Abstract

The concept of country branding, also referred to as nation or place branding, involves the creation and management of a nation’s image and products to promote various aspects of its identity. This study conducted a systematic review of country branding studies based on articles published between 2010 and 2020. A total of 59 papers were obtained from electronic databases such as Scopus, search engines like Google Scholar, and publishers including Taylor and Francis, Emerald, Elsevier, and Wiley online, using a specific search criterion. Of the 59 articles, only 44 met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review. The results were organised using the theory, context, characteristics, and methods (TCCM) organising approach for systematic literature reviews. The study revealed two dominant research themes: ‘national branding campaign’ and ‘country of origin (COO). Most studies did not use any specific model and the qualitative method was the dominant research method used. The findings of this study provide a roadmap for understanding the literature on country branding and offer directions for future theory building.

IMPACT STATEMENT

The concept of country branding emerged as a way for countries to showcase their identity and appeal to tourists. Specifically, positive worldwide perceptions can be created by country branding, which in turn encourages exports and draws in visitors, investors, and new residents. Most importantly, nation branding persuades other actors to accept and adopt certain thoughts and behavior through the use of reasoning or argument. This research examines the literature on the topic of country branding, also known as nation branding, from 2010 to 2020. The study’s overarching goals are to advance scholarship on country branding and to inform branding efforts in different nations. With the themes that have been identified in this study, this research has the potential to better inform policymakers and practitioners on the nature of country branding. The importance of a nation’s brand was emphasized as a major factor for governments to think about.

SUBJECT:

- Technology; Computer Science; Management of IT; Social Sciences; Economics

- Finance

- Business & Industry; Business

- Management and Accounting; Marketing; Marketing Communications; Marketing Management; Retail Marketing; International Business; Research Methods in Management; Strategic Management; Tourism

- Hospitality and Events; Hospitality; Marketing Communications; Tourism; Tourism Marketing

1. Introduction

International marketing has grown into a complex and multifaceted discipline that encompasses a broad range of topics. This field is closely related to the broader subject of international business, which evolved from its initial focus on export operations and marketing to cover a wide range of issues. Prior international marketing studies have typically explored themes such as buyer behaviour, marketing strategy, product/brand policy, and external environmental variables (Donthu et al., Citation2020). The discipline has moved through a stage of development characterised by the maturation of its subject matter. According to Samiee and Chabowski (Citation2012), topics such as internationalisation, marketing strategy, performance, and relationship marketing have continued to be of interest to academics; however, in recent years, themes such as consumer behaviour, consumer hostility and ethnocentrism, country branding, and destination branding have gained greater significance. The field has expanded beyond its origins in international trade to address a variety of concerns, with branding issues including country branding becoming increasingly prominent. Indeed, country branding has been the focus of increasing research in recent years.

The term ‘country branding’ is often used interchangeably with ‘nation branding’ (Dinnie, Citation2016; Rasmussen & Merkelsen, Citation2012). According to Anholt (2005), national branding refers to a country’s identity, as perceived by an international audience. Other researchers, such as Mihalache and Vukman (Citation2005), define country branding as the use of a country’s image, products, and attractiveness to promote various aspects of a country’s identity and image to appeal to tourists and foreign direct investors. Bigi et al. (Citation2011) view country branding or nation branding as the primary tool marketers use to differentiate products and services. As cited in Bigi et al. (Citation2011), the American Marketing Association defines a brand as a name, symbol, design, sign, or a combination of these terms used to identify the goods and services of a seller in a competitive environment. Successful brands often create value for consumers and investors in the form of brand equity, which includes intangible assets such as customer preference, performance, social image, and trustworthiness as well as more tangible assets such as financial gains appraised from increases in firm value (Kotler and Gertner, Citation2002). Consumers attach emotional value to a product or service in their country (Shimp et al. Citation1993). Hence, a nation’s brand may either add or subtract perceived value from a purchase (Bigi et al., Citation2011).

The promotion of ‘country branding’ is a vital aspect of many nations’ efforts to establish effective governance and promote sustainability through the development of guidelines for environmentally friendly business practices, compliance, and sustainability rules (Frig & Sorsa, Citation2020; Varga, Citation2013). This form of branding serves as a valuable platform for nations to shape and influence their public image and contend with other countries in the global marketplace (Gudjonsson Citation2005). Of particular importance is the ability of country branding to persuade other stakeholders to adopt specific behaviours and beliefs based on rational arguments or evidence (Carstensen & Schmidt, Citation2016). Nation-branding also has the power to create a sense of national identity for domestic audiences by providing a tangible representation of their country’s culture, values, and history (Kaneva, Citation2011; O’Shaughnessy and O’Shaughnessy, Citation2000). For international audiences, a strong country brand can enhance a nation’s soft power, boosting its credibility, political influence, and ability to form strategic partnerships (Fetscherin & Toncar, Citation2010; Kaneva, Citation2011). Specifically, country branding can stimulate exports, attract tourists, investors, and immigrants, and create a positive international reputation (Fetscherin & Toncar, Citation2010; Stock, Citation2009). Given the numerous benefits associated with country branding, it is unsurprising that countries invest considerable resources in this area (Fetscherin & Toncar, Citation2010; Kaneva, Citation2011; Merkelsen & Rasmussen, Citation2015). Governments also rely on data from country brand indices to inform their decision-making processes (Merkelsen and Rasmussen, Citation2015).

In recent years, country branding has garnered significant attention as a critical element of public diplomacy and academic research (Varga, Citation2013). Despite the growth and impact of country branding, academic studies on this topic are still in their initial stages (Sun et al. Citation2016). To advance the field, a systematic approach to categorising the various contributions to country branding research is necessary. However, efforts to create a comprehensive and all-inclusive body of knowledge on this subject have been inadequate. This review aims to increase the comprehension of country branding by recognising the theories, methods, frameworks, and techniques used by prior studies on the topic. To understand the goal of this review, three specific objectives were set: (1) to identify the themes discussed in country branding research, (2) to identify the research methods used in country branding research, and (3) to identify areas for future research regarding country branding research. This approach was adopted because it helps both researchers and practitioners to gain an exhaustive overview of current research on country branding. Moreover, it evaluates the progression of knowledge in the field of country branding and reveals understudied and emerging areas. It aims to identify the themes, relationships, and characteristics discussed in country branding research, recognise the methods employed in country branding research, determine the areas and contexts that warrant further exploration. Furthermore, it provides information on the year of publication, level of analysis, and models and frameworks utilised.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The methodology section shows the process that was applied in carrying out this systematic review. It also touches on the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the selection of papers that were used in the final analyses. The next section presents and discusses the results of the study. This is followed by discussion on directions for future research. The final section concludes presents the limitations and recommendations for future research in this field of study.

2. Methodology

A systematic and structured approach was employed to identify the relevant articles for the literature review. Initially, academic databases were selected, and relevant papers were extracted using specified keywords. Subsequently, the papers were scrutinised to ensure that only related journals were included, thereby avoiding exclusion of pertinent or relevant papers. The TCCM framework for conducting domain-based reviews (Paul & Rosado-Serrano, Citation2019) was used as the organising framework for this systematic review. Theories refer to the diverse theoretical perspectives employed to elucidate the linkages between constructs, while context pertains to the research setting. Characteristics relate to the elements of a construct and its relationship with other variables, and methods encompass the specifics of the research design, approach, and analytical tools. This framework was chosen because of its comprehensibility and versatility in enabling researchers to identify and organise the relevant details of theories, data sources, journals, contexts, themes, and methods (Paul et al., Citation2023). In addition to the conventional dimensions of the TCCM framework, the authors also assessed trends in yearly publications, levels of analysis, and publication outlets to provide a more comprehensive view of the literature.

2.1. Data collection

The search for articles was limited to publications published between 2010 and 2020, with a focus on journals. Consequently, other document types such as books, theses, magazines, conference proceedings, notes, and reports were excluded from the review process. Data were obtained from the Scopus and Web of Science databases, which contain the most popular journal quality lists and spans across multiple disciplines. This enabled researchers to access high-quality journal articles.

Articles were also retrieved from publishers such as Emerald, Elsevier, Wiley, Springer, and Sage, as well as from search engines such as Google Scholar. Google Scholar was selected because it quickly indexes a wide range of scholarly publications and is freely accessible (Paul et al. Citation2021). The search was limited to papers containing the keywords ‘country branding’ OR ‘nation branding’, which are common terminologies in national branding. We selected these two keywords to ensure manageability. The figure below shows the frequency and trends of publications related to country branding. Articles were manually examined to identify relevant contributions, and after removing duplicates, 44 relevant papers were obtained.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This study was restricted to articles published between 2010 and 2020. The authors opted for this timeframe for several reasons. First, the systematic literature review aimed to synthesise current evidence on country branding, and thus, limiting the search to this period was necessary. Second, country branding is a rapidly evolving field and research findings can quickly become outdated. By limiting the search to a 10-year range, the study ensured that it focused on the more recent literature. Third, limiting the review to a 10-year range allowed for timely completion of the study. Finally, older articles may not accurately reflect current issues, technologies, or practices, which could limit the generalisability of the findings.

Furthermore, only papers with full-text in English were considered. The inclusion of journal articles was based on their rigorous peer-review process compared with other document types, such as conference papers, books, book chapters, reviews, editorials, and doctoral theses (Herrera-Franco et al., Citation2020). Additionally, only English-language journal articles were considered because English is the most widely used language in scientific publications (Cisneros et al., Citation2018). This study excluded duplicate studies from the same study.

2.3. Data synthesis

The primary aim of this stage was to develop extraction forms that accurately captured the information from the selected papers. Microsoft Excel spreadsheets and words were utilised to integrate the relevant data into various categories, including trends in publication, research themes, methods and theories, level of analysis, countries, and publication outlets.

3. Findings and discussions

The subsections presented in this section are theories, research contexts, characteristics, methods, publication outlets, level of analysis, and publication trends.

3.1. Underlying theories

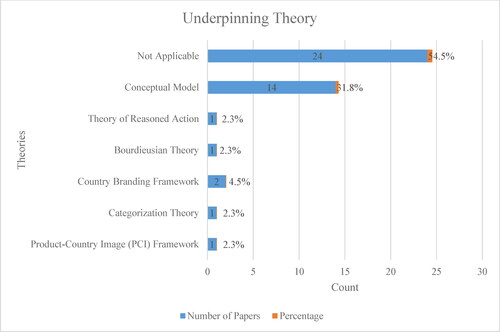

To gain a comprehensive understanding of country branding, we conducted a review of the theoretical foundations employed by the authors in their studies. As depicted in , the theoretical underpinnings of these studies encompass consumer intentions, projection of a particular image, social identity, social influence, and social interaction. A detailed analysis of the papers revealed six fundamental lenses serving as guidelines for conducting the studies. These lenses include the ‘Product-Country Image (PCI) Framework’, ‘Categorization Theory’, ‘Country Branding Framework’, ‘Bourdieu Sian Theory’, ‘Theory of Reasoned Action’, and ‘Conceptual Model’. Studies that did not utilize any theoretical framework were classified as ‘Not applicable’. It is worth noting that most of the studies, amounting to 24 (54.5%) papers, did not employ theories. Conversely, 14 (31.8%) studies utilised conceptual models. The remaining studies used theories such as the ‘Product-Country Image (PCI) Framework’, ‘Categorization Theory’, ‘Country Branding Framework’, ‘Bourdieu Sian Theory’, and ‘Theory of Reasoned Action’.

For instance, Mody et al. (Citation2017) leveraged the Product-Country Image (PCI) framework to develop a model to examine tourists’ loyalty towards responsible tourism operators by integrating two streams of literature. Similarly, Sun et al. (Citation2016) utilised the country branding framework to respond to the call for increased research on how countries can employ their institutions and resources to enhance their globalisation efforts. They specifically investigated the interrelationships between country institutions and resources, country image, and exports, based on institutional theory and resource advantage theory. However, despite the prevalence of the traditional Product-Country Image framework and related concepts such as the country branding framework, no theoretical perspective has gained dominance. There is a notable lack of a clear conceptualisation of country branding, leading to the proliferation of numerous divergent theoretical perspectives that originate from diverse disciplines, including psychology and marketing.

3.2. Context

The studies included in this research were categorized based on their geographical context, which was referred to as the ‘Geographical Context of the Study’. The results shown in . indicated that most of the studies were conducted in multiple countries and were classified as ‘Cross-Country’, with China, Korea, Denmark and Finland, Romania and Bulgaria, and the United States, the United Kingdom, and Spain. Studies that did not focus on a specific country were classified as ‘Not applicable’, while the remaining countries were identified. In the case of the three leading countries, 10 (22.7%) were classified as cross-country, six (13.6%) were not applicable, and four (9.1%) were from India. However, there is a noticeable lack of literature on the African context. Many studies have been conducted on emerging and developing markets in Asia. Nevertheless, emerging markets differ significantly in terms of their characteristics, culture, and perceptions. Therefore, the scarcity of literature on other geographical contexts represents a significant limitation of existing studies as it does not account for potential differences in geographical contexts, which may limit the generalisability of the findings.

3.3. Characteristics

The primary objective of this section is to investigate the knowledge landscape of country branding using research themes. The following themes were identified: factors affecting branding image, renaming/rebranding, talent retention, public diplomacy, consumer learning of brands, luxury branding, international marketing, internationalisation, authenticity of brands, football marketing, purchase intention, soft power, online engagements, competitive advantage, branding strategy, brand documents and campaign artefacts, national branding campaigns, country of origin (COO), and cultural identity. Additionally, a theme called ‘general’ was included, which represents articles that do not relate to any specific research theme but aim to provide an overview. As shown in , the dominant themes were national branding campaigns and country of origin (COO), with eight (18%) papers each, followed by branding strategy and the theme categorised as ‘general’, with five (11%) papers each. For instance, Brodie and Benson-Rea (Citation2016) provided a strategic perspective that integrates extant views of COO branding based on identity and image with a relational perspective based on a process approach to developing collective brand meaning. Therefore, given the significance of COO as a theme for study by many researchers in the field of country branding, it can be inferred that most scholars are interested in exploring the places where goods are made, grown, produced, or from which services are supplied. Although the research identified various conceptualisations of country branding, it also found evidence that country-of-origin perceptions have a significant influence on consumer behaviour.

Table 1. Country context in which the studies were conducted.

Table 2. Emerging themes.

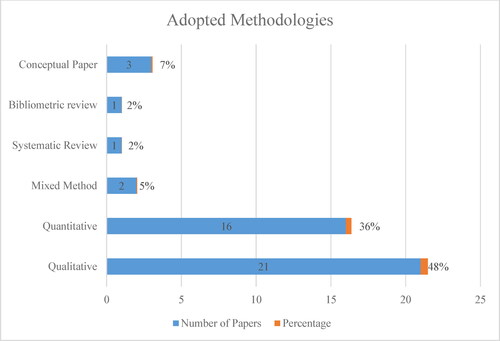

3.4. Methods

The analysis of the studies included in the study revealed six distinct methodologies: qualitative, quantitative, mixed-method, systematic reviews, bibliometric reviews, and conceptual studies. Of these, qualitative methodology was the most used, accounting for 21 (48%) studies, followed by quantitative methodology with 16 (36%), mixed method with seven (17.9%), systematic reviews with two (5%), and bibliometric reviews and conceptual studies with one (2%) each. These findings indicate that most of the studies utilised a quantitative methodology, followed by a qualitative approach. Tiberghien and Garkavenko (Citation2013) employed a qualitative approach in their exploratory study to record and evaluate the perceptions of community members, policymakers, and tourism developers regarding the authenticity of eco-cultural tours in Central Kazakhstan. This study aims to understand how authenticity can contribute to Kazakhstan’s position as a tourism destination and strengthen its brand equity in the international tourism market. These findings suggest that conventional research approaches are commonly used in country branding research. However, there are opportunities to incorporate sophisticated methods, such as sentiment analysis and text mining, into country-branding studies.

illustrates the distribution of studies based on the research methods employed.

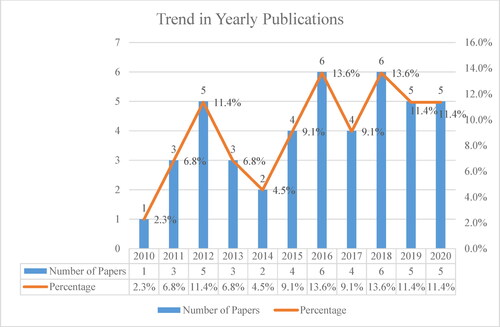

3.5. Trend in Yearly publications

The classification of papers by year of publication indicated a declining trend in the number of publications over the past decade (2010-2020). Specifically, 2010 had the lowest number of publications, while 2016 and 2018 had the highest number of publications. The number of publications during this period varied between three and four. However, it is important to recognise that the papers utilised in the analysis were collected until November 2020, resulting in an increase in the number of papers in December of that year. shows the number of papers published per year.

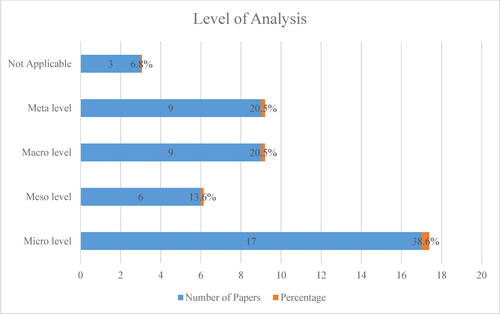

3.6. Level of analysis

The classification of the studies revealed four levels of analysis, as shown in . These levels comprised micro (individual level unit of analysis), meso (organizational level unit of analysis), macro (national or country-level unit of analysis), and meta (regional, cross-country, or global level unit of analysis). As illustrated in the figure, the majority of the papers, 17 (38.6%) were micro-level papers. For instance, Che-Ha et al. (Citation2016) investigated the elements of country branding from the perspective of a country’s citizens at the micro level. Macro- and meta-level papers comprised nine (20.5%) papers each. Six (13.6%) papers were classified at the meso level. The remaining three (6.8%) papers were categorised as ‘Not Applicable’ and could not be assigned to any of the four previously mentioned units of analysis.

3.7. Publication outlets

This research sought to determine the journals in which the articles were published, and the top ones identified were the European Journal of Cultural Studies and International Marketing Review, with three papers (6.8%), followed by the Journal of Vacation Marketing, Asian Marketing Journal (AMJ), Journal of Business Research, and Journal of Consumer Behaviour, each with two papers (4.5%). The results are presented in . It is not surprising that the European Journal of Cultural Studies and International Marketing Review, as well as the Journal of Vacation Marketing, are major outlets for authors to publish their work given the nature of the topic, which focuses on country and cultural identity, and the observation of tourism across international jurisdictions.

Table 3. Publication outlets.

4. Identified gaps for future research

The research papers that have been evaluated reveal several areas that require further investigation by future researchers. In this section, these gaps are examined and discussed in relation to the four themes identified. This analysis will be beneficial in directing future researchers to study country branding. Table A1 in the appendix summarizes the findings and research gaps in the papers reviewed.

4.1. Theories

Regarding conceptualising country branding, Brodie and Benson-Rea (Citation2016) presented a strategic perspective that integrates prevailing views on COO branding, which are rooted in identity and image, with a relational perspective grounded in a process-based approach to developing collective brand meaning. Although their study provides empirical evidence to support the proposed theoretical framework, it is limited to a specific industry within a country and does not encompass the national branding of the entire country. Therefore, the authors suggest that further research is needed to explore the application of this framework to country branding. They proposed that this could be achieved through a case study that focuses on the ‘New Zealand story’ and the shift from branding based on identity and image to collective branding processes that facilitate the co-creation of meaning within New Zealand’s industries and export market networks. Moreover, the authors recommend conducting research to develop a set of comparative country case studies.

4.2. Exploring other country context studies and populations

Further research could explore other contexts, including corporate branding, which provides a strategic perspective for an enterprise and serves as an umbrella brand for its product brands (Balmer & Gray, Citation2003). Vecchi et al. (Citation2020) also proposed a framework suitable for assessing how a nation-branding campaign could promote cultural identity. They called for future research that relies on rigorous research into branding to be effective and achieve the desired outcome. Their study focused only on Colombia; therefore, to fully assess the robustness of their proposed framework, it would be useful to replicate the analysis across a broader range of countries and address a broader range of polarisation issues. He et al. (Citation2020) also examined public opinion on China, as reflected by the questions and answers on social media using content analysis. However, their study focused on only one platform and the subjects were limited to one country. They suggested further studies that examine the condition of other social media platforms (such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram) and the use of countries other than China for comparative analysis. Williams et al. (Citation2012) explored the application of the renaming process model, which illustrates the key components that impact the organization brand renaming process, in the context of the renaming of the African Higher Educational Institution (HEI) Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST). However, they suggest the need to collect relevant data from all stakeholders in various African countries to explore renaming efforts that can strengthen brand equity within those contexts.

Exploration of the branding strategies employed by countries in conflict warrants further investigation. One study that has shed light on this issue is Lim et al. (Citation2022), who examined the impact of the Russia-Ukraine War on businesses and society. The authors find that brand associations play a crucial role in understanding the effects of war on business. They observed that several nations engaged in corporate social responsibility initiatives to enhance their brand image by supporting the country that is being invaded or dissociated from the invader through divestment. This finding suggests that maintaining a positive brand image is crucial during a crisis. Future research should examine the implications of these activities for both businesses and consumers.

4.3. Characteristics

The recent trend of de-internationalisation in global businesses warrants further investigation, particularly in relation to its association with country branding. Although there is extensive literature on internationalisation, there is a scarcity of research on country image in the context of de-internationalisation, and the defining acts and characteristics of such acts are not well understood. Therefore, it is crucial for future studies to address this knowledge gap.

The global business environment has become increasingly complex, volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous, posing challenges for firms, and prompting them to evaluate and adopt devolutionary measures in their global operations, such as overseas divestment and export withdrawals. This can occur in a specific foreign market, such as the China-US trade war, or across international markets, such as the border closure and industry shutdown caused by COVID-19. Therefore, it is important to assess how de-internationalisation affects brand management.

Future studies can explore how nation-branding impacts innovative marketing plans in the context of major crises and examine B2B trajectories in relation to brand image problems during such crises. This can provide valuable insights into the usefulness of various elements of country branding in achieving transformative marketing objectives before, during, and after a major crisis.

4.4. Methods

Regarding the adoption of other methodologies and the use of larger sample sizes, researchers such as Andéhn et al. (Citation2016), in their study that tested the relative evaluative relevance of product category with respect to estimates of brand equity across a variety of product categories, invite future research that replicates the findings of their study using population stimuli other than Sweden. In their view, such a study would provide some indication of the robustness of their results. Che-Ha et al. (Citation2016) also examined the elements of country branding from the perspective of Malaysian citizens. Their findings indicate that Malaysia can be portrayed favourably through exports, human capital, culture and heritage, and political efforts. While some elements (human capital, culture, heritage, and politics) are important in fostering positive emotions among its citizens, others (exports, human capital, and politics) are considered as key tools to build competitive advantage. They call for the use of a comprehensive sample that may uncover other factors that are important in building a country’s brand. Hence, in their view, there is a need for future research to include views from returning visitors and tourists to Malaysia to strengthen the factors that drive country branding. They also propose future research that considers qualitative approaches, such as face-to-face interviews, to explore in-depth studies on the aspects of country branding related to emotions, which may not have surfaced using the self-administered survey questionnaire.

5. Conclusion

Over the last decade, country branding has developed with increasing marketing strategies around the world. The goal of this study was to provide a systematic literature review based on an analysis of 44 journal publications on country branding since 2010. To understand country branding, three research objectives were set: (1) to identify the themes discussed in country branding research, (2) to identify the research methods used in country branding research, and (3) to identify areas for future research regarding country branding research. Additionally, the study presents the year in which the papers were published, levels of analysis, and models and frameworks used in the studies.

Regarding the themes that have been discussed regarding country branding, the three dominant themes identified are on ‘national branding campaign’ and ‘country of origin (COO)’ followed by ‘branding strategy’ and ‘general’ discussions on country branding. Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods approaches have been identified for the research methods used in country branding research. Systematic reviews, bibliometric analyses, and conceptual studies were also conducted. However, qualitative methods are dominant. Regarding the areas for future research on country branding, as discussed in the papers, the findings point to three themes. The first theme is for researchers to use other methodologies and study country branding using large sample sizes that can provide proper generalisation. The second theme is for future research that explores other country-context studies and populations, while the third is for future research to develop models or adapt models, frameworks, and theories to country branding research.

Analysis of the data demonstrates that the most significant number of papers were published in 2016 and 2018. However, it is important to note that the data collection was completed by November 2020, which indicates that 2020 experienced an increase in the number of published papers. The studies were conducted at various levels, including micro-, meso-, macro-, and meta-levels, with most studies conducted at the micro-level (individual level). The majority of studies were not conducted under the framework of any theoretical model or theory, although some known theories or models have been used. These include the product-country image (PCI) framework, categorisation theory, country branding framework, Bourdieu–Sian theory, and the theory of reasoned action. Many of the studies were conducted across multiple countries (cross-country). In addition, most papers were published in the European Journal of Cultural Studies. The findings of this study provide valuable insights into the current state of research in cultural studies.

5.1. Implications

This study has several implications worth considering. First, it adds to the existing body of literature on country branding by making significant contributions to the field. Second, it provides a solid foundation for future research by identifying gaps in existing research. Policymakers and practitioners can use the findings of this study to better understand the nature of country branding and the themes that have been identified. Furthermore, this study highlights areas that require further exploration, such as the use of theories and methodologies in country branding research. However, there is a noticeable lack of research on country branding, which is supported by frameworks, theories, and research models. Most studies conducted in this area have not used any such frameworks or models, which is a significant gap that needs to be addressed in future research.

5.2. Limitations

This study, like many others, had certain limitations. First, while the review was comprehensive, it was not all-encompassing, as some potentially relevant studies may have been omitted because of the databases used and filtering process. Second, the research only considered journal articles and excluded other sources, such as conference proceedings, monographs, dissertations, chapters, and books. Third, the review did not conduct a bibliometric or scientometric analysis, which would have enabled a more detailed analysis of the intellectual structure of country-branding research. Fourth, owing to the constraints of the research sample size, the themes identified were not meant to be definitive or mutually exclusive. Despite these limitations, this study identified gaps in the country-branding literature and suggested new directions for future research.

BIO Information.docx

Download MS Word (13 KB)PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT.docx

Download MS Word (11.8 KB)Profile of Authors.docx

Download MS Word (246.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ahmed Tijani

Ahmed Tijani works at Minerals Commission, Ghana. His research interests are corporate governance, relationship marketing, development communication and extractive industry’s policy, regulation and management. He is a PhD candidate at the University of Professional Studies and holds an MBA in corporate governance, MA in development communication, a BSc in banking and finance and an HND in marketing.

Mohammed Majeed

Mohammed Majeed is a Lecturer (PhD) at Tamale Technical University (TaTU), Tamale-Ghana. He is the current Head of Department of Marketing in TaTU. His current research interest includes digital marketing, co-creation, branding, green marketing and sustainability. Majeed holds Doctor of Business Administration (DBA), MPhil and MBA Marketing. Majeed has also published with Taylor & Francis, Springer Nature, Palgrave McMillan, and Emerald.

Kwame Simpe Ofori

Kwame Simpe Ofori is currently a PhD student at the School of Management and Economics, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China. He has taught courses in areas of Finance and Telecommunications Engineering. He holds a Doctorate Degree in Finance. His research interests are in the areas of consumer behaviour, technology adoption and trust in online systems and PLS path modelling. His papers have appeared in Information Technology and People, Marketing Intelligence and Planning, International Journal of Bank Marketing, Total Quality Management and Business Excellence, and Society and Business Review.

Aidatu Abubakari

Aidatu Abubakari is a PhD candidate at the Department of Marketing and Entrepreneurship, University of Ghana. She is an assistant lecturer at Lakeside University College, Ghana. Aidatu holds an MPhil marketing. Her research interests include sustainability, Tourism marketing and services marketing.

References

- Andéhn, M., Nordin, F., & Nilsson, M. E. (2016). Facets of country image and brand equity: Revisiting the role of product categories in country-of-origin effect research. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 15(3), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1550

- Balmer, J. M., &Gray, E. R. (2003). Corporate brands: what are they? What of them?. European Journal of Marketing, 37(7/8), 972–997. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560310477627

- Bigi, A., Plangger, K., Bonera, M., & Campbell, C. L. (2011). When satire is serious: how political cartoons impact a country’s brand. Journal of Public Affairs, 11(3), 148–155. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.403

- Brodie, R. J., & Benson-Rea, M. (2016). Country of origin branding: An integrative perspective. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 25(4), 322–336. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-04-2016-1138

- Carstensen, M. B., &Schmidt, V. A. (2016). Power through, over and in ideas: conceptualizing ideational power in discursive institutionalism. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(3), 318–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1115534

- Che-Ha, N., Nguyen, B., Yahya, W. K., Melewar, T. C., & Chen, Y. P. (2016). Country branding emerging from citizens’ emotions and the perceptions of competitive advantage: The case of Malaysia. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 22(1), 13–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766715586454

- Cisneros, L., Ibanescu, M., Keen, C., Lobato-Calleros, O., & Niebla-Zatarain, J. (2018). Bibliometric study of family business succession between 1939 and 2017: mapping and analyzing authors’ networks. Scientometrics, 117(2), 919–951. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2889-1

- Deloitte. (2017). Deloitte Football Money League. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/uk/Documents/sports-business-group/deloitteuk-sport-football-money-league-2017.pdf

- Dinnie, K. (2016). Nation Branding: Concepts, Issues, Practice (2nd ed.). Elsevier.

- Donthu, N., Kumar, S., & Pattnaik, D. (2020). Forty-five years of Journal of Business Research: A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.10.039

- Erdem, T. (1998). An Empirical Analysis of Umbrella Branding. Journal of Marketing Research, 35(3), 339–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379803500305

- Erdem, T.,Zhao, Y., &Valenzuela, A. (2004). Performance of store brands: A cross-country analysis of consumer store-brand preferences, perceptions, and risk. Journal of Marketing Research, 41(1), 86–100. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.41.1.86.25087

- Fetscherin, M., & Toncar, M. (2010). The effects of the country of brand and the country of manufacturing of automobiles. International Marketing Review, 27(2), 164–178. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651331021037494

- Frig, M., & Sorsa, V. P. (2020). Nation branding as sustainability governance: A comparative case analysis. Business & Society, 59(6), 1151–1180. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650318758322

- Gudjonsson, H. (2005). Nation branding. Place Branding, 1(3), 283–298. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.pb.5990029

- He, L., Wang, R., & Jiang, M. (2020). Evaluating the effectiveness of China’s nation branding with data from social media. Global Media and China, 5(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/2059436419885539

- Herrera-Franco, G., Montalván-Burbano, N., Carrión-Mero, P., Apolo-Masache, B., & Jaya-Montalvo, M. (2020). Research Trends in Geotourism: A Bibliometric Analysis Using the Scopus Database. Geosciences, 10(10), 379. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences10100379

- Kaneva, N. (2011). Nation branding: Toward an agenda for critical research. International Journal of Communication, 5, 25.

- Kotler, P., & Gertner, D. (2002). Country as brand, product, and beyond: A place marketing and brand management perspective. Journal of Brand Management, 9(4), 249–261. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540076

- Lim, W. M., Chin, M. W. C., Ee, Y. S., Fung, C. Y., Giang, C. S., Heng, K. S., Kong, M. L. F., Lim, A. S. S., Lim, B. C. Y., Lim, R. T. H., Lim, T. Y., Ling, C. C., Mandrinos, S., Nwobodo, S., Phang, C. S. C., She, L., Sim, C. H., Su, S. I., Wee, G. W. E., & Weissmann, M. A. (2022). What is at stake in a war? A prospective evaluation of the Ukraine and Russia conflict for business and society. Global Business and Organizational Excellence, 41(6), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/joe.22162

- Medlin, C. J. (2006). Self and collective interest in business relationships. Journal of Business Research, 59(7), 858–865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.01.020

- Merkelsen, H., & Rasmussen, R. K. (2015). The construction of Brand Denmark: A case study of the reversed causality in nation brand valuation. Valuation Studies, 3(2), 181–198. https://doi.org/10.3384/VS.2001-5992.1532181

- Mihalache, S., & Vukman, P. (2005). Composition with country and corporate Brands [Doctoral dissertation]. Linköping University.

- Mody, M., Day, J., Sydnor, S., Lehto, X., & Jaffé, W. (2017). Integrating country and brand images: Using the product—Country image framework to understand travellers’ loyalty towards responsible tourism operators. Tourism Management Perspectives, 24, 139–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.08.001

- O’Shaughnessy, J., & O’Shaughnessy, N. J. (2000). Treating the nation as a brand: Some neglected issues. Journal of Macromarketing, 20(1), 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146700201006

- Paul, J., & Rosado-Serrano, A. (2019). Gradual internationalization vs born-global/international new venture models: A review and research agenda. International Marketing Review, 36(6), 830–858. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-10-2018-0280

- Paul, J., Lim, W. M., O’Cass, A., Hao, A. W., & Bresciani, S. (2021). Scientific procedures and rationales for systematic literature reviews (SPAR-4-SLR). International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(4), O1–O16. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12695

- Paul, J., Alhassan, I., Binsaif, N., & Singh, P. (2023). Digital entrepreneurship research: A systematic review. Journal of Business Research, 156, 113507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.113507

- Rasmussen, R. K., & Merkelsen, H. (2012). The new PR of states: How nation branding practices affect the security function of public diplomacy. Public Relations Review, 38(5), 810–818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2012.06.007

- Samiee, S., & Chabowski, B. R. (2012). Knowledge structure in international marketing: a multi-method bibliometric analysis. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(2), 364–386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0296-8

- Shimp, T. A., Samiee, S., & Madden, T. J. (1993). Countries and their products: a cognitive structure perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 21(4), 323–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02894524

- Stock, F. (2009). Identity, image and brand: A conceptual framework. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 5(2), 118–125. https://doi.org/10.1057/pb.2009.2

- Sun, Q., Paswan, A. K., & Tieslau, M. (2016). Country resources, country image, and exports: country branding and international marketing implications. Journal of Global Marketing, 29(4), 233–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2016.1211782

- Tiberghien, G., & Garkavenko, V. (2013). Authenticity and eco-cultural tourism development in Kazakhstan: A country branding approach. European Journal of Tourism, Hospitality and Recreation, 4(1), 29–43.

- Varga, S. (2013). The politics of nation branding: Collective identity and public sphere in the neoliberal state. Philosophy & Social Criticism, 39(8), 825–845. https://doi.org/10.1177/0191453713494969

- Vecchi, A., Silva, E. S., & Angel, L. M. J. (2020). Nation branding, cultural identity and political polarization–an exploratory framework. International Marketing Review, 38(1), 70–98. ISS N 0 2 6 5-1 3 3 5 https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-01-2019-0049

- Williams, R., Jr, Osei, C., & Omar, M. (2012). Higher education institution branding as a component of country branding in Ghana: Renaming Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 22(1), 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2012.705795

Appendix

Table A1. Systematic literature review on published journal articles.