Abstract

Background

Despite the widespread adoption of workplace protections for transgender and gender diverse (TGD) individuals, past research has suggested that microaggressions still occur. Previous literature indicates that microaggressions have a deleterious and cumulative impact on mental health. However, little is known about how microaggressions affect TGD employees over time.

Method

Using a longitudinal design with lagged measures over a period of three months, we explored the current forms of workplace microaggressions against TGD individuals, as well as their prospective impact on emotional exhaustion. We also examined perceived social support, identity centrality, and identity pride as moderators of the effects of microaggressions on emotional exhaustion as these may inform us of potential mitigating factors and targets for interventions.

Results

TGD employees chronically experience various types of microaggressions which, in turn, lead to emotional exhaustion over time. None of the hypothesized factors moderated the time-lagged relationship of microaggressions on emotional exhaustion, but direct effects of perceived social support and identity pride on exhaustion were found.

Conclusion

The findings highlight the urgency to develop strategies that directly reduce microaggressions in organizational settings. In order to provide a safe space for gender minorities in the workplace, we recommend that organizations address microaggressions directly and explicitly within their human resource management policies in an authentic non-tokenistic way. In doing so, organizations should incorporate the experiences of various gender identities and gender expressions, while also defining clear processes for assessment and monitoring, corrective action, and best practice sharing.

Transgender and gender diverse (TGD) employees encounter unique challenges that are not shared with cisgender lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) people, such as transitioning in their place of work (Ozturk & Tatli, Citation2016). These unique challenges and TGD experiences more generally are very rarely considered within policy-making and recruitment practices (Ozturk & Tatli, Citation2016). This lack of representation leads to TGD employees not receiving appropriate support from organizations (e.g. absence of guidance for employers; Phoenix & Ghul, Citation2016). Previous literature on the workplace experiences of TGD employees has shown a high prevalence of stigma at work (e.g. Cancela et al., Citation2024; Scandurra & Bochicchio, Citation2018), and higher unemployment rates compared to LGB (Su et al., Citation2016) and cisgender workers (Leppel, Citation2021). Taking into account that TGD individuals ideate and attempt suicide significantly more than the general public (i.e. 14 and 22 times higher respectively; Adams et al., Citation2017), there is an urgent need to promote inclusion of TGD individuals in organizations.

Workplace challenges for TGD individuals have not gone unnoticed as there is a growing body of human resource development literature that focuses on sharing best practices in the creation of inclusive workplaces for TGD people (e.g. Beauregard et al., Citation2018; Collins et al., Citation2015; Davis, Citation2009; Jones, Citation2013; Kleintop, Citation2019; Sawyer & Thoroughgood, Citation2017; Taranowski, Citation2008; Taylor et al., Citation2011). Additionally, there has been a wide-scale adoption of TGD-inclusive initiatives in large organizations, such that 90% of the Fortune 500 have gender identity protections enumerated in their policies, which is in stark contrast to the 3% in 2002 (Human Rights Campaign Foundation, Citation2023). Advances in TGD inclusion can also be observed at the governmental level, as reflected, for example, in the extension of employment nondiscrimination laws to LGBTQ workers in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by the United States Supreme Court in June of 2020. This trend is also noticeable outside of the United States, as many international regions have also passed TGD-inclusive workplace legislation (e.g. the United Kingdom, the European Union, or some countries in the Asia-Pacific region; Lefebvre & Domene, Citation2023; Sidiropoulou, Citation2019). At this same time, in many places in the world, TGD employees still face a complete lack of nondiscrimination protections (Williamson, Citation2023). Importantly, even when TGD workplace protections are in place, microaggressions still occur in points not clearly outlined in policies (Galupo & Resnick, Citation2016), indicating the importance of paying attention to more nuanced forms of discrimination in the workplace (Cancela et al., Citation2022), and the impact these may have on the well-being of TGD individuals. Building on the minority stress model (Cancela et al., Citation2024; Meyer, Citation2003, Citation2015; Testa et al., Citation2015), this study sets out to understand how microaggressions affect TGD employees over time. Microaggressions gradually build up and deplete individual resources (King et al., Citation2022; Sue et al., Citation2007), and it is therefore relevant to investigate the lagged impact of microaggressions taking place in the workplace. Specifically, in this study we examine the prospective impact of microaggressions toward TGD employees on emotional exhaustion, a key indicator of work strain and the core component of burnout that signals resource depletion. In addition, directly testing central tenets of the minority stress model (Cancela et al., Citation2024; Meyer, Citation2003, Citation2015; Testa et al., Citation2015), we examine the potential of perceived social support, identity centrality, and identity pride to ameliorate the negative impact of microaggressions.

Microaggressions

Microaggressions have been defined as behaviors and statements, often unintentional, that communicate hostile or derogatory messages, particularly in relation to underrepresented minorities (e.g. ethnic, sexual, gender, or religious; Nadal et al., Citation2016; Sue et al., Citation2007). The construct was first introduced by Pierce et al. (Citation1978, p. 66) as “subtle, stunning, often automatic, and non-verbal exchanges which are ‘put downs”. Previous literature on microaggressions specific to the experience of TGD employees is extremely sparse. Fortunately, work by Nadal, Skolnik, and Wong (Citation2012) have identified 12 themes of microaggressions specific to the experiences of TGD individuals across settings. These categories include (a) use of transphobic and/or incorrectly gendered terminology; (b) assumption of universal transgender experience; (c) exoticization; (d) discomfort or disapproval of transgender experience; (e) endorsement of gender-normative and binary culture or behaviors; (f) denial of existence of transphobia; (g) assumption of sexual pathology or abnormality; (h) physical threat or harassment; (i) denial of individual transphobia; (j) denial of bodily privacy; (k) familial microaggressions; and (l) systemic and environmental microaggressions (i.e. within public restrooms, the criminal legal system, health care, and government-issues identification; Nadal et al., Citation2012). Microaggressions experienced by LGB and TGD have been found to occur in various contexts, such as counseling (i.e. LGBTQ sample; Shelton & Delgado-Romero, Citation2013), friendships (i.e. TGD sample; Galupo et al., Citation2014), romantic relationships (i.e. TGD sample; Pulice-Farrow et al., Citation2020), or within the workplace (Dispenza et al., Citation2012; Galupo & Resnick, Citation2016). For LGBTQ employees collectively, Galupo and Resnick (Citation2016) found three main themes of microaggressions in organizational settings. These include (a) hostile, heterosexist and/or cisnormative workplace climate (e.g. coworkers or supervisors misgendering the individual, using derogatory language, or tokenizing their identities); (b) microaggressions within organizational structure of the workplace and power dynamic inherent to the employee’s position (i.e. often experienced within an employee-supervisor or employee-client relationship); and (c) microaggressions related to workplace policy which are more likely to be reflected in the absence of policy (e.g. dress code or bathroom usage rules). Dispenza et al. (Citation2012) further provides examples of microaggressions related to the workplace climate and the organizational structure, such as colleagues denying and debating TGD identities, or supervisors providing unsolicited recommendations on dress code and office attire. Despite these contributions, there is a paucity of comprehensive insights on workplace microaggressions toward TGD employees.

Microaggressions are often dismissed and perceived as innocuous (Sue et al., Citation2007), but research suggests that microaggressions have a deleterious and cumulative impact on mental health. Microaggressions are not only short-lived; rather they build up and accumulate over time (Sue et al., Citation2007). The power of microaggressions rests in their invisibility to the perpetrator and sometimes the recipient (Sue et al., Citation2007). For the perpetrator, microaggressive acts can usually be explained away by seemingly nonbiased and valid reasons. Perpetrators are often unaware of their microaggressive acts and how they are received and interpreted by the recipient, and often recipients’ responses to microaggression are perceived as overreactions (Sue et al., Citation2007). For targets, experiences of microaggressions lead to immediate stress, followed by attributional ambiguity on whether they had misinterpreted the situation and how to respond to it (Nadal, Griffin, et al., Citation2014; Sue et al., Citation2007). In turn, many recipients decide to do nothing. The impact then silently accumulates and resources become depleted (Sue et al., Citation2007). This occurs because recipients of microaggression are often (a) unable to determine whether the microaggression actually occurred, (b) unsure how to respond to the microaggression, (c) concerned about the consequences of confrontation, (d) uncertain whether speaking up would have any positive impact at all, or (e) in denial about the situation (Sue et al., Citation2007). Over time, these rumination processes become more cognitively and emotionally taxing than other types of discrimination (Costa et al., Citation2023). In fact, the chronic uncertainty that comes with microaggressions depletes individuals’ resources (e.g. time, emotions, cognition) as they communicate harmful messages about the target group, and trigger an appraisal of the situation and how to respond (Costa et al., Citation2023; King et al., Citation2022). Nadal, Davidoff, et al. (2014) similarly suggest that targets end up feeling hopeless and exhausted when they experience repeated microaggressions, and tend to believe that the situation would not improve even if they confront perpetrators.

The cumulative stress caused by microaggressions has been found to be associated with negative physical and emotional health outcomes (Costa et al., Citation2023; Williams et al., Citation2021). Mental health consequences include depression, anxiety, anger, frustration, sadness, self-belittlement, hopelessness, distress, and, our focus, emotional exhaustion (Nadal, Davidoff, et al., 2014; Nadal et al., Citation2011; Williams et al., Citation2021). Previous research has also shown that negative well-being outcomes spill over into one’s working life, impacting workplace attitudes and functioning (Costa et al., Citation2023). However, these outcomes have only been studied in wider samples of LGBTQ individuals and have not considered the specific experiences of TGD individuals. It is relevant to analyze the effect of microaggressions on TGD employees’ well-being separately, given that TGD people encounter unique challenges in the workplace (Ozturk & Tatli, Citation2016).

Microaggressions as minority stress and its relation to emotional exhaustion

Microaggressions can be contextualized within the gender minority stress theory (Cancela et al., Citation2024; Meyer, Citation2003, Citation2015; Testa et al., Citation2015). The Minority Stress model (Meyer, Citation2003) describes the processes by which individuals are subjected to minority stress, including external (distal) stress processes (e.g. microaggressions), and internal (proximal) stress processes (e.g. expectations of rejection; Cancela et al., Citation2024). The model was originally developed in the context of sexual orientation (Brooks, Citation1981; Meyer, Citation2003), but it was later expanded to gender minorities (Cancela et al., Citation2024; Testa et al., Citation2015) and workplace settings (Cancela et al., Citation2024; Holman, Citation2018). TGD individuals experience daily stressors associated with their identities in contexts where social stigma is present, which, in turn, have a negative impact on the individual’s mental health and work correlates (e.g. emotional exhaustion; Cancela et al., Citation2024; Meyer, Citation2015; Testa et al., Citation2015). TGD individuals are subjected to similar minority stress as LGB individuals, but also experience stressors specific to TGD people, such as having their gender identity questioned or denied by others (Cancela et al., Citation2024; Testa et al., Citation2015). In addition, LGB and TGD employees experience additional minority stressors in their work life, such as discrimination in the workplace (e.g. microaggressions; Cancela et al., Citation2024).

Microaggressions can be understood as a long-term distal minority stressor that leads to resource depletion and burnout over time (King et al., Citation2022). Within the workplace, burnout is a particularly relevant outcome to consider. Burnout is a prolonged response to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors on the job (Maslach et al., Citation2001). Burnout has been defined by the three dimensions of emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy (Maslach et al., Citation2001). Of these dimensions, exhaustion is the most relevant to consider in regard to the microaggressions literature due to its direct link to resource depletion in targets. Emotional exhaustion is defined as feelings of being emotionally overextended and exhausted by one’s job (Maslach & Jackson, Citation1981). It manifests through both physical (i.e. fatigue) and psychological symptoms (i.e. feeling psychologically and emotionally “drained”). Employees feel fatigued and unable to face the demands of their job or engage with people (Maslach, Citation1998). While past research with TGD employees suggests that discrimination at work is linked to emotional exhaustion (Thoroughgood et al., Citation2017, Citation2021), previous literature specific to microaggressions is limited. Chisholm et al. (Citation2021) suggested that the cumulative impact of microaggressions lead to burnout. More broadly, past literature has found links between other chronic interpersonal workplace stressors, such as workplace bullying, and emotional exhaustion (Anasori et al., Citation2020; García et al., Citation2022; Neto et al., Citation2017). Like microaggressions, workplace bullying consists of repeated and prolonged infringements upon an employee’s personal dignity, which, over time, depletes targets’ resources (García et al., Citation2022). In spite of their comparable chronic nature, there are conceptual differences between microaggressions and workplace bullying, where the aggression is clearly intentional (Neto et al., Citation2017). Microaggressions are not always intentional, thus it is important to look specifically at the impact of microaggressions on emotional exhaustion. In addition, little is known in regard to TGD employees. Past microaggressions research with TGD samples has taken place outside of organizational settings, and has employed either qualitative and cross-sectional designs (Nadal et al., Citation2016), neither of which have provided insights on lagged effects. As such, the ways in which microaggressions experienced by TGD employees’ impacts emotional exhaustion remains poorly understood.

Hypothesis 1: There is time-lagged effect of workplace microaggressions against TGD individuals on emotional exhaustion.

The moderating role of perceived social support

It is also important to understand potential moderators in the relationship between microaggressions and emotional exhaustion as these may indicate what can be done to mitigate the negative effects of microaggressions. The impact of microaggressions on emotional exhaustion will likely depend on both interpersonal and intrapersonal factors. The gender minority stress model (Cancela et al., Citation2024; Meyer, Citation2003, Citation2015; Testa et al., Citation2015) asserts that personal and group resilience resources can ameliorate the impact of minority stress on well-being outcomes. Exhaustion can be further contextualized in terms of job demands-resources theory (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007). In this model, a distinction is made between job demands, which are occupational stressors that are likely to deplete individual resources, and job resources that may reduce these stressors. As such, microaggressions could be understood as job stressors that lead to exhaustion, and the resilience factors may represent social and psychological job resources that buffer the negative impact of microaggressions. Indeed, past research has found that various resources can protect individuals from the impact of minority stressors perpetuated in the workplace, such as microaggressions. At the organizational level, a TGD-inclusive climate through policy making has been found to promote employee mental health and positive job attitudes (Bozani et al., Citation2020; Brewster et al., Citation2014; Cancela et al., Citation2022; Diamond & Alley, Citation2022; Huffman et al., Citation2021; Law et al., Citation2011; Ruggs et al., Citation2015; Tebbe et al., Citation2019). At the interpersonal level, having positive relationships with coworkers (i.e. including supervisors and/or colleagues) has been found to promote well-being (Barclay & Scott, Citation2006; Brewster et al., Citation2014; Cancela et al., Citation2022; Dunlap et al., Citation2021; Huffman et al., Citation2021; Law et al., Citation2011; Ruggs et al., Citation2015; Scandurra & Bochicchio, Citation2018; Thoroughgood et al., Citation2021). Previous qualitative literature has indicated that social support outside of the workplace, such as from family and friends, may buffer the impact of various forms of discrimination in the workplace, including microaggressions (Brewster et al., Citation2014; Dispenza et al., Citation2012). However, most of this preceding work has focused on organizational and coworker resources in ameliorating minority stress, and much less on the impact of support garnered outside of the workplace (Cancela et al., Citation2024).

Social support may help to ameliorate the negative impact of microaggressions encountered in the workplace. The job demands-resources model suggests that social support may buffer the impact of job stressors (e.g. microaggressions) on exhaustion because it provides emotional support for targets (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007). Relatedly, García et al. (Citation2022) suggest that social support from coworkers and supervisors, as well as from family and friends, can protect individuals from chronic interpersonal workplace stressors. Social support has also been found to play an important role in reducing chronic stress at work by minimizing the value of stress events and by promoting adaptive acts (García et al., Citation2022). In fact, support from family and friends can help targets analyze and evaluate stressful situations, and explore ways to solve them. Such support can thus contribute to reducing emotional reactions to chronic workplace stressors and replenishing resources (García et al., Citation2022). Specifically for emotional exhaustion, past research has shown that social support is associated with less emotional exhaustion in people experiencing chronic interpersonal workplace stress (García et al., Citation2022; Malik & Björkqvist, Citation2019). However, it is not yet clear if social support can moderate the relationship between microaggressions and emotional exhaustion in TGD individuals. Previous literature on social support and exhaustion has examined these variables with other samples, but has not considered the workplace microaggressions experienced by TGD individuals.

Hypothesis 2a: The time-lagged positive relationship between workplace microaggressions and emotional exhaustion is moderated by perceived social support, such that the relationship is weaker under conditions of high compared to low perceived social support.

The moderating role of identity centrality

The gender minority stress model (Cancela et al., Citation2024; Meyer, Citation2003, Citation2015; Testa et al., Citation2015) also addresses the role of an individual’s minority identity in the experience of minority stressors such as microaggressions. Characteristics of minority identity include: (a) identity centrality, understood as the prominence of minority identity in the person’s sense of self; (b) identity valence, which entails the evaluative features of identity in terms of self-validation and pride; and (c) integration of the minority identity within the person’s identity. These characteristics can augment or weaken the impact of minority stressors (Meyer, Citation2003). A relevant intrapersonal resource to examine is identity centrality. Identity centrality is a construct that refers to how important a minority identity is to an individual’s sense of self (Hinton et al., Citation2022). The construct also includes identity salience, in which individuals are chronically aware of their identity (Hinton et al., Citation2022). Greater levels of identity centrality have been related to both positive (e.g. self-esteem; Shramko et al., Citation2018) and negative minority stress outcomes (e.g. increased experiences and perceptions of discrimination; Hinton et al., Citation2022).

Identity centrality may play a role the relationship between minority stress in the form of microaggressions and emotional exhaustion as an outcome. In the context of chronic minority stress in the workplace, microaggressions may be more triggering for individuals whose gender identity is prominent in their sense of self, yielding a greater emotional response (Meyer, Citation2003). However, Crane et al. (Citation2018) has suggested that identity centrality can also promote well-being and resilience outcomes by ameliorating the impact of minority stress on targets’ well-being. A potential explanation for this is that identity centrality may remove importance from the microaggressive experience and therefore reduce its impact on exhaustion (Crane et al., Citation2018). Clearly, previous research has found mixed moderating patterns with respect to the role identity centrality may play in the relationship between minority stress and outcomes. Furthermore, the role of identity centrality has not been explored in the context of the depleting outcomes of workplace microaggressions, and rarely in samples of TGD individuals. Thoroughgood et al. (Citation2021) suggested that TGD identity centrality plays a moderating role in the relationship between stress and emotional exhaustion in relation to coworker responses to discriminatory acts toward TGD colleagues. However, the moderating role of identity centrality on the relationship between microaggressions and emotional exhaustions remains uncontemplated and more research is therefore needed.

Hypothesis 2b: The time-lagged positive relationship between workplace microaggressions and emotional exhaustion is moderated by identity centrality, such that the relationship is stronger under conditions of high compared to low identity centrality.

The moderating role of identity pride

Another intrapersonal resource that is relevant to consider in regard to minority stress is identity valence. This construct refers to the evaluative features of identity and is tied to self-validation (Meyer, Citation2003). Positive identity valence or identity pride (Bockting et al., Citation2020) reflects a positive affective reaction to one’s identity, and has been shown to buffer against some minority stressors but not microaggressions specifically (Bockting et al., Citation2020; Cancela et al., Citation2024; Testa et al., Citation2015). In the context of previous research on the impacts of minority stressors, pride in a minority identity has been found to moderate the negative effects of minority stress on mental health (Bockting et al., Citation2013). Additionally, Testa et al. (Citation2015) suggests that identity pride is a source of resilience that may serve to protect TGD individuals from the cumulative depleting impact of microaggressions. More broadly, past research has suggested that LGBTQ identity pride has an ameliorating role on the relationship between minority stress and mental health outcomes (Chang et al., Citation2021). These links are promising, but the role of identity pride has not yet been examined in regard to the workplace experiences of TGD individuals (Cancela et al., Citation2024). Bozani et al. (Citation2020) did, however, connect positive identity valence in terms of self-respect with positive well-being outcomes in TGD employees but the role of TGD identity pride in mitigating the negative impact of chronic workplace stressors remains largely uncontemplated. In addition, emotional exhaustion has not been examined in the context of LGBTQ identity pride. Taken together, past research has shown promising associations between identity pride and minority stress outcomes, but little is known about its role and relation to microaggressions and emotional exhaustion.

Hypothesis 2c: The time-lagged positive relationship between workplace microaggressions and emotional exhaustion is moderated by identity pride, such that the relationship is weaker under conditions of high compared to low identity pride.

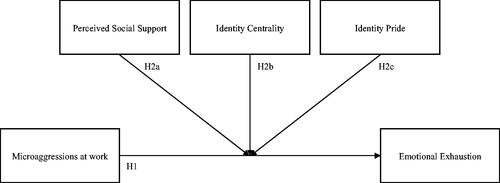

In sum, the goal of the current study is to explore the prospective effect of workplace microaggressions on TGD employees’ emotional exhaustion and to explore possible moderating factors. In doing so, we aim to respond the following research questions: 1) How do microaggressions about TGD individuals in the workplace manifest? 2) How do workplace microaggressions affect emotional exhaustion over time? and 3) What are the potential moderating roles of perceived social support, identity centrality, and identity pride, in the relationship between microaggressions and exhaustion? The conceptual model is depicted in .

Method

Procedure

Between September and December 2022, we advertised a longitudinal survey study on social media, and, given our international focus, we also contacted 45 TGD associations in different continents to recruit TGD participants. To be included in the final sample, participants needed to (a) identify as TGD; (b) be at least 18 years old; (c) be employed for at least six months (either full- or part-time); (d) have coworkers who they regularly interact with; and (e) be able to complete a survey in English. We employed a longitudinal design with three measurement periods one month apart from each other to gather insights on the impact of microaggressions toward TGD employees in the workplace. We chose to collect monthly data for three consecutive months in order to analyze the lagged effect of workplace microaggressions for a quarter of the year on short time lags (Dormann & Griffin, Citation2015), while avoiding participant burden of responding on a weekly basis. This study was part of a larger survey on the workplace experiences of TGD employees. The initial questionnaire had a duration of about 15 min, followed by two subsequent measures of five minutes each. At the end of the third questionnaire, a raffle was run with those participants who completed the study to win a 100 USD/EUR Amazon gift card. To ensure anonymity, we used a questionnaire distribution system that separated the participants’ identifiable information (i.e. e-mail addresses) from the research data files. In this way, we could notify participants via email to complete the follow-up sessions and connect data of individual participants over consecutive waves while keeping the data anonymous. A separate form was used to gather email data of those participants who were eligible and wanted to opt in the raffle.

Once recruited, participants were presented with an information letter explaining the purpose and procedure of the study, and how anonymity would be guaranteed. Thereafter, participants were asked to digitally sign an informed consent form and complete the survey. Ethics approval was provided by the Ethics Review Committee at Maastricht University’s Faculty of Psychology and Neuroscience (188_10_02_2018_S108).

Measures

Details of the focal variable measures included in this study are presented in . Participants completed measures assessing microaggressions at work (Resnick & Galupo, Citation2019), emotional exhaustion (Maslach & Jackson, Citation1981), perceived social support (Zimet, Citation1988), identity centrality (Sellers et al., Citation1997), and identity pride (Testa et al., Citation2015). Microaggressions at work, as well as the moderators, namely identity centrality, identity pride, and perceived social support, were measured only at Time 1 to provide insights on the previous microaggressions experiences and the resources available within the sample. The outcome variable, emotional exhaustion, was measured at Time 2 and Time 3 to allow for testing of lagged effects. Furthermore, a non-mandatory open-ended qualitative question on the experiences of microaggressions was included at Time 2 and Time 3 to provide supplemental insights on the workplace experiences of TGD employees between measurement periods: “During the past month, have you experienced any reactions to your gender identity that made you uncomfortable?”. Additionally, demographic variables such as age, location, ethnicity, gender identity, and employment status were also measured at Time 1.

Table 1. Measures of focal variables.

Participants

In total, 765 responses were recorded at Time 1 (completion rate = 69.9%), 212 at Time 2 (completion rate = 91.5%), and 165 at Time 3 (completion rate = 94.5%). Of the 765 participants at Time 1, 299 were excluded from data analysis as they did not complete the survey (n = 205; 75.0% completion required), identified as cisgender (n = 38), or were not currently engaged in formal paid work (n = 28). 28 participants were further excluded due to significantly shorter response times indicating low data quality due to lack of attention (i.e. those who responded the survey in less than 40% of the median completion time; Greszki et al., Citation2015) leading to a sample of 466 participants at Time 1. Of the 212 participants at Time 2, 30 were excluded due to either low completion rate (n = 18) or significantly shorter response times (n = 12), leading to a sample of 182 participant at Time 2. Of the 165 at Time 3, 22 were excluded due to either low completion rate (n = 8) or significantly shorter response times (n = 14), leading to a sample of 143 participant at Time 3. Furthermore, we took a conservative approach to remove automatic survey-takers (i.e. also known as “bots”; Storozuk et al., Citation2020), aiming to protect the integrity and quality of the sample. In turn, of the remaining 466 participants at Time 1, 100 repetitive and/or inconsistent responses were additionally removed, leading to a final sample of 366 participants at Time 1 (inclusion rate = 47.8%), 161 participants at Time 2 (inclusion rate = 75.9), and 130 participants at Time 3 (inclusion rate = 78.8%). The sociodemographic characteristics of the final sample (N = 366) are presented on .

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample (N = 366).

Analytical approach

We utilized content analysis (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008) to classify the qualitative reports of experienced microaggressions (RQ1) against the themes specific to TGD individuals introduced by Nadal, Skolnik, and Wong (Citation2012). Regarding the quantitative time-lagged analyses, we used Pearson bivariate correlations and linear regression to test the relationship of microaggressions at work and emotional exhaustion (H1). Three separate hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to test the moderation effects of perceived social support (H2a), identity centrality (H2b), and identity pride (H2c); on the relationship between microaggression at work and emotional exhaustion. Based on the recommendations proposed by Frazier et al. (Citation2004), we first standardized scores for both the predictor (microaggressions at work), and moderator variables, namely perceived social support, identity centrality, and identity pride. For each of the moderation hypotheses, we then entered the standardized predictor and moderator into the first step of the regression; and the interaction term (i.e. the product of the predictor and moderator variables) was entered in the second step of the regression. After hypothesis testing, we conducted supplemental analyses to explore the working mechanisms in which microaggressions lead to emotional exhaustion. To do so, we used bootstrapping with 5000 iterations to examine mediation effects (Hayes, Citation2022). All quantitative analyses were conducted in SPSS 29.

Results

Means, standard deviations, and correlations for microaggressions at work, emotional exhaustion, perceived social support, identity centrality, and identity pride are displayed in . The survey responses at Time 1 show that participants experienced relatively low levels of microaggressions (M = 2.11; SD =.77).

Table 3. Means, Standard deviations, and correlations of main variables.

Reports of microaggressions

Across surveys at Time 2 and Time 3, participants were asked to describe the experiences of microaggressions that they had encountered at work since their previous survey response. In total, 59 responses were given. We categorized the responses according to Nadal, Skolnik, and Wong (Citation2012)’s classification of microaggressions specific to the experiences of TGD individuals. The most common theme was the use of transphobic and/or incorrectly gendered terminology (n = 37, 62.71%), including misgendering and the use of incorrect pronouns (n = 29, 49.15%), using transphobic terminology and slurs (n = 5, 8.47%), and deadnaming (n = 3, 5.08%). Hence, misgendering was the most common type of microaggressions participants reported to encounter in the workplace. Participants mentioned that these happened frequently (even after correcting perpetrators), and in most cases unmaliciously, with some participants reporting cases of intentional misgendering (n = 4, 6.78%). A second theme was denial of privacy (n = 10, 16.95%), with participants being asked inappropriate or unnecessary questions about their gender identity or gender expression (n = 4, 6.78%), being stared at (n = 2, 3.39%), gossiped about (n = 2, 3.39%), and being outed without permission (n = 2, 3.39%). Participants also reported encountering environmental level microaggressions (n = 5, 8.47%), including the lack of gender-neutral toilet facilities (n = 3, 5.08%), and barriers to change their information on internal systems (n = 2, 3.39%). The remaining responses included experiencing discomfort/disapproval behaviors from colleagues such as avoiding them in workplace spaces (n = 3, 5.08%), behaviors reflecting adherence to gender binaries such as making jokes about they/them pronouns (n = 2, 3.39%), or assumptions of universal TGD experience such as people not believing their identity or claiming they “do not look trans” (n = 2, 3.39%).

The relationship between microaggressions and emotional exhaustion

Hypothesis 1 predicted a direct time-lagged relationship of workplace microaggressions toward TGD employees with emotional exhaustion. The hypothesized relationships showed the expected trend and were significant at p < .01. Experiences of microaggressions at work at Time 1 were positively correlated with emotional exhaustion both at Time 2 and Time 3, initially supporting Hypothesis 1. The regression analyses indicated a significantly positive direct effect of microaggressions at Time 1 on emotional exhaustion both at Time 2 (β = .28, p = < .01) and Time 3 (β = .29, p = < .01). Hypothesis 1 was thus supported.

Moderation analyses

Multiple regression analyses for hypotheses 2a, 2b, and 2c are summarized in . Hypothesis 2a predicted that the time-lagged relationship between workplace microaggressions toward TGD employees and emotional exhaustion is moderated by perceived social support. High scores on perceived social support would weaken the relationship between microaggressions at Time 1 and emotional exhaustion at Time 2. Conversely, low scores on perceived social support would strengthen the relationship between microaggressions at work and emotional exhaustion. Contrary to expectations, perceived social support did not interact with the time-lagged relationship between the predictor and the outcome variable. There was a direct effect of microaggressions at Time 1 on emotional exhaustion at Time 2 (β = .24, p < .01), but no interaction effects were found between microaggressions and perceived social support at Time 2 (β = .02, p = .81). The moderation analyses also revealed that perceived social support had a direct negative relation to emotional exhaustion at Time 2 (β = −0.26, p < .01), without moderating its relationship with workplace microaggressions. Similar results were found when examining interactions of perceived social support and microaggressions at Time 1 with emotional exhaustion at Time 3 (). Taken together, Hypothesis 2a was not supported.

Table 4. Multiple regression analyses for moderators and microaggressions on emotional exhaustion.

Hypothesis 2b predicted that identity centrality moderates the relationship between microaggressions and exhaustion, whereby high compared to low scores would weaken the relationship. The results showed no interaction effects between identity centrality and microaggressions in relation to emotional exhaustion at Time 2 (β = .02, p = .81). In addition, no direct effects of identity centrality on emotional exhaustion were found at Time 2 (β = −0.04, p = .62). Comparable results were found at Time 3 (). Therefore, Hypothesis 2b was not supported.

Hypothesis 2c predicted that identity pride moderates the relationship between microaggressions and emotional exhaustion, such that high scores on identity pride weaken the relationship of microaggressions and exhaustion. No interaction effects were found at neither Time 2 (β = −0.02, p = .85) nor Time 3 (β = −0.03, p = .74). However, the results showed that identity pride had a direct negative effect on emotional exhaustion at Time 2 (β = −0.21, p < .01), but not at Time 3 (b = −0.12, p = .15). Hypothesis 2c was thus not supported.

Supplemental analyses

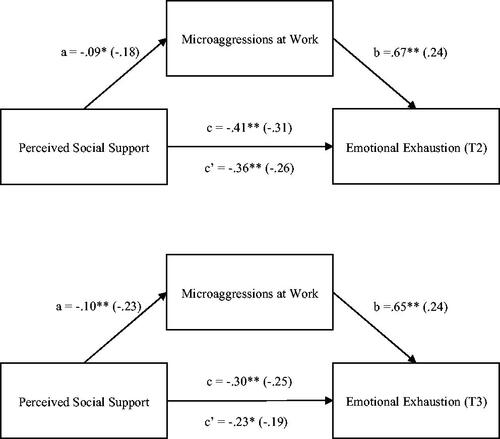

The results did not find support for a moderating effect of perceived social support on the relationship between microaggressions and emotional exhaustion, but there was a direct effect on emotional exhaustion. It could be the case that perceived social support has a different role in the relationship between microaggressions and emotional exhaustion. For example, García et al. (Citation2022) suggested that social support may instead act as an antecedent to the relationship between chronic stress and emotional exhaustion. Support from relatives and friends can help TGD employees by both minimizing the value of the microaggressive acts while also promoting adaptive responses to microaggressions. For this reason, we explored the mediation effect of microaggressions on the lagged negative relationship between perceived social support and emotional exhaustion. To do so, we used bootstrapping to assess the indirect effect of perceived social support through microaggressions. The indirect effects were significant both at Time 2 (β = −0.06, p < .01) and Time 3 (β = −0.07, p < .01). In addition, the direct path from perceived social support and emotional exhaustion remained significant across timepoints (i.e. T1 β = −0.36, p < .01; T2 β = −0.23, p = .03), indicating that microaggressions partially mediated the lagged relationship between perceived social support to emotional exhaustion ().

Figure 2. Mediation diagrams. Note: a, b, c, and c’ are path coefficients representing unstandardized regression weights for the relationships between perceived social support and emotional exhaustion as mediated through microaggressions. The standardized coefficients are in parentheses. The c path coefficient represents the total effect, and the c-prime path coefficient refers to the direct effect. *p < .05, **p < .01.

Discussion

Despite the important strides that have been made to include gender-expansive policies in human resource management (HRM) practices in organizations, workplace microaggressions against TGD employees still occur (Galupo & Resnick, Citation2016). Little is known the current forms of workplace microaggressions toward TGD employees, and how this subtle chronic workplace stressor impacts TGD individuals’ mental health over time (Nadal et al. Citation2016). Most previous research on microaggressions experienced by TGD employees had been conducted outside of organizational settings and it has only employed qualitative and cross-sectional data. This study aimed to fill these theoretical and methodological gaps by using a longitudinal design with lagged measures to study the time-lagged impact of workplace microaggressions against TGD employees on emotional exhaustion, as well as to examine moderating factors, namely perceived social support, identity centrality, and identity pride, that could countervail the impact of microaggressions in organizational settings.

Theoretical implications

This study makes three core contributions to the growing body of literature addressing the workplace experiences of TGD individuals (Cancela et al., Citation2024). First, we offer insights about the types of microaggressions perpetuated in the modern workplace. Despite an overall rise in inclusive workplace policies, our findings show that microaggressions do occur occasionally in workplace settings, such as misgendering, deadnaming, environmental microaggressions (e.g. lack of gender-neutral facilities), or those related to intrusive and disapproving behaviors from colleagues.

Second, we advance knowledge on the working mechanisms by which workplace microaggressions lead to emotional exhaustion over time. Microaggressions, although subtle, have a long-lasting impact on targets that, in turn, lead to emotional exhaustion. The results of our study support, now also with quantitative data, previous qualitative research exploring the impact of microaggressions on TGD individuals’ well-being (Nadal et al., Citation2014).

Third, our findings suggest that certain contextual and individual level factors, namely perceived social support, identity centrality, and identity pride, do not moderate the lagged relationship between microaggressions and emotional exhaustion. Our finding that perceived social support does not moderate the lagged relationship between microaggressions and emotional exhaustion is not in line with the gender minority stress model (Cancela et al., Citation2024; Meyer, Citation2003; Testa et al., Citation2015), which asserts that contextual support (e.g. perceived social support) can protect target individuals by ameliorating the impact of minority stress on mental health. A potential explanation for our findings is that social support from family and friends takes place outside of the workplace, and possibly has limited impact on what happens in the organization compared to work-related sources of support (Halbesleben, Citation2006). Another explanation is that perceived social support does not moderate the relationship between microaggressions and emotional exhaustion but rather acts as an antecedent of the microaggressions-emotional exhaustion relationship. As such, support from relatives and friends may serve to help TGD individuals minimize the value of microaggressions and promote adaptive responses (García et al., Citation2022). Further, while we did not find support for the moderation effect, we found a direct association between perceived social support and less emotional exhaustion, suggesting that support directly alleviates emotional exhaustion. Indeed, previous literature suggests that social support social support is negatively associated with emotional exhaustion, but it does not always function as a buffer in the stressor-strain relationship (Sonnentag & Frese, Citation2013).

Our finding that identity centrality and identity pride do not moderate the relationship between microaggressions and emotional exhaustion is also not consistent with the gender minority stress model (Cancela et al., Citation2024; Meyer, Citation2003; Testa et al., Citation2015), which poses that these characteristics of minority identity can protect individuals against minority stress. Minority stress theory suggests that TGD individuals are exposed to distal (e.g. microaggressions), and proximal (e.g. internalized transphobia) minority stressors, which in turn lead to negative health and work outcomes (Cancela et al., Citation2024). Contrary to expectations, our study found no significant interaction effects of these relationships. It may be the case that these characteristics of minority identity are more effective in countervailing the impact of proximal minority stress rather than distal forms. Nevertheless, identity pride was directly related to less emotion exhaustion. This finding is novel, as previous research has not examined identity pride in relation to emotional exhaustion. A possible explanation is that, in spite of identity pride contributing to more resilience against adversity in general, microaggressions are still impactful.

Taken together, this study thus adds to the literature by 1) providing insight on which microaggressions occur in current organizational settings, 2) offering quantitative evidence on the long-lasting impact of microaggressions on emotional exhaustion over time, 3) discussing the role of contextual and individual level resources on the relationship between microaggressions and emotional exhaustion amongst TGD employees.

Practical implications

In terms of practice, the finding that microaggressions have a long-term impact on TGD individuals’ mental health, and that there are not ameliorated by perceived social support, identity centrality, or identity pride, is highly relevant. Microaggressions are not innocuous, and corporations need to take them seriously in order to promote the well-being of their TGD workforce. At this stage, it is unclear which factors mitigate the impact of microaggressions at work, and this suggest that there is an urgent need to develop effective strategies that directly reduce the prevalence of microaggressions in organizational settings. In that context, our study has shown that microaggressions against TGD employees are more likely to be related to either a hostile, heterosexist and/or cisnormative workplace climate (e.g. misgendering, usage of derogatory language, denial of privacy), or environmental microaggressions deriving from workplace policy (e.g. lack of gender-neutral toilet facilities or barriers to change information on internal systems). As such, addressing these forms of microaggressions should be prioritized.

Practitioners should take these learnings into consideration when designing inclusive policies to foster safety in organizations (Diamond & Alley, Citation2022). Ideally, inclusive policies directly address the needs of TGD employees in terms of providing gender-neutral facilities, standard processes for employees transitioning or changing their documentation internally, and education for employees on how to address TGD employees respectfully (e.g. correct pronoun usage). Policy creation should include formal training for all employees to reduce microaggressions and to encourage reflection on their prevalence in the organization (Bartlett & Bartlett, Citation2011). Academic knowledge on the workplace experiences of TGD employees should be incorporated in training decks and refreshers, such that TGD workplace protections are evidence-based and up-to-date on challenges that TGD individuals face in the organization (Bartlett & Bartlett, Citation2011). Once policies and training are implemented, they ought to be followed by benchmark assessments and consistent monitoring, and, in doing so, advocate for a zero-discrimination culture (Bartlett & Bartlett, Citation2011). Organizations should thus ensure that employees are aware that policies are in place, and have means to enforce these policies (Galupo & Resnick, Citation2016). Concretely, a process for corrective action must be in place when microaggressions occur (e.g. deadnaming).

Furthermore, Fletcher and Marvell (Citation2023) indicated that, in order to be effective in promoting the well-being of TGD employees, it is important that inclusive policies are not perceived as performative or tokenistic. To do so, Fletcher and Marvell recommend promoting authentic allyship in the workplace through the development of formal programmes to: (a) educate employees on the variety of gender identities and expressions of these, and what it means to act as an ally in the workplace; (b) show visible signs of solidarity such as company-wide celebrations (e.g. international transgender day of visibility, international nonbinary people’s day, or transgender day of remembrance); (c) review recruitment, promotion, and talent management practices to not only increase equity of opportunity, but also strengthen justice, fairness, and belonging for TGD individuals (i.e. considering their needs and asks through leveraging listening sessions and focus group discussions); (d) promote psychological safety by enforcing anti-discrimination policies with clear examples of what is unacceptable and the consequences of unacceptable behaviors; and (e) enable authenticity by ensuring all HRM practices (i.e. including dress code, absence, and family policies) include TGD voices in policy creation, consider a range of gender identities and expressions, and they are encouraged by leadership.

Limitations and directions for future research

The findings of this study should be interpreted in the context of some limitations. This study helped to advance understanding on the current forms of workplace microaggressions experienced by TGD employees, as well as on its relationship with emotional exhaustion over time. This study also aimed to offer insights on which factors countervail the detrimental impact of microaggressions on targets. However, the moderation hypotheses were not supported. A potential explanation is that our design only explored moderators at the interpersonal and intrapersonal levels without examining factors specific to the workplace. Future research should address this gap to further unpack the boundary conditions of the impact of workplace microaggressions against TGD individuals on emotional exhaustion. It is possible that work-related support could be more effective in ameliorating the impact of workplace microaggressions, as these are perpetuated in the workplace (Halbesleben, Citation2006). Future research should therefore incorporate a wider spectrum of workplace variables that could be interacting in the relationship between microaggressions and emotional exhaustion. For example, future research could explore perceptions of diversity climate and allyship behaviors at work, which can have a positive impact when perceived as authentic, or a negative impact when perceived as performative or tokenistic (Fletcher & Marvell, Citation2023).

Second, our sample included individuals with different gender identities, geographies, gender expression, or stages of gender socialization. The heterogeneity of the sample may have masked relevant trends. Past research has claimed that it is important to disaggregate data across the various identities present in TGD communities in order to better support their unique needs (Stutterheim et al., Citation2021). For example, it is likely that TGD individuals with different gender identities encounter different microaggressions (e.g. gender diverse individuals may experience microaggressions related to binary expectations), and it is relevant to examine these populations separately in order to further advance literature on the workplace challenges of TGD individuals. This should therefore be taken into consideration when designing future research studies. In addition, in spite of the broad sample recruitment approach, North American and White participants were overrepresented (i.e. 74.3% and 88.0% respectively). Future studies should examine the relationship between microaggressions and emotional exhaustion recruiting broader international samples that include a range of racial and ethnic identities. Black trans people in the United States are directly affected by the intersections of transphobia and racism (Shelton & Lester, Citation2022), and it is possible that the links found in this study could be more severe amongst individuals with overlapping stigmatized identities.

Third, this study employed a conservative approach to data inclusion by removing repetitive and/or inconsistent “bot” responses which are likely to happen when conducting online research (Storozuk et al., Citation2020). In turn, the smaller sample size could have potentially underpowered the results. Future research utilizing online surveys should include strategies to detect and prevent automatic survey-takers’ responses to protect the integrity of the sample. For example, attention check questions could be included to indicate an increased risk of lower data quality (Storozuk et al., Citation2020).

A fourth possible limitation is common method bias (i.e. variance that is attributable to the measurement method rather than the constructs the measures represent) as data collection took place using a single source (i.e. the same longitudinal survey). While this risk may have been ameliorated by using time-separated measures for the dependent and independent variables (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003), future studies should consider obtaining measures of the predictor and criterion variables from separate sources.

In addition to the recommendations for future research that flow from the limitations of this study, we also recommend that future research further examine the role of perceived social support in relation to microaggressions and emotional exhaustion. Previous research suggests that social support may reduce emotional exhaustion by both minimizing the importance of microaggressive acts and repleting individual resources. Future studies should therefore investigate the multifaceted role of social support from various sources to advance knowledge on the relationship between microaggressions and emotional exhaustion. Moreover, future research should further examine the role of identity pride. Our study found a novel link between TGD identity pride and less emotional exhaustion. Whilst identity pride is a source of resilience for gender variant individuals, forthcoming investigation should explore the working mechanisms in which identity pride protects individuals against emotional exhaustion. Lastly, we recommend future research to also include experimental and intervention methodologies, in order to identify mechanisms to reduce microaggressions and successfully educate organizations.

Conclusion

Microaggressions are still present in the workplace, and they occur in various forms, including misgendering, deadnaming, or environmental microaggressions. Workplace microaggressions have a long-lasting negative impact on TGD employees’ emotional exhaustion. Over time, the chronic experiences of microaggressions lead to emotional exhaustion in targets. While contextual and individual resources benefit TGD individuals, they do not seem to exert their influence as a buffer but rather directly alleviate emotional exhaustion. This suggests that we need to address microaggressions directly. Microaggressions should be directly addressed in HRM policies in an authentic, gender-expansive and non-tokenistic manner. Inclusive policy should be guided by the lived experiences of various gender identities and gender expressions, and provide clear processes for corrective action and best-practice sharing. Organizations should also actively listen to their TGD workforce and measure the prevalence of microaggressions at work through continuous monitoring.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, N., Hitomi, M., & Moody, C. (2017). Varied reports of adult transgender suicidality: Synthesizing and describing the peer-reviewed and gray literature. Transgender Health, 2(1), 60–75. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2016.0036

- Anasori, E., Bayighomog, S. W., & Tanova, C. (2020). Workplace bullying, psychological distress, resilience, mindfulness, and emotional exhaustion. Service Industries Journal, 40(1–2), 65–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2019.1589456

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

- Barclay, J. M., & Scott, L. J. (2006). Transsexuals and workplace diversity: A case of “change” management. Personnel Review, 35(4), 487–502. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480610670625

- Bartlett, J. E., & Bartlett, M. E. (2011). Workplace bullying: An integrative literature review. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 13(1), 69–84. In (Issue https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422311410651

- Beauregard, T. A., Arevshatian, L., Booth, J. E., & Whittle, S. (2018). Listen carefully: Transgender voices in the workplace. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(5), 857–884. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1234503

- Bockting, W. O., Miner, M. H., Swinburne Romine, R. E., Dolezal, C., Robinson, B. B. E., Rosser, B. R. S., & Coleman, E. (2020). The Transgender Identity Survey: A Measure of Internalized Transphobia. LGBT Health, 7(1), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2018.0265

- Bockting, W. O., Miner, M. H., Swinburne Romine, R. E., Hamilton, A., & Coleman, E. (2013). Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 943–951. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301241

- Bozani, V., Drydakis, N., Sidiropoulou, K., Harvey, B., & Paraskevopoulou, A. (2020). Workplace positive actions, trans people’s self-esteem and human resources’ evaluations. International Journal of Manpower, 41(6), 809–831. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-03-2019-0153

- Brewster, M. E., Mennicke, A., Velez, B. L., & Tebbe, E. (2014). Voices From Beyond: A Thematic Content Analysis of Transgender Employees’ Workplace Experiences. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(2), 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000030

- Brooks, V. R. (1981). Minority Stress and Lesbian Women. Lexington Books.

- Cancela, D., Hulsheger, U. R., & Stutterheim, S. E. (2022). The role of support for transgender and nonbinary employees: Perceived co-worker and organizational support’s associations with job attitudes and work behavior. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 9(1), 49–57. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000453

- Cancela, D., Stutterheim, S. E., & Uitdewilligen, S. (2024). The Workplace Experiences of Transgender and Gender Diverse Employees: A Systematic Literature Review Using the Minority Stress Model. Journal of Homosexuality. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2024.2304053

- Chang, C. J., Feinstein, B. A., Meanley, S., Flores, D. D., & Watson, R. J. (2021). The Role of LGBTQ Identity Pride in the Associations among Discrimination, Social Support, and Depression in a Sample of LGBTQ Adolescents. Annals of LGBTQ Public and Population Health, 2(3), 203–219. https://doi.org/10.1891/LGBTQ-2021-0020

- Chisholm, L. P., Jackson, K. R., Davidson, H. A., Churchwell, A. L., Fleming, A. E., & Drolet, B. C. (2021). Evaluation of Racial Microaggressions Experienced During Medical School Training and the Effect on Medical Student Education and Burnout: A Validation Study. Journal of the National Medical Association, 113(3), 310–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnma.2020.11.009

- Collins, J. C., McFadden, C., Rocco, T. S., & Mathis, M. K. (2015). The Problem of Transgender Marginalization and Exclusion: Critical Actions for Human Resource Development. Human Resource Development Review, 14(2), 205–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484315581755

- Costa, P. L., McDuffie, J. W., Brown, S. E. V., He, Y., Ikner, B. N., Sabat, I. E., & Miner, K. N. (2023). Microaggressions: Mega problems or micro issues? A meta-analysis. Journal of Community Psychology, 51(1), 137–153. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22885

- Crane, M. F., Louis, W. R., Phillips, J. K., Amiot, C. E., & Steffens, N. K. (2018). Identity centrality moderates the relationship between acceptance of group-based stressors and well-being. European Journal of Social Psychology, 48(6), 866–882. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2367

- Davis, D. (2009). Transgender issues in the workplace: HRD’s newest challenge/opportunity. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 11(1), 109–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422308329189

- Diamond, L. M., & Alley, J. (2022). Rethinking minority stress: A social safety perspective on the health effects of stigma in sexually-diverse and gender-diverse populations. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 138, 104720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104720

- Dispenza, F., Watson, L. B., Chung, Y. B., & Brack, G. (2012). Experience of Career-Related Discrimination for Female-to-Male Transgender Persons: A Qualitative Study. The Career Development Quarterly, 60(1), 65–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2012.00006.x

- Dormann, C., & Griffin, M. A. (2015). Optimal time lags in panel studies. Psychological Methods, 20(4), 489–505. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000041

- Dunlap, S. L., Holloway, I. W., Pickering, C. E., Tzen, M., Goldbach, J. T., & Castro, C. A. (2021). Support for Transgender Military Service from Active Duty United States Military Personnel. Sexuality Research & Social Policy: Journal of NSRC: SR & SP, 18(1), 137–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-020-00437-x

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Fletcher, L., & Marvell, R. (2023). Furthering transgender inclusion in the workplace: Advancing a new model of allyship intentions and perceptions. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 34(9), 1726–1756. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2021.2023895

- Frazier, P. A., Tix, A. P., & Barron, K. E. (2004). Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51(1), 115–134. In(Issue https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.51.1.115

- Galupo, M. P., Henise, S. B., & Davis, K. S. (2014). Transgender Microaggressions in the context of friendship: Patterns of experience across friends’ sexual orientation and gender identity. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(4), 461–470. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000075

- Galupo, M. P., & Resnick, C. A. (2016). Experiences of LGBT microaggressions in the workplace: Implications for policy. In Sexual Orientation and Transgender Issues in Organizations: Global Perspectives on LGBT Workforce Diversity (pp. 271–287). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-29623-4_16

- García, G. M., Desrumaux, P., Ayala Calvo, J. C., & Naouële, B. (2022). The impact of social support on emotional exhaustion and workplace bullying in social workers. European Journal of Social Work, 25(5), 752–765. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2021.1934417

- Greszki, R., Meyer, M., & Schoen, H. (2015). Exploring the Effects of Removing “Too Fast” Responses and Respondents from Web Survey. Public Opinion Quarterly, 79(2), 471–503. https://doi.org/10.1093/noo/nfil058

- Halbesleben, J. R. B. (2006). Sources of social support and burnout: A meta-analytic test of the conservation of resources model. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(5), 1134–1145. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.1134

- Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Hinton, J. D. X., de la Piedad Garcia, X., Kaufmann, L. M., Koc, Y., & Anderson, J. R. (2022). A Systematic and Meta-Analytic Review of Identity Centrality among LGBTQ Groups: An Assessment of Psychosocial Correlates. Journal of Sex Research, 59(5), 568–586. In(Issue Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2021.1967849

- Holman, E. G. (2018). Theoretical extensions of minority stress theory for sexual minority individuals in the workplace: a cross-contextual understanding of minority stress processes. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 10(1), 165–180. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12246

- Huffman, A. H., Mills, M. J., Howes, S. S., & Albritton, M. D. (2021). Workplace support and affirming behaviors: Moving toward a transgender, gender diverse, and non-binary friendly workplace. International Journal of Transgender Health, 22(3), 225–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2020.1861575

- Human Rights Campaign Foundation (2023). Corporate Equality Index 2023-2024. https://www.hrc.org/resources/corporate-equality-index

- Jones, J. (2013). Trans dressing in the workplace. Equality, Diversity & Inclusion, 32(5), 503–514. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-02-2013-0007

- King, D. D., Fattoracci, E. S. M., Hollingsworth, D. W., Stahr, E., & Nelson, M. (2022). When Thriving Requires Effortful Surviving: Delineating Manifestations and Resource Expenditure Outcomes of Microaggressions for Black Employees. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 108(2), 183–207. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0001016

- Kleintop, L. A. (2019). When transgender employees come out: perceived support and cultural change in the transition process. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2019(1), 15868. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2019.15868abstract

- Law, C. L., Martinez, L. R., Ruggs, E. N., Hebl, M. R., & Akers, E. (2011). Trans-parency in the workplace: How the experiences of transsexual employees can be improved. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(3), 710–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.03.018

- Lefebvre, D. C., & Domene, J. F. (2023). Workplace Experiences of Transgender Individuals: A Scoping Review. Asia Pacific Career Development Journal, 6(1), 40–67. http://AsiaPacificCDA.org/Resources/APCDJ/A0006_1_04.pdf

- Leppel, K. (2021). Transgender Men and Women in 2015: Employed, Unemployed, or Not in the Labor Force. Journal of Homosexuality, 68(2), 203–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2019.1648081

- Malik, N. A., & Björkqvist, K. (2019). Workplace bullying and occupational stress among university teachers: Mediating and moderating factors. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 15(2), 240–259. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v15i2.1611

- Maslach, C. (1998). A Multidimensional Theory of Burnout. In C. Cooper (Ed.), Theories of Organizational Stress (pp. 68–85). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198522799.003.0004

- Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behavior, 2, 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020205

- Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397–422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: Conceptual Issues and Research Evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Meyer, I. H. (2015). Resilience in the Study of Minority Stress and Health of Sexual and Gender Minorities. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(3), 209–213. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000132

- Nadal, K. L., Davidoff, K. C., Davis, L. S., & Wong, Y. (2014). Emotional, behavioral, and cognitive reactions to microaggressions: transgender perspectives. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(1), 72–81. In(Issue American Psychological Association Inc. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000011

- Nadal, K. L., Griffin, K. E., Wong, Y., Hamit, S., & Rasmus, M. (2014). The impact of racial microaggressions on mental health: Counseling implications for clients of color. Journal of Counseling and Development, 92(1), 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00130.x

- Nadal, K. L., Issa, M. A., Leon, J., Meterko, V., Wideman, M., & Wong, Y. (2011). Sexual orientation microaggressions: “Death by a thousand cuts” for lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of LGBT Youth, 8(3), 234–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2011.584204

- Nadal, K. L., Skolnik, A., & Wong, Y. (2012). Interpersonal and systemic microaggressions toward transgender people: Implications for counseling. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 6(1), 55–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2012.648583

- Nadal, K. L., Whitman, C. N., Davis, L. S., Erazo, T., & Davidoff, K. C. (2016). Microaggressions toward lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and genderqueer people: a review of the literature. Journal of Sex Research, 53(4-5), 488–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1142495

- Neto, M., Ferreira, A. I., Martinez, L. F., & Ferreira, P. C. (2017). Workplace Bullying and Presenteeism:The Path Through Emotional Exhaustion and Psychological Wellbeing. Annals of Work Exposures and Health, 61(5), 528–538. https://doi.org/10.1093/ANNWEH/WXX022

- Ozturk, M. B., & Tatli, A. (2016). Gender identity inclusion in the workplace: Broadening diversity management research and practice through the case of transgender employees in the UK. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(8), 781–802. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1042902

- Phoenix, N., & Ghul, R. (2016). Gender transition in the workplace: An occupational therapy perspective. Work (Reading, Mass.), 55(1), 197–205. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-162386

- Pierce, C., Carew, J., Pierce-Gonzalez, D., & Willis, D. (1978). An experiment in racism: TV commercials. In C. Pierce (Ed.), Television and education (pp. 62–88). Sage.

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Pulice-Farrow, L., McNary, S. B., & Galupo, M. P. (2020). Bigender is just a Tumblr thing”: microaggressions in the romantic relationships of gender non-conforming and agender transgender individuals. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 35(3), 362–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2018.1533245

- Resnick, C. A., & Galupo, M. P. (2019). Assessing experiences with LGBT microaggressions in the workplace: development and validation of the microaggression experiences at work scale. Journal of Homosexuality, 66(10), 1380–1403. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1542207

- Ruggs, E. N., Hebl, M. R., Martinez, L. R., & Law, C. L. (2015). Workplace “trans”-actions: How organizations, coworkers, and individual openness influence perceived gender identity discrimination. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(4), 404–412. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000112

- Sawyer, K., & Thoroughgood, C. (2017). Gender non-conformity and the modern workplace: New frontiers in understanding and promoting gender identity expression at work. Organizational Dynamics, 46(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2017.01.001

- Scandurra, C., & Bochicchio, V. (2018). Transition in the Workplace: The Experience of Italian Transgender and Gender Non-conforming People through the Lens of the Minority Stress Theory. PuntOorg International Journal, https://doi.org/10.19245/25.05.pij.3.1/2.02

- Sellers, R. M., Rowley, S. A. J., Chavous, T. M., Shelton, J. N., Smith, M. A., Stephanie, V., & Rowley, A. J. (1997). Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity: A Preliminary Investigation of Reliability and Construct Validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.4.805

- Shelton, K., & Delgado-Romero, E. A. (2013). Sexual orientation microaggressions: The experience of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer clients in psychotherapy. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(S), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1037/2329-0382.1.S.59

- Shelton, S. A., & Lester, A. O. S. (2022). A narrative exploration of the importance of intersectionality in a Black trans woman’s mental health experiences. International Journal of Transgender Health, 23(1-2), 108–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2020.1838393

- Shramko, M., Toomey, R. B., & Anhalt, K. (2018). Profiles of minority stressors and identity centrality among sexual minority latinx youth. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 88(4), 471–482. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000298

- Sidiropoulou, K. (2019). Gender Identity Minorities and workplace legislation in Europe. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/204493

- Sonnentag, S., & Frese, M. (2013). Stress in Organizations. In N. W. Schmitt, S. Highhouse, & I. B. Weiner (Eds.), Handbook of psychology: Industrial and Organizational Psychology (2nd Ed., pp. 560–592). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471264385.wei1218

- Storozuk, A., Ashley, M., Delage, V., & Maloney, E. A. (2020). Got bots? practical recommendations to protect online survey data from bot attacks. The Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 16(5), 472–481. https://doi.org/10.20982/tqmp.16.5.p472

- Stutterheim, S. E., Van Dijk, M., Wang, H., & Jonas, K. J. (2021). The worldwide burden of HIV in transgender individuals: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, 16(12), e0260063. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260063

- Su, D., Irwin, J. A., Fisher, C., Ramos, A., Kelley, M., Mendoza, D. A. R., & Coleman, J. D. (2016). Mental health disparities within the LGBT population: A comparison between transgender and nontransgender individuals. Transgender Health, 1(1), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2015.0001

- Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. The American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271

- Taranowski, C. J. (2008). Transsexual employees in the workplace. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 23(4), 467–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/15555240802540186

- Taylor, S., Burke, L. A., Wheatley, K., & Sompayrac, J. (2011). Effectively facilitating gender transition in the workplace. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 23(2), 101–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10672-010-9164-9

- Tebbe, E. A., Allan, B. A., & Bell, H. L. (2019). Work and well-being in TGNC adults: The moderating effect of workplace protections. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 66(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000308

- Testa, R. J., Habarth, J., Peta, J., Balsam, K., & Bockting, W. (2015). Development of the gender minority stress and resilience measure. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(1), 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000081

- Thoroughgood, C. N., Sawyer, K. B., & Webster, J. R. (2017). What lies beneath: How paranoid cognition explains the relations between transgender employees’ perceptions of discrimination at work and their job attitudes and wellbeing. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 103, 99–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.07.009

- Thoroughgood, C. N., Sawyer, K. B., & Webster, J. R. (2021). Because you’re worth the risks: acts of oppositional courage as symbolic messages of relational value to transgender employees. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(3), 399–421. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000515

- Williams, M. T., Skinta, M. D., & Martin-Willett, R. (2021). After pierce and sue: A revised racial microaggressions taxonomy. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 16(5), 991–1007. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691621994247

- Williamson, M. (2023). A global analysis of transgender rights: Introducing the Trans Rights Indicator Project (TRIP). Perspective on Politics, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/FXXLTS

- Zimet, G. D. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2