ABSTRACT

This paper addresses the preservation approach chosen for a selected group of born-digital artworks connected to the web, here categorized under the term internet art. The three first cases that are part of the project Infrastructuur Duurzame Toegankelijkheid Digitale Kunst (Collaborative Infrastructure for Sustainable Access to Digital Art) researched by LIMA (a platform for media art based in Amsterdam) focused on how to analyse internet artworks. This case study-based research was conducted in collaboration with 16 collecting institutions based in The Netherlands. The growing number of internet artworks in collections has pushed the development of preservation initiatives that consider these works’ fleeting nature, a consequence of their technical build and time-sensitive characteristics. The project aims to produce and share knowledge for these artworks’ preservation and overall sustainability while making it available for other similar works. This paper addresses the research steps while assessing its rationale and utility. It starts by describing the case study and assesses how the methodology serves conservation standards. The paper documents an overall evaluation of methods and results, pointing out the applicability and practical relevance of this initiative, here evaluated with positive conclusions. This paper fits the project’s mission concerning knowledge sharing and raising awareness for the preservation of internet artworks and is authored by a short-term PhD fellow at LIMA.

Introduction

Digital artworks promote fundamental changes in traditional museum practices. Their fragility lies in the fact that they result from binary codes that must be interpreted by machines assisting humans, through hardware and software. On the other hand, these (hardware and software) evolve rapidly and stop being able to read older digital information (Angevaare Citation2010; Falcão, Ashe, and Jones Citation2014). In this broader context, the growing presence of internet-based artworks in collections has raised both interest and necessity for their preservation (Falcão, Ashe, and Jones Citation2014; Arrigoni and McKim Citation2022; Roeck et al. Citation2019). The term ‘internet art’ is historically used to encompass diversified artworks created for or influenced by the internet. The internet’s technological infrastructure and respective problems have thus an impact on these works, namely on their changeable nature. This changeability can be used voluntarily by artists, but can also result from vulnerability to external dependencies, such as applications, databases, libraries, etc. Adding to these issues, preservation strategies must acknowledge the proprietary nature of many external dependencies and reduced knowledge of what constitutes best practice (Brum Citation2023). In addition, digital archiving policies are often insufficient for the work of art, as the latter is developed within a specific set of conventions typical of the visual arts, often explored by the artists. More so, museological organizations are often busy maintaining the classical collecting frameworks and have neither the skills, time, or resources to expand these areas of expertise within their institutions. Yet, more than the fact that this change is a direct or indirect consequence of the artwork’s nature, change is a non-negotiable condition to ensure the survival of these artworks, rendering classical punctual conservation actions insufficient. Thus, preservation skills and technical expertise are only a fraction of a complex ecosystem of which intellectual property, privacy and elusive ownership are an integral part (Arrigoni and McKim Citation2022). With the exponential growth of the digital world and the wingspan of such a laborious process, large-scale organizations and/or collaborations between organizations, such as the one discussed in this text, are vital. This chain of variables concerns institutions and individual collectors that often reflect what the artwork is and, ultimately, how to ensure its management.

In this context, the project Infrastructuur Duurzame Toegankelijkheid Digitale Kunst (Collaborative Infrastructure for Sustainable Access to Digital Art) (referred to as the ‘Infrastructure Project’, from this point on) by LIMA aims to bridge the gaps between artists and collections. The Netherlands has a solid cooperative structure for media art preservation, in which LIMAFootnote1 is one of its centres. LIMA, internationally acknowledged as a pioneer in media art preservation, whose success is rooted in the collaboration to produce and share knowledge between organizations, collections, and artists, impacts the field beyond borders. The Infrastructure Project follows this framework with two clear and urgent goals: to prevent the loss of digital artworks and to commonly develop the knowledge to preserve them sustainably, through research, training, knowledge sharing, and conservation (LIMA Citationn.d). Three internet artworks were selected as case studies to start the project: CS0001 – Compressed Forests, by Jan Robert Leegte; CS0002 – fillthisup. com by Rafaël Rozendaal; CS0003 – Running a Circle Clockwise by Jeroen Jongeleen. Their use of the web and its possibilities is diverse regarding production, distribution, display, and interactivity perspectives. Each case was chosen as representative of a more significant number of internet artworks and is used to determine methods for finding solutions to similar challenges and questions (LIMA Citationn.d). The research was conducted by LIMA’s preservation team comprised of Olivia Brum, Mauricio van der Maesen de Sombreff, hired and trained to develop this project, and Gaby Wijers, Wiel Seuskens, Kees Fopma, Joost Dofferhoff, and Claudia Röck.

Within these circumstances, besides assessing the strategy used to analyze the case studies, this article briefly outlines the vitality of institutional collaboration for the preservation of Internet artworks.

Preservation approach

The broader field of contemporary art conservation has strongly addressed variable artworks after the Modern Art: Who Cares?Footnote2 and Variable Media NetworkFootnote3 projects at the end of the twentieth century. Later, several international institutions started addressing specifically the preservation of software-based art. Matters in Media ArtFootnote4 started in 2005 as a coalition between several institutionsFootnote5 to help museums and non-institutional collectors, including care guidelines for software-based artworks. In the last decade, research projects have highlighted software-based art conservation, such as the ones at Rhizome,Footnote6 LIMA and SBMK,Footnote7 the Tate,Footnote8 the Guggenheim,Footnote9 and the V&A,Footnote10 publishing online resources from acquisition checklists to source code annotation examples. The focus on analysis and documentation was present in all the projects, as a roadmap to identifying the works’ vulnerabilities. Given the complexity of the subject matter, collaborations were often needed, including the ones with universities, and were mutually beneficial. Although often being developed from institutional initiatives, these projects were born out of practical concerns, and have ultimately made networking platforms essential, such as INCCA.Footnote11 Practically addressing these issues, a few countriesFootnote12 have been at the forefront of creating video labs, initially for distributing and managing video works, including The Netherlands with Montevideo (later NIMK)Footnote13 opening as early as 1978. Only later (1996) a media preservation lab was created at the Tate in London (Jones Citation2010; Wijers Citation2019; Lewis Citation2023). In this historical context, LIMA evolved from NIMK/Montevideo, having a relevant past dedicated to long-term access to media art alongside video and digital art creation in The Netherlands. This fact granted LIMA proximity with artists and institutional structures as a relevant middle ground. This position enabled LIMA to become technologically knowledgeable in the creation, management, and conservation of digital works; assist non-specialized institutions with their needs and enhance their baseline knowledge; and assist artists in creation, distribution, and preservation. Working with artists has been a strong point in LIMA’s mission, and resources were made available within this mindset – such as the Artwork Documentation Tool,Footnote14 an online database for artists, workshops addressed to artists, and media art documentation lectures in art academies (Wijers et al. and Phillips Citation2022).

The Infrastructure Project is a nationwide collaboration between LIMA and 16 institutions.Footnote15 These institutions do not collect many internet artworks and question – what exactly did we acquire? How do we care for these works’ preservation? Differently from what the projects mentioned above advise, LIMA was not present at the point of acquisition. However, the concerns addressing storage, accessibility, and long-term preservation are common and in line with the institutional concerns and expectations. Also, because this is an analytical strategy, and even though technologies and policies may change throughout, vital aspects are here determined and should be considered at all times, especially those directly obtained from the artists and creation-related stakeholders. Each of the works included was analyzed by LIMA based on both the input from artist interviews and the technical characteristics of the works. Generally similar to the mentioned resources and in line with the state of the artFootnote16 LIMA's workflow may sometimes differ due to its independent positionality – by not being the collecting institution, nor present on the acquisition, and due to its proximity with artists.

It is not the goal of this text to elaborate on the complex concept of authenticity in time-based media. However, it is relevant to point out that its understanding has been changing within the field of conservation, as a result of the reconceptualization of the artwork’s ontology, often prompted by the artistic creation itself (van de Vall Citation2023). Terms such as ‘work-defining properties’ (Laurenson Citation2006) and ‘critical mass’ (Gordon Citation2014) have been used to describe the artwork’s essential aspects, closely tied to the artist's intent and its connection with authenticity. In the case of digital-born artworks, the term ‘significant properties’ has been used often (Falcão, Ashe, and Jones Citation2014; Roeck, Rechert, and Noordegraaf Citation2018; Roeck et al. Citation2019) to represent a similar idea. For internet works, the original source code is one of the most crucial technical choices made at the moment of creation and affects the longevity of the artwork. It is part of the artwork’s style and aesthetics and often determines contextual information that can point us towards meaning (Dekker Citation2018). Therefore, detailing the work’s technical build and metadata is essential to reproduce the original technical environment, or migrate it without severe loss (Angevaare Citation2010). However, apart from these common elements, the fact that each artwork deals with specific artistic concerns makes it impossible to standardize procedures and necessarily shape LIMA’s approach. Thus, this project aimed to answer three broader questions – how was the work created conceptually and technically? How is it shown? How can we preserve it and present it in the future? – that then unfolded in specific inquiries for each of the case studies. These questions assist the evaluation of the artwork’s significant properties, namely addressing (LIMA Citation2023):

The behaviour of the work and user interaction;

source code analysis;

non-functional requirements (i.e. computing performance, quality of the output, video and/or sound rendering, stability of the software and security);

display specifications;

installation instructions.

LIMA’s workflow was applied consistently for the three cases, even though the research questions were specific. First, meetings with the collecting institutions clarified the expected outcomes for both parts, and an analysis of available documentation and artwork components followed. Within this research, additional documentation and literature sources were compiled in order to develop the research questions and the artist interview. The interview process is seminal, considering the relevance given to the artist’s intent and its correlation with the definition of the work’s significant properties and technical history. Additionally, LIMA considered the artist’s involvement as a ‘cross-pollination’: the junior conservatorsFootnote17 learn about the technology used, the artist’s motives, and conservation expectations via first-hand testimony, while the artists learn about conservation ethics and museological working methods (Wijers Citation2020).

Upon compiling the information and constituting the baseline for the artwork’s analysis, two steps followed: definition of the conservation strategy; and advising on immediate action and mid-term recommendations. The depth that this project required allowed for high levels of information in different categories. For this reason, two layers of content were produced:

Detailed condition report: includes artwork detailed description, exhibition history, source code, and performance analysis;

‘actions and recommendation’:

summary of compiled information with specific bullet points for display considering installation, and wherever action is needed;

layout of the essential steps for a correct conservation strategy, described in detail in layer no. 1 when needed.

The case study reports were written in English and are available via LIMA’s WikiFootnote18 for all the stakeholders involved but also for researchers upon request (Wijers Citation2020). The reports started by briefly describing the artwork and its concept and meaning, based on previously available documentation and the artist interviews, including direct quotations. The following section describes the artwork’s context in the artist’s practice and history, including production, provenance, exhibition registration, and artwork reception. The technical analysis was described, including functioning, interactivity (when applicable), dependencies, and source code. This chapter intertwined all the compiled information, allowing for the understanding of the artwork’s functionality and behaviour. This thorough analysis split into two moments – one that came from preliminary research on the available media and documentation; and another punctuated with information obtained from the artist on a second moment, the interview(s). The report expressed the relevance of the artist’s input in correlation with the technical analysis of the artwork’s structure while detailing the work’s significant properties.

As one of the project’s goals was to render the information accessible, case study reports and interviews were summarized. Within this context, further tools were developed to share publicly, namely: split screen video recording of the artist interacting with the work; two questionnaires aimed at facilitating the analysis of similar artworks; workshops – the first, presented as part of the Sustaining Art: People, Practice, Planet Contemporary Art Conservation symposium (9–11 November 2022) in Dundee, ScotlandFootnote19 titled, ‘Collaborative Care of Digital Art’; the second organized by LIMA for the institutions involved in the Infrastructure for Sustainable Digital Art project (2 December 2022); the third ‘Netart Analyzing workshop’ as part of Transformation Digital Art 2023Footnote20 at LIMA – , symposium presentations and publications (Brum Citation2023).

Case study

CS0001 Compressed Forests 2016

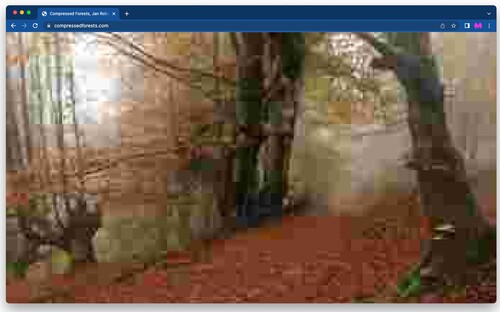

Compressed Forests consists of a website that features pixelated images of forests (). There is no text, capacity for user interaction, or sound, only cycles of images in 60-second intervals. These images are randomly harvested from Flickr,Footnote21 using the keywords ‘forest’ or ‘trees’, after which they are altered through a high degree of compression with the standard JPEG compression algorithm. Given the social network nature of Flickr, the displayed images are also geo-sensitive. The title Compressed Forests thus describes the process of compression that builds the low-quality, pixelated pictures that fill the screen when one visits the work (Brum Citation2023).

Figure 1. Screenshot of Compressed Forests, showing how it appears at compressedforests.com. Title: Compressed Forests; link to artwork: https://compressedforests.com; artist: Jan Robert Leegte; created: 2016; media: website (web browser-based), client-side (HTML, Javascript, Cascade Style Sheet), images from Flickr; owner of artwork: Rijksdienst Cultureel Erfgoed (RCE).

This work was chosen as an example of internet artworks with generativeness and the use of algorithms. These works often rely on external databases or user input, which a fixed algorithm then alters for a given final effect. Artworks with external dependencies have changeability as part of their significant properties, therefore this feature must be preserved. Thus, the research questions were formulated: ‘How to conserve computer-generated works that rely on the internet and an external database, such as Flickr? How can we store changing data, supplied by external dependencies, and keep it accessible? How can a work of art based on social media still be presented in a meaningful way fifteen years from now?’ (Brum Citation2023).

It was concluded that these external dependencies could break the work: Flickr database, JPEG file format; internet connection; web browsers must interpret Javascript, CSS, and HTML; the web browser needs to be able to execute the Javascript composition.js. These dependencies could change the work: incompatibility of the crisp-edges property with the web browser; and average resolution of Flickr images.

CS0002 fillthisup.com 2014

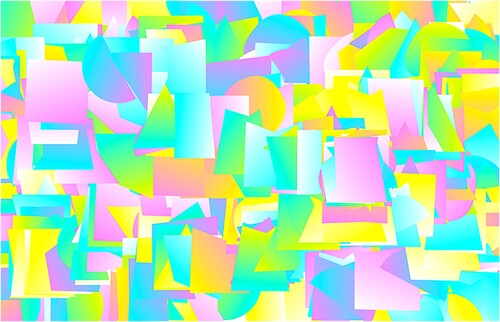

fillthisup.com is an interactive webpage without sound (). It can also be shown offline as an installation. When opening the web page it first appears white and blank, only beginning to fill with various shapes, in assorted brightly coloured gradients, when the cursor is moved into the browser window. When the mouse button is held down while moving, the shapes produced are white instead of coloured and leave a white trail behind the cursor, allowing it to act as an eraser. The scale of the shapes is proportional to the browser's window height. Unlike Compressed Forests which has algorithmic attributes, this work does not make use of an external database. Instead, artworks with similar attributes are composed of source code, files, videos, and so on, which are uploaded to and stored on the server. The addressed questions were: ‘What is acquired and transferred? How can the artwork be exhibited in the future? How to present an interactive net art piece in a way that encourages interaction? Particularly in a hotel space? How can the interaction and/or synchronization be mapped and the technology preserved? How can knowledge concerning how to maintain the work be transferred?’ (Brum Citationn.d.).

Figure 2. Screenshot of fillthisup.com, showing how it appears at www.fillthisup.com. Title: Fill This Up; link to artwork: http://www.fillthisup.com; artist: Rafaël Rozendaal; created: 2014; media: website (web-browser based), client-side/server-side; owner of artwork: KRC Collection.

This work was created during Rozendaal’s transition from Adobe Flash to JavaScript and HTML5, prompted by mobile devices, which did not support Adobe Flash nor provide a good user experience. The JavaScript version was online from the beginning with Rozendaal later making a nearly identical set of offline exhibition files for presentation (LIMA et al. Citation2022). The interactivity problem posed by touchscreensFootnote22 was also addressed by assigning a random place to start the animation when a finger is held down making it possible to move around the screen, like on the computer (LIMA et al. Citation2022).

The artist highlights the online nature of his work (Brum and Rozendaal Citation2020) and states his preference for showing the work on an LED wall or a projection, centred and covering the majority of the wall. With it, a minimalistic, white pedestal with a mouse should be set up in the middle of the room with hidden wires and cords, distant from the image so that the visitor sees the work without being distracted by the interaction.Footnote23 He also prefers it to be shown live without the browser window since the domain name is also the work’s titleFootnote24 (LIMA et al. Citation2022) and ‘ … as big as possible … ’ so that the visitor disappears into the work.

CS0003 Running a Circle Clockwise 2017

Running A Circle Clockwise shows a video of the artist running a circle clockwise (). The constituents of the artwork are four videos with audio in different file formats and lengths, intended to help with accessibility from various browsers and display devices. It can also be presented as an installation, either offline or online, via a projection or a screen with the browser window visible and must still be accessible online simultaneously.

Figure 3. Screenshot of Running A Circle Clockwise, showing how it appears at www.runningacircleclockwise.com. Title: Running a Circle Clockwise; artist: Jeroen Jongeleen; date: 2017; media: website (web browser-based), client-side (HTML5, Javascript, Cascade Style Sheet), videos (mp4 (3:28), webm (16:33:16), ogg (1:28), and m4v (00:39)); owner of artwork: Museum Boijmans van Beuningen.

Similarly to CS0002, this case is composed of source code, files, and videos uploaded to and stored on the server. The artworks’ performative and conceptual nature was documented in the report in dialogue with the researched history, and artist interview highlights. The research questions were: ‘What is acquired and transferred? How can the artwork be exhibited in the future? How can knowledge concerning how to maintain the work be transferred? How do the different videos relate to different browsers and devices?’ (Brum Citationn.d.)

Jongeleen sees the video as a registration that creates a situation where the work is available but it is what he calls the ‘drawing’ – the path created – that is the artwork (LIMA et al. Citation2022). Nevertheless, there's more to the website technically than the online video-playing feature. He worked with programmers to publish the video,Footnote25 have it played back immediately when you access the URL, and loop after a fade-in (LIMA et al. Citation2022). When he was creating the work, many browsers already prevented the autoplay of media, for which the programmer had to create a script to load the video in a container (LIMA et al. Citation2022).

When LIMA tested the website in 2022 on multiple devices, a black screen appeared due to the autoplay block, among other incorrect displays, including the circle appearing oval on an iPad. A few proposals to address the video autoplay by adapting the source code of the website were developed by LIMA.

Conservation

Typically every internet artwork needs its special environment with specific versions of application servers and supported programming languages. Criteria for the sustainability of preservation strategies for internet art were described by Roeck et al. (Citation2019) and were reflected in LIMA's practical approach. One of the conservation actions suggested for the case studies consists of their virtualization on LIMA’s ArtHost. This action copies the original processing system and artwork software to form an independent system running on different hardware. The original system can be saved as a file in a standard format, and be run in the virtualization platform (Falcão, Ashe, and Jones Citation2014). Placing artworks into a virtual machine (VM) has several benefits: the system administrator no longer needs to solve conflicts between the different requirements of multiple artworks; more susceptible artworks based on older programme versions are isolated from the rest of the system, and are easier to maintain, migrate to other servers, backup, and restore. Thus, it is more sustainable than multiple private servers and allows institutions to manage a large collection of Internet artworks with more ease. The VMs are accessible via a proxy server that recognizes which artwork the user requests, allowing visitors to view and interact with it. VMs are also susceptible to obsolescence, so this is considered a first step. VM within LIMA can be dynamic or static, depending on the nature of the work. Static VMs do not access the internet and are not expected to ‘change’ during their lifetime, while dynamic VMs can go online and contain changeable artworks. Furthermore, ArtHost takes care of the domain name subscription for the artworks and renews it regularly to avoid it being taken over by another company or user, and produces disk images of the virtual machines that are kept with the source codes and additional relevant media collected are archived in LIMA’s digital repository.Footnote26

fillthisup.com, Compressed Forests, and Running a Circle Clockwise were transferred to ArtHost. To preserve Compressed Forests ‘alive’ in its software environment, a static VM was chosen, as the backend does not change with time.Footnote27 Additionally, LIMA created its own Flickr-API-key and replaced the artist’s key to assure future access to Flickr. No website updates are necessary because the code is embedded within an emulation, and neither are snapshots neededFootnote28 because it does not change with user input. However, access to the Flickr database and download of the images must be verified. The offline version – created to solve the problem of the external Flickr dependency or absence of an internet connection – has a different source code that gives access to the local database. The download of additional images from Flickr as a simple measure for long-term preservation, was implemented by LIMAFootnote29 and is a strategy used by other institutions (Arrigoni and McKim Citation2022). The offline version, including the images, was installed in the same VM as the online version but is not publicly accessible. In the future, when new versions of web browsers become unable to interpret the websites correctly, a browser emulation could be set up (Roeck Citation2021).

fillthisup .com’s software environment is not specific, so the static VM was chosen because the setup does not have to be adjusted, and since the website code is embedded within an emulation, it does not have to be updated (regarding the back-end). Since the website is not permanently altered by user input, snapshots are not necessary. It is relevant to register the speed with which the website lays down new shapes and the user interaction, and this was documented with a previous (2016) screen recording where the artist discusses how the work should behave.Footnote30

In Running a Circle Clockwise, the software environment is also not specific. Thus, a static VM was suggested as the back-end does not change with time. The work used to be unsecured (HTTP), but current web browsers only allow HTTP access if the user explicitly agrees with it. For this, HTTP and HTTPS access is necessary. To address the video autoplay, a JavaScript was inserted in the index.html file with a comment that explains why and by whom this line of code was inserted. To enable autoplay with sound, a small sound icon on the upper left corner was placed. These changes were agreed on by the artist and the collecting institution, and documented.

On collaboration

Conservation thinking has recently been through an ‘ecological turn’, which focuses on the practicalities of the artworks’ environments as deriving from sociological and anthropological theories, and science and technology studies (Engel and Phillips Citation2023). This emphasizes collaborative processes that output a specific ecology, either based on industry or in a specific community. Even though this ‘turn’ is not exclusive to internet artworks, their complexity is connected to the amount of differently skilled stakeholders involved in their creation and survival. The layers in these ecologies are mirrored in this research. Firstly, from its inception, LIMA has highlighted artist participation and is even characterized by having engineers on its team who are also artists. This is certainly helpful in having other artists on board for the interviewing process and results in multilateral collaboration. Also, the focus on user experience as part of the artwork’s significant properties underlines an essential layer in any digital art preservation strategy (Arrigoni and McKim Citation2022). More pragmatically, LIMA’s maintenance of server-side dynamics withholds a laborious and time-consuming process that supports a task that is often impossible to keep within museums’ traditional structures (Roeck et al. Citation2019).

Compressed Forests is part of the collection of the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands (RCE) but is managed by the Centraal Museum Utrecht. This aspect speaks to how additional layers between ownership, exhibition, and preservation may enhance the artwork’s vulnerability if they result in unclear responsibilities that add up to the interdependent nature of the artwork. It is a clever action to involve a specialized institution such as LIMA to congregate all the stakeholders and pragmatically unite efforts, through research, planning, and executive action. Leegte’s case study is a successful collaboration example on all sides. The artist’s continued relationship with LIMA and his technological literacy certainly helped in facilitating a fertile discussion on the analysis and preservation strategy throughout, in close dialogue with the collecting and managing institutions.

In considering fillthisup.com, one must acknowledge the nature of the collection that owns it. The KRC collection’s vision includes presenting the works in CitizenM hotel locations, also owned by the collector Rattan Chadha. The challenges of displaying Rozendaal’s interactive websites in these spaces differ from those in art exhibition spaces. When showing the work in one of the hotels, both KRC’s curator and the artist found the presentation unsuccessful, for it did not generate interactivity and interest in hotel visitors. First of all, two different perspectives on institutional contexts on the artist’s side should be highlighted. On one hand, despite the intentional ever accessible and free display of his artworks, Rozendaal is reluctant to show fillthisup.com in the hotel spaces. If, from a first glance this could be understood as a paradox, with hotel rooms being semi-public areas as are museums, the interactive aspect is vital for the artist and easier to enact in the gallery context. Although the artist’s expectations do not match the collection's in this particular case, LIMA’s role was crucial throughout the discussion with the collection and the artist. Both the conversation and suggested alterations were documented and in line with the particular worries and priorities of the artist (Brum Citationn.d.). LIMA’s mediation was successful: the artist and the collection have agreed on meeting halfway in their expectations without compromising the work’s significant properties.

Jongeleen is the least technologically engaged artist under study and his use of the internet is directly linked to its public availability. This appealed to him after a situation with a friend whose work in the Boijmans’ collection was forbidden to be shown at a music festival, due to copyright. He stated, ‘It is important that this running video was online, that it was always accessible, so it could not be monopolized, ending up in a depot (…)’ (LIMA et al. Citation2022). This challenge to the hierarchical institutional system is one of the work’s significant properties. Unfortunately, before LIMA’s conservation proposal was approved, the institution had changed the code with a script that allowed the autoplay of the video without sound, not conveying the artwork’s correct display. Another unfortunate detail relates to the webpage being formerly titled ‘Collection Boijmans van Beuningen 2022’, obliterating the artwork’s title, author, and correct date, and reinforcing institutional ownership. If the outcomes for CS0001 and CS0002 were described above as successful accomplishments, these difficulties for CS0003 appeal to the prefix ‘co’ (in Latin ‘with’) in ‘collaboration’. Even though this project has an obvious technical and documental backbone, the problem that threatened the work was socio-political. At this point, it seemed that Jongeleen’s institutional critique had reached its fulfilment, despite all the knowledge produced out of a dedicated project that can rarely be undertaken by a museological institution alone. Fortunately, after further dialogue, LIMA’s proposed solutions were approved, by both the museum and the artist.

Conclusion

This paper intended to review the analysis approach applied by LIMA for three internet artworks collected by different institutions. For one, the traditional museum framework is profoundly challenged by these artworks, and this forced the shaping of preservation and access strategies. For this, time-based media conservators, engineers, and artists are defining players in obtaining all the information on the artwork’s creation, functioning, and necessary change, in line with its significant properties. Cooperating in understanding the complexity of internet art and its dependency on distributed technical infrastructures is foremost. Collecting policies should reflect these objects’ environments in creation and performance, display and access, and focus on the moment of acquisition as one of intensive capture of information (Engel and Phillips Citation2023; Engel et al. Citation2023). As a good practice example, Rozendaal has free resources on his websiteFootnote31 and has often been cited for his acquisition contracts and even followed by other artists. One may affirm that this type of agreement can convey in a mandatory manner aspects that define the work’s significant properties in the mind of the artist, and can even be scripted in collaboration with the owner, a point that could have strongly assisted the preservation efforts for Jongeleen’s case if done during acquisition. This does not mean, however, that all the conceptual and technological aspects would be clarified in this step, and reiterates that research, analysis, and documentation are essential, often to be provided by external institutions that are, like LIMA, research and practice-led in the specificities of media art. An aspect that contributed to the initiative’s success was the artists’ willingness to be open about their work and, particularly, disclosing the source codes, which is not always the case. One of the highlights of this project is how the social dimensions for both distributed authorship and collaborative work are crucial when defining preservation guidelines. This could also lead us to know how sustainable this collaborative network can be in building a robust preservation method and ensuring good practice. And not least, how this approach may shift in time through an ever-evolving process, hand in hand with the evolution of the work of art.

Following the remarks on collaboration above, the overview of how the process evolved and changed through time shows a relevant example of how museological and collecting ecologies behave. The impact that this kind of project has and how specific queries trigger further processes is inspiring for other institutions. Within this research, not only the artworks proved different in their nature, but also the collections. One of them has a classical museological structure (Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen), another holds the work's ownership but not the management (RCE), and another collects media art in parallel with a business in hotel management (KRC). This heterogeneity necessarily shapes collecting and exhibition policies, and highlights the role of the independent institution (here played by LIMA) with the resources needed to address specific concerns and output deliverables accordingly. As referred to above, having a strategic placement between artists and collecting institutions is an advantage that allows successful mediation and comprehensive dialogues. Nevertheless, one must also note that decision-making is usually on the side of the collecting institution and that this can be occasionally challenging and an obstacle to acting both fast – immediate action can be crucial when dealing with technological obsolescence – and with alignment.

Like LIMA, private or public initiatives and universities can occupy this pivotal position. Additional events that inform diversified publics, such as workshops and conferences prove to be extremely useful in disseminating and raising awareness on the researched topics.Footnote32 Other institutions, independent of their sizes and amount of resources could find information and inspiration in the Infrastructure Project. Encouraging cross-institutional cooperation is directly linked with this particular historical moment and fast-paced technological innovation, and is here seen as vital for any digital preservation strategy. LIMA’s mission successfully highlights the connection between collecting institutions, creators, and preservation institutions. Specifically for this initiative, different degrees of institutional openness were observed, both regarding their approach to collecting and preserving, and how this project impacted them and vice-versa. In this context, collecting internet art also reinvigorates the debates on authority and representativity in institutional knowledge and the overall cultural heritage field.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 LIMA is a platform for media art based in Amsterdam. All its activities aim at a critical understanding of media art and technology and sustainable access to media art. Internationally, LIMA is a pioneer and centre of expertise in the fields of preservation, research, and distribution of media art. https://www.li-ma.nl/lima/about.

5 New Art Trust and its partner museums – the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), and Tate.

12 Electronic Arts Intermix, 1971, New York; Video Hiroba, 1972, Tokyo; London Video Arts, 1976, London; Montevideo, 1978, Amsterdam, are some examples. (Jones Citation2010).

13 Netherlands Media Art Institute – https://nimk.openbeelden.nl/.

15 Van Abbemuseum; De Appel, Bonnefanten, BPD art collection, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen (Boijmans), Centraal Museum, Frans Hals Museum, Groninger Museum, KRC collection, Kröller-Müller Museum, RCE collections department, RABO art collection, Rijksakademie, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, NDE and SBMK.

16 For more on this, check the recently published Engel and Phillips (Citation2023).

17 Training of fellows and hiring junior conservators has also been a strategy used by the Guggenheim with their CCBA Fellowship (https://www.guggenheim.org/conservation/the-conserving-computer-based-art-initiative).

18 https://www.mediawiki.org/wiki/MediaWiki. SFMoma (USA) and ZKM (Germany) are other examples of institutions using Mediawiki to manage their time-based media art collections.

21 https://www.flickr.com/ – image hosting service popular with professional and amateur photographers.

22 The mouse has a hover state and is actively relaying information about its location even when it is standing still, unlike the touchscreen (Brum Citationn.d.).

23 Similarly to the exhibition at Steve Turner Contemporary – “Almost Nothing Hardly Anything” (1–29 November 2014). “ (…) if you have a touch screen in a museum nobody touches it because you are not supposed to touch the art, but a trackpad is very clear” (Brum and Rozendaal Citation2020).

24 In 2018 at the Towada Art Center in Japan, Rozendaal included browser windows. However, he points out: “I find that the browser window does not age very well, when you see an old one it dates it so much (…) if you don’t show the browser window you are (…) giving it more of a fair chance not just looking at it as a piece of old software” (idem).

25 In the artist's opinion other video hosting platforms were not an option because you give away intellectual property rights and a main part of the work's meaning revolves around accessibility and autonomy. (LIMA et al. Citation2022).

26 LIMA’s digital repository follows standard guidelines upheld by the National Digital Stewardship Alliance and is based on LTOs.

27 It is static on the server side and dynamic on the client side (e-mail correspondence with Mauricio van der Maesen de Sombreff, April 2023)

28 Snapshots are a digital preservation tool that creates an archive of a live page and allows the monitoring of changes in websites (Roeck et al. Citation2019).

29 Around 660 images were downloaded in May 2022 using the same download method as the artist. Further downloads were done in August and November 2022 and March 2023. (Conversation with LIMA’s Preservation Team, June 2023).

30 Rafaël Rozendaal, Websites 2001 - 2016 (Produced by LIMA) – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GjR1lsem6tw.

32 For example, the annual symposium Transformation Digital Art hosted by LIMA, where artists, conservators, academics, engineers, etc. constitute a diversified audience – https://www.li-ma.nl/lima/news/transformation-digital-art-2024.

References

- Angevaare, I. 2010. “A Future for Our Digital Memory: Born-Digital Cultural Heritage in the Netherlands.” Art Libraries Journal 35 (3): 17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0307472200016497

- Arrigoni, G., and J. McKim. 2022. “Experimentation and Collecting Practice: Balancing Flexible Policies and Accountability in Developing Born-Digital Museum Collections.” Museum Management and Curatorship. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2022.2133782.

- Brum, O. 2023. “CS0001 - Case Study Report Summary.” LIMA. https://wiki.li-ma.nl/index.php/CS0001:Case_Study_Summary. Available on Request.

- Brum, O. n.d. “Case Study Report Summary.” https://wiki.li-ma.nl/index.php/CS0002:Case_Study_Summary. Available on request.

- Brum, O. n.d. “Case Study Report Summary.” https://wiki.li-ma.nl/index.php/CS0003:Case_Study_Summary.

- Brum, O., and R. Rozendaal. 2020. “Rafaël Rozendaal.” Unpublished artist interview.

- Dekker, A. 2018. Collecting and Conserving Net Art: Moving beyond Conventional Methods. London: Routledge.

- Engel, D., and J. Phillips, eds. 2023. Conservation of Time-Based Media Art. London: Routledge.

- Engel, D., et al. 2023. “Caring for Software and Computer Based Art.” In Conservation of Time-Based Media Art, edited by D. Engel and J. Phillips, 453–511. London: Routledge.

- Falcão, P., A. Ashe, and B. Jones. 2014. “Virtualisation as a Tool for the Conservation of Software-Based Artworks.” International Conference on Digital Preservation.

- Gordon, R. 2014. “Identifying and Pursuing Authenticity in Contemporary Art.” In Authenticity and Replication: The 'Real Thing' in Art and Conservation, edited by R. Gordon, E. Hermens, and F. Lennard, 95–107. London, UK: Archetype Publications.

- Guggenheim. “The Conserving Computer Based Art Initiative.” Accessed June 15, 2023. https://www.guggenheim.org/conservation/the-conserving-computer-based-art-initiative.

- Jones, Caitlin. 2010. “Do It Yourself: Distributing Responsibility for Media Arts Preservation and Documentation.” In Archive 2020, edited by A. Dekker, 50–59, Amsterdam: Virtueel Platform.

- Laurenson, P. 2006. “Authenticity, Change and Loss in the Conservation of Time-Based Media Installations.” Tate Papers, no. 6. www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/06/authenticity-change-and-loss-conservation-of-time-based-media-installations.

- Lewis, K. 2023. “Building a Time-based Media Conservation Lab: A Survey and Practical Guide, from Minimum Requirements to Dream.” In Conservation of Time-Based Media Art, edited by D. Engel and J. Phillips, 95–110. London: Routledge.

- LIMA. 2023. “Case study reports.” Accessed May 19, 2023. https://wiki.li-ma.nl/. Available on request.

- LIMA. n.d. “Collaborative Infrastructure.” Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.li-ma.nl/lima/article/collaborative-infrastructure-sustainable-access-digital-art.

- LIMA, J. Jongeleen, S. Kensche, S. Swart, G. Wijers, and O. Brum. 2022. “20221128_deel Van Interview Met Jeroen Jongeleen_1:22:37_SK.m4a.” Artist Interview. in Artist Interview - Recordings. Available on request.

- LIMA, R. Rozendaal, F. Haverkamp, G. Wijers, and W. Seuskens. 2022. “video1724839523.” Artist Interview. in Artist Interview - Recording, available on request.

- LIMA, R. Rozendaal, W. Seuskens, and O. Brum. 2022. “video2619952182.” Artist interview. in Artist Interview - Recording, available on request.

- Roeck, C. 2021. Web Browser Characterisation, Emulation, and Preservation, 1–68. Dutch Digital Heritage Network.

- Roeck, C., R. Gieschke, K. Rechert, and J. Noordegraaf. 2019. “Preservation Strategies for an Internet-based Artwork Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow.” In IPRES 2019: 16th International Conference of Digital Preservation: proceedings: Amsterdam 16–20 September 2019, edited by M. Ras, B. Sierman, and A. Puggioni, 179–190. Dutch Digital Heritage Network. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/GF2U9

- Roeck, C., K. Rechert, and J. Noordegraaf. 2018. “Evaluation of Preservation Strategies for an Interactive, Software-Based Artwork with Complex Behavior Using the Case Study Horizons (2008) by Geert Mul.” In iPRES 2018 - Proceedings of the 15th Conference on Preservation of Digital Objects [207.4] Phaidra, Universität Wien. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/2VPFT.

- van de Vall, R. 2023. “Theories of Time-Based Media Art Conservation: From Ontologies to Ecologies.” In Conservation of Time-Based Media Art, edited by D. Engel and J. Phillips, 13–27. London: Routledge.

- Wijers, G. 2019. “Taking Care of Media Art in the Netherlands: A Brief History.” In A Critical History of Media Art in The Netherlands, edited by Sanneke Huisman and Marga van Mechelen, part II.3. Amsterdam: Jap Sam Books.

- Wijers, G. 2020. Infrastructuur Duurzame Toegankelijkheid Digitale Kunst - Projectvoorstel. Amsterdam: LIMA.

- Wijers, G., J. Phillips, et al. 2022. “A Roundtable: Collaborating with Media Artists to Preserve their Art.” In Conservation of Time-Based Media Art, edited by D. Engel and J. Phillips, 249–266. London: Routledge.