ABSTRACT

Commuting, the spatial mismatch between work and residential locations, necessitates integrated urban and transport policies to mitigate its societal impacts. While cross-border commuting (CBC) is increasing and governance of border regions is on the rise beyond national borders, no systemic review of this specific commuting pattern exists. We aim to consolidate the CBC literature accumulated over the years into a coherent and synthetic framework. Our systematic review assembles an inaugural comprehensive corpus of cross-border commuting literature. It reveals three transversal key topics (transport-oriented topic, qualitative approaches versus a lack of quantitative data, and a large majority of European papers) and four sub-topics (patterns, determinants, impacts and policies). Moreover, we consolidate findings through meticulous mapping of evidence, where most links are traced between the determinants and the level of flows across borders. Finally, the discussion offers directions for future research, with an exhortation to explicitly link policies to sustainability and social concerns, and the necessity for standardised datasets for methodological comparability across cases and in alignment with general commuting research.

1. Introduction

Commuting is the regular completion of a trip between workplace and residence (Cambridge Dictionary, Citation2022). It is a transport demand derived from the unequal distribution of work and residential locations. The commuting distance itself results from the way commuters resolve the tension between transportation costs (time) and residential costs (e.g. Alonso, Citation1960), and commuting involves a specific mode depending on the availability at both residence and workplace. An over-reliance on commuting by car brings major environmental and social costs for cities and regions, placing commuting at the forefront of urban and transport planning. Despite non-work-related activities contributing to additional daily trips, and transportation developments that reduce work journeys, commuting remains a key challenge for urban regional policies. The problem is acute and difficult to solve for a given urban region, because transport improvements that reduce the separation between workplaces and residences may in turn increase the attractiveness of more remote residential places, and thus commuting. Integrated land use, housing and transport planning policies are therefore needed. The complexity intensifies in regions where daily commuting spans multiple administrative and political boundaries.

Cross-border commuting (CBC) involves a large population. Border regions cover 60% of the EU territory and host 40% of its population (Medeiros, Citation2019). Some 1.4 million individuals, i.e. 0.6% of all employees, live in one EU country and work in another (European Commission, Citation2017). CBC has increased sharply over recent decades in the EU, following several European integration policies aimed at reducing the barrier effect of borders, notably the Schengen Agreement (Terlouw, Citation2012), the common Euro currency in January 2002, the European Free Trade Association and cooperative Interreg programmes (European Commission, Citation2017). All have facilitated the choice for individuals to seek employment across a border and benefit from a job or wage opportunity lacking in their place of residence (e.g. Terlouw, Citation2012).

While providing economic opportunities, CBC also challenges the sustainability of cross-border metropolitan regions (Decoville et al., Citation2021), much as internal commuting challenges urban and transport policies in “standard” urban regions. Integration policies have encouraged CBC, but coordination to tackle its effects – such as excess urbanisation, car dependence or public transport provision – is likely to be harder to implement than in standard contexts.

Given these challenges and increasing CBC, we aim to consolidate the CBC literature accumulated over the years, mostly from case-specific analyses or comparisons, into a coherent framework. From this framework, we identify important gaps, research needs and stress mechanisms or policies specific to cross-border areas.

We first created a comprehensive CBC corpus from a systematic bibliographical search (Section 2). The full corpus bibliographical information is available at zenodo (https://zenodo.org/records/10695950). Secondly, in Section 3, we structure the corpus based on the research objectives, topics, methods, and geography of the case studies of the identified papers. In Section 4, we thoroughly discuss the topics and sub-topics that have emerged. Note that for conciseness, although we attempt to cover all areas of the corpus, we do not cite every single paper of the corpus here. We build a knowledge map to summarise current findings, stress knowledge gaps and suggest research avenues in Section 5.

2. Building a cross-border commuting corpus

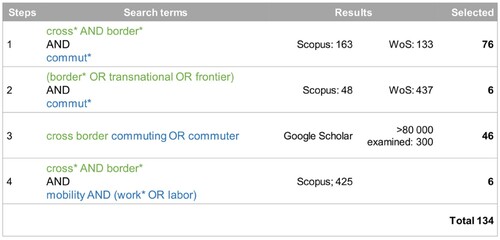

We established the CBC corpus after a systematic search within different bibliographic databases in line with the suggested PRISMA guidelines (Liberati et al., Citation2009). Our search steps are presented in . CBC combines two ideas here: that of an international border crossing (in green) and that of a commute, i.e. regular mobility for work (in blue).

Firstly, we systematically searched Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) for titles, keywords and abstracts containing the Boolean terms “cross* AND border* AND commut*”. The search was limited to the English language and to articles up until 2023 (inclusive). We identified 163 in Scopus and 133 in Web of Science, with a large number of overlaps between the two datasets. From these, we selected 76 articles according to abstract and content eligibility screening (Liberati et al., Citation2009) to ensure that CBC is one of the main topics in each selected publication. While it may seem a strict selection, one should note that before filtering, the search would have returned papers in unrelated fields such as medicine, algebra, or biochemistry. We also removed papers related to other types of mobility (e.g. residential migration, residential mobility, shopping behaviour, firms’ relocation) or non-national borders (e.g. city/municipality borders, regional).

In the second stage, we broadened our search by removing “cross*” from the query, as the terms “border*” and “commut*” alone could potentially indicate commuting across a border. Since we also noted the absence in the first outcome of recent work on CBC around Luxembourg and Switzerland (where CBC is high), we considered swapping the word “border” for “transnational” or “frontier”. This may be related to the French-speaking community of researchers in these regions. Combined with “commut*”, our second search yielded over 400 results (435 in Scopus, 449 in WoS), which we again filtered for relevance based on abstracts. After removing overlaps, and inspection, we added 6 articles to our first selection.

Following the PRISMA guidelines, we then used a more general secondary source, Google Scholar, to retrieve further articles. We used the plain phrase: “cross border commuting OR commuter”. Google Scholar is not as clear as the previous databases in terms of which documents are included in the database and how the search terms are combined. Our goal was to retrieve articles with the same two ideas, but from full content and with the possibility of identifying recent work from working papers or pre-prints of recognisable academic institutions. Since we did not aim for grey literature (reports, policy notes), we did not consider all the 1000 outputs from Google Scholar, but only the first 30 pages (300 references), as suggested by Haddaway et al. (Citation2015). We indeed found a rapid drop in academic outcome and relevance beyond that limit. From our Google Scholar output, we selected 46 additional papers, of which 9 are pre-prints, working papers or proceedings, and 37 are from journals mostly referenced in Scopus or WoS (plus more local/regional academic journals), but which were not retrieved from our earlier searches.

A final step was added after we noted that some authors use the word “mobility” instead of commuting. Mobility and borders combined, however, hint mostly at migration and development studies, hence the need to characterise the term “mobility” with work-related terms (“work* OR labour”). Given earlier overlaps between Scopus and WoS, this search was used for Scopus only and resulted, after inspecting abstracts, in the addition of 6 articles.

Our final CBC corpus comprises 134 publications. Comparatively, a basic “commut*” search alone returns a much vaster body of literature (over 90,000 in Scopus). Even our raw result of around 500 papers dealing with both “borders” and “commuting” is disproportionately low. While there is a growing and significant body of literature on CBC, we can already state that it is relatively small compared with its potential societal implications, and that it is thus timely to frame and reinforce this literature.

3. Main objectives, places, and methods in the CBC corpus

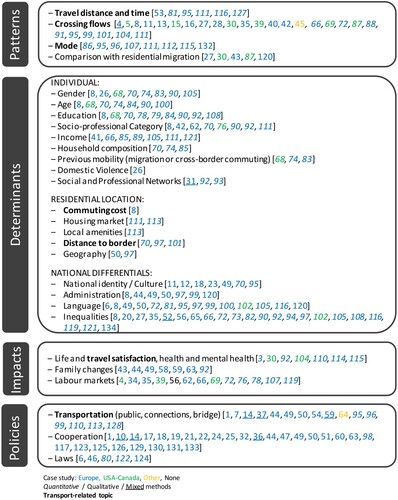

The corpus can be structured along a first tier of four topics: commuting “patterns”, “determinants”, “impacts” and “policies”, with some papers addressing several of these topics. shows a tabulation of the papers along these topics and a second tier of subtopics. References are numbered according to the table available at zenodo (https://zenodo.org/records/10695950). Colours and italic are respectively used as geography and methods tags, which we discuss next, before discussing each subtopic in detail in Section 4.

3.1. A largely European-focused body of literature

The CBC literature focuses heavily on European regions, with 88% of cases. The U.S. border is then considered in most remaining cases (9%), whilst only two publications are devoted to commuting trends between African countries. These numbers are roughly in line with the relative volumes of flows: about 1.4 million in the EU in 2017, and half a million between Mexico and the U.S.A. (Pries, Citation2019). However, the complexity of the issues and the need for policies should probably command more research, rather than flow volumes. The geographical concentration may also relate to a lack of harmonised data across borders, potentially leading to under-reported and analysed CBC flows in the global South. One could further hypothesise that these are counterbalanced by international residential migration. In any case, the scarcity of papers here indicates a need to urgently address the potential daily cross-border flows in the Global South or Asia.

After tabulating the publications according to topics and their broad geography, i.e. mostly the U.S.-Mexico border cases vs. the European cases, we see further imbalances in how these cases are used in the literature. Flow patterns, individual determinants and impacts are definitely analysed in both European and U.S.-Mexico cases. However, policy integration is almost uniquely discussed in the case of Europe, which is expected in the sense that the system is more integrated, and research then contributed to improving or stressing difficulties in that integration. In the U.S.-Mexico case, the influence of national differentials or residential choice on CBC is almost undiscussed. Its lack of integration thus appears to be taken for granted in the literature.

Within Europe, some specific cases gain more attention. The cross-border flows from Belgium, France and Germany to Luxembourg attract the greatest interest, since those regions have the highest flow volumes within the EU. This is excluding Switzerland, which is the highest receiver of flows in volume (but not as important in relative terms for its local labour market when compared to regions around Luxembourg). Next, all with a similar importance are the Sweden-Denmark Øresund case, the Estonia-Finland border, and the Austrian borders with Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia. Yet they represent much lower CBC volumes. Of the 134 publications, only 15 analyse CBC in the European area as a whole. The literature is thus largely dominated by case studies (mainly by pairs) and comparisons. This may be due to the difficulty in obtaining harmonised data across a continent, especially where spatial granularity or individual information is needed. Cross-European surveys exist but suffer from geographical information being too aggregated (e.g. Eurostat, Citation2016) for local border effects to be understood.

3.2. A qualitative body of literature in need of refined quantitative data

The CBC literature is slightly dominated by qualitative (68 papers) over quantitative methods (58 papers, italicised in ). This contrasts sharply with our understanding of the standard literature on commuting, where formalised theoretical models, applied econometrics and spatial analyses are numerous in economics, transport or geography journals. One could assume borders add a complexity that makes some quantitative methods unsuitable. In fact, given the breadth of quantitative methods elsewhere in social sciences, we rather believe this involves the effect of both (i) a focus on governance and coordination issues (which de facto requires a qualitative understanding of policy actors), and (ii) the fact that the additional complexity induced by borders requires finer data for quantitative analysis that is simply not available today. Individual panel data, for example, is rarely accessible across countries, or the definition of individual variables across national censuses may differ and require considerable effort to assemble. Comparatively, smaller qualitative surveys and interviews across a bi-national space may seem more feasible.

Within the qualitative set itself, we find a notable diversity of techniques: in-depth, open-ended and semi-structured interviews, focus groups, online questionnaires, fieldwork, observations, social media investigations, opinion polls, surveys and content analysis of literature. The target groups are primarily cross-border commuters, but also stakeholders, administrative officials, businesses and public transport policy actors. Migrants, residents of cross-border regions, security officials and local elites make up the smaller remainder of the target groups.

Within the quantitative set, the techniques are also very diverse. The great majority of publications uses mostly descriptive statistics of aggregate flows, or build and describe indicators. Yet we also find gravity models for flows, simplified destination choice models or traffic flow simulations, as well as complementary explanatory or predictive multiple regression analyses (ordinary models with and without fixed effects, interval-censored, or models from the Poisson, probit or logit families) at a geographically aggregated scale or at the individual level. In contrast, more advanced econometric models such as those dealing with endogeneity or models with counterfactuals are completely absent. The same is true for advanced spatial simulation models such as land use transport-interaction models.

The main sources of CBC data are surveys, censuses, aggregate official statistics, mobile positioning data and data from interviews. Use of administrative national data (e.g. social security, registers) or company records is clearly missing, although they are probably among the most complete sources at the individual level. This suggests important individual information is not, or maybe cannot yet, be integrated across countries, thus limiting the depth of quantitative CBC enquiries.

Because of the diversity of techniques, the variety of data sources and the relatively low overall number of quantitative CBC papers, a statistical meta-analysis dedicated to the drivers of CBC soon appeared impossible. There is no clear way to compare the coefficients of models across several papers at this stage. More and more similar models need to be implemented across cases and more data and codes must be shared within the cross-border research community.

3.3. Transport as a transversal topic

As expected, a substantial number of the subtopics identified in (in bold) are directly associated with transport research. We can link 45 papers, i.e. a third of the corpus, to transportation issues. Most of the descriptive papers include a characterisation of commuting flows in volume, distance or time (see section 4.1.1). A substantial number of papers also discuss transport modes, especially the dominance of car use in CBC (see 4.1.3), as well as the daily effect of travel satisfaction (see 4.3.1).

Transportation is then indirectly present in the corpus as soon as the decision to commute is related to the residential decision. The total distance (time) and the part of that distance before the border make up important parts of commuting costs which are traded off against housing cost differentials.

Although the CBC literature, surprisingly, does not use the car-dependency concept, much of the evidence shows a strong reliance on cars. We then see that transportation challenge and public transport provision or fares are largely discussed in the policy-oriented papers of the corpus. This is found directly in transportation systems-related papers, but also indirectly in papers dealing with cooperation policies, especially those adopting a more quantitative view.

4. Subtopics and evidence

Proceeding to the content of the CBC corpus along its four main topics, we identify subtopics, and stress their main findings and gaps (subtopics are reported and related to publications in ).

4.1. Patterns

Some 29% of the CBC papers include a description of commuting patterns through cartography or the tabulation of flows. We classify these descriptions along four subtopics: “travel distance and time”, “flow volumes”, “transport modes” and “commuting vs. residential migration trends”.

4.1.1. Travel distance and time

Distances and times do not feature in a large number of publications, despite being key metrics for understanding commuting behaviour. The negative effect of distance on the likelihood of being a cross-border commuter is clear (Mathä & Wintr, Citation2009), although important variations across cases make linking a definite time or distance range to CBC difficult. As examples, the median CBC time from Sweden to Norway is 60 min (Möller et al., Citation2018), but 44 min from Belgium to Luxembourg (Carpentier, Citation2012). The average CBC duration is roughly twice what one would find in similar countries when internal commuting is considered (e.g. 22 min in Germany (Stutzer & Frey, Citation2008) or Luxembourg (Carpentier, Citation2012)), despite some individuals possibly accepting longer commutes precisely to avoid crossing a border (Pieters et al., Citation2012).

The distance to the border is found to affect the level of integration (Drevon et al., Citation2018). However, the closer the commuters live to the border, the more similar their total trip duration is to standard commuting (Möller et al., Citation2018). A longer distance or time therefore cannot be seen as a key characteristic of CBC.

Beyond reported times and distance, the level of separation is not analysed in much detail, nor associated with individual characteristics. There are no examples in the CBC literature of studies examining wage elasticities of distance, or how job opportunities vary with commuting distance, while these are analysed in standard contexts, especially for long distances (Joly & Vincent-Geslin, Citation2016). How does distance sort households by wages in a CBC context? How does it relate to homeowners being more likely to accept a longer (or cross-border) commute (e.g. Carpentier, Citation2012)? As we show in Section 4.2, the literature investigates the reasons for CBC, but little is devoted to understanding CBC distances and times beyond descriptive statistics, and ultimately little is known about the decision trade-offs between housing and transport costs in cross-border contexts.

4.1.2. Crossing flows

Regular CBC flows originate from the early twentieth century due to unequal development and differentials in labour market attractiveness across a border (Knotter, Citation2003). In the EU, cooperation policies subsequently facilitated and increased CBC flows. These flows are hence a matter of efficiency in the labour market and lead to better allocation of skilled employees over a territory (Heinz & Ward-Warmedinger, Citation2006). However, being critical, we note that potential impacts on the fair allocation of people in the housing market (affordability, segregation) are not present in this facilitating story, despite likely effects for non-cross-border workers in border areas.

Many researchers present details for flows and changes in flows, demonstrating the increasing societal importance of CBC. One recent example is Cavallaro and Dianin (Citation2020), who find an 81% increase of CBC flows between 2012 and 2018 in Europe. In terms of the proportion of total employment, Luxembourg stands out, with over 45% of employees being cross-border commuters (Mathä & Wintr, Citation2009), increasing by about 4% every year between 2005 and 2019 (STATEC, Citation2020). Switzerland comes second (8% of employment) and Austria third (4%) (Fries-Tersch et al., Citation2018), followed by a series of much smaller bi-national connections. Some authors refer to the proportion of workers from the origin country employees rather than at destination and show surprisingly low numbers despite relatively good cross-border accessibility (e.g. 0.9% of Swedes cross the border to Norway according to Möller et al. (Citation2018), or 6% of Donegal (Ireland) workers go to Northern Ireland).

CBC flows are not limited to Europe; work facilitation policies have also existed in North America (Hochman, Citation2005), permitting intense daily flows from Mexico (and Puerto Rico) to the U.S. (e.g. Herzog, Citation1990), especially for the manufacturing sector (Kopinak & Soriano Miras, Citation2013). This is a key difference from Europe, where there is a greater variety of sectors in CBC, depending on which border zone is considered. The trend is also different: cross-border employment at the U.S.A. border is significantly decreasing (e.g. Orraca Romano, Citation2015).

4.1.3. Mode choice

As mentioned, cross-border commuters rely massively on cars. Almost 90% of commuters from Belgium to Luxembourg travel by car (Enaux & Gerber, Citation2014). Despite relatively good accessibility between Luxembourg City and northern Lorraine, over 83% of CB commuters also take the car (Schiebel et al., Citation2015). Car use also remains high for commuting between the Netherlands and Germany or Belgium (Pieters et al., Citation2012).

The suggested reasons are largely in line with the car-dependence literature, although that term is not necessarily used, such as public transport being considered expensive (Basche & Spera, Citation2023), with a further focus on transport infrastructure (Enaux & Gerber, Citation2014), and stressing the lack of public transport provision (e.g. Möller et al., Citation2018). This adds a border complexity to the more traditional density effects in public transport provision (e.g. Limtanakool et al., Citation2006). Also, while we cannot expect active modes to play a key role given the usual CBC distances, we note that issues related to active modes in the first or last connecting mile are virtually absent from the CBC literature, while it is known they can trigger or prevent the use of public transport. We can argue that the dispersion of the population on the origin side of the border, i.e. beyond reach of the planning area of the destination country, appears to be a strong impediment to public transport.

There are also important individual dimensions regarding mode choices, relating to costs (Verplanken et al., Citation2008), income (Wang & Hu, Citation2017), and the interaction between residential location and commuting choice (Limtanakool et al., Citation2006). There is no tangible measurement or cross-tabulation for these effects in CBC, or any evidence of how these trade-offs would vary relative to intra-national contexts. This is surprising, especially since finer individual aspects of the mode choice process have been analysed or discussed in CBC contexts, for example, the effect of environmental concerns and beliefs on public transport choice (e.g. Gerber et al., Citation2018) showing that cross-border workers, despite being aware of environmental issues, are not ready to leave their car for commuting.

This type of conclusion calls for a fuller understanding of CBC mode choices, including financial and time costs across the different modes and across different socioeconomic groups. Such analyses are clearly so far absent from the CBC literature. In addition, there are contradictions in the literature regarding the increase or decrease in car use for longer CBC trips (Carpentier, Citation2012). The distance effects mentioned above also need to be integrated in the perspective of mode choice.

4.1.4. Comparison with residential migration

The decision to commute a certain distance derives from the decision not to relocate or locate closer to the workplace. In standard contexts, this tension between migration (residential move) and commuting (daily mobility) tips one way or the other, based on residential characteristics and prices vs. transport time and costs. This tension is, surprisingly, not much discussed in the CBC literature, whereas we expected it to be even more important since daily journeys across a border bear additional burdens that, everything else being equal, may tip the balance in favour of relocation.

In general, migration occurs when individuals seek a more beneficial combination of house prices and employment opportunities in another housing and labour market (Van Ommeren et al., Citation1997). These markets, together with household and individual preferences (e.g. Van Ommeren et al., Citation1997), moving costs (Romani et al., Citation2003), urban structure and amenities, exurbanisation (Renkow & Hoover, Citation2000) or school quality (Siim & Assmuth, Citation2016) determine that decision. Two-earner households tend to be less likely to move than single-earner ones, while higher-educated and younger individuals are more likely to choose to migrate (Paci et al., Citation2010). What those tensions become in border contexts is seldom analysed, but interestingly some authors indicate that CBC can be considered a first step towards future migration (e.g. Kopinak & Soriano Miras, Citation2013). Understanding who is willing or able to migrate and who is stuck or willing to remain on the other side of the border is crucial. Around Luxembourg, for example, housing price differentials across the border and housing supply strategies seem to prevent some migration (e.g. Carpentier, Citation2012), although these effects are not explicitly modelled. Similarly, immigrants from Mexico to the U.S. have a higher income than cross-border workers (Orraca Romano, Citation2015). There is definitely a need for relevant research on CBC flows compared with migration, but also to shed light on these numbers with preferences and budget constraints.

4.2. Determinants

The largest part of the CBC corpus investigates the determinants for cross-border commuting. Three categories of determinants are investigated in the literature: individual or household level, residential place characteristics and national variations at larger scale.

4.2.1. Individual determinants

Gender is a strong determinant of CBC commuting. Women are less likely to engage in CBC, resulting in men representing 58–81% (in our corpus) of cross-border workers (e.g. Mooses et al., Citation2020). Even though long distance is not a clear feature of CBC, one may draw parallels with long-distance commuting research, where women are found to undertake shorter journeys (e.g. Broersma et al., Citation2020), and to identify similar reasons, such as greater childcare responsibilities (e.g. Broersma et al., Citation2020) or more risk-averse behaviour (Nowotny, Citation2010).

Younger individuals commute more across borders (Huber, Citation2014). The average age of cross-border commuters is between 35 and 40 (Alegria, Citation2002), after which the willingness to engage in CBC decreases (e.g. Nowotny, Citation2010).

The effect of educational attainment level is somewhat contradictory. Seven studies (e.g. Huber, Citation2014) show that CBC increases in line with education level, but Wiesböck and Verwiebe (Citation2017) show that most cross-border commuters have medium educational qualifications, and Huber (Citation2014) indicates they are less educated than migrants and internal commuters. Compared to internal commuting, one must also add a barrier effect due to recognition of qualifications (Gijsel & Janssen, Citation2000) and, more generally, skills transfers across borders (Huber, Citation2012).

Like education, income can be both a push and a pull factor, increasing or limiting CBC depending on the labour market on both sides of the border. Higher wages across the border increase CBC (e.g. Edzes et al., Citation2022), whereas a higher wage expectation at home restrains CBC (Nowotny, Citation2014). Broersma et al. (Citation2020), such that a 1% increase in the wage difference across a border increases CBC by 19%. This effect, however, may not be linear: at the low-income end, even low wages across a border can be attractive to worse-off individuals on the other side of it, as long as their living standard would increase (Wiesböck, Citation2016). At the upper-income end, we would expect from standard literature that individuals may accept longer commutes and extra costs (e.g. Sandow, Citation2008), but the CBC literature seems so far largely focused on average income differentials between countries rather than any specificity along income distribution.

With regard to household composition, the literature shows that individuals who live with children (or people requiring care) are less likely to commute across a border (Nowotny, Citation2010). The presence of another cross-border commuter in the household does not affect the decision unless there are also children (Gottholmseder & Theurl, Citation2007). While living alone increases the probability of longer commutes in general (e.g. Paci et al., Citation2010), it does not seem to increase the likelihood of commuting over a border (Nowotny, Citation2014). We can conjecture that living alone would actually simplify a residential move across the border.

Other individual effects specific to the CBC literature include peer networks that facilitate administration or finding a job across the border (e.g. Wiesböck & Verwiebe, Citation2017) and previous mobility (e.g. Alegria, Citation2002).

4.2.2. Residential location

Several attributes of residential location determine the likelihood of CBC. There is an obvious effect of the distance to the border in terms of the decision to become a cross-border commuter: in close proximity – 10 km for Chilla and Heugel (Citation2019) or Bello (Citation2020) – CBC is more likely (Gottholmseder & Theurl, Citation2007). Yet there is likely a chicken and egg effect (endogeneity and self-selection) related to housing prices as in the classical literature (e.g. Van Ommeren et al., Citation1997) as well as decisions to migrate close to the border from other parts of the country in order to then commute across borders. These are difficult effects to uncover, typically needing longitudinal individual data mostly unavailable due to a change of country being made at the individual level for either the job or residence, while census and administrative data are country-based. Probabilities of commuting are therefore analysed ex-post, without these methodological problems being tackled in CBC contexts.

Furthermore, internal commuting distance also depends on wages (e.g. Rouwendal & Meijer, Citation2001). An interaction between distance and a potential wage gap is thus to be expected in CBC. Although suggested (e.g. Greve & Rydbjerg, Citation2003), this interaction has not yet been quantified.

Even within short distance ranges, other geographical variations matter. Mountains make transportation more difficult (Medeiros, Citation2018), and amenities such as urban quality or landscapes prevent relocation and thus encourage CBC (Gerber et al., Citation2017), similarly to longer commutes within countries (e.g. Rouwendal & Meijer, Citation2001).

In principle, both job accessibility and amenities are reflected in the housing market, and the decision to commute is thus a simple trade-off between housing and commuting costs. However, further discrepancies seem to arise because of the border, making the market particularly more attractive on one side of the border. This is reported around Luxembourg (e.g. Carpentier, Citation2012), but the exact reasons for abrupt changes in housing prices (discontinuity) are not fully understood, even if planning or supply-side rigidities exist in that case (Paccoud et al., Citation2022).

4.2.3. National differentials

National differences can be both a driving force and an obstacle to CBC. Firstly, like any other spatial interaction, CBC flows result from an imbalance between an origin and a destination. This imbalance can be local and can emerge from the daily urban system, but can also stem from differences at the larger national or regional scales. CBC flows are high when there are unequal levels of income, taxation and employment between regions (e.g. Edzes et al., Citation2022), although they are not necessarily quantified. Some authors also stress the effect of more general economic differences or poverty (e.g. Wiesböck & Verwiebe, Citation2017). Others stress the role of general inequalities in housing markets and living costs (e.g. Greve & Rydbjerg, Citation2003) that prevent people from moving and thus foster CBC.

Secondly, national borders, by definition, also create administrative, political and legal differences, which are clearly reported to function as obstacles to CBC (e.g. Medeiros, Citation2018). National borders sometimes also parallel important cultural differences. Further, many researchers suggest the existence of a mental border or the importance of a feeling of belonging that reduce CBC (e.g. Svensson & Balogh, Citation2018). Individual open-mindedness towards other cultures then seems to favour CBC (Gottholmseder & Theurl, Citation2007).

Lastly, language similarities or differences are a significant incentive or deterrent to CBC and often stressed in the literature (e.g. Broersma et al., Citation2020). Ethno-linguistic minorities are also found to be more willing to commute across a border (Mooses et al., Citation2020).

4.3. Impacts

Three types of CBC impacts emerge from the corpus: impacts on travel and life satisfaction, on family balance and on the labour market. The absence of specific analyses of the environmental or societal impacts of CBC through car use or urbanisation is notable. These issues are somewhat present, however, within policy-oriented papers, or those dealing with general challenges, such as Durand et al. (Citation2020), mentioning residential segregation, urban sprawl or extreme commuting as negative impacts.

4.3.1. Life and travel satisfaction

The effect of commuting in general on travel and life satisfaction was the object of a recent review by Tao et al. (Citation2022). Longer commuting is generally associated with lower travel and life satisfaction (e.g. De Vos, Citation2019) or higher stress (Stone & Schneider, Citation2016). It is also the case in a CBC context (e.g. Gerber et al., Citation2017). Yet, again, CBC cannot be equated to longer commuting, especially given a positive impact on life satisfaction found for CBC. More precisely, Haindorfer (Citation2020) finds that individuals perceive their living conditions have improved after CBC compared with other workers at the origin place. Nonnenmacher et al. (Citation2021) find cross-border workers have an improved health index compared with non-cross-border workers. The improvement is associated with wages and the premium obtained after crossing the border. More surprisingly, it also holds after controlling for wages, which the authors relate to a self-selection process: healthier workers are more likely to engage in CBC.

With regard to the mode of commuting – which is another aspect of satisfaction (Tao et al., Citation2022) – the results are mixed, arguably from different CBC contexts: greater travel satisfaction is found when public transport is used for CBC around Luxembourg (Gerber et al., Citation2020), while public transport commuters report feelings of boredom, frustration and powerlessness at the Mexico-U.S. border (Rodríguez & Curlango Rosas, Citation2013).

4.3.2. Family changes

CBC has a noticeable effect on household roles and family relationship dynamics (Siim & Assmuth, Citation2016) and sometimes causes disruptions (Michniak, Citation2016). CBC affects commuters themselves, but also other household members; i.e. in their support role in communication and networking, or in the need to learn languages (Telve, Citation2019). Children seem also to be more confused, especially when CBC is carried out weekly rather than daily (Siim & Assmuth, Citation2016). The within-family balance is also affected by the behavioural attributes of the commuter: some develop a more independent (selfish) behaviour due to the mobility (Frigren & Telve, Citation2020), whereas others become more involved in family life, especially when the job comes with additional advantages such as additional parental leave or flexible work (Telve, Citation2018).

4.3.3. Labour markets

The literature often generally emphasises how the opening of borders triggers economic development in border regions and its increasing role in national labour markets (e.g. Durand et al., Citation2020). Some research addresses more specifically how CBC affects labour markets. Unemployment rates are found to decrease because of CBC in the origin regions and increase in destination regions (where cross-border workers are preferred), or lead to the creation of more jobs, thereby reducing unemployment (Pierrard, Citation2008). However, cross-border commuters do not seem to affect wages (Moritz, Citation2011). Some effects on labour market dynamics are also found, with more flexibility in the presence of cross-border commuters (e.g. Klatt, Citation2014). One could argue that there is self-selection and people are attracted to more flexible labour markets. Yet cross-border labour markets should not be mistaken for globalised labour markets associated with residential migration (Gerber, Citation2012). In the U.S.-Mexico case, Alegria (Citation2002) also reminds us that CBC workers participate in – and thus influence – two labour markets: that of their destination, from which they receive their wages, and of their origin, where they usually spend these wages.

4.4. Policies

Transportation policies and cooperation and integration policies represent together a very large proportion of the CBC literature.

4.4.1. Transportation

Various authors stress that stakeholders understand the role of transportation systems in supporting regional economic growth (e.g. Decoville & Durand, Citation2016). The development of public transportation across borders then appears to be a key policy challenge and calls for cooperation and planning (Durand & Nelles, Citation2014). Research clearly emphasises that public transportation is currently insufficient to cope with increasing CBC (e.g. Gerber et al., Citation2017) including residents of rural areas (Cavallaro & Dianin, Citation2020). That echoes issues of public transport efficiency or affordability within countries (e.g. Coulson et al., Citation2001).

In addition to public transportation, road infrastructure development is also discussed in the CBC literature (Medeiros, Citation2018), including heavy infrastructure such as bridges (e.g. Balogh & Pete, Citation2018) or underwater tunnels (Schmidt, Citation2005). While there is a clear agreement in transport research in general that building more roads is not a sustainable long-term solution for cities, or a solution to congestion, this is barely seen in the CBC literature. This does not mean that it is ignored, but rather that the focus is on the inter-regional transport scale rather than framed as an urban question where the effect of a derived demand is probably clearer. CBC is actually a mix of both, an inter-regional question and an urban question – albeit spanning two countries – but transport policy questions seem largely framed under the first domain.

4.4.2. Cooperation

Cooperation between border regions is the most documented policy topic within the CBC literature. It includes, but is not specific to, commuting. The primary issue emerges from the fact that policies aimed at “removing” borders are undertaken at national level and may thus ignore effects on border regions themselves (e.g. Medeiros, Citation2018). More specifically, the imbalance between the governing level and the area affected by CBC seems to arise from a lack of interest in promoting cross-border cooperation (Decoville & Durand, Citation2016), policymakers’ lack of experience regarding the specificities of cross-border settings (e.g. Svensson & Balogh, Citation2018), or insufficient funding (e.g. Medeiros, Citation2014). Researchers suggest that local governments should be put in charge of cooperation policies (Schmidt, Citation2005), with increased mutual trust (Sohn, Citation2014), and that policies should be based on market needs rather than political wishes (Lofgren, Citation2008). They also suggest an increased role for cross-border institutions, organised networks (e.g. Cavallaro & Sommacal, Citation2019) and programmes including INTERREG (Medeiros et al., Citation2023). Other than general cooperation policies, some domain-specific policies also indirectly impact commuting behaviour or residential mobility over the border, i.e. shared health facilities (Herzog, Citation1990), digital services (Soe, Citation2018), discounted tolls (Knowles & Matthiessen, Citation2009) or technology-based border controls (Morchid & O’Mahony, Citation2019). Recent literature stresses the impacts of COVID restrictions on cross-border workers. The border closures created uncertainty (Böhm, Citation2022) and dissatisfaction, highlighting the need for a cross-border functional management system.

4.4.3. Laws and administration

While the effect of administrative differences on work and residential decisions is not specific to cross-border areas, it is of particular importance here. Laws and agreements allowing the free movement of commuters between countries are essential to CBC flows (Parenti & Tealdi, Citation2023). The relative location of firms and households, and hence commuting costs and flows, can be affected by subsidies and tax incentives that vary across space (e.g. Coulson et al., Citation2001). In CBC contexts, these spatial variations are the norm rather than the exception, governed by several national laws and multinational agreements (work permits, taxation laws). As documented mostly for the EU (e.g. Nahrstedt, Citation2000), tax and social security laws are the main sources of imbalances between CBC and internal workers, and influence the decision whether to locate to the country of employment or not. Nahrstedt (Citation2000) examined the legislation and related conflicts, and notes that cases have been usually resolved in favour of CBC workers, and thus that imbalances tend to decrease over time. The rise of flexible working time and teleworking may, however, add new dimensions to these issues in the short term. Nahrstedt (Citation2000) also mentions that discrimination may arise in domains other than income and social security, such as investment or property allowances. In addition, CBC may in turn significantly affect social security systems (family, pensions, etc.) themselves, although this seems to be reported only for Luxembourg, where the proportion of cross-border workers in the labour force is very high (Labouré, Citation2019).

5. Discussion

We have taken stock of the literature on CBC, a growing but still limited body of literature with respect to its spatial and demographic importance. We have so far described its key topics, subtopics, methods and content. We now summarise and frame the main findings (5.1), to discuss gaps and stress development opportunities in the field (5.2).

5.1. Knowledge summary

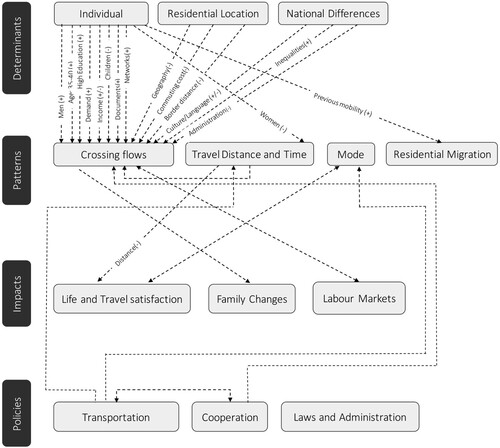

In , we provide a visual summary in the form of a knowledge map showing the main connections between the different topics present in the CBC literature and summarising the results of our content analysis. The knowledge map is structured along the subtopics identified in . Directional connectors are used to represent agreements across case studies in the literature and a + or – sign indicates whether a positive or a negative effect is found for the subtopic. The summary map by no means suggests a general cross-border commuting process, but rather aims to stress commonalities between cases as well as unknowns. As per our discussion in section (4), intrinsic variations across studies and geographical specificities are important and may prevent further generalisation.

It is clear that the majority of the agreed connections that can currently be traced in the literature are between the determinants and the levels of flows across borders. The individual effects and residential location effects on crossing flows also generally align with expectations from standard commuting knowledge. In that sense, CBC is a very standard form of commuting, albeit more intense and sharing similarities with longer-distance commuting. As with a longer commute, CBC is more likely for men, those developing their careers, those with higher education and those with fewer children. Residential distance to the border acts as a commuting cost, just as a standard distance to jobs. National differences then add complexity in determining an individual’s commuting probability, mostly adding a barrier through language (culture) or administrative differences.

At a more aggregate scale, the pattern of distances and time (accessibility) in turn affects the feasibility of CBC flows. Similarly, aggregate flows are indirectly influenced by cooperation policies that smooth out administrative differences or support cross-border infrastructure. Flows, however, are both impacted by and impact on labour markets, in that imbalances in job availability create flows, and these flows in turn create further imbalances.

Transportation modes for commuting across borders are surprisingly barely connected to individual characteristics. Distance and mode choice effects on life and travel satisfaction have been identified in CBC, but whether the individual determinants of mode choice differ in a CBC setting or a standard setting still needs to be identified after controlling for accessibility effects or cross-national differences, for example. What is currently agreed is that there is insufficient public transport provision across borders. Given current sustainability challenges, however, this is no different from a conclusion one would also draw for internal commuting.

From the policy side, it can be clearly identified in the literature that transport provision policies must affect travel distances and times, ultimately reducing costs to individuals. Integration policies are intended to overcome national differences seen as barriers at the individual level, especially from the labour market perspective. We can then see cooperation policies as an instrumental (sub-)policy to improve both integration and transport policies.

5.2. Future research directions

First and most striking in our mapping attempt is probably the many missing or under-examined links between the subtopics. For example, how is residential migration (vs. commuting) affected by residential characteristics (local labour markets, housing supply, neighbourhood quality, local amenities, etc.), accessibility or vehicle ownership? How are travel times and distances linked to modes? How do cooperation and differences in laws affect life or travel satisfaction or mental health in cross-border areas? Since these are links within existing and identified CBC topics, we believe these are research questions for which answers lie close at hand. Based on these findings then comes the question of how further variations exist across large regions (politically integrated or not) or can be explained by specific characteristics of the origin and destination countries.

Secondly, there are topics or subtopics that are simply absent to date. Commuting by car typically, and particularly over long distances, is not without impact on the environment and the planet. Pollution effects or the contribution to CO2 emissions (and their accounting on one or the other side of the border) are not yet part of the CBC impacts literature, for example. Equity, segregation or housing markets also seldom appear. The field seems to work somewhat in isolation, stressing the specificities due to a border but somehow downplaying the issues and challenges that apply to standard commuting, and thus not fully benefitting from more general findings and methods. In addition, it remains to be seen to what extent policies are entirely novel because of the CBC context, or whether environmental, social and urban planning policies applied in other contexts would work well.

Thirdly, the effects of the distance to the border and ultimately the spatial extent of the cross-border particularities have not been sufficiently explored. Rather than a singularity, CBC could be seen in a more continuous way in space, gradually equating to standard commuting and with national discontinuities being treated in the same way as any other administratively variable factor. Where differences remain, this perspective would highlight the need for more focused policies (infrastructure, labour, housing, etc.) and the geographic space where increased cooperation is needed.

Fourthly, more elaborate empirical studies are needed to deepen the links identified above. It seems essential that the results of the qualitative research (surveys of actors, commuters, etc.) are examined further and supported by quantitative empirical evidence. Quantitative evidence could also be built from more advanced methods (econometric, spatial analytics, simulation, etc.) that can be found in standard urban and transport literature dealing with commuting. It is also equally important to reflect on how the individual effects identified quantitatively can feed into or be triggered by the qualitative research, which to date has been focused more on governance than individual behaviour. Along similar lines, it is important to remember that Europe is over-represented in the field, especially regarding scales of governance and cooperation policies.

Fifthly, a key challenge to further empirical research is the lack of comparable data. It is not surprising that most studies stress specificities rather than commonalities. Direct comparative research remains rare, and potential analyses over even wider territories (several countries) lack the necessary geographical granularity. The wide variety of variables and data types adds to a lack of agreed standard methodologies across cases. Evidence is largely based on ad-hoc surveys implemented at the origin or the destination country, and specifically related to the CBC cohorts. They are difficult to reconcile with other internal data and even more across different pairs of countries. Overall, a proper meta-analysis is impossible at this stage. We believe that working towards comparable mapping, models, estimations and surveys across many cross-border areas must be encouraged.

It also appears there have been no major efforts regarding data in the field, and almost no use of social media data. In Europe, continued investment in making census data available at a 1 km grid (Eurostat, Citation2023) rapidly improves the situation, provided the cross-border complexity is not lost in the process. At the global scale, the approach used within the Global Human Settlement (GHSL) framework is also an important step forward, since attention is paid to avoiding border biases (Maffenini et al., Citation2020). Järv et al. (Citation2023) suggest using social network data since they are similar across national borders and can provide additional longitudinal or seasonal information at a refined spatial scale.

Lastly, it is crucial to monitor changes in CBC flows and determinants after new events or changing behavioural trends. The Covid-19 pandemic and the increase in teleworking are evident examples. The closing of borders and different national strategies affected CBC and decreased trust in the capacity for cooperation between neighbouring countries (e.g. Novotný & Böhm, Citation2022). Teleworking and more generally new patterns of work or residence are heavily debated these days and likely to affect commuting traffic, patterns and impacts everywhere. In cross-border areas, such changes could tip the balance heavily towards residing outside the country of work, with transportation costs having less weight in the decision-making process.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we offer the first extensive systematic literature review of cross-border commuting. It is an increasing reality that challenges urban development and transport policies precisely where cooperation and integration is difficult. While commuting inherently arises from the spatial separation of jobs and residential areas, borders introduce disruptive elements that accentuate disparities. They emphasise the need for integrated land use and transport policies, with the added complexity of labour market, administrative or cultural differences. Despite being a largely neglected subject of study, cross-border regions confront contemporary sustainability and social challenges that demand scrutiny.

We structured the scholarly corpus compiled into four principal topics and around 30 subtopics, of which 6 relate directly to transportation research, and most indirectly. The corpus comprises many case studies with some comparative work but generally a lack of knowledge integration and synthesis. We argue the field needs consolidation, more cross-fertilisation across case studies, and more comparisons with transport analyses in non-cross-border areas.

Beyond assembling the corpus, we also identified gaps and can now suggest the field develops towards (1) a rigorous examination of the connections between various components within the existing cross-border commuting system, (2) explicitly embracing sustainability and social challenges related to any urban and transport development, (3) more clearly identifying the spatial areas where borders lead to behavioural or policy specificities, (4) obtaining stronger and comparable quantitative evidence and its links to qualitative understanding, (5) homogenising data and approaches, and lastly (6) considering recent changes due to more flexible working patterns, as they are likely to have even more impact in border areas than elsewhere.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to Prof. Dr. Philippe van Kerm who provided valuable insights throughout the research process. Additionally, we would like to thank Dr. Stamatis Kalogirou and Prof. Dr. Rosella Nicolini for their constructive feedback. Finally, we are grateful to Margaret Vince for English proofreading.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alegria, T. (2002). Demand and supply of Mexican cross-border workers. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 17(1), 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2002.9695581

- Alonso, W. (1960). A theory of the urban land market. Papers in Regional Science, 6(1), 149–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1435-5597.1960.tb01710.x

- Balogh, P., & Pete, M. (2018). Bridging the gap: Cross-border integration in the Slovak-Hungarian borderland around Štúrovo-Esztergom. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 33(4), 605–622. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2017.1294495

- Basche, H., & Spera, F. (2023). Interactions between key factors that influence cross-border cooperation in public transport: The case of the Euregio Meuse-Rhine. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 38(5), 681–698. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2021.1957978

- Bello, P. (2020). Exchange rate effects on cross-border commuting: Evidence from the Swiss-Italian border. Journal of Economic Geography, 20(3), 969–1001. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbz025

- Böhm, H. (2022). Challenges of pandemic-related border closure for everyday lives of Poles and Czechs in the divided town of Cieszyn/Český Těšín: Integrated functional space or reemergence of animosities? Nationalities Papers, 50(1), 130–144. https://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2021.51

- Broersma, L., Edzes, A., & van Dijk, J. (2020). Commuting between border regions in The Netherlands, Germany and Belgium: An explanatory model. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 37(3), 551–573. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2020.1810590

- Cambridge Dictionary. (2022). Cambridge University Press. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/

- Carpentier, S. (2012). Cross-border local mobility between Luxembourg and the Walloon region: An overview. European Journal of Transport and Infrastructure Research, 12, 198–210.

- Cavallaro, F., & Dianin, A. (2020). Efficiency of public transport for cross-border commuting: An accessibility-based analysis in central Europe. Journal of Transport Geography, 89, Article 102876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2020.102876

- Cavallaro, F., & Sommacal, G. (2019). Public transport in transnational peripheral areas: Challenges and opportunities. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, 879, 554–561. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02305-8_67

- Chilla, T., & Heugel, A. (2019). Cross-border commuting dynamics: Patterns and driving forces in the alpine macro-region. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 37(1), 17–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2019.1700822

- Coulson, N. E., Laing, D., & Wang, P. (2001). Spatial mismatch in search equilibrium. Journal of Labor Economics, 19(4), 949–972. https://doi.org/10.1086/322824

- Decoville, A., & Durand, F. (2016). Building a cross-border territorial strategy between four countries: Wishful thinking? European Planning Studies, 24(10), 1825–1843. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1195796

- Decoville, A., Durand, F., & Sohn, C. (2021). Cross-border spatial planning in border cities: Unpacking the symbolic role of borders. In Border cities and territorial development (pp. 39–56). Routledge.

- De Vos, J. (2019). Satisfaction-induced travel behaviour. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 63, 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2019.03.001

- Drevon, G., Gerber, P., Klein, O., & Enaux, C. (2018). Measuring functional integration by identifying the trip chains and the profile of cross-border workers: Empirical evidences from Luxembourg. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 33(4), 549–568. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2016.1257362

- Durand, F., Decoville, A., & Knippschild, R. (2020). Everything all right at the internal EU borders? The ambivalent effects of cross-border integration and the rise of Euroscepticism. Geopolitics, 25(3), 587–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2017.1382475

- Durand, F., & Nelles, J. (2014). Binding cross-border regions: An analysis of cross-border governance in Lille-Kortrijk-Tournai eurometropolis. Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 105(5), 573–590. https://doi.org/10.1111/tesg.12063

- Edzes, A. J., van Dijk, J., & Broersma, L. (2022). Does cross-border commuting between EU-countries reduce inequality? Applied Geography, 139, Article 102639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2022.102639

- Enaux, C., & Gerber, P. (2014). Beliefs about energy, a factor in daily ecological mobility? Journal of Transport Geography, 41, 154–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2014.09.002

- European Commission. (2017). Communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament – boosting growth and cohesion in EU border regions.

- Eurostat. (2016). Statistics on commuting patterns at regional level.

- Eurostat. (2023). The statistical office of the European Union.

- Fries-Tersch, E., Tugran, T., Markowska, A., & Jones, M. (2018). 2018 annual report on intra-EU labour mobility.

- Frigren, P., & Telve, K. (2020). Historical and modern perspectives on mobile labour: Parallel case study on Finnish and Estonian cross-border worker stereotypes and masculinities. Nordic Journal of Migration Research, 10(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.2478/njmr-2019-0018

- Gerber, P. (2012). Advancement in conceptualizing cross-border daily mobility: The Benelux context in the European Union. European Journal of Transport and Infrastructure Research, 12(2), 178–197.

- Gerber, P., Ma, T. Y., Klein, O., Schiebel, J., & Carpentier-Postel, S. (2017). Cross-border residential mobility, quality of life and modal shift: A Luxembourg case study. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 104, 238–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2017.06.015

- Gerber, P., Thériault, M., Enaux, C., & Carpentier-Postel, S. (2018). Modelling impacts of beliefs and attitudes on mode choices. Lessons from a survey of Luxembourg cross-border commuters. Transportation Research Procedia, 32, 513–523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2018.10.037

- Gerber, P., Thériault, M., Enaux, C., & Carpentier-Postel, S. (2020). Links between attitudes, mode choice, and travel satisfaction: A cross-border long-commute case study. Sustainability, 12(21), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219203

- Gijsel, P. D., & Janssen, M. (2000). Understanding the Dutch-German cross-border labour market: Are highly educated workers unwilling to move? Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 91(1), 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9663.00093

- Gottholmseder, G., & Theurl, E. (2007). Determinants of cross-border commuting: Do cross-border commuters within the household matter? Journal of Borderlands Studies, 22(2), 97–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2007.9695679

- Greve, B., & Rydbjerg, M. (2003). Cross-border commuting in the EU: Obstacles and barriers country report: The Øresund region.

- Haddaway, N. R., Collins, A. M., Coughlin, D., & Kirk, S. (2015). The role of Google Scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searching. PLoS One, 10(9), e0138237. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138237

- Haindorfer, R. (2020). Impacts of negative labor market experiences on the life satisfaction of European East-West mobile workers: Cross-border commuters from the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary in Austria. Journal of Industrial Relations, 62(2), 256–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185619897087

- Heinz, F., & Ward-Warmedinger, M. (2006). Cross-border labour mobility within an enlarged EU (ECB Occasional Paper, 52).

- Herzog, L. (1990). Border commuter workers and transfrontier metropolitan structure along the United States-Mexico border. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 5(2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.1990.9695393

- Hochman, J. (2005). Border planning for the 21st century. Public Roads, 68(4), 2–8.

- Huber, P. (2012). Do commuters suffer from job-education mismatch? Applied Economics Letters, 19(4), 349–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2011.577004

- Huber, P. (2014). Are commuters in the EU better educated than non-commuters but worse than migrants? Urban Studies, 51(3), 509–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098013498282

- Järv, O., Aagesen, H. W., Väisänen, T., & Massinen, S. (2023). Revealing mobilities of people to understand cross-border regions: Insights from Luxembourg using social media data. European Planning Studies, 31(8), 1754–1775. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2022.2108312

- Joly, I., & Vincent-Geslin, S. (2016). Intensive travel time: An obligation or a choice? European Transport Research Review, 8(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12544-016-0195-7

- Klatt, M. (2014). (Un)familiarity? Labor related cross-border mobility in Sønderjylland/Schleswig since Denmark joined the EC in 1973. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 29(3), 353–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2014.938968

- Knotter, A. (2003). The border paradox. Uneven development, cross-border mobility and the comparative history of the Euregio Meuse-Rhine. Federalisme Regionalisme, 3, 2002–2003.

- Knowles, R., & Matthiessen, C. (2009). Barrier effects of international borders on fixed link traffic generation: The case of Øresundsbron. Journal of Transport Geography, 17(3), 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2008.11.001

- Kopinak, K., & Soriano Miras, R. (2013). Types of migration enabled by maquiladoras in Baja California, Mexico: The importance of commuting. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 28(1), 75–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2012.751733

- Labouré, M. (2019). Pensions: The impact of migrations and cross-border workers in a small open economy. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, 18(2), 247–270. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474747217000464

- Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzla, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P. J., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ, 339(1), b2700. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2700

- Limtanakool, N., Dijst, M., & Schwanen, T. (2006). On the participation in medium- and long-distance travel: A decomposition analysis for the UK and The Netherlands. Journal of Economic and Social Geography, 97, 389–404.

- Lofgren, O. (2008). Regionauts: The transformation of cross-border regions in Scandinavia. European Urban and Regional Studies, 15(3), 195–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776408090418

- Maffenini, L., Schiavina, M., Melchiorri, M., Pesaresi, M., & Kemper, T. (2020). GHS-DUG user guide (Technical Report Version 4). Publications Office of the European Union.

- Mathä, T., & Wintr, L. (2009). Commuting flows across bordering regions: A note. Applied Economics Letters, 16(7), 735–738. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504850701221857

- Medeiros, E. (2014). Territorial cohesion trends in inner Scandinavia: The role of cross-border cooperation – INTERREG-A 1994–2010. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift – Norwegian Journal of Geography, 68(5), 310–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2014.960949

- Medeiros, E. (2018). Should EU cross-border cooperation programmes focus mainly on reducing border obstacles? Documents d'Anàlisi Geogràfica, 64(3), 467–491. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/dag.517

- Medeiros, E. (2019). Cross-border transports and cross-border mobility in EU border regions. Case Studies on Transport Policy, 7(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cstp.2018.11.001

- Medeiros, E., Ramírez, M. G., Brustia, G., Dellagiacoma, A. C., & Mullan, C. A. (2023). Reducing border barriers for cross-border commuters in Europe via the EU b-solutions initiative. European Planning Studies, 31(4), 822–841. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2022.2093606

- Michniak, D. (2016). Main trends in commuting in Slovakia. European Journal of Geography, 7(2), 6–20.

- Möller, C., Alfredsson-Olsson, E., Ericsson, B., & Overvåg, K. (2018). The border as an engine for mobility and spatial integration: A study of commuting in a Swedish-Norwegian context. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift, 72(4), 217–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2018.1497698

- Mooses, V., Silm, S., Tammaru, T., & Saluveer, E. (2020). An ethno-linguistic dimension in transnational activity space measured with mobile phone data. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 7(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00627-3

- Morchid, K., & O’Mahony, M. (2019). Transport sector impacts of a border between Ireland and Northern Ireland after a hard Brexit. Journal of Advanced Transportation, 2019, Article 9029852. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/9029852

- Moritz, M. (2011). The impact of Czech commuters on the German labour market. Prague Economic Papers, 20(1), 40–58. https://doi.org/10.18267/j.pep.386

- Nahrstedt, B. (2000). Legal aspect of border commuting in the Danish-German border region (Technical Report, IME Working Paper).

- Nonnenmacher, L., Baumann, M., le Bihan, E., Askenazy, P., & Chauvel, L. (2021). Cross-border mobility in European countries: Associations between cross-border worker status and health outcomes. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10564-8

- Novotný, L., & Böhm, H. (2022). New re-bordering left them alone and neglected: Czech cross-border commuters in German-Czech borderland. European Societies, 24(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2022.2029131

- Nowotny, K. (2010). Risk aversion, time preference and cross-border commuting and migration intentions (Technical Report, WIFO Working Papers).

- Nowotny, K. (2014). Cross-border commuting and migration intentions: The roles of risk aversion and time preference. Contemporary Economics, 8(2), 137–156. https://doi.org/10.5709/ce.1897-9254.137

- Orraca Romano, P. (2015). Immigrants and cross-border workers in the US-Mexico border region. Frontera Norte, 27(53), 5–34.

- Paccoud, A., Hesse, M., Becker, T., & Górczyńska, M. (2022). Land and the housing affordability crisis: Landowner and developer strategies in Luxembourg’s facilitative planning context. Housing Studies, 37(10), 1782–1799. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2021.1950647

- Paci, P., Tiongson, E. R., Walewski, M., & Liwiński, J. (2010). Internal labour mobility in Central Europe and the Baltic Region: Evidence from labour force surveys. The Labour Market Impact of the EU Enlargement: A New Regional Geography of Europe? 197–225.

- Parenti, A., & Tealdi, C. (2023). Don’t stop me now: Cross-border commuting in the aftermath of Schengen. B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy, 23(3), 761–806. https://doi.org/10.1515/bejeap-2022-0344

- Pierrard, O. (2008). Commuters, residents and job competition. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 38(6), 565–577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2008.04.003

- Pieters, M., de Jong, G., & van der Hoorn, T. (2012). Cross-border car traffic in Dutch mobility models. European Journal of Transport and Infrastructure Research, 12(2), 167–177.

- Pries, L. (2019). The momentum of transnational social spaces in Mexico-US migration. Comparative Migration Studies, 7(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-019-0135-5

- Renkow, M., & Hoover, D. (2000). Commuting, migration, and rural-urban population dynamics. Journal of Regional Science, 40(2), 261–287. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4146.00174

- Rodríguez, M., & Curlango Rosas, C. (2013). Ambient urban games for reducing the stress of commuters crossing the Mexico-US border. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 8276, 386–389.

- Romani, J., Suriñach, J., & Artís, M. (2003). Are commuting and residential mobility decisions simultaneous?: The case of Catalonia (Spain). Regional Studies, 37(8), 813–826. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340032000128730

- Rouwendal, J., & Meijer, E. (2001). Preferences for housing, jobs, and commuting: A mixed logit analysis. Journal of Regional Science, 41(3), 475–505. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4146.00227

- Sandow, E. (2008). Commuting behaviour in sparsely populated areas: Evidence from northern Sweden. Journal of Transport Geography, 16(1), 14–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2007.04.004

- Schiebel, J., Omrani, H., & Gerber, P. (2015). Border effects on the travel mode choice of resident and cross-border workers in Luxembourg. EJTIR Issue, 15, 570–596.

- Schmidt, T. (2005). Cross-border regional enlargement in Øresund. GeoJournal, 64(3), 249–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-006-6874-5

- Siim, P. M., & Assmuth, L. (2016). Mobility patterns between Estonia and Finland: What about the children? Cultural Patterns and Life Stories, 273–304.

- Soe, R.-M. (2018). Smart cities: From silos to cross-border approach. International Journal of E-Planning Research, 7(2), 70–88. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJEPR.2018040105

- Sohn, C. (2014). Modelling cross-border integration: The role of borders as a resource. Geopolitics, 19(3), 587–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2014.913029

- STATEC. (2020). L’impact des frontaliers dans la balance des paiements en 2019.

- Stone, A. A., & Schneider, S. (2016). Commuting episodes in the United States: Their correlates with experiential wellbeing from the American Time Use Survey. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 42, 117–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2016.07.004

- Stutzer, A., & Frey, B. S. (2008). Stress that doesn’t pay: The commuting paradox. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 110(2), 339–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9442.2008.00542.x

- Svensson, S., & Balogh, P. (2018). Limits to integration: Persisting border obstacles in the EU. In E. Medeiros (Ed.), European territorial cooperation. Urban Book Series (pp. 115–134). Springer.

- Tao, Y., Petrović, A., & van Ham, M. (2022). Commuting behaviours and subjective wellbeing: A critical review of longitudinal research. Transport Reviews, 43(4), 599–621. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2022.2145386

- Telve, K. (2018). Absent or involved: Changes in fathering of Estonian men working in Finland. Gender, Place and Culture, 25(8), 1257–1271. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2018.1450227

- Telve, K. (2019). Family involved or left behind in migration? A family-centred perspective towards Estonia-Finland cross-border commuting. Mobilities, 14(5), 715–729. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2019.1600885

- Terlouw, K. (2012). Border surfers and Euroregions: Unplanned cross-border behaviour and planned territorial structures of cross-border governance. Planning Practice and Research, 27(3), 351–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2012.670939

- Van Ommeren, J., Rietveld, P., & Nijkamp, P. (1997). Commuting: In search of jobs and residences. Journal of Urban Economics, 42(3), 402–421. https://doi.org/10.1006/juec.1996.2029

- Verplanken, B., Walker, I., Davis, A., & Jurasek, M. (2008). Context change and travel mode choice: Combining the habit discontinuity and self-activation hypotheses. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 28(2), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2007.10.005

- Wang, Q., & Hu, H. (2017). Rise of interjurisdictional commuters and their mode choice: Evidence from the Chicago metropolitan area. Journal of Urban Planning and Development, 143(3), 05017004. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)UP.1943-5444.0000381

- Wiesböck, L. (2016). A preferred workforce? Employment practices of East-West cross-border labour commuters in the central European region. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 41(4), 391–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11614-016-0245-3

- Wiesböck, L., & Verwiebe, R. (2017). Crossing the border for higher status? Occupational mobility of East-West commuters in the central European region. International Journal of Sociology, 47(3, SI), 162–181.https://doi.org/10.1080/00207659.2017.1335514