ABSTRACT

In the past three decades, there has been a trend of adopting an economic approach to understanding religious practices in Africa. While studies have generally focused on the growth of Charismatic–Pentecostal churches, little attention has been paid to the trends in the use of secular advertising strategies in the marketing of religion. The aim of this paper is twofold: firstly, it explores the characteristics of religious flyers and stickers as a marketing tool; secondly, it examines the extent to which religious meaning is attached to the aesthetic design of religious flyers and stickers. Drawing on data from religious flyers and stickers supplemented with data from interviews, observations and documentary analysis, this paper underlines the following key layers communicated through religious flyers and stickers: the prophet as the human brand of a prophetic ministry, the perception of a religious flyer or sticker as a devotional object and the circulation of flyers and use of stickers in urban and digital spaces as a prophetic positioning strategy. We suggest that religious flyers and stickers are used as communicative strategies as well as devotional objects, which offer a reference point to further explore the transformation of religious practices, particularly among Charismatic–Pentecostal churches.

Introduction

In the past three decades or so, analysis of religious discourse from an economic point of view has increased, with the concept of secular marketing practices being progressively employed in religious advertising dialogues.Footnote1 This shows that the idea of religious organizations functioning in a marketplace has now become extensively accepted and endorsed across the globe.Footnote2 The notion of religious marketing is neither new nor strange within the hermeneutic circle of religious ideas and practices. For example, BergerFootnote3 conceptualized the co-existing of diverse religions in society as a market situation, in which religious preference is understood in the context of consumer preferences, trends and interest. Following this operational logic, amid religious pluralism, religion is often viewed as an option on a religious shelf that can be purchased.Footnote4 In Africa, Charismatic–Pentecostalism has become a far-reaching phenomenon that has been characterized by peculiar developments including the marketization of the movement.Footnote5 The awe-striking visibility of the Pentecostal movement in Africa has been researched by many scholars.Footnote6 Due to the phenomenal growth of this movement in the continent of Africa, some scholars characterize Pentecostalism as an African phenomenon.Footnote7 As of 2015, Pentecostal believers made up 17.11 per cent of Africa's 1.19 billion population.Footnote8 Charismatic–Pentecostalism is characterized as faith healing, a firm-like structure to bolster the competitive edge of the church and commercialization of religion and religious goods for profit.Footnote9 On the other hand, Charismatic–Pentecostalism lacks a centralized organizational structure and can be identified through a diverse range of churches, groups, doctrines, practices, styles and moralities.Footnote10 Although it is sometimes recognized as a subdivision of Christianity, due to its influence and dominance, often it is also recognized as a mainstream Christianity. The characteristics outlined by Ukah also describe the different kinds of Charismatic–Pentecostal churches. Their formation is sometimes based on a particular nitch, and this is the case of prophetic ministries in Botswana. The emphasis is on prophecy and self-identification as a prophetic ministry.

Botswana is no exception to the kick-off of marketization of religion, which has descended in an interesting fashion. There are three main types of churches in Botswana: Mainline churches, Charismatic–Pentecostal Churches, and African Independent Churches with the most prominent being Charismatic–Pentecostal churches. The Charismatic–Pentecostal churches are further categorized according to the main spiritual product they offer, for instance, Prophetic ministries.Footnote11 Their identification is in offering prophecy, healing and deliverance to their followers. Studies indicate that prophetic ministries are the frontrunners when it comes to the marketization of religion in the country.Footnote12 While studies have generally focused on the growth of Charismatic–Pentecostal churches, little attention has been paid to the trend of the use of secular advertising strategies by prophetic ministries in the marketing of religion and how this has accelerated the development of religious practices in Botswana. This paper explores the trends of religious marketing of Charismatic–Pentecostal churches with a particular interest in prophetic ministries, the characteristics of prophetic ministry flyers and stickers and how these transform religious practices and influence the burgeoning of prophetic ministries in urban and digital spaces of Botswana.

Religious practice and religious advertising

The extensive involvement of Charismatic–Pentecostal churches in new media and audio-visual presence in public areas has given meaning to the public representation of religion that influences the styles of media presentation used by other religions.Footnote13 A study on ‘Roadside Pentecostalism’ revealed that religious advertising of unmonitored functioning churches has escalated to ‘new levels of creativity’.Footnote14 More and more religious institutions borrow from the secular means of advertising; hence, it is becoming a norm to see a billboard, poster, flyer or social media post-marketing religious services, a religious event or a prominent religious figure. Key religious figures such as prophets play a central role in the existence of new Charismatic–Pentecostal churches as generally they are depicted as the face of their churches. Or as suggested by scholars, prophets are both identity makers and markers of new Charismatic–Pentecostal churches in Africa.Footnote15

Vehicle stickers have also been used to advertise and popularize religious beliefs. Analysing the text written in 72 vehicle stickers collected in Lagos and Ota, Chiluwa divided the stickers according to the dimensions of society as revealed by the text in the vehicle stickers.Footnote16 He categorizes the stickers into three discourse domains according to how they are viewed and used by Christians: social vision, individual/group identity and reaffirmation of faith. The social vision domain identifies stickers that convey social inclinations, desired social status and affirmations. Stickers under social vision uncover various ways that Christians construct their social reality based on their religious belief and practices. On the other hand, individual/group identity categorizes stickers that ally with the achieved identity or under-construction identity of a Christian. Believers are said to construct their identity based on their reverence for the supernaturality of God. In the last category, reaffirmation of faith Chiluwa notes that although stickers can be used to reaffirm an individual’s faith, what is mostly attached to these stickers is about the religious institution.Footnote17 These stickers mostly reaffirm the institutional standards or practices and by so doing inspire moral reformation and proselytization of non-Christians and gain traction for the institution’s philosophies. Chiluwa’s study indicates that there is more than meets the eye when it comes to religious advertisement. Hence, this study seeks to unpack the use of flyers as a medium of advertisement in Botswana’s religious landscape.

The key factor of religious marketing of Charismatic–Pentecostal churches is not merely the digital media vehicles they use to advertise their programmes but also the religious marketing strategies they use.Footnote18 This contributes to and reshapes the religious dynamic of these churches and religious practices in general. In re-emphasizing the foregoing, Yip and Ainsworth stated that there are outcomes expected as a result of religious marketing.Footnote19 For example, the use of secular marketing techniques has proven to be sine qua non to the growth of mega-churches and their increased visibility as a brand. Surprisingly, the religious marketing of Charismatic–Pentecostal churches goes beyond restructuring religious practices. ChiluwaFootnote20 suggested that religious marketing in the form of religious stickers can be used as a form of collective identity by congregants and prompts benevolence in some cases.

Literature reveals that Charismatic–Pentecostal movements embracing the use of advertising strategies for social visibility, promotion of the church as a high-end brand and engagement with ‘religious shoppers’ are paradigmatic in the age of religious marketing.Footnote21 It has been duly noted that the phenomenon of religious marketization extends beyond mere restructuring of religious practices. However, the available literature on this subject matter, particularly with respect to the transformation of religious practices within Charismatic Pentecostal churches in Africa, remains rather scanty and bereft of relevant examples.

Methods and materials

This paper explores the trends of religious marketing of Charismatic–Pentecostal churches, the case of prophetic ministries, the characteristics of prophetic ministry flyers and stickers and how these transform religious practices and influence the burgeoning of prophetic ministries in urban and digital spaces of Botswana. The prophetic ministry flyers and stickers used in this paper as data sources were collected in Gaborone city and its surrounding areas, Francistown city and Maun, during the fieldwork of two related projects: ‘Marketisation of Religion in Botswana’ from September 2014 to April 2015 and ‘New Media and Cultural Application of Religion’ from April 2016 to March 2017. In Botswana, religious events and services and prophetic ministries are well-advertised on various public media platforms, such as radio stations, print media and social media outlets. Advertising through flyers and stickers is a common advertising mode with most flyers and stickers found in public places, such as bus stations, shopping centres, hospitals and clinics, educational centres and institutions, open spaces, offices, bars and entertainment centres.Footnote22 This paper focuses on the content of 39 prophetic ministry flyers and 23 prophetic ministry stickers, gathered purposively in urban and digital spaces of Botswana during the research fieldwork of both studies stated above. A thematic analysis is employed to uncover the prophetic advertising discourses and the discursive effects of the prophetic ministry flyers and stickers. In addition, the analysis is also set to unpack how the use of flyers and stickers shapes religious practices of prophetic ministries and reinforces public religious imagination in Botswana. To support our analysis on the use of flyers and stickers among prophetic ministries in Botswana, this paper also draws on data collected through in-depth interviews and semi-structured interviews with six prophets/apostles and 32 key informants selected purposively from several prophetic ministries in Botswana during the study fieldwork.

Results, analysis and discussion

In general, prophetic ministry flyers and stickers in Botswana have the following common characteristics: images and names of religious figures, captivating scriptural messages, individualized invitations, particulars of a religious event and symbols of social media platforms. Rather than explaining the characteristics of the prophetic ministry flyers and stickers, we employ thematic analysis to uncover the perceived discursive effects that religious flyers and stickers are designed for. To facilitate the analysis, we identify the following themes: prophetic ministry stickers as devotional objects; prophets’ imagery on a flyer as a consumable product; personalized religious invitation; and captivating scriptural messages. In addition, the analysis also pays attention to the distinction embedded in the functions attached to prophetic ministry flyers and prophetic ministry stickers in Botswana.

Prophets’ imagery on a flyer as a consumable product

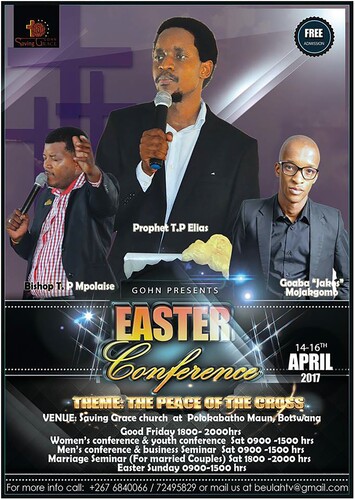

One of the first noticeable traits of a prophetic ministry flyer circulated in Botswana is the image of a prominent religious figure commonly addressed as a prophet or apostle for a male prophetic leader or prophetess for a female prophetic leader. They are also popularly called ‘man of God’ or ‘woman of God’. The names of the religious figures are usually displayed clearly on the flyers preceded by their titles. The title such as prophet, prophetess or pastor presents a two-tier imagery.Footnote23 On the one hand, it informs the public about the spiritual gifts and divine abilities of the man of God to perform prophecy, healing and deliverance. On the other hand, the title shapes the expectation of the believer for a prosperous, transformative and improved life. The importance of this title was expressed by one of the pastors interviewed during the fieldwork for the larger research project that informs this paper: ‘If you don’t call yourself a prophet, no one will come. People do not come when there is nothing. Titles work’. The image of the prophet on the flyer is usually in the form of a professionally taken, well-designed, clean and attractive photograph. In the case of a prophet, the image depicted on the flyer often includes the prophet’s spouse known as pastor or prophetess. The centrality of a prophet figure within the new Pentecostal movements of prophetic ministries has been well studied. In Africa, including Botswana, the so-called prophets are generally young and fashionable and are perceived as powerful religious leaders with divine authority to provide prophecy, deliverance and healing power.Footnote24 The use of an image of a prophet or prophetess on a prophetic ministry flyer is a key point as it cements the common perception of his or her divine power.

The image of prophetic figures found in various flyers is often captured when the prophet holds a microphone talking or making a gesture with a serious face. This visualization mode of a prophetic image is very common. The inclusion of such an image is meant to intensify and accelerate the notion that the religious figure is not only powerful but also knowledgeable. The fashionable prophet is often dressed up in business-like attires sending a common message that this is not business as usual. As such, the serious focused look and business-like attire appear to the audience as someone who is virtuous, upright and able to ‘perform’ miracles as illustrated by , thus solidifying the trust of the audience about the divine call and reputation of the prophet. The image clearly depicts the prosperity idea understood in the context of the ‘prosperity Gospel’. In addition, the appearance becomes an invitation in itself as it evokes feelings of desire to attend the service or join the ministry described in the flyer or sticker. This is to say that the prophet becomes the selling point and the face of the prophetic movement. This idea is not entirely new as it is common within the prophetic and Pentecostal circle. Yip and Ainsworth,Footnote25 for example, call the religious figures ‘human brands’ who enact the identity of the church, marketed through various platforms including that of religious flyers.

Image 1. A prophetic ministry flyer a picture of ‘man of God’ dressed in suits, holding a mic and looking serious. (Collected by G. Faimau).

In the context of religious advertising, like flyers and billboards, Ukah observes that the use of large-sized photos on the billboards presents prophets as celebrities or ‘big men of God’, who ‘sell’ the message and power of the church in order to attract people to the programme or service being advertised.Footnote26 The use of prominent celebrity prophets on flyers, stickers or billboards is a marketing strategy employed by prophetic ministries to promote the visibility of the ministry. The celebrity prophets or ‘Anointed Men of God’ are what we term ‘influencers’ in today’s digital world promoting a ‘brand’ and bringing investment in return for the prophetic ministry being promoted. They also make an attractive subject and focal point for media coverage and marketing communication.Footnote27 The strong and charming persona of the man and woman of God makes for the perfect brand to sell ‘the ministry’ to the rest of the world. This also implies that prophets present themselves as well-polished ‘salespersons’ never compromising the enterprise in any way. Thus, we witness success in the increasing number of adherents, heightened penetration in the media and increased wealth for the prophet and the ministry.

Prophetic ministry stickers as devotional objects

Devotional objects are religious relics like books, pictures, clothes, stickers and votive candles that religious people own, carry and use as votive offerings because they think they have spiritual significance.Footnote28 In Botswana, members of prophetic ministries place the stickers respectfully at their homes. The prophetic ministry stickers are commonly put by the car bumpers, entrance doors, bedroom doors, cupboard doors, mirrors or the back cover of a mobile phone as shown in . Many believe that the stickers from prophetic ministries offer protection when they are placed respectfully in common places at home or in the car and office. The following quotations from two interviewees underline the link between religious stickers and personal protection:

I place the prophet’s sticker on my bedroom door … Whenever I get to my bedroom, I know I am protected. (Female respondent, interviewed in Maun)

I have the sticker because I love this man [the prophet]. He is a man of God. I respect his anointing … What he speaks on this sticker produces results. The main thing is not the sticker itself but the prophet who speaks to you when you look at the sticker. (Male respondent, interviewed in Gaborone)

Just a few months back, I got involved in a car accident. The involved in the accident had been anointed … as I placed a sticker on it … The power of God was there to make sure that indeed what was so formed against me shall not prosper … I was protected in the accident … . (Male respondent, interviewed in Ramotswa)

Personalized religious invitation

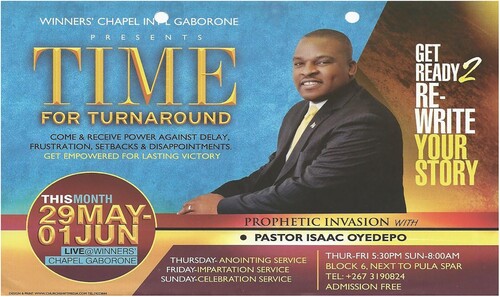

Since the main content of the prophetic ministry flyers is about inviting believers to a religious event such as a prophetic service or a night vigil, the invitation is personalized through the use of appealing catchphrases. , for example, includes the following personalized religious invitation: ‘Get ready 2 rewrite your story’. The use of ‘2’ in place of ‘to’ clearly signifies the appropriation of the common code-mixing in social media language commonly used among young people. By personalizing the invitations, a prophetic effect is created as if the prophet whose image is clearly visible in the flyer speaks directly to the believer with a strong emphasis on the benefit a believer will gain by participating in the event. This can be seen in the following appealing catchphrases highlighted in the flyers collected during the study fieldwork:

Image 3. A prophetic ministry flyer with a personalized invitation and emphasis on the second-person reference (Collected by G. Faimau).

While the personalized invitations are clearly meant to influence membership and increase event attendance, the above catchphrases create a unique audience-centric engagement strategy.Footnote32 Firstly, the statements are presented in the form of a ‘prophet’s command’. Here, the prophet does not only speak directly to the believer; he demonstrates his divine authority on the one hand and underlines his close relationship with his followers on the other hand. The prophetic ministry flyers, therefore, provide a venue for religious advertisement that banks on a close engagement between the prophet as the brand and the believer as the follower and between the believer and his/her faith. Secondly, most of the personalized invitations emphasize the second person ‘you’ and the possessive determiner ‘your’ in the key messages. The use of these words implies that the person reading the message will identify himself or herself as the person being spoken to, thus inducing a need to respond. This is to say that the prophet’s command requires a decision for action. This further implies that failure to accept the invitation means refusing to accept the prophet’s command.

The audience-centric engagement strategy employed by prophetic ministries in their flyers and stickers seems to have borrowed a page from the secular advertisement and marketing handbook. Taglines and catchphrases are common in the world of advertising. It is often argued that taglines are catchphrases utilized by advertisers and branding strategists as a summary of the product being sold.Footnote33 A tagline is meant to create clarity about a product or is used to dramatize the product. In addition, advertising discourse has commonly used second-person references as a promotional strategy to address the audience directly. The use of ‘you’ allows one to reach the masses because everyone reading the advertisement becomes the ‘you’.Footnote34 Among scholars, the use of second-person reference highlights at least three discursive effects. Firtstly, this technique of communicative advertising builds on a participation framework within which the subject (in this case the prophet and his ministry) presents his religious cognitions and intentions towards a believer as the advertising recipient for further action.Footnote35 Secondly, the communicative strategy is designed as a strategic motivation that aims at generating a believer’s religious interest in searching, processing religious information and making a decision for an alliance with the prophet. Thirdly, this strategic communication is intended to create an intimate atmosphere that offers a social space within which the intimate relationship between the prophet and a believer takes place and a believer’s religious involvement and attitude are directed.Footnote36 Therefore, in addition to an audience-centric engagement, in using second-person reference, the prophetic ministry flyers and stickers facilitate a religious participatory framework that allows intimate communication, leading to information processing and personal decision-making by a believer.

It is also worth noting that religious competition is inevitable when an existing religious market is filled up with a significant mushrooming of religious groups and institutions, including new Pentecostal movements or new prophetic ministries. As suggested by Ukah,Footnote37 ‘ … because competition is stiff among Pentecostal churches, they strive to carve a niche that will act as a pull factor to their churches’. Prophet ministries benefit from personalized invitations to a specific audience as the main target. A crafted religious advertising through the use of flyers or stickers is directed towards creating product disparity in order to attract as many people as possible.

Captivating scriptural messages

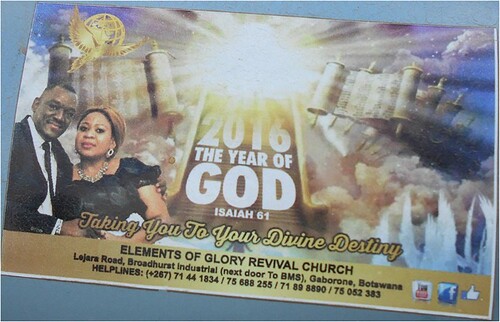

Another common feature of prophetic ministry flyers and stickers selected for this paper is the captivating scriptural messages. In general, the messages are not just any text but scriptural persuasive texts supported by a biblical verse (see ). Among others, the following biblical verses were printed neatly on the selected prophetic ministry flyers and stickers:

Sit at my right hand, till I make your enemies your footstool. (Psalm 110:1) [printed on a flyer]

If ye be willing and obedient, ye shall eat the goods of the land. (Isaiah 1: 19) [printed on a sticker]

Proclaim the acceptable year of the Lord and the day of vengeance of our God. (Isaiah 61:2) [printed on a flyer]

Where there is no vision, people perish. (Proverbs 29:18) [printed on a sticker]

Get rid of the old yeast as you really are, for Christ our passover lamb has been sacrificed. (1 Corinthians 5:7) [printed on a sticker]

I am restored, living a restored life is our mandate. (Jeremiah 1:10) [printed on a flyer]

Image 4. A prophetic ministry sticker with a picture of a prophet and his spouse, a scriptural reference and a personalized invitation (Photograph: G. Faimau).

Scholars of religion and religious advertising have noted that drastic changes in the economy or increased moral decay are times when religious institutions step in to reinforce beliefs or establish new ones.Footnote38 As such, Cazarin suggests that some words or texts used in religious advertising are meant to create impacting emotional imagery on the audience.Footnote39 In this context, the use of a scriptural verse is designed to support discursive themes and reinforce the belief that a higher power beyond the prophet’s authority is in control. This means that although the themes or captivating catchphrases written on the religious flyers and stickers are construed by a prophet and his prophetic ministry, the inclusion of a biblical verse imposes the idea that the higher source, God himself, is the one at work.

Religious flyers and spatial configurations

These ministries follow a particular spatial configuration as they are strategically positioned in places with high movement of people on a daily basis, such as shopping complex, gas stations and villages near the cities. A simple Google search using ‘church’ or ‘ministry’ in Gaborone shows that there are at least 16 prophetic ministries in and around Gaborone city. Among them, the following are some of the most popular prophetic ministries: Be Free Christian Church led by Prophet Keletso Moenda; Gospel of God’s Grace (3G) Ministries led by Prophet Cedric Kobedi; and Healing Faith Ministries in Ramotswa led by Apostle Daniel Ebenezer. BBS mall is one of the oldest and well-known shopping malls in Gaborone city. This mall is currently a host to four prophetic ministries: Christ Embassy, Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, Winner’s Chapel Internationa and Manifest Presence Ministries. The strategic positioning in a marketplace is a new trend in the religious landscape of Botswana. The goal is that as people shop for different commodities, they can also access spiritual goods within the same urban space.

The establishment of prophetic ministries in shopping malls can be attributed to strategic capitalization of the high populace in shopping complexes. In the context of Botswana, shopping malls are built where the population is over 5000 people together with a minimum of 1000 residential plots in a given locality.Footnote40 The number of people who visit shopping malls frequently supports the profit-making efforts of business establishments situated in such complexes. Religious enterprises, particularly the prophetic ministries, also seek to benefit from this window of opportunity offered by malls to attract followers. This phenomenon could be termed ‘shopping mall Pentecostalism’ as it denotes the presence and participation of charismatic Pentecostal movements in the economic activity of a shopping complex to gain adherents. Theoretically, economic analysis of religion supports the notion that religion is a market on its own that facilitates the supply, purchasing and competition for religious commodities.Footnote41 Similar to business ventures, religious institutions seek to maximize consumer satisfaction. A shopping complex, therefore, becomes the prime environment. In addition to positioning themselves in central marketplaces, they have adopted methods of advertisement associated with business marketing. When shops hand out a catalogue of what people can find in their shops at a particular price, agents from these prophetic ministries also distribute various flyers to inform consumers of where they can find prophecy, healing, deliverance, and prosperity. The religious commodities also extend to the tangible ones like anointing oil, holy water and religious stickers. This finding indicates that prophetic ministries are revolutionizing the religious landscape of Botswana to a commercialized religion through the use of business tenets and marketing strategies.

The presence of prophetic ministries in shopping complexes of urban spaces through flyers can be asserted to various contentions. The most relevant being ecclesiastic marketing/religious marketing defined by Juravle, Sasu and Spataru as service marketing.Footnote42 This idea refers to the advertisement of a service for consumption, which can result in profit-making or no profit-making. Although Juravle, Sasu and Spataru want to refrain from terming the intentions of religious marketing to include profit-making, this is inevitable as studies, especially in Africa, indicate that ‘the church’ has now become a marketplace.Footnote43 In the case of prophetic ministries in Botswana, the use of flyers to advertise religious events and other religious goods substantiates the sale of religious commodities, either tangible or non-tangible.

By becoming market agencies, prophetic ministries have sought out secular means to solidify their presence in urban spaces. The approach is embraced as, for many prophetic ministries, it is crucial for swaying public perception about the image of the church.Footnote44 The use of stickers, banners, posters and Internet is said to play an important role in preserving and attracting adherents.Footnote45 ‘Religious organizations have taken on names, logos or personalities, and slogans that allow them to be heard in a cluttered, increasingly competitive marketplace’. Against secularization theory, it is clear that prophetic ministries employ unorthodox and secular methods to attract and reinforce participation in religious activities.

The use of social media and flyers has impacted Pentecostal movements including prophetic ministries. Following the contemporary trends, Pentecostal churches have actively sought and interacted with their (prospective) members through various social media platforms. According to Agarwal and Jones,Footnote46 social media has emerged as a ‘novel sacral space’ where believers gather to seek fulfilment and acknowledgment of their spiritual demands, including healing, prophecy and spiritual upliftment. In addition, AyeniFootnote47 suggests that social media platforms are used to provide spiritual services such as fellowship and virtual dialogues. Consequently, social media platforms serve several purposes, ranging from being a space for ‘online community’ to being transformed as a ‘marketplace’. The proliferation of Pentecostal Charismatic churches on social media platforms has facilitated convenient connectivity for followers and adherents to engage with their church, access a diverse range of religious products and establish connections with other believers. In addition, de WitteFootnote48 presents a compelling case on the impact of social media by contending that Pentecostal churches use social media as a tactic of antagonism against other churches and religions. This is further exemplified by other scholars with a contention that Pentecostal movements used social media as an antagonism and political tactic to fight corruption.Footnote49 In general, however, Pentecostal–charismatic churches use innovative and visually appealing communication methods, such as the distribution of flyers, as a means of disseminating information to its members. This practice is also prevalent in the realm of internet marketing. According to reports, the global user base of social media stands at 5.04 billion individuals.Footnote50 Consequently, a religious flyer has the potential to reach millions of people when disseminated via social media platforms compared to traditional print media. Analysis of religious flyers included in this study shows that most of the flyers display icons of the different social media platforms. Indeed, the presence of prophetic ministries is not only prevalent in urban spaces, but it is highly felt in social media platforms, particularly Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.Footnote51 Facebook search of Prophet Cedric of 3G Ministries in Botswana, for example, indicates that his page categorized as ‘Religious Organization’ has a following of 173,085+ as of 18 September 2021. Prophetic ministries capitalize on publicizing their social media presence on religious flyers and stickers. Inclusion of social media icons on religious flyers and stickers is generally meant to enhance a religious organization’s online network. In doing so, the organizations ensure that current followers are able to read updates about the organization, and potential followers can easily search or look up an organization to find out more about it.Footnote52 Social media platforms are also used to circulate religious flyers that informs followers of events and guest prophets for a scheduled religious event. What we notice with the use religious flyers with social media icons as advertisements is that generally prophetic ministries employ deliberate efforts to be strategic in terms of advertising themselves through flyers and social media platforms.

The online presence of prophetic ministries presents multiple options to religious consumers. PercyFootnote53 asserts that loyalty to one denomination or brand is no longer the case as people, including religious believers, are unwavering when it comes to products. The online presence of prophetic ministries means that one is not confined to only one ministry as they can engage with any other at any given time.

Inclusion of social media icons on a religious flyer or stickers can also be regarded as important pointers. Social media platforms, especially Facebook, Instagram and YouTube of recent, have developed options such as live streaming, which allows one to participate on a religious event online and engage through comments section. The use of social media by prophetic ministries is not only for reaching a diverse population but also for creating what we can term ‘convenient religiosity’. Convenient religiosity simply means that prophetic ministries have accepted and have instead extended their services to a platform that allows followers to participate at a time suitable for them. By including the social media icons, prophetic ministries maintain the traditional attendance of going to church or a religious event on a given time while gradually shifting the focus to a convenient worshipping through social media platforms. The advent of COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the idea of convenient worshipping as many churches including prophetic ministries embrace the digital space as a new norm. In this context, the world’s religious landscape has seen a rise in live-streamed Pentecostal church services across platforms, such as Facebook and YouTube. In their study, Golan and Michele revealed that watching live-streaming is so prevalent to the extent that it is not only confined to private spheres but also extends to public places, such as shops, hospitals and retirement communities, as well as religious venues.Footnote54 Religion, therefore, has formed a symbiosis with the virtual culture as it continues evolving in the digital spaces. By including social media icons in the flyers and stickers, prophetic ministries do not only direct their followers or potential followers to their social media platforms, but they also make a compelling argument that the church does not only exist as a physical building, but it also exists as an online digital reality. The inclusion of the social media icons, therefore, underlines a message that the prophetic ministries exist physically and virtually.

Conclusion

This article explores the trends of religious marketing of Charismatic–Pentecostal churches with a specific focus on prophetic ministries in Botswana, the characteristics of prophetic ministry flyers and stickers and how the circulation of the flyers and use of stickers as devotional objects influence the burgeoning of prophetic ministries in urban and digital spaces of Botswana. Additionally, it explores how the circulation of prophetic ministry flyers reconstructs religious practices and reinforces public religious imagination. The trends of religious advertising that prevail in the texts of prophetic ministry flyers and stickers can be understood in three layers: the prophet as the human brand of a prophetic ministry, the religious perception of a sticker as a devotional object and finally the circulation of flyers and use of stickers in urban and digital spaces as prophetic positioning and a visibility strategy. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that although prophetic ministry flyers and stickers are imbued with spiritual significance, the textual and social media content contained therein highlights a departure from traditional modes of worship towards a more convenient form of religiosity. This emergent religious culture embraces the use of digital spaces as platforms for worship. We, therefore, recommend further studies focusing on religious advertising and digital religious practices in Africa to highlight the nuances in how religious marketing in Africa is transforming traditional religious practices.

Acknowledgements

TR, GF and WK conceptualized this paper, developed the draft, performed formal analysis, and reviewed and edited the article. GF conceptualized the larger project that informs this paper, developed the methodology and verified the data. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tshoganetso Dolly Ramooki

Tshoganetso Dolly Ramooki is an independent researcher residing in Botswana. She graduated from the University of Botswana majoring in Sociology and Public Administration.

Gabriel Faimau

Gabriel Faimau is an Associate Professor of Sociology at the Department of Sociology, University of Botswana, and an Extraordinary Researcher in the Unit for Reformational Theology and the Development of the South African Society at North-West University, South Africa.

Wame Maryjoy Kesebonye

Wame Maryjoy Kesebonye is an independent researcher residing in Botswana. She graduated from the University of Botswana majoring in Sociology and Psychology.

Notes

1 Grad, “Religion, Advertising”; Yip and Ainsworth, “We Aim to Provide Excellent Service”; Percy, “The Church in the Market Place.”

2 Ahdar, “The Idea of Religious Markets”; Iannacone, Finke, and Stark, “Deregulating Religion.”

3 Berger, The Sacred Canopy, 138.

4 Davie, “Prospects for Religion,” 461; Percy, “The Church in the Market Place,” 113–14.

5 Straub, “The Pentecostalization of Global Christianity,” 221–4.

6 Faimau, “The Emergence of Prophetic Ministries”; De Witte, “Pentecostal Forms”; Straub, “The Pentecostalization of Global Christianity”; Ukah, African Christianities, 369–85.

7 Straub, “The Pentecostalization of Global Christianity,” 222.

8 Wariboko, “Pentecostalism in Africa.”

9 Ukah, African Christianities.

10 De Witte, “Pentecostal Forms,” 2.

11 Faimau, “The Emergence of Prophetic Ministries,” 11–14.

12 Ibid.

13 De Witte, “Pentecostal Forms,” 4.

14 Ukah, “Roadside Pentecostalism,” 127.

15 Faimau, “The Emergence of Prophetic Ministries,” 7; Yip and Ainsworth, “We Aim to Provide Excellent Service”; Ukah, “Roadside Pentecostalism.”

16 Chiluwa, “Religious Vehicle Stickers.”

17 Ibid., 381–4.

18 Grad, “Religion, Advertising.”

19 Yip and Ainsworth, “We Aim to Provide Excellent Service.”

20 Chiluwa, “Religious Vehicle Stickers,” 379–81.

21 Grad, “Religion, Advertising,” 149.

22 Faimau, “The Emergence of Prophetic Ministries,” 7–8.

23 Cazarin, “African Pastors,” 469–72.

24 Premawardhana, “Expecting the Unexpected”; Ukah, “Road Pentecostalism,” 131–4.

25 Yip and Ainsworth, “We Aim to Provide Excellent Service.”

26 Ukah, “Roadside Pentecostalism,” 127.

27 Yip and Ainsworth, “We Aim to Provide Excellent Service.”

28 Musoni, Machingura, and Mamvuto, “Religious Artefacts, Practices.”

29 Morehouse and Saffer, “Promoting the Faith,” 410–12.

30 Meyer, “There Is a Spirit.”

31 Meyer, “Picturing the Invisible.”

32 Morehouse and Saffer, “Promoting the Faith,” 416–17; Tilson and Venkateswaran, “Toward a Covenantal Model,” 116.

33 Ray et al., “Creative Tagline Generation.”

34 Cui and Zhao, “The Use of Second-Person,” 26.

35 Packard, Moore, and McFerran, “(I’m) Happy to Help.”

36 Cruz, Leonhardt, and Pezzuti, “Second Person Pronouns”; Torresi, Translating Promotional and Advertising Texts.

37 Ukah, African Christianities, 15.

38 Lindhardt, “Introduction: Presence and Impact.”

39 Cazarin, “African Pastors,” 472.

40 Bagopi and Daman, The Nature and State of Competition, 6.

41 Yip and Ainsworth, “We Aim to Provide Excellent Service.”

42 Juravle, Sasu, and Spataru, “Religious Marketing,” 336–7.

43 Anderson Jnr, “Commercialisation of Religion.”

44 Anyasor, “Advertising Motivations.”

45 Einstein, Marketing Religion.

46 Agarwal and Jones, “Social Media’s Role,” 1–2.

47 Ayeni, “Branding and Marketing,” 104–6.

48 De Witte, “Pentecostal Forms,” 7–10.

49 de Arruda et al., “The Production of Knowledge,” 208.

50 Statista, “Internet and Social Media Users.”

51 Faimau and Lesitaokana, New Media and the Mediatisation; Faimau and Behrens, “Facebooking Religion.”

52 DesignBro, “Social Media.”

53 Percy, “The Church in the Market Place,” 104–6.

54 Golan and Michele, “Religious Live-Streaming,” 437–8.

Bibliography

- Agarwal, Ruchi, and William J. Jones. “Social Media’s Role in the Changing Religious Landscape of Contemporary Bangkok.” Religions 13, no. 5 (2022): 421.

- Ahdar, Rex. “The Idea of ‘Religious Markets’.” International Journal of Law in Context 2, no. 1 (2006): 49–65.

- Anderson Jnr, George. “Commercialisation of Religion in Neo-Prophetic Pentecostal/Charismatic Churches in Ghana: Christian Ethical Analysis of Their Strategies.” Journal of Philosophy, Culture and Religion 42 (2019): 1–8.

- Anyasor, Okwuchukwu M. “Advertising Motivations of Church Advertising in Nigeria.” International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development 5, no. 1 (2018): 99–192.

- Ayeni, Oluwadamilola Blessing. “Branding and Marketing Nigerian Churches on Social Media.” In Marketing Brands in Africa: Perspectives on the Evolution of Branding in an Emerging Market, edited by Samuelson Appau, 99–119. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021.

- Bagopi, Ernest B. L., and Christson Daman. The Nature and State of Competition in the Botswana Shopping Mall Retail. Gaborone: Competition Authority, 2016.

- Berger, Peter L. The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion. New York: Open Road Integrated Media, 1967.

- Cazarin, Rafael. “African Pastors and the Religious (Re) Production of a Visual Culture.” Etnográfica. Revista do Centro em Rede de Investigação em Antropologia 21, no. 3 (2017): 463–477.

- Chiluwa, Innocent. “Religious Vehicle Stickers in Nigeria: A Discourse of Identity, Faith and Social Vision.” Discourse & Communication 2, no. 4 (2008): 371–387.

- Cruz, Ryan E., James M. Leonhardt, and Todd Pezzuti. “Second Person Pronouns Enhance Consumer Involvement and Brand Attitude.” Journal of Interactive Marketing 39 (2017): 104–116.

- Cui, Ying, and Yanli Zhao. “The Use of Second-Person Reference in Advertisement Translation with Reference to Translation Between Chinese and English.” International Journal of Society, Culture & Language 2, no. 1 (2013): 25–36.

- Davie, Grace. “Prospects for Religion in the Modern World.” The Ecumenical Review 52, no. 4 (2000): 455–464.

- de Arruda, Gabriela Alcantara Azevedo Cavalcanti, Daniel Medeiros de Freitas, Carolina Maria Soares Lima, Krzysztof Nawratek, and Bernardo Miranda Pataro. “The Production of Knowledge Through Religious and Social Media Infrastructure: World Making Practices among Brazilian Pentecostals.” Popular Communication 20, no. 3 (2022): 208–221.

- DesignBro. DesignBr. April 27, 2021. Accessed February 12, 2022. https://designbro.com/blog/inspiration/business-cards/social-media-icons-for-business-cards/#:~:text=Putting%20social%20media%20icons%20on,to%20easily%20search%20you%20up.

- De Witte, Marleen. “Pentecostal Forms Across Religious Divides: Media, Publicity, and the Limits of an Anthropology of Global Pentecostalism.” Religions 9, no. 7 (2018): 1–13.

- Einstein, Mara. Marketing Religion in a Commercial age. London: Routledge, 2008.

- Faimau, Gabriel. “The Emergence of Prophetic Ministries in Botswana: Self-Positioning and Appropriation of New Media.” Journal of Contemporary African Studies 36, no. 3 (2018): 369–385.

- Faimau, Gabriel, and Camden Behrens. “Facebooking Religion and the Technologization of the Religious Discourse: A Case Study of a Botswana-Based Prophetic Church.” Online Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet 11 (2016): 66–92.

- Faimau, Gabriel, and O. William, eds. New Media and the Mediatisation of Religion: An African Perspective. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2017.

- Golan, Oren, and Martini Michele. “Religious Live-Streaming: Constructing the Authentic in Real Time.” Information, Communication & Society 22, no. 3 (2019): 437–454.

- Grad, Iulia. “Religion, Advertising and Production of Meaning.” Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies 13, no. 38 (2014): 137–154.

- Juravle, Ariadna-Ioana, Constantin Sasu, and Geanina Constanta Spataru. “Religious Marketing.” SEA – Practical Application of Science IV, no. 2 (2016): 335–340.

- Laurence, Iannacone, R. Roger Finke, and Rodney Stark. “Deregulating Religion: The Economics of Church and State.” Differenz und Integration 28 (1996): 462–466.

- Lindhardt, Martin. “Introduction: Presence and Impact of Pentecostal/Charismatic Christianity in Africa.” In Pentecostalism in Africa, edited by Martin Lindhardt, 1–53. Leiden: Brill, 2015.

- Meyer, Birgit. “‘There Is a Spirit in That Image’: Mass-Produced Jesus Pictures and Protestant-Pentecostal Animation in Ghana.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 52, no. 1 (2010): 100–130.

- Meyer, Birgit. “Picturing the Invisible: Visual Culture and the Study of Religion.” Method and Theory in the Study of Religion 27 (2015): 333–360.

- Morehouse, Jordan, and Adam J. Saffer. “Promoting the Faith: Examining Megachurches’ Audience-Centric Advertising Strategies on Social Media.” Journal of Advertising 50, no. 4 (2021): 408–422.

- Musoni, Philip, Francis Machingura, and Attwell Mamvuto. “Religious Artefacts, Practices and Symbols in the Johane Masowe Chishanu YeNyenyedzi Church in Zimbabwe: Interpreting Visual Narratives.” Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae 46, no. 1 (2020): 1–17.

- Packard, Grant, Sarah G. Moore, and Brent McFerran. “(I'm) Happy to Help (You): The Impact of Personal Pronoun Use in Custumer-Firm Interactions.” Journal of Marketing Research 55, no. 4 (2018): 541–556.

- Percy, Martyn. “The Church in the Market Place: Advertising and Religion in a Secular Age.” Journal of Contemporary Religion 15, no. 1 (2000): 97–119.

- Premawardhana, Devaka. “Expecting the Unexpected: Pentecostal Miracles as Performance, Production, and Placeholder.” In Miracles: An Exercise in Comparative Philosophy of Religion, edited by Karen R. Zwier, David L. Weddle, and Timothy D. Knepper, 67–84. Cham: Springer, 2022.

- Ray, Anupama, Agarwal Prerna, K. Maurya Chandresh, and Gargi B. Dasgupta. “Creative Tagline Generation Framework for Product Advertisement.” IBM Journal of Research and Development 63, no. 1 (2019): 6-1.

- Statista. “Number of Internet and Social Media Users Worldwide as of January 2024.” Accessed March 20, 2024. https://www.statista.com/statistics/617136/digital-population-worldwide/, 2024.

- Straub, Jeffrey P. “The Pentecostalization of Global Christianity and the Challenge for Cessationism.” Detroit Baptist Seminary Journal 21 (2016): 207–234.

- Tilson, Donn James, and Anuradha Venkateswaran. “Toward a Covenantal Model of Public Relations: Hindu Faith Communities and Devotional-Promotional Communication.” Journal of Media and Religion 5, no. 2 (2006): 111–133.

- Torresi, Ira. Translating Promotional and Advertising Texts. London: Routledge, 2010.

- Ukah, Asonzeh Franklin-Kennedy. African Christianities: Features, Promises and Problems. Mainz: Johannes Gutenbertg-Universität, 2007.

- Ukah, Azonseh F.K. “Roadside Pentecostalism: Religious Advertising in Nigeria and the Marketing of Charisma.” Critical Interventions 2, no. 1–2 (2008): 125–141.

- Wariboko, Nimi. “Pentecostalism in Africa.” In Oxford Research Encyclopaedia of African History, edited by Thomas Spear, 1–24. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Yip, Jeaney, and Susan Ainsworth. “‘We Aim to Provide Excellent Service to Everyone Who Comes to Church!’: Marketing Mega-Churches in Singapore.” Social Compass 60, no. 4 (2013): 503–516.