Abstract

Brand placements are omnipresent in video games. However, when and how they influence players’ brand attitudes is still insufficiently understood. Whereas previous research argued that positive affect transfers from the game to the placed brands and elevates brand attitudes, we propose and test that players form associations of the placed brands with specific attributes depending on the specific placement context. In a 2 × 2 within-subjects experiment with a third-person adventure game (N = 76), we strategically placed brands alongside positive versus negative in-game experiences by letting players collect items, conveying either speed or healthiness as an attribute. Brand attitudes became more positive if brands were paired with positive in-game experiences, irrespective of the specific attribute. However, brands also became associated with the distinct attributes they were paired with. These associations mediated the effects of the placement valence on brand attitudes, depending on which attribute was conveyed in the in-game experience. Our findings suggest that positive brand placement effects on brand attitudes go beyond a direct affect transfer but also arise from associations with specific attributes. Our study offers important insights into brand attitude formation from in-game advertising and valuable suggestions on effective brand placement.

With over 3.5 billion players worldwide, video games have become the entertainment media of the twenty-first century. Nowadays, the global gaming market is the highest-grossing entertainment industry, with over $150 billion in 2020, surpassing even the music and movie industries (Shaw et al. Citation2020). Marketers recognize this trend and advertise brands and products by placing them in video games. Such brand placements, “paid inclusion[s] of branded products or brand identifiers through audio and/or visual means within mass media” (Karrh Citation1998, 33), are nowadays widely used in video games and generate a market value of more than $6.71 billion (Vantage Market Research Citation2022). For example, in the critically appraised adventure Death Stranding, the player can consume Monster Energy drinks to replenish stamina. As another example, in racing games such as Forza Horizon, players drive cars from various real brands, giving players a first impression of how it feels to drive the respective car. Brand placements in video games can come across in various shapes, ranging from mere brand logos placed on banner ads to so-called advergames explicitly designed to advertise a brand (Terlutter and Capella Citation2013; Ghosh, Sreejesh, and Dwivedi Citation2022).Footnote1

Due to this increasing popularity of in-game placements, the scientific community has also become interested in them. Most earlier research studied explicit/implicit brand memory for embedded brands (for reviews, see Guo et al. Citation2019; Nelson and Waiguny Citation2012; Terlutter and Capella Citation2013; Yoon Citation2019). From a business perspective, however, a successful recollection of a brand name is not sufficient; the brand should also be liked to influence purchase decisions (see Vogel and Wänke Citation2016). Accordingly, in the last decade, more research has studied the effects of brand placements on brand attitudes. A brand attitude is the summary internal evaluation of a brand (Spears and Singh Citation2004). First meta-analytical evidence indeed suggests a small positive effect of in-game placements on brand attitudes (Babin et al. Citation2021; van Berlo, van Reijmersdal, and Eisend Citation2021). However, the same meta-analyses show much unexplained heterogeneity in the effects, suggesting that there is still much to learn about how in-game placements influence brand attitudes.

In the present research, we want to address this issue and provide a new perspective on when and why in-game brand placements lead to more favorable brand attitudes. We propose and empirically show that brands become associated with specific attributes and that these brand-attribute associations drive changes in brand attitudes.

Brand Attitudes, Affect Transfer, and Attribute Conditioning

A central rationale in previous research has been that video games create a pleasant experience and that the resulting positive affect transfers to the brands placed in the games (e.g., Dardis et al. Citation2016; Ghosh, Sreejesh, and Dwivedi Citation2022; Redondo Citation2012; Vermeir et al. Citation2014; Waiguny, Nelson, and Marko Citation2013; Wise et al. Citation2008). Some researchers conceptualize this affect transfer as an instantiation of evaluative conditioning (e.g., Waiguny, Nelson, and Marko Citation2013; Ingendahl et al. Citation2023; Redondo Citation2012). Evaluative conditioning is the change in the liking of a neutral stimulus (e.g., a brand) due to its pairing with other positive/negative stimuli (Hofmann et al. Citation2010; Landwehr and Eckmann Citation2020; Sweldens, Van Osselaer, and Janiszewski Citation2010). In the domain of in-game placements, previous research has proposed that either the game itself or more fine-grained experiences within the game (e.g., a pleasant scene) may serve as positive stimuli, which are paired with the placed brand and thus lead to more positive attitudes (e.g., Waiguny, Nelson, and Marko Citation2013; Ingendahl et al. Citation2023).

However, this perspective neglects that positive in-game experiences are manifold. For example, the brand Monster Energy is repeatedly paired in Death Stranding with the positive experience of receiving a health boost. In contrast, the brand Ferrari is repeatedly paired in Forza Horizon with the positive experience of driving at high speed. Although both experiences arguably elicit positive affect, they also convey specific attributes—in this case, healthiness (Monster Energy) and speed (Ferrari). Thus, Monster Energy and Ferrari might also become associated with these distinct positive attributes (Du Plessis, D’Hooge, and Sweldens Citation2023; Kim, Allen, and Kardes Citation1996).

Such an effect is called attribute conditioning, defined as the changed assessment of initially neutral stimuli’s attributes due to repeated pairing with stimuli possessing these attributes (Unkelbach and Förderer Citation2018). It is a key effect in brand management because forming associations between the brand and specific attributes is central to the brand image and a crucial goal of advertising (Eckmann et al. Citation2021). Although conceptually related to evaluative conditioning, the major difference between attribute and evaluative conditioning is that attribute conditioning refers to the change in a specific attribute, and evaluative conditioning refers to the change in affective valence.

Outside the in-game advertising literature, some findings already indicate that changes in brand attitudes sometimes actually reflect changes in specific stimulus attributes (Förderer and Unkelbach Citation2011; Kim, Allen, and Kardes Citation1996). For example, watching a commercial showing a shoe brand with a famous athlete may lead to more positive brand attitudes, but indirectly through an association between the brand and the positive attribute “fast” (Kim, Allen, and Kardes Citation1996). In a recent review on brand-association formation, Du Plessis, D’Hooge, and Sweldens (Citation2023) discuss that brand-attitude research cannot effectively distinguish between affect transfer and brand-attribute associations when assessing only global brand liking measures, as done in previous research on in-game placements.

We propose that the same principle operates for brand placements in video games. A brand might become more positive after being placed alongside positive in-game experiences, supposedly the result of positive affect being transferred to the brand. However, this change in attitudes might also be due to a specific attribute that becomes associated with the placed brand. For example, players may develop more positive brand attitudes for Monster Energy and Ferrari not due to their placement alongside positive in-game experiences, but because these brands become associated with distinct positive attributes—healthiness and speed. This is important, as it suggests that brand-attitude change may not only reflect an affect transfer but also learned associations with specific attributes. Furthermore, it suggests that previous research might have underestimated the potential of in-game placements, as they not only change the global liking of a brand but also create distinct associations with specific positive attributes. This is what we investigated in the present research.

The Present Research

In a single experiment, we tested whether brands placed in video games can become more or less positive through pairings with positive or negative in-game experiences carrying specific attributes. For that purpose, players navigated through a third-person adventure game containing brand placements. Crucially, we systematically manipulated the specific in-game experiences alongside the placements by letting players collect items that affected the gameplay. For some brands, the in-game experience was positive (i.e., the item increased the player’s chances of success); for others, it was negative (i.e., the item decreased the player’s chances of success). Also, for some brands, the in-game experience was related to the attribute “healthiness” (the item influenced the player’s health); for others, it was related to “speed” (the item influenced the player’s speed). Afterward, we assessed brand attitudes and let participants judge the brands on both attributes.

We expected that brand attitudes should increase (decrease) if the brands are paired with positive (negative) in-game experiences (Hypothesis 1). However, we also expected that brands would become associated with specific attributes depending on their placement context (Hypothesis 2). Specifically, brands paired with positive (negative) speed-related in-game experiences should increase (decrease) in perceived speed (Hypothesis 2a). In contrast, brands paired with positive (negative) healthiness-related in-game experiences should increase (decrease) in perceived healthiness (Hypothesis 2b). Last, we expected that perceived speed and healthiness are both positively related to brand attitudes (Hypotheses 3a and 3b). In combination, these predictions lead to a moderated mediation hypothesis (Hypothesis 4): The increase/decrease in brand attitudes as described in Hypothesis 1 should be mediated by perceived speed and healthiness, but qualified by the specific attribute. That is, if the in-game experience is related to speed, then the change in brand attitudes should be mediated particularly by perceived speed (Hypothesis 4a). If the in-game experience is related to healthiness, then the change in brand attitudes should be mediated particularly by perceived healthiness (Hypothesis 4b).

Method

Design & Sample

Our experiment had a 2(conditioned valence: positive vs. negative) × 2(conditioned attribute: healthiness vs. speed) within-subjects design. We based our sample sizes on an a priori power analysis in GPower (Faul et al. Citation2007). For a within-subjects effect of d = 0.35 (based on Ingendahl et al. Citation2023), the required sample size was N = 67 for 80% power. We set the goal to collect data from at least 70 participants. Our final sample consisted of N = 76 students and other volunteers (73.6% male, 26.4% female, Mage = 25.97, SDage = 8.65) who participated in exchange for course credits and the possibility to win one of two €30 online store vouchers. We did not specifically target gamers or non-gamers; our sample contained people with low and high gaming experience (see ).

Table 1. Correlations and descriptive statistics.

Procedure

After signing an informed consent, participants downloaded and started a video game on their home computers. After finishing the game, the software directed participants to an online questionnaire assessing the dependent variables. While our institution does not have a formal ethics committee, we adhered to strict ethical guidelines to ensure our research was conducted ethically and responsibly in line with the Helsinki declaration.

The Game

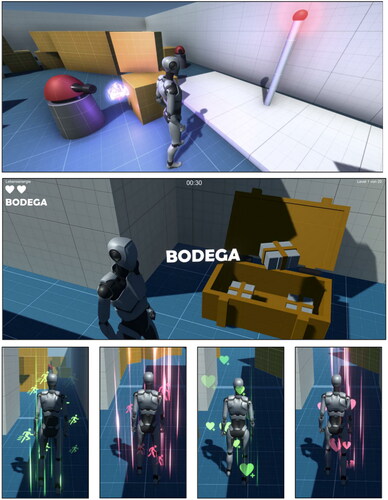

We created a new 3D third-person adventure game in the Unity Engine. shows exemplary screenshots from the game. The player’s task was to navigate an avatar through 20 different labyrinths. In each labyrinth, the player should reach a destination area within 30 s. The player could navigate through the labyrinths with the WASD keys and the mouse. The labyrinths contained a couple of stationary robots that tried to hit the player with lightning balls. The player could either dodge these balls or hide behind an object. If the player was hit, the life bar was reduced by one heart. If the player had lost all hearts or 30 s had passed without reaching the destination area, the labyrinth was counted as “failed.” Players first received basic instructions on a single screen, then passed a test labyrinth without a time limit to familiarize themselves with the controls and the task, and then started with the actual game with the 20 labyrinths. Overall, completing the game took approximately 10 minutes.

Figure 1. Screenshots from the game. (A) The general design of the labyrinths with the character, the destination area, and a robot firing a lightning ball. (B) The user interface and the moment the player receives an item. (C) The effects of the different items (i.e., speed-positive, speed-negative, healthiness-positive, healthiness-negative).

Brand Placements and Manipulations

Throughout the game, all players were exposed to four different brand placements, each belonging to a single factorial cell of the experimental design. At the beginning of each labyrinth, the player received one of four items labeled with fictitious brand names, serving as the conditioned brands. Each item affected the gameplay (). One item increased the life bar by one heart (healthiness-positive), one item decreased the life bar by one heart (healthiness-negative), one item increased the movement speed of the player (speed-positive), and one item decreased the movement speed of the player (speed-negative).

Upon receiving the item, its name appeared for two seconds in large letters, and throughout the rest of the labyrinth, the name was presented in the left upper corner (see ). We used fictitious brand names (STAREBO, TIPOKAL, BODEGA, DEMAKO, FINOKAN), which had been pretested and used as conditioned stimuli in a previous evaluative conditioning experiment (Ingendahl and Vogel Citation2023). For each participant, the brand names were assigned randomly to the different within-subjects conditions, thereby eliminating any confounding differences in brand liking. Players encountered each of the four conditioned brands five times (as done by Ingendahl and Vogel Citation2023), and the sequence of the 20 labyrinths was randomized for each player. One brand name did not appear during the game but served as a neutral baseline in the brand evaluations.

Dependent Variables

After finishing the game, participants first rated each brand on perceived speed. We presented the five brands (the four shown brands and the one unshown brand) in random order on a single slide, with a rating scale from 1 (very slow) to 7 (very fast) for each brand. Participants were instructed: “For each brand name, please indicate the characteristic you spontaneously associate with it.” Afterward, participants rated all brands on perceived healthiness on a similar scale from 1 (very unhealthy) to 7 (very healthy). Finally, participants evaluated the five brands on a scale from 1 (very negative) to 7 (very positive) to assess brand attitudes. The instructions were: “Please indicate your spontaneous evaluation of each brand name.”

Additional Questionnaires

Afterward, we assessed an adapted version of the gaming experience questionnaire from Ingendahl et al. (Citation2023), measuring three variables for exploratory purposes. Two items assessed how much players had paid attention to the brands (brand attention, “I deliberately drew my attention to the brand names in the game.”). Four items assessed how well participants could handle the controls and whether they had previous experience with computer games (game affinity, “I often play similar games.”). Two items measured how much players liked the game or had fun while playing (game liking, “I had fun while playing.”). Each item was answered on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much). In addition, we logged the player’s overall performance (i.e., how many labyrinths they passed). Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations are provided in . Last, participants answered several questions about their user behavior (e.g., whether they had turned their sound on) and sociodemographic information before they were debriefed, thanked, and dismissed.

Results

Attitudes, Speed, and Healthiness

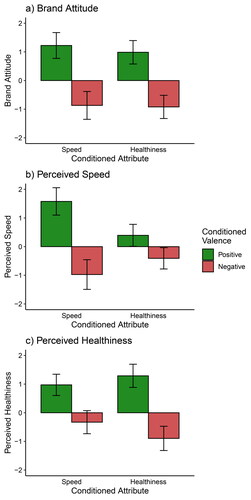

Data and analysis scripts are available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/3PXS4. We subjected the attitude, speed, and healthiness ratings to separate conditioned valence × conditioned attribute within-subjects ANOVAs with follow-up Tukey tests in the R packages afex (Singmann et al. Citation2020) and emmeans (Lenth Citation2019). For each analysis, we first subtracted the rating of the unshown brand from the ratings of the conditioned brands to compare each value against a neutral baseline. shows the mean scores on all three dependent variables.

Figure 2. Brand ratings by conditioned attribute and conditioned valence. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. All values represent relative values compared to unshown brands. We provide means and standard deviations within each factorial cell on the OSF.

On brand attitudes (), we only observed a significant main effect of conditioned valence, F(1, 75) = 67.76, p < .001, η2p = .475, such that participants evaluated brands paired with positive in-game experiences more positively than unshown brands, and brands paired with negative in-game experiences more negatively than unshown brands (Hypothesis 1). This main effect was not qualified by an interaction, F(1, 75) = 0.20, p = .660, η2p = .003.

In line with our expectations (Hypothesis 2a), the ANOVA on the speed ratings () showed a significant main effect of conditioned valence, F(1, 75) = 77.37, p < .001, η2p = .508, which was qualified by an interaction, F(1, 75) = 20.78, p < .001, η2p = .217. That is, speed ratings were higher if the brands were paired with positive versus negative in-game experiences, but the effect was stronger if the conditioned attribute was speed, t(75) = 8.10, p < .001, d = 0.93, compared to healthiness, t(75) = 3.70, p < .001, d = 0.43.

In line with our expectations (Hypothesis 2b), the ANOVA on the healthiness ratings () showed a significant main effect of conditioned valence, F(1, 75) = 64.47, p < .001, η2p = .462, which was qualified by an interaction, F(1, 75) = 4.84, p = .031, η2p = .061. That is, healthiness ratings were higher if the brands were paired with positive versus negative in-game experiences, but the effect was stronger if the conditioned attribute was healthiness, t(75) = 7.38, p < .001, d = 0.85, compared to speed, t(75) = 4.42, p < .001, d = 0.51. The main effect of conditioned attribute was not significant in any ANOVA, p-values > .074.

Moderated Mediation

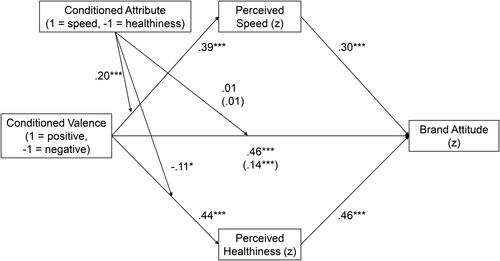

We next conducted a multilevel moderated mediation analysis in the bruceR package (Bao Citation2022). Here, we tested whether the effect of the conditioned valence (1 = positive, −1 = negative) on brand attitudes was mediated by the perceived speed and healthiness of the brand. Because we expected that the brands were differentially associated with the two attributes, conditioned attribute (1 = speed, −1 = healthiness) served as a moderator on the a-path. shows the main results of this mediation model; detailed results of the regression models are provided on the Open Science Framework (OSF).

Figure 3. Regression coefficients from the mediation analysis. Values in parentheses refer to the full mediation model when controlling for the mediators. Conditioned valence (positive = 1; negative = –1) and conditioned attribute (speed = 1; healthiness = –1) were effect-coded, the other variables were standardized at the grand mean. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

As expected, conditioned valence predicted the perceived speed and healthiness of the brand, which in turn both predicted brand attitudes (Hypotheses 3a and 3b; see ). Moreover, the conditioned attribute moderated the effect of conditioned valence on perceived speed and healthiness. As expected (Hypothesis 4a), the indirect effect through perceived speed was stronger if speed was the conditioned attribute (Hypothesis 4b), b = .177, p < .001, 95%CI [0.113, 0.252], compared to if healthiness was the conditioned attribute, b = .055, p = .009, 95%CI [0.018, 0.100]. Likewise (Hypothesis 4b), the indirect effect through perceived healthiness was stronger if healthiness was the conditioned attribute, b = .254, p < .001, 95%CI [0.179, 0.342], compared to if speed was the conditioned attribute, b = .152, p < .001, 95%CI [0.084, 0.225]. However, there was also a residual direct effect of the conditioned valence, independent of whether speed was the conditioned attribute, b = .16, p = .008, 95%CI [0.041, 0.270], or whether healthiness was the conditioned attribute, b = .13, p = .021, 95%CI [0.021, 0.242].

We also tested for the two indices of moderated mediation (Hayes Citation2015) in lavaan (Rosseel Citation2012). Both indices were significant, speed: z = 3.48, p < .001, health: z = −2.21, p = .027. Following a reviewer’s suggestion, we also tested whether there was a moderation on the b paths. This was not the case; the respective results are provided in the HTML Markdown on the OSF.

Explorative Analyses

We explored whether any of the previously reported effects were moderated by how much attention players had paid to the brands (brand attention), how well they could handle the game controls (game affinity), how much they liked the game (game liking), and the number of passed labyrinths (performance). For that purpose, we conducted separate multilevel regressions for each dependent measure where one of the four interindividual difference variables was added as a moderator. We present these models in detail on the OSF and only briefly report the main findings here. Brand attention and game affinity were the strongest moderators, positively associated with a stronger effect of the conditioned valence. Thus, players who paid more attention to the brands or could handle the controls better showed stronger brand-attitude change. Furthermore, brand attention and game affinity had a significant three-way interaction on some outcomes, such that the conditioned valence of the attribute speed had a stronger effect for players with greater brand attention and game affinity. We did not find any significant moderation by game liking and only one moderation by player performance (i.e., a stronger valence effect on brand attitudes).

General Discussion

Placing brands in video games has become a widespread marketing technique. However, the theoretical understanding regarding the effects of brand placements on brand attitudes is still insufficient. Previous research proposed that brand attitudes become more favorable due to positive affect being transferred from pleasant in-game experiences to the brands. We argue that brand attitude might also change due to the brands becoming associated with specific attributes (e.g., speed or healthiness) instead of a mere affect transfer.

In a 3D third-person adventure game, we presented brands with positive or negative speed- or healthiness-related in-game experiences. We found that brand attitudes became more positive when paired with positive in-game experiences, irrespective of whether the event was speed- or healthiness-related. However, players formed attribute-specific associations: Brands paired with positive (versus negative) healthiness-related experiences differed strongly in perceived healthiness, and brands paired with positive (versus negative) speed-related experiences differed strongly in perceived speed. Both perceived healthiness and speed were positively related to brand attitudes, and the differential effects of the different placements on perceived healthiness and speed mediated the effects on brand attitudes. These findings offer crucial theoretical implications for the factors driving attitude change from in-game placements and valuable suggestions for the effective use of such placements.

Theoretical Implications

Our study shows that positive in-game experiences elevate attitudes toward brands placed in a video game, consistent with previous reasoning and findings from the in-game advertising literature (Cowley and Barron Citation2008; Ingendahl et al. Citation2023; Waiguny, Nelson, and Marko Citation2013). Unlike previous research, our study suggests a mechanism different from direct affect transfer from the game to the brand. Specifically, brand attitudes can change because the brands become associated with specific positive attributes conveyed during the gameplay. Instead of a mere affect transfer from the in-game experience to the brand, players form a mental link between a placed brand and a specific positive attribute.

This insight corresponds well to a recent model on brand association formation (Du Plessis, D’Hooge, and Sweldens Citation2023), which differentiates between three operating processes: direct affect transfer, where people associate positive/negative affect with a brand; referential learning, where they associate a specific meaning with a brand; and predictive learning, where they form expectations on brand-outcome associations. Du Plessis, D’Hooge, and Sweldens (Citation2023) argue that these types of learning cannot be disentangled when relying only on global brand evaluations. Our study supports this and shows that what may appear to be the outcome of a direct affect transfer might sometimes reflect a different process—brands becoming associated with specific attributes. Future studies might investigate if the brand-attribute association requires that the experience is attributed to the brand (i.e., I am fast because I used the brand item) or if mere co-occurrence is sufficient to create the brand association.

Our findings also correspond nicely to a recent study by Ingendahl et al. (Citation2023). They found that brand attitude change in video games is particularly strong if brands play a central role in the game and if players remember the placement. A direct affect transfer should actually benefit from players being unaware of the placement (Du Plessis, D’Hooge, and Sweldens Citation2023), allowing an affective spillover from the game to the brand (Jones, Fazio, and Olson Citation2009). Combined with our findings, it might be that brand placement effects found by Ingendahl et al. (Citation2023) arose because players learned to associate the brands with specific attributes. Also, our exploratory analyses suggested that the effects were more pronounced among players who reported higher gaming affinity and higher attention paid to the brands. These two conditions should benefit more effortful learning processes rather than direct affect transfer (Du Plessis, D’Hooge, and Sweldens Citation2023; Hütter et al. Citation2012). In that regard, future studies could also further disentangle the underlying processes by assessing outcomes other than brand attitudes, such as brand awareness.

Last, we also observed a residual effect of the conditioned valence on brand attitudes after controlling for the perceived attributes. This effect was weaker than the indirect effect via brand associations, but it is theoretically in line with a direct affect transfer. Yet, this small direct effect could also be due to methodological constraints underlying mediation analysis (e.g., measurement reliability; Fiedler, Schott, and Meiser Citation2011). Future research might therefore focus on this residual effect and vary the necessary conditions for affect transfer (Ingendahl et al. Citation2023).

Practical Implications

Our research offers valuable suggestions on how a brand can benefit best from an in-game placement. On a practical level, our experiment suggests that the effects of in-game placements on brand attitudes highly depend on the specific in-game context. A brand placed alongside positive in-game experiences will benefit from the placement. In contrast, a brand placed alongside negative in-game experiences will receive even more negative brand attitudes than a brand not shown in the game. Thus, one implication is to place brands with positive in-game experiences.

Yet, marketers should not only consider the placement valence, but also the specific attributes that a placement context conveys. Our study suggests that in-game advertising generates associations of brands with specific attributes. This allows a positive but also highly differentiated brand image if a brand is placed optimally in a video game. It also implies that, although video games may carry various positive attributes, not all attributes may serve all brand images equally well. For example, Monster Energy usually tries to convey a brand image with attributes such as high energy (e.g., the official slogan “Unleash the beast!”). This intention starkly contrasts how the brand is presented in the adventure game Death Stranding. Here, instead of dynamic and action-loaded gameplay, a relaxing cutscene plays where the protagonist calmly drinks a can of Monster Energy in his apartment, thus rather conveying attributes such as “relaxation.” Such a placement might lead to more favorable brand attitudes toward Monster Energy but also dilute the brand image due to associations with wrong attributes.

Open Questions and Limitations

Despite several strengths of our research, such as high internal validity due to randomization, there are some open questions to mention.

First, the relationship between brand attitudes and brand associations is correlative, thus allowing reverse causality in principle. However, reverse causality would imply that players rely on their affect toward the brand when rating the attributes (Schwarz Citation2011), depending on whether the brand was shown with healthiness- or speed-related in-game experiences. Arguably, this mental task is very complex, lacks a solid theoretical process explanation, and is therefore considerably less likely than players associating a brand with a specific attribute at the first stage.

Second, although we observed differential effects of specific in-game experiences on the rated attributes, the conditioned valence still had overall effects on each attribute. For example, a brand paired with a positive healthiness-related experience was also rated higher on speed than a brand with a negative healthiness-related experience, and vice versa. We speculate that this might be because the two attributes are also naturally correlated (i.e., athletic people are also more healthy), leading to a halo effect (Leuthesser, Kohli, and Harich Citation1995).

Third, future research is needed to examine potential boundary conditions of the found effects. For example, players who are aware of the persuasive intent in the brand placements might activate defensive mechanisms to resist the persuasion attempts (Friestad and Wright Citation1994). It would be worthwhile to test in future studies to what extent such persuasion knowledge reduces direct or attribute-based brand-placement effects (Du Plessis, D’Hooge, and Sweldens Citation2023; Sweldens, Van Osselaer, and Janiszewski Citation2010). Such an approach would also provide insights to which extent the findings generalize to situations where the persuasive intent is more obvious, as in advergames.

Last, our experiment used fictitious brand names and not real brands to maximize internal validity. Previous brand-placement studies have shown that brand-placement effects are smaller for brands consumers are familiar with (e.g., Mau, Silberer, and Constien Citation2008), suggesting that the effects we obtained are likely smaller for existing brands. Likewise, our brand placements did not depict any particular products and were rather abstract, with all placements using the same model (a grey package) and format (a fictitious brand name popping up). Thus, it remains an open question to what extent the found effects generalize to more realistic product placements with a more concrete product experience.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study shows that in-game placements do not guarantee more favorable brand attitudes. Instead, the brand must co-occur with positive in-game experiences and, crucially, these experiences may convey specific attributes to create distinct brand images.

Ethics Statement

While our institution does not have a formal ethics committee, we adhered to strict ethical guidelines to ensure our research was conducted ethically and responsibly in line with the Helsinki declaration.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Moritz Ingendahl

Moritz Ingendahl (Ph.D., University of Mannheim) is a postdoctoral researcher at Ruhr University Bochum.

Leon Brückner

Leon Brückner (M.Sc., Darmstadt University of Applied Sciences) is a master’s student at Darmstadt University of Applied Sciences.

Tobias Vogel

Tobias Vogel (Ph.D., University of Heidelberg) is a full professor at Darmstadt University of Applied Sciences.

Notes

1 Some researchers also distinguish between brand placements and advergames due to conceptual differences (e.g., the overt persuasive intent of advergames) and findings indicating differential effectiveness (e.g., advergames being more effective for children; Ghosh et al. Citation2022). However, the psychological mechanisms studied in this article should apply to various types of gamified advertising.

References

- Babin, B. J., J.-L. Herrmann, M. Kacha, and L. A. Babin. 2021. “The Effectiveness of Brand Placements: A Meta-Analytic Synthesis.” International Journal of Research in Marketing 38 (4): 1017–1033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2021.01.003.

- Bao, H.-W.-S. 2022. “bruceR: Broadly Useful Convenient and Efficient R Functions.” https://cran.r-project.org/package=bruceR

- Cowley, E., and C. Barron. 2008. “When Product Placement Goes Wrong: The Effects of Program Liking and Placement Prominence.” Journal of Advertising 37 (1): 89–98. https://doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091-3367370107.

- Dardis, F. E., M. Schmierbach, B. Sherrick, F. Waddell, J. Aviles, S. Kumble, and E. Bailey. 2016. “Adver-Where? Comparing the Effectiveness of Banner Ads and Video Ads in Online Video Games.” Journal of Interactive Advertising 16 (2): 87–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2016.1223572.

- Du Plessis, C., S. C. D’Hooge, and S. Sweldens. 2023. “The Science of Creating Brand Associations: A Continuous Trinity Model Linking Brand Associations to Learning Processes.” Journal of Consumer Research 51 (1).

- Eckmann, L., F. Högden, J. R. Landwehr, and C. Unkelbach. 2021. “Attribute Conditioning in Brand Image Creation: Single versus Multiple Attributes.” In Advances in Consumer Research, edited by T. W. Bradford, A. Keinan, and M. M. Thomson, 350–51. Vol. 49, Duluth, MN: Association for Consumer Research.

- Faul, F., E. Erdfelder, A.-G. Lang, and A. Buchner. 2007. “G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences.” Behavior Research Methods 39 (2): 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146.

- Fiedler, K., M. Schott, and T. Meiser. 2011. “What Mediation Analysis Can (Not) Do.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 47 (6): 1231–1236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.05.007.

- Förderer, S., and C. Unkelbach. 2011. “Beyond Evaluative Conditioning! Evidence for Transfer of Non-Evaluative Attributes.” Social Psychological and Personality Science 2 (5): 479–486. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550611398413.

- Friestad, M., and P. Wright. 1994. “The Persuasion Knowledge Model: How People Cope with Persuasion Attempts.” Journal of Consumer Research 21 (1): 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1086/209380.

- Ghosh, T., S. Sreejesh, and Y. K. Dwivedi. 2022. “Brands in a Game or a Game for Brands? Comparing the Persuasive Effectiveness of in-Game Advertising and Advergames.” Psychology & Marketing 39 (12): 2328–2348. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21752.

- Guo, F., G. Ye, L. Hudders, W. Lv, M. Li, and V. G. Duffy. 2019. “Product Placement in Mass Media: A Review and Bibliometric Analysis.” Journal of Advertising 48 (2): 215–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2019.1567409.

- Hayes, A. F. 2015. “An Index and Test of Linear Moderated Mediation.” Multivariate Behavioral Research 50 (1): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2014.962683.

- Hofmann, W., J. De Houwer, M. Perugini, F. Baeyens, and G. Crombez. 2010. “Evaluative Conditioning in Humans: A Meta-Analysis.” Psychological Bulletin 136 (3): 390–421. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018916.

- Hütter, M., S. Sweldens, C. Stahl, C. Unkelbach, and K. C. Klauer. 2012. “Dissociating Contingency Awareness and Conditioned Attitudes: Evidence of Contingency-Unaware Evaluative Conditioning.” Journal of Experimental Psychology. General 141 (3): 539–557. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026477.

- Ingendahl, M., and T. Vogel. 2023. “(Why) Do Big Five Personality Traits Moderate Evaluative Conditioning? The Role of US Extremity and Pairing Memory.” Collabra: Psychology 9 (1): 74812. https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.74812.

- Ingendahl, M., T. Vogel, A. Maedche, and M. Wänke. 2023. “Brand Placements in Video Games: How Local in-Game Experiences Influence Brand Attitudes.” Psychology & Marketing 40 (2): 274–287. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21770.

- Jones, C. R., R. H. Fazio, and M. A. Olson. 2009. “Implicit Misattribution as a Mechanism Underlying Evaluative Conditioning.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 96 (5): 933–948. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014747.

- Karrh, J. A. 1998. “Brand Placement: A Review.” Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 20 (2): 31–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.1998.10505081.

- Kim, J., C. T. Allen, and F. R. Kardes. 1996. “An Investigation of the Mediational Mechanisms Underlying Attitudinal Conditioning.” Journal of Marketing Research 33 (3): 318–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379603300306.

- Landwehr, J. R., and L. Eckmann. 2020. “The Nature of Processing Fluency: Amplification versus Hedonic Marking.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 90:103997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2020.103997.

- Lenth, R. 2024. “_emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means_.” R package version 1.10.0. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans

- Leuthesser, L., C. S. Kohli, and K. R. Harich. 1995. “Brand Equity: The Halo Effect Measure.” European Journal of Marketing 29 (4): 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090569510086657.

- Mau, G., G. Silberer, and C. Constien. 2008. “Communicating Brands Playfully: Effects of in-Game Advertising for Familiar and Unfamiliar Brands.” International Journal of Advertising 27 (5): 827–851. https://doi.org/10.2501/S0265048708080293.

- Nelson, M. R., and M. K. J. Waiguny. 2012. “Psychological Processing of in-Game Advertising and Advergaming: Branded Entertainment or Entertaining Persuasion.” In The Psychology of Entertainment Media: Blurring the Lines between Entertainment and Persuasion, edited by L. J. Shrum, 2nd ed., 93–146. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Redondo, I. 2012. “The Effectiveness of Casual Advergames on Adolescents’ Brand Attitudes.” European Journal of Marketing 46 (11/12): 1671–1688. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090561211260031.

- Rosseel, Y. 2012. “lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling.” Journal of Statistical Software 48 (2): 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02.

- Schwarz, N. 2012. “Feelings-as-Information Theory.” In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology, edited by P. A. M. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, and E. T. Higgins, 289–308. Sage Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446249215.n15.

- Shaw, S., S. Quattry, J. Whitt, and J. Chirino. 2020. The Global Gaming Industry Takes Center Stage. New York: Morgan Stanley Investment Management.

- Singmann, H., B. Bolker, J. Westfall, F. Aust, and M. Ben-Shachar. 2024. “_afex: Analysis of Factorial Experiments_.” R package version 1.3-1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=afex

- Spears, N., and S. N. Singh. 2004. “Measuring Attitude toward the Brand and Purchase Intentions.” Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 26 (2): 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.2004.10505164.

- Sweldens, S., S. M. J. Van Osselaer, and C. Janiszewski. 2010. “Evaluative Conditioning Procedures and the Resilience of Conditioned Brand Attitudes.” Journal of Consumer Research 37 (3): 473–489. https://doi.org/10.1086/653656.

- Terlutter, R., and M. L. Capella. 2013. “The Gamification of Advertising: Analysis and Research Directions of in-Game Advertising, Advergames, and Advertising in Social Network Games.” Journal of Advertising 42 (2-3): 95–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2013.774610.

- Unkelbach, C., and S. Förderer. 2018. “A Model of Attribute Conditioning.” Social Psychological Bulletin 13 (3): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.5964/spb.v13i3.28568.

- van Berlo, Z. M. C., E. A. van Reijmersdal, and M. Eisend. 2021. “The Gamification of Branded Content: A Meta-Analysis of Advergame Effects.” Journal of Advertising 50 (2): 179–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2020.1858462.

- Vantage Market Research. 2022. “Insights on the $12.35 Bn In-Game Advertising Market Is Expected to Grow at a CAGR of over 10.7% during 2022-2028.” https://www.globenewswire.com/en/news-release/2022/06/29/2471096/0/en/Insights-on-the-12-35-Bn-In-Game-Advertising-Market-is-Expected-to-Grow-at-a-CAGR-of-over-10-7-During-2022-2028-Vantage-Market-Research.html#:$/sim$:text=TheIn-GameAdvertisingmarketwase

- Vermeir, I., S. Kazakova, T. Tessitore, V. Cauberghe, and H. Slabbinck. 2014. “Impact of Flow on Recognition of and Attitudes towards in-Game Brand Placements: Brand Congruence and Placement Prominence as Moderators.” International Journal of Advertising 33 (4): 785–810. https://doi.org/10.2501/IJA-33-4-785-810.

- Vogel, T., and M. Wänke. 2016. Attitudes and Attitude Change. New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Waiguny, M. K. J., M. R. Nelson, and B. Marko. 2013. “How Advergame Content Influences Explicit and Implicit Brand Attitudes: When Violence Spills over.” Journal of Advertising 42 (2-3): 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2013.774590.

- Wise, K., P. D. Bolls, H. Kim, A. Venkataraman, and R. Meyer. 2008. “Enjoyment of Advergames and Brand Attitudes.” Journal of Interactive Advertising 9 (1): 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2008.10722145.

- Yoon, G. 2019. “Advertising in Digital Games: A Bibliometric Review.” Journal of Interactive Advertising 19 (3): 204–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2019.1699208.