Abstract

Medical schools are increasingly utilising remote learning. Remote learning can take many forms such as online lectures, small group tutorials, virtual clinical skills sessions, and online case presentations. Remote learning presents both challenges and opportunities for students globally. This article shares twelve tips from senior medical students, based on the author’s personal experience of remote learning and the relevant literature, to help others maximise the benefits of both synchronous and asynchronous remote learning. The authors include guidance on how to approach the remote format, embrace the use of technology, detail helpful open-access resources, and encourage students to become independent learners.

Introduction

In recent years, medical education has increasingly used new teaching methods, moving away from traditional classroom environments, and incorporating remote learning formats. As technology has become more accessible, medical schools internationally have started to include online distanced learning in the delivery of their courses (Harden and Hart Citation2002). This trend appears in both high and low-income countries (Frehywot et al. Citation2013; Back et al. Citation2015). As a relatively novel teaching method, definitions for E-learning, distance learning and remote learning are inconsistent (Davies et al. Citation2005; Ruiz et al. Citation2006; Berg Citation2008; Masic Citation2008; Moore et al. Citation2011). In this article, we define ‘remote learning’ as ‘learning when the learner and source of information are separated by time and/or distance and cannot meet in a traditional face-to-face setting, inclusive of any personal study time in replacement of clinical or lecture-based learning.’ Remote learning separated only by distance can be described as synchronous, whilst asynchronous learning includes both separation by time and distance.

As final year medical students in the United Kingdom, we have witnessed a gradual uptake of remote learning during our medical education. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has forced medical schools internationally to accelerate the adoption of remote learning (Ebrahimi et al. Citation2020; Hanad et al. Citation2020; Utama et al. Citation2020). This has taken synchronous forms such as webinars, online tutorials and virtual clinical skills sessions, as well as asynchronous forms such as pre-recorded lectures and presentations. Medical schools are likely to continue to use remote learning as a tool to supplement teaching beyond the current pandemic (Ebrahimi et al. Citation2020). This may include the use of online teaching during pre-clinical years and for students placed in clinical settings away from their primary university campus.

Remote learning offers its own unique benefits. Eliminating the need for travel can save time and money. Students may experience a wide variety of difficulties in attending classroom teaching, and remote learning may enable these student groups to better engage. Asynchronous teaching allows students to pace their own work, use their preferred learning styles, and set their own working hours (Mukhtar et al. Citation2020). Synchronous teaching helps promote interactive learning and provides the opportunity for immediate feedback (Chen et al. Citation2005). Challenges of remote learning include a heavy reliance on technology which may disadvantage students who have limited access to these resources. There may also be a variable quality of teaching delivered, due to the familiarity of the facilitator with teaching software. Finally, working in a remote environment may promote disengagement and distraction, and limit indirect learning which occurs on clinical placements (Walsh Citation2015; O’Doherty et al. Citation2018).

In this article, we present twelve tips based on personal experience and wider literature for medical students to maximise the effectiveness of remote learning.

Tip 1

Plan your schedule

Planning a weekly schedule and establishing a sustainable routine are fundamental to students balancing the components remote learning incorporates. With the increased uptake of remote teaching methods, students may have to organise their time between clinical placement, synchronous teaching, asynchronous teaching, and independent study. We have found that scheduling protected time for each component ensures we are able to switch between the different modalities throughout the day. In addition, an effective schedule will incorporate flexible working hours, adapted to a student’s preferred working times, which has been shown to positively affect productivity (Shepard et al. Citation1996).

A sustainable routine can involve incorporating regular breaks and planning weekly study sessions with peers. Regular breaks will leave students feeling refreshed and ensure good work proficiency (Galinsky et al. Citation2007; Epstein et al. Citation2016). This is particularly important as student’s routines are likely to be more sedentary, where they may experience increased levels of fatigue from high screen use. Effective breaks should include a postural change which can delay overall fatigue and promote concentration (Thorp et al. Citation2014). Additionally, we have found that planned collaborative learning sessions with peers have helped solidify structure and hold individuals accountable, especially when their study timetable can be flexible. An example of this could be bi-weekly Zoom sessions for OSCE practice.

Tip 2

Increase learning by using a greater variety of resources and range of formats

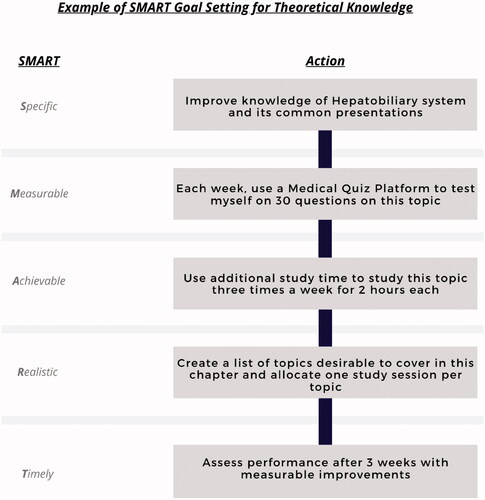

While attending clinical placements medical students learn in a wide variety of settings, using visual, auditory, reading and kinaesthetic (VARK) learning methods (Fleming and Mills Citation1992; Kharb et al. Citation2013; Ojeh et al. Citation2017). Examples of this are clinician observation, partaking in Multi-Disciplinary Team (MDT) meetings, reading patient notes and carrying out procedures respectively. Remote learning cannot completely replicate the educational opportunities offered in the clinical setting. However, medical students can use diverse resources incorporating various media types to simulate each VARK learning style (). Studying resources which present the same ideas in different ways will help students develop their understanding of complex concepts and allows them to apply their preferred learning approach (Ainsworth Citation2008; Won et al. Citation2014). We found combining different resources in a study session the most effective way to consolidate our learning and have suggested a model for students ().

Figure 1. Example student journey showing how to utilise resources to learn different aspects of the same condition. Full resource list available in . (VARK style is learning modality where V: visual; A: auditory; R/W: read/write; K: kinaesthetic).

Table 1. A diverse list of resources for medical students to use whilst remote learning.

Tip 3

Use note-taking software and flashcards to keep focussed during online synchronous lectures

Medical students may find themselves distracted during online synchronous medical lectures (Dobson Citation2012; Dost et al. Citation2020). We have found that utilisation of both flashcard and note-taking software are beneficial in maintaining focus during remote learning. By creating personalised notes or flashcards, the student remains actively engaged with the tutor and the material presented in real time. For complex subjects which require more extensive notes, we recommend using note taking applications (). Some of these apps allow the student to synchronise notes with lecture recordings, causing notes to be displayed at the time they were made, during lecture playback. We found this particularly useful when revisiting a topic many months later.

Flashcards are small, mobile study aids which are highly effective in promoting knowledge retention, incorporating both active recall and spaced repetition (Dobson Citation2012). This note-taking format specifically complements synchronous teaching, which is paced by the tutor and therefore does not allow time for extensive note taking. Flashcards are valuable in this situation, where students can note down key ideas. From personal experience we have found that free flashcard software such as Anki or Quizlet (), are beneficial as they allow easy integration of diagrams and pictures into the cards. Furthermore, these can be accessed regardless of location and across multiple devices.

Tip 4

Recall information with question banks to deepen understanding

While attending clinical placement, students are required to draw on their retained knowledge to understand clinical scenarios. In a remote learning environment, students can readily access information and are not required to recall from memory. We found that we developed a reliance on resources during remote learning, which hindered our performance in the clinical environment. We attempted to practice active recall of whole topics using multiple choice questions (MCQ) for prompts, in order to increase our capacity to independently retrieve information. Repeated retrieval of information has been shown to be a potent technique for durable, long-term learning (Roediger and Karpicke Citation2006; Karpicke and Bauernschmidt Citation2011).

Normally, the MCQ format entices students to passively read the answer options, encouraging answer recognition without understanding topics in detail (Manns et al. Citation2003). Instead, students can aim to recall broader information surrounding the question stem before attempting the answer. Areas for recall could include differential diagnosis, investigations and management steps. We additionally found that completing MCQs with qualified doctors enabled us to better understand clinical reasoning in the context of complex problems.

Tip 5

Familiarise yourself with clinical procedures

Students may struggle to gain exposure to some clinical procedures as remote learning becomes more prevalent in medical training. Thorough preparation can help students gain the most from the experiences they do encounter. Watching videos of procedures recorded in a controlled environment with an optimal viewpoint can greatly improve understanding of a task, leading to better performance when performing it in the future (Orientale et al. Citation2008). For example, as medical students we had limited opportunities to observe and practice arterial blood gas (ABG) collection. We responded to this by watching a demonstration video during independent study, which helped us familiarise ourselves with the procedure, observe proper technique, and made us better equipped to explain the procedure to patients.

Through synchronous video sharing technologies, students may also request teaching with clinicians while watching procedural videos in sync. We found live narration from the tutor alongside a demonstrational video, especially in invasive or complex procedures such as surgery to be of the most value. Clinical procedures may be viewed at resources such as Geeky medics whilst surgical videos may be viewed at Surgery Theater ().

Tip 6

Seek out support to overcome social isolation

A unique challenge presented by remote learning is the potential for students to experience social isolation (Croft et al. Citation2010). In large online classes where students are not required to verbally engage or have webcams turned on, they may feel more socially disconnected. They may also spend increasing amounts of time studying independently with less support from friends. To overcome isolation, students could use group study spaces such as library rooms and cafes. These can provide a space for students to come together and jointly engage in remote sessions. If unable to meet, we have found scheduling short video-calls between teaching sessions or planning virtual lunchtime breaks with peers to be greatly beneficial to our mental wellbeing, as it replicates the social aspects of in-person teaching. Furthermore students should make extra effort to organise and attend social events outside of university commitments. Support services are also available, and students should be prepared to use these if required. Mobile apps can deliver accessible and high efficacy mental health interventions (Chandrashekar Citation2018). Free services available include university counselling services, online self-help apps (e.g. Headspace or Calm), and mental health charities specific to their region.

Tip 7

Practice phone and video consultations to build communication skills

Practicing video and telephone consultations can help develop communication skills. This is easily achieved while remote learning using phone calls or video communication platforms (). Throughout our training, we have observed that virtual consultations are becoming more widely used in clinical practice (Ebrahimi et al. Citation2020). Virtual consultations limit the use of non-verbal interactions, and therefore may improve verbal communication skills when practiced (Roberts and Osborn-Jenkins Citation2021). Scenarios we have found useful to practice include history taking, explaining management plans, breaking bad news and explaining medications. We found that working with a diverse range of peers can help replicate the different patient interactions encountered in clinical practice. We also took these opportunities to virtually assess peers, performing simplified examinations within the constraints of a video consultation. For example, measuring the respiratory rate or checking for signs of respiratory distress by asking the simulated patient to point the camera at their chest. As this task is unfamiliar to both patients and clinicians, clear and sensitive communication is required, making this valuable practice.

Tip 8

Practice examination skills with lay people using mark schemes and recordings

Practicing examination skills, although not unique to remote learning, remains a key learning tool and requirement of medical schools worldwide (Medical Council of India Citation1997; Cumming and Ross Citation2007; General Medical Council Citation2018; Liason Committee on Medical Education Citation2020). Simulated examinations may become a more prevalent means by which students practice with the growth of remote learning. Practice with lay people in a non-clinical environment provides a relaxed setting where students can familiarise themselves with the routines of physical examinations (Rudland et al. Citation2008). Non-medically trained friends and family more realistically reflect the knowledge base of a typical patient, encouraging students to use appropriate terminology and improve communication techniques during clinical examinations (Duvivier et al. Citation2012). Practicing examinations remotely means students may build confidence in a low-pressure environment, however they may receive limited guidance or feedback from untrained peers. We have found it helpful to provide lay people with mark schemes to ensure clinical examinations are assessed competently. Furthermore, filming examinations and sending them to medical colleagues can provide deeper evaluation.

Tip 9

Utilise features of video-communication technology to overcome barriers

Video-communication platforms are used extensively throughout remote education. Students should allow time to familiarise themselves with these platforms and manage their expectations accordingly. One advantage of this technology is students may find participation online less intimidating, which can increase their interaction within the virtual class (Ni Citation2013). However, for higher-anxiety individuals, seeing one’s own picture on-screen can heighten stress and intensify affective reactions such as anger and dislike (Wegge Citation2006). Students should familiarise themselves with the technology utilised and be aware that it may take some time to build confidence in their use.

We have found turning off self-view helps us better engage in a webinar, whilst setting up a virtual background allows privacy, which can be useful if studying from a home environment. We also found that changing to remote lectures initially impacted our motivation and engagement, as the virtual modality can feel impersonal. Verbal communication with the tutor can be difficult in large sessions, however students can easily use the chat function to ask or answer questions. Active use of this function will ensure increased motivation and engagement throughout the session.

Tip 10

Seize opportunities to collaborate across clinical sites to produce medical literature

Remote learning allows greater connectivity between clinicians and students placed at different locations, which may have been previously limited by distance. This allows students to remain proactive members of research projects even when removed from hospital settings, thus promoting opportunities to contribute to academic journals. Audits in particular are well suited to collaboration as students can provide assistance with data input and statistical analysis remotely. Developing an understanding of medical research whilst at medical school is extremely important, as clinicians are expected to practice evidence-based medicine (Sackett Citation1997; General Medical Council Citation2013; Liason Committee on Medical Education Citation2020). Participation in publications amongst students has been shown to be associated with later academic success (Amgad et al. Citation2015). We encourage students to reach out to medical professionals and ask for opportunities to participate in research projects, highlighting their capacity to work remotely. For example, students may offer to help conduct a literature review to help assist clinicians planning case reports or quality improvement projects. This is particularly useful as students will often move between geographical sites and hospitals. Students can also form remote journal clubs and use them to critically appraise or work on literature with peers.

Tip 11

Seek out clinicians to facilitate additional virtual small group teaching sessions

Small group teaching is suggested to be a more effective and generally preferred method of teaching amongst medical students (Singh et al. Citation2016). It allows students to discuss complex content and practice problem solving using relevant skills, before finally reflecting on performance and outcomes (Steinert Citation1996). We recommend students ask clinicians whether they can facilitate virtual small group teaching sessions and expect that as remote teaching becomes more widely used, clinicians will likely have increased capabilities to lead such distanced sessions. Organising these additional sessions outside of the normal curriculum allows students to self-direct learning, thereby focusing on perceived areas of weakness to gain maximum benefit.

This tip requires students to explore their own contacts. We have found speaking to clinical supervisors, tutors and senior peers provides a good starting place to find willing clinicians. Further to this, students can join university societies and access additional small group teaching which are often free of charge. Additionally, students can ask other students in their year groups if and how they are accessing any extra teaching. Finally, we also found it useful to join MDT meetings remotely, which provided the opportunity to be involved in genuine clinical scenarios described by tutors. This helped emphasise important factors of clinical care.

Tip 12

Use SMART target setting to focus your remote learning

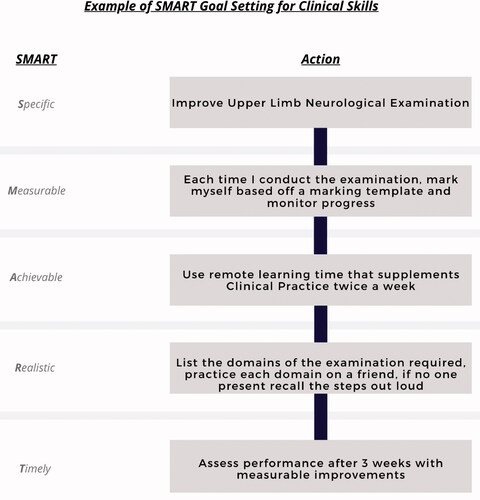

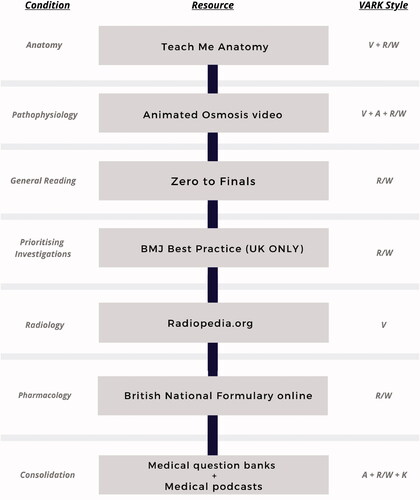

Remote learning can shift the onus of meeting curriculum standards more heavily on to the student, as they may not receive the same level of guidance from tutors or have feedback readily available from peers. Students can maintain curriculum focus by setting goals. We suggest using SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic and Timely) targets whilst remote learning to achieve focussed and varied study around course syllabi. Completing small, structured goals using this technique has been shown to improve work efficiency (Chang et al. Citation2011; Aghera et al. Citation2018). SMART targets can be applied to both theoretical and practical aspects of medicine ( and ). They can also be integrated into revision timetables to support overall course progression. For example, we created SMART targets from our timetabled topics, which helped us competently work through the curriculum whilst tracking our progress. An example of a curriculum timetable is available at Zero To Finals ().

Conclusion

Medical schools are increasingly transitioning to remote learning. We have presented twelve tips from medical students, for medical students, to support this change.

Our tips focus on developing independent study techniques with self-designed routines and scheduled breaks suited to the individual. We suggest using diverse resources including flashcards, question banks, and demonstrative videos to their full potential to aid students’ learning within remote formats. Furthermore, peer support can be invaluable to help combat social isolation, develop communication skills and practice examinations. Successful adaptation to video communication platforms will help students engage with teaching, collaborate on literature, and receive small group teaching from experienced clinicians. Whilst engaging with all these different tips, SMART targets can help maintain an overall focus on the curriculum for the student.

From our personal experience, a fusion of remote learning and traditional medical school teaching has been very effective, and we have used remote sessions as an opportunity to solidify learning points from our clinical teaching. We envisage many of the techniques utilised here will also help prepare us for professional life, which similarly now incorporates more virtual care.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sagar Mittal

Sagar Mittal, BSc, is a final year medical student at King's College London, with an iBSc in Medical Sciences with Biomedical Engineering from Imperial College London.

Victoria Lau

Victoria Lau, BSc, is a final year medical student at King's College London, with an iBSc in Human Nutrition and Metabolism from King's College London.

Katie Prior

Katie Prior, BSc, is a final year medical student at King's College London, with an iBSc in Human Nutrition and Metabolism from King's College London.

Joseph Ewer

Joseph Ewer, BSc, is a final year medical student at King's College London, with an iBSc in Anatomy, Development and Human Biology from King's College London.

References

- Aghera A, Emery M, Bounds R, Bush C, Stansfield RB, Gillett B, Santen SA. 2018. A randomized trial of SMART goal enhanced debriefing after simulation to promote educational actions. West J Emerg Med. 19(1):112–120.

- Ainsworth S. 2008. The educational value of multiple representations when learning complex scientific concepts. In: Gilbert JK, Reiner M, Nakhleh M, editors. Visualization: theory and practice in science education. Vol. 3, p. 191–208.

- Amgad M, Man Kin Tsui M, Liptrott SJ, Shash E. 2015. Medical student research: an integrated mixed-methods systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS One. 10(6):e0127470.

- Back DA, Behringer F, Harms T, Plener J, Sostmann K, Peters H. 2015. Survey of e-learning implementation and faculty support strategies in a cluster of mid-European medical schools. BMC Med Educ. 15(1):1–9.

- Berg GA. 2008. Distance learning | education | Britannica; [accessed 2020 Aug 7]. https://www.britannica.com/topic/distance-learning.

- Chandrashekar P. 2018. Do mental health mobile apps work: evidence and recommendations for designing high-efficacy mental health mobile apps. Mhealth. 4:6–6.

- Chang A, Chou CL, Teherani A, Hauer KE. 2011. Clinical skills-related learning goals of senior medical students after performance feedback. Med Educ. 45(9):878–885.

- Chen NS, Ko HS, Kinshuk, Lin T. 2005. A model for synchronous learning using the Internet. Innovat Educ Teach Int. 42(2):181–194.

- Croft N, Dalton A, Grant M. 2010. Overcoming isolation in distance learning: building a learning community through time and space. J Educ Built Environ. 5(1):27–64.

- Cumming A, Ross M. 2007. The Tuning Project for Medicine–learning outcomes for undergraduate medical education in Europe. Med Teach. 29(7):636–641.

- Davies H, Hall DMB, Harpin V, Pullan C. 2005. The role of distance learning in specialist medical training. Arch Dis Child. 90(3):279–283.

- Dobson JL. 2012. Effect of uniform versus expanding retrieval practice on the recall of physiology information. Adv Physiol Educ. 36(1):6–12.

- Dost S, Hossain A, Shehab M, Abdelwahed A, Al-Nusair L. 2020. Perceptions of medical students towards online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national cross-sectional survey of 2721 UK medical students. BMJ Open. 10(11):e042378–10.

- Duvivier RJ, van Geel K, van Dalen J, Scherpbier AJJA, van der Vleuten CPM. 2012. Learning physical examination skills outside timetabled training sessions: what happens and why? Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 17(3):339–355.

- Ebrahimi A, Ebrahimi S, Ashkani Esfahani S. 2020. How COVID-19 pandemic can lead to promotion of remote medical education and democratization of education? J Adv Med Educ Prof. 8(3):144–145.

- Epstein DA, Avrahami D, Biehl JT. 2016. Taking 5: work-breaks, productivity, and opportunities for personal informatics for knowledge workers. In Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – Proceedings; New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. p. 673–684.

- Fleming ND, Mills C. 1992. Not another inventory, rather a catalyst for reflection. To Improve Acad. 11(1):137–155.

- Frehywot S, Vovides Y, Talib Z, Mikhail N, Ross H, Wohltjen H, Bedada S, Korhumel K, Koumare AK, Scott J, et al. 2013. E-learning in medical education in resource constrained low- and middle-income countries . Hum Resour Health. 11(4):4–15.

- Galinsky T, Swanson N, Sauter S, Dunkin R, Hurrell J, Schleifer L. 2007. Supplementary breaks and stretching exercises for data entry operators: a follow-up field study. Am J Ind Med. 50(7):519–527.

- General Medical Council. 2013. Good practice in research and Consent to research. www.gmc-uk.org/guidance.

- General Medical Council. 2018. Outcomes for graduates 2018. https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/dc11326-outcomes-for-graduates-2018_pdf-75040796.pdf.

- Hanad A, Mohammed A, Hussein E. 2020. COVID-19 and medical education. Lancet Infect Dis. 20(7):777–778.

- Harden RM, Hart IR. 2002. An international virtual medical school (IVIMEDS): the future for medical education? Med Teach. 24(3) :261–267.

- Karpicke JD, Bauernschmidt A. 2011. Spaced retrieval: absolute spacing enhances learning regardless of relative spacing. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 37:1250–1257.

- Kharb P, Samanta PP, Jindal M, Singh V. 2013. The learning styles and the preferred teaching-learning strategies of first year medical students. J Clin Diagn Res. 7(6):1089–1092.

- Liason Committee on Medical Education. 2020. Functions and structure of a medical school standards for accreditation of medical education programs leading to the MD degree. https://med-prod.med.wmich.edu/sites/default/files/2015-16_Functions-and-Structure-2015-6-16.pdf.

- Manns JR, Hopkins RO, Reed JM, Kitchener EG, Squire LR. 2003. Recognition memory and the human hippocampus. Neuron. 37(1):171–180.

- Masic I. 2008. E-learning as new method of medical education. Acta Inform Med. 16(2):102–117.

- Medical Council of India. (1997). Medical council of India regulations on graduate medical education. https://www.mciindia.org/CMS/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/GME_REGULATIONS-1.pdf.

- Moore JL, Dickson-Deane C, Galyen K. 2011. E-Learning, online learning, and distance learning environments: are they the same? Internet High Educ. 14(2):129–135.

- Mukhtar K, Javed K, Arooj M, Sethi A. 2020. Advantages, limitations and recommendations for online learning during covid-19 pandemic era. Pak J Med Sci. 36(COVID19-S4):S27–S31.

- Ni AY. 2013. Comparing the effectiveness of classroom and online learning: teaching research methods. J Public Aff Educ. 19(2):199–215.

- O’Doherty D, Dromey M, Lougheed J, Hannigan A, Last J, Mcgrath D. 2018. Barriers and solutions to online learning in medical education – an integrative review. El Día Médico. 20(22):832–834.

- Ojeh N, Sobers-Grannum N, Gaur U, Udupa A, Majumder AA. 2017. Learning style preferences: a study of pre-clinical medical students in Barbados. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 5(185):186.

- Orientale E, Kosowicz L, Alerte A, Pfeiffer C, Harrington K, Palley J, Brown S, Sapieha-yanchak T. 2008. Using web-based video to enhance physical examination skills in medical students. Fam Med. 40:471–476.

- Roberts LC, Osborn-Jenkins L. 2021. Delivering remote consultations: talking the talk. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 52(July):102275.

- Roediger H, Karpicke J. 2006. The power of testing memory basic research and implications for educational practice. Perspect Psychol Sci. 1(3):181–210.

- Rudland J, Wilkinson T, Smith-Han K, Thompson-Fawcett M. 2008. “You can do it late at night or in the morning. You can do it at home, I did it with my flatmate.” The educational impact of an OSCE. Med Teach. 30(2):206–211.

- Ruiz JG, Mintzer MJ, Leipzig RM. 2006. The impact of e-learning in medical education. Acad Med. 81(3):207–212.

- Sackett DL. 1997. Evidence-based medicine. Semin Perinatol. 21(1):3–5.

- Shepard E, Thomas J, C, Douglas K. 1996. Flexible work hours and productivity: some evidence from the pharmaceutical industry. Indust Relat. 35(1):123–139.

- Singh K, Katyal R, Singh A, Joshi H, Chandra S. 2016. Assessment of effectiveness of small group teaching among medical students. J Contemp Med Edu. 4(4):145.

- Steinert Y. 1996. Twelve tips for effective small-group teaching in the health professions. Med Teach. 18(3) :203–207.

- Thorp AA, Kingwell BA, Owen N, Dunstan DW. 2014. Breaking up workplace sitting time with intermittent standing bouts improves fatigue and musculoskeletal discomfort in overweight/obese office workers. Occup Environ Med. 71(11):765–771.

- Utama MR, Levani Y, Paramita AL. 2020. Medical students’ perspectives about distance learning during the diabetes insipidus in patients with traumatic severe brain injury. Qanun Medika. 4(2):255–264.

- Walsh K. 2015. Mobile learning in medical education: review. Ethiop J Health Sci. 25(4):363–366.

- Wegge J. 2006. Communication via videoconference: Emotional and cognitive consequences of affective personality dispositions, seeing one’s own picture, and disturbing events. Human-Comp Interaction. 21(3):273–318.

- Won M, Yoon H, Treagust DF. 2014. Students’ learning strategies with multiple representations: explanations of the human breathing mechanism. Sci Ed. 98(5):840–866.