Abstract

Background

Mistreatment in medical school is a wicked or complex problem demonstrating inter-relatedness and dynamicity of factors that affect students. Many studies have outlined the causes, perceptions, and negative consequences of mistreatment; however, a comprehensive mental model of public humiliation, the most common type of mistreatment, is still incomplete. This study aims to provide insight into the reasons why public humiliation in medical school continues to be a problem despite existing for decades, and to propose a shift in paradigm that potentially improve these incidents.

Method

A systems thinking approach is used to conceptualize related components of public humiliation and student behavior. System dynamics modeling was conducted through narrative review, developing a causal loop diagram (CLD), and validation of results with 60 medical students and 40 medical educators.

Results

Findings from the narrative review outlined key variables, interconnections and five emerging themes: etiology, eustress, motivation, distress, and self-esteem. The themes were conceptualized and constructed into feedback loops as a basis for the CLD. Finally, the mental model proposes three major systems underlying the consequences. The “No Pain, No Gain” illustrates the perception that stress positively drives learning, while “Stress Overload” displays the negative consequences of public humiliation. Lastly, “The Delayed Side Effect” refers to long-term side-effects on self-esteem.

Conclusion

The mental model illustrates how public humiliation has both immediate and delayed side-effects, simultaneously succeeding and failing at motivating student growth. Therefore, public humiliation requires continuous changes in perspective along with multiple interventions to overcome the vicious cycle.

Introduction

Mistreatment has been commonly known to existing in medical school. The incident is defined by the Association of American Medical College as disrespect for the dignity of others, including behaviors of sexual harassment, discrimination, public humiliation, psychological punishment, and more (Association of American Medical Colleges Citation2020). While there are many forms of mistreatment, public humiliation is not yet well conceptualized in the medical curriculum. Public humiliation is defined as a “created experience of embarrassment with negative intent on the part of the perpetrator” (Markman et al. Citation2019). A survey done in 2016 reported 21.2% of students have experienced public humiliation at least once in medical school. Unfortunately, 4 years later in 2020, the number increased to 21.8%, illustrating the need to address this issue (Association of American Medical Colleges Citation2020). Despite decades of well-systematized scientific evidence about the negative consequences (Fnais et al. Citation2014), public humiliation and its impact still exist and are difficult to be eradicated (Halim and Riding Citation2018).

Practice points

Public humiliation is a wicked problem which simple and linear solutions cannot solve easily.

A snapshot of benefit perpetuates the cycle of public humiliation.

Stress should be optimized because it can either increase or decrease drive to learn.

Long-term side-effects of public humiliation on self-esteem are inadequately monitored.

Public humiliation exists because of applying “fix that fail” by teachers.

Public humiliation most often originates from a misunderstanding among many educators that it is an effective pressure on students to motivate studying (Association of American Medical Colleges Citation2020). However, the act itself has both short-term and long-term implications on students that might be hidden or unseen by educators. For example, it generates stress among students and may lead to burnout, demotivation, and reducing confidence in clinical skills (Heru et al. Citation2009; Shdaifat et al. Citation2020). With students continuing to be unreasonably pressured, long-term consequences introduce lower student quality of life, academic performance, and overall satisfaction of curriculum, which faculty members should be concerned of.

Both short-term and long-term effects of public humiliation disclose a larger picture or mental model that consists of assumptions and beliefs behind the phenomenon. Kassebaum describes mistreatment as a “transgenerational legacy” where the act of abuse repeats in a perpetual cycle throughout the levels of training (Kassebaum and Cutler Citation1998). As the vicious cycle continues, it generates a culture among physicians that intrinsically believes that “tough love” maximizes productivity in students. This complexity makes apparent that public humiliation is not merely the sum of events but is rather a system with consequences and reinforcements. Thus, alleviating this issue not only solves mistreatment in the present, but also terminates future hierarchical structures in medical schools.

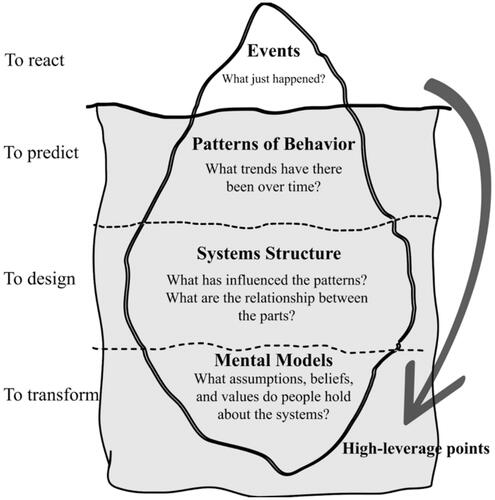

To thoroughly understand the depth and complexity of public humiliation, this study aims to explore and visualize the phenomenon through tools that will further help investigate leverage points. In 1973, Rittel and Webber firstly defined wicked problems or complex problems as problems that cannot be solved easily by conventional scientific and linear approaches (Rittel and Webber Citation1973). Public humiliation in medical school is potentially included in this type of problem. By applying the systems thinking approach (Kreuter et al. Citation2004), we aim to explore the systems structure and mental model that causes the behaviors or problems instead of reacting to public humiliation at only the superficial level (Ecochallenge Citation2022). In this work, we established two research questions to guide the review:

What is the mental model of public humiliation in medical school?

Why does public humiliation still exist as a vicious cycle in the 21st century?

Materials and methods

As public humiliation is a complex social phenomenon which requires a broad perspective to conceptualize, a system dynamics method was applied. Our key steps comprise of narrative review, development of causal loop diagram (CLD) and validation of results (Olivier et al. Citation2017).

Narrative review of literature

A narrative review is useful in melding together many components of information to comprehend this occurrence. Many aspects of a narrative review give an advantage that a narrow focus of a systematic review cannot provide, including an inclusive coverage of a wide range of issues (Green et al. Citation2006). A preliminary literature review was performed by searching in Google Scholar database to capture a transdisciplinary view. The key terms broadly comprise the definition of public humiliation, and its cause and effects. Only literature in health profession education and learning context were included. Then, two researchers separately reviewed and cooperatively made decisions on the final list of papers based on the title and abstract, where the main points potentially answered the research question. After the selection was done, all researchers went through all selected literature and qualitatively analyzed the data into emerging themes and held regular meetings to identify variables followed by refining the themes.

Developing of CLD

In parallel with qualitative analysis of the data, a table of variables was developed to capture causal linkage between variables for exploring the mental model (). A CLD, a systems dynamics tool (Bala et al. Citation2017; Dhirasasna and Sahin 2019), was used to explore the problem in deeper levels of systems which consist of variables and their relationships. The CLD consists of critical components and their interconnection constructed on Stella Architect ver. 1.9.4 (ISEE Systems Inc). Arrows and polarities (+ or −) indicate the direction and mechanism. For example, A − >+ B denotes that A causes a change on B in the same direction. On the other hand, A− >− B represents the change in the opposite direction. A feedback loop is created from variable to variable, which can be traced back to its originating variable. The loop can be categorized into two types: a balancing loop (designated by B) that generates stability over time and a reinforcing loop (designated by R) that compounds either growth or decay over time.

Table 1. Findings from narrative review and preliminary extraction of key variables, interconnections, and main themes.

Validation of results

The discussion for validation on the result was performed between different stakeholders in the school: systems methodology experts, medical school administrators, medical educators, and medical students. The systems expert firstly refined the result in technical aspects, followed by validating the mechanism and archetype of CLD. The validating session included focus group discussion and in-depth interview with sixty medical students and forty medical educators. The final version of CLD was conceptualized in three loops as a mental model of public humiliation presented in the “Results” section ().

Results

Narrative review

Extensive literature review was scoped in causes and effects of public humiliation which were grouped into five themes: etiology, eustress, motivation, distress, and self-esteem. demonstrates the model variables and their connections as initial substance for developing CLD.

CLD

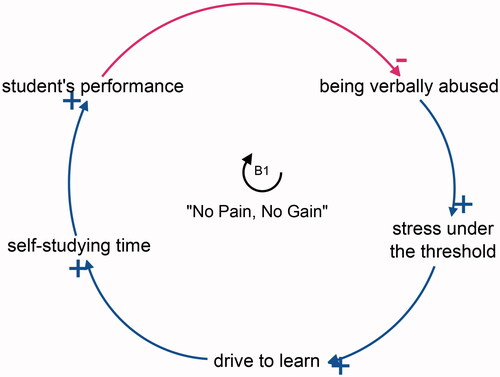

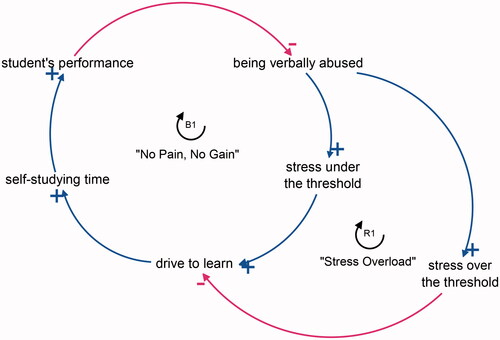

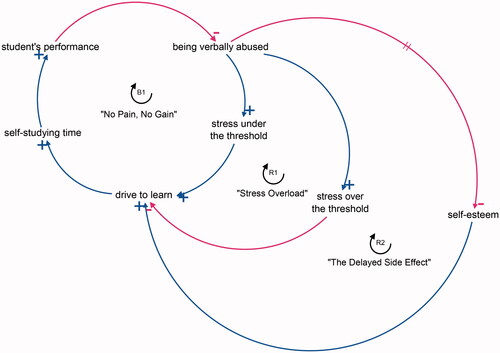

Based on findings from the narrative review, the synthesized CLD consists of three feedback loops underlying the wicked problem of public humiliation. The whole mental model comprises a balancing loop (B1: No Pain, No Gain), the first reinforcing loop (R1: Stress Overload), and the second reinforcing loop (R2: The Delayed Side Effect).

The first part of mental model: “No Pain, No Gain” etiology

In “No Pain, No Gain,” as students’ performance reduces below teacher’s perceived acceptable level, they are verbally abused by teachers, causing an immediate reaction that induces stress in students. With an incentive to perform better, students study more, resulting in higher performance in class that reduces abuse and humiliation from teachers. Consequently, due to the nature of the balancing loop, students’ performance will fluctuate based on whether they experience verbal abuse ().

The second part of mental model: Stress paradox in learning

“Stress Overload” describes the effect of verbal abuse in the form of public humiliation on unhealthy stress that negatively affects students. While stress can be an incentive for students to study more, as described in B1, accumulated stress over an individual’s threshold can damage a student’s drive to learn. As students become demotivated, they study less, leading to a decrease in performance in class and ultimately inducing abuse from teachers. This series of actions is a vicious cycle in which continuously reduces students’ performance over time. Conversely, less abuse will cause less distress leading to higher motivation and performance ().

The third part of mental model: Delayed side-effect on self-esteem

Due to “The Delayed Side Effect,” public humiliation causes a long-term effect on students’ self-esteem. Lower self-esteem decreases the drive to learn in the long term, leading to poorer performance that provokes abuse from teachers. The negative reinforcement loop can be both destructive and constructive depending on the amount of public humiliation and its effects on self-esteem and stress ().

Conclusion

The mental model seen in explains how public humiliation has both immediate and delayed side-effects, simultaneously succeeding and failing at motivating student growth. Mapping the interrelation of these elements helps us realize that the wicked problem is deeply rooted in the values and beliefs of educators, and that this complex problem requires more than just a onetime event to solve the issue.

Discussion: “fix that fail”

The CLD allows us to understand that many teachers continue to embarrass their students as they only see the short snapshot of benefits that immediately follow public humiliation and fail to see the long-term effects on student’s psychological well-being. As a result, seeing instant responses verifies their reasoning and perpetuates the cycle of abuse in medical school.

This is consistent with a “fix that fail” archetype (Kim Citation1995), an archetype in systems science that describes a “fix” intervention for the problem that is effective for only a short term but creates delayed “failed” consequences on stress and self-esteem. The B1 and R1 illustrate the immediate effects of humiliation, while the R2 has a delayed effect over time, where teachers see only a snapshot of benefits without being aware of the side-effects on student’s self-esteem.

Therefore, fixing public humiliation in medical school is not merely a reaction to a series of events, but requires a change in perspective over time. The interconnection of elements in the CLD shows that once verbal abuse has been redirected, it can synergize aspects of students’ persona that not only positively impact student performance, but quality of life and satisfaction in the medical curriculum as a whole.

Recommendation

Further investigations

The CLD, like all models, is a partial and incomplete reflection of reality. Despite the benefit of visualizing the mental model, quantitative systems dynamic modeling such as Behavior Over the Time and stock and flow diagram are recommended for further predictive models. Moreover, the diagram may have potential biases due to addition of some inferred linkages not directly identified in the literature. Although narrative review provides the breadth and depth of searching, systematic review should be applied to provide more inclusive perspectives.

As the validation of results was done from Thai participants, this mental model may be more applicable to Asian countries with similar cultures. The further mental model requires perspectives across different cultures along with contexualization before applying the result. Widening systems boundary with other psychosocial, environmental, and cultural aspects affecting mistreatment and public humiliation is recommended to expand upon this initial mental model.

Possible high-leverage interventions

As public humiliation is a complex problem, it is difficult to understand the issue with a long-term perspective instead of a snapshot view. The complexity, consequently, makes it nearly impossible to correct by simple solutions that only prohibit acts of public humiliation itself. Therefore, medical educators should treat this problem with complexity awareness as a golden rule for further intervention.

Multiple interventions should be applied to shift from the snapshot of “No Pain, No Gain” into a virtuous and sustainable cycle in grooming healthy students. The ideal student is a motivated and competent learner who keeps improving themselves without the need of aggressive verbal stimulation from their teacher. So, we proposed highly connected variables as candidates for possible leverage points: stress, being verbally abused, and self-esteem.

Firstly, to address the misconceptions from a snapshot view, continuity of close supervision is recommended to educators. Stress can either reinforce or reduce students’ motivation and has side-effects teachers should be aware of. As many educators address learning as merely events, continuity of close supervision can show long-term stress consequences of unhealthy teaching methods, offering insight beyond the snapshots of events.

Secondly, to avoid verbal abuse, educators should apply higher questioning methods in their teaching. Medical educators should always realize the purpose of each question and adjust it based on the scope of necessity. Advancing questioning from testing knowledge and comprehension to applying and analyzing knowledge as in Blooms’ taxonomy can add value to the learning experience (Taylor and Hamdy Citation2013). Questioning should be redesigned from knowledge-centered to learner-centered, which means questioning has not been used for knowledge inquiry but used for assisting the learners in modulating their learning as adults (Kost and Chen Citation2015).

Lastly, to boost and sustain student self-esteem, applying adult learning theory is recommended. Teachers should perceive that the students could learn by themselves. The role of teachers is to encourage intrinsic motivation and autonomous self-regulation for learning, as known that these are positively correlated with academic performance and well-being (Ten Cate et al. Citation2011). Furthermore, teachers should provide abundant resources and a safe psychological space where students can openly ask for academic help without abusive responses from their teacher. As the learning experience should be humanized, psychological well-being is fundamental to develop self-esteem, but public humiliation is an obstacle to students’ learning.

For this reason, after identifying possible high-leverage points with complexity awareness, multi-intervention can shift the paradigm from the fear model in hierarchical learning to a motivational environment. These modern approaches can not only end mistreatment but also succeed in grooming competent students continually.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this article was supported by Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University. The authors are grateful to Associate Professor Borwornsom Leerapan as the systems expert for the preliminary review and comments on the early draft of CLD.

Disclosure statement

The research is under the accountability of the authors and does not relate to the Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital Mahidol University.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Setthanan Jarukasemkit

Setthanan Jarukasemkit, Karen M Tam are fifth- and third-year medical students at the Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Thailand.

Phanuwich Kaewkamjornchai

Phanuwich Kaewkamjornchai, MD and Assistant Dean of Student Affairs at Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Thailand.

References

- Adib M, Ghiyasvandian S, Varaei S, Roushan Z. 2019. Relationship between academic motivation and self-directed learning in nursing students. J Pharm Res Int. 30(5):1–9.

- Arshad M, Haider Zaidi S, Mahmood D. 2015. Self-esteem & academic performance among university students. J Educ Pract. 6(1):156–162.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. 2020. Medical school graduation questionnaire. [accessed 2021 Jun 12]. https://www.aamc.org/media/33566/download.

- Bala BK, Arshad FM, Noh KM. 2017. Causal loop diagrams. In: System dynamics. Springer Texts in Business and Economics. Singapore: Springer; p. 37–51.

- Belsey J. 2014. Teaching by humiliation – why it should change. Virtual Mentor. 16(3):217–219.

- Boghossain P. 2012. Socratic Pedagogy: perplexity, humiliation, shame and a broken egg. Educ Philos Theory. 44:710–720.

- Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. 2005. Medical student distress: causes, consequences, and proposed solutions. Mayo Clin Proc. 80(12):1613–1622.

- Ecochallenge. 2022. A systems thinking model: the ice-berg. [accessed 2021 Nov 21]. https://ecochallenge.org/iceberg-model/.

- Fnais N, Soobiah C, Chen MH, Lillie E, Perrier L, Tashkhandi M, Straus SE, Mamdani M, Al-Omran M, Tricco AC. 2014. Harassment and discrimination in medical training: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Med. 89(5):817–827.

- Green BN, Johnson CD, Adams A. 2006. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. J Chiropr Med. 5(3):101–117.

- Halim UA, Riding DM. 2018. Systematic review of the prevalence, impact and mitigating strategies for bullying, undermining behaviour and harassment in the surgical workplace. J Br Surg. 105(11):1390–1397.

- Heru A, Gagne G, Strong D. 2009. Medical student mistreatment results in symptoms of posttraumatic stress. Acad Psychiatry. 33(4):302–306.

- Jirdehi MM, Asgari F, Tabari R, Leyli EK. 2018. Study the relationship between medical sciences students’ self-esteem and academic achievement of Guilan University of Medical Sciences. J Educ Health Promot. 7:52.

- Kaiseler M, Polman R, Nicholls A. 2009. Mental toughness, stress, stress appraisal, coping and coping effectiveness in sport. Pers Individ Differ. 47(7):728–733.

- Kassebaum D, Cutler E. 1998. On the culture of student abuse in medical school. Acad Med. 73(11):1149–1158.

- Kim DH. 1995. Systems archetypes as dynamic theories. Syst Thinker. 6(5):6–9.

- Kost A, Chen FM. 2015. Socrates was not a pimp. Acad Med. 90(1):20–24.

- Kreuter MW, De Rosa C, Howze EH, Baldwin GT. 2004. Understanding wicked problems: a key to advancing environmental health promotion. Health Educ Behav. 31(4):441–454.

- Markman JD, Soeprono TM, Combs HL, Cosgrove EM. 2019. Medical student mistreatment: understanding public humiliation. Med Educ Online. 24(1):1615367.

- Olivier J, Scott V, Gilson L, De Savigny D, Blachet K, Adam T. 2017. Applied systems thinking for Health systems research: a methodological handbook Maidenhead. Berkshire (UK): Open University Press.

- Rittel HW, Webber MM. 1973. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 4(2):155–169.

- Rudland JR, Golding C, Wilkinson TJ. 2020. The stress paradox: how stress can be good for learning. Med Educ. 54(1):40–45.

- Schuchert M. 1998. The relationship between verbal abuse of medical students and their confidence in their clinical abilities. Acad Med. 73(8):907–909.

- Seabrook M. 2004. Intimidation in medical education: students’ and teachers’ perspectives. Stud Higher Educ. 29(1):59–74.

- Shdaifat EA, Al Amer MM, Jamama AA. 2020. Verbal abuse and psychological disorders among nursing student interns in KSA. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 15(1):66–74.

- Shors TJ. 2004. Learning during stressful times. Learn Mem. 11(2):137–144.

- Taylor DCM, Hamdy H. 2013. Adult learning theories: implications for learning and teaching in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 83. Med Teach. 35(11):e1561–e1572.

- Ten Cate OTJ, Kusurkar RA, Williams GC. 2011. How self-determination theory can assist our understanding of the teaching and learning processes in medical education. AMEE Guide No. 59. Med Teach. 33(12):961–973.

- Webb C, Sedlacek W, Cohen D, Shields P, Gracely E, Hawkins M, Nieman L. 1997. The impact of nonacademic variables on performance at two medical schools. J Natl Med Assoc. 89(3):173–180.

- Zeigler-Hill V, Li H, Masri J, Smith A, Vonk J, Madson M, Zhang Q. 2013. Self-esteem instability and academic outcomes in American and Chinese college students. J Res Person. 47(5):455–463.

- Zimmerman, B. 1995. Self-efficacy in changing societies. New York: Cambridge University Press.