Abstract

Many European societies follow pronatalist family policies; nevertheless, in all countries, the total fertility rate is below replacement level and the rate of childless people is growing. Meanwhile, among demographers and policymakers, immigration is discussed as a way to increase the labor force and recently also to maintain the population size. This study contributes to a better understanding of individuals’ attitudes on these issues by examining the factors that influence the acceptance of immigration from the prism of attitudes toward voluntary childlessness. Attitudes toward immigrants as well as attitudes toward voluntary childlessness vary across and within European societies. From a selective pronatalist perspective, both factors might threaten the survival of the nation. Therefore, in this study, we assess the extent to which attitudes toward voluntary childlessness relate to attitudes toward immigrants. We differentiate attitudes toward immigrants as an economic and as a cultural threat. We use data from the European Social Survey (Round 9) and apply multilevel linear regression models. Our results show that there is a strong association between the acceptance of immigrants and voluntary childlessness at the individual level. At the country level, the female childlessness rate is associated with attitudes toward immigration: higher female childlessness rates are associated with more favorable attitudes toward immigration.

Introduction

This study unfolds the link between an increasingly relevant dimension of the pronatalism concept, namely whether attitudes toward voluntarily childless individuals and attitudes toward immigration. Across social science disciplines, the term ‘pronatalism’ has different conceptual connotations. From a demographic perspective, all policies that encourage childbearing are pronatalist policies (Gietel-Basten, Rotkirch, and Sobotka Citation2022). Historically, pronatalist policies were one of the two main pillars of population policies, the other being immigration policy, and the two worked side by side, not against each other (Marois, Bélanger, and Lutz Citation2020). In political science, pronatalism is considered as a political discourse that promotes and glorifies parenthood and having children, often to the point of considering it a moral duty or imperative (Yuval-Davis Citation1997). Hašková and Dudová (Citation2020) draw attention to the ideological approach of pronatalism, since pronatalism is often connected to nativism and anti-immigration fears through pronatalist discourses. Better understanding of this relationship is important with respect to current societal functioning for a number of reasons. First, studying the relationship between attitudes toward immigrants and attitudes toward voluntary childlessness is important because immigration can counterbalance lower fertility rates. Second, immigrants and voluntarily childless individuals are sometimes targets of societal exclusion and stigmatization in pronatalist and anti-immigrant societies (Harrington Citation2019; Creighton and Jamal Citation2022). Third, it is essential to understand whether individuals who reject voluntary childlessness also reject immigration to grasp the potential reasons behind the exclusion and stigmatization of immigrants and to develop strategies for preventing such stigmatization. Finally, we broaden existing theories of pronatalism by examining the link between the two issues. While there is a general understanding that population decline and immigration are two of the most pressing demographic challenges, attitudes toward both have hardly been analyzed (Ceobanu and Koropeckyj-Cox Citation2013) and have not been analyzed in a framework as suggested by the present study. This gap is surprising given that prior research has clearly identified attitudes as crucial factors for policy making (Dražanová Citation2022).

In this article, we address the following research question: Is there a link between attitudes toward voluntary childlessness and attitudes toward immigrants in European societies and how do European regions differ in this respect? To answer these questions, we analyze data from the European Social Survey (ESS) Round 9 from 2018. The ESS measured attitudes toward voluntary childlessness by asking the question: How much do you approve or disapprove if a woman/man chooses never to have children? A split-sample design was applied, and respondents answered only one version of the item: half of them were surveyed concerning the norm for women (but not for men) and half concerning the norm for men (but not for women). The ESS measured attitudes toward immigration in two dimensions: concerning the economic dimension the following question was asked: Would you say it is generally bad or good for [country]’s economy that people come to live here from other countries? And concerning the cultural dimension the following question was asked: Would you say that [country]’s cultural life is generally undermined or enriched by people coming to live here from other countries?

This exploratory study brings together two important current demographic trends: migration and voluntary childlessness. It takes an attitudinal perspective and examines whether and how attitudes toward voluntary childlessness are related to the differences in attitudes toward immigrants. Two dimensions of attitudes toward immigrants are distinguished, those from an economic and those from a cultural perspective. Previous studies have shown that both are influenced by the economic environment of a given country and the social and economic situation of a given individual (Hainmueller and Hiscox Citation2007; Davidov and Meuleman Citation2012; Ceobanu and Koropeckyj-Cox Citation2013). Yet so far neither the economic nor the cultural dimension have been studied in relation to voluntary childlessness.

The next sections proceed as follows: First, we describe the theoretical framework of how attitudes toward voluntary childlessness predict attitudes toward immigration in its economic and cultural dimension. The theoretical framework consists of three parts, namely (1) the significance of pronatalist and immigration discourses in Europe, (2) fertility and immigration policies, and (3) theoretical considerations on the relationship between attitudes toward voluntary childlessness and attitudes toward immigration. We then describe the data, sample and method, before presenting the empirical results. These results are discussed in the final part.

Background: attitudes toward voluntary childlessness as a predictor of attitudes toward immigration

The relationship between attitudes to migration and voluntary childlessness has not been examined before. Previous theories have linked the phenomenon of migration with low fertility. First, a UN report in 2000 mentioned the concept of replacement migration which is needed to maintain the size of the total population and the size of the working-age population. There were lots of reactions to this report and Coleman (Citation2002) considered that the report dismissed negative implications of high immigrant inflows such as social conflict between natives and immigrants. Then, Coleman (Citation2006) developed the Third Demographic Transition theory which claims that replacement migration is inevitable, and he further stipulated that it had started in Western Europe and the United States.

However, none of the above-mentioned approaches considered attitudes. These theories only account for actual migration and fertility rates. Public attitudes which refer to sentiments and dispositions of the population with respect to replacement migration have rarely been examined empirically. Ceobanu and Koropeckyj-Cox (Citation2013) study is an exception. They examined cross-country variation in public attitudes toward replacement migration for counteracting population aging, although they also confirmed that attitudes about replacement migration are correlated with more general attitudes toward immigration. Their results showed that childless individuals are more comfortable with immigration-focused population policies than with pronatalism as a solution to the problems of population aging (Ceobanu and Koropeckyj-Cox Citation2013). For individuals with children the opposite holds. Comparing childless and non-childless individuals is new because until then attitudes of childless individuals received little attention in the literature on attitudes about immigration. At the same time, rising proportions of childless adults and increased acceptance of those without children in many European countries (Sobotka and Testa Citation2008; Merz and Liefbroer Citation2012) are likely to influence debates about future population policies (Ceobanu and Koropeckyj-Cox Citation2013).

In this study, we examine this gap, the relationship between attitudes related to migration and attitudes related to voluntary childlessness. For this, we review the literature on political discourses, policies, and attitudes on migration and voluntary childlessness.

The significance of pronatalist and immigration discourses in Europe

Political discourses surrounding declining fertility are led in all of Europe (De Zordo, Marre, and Smietana Citation2022). In a recent study, Pető et al. (Citation2022) have shown that political debates on demography continue to gain in importance within the European Union. Low fertility is a societal challenge across Europe (Saczuk Citation2013; May Citation2015; Lutz et al. Citation2019). Since the growing proportion of individuals aged 65 and older in relation to the total population, the so-called old-age dependency ratio, which causes a lack of labor supply in Europe and puts many national pension systems at risk. Consequently, many European countries rely on immigration to cover their declining labor forces and to sustain their economies (Saczuk Citation2013; May Citation2015). While immigration can economically be useful to compensate for declining population numbers (Morgan Citation2003; Begall and Mills Citation2011; Sobotka, Skirbekk, and Philipov Citation2011; May Citation2015), it can also “make substantial, presumably permanent, changes to the ethnic and religious make-up of Western receiving count” (Coleman Citation2009:451). Yet, culturally this represents challenges in some countries, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) which are ethnically more homogeneous, and these countries have relatively low levels of immigration such as Czechia, Poland, and Hungary (Vachudova Citation2020).

In the political discourse, below replacement level fertility is part of the political agenda and many governments have sought to find a demographic solution: to raise birth rates with a promotion of conservative family values, where women have a duty and responsibility to bear children and thus secure the future of the nation (Gietel-Basten et al. Citation2022:2). Although immigration can slow the pace of population aging and counter fertility decline, this solution is not accepted by everyone among the European political elite (Coleman Citation2002). These differences caused different discourses about migration. In some countries, such as Germany and Sweden, the main discourse puts forward human rights issues (Lyck-Bowen and Owen Citation2019). In other countries, like Hungary, the discourse about immigrants is linked to issues of the survival of the nation. In some European countries, a decrease in fertility rates among socially dominant groups has been used by right-wing politicians to fuel anti-immigrant and other xenophobic sentiments (Pető et al. Citation2022). In this political discourse not wanting to have children is not acceptable as it endangers the survival of the nation.

Discourses directly impact attitudes of citizens in the respective countries. Prior cross-sectional research found that exclusionary political elites are associated with more hostile public opinion (Hjerm Citation2007; Bohman Citation2011), while openness toward newcomers is more common in countries with inclusionary political elites (Czymara Citation2020). Mitchell (Citation2021) has shown that anti-immigration attitudes are higher in countries with patriotic and nationalistic political elites. Across Europe, discourses are more heterogeneous with respect to migration as compared to pronatalism.

Fertility and immigration policies

Within European societies, pronatalist and immigration policies are very diverse (Höhn Citation1988). While the aim of fertility policies is the same: to increase the number of births in Europe, governments try to reach that objective with different family policies. Regarding immigration policy there is no common goal in Europe.

Fertility policies in Europe

Low fertility rates and population aging are challenges that affect most developed countries (Thévenon Citation2011; Muthuta and Laoswatchaikul Citation2022). To counteract them, national governments use a variety of family policy instruments. Yet, European countries emphasize different areas of family support, and the proximity of countries to each other increases the similarity in their fertility policies (Thévenon Citation2011).

In the Nordic countries, they try to increase fertility by improving and maintaining gender equality, supporting women’s reentry into the labor market by helping them to reconcile work and private life, and emphasizing the involvement of fathers in child-rearing (Duvander, Lappegård, and Andersson Citation2010; Thévenon Citation2011). Meanwhile in the Continental European countries they employ explicit types of family support, which primarily imply a high level of financial support through benefits and tax exemption (Thévenon Citation2011; Muthuta and Laoswatchaikul Citation2022). Furthermore, in the CEE countries also have pronatalist family policies, but these countries place more emphasis on traditional family values and gender roles to stimulate fertility while they place less emphasis on gender equality and on reconciling women’s work and private lives (Thévenon Citation2011; Frejka et al. Citation2016; Szalma et al. Citation2022).Footnote1 Thus, in CEE countries voluntary childlessness is less accepted than in the Nordic or Western European countries because it contradicts traditional family values (Merz and Liefbroer Citation2012).

Migration policies in Europe

The migration policies have been very heterogeneous in European countries and an unexpected large number immigration inflow into Europe in 2015 brought these differences to the surface. The handling and experiences of this influx differed across countries. There have been noteworthy differences in various European countries’ willingness to help newly arrived people. Countries such as Sweden and Germany have generally emphasized the humanitarian imperative to help and welcome migrants, whereas others including Hungary, Poland and the UK have been notably more skeptical and reluctant to open their borders (Lyck-Bowen and Owen Citation2019:22). This inflow of immigrants into Europe triggered debates about who can become a citizen. Obtaining citizenship is also very different in the countries of Europe. Citizenship policy in the scientific literature is taken as an outcome of inclusive versus exclusive national self-understandings (Simonsen Citation2017). Obtaining citizenship is much more difficult for migrants than obtaining a residence permit, because with this, European states are not protecting their territory; rather they are managing the boundaries of national membership (Wimmer Citation2013). Thus, in countries where citizenship can be obtained more easily the attitude toward immigrants can also be more favorable (Koopmans, Michalowski, and Waibel Citation2012).

Attitudes toward immigrants and voluntary childlessness

Attitudes refer to the sentiments and dispositions of the population with respect to a specific social issue. The results of previous research suggest that the most decisive indicator of attitudes toward immigrants is the sense of threat attributed to a given immigrant community (Hellwig and Sinno Citation2017; Heath et al. Citation2020). The threats attributed to certain types of immigrants, or even to immigrants altogether, can be of several types. On the one hand, threats can be interpreted in economic terms, which in most cases means that the person feels their livelihood and position in the labor market is threatened by the influx of new workers (Hellwig and Sinno Citation2017). However, the feeling of economic threat can arise not only from the individual’s own personal situation, but also from the situation of his or her social group, meaning that it can exist if the individual feels that his or her own social group is unjustly deprived of opportunities because of the immigrants (Meuleman et al. Citation2020 cited in Heath et al. Citation2020). According to Gorodzeisky and Semyonov (Citation2016), the increased labor force formed by immigrants can pose a so-called competitive threat to the society of a given country. This competitive threat arises from two main sources: the economic environment of a given country and the social and economic situation of a given individual (Gallego and Pardos-Prado Citation2014).

Besides economic reasons for not supporting migration there are also cultural ones, where individuals feel that immigrants endanger their native culture and identity (Markaki and Longhi Citation2013; Gorodzeisky and Semyonov Citation2016). These include reasons such as racism, xenophobia and milder forms of nationalist sentiments such as social norms or cultural preferences (O’Rourke and Sinnott Citation2006). Some individuals feel threatened by migrants whom they perceive as having different views on important societal issues such as democracy, homosexuality, religion, or women’s emancipation that relate to voluntary childlessness and thereby impact a country’s culture and values (Glas Citation2023).

Individuals worldwide seem to increasingly consider voluntary childlessness (i.e. the choice not to have any children) as an alternative to parenthood. Hence, not having children is no longer as unusual as it was in the past (Albertini and Brini Citation2021). According to empirical research attitudes toward voluntary childlessness are more favorable among women, higher educated, less religious, and those who are employed (Koropeckyj-Cox and Pendell Citation2007; Rijken and Merz Citation2014). However, Europe cannot be considered homogeneous: The highest approval rates related to childlessness were found in Northern and Western European countries, while the lowest approval rates were found in formerly communist Eastern European countries. Attitudes toward voluntary childlessness have been the topic of multiple studies (Merz and Liefbroer Citation2012; Rijken and Merz Citation2014) but have never been linked to migration-related attitudes. The aim of this research is to explore the relationship between attitudes toward voluntary childlessness and attitudes toward immigrants.

Data and measures

Data

To analyze societal attitudes toward voluntary childlessness, we analyze data from the ESS. The ESS is a repeated cross-sectional survey conducted in more than 30 European countries, focusing on societal attitudes and values using face-to-face interviews (Stoop et al. Citation2010). It consists of core modules that are largely identical across rounds and rotating modules which are dedicated to specific themes. The “Timing of life” module that includes questions on attitudes toward voluntary childlessness was conducted in wave 3 (ESS3) (2006, 25 countries) and aims at understanding the views of European citizens on the organization of the life course and their strategies to influence and plan their own life. It was repeated 12 years later as part of the ESS9 in 2018. In this study, we analyze the data from the ESS9.

The dataset includes information on 48,658 respondents from 28 national random samples collected through face-to-face interviews.Footnote2 After deleting cases with missing values on our variables of interest, our analysis sample consists of 43,954 individuals.Footnote3 The following countries are included: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Cyprus, Denmark, Estonia, France, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. This set of countries allows us to exploit variation in terms of immigration histories, size and composition of immigrant groups, immigration policies, as well as demographic characteristics such as populations’ fertility and childlessness rates and old-age dependency ratio.

Measures

Micro-level variables

The dependent variables assess attitudes toward immigration in terms of economic and cultural threats. The one relating to economic threat is measured by the question: Would you say it is generally bad or good for [country]’s economy that people come to live here from other countries? The responses were given on an eleven-point scale (0 = bad for the economy; 10 = good for the economy). Attitudes toward immigration in terms of cultural threat is measured by the question: Would you say that [country]’s cultural life is generally undermined or enriched by people coming to live here from other countries? Again, responses were given on an eleven-point scale (0 = the country’s cultural life is generally undermined; 10 = cultural life is generally enriched). For both items, respondents were given the option not to answer. However, the non-response rate was below 4% for both items. We dropped these respondents from the analysis sample. Individuals who did not answer these items are older, lower educated and more religious than those who answered. Moreover, they have less favorable attitudes toward voluntary childlessness than those who answered the items. Overall, those who do not respond to the attitude-question are more similar to those who are rather in favor of the statements that immigration is bad for a country’s economy and undermines cultural life.

Our main explanatory variable is the attitudes toward voluntary childlessness. It was asked with the following item: How much do you approve or disapprove if a woman/man chooses never to have children? Response options ranged from 1 (strongly disapprove) to 5 (strongly approve). Due to space limitations, a split ballot design was used to measure the attitude. About half (N = 21,680) of the respondents were asked the question concerning men and the other half (N = 22,274) were asked that question concerning women. Previous literature did not find different attitudes toward female and male voluntary childlessness, but they did find that the gender of the respondent matters (Rijken and Merz Citation2014). However, to control this design effect, we involved the variable which indicates that the item was related to male or female voluntary childlessness.

Based on the literature, we include the following individual socio-demographic variables: gender (male = 1; female = 2). There is no difference between males and females with respect to attitudes toward immigration (Davidov and Meuleman Citation2012). Regarding age we created the following age group (16–30, 31–45, 46–60, 61 and over). Previous studies found that older persons who have spent a long time living in a particular kind of society may have more difficulty accepting change related to new customs caused by migration processes (O’Rourke and Sinnott Citation2006).

We controlled for attendance of religious services (at least once a week, at least once a month, only on special holy days, less often, never). More religious individuals have a somewhat lower tendency to reject immigration (Davidov and Meuleman Citation2012).

Level of educational attainment was included (low < ISCED3, medium = ISCED 4/ISCED = 5, high = ISCED5/ISCED6). Many studies showed that educated individuals have a lower tendency to reject immigration (Semyonov, Raijman, and Gorodzeisky Citation2006; Cavaille and Marshall Citation2019). As for labor force status we created the following categories: active = 1, non-active = 2 (unemployed, in education, permanently sick or disabled, housework, looking after children), retired = 3.

To measure the political views (ranging from left-wing orientation to right-wing orientation) were also included in this set of explanatory variables. We recoded the political orientation measurement Where would you place yourself on this scale, where 0 means the left and 10 means the right? in the following way: 0–2 recoded into 1 = left-wing oriented, 3–4 recoded into 2 = slightly left-wing oriented, 5 recoded into 3 = neutral, 6–7 recoded into 4 = slightly right-wing oriented, 8–10 recoded into 5 = right-wing oriented. For this variable, the nonresponse rate exceeded 5%. Therefore, we defined a separate category for respondents who refused to respond for this item. Previous literature found that negative attitudes toward immigration would be more pronounced among a right-wing political orientation (Semyonov et al. Citation2006).

Additionally, we included a variable which was rarely analyzed in previous empirical studies; namely, having children (0 = no child 1 = having one or more). Previous study found that childless people have more favorable attitudes toward immigrants (Ceobanu and Koropeckyj-Cox Citation2013).

The sample characteristics for the individual-level variables are summarized in showing the descriptive statistics of the key variables.

Table 1. Variables and summary statistics, ESS Round 9.

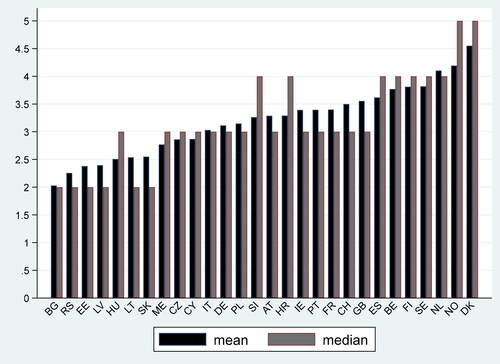

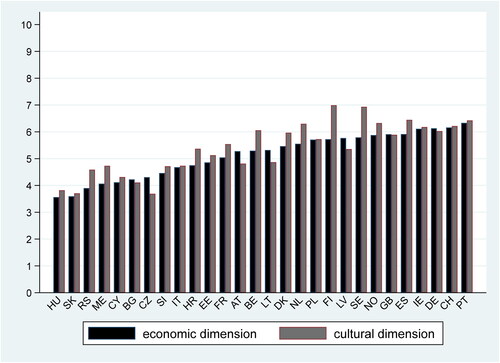

Regarding the social attitudes toward voluntary childlessness there are variances both among individuals (the standard deviation is above one at a five-point scale) and cross-countries (see in the Appendix). Regarding attitudes toward immigrants, we observe differences among individuals (standard deviation is 2.55 in the economic dimension and 2.66 in the cultural dimension) and by countries (see in the Appendix).

Macro-level variables

We include three country-level variables: female childlessness rate, migration rate and one question about migration policy which was measured by the MIPEX. The female childlessness rate was calculated from the database in the following way: a country’s percentage of women aged 40 and older without children. Migration rate was measured as international migrant stock as a percentage of the total population (United Nations 2020). Some studies report that greater numbers of migrants are associated with more negative attitudes (Quillian Citation1995; Semyonov et al. Citation2006), others fail to find such correlations (Semyonov et al. Citation2004; Hjerm Citation2007; Sides and Citrin Citation2007; Pottie-Sherman and Wilkes 2017). While Czymara (Citation2020) found that higher numbers of immigrants are associated with less negative attitudes.

The third macro-level variable regarding migration policy measures the immigrants’ access to nationality. The index is between 0 and 100 where 100 means that it is very easy to become a citizen of the given country and 0 means it is not possible to become a citizen of the country. Among the examined countries, it is easiest to become a citizen in Portugal (86), Sweden (83), and Ireland (79). While it is most difficult to get citizenship in Austria (13), Bulgaria (13), and Estonia (16).

Based on the main concepts, attitudes toward immigrants and attitudes toward voluntary childlessness, we categorize the country groups according to Merz and Liefbroer (Citation2012)’s concept of various attitudes toward voluntary childlessness and reflecting of the past migration histories and contemporary (political) discourses on immigration (Kunovich Citation2004; Bail Citation2008; Heath and Richards Citation2020). We grouped the 28 countries into four groups: Western European countries (Austria, Belgium, Germany, France, Great Britain, Ireland, the Netherlands, and Switzerland), Nordic European countries (Finland, Denmark, Norway, Sweden), the Southern European countries (Cyprus, Spain, Italy, Portugal), and CEE countries (Bulgaria, Estonia, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Montenegro, Poland, Serbia, Slovakia, and Slovenia).

Analytical models

To assess the association between the individual and contextual characteristics with the dependent variables, the analyses are modeled as a two-level structure, with individuals nested within countries. Multilevel linear regression also allows estimating how much of the total variation in the model is due to the variation at the aggregate level, that is, how strong the contextual influence is. This is estimated by the intraclass correlation (ICC) (Hayes Citation2006; Hox, Moerbeek, and Van De Schoort Citation2017).

We applied several models starting from the less complex (two-level intercept models) to check the robustness of the models and to identify the best fit. The likelihood ratio test suggests that the two-level (individual- and country-level) random slope model provides the most realistic picture of the actual situation. Hence, we allow the slope to vary across individuals and to be predicted by the covariates presented above. We allow the attitudes toward voluntary childlessness to vary among countries as we observe considerable differences across countries.

We estimated six multilevel models for both dependent variables. First, to estimate the ICC, we have conducted an analysis with the random intercept only (empty model). Next, we have conducted multilevel regressions including all individual-level control variables and the attitudes toward voluntary childlessness variable (model A). In model B, we added the country-group variable as well. In model C we included female childlessness rate, in model D we replaced the female childlessness rate with and migration rate and controlled for all individual level variables. In model F we added migration policyFootnote4 as a country level variable to model A. Finally, in model F we involved all the three contextual variables and the individual level variables.

We used the design weight in all the models.

Results

Within Europe there is considerable variation in terms of both attitudes toward voluntary childlessness and immigrants (see and in the Appendix). The lowest average for voluntary childlessness is in Bulgaria, followed by Serbia, Estonia, and Lithuania. While individuals in the Nordic countries (Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Finland) and the Netherlands are the most accepting of voluntary childlessness. With respect to immigration, there is not so much separation between groups of countries. Although Eastern European countries are less accepting of migrants, the same is true with respect to Cyprus, which belongs to the Southern group. The most accepting countries include Southern and Western European countries, such as Portugal, Switzerland, Germany, Ireland, and Spain. and present the results from multilevel models predicting respondents’ attitudes toward immigration in two dimensions.

Table 2. Results of the multivariate analysis: predicting attitudes toward migration in economic dimension.

Table 3. Results of the multivariate analysis: predicting attitudes toward migration in cultural dimension.

Attitudes toward voluntary childlessness as predictors of attitudes toward immigrants

Model A contains the individual-level control variables including individuals’ attitudes toward voluntary childlessness. As expected, attitudes toward voluntary childlessness significantly predict both dimensions of attitudes toward immigration, that is, the economic and the cultural dimension. Those who have more unfavorable attitudes toward voluntary childlessness are more likely to agree that migration has a negative effect on the country’s economy and the country’s cultural life compared to those who have neutral attitudes toward voluntary childlessness. On the other hand, those who strongly approve that someone chooses to never have children are more likely to agree that migration has a positive effect on the country’s economy and the country’s cultural lives compared to those who have neutral attitudes toward voluntary childlessness.

In Model B we add the country groups. In line with our expectations, in the CEE countries attitudes toward immigration in both dimensions are significantly more negative than in the Western European countries. At the same time, Northern European countries and Southern European countries do not differ significantly from Western European countries in terms of attitudes toward immigration in either dimension. In this model, the country level variance (see ICC) decreased considerably indicating that a large part of the variance comes from the country groups.

In Model C, we included female childlessness rate and, in both models, we find that the higher the female childlessness rates the higher the acceptance of immigration in both dimensions.

In Model D we included the migration rate instead of female childlessness rate. Regarding migration rate, there was a significant effect. We found that the high migration rate links to more favorable attitudes toward immigrants in both the economic and in the cultural dimensions. This positive association coincides with the result of a previous study (see, e.g. Czymara Citation2020).

In Model E we included the third contextual variable: Access to citizenship. We found a significant relationship between access to citizenship attitudes toward immigrants in both dimensions. In those countries where access to citizenship is easier, people are more likely to agree that immigration is good for the country’s economy and enriches the country’s culture.

Finally, in Model F we involved all the three contextual variables and the country groups, as well. The associations of individual variables did not change, in fact, they seemed very robust. The country groups are not significant in either of the models. At the same time, the three contextual variables are not significant in the economic dimension models while they are significant in the cultural model.

Observations on control variables

With respect to the covariates some important observations are revealed in and . The target group, gender, age, attendance of religious service, parental status, education, employment, and left-right political view predicts attitudes toward immigrants.

Men hold more positive views on migration in the economic dimension compared to women. However, if we examine immigration-related attitudes in the cultural dimension there is no significant differences between men and women. This is consistent with Dustmann and Preston’s (Citation2000) research who found that women are more hostile toward immigrants in the economic dimension of attitudes toward immigrants because women’s position in the labor market is, in general, more vulnerable than that of men (OECD Citation2021). Therefore, women are more likely to express concern over the impact of an immigrant labor force on the job market.

As for the age groups we found that the younger age group (15–30) have more favorable attitudes toward immigrants in both dimensions than the 45–60-year-olds (reference group). However, those who belong to the oldest age group do not have significantly more negative attitudes than the reference group. It might be due to the fact that we involved the pensioner category in the employment status, and it absorbs some of the significant association. Interestingly the religious individuals (those who attend the church at least one a week) report more favorable attitudes toward immigration than less religious ones in both dimensions. The role of religiosity on attitudes toward immigrants are very mixed in previous studies. Since previous research has found religiosity to play a positive effect on attitudes to immigration (Bohman and Hjerm Citation2014). On the other hand, religiosity is often linked to conservativism, right-wing political views and even pronatalism, thus less positive attitudes toward immigration, as well as, on the contrary, others who find that greater religiosity leads to more prejudice toward immigrants (Scheepers, Gijsberts, and Coenders Citation2002).

Education level is significant in both models. In line with the literature, higher-educated respondents have more supportive attitudes toward immigrants than lower-educated individuals. The activity status is not significant.

Furthermore, those who have right-wing attitudes have the least favorable attitudes toward migration than those who placed themselves at the neutral scale in both cultural and economic dimensions. At the same time those who belong to the left-wing political orientation have more favorable attitudes toward immigration than those who are neutral in both dimensions. This coincides with previous literature (Dražanová Citation2022).

These results are robust across the different models and consistent with previous empirical research.

Robustness checks

To verify the robustness of the above results, we have carried out several sensitivity analyses. The most important ones are reported here. First, we have estimated Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) ( in the Appendix) and fixed effect models ( in the Appendix); the results for the micro level variables differ only slightly from what we found above. Women have a more favorable attitude toward immigration than men in the cultural dimension, meanwhile in the multilevel model this association was not significant. The other difference is that those who belong to the oldest age group have more favorable attitudes toward immigration than the reference category in the economic dimension. However, in the model, individuals who are retired have less favorable attitudes than those who are active in the labor market.

As for the contextual variables, we found that not only did CEE countries exhibit significant differences from the reference category, but Northern and Southern countries also have less favorable attitudes toward immigration in the economic dimension. Meanwhile, the Northern countries have more favorable attitudes than Western European countries in the cultural dimension. When the three contextual variables were included step by step, we observed the same relationship as in the multilevel model. However, in the full model, the female childless rate became negative which may indicate some collinearity among the variables in the OLS model.

As for the fixed effect model, we found significant differences among genders in the cultural dimension: women held more favorable attitudes toward immigration than men. Furthermore, in the cultural models, employment status was significant: those who were inactive had more favorable attitudes toward immigrants than those who were active in the labor market. This is probably because students are involved in this category, and they showed more favorable attitudes. While retired individuals were more likely to have unfavorable attitudes toward immigrants in this dimension.

We also conducted multilevel linear random effect models in which we did not include two independent variables that are probably closely linked to not only the attitudes toward immigration but also to attitudes toward childlessness: political views and religiosity. Our results showed that, the with the exclusion of these variables, the associations with the other variables remain the same (results are not shown).

Overall, the sensitivity analyses indicate that the results are robust over several model specifications although the coefficients for the country groups are more pronounced in the OLS regressions.

Conclusion

Across Europe, population aging is a pressing issue, which is mainly due to low fertility rates (Sobotka Citation2004) and a rising proportion of individuals choosing not to have children (Kreyenfeld and Konietzka Citation2017). Despite the absence of consensus on how to address population aging, at least two scenarios have been proposed (Gietel-Basten et al. Citation2022).

One approach is the concept of pronatalist policies, where family policies emphasize the necessity for and encourage fertility growth based on the assumption that the population’s size is insufficient, posing a risk to the population. This perspective is particularly popular in CEE countries (Kotzeva and Dimitrova Citation2014; Melegh Citation2016; Hašková and Dudová Citation2021). In this scenario, voluntary childlessness is often perceived as a breach of societal norms (Harrington Citation2019; Mccutcheon Citation2020). In many CEE countries, this perception is intensified by the fact that while the fertility rate is low, the childlessness rate also remains low due to the social expectation that each couple should have at least one child (Zeman et al. Citation2018). An alternative concept is replacement migration, which gained popularity following the publication of a UN report in 2000 (United Nations Citation2000). According to this report, replacement migration is deemed necessary to sustain the overall population size and the size of the working-age population. Therefore, it is crucial to understand individuals’ attitudes toward these two phenomena and to explore the relationship between them. Previous studies have predominantly focused on socio-demographic variables to explain negative attitudes toward immigrants. Ceobanu and Koropeckyj-Cox (Citation2013) research was pioneering in examining attitudes toward replacement migration and they found that childless individuals are consistently more likely than others to endorse replacement migration. Our study affirms that childless individuals have more favorable attitudes toward immigrants in both the cultural and economic dimensions. In addition, we also scrutinized attitudes toward immigrants in terms of economic and cultural dimensions, as well as attitudes toward voluntary childlessness, revealing a positive association between both dimensions of acceptance of immigration and acceptance of voluntary childlessness.

At the macro level, we also observed that higher childlessness rates are linked to more favorable attitudes toward migration in both the economic and cultural dimensions. Additionally, migration rates are positively associated with acceptance of immigrants in both dimensions. Higher levels of immigration can lead to increased public support for immigration. This finding contradicts some previous studies (e.g. Quillian Citation1995; Scheepers et al. Citation2002; Semyonov et al. Citation2006) but aligns with recent research that also identified a positive association between migration rates and attitudes toward immigrants (Czymara Citation2020). The mixed evidence could stem from methodological issues, such as the specific operationalization of contextual variables or the inclusion of different countries in the studies. Nevertheless, our results align with Czymara’s (Citation2020) assumption that during the migration crisis of 2015, immigrants tended to go to countries where they were more readily accepted, explaining the observed positive correlation. Until now, the scientific literature has seldomly delved into individual attitudes toward pronatalist policies and replacement migration. With this study, we contribute to a better understanding of individuals’ attitudes in this area by examining the factors that influence the acceptance of immigration through the lens of attitudes toward voluntary childlessness. We define the rejection of voluntary childlessness as one of the dimensions of pronatalism. In the future, family lives will be more diversified, including increasing numbers of voluntarily childless couples and individuals. Moreover, across Europe, there will likely be an increase in immigration from less developed countries, which implies an increasing cultural distance between natives and immigrants (Coleman Citation2006). Therefore, policies that stress that cultural diversity does not pose a threat to a nation’s cultural identity, and voluntary childlessness is not equal to endangering the nation’s survival are crucial. The formal education sector, but also the media, could contribute to the promotion of knowledge of foreign and different cultures and the value they bring. The introduction of awareness policies regarding accepting cultural diversity and reproductive autonomy is especially crucial in the CEE countries where the cultural threat and survival of the nation discourse are most pronounced.

Despite its contributions, this research has some limitations. One is that we have only one variable to measure attitudes toward voluntary childlessness, which is based on a general question. However, individuals may give different answers to slightly different attitude questions such as their attitudes toward voluntary childlessness if it takes place in their own environment or if they are asked whether having children is a duty toward our society or not. The attitude measures concerning immigration also yield limited information since the data source did not allow us to take where the immigrants come from into account. Future data collections ought to be enhanced to avoid these limitations. Given the evidence we found regarding attitudes toward voluntary childlessness and attitudes toward immigrants in various dimensions, it would be worthwhile to conduct further analyses using qualitative and mixed methods. This approach would contribute to a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ivett Szalma

Ivett Szalma (PhD) is the principal investigator of the Momentum Reproductive Sociology Research Group at the HUN-REN Center for Social Sciences and an associate professor at the Corvinus University of Budapest. Her research topics include childlessness, attitudes toward assisted reproduction technology, adoption by same‐sex couples, non‐resident fatherhood, and measurement of homophobia.

Marieke Heers

Marieke Heers is the Head of the Data Archive Services at FORS, the Swiss Center of Expertise of Social Sciences in Switzerland. Her research focuses on education and migration. .

Notes

1 Frejka et al. (Citation2016) included the following CEE countries in their analysis: Belarus, Bulgaria, Czechia, Croatia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Russian Federation, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Ukraine.

2 Complete information on the survey, including questionnaires, is available from http://www.europeansocialsurvey.org.

3 Based on advice obtained via personal communication with the ESS team we deleted the missing cases instead of using imputation methods.

4 We did not want to involve migration rate and migration policy macro-level variables in the same models, since they are correlated.

References

- Albertini, M. and E. Brini. 2021. “I’ve Changed my Mind. The Intentions to Be Childless, Their Stability and Realisation.” European Societies 23(1):119–60. doi: 10.1080/14616696.2020.1764997.

- Bail, C. A. 2008. “The Configuration of Symbolic Boundaries against Immigrants in Europe.” American Sociological Review 73(1):37–59. doi: 10.1177/000312240807300103.

- Begall, K. and M. Mills. 2011. “The Impact of Subjective Work Control, Job Strain and Work–Family Conflict on Fertility Intentions: A European Comparison.” European Journal of Population 27(4):433–56. doi: 10.1007/s10680-011-9244-z.

- Bohman, A. 2011. “Articulated Antipathies: Political Influence on Anti-Immigrant Attitudes.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 52(6):457–77. doi: 10.1177/0020715211428182.

- Bohman, A. and M. Hjerm. 2014. “How the Religious Context Affects the Relationship between Religiosity and Attitudes towards Immigration.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37(6):937–57. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2012.748210.

- Cavaille, C. and J. Marshall. 2019. “Education and Anti-Immigration Attitudes: Evidence from Compulsory Schooling Reforms across Western Europe.” American Political Science Review 113(1):254–63. doi: 10.1017/S0003055418000588.

- Ceobanu, A. M., and T. Koropeckyj-Cox. 2013. “Should International Migration Be Encouraged to Offset Population Aging? A Cross-Country Analysis of Public Attitudes in Europe.” Population Research and Policy Review 32(2):261–84. doi: 10.1007/s11113-012-9260-7.

- Coleman, D. 2002. “Replacement Migration, or Why Everyone is Going to Have to Livein Korea: A Fable for Our Times from the United Nations.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 357(1420):583–98. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.1034.

- Coleman, D. 2006. “Immigration and Ethnic Change in Low-Fertility Countries: A Third Demographic Transition.” Population and Development Review 32(3):401–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2006.00131.x.

- Coleman, D. 2009. “Divergent Patterns in the Ethnic Transformation of Societies.” Population and Development Review 35(3):449–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2009.00293.x.

- Creighton, M. J. and A. A. Jamal. 2022. “An Overstated Welcome: Brexit and Intentionally Masked anti-Immigrant Sentiment in the UK.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48(5):1051–71. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2020.1791692.

- Czymara, C. S. 2020. “Propagated Preferences? Political Elite Discourses and Europeans’ Openness toward Muslim Immigrants.” International Migration Review 54(4):1212–37. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2022.2099851.

- Davidov, E. and B. Meuleman. 2012. “Explaining Attitudes towards Immigration Policies in European Countries: The Role of Human Values.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 38(5):757–75. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2012.667985.

- De Zordo, S., D. Marre, and M. Smietana. 2022. “Demographic Anxieties in the Age of ‘Fertility Decline’.” Medical Anthropology 41(6–7):591–9. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2022.2099851.

- Dražanová, L. 2022. “Sometimes It is the Little Things: A Meta-Analysis of Individual and Contextual Determinants of Attitudes toward Immigration (2009–2019).” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 87:85–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2022.01.008.

- Dustmann, C. and I. Preston. 2000. Racial and Economic Factors in Attitudes to Immigration. Discussion Paper No. 190. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.251991.

- Duvander, A. Z., T. Lappegård, and G. Andersson. 2010. “Family Policy and Fertility: Fathers’ and Mothers’ Use of Parental Leave and Continued Childbearing in Norway and Sweden.” Journal of European Social Policy 20(1):45–57. doi: 10.1177/0958928709352541.

- Frejka, T., S. Gietel-Basten, L. Abolina, L. Abuladze, S. Aksyonova, A. Akrap, and P. Zvidrins. 2016. “Fertility and Family Policies in Central and Eastern Europe after.” Comparative Population Studies 41(1):3–56. doi: 10.12765/CPoS-2016-03.

- Gallego, A. and S. Pardos-Prado. 2014. “The Big Five Personality Traits and Attitudes towards Immigrants.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40(1):79–99. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2013.826131.

- Gietel-Basten, S., A. Rotkirch, and T. Sobotka. 2022. “Changing the Perspective on Low Birth Rates: Why Simplistic Solutions Won’t Work.” BMJ 379:e072670. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-072670.

- Glas, S. 2023. “What Gender Values Do Muslims Resist? How Religiosity and Acculturation over Time Shape Muslims’ Public-Sphere Equality, Family Role Divisions, and Sexual Liberalization Values Differently.” Social Forces 101(3):1199–229. doi: 10.1093/sf/soac004.

- Gorodzeisky, A. and M. Semyonov. 2016. “Not Only Competitive Threat but Also Racial Prejudice: Sources of Anti-Immigrant Attitudes in European Societies.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 28(3):331–54. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edv024.

- Hainmueller, J. and M., J. Hiscox. 2007. “Educated Preferences: Explaining Attitudes toward Immigration in Europe.” International Organization 61(02):399–442. doi: 10.1017/S0020818307070142.

- Harrington, R. 2019. “Childfree by Choice.” Studies in Gender and Sexuality 20(1):22–35. doi: 10.1080/15240657.2019.1559515.

- Hašková, H. and R. Dudová. 2020. “Selective pronatalism in childcare and reproductive health policies in Czechoslovakia.” The History of the Family 25(4):627–648. doi:10.1080/1081602X.2020.1737561.

- Hašková, H. and R. Dudová. 2021. “Children of the State? The Role of Pronatalism in the Development of Czech Childcare and Reproductive Health Policies.” Pp. 181–98 in Intimacy and Mobility in an Era of Hardening Borders, edited by H. Haukanes and F. Pine. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Hayes, A. F. 2006. “A Primer on Multilevel Modeling.” Human Communication Research 32(4):385–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2006.00281.x.

- Heath, A., E. Davidov, R. Ford, E. G. Green, A. Ramos, and P. Schmidt. 2020. “Contested Terrain: Explaining Divergent Patterns of Public Opinion towards Immigration within Europe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46(3):475–88. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2019.1550145.

- Heath, A. F. and L. Richards. 2020. “Contested Boundaries: Consensus and Dissensus in European Attitudes to Immigration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (3):489–511. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2018.1550146.

- Hellwig, T. and A. Sinno. 2017. “Different Groups, Different Threats: Public Attitudes towards Immigrants.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43(3):339–58. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2016.1202749.

- Hjerm, M. 2007. “Do Numbers Really Count? Group Threat Theory Revisited.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 33(8):1253–75. doi: 10.1080/13691830701614056.

- Höhn, C. 1988. “Population Policies in Advanced Societies: Pronatalist and Migration Strategies.” European Journal of Population 3(3–4):459–81. doi: 10.1007/BF01796909.

- Hox, J. J., M. Moerbeek, and R. Van De Schoort. 2017. Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications. New York: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315650982.

- Koopmans, R., I. Michalowski, and S. Waibel. 2012. “Citizenship Rights for Immigrants: National Political Processes and Cross-National Convergence in Western Europe, 1980–2008.” AJS; American Journal of Sociology 117(4):1202–45. doi: 10.1086/662707.

- Koropeckyj-Cox, T. and G. Pendell. 2007. “The Gender Gap in Attitudes about Childlessness in the United States.” Journal of Marriage and Family 69(4):899–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00420.x.

- Kotzeva, T., and E. Dimitrova. 2014. “Nationalism and Declining Population in Bulgaria after.” Comparative Population Studies 39(4):1990. doi: 10.12765/CPoS-2014-15.

- Kreyenfeld, M. and D. Konietzka. 2017. “Analyzing Childlessness,” in Childlessness in Europe: Contexts, Causes, and Consequences, edited by M. Kreyenfeld and D. Konietzka. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-44667-7_1.

- Kunovich, R. M. 2004. “Social Structural Position and Prejudice: An Exploration of Cross-National Differences in Regression Slopes.” Social Science Research 33(1):20–44. doi: 10.1016/S0049-089X(03)00037-1.

- Lutz, W., G. Amran, A. Belanger, A. Conte, N. Gailey, D. Ghio, E. Grapsa, K. Jensen, and M. Stonawski. 2019. Demographic Scenarios for the EU: Migration, Population and Education. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. doi: 10.2760/590301.

- Lyck-Bowen, M., and M. Owen. 2019. “A Multi-Religious Response to the Migrant Crisis in Europe: A Preliminary Examination of Potential Benefits of Multi-Religious Cooperation on the Integration of Migrants.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45(1):21–41. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2018.1437344.

- Markaki, Y., and S. Longhi. 2013. “What Determines Attitudes to Immigration in European Countries? An Analysis at the Regional Level.” Migration Studies 1(3):311–37. doi: 10.1093/migration/mnt015.

- Marois, G., A. Bélanger, and W. Lutz. 2020. “Population Aging, Migration, and Productivity in Europe.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117(14):7690–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1918988117.

- May, J. F. 2015. “Population Policies in Europe.” L'Europe en Formation 377(3):136–50. doi: 10.3917/eufor.377.0136.

- Mccutcheon, J. M. 2020. “Reviewing Pronatalism: A Summary and Critical Analysis of Prior Research Examining Attitudes towards Women without Children.” Journal of Family Studies 26(4):489–510. doi: 10.1080/13229400.2018.1426033.

- Melegh, A. 2016. “Unequal Exchanges and the Radicalization of Demographic Nationalism in Hungary.” Intersections 2(4):87–108. doi: 10.17356/ieejsp.v2i4.287.

- Merz, E.-M. and A. C. Liefbroer. 2012. “The Attitude toward Voluntary Childlessness in Europe: Cultural and Institutional Explanations.” Journal of Marriage and Family 74(3):587–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00972.x.

- Meuleman, B., K. Abts, P. Schmidt, T. F. Pettigrew, and E. Davidov. 2020. “Economic Conditions, Group Relative Deprivation and Ethnic Threat Perceptions: A Cross-National Perspective.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46(3):593–611. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2018.1550157.

- Mitchell, J. 2021. “Social Trust and anti-Immigrant Attitudes in Europe: A Longitudinal Multi-Level Analysis.” Frontiers in Sociology 6:604884. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2021.604884.

- Morgan, S. P. 2003. “Is Low Fertility a Twenty-First-Century Demographic Crisis?” Demography 40(4):589–603. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0037.

- Muthuta, M. and P. Laoswatchaikul. 2022. “The Patterns of Family Policy to Enhance Fertility: The Comparative Analysis.” Social Space 22(1):286–304.

- OECD. 2021. Labour Market Transitions across OECD Countries: Stylised Facts. Working Papers No. 1692.

- O’Rourke, K. H. and R. Sinnott. 2006. “The Determinants of Individual Attitudes towards Immigration.” European Journal of Political Economy 22 (4):838–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2005.10.005.

- Pető, A., J. Goetz, S. Höft, and L. Oláh. 2022. Discourses on Demography in the EU Institutions. Brussels, Belgium: Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung.

- Pottie‐Sherman, Y. and R. Wilkes. 2017. “Does Size Really Matter? On the Relationship between Immigrant Group Size and anti‐Immigrant Prejudice.” International Migration Review 51(1):218–50. doi: 10.1111/imre.12191.

- Quillian, L. 1995. “Prejudice as a Response to Perceived Group Threat: Population Composition and Anti-Immigrant and Racial Prejudice in Europe.” American Sociological Review 60(4):586–611. doi: 10.2307/2096296.

- Rijken, A. J. and E.-M. Merz. 2014. “Double Standards: Differences in Norms on Voluntary Childlessness for Men and Women.” European Sociological Review 30(4):470–82. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcu051.

- Saczuk, K. 2013. “Development and Critique of the Concept of Replacement Migration,” in International Migration and the Future of Populations and Labour in Europe. Dodrecht: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-8948-9_13.

- Scheepers, P., M. Gijsberts, and M. Coenders. 2002. “Ethnic Exclusionism in European Countries. Public Opposition to Civil Rights for Legal Migrants as a Response to Perceived Ethnic Threat.” European Sociological Review 18(1):17–34. doi: 10.1093/esr/18.1.17.

- Semyonov, M., R. Raijman, and A. Gorodzeisky. 2006. “The Rise of anti-Foreigner Sentiment in European Societies, 1988-2000.” American Sociological Review 71(3):426–49. doi: 10.1177/000312240607100304.

- Semyonov, M., R. Raijman, A. Y. Tov, and P. Schmidt. 2004. “Population Size, Perceived Threat, and Exclusion: A Multiple-Indicators Analysis of Attitudes toward Foreigners in Germany.” Social Science Research 33(4):681–701. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2003.11.003.

- Sides, J. and J. Citrin. 2007. “European Opinion about Immigration: The Role of Identities, Interests and Information.” British Journal of Political Science 37((3):477–504. doi: 10.1017/S0007123407000257.

- Simonsen, K. B. 2017. “Does Citizenship Always Further Immigrants’ Feeling of Belonging to the Host Nation? A Study of Policies and Public Attitudes in 14 Western Democracies.” Comparative Migration Studies 5(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s40878-017-0050-6.

- Sobotka, T. 2004. “Is Lowest-Low Fertility in Europe Explained by the Postponement of Childbearing?” Population and Development Review 30(2):195–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2004.010_1.x.

- Sobotka, T., V. Skirbekk, and D. Philipov. 2011. “Economic Recession and Fertility in the Developed World.” Population and Development Review 37(2):267–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00411.x.

- Sobotka, T. and M. R. Testa. 2008. “Attitudes and Intentions toward Childlessness in Europe,” in People, Population Change and Policies. Dordrecht: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-6609-2_9.

- Stoop, I. A., J. Billiet, A. Koch, and R. Fitzgerald. 2010. Improving Survey Response: Lessons Learned from the European Social Survey. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Szalma, I., H. Hašková, L. Oláh, and J. Takács. 2022. “Fragile Pronatalism and Reproductive Futures in European Post‐Socialist Contexts.” Social Inclusion 10(3):82–6. doi: 10.17645/si.v10i3.6128.

- Thévenon, O. 2011. “Family Policies in OECD Countries: A Comparative Analysis.” Population and Development Review 37(1):57–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2011.00390.x.

- United Nations 2000. Replacement Migration: Is It a Solution to Declining and Ageing Populations?. New York: United Nations Publications.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. 2020. International Migration 2020 Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/452).

- Vachudova, M. A. 2020. “Ethnopopulism and Democratic Backsliding in Central Europe.” East European Politics 36(3):318–40. doi: 10.1080/21599165.2020.1787163.

- Wimmer, A. 2013. Ethnic Boundary Making: Institutions, Power, Networks. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Yuval-Davis, N. 1997. “Ethnicity, Gender Relations and Multiculturalism.” Pp. 193–207 in Debating Cultural Hybridity: Multicultural Identities and the Politics of anti-Racism, edited by P. Werbner and T. Modood. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Zeman, K., É. Beaujouan, Z. Brzozowska, and T. Sobotka. 2018. “Cohort Fertility Decline in Low Fertility Countries: Decomposition Using Parity Progression Ratios.” Demographic Research 38:651–90. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2018.38.25.

Appendix

Figure A1. Means and medians of attitudes toward voluntary childlessness by country.

Source: Own calculation based on ESS 2018.

Figure A2. Means of attitudes toward immigrations in two dimensions by country.

Source: Own calculation based on ESS 2018.

Table A1. Results of the OLS regression models: predicting attitudes toward migration in economic dimension.

Table A2. Results of the OLS regression models: predicting attitudes toward migration in cultural dimension.

Table A3. Results of the fixed effect multilevel regression models: predicting attitudes toward voluntary childlessness (Country is the panel variable so we can only run Model A).