Abstract

How learners understand, respond to, and value educational feedback has been researched with self-report inventories, in which respondents provide insights into how they understand and claim to use feedback. The validity of learner self-reports depends on the credibility of the measures for both reliability and validity. A systematic search of Scopus for studies post-1999 found 42 studies using multiple indicators, multiple causes (MIMIC) psychometric methods to measure participants’ perceptions of feedback, giving evidence of internal structure and finding relationships with one or more of self-regulation, self-efficacy, or achievement emotions. A detailed analysis was conducted for ten inventories that had high-quality psychometric properties. Agreeing that feedback was useful and/or was used was positively associated with greater academic outcomes. However, only one inventory provided evidence related to independently measured behaviors. Important directions for further research are identified, including the use of strong psychometric methods, independent validation measures, replication samples, and behavioral measures.

Most of what is known about the effectiveness of feedback depends on student self-reports, rather than independent behaviors or outcomes. Indeed, the influence of feedback on student perceptions, behaviors, or outcomes requires consideration of what learners say for themselves. However, self-reports are subject to well-understood limitations (e.g., memory failings, lack of self-knowledge, or the need to protect the “self”). These concerns are especially important when conclusions regarding how students understand and perceive feedback are based on small-scale studies (e.g., interviews or focus groups). To illustrate the prevalence of these studies, we note that a recent review of research on student feedback literacy (Nieminen & Carless, Citation2022) identified 33 studies, of which 29 used qualitative methods and only two used structured response scales. Further, few survey studies of student perceptions of feedback follow “‘industry’ standards in how to design, validate, adapt, and use questionnaires to answer a variety of important research questions” (Van der Kleij & Lipnevich, Citation2021, p. 358). Hence, an important challenge in researching student perceptions of feedback stems from the common use of samples and methods outside the norms of psychometric research.

The challenges in using self-report instruments in research are also pertinent to how student perceptions of feedback are used within higher education institutions. On the National Student Survey in the UK, poor scores for how students perceive feedback can lead to negative evaluations of institutional quality by external agencies (Leckey & Neill, Citation2001) or cause institutions to impose new regulations around how quickly assignments need to be marked (Williams & Kane, Citation2008). To address concerns about subjectivity, many higher education institutions use student evaluation of teaching questionnaires (Richardson, Citation2005) that include items about feedback, thus, producing feedback about feedback. However, student responses on such inventories may arise from false ideas about practices that support learning; in other words, instructor fluency, engagement, and enthusiasm can inflate students’ sense of learning and satisfaction but may not necessarily cause learning to take place (Carpenter et al., Citation2020). Hence, making decisions based on students’ illusion of learning can lead to unfair evaluations of teaching quality (Esarey & Valdes, Citation2020). Additionally, students who prioritize satisfaction in learning may avoid and resent painful growth-causing messages found in negative teacher comments or grades (Boekaerts & Corno, Citation2005). Consequently, reliance on student perceptions about feedback to make administrative decisions requires robust psychometric research to overcome the subjectivity of small samples, poorly developed instruments, or lack of validation evidence independent of self-reports.

Hence, the purpose of this paper is to search for evidence that the challenges in using participant perceptions of feedback can be overcome. Inventories that measure student perceptions of feedback through self-report inventories are systematically reviewed. By evaluating the articles in light of psychometric principles, an understanding is sought of what can be concluded with confidence about student perceptions of feedback and their relationship with behaviors and actions. Of the hundreds of studies identified, just a few are of the highest quality and fewer connect self-report data to behavioral outcomes. This means that, despite the potential of self-report measures in understanding how students experience and use feedback, there are significant developments still to be made for this potential to be realized.

In this paper, a brief review of student perceptions of feedback within self-regulation of learning approach (Zimmerman, Citation2002) is given. Then the psychometric principles used to evaluate evidence about student feedback perceptions inventories are highlighted. A systematic review of student feedback perceptions research identified just 10 studies that met psychometric quality criteria from a pool of 251 papers. This review provides an overview of how feedback perceptions have been measured and their relationships, if any, to other factors (e.g., academic outcomes or behaviors). Finally, we consider more broadly the gaps in what is known and argue that well-constructed, theoretically-motivated psychometric measures can, in principle, make invaluable contributions to filling these gaps.

Feedback

Feedback is an important educational process that provides information to learners about the quality and characteristics of learning (Hattie & Timperley, Citation2007) and which is associated with large positive learning gains (Wisniewski et al., Citation2019). Because learners are required to use feedback information but do not always do so effectively (Harris et al., Citation2018; Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, Citation2006), it is important to understand how students understand, perceive, and experience feedback. Systematic research into student perceptions of feedback, grounded in psychometric methods, ensures that results meet quality expectations.

Student perceptions of feedback arise from their experience of receiving information from various sources (usually a teacher or a test) that provide potentially actionable insights (Hattie & Timperley, Citation2007). This definition instantiates a simple transmission model of feedback in which the student performs and the teacher or test evaluates the work, generating feedback as a score or commentary. Considerable early educational research focused on the impact of the simplest form of feedback (i.e., knowing one’s results; Crafts & Gilbert, Citation1935). Although this approach did not explicitly state that the student should do anything with the information, the implication was that the learner would benefit from and make changes to their work using this information (Ramaprasad, Citation1983).

Contemporary models of feedback focus on (a) a wide variety of input conditions and contexts that need to be in place so that the feedback is usable and (b) on the psychology (e.g., beliefs, motivations, emotions, attitudes) of the learner who has to process the feedback information (Lipnevich et al., Citation2016). Readers interested in the history of educational feedback theorization are encouraged to read Lipnevich and Panadero (Citation2021) and their integrative model (Message, Implementation, Student, Context, Agents; MISCA) based on that history (Panadero & Lipnevich, Citation2022). The MISCA model positions the recipient characteristics, rather than the content or delivery of feedback, as central to what is currently known about feedback and how feedback should be designed.

Thus, understanding how learners understand, experience, and respond to feedback is necessary for designing feedback messages, and their delivery, to promote the agentic use of feedback. There are many theoretical frameworks (e.g., interest, expectancy-value, goal orientation, agency, achievement motivation, motivation-hygiene, goal setting, mastery beliefs, self-concept, attribution, self-determination, planned behavior, etc.) that provide insights and evidence as to how students might respond to or think about feedback (see Fong & Schallert, Citation2023/this issue). The multiplicity of motivational or learning theories and their substantial overlap (Hattie et al., Citation2020; Murphy & Alexander, Citation2000) means that there is no one theory of how feedback functions. Nonetheless, in this article perceptions of feedback are positioned as a potentially potent self-regulatory control process.

Feedback in education requires a prior performance or product that receives either constructive formative or terminal summative evaluation (Hattie & Timperley, Citation2007). Because educational feedback happens in the sequential process of classroom instruction (i.e., after or during student performance), it makes sense to approach it from the perspective of self-regulation of learning (SRL; Boekaerts & Corno, Citation2005; Butler & Winne, Citation1995; Zimmerman, Citation2002). For feedback to be effective, students need to take responsibility for understanding and making use of feedback to improve their future learning outcomes or processes. Such actions are fundamental to the notion of self-regulation of learning. Feedback from teachers is generally intended to support students in regulating their learning and result in better performance, as seen in several studies of teacher feedback impact on SRL (Fatima et al., Citation2022; Guo, Citation2020; Hernández Rivero et al., Citation2021). Feedback and SRL are linked through the internal cognitive feedback learners give themselves (Butler & Winne, Citation1995) and by the external feedback they receive and reflect upon (Zimmerman, Citation2002). The feedback that supports learning also supports student SRL (Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, Citation2006). Thus, SRL provides a suitable framework for understanding how students receive, interpret, and exploit feedback.

Feedback seeking is a proactive behavior to obtain information from the environment to monitor and improve performance (Ashford et al., Citation2016). Feedback-seeking strategies (i.e., inquiring for feedback and monitoring for indirect feedback) enhance creative performance (De Stobbeleir et al., Citation2011). Thus, if students do not have a strong basis for making robust judgments when required to self-assess their work, they are likely to seek insights from formal external feedback (e.g., grades, test scores, and peer or teacher comments; Yan & Brown, Citation2017) rather than rely on their own internal sources (e.g., physical sensations) or monitoring of the environment (Joughin et al., Citation2021). Within SRL, effective learners would seek feedback to inform their own self-assessments (Harris & Brown, Citation2018), provided the environment supported such efforts (Yan et al., Citation2020).

Thus, research into how students regulate their responses to feedback includes an understanding of how they perceive it, react to it, ignore or use it, and otherwise psychologically respond when receiving feedback. In order to examine the research literature on student perceptions of feedback, the next section outlines the key principles of psychometric methodology as the basis for evaluating the quality of psychological research on feedback perceptions.

Psychometric theory and practice

Psychometrics concerns the scientific application of systematic methods to eliminate alternative explanations (e.g., error, bias, randomness, or rival hypotheses) for psychological phenomena (e.g., attitudes, performance, motivations, etc.) and to estimate the size, direction, or strength of such constructs. Psychometrics grew out of “psychological scaling, educational and psychological measurement, and factor analysis” (Jones & Thissen, Citation2006, p. 8) and is “the disciplinary home of a set of statistical models and methods that have been developed primarily to summarize, describe, and draw inferences from empirical data collected in psychological research” (Jones & Thissen, Citation2006, p. 21). Psychometrics combines statistical mathematical tools with postpositive hypothetical-deductive science (Philips & Burbules, Citation2000) to identify and measure latent unobservable psychological constructs (Borsboom, Citation2005) and relate them to predictors and consequences. These statistical methods evaluate the accuracy and validity of the measures used to understand humans.

Psychometric protocols that constitute best practice in evaluating psychological phenomena have been developed for over a century to measure and validate what individuals say about themselves. This is necessary because self-reports can be erroneous as a result of memory problems (Schacter, Citation1999), lack of self-awareness about competence (Dunning et al., Citation2004), the need to protect the ego or “self” (Boekaerts & Corno, Citation2005), or even the desire to subvert research (Fan et al., Citation2006). To further reduce error and noise that can arise from small samples or using single items as measures, psychological self-report research (Allport, Citation1935) relies on a “Multiple Indicators, Multiple Causes” (MIMIC) framework (Jöreskog & Goldberger, Citation1975). MIMIC models use multiple indicators (i.e., the specific items answered by the respondent) to estimate unmeasured hypothetical or latent constructs that are putatively responsible for the responses. This means that self-report questionnaires or inventories contain multiple items to probe each key aspect of a construct to ensure participants focus on all the theoretically important features of the construct, rather than respond to just one aspect of the construct. This maximizes the probability that an informant will provide valid, replicable patterns in their responding to the theoretical framing of the construct.

In a MIMIC model, participant responses to any questionnaire item are seen as being caused by two sources; that is, the underlying latent psychological construct and random unexplained factors that influence responding (e.g., distraction, inattention, lack of effort, etc.). Because MIMIC models account for the prominence of randomness, they provide a means of removing those sources of variance from latent construct scores, resulting in insights that are more purely representative of the construct of interest. Further, using the MIMIC framework, it is possible to estimate the strength and direction of theoretical relations or paths (i.e., correlations or regressions) from one or more manifest responses or latent constructs to other responses or constructs. MIMIC models include all types of factor analysis, including principal component analysis (PCA), exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis (EFA and CFA respectively), and structural equation models (SEM) (Jöreskog & van Thillo, Citation1972). The MIMIC framework thus provides a mathematical basis for determining whether participant responses conform to theoretical expectations in both the measurement of constructs and the structural relations among constructs.

Because psychological phenomena, including perceptions of feedback, are latent (i.e., not directly observable), inferences about their nature and function must be based on robust theory about how, in this case, learners perceive and respond to feedback. Validation evidence for instruments usually begins with preparatory techniques (e.g., pilot studies, International Test Commission, Citation2017; expert judgment panels, McCoach et al., Citation2013; participant think-aloud studies, van Someren et al., Citation1994; and cognitive interviews, Karabenick et al., Citation2007) that show that the items align with the theory and are understood as intended by participants. Statistical evidence for the coherence of a scale comes from mathematical methods such as exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, item response theory (Cudeck & MacCallum, Citation2007; Embretson & Reise, Citation2000), and from scale reliability estimation (McNeish, Citation2018). Once theoretically defensible scales are created, scores are calculated (DiStefano et al., Citation2009) to afford inferences about the nature and/or quantity of important internal psychological attributes.

However, the validity of self-report scores, even when meeting internal evidence expectations, depends on the relationship of latent construct scores to other constructs, especially those behaviors that are independent of what individuals self-report (Cronbach, Citation1988). The degree to which self-report scores act in accordance with theoretical predictions should be seen in convergent relations to conceptually similar constructs and divergent or negative relations to those which are conceptually different (Campbell & Fiske, Citation1959). Data from biometric evidence (e.g., fMRI; Kim et al., Citation2010; Meyer et al., Citation2021), online behaviors (i.e., mouse clicks, time lapsed, routes used, etc.; Lundgren & Eklöf, Citation2020), attendance (Wise & Cotten, Citation2009), measures of academic performance (Brown et al., Citation2009; Marsh et al., Citation2006), and other sources show whether variation in latent construct scores is meaningfully related (i.e., causally or explanatorily) to self-reported constructs that should be sensitive to such variation (Borsboom et al., Citation2004; Zumbo, Citation2009). The implication is clear: understanding how student perceptions of feedback matter to behaviors or outcomes requires strong attention to the principles of psychometric measurement and validation (e.g., sample size and appropriate analytic methods).

Once validation evidence to appropriate external constructs is established, it is important to determine that the result is not a function of chance artifacts within the data set obtained. Thus, replication of results is essential (Makel et al., Citation2012) across groups or times. Given the complexity of psychological factors impinging upon behaviors, the impact of any specific perception on a subsequent behavior or outcome may be quite small and hard to replicate (Lindsay, Citation2015). So, it is difficult to replicate previously published results with small-scale studies (n < 100) (Cohen, Citation1988), whereas studies with larger samples can detect small effects.

In the end, a conclusion about whether there is robust evidence for the existence of a latent construct and its measurement depends on an overall judgment (Cizek, Citation2020; Cronbach, Citation1988; Messick, Citation1989) as to the degree of support (e.g., “preponderance of evidence”, “clear and convincing evidence”, “substantial evidence”; Cizek, Citation2020, p. 26). Good psychometric approaches for the validity of a self-report inventory should generate prima facie evidence, coherent with some theory or conceptual model, that the instrument used to elicit participant data aligns faithfully to a theoretically robust description of what the construct is, how it functions, and what it should do. Robust statistical evidence is needed to show that how participants responded aligns with the theoretical framework developed from prior research. Otherwise, the grouping of items may reflect the a priori expectations of the researcher, reflecting a potential “halo” effect (Thorndike, Citation1920). Given the power of chance, evidence is needed that measurements are reproducible with other groups from the same population and exhibit stability over time. Similarly, evidence is needed that variation in scores has a theoretically explainable relationship with other self-reports, behaviors, or outcomes and, ideally, that experimental manipulation produces changes in a theoretically proposed direction.

In light of these expectations, we review contemporary self-report measures of student perceptions of feedback and judge the quality of the evidence against these standards. The goal is to ascertain if this quality of research exists around student perceptions of feedback and if it exists, what it might say about if and how perceptions matter to educational outcomes, learner behaviors, or attitudes.

Method

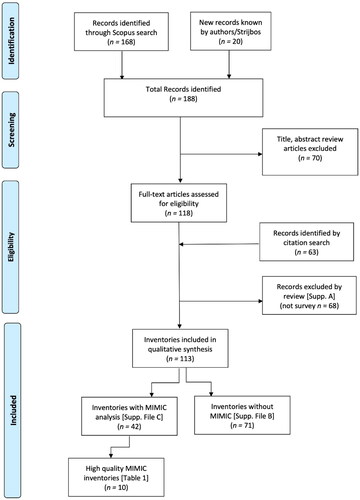

We systematically searched the literature for feedback-related self-report inventories. A first systematic search in Web of Science for measurement inventories in student perceptions of feedback did not identify articles meeting the search criteria. However, a search in Scopus produced many relevant results. To ensure results focused on the key construct of student perceptions of feedback, the words “feedback” and “student” were required to appear in the title. To ensure coverage of the topic, the search field was extended to the title, abstract, or keywords for synonyms of “perception” (i.e., conception, perspective, orientation). To capture feedback perceptions inventories, the search field for synonyms of “measurement” (i.e., test, questionnaire, survey, or scale) were sought from anywhere in the record. Likewise, to increase the likelihood that MIMIC methodology had been used the terms “factor” and “analysis” were sought from anywhere in the record. The publication date was restricted to 2000 and beyond to identify contemporary research. For replication purposes, the Scopus search string is provided:

((TITLE(feedback) AND ((TITLE(student)) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(perception* OR conception* OR perspective OR orientation))) AND (measurement OR test OR questionnaire OR survey OR scale)) AND (factor AND analysis) AND PUBYEAR > 1999

A first-round based on reading titles produced an agreement for 125 items on whether or not the inclusion criteria were met (75% consensus, κ = .50), with 41 items not in agreement. A second round of reading titles and abstracts produced agreement on a further 27, resulting in 92% consensus (κ = .83). The 14 items that did not get agreement were retained for detailed inspection. From 188 unique items, 70 articles were removed because they did not qualify.

The remaining 118 sources were scanned to identify an additional 63 sources mentioned in the reference lists that seemed to relate to student perceptions of feedback. This meant 181 records were evaluated for inclusion in the review. Of these, 68 were excluded for multiple reasons (i.e., not about student perceptions of feedback, n = 20; not in English, n = 3; not possible to access, n = 3; used qualitative methods, n = 28, a review, n = 6, pre-2000, n = 8; Supplementary File A). Another 71 studies used survey methods but did not use MIMIC methodologies and so were removed (Supplementary File B). Many of these removed articles reported analysis of each item separately without considering possible aggregation of items into sets or factors, only gave scale reliability information without evaluation of factor structure, or relied on previously reported factor structures without validation in the sample being described.

The remaining 42 records were evaluated for the statistical procedures used, the number of samples used, and the type of validation evidence provided. Each article was scored on each of these dimensions, with details of scoring provided. In terms of statistical method, principal component analysis (PCA) was scored = 1 because it does not give researchers a way to separate error variance from item scores or their composite (Bryant & Yarnold, Citation1995). In contrast, both exploratory (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) allow researchers well-established methods for estimating and removing error variance from item scores and any composite scores that might be computed. EFA was scored as 2 because it allows off-factor loadings to be different to zero. CFA was scored as 3 because it requires non-specified paths (i.e., off-factor loadings) to be zero. The logic of CFA then provides the strongest test of alignment between theory (e.g., a model of items which belong to a specific factor and not to another) and data (i.e., the model has off-factor values so small, that it is legitimate to accept the model). This element of the coding was based on the “strongest” form of evidence included within a paper. All studies using CFA or structural equation modeling received the same methods score of 3, even if they also reported PCA or EFA. This hierarchy of methods gives greater weight to models that allow for estimating and controlling for error in the model (i.e., EFA and CFA) and which impose the greatest restrictions (i.e., CFA).

In terms of the number of samples used, studies with one single sample were scored 1, whereas those with more than one sample or which split the sample into two groups were awarded 2. Having two or more samples allows for psychometric evidence derived from one sample to be tested for equivalence in the second other or later samples. In terms of validation evidence, those with internal psychometric evidence only were given 0, those that related perceptions to self-report scores scored 1, and those that had a behavioral or performance measure gained 2. This weighting recognizes the importance of evidence that is not self-reported or subject to bias. The maximum possible score was 7. The modal sum score across the three variables was 5, with only 10 inventories scoring 6 or 7, whereas 17 had values of 4 or less. All 10 inventories with total scores of 6 or 7 had a score of 3 for the statistical method criterion.

Detailed reporting is restricted to the ten inventories with scores of six or seven on the grounds that these studies exhibit the most robust psychometric evidence (). This restriction means that only studies with high-quality statistical methods (i.e., statistical, replication, and validation processes) were used to examine what is known about how student self-reported feedback perceptions relate to external variables or behaviors. Having reduced the population of records through systematic review protocols to the most psychometrically robust sample, next we provide an overview of the study characteristics and thematic categorization of findings.

Table 1. High quality student feedback attitude inventories.

Results

We report first the major characteristics of the ten retained inventories in terms of useful background characteristics of each study, such as the participants, the feedback context, the status of the inventory, the type of feedback given, and the psychometric features of the studies. We then examine the theoretical constructs used to understand student perceptions of feedback and the external evidence used to validate claims about the meaning of student perceptions of feedback.

Characteristics of studies

provides a high-level summary of the characteristics of these ten reports. For efficiency of reporting all studies are referred to by a numeric ID as shown in . Six studies used undergraduate students and four studies used primary or secondary school students; note one study used both undergraduates and secondary students (#124, Studies 1, 2a, and 2c). Thus, more is known about how undergraduate university students perceive feedback than any other group. Because context matters, it is useful to note that only three studies were conducted outside western nations (i.e., Tanzania #49, China #98, and Hong Kong #91), although it is worth considering that enrollment in western higher education now includes students from multiple locations. Nonetheless, the research is dominated by studies in Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) cultures (Henrich et al., Citation2010).

Table 2. Psychometric properties of high-quality student feedback perception inventories.

In terms of subjects in which feedback was generated, four studies (#97, 111, 128, 129) did not specify in what learning area the research was conducted, whereas two studies (#49, 91) involved mathematics, and one each in English as a Foreign Language (#98), Communication (#114), and General Education (#28). The one study with a behavioral measure (#124) linked feedback to personal health rather than an educational topic.

Six studies reported the original development of a new perceptions inventory (i.e., Students’ Perceptions of Teachers Level of Feedback Questionnaire [SPTLFQ; #98], Feedback Perceived Usefulness & Frequency Scales [FPU and FPF; #91]; Feedback Orientation Scale [FOS; #111], Instructional Feedback Orientation Scale [IFOS; #114], Information Avoidance Scale [IAS; #124], and German Feedback Socialization Inventory [FSI; #129]). Two studies reported using previously developed inventories (i.e., Student Conceptions of Feedback [SCoF], Irving et al., Citation2007; and Assessment Experience Questionnaire [AEQ], Gibbs & Simpson, Citation2003), whereas #49 used scales from the Students Assessment for Learning Questionnaire [SAFLQ] (Pat-El et al., Citation2013), feedback utility from IFOS (#114), use of feedback from the AEQ, and delivery of feedback from the FES (Steelman et al., Citation2004). In the tenth study (#128), Jellicoe and Forsythe (Citation2019) adapted a scale previously developed with adult workers in occupational contexts (#119, Supplementary File A) and extended it to the educational context to create the Feedback in Learning Scale (FLS).

In terms of construct development, only studies developing an original new scale reported involving humans in construct development. Understandably, those replicating a previously developed scale (#28, 49, 97, 128) tended to go directly to statistical modeling. Three studies claimed pilot validation efforts involving students (#91, 114, 124) or with teachers (#114) without specifying what method was used. One study used expert judgment to evaluate items (#111), one used cognitive interviews with students (#129), and none reported student think-aloud. Further, five reported a form of pre-testing (#98, 111, 114, 124, 129). It seems, in general, that the quality of evidence used to ensure participants understand the wording of these 10 inventories is somewhat weak, but this may be a consequence of the inclusion criteria, which was likely to exclude studies that reported preliminary inventory development processes. There may be such evidence in prior reports that were excluded by the selection criteria.

None of the selected studies linked student perceptions to specific instances of feedback, whether formative or summative. Only one study (#49) made clear the source of feedback (i.e., the teacher). This means only how students perceive feedback, in general, is known, without any insight as to specifics of how different timing, format, source, or content might impact perceptions.

Psychometric features

Consistent with classical test theory, nine studies used raw score scales to create mean scores, but one study (#91) used item response theory methods to calibrate item scores, allowing for the determination of a total score weighted by the difficulty and discrimination properties of each item answered correctly. All papers reported using a rating scale of between four and seven options, with five used most (i.e., 4 out of 10). Only four studies (#28, 49, 91, 129) used an even-numbered scale (Krosnick & Presser, Citation2009), thus avoiding potential ambiguity concerning the meaning of a midpoint on an odd-numbered scale (Brown & Shulruf, Citation2023). All but one used an “agreement” response scale, a response framework that seems an appropriate basis for establishing current attitude or orientation toward a phenomenon, rather than rely on error-prone memory of recalled beliefs, opinions, or attitudes (Brown & Shulruf, Citation2023).

By selection, these ten studies all used the strongest psychometric methods that account for error (i.e., CFA or SEM) to test for alignment between theory and data. Nonetheless, all reported scale reliability with coefficient alpha, rather than the more appropriate Coefficient H or McDonald’s omega indices (McNeish, Citation2018). To account for rival, alternative hypotheses, three studies (#28, 111, 129) reported explicitly testing alternative models, an important step in minimizing researcher bias in selecting a preferred model.

Four studies (#114, 124, 128, 129) replicated the fit of the model to one or more additional samples. Unfortunately, none of the studies applied nested invariance testing to establish that the model was equivalent across samples (Byrne, Shavelson, & Muthén, Citation1989). Two studies (#111, 124) reported test-retest reliability with acceptable replication coefficients. In sum, these studies included partial evidence for the replicability of the statistical model for the inventory, but none presented sufficiently robust and comprehensive evidence.

Theoretical framing

All of the studies reviewed here reported linking student perceptions of feedback to another self-reported attitude, perception, or belief. A wide range of feedback perceptions was reported. The most common in six of ten reports had to do with the utility, motivating power, or usefulness of feedback (#28, 49, 91, 97, 111, 114, 128). At least 25 other aspects of how feedback is perceived were reported, including how often or well feedback is provided (#49, 91, 97), the source of feedback (#28), emotional responses to feedback (#114, 124, 128), and the impact of feedback on self-regulatory behaviors (#98, 111, 128, 129). Each of the ten studies included investigations of convergent or divergent validity evidence, in some cases reporting both. Self-regulation of learning, self-efficacy, and emotional response were three constructs used to evaluate convergent and/or divergent validity evidence. The reported relationships, despite being variable in strength, tended to be theoretically coherent.

Self-regulation of learning

Consistent with SRL theory (Butler & Winne, Citation1995), planning, monitoring, and adaptive reactions were all increased by greater perceived feedback usefulness and perceived feedback frequency (#91), as was metacognitive self-regulation when students endorsed actively using and enjoying feedback (#28). Greater endorsement of feedback utility correlated with the greater agreement that having one’s performance appraised is useful and greater agreement that being involved in development activities is beneficial (#111). Greater intention to use feedback was associated with an internal obligation to respond to and follow up on feedback, seeing feedback as a means of knowing, and being sensitive to how others’ view oneself (#111). Perceived utility of feedback was correlated with greater communication competence, intellectual flexibility, and more positive feelings about receiving classroom feedback (#114). Adaptive help-seeking within SRL involves knowing when to get help, including feedback from others on how to improve (Karabenick & Berger, Citation2013). Greater seeking of feedback for improvement has been shown to depend on a set of interrelated beliefs, including motivation to develop in line with feedback, accepting that feedback comes from a credible source, and having greater awareness of personal strengths and needs (#128).

In contrast, undergraduates who reported avoiding feedback information, especially about their own health or their partner, had decreased agreeableness, openness, self-esteem stability, self-esteem, state self-esteem, monitoring, curiosity, and optimism, with increased uncertainty intolerance and neuroticism (#124, Study 1). Based on a self-reported survey dealing with a university study (#129), a greater endorsement of effort and strategy related to feedback after success was positively correlated with coping, planning, and reduced behavioral disengagement. After failure, greater endorsement of domain-specific person and effort feedback resulted in reduced coping and increased behavioral disengagement. However, endorsement of constructive strategy feedback after failure correlated with greater planning and less behavioral disengagement.

Self-efficacy

Consistent with self-efficacy theory, #97 found that greater academic self-efficacy for studying, grades, and verbalizing was positively correlated with the endorsement of using feedback and its quantity and quality. Likewise, greater self-efficacy was seen when students endorsed actively using and enjoying feedback (#28) and when the utility of feedback was endorsed (#114). Self-efficacy declined when participants increased in their tendency to avoid information (#124, Study 1). Greater self-efficacy for feedback (i.e., competence to interpret and respond to feedback appropriately) was associated with greater (a) satisfaction and utility from professional development and appraisal sessions, (b) intentions to use feedback, (c) role clarity, (d) greater ratings from supervisors, and (e) self-monitoring, along with (f) less resistance to change (#111).

Emotional response

Those studies that related feedback perceptions to “satisfaction” tended to show that negative feedback was associated with negative emotions. For example, #114 reported that sensitivity to critical or negative feedback was correlated with less communication competence and more apprehension around listening and reading. Likewise, those reporting not remembering feedback had greater apprehension or anxiety regarding those same two communicative skills. After success, #129 reported positive correlations between personal satisfaction and all four aspects of feedback (i.e., general person, domain-specific person, effort, and strategy), whereas after failure the correlations with the same feedback factors were negative. Participants reported the same pattern of correlations for perceived parental satisfaction (i.e., positive in success and negative in failure). However, unsurprising considering extensive research into student achievement emotions (Vogl & Pekrun, Citation2016), satisfaction with feedback did not automatically imply activation or deactivation of behavior or effort.

External validation

Six studies reported a relationship between feedback perceptions and measures of academic achievement, whereas just one study provided evidence related to behavior (#124). In terms of the relationship of feedback perceptions to academic performance measures, the role of perceived utility or usefulness was consistently positive, but variable in size. Qualitative interpretations of beta values and correlations follow Cohen (Citation1988).

Self-reported use of feedback by students had a moderate association with term GPA (#28), a small association with tested mathematics performance (#49), and a trivial association with attainment (#97). Consistent with Hattie and Timperley’s (Citation2007) framework, process and self-regulation feedback contributed moderately to language proficiency (#98). In a German study with undergraduates (#129), after success general person feedback was moderately associated with increased school grades, whereas simultaneously small increases were associated with domain-specific person, effort, and strategy feedback. In contrast, after failure, most feedback beliefs (i.e., general person, domain-specific person, effort, and general strategy) had small negative associations with grades. A New Zealand study with undergraduates (#28) reported that term GPA decreased with perceptions of peer feedback helping (small effect size) and with feedback as tutor comments (medium effect size), suggesting that these beliefs moved responsibility for better outcomes from the individual being assessed. In a Tanzanian secondary school study (#49), students who perceived feedback as scaffolding their work, rather than monitoring it, had a greater willingness to use feedback for better performance (large effect size).

Only one study (#124) reported associations with actual behavioral action, albeit in response to feedback about a hypothetical situation involving exposure to a fictional disease (i.e., thioamine acetylase (TAA) deficiency). When undergraduates were faced with the choice to receive (or not receive) personalized health risk feedback, the choice to receive that feedback had either a moderate or large inverse association with avoiding feedback information. Greater commitment to avoiding information produced the expected choice not to receive health feedback. However, the applicability of this result to educational settings (e.g., knowledge about one’s poor test performance) will depend on transfer studies with the inventory to test for replicability across domains.

Discussion

To ascertain what is known about the nature of student perceptions of feedback and whether there is evidence for the validity and impact of claims about those perceptions, a systematic review of the contemporary literature was conducted. Papers were selected in accordance with quality indicators derived from psychometric research principles. Self-regulation of learning was used as a lens to interpret student perceptions of feedback. Just ten papers from 251 met all criteria for modeling of responses, an association of responses to theoretically relevant convergent or divergent self-reported constructs, use of multiple samples, and/or evaluation of perceptions against external measures of behavior or performance. Students who claimed greater willingness to value, receive, and use feedback exhibited greater self-efficacy, greater SRL, more positive emotional responses, and greater academic performance. Although actual behaviors are not known in learning contexts, it seems highly likely that utility-oriented perceptions of feedback produce adaptive self-regulated learning actions. Feedback perceptions clearly exist, but there is still little consistency in the data about how student belief systems concerning feedback meaningfully relate to self-regulation of learning.

This analysis focused only on ten studies that had used the strongest psychometric methods to analyze the relationship of a model to the data making use of formal MIMIC methods. These ten studies stand out from Supplementary File C studies for having extended a strong MIMIC-based analysis by explicitly testing multiple samples or providing validation evidence for the meaning of the self-reported perceptions of feedback. This review shows that between 25 and 30 distinct perceptions of feedback have been identified suggesting clearly that student perceptions of feedback are multi-dimensional. Because feedback must fulfill both formative and summative functions and because human responses to feedback are complex, it is not surprising that most research has positioned student perceptions of feedback as multidimensional. Consequently, it is unlikely a single feedback perceptions score can be justified; instead, scores for each dimension are needed.

This review finds among these statistically robust studies that, coherent with self-regulated learning theory (Boekaerts, & Corno, Citation2005; Butler, & Winne, Citation1995; Zimmerman, Citation2002), the evidence for the impact or consequence of the feedback perceptions is reasonably strong for measured performance in a subject domain. The strength of the relationship to achieved performance is variable, but, consistent with self-regulated learning theory, students who perceive utility in feedback and report using it tend to do better. Nonetheless, behavioral responses of learners to feedback is practically non-existent in this data set. However, it is likely that adaptive actions do follow productive growth-oriented intentions (Ajzen, Citation1991, Citation2005), a clear field for further detailed research—what do students do with feedback, especially when performance matters? That there is evidence for a relationship between feedback perceptions and academic performance does not eliminate the possibility that academic performance arises from underlying mental ability (Neisser et al., Citation1996) or socio-economic resources (Sirin, Citation2005) rather than student perceptions of feedback. Studies that control for prior academic ability or intelligence and socio-economic status are needed to determine if the impact on achievement is simply a reflection of greater mental abilities or resources.

Further, these studies reveal meaningful relations to other relevant self-reported constructs (i.e., self-regulation of learning, self-efficacy, and achievement emotions). The theoretical basis for latent attitudinal traits as a cause of intentions and behaviors seems robust (Ajzen, Citation2005). These articles provided evidence from self-reported scores that feedback perceptions had empirical alignment with theoretical predictions, giving coherence and defensibility to those scales. However, this coherence with theoretical expectations may arise from a general method effect (i.e., all data are self-reported), constituting a potential alternative explanation for shared variance. Nevertheless, as a stepping stone toward robust validation of the meaning of feedback perceptions, this type of evidence is necessary but not sufficient, because of the potential for biases in self-reports. Further, given that there is considerable overlap theoretically in the development of these inventories and that the learning environments are similar, it may be that the distinctions in factor structures and names between the feedback perceptions inventories are quite small. As yet, no equating studies have been conducted to find an overlap between the many perceptions of feedback factors identified in these ten studies. Such work is important to minimize jingle-jangle (i.e., apparent similarity or dissimilarity of constructs when not actually the case) and thus ensure transparency in how the profusion of feedback inventories contributes to the field (Flake & Fried, Citation2020).

However, the evidence of the impact of feedback on student learning behaviors in these robust studies is unfortunately almost non-existent. By controlling the range of perceptions to a single factor (i.e., the tendency to avoid information), study #124 has provided evidence that behavior was associated with perception. Perceptions about the utility and use of feedback seem to matter for achievement. But which feedback perceptions matter most for psychological well-being or life success is not understood, nor is it clear which learning-related or study behaviors arise from various feedback perceptions. This represents a rich opportunity to move the identification of feedback perceptions into a powerful evaluation of their role and impact.

Unfortunately, of the ten highly rated studies, only three reported using multiple samples for replication (#114, 124, 129) but of those, none tested for equivalence in responses, which would normally be expected in MIMIC data analysis (Brown et al., Citation2017). Thus, there is a lack of robust evidence that the current inventories are robust across samples from the same population. More importantly, there is a clear need for replication research to test the validity of these inventories in other contexts, especially beyond WEIRD samples. Nor is it known if there are differences between cultural and ethnic groups within WEIRD populations. Hence, the current crop of most robust inventories still needs replication research to investigate whether, to what degree, and in what contexts these inventories are invariant.

All the selected studies here position student perceptions in terms of feedback in general; no information is given as to the content, type, source, or timing of the feedback all of which matter to responses. Further, it is not possible to determine whether feedback perceptions differ across academic disciplines, nor, given the small sample sizes within disciplines, can it be assumed that there is homogeneity of perceptions within disciplines. Clearly, replication studies with these inventories need to specify the characteristics of the feedback and in which learning context it is studied. It may be that formative feedback from peers within primary school mathematics, for example, is perceived in a different way to feedback from the teacher in arts or humanities for a summative assessment. All of these facets matter; hence, there is as yet no robust understanding of how those features relate to how students make use of that feedback.

Further, given that humans and their educational environments are so variable, there may not be any single set of perceptions or relationships that can be replicated in all contexts. The current sample of studies () has little consistency in terms of student age, subject domain, or types of feedback. Hence, it is premature to claim that there is much certain knowledge about student perceptions of feedback across these multiple studies—it seems comparisons of apples with oranges are being made to reach conclusions about fruit. Nonetheless, replication studies that control context-specific variability will help to validate measurements of student perceptions of feedback. Such results render instruments credible for use within a specific context. As yet, insufficient research using robust MIMIC methods has aimed at replicating results with robust samples from the same population; doing this maximizes the possibility that invariance of measurement models will occur (Wu et al., Citation2007). This review explicitly excluded studies using qualitative methods on the grounds that they are prone more than psychometric studies to chance artifacts within small samples. This does not mean that such methods are without merit because it is unlikely semi-structured interviews should either confirm or contradict latent theory MIMIC survey results (Harris & Brown, Citation2010). Nonetheless, it seems essential to understand how students perceive feedback, especially in the specificity of how and when it is implemented, and how they think they should respond to it. Learner self-reports provide insight into how students understand what feedback means, how it makes them feel, and what they claim to have done with it.

Given the importance of socio-cognitive theory (Bandura, Citation1986) to educational interventions and the agency learners have (Harris et al., Citation2018), it is impossible to ignore the likelihood that feedback will not work as intended by the feedback giver without the active awareness and engagement of feedback recipients. This is essential if educational interventions are to be devised, tested, and promulgated into teaching. It is not known if student perceptions of feedback can be changed from something to be rejected or ignored to something with which they can actively engage. Weak evidence exists that feedback literacy responses can increase through interventions (Little et al., Citation2023), but that scoping review showed that evidence of behavioral changes did not exist. However, there is evidence that students can be taught to regulate their own learning (Kirschner & Hendrick, Citation2020), hence it is likely students can be taught to actively engage with and use feedback for growth rather than avoid it for ego-protection or enhancement. Consequently, without controlled pre- and post- intervention data, it cannot be assumed that educators can change student perceptions of feedback, or that such changes will lead to better behavior or outcomes. But this remains clearly a need in the field.

Research into student perceptions of feedback must become dissatisfied with replicating general perceptions, otherwise, the influence of feedback timing, format, source, or content upon subsequent behavior or performance will remain uncertain. The psychometric methodology defines what those studies must look like and how they are to be conducted. Fortunately, given the size of education systems, it is possible to conduct large-scale psychometric research while associating it with specific contexts.

Limitations of this review

A limitation of the search reported here, considering its success with Scopus, is that a revised search in Web of Science was not carried out. This may not be a problem because Elsevier’s Scopus database is more comprehensive in its inclusion of psychology and education journals than Clarivate Analytics’ Web of Science (Stahlschmidt & Stephen, Citation2020). Nonetheless, future researchers may wish to include both Web of Science and Digital Science’s Dimensions database, which is a new database that is based on open-access data sources and is thus even more comprehensive in Psychology and Educational Sciences (Stahlschmidt & Stephen, Citation2020).

There are potentially interesting studies among those excluded from our analysis, primarily because they did not include multiple samples or provide validation with the outcome or behavioral measures. Some of the studies in Supplementary File C had linkages to either behavioral or academic outcomes. Additionally, there were 16 studies in Supplementary File C that used CFA and 12 that had sample sizes ≥500. Readers are encouraged to review these studies to determine whether to conduct further validation and replication studies.

A potential limitation to this paper is our focus on MIMIC-derived methods, without explicitly including other psychometric methods in the search strategy. It may be that including IRT and Rasch as a search term would produce different results. It may also be that there are considerable insights into student perceptions of feedback in the various qualitative studies and non-MIMIC studies listed in the three Supplementary Files. This limitation means that there may well be other important perceptions which have not been subjected to the methodological scrutiny used in this review.

Recommendations for future research

This review makes clear that most research in the field of student perceptions of feedback fails to meet psychometric standards. This raises doubts about the replicability and generalizability of much of what is claimed concerning how students perceive feedback. The review shows that researchers are increasingly using strong methods of psychometrics (Supplementary File C has 16 papers with CFA methods). However, efforts are still needed to include independent validation measures and replication samples to move the field out of the current morass of small sample, highly subjective designs, and analyses (see Supplemental File A). Adopting the psychometric framework would reduce the chance artifacts associated with small-scale, exploratory studies or those which do not exploit the MIMIC framework.

Additionally, almost no high-quality research has been done in education that links perceptions of feedback to subsequent behaviors, which is a key objective of psychological science. Such research provides independent validation of the meaning and consequence of student perceptions. However, in calling for research with behaviors, this does not imply that a focus on behaviors alone is appropriate. Learners are agentic, autonomous beings and their experience of education is not just a humanistic concern. Without awareness of how learners experience feedback, educators will not be able to improve, change, or maximize the effectiveness of their feedback.

However, for student perceptions of feedback research to reach its potential value several important changes are needed to increase the strength of evidence concerning student perceptions of feedback. Exploiting psychometric industry methods to minimize alternative explanations for results will strengthen future research. The following psychometric methods are needed to mitigate threats to the validity of self-report measures so that research is more powerful. To minimize the researcher’s “halo” of expectations, there needs to be evidence that respondents understand survey stimuli in the same manner as the researcher intended. Hence, direct insights from student focus groups, cognitive interviews, or think-aloud processes will give confidence that the instrument has face validity. Researchers need to use multiple procedures to mitigate chance artifacts in designing items, choosing samples, and arguing for factor structures. To do that, multiple indicators are needed for each dimension or factor to strengthen conclusions about the valence and strength of those perceptions. The strongest statistical tests of factor structure (i.e., CFA) need to be applied to ensure robust mapping of items to constructs and multiple samples from the same population need to be tested to demonstrate that the model is invariant within a population.

To avoid making false generalizations concerning how students perceive all feedback, replication research needs to anchor student perceptions to specific features of feedback in terms of its timing, source, style, and content. The field in general needs to extend sampling beyond higher education to cover more age levels, subject domains, and cultural contexts. To maximize the meaningfulness of student perceptions of feedback and to mitigate against social desirability in self-report data, links to independent variables, such as academic outcomes or uses of feedback, need to be included using robust methods (e.g., SEM) embedded in the MIMIC framework. Experiments that test the potential to modify negative perceptions and validate that this leads to positive changes in behaviors and outcomes are needed. To avoid confusion in the field, systematic conceptual and empirical equating studies are needed to identify the probable overlap among the many perception factors already extant. Heeding these principles will enable researchers to robustly claim that their surveys have minimized chance artifacts, increased the face and construct validity of their instruments, and shown that student perceptions matter to behaviors associated with learning. Future researchers should consider these principles when initiating new research in the field of student perceptions of feedback so that the list of high-quality studies in the future will be greater than ten.

Conclusion

This review clearly identified a small number of high-quality measures of student perceptions of feedback. From these studies, a reasonably robust understanding was obtained that student perceptions of the utility and their use of feedback leads to greater academic performance. Students who believe in and report using feedback do better academically, in accordance with a recent meta-analysis of the power of feedback (Wisniewski et al., Citation2019). Utility and use perceptions of feedback matter to performance and align well with the theory around competence and control beliefs, but it is an assumption that this happens through self-regulatory behaviors. Nonetheless, little is known about how feedback perceptions relate to independently measured behaviors. Additionally, little is known about contextual, cultural, or disciplinary patterns in how feedback is perceived. Neither is it certain how any specific form, timing, or source of feedback relates to self-perceptions of competence or confidence, behavior, or academic performance. As a starting point, researchers ought to consider using the ten inventories described in this review.

The advantage of using psychometric approaches to accessing the mind of the learner is that these methods formally address the power of error and the possibility of chance when obtaining insights from humans. Structured item sets, response formats, pre-specified dimensionality designs, multiple robust methods to establish measurement properties, and multiple methods to establish the validity and impact of those dimensions address weaknesses in less structured research into human beliefs and attitudes. Without psychometric methods, knowledge about student perceptions of feedback would be dependent on small samples of highly interpretive analyses prone to chance artifacts in the data set or to theoretical perspectives that cannot be tested, reproduced, or replicated. Hence, the psychometric discipline provides strong norms and conventions for defining and measuring a latent construct and for validating it. Additionally, coherent with a scientific approach, theories that fail in weakly designed studies are immune from rejection. In contrast, with robust methods, it is possible to discover that some theories are less powerful than initially argued (e.g., the now small impact of a growth mindset; Yeager et al., Citation2019). Without psychometric approaches, it will not be possible to know reliably what humans think, feel, or believe and then how they might use our educational practices. With the methods recommended here, researchers will be able to make robust claims by reducing threats to the validity of their claims.

Author contributions

Gavin T. L. Brown: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Project administration; Supervision; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing

Anran Zhao: Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Validation; Writing – review & editing

Supplementary File C MIMIC lower quality v3.docx

Download MS Word (39.3 KB)supplementary file A exclusions.docx

Download MS Word (31.5 KB)Supplementary file B no mimic sources.docx

Download MS Word (35.4 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the critical feedback provided by Prof. Naomi Winstone (Surrey) and Dr Rob Nash (Aston) throughout the drafting of this manuscript. Prof. Jan-Willem Strijbos is thanked for his suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

*=inventory retained for review in Table 1

- *Adams, A.-M., Wilson, H., Money, J., Palmer-Conn, S., & Fearn, J. (2020). Student engagement with feedback and attainment: the role of academic self-efficacy. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(2), 317–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1640184

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Ajzen, I. (2005). Attitudes, personality and behavior. (2nd ed.). Open University Press.

- Allport, G. W. (1935). Attitudes. In C. Murchison (Ed.), A Handbook of Social Psychology (pp. 798–844). Clark University Press.

- Ashford, S. J., Stobbeleir, K. D., & Nujella, M. (2016). To seek or not to seek: Is that the only question? Recent developments in feedback-seeking literature. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 3(1), 213–239. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-041015-062314

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall.

- Boekaerts, M., & Corno, L. (2005). Self-regulation in the classroom: A perspective on assessment and intervention. Applied Psychology, 54(2), 199–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2005.00205.x

- Borsboom, D. (2005). Measuring the mind: Conceptual issues in contemporary psychometrics. Cambridge University Press.

- Borsboom, D., Mellenbergh, G. J., & van Heerden, J. (2004). The concept of validity. Psychological Review, 111(4), 1061–1071. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.111.4.1061

- Brown, G. T. L., Harris, L. R., O'Quin, C., & Lane, K. E. (2017). Using multi-group confirmatory factor analysis to evaluate cross-cultural research: Identifying and understanding non-invariance. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 40(1), 66–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2015.1070823

- Brown, G. T. L., Peterson, E. R., & Irving, S. E. (2009). Beliefs that make a difference: Adaptive and maladaptive self-regulation in students’ conceptions of assessment. In D. M. McInerney, G. T. L. Brown, & G. A. D. Liem (Eds.), Student perspectives on assessment: What students can tell us about assessment for learning (pp. 159–186). Information Age Publishing.

- *Brown, G. T. L., Peterson, E. R., & Yao, E. S. (2016). Student conceptions of feedback: Impact on self-regulation, self-efficacy, and academic achievement. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 86(4), 606–629. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12126

- Brown, G. T. L., & Shulruf, B. (2023). Response option design in surveys. In L. R. Ford & T. A. Scandura (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Survey Development and Application. Sage.

- Bryant, F. B., & Yarnold, P. R. (1995). Principal-components analysis and exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. In L. G. Grimm & P. R. Yarnold (Eds.), Reading and understanding multivariate statistics (pp. 99–136). APA.

- Butler, D. L., & Winne, P. H. (1995). Feedback and self-regulated learning: A theoretical synthesis. Review of Educational Research, 65(3), 245–281. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543065003245

- Byrne, B. M., Shavelson, R. J., & Muthén, B. (1989). Testing for the equivalence of factor covariance and mean structures – the issue of partial measurement invariance. Psychological Bulletin, 105(3), 456–466. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.105.3.456

- Campbell, D. T., & Fiske, D. W. (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multi-trait multi-method matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 56(2), 81–105. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0046016

- Carpenter, S. K., Witherby, A. E., & Tauber, S. K. (2020). On students’ (Mis)judgments of learning and teaching effectiveness. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 9(2), 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2019.12.009

- Cizek, G. J. (2020). Validity: An integrated approach to test score meaning and use. Routledge.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Crafts, L. W., & Gilbert, R. W. (1935). The effect of knowledge of results on maze learning and retention. Journal of Educational Psychology, 26(3), 177–187. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0061908

- Cronbach, L. J. (1988). Five perspectives on the validity argument. In H. Wainer & H. Braun (Eds.), Test validity (pp. 3–17). Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Cudeck, R., & MacCallum, R. C. (Eds.) (2007). Factor analysis at 100: Historical developments and future directions. LEA.

- De Stobbeleir, K. E. M., Ashford, S. J., & Buyens, D. (2011). Self-regulation of creativity at work: The role of feedback-seeking behavior in creative performance. Academy of Management Journal, 54(4), 811–831. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.64870144

- DiStefano, C., Zhu, M., & Mîndrilă, D. (2009). Understanding and using factor scores: Considerations for the applied researcher. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 14(20), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.7275/da8t-4g52

- Dunning, D., Heath, C., & Suls, J. M. (2004). Flawed self-assessment: Implications for health, education, and the workplace. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5(3), 69–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1529-1006.2004.00018.x

- Embretson, S. E., & Reise, S. P. (2000). Item Response Theory for Psychologists. LEA.

- Esarey, J., & Valdes, N. (2020). Unbiased, reliable, and valid student evaluations can still be unfair. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(8), 1106–1120. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1724875

- Fan, X., Miller, B. C., Park, K.-E., Winward, B. W., Christensen, M., Grotevant, H. D., & Tai, R. H. (2006). An exploratory study about inaccuracy and invalidity in adolescent self-report surveys. Field Methods, 18(3), 223–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/152822X06289161

- Fatima, S., Ali, M., & Saad, M. I. (2022). The effect of students’ conceptions of feedback on academic self-efficacy and self-regulation: evidence from higher education in Pakistan. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 14(1), 180–199. https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-07-2020-0209

- Fong, C. J., & Schallert, D. L. (2023). “Feedback to the future”: Advancing motivational and emotional perspectives in feedback research. Educational Psychologist, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2022.2134135

- Flake, J. K., & Fried, E. I. (2020). Measurement schmeasurement: Questionable measurement practices and how to avoid them. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 3(4), 456–465. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245920952393

- Gibbs, G., & Simpson, C. (2003). Measuring the response of students to assessment: The assessment experience questionnaire. Paper Presented at the 11th Improving Student Learning Symposium.

- Guo, W. (2020). Grade-level differences in teacher feedback and students’ self-regulated learning. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 783. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00783

- Harris, L. R., & Brown, G. T. L. (2010). Mixing interview and questionnaire methods: Practical problems in aligning data. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation, 15(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.7275/959j-ky83

- Harris, L. R., & Brown, G. T. L. (2018). Understanding and supporting student self-assessment. Routledge.

- Harris, L. R., Brown, G. T. L., & Dargusch, J. (2018). Not playing the game: student assessment resistance as a form of agency. The Australian Educational Researcher, 45(1), 125–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-018-0264-0

- Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

- Hattie, J., Hodis, F. A., & Kang, S. H. K. (2020). Theories of motivation: Integration and ways forward. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101865

- Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2–3), 61–135. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

- Hernández Rivero, V. M., Bonilla, P. J. S., & Alonso, J. J. S. (2021). Feedback and self-regulated learning in higher education. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 39(1), 227–248. https://doi.org/10.6018/rie.423341

- *Howell, J. L., & Shepperd, J. A. (2016). Establishing an information avoidance scale. Psychological Assessment, 28(12), 1695–1708. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000315

- International Test Commission. (2017). The ITC guidelines for translating and adapting tests. https://tinyurl.com/t6z2v42n

- Irving, S. E., Peterson, E. R., & Brown, G. T. L. (2007). Student Conceptions of Feedback: A study of New Zealand secondary students. Paper Presented to the Biennial Conference of the European Association for Research in Learning and Instruction, Budapest, Hungary.

- *Jellicoe, M., & Forsythe, A. (2019). The development and validation of the feedback in learning scale (FLS). Frontiers in Education, 4, 84. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2019.00084

- Jones, L. V., & Thissen, D. (2006). A history and overview of psychometrics. In C. R. Rao & S. Sinharay (Eds.), Handbook of statistics (Vol. 26, pp. 1–27). Elsevier.

- Jöreskog, K. G., & Goldberger, A. S. (1975). Estimation of a model with multiple indicators and multiple causes of a single latent variable. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 70(351a), 631–639. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1975.10482485

- Jöreskog, K. G., & van Thillo, M. (1972). LISREL: A general computer program for estimating a linear structural equation system involving multiple indicators of unmeasured variables (RB-72-56). Educational Testing Service.

- Joughin, G., Boud, D., Dawson, P., & Tai, J. (2021). What can higher education learn from feedback seeking behaviour in organisations? Implications for feedback literacy. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 46(1), 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1733491

- Karabenick, S. A., & Berger, J.-L. (2013). Help seeking as a self-regulated learning strategy. In Applications of self-regulated learning across diverse disciplines: A tribute to Barry J. Zimmerman (pp. 237–261). Information Age Publishing.

- Karabenick, S. A., Woolley, M. E., Friedel, J. M., Ammon, B. V., Blazevski, J., Bonney, C. R., Groot, E. D., Gilbert, M. C., Musu, L., Kempler, T. M., & Kelly, K. L. (2007). Cognitive processing of self-report items in educational research: Do they think what we mean? Educational Psychologist, 42(3), 139–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520701416231

- Kim, S.-I., Lee, M.-J., Chung, Y., & Bong, M. (2010). Comparison of brain activation during norm-referenced versus criterion-referenced feedback: The role of perceived competence and performance-approach goals. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 35(2), 141–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.04.002

- *King, P. E., Schrodt, P., & Weisel, J. J. (2009). The instructional feedback orientation scale: Conceptualizing and validating a new measure for assessing perceptions of instructional feedback. Communication Education, 58(2), 235–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520802515705

- Kirschner, P. A., & Hendrick, C. (2020). Why independent learning is not a good way to become an independent learner. In P. A. Kirschner & C. Hendrick (Eds.), How learning happens: Seminal works in educational psychology and what they mean in practice (pp. 66–73). Routledge.

- *König, N., & Puca, R. M. (2019). The German feedback socialization inventory. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 35(4), 544–554. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000409

- Krosnick, J. A., & Presser, S. (2009). Question and questionnaire design. Elsevier.

- *Kyaruzi, F., Strijbos, J. W., Ufer, S., & Brown, G. T. L. (2019). Students’ formative assessment perceptions, feedback use and mathematics performance in secondary schools in Tanzania. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 26(3), 278–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2019.1593103

- Leckey, J., & Neill, N. (2001). Quantifying quality: The importance of student feedback. Quality in Higher Education, 7(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538320120045058

- *Linderbaum, B. A., & Levy, P. E. (2010). The development and validation of the feedback orientation scale (FOS). Journal of Management, 36(6), 1372–1405. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310373145

- Lindsay, D. S. (2015). Replication in psychological science. Psychological Science, 26(12), 1827–1832. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615616374

- Lipnevich, A. A., & Panadero, E. (2021). A review of feedback models and theories: Descriptions, definitions, and conclusions. Frontiers in Education, 6, 100416. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.720195

- Lipnevich, A. A., Berg, D. A. G., & Smith, J. K. (2016). Toward a model of student response to feedback. In G. T. L. Brown & L. R. Harris (Eds.), The handbook of human and social conditions in assessment (pp. 169–185). Routledge.

- Little, T., Dawson, P., Boud, D., & Tai, J. (2023). Can students’ feedback literacy be improved? A scoping review of interventions. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2023.2177613

- Lundgren, E., & Eklöf, H. (2020). Within-item response processes as indicators of test-taking effort and motivation. Educational Research and Evaluation, 26(5–6), 275–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803611.2021.1963940

- Makel, M. C., Plucker, J. A., & Hegarty, B. (2012). Replications in psychology research. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(6), 537–542. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612460688

- Marsh, H. W., Hau, K.-T., Artelt, C., Baumert, J., & Peschar, J. L. (2006). OECD's brief self-report measure of educational psychology’s most useful affective constructs: Cross-cultural, psychometric comparisons across 25 countries. International Journal of Testing, 6(4), 311–360. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327574ijt0604_1

- McCoach, D. B., Gable, R. K., & Madura, J. P. (2013). Instrument development in the affective domain: school and corporate applications. Springer.

- McNeish, D. (2018). Thanks coefficient alpha, we’ll take it from here. Psychological Methods, 23(3), 412–433. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000144

- Messick, S. (1989). Validity. In R. L. Linn (Ed.), Educational measurement (3rd ed., pp. 13–103). MacMillan.

- Meyer, G. M., Marco-Pallarés, J., Boulinguez, P., & Sescousse, G. (2021). Electrophysiological underpinnings of reward processing: Are we exploiting the full potential of EEG? NeuroImage, 242, 118478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118478

- Murphy, P. K., & Alexander, P. A. (2000). A motivated exploration of motivation terminology. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 3–53. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1019

- Nicol, D. J., & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600572090

- Neisser, U., Boodoo, G., Bouchard, T. J., Jr., Boykin, A. W., Brody, N., Ceci, S. J., Halpern, D. E., Loehlin, J. C., Perloff, R., Sternberg, R. J., & Urbina, S. (1996). Intelligence: Knowns and unknowns. American Psychologist, 51(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.51.2.77

- Nieminen, J. H., & Carless, D. (2022). Feedback literacy: a critical review of an emerging concept. Higher Education, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00895-9

- Panadero, E., & Lipnevich, A. A. (2022). A review of feedback models and typologies: Towards an integrative model of feedback elements. Educational Research Review, 35, 100416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2021.100416

- Pat-El, R. J., Tillema, H., Segers, M., & Vedder, P. (2013). Validation of Assessment for Learning Questionnaires for teachers and students. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(Pt 1), 98–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.2011.02057.x

- Philips, D. C., & Burbules, N. C. (2000). Postpositivism and educational research. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Ramaprasad, A. (1983). On the definition of feedback. Behavioral Science, 28(1), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/bs.3830280103

- Richardson, J. T. E. (2005). Instruments for obtaining student feedback: A review of the literature. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 30(4), 387–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930500099193

- *Rui, Y., & Muthukrishnan, P. (2019). Growth mindset and students’ perception of their English Language teachers’ feedback as predictors of language proficiency of the EFL learners. Asian EFL Journal, 23(3), 32–60. https://www.asian-efl-journal.com/main-editions-new/2019-main-journal/volume-23-issue-3-2-2019/index.htm

- Schacter, D. L. (1999). The seven sins of memory: Insights from psychology and cognitive neuroscience. The American Psychologist, 54(3), 182–203. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.3.182

- Sirin, S. R. (2005). Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review of research. Review of Educational Research, 75(3), 417–453. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543075003417