Abstract

Introduction

Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide. In Diabetics, ASCVD is associated with poor prognosis and a higher case fatality rate compared with the general population. Sub-Saharan Africa is facing an epidemiological transition with ASCVD being prevalent among young adults. To date, over 20 million people have been living with DM in Africa, Tanzania being one of the five countries in the continent reported to have a higher prevalence. This study aimed to identify an individual’s 10-year ASCVD absolute risk among a diabetic cohort in Tanzania and define contextual risk enhancing factors.

Methods

A prospective observational study was conducted at the Aga Khan hospital, Mwanza, for a period of 8 months. The hospital is a 42-bed district-level hospital in Tanzania. Individuals 10-year risk was calculated based on the ASCVD 2013 risk calculator by ACC/AHA. Pearson’s chi-square or Fischer’s exact test was used to compare categorical and continuous variables. Multivariable analysis was applied to determine contextual factors for those who had a high 10-year risk of developing ASCVD.

Results

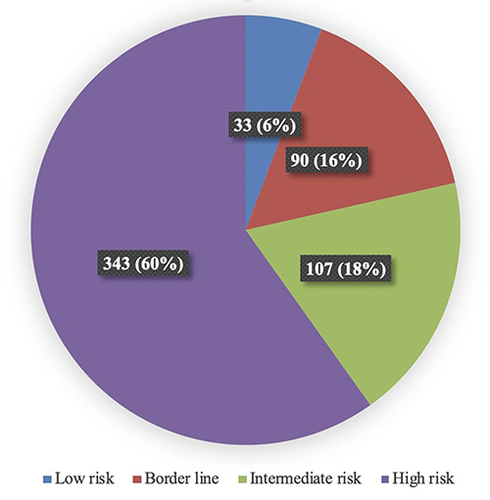

The overall cohort included 573 patients. Majority of the individuals were found to be hypertensive (n = 371, 64.7%) and obese (n = 331, 58%) having a high 10-year absolute risk (n = 343, 60%) of suffering ASCVD. The study identified duration of Diabetes Mellitus (>10 years) (OR 8.15, 95% CI 5.25–14.42), concomitant hypertension (OR 1.82 95% CI 1.06–3.06), Diabetic Dyslipidemia (OR 1.44, 95% CI 1.08–1.92) and deranged serum creatinine (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.02–1.03) to be the risk enhancing factors amongst our population.

Conclusion

The study confirms the majority of diabetic individuals in the lake region of Tanzania to have a high 10-year ASCVD risk. The high prevalence of obesity, hypertension and dyslipidemia augments ASCVD risk but provides interventional targets for health-care workers to decrease these alarming projections.

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus has escalated dramatically in the past three decades.Citation1 It is estimated approximately 400 million people globally have diabetes mellitus, with the majority residing in low- and middle-income countries.Citation1 As of 2021, the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) has reported over 20 million people living with diabetes mellitus in Africa, with Tanzania being one of the five countries in the continent having a prevalence of above 7%.Citation2 Diabetes mellitus is a major risk factor for Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) and premature mortality.Citation3,Citation4 ASCVD encompasses: Coronary, Cerebrovascular, peripheral artery and Aortic diseases.Citation5 The spectrum and pattern of ASCVD in sub-Saharan Africa are increasing due to ongoing urbanization, major changes in lifestyle and the simultaneous burden of poverty, malnutrition and HIV as well as other neglected infectious diseases.Citation6 According to various reports, Tanzania is experiencing a higher burden of non-Communicable diseases (NCDs) with ASCVD being the most prevalent, especially among adults between 25 and 64 years of age.Citation7,Citation8 It is projected if no strategic measures are taken, mortality rates related to ASCVD in Tanzania will exponentially rise by 2025.Citation8 Despite the mounting evidence, research in ASCVD is very limited in Tanzania; hindering policy improvement, effective evidence-based management and the development of preventive medicine.Citation9

Individual risk assessment is a crucial and decisive step in combating the challenge posed by ASCVD.Citation5 Understanding the 10-year risk for ASCVD identifies patients in different risk groups that would warrant strategic and multidisciplinary intervention for primary prevention.Citation5,Citation10 To date, there are several ASCVD risk calculators used worldwide establishing a strong foundation of preventive medicine.Citation11,Citation12 It is important to use a risk calculator that is been well validated, feasible, easy to use and applicable for patient-specific race and ethnicity.Citation13 The American Heart Association (AHA) and American College of Cardiology (ACC) recommend the 2013 ACC/AHA Pooled Cohort Equations CV Risk Calculator. The pooled cohort equation has been widely validated and is broadly used worldwide.Citation14 Additionally, the aforementioned risk calculator is very simple and incorporates readily available demographic and laboratory data. The calculator incorporates the following key variables: Patients’ age, gender, ethnicity, serum total cholesterol, serum HDL, comorbidities, systolic blood pressure, and smoking.Citation14 The PCE classifies individuals based on estimated risk: 10-year ASCVD risk <5% is reflected as low risk, 5–7.5% as borderline risk, 7.5–20% intermediate risk, and >20% considered high risk. Reducing cholesterol levels, specifically LDL, has drastically reduced rates of coronary artery disease and Cerebrovascular Accidents (CVA), simultaneously reducing the need for interventions, especially in resource-limited settings. The 2018 AHA/ACC and multi-society guidelines recommend individuals aged 40–75 with Diabetes and whose LDL is above 1.8 mmol/l to benefit from statin therapy.Citation15 Though traditional risk factors for ASCVD are well known and understood globally, the prevalence varies from one population to another.Citation5 Non-modifiable and risk-enhancing factors are currently considered impactful and may differ from one population to another as well as significantly alter the magnitude and the development of ASCVD.Citation13 Additionally, it is important to recognize contextual risk enhancing factors such as: healthcare access, health literacy, socio-economic inequality, education level, psychological stressors, guideline-based practice, and health-seeking behavior that further compound the foregoing key risk factors.Citation16 Thus, community-based research tailored towards identifying contextual prevailing modifiable and risk-enhancing factors for ASCVD in a respective population is essential for the implementation of preventive interventions and targeted therapy. To date, there are limited data available on the distribution, frequency, and magnitude of ASCVD among various diabetic cohorts in Tanzania. This study aimed to identify diabetic patients with a high 10-year risk of developing ASCVD and its associated contextual risk-enhancing factors amongst a Tanzanian cohort.

Methodology

This Observational prospective study was carried out from 2nd January to 30th October 2022. Consecutive patients diagnosed with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) attending the outpatient diabetic clinic at the Aga Khan Hospital Mwanza were recruited. The Aga Khan hospital is a forty-two-bed private facility equivalent to a district-level hospital. The hospital was established on 1st of August 2020 as part of the Aga Khan Health services Tanzania. The hospital complies with local and international standards and is the only Safe-Care accredited hospital in the region. The hospital offers a wide range of services in the fields of Internal medicine, surgery, obstetrics and gynecology as well as pediatrics.

Patients with T2DM were consecutively enrolled during the study period. Patients with previous ASCVDCitation13 were excluded from the study. Venous whole blood samples were withdrawn by an experienced phlebotomist and were analyzed in the hospital’s laboratory. Research assistants who had experience in the outpatient department entered patients’ demographic data, medications, presence of comorbidities, laboratory markers, fasting blood glucose (FBG) and vitals on the clinic visit. Research assistants also calculated the ASCVD score based on the AHA/ACC – PCE 2013, freely available online. The primary investigator rechecked data entered for accuracy and completeness. Patients were then grouped based on the ASCVD score, with >20% considered to have a high- 10-year risk of suffering ASCVD. Additionally, <5% was considered low risk; 5–7.5% as borderline risk and 5–20% as intermediate risk. Data were analyzed using frequency and percentages for categorical variables, while continuous variables were summarized using frequency median and interquartile ranges (IQR). Pearson’s chi-square or Fischer’s exact test and Wilcoxon rank sum test were used to compare categorical and continuous variables. Variables with a P-value <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Any variables considered statistically and clinically significant in explaining the outcome were possible inclusion in the logistic regression. Variables significantly associated with the outcome of interest at 5% level of significance in the univariate analysis were considered in the multivariable analysis. In the final model, adjusted Odds Ratio (aOR), P-value, and 95% Confidence interval (CI) were used to test the significance of the results. Variables with P-value <0.05 were considered major risk factors for a high 10-year risk of suffering ASCVD among diabetic patients. All analyses were performed using R-STUDIO.

Results

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

The study recruited a total of 573 participants. shows the study population’s general and clinical characteristics and compares the two risk groups. Our study identified the majority (n = 343, 60%) of the patients to be at high risk of suffering ASCVD in the next 10 years. The median age of the study population was 60 years [IQR: 52–68] years, most of whom were of African origin (n = 514, 89.7%), married (n = 381, 66.5%) and residing in an urban setting (n = 414, 72.3%). When the two risk groups were compared, statistical significance (P-value <0.05) was noted among several social and demographic variables, as seen in .

Table 1 Baseline Demographics of the Study Population

Out of the 573 participants, more than half of the cohort had hypertension (n = 371, 65%), of whom the majority were among the high-risk group (n = 284, 76.5%). Among those who had high risk, the majority were on more than one anti –Hypertensive agent (n = 196, 69.0%), as seen in .

Table 2 Illustrates Profile of Those Hypertensive and Diabetic

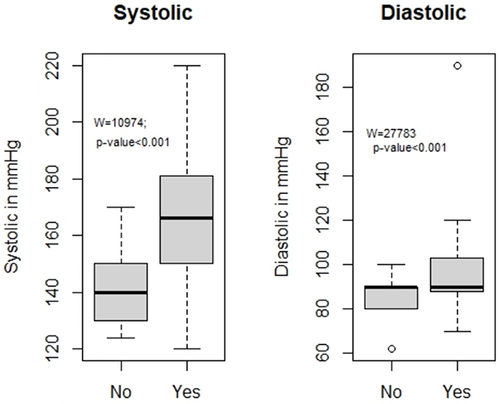

Elevated systolic and diastolic pressures were noted among the high-risk group, as seen in .

Figure 1 Box plot illustrating the comparison of the systolic and diastolic blood pressure of the diabetic and hypertensive cohort.

illustrates social habits noted among our diabetic cohort. The majority of our diabetic cohort was not involved in any social habits (383, 66.8%). No statistical significance was noted when the two risk groups were compared.

Table 3 Behavioral Profile of Our Diabetic Cohort

demonstrates the complete diabetic control and profile of our cohort and provides a comparison between the two risk groups. Statistical significance was noted among many variables. Of the high-risk group, the majority were on oral hypoglycemic agents (n = 269, 78.4%) and suffering from Diabetic related Microvascular complications (n = 303, 88.3%). Patients with a high risk of suffering ASCVD in the next 10 years had higher fasting blood glucose (FBG) and HbA1c. Elevated systolic and diastolic blood pressures were also noted in the high-risk group, as seen in .

Table 4 Complete Illustration of the Diabetic Cohort

provides a comparison of laboratory parameters between the two groups during the clinic visit. Statistical significance was noted amongst majority of the variables.

Table 5 Laboratory Parameters on Clinic Visit

exhibits the factors associated with the high risk of ASCVD. In the multivariable logistic regression model, the study identified duration of Diabetes Mellitus (>10 years) (OR 8.15, 95% CI 5.25–14.42), concomitant hypertension (OR 1.82 95% CI 1.06–3.06), elevated total cholesterol (OR 1.44, 95% CI 1.08–1.92), increased LDL (OR 1.59, 95% CI 1.18–2.16), higher triglyceride level (OR 1.38, 95% CI 1.02–1.90) and greater serum creatinine (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.02–1.03) to be risk enhancing factors of ASCVD as seen in .

Table 6 Factors Associated with a High-Risk 10-Year Risk of ASCVD

Discussion

This prospective observational study enabled us to accurately assess an individual’s 10-year risk of suffering ASCVD amongst our diabetic cohort. We found majority of our cohort to have a high 10-year risk of suffering ASCVD, as seen in .

Our results are in line with reports published from different African cohort’s highlighting the epidemiological transition of NCD in sub-Saharan Africa.Citation17 Latest contemporary data from high-income countries (HICs) has shown a declining prevalence of ASCVD, especially among diabetic patients.Citation18 This has been achieved by good glycemic control, public awareness, community interventions, effective primordial and primary prevention as well as the implementation of evidence-based practice. We hypothesize the alarming projections amongst our population to be amplified with various other modifiable factors and its poor control, such as obesity, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension.Citation19 Additionally, our cohort was primarily an African dominant with higher prevalence of aged population which may further account to the higher magnitude of ASCVD as suggested by anecdotal series.Citation17 It’s our observation that lack of adapting to the latest evidence-based guidelinesCitation15 may be a compounding factor to ASCVD-related burden. The latest guidelinesCitation15 not only advocates appropriate pharmacotherapy for primary prevention but also advocates encouragement of team–based approach over the current standard of care, addressing the socio-economic inequalities, improving medical education, emphasizing the need for diet and exercise, as well as addressing the concomitant burden of hypertension and obesity. Such measures have reduced ASCVD-related metrics and improved Health Adjusted life Expectancy (HALE).

Several classes of medications have been shown to effectively lower blood glucose but may or may not affect ASCVD risk. Recent literature has reported the impact of Sodium-Glucose Co-transport 2 (SGLT–2) inhibitors in reducing ASCVD-related morbidity and mortality, especially among patients suffering with Diabetes Mellitus.Citation20,Citation21 Furthermore, various studies have also advocated the use of Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists cardiovascular and all-cause mortality.Citation17,Citation22–24 Nonetheless, none of our patients were on the aforementioned medications. We postulate major obstacle being the availability and cost of such drugs in Tanzania.

Our study identified the duration of diabetes mellitus (>10 years) to be associated with a high 10-year risk of ASCVD. Our results are parallel to similar studies done globally.Citation25–27 It has been postulated that the interplay between traditional and nontraditional risk factors contributes to the formation and development of atherosclerosis.Citation19 Additionally, chronic exposure to hyperglycemia with worsening beta cell function is known to induce oxidative stress-triggering pathways leading to vascular damage.Citation25 Various reports have also indicated there is a possibility of other factors explaining these associations that have not yet been officially reported.Citation28 The explanation of this association is beyond the study’s scope. Nonetheless, the findings of this study emphasize the need for consistent follow-up and adequate glycemic control to reduce the risk of acquiring ASCVD.

Serum creatinine is considered a marker of kidney injury in various settings. Diabetes mellitus is the number one cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD) worldwide. Patients suffering from diabetic nephropathy have a higher risk of suffering ASCVD. Multiple studies done in other settings have yielded similar results.Citation29–31 There is mounting evidence that even mild kidney dysfunction is associated with a substantial increase in 10-year risk of suffering ASCVD.Citation32 Clinical guidelines from the National Kidney Foundation and the ACC/AHA recommend that deranged kidney function and albuminuria be considered ASCVD risk equivalent reflecting subclinical vascular damage and endothelial dysfunction.Citation33,Citation34 Statins have a huge role in the primary and secondary prevention of ASCVD. Nevertheless, various clinical trials have concluded its benefits only in the early stages of CKD, with little to no effect in the later stage and in those receiving dialysis.Citation35

Finally, this study highlights the huge burden of diabetic dyslipidemia. Our results are in line with various extensive epidemiological, genetic and clinical randomized trialsCitation36 done globally. Clinical trials of LDL cholesterol levels and the reduction in risk of ASCVD supports the principle that “lower is better”, tailoring the levels of LDL cholesterol reduction to the individual’s level of cardiovascular risk.Citation37 The occurrence of the first ASCVD among diabetic patients aged between 40 and 75 years is associated with increased morbidity and mortality rates.Citation38 Numerous large-scale trials have documented benefits in an ethnically and racially diverse population from statin therapy for the primary prevention of ASCVD.Citation15 The latest guideline recommends Diabetic patients having additional risk modifiers be on high-stain therapy while those just diabetic aged between 40 and 75 years be on moderate statin therapy for primary prevention of ASCVD.Citation15

Limitations

This was a single-center study, thus hindering the generalizability of the results. A randomly drawn larger sample would have been more beneficial and advantageous. The AHA/ACC PCE equation used to calculate the 10-year risk of ASCVD does not account for socio-economic inequality, an element that is prominent in the region. The equation also incorporates a single office blood pressure measurement and not ambulatory or home-based monitoring, which may overestimate an individual’s risk. Inherited disorders of lipid metabolism were not accounted for. Lastly, medication compliance amongst our cohort was not evaluated, which might have a significant impact on the projections.

Conclusion

The outcome of our study indicates that majority of diabetic patients in the lake region of Tanzania to have a high risk 10 – year risk of suffering ASCVD. The study identified duration of Diabetes Mellitus (>10 years), concomitant hypertension and Diabetic dyslipidemia to be main factors associated with high risk of ASCVD. The Factors are modifiable and are target for interventions. Findings from this observational study are important and significant in guiding appropriate measures of primary prevention, especially those in the intermediate and high-risk groups. Findings from this study will also aid in the strategic measures in combating the rising burden of NCD in the region both in private and public sector. Additional work needs to be done in strengthening evidence-based practice.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The study was presented and accepted by the Ethical committee the Aga Khan University, Ethical Review Committee, East Africa (AKU-ERC, EA) Reference number Ref: AKU/2022/030/fb/03/01. The ethical committee exempted individual Informed consent from study participants as the study design did not affect the rights and welfare of the patients. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis, interpretation and implementation. All authors took part in drafting, revising, and critically reviewing the article. All authors approved the final document to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Saeedi P, Petersohn I, Salpea P, et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9(th) edition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;157:107843. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107843

- Ogurtsova K, Guariguata L, Barengo NC, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: global estimates of undiagnosed diabetes in adults for 2021. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183:109118. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109118

- Zhao Y, Xiang P, Coll B, Lopez JAG, Wong ND. Diabetes associated residual atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in statin-treated patients with prior atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Diabetes Complications. 2021;35(3):107767. doi:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2020.107767

- Raghavan S, Vassy JL, Ho YL, et al. Diabetes mellitus-related all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in a national cohort of adults. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(4):e011295. doi:10.1161/JAHA.118.011295

- Wong ND, Budoff MJ, Ferdinand K, et al. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk assessment: an American Society for Preventive Cardiology clinical practice statement. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2022;10:100335. doi:10.1016/j.ajpc.2022.100335

- Mbanya JC, Motala AA, Sobngwi E, Assah FK, Enoru ST. Diabetes in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet. 2010;375(9733):2254–2266. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60550-8

- Mayige M, Kagaruki G, Ramaiya K, Swai A. Non communicable diseases in Tanzania: a call for urgent action. Tanzan J Health Res. 2011;13(5 Suppl 1):378–386. doi:10.4314/thrb.v13i5.7

- Mfinangai SG, Kivuyo SL, Ezekiel L, Ngadaya E, Mghamba J, Ramaiya K. Public health concern and initiatives on the priority action towards non-communicable diseases in Tanzania. Tanzan J Health Res. 2011;13(5 Suppl 1):365–377.

- Chillo P, Mashili F, Kwesigabo G, Ruggajo P, Kamuhabwa A. Developing a sustainable cardiovascular disease research strategy in Tanzania through training: leveraging from the East African Centre of Excellence in cardiovascular sciences project. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:849007. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2022.849007

- Polonsky TS, Khera A, Miedema MD, Schocken DD, Wilson PWF. Highlights in ASCVD primary prevention for 2021. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11(13):e025973. doi:10.1161/JAHA.122.025973

- DeFilippis AP, Young R, Carrubba CJ, et al. An analysis of calibration and discrimination among multiple cardiovascular risk scores in a modern multiethnic cohort. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(4):266–275. doi:10.7326/M14-1281

- Bazo-Alvarez JC, Quispe R, Peralta F, et al. Agreement between cardiovascular disease risk scores in resource-limited settings: evidence from 5 Peruvian sites. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2015;14(2):74–80. doi:10.1097/HPC.0000000000000045

- Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139(25):e1082–e143. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000625

- Goff DC, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 Suppl 2):S49–S73. doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000437741.48606.98

- Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140(11):e596–e646. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678

- Clark AM, DesMeules M, Luo W, Duncan AS, Wielgosz A. Socioeconomic status and cardiovascular disease: risks and implications for care. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6(11):712–722. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2009.163

- Minja NW, Nakagaayi D, Aliku T, et al. Cardiovascular diseases in Africa in the twenty-first century: gaps and priorities going forward. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:1008335. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2022.1008335

- Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(24):3168–3209. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.002

- Martin-Timon I, Sevillano-Collantes C, Segura-Galindo A, Del Canizo-Gomez FJ. Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease: have all risk factors the same strength? World J Diabetes. 2014;5(4):444–470. doi:10.4239/wjd.v5.i4.444

- Lopaschuk GD, Verma S. Mechanisms of cardiovascular benefits of Sodium Glucose Co-Transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors: a state-of-the-art review. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2020;5(6):632–644. doi:10.1016/j.jacbts.2020.02.004

- Kyriakos G, Quiles-Sanchez LV, Garmpi A, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors and cardiovascular outcomes: do they differ or there is a class effect? New insights from the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial and the CVD-REAL study. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2020;16(4):258–265. doi:10.2174/1573403X15666190730094215

- Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):311–322. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1603827

- Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, et al. Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND): a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10193):121–130. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31149-3

- Kanie T, Mizuno A, Takaoka Y, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists and sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors for people with cardiovascular disease: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;10:CD013650. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013650.pub2

- Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Whincup PH, Lennon L, Sattar N. Impact of diabetes on cardiovascular disease risk and all-cause mortality in older men: influence of age at onset, diabetes duration, and established and novel risk factors. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(5):404–410. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.2

- Banerjee C, Moon YP, Paik MC, et al. Duration of diabetes and risk of ischemic stroke: the Northern Manhattan Study. Stroke. 2012;43(5):1212–1217. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.641381

- Soyoye DO, Abiodun OO, Ikem RT, Kolawole BA, Akintomide AO. Diabetes and peripheral artery disease: a review. World J Diabetes. 2021;12(6):827–838. doi:10.4239/wjd.v12.i6.827

- Sarwar N, Gao P, Seshasai SR, et al.; Emerging Risk Factors C. Diabetes mellitus, fasting blood glucose concentration, and risk of vascular disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of 102 prospective studies. Lancet. 2010;375(9733):2215–2222. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60484-9

- Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Perry IJ. Serum creatinine concentration and risk of cardiovascular disease: a possible marker for increased risk of stroke. Stroke. 1997;28(3):557–563. doi:10.1161/01.STR.28.3.557

- Mlekusch W, Exner M, Sabeti S, et al. Serum creatinine predicts mortality in patients with peripheral artery disease: influence of diabetes and hypertension. Atherosclerosis. 2004;175(2):361–367. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.04.008

- Schneider C, Coll B, Jick SS, Meier CR. Doubling of serum creatinine and the risk of cardiovascular outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cohort study. Clin Epidemiol. 2016;8:177–184. doi:10.2147/CLEP.S107060

- Gansevoort RT, Correa-Rotter R, Hemmelgarn BR, et al. Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular risk: epidemiology, mechanisms, and prevention. Lancet. 2013;382(9889):339–352. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60595-4

- National Kidney F. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(2 Suppl 1):S1–S266.

- Weir MR. Microalbuminuria and cardiovascular disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(3):581–590. doi:10.2215/CJN.03190906

- Palmer SC, Craig JC, Navaneethan SD, Tonelli M, Pellegrini F, Strippoli GF. Benefits and harms of statin therapy for persons with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(4):263–275. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-4-201208210-00007

- Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364(9438):937–952. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9

- Ference BA, Ginsberg HN, Graham I, et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(32):2459–2472. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx144

- Mihaylova B, Emberson J, Blackwell L, et al.; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists C. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials. Lancet. 2012;380(9841):581–590.