Abstract

Recent fieldwork undertaken by the joint Finnish-Jordanian Tell Yaˁmoun Regional Archaeological Survey (TYRAS) in the northern part of the Jordanian plateau explored the unexcavated site of Tell al-Assara. An initial survey of the site and its surface pottery indicates that it was occupied for much of the 1st millennium BCE. The initial survey also found an inscribed Aramaic potsherd, which we present and analyse here. This analysis of the inscription builds both on digital techniques like photogrammetry and traditional philological approaches. Despite its brevity, the al-Assara inscription is an important new datum in the corpus of Transjordanian Iron Age texts and palaeography. It can be dated to the middle of the 1st millennium BCE and links Tell al-Assara to broader regional practices of writing and administration.

Exploration at Tell al-Assara

Tell al-Assara (تل العصارة /Tell al-ˁAṣṣāra) is in the northern part of the Jordanian plateau, approximately two kilometres west of the village of An-Nuayyimah and roughly 18 kilometres south of Irbid. This is the heart of the area covered by the Tell Yaˁmoun Regional Archaeological Survey (TYRAS), a joint Finnish-Jordanian archaeological project supported by the Academy of Finland’s Centre of Excellence in Ancient Near Eastern Empires and the Faculty of Archaeology and Anthropology at Yarmouk University. Tell al-Assara was discovered and explored during the first TYRAS survey season in spring 2022. It is a long and narrow tell, occupying a total surface area of approximately 5000 m2. The tell stretches across the entirety of a natural hilltop that runs in a north–south direction. It is surrounded by a massive ashlar wall. An oval-shaped depression in the north-eastern part of the tell may be the remains of a tower structure. The slopes of the tell and the flat area around it are also characterized by signs of occupation. There are traces of numerous retaining walls, which perhaps formed part of structures in the lower city ().

TYRAS focuses on collecting new data from understudied regions that served as buffer zones or marginal territories for the great Near Eastern empires of the 1st millennium BCE — notably the Neo-Assyrian, Neo-Babylonian and Persian empires. TYRAS studies these regions to better understand the relationships between interstitial zones, imperial heartlands and the apparatus of empire.

TYRAS has compiled a quantitative and qualitative record of archaeological features in its survey area, employing digital technologies like tablets and sport watches with inbuilt GPS (Lorenzon et al. Citation2023). It divides individual sites into series of rectangular blocs (transects) measuring approximately 100 × 25 metres. To enable surveyors to document all finds in a more limited area with greater accuracy, each transect is subdivided into five smaller rectangles of 100 × 5 metres.

The ceramic material collected by TYRAS at Tell al-Assara includes one sherd with traces of an inscription. Although Lorenzon et al. (Citation2023) offered a preliminary presentation of this find along with a tentative interpretation, the present contribution offers a formal, full, and substantially different analysis of the potsherd and its inscription. This analysis includes the application of digital methods.

Discovery and description of the inscribed potsherd

TYRAS divided the site of Tell al-Assara into 11 transects. These transects cover the top of the tell, its slopes and the flat ground around it. Each transect is 25 metres wide, but apart from at the top of the tell, the length of each transect varies according to the terrain. TYRAS collected, documented and analysed all visible surface pottery in the transects. Among the ceramic material collected from transect 8, located on the north-eastern side of the tell, an inscribed potsherd was identified and documented (). A preliminary reading of the survey pottery from Tell al-Assara indicates a single-period occupation of the site. Diagnostic pottery dates from the Early Iron Age to the Late Iron Age, with the possibility of some Hellenistic presence. This timespan covers most of the 1st millennium BCE, from its beginnings through to the end of the Persian period and a bit beyond (c. 200 BCE). Occupation appears to have been most intense towards the middle of the 1st millennium BCE. Mainly Iron Age I–II pottery was identified from the material found in transect 8 (for a detailed analysis of the pottery at Tell al-Assara, see Gheorghiade et al., Citationin prep).

Figure 2 Aerial photo of Tell al-Assara with the location of the transect of the inscribed potsherd marked with red (photograph by Rebecca Banks; courtesy of APAAME).

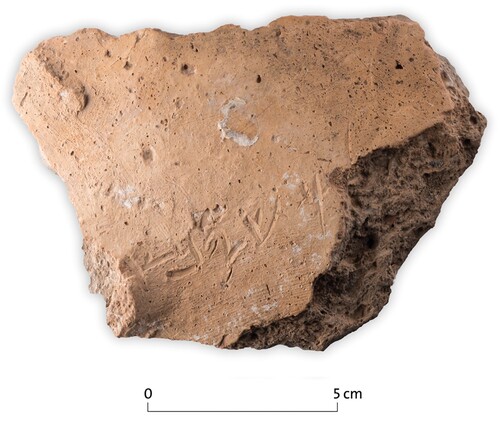

The inscribed potsherd presented in this article was part of a storage vessel. Its preserved dimensions are 10 cm × 8 cm and it is approximately 1 cm thick. The external face of the sherd bears a single line of text.

The sherd surface is light brown in colour. It was fired in a reduced environment, as demonstrated by the distinctive black discolouration visible in the profile. A macroscopic analysis of the fabric highlights the presence of medium–large cherts, quartzite and lime inclusions, all clearly visible in the profile. Numerous voids linked with the presence of organic tempering in the fabric are also evident; this is characteristic of the coarse Iron Age fabrics of this region.

The sherd belongs to an Iron Age closed vessel, as indicated by the preserved shoulder and initial part of the handle. These are similar to other regional Iron Age jars, such as the ones documented at Tall al-ˁUmayri, Deir ˁAlla and Tell Ḥisbān (Herr Citation2015a and Citation2015b).

The visible bump in the break suggests that the vessel is hand-made and coil-built. No wheel marks are visible, but the external surface presents traces of an orange slip, as well as parallel striations in different locations of the fragment. These indicate a final polishing conducted with a cloth. The thickness of the sherd suggests that the original vessel may have been large, although its exact size is impossible to approximate from the small body sherd.

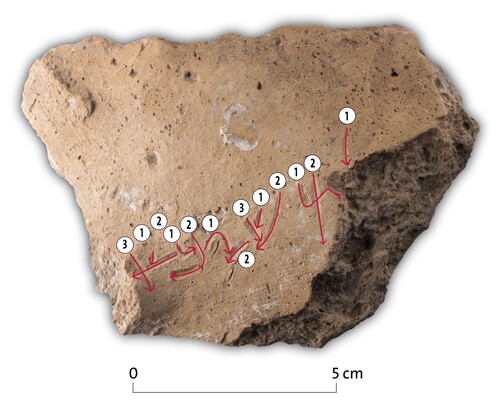

The inscription, which is approximately 5 cm long, was incised next to the location of a handle (). Based on the thickness and curvature of the sherd, it appears that this was one of the handles of a large, two-handled storage amphora. The signs of the inscription are approximately 10 mm wide and 10 mm high. The first sign (lamed) starts 8 mm above the other signs, but the rest are of the same height. The inscription was incised before firing, when the clay was still soft.

3D reconstruction as a tool in the interpretation of incised inscriptions

Ancient inscriptions on ceramic surfaces are often difficult to interpret. The challenges vary depending on whether inscriptions are written with ink or incised directly into the clay. In the case of incised inscriptions, damage to the ceramic surface can efface parts of an inscription and introduce new features that are liable to be mistaken for deliberate incisions. The present potsherd is no exception, including both breaks in some of the characters of the inscription and various supplementary marks on the writing surface. To overcome these challenges a 3D model of the sherd, using photogrammetry, was created. As well as contributing to our understanding of the vessel shape and manufacture, these techniques helped distinguish between incisions that were part of the inscription and unintended damage, including damage from the release of trapped air during firing of the vessel.

In recent years, 3D reconstruction has become a mainstay for recording and analysing archaeological artefacts and sites. This development is driven in part by technological advances and cost reductions that have made 3D reconstruction technologies available at a consumer-level price (Porter et al. Citation2016). Applying such low-cost techniques enabled the creation of a three-dimensional model suitable for scientific purposes, but also appropriate for public dissemination (Bonacchi Citation2012; Haukaas and Hodgetts Citation2016), facilitating the study of the inscription for those unable to examine the sherd in person. This was also useful for us, as the inscription was only subjected to formal analysis following the conclusion of the field season.

The simplicity, versatility and high-resolution end-product of photogrammetry give it an advantage over many other 3D reconstruction technologies, such as laser scanning (Plisson and Zotkina Citation2015). We therefore opted to produce our 3D reconstruction of the inscribed potsherd with photogrammetry, using the Agisoft Metashape Professional 2.0 software.

The set of images used to create the 3D model was created with a NIKON D810 camera coupled with a 60 mm micro-lens and fixed to a tripod. The sherd was propped against a support, illuminated with a soft overhead light and a weaker sidelight, and placed on a circular pedestal that was rotated on its axis between shots. After completing a full rotation, the sherd was flipped 180° and another series of photographs was shot, meaning that no part of the surface remained obscure. This method is favoured by artefact modellers, as it is quicker and less laborious to rotate the object compared to orbiting the camera around the artefact. The background, which remains static, is easily masked out in Metashape (Porter et al. Citation2016).

To match the re-orientation of the sherd, the 3D model was processed in two chunks. The maximum settings were used throughout the modelling process. The dense cloud was created with mild depth filtering to preserve small details in the incisions and on the surface of the sherd. The mesh was then created with interpolation enabled. At this point, the two chunks were merged. The resulting texture was produced with mosaic blending mode, using the images as source data and with hole filling enabled.

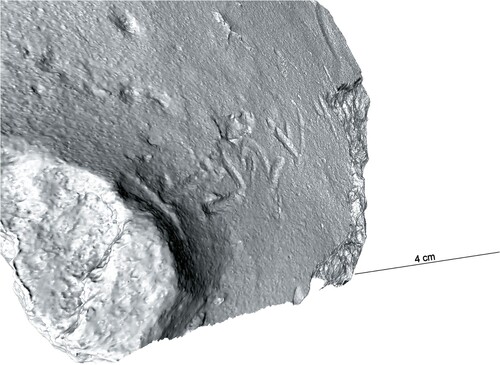

There was no single best projection for inspecting the model, as different projections brought out different details in the sherd. The uncoloured solid dense cloud most faithfully reproduced the topography of the sherd surface. The tiled model was negligibly better than the textured model for viewing inclusions and colouration. But the incisions of the inscription were best defined in the solid and shaded meshes. It was possible to reveal further details in the surface of the sherd and improve the readability of the inscription by importing the mesh into Meshlab and applying shaders to it ().

One of the main advantages of studying a 3D model of the sherd was the possibility of inspecting the incisions from otherwise impossible angles. In particular, a better understanding of the shapes and directionality of the incisions could be garnered by analysing them in profile view. In the physical sherd these profiles were obfuscated by the sherd body. It was observed that there were two general profiles for the incisions based on differences in the angles of their slopes and bases. Straight, downward incisions have pronounced V-shaped profiles, whereas the remaining incisions have more of a U-shape, with steep walls and a wider base (). These differences may reflect either the use of a writing implement with a different width compared to its height, or the alternating technique of the writer. Identifying the profiles of incisions helped to differentiate between deliberate incisions and unintentional damage. Our analysis also revealed differences in the degree to which the surface around the strokes was elevated because of the displacement of clay when the letters were incised. Such surface elevation was most pronounced at the end of the wide horizontal strokes, where the surface of the sherd itself curved outward, likely causing the writing implement to sink deeper into the clay ().

Although the 3D model helped make sense of the inscription, still images shot with sidelight were still the most effective in terms of sheer readability of the text. This demonstrates the continued utility of still photos. A focus stacked image of the sherd was produced to obtain a single, crisp, close-up image of the sherd for the purpose of displaying the inscription.

The al-Assara inscription

The surviving text of the al-Assara inscription consists of six individual signs. Three of the signs are fully preserved, and three only partially. There is a small space between the second and third signs. The signs are clearly recognizable as products of the tradition of sinistrograde abjad writing from the Levant in the 1st millennium BCE. The closely related scripts within this tradition were used to record different languages, but are especially closely associated with Northwest Semitic languages like Phoenician, Hebrew and Aramaic (Naveh Citation1997). In the region of Tell al-Assara, varieties of the script were used to record inscriptions in the Aramaic and Ammonite languages.

All the signs in the al-Assara inscription fit within the range of attested forms from Aramaic and Ammonite seals spanning roughly 650–350 BCE, but most closely resemble those of 6th and 5th century Aramaic seals (Herr Citation2014: 177). This dating aligns with the chronology of the pottery recovered at Tell al-Assara. The uninterrupted curvature of the signs of the al-Assara inscription indicates that they were incised in soft, unfired clay (). This explains why the signs resemble the incised forms attested on seals and Persian period lapidary inscriptions (Lemaire Citation2014: 245) more closely than the cursive ink forms attested on ostraca (Lemaire Citation2014: 247), including the roughly contemporaneous examples from nearby Tell Ḥisbān (Cross Citation1975; Citation2003) and the temporally and spatially more distant example from Tall Jawa (Dion Citation2002). The sign forms on the al-Assara inscription also align quite closely with those attested in Aramaic stamp impressions on 6th century bricks from Babylon (Sass and Marzahn Citation2010: 154–55).

We interpret the six signs of the sinistrograde inscription from Tell al-Assara as follows:Footnote1

l m š z b ˀ/t

l: Although the first sign is only partially visible, it is nevertheless clearly recognizable as a lamed. The surviving part of the lamed extends above the other signs in the inscription and betrays the characteristic curvature that culminates in a hook.

m: The second sign is mostly preserved. It consists of two strokes and forms a recognizable mem. Although the rightmost part of the sign is broken off, what remains aligns perfectly with mems preserved elsewhere (e.g., in CAI Citation2019: 136).

š: The third sign is fully preserved and is an unmistakeable shin. The form of the sign corresponds to those attested from the 6th century onwards.

z: The fourth sign is fully preserved. Despite the curvature of its top part, the sign fits well alongside the range of attested forms for the letter zayin (for parallels, see Lemaire Citation2014: 242–43 and 245–46).

b: The fifth sign is fully preserved and fits securely within the range of attested forms for the letter bet. It matches a roughly contemporaneous bet inscribed on a ceramic vessel from nearby Tall al-ˁUmayri. The bet from Tall al-ˁUmayri was likewise inscribed prior to firing the vessel (Herr Citation2000: 250–51).

ˀ/t: The sixth sign is largely preserved. It consists of two perpendicular strokes. There is also a small, diagonal incision in the upper right quadrant of the resulting form, which connects with the rest of the sign near the intersection of the two major strokes. This incision is critical to interpreting the sign. If it is intentional, the sign must be read as an aleph. Parallels for such an aleph are attested both in seals (e.g., WSS Citation1997: 885 and imperfectly in Herr Citation1997: 325, fig. 16.4) and in Persian period Aramaic lapidary inscriptions (Lemaire Citation2014: 245). This reading would push the dating of the inscription into the 5th century BCE. If the diagonal incision is the unintentional result of damage to the ceramic vessel, then the sign consists of only the two perpendicular strokes. This combination resembles one of the attested forms of the letter taw, albeit earlier in date than some of the other sign forms in the inscription and more commonly oriented at an angle. The taw in some Ammonite and Aramaic seals from the 8th and 7th centuries BCE consists of the same two perpendicular strokes (e.g., in WSS Citation1997: 756 and 794), as does the taw in at least one similarly dated inscribed potsherd from Jerusalem (IP 24 in Shoham Citation2000: 22). The horizontal stroke of the sign is exaggerated in the al-Assara inscription, impinging on the preceding bet. The sign is incised at an awkward angle, precisely where the handle begins to rise out of the body of the vessel. This placement could explain the stroke’s exaggerated length. As the form of the aleph is more consistent with the palaeography of the other signs in the inscription than that of the taw, we regard it as the primary reading.

Interpretation of the al-Assara inscription

The interpretation of the al-Assara inscription depends on whether any signs are missing before or after the surviving sequence. The inscription extends to the beginning of the handle of the ceramic vessel. It is standard practice to write inscriptions adjacent to the handles of ceramic vessels. But such writing does not normally extend onto the handles themselves, as their slant and shape is not well suited to the purpose. It is therefore unlikely that the text continued beyond the last surviving sign. As the inscription was incised in the ceramic vessel before firing, we can rule out that the text was written on an ostracon (Caputo Citation2020). Unlike ostraca, which could be used to record longer texts, inscriptions on ceramic vessels from the Levant in the middle of the 1st millennium BCE are all exceedingly brief. They can indicate the content of the vessel, its volume, and most commonly the name of its proprietor or consignee. Abstract terms are almost entirely absent from this corpus (Klingbeil Citation1997: 45). These inscriptions very frequently begin with the letter lamed. This letter serves as a preposition indicating the vessel’s proprietor or consignee. The first surviving sign in the al-Assara inscription is a lamed. There is no indication of any signs preceding it. Given that the surviving text corresponds to the overall length that might be expected for such an inscription and makes good sense, we postulate that there were no signs preceding the lamed. This would mean that the surviving inscription is complete, notwithstanding the damage to three of the signs.

A further issue in the interpretation of the inscription pertains to the small space between the mem and the shin. The use of space to separate words is not standard in comparable short inscriptions (Demsky Citation2007: 71). These tend to be written in scriptio continua. Dividing the text of the al-Assara inscription into separate words based on the space does not yield good sense. The space is also minimal and easily attributable to a scribal slip. Accordingly, we do not attach semantic value to the space.

This leaves three plausible readings of the inscription that do not require a reconstruction of the missing signs. The first reading assumes that the final sign is an aleph, whereas the other two readings regard it as a taw. Reading an aleph is both better suited to the chronological horizon of the other sign forms and poses the fewest interpretative challenges. It should be regarded as the default reading.

Reading with an aleph

In this reading, the text of the inscription consists of a preposition and a proper noun. The initial lamed is the preposition, standard to Northwest Semitic languages as a group. It is attached to a succeeding proper noun that comprises the other five signs in the inscription. This proper noun is the name of the proprietor or consignee of the vessel’s contents:

lmšzbˀ

for/of mšzbˀ (Məšēzabā/Mesheyzaba)

There are plentiful parallels for this interpretation. Writing on ceramic vessels in the southern Levant around the middle of the 1st millennium BCE comes in two forms. Text is either impressed on vessels as part of a seal or written directly onto the vessel. In both cases, it is common for inscriptions on ceramic vessels to begin with a lamed followed by the vessel’s proprietor or consignee. This is especially well documented for the abundant vessels from the area of Judah impressed with seals (Lipschits, Sergi and Koch Citation2010; Citation2011; Lipschits and Vanderhooft Citation2011;). Many of these seal impressions bear the text lmlk (for/of the king), while others bear the preposition lamed followed by a personal name, or a personal name by itself. Seal impressions are ordinarily stamped directly onto the handle of the vessels, adjacent to the location of the al-Assara inscription. The same patterns apply when text is inscribed directly on ceramic vessels without the use of seals. Dozens of inscribed potsherds from Jerusalem across the 1st millennium BCE, for instance, feature the pattern lamed followed by a personal name (Naveh Citation2000; Shoham Citation2000). These inscriptions can be written in ink or incised either before or after firing. They are usually positioned by the handles of the vessels, just like the al-Assara inscription. The longevity and consistency of these practices demonstrate continuity both in the character and in the placement of inscriptions on ceramic vessels.

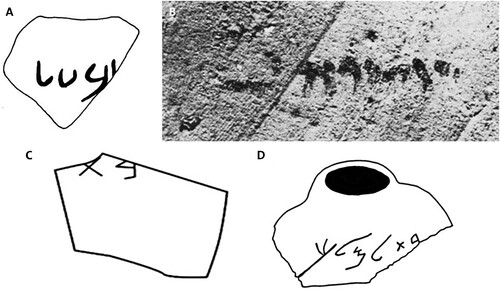

An inscribed potsherd from Tall al-ˁUmayri offers an especially close parallel to the al-Assara inscription in time, space and character (Herr Citation2000: 250–51). Larry G. Herr dates it to the 6th century BCE, within the palaeographic window for the al-Assara inscription. Tall al-ˁUmayri is approximately 70 km to the south of Tell al-Assara. Both are situated on the Jordanian plateau. Like the al-Assara inscription, the sherd from Tall al-ˁUmayri was incised prior to firing the vessel. The text is also similar. It reads simply lbˁl (for/of Baˁal). We thus have the same basic text, a lamed followed by a name. The palaeography also matches. The two letters that appear on both the Tall al-ˁUmayri and the Tell al-Assara sherds, namely lamed and bet, correspond precisely (A).

Figure 8 A. Inscribed sherd from Tall al-ˁUmayri, Jordan. The bet and lamed of the inscription resemble those in the al-Assara inscription (after Herr Citation2000: 250); B. Inscribed sherd from Tell al-Mazār (detail from Yassine and Teixidor Citation1986: 46, fig. 1); C. Tell Beit Mirsim sherd with bt inscription. The inscription was incised after firing (after Albright Citation1943: pl. 60); D. Inscription reading btlmlk from Lachish, stratum III (redrawn from Tufnell Citation1953: fig. 7066).

The name mšzbˀ is a participial form of the Aramaic šap̄ˁel root šyzb/šwzb, meaning ‘to save, deliver’. This root is likely borrowed from the Akkadian language, but is amply attested in Aramaic (Butts Citation2018: 122; Kaufman Citation1974: 105). The masculine participial form mšzb is a common element in Akkadian names, where it features in combination with divine names as mušēzib (one who saves/saviour). In Aramaic sources, mšzb features either with or without a divine name. Alongside a divine name, mšzb is best understood as the active participial məšēzib, producing the name ‘the god x is saviour’. Without a divine name, it makes more sense to read mšzb as the passive participial form məšēzab, meaning ‘saved one’. In the al-Assara inscription, an aleph follows the name mšzb. This aleph marks the Aramaic determined state. Its presence demonstrates that the name mšzbˀ/məšēzabā should be regarded as unequivocally Aramaic, rather than as Ammonite or Akkadian. The name can be translated as ‘the saved one’.

There are numerous parallels for this name. The best of these is preserved in the 4th century BCE ostracon A50.1 from Idumea (Porten and Yardeni Citation2016: 319). This ostracon attests the name mšyzbˀ. Outside of its plene spelling, the name is identical with that of the al-Assara inscription. The name element mšzb surfaces in many other texts, too. An Aramaic epigraph on a 5th century cuneiform tablet from Babylonia preserves the full name mšzb (BE 10, 87, or no. 180 in Streck Citation2017: 178). The element mšzb appears in a 5th century Aramaic fragment from Elephantine as part of the name mšzbnbw (Məšēzib-Nabû), ‘the god Nabû is saviour’ (TAD Citation1999: D3.39). The similar name šzbˀl (Šēzib-ˀEl), ‘God (El) saved’, is attested in an Aramaic text from Elephantine (TAD Citation1993: C3.13:56a). Here the verb is conjugated in the perfect rather than as a participle. The name mšyzbˀl (Məšēzib-ˀEl),Footnote2 ‘God (El) is saviour’, appears three times in the book of Nehemiah (Neh. 3:4, 10:22, 11:24). As well as an exact and roughly contemporaneous parallel, there are thus numerous comparanda for a name like mšzb — both by itself and in combination with a divine name, and both in Akkadian and in Aramaic.

Reading with a taw

If we read the final sign as a taw, two interpretations are possible. The first consists of the preposition lamed attached to a proper noun indicating the proprietor or consignee of the vessel’s contents. This is followed by a noun quantifying the otherwise unspecified liquid held within the vessel:

lmšz bt

A bath-measure for/of mšz

In this reading, the al-Assara inscription assigns the vessel on which it is inscribed to mšz. In line with the majority of such inscriptions, mšz would be a personal name. This conclusion is reinforced by the fact that the letters mšz do not spell out a recognizable office or institution in any of the languages known from the area of Tell al-Assara. The name mšz is not familiar from the onomasticon of other nearby, contemporary inscriptions. It is also not recognizably Semitic. We cannot offer an interpretation of its meaning or origin. The letter combination mšz is, however, attested in abjad script as a likely personal name in Persepolis Fortification tablet Fort. 1916B-101 (Azzoni and Stolper Citation2015: 56–57). Azzoni and Stolper tentatively suggest that the name mšz is of Persian derivation. The similar name Mešizza is recorded in Persepolis Fortification tablet PF 1730 (Hallock Citation1969: 474), but written in cuneiform (me-ši-iz-za). If mšz is indeed a personal name, all we can say for now is that it is unusual for its time and place, and perhaps indicative of broader patterns of interaction and mobility. It should be stressed however, that there are many unique and otherwise unusual names in the onomastic evidence from the Levant in the 1st millennium BCE.

The sequence lmšz (for/of mšz) is followed by the noun bt. This noun is familiar from many of the same inscriptions that attest the formula lamed followed by the name of the proprietor or consignee. The bt (or bath) is a unit of liquid measurement, estimated to be around 20 litres (Lipschits, Koch, Shaus and Guil Citation2010). This measure appears written out on ceramic vessels from across the southern Levant in the 1st millennium BCE (Kletter Citation2009; Citation2014). It is written either as bt or indicated in shorthand with a bet and the appropriate number. The bath-measure also features prominently in several books of the Hebrew Bible.

Although they date to roughly 300 BCE, two inscriptions on ceramic vessels from Tell al-Mazār in the Jordan Valley offer a local comparandum to the al-Assara sherd. One bears a personal name followed by what appears to be a large bet — interpreted as shorthand for a bath-measure (no. 1 in Yassine and Teixidor Citation1986: 45) (B). Like the al-Assara sherd, this fragment connects to the handle of the original vessel. A second inscription from Tell al-Mazār records both a personal name and probably a quantity of wine measured by the bath (no. 2 in Yassine and Teixidor Citation1986: 45–47). The inscriptions from Tell al-Mazār are written in ink rather than incised directly into the clay. They nevertheless represent an excellent parallel for this interpretation of the al-Assara inscription.

Further comparanda come from multiple sites across the southern Levant. At Tell Beit Mirsim, excavators found two separate inscribed potsherds (Albright Citation1929: 15; Citation1943: 58–59). One bears only the text bt, interpreted as a reference to the bath-measure. The other bears the text lˁz[yw], reconstructed as ‘for/of ˁUzziyaw’, but plausibly referring to a different personal name starting with the consonants ˁz. Both inscriptions are dated palaeographically and contextually to the 7th century BCE. At Lachish, the upper part of a storage jar was inscribed before firing with the words bt lmlk, ‘a bath-measure for/of the king’ (Tufnell Citation1953: 356–57) ( C–D).

All elements in the reading ‘a bath-measure for/of mšz’ are thus amply attested, both separately and together, in parallel evidence from the southern Levant in the middle of the 1st millennium BCE.

An alternative interpretation of the al-Assara inscription reads the signs following the lamed together as a single name:

lmšzbt

for/of mšzbt

In this interpretation, mšzbt is again a participial form of the Aramaic šap̄ˁel root šyzb/šwzb. The trouble lies with the final taw. This taw marks the name as feminine. Although no feminine forms of the name mšzb are currently known in Aramaic sources, this absence is not very revealing given that the bulk of surviving names are masculine. Even so, a feminine name is itself not unusual. The onomastic record of inscriptions on ceramic vessels includes a substantial minority of such names. However, in Aramaic we would expect the singular feminine participial form of the root šyzb/šwzb to conclude with a hey rather than a taw. The most intuitive way to make sense of the taw is to argue that the participial form is in the determined state. In that case, the name is written unusually without a succeeding aleph, or the aleph of the determined state is lost in the break. It is also possible that the name is in the construct form, with a succeeding divine name lost after the taw. Still another possibility is that the name here retains features of its Akkadian origin. In Akkadian, the form of the feminine Š-stem participle is mušēzibtu. If this is the base pronunciation of the name used here, then it is possible that the short final vowel was simply not indicated in writing or lost in the break. Another option is that the name was rendered in the absolute form as mušēzibat.

There are still other ways to interpret the al-Assara inscription, but these require the inscription to continue beyond the taw. One would read bt not as the bath-measure, but as the identically written Ammonite word for daughter. This would mark the inscription as Ammonite rather than Aramaic, as the Aramaic word for daughter is brt rather than bt. It would also require a now lost name to follow the word bt. Another option reads the masculine name mšzb, followed by further text that begins with the letter taw. Because these readings require extensive textual reconstruction, we do not pursue them here.

The al-Assara inscription in context

For now, the al-Assara inscription is the only inscribed artefact known from ancient Tell al-Assara. The text is very short, simply designating the proprietor or consignee of the vessel on which it was incised. The best reading of the intended name is the Aramaic mšzbˀ/məšēzabā. Despite the brevity of the al-Assara inscription, it nevertheless sheds substantial light on the nature of the site in the middle of the 1st millennium BCE. The script and character of the inscription indicate that Tell al-Assara was integrated into broader regional patterns of writing and literacy. There were individuals at Tell al-Assara who were familiar with these patterns. They were able to both read and produce text according to regional standards. These individuals knew what kinds of inscriptions were customary for ceramic vessels. They knew where on the vessel such inscriptions ought to be written. And they used writing for mundane purposes like marking ceramic vessels. The fact that ordinary ceramic vessels were marked with writing in turn suggests that there were developed administrative practices at Tell al-Assara, including separate spheres of authority and proprietorship. This is consistent with the traces of major fortifications and significant stone structures at the site, along with the widespread presence of Iron Age pottery. Tell al-Assara was likely a locally significant centre of production, consumption and redistribution. It was part of broader regional networks of interaction and exchange. These networks were in turn tied to the Mesopotamian and Persian imperial frameworks that dominated the Middle East for most of the 1st millennium BCE.

Acknowledgements

We extend our thanks to all the TYRAS team members who participated in the first season: Antti Lahelma, Stefan Smith, Benjamín Cutillas-Victoria, Elisabeth Holmqvist, Maija Holappa, Anu Ketonen, Maria Ronkainen, Jasmin Ruotsalainen, Paula Kouki, Päivi Miettunen, Maher Tarboush, Hussein Al-Shababha, Ahmed al-Shorman, Heba Abu-Dalou and Mousa Serbel. We are extremely grateful to Maija Holappa for the maps she produced during the first and second seasons of fieldwork, and for her work in producing the figures for this article. We would also like to extend our gratitude to Omar A. Alghul for sharing his expertise and comments. Further thanks are due to the Department of Antiquities of Jordan, and in particular to HE Dr Fadi Balawi and Dr Aktham Oweidi for their help and support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The initial report of the discovery of the Tell al-Assara inscription proposed that the sign interpreted here as zayin should be read instead as an aleph, while suggesting various readings for the sign interpreted here as aleph or taw.

2 In the Masoretic tradition, the vowel between the z and the b is instead a pataḥ.

References

- Albright, W. F. 1929. The American excavations at Tell-Beit Mirsim. Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 47: 1–17.

- Albright, W. F. 1943. The Excavation of Tell Beit Mirsim, Vol. 3: The Iron Age. The Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research 21/22. New Haven: American Schools of Oriental Research.

- Azzoni, A. and Stolper, M. 2015. From the Persepolis Fortification Archive Project, 5: the Aramaic epigraph Ns(y)h on Elamite Persepolis Fortification Documents. Achaemenid Research on Texts and Archaeology (ARTA) 004: 1–88.

- BE 10 = Clay, A. T. 1904. Business Documents of Murashû Sons of Nippur Dated in the Reign of Darius II. (424–404 BC). The Babylonian Expedition of The University of Pennsylvania, Series A: Cuneiform Texts. Volume X. Philadelphia: The Department of Archaeology and Paleontology of the University of Pennsylvania.

- Bonacchi, C. (ed.). 2012. Archaeology and Digital Communication. Towards Strategies of Public Engagement. London: Archetype Publications.

- Butts, A. M. 2018. The Aramaic Šap̄ˁel in its Semitic context. Aramaic Studies 16(2): 117–43.

- CAI = Aufrecht, W. E. 2019. A Corpus of Ammonite Inscriptions, Second Edition. University Park, PA: Eisenbrauns.

- Caputo, C. 2020. Pottery sherds for writing: an overview of the practice. In, Caputo, C. and Lougovaya, J. (eds), Using Ostraca in the Ancient World: New Discoveries and Methodologies: 31–58. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Cross, F. M. 1975. Ammonite ostraca from Heshbon: Heshbon Ostraca IV–VIII. Andrews University Seminary Studies (AUSS) 13(1): 1–20.

- Cross, F. M. 2003. Ammonite ostraca from Tell Ḥisbān. In, Cross, F.M. (ed.), Leaves from an Epigrapher’s Notebook: Collected Papers in Hebrew and West Semitic Palaeography and Epigraphy: 70–94. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns.

- Demsky, A. 2007. Reading northwest Semitic inscriptions. Near Eastern Archaeology 70(2): 68–74.

- Dion, P-E. 2002. The Ostracon from Building 800. In, Daviau, P. M. M., Excavations at Tall Jawa, Jordan. Vol II: The Iron Age Artefacts: 268–72. Leiden: Brill.

- Gheorghiade, P., Lorenzon, M., Reinikainen, S., Smith, S. L., Tarboush, M., Miettunen, P., Kouki, P. and Lahelma, A. In prep. Connecting and disconnecting zones of interaction in northern Jordan. Journal of Archaeological Research.

- Hallock, R. T. 1969. Persepolis Fortification Tablets. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Haukaas, C. and Hodgetts, L. M. 2016. The untapped potential of low-cost photogrammetry in community-based archaeology: a case study from Banks Island, Arctic Canada. Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage 3(1): 40–56.

- Herr, L. G. 1997. Epigraphic finds from Tall al-ˁUmayri during the 1989 season. In, Herr, L. G., Geraty, L. T., LaBianca, Ø. S. and Younker, R. W. (eds), Madaba Plains Project 3: The 1989 Season at Tell el-ˁUmeiri and Vicinity and Subsequent Studies: 323–30. Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press.

- Herr, L. G. 2000. The inscriptions. In, Herr, L. G., Clark, D. R., Geraty, L. T., Younker, R. W. and LaBianca, Ø. S. (eds), Madaba Plains Project 4: The 1992 Season at Tall al-ˁUmayri and Subsequent Studies: 248–51. Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press.

- Herr, L. G. 2014. Aramaic and Ammonite seal scripts. In, Hackett, J. A. and Aufrecht, W. E. (eds), An Eye for Form: Epigraphic Essays in Honor of Frank Moore Cross: 175–86. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Herr, L. G. 2015a. Iron Age I: Transjordan. In, Gitin, S. (ed.), The Ancient Pottery of Israel and Its Neighbors from the Iron Age through the Hellenistic Period, Vol. 1: 97–114. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

- Herr, L. G. 2015b. Iron Age IIA–B: Transjordan. In, Gitin, S. (ed.), The Ancient Pottery of Israel and Its Neighbors from the Iron Age through the Hellenistic Period, Vol. 2: 281–300. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

- Kaufman, S. 1974. The Akkadian Influences on Aramaic. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Kletter, R. 2009. Comment: computational intelligence, Lmlk storage jars and the bath unit in Iron Age Judah. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 16: 357–65.

- Kletter, R. 2014. Vessels and measures: the biblical liquid capacity. Israel Exploration Journal 64: 22–37.

- Klingbeil, G. A. 1997. A semantic analysis of Aramaic ostraca of Syria-Palestine during the Persian period. Andrews University Seminary Studies 35(1): 33–46.

- Lemaire, A. 2014. Scripts of Post-Iron Age Aramaic inscriptions and ostraca. In, Hackett, J. A. and Aufrecht, W. E. (eds), An Eye for Form: Epigraphic Essays in Honor of Frank Moore Cross: 235–52. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Lipschits, O., Koch, I., Shaus, A. and Guil, S. 2010. The enigma of the biblical bath, and the system of liquid volume measurement during the First Temple period. Ugarit-Forschungen 42: 453–78.

- Lipschits, O., Sergi, O. and Koch, I. 2010. Royal Judahite jar handles: reconsidering the chronology of the lmlk stamp impressions. Tel Aviv 37: 3–32.

- Lipschits, O., Sergi, O. and Koch, I. 2011. Judahite stamped and incised jar handles: a tool for studying the history of Late Monarchic Judah. Tel Aviv 38: 5–41.

- Lipschits, O. and Vanderhooft, D. S. 2011. The Yehud Stamp Impressions: A Corpus of Inscribed Impressions from the Persian and Hellenistic Periods in Judah. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns.

- Lorenzon, M., Lahelma, A., Tarboush, M., Holmqvist, E., Daems, D., Kautonen, S., Töyräänvuori, J., Smith, S. L., Cutillas-Victoria, B., Holappa, M. and Al-Sababha, H. 2023. Tell it like it is: discoveries from a new survey of the northern Jordanian plateau. Near Eastern Archaeology 86(1): 16–27.

- Naveh, J. 1997. The Early History of the Alphabet: An Introduction to West Semitic Epigraphy and Palaeography. 2nd edition. Jerusalem: The Magness Press.

- Naveh, J. 2000. Hebrew and Aramaic inscriptions. In, Ariel, D. T. (ed.), Excavations at the City of David 1978–1985, Vol. 6: Inscriptions: 1–14. Qedem 41. Jerusalem: The Institute of Archaeology, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- Plisson, H. and Zotkina, L. V. 2015. From 2D to 3D at macro- and microscopic scale in rock art studies. Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage 2: 102–19.

- Porten, B. and Yardeni, A. 2016. Textbook of Aramaic Ostraca from Idumea, Volume 2. Dossiers 11–50: 263 Commodity Chits. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- Porter, S. T., Roussel, M. and Soressi, M. 2016. A simple photogrammetry rig for the reliable creation of 3D artifact models in the field lithic examples from the Early Upper Paleolithic sequence of Les Cottés (France). Advances in Archaeological Practice 4(1): 71–86.

- Sass, B. and Marzahn, J. 2010. Aramaic and Figural Stamp Impressions on Bricks of the Sixth Century BC from Babylon. WVDOG 127. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Shoham, Y. 2000. Inscribed pottery. In, Ariel, D. T. (ed.), Excavations at the City of David 1978–1985, Vol. 6: Inscriptions: 17–25. Qedem 41. Jerusalem: The Institute of Archaeology, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- Streck, M. P. 2017. Late Babylonian in Aramaic epigraphs on cuneiform tablets. In, Berlejung, A., Maier, A. M. and Schüle, A. (eds), Wandering Arameans: Arameans Outside Syria, Textual and Archaeological Perspectives: 169–94. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- TAD C = Porten, B., and Yardeni, A. 1993. Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt, Vol. 3: Literature, Accounts, Lists. Newly Copied, Edited and Translated into Hebrew and English. Jerusalem: The Hebrew University, Department of the History of the Jewish People.

- TAD D = Porten, B. and Yardeni, A. 1999. Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt, Vol. 4: Ostraca and Assorted Inscriptions. Newly Copied, Edited and Translated into Hebrew and English. Jerusalem: The Hebrew University, Department of the History of the Jewish People.

- Tufnell, O. 1953. Lachish III (Tell ed-Duweir): The Iron Age. London: Oxford University Press.

- WSS = Avigad, N. and Sass, B. 1997. Corpus of West Semitic Stamp Seals. Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- Yassine, K. and Teixidor, J. 1986. Ammonite and Aramaic inscriptions from Tell El-Mazar in Jordan. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 264: 45–50.