ABSTRACT

While the quality and nature of a PhD students’ relationship with their supervisors is widely regarded as pivotal for successfully completing their studies, the increasing use of multiple supervisors may challenge this relationship. This is the first study to use interviews with students and supervisors to explore students’ motivation in such supervisory arrangements. Our study is framed by Self-Determination Theory (SDT) as a means for understanding factors that enable (or inhibit) individuals’ motivation to learn, and Social Penetration Theory (SPT) for its perspectives on the development of relationships. Findings show that students’ self-disclosure fosters relatedness and enhances autonomy and competence, with motivation and well-being as a function of their relational needs being satisfied. As such, complementarities between SDT and SPT provide more nuanced insights into the influence of relatedness on student motivation and well-being.

Introduction

The aim of this study is to investigate the relational processes and their effects in PhD student–supervisor relationships, with a particular focus on the factors affecting students’ motivation and well-being. While research has investigated influences affecting subordinates’ behavior in workplace scenarios (Hofmans et al., Citation2019), studies regarding influences affecting PhD students’ motivation and well-being primarily focus on dyadic supervision arrangements (Harrison & Grant, Citation2015). Indeed, despite positive student experiences being linked to supervisors’ support and good communication (e.g. Bandura & Lyons, Citation2012; Barry et al., Citation2018; Pearson, Citation2012; Unda et al., Citation2020), there is a lack of research that examines the impact of relatedness and closenessFootnote1 where students engage with multiple supervisors (e.g. Hemer, Citation2012; Hutchings, Citation2017).

Our investigation is relevant and timely, as multiple supervisors are increasingly involved in the supervision of PhD students. This change is occurring in the United Kingdom (Cheng et al., Citation2016; Johansson & Yerrabati, Citation2017), the United States (Brooks & Heiland, Citation2007), Sweden, the Netherlands, and Australia (Bastalich, Citation2017; Wilkin et al., Citation2022). Given ‘the dynamic link between teacher and student motivation’, the effect of engaging with more than one supervisor may well impact students’ motivation and well-being as positive, autonomous, and competent scholars (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020, p. 68). Accordingly, we focus on understanding the relational dynamics in supervisory arrangements where students engage with more than one supervisor. In particular, we look at the effects of supervisor attributes (such as responsiveness and quality of support) and structural attributes (such as feedback, network size and degree of formality) on PhD students’ motivation and well-being.

To explore this issue, we frame our study in a manner consistent with two theories: Self-Determination Theory (SDT), as a framework for understanding the factors that enable (or inhibit) individuals’ motivation and propensity to learn (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020); and Social Penetration Theory (SPT) for perspectives on the development of relationships (Altman & Taylor, Citation1973; Carpenter & Greene, Citation2016). In particular, we focus on the nature and role of students’ dispositional, interpersonal, and situational attributions in their relationships with supervisors and the effects of resultant relatedness.Footnote2

As a qualitative approach is beneficial when little is known about the phenomenon (Edmondson & McManus, Citation2007), we interviewed students and supervisors in their natural setting. In particular, we focus on panel supervision where one student has a principal and at least one secondary supervisor, rather than group supervision where two or more doctoral students share several supervisors. Australia and New Zealand are selected as our context as their PhD supervision practices exhibit evident challenges that are consistent with international trends. These include time constraints, diverse student populations, a range of learning needs, differing motivations for studying, more structured arrangements, and increased use of multiple supervisors for each PhD student (Harrison & Grant, Citation2015; McGagh et al., Citation2016; Unda et al., Citation2020). We focus on commerce and management disciplines, as PhD experiences have disciplinary-specific attributes (Barnes et al., Citation2012; Carroll, Citation2016). For example, a report to the Australian Government indicates differences regarding PhD graduates’ perceptions of the quality of supervision for 30 disciplinary fields, with the ranking by Australian commerce and management graduates being below that for 17 other disciplines (McGagh et al., Citation2016). Similar evidence includes commerce and management students’ concerns about pastoral care and tensions arising from performance goals (Khosa et al. Citation2020; Unda et al., Citation2020).

Contribution

Our findings show that PhD students’ self-disclosure about personal problems and feelings in their lives are dependent on supervisors’ responsiveness and quality of support. These are found to be key determinants in fostering students’ relatedness in these relationships. Importantly, we show that while positive interpersonal attributions are associated with positive relational outcomes (such as reciprocity and goal congruence), social penetration is also affected by contextual attributes such as the environment and network, degree of formality, and length of the relationship. We find confined environments accelerate relatedness and disclosure, and that differences are better absorbed in supervisions with a broad reservoir of prior positive experiences. Students in the sub-sample who report relational breakdowns indicate dispositional, interpersonal, and situational differences, together with a lack of prior positive experiences. These students report that their motivation and well-being are affected by contextual attributes (such as clear expectations, timeliness of feedback and supportiveness) as well as supervisor attributes (quality of support, availability and responsiveness). Further, they report that their autonomy, competence, and relatedness are affected by their supervisors’ preference scoping their PhD in terms of their own research interests.

Overall, findings demonstrate that effective communication and positive interpersonal attributions are associated with relatedness and reciprocity in the relationship. These qualities foster students’ autonomy and competency, with positive effects on their motivation and well-being. By identifying the importance of addressing student needs for relatedness, and how this impacts their autonomy and competence, our findings contribute to SDT. In the context of recent research showing the differential effects of SDT’s three psychological needs (e.g. Ntoumanis et al., Citation2021; Wang et al., Citation2019; Ward et al., Citation2021), our findings demonstrate the primary role of relatedness in order for PhD students to achieve autonomy, competence, motivation and emotional well-being. In particular, our use of SPT to ascertain the importance of relatedness enables more nuanced appreciation of this aspect of SDT, and demonstrates the complementarities between SPT and SDT. While PhD supervision may require different approaches for different students and supervisors (related to individuals’ competence, circumstance, personality, and cultural background), valuing relatedness is shown as a key factor affecting PhD students’ motivation and well-being.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. In the next section, we provide background to the study, including an overview of student, supervisor, structural, and relational attributes. We then present the research method, followed by results and discussion of the findings, before presenting our concluding comments.

Background

In Australia, a PhD in a commerce and management discipline normally entails a traditional research-focused qualification, akin to that in the United Kingdom. Typically, these full-time PhD students have a principal and one or more co-supervisors, all with expertise related to the study (Robertson, Citation2017). Use of supervisory teams with more than one supervisor is consistent with legal requirements in Australia (TEQSA, Citation2015), guiding principles in the United Kingdom (UK Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education, Citation2018) and Section 28 of the Swedish Higher Education Ordinance. In this study, we focus on these students’ relationship with their supervisors as they complete their thesis that must be externally examined and demonstrate an appropriate contribution to knowledge (McGagh et al., Citation2016).

This style of PhD places considerable emphasis on students’ motivation, their ability to work autonomously, their sense of well-being in their community, as well as their supervisors’ constructive support and guidance (Manathunga, Citation2012). Evidence of motivational issues for Australian PhD students includes: one Australian review showing that only 42.9% of PhD students agreed or strongly agreed that they felt a sense of relatedness to others in their department (Edwards et al., Citation2011); attrition rates being greater among higher degree students than undergraduate students (Pearson, Citation2012); students reporting psychological stress (Barry et al., Citation2018); and supervisory experiences being poorly rated by Australian commerce and management students (Carroll, Citation2016; McGagh et al., Citation2016). Similarly, supervision arrangements will affect supervisors’ motivation, availability and responsiveness. Influential factors include institutional pressures regarding personal performance criteria (Smith & Urquhart, Citation2018; Steenkamp & Roberts, Citation2020); required adherence to codes of ethics and practice, such as those set by the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA, Citation2015); and university policies, including supervisor accreditation processes and ethics.

For students to achieve the necessary scholarship for completing a PhD, relationships with their supervisors must develop through exchanges of information. In this regard, SPT offers useful perspectives (Altman & Taylor, Citation1973; Carpenter & Greene, Citation2016), as it premises that: advancement of relationships is mainly dependent on the degree and nature of interpersonal rewards and costs; and relationships progress through different stages, including progress and development (or dissolution), either from superficial to close disclosure of information, or from close to superficial disclosure.

The general dimensions of social penetration include breadth, such as the number of topics discussed, and depth as ‘the degree of intimacy that guides these interactions’ (Carpenter & Greene, Citation2016, p. 1). These two SPT dimensions reflect the role of reciprocity in individuals’ interactions, whereby the response to someone’s disclosure affects the ongoing equity in the relationship (Carpenter & Greene, Citation2016). While reciprocity begins with orientation, as individuals cautiously disclose information, depth is increased by sharing a breadth of topics and more intimate information. These processes are not linear as exchanges may initiate conflict and breakdown, although later stages characteristically display openness, breadth, and depth of stable exchanges (Taylor & Altman, Citation1987). In workplace contexts, supervisors’ support is found to mitigate negative consequences from subordinates’ self-disclosure, with positive effects on motivation and well-being (Montani et al., Citation2019).

Given our aim to investigate the relational processes and their effects in PhD student–supervisor relationships, including a focus on the factors affecting students’ motivation and well-being, we consider the interplay of student, structural and supervisor attributes in the supervision panel, together with relational attributes enabling exchanges of information.

Student attributes

As ‘an empirically based approach that also relates directly to the phenomenology of learners and teachers’, SDT offers a framework by which to understand the factors that enable (or inhibit) individuals’ motivation and propensity to learn (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020, p. 8). It is relevant to understanding students’ development as PhD scholars, as the theory posits that an individual’s motivation and well-being are enhanced when their needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are fostered (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020). Autonomy refers to volition that can accompany actions, with these initiated and regulated by an individual rather than being externally controlled (Teixeira et al., Citation2020). This self-direction may be relative (since actions can be characterized in various ways) but emanates from self-fostering of wholehearted behavior (Ryan et al., Citation2006). Competence ‘reflects the desire to extend one’s capacities and skills’ by seeking and dealing with challenges to achieve personal growth and being effective in interactions with others (Teixeira et al., Citation2020, p. 48). Linked with confidence and self-esteem, an individual’s perceived competence or efficacy when engaging with tasks affects their motivation (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020). For example, external or organizational pressures that are unaligned with personal values and interests may negatively affect students’ engagement and satisfaction, particularly when authentic self-expression is affected (Cable et al., Citation2013). The third need, relatedness, involves feeling socially connected and experiencing care and inclusion (Martela et al., Citation2021). Similarly, factors such as whether the educational focus is upon learning or performance are shown to affect fulfillment of students’ needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, and thus their motivation (Rodrigues et al., Citation2020).

Accordingly, given the dual focus of PhD studies (learning and performance), more nuanced understanding is required about the relationship between PhD students’ autonomy, competence and relatedness, and their motivation and well-being. Here there is mixed evidence concerning the relative importance of relatedness (Wang et al., Citation2019). For example, Ward et al. (Citation2021) find that a lack of relatedness and autonomy motivates professional accountants to enroll for a PhD as they believe that they will have more autonomy and find a better fit with a career in academia. Further Wang et al. (Citation2019) report differential effects, including that relatedness significantly affects self-directed motivation more than autonomy and competence, and is negatively related to pressure. Similarly, relatedness positively impacts people’s motivation and level of engagement with peers (Tsai et al., Citation2021; White et al., Citation2021), with individuals’ satisfaction of relatedness being more important in teamwork than satisfying their autonomy and competence (Shen et al., Citation2016). Alternatively, Ntoumanis et al. (Citation2021) in their statistical meta-analysis of the SDT literature, report relatedness as being less significant than competence and autonomy. Similarly, while autonomy and relatedness are shown as significant motivational factors in team scenarios (Goemaere et al., Citation2019), in relationships with less equality (such as leader/subordinate or supervisor/student), the actions of the leader (supervisor) may confound their subordinates’ (students’) needs for autonomy and relatedness (Ryan & Ryan, Citation2019).

Structural attributes

Supportive structures are important for students’ progress (Bastalich, Citation2017; Kiley, Citation2017). Rather than controlling behavior, these structures should provide meaningful choice and foster students’ autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020) through providing clear expectations, consistent guidelines, and quality feedback. For example, quality feedback relates to managing students’ expectations for guidance, while not over-directing them, thereby constraining their autonomy and motivation (Stracke & Kumar, Citation2010). Similarly, feedback should support students’ competence, with positive effects on motivation (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020).

In supervisory arrangements involving multiple supervisors, students must engage with more people as the research environment is established and the research project managed. This presence of more members may affect social penetration processes and self-disclosure, as there is greater willingness to verbally and non-verbally disclose personal information in smaller networks (Solano & Dunnam, Citation1985). Students may feel more vulnerable and constrained in less manageable, larger groups, with subsequent effects on communication (TEQSA, Citation2015). This effect may relate to a discloser's assumption that in smaller networks, information is more protected as it is shared with fewer individuals (Levine & Moreland, Citation2008).

Generally, conflict and disagreement are diminished when those in the relationship better define and value growth, whilst being responsive to each other’s individual identity, including personal strengths and weaknesses (Harrison & Grant, Citation2015). In longer-term relationships, when reservoirs of positive and negative experiences are developed through responsiveness, these relationships may better absorb differences than those with limited shared experiences (Altman & Taylor, Citation1973; Robertson, Citation2017).

Regarding the nature of networks, social penetration processes are likely to proceed more quickly in informal arrangements, rather than in formal ones where individuals feel more constrained by defined roles (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020). Consequently, superficial exchanges may feature more in formal networks, with intimate communication being more typical in informal arrangements (Utz, Citation2015). Supervisors may variously regard appropriate levels of formality (Khosa et al., Citation2020). This partly arises from their formal roles related to students’ achieving PhD milestones, and partly from supervisors’ personal preferences deriving from relationships with colleagues, students, and prior supervision experience (Robertson, Citation2017). The extent of formality may be affected by supervisors’ preferences, with consequent impact upon reciprocity in student–supervisor relationships and thus students’ autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

Equally important are the frequency and type of contact between the student and their supervisors (Gill & Burnard, Citation2008). For example, studies report negative relational effects in isolated and/or physically confined groups (Fernandez-Rio et al., Citation2021) and those lacking structured, regular meetings (Gill & Burnard, Citation2008). Physical factors such as the choice of meeting room, furniture layout, or adjustment of lighting may similarly affect relatedness (Town & Harvey, Citation1981). Moreover, computer-mediated communication, now frequently used by students and supervisors, presents a new dimension that differs from past practices of face-to-face meetings (i.e. Hutchings, Citation2017).

Supervisor attributes

In progressing their students’ studies, supervisors’ duties include support and guidance (McCallin & Nayar, Citation2012) to ensure students’ intellectual progress, managing the quality and timeliness of their PhD (Bastalich, Citation2017), and providing pastoral care to support their well-being (Roach et al., Citation2019). In this regard, SPT offers perspectives through its focus on how exchanges of information affect the progress of relationships (Altman & Taylor, Citation1973; Carpenter & Greene, Citation2016). Specifically, as they guide and challenge, supervisors’ attributes may profoundly impact their social and scholarly relatedness with students. While their roles may vary between a collaborative relationship or mentoring role (Revelo & Loui, Citation2016; Robertson, Citation2017), constant factors include their availability and responsiveness, constructive guidance, quality of support and prior experience (Harrison & Grant, Citation2015; Roach et al., Citation2019).

Regarding supervisors’ support, clear expectations and goals, together with constituent guidelines, are important so that students have the support by which to manage their PhD studies (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020). In this regard, supervisors’ experience with prior and current students, as well as their own studentship, may influence their behavior (Lee, Citation2008), including the degree of formality or informality in the relationship (Hemer, Citation2012).

Equally, supervisors’ responsiveness and availability may be affected by external institutional pressures (Steenkamp & Roberts, Citation2020), and internal pressures arising from interactions in the supervision team (Hamilton & Carson, Citation2015). Together these supervisor attributes impact students’ autonomy, competency and relational needs, and their motivation (Manathunga, Citation2012).

Relational attributes

Two relational attributes concerned with exchanging information affect the relational outcomes between students and supervisors. These are the quality of communication and contributory behavioral influences (dispositional, interpersonal, and situational).

Communication qualities

Successful student–supervisor relational outcomes are typically associated with participative leadership styles that provide students with greater opportunities and foster relatedness through effectual communication (Ryan & Ryan, Citation2019; Sparks et al., Citation2016). Regular and timely communication, such as regularly scheduled meetings, are important (Khosa et al., Citation2020), as is feedback that focuses on progressing students’ competency and autonomy rather than demonstrating superior knowledge (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020). While relevant and critical information is vital, clear delivery in a supportive manner enhances motivation. Equally, clarity regarding student and supervisor roles is important for solving the inherent challenges (Manathunga, Citation2012).

Thus, communication qualities affecting relational outcomes for students and supervisors include clear understanding of each individual’s accountability (i.e. timelines and milestones) through efficaciously identifying roles, setting goals, scheduling meetings, and clarifying supervisors’ availability (Boehe, Citation2016; Lee, Citation2008).

Contributory behavioral influences

Attribution theory posits that individuals’ thinking and behavior are influenced by how they interpret the behaviors of others with whom they are interacting (Carson, Citation2019). In particular, individuals’ motivation and emotional well-being are enhanced through discourse that is perceived as demonstrating how they are closely connected to or cared for by others (Greene et al., Citation2006). In appreciating how mutual understanding and bonding develop between individuals in a relationship (Carson, Citation2019), three contributory behavioral influences differently affect how individuals interpret and respond to another’s emotional cues. Specifically: (a) dispositional attributions arise when the sender’s personality or shared interests affect how recipients judge disclosures; (b) interpersonal attributions, when recipients relate disclosures to a close relationship with the discloser; and (c) situational attributions, when recipients relate disclosures to shared circumstances (Jiang et al., Citation2011).

In developing a relationship with their supervisors, students’ perceptions of relatedness may be affected by dispositional attributes such as supervisors’ responsiveness (Trepte & Reinecke, Citation2013), and the formality with which supervisors execute their role. This includes the extent to which the relationship is supportive, with this evident in aspects such as clear, effective, regular, and timely feedback. Alternatively, positive interpersonal attributes, related to a close and respectful relationship between the sender and receiver, may encourage trust (Jones & Davis, Citation1965). By enhancing trust and valuing exchanges of viewpoints, positive interpersonal attributions foster closeness, goal congruence, and shared knowledge (Jiang et al., Citation2011). Equally, students’ disclosures may be affected by situational attributes such as supervisors’ availability, and sharing of knowledge (in joint conference presentations and/or publications).

However, since disclosures may be inhibited by a recipient’s belief that the discloser reveals sensitive information to others who are less trusted (Greene et al., Citation2006), recipients may prefer those who disclose only to individuals perceived as part of a close relationship. While disclosure of serious misdemeanors may cause rejection (Omarzu, Citation2000), disclosure of weaknesses to which the receiver can relate may generate greater liking (Greene et al., Citation2006). In this regard, there is limited research about the effects of dispositional, situational, and interpersonal attributions on leader–subordinate relationships (Carson, Citation2019; Gardner et al., Citation2019) and how relatedness and trust are predicated upon the perception that sensitive information is respectfully treated by others in a close relationship.

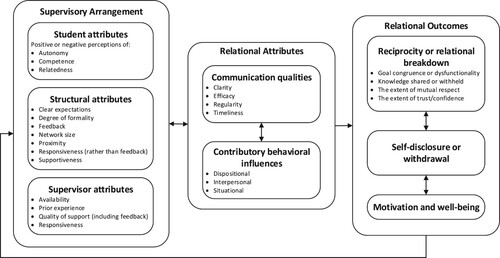

In summary, the mutually reinforcing relational attributes of communication and contributory behavioral influences should affect students’ reciprocity, self-disclosure, and motivation. As depicted in , given our research aims to explore how relatedness affects PhD students’ motivation and well-being, we theorize that the defining attributes related to the supervisory arrangement (student and structural and supervisor attributes), together with these relational attributes, will convey a co-constructed perspective of relational outcomes for PhD students (i.e. reciprocity or relational breakdowns, self-disclosure or withdrawal, and motivation and well-being).

Research method

We use interviews to qualitatively investigate these relationships between students and their supervisors (Cassell & Symon, Citation2004), as this method is shown to generate the required depth and detail regarding subtleties in these relational processes and their effect upon students’ motivation and well-being (Stokes & Bergin, Citation2006). First, when little is known about the phenomenon, a qualitative approach, such as interviews, is likely to provide richer descriptions than quantitative methods such as surveys (Edmondson & McManus, Citation2007). Second, open-ended data are useful when knowledge on a particular topic is seemingly contradictory (Lei et al., Citation2019). In this regard, one body of literature suggests that a close working relationship in student‒supervisor networks may help avert power differentials, resulting in a more positive relationship (e.g. Hemer, Citation2012; Howells et al., Citation2017): alternatively other studies warn about the dangers of blurring professional boundaries (e.g. Halse & Malfroy, Citation2010; Lee, Citation2008).

Our interview protocols, comprising a mix of semi-structured and open-ended questions, were framed to align with our theorized model (see ). These protocols focused on five themes drawn from our review of the literature (see the previous section), with key sources summarized in below. Pilot testing for clarity and appropriateness resulted in some refinements. The final protocols and relationship between the questions and our theorized model are reported in the Appendix.

Table 1. Derivation of the interview questions.

Participants were recruited using a non-probability sampling approach (Flick, Citation2018), involving a combination of quota and purposive sampling (Fox, Citation2018; Robinson, Citation2014), enabled through conference attendance and/or personal email contacts and referrals.Footnote3 In total, 37 interviews were conducted with an unmatched sample of 27 PhD students and 10 supervisors from supervision panels at nine Australian universities (located in four Australian states), and three New Zealand universities (see and ).Footnote4

Table 2. Student demographics.

Table 3. Supervisor demographics.

The quota of student participants is based on achieving a balance in gender; enrollment status (full-time or part-time); first language (English or other); and stage of PhD study (confirmation of proposal, mid-candidature review, pre-submission or submission of thesis). All had two or more supervisors and were studying a PhD in management and commerce, although for three students, their PhD was interdisciplinary. Further, six students who experienced a change in supervision arrangements, were purposively selected to explore insights into relationship breakdowns. Regarding supervisors, more senior academics (professor or associate professor) with experience in supervising a number of PhD students to completion were selected. While this approach was influenced by the researchers’ backgrounds, location, and connections, care was taken to avoid conflicts of interest or bias by adhering to protocols during the interviews and exercising care in coding the findings (Robinson, Citation2014).

Interviews typically lasted between 45 and 60 minutes and followed the respective protocols, with two researchers being present to avoid bias. Each was recorded and transcribed, with one researcher comparing the transcript with the digital recording. Initial coding was conducted after 30 interviews.Footnote5 Then, as subsequent analysis of the additional seven interviews showed little new information, theoretical saturation appeared evident and data collection stopped after 37 interviews (Guest et al., Citation2006).

There were four stages in our analysis of the data. For Stages One to Three, in accord with the approach used by Hobson and Maxwell (Citation2017), one researcher coded all transcripts using NVivo 11 software, while the second researcher independently coded approximately half. This elicited different perspectives (Braun et al., Citation2019), with anomalies between the researchers’ coding re-examined to explore differences. During the first stage, each sentence was coded to understand meaning in the data (Tracy, Citation2013). For example, the response ‘I think it makes the relationship more comfortable because these are the kind of things that friends tell each other’, was coded ‘friendly relationship’. In Stage Two, these codes were grouped into larger concepts. For example, codes such as ‘friendly relationship’, ‘care’, and ‘family’ were grouped under ‘relatedness’. Then, to conceptualize themes, related codes were grouped under a hierarchical umbrella. For example, higher-level codes such as ‘autonomy’, ‘relatedness’, and ‘competence’ were selected, and statements grouped to enable understanding of the extent to which participants highlighted that these needs were being met in a manner that supported or inhibited motivation and well-being. In Stage Three, statements judged as establishing connections between relatedness, self-disclosure, and reciprocity in these relationships, and PhD students’ motivation and well-being, were categorized into five themes that aligned with the structure of the interview questions (see and the Appendix):

self-disclosure (dispositional, interpersonal or situational attributions) related to the discloser’s personality, situational factors, or a close relationship;

relational outcomes including reciprocity and power structures;

environmental contexts such as physical and social contexts, and network size;

students’ motivation and well-being related to communication and evident needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness; and

conflict, including reservoirs of rewards and costs in the relationship’s history, and power structures.

Findings related to these five themes provide provisional support for our theorized model (see ). Accordingly, in Stage Four we re-examined the data to identify:

student, structural and supervisor attributes;

relational attributes (communication and contributory behavioral influences); and

relational outcomes (reciprocity or relational breakdown, self-disclosure, and motivation and well-being).

Details regarding the coding in Stage Four is provided in the Appendix. While some subjectivity is unavoidable (Edmondson & McManus, Citation2007) and bias remains a potential limitation, after discussing differences, intercoder agreement was >90%. We report our results based upon this analysis.

Results

Participant details

Each student had two or three supervisors, whilst each supervisor was supervising a PhD student with one or two other supervisors.

Of the 27 students, 55.6% are female and 44.4% male (see ). Their disciplinary fields are accounting and finance (59.3%), management (18.5%), marketing (7.4%), business law (3.7%) and interdisciplinary studies (11.1%). More than half (55.6%) are studying full-time, with English as the first language for only 44.4%.

Of the 10 supervisors, 60% are professors, with English as their first language for 60%, and 80% being in the discipline of accounting and finance (see ).

Reporting of our findings is structured in terms of student, structural, and supervisor attributes for the supervisory arrangement (see ). Where reference is made to particular students and supervisors, their illustrative comments are provided in the table relevant to that section.

Student attributes

Students perceived that the quality of supervisors’ communication (clarity, efficacy, regularity, and timeliness) impacted their autonomy, competence, and relatedness, as well as their motivation and well-being (see below for specific statements by identified participants).

Table 4. Students’ attributes.

Students see positive effects on their motivation and emotional well-being from opportunities to act autonomously (e.g. freedom to shape their research project, exercise project management skills, increase decision-making, and reduce the degree of supervisors’ control). Thus, for Student O, an increase in opportunities for input and an open approach from the supervisor alleviated power differentials and resulted in a more comfortable relationship. Alternatively, restrictions such as reduced decision-making power about the research topic, reduced opportunity for comment, and devaluing of their views, are perceived as detrimentally affecting their autonomy and well-being (e.g. Student G). Most supervisors perceive their role as supporting the student’s autonomy, with developing their independent thinking described as a key to their well-being (e.g. Supervisor I).

Regarding competence, students reported a range of issues arising from supervisors’ support for research skills, knowledge of the relevant literature, data analysis, writing, and time management (e.g. Student H). Overall, students indicate that perceptions of increased competence have a positive impact on their motivation and well-being (e.g. Student N and Student K) with supervisors’ encouragement playing a key role (e.g. Supervisor A).

The relatedness that arises from closeness, which is typically expressed as a special bond beyond the formal relationship, appears to be cultivated through care and trust (e.g. Student H). Alternatively, students’ perception of supervisors’ lack of care or genuine interest in their well-being negatively affects relatedness (e.g. Student A). Thus, while some viewed supervisory arrangements as strictly work-related (e.g. Student P and Supervisor F), most students valued the presence of social connections with supervisors. As such, relatedness is an important factor. Evidence of negative effects of relatedness upon students’ motivation and emotional well-being include Student G crying when her autonomy was discounted; Student H’s silence when her competency was harshly challenged; and Student N’s inability to sleep before relatedness was developed in the supervision team.

Structural (or contextual) attributes

Structural attributes are found to concern contextual factors related to the human element of supervision. These include clear expectations, degree of formality, feedback, network size, proximity, responsiveness, and supportiveness (see below for specific statements by identified participants).

Table 5. Structural (or contextual) attributes.

Clear expectations. Whilst both parties understand the importance of clear expectations, students and supervisors report how closer interpersonal relationships provide opportunities to adapt expectations to changing circumstances. Students report ambiguity as a cause of anxiety, whilst supervisors’ clear expectations support positivity and well-being (e.g. Student Q and Student I). Supervisor H describes how setting clear expectations and goals are critical for timely PhD completion. When negotiated, clear expectations positively enhanced students’ motivation and well-being (see Student Q), and improved Student I’s well-being.

Degree of formality. Students (e.g. Student M) and supervisors report how positive and informal social contexts foster positive interpersonal attributions, awareness of individuality, self-disclosure, relatedness, and thus reciprocity, motivation and well-being. While most students report a gradual reduction in formality as relationships progress, in some panels, high levels of formality are retained, and perceived as impeding relatedness with supervisors (e.g. Student G).

As cultural differences arise from prior experiences, students with prior educational experience outside the study’s context of Australia and New Zealand, may face some difficulties adjusting to Western academia (Cho et al., Citation2008; Son & Park, Citation2014). Since English is the spoken and written language in these panels, but not the first language for 55.6% of student participants, we investigate the effects of culture on relationship dynamics.

Some students, from a predominantly Asian background (see ), perceive that their supervisors have authority and status, and expressed some hesitancy in interacting with them. For example, Student F views his supervisor as a figure of authority and ‘felt bad’ when seeing him without seeking prior approval. Similarly, Supervisor B reports how cultural differences hamper students’ ability to express their views openly, which influences the formality/informality in these relationships. In general, findings show that despite being accustomed to more formal relationships, these students socialized with their supervisors and engaged with their wider academic community. Supervisors had an important role in fostering relatedness and reciprocity.

Feedback. Supporting students’ autonomy while providing critical feedback appears to be a key consideration (e.g. Student R). As feedback is central to the PhD journey, its effects are most evident when students perceive that feedback indicates their incapacity to meet their supervisors’ expectations. In part, difficulties in receiving (negative) feedback relate to the supervisor’s personal communication style (e.g. Student D).

A similar cause of dissatisfaction is a supervisor’s inability to provide timely feedback. Student T experienced the lowest point in her PhD when lack of timely feedback meant that she had to reconceptualize and rewrite her PhD proposal. In contrast, a number of supervisors stressed the importance of presenting a common perspective in feedback (e.g. Supervisor H), despite exposure to a range of views being one purpose for supervision panels. Feedback negatively impacted students’ motivation and well-being (see Student G), when it was harsh and challenged their feelings of competency (see Student D).

Network size. Team dynamics affect student well-being and outcomes (e.g. Student V). In general, there is agreement that levels of self-disclosure are enhanced by having fewer people in student–supervisory meetings, with the quality of the relationship between members being a significant limiting factor. Student E (see ) provides evidence of more wariness in meetings. In this regard, reduced levels of self-disclosure seemingly attributable to supervision dynamics, particularly between primary and secondary supervisors. Students expect the secondary supervisor to be more assertive and present an independent view (e.g. Student A). Supervisors who favor open dialogue and closer relationships saw fewer benefits in panel supervision: Supervisor C sees some benefits from multiple supervisors to fulfill specific skill gaps but prefers to work with the student on a one-on-one basis.

Proximity. The physical context of a confined environment seemingly contributes to accelerated disclosure by generating closer social patterns of personal exchanges. Student M explains how being in the same car (confined environment) with his supervisor led to accelerated self-disclosure, which helped reciprocity. Similarly, as a result of attending a conference together, Student J experienced a closer connection with her supervisor that reinforced her well-being. Many supervisors are comfortable with close proximity (examples include conference travel and inviting their students to home for lunch or dinner), viewing this as a relationship-building exercise (e.g. Supervisor G). Due to busy schedules, others prefer to limit their association to a strictly formal setting.

Similarly, by restricting opportunities for physical closeness, electronic communication affects students’ perceptions of their progress and relationships with their supervisors. Students repeatedly report how critical feedback given via email is harder to take constructively (with more negative effects) than feedback received via face-to-face meetings (e.g. Student K). Students reported receipt of critical feedback as having an important influence on autonomy, competence, and thus their motivation and well-being.

In particular, proximity is a key influence upon relatedness and linked to students’ sense of well-being (see Student J). Some supervisors were aware and deliberately encouraged closer contact (see Supervisor G). Student L reports a lack of proximity as being detrimental to developing relatedness and well-being. She was completing her thesis by long distance supervision and had come to ‘not expect them [supervisors] to help me emotionally’.

Responsiveness and supportiveness. In general, students link open dialogue with supervisors to positive impacts on their motivation, as it encourages self-disclosure and awareness of their individuality (e.g. Student E). Supervisors favoring informal, closer relationships highlight how open dialogue improves knowledge of students’ personal issues that may affect their PhD progress (e.g. Supervisor C). Similarly, students who regard their supervisors as overly formal and authoritative, report increased anxiety, prefer to solve their own problems, experience difficulties with relatedness, and avoid meetings (Student A).

The three students pursuing interdisciplinary research reported problems with ambiguity, which arose from a lack of an established approach for their research. As a result, they desired more supervisor support and directional guidance, including closer relationships. Interestingly, because of the uniqueness of their research topics, these students identified a lack of peer support, with Student B’s comment that he lacks ‘anyone to turn to’, emphasizing the importance of the relationship with a supervisor. Student C was appreciative of her supervisor’s support in defending her work when it was criticized by another academic.

Supervisor attributes

In presenting our findings related to supervisor attributes, we provide participants’ supportive statements in . Supervisors’ availability was an issue, being more evident in the early stages of students’ PhD studies (e.g. Student U and Supervisor C). Two supervisors saw the importance of being available to their student and would prefer more social interactions, but are more transactional because of their workload (e.g. Supervisor A). Alternatively, Student U felt isolated, with supervisors’ unavailability affecting her motivation and well-being.

Table 6. Supervisors’ attributes.

Prior experience did affect the type of supervisors’ support. Supervisor G, who felt isolated during his PhD, draws on this experience to create a sense of relatedness by developing close relationships and social interactions with his students. Supervisor E, based upon prior successful experiences with PhD students, phrased his requests inclusively using words such as ‘our deadline’ to motivate his current student to complete PhD milestones. Students acknowledged the important effects of supervisor attributes on their well-being i.e. Student O’s selection of a new supervisor, based on communication qualities and a gentler nature, reflected her prior experience.

Regarding quality of support, supervisors favoring close relationships with their students are comfortable in providing support and counsel and addressing students’ personal issues. Supervisor H provided one example, namely ‘send[ing] them an email if you haven’t heard from them for a few days, so I suppose you just check in on them’. However, others perceive their role as limited to academic support (e.g. Supervisor F). In general, students appreciate supervisors’ supportive efforts (e.g. Student B). With respect to critical feedback as part of support, supervisors’ views vary significantly. Some show awareness of the potential negative impact of critical feedback on student well-being (e.g. Supervisor C), whereas others advocate that dealing with harsh feedback is part of academic scholarship (e.g. Supervisor D). Students’ views on critical feedback are discussed in the previous section under structural (or contextual) attributes.

Although reasons varied, half the supervisors said that they were responsive and supportive, favoring close relationships with their students. Some argue that informal close relationships alleviate inherent power differentials, allowing students to be more forthcoming (e.g. Supervisor B), which enhances mutual understanding (Supervisor C). Many students agree that their supervisors’ responsive and supportive approach encourages them to seek advice on issues that may appear personal but are likely to impact their PhD progress. This positively affected their well-being (e.g. Student E). Alternatively, one PhD supervisor from business law (Supervisor D) exercises a cautious approach, perceiving supervision meetings as ‘a formal part of the job’.

Together, supervisor attributes that encouraged relatedness, fostered motivation and well-being.

Relational attributes

The mutually reinforcing relational attributes of communication qualities and contributory behavioral influences, are found to affect students’ relational outcomes associated with their PhD supervision (see below for specific statements by identified participants).

Table 7. Relational attributes.

Communication qualities

Communication that is regular, clear, timely, and pertinent, positively affects students’ motivation (e.g. Student I). Students acknowledged that a lack of timely communication has negative effects on their well-being (e.g. Student T), as does a lack of clear expectations (e.g. Student A). Similarly, the tone of communication and body language can have negative effects (e.g. Student H). Most supervisors understand the importance of regular communication and implement strategies to achieve this (e.g. Supervisor H). Supervisor F illustrated how a former student failed to keep regular contact, such that her lack of progress led to her withdrawal from the program.

Contributory behavioral influences

Analysis shows that many students disclose personal information (unrelated to their studies) to their supervisors. Of the three forms (see ), interpersonal attributions are shown as the most important, in that: (1) students like supervisors who disclose only to them (e.g. Student M); (2) at the affective level, this leads to closeness and trust in these smaller networks, making it easier for the student to disclose more (e.g. Student Q); and (3) students view a closer student‒supervisor relationship as a long-term research partnership and lifelong friendship (e.g. Student B). This too is valued by a number of supervisors.

There is considerable evidence linking successful interpersonal attributions to students’ desire to establishing relatedness, managing their supervisors’ expectations and enhancing their sense of well-being (Students B and Student Q). Outcomes include closeness, long-term research partnerships, reciprocity and ease of further self-disclosure. Conversely, in more formal relationships, situational attributions are more task-oriented.

In one case, when circumstances led the student (Student N) to disclose very personal information to her supervisor, the effects on the student’s well-being were such that their relationship remained task-oriented and somewhat superficial. In this case, the information was shared as the situation demanded disclosure (rather than due to willingness to trust the other party), thus highlighting how situational attributions may limit relatedness. Dispositional attributions include supervisors’ displays of authority in a manner affecting students’ relatedness, particularly when these communications are perceived as unnecessary and/or unfair (e.g. Student I). Negative dispositional attributions also related to issues such as students’ other activities. For example, when Student I accepted work as a research assistant, she was concerned about her supervisor’s resentment, which was based upon the supervisor’s argument that it would affect her competence and autonomy. In fact, as a result of dispositional attributes, some students restrict communication with supervisors. For example, Student K chose not to disclose her love affair to a supervisor whom she perceived to hold traditional family values.

Twelve students had problems in building a sense of relatedness. Causes include the personal style of the supervisor or student, lack of reciprocity, lack of trust, a strong sense of personal–professional boundaries, and overt power differentials. As described by Student G, this lack of relatedness appears to have long-term effects, including ‘when my [PhD] is over, I’ll be gone, and I’ll forget her [supervisor]’.

In summary, we find evidence that students tailor their disclosures to manage relatedness and minimize negative effects on their well-being. Similarly, while supervisors’ responses indicate some awareness of students’ needs and the value they place on open communication, students’ responses indicate some reactions to supervisors’ adherence to formal procedures that may be explained by disciplinary or personality differences.

Relational outcomes

Regarding relational outcomes, greater reservoirs of rewards and costs accrue to students and supervisors who disclose more to each other and are socially involved (see below for specific statements by identified participants). This reciprocity appears to engender more awareness of individuality, trust, and better resolution of differences than between those whose relationship is ‘merely professional’. As a result, in these relationships where reciprocity is more evident, superficial disagreements have demonstrably less effect (e.g. Supervisor G), with successful relational outcomes benefiting both parties (e.g. Supervisor E).

Table 8. Relational outcomes.

Consistent with students’ views (see Relational Attributes section), some supervisors nurture these relationships with a view to acquiring long-term benefits, such as co-authorship opportunities (e.g. Supervisor E). However, closeness demonstrably depends on the supervisor’s responsiveness, because without reciprocity, students stop sharing information (e.g. Student G and Student A). Besides perceiving enhanced relatedness, students value reciprocity and mutual respect from close supervisory relationships as this enhances their sense of well-being (e.g. Student S).

However, for the six students who experienced a change in supervision arrangements (see below), the relationship breakdown (and its negative effects on their motivation and well-being) was such that they each negotiated permanent changes of their main supervisor. They were mature, part-time domestic students, aged between 36 and 51 years. These relationships dissolved within the first 12 months of candidature (full-time equivalent), when there was insufficient time to build a reservoir of rewards. Four of these students reported issues with supervisors directing them to their area of research interest rather than allowing their own i.e. inhibiting students’ autonomy and competence (e.g. Student O). Another cause was supervisors’ lack of reciprocity and interest, which students perceived as impacting their motivation and well-being (e.g. Student H and Student L). Interestingly, three students reported that the passive role played by the secondary supervisor contributed to their decision to alter supervision arrangements. Other students, who had lesser changes in supervision, reported similar issues, such as lack of mutual respect (e.g. Student O).

Table 9. Factors contributing to a relational breakdown.

While we lack correlated responses from the supervisors of these students, our participating supervisors offered alternative perspectives about relationship breakdowns (see ), identifying the student’s lack of progress or effort as a leading cause (e.g. Supervisor F). Consistent with students’ views, supervisors largely attributed negatives to communication qualities, such as students’ lack of communication (e.g. Supervisor E), the lack of response to feedback (e.g. Supervisor I), and lack of understanding about the rationale for the required supervision changes. As explained by Supervisor D, while poor communication and supervisor attributes contributed to negative relational outcomes, students have avenues of recourse since:

There are plenty of ways in which PhD students can wage complaints and generally kick up a fuss. And if something did go wrong of course, you could resolve it fairly easily by simply saying, ‘it's not working’. And you need another supervisor … So, the power differential in my judgment is not very large because there are all these avenues of recourse and so on.

As all students experiencing relationship breakdowns with their supervisors are domestic students, international students’ relational outcomes may arguably reflect more acceptance of supervisor and structural attributes (see Cho et al., Citation2008). Factors may include international students being more vulnerably positioned, having left their home environment, and thereby losing the support networks available to domestic students (Sherry et al., Citation2010; Wang & Li, Citation2008). Moreover, with scholarships and enrollments linked to visa conditions (Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Citation2021), international students may be more cautious about changing their supervisory arrangements, as this may involve changing universities, location, and/or visa arrangements. Interestingly, some did perceive some supervision tensions as immutable, which has implications for how universities structure their processes for international PhD students (in this regard, visa conditions may be beyond universities’ control). One full-time international student, who was unwilling to change supervisors because she feared possible disruption and perceived a lack of wider university support, explained:

I would have to change universities, start all over again … the student is powerless. If a student would want to change their supervisors, it should be more approachable, and there shouldn't be barriers. The department should do more asking students, what's wrong? (Student T)

Discussion

In discussing the theoretical and practical implications of these findings, we particularly explore the factors affecting students’ motivation and well-being. Here, findings showing the impact of relatedness on students’ motivation and well-being are timely, given evidence of psychological distress affecting PhD students (Barry et al., Citation2018; Johansson & Yerrabati, Citation2017; Khosa et al., Citation2020). In this regard, we review our initial conceptualized model, with a particular focus on implications of findings showing the importance of relatedness and relational attributes.

Review of the conceptualized model of student–supervisor PhD relationships

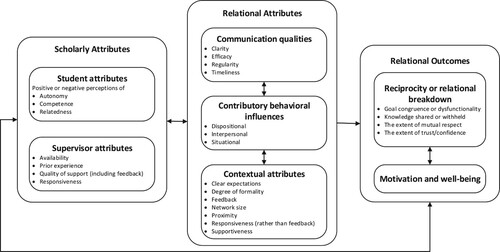

Our initial model conceptualized the structure of student–supervisor PhD relationships with three key components: the supervisory arrangement, the relational attributes and relational outcomes (see ).

Regarding conceptualization of the Supervisory Arrangement:

Student attributes – students’ self-disclosure is shown to foster relatedness and thereby enhance autonomy and competence, with motivation and well-being being a function of satisfying their relational needs. This extends prior research about the effect of relatedness upon motivation and well-being (i.e. Ward et al., Citation2021; White et al., Citation2021) to the context of PhD supervision, and articulates the impact of the supervisor attributes on students’ needs (Ryan & Ryan, Citation2019).

Structural attributes – the relational aspects of supervision structures are shown as more important than physical attributes (such as meeting schedules). The importance of proximity relates to how closeness generates more shared information and interpersonal attributions. Again, the underpinning effects relate to the human element, such as personal contact, network supportiveness, responsiveness, and clear expectations – all of which affect student motivation and well-being (Gill & Burnard, Citation2008). Accordingly, we extend relational attributes in the model to include a new component, contextual attributes, with proximity included as one aspect. This new component reflects the influence of feedback, degree of formality, supportiveness, and shared knowledge generated by closeness (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020).

Supervisor attributes – findings demonstrate the relevance of all the conceptualized supervisor attributes, particularly upon relatedness.

Regarding Relational Attributes:

Communication qualities – Communication that lacks timeliness, regularity and efficacy is identified as a significant factor in relational breakdowns. Alternatively, supervisors’ responsiveness and quality of support have positive effects on relatedness – and hence students’ motivation and well-being. Influential characteristics include clear expectations (Boehe, Citation2016; Manathunga, Citation2012), as well as regular feedback in a manner that supports students’ competence and motivation (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020).

Contributory behavioral influences – Situationally, students associated physical closeness and their own accelerated disclosure with supervisors’ sharing of knowledge and supervisors’ more informal supervision styles. When supervisors are unreceptive, reciprocity was limited, with students ceasing or minimizing disclosures, thereby accepting superficial relationships. Interpersonal attributions are important for fostering mutual respect, reciprocity and relatedness. They are associated with clear expectations (Boehe, Citation2016; Manathunga, Citation2012), participative leadership styles (Sparks et al., Citation2016), and sharing of knowledge (Jiang et al., Citation2011).

Regarding Relational Outcomes:

Reciprocity or relational breakdown is shown as contingent upon factors identified in the conceptualized model.

Self-disclosure or withdrawal, together with awareness of individuality, is repositioned as an aspect of reciprocity, to reflect the influence of interpersonal attributions. Of interest is that self-disclosures by non-Western students closely mirror how their Western counterparts share non-task-related information with their supervisors. This evidence of students’ socialization through self-disclosure extends literature regarding language and cultural adaptions of Asian students to Western learning environments (Son & Park, Citation2014). In particular, these students’ difficulties with a new environment that encourages oppositional discourse (Cho et al., Citation2008), are shown to be moderated by supervisors’ encouragement of relatedness and reciprocity. Thus, findings extend the range of motivational factors identified by Zhou (Citation2015) to include supervisors’ responsiveness.

Motivation and well-being remain a key component of relational outcomes for students, and are enhanced through relatedness with supervisors (see specific discussion in subsections related to ). The extent of reciprocity and relatedness, as well as supervisor attributes, affect their motivation and well-being.

Accordingly, in revising our initial model, we reposition the relational effect of contextual attributes as part of Relational Attributes. Further, Supervisory Arrangement, as a component of the original model, is reconfigured as Scholarly Attributes in order to focus on student and supervisor attributes. In this manner, the revised model depicts how Relational Attributes and Relational Outcomes jointly, and subsequently, affect the Scholarly Attributes of students and supervisors (and students as future scholars). Thus, this revised model (see below) extends perspectives on PhD supervision to incorporate the important contribution of relatedness to co-construction of PhD students’ relational identities within their scholarly community.

Theoretical and practical implications

Theoretically, our findings provide new insights regarding SDT as a framework for understanding tertiary educational outcomes (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020). Our contribution relates to the demonstrated importance of addressing PhD students’ needs for relatedness in their engagement with supervisors, and how this impacts their autonomy, competence, motivation and well-being. In particular, use of SPT facilitates this understanding about the role of relatedness, by showing how the breadth and depth of positive disclosures are primarily related to interpersonal attributions.

Besides demonstrating the complementarities between SPT and SDT, findings provide more nuanced understanding of the differential and interconnected nature of SDT’s three psychological needs, autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020). Of these needs, the demonstrated importance of relatedness may reflect our PhD supervision context, in which students’ inherent motivation and propensity to learn are more developed (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020).

In practice, although PhD supervision requires different approaches that are related to individuals’ competence, circumstance, personality, and cultural background, sensitivity to relatedness seems to be a key factor for students’ motivation and well-being. As such, our study provides insights for PhD supervisors regarding the importance of relational attributes and relatedness for fostering students’ motivation and well-being.

Conclusion

Our study investigates the relational processes and their effects in PhD student–supervisor relationships, with a particular focus on the factors affecting students’ motivation and well-being in supervision panels where students have multiple supervisors. This is important, as while research shows influences affecting subordinates’ behavior in workplace scenarios (Hofmans et al., Citation2019), research into PhD supervision primarily focuses on dyadic supervision arrangements (Harrison & Grant, Citation2015).

Our qualitative investigation of students’ relatedness in these PhD supervision arrangements shows how relationship patterns emerge as a result of attributions and reciprocity, with importance attributed to internally focused exchanges. Further, findings show that students’ self-disclosure fosters relatedness and enhances their autonomy and competence, with their motivation and well-being being a function of their relational needs being satisfied. Such findings are timely given the issues identified with PhD students’ motivation and well-being (Barry et al., Citation2018; Johansson & Yerrabati, Citation2017; Khosa et al., Citation2020). Our use of SPT to ascertain the role of relatedness enables more nuanced appreciation of this aspect of SDT, and demonstrates the complementarities between SPT and SDT. As such, by demonstrating the importance of relatedness for PhD students’ autonomy, competence, motivation and emotional well-being, findings contribute to recent research showing the differential effects of SDT’s three psychological needs (e.g. Ntoumanis et al., Citation2021; Wang et al., Citation2019; Ward et al., Citation2021).

A number of limitations constrain the generalizability of our findings. First, our context is limited to commerce and management PhD students and supervisors in Australian and New Zealand universities. Second, in our investigation of students’ engagement with multiple supervisors, our focus is one form of PhD supervision (i.e. panel supervision). Third, our findings are not correlated by matching our sample of supervisors and students. Fourth, some bias may derive from the sampling and data analysis methods. Such scenarios create opportunities for future research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 We use ‘closeness’ to reflect a characteristic in the student–supervisor relationship that some earlier studies term ‘intimacy’. Closeness refers to an extent beyond a professional relationship that includes an interpersonal relationship wherein the student perceives the supervisor as a friend. Its features include self-disclosure, sharing of interests, clear support and clearly valuing the relationship rather than a romantic facet associated with intimacy (i.e. Cozby, Citation1972; Jiang et al., Citation2011; Joinson & Paine, Citation2007; Parks & Floyd, Citation1996).

2 Attributions are more fully explained in the section Contributory behavioral influences.

3 Accounting and Finance Association of Australia and New Zealand (AFAANZ) conference.

4 Students and supervisors were not required to be part of the same supervision panel to participate in the study.

5 Informal norms regarding the number of interviews in leading accounting journals indicate that 25–30 interviews are adequate (Dai et al., Citation2019).

References

- Altman, I., & Taylor, D. A. (1973). Social penetration: The development of interpersonal relationships. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

- Bandura, R. P., & Lyons, P. (2012). Instructor care and consideration toward students—What accounting students report: A research note. Accounting Education, 21(5), 515–527. doi:10.1080/09639284.2011.602511

- Barnes, B. J., Williams, E. A., & Stassen, M. L. A. (2012). Dissecting doctoral advising: A comparison of students’ experiences across disciplines. Journal of Further & Higher Education, 36(3), 309–331. doi:10.1080/0309877X.2011.614933

- Barry, K. M., Woods, M., Warnecke, E., Stirling, C., & Martin, A. (2018). Psychological health of doctoral candidates, study-related challenges and perceived performance. Higher Education Research & Development, 37(3), 468–483. doi:10.1080/07294360.2018.1425979

- Bastalich, W. (2017). Content and context in knowledge production: A critical review of PhD supervision literature. Studies in Higher Education, 42(7), 1145–1157. doi:10.1080/03075079.2015.1079702

- Boehe, D. M. (2016). Supervisory styles: A contingency framework. Studies in Higher Education, 41(3), 399–414. doi:10.1080/03075079.2014.927853

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Hayfield, N. (2019). ‘A starting point for your journey, not a map’: Nikki Hayfield in conversation with Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke about thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 19(2), 424–445. doi:10.1080/14780887.2019.1670765

- Brooks, R. L., & Heiland, D. (2007). Accountability, assessment and PhD education: Recommendations for moving forward. European Journal of Education, 42(3), 351–362. doi:10.1111/j.1465-3435.2007.00311.x

- Cable, D. M., Gino, F., & Staats, B. R. (2013). Breaking them in or eliciting their best? Reframing socialization around newcomers’ authentic self-expression. Administrative Science Quarterly, 58(1), 1–36. doi:10.1177/0001839213477098

- Carpenter, A., & Greene, K. (2016). Social penetration theory. In C. Berger & M. Roloff (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of interpersonal communication (pp. 1–4). Wiley-Blackwell. doi:10.1002/9781118540190.wbeic160.

- Carroll, D. (2016). Postgraduate research experience 2015: A report on the perceptions of recent higher degree research graduates. Graduate Careers Australia.

- Carson, J. (2019). External relational attributions: Attributing cause to others’ relationships. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(5), 541–553. doi:10.1002/job.2360

- Cassell, C., & Symon, G. (2004). Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research. SAGE.

- Cheng, M., Taylor, J., Williams, J., & Tong, K. (2016). Student satisfaction and perceptions of quality: Testing the linkages for PhD students. Higher Education Research & Development, 35(6), 1153–1166. doi:10.1080/07294360.2016.1160873

- Cho, C. H., Roberts, R. W., & Roberts, S. K. (2008). Chinese students in US accounting and business PhD programs: Educational, political and social considerations. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 19(2), 199–216. doi:10.1016/j.cpa.2006.09.007

- Cozby, P. C. (1972). Self-disclosure, reciprocity and liking. Sociometry, 35(1), 151–160. doi:10.2307/2786555

- Dai, N. T., Free, C., & Gendron, Y. (2019). Interview-based research in accounting 2000–2014: Informal norms, translation and vibrancy. Management Accounting Research, 42, 26–38. doi:10.1016/j.mar.2018.06.002

- Department of Education, Skills and Employment. (2019). Table 2.3: All students by level of course and broad field of education, full year 2018, Retrieved file:///D:/Downloads/2018_section_2_-_all_students%20(2).pdf.

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. (2021). Australia Awards Scholarships policy handbook. https://www.dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/australia-awards-scholarships-policy-handbook

- Edmondson, A. C., & McManus, S. E. (2007). Methodological fit in management field research. Academy of Management Review, 32(4), 1246–1264. doi:10.5465/amr.2007.26586086

- Edwards, D., Bexley, E., & Richardson, S. (2011). Regenerating the academic workforce: The careers, intentions and motivations of higher degree research students in Australia: Findings of the National Research Student Survey. Australian Council for Educational Research.

- Fernandez-Rio, J., Cecchini, J. A., Mendez-Gimenez, A., & Carriedo, A. (2021). Mental well-being profiles and physical activity in times of social isolation by the COVID-19: A latent class analysis. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 20(2), 1–15. doi:10.1080/1612197X.2021.1877328.

- Flick, U. (2018). An introduction to qualitative research (6th ed.). Sage.

- Fox, K. A. (2018). The manufacture of the academic accountant. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 57, 1–20. doi:10.1016/j.cpa.2018.01.005

- Gardner, W. L., Karam, E. P., Tribble, L. L., & Cogliser, C. C. (2019). The missing link? Implications of internal, external, and relational attribution combinations for leader-member exchange, relationship work, self-work, and conflict. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(5), 554–569. doi:10.1002/job.2349

- Gill, P., & Burnard, P. (2008). The student–supervisor relationship in the PhD/doctoral process. British Journal of Nursing, 17(10), 668–671. doi:10.12968/bjon.2008.17.10.29484

- Goemaere, S., Van Caelenberg, T., Beyers, W., Binsted, K., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2019). Life on Mars from a self-determination theory perspective: How astronauts’ needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness go hand in hand with crew health and mission success-results from HI-SEAS IV. Acta Astronautica, 159, 273–285. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2019.03.059

- Greene, K., Derlega, V. J., & Mathews, A. (2006). Self-disclosure in personal relationships. In A. L. Vangelisti, & D. Perlman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of personal relationships (pp. 409–427). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511606632.023

- Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. doi:10.1177/1525822X05279903

- Halse, C., & Malfroy, J. (2010). Retheorizing doctoral supervision as professional work. Studies in Higher Education, 35(1), 79–92. doi:10.1080/03075070902906798

- Hamilton, J., & Carson, S. (2015). Supervising practice: Perspectives on the supervision of creative practice higher degrees by research. Educational Philosophy & Theory, 47(12), 1243–1249. doi:10.1080/00131857.2015.1094904

- Harrison, S., & Grant, C. (2015). Exploring of new models of research pedagogy: Time to let go of master–apprentice style supervision? Teaching in Higher Education, 20(5), 556–566. doi:10.1080/13562517.2015.1036732

- Hemer, S. R. (2012). Informality, power and relationships in postgraduate supervision: Supervising PhD candidates over coffee. Higher Education Research & Development, 3(6), 827–839. doi:10.1080/07294360.2012.674011

- Hobson, A. J., & Maxwell, B. (2017). Supporting and inhibiting the well-being of early career secondary school teachers: Extending self-determination theory. British Educational Research Journal, 43(1), 168–191. doi:10.1002/berj.3261

- Hofmans, J., Dóci, E., Solinger, O. N., Choi, W., & Judge, T. A. (2019). Capturing the dynamics of leader–follower interactions: Stalemates and future theoretical progress. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 4(3), 382–385. doi:10.1002/job.2317

- Howells, K., Stafford, K., Guijt, R., & Breadmore, M. (2017). The role of gratitude in enhancing the relationship between doctoral research students and their supervisors. Teaching in Higher Education, 22(6), 621–638. doi:10.1080/13562517.2016.1273212

- Hutchings, M. (2017). Improving doctoral support through group supervision: Analysing face-to-face and technology-mediated strategies for nurturing and sustaining scholarship. Studies in Higher Education, 42(3), 533–550. doi:10.1080/03075079.2015.1058352

- Jiang, L., Bazarova, N. N., & Hancock, J. T. (2011). The disclosure‒intimacy link in computer-mediated communication: An attributional extension of the hyperpersonal model. Human Communication Research, 37(1), 58–77. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.2010.01393.x

- Johansson, C., & Yerrabati, S. (2017). A review of the literature on professional doctorate supervisory styles. Management in Education, 31(4), 166–171. doi:10.1177/0892020617734821

- Joinson, A. N., & Paine, C. B. (2007). Self-disclosure, privacy and the internet. In A. Joinson, K. McKenna, & T. Postmes (Eds.), Oxford handbook of internet psychology (pp. 237–252). Oxford University Press.

- Jones, E. E., & Davis, K. E. (1965). From acts to dispositions the attribution process in person perception. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 219–266). Academic Press.

- Khosa, A., Burch, S., Ozdil, E., & Wilkin, C. (2020). Current issues in PhD supervision of accounting and finance students: Evidence from Australia and New Zealand. British Accounting Review, 52(5), 100874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2019.100874.

- Kiley, M. (2017). Reflections on change in doctoral education: An Australian case study. Studies in Graduate & Postdoctoral Education, 8(2), 78–87. doi:10.1108/SGPE-D-17-00036

- Lee, A. (2008). How are doctoral students supervised? Concepts of doctoral research supervision. Studies in Higher Education, 33(3), 267–281. doi:10.1080/03075070802049202

- Lei, X., Kaplan, S. A., Dye, C. E., & Wong, C. M. (2019). On the subjective experience and correlates of downtime at work: A mixed-method examination. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(3), 360–381. doi:10.1002/job.2336

- Levine, J. M., & Moreland, R. L. (2008). Small groups: Key readings. Psychology Press.

- Manathunga, C. (2012). Supervisors watching supervisors: The deconstructive possibilities and tensions of team supervision. Australian Universities’ Review, 54(1), 29–37. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316informit.424318263696740

- Martela, F., Hankonen, N., Ryan, R. M., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2021). Motivating voluntary compliance to behavioural restrictions: Self-determination theory–based checklist of principles for COVID-19 and other emergency communications. European Review of Social Psychology, 32(2), 305–347. doi:10.1080/10463283.2020.1857082

- McCallin, A., & Nayar, S. (2012). Postgraduate research supervision: A critical review of current practice. Teaching in Higher Education, 17(1), 63–74. doi:10.1080/13562517.2011.590979

- McGagh, J., Marsh, H., Western, M., Thomas, P., Hastings, A., Mihailova, M., & Wenham, M. (2016). Review of Australia’s research training system. Australian Council of Learned Academies.

- Montani, F., Maoret, M., & Dufour, L. (2019). The dark side of socialization: How and when divestiture socialization undermines newcomer outcomes. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(4), 506–521. doi:10.1002/job.2351

- Ntoumanis, N., Ng, J. Y., Prestwich, A., Quested, E., Hancox, J. E., Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C., Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Lonsdale, C., & Williams, G. C. (2021). A meta-analysis of self-determination theory-informed intervention studies in the health domain: Effects on motivation, health behavior, physical, and psychological health. Health Psychology Review, 15(2), 214–244. doi:10.1080/17437199.2020.1718529

- Omarzu, J. (2000). A disclosure decision model: Determining how and when individuals will self-disclose. Personality & Social Psychology Review, 4(2), 174–185. doi:10.1207/S15327957PSPR0402_05

- Parks, M. R., & Floyd, K. (1996). Meanings for closeness and intimacy in friendship. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 13(1), 85–107. doi:10.1177/0265407596131005.

- Pearson, M. (2012). Building bridges: Higher degree student retention and counselling support. Journal of Higher Education Policy & Management, 34(2), 187–199. doi:10.1080/1360080X.2012.662743

- Revelo, R. A., & Loui, M. C. (2016). A developmental model of research mentoring. College Teaching, 64(3), 119–129. doi:10.1080/87567555.2015.1125839