Abstract

Introduction

Examiners’ professional judgements of student performance are pivotal to making high-stakes decisions to ensure graduating medical students are competent to practise. Clinicians play a key role in assessment in medical education. They are qualified in their clinical area but may require support to further develop their understanding of assessment practices. However, there are limited studies on providing examiners with structured feedback on their assessment practices for professional development purposes.

Methods

This study adopts an interpretive paradigm to develop an understanding of clinical examiners’ interpretations of receiving structured feedback and its impacts on enhancing their assessment literacy and practice. Data were collected from 29 interviews with clinical examiners who assessed the final-year medical objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs) at one university.

Results

Inductive thematic analysis of these data revealed that the examiners considered the feedback to be useful with practical functions in facilitating communication, comparisons and self-reflection. However, the examiners’ level of confidence in the appropriateness of their assessment practices and difficulties in interpreting feedback could be barriers to adopting better practices.

Conclusion

Feedback for examiners needs to be practical, targeted, and relevant to support them making accountable and defensible judgements of student performance.

Keywords:

Introduction

Making professional judgements of student performance to ensure graduating medical students are competent and safe to practise is paramount in medical education (Malau-Aduli et al. Citation2021). The objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) assesses student performance under a simulated environment and is frequently used to make high-stakes decisions on student progression (Khan et al. Citation2013). OSCE examiners are typically clinicians who are qualified in their clinical specialities but may require support to further develop their understanding of assessment practices. Previous research has found that the reliability of examiner judgements is influenced by different sources of examiner-related errors (e.g. Harasym et al. Citation2008; Brannick et al. Citation2011; Hope and Cameron Citation2015). The 2020 Performance Assessment Consensus Statement recommended focusing on examiners’ conduct, behaviours and bias in OSCE examiner training (Boursicot et al. Citation2021) to enhance the validity and reliability of examiners’ judgements. Clinical examiners are volunteers who may not be always available to attend training on assessment. Therefore, it is important that medical schools find ways to engage more effectively with examiners to develop their assessment practices through enhancing assessment literacy.

Practice points

Practical, targeted and relevant feedback supports examiners making accountable and defensible judgements of student performance.

Providing examiners with feedback could facilitate communication, comparisons and self-reflection.

Examiners’ confidence in the appropriateness of their assessment practices and difficulties in interpreting feedback could impact the effectiveness of feedback.

Resources should be allocated to provide clinical examiners with timely and regular feedback.

Co-designing feedback with examiners could ensure the feedback provided addresses their professional development needs.

Theoretical framework

Assessment literacy is defined as the understanding of the process of how academic judgements are made (JISC Citation2015). It involves examiners developing skills and knowledge to assess student learning validly and reliably according to the marking criteria, as well as interpreting assessment data and feedback (Queensland Curriculum and Assessment Authority Citation2019). Providing clinical examiners with direct structured feedback for professional development purposes could be a way to initiate potential changes in their conceptual understanding of assessment and behaviour to enhance assessment literacy and the validity and reliability of their judgements (Warm et al. Citation2018).

There are, so far, few theoretically informed studies (e.g. Sturman et al. Citation2017; Crossley et al. Citation2019) exploring the provision of feedback to examiners on their marking practices for professional development. Crossley et al. (Citation2019) found that after examiners have received their comparative performance data, a number of different mechanisms are in play to determine how examiners considered changing their assessment practices. Given that a main function of feedback is to improve subsequent practices through making evaluative judgements about the strengths and weaknesses of one’s practice (Tai et al. Citation2018), not providing feedback to clinical examiners is a missed opportunity to enhance their assessment literacy.

To address the inconsistency of examiners’ judgements of student performance in the context of this study, we hypothesised that providing examiners with structured feedback on their marking behaviour could be a starting point for developing conversations with examiners and providing professional development in assessment practice and literacy.

Study aims

This paper explored the effectiveness of structured feedback as part of a wider mixed-methods case study exploring the consistency of examiners’ judgements in the exit OSCE for final-year medical students (Wong Citation2019). Applying the conceptual framework of assessment literacy, we adopted an interpretive paradigm (Bunniss and Kelly Citation2010) which focused on developing an understanding of the effectiveness of providing examiners with structured feedback by addressing the following research question:

What are examiners’ perceptions of the factors that impact the effectiveness of structured feedback on making changes to their marking behaviour?

Methods

This study considers the qualitative data collected before (in the explanatory sequential design phase) and after (in the exploratory sequential design phase) the examiners received their structured feedback (Creswell Citation2014).

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the University’s Behavioural & Social Sciences Ethical Review Committee (approval no: 2013001070).

Participants

Over 100 volunteer examiners were involved in the annual final medical OSCE assessing more than 350 students who were required to pass the OSCE to graduate. For training purposes, examiners were provided with written information on their role in the OSCE and all were expected to attend a short briefing led by an experienced examiner about the general marking guidelines and logistics of the exam on the day. The examiners had not previously received any structured feedback about their marking behaviour in OSCEs. We recruited examiners using convenience sampling. We emailed all examiners who were involved in assessing students in the final-year medical OSCE in 2013 and invited them to participate in receiving their feedback reports and attending semi-structured interviews before and after receiving the feedback.

Structured feedback to examiners

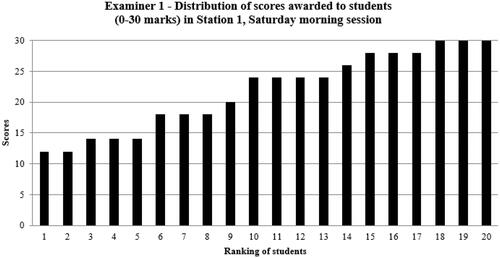

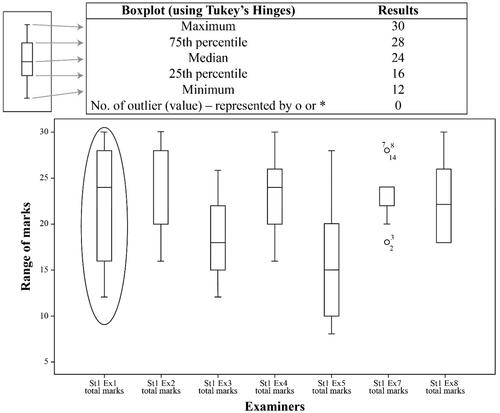

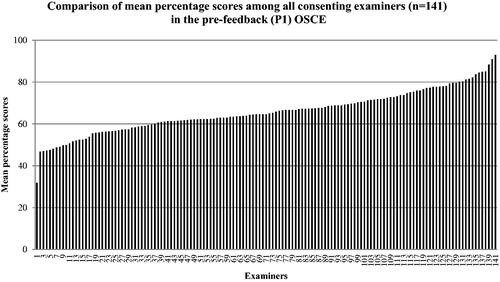

All examiners who consented to participate received a structured feedback report via email with the opportunity for further discussion about the feedback with the lead author. The report first briefly described the station and the marking criteria. It then provided the examiners with information at three levels: an individual examiner (), an individual OSCE station that an examiner assessed students in (), and an entire cohort of examiners () (Wong et al. Citation2020).

Figure 1. A bar graph showing Examiner 1’s scores given to each of the students in a station (Wong et al. Citation2020).

Figure 2. Boxplots comparing an examiner’s score with the other examiners in the same station (Wong et al. Citation2020).

Figure 3. A bar graph comparing an examiner’s mean percentage score given to students with the entire cohort of examiners (Wong et al. Citation2020).

A bar graph showing an examiner’s scores given to each of the students in a station.

A series of boxplots comparing an examiner’s maximum, medium and minimum scores, and the presence of outliers, with the other examiners in the same station.

A bar graph showing the comparison of an examiner’s mean percentage score given to students with the entire cohort of examiners. The position of an individual examiner was indicated on the continuum from the most to the least stringent examiners.

Data collection

The lead author interviewed all the consenting examiners. The pre-feedback interviews explored the examiners’ perceptions of the feedback:

In what ways do you think providing you with feedback on your OSCE marking of medical students, through comparison with your peers’ marks, assists in increasing the reliability of examiner scores?

The post-feedback interviews explored the usefulness of the structured feedback:

How do you find the feedback report provided, in terms of its usefulness in calibrating your judgement of student performance in the OSCE?

Have you used the information provided when you marked subsequent OSCE/clinical examinations? How? Why and why not?

All the interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. The lead author verified the accuracy of the transcription prior to analysing the pre-feedback and post-feedback interviews separately.

Data analysis

Following the interpretive paradigm (Bunniss and Kelly Citation2010), we conducted an inductive thematic analysis of the interview data to systematically explore the similarities within and across the interviews for concepts (Pascale Citation2011), and to identify the factors that impact the effectiveness of the structured feedback. The lead author first analysed the interviews using open coding (Merriam and Tisdell Citation2016) and axial coding (Corbin and Strauss Citation2015), which identified the characteristics of useful and not so useful aspects of the feedback. The lead author then identified the recurring patterns of the groupings established from the axial coding and consolidated them into themes (Merriam and Tisdell Citation2016). Subsequently, we identified the enablers and barriers that could impact the effectiveness of the structured feedback to enhance the examiners’ assessment practices.

Reflexivity

The lead author, who conducted all the interviews with the examiners and undertook the initial thematic analysis, was a full-time professional staff at the medical school when this research was conducted. The lead author acknowledged possible subjectivity in the interpretation of the interview data, and critically reflected on any prejudices that might affect the interpretations and discussed these with the research team. All authors, who are experts from medical education (CR and JT) and higher education (KM), engaged in the investigator triangulation to confirm and refine the findings (Merriam and Tisdell Citation2016) by independently reading a proportion of interviews and debating the identified factors.

Findings

A total of 141 out of 159 OSCE examiners consented to participate and received the structured feedback report. The lead author conducted 17 pre-feedback (identified by prefix 1) and 12 post-feedback semi-structured interviews (identified by prefix 2) at a time and place convenient to the examiners. The findings shown in illustrate the themes developed from the interview data and the associated enablers and barriers that influenced the effectiveness of feedback provided to the examiners.

Table 1. Two themes and the associated enablers and barriers that influenced the effectiveness of structured feedback.

We identified two themes in the thematic analysis. Theme 1: Examiners’ perceptions and Theme 2: Practical functions of feedback. The associated enablers to change were the examiners’ perceptions of the usefulness of the feedback (Enabler 1.1), and the practical nature of the process which they saw as a way to communicate (Enabler 2.1), compare (Enabler 2.2) and facilitate self-reflection (Enabler 2.3) to support them in enhancing their marking practice.

Enabler 1.1: Examiners’ perceptions of the usefulness of the feedback

The provision of structured feedback was perceived to be a novel practice for these examiners as it was the first time that they had an opportunity to compare their marking behaviour with others in the cohort. Examiners from the pre-feedback interviews discussed the potential usefulness of a structured feedback report commenting:

Yes, I think [feedback] would be great because that’s the big thing, isn’t it? If I'm marking everyone too leniently then I maybe need to bring it back to where everyone else is. That'd be a very useful thing to know. (Examiner 1.8)

A response from a first-time examiner in the post-feedback interview revealed that the structured feedback appeared to be particularly important for the less-experienced OSCE examiners:

I think [the] feedback form that you put together clearly is a lot of work and it’s quite useful and I find it interesting and I think it’s important to do to have standardisation of examining to improve…. it also makes you more robust and defensible if people argue about how they are assessed which is increasingly becoming an issue from what I understand. So, if you have a sound kind of underpinning to show it is equitable marking and that people are normalised in terms of examination approach and technique, then it just makes the process more robust and I think it’s a good idea. (Examiner 2.7)

One examiner discussed the importance and benefits of the structured feedback in supporting examiners to make robust, equitable and defensible judgements of student performance. Indeed, all but one of the examiners in the post-feedback interviews indicated that the structured feedback was useful in terms of reassuring them about their judgements and standardising the examiner judgements, for example:

[The feedback] makes me feel confident I'm probably doing the right thing by the student … I think it might let me go in there more confident[sic], confident that I'm being fair to the students. (Examiner 2.2)

The provision of structured and targeted feedback could be a way to starting a dialogue with clinical examiners about their assessment practices to enhance their fairness and defensibility of their judgements of student performance.

Enabler 2.1: A communication channel between the medical school and the examiners

The clinical examiners indicated three practical functions of the structured feedback that are enablers to support them to enhance their marking practices. The structured feedback acted as a channel for the medical school to communicate with the clinical examiners if their marking behaviour did not meet the school’s expectations:

I think [the feedback] would be helpful actually. Because I want to do what the school needs me to do and I want to do it properly. If I am being too lenient or too hard, I do want the school to let me know that because like I say very high stakes. If we let people through that aren’t safe, that’s a real problem. And if we don’t let people through, who really are going to be okay, then that’s a massive blow to them, so it’s very high stakes, so I want to know … I care how I am compared to what the school wants. (Examiner 1.3)

An examiner in the post-feedback interview welcomed the structured feedback as they had not previously received any communications from the medical school about their assessment practices:

But there was never any feedback. So, nobody ever says, you can’t – you’re too mean to the students. Because at the moment, we just come in. We do that day or two days, or half a day – or whatever we do – and then we go away and we don’t hear anything. So, there's never really been any feedback. Most of us – part of medicine is teaching and apprenticeship system is, I think, a very important part of medicine. (Examiner 2.1)

Communications from the medical school were minimal in terms of informing the validity and reliability of the examiners’ marking practices in the high-stakes OSCEs. The examiners indicated that understanding if their marking practices were on the stringent or lenient end was a good starting point in developing meaningful communications to clarify the medical school’s expectations for assessing the final-year medical students.

Enabler 2.2: A means of comparing examiners’ marking behaviour across the cohort

In the pre-feedback interviews, the examiners anticipated that they would be reassured when they realised that their marking behaviour was in line with that of other examiners in the same OSCE station:

I also think that … maybe some feedback as to how you might have performed in reference to other examiners for the same station would be very validating for your performance subsequently so that you might take it on board as being somewhat educational, so that you would approach that particular station or that type of station in a better manner for the next time. (Examiner 1.17)

The examiners reported that the comparison with the entire examiner cohort provided them with an indication of whether their marking behaviour was too lenient or stringent:

I think it’s interesting to see where you fit in relation to other examiners. And it gives you particularly when I haven’t examined in this format before. It’s my first time it was good to see … where you sit on this spectrum and that you are not being overly harsh [or] not particularly soft in your marking either. (Examiner 2.7)

The practical function of comparing the examiners’ marking behaviour was particularly relevant to the examiners who were assessing students in the high-stakes final-year OSCE for the first time.

Enabler 2.3: A means of facilitating examiners’ reflection on their marking behaviour

Examiners from the pre-feedback interviews expected that the feedback would generate reflection and discussion about their marking practices:

… I think it [the feedback] gives you a sense, probably does give you a sense of people's broader expectations and how you sit in that group. Whether it means then you sort of review, you know, you either review what you've done and think, yes, that's fair enough maybe I am too lenient or too stringent. Or maybe you'll say, well look you know I don't necessarily agree with that … I guess it gets a discussion going which makes everyone think more about how they're marking things. (Examiner 1.17)

This expectation was reinforced by the examiners in the post-feedback interviews. The examiners acknowledged that the structured feedback was insightful and encouraged self-reflection of their marking behaviour:

Well, I just did the OSCE on Saturday afternoon, so I already was aware of this [feedback], and yes, I was thinking about it all the time …. It was there thinking and now again, that was an OSCE station that was in an area that I wasn't familiar with…. So, it was not something that I specifically teach and know about. And I would've thought my marks — the distribution —

would've been similar to this [feedback]. So, I was thinking about it during the [OSCE]. Am I being too hard? Am I being too easy? What are the expectations, et cetera, in the OSCE station? (Examiner 2.3)

The examiners’ responses indicated that the practical functions of feedback acting as a communication channel, comparing examiners’ marking behaviour and facilitating their self-reflection could support them to enhance their marking practices.

The barrier identified under Theme 1: Examiners’ perceptions was their confidence in the appropriateness of their assessment practices (Barrier 1.1), and that under Theme 2: Practical functions was the difficulties in interpreting feedback which could potentially impede their adoption of better assessment practices (Barrier 2.1).

Barrier 1.1: Examiners’ confidence in the appropriateness of their assessment practices

The effectiveness of structured feedback in enhancing the validity and reliability of examiners’ judgements depends on how the examiners apply the feedback and make the decisions of whether changes of their judgement practices are required. The examiners in the pre-feedback interviews indicated that their rationale for not changing their behaviour was related to their personal views about assessment. For example, one examiner considered exam stress as a mitigating factor when awarding a grade:

… I'm [always] going to be lenient … a lot of medical students come through our practice. I know that they’re all pretty enthusiastic and I know they’re all pretty keen and motivated. And I know that different people react to exam stress in different ways. Some people are very calm and they just swan through it and some people are so … nervous that they just forget things and you can see the panic in their eyes and you know that they’re not really giving a representative effort of what they know. So that's why I'm lenient. I used to get really nervous before exams as well. That's probably why I go soft on them. (Examiner 1.16)

Examiners’ strong personal views about assessment and the inclusion of personal criteria made changes to their attitudes and assessment practices challenging.

Another examiner indicated that they might decide to retain their current marking behaviours after reflecting on the structured feedback provided:

But if the comparison showed that for me as an individual I was leaning too heavily one way or the other, then it would be an indication to think more carefully about it. I may decide that that's where I want to stay. (Examiner 1.9)

In the post-feedback interview, an examiner explained their unwillingness to change was related to their belief about how calibration of examiners’ marking should be conducted:

I am not so sure what impact it will have on my marking because I see that the marking should come from a clear understanding of what the requirements are for the different levels, a very clear demonstration of understanding shared by the examiners of what a pass mark is, and then what you know what really excellent looks like, and what is below the acceptable level for passing that particular student on that case station which is the thing that I really struggle with doing these exams. (Examiner 2.4)

Unclear expectations of different marking standards to differentiate student performance in the OSCE could contribute to the examiners’ resistance to change. They looked for additional guidance in collectively developing the marking standards of student performance. This led to the suggestion that establishing a shared understanding of the expectations among all OSCE examiners would be a relevant professional development strategy to enhance their assessment literacy.

Other examiners in the post-feedback interviews indicated that they were not going to change their marking practices because they did not see any need to act:

I don’t think I’ll mark differently because of where I sat on the spectrum. I thought my marking was reasonable I think the [statistics] were about where I expect that I would be. (Examiner 2.7)

They were satisfied with their positions when compared to those of their examiners’ cohort based on the structured feedback reports.

Barrier 2.1: Difficulties in interpreting the feedback

While in general, the examiners did not encounter any significant problems in understanding the information presented in the feedback report, for example,

I've got to say that I found the layout of the report really really easy to understand. (Examiner 2.1)

a few examiners asked questions about the boxplots showing the comparisons of an examiner’s mean, median and spread of marks to those of other examiners in the same OSCE station. Apart from that, most of the examiners did not find interpreting the presented information to be an issue. However, there is a risk in assuming too much or too little basic knowledge of data analysis and visual representations that examiners may have; one may display overly complicated or simplified graphs and thus create issues in interpretation and a potential barrier inhibiting the effectiveness of the feedback.

Discussion

Our findings indicate that the examiners’ perceptions of the usefulness of the feedback and its practical functions could enhance the effectiveness of the feedback to inform examiners of their assessment practices. The findings also reveal the challenges of changing the examiners’ marking behaviour based on the feedback provided when they were confident that their current assessment practices were appropriate. In addition, complicated statistical information or graphs might also hinder the examiners interpreting the given feedback.

Comparison with existing theory and literature

This study contributes to extending the literature investigating the effectiveness of providing clinical examiners with structured feedback as a form of professional development in assessment. The findings of this study suggested providing clinical examiners with feedback that is:

Practical (as a communication channel)

Targeted (as a means of comparisons), and

Relevant (as a means of providing useful information and facilitating self-reflection).

These factors are important considerations to adopt examiner feedback as part of their professional development as different underlying mechanisms such as ‘stabilising’ (p.787) or defence, influence examiners’ decisions of whether they make changes of their judgement behaviours upon receiving feedback (Crossley et al. Citation2019). These findings were broadly aligned with the core factors such as content, language and format of providing effective feedback in hierarchic professional contexts (Johnson Citation2016). For example, presenting useful and well-organised feedback content in easy-to-understand language as suggested by the examiners in this study.

Providing feedback and the opportunity for subsequent conversations between examiners and the medical school, or among the examiners, are also important to further develop the examiners’ assessment literacy and understanding of the process of making academic judgements (JISC Citation2015). These conversations are the starting points to create a community of examiners to discuss standards of assessments which will facilitate self-regulation and develop knowledge and understanding of assessment and feedback (Medland Citation2015, Citation2019). In our study, several examiners welcomed the feedback as an initial dialogue with the medical school. This was particularly important to them given the high-stakes nature of the assessment and their limited (once a year) engagement with the school. Through engaging in these conversations, examiners are on the path to developing a shared language of assessment literacy (Medland Citation2015, Citation2019) applicable to their context which could enhance their skills and knowledge in using the marking criteria to make valid and reliable judgements.

Our findings also suggested that examiners’ level of confidence in the appropriateness of their assessment practices, and difficulties in interpreting feedback could be barriers to adopting better practices. These barriers could impact examiners making evaluative judgements to identify the strengths and weaknesses of their own assessment practices (Tai et al. Citation2018). Although the feedback could act as a means to facilitate examiners’ self-reflection, examiners should be encouraged to take the initiative and be offered support to do so. Strengthening the enablers and addressing the barriers that influence the effectiveness of the structured feedback could contribute to developing examiners’ assessment literacy. It should be acknowledged, however, that providing individual structured feedback is a time-consuming task: dedicated resources are required to sustain the provision of regular feedback for professional development purposes.

Implications for educational practice

Given that the provision of feedback could be a starting point for developing meaningful conversations about assessment literacy, we suggest that medical schools consider allocating resources to enhance communications with clinical examiners and provide them with timely and regular feedback on their judgement behaviours. Establishing a Community of Practice (CoP) (Lave and Wenger Citation1991) to engage and connect with examiners could be included as ongoing professional development. The CoP allows the less-experienced examiners to learn or be mentored by experienced examiners, while experienced examiners could also learn about innovative assessment strategies from the new generation of examiners. The CoP also creates a platform for either face-to-face or online discussion on assessment initiatives and collaborations such as developing a shared understanding of assessment terminology and co-designing resources to advance the examiners’ assessment practices.

We acknowledge that it will always be challenging for clinical examiners to be involved in professional development in assessment. However, the findings of this study indicate that examiners are amenable to learning more and to connecting with the medical school. The provision of tailored and quality information by medical schools has the potential to engage clinical examiners developing a deeper understanding of assessment literacy and enhancing their abilities to make accountable and defensible judgements of student performance.

Implications for future research

Future research should explore the adaptability of the identified enablers and barriers that influence the effectiveness of feedback in different contexts of medical schools and across different types of assessments. Medical schools could also co-design the content of feedback with examiners to ensure that the feedback is fit for purpose to enhance their assessment literacy.

Methodological strengths and challenges

We have added to the limited scholarship related to providing clinical examiners with structured feedback as a form of professional development, rather than for quality assurance purposes. We acknowledge that this study only included clinical examiners from one medical school whose views might not be generalisable to other contexts. However, given that clinical examiners will continue to play an important role in OSCEs, the findings of the study highlight the enablers that will facilitate and the potential barriers that may hinder the feedback process for consideration.

Conclusion

Assessment literacy of examiners, particularly for high-stakes examinations, is critical to making decisions on students’ progression to the next stage of training. Providing practical, targeted, and relevant feedback to clinical examiners appears to be an additional strategy to better engage them with professional development in assessment. This could enhance clinical examiners’ assessment literacy to provide students with defensible and accountable judgements, and to ensure the quality of patient care delivered by graduating medical students to the public.

Glossary

Assessment literacy: Is defined as the understanding of the process of how academic judgements are made (JISC Citation2015).

JISC Citation2015. Assessment literacy. [Online]. [accessed 2021 July]. https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/transforming-assessment-and-feedback/assessment-literacies

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participating OSCE examiners at The University of Queensland for their time and contributions to the interviews.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Wai Yee Amy Wong

Wai Yee Amy Wong obtained her PhD in medical education through the School of Education and Faculty of Medicine at The University of Queensland in 2019, and is currently working as a Lecturer in the School of Nursing and Midwifery at Queen’s University Belfast.

Karen Moni

Karen Moni, PhD, is a higher education educator and disability researcher, and an Honorary Associate Professor affiliated with the School of Education at The University of Queensland.

Chris Roberts

Chris Roberts, MBChB, MMedSci, FRACGP, PhD, is a health professions educator and researcher, and an Honorary Professor affiliated with Sydney Medical School, The University of Sydney.

Jill Thistlethwaite

Jill Thistlethwaite, MBBS, MMEd, FRCGP, FRACGP, PhD, is a health professions education consultant, and an Adjunct Professor affiliated with the Faculty of Health at the University of Technology Sydney.

References

- Boursicot K, Kemp S, Wilkinson T, Findyartini A, Canning C, Cilliers F, Fuller R. 2021. Performance assessment: Consensus statement and recommendations from the 2020 Ottawa Conference. Med Teach. 43(1):58–67.

- Brannick MT, Erol-Korkmaz HT, Prewett M. 2011. A systematic review of the reliability of objective structured clinical examination scores. Med Educ. 45(12):1181–1189.

- Bunniss S, Kelly DR. 2010. Research paradigms in medical education research. Med Educ. 44(4):358–366.

- Corbin J, Strauss A. 2015. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE.

- Creswell JW. 2014. Educational research: planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th Pearson new international ed.). Harlow, Essex: Pearson.

- Crossley JGM, Groves J, Croke D, Brennan PA. 2019. Examiner training: a study of examiners making sense of norm-referenced feedback. Med Teach. 41(7):787–794.

- Harasym PH, Woloschuk W, Cunning L. 2008. Undesired variance due to examiner stringency/leniency effect in communication skill scores assessed in OSCEs. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 13(5):617–632.

- Hope D, Cameron H. 2015. Examiners are most lenient at the start of a two-day OSCE. Med Teach. 37(1):81–85.

- JISC. 2015. Assessment literacy. [Online]; [accessed 2021 Jul]. https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/transforming-assessment-and-feedback/assessment-literacies.

- Johnson M. 2016. Feedback effectiveness in professional learning contexts. Rev Educ. 4(2):195–229.

- Khan KZ, Ramachandran S, Gaunt K, Pushkar P. 2013. The objective structured clinical examination (OSCE): AMEE guide no. 81. Part I: An historical and theoretical perspective. Med Teach. 35(9):e1437–e1446.

- Lave J, Wenger E. 1991. Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Malau-Aduli BS, Hays RB, D’Souza K, Smith AM, Jones K, Turner R, Shires L, Smith J, Saad S, Richmond C, et al. 2021. Examiners’ decision-making processes in observation-based clinical examinations. Med Educ. 55(3):344–353.

- Medland E. 2015. Examining the assessment literacy of external examiners. Lond Rev Educ. 13(3):21–33.

- Medland E. 2019. I'm an assessment illiterate’: towards a shared discourse of assessment literacy for external examiners. Assess Eval High Educ. 44(4):565–580.

- Merriam SB, Tisdell EJ. 2016. Qualitative research: a guide to design and implementation, 4th ed. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass.

- Pascale CM. 2011. Cartographies of knowledge: exploring qualitative epistemologies. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE.

- Queensland Curriculum and Assessment Authority 2019. 7.2 Assessment literacy. [Online]; [accessed 2021 Jul]. https://www.qcaa.qld.edu.au/senior/certificates-and-qualifications/qce-qcia-handbook/7-the-assessment-system/7.2-assessment-literacy.

- Sturman N, Ostini R, Wong WY, Zhang J, David M. 2017. On the same page? The effect of GP examiner feedback on differences in rating severity in clinical assessments: a pre/post intervention study. BMC Med Educ. 17(1):101–101.

- Tai J, Ajjawi R, Boud D, Dawson P, Panadero E. 2018. Developing evaluative judgement. High Educ. 76(3):467–481.

- Warm E, Kelleher M, Kinnear B, Sall D. 2018. Feedback on feedback as a faculty development tool. J Grad Med Educ. 10(3):354–355.

- Wong WY. 2019. Consistency of examiner judgements on competency-based assessments: a case study in medical education [dissertation on the Internet]. St Lucia (QLD): The University of Queensland.

- Wong WYA, Roberts C, Thistlethwaite J. 2020. Impact of structured feedback on examiner judgements in objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs) using generalisability theory. Health Prof Educ. 6(2):271–281.