Abstract

According to international law, the sovereignty of nation-states and the rights of individuals constitute two equally important principles. However, in instances when a state massively violates human rights, then priority is given to the protection of individuals over the self-determination of the state, thereby justifying humanitarian military intervention. This paper presents findings from a survey across 26 countries, analyzing citizen support for such intervention. We find that the majority of respondents supports military intervention to protect human rights. To explain the differences in support, we draw on world society theory and modernization theory. At first sight, world society theory offers a better framework for understanding citizens' attitudes towards military intervention. However, charcateristics derived from modernization theory are affected by a “suppression effect:” individuals living in more modernized countries and holding postmaterialist values endorse enforcing human rights but concurrently reject the use of military force.

1. Introduction

According to the world society theory, nation-states’ sovereignty and the prohibition of intervention in their internal affairs are among the sacred elements of an existing global culture (Meyer Citation2010; Meyer et al. Citation1997; Meyer and Jepperson Citation2000). The idea is codified above all in the Charter of the United Nations (UN). However, the idea of the sovereignty of states and their territorial integrity constitutes only one feature of a global culture. A second key element centers on individual rights, to which every person is entitled based on the fact that they are human (Elliott Citation2007; Meyer et al. Citation1997; Soysal Citation1994). These rights are universal, they apply regardless of the country in which an individual is living and are codified in the Declaration of Human Rights. The two principles – sovereignty of nation-states on the one hand and universal rights of individuals on the other – clash with each other when a state massively violates individual human rights within its territory. In this case, the norms enshrined in global culture and their implementation in international law prioritize protecting individuals over state self-determination, which legitimizes the international community to engage in military intervention as a means of safeguarding individuals.

Based on a novel public opinion survey that covers 26 countries from all regions of the world, this paper explores to what extent humanitarian military intervention is supported by or decoupled from citizen attitudes.Footnote1 Although we find that a majority of all respondents (54.7%) expresses support for the legitimacy of military intervention in instances of massive individual human rights violations, the results also indicate significant differences between and within countries. To better understand these differences, we derive our hypotheses from two broader theories: the notion of the existence of a global culture derived from world society theory on the one hand and modernization theory on the other. In line with world society theory, we expect that respondents living in countries more deeply embedded in the world society and individuals supporting the norms institutionalized by the global culture are more likely to endorse military humanitarian intervention. In terms of modernization theory, we hypothesize that the more modernized a country is, the more educated individuals are, and the more they have internalized postmaterialist values, the higher the likelihood that citizens support the idea that a military intervention is a legitimate policy to enforce the protection of individual human rights.

Upon initial examination of the results of the multivariate analyses, world society theory seems to offer a better framework for comprehending citizen attitudes toward military intervention compared to modernization theory. People with a strong commitment to the norms institutionalized in the global culture and – although to a lesser extent – people who live in countries deeply embedded into the world society tend to favor humanitarian military intervention more. In contrast, indicators associated with modernization theory – such as a country’s level of modernization as well as individuals’ postmaterialist values, and their level of education – do not significantly correlate with attitudes toward humanitarian military intervention. However, a closer analysis unveils an interesting nuance, especially for indicators related to modernization theory. Support for the enforcement of individual rights might be counterbalanced by a skepticism toward the use of military force. In particular, people holding postmaterialist values, and having a high level of education exhibit stronger support for the enforcement of individual human rights, while concurrently rejecting the use of military force as a means to achieve that goal.

With our study, we contribute to two distinct strands of literature, namely the world society theory and the body of political science research examining citizen attitudes toward military intervention. The relationship between the norms anchored in global culture and citizen attitudes represents a relatively under-researched area. World society research has traditionally focused on analyzing the relationship between global norms and their translation into national policies, making the exploration of the connection between global norms and citizen attitudes a noteworthy gap in the literature. This is rather surprising since public support is assumed to be crucial for the national adaptation of global norms (Finnemore and Sikkink Citation1998). Existing studies – albeit limited in number – have indicated that embeddedness into the world society indeed influences public attitudes.Footnote2 Our study expands this research by scrutinizing the relationship between global norms legitimizing humanitarian military intervention and citizen attitudes. At the same time, we go beyond these studies by bringing in modernization theory as an additional and alternative approach to understand citizen attitudes. In addition, our analysis encompasses a significantly broader range of countries, representing diverse regions across the globe, thereby enhancing the generalizability of our findings.

In contrast, political science research on attitudes toward military intervention is much more extensive and diverse. Some of the studies have analyzed people’s attitudes toward military intervention and the use of military force in foreign policy (Boussios and Cole Citation2012; Clements Citation2013; Coticchia Citation2015; Crowson Citation2009; Fetchenhauer and Bierhoff Citation2004), whereas others have concentrated on citizens’ more general perspectives on war and peace (Bizumic et al. Citation2013; Blumberg et al. Citation2017; Cavarra et al. Citation2021; Dupuis and Cohn Citation2011) or human rights (Crowson Citation2004; Swami et al. Citation2012). Findings on general support for humanitarian military intervention are somewhat inconclusive and vary between countries of inquiry.Footnote3 Our study diverges from the political science research on citizen attitudes toward humanitarian military intervention in two significant ways. Firstly, we apply a different theoretical framework by making use of two broader sociological theories, namely the notion of the existence of a global culture derived from world society theory on the one hand and modernization theory on the other. Linking attitudes toward humanitarian intervention to these two broad social science theories allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomena and how it is related to broader societal characteristics. Secondly, our contribution lies in the expansive scope of the data we analyze, which allows us to investigate broader global patterns in attitudes toward humanitarian intervention while concurrently considering both macro-factors related to the countries in which respondents live and micro-factors associated with features of individuals.

2. Global culture and international law on military intervention

World society theory assumes the existence of a global culture consisting of different ideas of how a society should be organized. Part of this global cultural model is the definition of legitimate actorhood. From the perspective of world society theory, actorhood is not naturally given but the result of a historical process of cultural construction (Meyer Citation2010; Meyer et al. Citation1997; Meyer and Jepperson Citation2000). The global culture attributes and grants two types of actors legitimate actorhood in particular: nation-states and individuals. Both types of actors are endowed with special rights that may clash with each other (Drewski and Gerhards Citation2020).

The notion that societies should be organized primarily as nation-states (and not, e.g., as empires, or based on ethnic, religious, or family ties) is illustrated by John W. Meyer et al. (Citation1997) with a fictitious example. If a hitherto unknown but inhabited island were discovered today, most people and institutions in the world would have a clear idea that the island society should be organized along the lines of a typical nation-state. Organizing the world society as an ensemble of sovereign states is an idea that has gradually become a reality since the middle of the nineteenth century (Wimmer Citation2012:2) and is nowadays institutionalized by international law. Most states have agreed to join international organizations such as the UN and to sign binding international treaties such as the Charter of the UN, which is the founding document of the UN. All nations agreed that the world order should be based on the principle of the sovereign equality of states. This idea includes the strict prohibition of forcible intervention in another state. In particular, Article 2(4) of the Charter of the UN states that: “All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations.” (United Nations Citation1945).

However, global culture grants a special role not only to nation-states but also to individuals (Bromley and Lerch Citation2018; Elliott Citation2007; Frank and McEneaney Citation1999; Koenig Citation2008; Meyer et al. Citation1997; Soysal Citation1994). It imagines the individual as an autonomous actor endowed with the volitional capacity to decide on their own life and destiny, and not as the property of any collectivity, as that of a state, or any other association. Global culture assumes that every individual has the right to individual self-determination by virtue of their nature as human beings. Similar to how territorial integrity and sovereignty of nation-states are protected by international law, the rights of individuals are protected by a variety of legal documents and above all the Universal Declaration of Human Rights from 1948. For the first time in human history, this declaration defined the rights and freedoms to which every human being is equally and inalienably entitled. Article 1 of the declaration reads accordingly: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” (United Nations Citation1948).

In cases where individual rights are severely violated in a country, the two principles – the sovereignty of nation-states and the protection of the individual – come into conflict with each other (Wotipka and Tsutsui Citation2008).Footnote4 The question that then arises is whether the international community is justified in resorting to military action against a country to protect the rights of its inhabitants, thereby infringing upon the country’s sovereignty. World society theory has not directly addressed this question. However, even though word society theory assumes that the global culture gives equal importance to the idea of sovereignty of states and the idea of protection of individual rights, it also assumes that a shift in priorities has taken place after WWII. Meyer argues that the experience of the two world wars and the Holocaust led to the restriction of the rights of the nation-state and the increasing expansion of the rights of individuals (Meyer Citation2010:6).

International law has developed in a very similar direction as it increasingly legitimizes military intervention by the international community to enforce the protection of individual human rights. Indeed, while the preservation of state sovereignty remains a cornerstone principle of international law, recent developments suggest a nuanced shift toward the recognition of military intervention as potentially justifiable under certain circumstances, particularly in cases of egregious human rights violations within a state’s borders (Glanville Citation2016). First, Chapter VII of the UN Charter allows the Security Council to take measures, including military measures, against states for the maintenance of peace (United Nations Citation1945). At first glance, the term “maintenance of peace” does not cover human rights violations. However, as Vaughan Lowe and Antonios Tzanakopoulos (Citation2014) have shown, Security Council practices have extended the interpretation of the notion “threat to the peace” to the point that it is now accepted that massive individual human rights violations within a state may constitute such a threat. There are many examples of UN-authorized military interventions that are characterized as humanitarian intervention by legal scholars even if the UN itself does not classify them as such (Lowe and Tzanakopoulos Citation2014). Second, at the 2005 World Summit, all member states of the UN agreed on the so-called “Responsibility to Protect” (R2P) doctrine (Gray Citation2018:58–64). The principle of the R2P is based on the assumption that the sovereignty of states includes the responsibility to protect their populations. However, if states fail to fulfill this duty, the international community is entitled to take action, if necessary, by force. The grounds for intervention cover massive individual human rights violations including ethnic cleansing, war crimes, genocide, and crimes against humanity. R2P is a reaction against the international community’s failure to respond to the Rwanda genocide in 1994 and the Srebrenica genocide in 1995. The Security Council resolution to impose a no-fly zone in Libya in 2011 was the first case where the UN authorized a military intervention citing the R2P.Footnote5 Third, there are military interventions that are not legitimized by the UN but where the intervening powers refer to the idea that an intervention is necessary to curb massive individual human rights violations. An example of this is the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO) intervention in Kosovo in 1999, after the Security Council failed to act on its Chapter VII due to the veto from Russia and China (Gray Citation2018:40–58).

Chapter VII of the UN Charter, RP2, and interventions that refer to the idea of protecting individual human rights, even if not approved by the UN, are highly controversial legally as well as politically (Bazirake and Bukuluki Citation2015). For example, the Independent International Commission on Kosovo (Citation2000:164) described the military intervention as illegal but legitimate. Notwithstanding, one can observe a discernible trend toward strengthening the normative framework supporting interventions in instances aimed at safeguarding individual human rights within a country’s borders over time (Glanville Citation2016).

3. Factors that might correlate with citizen attitudes toward military humanitarian intervention

In the following section, we attempt to theorize factors that may correlate with people’s attitudes regarding humanitarian intervention. We derive our hypotheses from two broader sociological theories: From the notion of the existence of a global culture on the one hand and the modernization theory on the other.Footnote6 The hypotheses derived from these two broader theories relate to characteristics of the countries in which respondents live (and by which they are influenced) and characteristics of the individuals themselves.

3.1. Embeddedness in the world society and committed to values of a global culture

World society theory assumes that the key normative ideas of a global culture and citizen values are linked. While they may be “de-coupled” at any given point in time, the theory asserts a long-term connection between these elements. One can assume that the dissemination and diffusion of the ideas of the global culture by international and national organizations into international law, national legislation, education, and political practices influence citizen attitudes (Meyer et al. Citation1997).Footnote7 According to the world society theory, integration into the global culture is primarily reflected in the membership of states in international institutions, the number of treaties between different states and above all the number of international non-governmental organizations (Beckfield Citation2010; Cole Citation2017). We assume that the more a country is embedded in the structure of the world society, the more citizens are exposed to the norms of the global culture and the more they show support for the protection of individuals (Kim Citation2020; Pandian Citation2019). Correspondingly, on the micro level, we expect a correlation between individuals’ general commitment to the norms of the global culture and support for the enforcement of individual human rights through military intervention.

3.2. Modernization and postmaterialist values

In contrast to world society theory, modernization theory assumes that people’s attitudes do not result from their inclusion in a world society and being exposed to the norms of a global culture but from the endogenous development of individual countries. Countries in our sample differ in their level of socio-economic modernization. As economic prosperity increases through modernization, a change in citizen values occurs. According to Ronald Inglehart and his collaborators (Inglehart Citation1971, Citation1997; Inglehart and Welzel Citation2005), a shift from materialist to postmaterialist values, or self-expression values, takes place when chances to satisfy material needs increase. Materialist values include the following: satisfying economic living conditions, security, national identity, and the exclusion of outsiders. Postmaterialist or self-expression values, in contrast, are characterized by the desire for self-fulfillment, an emphasis on freedom, participation, and the tolerance of diversity. We assume that caring for people living in another country whose lives are endangered is part of a postmaterialist value syndrome.

On the macro level, we expect that citizens from more modernized countries support humanitarian intervention more strongly than respondents from less modernized countries. On the individual level, we assume that people with postmaterialist values are those who support the protection of individuals against traditional authorities such as the state. In addition, we suspect that higher levels of education will result in cognitive mobilization, which is supposed to increase the likelihood that traditional concepts are questioned and possibly rejected, rather than being automatically accepted (Dalton Citation1984; Inglehart Citation1990). Questioning tradition can also refer to being critical of the sacred, untouchable sovereignty of the nation-state. We thus assume that people with higher educational attainment are more likely to have positive attitudes toward military humanitarian intervention.

However, modernization theory also suggests that postmaterialist values and high level of education (Inglehart Citation1990; Østby et al. Citation2019; Pinker Citation2012) correlate with pacifist attitudes and negative attitudes toward the use of force. Thus, when measuring attitudes toward humanitarian military intervention aiming to protect individual rights, positive attitudes toward the enforcement of individual human rights might clash with negative attitudes toward the mean of using military force, suppressing the former due to the latter. We suspect that this “suppression effect” is particularly influential for people holding postmaterialist values, having a high level of education, and living in countries with higher socio-economic modernization levels.

4. Data and methods

We use data from a novel survey, which surveyed 53,960 individuals in 26 countries around the world, including countries of the so-called Global North and the Global South, between December 2021 and July 2022 (Giebler et al. Citation2023b).Footnote8 The survey focuses on attitudes toward liberal values and peoples’ perspective on how a society should be organized. Countries have been systematically selected to cover as much heterogeneity as possible in terms of geographical spread (four world regions based on the UN Geoscheme), political regimes (based on Varieties of Democracy’s Electoral Democracy Index (Coppedge et al. Citation2021)), and socio-economic conditions (a combination of the Human Development Index and the Gini coefficient) (Giebler et al. Citation2023a:13). The target population in all 26 countries was permanent residents living in private households aged 18 or older in each country regardless of their nationality. In 19 countries, the data was collected via computer-assisted web-interviews (CAWI). Respondents were recruited from an online access panel administered by a collaborating survey company (Gallup International). The sample is stratified by gender, age, education, region of living, and place of locality in order to match the distribution of the respective country’s offline population. In those seven countries where online surveys were not feasible (especially due to too low Internet penetration), data was collected via personal interviews (CAPI) on the basis of a stratified probability sample via the random-walk procedure. To validate the questionnaire as best as possible, extensive pretests were conducted in the form of cognitive interviews and pilot studies prior to the main fieldwork (Giebler et al. Citation2023a:14). The survey was conducted in the most-spoken language(s) in each country.Footnote9

To ensure data quality, we use both ex-ante and post-hoc methods to exclude respondents with insufficient interview quality from the sample. We excluded respondents who failed an instructional manipulation check (“attention check”) as proposed by Daniel M. Oppenheimer et al. (Citation2009) and those who were identified as “speeders” based on the procedure proposed by Robert Greszki et al. (Citation2015:478). After these quality controls and the exclusion of respondents with missing values, we end up with 35,231 valid cases.

4.1. Dependent variables

This study focuses on the question of the extent to which citizens in different countries of the world support the idea that the international communityFootnote10 may invade another country militarily when individual human rights are violated.Footnote11 Respondents were asked the following question:

“Some people argue that under certain circumstances, the international community should have the right to intervene in other countries. Others argue that a country’s independence should always be respected. To what extent would you agree or disagree to each of the following statements?”

“What if human rights are massively violated in a country? The international community should have the right to intervene with military force.”

Agreement is measured on a six-point Likert-scale. In addition, respondents were given the options “I prefer not to say” and “Don’t know.” Given the broad spectrum of individual human rights, respondents might interpret the term differently.Footnote12 However, the question in our survey does not refer to human rights in general, but to cases where human rights are massively violated. Even if we cannot verify what the interviewees understand by massive human rights violations in the specific context, the literature suggests that media coverage plays a huge role in informing the public’s understanding of human rights (Mooney Citation2014). In turn, we suspect that respondents are guided by reports on real cases of military interventions that took place in the past (e.g., Somalia, Iraq, Kosovo) when they hear or read the wording of the question (“intervention with military force when human rights are massively violated”). In these past cases the debate was precisely about those violations that are defined by international law as massive violations of human rights (expulsions, ethnic cleansing, genocide).

For an additional analysis that tries to disentangle support for the international enforcement of the protection of individual human rights from opposition to the use of military force, we make use of an extra item, which asks respondents about their support for economic sanctions against a country that massively violates individual human rights. The wording of the item contains the same goal, namely the protection of human rights, but instead of military intervention, economic sanctions are mentioned as a means of achieving the goal (see Appendix B). Economic sanctions constitute an indirect (and thus minimal) form of intervention (Rattan Citation2019). Our assumption is thus that economic sanctions represent a much more moderate response by the international community to human rights violations. Combining responses to both items is a way of identifying those respondents whose support for humanitarian interventions is suppressed by an aversion to the use of military force, even though they support the international enforcement of human right through other means. For that, we restrict our sample to those respondents who are in favor of economic sanctions as a response to human rights violations (i.e., indicating a value of four or higher on our six-point scale). For this subsample we calculate the difference between approval of the tools of economic sanctions and military intervention by subtracting the item measuring the latter from the former. In our sample, the newly created variable ranges from -2 to 5. Positive values indicate stronger support for economic sanctions than for military intervention as a means for the protection of human rights.Footnote13 The higher the value, the greater the “suppression effect,” i.e., the more are attitudes toward humanitarian interventions attenuated by an aversion to the use of military force.

4.2. Independent variables

With regard to measuring the degree of a country’s institutional integration into the world, two different proposals can be found in the literature. “World polity” is a state-centric measurement, focusing on inter-state relationships, and intergovernmental organizations, whereas “world society” is a civil society measurement mainly looking at international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) (Boyle and Thompson Citation2001; Cole Citation2017; Wotipka and Tsutsui Citation2008). We measure countries’ institutional integration into the world through the second indicator. While treaties of states are sometimes only lip service, societal integration is closer to the citizens and accordingly can be expected to have an impact on citizens’ attitudes (Boyle and Thompson Citation2001; Cole Citation2017; Wotipka and Tsutsui Citation2008). We follow previous research by measuring world society linkages by the counts of a population’s membership in INGOs (Boli and Thomas Citation1999; Frank et al. Citation2000; Mejia Citation2020; Schofer and Hironaka Citation2005). A tie exists where at least one citizen claims membership, therefore capturing citizen-based world society linkages. We use data from the Yearbook of International Organizations (Union of International Associations Citation2018). Not restricting our measure to a specific domains allows us to measure a country’s level of integration in the world society more generally (Pandian Citation2019).

To measure individual commitment to the norms of a global culture, we use the item: “Should every human have the same basic rights in all countries or should a country’s society decide which rights people have in its country?” Respondents were asked to place themselves on a six-point Likert-scale with “1 – Every human should have the same basic rights in all countries” and “6 – A country’s society should decide which rights people have in its country” as endpoints. We reversed the scale that high values signify a commitment to the norms of a global culture.

To measure the level modernization of a country, we use the Human Development Index (HDI), provided annually by the UN (United Nations Development Programme Citation2021).

Postmaterialist attitudes are measured with the Inglehart index (1971). We compare “postmaterialists” to the two other categories. The two variables measuring postmaterialist values and commitment to the norms of a global culture are only weakly correlated with each other in our sample (.07), which means that they are valid indicators measuring two distinct concepts.

Education is measured based on the respondents’ highest educational attainment, differentiating between low, medium, and high education (see Supplementary Appendix 2).

4.3. Statistical models

We use multilevel linear regression models to estimate the effects on attitudes toward humanitarian military intervention to account for the nested data structure of respondents within countries and to adequately model within- and between-country differences (see Joop Hox et al. (Citation2017) for a detailed discussion of why and when one should use multilevel models).Footnote14 The models contain random intercepts at the country level, gender and age as control variables, and are estimated using maximum likelihood estimation.Footnote15 To compare the effect sizes between categorical and continuous variables, the latter are standardized through being divided by two standard deviations as proposed by Andrew Gelman (Citation2008). All models include post-stratification weights on the individual level and weights on the country level equaling the sample sizes. Since heteroscedasticity cannot be ruled out, we employ robust standard errors in all models.

5. Results and discussion

The results are presented in the following order. We start by describing country differences in the degree of support for humanitarian military intervention. In a second step, we analyze the influence of individual variables on support for military intervention. Third, we consider the influence of macro factors, and the interplay between contextual and individual characteristics. Finally, we analyze whether attitudes toward humanitarian military intervention are influenced by a potential suppression effect.

5.1. Country differences in support for humanitarian military intervention

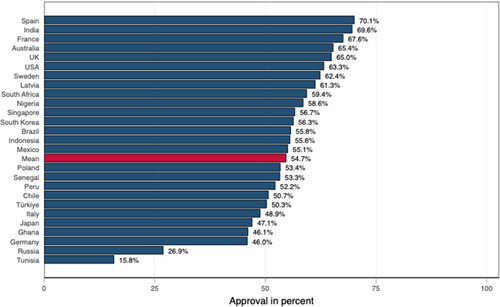

As shows, 54.7% of citizens in the 26 countries support the idea that the international community should have the right to intervene with military force in a country if human rights are massively violated.Footnote16 In 20 of 26 countries, more than half of citizens welcome military intervention to protect human rights indicating that in these countries, a majority of the population follows the prescription of the global culture. In four other countries, the support rate is only slightly below 50%.

Figure 1. Approval of military intervention in case of human rights violations.

Note: N= 35,231, post-stratification weights on the individual level as well as country weights adjusting the different sample sizes for the mean bar.

Although most citizens are in favor of military humanitarian intervention, also demonstrates that some countries deviate from that general pattern: Russia (27%) and Tunisia (16%) have by far the lowest approval rates. In the case of Russia, the low support could potentially be explained by the country’s self-understanding as an adversary to the perceived Western-dominated international community, resulting in skepticism of giving power to the international community to infringe on the sovereignty of nation-states. For Tunisia, we assume that the low support for humanitarian intervention might be a result of the country being directly exposed to the potential shortcomings of humanitarian interventions as a neighboring country of Libya, where the humanitarian intervention in 2011 led to a fundamental destabilization of the country. In four countries (Italy, Japan, Ghana, Germany) the support rate is just below 50%. Three of these countries are the Axis powers of WWII. We do not think that these countries are opposed to the international enforcement of human rights or to the international community in general. Rather, we believe a skepticism of military force predominates as a result of the countries’ historical experience of war, which cancels out the use of military force to protect human rights.

5.2. Individual-level factors

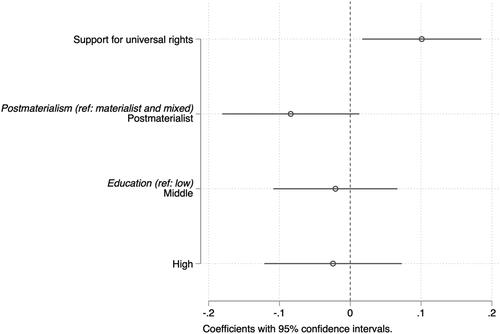

The hypotheses derived from world society theory and modernization theory expect that (a) respondents with a higher commitment to the norms of the global culture and (b) respondents with postmaterialist values and higher levels of education are more likely to support humanitarian military intervention. shows the result from a multilevel linear regression model with individual-level variables’ effects on support for humanitarian military intervention.Footnote17 The graph shows the coefficients for each independent variable with 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 2. Individual-level effects on support for humanitarian military intervention.

Note: N = 35,231, post-stratification weights on the individual level as well as country weights adjusting the different sample sizes. See Supplementary Appendix 3 for the regression table of the underlying model (Model 10).

shows that favoring humanitarian military intervention is associated with support for the universality of rights. Although the effect is relatively small, a stronger commitment to the world culture is linked to higher levels of support for humanitarian intervention.

The two indicators related to modernization theory – having postmaterialist values and high levels of education – do surprisingly not point in the theoretically expected direction and do not show any statistically significant effects. Hence, the expectations derived from modernization theory that higher educated individuals differ from lower-educated individuals and that postmaterialists differ from the rest of the population in their attitudes toward humanitarian intervention are not supported by the results of our analysis. Further below we discuss that this finding may be due to a suppression effect.

5.3. Country-level factors

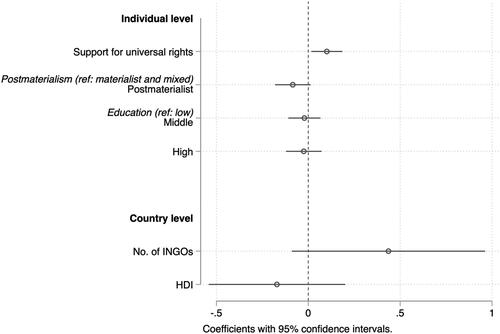

To what extent do country-specific characteristics impact the support for humanitarian military intervention? We estimate a multilevel model with the same specification used for but including both the HDI and number of INGOs on the country level. The results are presented in .Footnote18

Figure 3. Country-level effects on support for humanitarian military intervention.

Note: N = 35,231, post-stratification weights on the individual level, as well as country weights adjusting the different sample sizes. See Supplemnetary Appendix 4 for the regression table of the underlying model (Model 13).

As expected, the coefficients on the individual-level remain unchanged. Although the effect of a country’s embeddedness in the world society (measured by the number of INGOs) on support for humanitarian military intervention goes in the theoretically expected direction, it is not statistically significant. The influence of the level of modernization (measured by the HDI) is also not significant; surprisingly, it even goes in the opposite direction than theoretically expected. Finally, the intraclass correlation index (ICC = .07) indicates that there is not much variance that can be explained at the country level.Footnote19

5.4. The potential suppression effect

What could be the reasons for the fact that the indicators we have derived from modernization theory in particular have no influence on attitudes toward military intervention? We assume that responses to the item measuring support for humanitarian intervention are prone to a suppression effect, whereby people who are in favor of the protection of individual human rights do not support the use of military intervention as a means for achieving that goal. More specifically, we argue that higher levels of modernization (on the country level) and of education and postmaterialist values (on the individual level) increase support for the protection of individual human rights but are at the same time related to a commitment to pacifism and disapproval of the use of military force. Thus, the finding that the hypotheses derived from modernization theory are not confirmed could be the result of a suppression effect whereby support for the protection of individual human rights is counteracted by a disapproval of the use of military force.

To test this assumption, we created a new variable that measures for those respondents that generally support economic sanctions as the minimal tool for the enforcement of human rights, to which degree they prefer economic sanctions over military interventions. Higher values indicate stronger support for economic sanctions than for military intervention. In turn, the higher the value, the greater the “suppression effect,” i.e., the more are attitudes toward the enforcement of human rights attenuated by an aversion to the use of military force.

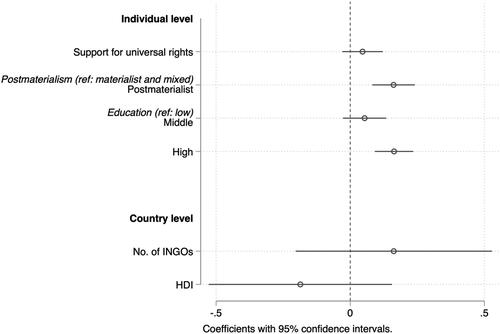

shows the results of a multilevel model with attitudes toward human rights enforcement adjusted for attitudes toward the use of military force as the new dependent variable. The results support our conjecture regarding a potential suppression effect: the individual-level indicators for modernization theory – postmaterialism and high education – show statistically significant positive effects. Individuals holding postmaterialist values and being highly educated tend to favor economic sanctions over military intervention as a means for protecting human rights, suggesting the existence of a suppression effect for this group of individuals, whereby attitudes toward the enforcement of human rights measured by the humanitarian intervention item were attenuated by an aversion to the use of military force. There is, however, no statistically significant effect for the macro variable related to modernization theory. Finally, the effects of the degree of integration of a country into the global society are likewise statistically insignificant: indicators measuring the commitment to the norms of a global culture: Support for universal rights and number of INGOs show positive albeit statistical insignificant effects.

Figure 4. Suppression effect – effects on attitudes toward human rights intervention adjusted for the effect of attitudes toward military intervention.

Note: N = 22,589, post-stratification weights on the individual level as well as country weights adjusting the different sample sizes. See Supplementary Appendix 5 for the regression table of the underlying model (Model 15).

6. Conclusion

According to international law, waging war against another country violates the principle of territorial sovereignty of all nation-states. There is one exception to this principle. If individual human rights are massively violated in a country, the international community has the right to intervene militarily. The legitimacy of this exception is grounded in the notion, constitutive to the global culture, that all humans have fundamental rights, regardless of the country in which they live. Based on a novel data set, a global comparative mass population survey covering 26 countries, we explored the extent to which citizens support the idea that the international community may invade another country militarily when individual human rights are massively violated, and which factors can help to make sense of differences in citizen attitudes. We investigate citizen attitudes as they are detrimental to the legitimacy of the norms of a global culture.

Results show that most of the respondents (54.7%), and majorities in most of the 26 countries support the notion that a military intervention in another country is legitimate when individual human rights are massively violated. The support rate is even higher (65%) if human rights are protected not by military intervention but by economic sanctions.Footnote20 Given recent developments, such as the contestations posed by right-wing populist actors and authoritarian regimes to a global culture emphasizing individual protection over national sovereignty (Walter Citation2021), alongside (reasonable) critiques of military interventions by Western countries in the name of human rights, the high level of support for the enforcement of human rights by the international community is somewhat surprising. We infer from these findings, that cultural prescriptions concerning the priority of the protection of human rights over the sovereignty of nation-states is seen as legitimate by most of the citizens around the world.

At the same time, we find substantial country differences in citizen attitudes toward military humanitarian intervention. Results from the multivariate analysis demonstrate that on the individual level, people’s general commitment to the norms of the global culture predicts support for military humanitarian intervention as postulated by world society theory. However, neither our expectation about the effect of a country’s embeddedness into the world society nor any expectations derived from modernization theory are supported by the results. What might be the reasons that our theoretical expectations in this regard have not been confirmed?

First, the fact that the degree of integration of a country into the global society has no significant effect could be due to the indicator used. The category 'number of international non-governmental organizations (INGOs)' covers very different types of organizations and is probably not specific enough for our research question. It would be better to have information on the number of INGOs that deal with human rights. Unfortunately, this information is not available. Second, to find out why the hypotheses derived from the modernization theory are not supported by our analysis, we conducted an additional analysis, examining whether the null findings are caused by what we call a “suppression effect.” We suspect that individuals who generally support the protection of human rights by the international community are reluctant to the use of military force to reach this goal. Making use of an additional item of the survey that measures support for economic sanctions as means for protecting human rights, we show that the among those who initially supported economic sanctions as a means to enforce human rights, the endorsement for humanitarian military intervention is comparatively lower: People holding post-material values and having a high educational degree are overrepresented in the group of those who are in favor of protecting human rights, but they are also those who tend to reject the use of military means. While generally supporting the protection of human rights by the international community they are less in favor of the use of military force to enact that goal.

Our study has a number of limitations, which we would like to address briefly. First, our data does not allow us to measure causal effects or analyze the specific mechanisms of the diffusion process from the global level down to the individuals (Kim Citation2020; Pandian Citation2019; Pierotti Citation2013). Second, the items are formulated in a rather general way. We do not know what kind of massive human rights violations respondents thought of, neither can we differentiate between different kinds of military and economic sanctions. Likewise, the items used did not mention the potential costs (e.g., financial costs, casualties) and risks that humanitarian military intervention might hold. The results might thus overestimate people’s support for humanitarian intervention compared to real-world scenarios. Third, although the descriptive analyses demonstrate that countries differ in their approval of military humanitarian intervention, we can only make sense of these differences to a smaller extent. Additional in-depth research, e.g., in form of qualitative studies that give justice to the historical developments and the specific characteristics of individual countries (as proposed, e.g., by Mahoney Citation2004), might enhance our understanding; especially since we are unable to determine to what extent the questions asked in the survey triggered different associations and consequently led to different responses. Especially the term “international community” might evoke different associations in different countries (Wallace Citation2019). Respondents living in former colonies might not necessarily refuse the idea of humanitarian military intervention altogether but might be skeptical of a military intervention being a Trojan horse of colonial or neocolonial powers to the detriment of the security of the sovereignty of states or people (Boniface Citation1997).

Despite these limitations, we believe some conclusions can be drawn from our results. First, the idea institutionalized in international law that the rights of individuals take precedent over the sovereignty of nation-states is supported by majorities in most of the countries in our sample. While political actors ignoring this principle may have short-term successes, as evident by the recent resurgence of nationalism, we argue that in the long-term, these actors will run into problems of legitimacy in light of populations committed to the international protection of human rights. Second, the results related to the suppression effect highlight, that individuals living in highly modernized, postmaterialist societies express a desire for the enforcement of universal values globally; however, there is a reluctance to commit to the use of military force which may be deemed necessary in certain instances to achieve these objectives. This poses a dilemma for policy makers, but also for INGOs that advocate military intervention to protect human rights. On the one hand, those in the population who speak out in favor of the protection of human rights constitute their constituency of support; on the other hand, however, it is precisely those people who are reluctant to use military force. In view of this situation, our study does not provide any concrete proposals for policymakers. Whether the experience of the current war in Ukraine changes this perspective toward a stronger belief in the necessity of a more robust defense of liberal values remains to be seen.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (74.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Heiko Giebler, Michael Zürn, and Tanja Börzel, who commented on a first version of the paper as well as to Ade Ajayi, Ana Karalashvili, Anna Kamenskikh, and Mikkel Wittrup Rasmussen for research assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Even though the decision on whether the international community or individual countries should intervene militarily in another country to protect human rights rests with governments rather than citizens, the opinions of the latter constitute a crucial parameter for political decision-makers. Timothy Hildebrandt et al. (Citation2013) show that public support for United States (US) humanitarian intervention plays a significant role in shaping US Congressional support. Similarly, the study by Michael Tomz et al. (Citation2020), relying on a vignette survey of Israeli members of parliament, illustrates that decision makers are more willing to support humanitarian military intervention when a majority of the population backs such an intervention. Incumbents frequently seek to secure public support (Kiratli Citation2023; Reiter and Stam Citation2002) given that voters’ backing may affect their legislative capacities (Gelpi and Grieco Citation2015), policy options (Perla Citation2011), electoral prospects (Kiratli Citation2022), and political survival (Berinsky Citation2009).

2 Elizabeth Heger Boyle et al. (Citation2002) used the case of female genital cutting to demonstrate how global norms influence citizen attitudes in five African countries. Rachael S. Pierotti (Citation2013) analyzed peoples’ attitudes toward intimate partner violence to demonstrate the impact of global norms. See also Roshan K. Pandian’s (Citation2019) study on world society integration and gender attitudes and Jessica Kim’s (Citation2020) analysis of the diffusion of international women’s rights norms.

3 Diverging from generally rather disapproving attitudes toward peacekeeping or regime change military missions, public support for humanitarian intervention varies across countries. For example, humanitarian interventions find support in the US (Eichenberg Citation2005; Jentleson and Britton Citation1998), but encounter less backing in Germany (Mader Citation2017). Furthermore, many studies have tried to identify conditions influencing support for humanitarian intervention. These studies suggest that the type of human rights violation (Agerberg and Kreft Citation2023), the specific moral arguments presented in favor of an intervention (Kreps and Maxey Citation2018), whether the intervention is conducted by single countries or the international community (Wallace Citation2019), and whether the victims of the human rights violations are perceived as in-group members (Grillo and Pupcenoks Citation2017) all contribute to shaping public opinion on this matter.

4 While state sovereignty is sometimes also framed as a human right (derived as a form of collective self-determination), this paper focusses on the individual dimension of human rights. We believe that this dimension is also reflected in the lay understanding of respondents. When speaking of “human rights,” we thus only refer to the individual dimension.

5 The R2P remains a controversial concept. In particular with reference to the NATO intervention in Libya, R2P was criticized for providing a pretext to oust Muammar al-Gaddafi.

6 For a very similar approach to understand attitudes towards elements of a global culture see Boyle et al. (Citation2002) and Jürgen Gerhards et al. (Citation2009).

7 Pierotti (Citation2013) has proposed a theoretical model that maps the diffusion process of ideas from global actors and NGOs through domestic actors of nation-states down to individuals. We are neither able to operationalize this diffusion process nor the complex interaction process between the global, national and local level (see e.g., Kern Citation2010). We can only roughly examine whether there is a correlation between the level of embeddedness of country into the world culture and people’s attitudes.

8 Elsewhere we have explained in detail the underlying methodology of the survey (Giebler et al. Citation2023a).

9 See Supplementary Appendix 1 for an overview of survey countries, sample sizes, modes, and questionnaire languages.

10 For a discussion of the implications and different understandings of the term “international community” also vis-à-vis the national configuration of intervening forces, see Geoffrey PR Wallace (Citation2019).

11 For all dependent, independent, and control variables see Supplementary Appendix 2 with a detailed overview on the wording of the variables used as well as distributions in our sample.

12 Unfortunately, research on people’s understandings of human rights is rather limited (exceptions being, e.g., McFarland and Mathews Citation2005; Spini and Doise Citation1998; Stenner Citation2011).

13 Concurrently, negative values indicate stronger support for military intervention than for economic sanctions and zero indicates equal support for both means.

14 Statistically, the null model (see Model 0 in Supplementary Appendix 3) yields an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of .069. About 7% of the variability in respondent attitudes towards interventions is due to differences at the country level, which justifies a multilevel approach. However, as the ICC is relatively small, we estimate a fixed effects model as a robustness check, which produces similar results (see Model 16 in Supplementary Appendix 6).

15 As restricted maximum likelihood estimation (REML) is sometimes recommended in the literature as preferable over maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) for analyses with only few cluster-level units (e.g., Elff et al. Citation2021; Stegmueller Citation2013), we conducted a robustness check using REML. However, as Stata does not allow the inclusion of weights for REML, we compare the REML model to an MLE without weights. The substantive results are identical between both models, indicating that even for the MLE model presented in Figure 2, an estimation with REML would not lead to substantially different results; see Model 17 and Model 18 in Supplementary Appendix 7.

16 We dichotomized the six-point scale measuring the level of support for humanitarian intervention; the upper half being approval, the lower half being disapproval.

17 See Model 10 in supplementary Appendix 3 for the regression table and Model 0–Model 9 for the previous iterations of the model-building sequence.

18 See the Supplementary Appendix 4 for the full regression table (Model 13), as well as the models including the two-country factors individually (Model 11 and Model 12).

19 Beyond embeddedness and modernization, additional country characteristics might affect attitudes toward military humanitarian intervention. Specifically, lower support for humanitarian interventions in the Global South might not be the result of lower levels of modernization or embeddedness into the world society, but due to experiences of colonialism. Past research has shown that respondents in countries having a colonial past tend to be particularly skeptical about foreign interventions and might interpret the notion of humanitarian interventions by the international community as an ideology of Western countries used to expand their sphere of influence (Borg Citation2016). To control for this, we conducted a robustness check by including a dummy variable (colonial past: yes or no) based on the Colonial Dates Dataset (COLDAT) (Becker Citation2019). We neither find a significant effect for colonial past nor does its inclusion change the effects of our main variables (see Supplementary Appendix 8). In addition, we checked to what extent a country’s experience with a humanitarian intervention in the past affects citizens’ attitudes. Of the 26 countries in our dataset, only the then territory of Indonesia saw a military humanitarian intervention during the East Timor conflict in 1999 (Gromes and Dembinski Citation2019). We do not find any significant effect when controlling for the experience of a humanitarian military intervention (see Supplementary Appendix 9).

20 The fact that support for military sanctions is lower than for economic sanctions is due to what we call the “suppression effect.” Postmaterialists, and people with a high level of education and those living in modernized countries are much more likely to support economic sanctions than the use of military force to protect individual rights.

References

- Agerberg, Mattias, and Anne-Kathrin Kreft. 2023. “Sexual Violence, Gendered Protection and Support for Intervention.” Journal of Peace Research 60(5):853–67. doi: 10.1177/00223433221092960.

- Bazirake, Joseph Besigye, and Paul Bukuluki. 2015. “A Critical Reflection on the Conceptual and Practical Limitations of the Responsibility to Protect.” International Journal of Human Rights 19(8):1017–28. doi: 10.1080/13642987.2015.1082844.

- Becker, Bastian. 2019. Colonial Dates Dataset (COLDAT). Cambridge: Harvard Dataverse.

- Beckfield, Jason. 2010. “The Social Structure of the World Polity.” American Journal of Sociology 115(4):1018–68. doi: 10.1086/649577.

- Berinsky, Adam J. 2009. Time of War: Understanding American Public Opinion from World War II to Iraq. 1st ed. Chicago, London: University of Chicago Press.

- Bizumic, Boris, Rune Stubager, Scott Mellon, Nicolas van der Linden, Ravi Iyer, and Benjamin M. Jones. 2013. “On the (In)Compatibility of Attitudes Toward Peace and War.” Political Psychology 34(5):673–93. doi: 10.1111/pops.12032.

- Blumberg, Herbert H., Ruth Zeligman, Liat Appel, and Shira Tibon-Czopp. 2017. “Personality Dimensions and Attitudes towards Peace and War.” Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research 9(1):13–23. doi: 10.1108/JACPR-05-2016-0231.

- Boli, John, and George M. Thomas. 1999. Constructing World Culture: International Nongovernmental Organizations Since 1875: International Nongovernmental Organisations Since 1875. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press.

- Boniface, Pascal. 1997. “The Changing Attitude towards Military Intervention.” International Spectator 32(2):53–63. doi: 10.1080/03932729708456776.

- Borg, Stefan. 2016. “The Arab Uprisings, the Liberal Civilizing Narrative and the Problem of Orientalism.” Middle East Critique 25(3):211–27. doi: 10.1080/19436149.2016.1163087.

- Boussios, Emanuel, and Stephen Cole. 2012. “An Analysis of Under What Conditions Americans Support the Use of Military Force Abroad in Terrorist and Humanitarian Situations.” Journal of Applied Security Research 7(4):417–38. doi: 10.1080/19361610.2012.710140.

- Boyle, Elizabeth Heger, Barbara J. McMorris, and Mayra Gómez. 2002. “Local Conformity to International Norms: The Case of Female Genital Cutting.” International Sociology 17(1):5–33. doi: 10.1177/0268580902017001001.

- Boyle, Elizabeth Heger, and Melissa Thompson. 2001. “National Politics and Resort to the European Commission on Human Rights.” Law & Society Review 35(2):321–44. doi: 10.2307/3185405.

- Bromley, Patricia, and Julia Lerch. 2018. Human Rights as Cultural Globalisation: The Rise of Human Rights in Textbooks, 1890–2013. Pp. 345–56 in The Palgrave Handbook of Textbook Studies, edited by Fuchs, Eckhardt and Bock, Annekatrin. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US.

- Cavarra, Mauro, Virginia Canegallo, Erika Santoddì, Erika Broccoli, and Rosa Angela Fabio. 2021. “Peace and Personality: The Relationship between the Five-Factor Model’s Personality Traits and the Peace Attitude Scale.” Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 27(3):508–11. doi: 10.1037/pac0000484.

- Clements, Ben. 2013. “Public Opinion and Military Intervention: Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya.” Political Quarterly 84(1):119–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-923X.2013.02427.x.

- Cole, Wade M. 2017. “World Polity or World Society? Delineating the Statist and Societal Dimensions of the Global Institutional System.” International Sociology 32(1):86–104. doi: 10.1177/0268580916675526.

- Coppedge, Michael, Gerring John, Knutsen Carl Henrik, Staffan I. Lindberg, Teorell Jan, Alizada Nazifa, Altman David, Bernhard Michael, Cornell Agnes, M. Steven Fish, et al. 2021. V-Dem Dataset V11.1. doi: 10.23696/vdemds21.

- Coticchia, Fabrizio. 2015. “Effective Strategic Narratives? Italian Public Opinion and Military Operations in Iraq, Libya, and Lebanon.” Italian Political Science Review/Rivista Italiana Di Scienza Politica 45(1):53–78. doi: 10.1017/ipo.2015.1.

- Crowson, H. Michael. 2004. “Human Rights Attitudes: Dimensionality and Psychological Correlates.” Ethics & Behavior 14(3):235–53. doi: 10.1207/s15327019eb1403_2.

- Crowson, H. Michael. 2009. “Right-Wing Authoritarianism and Social Dominance Orientation.” Social Psychology 40(2):93–103. doi: 10.1027/1864-9335.40.2.93.

- Dalton, Russell J. 1984. “Cognitive Mobilization and Partisan Dealignment in Advanced Industrial Democracies.” Journal of Politics 46(1):264–84. doi: 10.2307/2130444.

- Drewski, Daniel, and Jürgen Gerhards. 2020. The Liberal Border Script and Its Contestations: An Attempt of Definition and Systematization. SCRIPTS Working Paper Series, vol. 4. Berlin: Cluster of Excellence “Contestations of the Liberal Script” (SCRIPTS).

- Dupuis, Erin, and Ellen Cohn. 2011. “A New Scale to Measure War Attitudes: Construction and Predictors.” Journal of Psychological Arts & Sciences 1:6–15.

- Eichenberg, Richard C. 2005. “Victory Has Many Friends: U.S. Public Opinion and the Use of Military Forde, 1981-2005.” International Security 30(1):140–77. doi: 10.1162/0162288054894616.

- Elff, Martin, Jan Paul Heisig, Merlin Schaeffer, and Susumu Shikano. 2021. “Multilevel Analysis with Few Clusters: Improving Likelihood-Based Methods to Provide Unbiased Estimates and Accurate Inference.” British Journal of Political Science 51(1):412–26. doi: 10.1017/S0007123419000097.

- Elliott, Michael A. 2007. “Human Rights and the Triumph of the Individual in World Culture.” Cultural Sociology 1(3):343–63. doi: 10.1177/1749975507082052.

- Fetchenhauer, Detlef, and Hans-Werner Bierhoff. 2004. “Attitudes Toward a Military Enforcement of Human Rights.” Social Justice Research 17(1):75–92. doi: 10.1023/B:SORE.0000018093.23790.0d.

- Finnemore, Martha, and Kathryn Sikkink. 1998. “International Norm Dynamics and Political Change.” International Organization 52(4):887–917. doi: 10.1162/002081898550789.

- Frank, David John, Ann Hironaka, and Evan Schoter. 2000. “The Nation-State and the Natural Environment over the Twentieth Century.” American Sociological Review 65(1):96–116. doi: 10.2307/2657291.

- Frank, David John, and Elizabeth H. McEneaney. 1999. “The Individualization of Society and the Liberalization of State Policies on Same-Sex Sexual Relations, 1984-1995.” Social Forces 77(3):911–43. doi: 10.2307/3005966.

- Gelman, Andrew. 2008. “Scaling Regression Inputs by Dividing by Two Standard Deviations.” Statistics in Medicine 27(15):2865–73. doi: 10.1002/sim.3107.

- Gelpi, Christopher, and Joseph M. Grieco. 2015. “Competency Costs in Foreign Affairs: Presidential Performance in International Conflicts and Domestic Legislative Success, 1953–2001.” American Journal of Political Science 59(2):440–56. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12169.

- Gerhards, Jürgen, Mike S. Schäfer, and Sylvia Kämpfer. 2009. “Gender Equality in the European Union: The EU Script and Its Support by European Citizens.” Sociology 43(3):515–34. doi: 10.1177/0038038509103206.

- Giebler, H., L. Antoine, R. Ollroge, J. Gerhards, M. Zürn, J. Giesecke, and M. Humphreys. (2023a). Public Attitudes towards the Liberal Script (PALS) Survey: Dataset vol. 1. Berlin: Cluster of Excellence 2055 “Contestations of the Liberal Script (SCRIPTS)”. http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/refubium-41265.

- Giebler, H., L. Antoine, R. Ollroge, J. Gerhards, M. Zürn, J. Giesecke, and M. Humphreys. (2023b). Public Attitudes towards the Liberal Script (PALS) Survey. Conceptual Framework, Implementation, and Data. SCRIPTS Working Paper Series. Berlin: Cluster of Excellence 2055 “Contestations of the Liberal Script (SCRIPTS)”. https://www.scriptsberlin. eu/publications/working-paper-series/Working-Paper-33-2023/index.html.

- Glanville, Luke. 2016. “Does R2P Matter? Interpreting the Impact of a Norm.” Cooperation and Conflict 51(2):184–99. doi: 10.1177/0010836715612850.

- Gray, Christine D. 2018. International Law and the Use of Force. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Greszki, Robert, Meyer Marco, and Harald Schoen. 2015. “Exploring the Effects of Removing “Too Fast” Responses and Respondents from Web Surveys.” Public Opinion Quarterly 79(2):471–503. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfu058.

- Grillo, Michael C., and Juris Pupcenoks. 2017. “Let’s Intervene! But Only If They’re Like Us: The Effects of Group Dynamics and Emotion on the Willingness to Support Humanitarian Intervention.” International Interactions 43(2):349–74. doi: 10.1080/03050629.2016.1185420.

- Gromes, Thorsten, and Matthias Dembinski. 2019. “Practices and Outcomes of Humanitarian Military Interventions: A New Data Set.” International Interactions 45(6):1032–48. doi: 10.1080/03050629.2019.1638374.

- Hildebrandt, Timothy, Courtney Hillebrecht, Peter M. Holm, and Jon Pevehouse. 2013. “The Domestic Politics of Humanitarian Intervention: Public Opinion, Partisanship, and Ideology.” Foreign Policy Analysis 9(3):243–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-8594.2012.00189.x.

- Hox, Joop J., Moerbeek Mirjam, and Rens Van De Schoot. 2017. Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Independent International Commission on Kosovo. 2000. Kosovo Report: Conflict. International Response. Lessons Learned. Illustrated Edition. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, U.S.A.

- Inglehart, Ronald. 1971. “The Silent Revolution in Europe: Intergenerational Change in Post-Industrial Societies.” American Political Science Review 65(4):991–1017. doi: 10.2307/1953494.

- Inglehart, Ronald. 1990. Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

- Inglehart, Ronald. 1997. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

- Inglehart, Ronald, and Christian Welzel. 2005. Modernization, Cultural Change, and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence. Cambridge, UK ; New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Jentleson, Bruce W., and Rebecca L. Britton. 1998. “Still Pretty Prudent: Post-Cold War American Public Opinion on the Use of Military Force.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 42(4):395–417. doi: 10.1177/0022002798042004001.

- Kern, Thomas. 2010. “Translating Global Values into National Contexts: The Rise of Environmentalism in South Korea.” International Sociology 25(6):869–96. doi: 10.1177/0268580910378139.

- Kim, Jessica. 2020. “The Diffusion of International Women’s Rights Norms to Individual Attitudes. The Differential Roles of World Polity and World Society.” Sociology of Development 6(4):459–92. doi: 10.1525/sod.2020.6.4.459.

- Kiratli, Osman Sabri. 2022. “Together or Not? Dynamics of Public Attitudes on UN and NATO.” Political Studies 70(2):259–80. doi: 10.1177/0032321720956326.

- Kiratli, Osman Sabri. 2023. “Policy Objective of Military Intervention and Public Attitudes: A Conjoint Experiment from US and Turkey.” Political Behavior :1–23. doi: 10.1007/s11109-023-09871-0.

- Koenig, Matthias. 2008. “Institutional Change in the World Polity: International Human Rights and the Construction of Collective Identities.” International Sociology 23(1):95–114. doi: 10.1177/0268580907084387.

- Kreps, Sarah, and Sarah Maxey. 2018. “Mechanisms of Morality: Sources of Support for Humanitarian Intervention.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 62(8):1814–42. doi: 10.1177/0022002717704890.

- Lowe, Vaughan, and Antonios Tzanakopoulos. 2014. Humanitarian Intervention. In Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, edited by Wolfrum, Rüdiger. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mader, Matthias. 2017. “Citizens’ Perceptions of Policy Objectives and Support for Military Action: Looking for Prudence in Germany.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 61(6):1290–314. doi: 10.1177/0022002715603099.

- Mahoney, James. 2004. “Comparative-Historical Methodology.” Annual Review of Sociology 30(1):81–101. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.30.012703.110507.

- McFarland, Sam, and Melissa Mathews. 2005. “Who Cares about Human Rights?” Political Psychology 26(3):365–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2005.00422.x.

- Mejia, Steven Andrew. 2020. “Global Environmentalism and the World-System: A Cross-National Analysis of Air Pollution.” Sociological Perspectives 63(2):276–91. doi: 10.1177/0731121419857970.

- Meyer, John W. 2010. “World Society, Institutional Theories, and the Actor.” Annual Review of Sociology 36(1):1–20. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102506.

- Meyer, John W., John Boli, George M. Thomas, and Francisco O. Ramirez. 1997. “World Society and the Nation‐State.” American Journal of Sociology 103(1):144–81. doi: 10.1086/231174.

- Meyer, John W., and Ronald L. Jepperson. 2000. “The “Actors” of Modern Society: The Cultural Construction of Social Agency.” Sociological Theory 18(1):100–20. doi: 10.1111/0735-2751.00090.

- Mooney, Annabelle. 2014. Human Rights and the Body: Hidden in Plain Sight. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

- Oppenheimer, Daniel M., Meyvis Tom, and Nicolas Davidenko. 2009. “Instructional Manipulation Checks: Detecting Satisficing to Increase Statistical Power.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 45(4):867–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2009.03.009.

- Østby, Gudrun, Henrik Urdal, and Kendra Dupuy. 2019. “Does Education Lead to Pacification? A Systematic Review of Statistical Studies on Education and Political Violence.” Review of Educational Research 89(1):46–92. doi: 10.3102/0034654318800236.

- Pandian, Roshan K. 2019. “World Society Integration and Gender Attitudes in Cross-National Context.” Social Forces 97(3):1095–126. doi: 10.1093/sf/soy076.

- Perla, Héctor. 2011. “Explaining Public Support for the Use of Military Force: The Impact of Reference Point Framing and Prospective Decision Making.” International Organization 65(1):139–67. doi: 10.1017/S0020818310000330.

- Pierotti, Rachael S. 2013. “Increasing Rejection of Intimate Partner Violence: Evidence of Global Cultural Diffusion.” American Sociological Review 78(2):240–65. doi: 10.1177/0003122413480363.

- Pinker, Steven. 2012. The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined. Reprint Edition. New York, NY Toronto, Ontario London: Penguin Books.

- Rattan, Jyoti. 2019. “Changing Dimensions of Intervention Under International Law: A Critical Analysis.” SAGE Open 9(2):215824401984091. doi: 10.1177/2158244019840911.

- Reiter, Dan, and Allan C. Stam. 2002. Democracies at War. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

- Schofer, Evan, and Ann Hironaka. 2005. “The Effects of World Society on Environmental Protection Outcomes.” Social Forces 84(1):25–47. doi: 10.1353/sof.2005.0127.

- Soysal, Yasemin Nuhoğlu. 1994. Limits of Citizenship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Spini, Dario, and Willem Doise. 1998. “Organizing Principles of Involvement in Human Rights and Their Social Anchoring in Value Priorities.” European Journal of Social Psychology 28(4):603–22. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(199807/08)28:4<603::AID-EJSP884>3.0.CO;2-P.

- Stegmueller, Daniel. 2013. “How Many Countries for Multilevel Modeling? A Comparison of Frequentist and Bayesian Approaches.” American Journal of Political Science 57(3):748–61. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12001.

- Stenner, Paul. 2011. “Subjective Dimensions of Human Rights: What Do Ordinary People Understand by ‘Human Rights’?” International Journal of Human Rights 15(8):1215–33. doi: 10.1080/13642987.2010.511997.

- Swami, Viren, Ingo W. Nader, Jakob Pietschnig, Stefan Stieger, Ulrich S. Tran, and Martin Voracek. 2012. “Personality and Individual Difference Correlates of Attitudes toward Human Rights and Civil Liberties.” Personality and Individual Differences 53(4):443–7. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.04.015.

- Tomz, Michael, Jessica L. P. Weeks, and Keren Yarhi-Milo. 2020. “Public Opinion and Decisions About Military Force in Democracies.” International Organization 74(1):119–43. doi: 10.1017/S0020818319000341.

- Union of International Associations. 2018. Yearbook of International Organizations 2018-2019. Leiden: Brill Academic Pub.

- United Nations. 1945. United Nations Charter. https://www.un.org/en/about-us/un-charter.

- United Nations. 1948. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights.

- United Nations Development Programme. 2021. Human Development Index (HDI). https://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-index-hdi.

- Wallace, Geoffrey P. R. 2019. “Supplying Protection: The United Nations and Public Support for Humanitarian Intervention.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 36(3):248–69. doi: 10.1177/0738894217697458.

- Walter, Stefanie. 2021. “The Backlash Against Globalization.” Annual Review of Political Science 24(1):421–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-041719-102405.

- Wimmer, Andreas. 2012. Waves of War: Nationalism, State Formation, and Ethnic Exclusion in the Modern World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wotipka, Christine Min., and Kiyoteru Tsutsui. 2008. “Global Human Rights and State Sovereignty: State Ratification of International Human Rights Treaties, 1965-2001.” Sociological Forum 23(4):724–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1573-7861.2008.00092.x.