics.

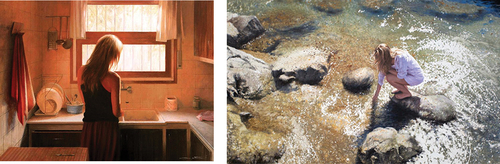

Influenced by painters such as Vermeer or Hooper, he began to receive recognition with intimate works linked to the human figure (see ). In 2002, he held his first solo exhibition, which enjoyed great success, which has accompanied him to this day. Indeed, from this year forward his work has been shown in several exhibitions in Europe and abroad, leading to various awards as well as the publication of his first book, Mateu (RBA/Magrana), in 2007.

Figure 1. Works by Joan Mateu.

When asked, Mateu highlights three things that have allowed him to learn and devote himself to painting, beyond his initial training at La Llotja and the influence of his family environment. First, he acknowledges that 70% of his learning comes from observation and exchange with other artists. Second, his studio is a true laboratory in which he experiments with different techniques and materials. Finally, he cites the exhibitions, books and prizes that are personal challenges through which he draws attention to his work, and obtains feedback.

Like other artists, Joan Mateu is no stranger to social networks and, in this regard, has, in addition to a personal website, a Facebook page, as well as Instagram (@joanmateuart), the social network that the artist uses most to share his works and interact with his followers, as well as with other artists. In all these spaces, the word art appears as the main motive, both for identification (it is combined with his name on his Instagram: “joanmateuart”), and form and content.

illustrates some of these spaces, which we will define later, and which account for the main contexts and activities linked to art in the case of Joan Mateu.

Figure 2. Joan Mateu’s spaces in an affinity space devoted to art.

An ecology for learning English as a second language

Víctor is a doctor born in Valencia (Spain) who has adopted English as the main language of communication in his family environment. With his daughter he speaks only English, although he acknowledges not having learned English at school.

According to him, his interest in the language began when he was 20 years old, during his stay in Italy with an ERASMUS scholarship. There he discovered the importance of English as a language to communicate with people from all over the world. Yet he also felt frustration at not having acquired the necessary level in previous schooling. From that time forward, he would read books and watch television series and films only in English. In addition, he travelled to be able to use the language through different exchanges. Currently, he has incorporated English as the preferred language in his family niche, speaking with his daughter only in English.

Learning as life project(s)

Both examples, briefly described, lead us to suggest that learning is a project of identity construction that translates into the ability to recognize oneself (“self-recognition”), and feel “socially” and/or “institutionally” recognized as an artist, in the first case, or as a fluent speaker of English, in the second. This process, in the form of an identity project, or “life-trajectory” (Dreier, Citation1999), develops throughout a biography, hence the temporary, unfinished nature: it is always possible to learn more things related to both art and language. Moreover, this develops and builds all through life. It is not a simple itinerary; one goes through different scenarios seeking experiences that enhance their interest, motivation and identity passion. In other words, learning is a consequence of “participating in complex structures of social practice and by conducting trajectories in and across diverse social contexts” (Dreier, Citation1999, p. 29) that energies identity making processes.

Correspondingly, this perspective of learning as a life project has three core ideas. First, the link between learning and identity (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991). Second, the distributed nature of teaching and learning processes – notions of ecology activity and learning ecology (Barron, Citation2006). Finally, the projective nature of the learning process that breaks with the notion of the past as fundamental to understanding human learning (behaviourist and cognitive-constructivist theories previously discussed).

Learning as becoming recognized as a certain “kind of person”

The activities that are organized in the different spaces that the person passes through are based on a main identity, for example social activist, video game player, or another type of collective form of intelligence in which certain practices, values, knowledge and rules are shared (Gee, Citation2000). These scenarios allow oneself to be recognized as an artist, for example in the case of Joan Mateu, in addition to acting as such, and acquiring and displaying knowledge and skills linked to this activity-based identity.

These are “affinity spaces” (Gee, Citation2018), where people share and develop a specific interest or passion linked to a shared identity that is materialized through specific values, norms and activities. Ultimately, these spaces (represented in circles and triangles in ), as we understand them here, are socio-cultural scenarios that promote certain ways of knowing, feeling, doing and becoming (or identifying oneself).

Figure 3. Victor’s spaces in an affinity space devoted to English language.

Thus, learning means becoming familiar with these ways of knowing, doing and acting-feeling like a certain type of person (Gee, Citation2000). A way of assuming the guidelines and moral codes of the group (Tomasello, Citation2019), which for Packer and Cole (Citation2019) translates into assuming the rights, responsibilities, duties and obligations associated with a specific institutionalized cultural practice, with both ontological and deontological value. The same person can develop different activity-based identities, or build different funds of identity (Esteban-Guitart, Citation2016), linked to professions, for example medicine, hobbies, video game player, institutions, Catholic religion, geographic spaces, nature lover, or people and friends, as a resource and source of identity construction. Indeed, individuals participate in multiple settings and activities appropriating inevitably a plurality of roles, ways of thinking, feeling and acting (Lahire, Citation2010).

We distinguish, however, three levels of identity recognition. First, a person may feel like and recognize themselves, for instance, as an artist, gardener, activist or animal lover (“subjective-personal recognition” or “self-recognition”). In his Instagram account Joan Mateu incorporates the term “art” as an identitarian mark, and indeed he acknowledges himself as an artist. Second, this experience, at the same time intellectual-symbolic-affective, originates in the framework of interpsychological processes of exchange (Vygotsky, Citation1978) or, what is the same, of “social recognition”, or “interpsychological recognition”: others who identify Joan Mateu, for example, as an artist. Finally, at the institutional level, one can receive a prize, or specific title (diploma that certifies a certain level of English, for example), aimed at publicly recognizing a specific work or activity. This is a third level of recognition, which we call here “institutional recognition”. Our hypothesis is that when these three levels of recognition coincide, learning processes are accentuated and consolidated as a life project.

Activity ecology. Learning as a journey through distributed teaching and learning affinity spaces

Identifying yourself as an artist, or speaker of a foreign language, is a way of acting. That is, a socio-cultural practice that is arbitrary and conventional. These recognition activities are always part of a set of related activities that, in turn, provide them with meaning and significance (Dreier, Citation1999). That is, art, as a form of expression and identity creation, is part of a set of related activities that form an activity ecology: paint pictures, go to exhibitions, watch tutorials or other works through Internet, etc. Learning, as in the example described above, involves participating in all these activities, which constitute, in themselves, a situated and distributed ecology of teaching and learning. Barron (Citation2006) defines a learning ecology as a set of contexts, situations, resources and people, in virtual and physical spaces, which offer learning opportunities. In this sense, learning opportunities transcend, as shown by the two examples presented above, the boundaries of formal institutions of teaching and learning, as well as a specific time in life.

In this regard, in , a network of affinity spaces appear that provide authentic experiences of recognition to the individuals who pass through them driven by an identity interest. These physical and digital spaces (identified in the figures with thick borders) are contexts, in themselves, of learning, in which one can receive recognition, guidance and orientation, while incorporating the norms, values and practices (“a particular way of being”) of the social group.

Among these scenarios there are some that take on particular importance when they become “kitchens” or “laboratories” of identity construction – the studio and Instagram, in the case of Joan Mateu, and the home (family), in the case of the learner of English as a foreign language (indicated in triangles in ). It is in these spaces that there is greater involvement in identity activity, as well as greater circulation of other individuals also involved in these identity-based activities. Joan Mateu’s Instagram and his studio, as well as the home, and the interactions in English that take place there, in the case of Víctor, are opportunities and invitations to other people who share the same interest to share the activity. In other words, these affinity spaces constitute for us the geography of human learning. They are, at once, repositories of experience, resources, artefacts, knowledge, people and skills that allow us to articulate deep learning (Gee & Esteban-Guitart, Citation2019), as they both incorporate and integrate knowledge-know-how, (knowing), abilities (doing) and experiences (being).

Learning as future-oriented

Learning is oriented towards the future in three ways. First, as with psychological systems and processes such as memory (Klein et al., Citation2010), we subordinate previous experience to expectations, desires, and emergent actions that drive us in certain situations. In short, to anticipate, prepare and respond to new demands, actions and decisions. We predict, which would require experimental studies to empirically support this hypothesis, that situations oriented towards the planning of the future can lead to deeper learning processes (increasing, for example, memory capacity), in comparison with other types of situations.

Second, understanding learning as a process of identity construction is to assume the unfinished, dynamic and ideal character linked to conceptions and expectations about who we would like to be. Markus and Nurius (Citation1986) called this “possible selves”. The possible identities are anticipations, desires and expectations about the future. Joan Mateu, in our example, acts to become a good artist, and Victor, to speak, understand and write, more and better English. Again, more than past experiences we could suggest that it is these expectations, desires, projections and anticipations that drive learning processes.

Finally, the origin of a learning situation is a challenge/test that takes the individual beyond their possibilities of current abilities (i.e., zone of proximal development - ZPD). According to Vygotsky (Citation1978), ZPD can be defined as “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem-solving under adult guidance, or in collaboration with more capable peers” (p. 86). Therefore, the term “proximal” refers to those skills that learner is in process of mastering. It is there, when a situation is not satisfactorily resolved, that the need for help (“teaching”) appears, either through a YouTube tutorial, the opinion of an expert, observation of the activity or mentoring by a tutor. These processes are not idiosyncratic to the formal educational context, since in any space of affinity, teaching-learning situations are interwoven, driven by a specific need for identity construction. Learners’ curiosity and desire can activate a zone of proximal development because of their identity purposes. For example, Victor’s aim of being more fluent in English can facilitate his participation in activities where Victor needs the assistance and help of someone to resolve a task. In the case of Joan Mateu, his passion for art can stimulate him to take part in a workshop to learn a new painting technique. In any case, it is the “future”, what we would like to be, that takes us beyond our current state of knowledge and skills.

Conclusion

In this article we have argued that learning can be defined as a life project. An unfinished biographical project oriented towards the personal-subjective, social and institutional recognition of the individual as a certain type of person.

In this regard, school can be considered to be a hub where personal, social and institutional recognition meet. From this we can conclude that it is important to be aware of how learners conceive themselves (“self-recognition”), how they characterize each other (“social recognition”), and how school – as deontic institution (Packer & Cole, Citation2019) – defines them (“institutional recognition”).

The cases of Joan Mateu and Víctor have served us, at the same time, to propose and illustrate the idea of learning as a life project, as a form of being and becoming. In both cases, the protagonists, driven by an identity interest, cycle through different affinity spaces. To put it in other words, they learn to be-become-act like an artist, and a fluent speaker of English, respectively, in an activity ecology as a whole made up of different resources, people and teaching-learning contexts. This is to say, they learn from participation in a distributed system of teaching and learning where artefacts, resources and other people become peers and mentors, as well as real audiences of the activity in question.

This perspective is not unique. Indeed, there are other scholars working with similar or related conceptions of learning in relation to the life course and across contexts. For instance, Bronfenbrenner (Citation1977), Lave and Wenger (Citation1991), Dreier (Citation1999), Barron (Citation2006), or Lahire (Citation2010).

Overall, we believe that these approaches have important implications when it comes to redefining school, as well as the processes of literacy and learning that occur inside and outside of it. Indeed, a large part of significant learning, including school-academic learning, takes place today outside the formal educational context, mediated by digital devices (Erstad et al., Citation2013; Koh & Chen, Citation2021).

The idea of connecting school with the life contexts and experiences of learners is not new (Dewey, Citation1938; Vygotsky, Citation1997), but we estimate that in the current scenarios where teaching and learning processes are ubiquitous, and more distributed than ever before, this becomes even more necessary. The main metaphor we think of here is that of “connection” (Penuel & DiGiacomo, Citation2017).

Schools needs to establish connections and continuities with what goes on outside of them (Bronkhorst & Akkerman, Citation2016), and the identity of the students can be a heuristic resource to facilitate these processes of linking between the curriculum and school practice, and the experiences and significant life contexts of learners. In that regard, schools can be considered as sociocultural niches to bridge learning experiences in and out formal institutions, and contexts-practices to promote artefacts appropriation to imagine future roles, activities and identities (Esteban-Guitart, Citation2016).

This is particularly relevant in secondary education and beyond, when identity becomes a psychological matter from a developmental point of view. Research shows how the cognitive, narrative tools and socio-motivational demands necessary for constructing a life story (autobiographical reasoning and life narrating) develop during adolescence (Habermas & Bluck, Citation2000). However, early childhood education and/or primary education can enrich the precursors of it, such as exploring children’s hobbies and interests, and connecting a curriculum to families’ repertoires of skills, knowledge and expertise. Specifically, by exploring children’s interests and activities at home or through play, school can contribute to the development of autobiographical remembering and the development of the self. This is considered to be a psychological antecedent of the emergence of the life story in adolescence (Habermas & Reese, Citation2015).

Indeed, education can be suggested as being a means to acquiring a particular identity through the practice of that identity. The question here is not to learn science, rather it is to become a scientist. We are not advocating for the abandonment of the curriculum. Precisely, school is a context where different identity trajectories can be showed. It is a particular sociocultural context that guarantees powerful ways of thinking about the world.

Furthermore, the notion of education as a form of expansion of one’s horizons of possibilities must necessarily involve exposure to experiences, not all of which may be pleasant. It may not be obvious to the learner that the “potential barrier” will be worth the subsequent pay-off. Interests are under construction. Being a mathematician, a geographer, or a writer may not appeal to many children initially, but an almost coercive, self-directed approach may eventually bring learners to such a point where a particular activity becomes desirable.

Finally, we believe that it is necessary to incorporate teaching and learning processes that integrate the cognitive (knowing), behavioural (doing) and symbolic-affective (being) dimensions, as well as to recognize, legitimize and enrich the identities of learners, including activity-based identities that have played a marginal role in traditional school, such as video games and fandom culture (Bender & Peppler, Citation2019). Both physical and virtual affinity spaces contribute to learning and identity making process. However, to avoid phenomena such as virtual isolation, when the digital spaces overwhelm the physical spaces, school appears as sociocultural physical context to scaffold identity making, for instance by enriching and/or creating learners’ interests, connecting physical and virtual affinity spaces, or by connecting interests to curriculum.

However, empirical studies are required that, on the one hand, would allow us to contrast and enhance the perspective suggested here, as well as to illustrate the consequences that may arise from it.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Atkinson, R. K., Derry, S. J., Renkl, A., & Wortham, D. (2000). Learning from examples: Instructional principles from the worked examples research. Review of Educational Research, 70(2), 181–214. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543070002181

- Ausubel, D. P. (1963). The psychology of meaningful verbal learning. Grune & Stratton.

- Banks, J., Au, K., Ball, A. F., Bell, P., Gordon, E. W., Gutiérrez, K. D., Heath, S. B., Lee, C. D., Lee, Y., Mahiri, J, Nasir, N. S., Valdés, G., & Zhou, M. (2007). Learning in and out of school in diverse environments: Life-long, life-wide, life-deep. The LIFE Center.

- Barron, B. (2006). Interest and self-sustained learning as catalysts of development: A learning ecology perspective. Human Development, 49(4), 193–224. https://doi.org/10.1159/000094368

- Bender, S., & Peppler, K. (2019). Connected learning ecologies as an emerging opportunity through Cosplay. Comunicar, 58(58), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.3916/C58-2019-03

- Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (2000). How people learn. Brain, mind, experience, and school (Expanded Edition ed.). National Academy Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513–531. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

- Bronkhorst, L. H., & Akkerman, S. F. (2016). At the boundary of school: Continuity and discontinuity in learning across contexts. Educational Research Review, 19, 18–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2016.04.001

- Chavez, J. (2021). Space-time in the study of learning trajectories. Learning: Research and Practice, 7(1), 36–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/23735082.2020.1811884

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience & education. Kappa Delta Pi.

- Dreier, O. (1999). Personal trajectories of participation across contexts of social practice. Outlines: Critical Social Studies, 1(1), 5–32. https://doi.org/10.7146/ocps.v1i1.3841

- Erstad, O., Gilje, O., & Arnseth, H. C. (2013). Learning lives Connected: Digital youth across school and community spaces. Comunicar, 40(40), 89–98. https://doi.org/10.3916/C40-2013-02-09

- Esteban-Guitart, M. (2016). Funds of identity. Connecting meaningful learning experiences in and out of school. Cambridge University Press.

- Gee, J. P. (2000). Identity as an Analytic Lens for Research in Education. Review of Research in Education, 25(1), 99–125. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X025001099

- Gee, J. P. (2009). New Digital Media and learning as an emerging area and “worked examples” as one way forward. The MIT Press.

- Gee, J. P. (2018)Affinity spaces: How young people live and learn online and out of school. Phi Delta Kappan, 99(6), 8–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721718762416

- GeeJ. P., & Esteban-Guitart, M. (2019). Designing for deep learning in the context of digital and social media. Comunicar, 58, 9–18. https://doi.org/10.3916/C58-2019-01

- Habermas, T., & Bluck, S. (2000). Getting a life: The emergence of the life story in adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 126(5), 748–769. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.748

- Habermas, T., & Reese, E. (2015). Getting a life takes time: The development of the life story in adolescence, its precursors and consequences. Human Development, 58(3), 172–201. https://doi.org/10.1159/000437245

- Klein, S. B., Robertson, T. E., & Delton, A. W. (2010). Facing the future: Memory as an evolved system for planning future acts. Memory and Cognition, 38(1), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.3758/MC.38.1.13

- Koh, E., & Chen, O. (2021). The expanding boundaries of learning. Learning: Research and Practice, 7(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/23735082.2021.1885870

- Lahire, B. (2010). The plural actor. Polity Press.

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

- Markus, H., & Nurius, P. (1986). Possible selves. American Psychologist, 14(9), 954–969. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.9.954

- Packer, M. J., & Cole, M. (2019). Evolution and ontogenesis: The deontic niche of human development. Human Development, 62(4), 175–211. https://doi.org/10.1159/000500172

- Penuel, W. R., & DiGiacomo, D. K. (2017). Connected learning. In K. P. En (Ed.), The sage encyclopedia of out-of-school learning (pp. 132–136). SAGE.

- Posner, G. J., Strike, K. A., Hewson, P. W., & Gertzog, W. A. (1982). Accommodation of a scientific conception: Toward a theory of conceptual change. Science Education, 66(2), 211–227. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.3730660207

- Skinner, B. F. (1954). The science of learning and the art of teaching. Harvard Educational Review, 24, 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1037/11324-010

- Tomasello, M. (2019). Becoming human: A theory of ontogeny. Harvard UniversityPress.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Interaction between learning and development. In M. Gauvain & M. Cole (Eds.), Reading son the development of children (pp. 34–40). Scientific American Books.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1997). Educational psychology. St. Lucie Press.