Abstract

The present study investigates the relationship between transformational leadership (TL) and work engagement (WE). After the devastating effects of the recently hit global pandemic, organizations attempted to employ resilient strategies as turnaround strategies to gain the lost businesses. This study was conducted against the backdrop of the new normal wherein transformational leaders played a significant role in encouraging employee empowerment that enhances WE. In a developing nation (India) context, a conceptual model was developed and tested using the data collected from 256 employees working in the information technology (IT) sector in the southern part of India. After checking the psychometric properties using the structural equation modelling (Lisrel package), the data were analyzed using Hayes’s PROCESS macros. The findings support (i) a positive association of TL with WE and employee empowerment, (ii) employee empowerment is a significant predictor of WE, and (iii) employee engagement mediated the relationship between TL and WE. Results also suggest that (i) work experience moderated the relationship between TL and WE, and (ii) gender moderates the relationship between TL and employee empowerment. The implications for leadership theory and practice are discussed.

1. Introduction

The seminal work of Bass (Citation1985) on “transformational leadership” has attracted the attention of researchers and practitioners in organizational behavior and personnel psychology (Alessa, Citation2021; Breevaart & Zacher, Citation2019; Farahnak et al., Citation2020, Podsakoff et al., Citation1990; Sivagnanam et al., Citation2022; Sułkowski et al., Citation2020). Mounting empirical evidence suggests that the success of any organization largely depends on the ability of the leaders to motivate employees to perform at their best (D’Souza et al., Citation2022; Fayda-Kinik, Citation2022; Knight et al., Citation2017). Transformational leaders have the ability to face challenging situations and effectively manage crises (Tengi et al., Citation2017). Transformational leaders inspire the employees, build trust and encourage innovative ideas, and bring transformation in employees to increase productivity and performance (Bass, Citation1985; Breevaart & Zacher, Citation2019; Masa’deh et al., Citation2016; Tims et al., Citation2011).

The recently hit global pandemic has imposed several challenges on organizations in various sectors worldwide (Irshad et al., Citation2021; Lonska et al., Citation2021; Zieba & Bongiovanni, Citation2022). The pandemic also resulted in new practices such as working from home, web-based teaching and instructions, and virtual meetings (Arntz et al., Citation2020; Kramer & Kramer, Citation2020). These changes-imposed work pressures on the employees working in the information technology (IT) sector because organizations depend on IT services. For example, in higher educational institutions, an overnight move to web-based instruction exerted tremendous pressure on the employees in the IT sector (Anjani et al., Citation2020; Satpathy et al., Citation2021). In addition, especially in a developing country (India), employees undergo stress to meet the unexpected and unprecedented demands of the job (Chatterjee & Shukla, Citation2020).

This study aims to unravel how TL exhibited in organizations helps improve WE in the context of a developing country, India. Recent studies reported that transformational leaders play a crucial role in dealing with stressful situations, such as the global pandemic, and increase productivity and performance (Balakrishnan et al., Citation2022; Mushtaque et al., Citation2022). For example, employees in the IT sector helped faculty members in higher educational institutions to meet the changing needs of web-based instruction (Masry-Herzalah & Dor-Haim, Citation2022; Sivagnanam et al., Citation2022). In addition, transformational leaders can get the performance of employees beyond expectations and motivate them to reach psychological (Thomas & Velthouse, Citation1990). Extant research on TL reported positive outcomes: job satisfaction, employee commitment, performance, and organizational citizenship behavior (Buil et al., Citation2019; Farahnak et al., Citation2020; Somali & Motwali, Citation2018; Yang et al., Citation2019).

While most studies on the effectiveness of TL were conducted in the western world, reflections on developing countries are relatively sparse, especially in the context of employees working in the IT sector (Jnaneswar & Ranjit, Citation2020; Rajagopalan et al., Citation2022; Usman et al., Citation2021). This study aims to bridge the gap by investigating how transformational leaders influence employees to engage at work during the new normal post-pandemic situation characterized by unprecedented workplace changes. Building on the previous literature, this study incorporates empowerment as a linkage between TL and WE in employees in the IT sector in India. Since employees’ work experience plays a vital role in influencing the effect of TL on WE, this research investigates the relationships between TL, empowerment, WE, gender, and work experience. This research attempts to address the following research questions (RQs):

RQ1:

How does empowerment mediates the relationship between transformational leadership and WE?

RQ2:

How does work experience moderate the relationship between TL and WE?

RQ3: How does gender moderates the relationship between transformational leadership and empowerment?

An overarching conceptual model tested in this study makes several significant contributions to leadership and human resource development literature:

TL, as a precursor to working engagement, especially during the post-pandemic period, adds to the growing body of research in leadership.

This research underscores the importance of employee empowerment in enhancing WE. It is documented in this study that TL, in addition to the direct effect, has an indirect impact through empowerment.

The findings from this study indicate that work experience plays a vital role in strengthening the relationship between TL and WE.

Gender differences in the relationship between TL and empowerment are highlighted in this research. To sum up, the conceptual model developed and tested in the context of employees in the information technology (IT) sector, particularly in a developing country, India, is a pivotal contribution.

Considering the paradigmatic shift in the work culture in many organizations during the post-pandemic period (labeled as the “new normal”), this research adds to a limited number of studies available.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 covers the theoretical background and hypotheses development based on the literature review. Section 3 deals with the methodology, followed by an analysis in section 4. Section 5 covers the discussion section that includes the theoretical and practical implications, limitations, suggestions for future research, and conclusion.

2. Theoretical background and hypotheses development

The Full Range Leadership (FRLT) (Burns, Citation1978) and Job Demands—Resources (JD-R) (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007a; Demerouti et al., Citation2001) provide the theoretical underpinning for this research. During the past three decades, the FRLT has dominated the literature on workplace leadership (Bass & Avolio, Citation1994; Lord et al., Citation2017). This leader-centered concept views work administrators as actors who can influence business results (Avolio et al., Citation1999; Judge & Piccolo, Citation2004). FRLT states supervisory behaviors are vital in influencing employees for superior performance. Three meta-categories of leadership styles—transactional, transformational, and passive, have been advanced by (Derue et al., Citation2011).

Multiple researchers note that supervisors’ transformational and, to a lesser extent, transactional leadership styles contribute to subordinates’ intended work outcomes, such as favorable mindsets and performance, whereas an inert stance seems detrimental (Judge & Piccolo, Citation2004; Wang et al., Citation2011). By comparing the two leadership styles—transformational and transactional, the early scholars argued that transformational leadership is more effective at achieving desired organizational results. Transformational leaders motivate employees to work to their fullest potential and contribute to achieving goals effectively (Bass, Citation1985; Shamir et al., Citation1993). Digging up the literature, we find that among several theories on leadership (trait, behavioral, situational), and servant leadership (Ruiz-Palomino et al., Citation2023), one of the contemporary theories widely discussed is “TL” (Bass, Citation1985). Organizations embrace transformational leaders because they motivate and encourage employees to perform beyond expectations (Howell & Avolio, Citation1993). Literature heavily documented the positive association of TL with performance (Hater & Bass, Citation1988; Zohar, Citation2002) and employee commitment (Fernet et al., Citation2015). TL is empirically found to be negatively associated with stress, burnout, and turnover intentions (Bycio et al., Citation1995; Rüsch & Corrigan, Citation2002).

JD-R (Bakker et al., Citation2001; Demerouti et al., Citation2001) is another theoretical platform on which this study is based. According to the model, stress and burnout increase when job demands are high, and employment resources/positives are low. In contrast, many positive aspects of the workplace can mitigate the consequences of high job demands. The JD-R model identifies two broad categories of job characteristics—job demands and resources. Job demands engage psychological, physical, social, and organizational characteristics that need sustained physical effort (Demerouti et al., Citation2001). For instance, a heavy burden is emotionally taxing interactions with clients. Job requirements absorb effort and energy, consequently affecting employee health and contributing to consequences such as burnout, which is a health destruction development (Schaufeli & Bakker, Citation2004). In contrast, job resources are the physical, psychological, social, and organizational aspects of the job that assist in achieving work purposes, reducing job demands, or inspiring personal growth, learning, and growth (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007a). Examples include job autonomy, social support, suggestions, and recognition from others. Motivation is initiated by occupational resources (Schaufeli & Bakker, Citation2004). They satisfy fundamental psychological requirements like independence, connection, and ability. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation encourage greater work engagement, organizational commitment, satisfaction, and achievement (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2017). The earlier researchers confirmed that the JD-R model has mainly confirmed that various job demands are optimistically related to burnout while diverse job resources are related to engagement (Crawford et al., Citation2010; Halbesleben, Citation2010; Nahrgang et al., Citation2011). Data is also building to argue for the contentions that job resources have a protective role in mitigating the adverse effects of job demands on worker results (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2017; Xanthopoulou et al., Citation2007) and hold superior salience under conditions of elevated job demands (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007a). In sum, organizations provide job resources (physical, social, psychological, and organizational resources) to employees to complete their work goals. Organizations also create job demands (the physical, social, and psychological efforts and energy) required from the employees to complete the tasks (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007a). To promote a friendly work environment, it is essential to maintain the proper balance between the demands and resources (Demerouti & Bakker, Citation2011). Using the FRLT and JD-R, we explain how TL positively influences WE. As leadership style significantly affects the degree to which leaders encourage employee empowerment, JD-R helps demonstrate the effectiveness of TL in this process.

2.1. Hypotheses development

2.1.1. The relationship between TL and WE

Transformational leaders inspire employees and enhance their self-efficacy to reach individual and organizational goals (Fitzgerald & Schutte, Citation2010). The inspirational motivation stemming from transformational leaders enables employees to see the vision and contribute to their full potential. Inspirational motivation helps share the common goals of organizational effectiveness, thus assisting employees in focusing on work (D’Souza et al., Citation2022). Transformational leaders, through individualized consideration, pay close attention to the needs and requirements of employees, thereby influencing them to complete given tasks (Avolio & Bass, Citation2001; Jung et al., Citation2009). I realized influence makes transformational leaders role models in the eyes of employees who, in turn, believe that engaging in work is essential to perform effectively (Ekaningsih, Citation2014; Han et al., Citation2020). Through intellectual stimulation, leaders encourage and promote the creative ideas of employees, which would motivate them to engage in work with vigor and dedication (Avolio & Bass, Citation2001; Jung et al., Citation2003; Schaufeli et al., Citation2002).

Leaders motivate employees to be adaptive and encourage them to follow new technical approaches to meet changing situations (Khan et al., Citation2020; Kovjanic et al., Citation2013).

WE is a positive emotional-motivational state consisting of three elements: vigor, dedication, and absorption (Schaufeli et al., Citation2002). Vigor is related to the energy levels, mental resilience, and effort employees exert while performing jobs. Dedication is associated with the sincerity and honesty of doing work and explains how enthusiastic and inspired the employee is in performing given tasks. Absorption, the third component, is related to the degree to which an employee is focused or immersed in a job (Lopez-Zafra et al., Citation2022). A plethora of research provided mounting evidence that TL is positively associated with WE (Breevaart et al., Citation2014; Decuypere & Schaufeli, Citation2020; Lai et al., Citation2020; Rahmadani & Schaufeli, Citation2022). For example, in a study conducted among 530 full-time employees in Australia, the researchers found that TL style positively influenced the followers’ attributes of WE (Ghadi et al., Citation2013). Furthermore, in a recent study conducted among 261 police officers in China, the researchers reported the positive impact of TL on WE (Meng et al., Citation2022). Thus, based on abundant available empirical evidence, we offer the following hypothesis:

H1:

TL is significantly and positively related to WE

2.1.2. The relationship between TL and employee empowerment

In the management literature, empowerment is traditionally perceived as delegating authority and power to subordinates (Daft, Citation2014). The notion of empowerment builds on the well-grounded body of participative management, job enrichment, and alienation research (Spreitzer et al., Citation1997). Though started as a concept emphasizing self-efficacy (Conger & Kanungo, Citation1988), the cognitive model of empowerment includes intrinsic motivation (called psychological empowerment) and control over resources to perform given tasks, in addition to authority (Thomas & Velthouse, Citation1990). Employee empowerment is a strategy employed by organizations to promote employees’ decision-making skills resulting in employee development, TL, and employee empowerment. Extant research reported that TL style is positively associated with empowerment and creativity (Özaralli, Citation2003; Wei et al., Citation2010). In a survey conducted on 200 nursing staff from hospitals in Malaysia, Choi et al. (Citation2016) reported that TL resulted in job satisfaction mediated through employee empowerment. A recently conducted field study on 126 employees in a multinational technological company revealed that empowerment moderated the relationship between TL and innovation (Grošelj et al., Citation2021). Nearly two decades back, Kark et al. (Citation2003) empirically demonstrated that the effect of TL on employees could be vouched from empowerment. While intellectual simulation enhances employees’ self-efficacy and commitment, inspirational motivation enables employees to assume more significant responsibilities, accept accountability, and engage in decision-making. Thus, based on available empirical evidence, we offer the following hypothesis;

H2:

TL is significantly and positively related to employee empowerment.

2.1.3. The relationship between employee empowerment and WE

For organizations, effective employee empowerment and engagement is a critical consideration as it leads to a high organizational performance that is measurable by positive financial performance (Alfes et al., Citation2013). In a recently conducted study on 370 nurses in hospitals in China, the researchers found that empowerment significantly positively affects WE (Gong et al., Citation2020). As Wang et al. (Citation2022) argued, it is essential to implement employee empowerment in organizations to increase productivity and profitability. Macey and Schneider (Citation2008) advocated that empowerment is one of the best strategies organizations embrace to influence workers to superior performance. Several researchers have heavily documented the benefits of empowerment on WE, productivity, commitment, and performance (Al-Abdullat & Dababneh, Citation2018; Allen et al., Citation2018). A study conducted on bank employees in Jordan found that to achieve goals, managers must be trained to promote empowerment (Dahou & Hacini, Citation2018). Thus, based on abundant evidence in support of the positive effect of empowerment on WE, we offer the following hypothesis:

H3:

Employee empowerment is significantly and positively related to WE.

2.1.4. Employee empowerment as a mediator

Though transformational leaders play an essential role in motivating workers to engage in whatever tasks they do, the implementation of employee empowerment contributes to

Since increasing WE is challenging, transformational leaders may foster engagement by energizing through empowerment (Liden et al., Citation2000; Macey & Schneider, Citation2008). TL encourages creativity and innovation and gives adequate power to employees to implement their ideas (Bass & Riggio, Citation2006; Eiseneiss et al., Citation2008). In the empowerment model, Spreitzer et al. (Citation1997) argued that employees find meaning in their work, which has a vital role in WE, performance, and productivity (Rosso et al., Citation2010). In addition, several prominent scholars reported that transformational leaders significantly alter the beliefs, values, and needs of employees (Gardner et al., Citation2005), increase the level of commitment and citizenship behavior (Nguni et al., Citation2006), and respect the opinions of employees (Jung et al., Citation2009).

In this study, we argue that in addition to the direct influence of transformational leaders on WE, indirect effects can be felt through employee empowerment.

To the best of our knowledge, the mediation of employee empowerment has rarely been studied by researchers. Though that is not the rationale for studying the mediating role of employee empowerment, using the logos (Aristotelian rhetoric), it would be interesting to investigate how transformation leaders influence employees’ WE through empowerment. Based on the direct positive relationships, we offer the following exploratory mediation hypothesis:

H4:

Employee empowerment mediates the relationship between TL and WE.

2.1.5. Work experience as a moderator

Past researchers have examined the impact of individual characteristics of employees: experience and ability on job performance (Ng & Feldman, Citation2009; Waldman & Spangler, Citation1989). While transformational leaders influence the employees to engage in their work, it is more likely that individuals with higher work experience may follow the leaders and show a higher level of WE. Two field studies by Yücel and Richard (Citation2013) found that employee experience played a vital role in the dyadic relationship between transformational leaders and employees; more experienced employees showed strong commitment than less experienced employees. When transformational leaders persuade their employees to perform tasks beyond their self-interests (Yammarino et al., Citation1993), the ability of employees to understand the vision differs based on their work experience. Therefore, the subordinates’ characteristics need to be factored into before assessing the impact of TL on employees’ WE. It would be interesting to investigate how work experience strengthens the relationship between TL and WE. This research explores the moderating effect of work experience, and the hypothesis offered is as follows:

H1a:

Work experience of employees moderates the relationship between TL and WE such that the effect of TL on WE is stronger (weaker) for employees with higher (lower) work experience.

2.1.6. Gender as a moderator

The literature on gender studies reveals marked differences in how individuals react to situations in work organizations (Çoban, Citation2022; Gherardi, Citation1994; Kelan, Citation2010). Particularly in the Indian context, the traditional family system considers men as breadwinners, and women are restricted from performing household activities. However, the centralization of the domestic role of women is gradually fading away when women started employment in organizations during the last five decades (Chidambaram et al., Citation2022). Urbanization and industrialization have paved the way for women’s employment, though most women in developing countries consider the home environment culturally viewed as a female domain (Gielen & Roopnarine, Citation2005).

In this study, we argue that gender differences are more likely to influence the effect of TL on empowerment. Though bias and stereotyping effects gender in work organizations, in most organizations, men dominate the positions of power (Ladergaard, Citation2011). In contrast, women show higher WE and job satisfaction (Zou, Citation2015). Furthermore, Kim and Shin (Citation2017) found that gender significantly affects psychological empowerment, such that male subordinates are more strongly influenced by TL than their female counterparts. Thus, based on the scant available empirical evidence, we offer the following moderation hypothesis:

H2a:

Gender moderates the relationship between TL and employee empowerment such that empowerment is higher for male employees than for female employees.

The conceptual model is presented in Figure .

3. Methodology

3.1. Variables in this study

3.1.1. Transformational Leadership

Transformational Leadership. TL is defined as “a relationship in which leaders and followers raise one another to higher levels of motivation and morality” (Burns, Citation1978, p. 6). According to Bass and Avolio (Citation1994), TL has four dimensions: (i) individualized consideration, (ii) intellectual stimulation, (iii) inspirational motivation, and (iv) idealized influence.

The individualized consideration dimension concerns how leaders listen to the employee’s concerns and needs and give support. By showing individual consideration, employees do not feel they are neglected. On the contrary, leaders are more likely to be intrinsically motivated when they respect every employee and pay special attention to their needs.

The intellectual stimulation dimension is related to how leaders encourage employees to think creatively and independently. As a result, individuals get stimulated to face unexpected situations and learn from the opportunities stemming from the environment.

The inspirational motivation dimension concerns how leaders articulate the vision and give challenging assignments to the employees. Leaders also raise performance standards and instil optimism about achieving organizational goals effectively. Finally, leaders motivate employees and help build confidence to perform given tasks. The idealized influence dimension is concerned with which the leaders act as role models by exhibiting high ethical behavior and following moral values.

Podsakoff et al (Citation1990) argue that TL consists of six behaviors—identifying and articulating vision, fostering acceptance of group goals, instilling high-performance expectations, provide individualized support, and intellectual stimulation. Following McKenzie et al. (Citation2001), Carless et al. (Citation2000) developed a short measure of TL consisting of the above-mentioned dimensions. In this study, we followed Global Transformational Leadership scale developed by Carless et al. (Citation2000).

3.2. Work engagement

Work engagement is “a positive, fulfilling work-related state of mind characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption” (Schaufeli et al., Citation2002, p. 74). The literature on human resource development (HRD) distinguishes between three types of engagement: employee engagement, work engagement, and organizational engagement. Employee engagement is the “simultaneous employment and expression of a person’s preferred self in task behaviors that promote connections to work and others, personal presence, and dynamic full role performance (Kahn, Citation1990, p. 700). Organizational engagement concerns “the extent to which an individual is psychologically present in a particular organizational role” (Saks, Citation2006, p. 604). Several scholars (Alok & Israel, Citation2012; Babcock-Roberson & Strickland, Citation2010; Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2008; Halbesleben et al., Citation2009; Kim & Shin, Citation2017; Park et al., Citation2018) documented that positive outcomes such as in-role performance, financial benefits, and extra-role behavior, creativity, and client satisfaction (Bakker, Citation2017; Bakker & Xanthopoulou, Citation2009; Chidambaram et al., Citation2022; Halbesleben & Wheeler, Citation2008; Harter et al., Citation2002; Nguyen et al., Citation2019). In addition, extant research empirically found that engaged workers show high dedication in completing given tasks, offer high energy levels and get enthusiastically involved in work, and contribute to higher productivity and performance (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2014, Rich et al., Citation2010; Joubert & Roodt, Citation2011).

3.3. Empowerment

Empowerment is an employee’s ability to make individual decisions and assume accountability for the outcomes (Shuck & Rose, Citation2013). As opposed to the traditional delegation of authority, present-day managers give autonomy to employees to make decisions (Andrew & Sofian, Citation2012; Jose & Mampilly, Citation2014) because of potential benefits in terms of the quality of products and services (Markos & Sridevi, Citation2010; Shuck & Reio, Citation2014), gaining the trust of employees (Bekirogullari, Citation2019). Extant research reported that empowered employees proactively engage in performing work and make suggestions to improve the quality of products and services through innovation (Altaher et al., Citation2018). Empowerment also includes, in addition to making independent decisions, participation in setting goals, objectives, and strategies for improving performance (Heathfield, Citation2012). Companies, to promote empowerment, offer ongoing training and development opportunities to employees Isimoya and Bakarey (Citation2013); Taneja et al. (Citation2015).

3.4. Gender and work experience

The demographic variables used in this study are gender and work experience. The literature reported gender differences in several studies such as personality, work–life conflicts, work–life balance, internet addiction, and academic performance (Chidambaram et al., Citation2022; Przepiorka et al., Citation2021), and it would be interesting to investigate gender as a moderator in the relationship between TL and empowerment.

3.5. Sample

To test the hypothesized relationships, we used a carefully crafted survey instrument to collect data from employees in the information technology (IT) sector in southern India. Data was collected from employees working in Tata Consultancy Services, Infosys Wipro, and Tech Mahindra. Since data collection was done during the post-pandemic phase and still social distancing norms were followed by most of the organizations, we preferred to use google forms to collect data, which has been the accepted practice followed by many previous researchers (Chidambaram et al., Citation2022; Jnaneswar & Ranjit, Citation2020). We secured the list of employees from IT organizations and took their permission to email the employees. We stated the purpose of the research is “academic” and requested the organizations to cooperate. Based on non-probabilistic convenience method of sampling, we sent Google forms to 735 employees and received 256 filled-out forms (response rate of 34.8%). We therefore included 256 surveys in the analysis. Since Google Forms does not allow the respondents to send incomplete surveys, all the surveys received were complete. In addition, we checked for non-response bias by comparing the first 50 respondents with the last 50 respondents and found no statistical differences between these two groups of respondents.

As far as the demographic profile is concerned, 174 (68%) were male, and 82 (32%) were female. About age, 85 (33.2%) were less than 25 years, 126 (49.2%) were aged between 25 and 35 years, 31 (12.1%) were aged between 35 and 45 years, 14 (5.5%) were aged between 45 and 55 years, and 14 (5.5%) were aged over 55 years. About the work experience, 85 (33.3%) had experience of less than 5 years, 41 (16%) had experience between 6 and 10 years, 71 (27.7%) had experience between 11 and 15 years, and 59 (23%) had experience of over 15 years.

3.6. Measures

The questionnaire consists of two parts: first part contains demographic profile of the respondents that includes age, gender, marital status, work experience in terms of number of years in organizations. The second part consists of information regarding the study variables.

The respondents were asked to answer the statements on a Likert-type 5-point scale [1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree].

Work engagement was measured with six items using the Utrech Work Engagement (UWES) scale developed by Schaufeli and Bakker (Citation2004). The work engagement dimensions; vigor (two items), dedication (two items) and absorption (two items). The reliability coefficient of work engagement was 0.91.

Transformational leadership was measured with six items using the Global Transformational Leadership Scale (GTL) developed by Carless et al. (Citation2000). The reliability coefficient of transformational leadership was 0.89.

Employee empowerment was measured with four items adapted from Chiles and Zorn (Citation1995) and Spreitzer et al. (Citation1997). The reliability coefficient of work engagement was 0.77.

4. Analysis and findings

4.1. Measurement model and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

As suggested by Anderson and Gerbing (Citation1988) we followed a two-step approach: (i) checking the measurement model and (ii) analyzing the structural model. We checked the measurement model by performing confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), using the Lisrel package of structural equation modelling (SEM). We presented the results of CFA in Table .

Table 1. Confirmatory factor analysis

As shown in Table , the standardized factor loadings of all the indicators are ranged between 0.77 and 0.90, thus over the acceptable minimum level of 0.70. The reliability coefficient Cronbach’s alphas for the three variables were greater than 0.70 (ranged between 0.77 and 0.91), thus vouching for reliability. The composite reliability (CR) for all the three variables ranged between 0.92 and 0.93, and the average variance extracted (AVE) estimates have exceeded minimum level of 0.50 (ranged between 0.66 and 0.76). These statistics vouch for internal consistency, convergent validity and reliability of the three constructs used in this research (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981; Hair et al., Citation2019).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics: means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations

4.2. Convergent validity, discriminant validity, and common method bias

The discriminant validity is said to be established when the square root of AVE of the variables exceed the correlations between the variables (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). The square roots of AVEs for TL and empowerment were 0.81 and 0.87, respectively, and these values are greater than the correlation between these variables (0.16). Similarly, the square roots of AVEs for TL and WE were 0.81 and 0.83, respectively, and these values are greater than the correlation between these variables (0.51). For all the variables, the square root of AVEs were greater than correlations, thus establishing the discriminant validity between all three variables used in this study.

The CFA results reveal that the three-factor model fit the data well [χ2 = 269.19; df = 101; χ2/df = 2.66; Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.074; Root mean square residual (RMR) = 0.031; Standardized RMR = 0.050; Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.93; Goodness-of-fit index (GFI) = 0.89]. Since the goodness-of-fit indices: (RMSEA < 0.08; CFI = 0.93; GFI = 0.89) provided a good fit of the data to the model (Browne & Cudeck, Citation1993).

To check the common method variance, we performed Harman’s one-factor analysis and found that single factor accounted for 39.51% of variance, which is less than 50% and hence the common method bias is not a problem with the data (Hair et al., Citation2019).

4.3. Descriptive statistics and multicollinearity

The descriptive statistics are mentioned in Table .

To check for the presence of multicollinearity it is customary to check the correlations between the variables. Since the correlations were less than 0.75, suggesting that multicollinearity is not a problem with the data (Tsui et al., Citation1995). We further assessed the variance inflation factor (VIF) for the indicators and found that all the values were less than the cut-off value of 5, thus suggesting that multicollinearity was not a problem with the data (Montgomery et al., Citation2021). The VIF values for the indicators were mentioned in Appendix A [See Appendix A given at the end].

4.4. Hypothesis testing

To test H1-H4, the Hayes (Citation2018) PROCESS macros were used (model number 4), and the results are presented in Table .

Table 3. Testing H1, H2, H3, and H4

Hypothesis 1 posits that TL is positively related to WE.

Step 1 from Table shows that the regression coefficient of TL on WE was positive and significant (β = 0.417; t = 9.37; p < 0.001). The results based on 20,000 bootstrap samples reveal that 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals did not contain “zero” (LLCI, 0.3296; ULCI = 0.5048), thus supporting H1.

Hypothesis 2 predicts that TL is positively associated with empowerment. As shown in Step 2 (Table ), the regression coefficient of TL on empowerment was positive and significant (β = 0.156; t = 2. 59; p < .001). The 95% (BCCI) LLCI and ULCI were 0.0291 and 0.2103, respectively, thus supporting H2.

Hypothesis 3 proposes that empowerment positively predicts WE and the regression coefficient of empowerment (Step 3, Table ) on WE was and significant (β = 0.119; t = 2.60; p < .01), thus supporting H3.

To check the Hypothesis 4, which states that empowerment mediates the relationship between TL and WE, the indirect effect must be examined. The indirect effect of TL on WE was 0.0187 [Boot se = 0.0112; Boot LLCI = 0.0013; Boot ULCI = 0.0447]. Since “zero” zero was not contained in the Boot LLCI and Boot ULCI, the results support the mediation hypothesis (H4).

To double check the results, we verified the total effect (0.4172), which is a total of direct effect (0.3985) and indirect effect (0.0187). The indirect effect is a product of regression coefficient of TL on empowerment (0.1560) and regression coefficient of empowerment on WE (0.1197) [i.e. 0.1560 × 0.1197 = 0.0187]. The total effect, therefore, is (0.3985 + 0.0187 = 0.4172). The indirect effect of TL → empowerment → WE was significant, thus rendering support to the mediation hypothesis 4.

4.5. Testing the moderation of work experience (H1a)

To test H1a, we used model number 1 of Hayes (Citation2018) PROCESS macros and presented the results in Table .

Table 4. Testing of hypothesis 1a (two-way interaction) Hayes (Citation2018) PROCESS macros (model number 1)

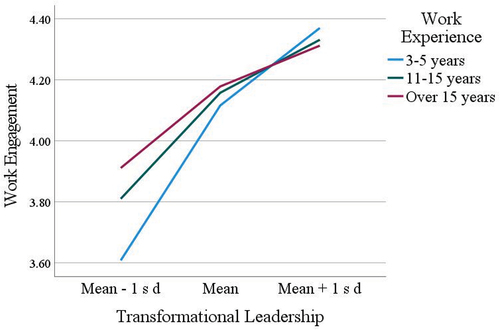

H1a posits that work experience moderates the relationship between TL and WE. As shown in Table , the regression coefficient of the interaction term (TL and work experience was significant (βTL x work experience = −0.080 t = −2.08; p < .05; Boot LLCI (−0.1559); Boot ULCI (−0.0045). These results support H1a as the regression coefficient of interaction term is negative. The visualization of two-way interaction is presented in Figure .

Figure depicts the relationship between TL and WE moderated by work experience. As can be seen in Figure , at lower levels of TL, work experience of 3–5 years is associated with lower WE when compared to work experience of 11–15 years, and over 15 years. The figure does not show that as TL increases people with more experience tend to show higher levels of WE. The results indicate that the effect of TL is more on the employees with lower experience. Therefore, the results did not support H1a.

Hypothesis 2a posits that gender is a moderator in the relationship between TL and empowerment. To test H2a, we used Hayes (Citation2018) PROCESS macros (model number 1) and presented the results in Table .

Table 5. Testing of hypothesis 2a (two-way interaction) Hayes (Citation2018) PROCESS macros (model number 1)

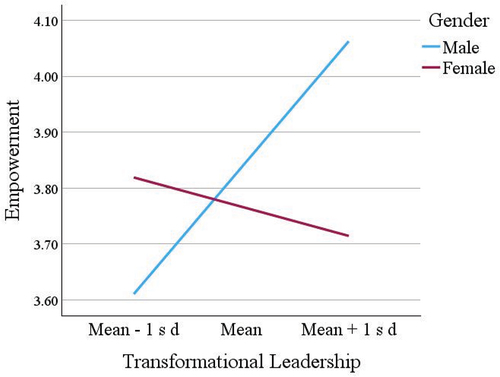

The results show that the regression coefficient of the interaction term is significant (β TL x gender= −0.364; t = −2.98; p < .05). These results, based on 20,000 bootstrap samples, show that the 95% Boot LLCI (−0.6037) and BOOT UL (−0.1241) shows significant values (as zero is not contained in the Lower and Upper limits), thus supporting H2a. The interactions model is significant and explains 24.7% variance in empowerment [R2 = 0.247; F (3,252) = 54.89; p < 0.001]. The conditional effects of the focal predictor at values of moderator (gender) are presented in the bottom of Table . The visual presentation of interaction effect of gender is done in Figure .

As shown in Figure , the lower levels of TL, the WE is high for females when compared to males. However, as the TL from “low” to “high”, the WE for females decrease whereas the WE increases for males. A decreasing slope for females and increasing scope of the curve for the males’ render support the moderation hypothesis (H2a).

The empirical model is presented in Figure

5. Discussion

In this research, we developed a conceptual model and tested the hypothesized relationships by analyzing the data collected from 256 employees working in the IT sector. After checking the instrument’s psychometric properties, we used Hayes (Citation2018) PROCESS macros and found support for all the hypotheses.

First, the findings indicated a positive association of TL with WE (Hypothesis 1), consistent with results from the literature (Lai et al., Citation2020; Meng et al., Citation2022). It is somewhat expected that all the dimensions of TL: intellectual stimulation, individualized consideration, idealized influence, and inspirational motivation help employees in WE, which in turn, increases performance. These findings aligning with the theoretical underpinnings of FRLT and JD-R. Second, the positive association between TL and employee empowerment (Hypothesis 2) found support in this research, which is consistent with the results of several studies in the literature (Choi et al., Citation2016; Grošelj et al., Citation2021). Third, this study found that employee empowerment positively predicts WE (Hypothesis 3), supported by extant research (Al-Abdullat & Dababneh, Citation2018; Dahou & Hacini, Citation2018). In present-day organizations, empowerment is used as a strategy employed by managers so that employees engage in decision-making and vent their ideas and opinions for the benefit of the organization. Fourth, the benefits of TL on WE are accrued through employee empowerment (Hypothesis 4), and findings from this study were in alignment with results from scant literature (Liden et al., Citation2000; Macey & Schneider, Citation2008).

Fifth, the results did not support the moderating effect of work experience in the relationship between TL and WE (Hypothesis 1a). We hypothesized that work experience of employees moderates the relationship between TL and WE such that the effect of TL on WE is stronger (weaker) for employees with higher (lower) work experience. On the contrary, we found that the effect of TL on WE is stronger for employees with lower experience. The findings thus indicate that when TL plays a vital role on employees with less experience when compared to more experienced employees. The effect of TL on work engagement is higher for experienced employees when TL is low. Sixth, following the gender studies, this research found that gender differences influence the relationship between TL and employee empowerment (H2a). Though earlier scholars scantly studied gender as a moderator, the previous studies vouched for gender differences in organizations (Gielen & Roopnarine, Citation2005; Kim & Shin, Citation2017). Overall, the conceptual model developed and tested has exciting results which are convincing.

5.1. Theoretical implications

The present research has several contributions to leadership and human resource management literature. First, this study adds to the growing literature on TL following the FRLT. Second, in congruence with human resource development, the results support the importance of WE, which is a precursor to superior performance. Though we did not study the effect of WE on performance, productivity, and job satisfaction, much research documented the positive effects of WE. Second, our results underscored the importance of employee empowerment in influencing WE. Third, through intellectual stimulation and inspirational motivation, transformational leaders allow employees to take on additional responsibilities through empowerment. Fourth, with regard to moderating hypothesis we found that less experienced employees tend to understand leaders’ vision and implement it through WE, whereas for more experienced employees TL does not have any significant role to play.

The fifth key contribution of this study is that transformational leaders need to understand gender differences in enforcing empowerment. In general, and as evidenced in this study, male employees are given additional roles and responsibilities compared to women. The effect of TL on employee empowerment was negative in the case of women, whereas the result was positive for male employees. The conceptual model adds to the literature, albeit with a small contribution.

5.2. Practical implications

This study has several implications for practicing managers, especially in the context of developing countries (such as India). First, the managers must understand that in the present-day “new normal” characterized by a post-pandemic environment, exhibiting TL is essential to enhance WE. Several employees have undergone stress and burnout during the pandemic; as evidenced in some recent studies (Chidambaram et al., Citation2022; Nagarajan et al., Citation2022), TL plays a vital role in bringing employees back to work in an efficient manner. Second, as found in this study, employee empowerment is a precursor for WE. Hence, managers must implement empowerment practices by delegating and decentralizing to the maximum extent so that employees can implement innovative ideas. Third, transformational leaders are advised to delegate heavy work to less experienced employees as they can easily understand and transmit the vision to lower-level management. Fourth, managers must consider gender differences while exhibiting leadership styles and empowering employees with additional responsibilities. Overall, this study makes some significant suggestions for administrators and advises them to demonstrate a TL style to enhance productivity and performance through WE.

5.3. Limitations and suggestions for future research

The results from this research need to be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, the sample consisted of employees in the IT sector, which may limit the generalizability of results in other industries (examples: healthcare and manufacturing). However, as long as the working conditions are similar, we expect the results to be generalizable across different sectors. Second, our study focused on a developing nation (India), and the effect of TL on WE in developed countries may differ because of work culture differences. Third, social desirability bias, common in survey-based research whereby the respondents bias the answers by giving an impression of good citizens, may tilt the findings. However, we have taken adequate care to minimize social desirability bias by anonymizing the responses, as suggested by earlier scholars (Latkin et al., Citation2017). Fourth, we focused only on a limited number of variables influencing WE: TL, empowerment, work experience, and gender. Fifth, this study did not include the effect of transactional leadership style on WE. Extant research reported that transactional leaders, by focusing on the task and the rewards are contingent on performance, it is more likely that WE would be influenced by transactional leadership style (D’Souza et al., Citation2022).

Sixth, as van Knippenberg and Sitkin (Citation2013) pointed out, the multi-dimensional conceptualization of TL has some inherent problems. How the dimensions are combined into TL is questionable, as there is no substantial empirical evidence that a dimensional structure was formed as prescribed. Further, the critics argue that TL does not explain how each dimension influences outcome variables. Despite this criticism, several researchers have used the TL style to influence employee commitment and engagement (D’Souza et al., Citation2022).

This study offers several avenues for future research. First, future studies may investigate the effect of TL on WE by collecting large samples from different parts of the country, India. Second, additional variables such as emotional intelligence, psychological capital, and emotional exhaustion may profoundly influence WE. Third, the antecedents of employee empowerment can be included in the model so that transformational leaders may focus on these antecedents. Fourth, future studies may investigate the effect of tenure, age, and experience on the WE and empowerment (Kim & Kang, Citation2017). Fifth, apart from gender differences and work experience, future researchers may include work-family conflicts, quality of work life, and performance feedback that significantly influence WE, productivity, and performance (Aruldoss et al., Citation2022; Kowalski et al., Citation2022). Sixth, future studies may include employee compassion as a moderator in the relationship between TL, empowerment, and work engagement. As person-organization fit may result in compassion-driven citizenship behavior, employee compassion may have direct and moderating effects on the relationship between TL and work engagement (Zoghbi-Manrique de Lara et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, leadership plays a vital role in enhancing the WE; future studies may also focus on various types of leadership (e.g., servant leadership) that profoundly influence organizational citizenship behavior and team performance (Ruiz-Palomino et al., Citation2023). Recent studies reported a positive impact of servant leadership on creativity (Ruiz-Palomino & Zoghbi-Manrique de Lara, Citation2020), and it would be interesting for future studies to dwell on servant leadership and investigate the relationships in the study. Finally, a comparison of various developing nations such as Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka about the influence of TL across multiple organizations can be studied by future researchers.

6. Conclusion

Most organizations worldwide have undergone a phenomenal metamorphosis in redesigning and re-inventing the organizational structure to bounce back from the devastating spell of the pandemic for nearly two and half years. This study provides novel insights into the ways of conducting business in the new normal. Through a simple conceptual framework, this study highlights the importance of TL in enhancing WE through empowerment. However, since it takes a long time before normal business functioning restores, organizations need to engage in novel ways of gaining lost businesses. The commitment on the part of top management to encouraging TL is expected to be continued for a long time, and it is hoped that TL, which came into vogue nearly three decades back, remains on the research agenda for a long time.

Bio of Authors.docx

Download MS Word (17.2 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge that this research work was partially financed by Kingdom University, Bahrain from the research grant number 2023-11-013.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2291851

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nishad Nawaz

Dr. Nishad Nawaz is a distinguished academician and prolific researcher with focus on artificial intelligence [AI] & human resource information system, and human resource management. He is also an accomplished writer, editor, and adviser with extensive experience in teaching and research. Dr Nishad Nawaz is currently working as an Associate Professor, Department of Business Management, College of Business Administration, Kingdom University, Bahrain. He served as a Guest Editor, Editorial Board Member and called special issues for well reputed journals. He published very good number of papers in well prestigious journals and presented papers in conferences across the Globe. He has conducted conferences, seminars and executive programs and he is a member in various professional associations and fellow of HEA UK.

References

- Al-Abdullat, B. M., & Dababneh, A. (2018). The mediating effect of job satisfaction on the relationship between organizational culture and knowledge management in Jordanian banking sector. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 25(2), 517–27. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-06-2016-0081

- Alessa, S. G. (2021). The dimensions of transformational leadership and its organizational effects in public universities in Saudi Arabia: A systematic Review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 682092. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.682092

- Alfes, K., Shantz, A. D., Truss, C., & Soane, E. C. (2013). The link between perceived human resource management practices, engagement and employee behaviour: A moderated mediation model. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(2), 330–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.679950

- Allen, S., Winston, B. E., Tatone, G. R., & Crowson, H. M. (2018). Exploring a model of servant leadership, empowerment, and commitment in non-profit organizations. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 29(1), 123–140. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21311

- Alok, K., & Israel, D. (2012). Authentic leadership & work engagement. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 47, 498–510.

- Altaher, D. A., Alqudah, D. S., & Shrouf, D. H. (2018). The impact of employees empowerment in business development on commercials banks. American Academic & Scholarly Research Journal, 10(1), 57–66.

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A Review and recommended two-Step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Andrew, O. C., & Sofian, S. (2012). Individual factors and work outcomes of employee engagement. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 40, 498–508.

- Anjani, P. K., Sundram, S., & Abinaya, V. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on work force in the information technology sector. European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine, 7(2), 3660–3674.

- Arntz, M., Yahmed, B. S., & Berlingieri, F. (2020). Working from home and COVID-19: The chances and risks for gender gaps. Intereconomics, 55(6), 381–386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10272-020-0938-5

- Aruldoss, A., Berube Kowalski, K., Travis, M. L., & Parayitam, S. (2022). The relationship between work–life balance and job satisfaction: Moderating role of training and development and work environment. Journal of Advances in Management Research, 19(2), 240–271.

- Avolio, B. J., & Bass, B. M. (2001). Developing potential across a full range of leadership tm: Cases on transactional and transformational leadership. Psychology Press.

- Avolio, B. J., Bass, B. M., & Jung, D. I. (1999). Re‐examining the components of transformational and transactional leadership using the multifactor leadership. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, 72(4), 441–462. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317999166789

- Babcock-Roberson, M. E., & Strickland, O. J. (2010). The relationship between charismatic leadership, work engagement, and organizational citizenship behaviors. The Journal of Psychology, 144(3), 313–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223981003648336

- Bakker, A. B. (2017). Strategic and proactive approaches to work engagement. Organizational Dynamics, 46(1), 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2017.04.002

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands‐resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2008). Towards a model of work engagement. Career Development International, 13(3), 209–223. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430810870476

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2014). Job demands-resources theory. In P. Y. Chen & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Work and wellbeing: A complete reference Guide (pp. 1–28). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118539415.wbwell019

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000056

- Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

- Bakker, A. B., & Xanthopoulou, D. (2009). The crossover of daily work engagement: Test of an actor–partner interdependence model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(6), 1562–1571. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017525

- Balakrishnan, S. R., Soundararajan, V., & Parayitam, S. (2022). Recognition and rewards as moderators in the relationships between antecedents and performance of women teachers: Evidence from India. International Journal of Educational Management, 36(6), 1002–1026. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-12-2021-0473

- Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. Free Press.

- Bass, B., & Avolio, B. (1994). Improving organisational effectiveness through transformational leadership. Sage Publications.

- Bass, B. M., & Riggio, R. E. (2006). Transformational Leadership, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Mahwah, NJ.

- Bekirogullari, Z. (2019). Employees’ empowerment and engagement in attaining personal and organisational goals. European Journal of Social & Behavioural Sciences, 26(3), 289–306. https://doi.org/10.15405/ejsbs.264

- Breevaart, K., Bakker, A., Hetland, J., Demerouti, E., Olsen, O. K., & Espevik, R. (2014). Daily transactional and transformational leadership and daily employee engagement. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, 87(1), 138–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12041

- Breevaart, K., & Zacher, H. (2019). Main and interactive effects of weekly transformational and laissez-faire leadership on followers’ trust in the leader and leader effectiveness. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, 92(2), 384–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12253

- Browne, M. W. (1993). Testing structural equation models. 136.

- Buil, I., Martínez, E., & Matute, J. (2019). Transformational leadership and employee performance: The role of identification, engagement and proactive personality. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 77, 64–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.06.014

- Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. Harper and Row.

- Bycio, P., Hackett, R. D., & Allen, J. S. (1995). Further assessments of Bass’s (1985) conceptualization of transactional and transformational leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80(4), 468.

- Carless, S. A., Wearing, A. J., & Mann, L. (2000). A short measure of transformational leadership. Journal of Business & Psychology, 14(3), 389–405. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022991115523

- Chatterjee, S., & Shukla, A. (2020). Identification and risk profiling of major stressors in the Indian IT sector. Global Business Review, 24(1), 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150919886457

- Chidambaram, V., Ramachandran, G., Chandrasekar, T., & Parayitam, S. (2022). Relationship between stress due to COVID-19 pandemic, telecommuting, work orientation and work engagement: Evidence from India. Journal of General Management, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/03063070221116512

- Chiles, A. M., & Zorn, T. E. (1995). Empowerment in organizations: Employees’ perceptions of the influences on empowerment. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 23(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909889509365411

- Choi, S. L., Goh, C. F., Adam, M. B. H., & Tan, O. K. (2016). Transformational leadership, empowerment, and job satisfaction: The mediating role of employee empowerment. Human Resources for Health, 14(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-016-0171-2

- Çoban, S. (2022). Gender and telework: Work and family experiences of teleworking professional, middle‐class, married women with children during the Covid‐19 pandemic in Turkey. Gender, Work, & Organization, 29(1), 241–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12684

- Conger, J. A., & Kanungo, R. N. (1988). The empowerment process: Integrating theory and practice. Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 471–482. https://doi.org/10.2307/258093

- Crawford, E. R., LePine, J. A., & Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 834–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019364

- Daft, R. (2014). New era Management (11th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Dahou, K., & Hacini, I. (2018). Successful employee empowerment: Major determinants in the Jordanian context. Eurasian Journal of Business and Economics, 11(21), 49–68. https://doi.org/10.17015/ejbe.2018.021.03

- Decuypere, A., & Schaufeli, W. (2020). Leadership and work engagement: Exploring explanatory mechanisms. German Journal of Human Resource Management, 34(1), 69–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/2397002219892197

- Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A. B. (2011). The job demands–resources model: Challenges for future research. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 37(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v37i2.974

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

- Derue, D. S., Nahrgang, J. D., Wellman, N. E., & Humphrey, S. E. (2011). Trait and behavioral theories of leadership: An integration and meta‐analytic test of their relative validity. Personnel Psychology, 64(1), 7–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01201.x

- D’Souza, G. S., Irudayasamy, F. G., & Parayitam, S. (2022). Emotional exhaustion, emotional intelligence and task performance of employees in educational institutions during COVID-19 global pandemic: A moderated-mediation model. Personnel Review, 52(3), 539–572. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-03-2021-0215

- Eisenbeiss, S. A., Van Knippenberg, D., & Boerner, S. (2008). Transformational leadership and team innovation: Integrating team climate principles. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1438.

- Ekaningsih, A. S. (2014). The effect of transformational leadership on the employees’ performance through intervening variables of empowerment, trust, and satisfaction (a study on coal companies in East Kalimantan). European Journal of Business and Management, 6(22), 111–117.

- Farahnak, L. R., Ehrhart, M. G., Torres, E. M., & Aarons, G. A. (2020). The influence of transformational leadership and leader attitudes on subordinate attitudes and implementation success. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 27(1), 98–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051818824529

- Fayda-Kinik, F. S. (2022). The role of organisational commitment in knowledge sharing amongst academics: An insight into the critical perspectives for higher education. International Journal of Educational Management, 36(2), 179–193. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-03-2021-0097

- Fernet, C., Trépanier, S.-G., Austin, S., Gagné, M., & Forest, J. (2015). Transformational leadership and optimal functioning at work: On the mediating role of employees’ perceived job characteristics and motivation. Work & Stress, 29(1), 11–31.

- Fitzgerald, S., & Schutte, N. S. (2010). Increasing transformational leadership through enhancing self‐efficacy. Journal of Management Development, 29(5), 495–505.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Gardner, W. L., Avolio, B. J., Luthans, F., May, D. R., & Walumbwa, F. (2005). Can you see the real me? A self-based model of authentic leader and follower development. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(3), 343–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.03.003

- Ghadi, M. Y., Fernando, M., & Caputi, P. (2013). Transformational leadership and work engagement: The mediating effect of meaning in work. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 34(6), 532–550. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-10-2011-0110

- Gherardi, S. (1994). The gender we think, the gender we do in our everyday organizational lives. Human Relations, 47(6), 591–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679404700602

- Gielen, U., & Roopnarine, J. (2005). Families in global perspective. Allyn and Bacon/Pearson.

- Gong, Y., Wu, Y., Huang, P., Yan, X., & Luo, Z. (2020). Psychological empowerment and work engagement as mediating roles between trait emotional intelligence and job satisfaction. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 232. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00232

- Grošelj, M., Černe, M., Penger, S., & Grah, B. (2021). Authentic and transformational leadership and innovative work behaviour: The moderating role of psychological empowerment. European Journal of Innovation Management, 24(3), 677–706. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-10-2019-0294

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Halbesleben, J. R. (2010). A meta-analysis of work engagement: Relationships with burnout, demands, resources, and consequences. Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research, 8(1), 102–117.

- Halbesleben, J. R., Harvey, J., & Bolino, M. C. (2009). Too engaged? A conservation of resources view of the relationship between work engagement and work interference with family. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(6), 1452–1465. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017595

- Halbesleben, J. R. B., & Wheeler, A. R. (2008). The relative roles of engagement and embeddedness in predicting job performance and intention to leave. Work & Stress, 22(3), 242–256.

- Han, S. J., Kim, M., Beyerlein, M., & DeRosa, D. (2020). Leadership role effectiveness as a mediator of team performance in new product development virtual teams. Journal of Leadership Studies, 13(4), 20–36.

- Harter, J. K., Schmidt, F. L., & Hayes, T. L. (2002). Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(2), 268.

- Hater, J. J., & Bass, B. M. (1988). Superiors’ evaluations and subordinates’ perceptions of transformational and transactional leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 73(4), 695.

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. The Guilford Press.

- Heathfield, S. M. (2012). Training: Your investment on people development and retention. Human Resource Journal, 56(2), 12–17.

- Howell, J. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1993). Transformational leadership, transactional leadership, locus of control, and support for innovation: Key predictors of consolidated-business-unit performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(6), 891–902. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.6.891

- Irshad, H., Umar, K. M., Rehmani, M., Khokhar, M. N., Anwar, N., Qaiser, A., & Naveed, R. T. (2021). Impact of work-from-home Human Resource practices on the performance of online teaching faculty during coronavirus disease 2019. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 740644. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.740644

- Isimoya, A., & Bakarey, B. (2013). Employees’ empowerment and customers’ satisfaction in insurance industry in Nigeria. Australian Journal of Business and Management Research, 3(5), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.52283/NSWRCA.AJBMR.20130305A01

- Jnaneswar, K., & Ranjit, G. (2020). Effect of transformational leadership on job performance: Testing the mediating role of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Advances in Management Research, 17(5), 605–625. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAMR-05-2020-0068

- Jose, G., & Mampilly, S. R. (2014). Psychological empowerment as a predictor of employee engagement: An empirical attestation. Global Business Review, 15(1), 93–104.

- Joubert, M., & Roodt, G. (2011). Identifying enabling management practices for employee engagement. Acta Commercii, 11(1), 88–110. https://doi.org/10.4102/ac.v11i1.155

- Judge, T. A., & Piccolo, R. F. (2004). Transformational and transactional leadership: A meta-analytic test of their relative validity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(5), 755–768. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.5.755

- Jung, D. I., Chow, C., & Wu, A. (2003). The role of transformational leadership in enhancing organizational innovation: Hypotheses and some preliminary findings. The Leadership Quarterly, 14(4–5), 525–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(03)00050-X

- Jung, D., Yammarino, F. J., & Lee, J. K. (2009). Moderating role of subordinates’ attitudes on transformational leadership and effectiveness: A multi-cultural and multi-level perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 20, 586–603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.04.011

- Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724. https://doi.org/10.2307/256287

- Kark, R., Shamir, B., & Chen, G. (2003). Two faces of transformational leadership: Empowerment and dependency. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(2), 246–255. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.2.246

- Kelan, E. K. (2010). Gender logic and (un)doing gender at work. Gender, Work, & Organization, 17(2), 174–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2009.00459.x

- Khan, H., Rehmat, M., Butt, T. H., Farooqi, S., & Asim, J. (2020). Impact of transformational leadership on work performance, burnout and social loafing: A mediation model. Future Business Journal, 6(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-020-00043-8

- Kim, N., & Kang, S. W. (2017). Older and more engaged: The mediating role of age linked resources on work engagement. Human Resource Management, 56(5), 731–746. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21802

- Kim, S., & Shin, M. (2017). The effectiveness of transformational leadership on empowerment: The roles of gender and gender dyads. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 24(2), 271–287. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCSM-03-2016-0075

- Knight, S. L., Lloyd, G. M., Arbaugh, F., Gamson, D., McDonald, S. P., Nolan, J., Jr., & Whitney, A. E. (2017). Performance assessment of teaching: Implications for teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 65(5), 372–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487114550475

- Kovjanic, S., Schuh, S. C., & Jonas, K. (2013). Transformational leadership and performance: An experimental investigation of the mediating effects of basic needs satisfaction and work engagement. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, 86(4), 543–555. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12022

- Kowalski, K. B., Aruldoss, A., Gurumurthy, B., & Parayitam, S. (2022). Work-from-home productivity and job satisfaction: A Double-layered moderated mediation model. Sustainability, 14(18), 11179. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811179

- Kramer, A., & Kramer, K. Z. (2020). The potential impact of the covid-19 pandemic on occupational status, work from home, and occupational mobility. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 119(May), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103442

- Ladergaard, H. J. (2011). ‘Doing power’ at work: Responding to male and female management styles in a global business corporation. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(1), 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.09.006

- Lai, F.-Y., Tang, H.-C., Lu, S.-C., Lee, Y.-C., & Lin, C.-C. (2020). Transformational leadership and job performance: The mediating role of work engagement. SAGE Open, 10(1), 215824401989908. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019899085

- Latkin, C. A., Edwards, C., Davey-Rothwell, M. A., & Tobin, K. E. (2017). The relationship between social desirability bias and self-reports of health, substance use, and social network factors among urban substance users in Baltimore, Maryland. Addictive Behaviors, 73, 133–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.05.005

- Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., & Sparrowe, R. T. (2000). An examination of the mediating role of psychological empowerment on the relations between the job, interpersonal relationships, and work outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 407–416. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.3.407

- Lonska, J., Mietule, I., Litavniece, L., Arbidane, I., Vanadzins, I., Matisane, L., & Paegle, L. (2021). Work–life balance of the employed population during the emergency situation of COVID-19 in Latvia. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 682459. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.682459

- Lopez-Zafra, E., Pulido-Martos, M., & Cortés-Denia, D. (2022). Vigor at work mediates the effect of transformational and authentic leadership on engagement. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 17127. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-20742-2

- Lord, R. G., Day, D. V., Zaccaro, S. J., Avolio, B. J., & Eagly, A. H. (2017). Leadership in applied psychology: Three waves of theory and research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(3), 434–451. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000089

- Macey, W. H., & Schneider, B. (2008). The meaning of employee engagement. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 1(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-9434.2007.0002.x

- MacKenzie, S. B., Podsakoff, P. M., & Rich, G. A. (2001). Transformational and transactional leadership and salesperson performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 29, 115–134.

- Markos, S., & Sridevi, M. S. (2010). Employee engagement: The key to improving performance. International Journal of Business & Management, 5(12), 89.

- Masa’deh, R., Obeidat, B. Y., & Tarhini, A. (2016). A Jordanian empirical study of the associations among transformational leadership, transactional leadership, knowledge sharing, job performance, and firm performance: A structural equation modelling approach. Journal of Management Development, 35(5), 681–705. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-09-2015-0134

- Masry-Herzalah, A., & Dor-Haim, P. (2022). Teachers’ technological competence and success in online teaching during the COVID-19 crisis: The moderating role of resistance to change. International Journal of Educational Management, 36(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-03-2021-0086

- Meng, F., Xu, Y., Liu, Y., Zhang, G., Tong, Y., & Lin, R. (2022). Linkages between transformational leadership, work meaningfulness and work engagement: A multilevel cross-sectional study. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 15, 367–380. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S344624

- Montgomery, D. C., Peck, E. A., & Vining, G. G. (2021). Introduction to Linear regression analysis. John Wiley & Sons.

- Mushtaque, I., Waqas, H., & Awais-E-Yazdan, M. (2022). The effect of technostress on the teachers’ willingness to use online teaching modes and the moderating role of job insecurity during COVID-19 pandemic in Pakistan. International Journal of Educational Management, 36(1), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-07-2021-0291

- Nagarajan, R., Alagiri, R. S., Reio, T. G., Elangovan, R., & Parayitam, S. (2022). The COVID-19 impact on employee performance and satisfaction: A moderated moderated-mediation conditional model of job crafting and employee engagement. Human Resource Development International, 25(5), 600–630. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2022.2103786

- Nahrgang, J. D., Morgeson, F. P., & Hofmann, D. A. (2011). Safety at work: A meta-analytic investigation of the link between job demands, job resources, burnout, engagement, and safety outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(1), 71–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021484

- Ng, T. W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (2009). Age, work experience, and the psychological contract. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(8), 1053–1075. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.599

- Nguni, S., Sleegers, P., & Denessen, E. (2006). Transformational and transactional leadership effects on teachers’ job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and organizational citizenship behavior in primary schools. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 17(2), 145–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243450600565746

- Nguyen, V. T., Siengthai, S., Swierczek, F., & Bamel, U. K. (2019). The effects of organizational culture and commitment on employee innovation: Evidence from Vietnam’s IT industry. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 13(4), 719–742.

- Özaralli, N. (2003). Effects of transformational leadership on empowerment and team effectiveness. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 24(6), 335–344. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730310494301

- Park, S., Kim, J., Park, J., & Lim, D. H. (2018). Work engagement in nonprofit organizations: A conceptual model. Human Resource Development Review, 17(1), 5–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484317750993

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Moorman, R. H., & Fetter, R. (1990). Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 1(2), 107–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/1048-9843(90)90009-7

- Przepiorka, A., Błachnio, A., Cudo, A., & Kot, P. (2021). Social Anxiety and social Skills via problematic smartphone use for predicting somatic symptoms and Academic performance at primary School. Computers & Education, 173(C), 104286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104286

- Rahmadani, V. G., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2022). Engaging leadership and work engagement as moderated by “diuwongke”: An Indonesian study. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 33(7), 1267–1295. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2020.1799234

- Rajagopalan, M., Abdul Sathar, M. B., & Parayitam, S. (2022). Self-efficacy and Emotion Regulation as moderators in the relationship between Learning strategies of students and Academic performance: Evidence from India. FIIB Business Review, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/23197145221113375

- Rich, B. L. Lepine, J. A. & Crawford, E. R.(2010). Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 53(3), 617–635.

- Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30(1), 91–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001

- Ruiz-Palomino, P., Linuesa-Langreo, J., & Elche, D. (2023). Team-level servant leadership and team performance: The mediating roles of organizational citizenship behavior and internal social capital. Business Ethics, the Environment & Responsibility, 32(S2), 127–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12390

- Ruiz-Palomino, P., & Zoghbi-Manrique de Lara, P. (2020). How and when servant leaders fuel creativity: The role of servant attitude and intrinsic motivation. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 89, 102537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102537

- Rüsch, N. & Corrigan, P. W.(2002). Motivational interviewing to improve insight and treatment adherence in schizophrenia. Psychiatric rehabilitation journal, 26(1), 23.

- Saks, A. M. (2006). Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(7), 600–619. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940610690169

- Satpathy, S., Patel, G., & Kumar, K. (2021). Identifying and ranking techno-stressors among IT employees due to work from home arrangement during covid-19 pandemic. Decision, 48(4), 391–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40622-021-00295-5

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi‐sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 25(3), 293–315. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.248

- Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015630930326