Abstract

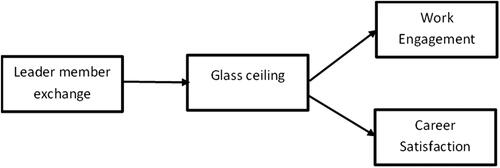

The glass ceiling still exists in the workplace, where women face barriers to achieving a higher career path. One of the obstacles comes from the organizational environment in the form of gender stereotypes, which make it increasingly difficult for women to occupy managerial positions. In this case, leaders play an important role in building relationships with subordinates to overcome the glass ceiling issue. Not many studies analyze gender discrimination in the workplace from the perspective of social exchange between leaders and subordinates. This study aimed to analyze the effect of leader-member exchange on career satisfaction and work engagement through the glass ceiling. Data were collected from 469 female employees working in various companies in Indonesia. Convergent and discriminant validity were conducted to validate the measurement of variables, and the partial least squares were used to test the hypotheses. Leader-member exchange has been shown to have a negative effect on the glass ceiling. Similarly, the glass ceiling has a negative effect on career satisfaction and work engagement. In addition, the glass ceiling mediates the effect of leader-member exchange on career satisfaction and work engagement. Given these results, leaders need to build high quality relationships with employees to prevent a glass ceiling in the workplace.

IMPACT STATEMENT

Discrimination against women continues to be an important issue in the workplace, with women facing barriers to leadership positions. Glass ceilings at work are often elusive. In this case, the leader’s role becomes crucial. Leaders are responsible for building quality relationship with subordinates, and the quality of the relationship can determine career success, including overcoming career barriers for women. If women feel inhibited from reaching managerial positions, this will affect their career satisfaction and work engagement. This research provides an understanding of how the quality of the leader-subordinate relationship may impact the glass ceiling experienced by women and how it affects career satisfaction and work engagement. Therefore, it is necessary to maintain high quality relationships between leaders and subordinates in the workplace, as this can protect women from various forms of discrimination.

Reviewing Editor:

Introduction

Women are still struggling to attain high-level managerial positions in the workplace, which is a universal phenomenon considering the obstacles they often encounter (Sharma & Kaur, Citation2019). According to social role theory (Eagly, Citation1987), sometimes women might be questioned about their capacity for leadership roles or when they try to thrive professionally as a result of being given feminine attributes (communal or expressive) rather than masculine attributes (independent, assertive, or competent). Compared to men, women generally occupy lower levels of leadership roles (Mohammadkhani & Gholamzadeh, Citation2016). Males outnumber females, specifically in holding middle to senior management positions (Dezsö & Ross, Citation2019; Ng & Sears, Citation2017). This phenomenon refers to the glass ceiling, which is a metaphor used by females to describe obstacles along their career paths. Females can perceive the glass ceiling, but identifying the phenomenon can often be difficult (Blessie & Supriya, Citation2018). The glass ceiling metaphor is used to refer to discrimination that hinders career promotions for women in organizations (Bendl & Schmidt, Citation2010). Kiaye and Singh (Citation2013) define the glass ceiling as an invisible barrier, an impassable obstacle that prevents females from reaching senior management positions. Until the present time, the glass ceiling remains a problem that is encountered by organizations in both developed and developing countries (Khalid & Sekiguchi, Citation2019).

A number of studies have explained the phenomenon of the glass ceiling in the workplace, such as discrimination, bias, and the insufficiency of mentoring and networking (Cook & Glass, Citation2014). Jain and Mukherji (Citation2010) also add psychological factors as impediments that prevent many females from gaining high-level leadership roles. Sex categorization and gender stereotypes lead decision-makers to view females as less capable and less competent, while in-group favoritism causes males to select other males for appointments and promotions to higher positions (Glass & Cook, Citation2016). Powell and Butterfield (Citation2003) further suggest that the glass ceiling includes a range of impediments, such as personal impediments, organizational impediments, and social impediments, which are encased by culture and society. In many communities, there is a common belief that women should be at home and they do not need to have jobs and develop their careers. If females do not adhere to such beliefs, they will not receive acceptance and be valued. That condition hinders women in their effort to progress in their careers by creating beliefs about the glass ceiling (Blessie & Supriya, Citation2018). These beliefs can impede employees’ overall performance and organizational success. Therefore, understanding beliefs about the glass ceiling within organizational contexts is still encouraged (Sarika, Citation2015).

Research by Smith et al. (Citation2012) has proven that beliefs about the glass ceiling significantly affect career success among females. According to Srivastava et al. (Citation2020), while females’ participation in the workforce has been on the increase and they demonstrate experience and readiness for taking managerial roles, their career paths do not allow them opportunities for holding managerial positions. This phenomenon indicates that females still have to struggle in their careers to attain higher positions, resulting in the belief that a glass ceiling is present in the workplace and affects career satisfaction among females. Further, a study by Balasubramanian and Lathabhavan (Citation2017) has demonstrated that beliefs about a glass ceiling are an important determining factor for work engagement. Thus, the extent to which females perceive the glass ceiling will affect the work engagement observed within an organization. Previous studies have also explained the relationship between the glass ceiling and work engagement and the impact of the glass ceiling on work engagement, which suggests unfair treatment received by females in the workplace and females’ perceptions of discrimination, which negatively affect their work engagement (Kim, Citation2015; Sia et al., Citation2015).

In addition to the impact of the glass ceiling on various work-related outcomes, beliefs about the glass ceiling can be induced by the quality of leader-member exchange (LMX) within the relationship between supervisors and employees. It is a fundamental principle in LMX that supervisors can develop varied degrees of quality in their relationship with employees, which results in differing formal and informal appraisals among employees (Jung & Takeuchi, Citation2016). Other studies have also pointed out the relationship between employers’ support and individual career success, and LMX quality is a crucial determining factor for subjective individual success among employees (Byrne et al., Citation2008; Harris et al., Citation2009). However, there remain studies that focus on the differences between men and women in perceiving career success in terms of the social exchange between leaders and employees (Jung & Takeuchi, Citation2016). Thus, this research aims to analyze the impact of LMX on the perceived glass ceiling and the impact this has on career satisfaction and work engagement.

In Indonesia, the glass ceiling has been continuously perceived by females at work. The Indonesian National Workforce Survey (BPS-Statistics Indonesia, Citation2018) indicates 51.88% of female participation in the workforce, which is lower than male participation in the workforce at 82.69%. The level of participation in the workforce reflects the proportion of the workforce population compared to the working-age population. The higher level of participation in the workforce for males compared to females in Indonesia is due to the predominance of males as breadwinners. Besides, the other contributing factor to the comparatively smaller female workforce population is the belief that females should be fully responsible for managing households and gender discrimination, as indicated by the Indonesian Ministry of Women Empowerment and Child Protection (Kementerian Pemberdayaan Perempuan dan Perlindungan Anak, Citation2019). Data from BPS-Statistics Indonesia (Citation2018) also point out that generally, the average salary of female employees is lower than that of their male colleagues, both in urban and rural areas.

A survey by the McKinsey Global Institute (McKinsey, Citation2018) further indicates that in Indonesia, gender inequality in the workplace is identified as high, as shown by a score of 0.52. This result reflects the unfair treatment of women in securing employment and receiving proper wages, skills, and opportunities to demonstrate work productivity and attain managerial positions. In terms of managerial positions, this survey by the McKinsey Global Institute (Citation2018) has placed Indonesia as a country with a high level of gender inequality, with a score of 0.30. This phenomenon suggests that Indonesian women are still confronted with a glass ceiling in the workplace. In fact, this phenomenon is also experienced by the millennial generation in Indonesia. Based on the data from Kementrian Pemberdayaan Perempuan dan Perlindungan Anak (Indonesian Ministry of Women Empowerment and Child Protection, Citation2019), the female millennial generation’s participation in the workforce is only around 50% compared to the male millennial generation, which reaches more than 80%. Thus, the present research aims to examine the perceived glass ceiling among Indonesian female employees who work in various industries and the impact of the perceived glass ceiling on work-related outcomes.

Literature review and hypothesis development

Social role theory and role congruity theory

The social role theory proposed by Eagly, (Citation1987) posits that prevalent gender stereotypes stem from the gender division of labor within society, in which women are often assumed to be at home, whereas men are often assumed to be outside of domestic responsibilities. This assumption emerges from stereotypes associating agency with men and communion with women. The agency associated with men pertains to characteristics like independence, assertiveness, and competence. Women develop characteristics that display communal or expressive behavior involving being nice, unselfish, and expressive, suppressing their aggression, and are often labeled as lacking the capacity to succeed as leaders (Isaac et al., Citation2012). When gender stereotypes are prominent in a group due to mixed-sex membership or a task or situation that is culturally linked with one gender, stereotypes impact behaviou directly through members’ expectations of one another’s behaviour.

Social role theory suggests that gender stereotypes arise because men and women act according to social roles, often separated by gender (Eagly, Citation1987). Within an organizational context, social role theory explains how managers expect individuals to behave and act according to their social role (Skelly & Johnson, Citation2011). Consequently, some managers may not promote women to managerial positions in their organizations because they believe women lack masculine characteristics (Baker, Citation2014). Based on this theory and stereotypical roles, job roles become more differentiated, although it is unlikely that groups will be equally represented in job roles (Kiser, Citation2015; Koenig & Eagly, Citation2014).

In the workplace, stereotypes can be very detrimental to career advancement, perceptions of leaders, and perceived qualities of each gender (Kiser, Citation2015). According to Nadler and Stockdale (Citation2012), barriers such as gender stereotyping and gender role perceptions continue to hinder women seeking leadership positions. A study by Schnarr (Citation2012) has shown that although women can reach middle management, they remain at this level, where men significantly outperform them when it comes to advancement. It shows that when organizations fail to promote gender diversity, women can be left behind and are not given the same opportunities to advance as men.

The social role theory is expanded by Eagly and Karau (Citation2002) through the development of the role congruity theory. These two theories were utilized in tandem because they both delve into societal gender stereotypes and how they influence expectations for roles, such as leader and carer (social role theory) and how individuals are evaluated in relation to these expectations (role congruity theory). According to the role congruity theory, women will receive favorable evaluations when their traits match cultural expectations of their gender role but will face criticism when their features deviate from these expectations. Prejudice towards women leaders arises from inconsistencies between gender stereotypes and typical leadership. The role congruity theory suggests this leads to perceptions of women less favorably as potential leaders and less favorably evaluated behavior. This results in less positive attitudes and increased challenges for women in leadership roles. Based on social role theory and role congruity theory, when group members perform social roles that are more closely related to gender than context, women often experience difficulties in their career journeys, known as the glass ceiling.

Social exchange theory

The Social Exchange Theory (SET) developed by Blau (Citation1964) suggests that behavior results from individuals conducting cost-benefit analysis while engaging with society and the environment. All social life is an exchange of tangible and intangible rewards and resources among actors (Emerson, Citation1976). This theory posits that the quality of social relationships depends on a rational assessment of the costs and benefits of continued involvement, and that relationships built on reciprocity can promote positive outcomes such as successful performance (Cropanzano & Mitchell, Citation2005). If an individual perceives that the benefits gained from a certain behavior outweigh its costs, they will engage in that behavior. If the individual perceives that the drawbacks will surpass the advantages, they will refrain from engaging in the behavior.

SET postulates that when one person does something for another, the recipient is obligated to return the favor, although the details of when and how are not specified (Blau, Citation1964). In addition, this theory suggests that trusting relationships are developed through social exchanges that are mutually beneficial to both parties (Flynn, Citation2005). SET establishes that resources are exchanged through a process of reciprocity, in which one party tends to reciprocate the good (or sometimes bad) deeds of the other, and the quality of the exchange is influenced by the relationship between the two parties. In the organizational context, this theory highlights the significance of balancing employees’ efforts with the rewards they obtain in return. When this equilibrium is maintained, employees feel more satisfied with their jobs, resulting in increased levels of engagement and commitment to their work.

The glass ceiling is a form of gender bias, where gender bias against women refers to how men and women are treated differently in the workplace. When individuals identify gender biases at work, they believe that members of their gender are systematically disadvantaged compared to the other gender (Ngo et al., Citation2014). Based on SET, the unfair treatment of employees by organizations due to sexist policies and practices leads to various negative reactions (Ensher et al., Citation2001). On the other hand, when an organization implements effective diversity management policies to create safe, fair, and inclusive workplaces, employees are more likely to contribute to the organization.

Leader-member exchange (LMX)

The LMX theory developed from the Average Leadership Style (ALS), which is a theory focusing on similar leadership behavior towards all employees within the same department, which later develops into dyadic vertical relationships to understand the relationship between supervisors and subordinates (Park et al., Citation2016). The LMX theory proposes that leaders will establish special relationships with a small group of subordinates (Robbins & Judge, Citation2015). This theory explains that leaders may develop unique social exchanges with their subordinates, and the quality of those relationships differs among subordinates (Graen & Uhl-Bien, Citation1995). The lower quality LMX is based on economic transactions, which means the exchanges are based on the formal contract of employment, while the high-quality LMX extends beyond the formal contract of employment, is based on trust and mutual obligation, and results in an affective attachment (Breevaart et al., Citation2015). According to Graen and Uhl-Bien (Citation1995), high-quality LMX indicates that employers who build better relationships with their employees are positively correlated with employee behavior.

Several studies have demonstrated the significant impact of LMX on work-related outcomes. A meta-analysis by Mazur (Citation2012) suggests that LMX positively correlates with individual work performance and group performance (Le Blanc & González-Romá, Citation2012). Employees who display high-quality LMX perform well at work (Dulebohn et al., Citation2012). Those findings indicate that higher LMX quality leads to more positive responses from employees.

Glass ceiling

The glass ceiling reflects the career barriers that prevent women from reaching higher positions in the hierarchical structure of the organization (Powell & Butterfield, Citation2015). The term glass ceiling refers to the invisible barrier that hinders women from holding senior-level positions in the workplace (Srivastava et al., Citation2020). In line with the aforementioned definitions, Kiaye and Singh (Citation2013) also explain the glass ceiling as an obstacle that is invisible, which is a metaphor for describing the impediments faced by women in progressing into senior management positions.

The concept of the glass ceiling developed in the 1980s due to the caste system and race and gender inequalities (Srivastava et al., Citation2020). The term ‘glass ceiling’ was first proposed by Carol Hymowitz and Timothy Schelhardt in the Wall Street Journal in 1986 (Eagly & Carli, Citation2007), which explains that females who attempt to reach executive positions are confronted with an invisible barrier, the impenetrable glass ceiling. The metaphor, as exemplified by an article written by Hymowitz and Schelhardt from the same year, reveals frustration when goals are envisioned but unattainable (Eagly & Carli, Citation2007).

Various studies on the glass ceiling have provided evidence of obstacles faced by women in achieving better career prospects, including family duties (Bombuwela et al., Citation2013), their role as mothers (Kargwell, Citation2008), and gaps between educational qualifications and experience (Kiaye & Singh, Citation2013). Kiaye and Singh (Citation2013) further argue that the perceived glass ceiling intensifies as males display disrespect and apathy towards the double roles of women. Due to male dominance, males tend to feel more capable than women; thus, gender discrimination contributes to the glass ceiling, and males seem to be unable to carry out orders set by females, which would lead to a clash with their male ego (Srivastava et al., Citation2020).

Career satisfaction

Career satisfaction reflects a subjective measure for career success, which refers to positive work-related outcomes and psychological outcomes achieved by individuals as a result of being in employment (Judge et al., Citation1995). Career satisfaction is an indicator of employees’ happiness about their way of managing their own careers, and this strongly determines whether employees want to remain employed in the organization (Dubbelt et al., Citation2019). Career satisfaction also indicates the extent to which individuals are satisfied with their career experience and reflects their unique and important personal well-being construct (Klusmann et al., Citation2008; Mauno et al., Citation2014).

Career satisfaction is derived from individuals’ assessments of their career development and success while fulfilling their duties (Seibert & Kraimer, Citation2001). Career satisfaction has become a subjective dimension based on employees’ points of view, and covers salary, career paths, and training (Greenhaus et al., Citation1990). As suggested by Al-Ghazali and Sohail (Citation2021), career satisfaction covers individuals’ perceptions of the accumulative effect of experience from a range of jobs and progress attained in a certain period of time. Thus, career satisfaction is a crucial indicator of subjective career success and significantly relates to the job (Orser & Leck, Citation2010).

Work engagement

Work engagement is a positive state of mind related to work that is characterized by enthusiasm, dedication, and absorption (Schaufeli et al., Citation2006). Employees with high engagement show higher enthusiasm and energy, feel proud and inspired by their work, and feel that time passes very quickly when they do their work (Breevaart et al., Citation2015). Engaged employees are also passionate about their jobs and perceive a deep relationship with the company (Robbins & Judge, Citation2015). Kahn (Citation2010) defines employee work engagement as a job and comprehensive (physical, cognitive, and emotional) self-expressions in their roles at work. Work engagement of employees encompasses their relationships with professional roles or their duties and also their organizations (Schaufeli & Salanova, Citation2011). Work engagement is also perceived as a deliberate and considerate pursuit of work (that is, dedication and cognitive engagement) as a kind of absorption and interest, as well as inspiration and energy available to be passionate about their work (Joo & Lee, Citation2017).

Research on work engagement has also examined work engagement as a phenomenon that resembles the flow of water with dimensions of energy, dedication, and absorption style while performing at work (Upadyaya & Salmela-Aro, Citation2015). Previous studies have demonstrated that work engagement is correlated with work-related outcomes, as indicated by high performance in the workplace (Alfes et al., Citation2013; Schaufeli & Bakker, Citation2004), organizational commitment (Hakanen et al., Citation2006), and organizational citizenship behaviors (Babcock-Roberson & Strickland, Citation2010). Engaged employees are also proven to display positive organizational outcomes, such as higher profits and productivity, a lower turnover rate (Harter et al., Citation2002), a higher level of organizational commitment (Schaufeli & Bakker, Citation2004), and work-family satisfaction (Bakker et al., Citation2014).

Hypotheses development

Employees who build high-quality LMX with their leader tend to gain more support and also indicate a stronger emotional bond with their work, compared to employees with low-quality LMX (Park et al., Citation2016). Goldman (Citation2001) found that leaders’ support affects the discrimination perceived by employees in the workplace. Schaffer and Riordan (Citation2013) argue that perceptions of unequal treatment indicate discrimination in the workplace. When individuals observe treatment discrimination and gender stereotypes within their organizations, this indicates that a glass ceiling exists. Other studies have also revealed that stress induced by employers can decrease when employers and employees maintain positive interpersonal relationships. Referring to Rosen et al. (Citation2011), employees with high-quality LMX tend to perceive that their employers will be able to protect them when the employees are in working environments that put them in a disadvantaged position.

H1: LMX has a negative effect on the glass ceiling.

In the gender role congruity theory (Eagly & Karau, Citation2002), the compatibility of genders and other roles, specifically leadership roles and the role to determine processes and primary factors that affect the compatibility of perceptions and the consequences of the arising prejudice and detrimental behavior are explained. The glass ceiling indicates that gender role congruity theory applies in the workplace. Consequently, the glass ceiling impacts work-related outcomes, such as work engagement and career satisfaction. From a social exchange theory perspective, the perception of the glass ceiling is seen by female employees as an imbalance between their efforts and the rewards they gain in return since gender discrimination at the workplace will prevent them from reaching high-level positions even though they expend full effort in their jobs, hence potentially lowering their satisfaction and engagement at work. Various studies have found the impacts of the perceived glass ceiling on work engagement and demonstrated that female employees perceived work differentiation, and gender discrimination negatively affected work engagement (Kim, Citation2015; Messarra, Citation2014; Sia et al., Citation2015). Meanwhile, not many of the studies on work engagement are from the perspective of gender, since most of them were explored in the contexts of Western societies (Banihani & Syed, Citation2016).

H2: The glass ceiling negatively affects work engagement

The perceived glass ceiling also relates to career satisfaction. Female career progression is often halted at certain levels, and it is increasingly difficult to hold positions at higher levels. Females in top-level management positions encounter more obstacles compared to their male and junior female colleagues (Srivastava et al., Citation2020). Despite their hard work and doing the exact same jobs as men, females have to deal with accepting salary reductions, having less authority, and receiving fewer international mobility opportunities (Lyness & Thompson, Citation1997). The glass ceiling makes female employees lose opportunities to apply for positions with particular profiles, compromise with compensation, and endure the pressure of fulfilling family duties, which renders them less progressive in their careers than their male coworkers. Inequality in the workplace would eventually create a glass ceiling and victimization, which have a negative impact on female career satisfaction (Srivastava et al., Citation2020).

H3: The glass ceiling negatively affects career satisfaction

The impact of the glass ceiling on various work-related outcomes cannot be separated from the quality of the relationship between leaders and employees. According to Goldman (Citation2001), the quality of leader support affects employees’ perceptions of discrimination in the workplace. Unfair treatment indicates a vital factor of discrimination in the workplace (Schaffer & Riordan, Citation2013). Park et al. (Citation2016) found that workplace discrimination in employee selection, evaluation, promotion, and reward processes has a negative impact not only on organizational effectiveness and performance, but also on career success. Furthermore, Park et al. (Citation2016) suggest that employees who experience gender discrimination against their own gender not only feel that the organization supports the other gender in terms of recruitment and promotion but also feel that they have less power in their work, so they experience decreased self-efficacy and develop negative work attitudes. In other words, the perception of differential treatment by leaders is determined by the quality of the relationship they build with employees. In this case, the influence mechanism of LMX quality on the glass ceiling can reduce employee attitudes and behaviors in the workplace. This is in line with the main focus of LMX theory to establish unique reciprocity or mature relationships, such as partnerships between leaders and employees, as an effective leadership process that will ultimately increase the chances of desired organizational outcomes (Graen & Uhl-Bien, Citation1995).

H4: Glass ceiling mediates the effect of LMX on work engagement and career satisfaction

Methodology

Data collection

The data were collected from female employees working as permanent employees in companies of various sectors at the time when the online survey was conducted. In this online survey, the researchers used snowball sampling (i.e. a smaller sample size was used to invite other participants through the social networks of the initial respondents). Snowball sampling allows data collection from a population in which a standard sampling approach is impossible or very expensive, for the purpose of studying the characteristics of individuals in the population (Handcock & Gile, Citation2011). This research involved female respondents from various types of companies spread across various regions of Indonesia, thus, snowball sampling through an online survey was the most feasible technique. Using a cross-sectional study design, the researchers recruited several key persons as the initial sample to fill in the online questionnaire. These key individuals were then asked to forward the online questionnaire to their female coworkers so that the sample size grew. From 469 responses, there were 291 responses that were promptly available to be analyzed, after discarding unsuccessful questionnaire responses that had irrelevant answers, repeated answers, and excessive missing data. The response rate is 62.05%.

The final sample consisted of female employees, which represented 8 age groups, namely under 20 years old (2%), 21–25 years old (44%), 26–30 years old (29%), 31–35 years old (11%), 36–40 years old (7%), 41–45 years old (2%), 46–50 years old (3%) and over 50 years old (2%). Based on marital status at the time of the survey, 62% of the respondents were unmarried, 37% of the respondents were married, and 1% of the respondents were divorced. Concerning child dependents, 70% of the respondents were childless, 15% of them had 1 child dependent, 10% of the respondents had 2 children, 3% of these respondents had 3 child dependents, and the rest, at 1%, had 4 or more child dependents. In regards to educational qualifications, 12% of respondents were high school graduates, 16% held an associate degree, 64% held a bachelor degree, 7% held a master’s degree, and 1% held a doctoral degree. Also, based on the length of employment at the time the data were collected, 71% of respondents had been working for 1–5 years, 18% of them had 6–10 years of service, 7% had 11–15 years of service, and the rest, at 4%, had 15 or more years of service. These demographic characteristics indicate that most of the respondents are millennials, which are characterized by those born between 1980 and 1995, enjoying life by working and playing, and pursuing career advancement (Ng et al., Citation2010). This is shown by the majority of respondents who belonged to the age range of 20–40 years, were not married, did not have children, and held a bachelor degree.

Measures

The questionnaire by Graen and Uhl-Bien (Citation1995) was used to measure LMX, consisting of 6 question items. Respondents were asked to indicate their responses to 6 question items on a 5 point Likert scale, which ranged from 1, which indicated ‘Strongly Disagree’, to 5 which indicated ‘Strongly Agree’. The glass ceiling was measured using a questionnaire adapted from Foley et al. (Citation2005), and the questionnaire consisted of 4 question items. Respondents were asked to respond to questions about their perceptions of unfair treatment because of gender. All items of questions were measured using a 5 point Likert scale from 1 (‘Strongly Disagree’) to 5 (‘Strongly Agree’). Nine question items from Balducci et al. (Citation2010) were used to measure work engagement on a 5 point Likert scale ranging from 1 (‘Strongly Disagree’) to 5 (‘Strongly Agree’). Career satisfaction was measured using a scale designed by Greenhaus et al. (Citation1990) and 5 question items on the Likert scale were given to the respondents. The Likert scale was used to measure the level of satisfaction felt by respondents, from 1 (‘Very Dissatisfied’) to 5 (‘Very Satisfied’).

Data analysis

The partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was used to test the hypotheses that were developed in this research. This technique has the advantage of evaluating relationships among a number of variables simultaneously (Zhang & Bartol, Citation2010). Compared to covariance-based SEM (CB-SEM), PLS-SEM is more appropriate to apply when the purpose of the research focuses on predictions and explanations of constructs, smaller sample sizes, and data with an abnormal distribution (Hair et al., Citation2017). Thus, the proposed model of PLS-SEM was suitable for testing the hypotheses. There are two steps in PLS-SEM analysis: measurement model evaluation and structural model evaluation. In this study, the quality of the measurement model was assessed based on internal consistency for reliability and validity (convergent validity and discriminant validity). According to Hair et al. (Citation2017), a construct would be deemed to fulfill requirements for internal consistency reliability if the value of composite reliability is greater than 0.70. A construct fulfills the requirements of convergent validity if the value of the indicator’s outer loading is greater than 0.70 or the value of the average variance extracted (AVE) is above 0.50. For assessing the discriminant validity, the authors used the Heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) with a 0.90 threshold (Hair et al., Citation2017). This means that the requirement of discriminant validity is satisfied if the result from an assessment using HTMT has a critical value that is less than 0.90.

Results

Preliminary analyses

shows the minimums, maximums, means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations among variables. The results of the analysis provided evidence for the formulated hypotheses. Leader-member exchange had a negative and significant correlation with the glass ceiling (r= −0.34, p < 0.01). Leader-member exchange was also positively and significantly correlated to career satisfaction (r = 0.36, p < 0.01), and work engagement (r = 0.37, p < 0.01). Meanwhile, the perceived glass ceiling also had a negative, significant correlation with career satisfaction (r= −0.23, p < 0.01), and work engagement (r= −0.34, p < 0.01). Lastly, career satisfaction was positively and negatively correlated with work engagement (r = 0.42, p < 0.01).

Table 1. Minimums, maximums, means, standard deviations (SD) and inter-correlations of variables.

Measurement model evaluation

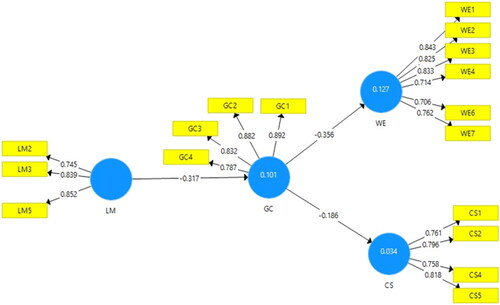

According to , the value of composite reliability for each construct was above 0.7. This indicates that all constructs satisfied requirements for internal consistency reliability. In the same table, the loading value of each of the indicators was greater than 0.7 after eliminating several items that had loading values that were less than 0.7. The AVE value for each construct was also above 0.5. Thus, all constructs have fulfilled the requirements for convergent validity.

Table 2. Assessment result for the measurement model.

In , the HTMT value for each construct was less than 0.90. This suggests that all constructs satisfied the requirement for discriminant validity. Thus, the results of the analysis shown in and provided evidence that all constructs satisfied the requirements for validity and reliability for the next testing phase.

Table 3. Discriminant validity (HTMT0.90 criterion).

Structural model evaluation

In the evaluation of the structural model, the hypotheses were tested by using a bootstrapping process with a resample of 1,000 (Hair et al., Citation2017). and display the results of the structural model evaluation ():

Table 4. Summary of results.

Hypothesis 1 predicts that LMX negatively affects the perceived glass ceiling. In direct testing, the result of the structural model analysis () showed that LMX had a negative, significant effect on the perceived glass ceiling (ß= −0.349, p-value <0.01). Therefore, H1 is supported. The result of the analysis also suggests that the perceived glass ceiling negatively and significantly affected work engagement (ß= −0.347, p-value <0.01) and career satisfaction (ß= −0.242, p-value <0.01). Therefore, H2 and H3 are supported.

The results of the indirect testing show that the perceived glass ceiling mediated the effect of LMX on career satisfaction (ß = 0.084, p-value <0.01) and work engagement (ß = 0.121, p-value <0.01). Since the results of the testing suggest that LMX directly affects career satisfaction and work engagement, the perceived glass ceiling fully mediates the effect of LMX on career satisfaction and work engagement. Therefore, H4 is supported.

Discussion and conclusion

Researchers as well as practitioners have since long argued that males and females perceive their career success differently in regards to social exchange between employees and employers. In fact, female employees are still confronted with a glass ceiling in the workplace that potentially impedes their career development. This study examines the effect of LMX on the glass ceiling, which leads to career satisfaction and work engagement. The findings demonstrate that LMX negatively affects the glass ceiling. This means that the higher quality of the relationship built by leaders with their employees, leads to decreasing levels of the perceived glass ceiling among female employees. The higher relationship quality indicates a higher quality of LMX, in which employees observe a strong relationship with and support from their employer in the workplace, including the notion that their employer would protect them from discrimination such as the glass ceiling. The findings in this study are in line with previous research by Goldman (Citation2001), which has demonstrated the effect of employers’ support qualities on employees’ perceptions of discrimination in the workplace. These findings also reinforce those of Park et al. (Citation2016) that suggest LMX negatively affects employment and promotion discrimination.

Furthermore, the findings of this study also provide evidence that the glass ceiling has a negative effect on career satisfaction and work engagement. When females encounter a glass ceiling in the workplace, this situation would lower their career satisfaction and work engagement. Females who perceive a glass ceiling would believe that they are treated differently from their male colleagues because of their gender and not their ability and competence. The perceived glass ceiling would lead females to feel dissatisfied with their careers, and their work engagement would decrease. The findings in this study corroborate those of Smith et al. (Citation2012), which also suggest that females’ perceptions of a glass ceiling correlate with career success, satisfaction, and work engagement. Previous studies have also found the glass ceiling effect on work engagement, in which females receive unequal treatment in the workplace (Kim, Citation2015; Sia et al., Citation2015). Messarra (Citation2014) has also concluded that when females perceive unfairness in the workplace, their levels of commitment and engagement are negatively affected. In addition, this research also demonstrates that the glass ceiling mediates the effect of LMX on career satisfaction and work engagement. This suggests that high-quality LMX in the relationship between employers and employees reduces females’ perceptions of the glass ceiling, leading to increasing levels of career satisfaction and work engagement. The present study clarifies how LMX becomes a panacea for the perceived glass ceiling among female employees, which in turn increases their level of career satisfaction and work engagement. The high-quality relationship of female employees with their leaders reduces their perceptions of being discriminated against, which in turn promotes a higher level of career satisfaction and work engagement.

Implications of the study

This study has documented how the mechanism of the relationship between LMX quality and the glass ceiling explains work engagement and career satisfaction. In particular, not many studies have examined the glass ceiling by considering the quality of LMX as the trigger. This study contributes theoretically by providing evidence of the relationship between LMX and the glass ceiling that affects work-related outcomes. This study also proved social exchange theory (Blau, Citation1964) as demonstrated by LMX and social role theory (Eagly, Citation1987) as indicated by the glass ceiling, as well as how the combination of the two theories explains individual behavior in the workplace.

Organizational policies need to be designed in such a way as to prevent a glass ceiling in the workplace, including through leaders who are able to manage the quality of relationships with employees. A good quality relationship with employees can be maintained, among others, by paying attention to the needs of employees, listening to their opinions, and most importantly protecting employees from all forms of discrimination in the workplace, including gender stereotypes. This will make employees feel comfortable, and female employees will also feel protected from the threat of gender discrimination, so that they will be able to increase career satisfaction and work engagement.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

This study has several limitations to be considered. First, this is a cross-sectional study, so caution is needed in concluding causality between variables. Therefore, further research is suggested to use a longitudinal design for a more precise conclusion about the relationship between variables. Second, all data were acquired through a self-report survey, which has implications for the potential for common method bias. However, variables in this study were measured using well known scales, which could control the potential error, thus reducing common method bias (Spector, Citation1987). Finally, this study was only conducted on female employees in the private sector, which limits the generalizability of the results. Further research can be carried out in other sectors, such as government institutions, to add more contributions to the literature.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT.docx

Download MS Word (12.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sinto Sunaryo

Sinto Sunaryo is a lecturer in Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Indonesia. Her research interests are organizational behavior and HRM. She is a certified Human Resource Professional (SHRM-CP).

Reza Rahardian

Reza Rahardian is a lecturer in Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Indonesia. His research interests are strategic management and operation management.

Risgiyanti

Risgiyanti is a lecturer in Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Indonesia. Her research interests are organizational behavior and leadership. She joins the Local Wisdom Research Group.

Joko Suyono

Joko Suyono is a lecturer in Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Indonesia. He is leader of the Local Wisdom Research Group. His research interests are leadership and compensation management.

Dian Ekowati

Dian Ekowati is a lecturer in Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Airlangga, Indonesia. She received her Ph.D. from University of York. Her research interests are organizational change, territoriality and inter-organizational collaboration.

References

- Alfes, K., Truss, C., Soane, E. C., Rees, C., & Gatenby, M. (2013). The relationship between line manager behavior, perceived HRM practices, and individual performance: Examining the mediating role of engagement. Human Resource Management, 52(6), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21512

- Al-Ghazali, B. M., & Sohail, M. S. (2021). The impact of employees’ perceptions of CSR on career satisfaction: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Sustainability, 13(9), 5235. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095235

- Babcock-Roberson, M. E., & Strickland, O. J. (2010). Leadership, work engagement, and organizational citizenship behaviors. The Journal of Psychology, 144(3), 313–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223981003648336

- Bakker, A. B., Shimazu, A., Demerouti, E., Shimada, K., & Kawakami, N. (2014). Work engagement versus workaholism: A test of the spillover-crossover model. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 29(1), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-05-2013-0148

- Baker, C. (2014). Stereotyping and women’s roles in leadership positions. Industrial and Commercial Training, 46(6), 332–337. https://doi.org/10.1108/ICT-04-2014-0020

- Balasubramanian, S. A., & Lathabhavan, R. (2017). Women’s glass ceiling beliefs predict work engagement and burnout. Journal of Management Development, 36(9), 1125–1136. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-12-2016-0282

- Balducci, C., Fraccaroli, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2010). Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9): A cross-cultural analysis. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26(2), 143–149. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000020

- Banihani, M., & Syed, J. (2016). A macro-national level analysis of Arab women’s work engagement. European Management Review, 14(2), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12095]

- Bendl, R., & Schmidt, A. (2010). From “glass ceilings” to “firewalls”: Different metaphors for describing discrimination. Gender, Work & Organization, 17(5), 612–634. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2010.00520.x

- Blau, P. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Wiley.

- Blessie, P. R., & Supriya, M. V. (2018). Masculine and feminine traits and career satisfaction: Moderation effect of glass ceiling belief. International Journal of Business Innovation and Research, 16(2), 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBIR.2018.091910

- Bombuwela, P. M., & De Alwis, A. C, Faculty of Commerce and Management, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka. (2013). Effects of glass ceiling on women career development in private sector organizations: Case of Sri Lanka. Journal of Competitiveness, 5(2), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.7441/joc.2013.02.01

- BPS-Statistics Indonesia. (2018). Labor force situation in Indonesia. (Sub-directorate of Manpower Statistics, Ed.). Badan Pusat Statistik/BPS-Statistics Indonesia.

- Breevaart, K., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Van Den Heuvel, M. (2015). Leader-member exchange, work engagement, and job performance. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 30(7), 754–770. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-03-2013-0088

- Byrne, Z. S., Dik, B. J., & Chiaburu, D. S. (2008). Alternatives to traditional mentoring in fostering career success. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 72(3), 429–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2007.11.010

- Cook, A., & Glass, C. (2014). Women and top leadership positions: Towards an institutional analysis. Gender, Work & Organization, 21(1), 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12018

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279602

- Dezsö, C. L., & Ross, D. G. (2019). Does female representation in top management improve firm performance? A panel data investigation. Strategic Management Journal, 33(9), 1072–1089. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.1955

- Dubbelt, L., Demerouti, E., & Rispens, S. (2019). The value of job crafting for work engagement, task performance, and career satisfaction: Longitudinal and quasi-experimental evidence. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(3), 300–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2019.1576632

- Dulebohn, J. H., Bommer, W. H., Liden, R. C., Brouer, R. L., & Ferris, G. R. (2012). A meta-analysis of antecedents and consequences of leader-member exchange: Integrating the past with an eye toward the future. Journal of Management, 38(6), 1715–1759. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311415280

- Eagly, A. H. (1987). Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Eagly, A. H., & Carli, L. L. (2007). Women and the labyrinth of leadership. Harvard Business Review, 85(9), 62–71.

- Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), 573–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.109.3.573

- Emerson, R. (1976). Social exchange theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 2(1), 335–362. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.02.080176.002003.

- Ensher, E. A., Grant-Vallone, E. J., & Donaldson, S. I. (2001). Effects of perceived discrimination on job satisfaction, organizational commitment, organizational citizenship behavior, and grievances. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 12(1), 53–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/1532-1096

- Flynn, F. J. (2005). Identity orientations and forms of social exchange in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 30(4), 737–750. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2005.18378875

- Foley, S., Hang-Yue, N., & Wong, A. (2005). Perceptions of discrimination and justice: Are there gender differences in outcomes? Group & Organization Management, 30(4), 421–450. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601104265054

- Glass, C., & Cook, A. (2016). Leading at the top: Understanding women’s challenges above the glass ceiling. The Leadership Quarterly, 27(1), 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.09.003

- Goldman, B. M. (2001). Toward an understanding of employment discrimination claiming: An integration of organizational justice and social information processing theories. Personnel Psychology, 54(2), 361–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2001.tb00096.x

- Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX). Management Department Faculty Publications, 57, 30.

- Greenhaus, J. H., Parasuraman, S., & Wormley, W. M. (1990). Effects of race on organizational experiences, job performance evaluations, and career outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 33(1), 64–86. https://doi.org/10.5465/256352

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd edition). Sage Publications.

- Hakanen, J. J., Bakker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2006). Burnout and work engagement among teachers. Journal of School Psychology, 43(6), 495–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2005.11.001]

- Handcock, M. S., & Gile, K. J. (2011). Comment: On the concept of snowball sampling. Sociological Methodology, 41(1), 367–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9531.2011.01243.x

- Harris, K. J., Wheeler, A. R., & Kacmar, K. M. (2009). Leader-member exchange and empowerment: Direct and interactive effects on job satisfaction, turnover intentions, and performance. The Leadership Quarterly, 20(3), 371–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.03.006

- Harter, J. K., Schmidt, F. L., & Hayes, T. L. (2002). Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(2), 268–279. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.2.268

- Isaac, C. A., Kaatz, A., & Carnes, M. (2012). Deconstructing the glass ceiling. Sociology Mind, 02(01), 80–86. https://doi.org/10.4236/sm.2012.21011

- Jain, M., & Mukherji, S. (2010). The perception of glass ceiling in Indian organisations: An exploratory study. South Asian Journal of Management, 17(1), 23–42.

- Joo, B. K., & Lee, I. (2017). Workplace happiness: work engagement, career satisfaction, and subjective well-being. Evidence-Based HRM: A Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship, 5(2), 206–221. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBHRM-04-2015-0011

- Judge, T. A., Cable, D. M., Boudreau, J. W., & Bretz, R. D.JR., (1995). An empirical investigation of the predictors of executive career success. Personnel Psychology, 48(3), 485–519. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1995.tb01767.x

- Jung, Y., & Takeuchi, N. (2016). Gender differences in career planning and success. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 31(2), 603–623. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-09-2014-0281

- Kahn, W. A. (2010). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724. https://doi.org/10.5465/256287

- Kargwell, S. (2008). Is the glass ceiling kept in place in Sudan? Gendered dilemma of the work-lie balance. Gender in Management, 23(3), 209–224. https://doi.org/10.1108/17542410810866953

- Kementerian Pemberdayaan Perempuan dan Perlindungan Anak. (2019). Profil Perempuan Indonesia 2019. Kementrian Pemberdayaan dan Perlindungan Anak, ISSN: 2089–3515.

- Khalid, S., & Sekiguchi, T. (2019). The mediating effect of glass ceiling beliefs in the relationship between women’s personality traits and their subjective career success. NTU Management Review, 29(3), 193–220. https://doi.org/10.6226/NTUMR.201912_29(3).0006

- Kiaye, R. E., & Singh, A. M. (2013). The glass ceiling: A perspective of women working in Durban. Gender in Management, 28(1), 28–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/17542411311301556

- Kim, S. (2015). The effect of gender discrimination in organization. International Review of Public Administration, 20(1), 51–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/12294659.2014.983216

- Kiser, A. I. T. (2015). Workplace and leadership perceptions between men and women. Gender in Management, 30(8), 598–612. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-11-2014-0097

- Klusmann, U., Kunter, M., Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., & Baumert, J. (2008). Teachers’ occupational well-being and quality of instruction: The important role of self-regulatory patterns. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(3), 702–715. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.100.3.702

- Koenig, A. M., & Eagly, A. H. (2014). Evidence for social role theory of stereotype content: observations of groups’ roles shape stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(3), 371–392. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037215

- Le Blanc, P. M., & González-Romá, V. (2012). A team level investigation of the relationship between leader-member exchange (LMX) differentiation, and commitment and performance. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(3), 534–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.12.006

- Lyness, K. S., & Thompson, D. E. (1997). Above the glass ceiling? A comparison of matched samples of female and male executives. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(3), 359–375. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.82.3.359

- Mauno, S., De Cuyper, N., Tolvanen, A., Kinnunen, U., & Mäkikangas, A. (2014). Occupational well-being as a mediator between job insecurity and turnover intention: Findings at the individual and work department levels. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23(3), 381–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2012.752896

- Mazur, K. (2012). Leader-member exchange and individual performance: The meta-analysis. Management, 16(2), 40–53. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10286-012-0054-0

- McKinsey Global Institute. (2018). The power of parity : Advancing women’s equality in Asia Pacific focus: Indonesia. (May Issue). McKinsey & Company.

- Messarra, C. L. (2014). Religious diversity at work: The perceptual effects of religious discrimination on employee engagement and commitment. Contemporary Management Research, 10(1), 59–80. https://doi.org/10.7903/cmr.12018

- Mohammadkhani, F., & Gholamzadeh, D. (2016). The influence of leadership styles on the women’s glass ceiling beliefs. Journal of Advanced Management Science, 4(4), 276–282. https://doi.org/10.12720/joams.4.4.276-282

- Nadler, J. T., & Stockdale, M. S. (2012). Workplace gender bias: Not just between strangers. North American Journal of Psychology, 14(2), 281–292.

- Ng, E. S., & Sears, G. J. (2017). The glass ceiling in context: The influence of CEO gender, recruitment practices and firm internationalisation on the representation of women in management. Human Resource Management Journal, 27(1), 133–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12135

- Ng, E. S. W., Schweitzer, L., & Lyons, S. T. (2010). New generation, great expectations: A field study of the millennial generation. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(2), 281–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9159-4

- Ngo, H. Y., Foley, S., Ji, M. S., & Loi, R. (2014). Work satisfaction of Chinese employees: A social exchange and gender-based view. Social Indicators Research, 116(2), 457–473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0290-2

- Orser, B., & Leck, J. (2010). Gender influences on career success. Gender in Management, 25(5), 386–407. https://doi.org/10.1108/17542411011056877

- Park, S. G., Kang, H. J. A., Lee, H. R., & Kim, S. J. (2016). The effects of LMX on gender discrimination and subjective career success. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 55(1), 127–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12098

- Powell, G. N., & Butterfield, D. A. (2003). Gender, gender identity, and aspirations to top management. Women in Management Review, 18(1/2), 88–96. https://doi.org/10.1108/09649420310462361

- Powell, G. N., & Butterfield, D. A. (2015). The glass ceiling: What have we learned 20 years on? Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 2(4), 306–326. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-09-2015-0032

- Robbins, S. P., & Judge, T. A. (2015). Organizational behavior (16th ed.). Pearson Education.

- Rosen, C. C., Harris, K. J., & Kacmar, K. M. (2011). LMX, context perceptions, and performance: An uncertainty management perspective. Journal of Management, 37(3), 819–838. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310365727

- Sarika, G. (2015). Breaking the glass ceiling: Initiatives of Indian industry (a study with special reference to exemplary organizations. The International Journal of Business & Management, 3(3), 255.

- Schaffer, B. S., & Riordan, C. M. (2013). Relational demography in supervisor-subordinate dyads: An examination of discrimination and exclusionary treatment. Revue Canadienne Des Sciences de L’Administration [Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences], 30(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjas.1237

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(3), 293–315. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.248

- Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405282471

- Schaufeli, W., & Salanova, M. (2011). Work engagement: On how to better catch a slippery concept. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 20(1), 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2010.515981

- Schnarr, K. (2012). Are female executives finally worth more than men? Ivey Business Journal Online, 1(1), 1–3.

- Seibert, S. E., & Kraimer, M. L. (2001). The five-factor model of personality and career success. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2000.1757

- Sharma, S., & Kaur, R. (2019). Glass ceiling for women and work engagement: The moderating effect of marital status. FIIB Business Review, 8(2), 132–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/2319714519845770

- Sia, S. K., Sahoo, B. C., & Duari, P. (2015). Gender discrimination and work engagement: Moderating role of future time perspective. South Asian Journal of Human Resources Management, 2(1), 58–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/2322093715577443

- Skelly, J., & Johnson, J. B. (2011). Glass ceilings and great expectations: Gender stereotype impact on female professionals. Southern Law Journal, 21, 59–70.

- Smith, P., Caputi, P., & Crittenden, N. (2012). How are women’s glass ceiling beliefs related to career success? Career Development International, 17(5), 458–474. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620431211269702

- Spector, P. E. (1987). Method variance as an artifact in self-reported affect and perceptions at work: Myth or significant problem? Journal of Applied Psychology, 72(3), 438–443. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.72.3.438

- Srivastava, S., Madan, P., & Dhawan, V. K. (2020). Glass ceiling – an illusion or realism? Role of organizational identification and trust on the career satisfaction in Indian organizations. Journal of General Management, 45(4), 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306307020938976

- Upadyaya, K., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2015). Development of early vocational behavior: Parallel associations between career engagement and satisfaction. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 90, 66–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.07.008

- Zhang, X., & Bartol, K. M. (2010). Linking empowering leadership and employee creativity: The influence of psychological empowerment, intrinsic motivation, and creative process engagement. Academy of Management Journal, 53(1), 107–128. https://doi.org/10.1108/dlo.2010.08124ead.007