Abstract

Child participation has become a conscious goal for support services related to children and young people, but there is still uncertainty regarding how this can be facilitated. This study explores the value of children’s participation in research and is based on a “child-centred” approach to the early development of a participation tool called the “Sense of Empowerment Inventory for Children” (SEIC). The main finding in this study concerns both the specific changes that were proposed by the children and how this affected the quality of the tool, but also how the children’s involvement had an impact on understanding participation as a process. This study adds knowledge to a methodological approach that supports the value and benefit of including children in participatory processes in research.

The inclusion of children’s views and their opportunities for active participation in matters which concern them represent crucial principles and explicit work goals for support services and fields of practice related to children and young people. From a human rights perspective, child involvement is justified by Article 12 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), Citation1989), which advocates for children to promote their interests and views. The right to participation must also be viewed in the context of Article 3 of the UNCRC and the consideration of the child’s best interests, and child participation can be seen as a natural consequence of safeguarding children’s interests. Researchers who work with children and young people have established that adults do not always know what children know, understand or experience, and they may have different understandings of children’s needs and subjective views (Hunleth et al., Citation2022). This means that interventions and the implementation of research also require the children’s perspectives. Therefore, children are increasingly regarded as key stakeholders, with the right to contribute to discussions about how various services are made available to them (Clark et al., Citation2020). In this study, the significance of child participation in research is explored, in addition to how a child-centered approach can contribute to the development of an empowerment inventory for children. Although this article presents a collaborative project for the development of a participation tool, the article is primarily about the practice of engaging children to contribute to a collaborative research context to validate this tool. The article presents thus a discussion around the value of child participation through a practical example, and shows both what children can contribute alone, but mostly how a collaborative perspective on child participation can affect our understanding of child participation as a concept in the field of practice.

In recent years, an understanding of participation as co-production based on a social democratic ideology of cooperation and an opposition to a more hierarchical role in service design has emerged (Askheim, Citation2017). A distinction is often made between consultative and collaborative participation (Lansdown, Citation2018; Paulsen, Citation2016; Van Bijleveld et al., Citation2015), and few researchers see the (collaboration process/meaning-making) process in itself as the main goal for children’s participation (Skauge et al., Citation2021). Archard and Skivenes (Citation2009) problematize the concept of children “being heard” and emphasize child participation as conclusive in assisting an adult’s ability to make good decisions in the best interest of the child. This is related to “meaningful participation,” which concerns the quality of participation and the child’s sense of being heard and taken seriously (Dillon et al., Citation2016; Kennan et al., Citation2019). In addition, meaningful participation is also used to refer to children’s participation making a difference in decision-making, but the relational aspect underlines that child participation concerns more than decision-making. Child participation must therefore be seen not as something fixed to be extracted by the adult, but as a process, where the children’s (and the adult’s) points of view can be formed in interaction with each other and the context (Gulbrandsen et al., Citation2012; Skauge et al., Citation2021).

Although there are several theoretical frameworks and models that describe child participation as a concept, active participation by children and young people, especially in traditionally adult-led contexts, has nevertheless proved difficult to achieve (Kennan et al., Citation2021; Lundy, Citation2007; Shier, Citation2022; Van Bijleveld et al., Citation2021). Child participation as a concept is perceived by many as unclear and imprecise, and one that is often used without being sufficiently theorized or contextually explained and operationalized (Skauge et al., Citation2021; Tingstad, Citation2019; Vis et al., Citation2011). The large gap between the general perception of the importance of child participation and the lack of implementation in practice can therefore be explained by the different and unclear definitions and understandings of child participation (Skauge et al., Citation2021; Van Bijleveld et al., Citation2015). Several studies indicate that professionals lack competence regarding how it is carried out in practical implementation, especially in formal and professional proceedings, for instance in research, support relationships, pedagogical contexts or care situations (Lundy & O’Donnell, Citation2021; Rap et al., Citation2019; Tveitnes, Citation2018). To increase children’s opportunities for real and meaningful participation in practice, there is a need for more knowledge as well as tools and guidelines that can contribute to increasing professionals’ competence and professional confidence in such situations (Lundy, Citation2007). This has also been advocated by the Norwegian political agenda through work on proposals for a new Children’s Act (NOU, Citation2020, p. 14).

The significance of tools and inventories as implementation strategies

Structured forms and inventories (for example the Perceived Parental Autonomy Support Scale (P-PASS) (Mageau et al., Citation2015), the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE) (Jerusalem & Schwarzer, Citation1979) or sense of coherence scale (SOC-13) (Antonovsky, Citation1993)) can be useful tools for making knowledge available or creating a common understanding of a concept, as well as implementing new knowledge and developing fields of practice (Loewenthal & Lewis, Citation2018). A structured measurement tool of child participation could thus involve both a comprehension of child participation as a construction, contribute to the public discourse concerning the practical implementation of child participation by identifying key factors, and enable measurement and consequently testing of the psychometric properties of child participation as a construct. Thereby, it could support scholars as well as practitioners in quantifying children’s real preconditions for participation in proceedings and provide a basis for informed decisions and future strategies. A theory-based participation tool could thus be a support for professionals in relation to the inclusion of children in participation processes.

Lundy (Citation2007) has developed a model for child participation to be more easily operationalized and implemented in fields that work with children and young people. This has been widely used, including the Irish government. Lansdown and O’Kane (Citation2014) have also developed a toolkit for monitoring and evaluating child participation. This consists of a 6-part guide and is intended for use by practitioners and children working in participatory programmes, as well as other organizations that seek to assess and strengthen child participation in their wider society. Although both Lundy (Citation2007) and Lansdown and O’Kane (Citation2014) have provided a detailed toolkit that covers both methods, techniques, attitudes and behavior, there is a lack of a simple and systematic questionnaire that is based on the children’s own sense of participation. The children’s individual assessments of perceived participation will be an indication of the children’s real prerequisites for being an active contributor in participation processes, and a quality measure of the methods and instruments that help adults to facilitate child participation.

Co-validation of a participation tool through a child-centered approach

For an instrument to be useful and provide good information, it must be comprehended and interpreted as equally as possible by everyone who uses it. Sinclair et al. (Citation2002) find in one study that children interpret words differently, demonstrating the need to involve children at all stages of the process. In the development of structured tools especially, face validation is important (Churchill, Citation1979). The inclusion of an assessment phase to help ensure the face validity of scale items should not normally be a major burden on researchers, but can considerably improve the scales that become used (Hardesty & Bearden, Citation2004). In many cases, ad hoc quantitative inventories are applied in child services contexts without a thorough validity check by children (Hardesty & Bearden, Citation2004). This often due to a lack of knowledge as well as resource limitations (ibid). Face validity, which concerns the subjective perception of appearance, linguistic content and structure, is a rather simple process, but in the absence of good guidelines and method descriptions, researchers avoid performing it in a structural manner (Desai & Patel, Citation2020; Hardesty & Bearden, Citation2004). It involves assessing the subjective perception of appearance, linguistic content and structure that provides significant evidence for the validity of the survey and that must be scrutinized in any questionnaire before it is distributed to the sample of interest (Polit & Beck, Citation2006). To ensure the quality of a tool that is aimed at children, it would be natural to involve children in the development process to ensure face validity.

The development of an instrument for children should be based both on their needs and on what is useful for the field, while at the same time being a user-friendly tool that makes sense in daily practice. It is thus appropriate to use a child-centered approach to develop a convincing, intuitive, and easily adopted product. A child-centered approach is adapted from a human-/user-centred design (Lyon et al., Citation2019a; Norman & Draper, Citation1986), which is a framework for guiding the development of solutions for socially identified problems and shares the same common goal of improving the use of innovative and effective practice as implementation science (Lyon et al., Citation2019). Such a design represents a participatory approach and focuses on developing more usable innovations by systematically gathering input from stakeholders, improving stakeholder innovation, and adapting to the current context, with the aim of improving user-friendliness, reducing the burden, and increasing contextual appropriateness (Lyon et al., Citation2019a). A child-centered approach approaches problems from the child’s perspective, focusing on the child’s own experience. It also incorporates children’s voices and leadership, treats children as presumptively capable of participation rather than lacking in capacity, and embraces all children, considering their unique needs, as well as being inclusive, developmentally sound, and interdisciplinary, and bringing all relevant expertise to bear on the problems encountered by children and youth (Bennett Woodhouse, Citation2003). This kind of approach will maintain children’s interests and needs in the validation process and lead the adaptation of the tool to their contexts and needs.

The systematic face validation of questionnaires with children is not widespread in the research literature, and when it is performed it is often carried out through surveys (Klassen et al., Citation2022; Stjernqvist et al., Citation2021). Some researchers have nevertheless accomplished these processes through interviews or qualitative workshops (De Oliveira et al., Citation2022; Klassen et al., Citation2022). Lundy et al. (Citation2011) and Lundy and McEvoy (Citation2012) describe the work of a Children’s Research Advisory Group (CRAG) where children are invited to participate in projects as co-researchers and as a key stakeholder group who contribute their expertise in the research process. Although they do not describe this methodological approach in the context of the development and validation of surveys and tools, this working method has value as an example of a qualitative process that includes children. Such a method emphasizes a dynamic collaboration between children and adults/researchers, which adds an element of co-reflection with children as an expert group. Some authors describe child participation in the development of instruments (Kellett, Citation2011), but there is a lack of research-based literature that describes children’s involvement in qualitative validation processes in the development of structured surveys and inventories.

The aim of this study

As part of a larger project, a new inventory has been developed to assess children’s sense of empowerment as a significant methodological component for active and meaningful participation. This tool is aimed at formal processes involving children and adults, with a basic understanding of child participation as a collaborative approach. This article presents a qualitative co-validation process of this tool through a child-centered approach and highlights how the process of child participation can contribute to enhanced quality. This paper also discusses potential pitfalls with the involvement of children in such a process. The research question that is explored in this article is thus: what are the benefits and pitfalls of using a child-centered approach when developing a new inventory for assessing empowerment among children? The Sense of Empowerment Inventory for Children will serve as an example of such an inventory, with particular focus on the face validation process in this paper.

Method

Process

The face validation of the tool has been performed through a qualitative co-research process where a group of children were invited to an open and creative dialogue about the content and form of the tool. Their role was to ensure the inclusion of the child perspective in the development and implementation of this tool, and during four workshops the linguistic formulations of 26 preconstructed items, answer options, headings, specific adaptations for implementation and a common understanding of the content were discussed and reflected upon. The items were tested for usability through workshops with children, with a co-assessment of the appearance of the questionnaire in terms of feasibility, readability, consistency of style and formatting, and the clarity of the language used (DeVon et al., Citation2007; Haladyna & Hess, Citation1999; Trochim & Donnelly, Citation2001). With the help of children as co-researchers in a qualitative (face) validation process, the assessment was evaluated for clarity, unambiguity, reasonableness, and relevance (Desai & Patel, Citation2020). Clarity and unambiguity in an assessment form refer to the fact that the tool is not confusing in terms of comprehension and reading, and that it incorporates sufficient instructions. Relevance and reasonableness relate to whether appropriate questions are included for measuring the concepts of interest, and with a suitable degree of difficulty (Desai & Patel, Citation2020).

The workshops were led by the researcher and author of this article, who also set the agenda for the meetings, but the number of gatherings and activities were the result of a dynamic collaboration between the researcher and the children. In the implementation of the meetings, emphasis was placed on collaborative alliances as a strategic methodological practice (Olsen, Citation2022, Olsen et al. Citation2022). This approach enabled the children to experience a valuable role in the collaboration, as well as creating a safe framework and placing the children in the context of the problem through relevant information, in addition to emphasizing an open and exploratory approach to the assignment.

The aim and purpose of the workshops were presented as an issue relating to the researcher’s need for children’s involvement in the project, as well as the framework for the assignment: "Children have the right to be heard and taken seriously in matters that concern them, but this is not always easy to realize in the practical deed. There is thus a need to create a tool where children more easily can convey their experience of the conversation and their sense of participation in meeting with an adult. I have made a draft of this but need your help to make sure that the tool is understood in a correct way by children from the age of 12.” The workshops were arranged to take place in the evening in meeting rooms in a sports center after the children’s leisure activity. Each meeting lasted 60–75 minutes.

Participants and recruitment

The participants were recruited through a local handball team for girls aged 12, all of whom were students at the same school. We invited the whole team (15 girls) to participate, and seven girls signed up (aged 12–13). Some of these children had previously participated in after-school groups with the researcher, and this was seen as a strength in terms of building on already established relationships and safe collaborations. It was the children’s linguistic and interpretive experiences that were needed in this part of the study, and therefore the participants were mainly encouraged to discuss and convey their views as representatives of children as a social group. Although the group was recruited on a general basis, it was still composed of different experiences and bases for understanding, including experiences with special educational support systems, minority backgrounds and personal challenges in educational contexts.

Construction of the new empowerment tool

The tool is based on a conceptual empowerment model for children’s active participation in meetings with adults in professional roles and is called the Sense of Empowerment Inventory for Children (SEIC) (Olsen, Citation2022). The model is constructed by Olsen (Citation2022) and is based on the idea that children’s sense of empowerment is a prerequisite for being able to take an active role in participatory processes together with adults. Based on an operationalization of the model’s four dimensions: information, autonomy, recognition, and alliance, 26 items were designed as preparatory work for the project. This material was the basis for reflections and discussions around interpretation and common understanding, and the basic working material for the collaborative project with the children. The aim and purpose of the tool were discussed in relation to the children’s right to participate and experience of being heard and taken seriously, especially in a school context, and it was designed for children over 12 years of age.

Ethical assessments

The research was approved by the Norwegian Center for Research Data (project number 185950). Children were invited to contribute as co-researchers in the project, and received tailored information about it in both writing and an oral presentation. The researcher was available for questions and comments throughout the period, and the children were also informed that they could withdraw from the collaboration at any time. The parents were also notified and asked for consent.

In this work, it was important to consider the uneven power relationship that could affect the children’s experience of being able to express themselves freely, and arrangements were therefore made to prevent the children’s participation from remaining tokenistic. Emphasis was then placed on the practical facilitation in accordance with the four components that make up the conceptual empowerment model for active participation. That is, the children’s need for information about the project, goals and purpose for creating an action space for development was taken into account, all the children were encouraged to actively participate within an exploratory working method, all contributions were recognized and viewed as an important contribution to the overall discussion and reflection, and finally significance was given to establishing a real collaboration by clarifying the children’s significant role as an essential element for the finished product (Olsen, Citation2022).

At the start of this project, the children’s role was defined as being co-researchers and allies. They were therefore not considered informants to be researched on, but rather children who were to be included as a quality resource into the research work. Anonymisation was therefore not seen as necessary but was nevertheless a topic that was raised with the children in the process. The children had no qualms about their names being known in relation to the work. This article, on the other hand, discusses the collaborative process between the researcher and the children as co-researchers and contributors to the project, and therefore it was natural to keep the identity of the participants hidden in the work presented here. It is nevertheless a central topic to discuss the children’s co-authorship related to this type of participation. In a side project that resulted from this collaborative process, it was more natural to credit the children with authorship, as the children had contributed to both the research idea, data collection, analysis and production of the text. This project is not described in detail in this article but is mentioned under “findings.”

By using incentives in research projects, one can also place a value on the child’s participation and its significance in the process, which can raise the child’s “status.” In skewed power relationship, this could help to reduce the differences in sensed power, and in many cases could reduce any pressure that weakens volunteerism. In this project, a reward/payment was not promised to the participants, but they experienced that serving food at the meetings was a form of reward that they received for participating. At the end of the project, the participants nevertheless received a gift card of a smaller amount as a thank you for their participation, and to signal the importance they had for the project. Together with the gift card, they also received a closing letter with a brief summary of the project’s parts with an orientation on the research findings and knowledge development to which they have contributed. This information was also given as an oral presentation to the participants at the same time as we reflected on the process and the result.

Analysis

During the four workshops, a log was kept to document all changes and variations in reflections that emerged in the discussions. This has been used as a basis for analyzing the face validation process and the real changes that the children contributed to in the development of the tool. A qualitative content analysis of the field log for the work process has been employed to explore both the extent of the children’s real participation and influence in the process, as well as to examine the types of changes to which the children’s involvement contributed.

Comparative content analysis has been used (Krippendorff, Citation2012) to identify changes from the 26 preconstructed items in the tool to the edited version after the co-research process with the children. These modifications were then analyzed through a conventional approach where a systematic review is used to classify and identify themes and patterns in the data (Fauskanger & Mosvold, Citation2014; Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). The aim of this was to be able to describe and understand in what way the children contributed to the development of the instrument. This process was carried out in three steps. Initially, the notes and the log were read and the units of meaning that dealt with the specific contributions and changes that the children contributed to in the discussions around the content were identified. These elements (units of meaning) were then inserted into a table and compared with the original version. These changes were then evaluated through conventional content analysis where the goal was to describe variations and explore the essence of these changes. The analysis was completed manually as the empirical material was relatively limited.

Findings

A summary of the children’s contributions in the co-research workshops shows that the children made significant changes to the research material. 12 of the 26 preconstructed items (46%) were reformulated and adjusted as a result of the collaborative research process. The content analysis showed that the changes can be categorized into four different types of changes; content correction (three), word comprehension (two), content comprehension (two), and content clarification (five) (presented in ).

Table 1. An overview of the changes made to the items in the SEIC (Some of the meanings in the descriptions may have been lost in translation when the items and the children’s language changes have been translated from Norwegian to English.).

In addition to the changes in the 26 items, the children also contributed to an assessment of the introduction and information, as well as answer options, headings, pilot testing and an additionally structured evaluation of the content validity of the tool. These results were evaluated qualitatively and involved reducing unnecessary text to promote children’s motivation to participate, edit unclear text and test feasibility. A summary of this is provided in .

Table 2. An overview of the changes made the tool’s structure, content, and implementation value.

The children’s involvement related to the topic and the project’s goals and purpose were also important elements that provided information about both the topic’s relevance and content validity and assisted in adjusting the tool and the research project in the right direction. Some of the items were highlighted as particularly important for children’s conversations with adults, and as core items for this issue (2, 9, 13, 14, 17, 18 and 19). None of the items were considered irrelevant and thus removed. This qualitative content assessment eventually became the basis for a separate quantitative/structured study that was carried out with systematic content validation as a result of the collaboration with the children. This research is not further described in this paper.

The analysis of the children’s input and changes showed that in three of the 26 items a correction was made to the content of the text, so that the focus in the text became more in line with what the item was intended to ask for. For example, “I know what the adult from EPS can help me with” to “I feel that I have been told what the task of the adult in EPS is.” The children’s input resulted in more explanatory content so that the understanding of the item better captured the intention. This contributed to increasing the clarity and the probability of valid answers in the use of the form. Two of the changes that were made involved word comprehension, where the children thought that other terms were more meaningful to use in this context. The words that were originally used could be difficult to understand or interpreted differently to how they were intended. For example: “I wish the adult had explained more what the intention of the meeting was,” became “I wish the adult had explained more what the purpose of the meeting was.” This revision increased the unambiguity and the probability of measuring the same aspect from each respondent. Two of the changes that were made related to the unclear meaning of the sentence itself, and these sentences were reformulated to clarify the meaning associated with the relevant context. For example: “I felt that I and the adult complemented each other well” was changed to “I felt that I and the adult helped each other understand how to deal with the problem.” A correction of the item’s wording then assisted in increasing the clarity so that the children were more likely to understand the meaning of the item, increasing the validity of the tool. The last form of change involved adjustments that specified the content of the item. When working with these items, the children understood what the meaning of the text was, but they suggested other ways of formulating it to avoid misunderstandings and misinterpretations. Five of the items involved this, such as: “I felt that the adult liked me.” This sentence was especially important to correct as all the children thought that this was a very unfortunate statement that would have the opposite meaning in a questionnaire context. While the researchers believed that this was a quality factor for the dimension recognition, this sentence was interpreted by the children as if the adult were “in love” with the child—which had a completely different meaning. The sentence was therefore changed to “I felt that the adult liked to talk to me” to create a more unambiguous and clear understanding of the item.

This systematic collection of input from the children allowed the tool to be adapted to this age group as respondents. Through a common goal of developing and improving a tool that facilitated the chance for children to promote their views and engage in real opportunities for participation in matters that concern them, the instrument was developed by the children themselves, who were able to assess the instrument’s validity and contribute changes and improvements.

Discussion of the impact of a child-centered approach

Child participation has received great attention in recent years and the significance of including children in participatory processes is considerable. Participation is advocated for both as a right and as a useful value, but the dynamic co-reflective development process itself is an important part of promoting meaningful and real participation. By analyzing the changes that the children contributed to through the qualitative collaboration, the impact of the children’s involvement in the process could be highlighted.

Adaptation to the children’s needs and understanding

The collaborative process with the children provided an opportunity to revise and develop the tool and consider the children’s understandings and needs while the tool retained its research property through the researcher’s contribution. The children’s reflections and understandings together with the researcher’s professional framework contributed in a dynamic interaction to a more thorough assessment of the form and greater significance of the various components. In this process, space is created for the children to practise important reasoning skills and to formulate and share their opinion with others, which Fitzgerald et al. (Citation2009) and Collins et al. (Citation2017) present as important arguments for child participation. Compared to a structured survey approach to validation, a collaborative approach, with its dynamic qualities, concerns co-reflection that affects both parts to a greater extent. We thus understand the importance of a collaborative approach, as Archard and Skivenes (Citation2009) argue, so that the children can help adults make decisions that are in line with the children’s needs and daily realities. Building on Shaw et al. (Citation2011), this ensures that the tool is relevant and appropriate for children of the same age and situation as the ones in this project. The use of a child-centered approach was thus advantageous in confirming, rephrasing, and adapting the tool based on feedback from children in the selected age group. This qualitative review highlighted several different understandings in the assessment of the tool, which provided an insight into the children’s frame of interpretation so that the tool could be adapted to their needs and comprehension. The findings in this study were consistent with Hardesty and Bearden (Citation2004) arguments for the importance of face validation, as well as those of Lyon et al. (Citation2019a), which describe a human-/user-centred design as a basis for the development of improved user-friendliness, a reduced burden and increased contextual appropriateness.

Co-reflection—A relational aspect

The changes were thus the result of a co-research and a co-creation process based on both the children’s and the adult’s ideas and suggestions. The research process that was used in this context requires little training, but allows for “all” children, regardless of their circumstances, to be included in such a process. This opened the possibility of a more diverse participation and a greater level of children’s support and contribution, and it considers the support children need to shape and express their opinions. In this process, it was important to be conscious of not schooling the children according to adults’ expectations (the context of their upbringing/expecting them to think like adults), but to promote children’s perspectives as a complement to the adult’s knowledge. Gulbrandsen et al. (Citation2012) and Skauge et al. (Citation2021) believe that child participation must be viewed as a process where adults and children together develop an understanding with inspiration from each other and the context in which they operate. This means that the qualitative discussion between adults and children may be able to consider the idea that knowledge, opinions, and understandings develop in interaction with the explanations and issues that are recorded from the other participants in the collaboration “team.” This provided a basis for the children to shape their views and ideas, as well as giving the adults more space to understand the child’s opinions based on the relevant context.

Through the collaboration and joint reflections related to the assignment, the interests of both the children and the adults could be incorporated and shaped so that the finished result was a product of both interests. This refers to a meaningful form of participation where the goal is the (collaborative) process and its consequences (Dillon et al., Citation2016; Kennan et al., Citation2019). In such a process, no emphasis is placed on the children’s decision-making as a goal in itself, and the children are not heard separately from the context. The collaborative process therefore calls for a quality assessment that could not have been achieved by one or the other part alone or separately.

Decisive changes or cosmetic measures?

It is nevertheless suitable to ask a critical question about how much influence the children’s participation has really had on the development of this form, as well as whether there were decisive changes, or only cosmetic measures. A face validation is, according to Churchill (Citation1979), a simple and non-deterministic form of validation, and not enough to obtain a quality-assured usable instrument. Several validation processes are required. Based on the analyses, it is evident that the children’s involvement has led to many changes concerning both the interpretations and explanations of words, and refinements and changes to content. In addition to these measurable changes, the co-reflection process is also significant for the adult researcher’s prerequisites for making good and considerate decisions (Archard & Skivenes, Citation2009). This applies both to understanding what needs the children have for the preparation and implementation/completion of such an instrument, how they have understood the topic, and how such a research project can be carried out with children. Several researchers (Skauge et al., Citation2021; Tingstad, Citation2019; Vis & Thomas, Citation2009) highlight the unclear meaning of what child participation is and how it is facilitated in practice. Through the children’s assessment of the various elements out of the theme and context, an evaluation of the content’s relevance as well as of what child participation entails in practice are made. A child-centered approach can therefore be important for translating a theoretical intention into concrete conceptualization and operationalization.

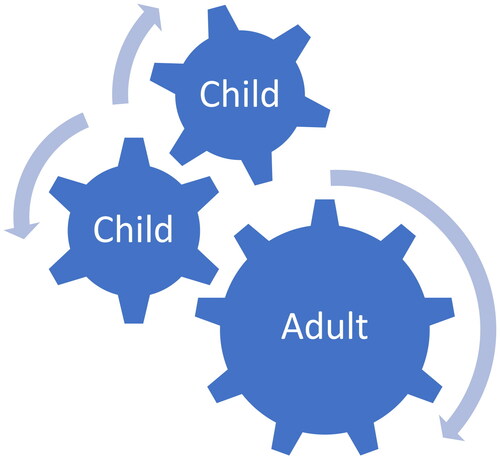

Through the qualitative discussions the researcher also gained a significant insight into the children’s commitment to the topic and their views, their reflections on what motivates their engagement, and which elements they think are important or unclear. These are valuable consequences of the dynamic and dyadic interaction with the children as collaborators in the development of this instrument, which would not have been obtained without their participation in the process. The qualitative co-creation process therefore became an important element for the qualitative development of the project and the instrument, as well as in the validation process. This is an example of what Gulbrandsen et al. (Citation2012) and Skauge et al. (Citation2021) describe in terms of how adults and children can complement each other and stimulate increased participation and contribution in such collaborative processes. In a participatory machinery, the various participants will act as cogwheels with their own significant functions for the collaboration ().

The same effect would have been difficult to generate alone. The question of how much the children alone have contributed thus becomes less important, but what matters more is the joint process that both adults and children have undergone, which involves mutual orientation, inspiration, understanding and influence. In a qualitative dynamic dialogic and dyadic context, adults can facilitate the children’s contribution to the process to be more targeted and meaningful, and in this way appeal to a greater level of real participation through collaboration. The adult can in this position assist the children in gaining understanding into how they can contribute and what type of knowledge is needed, and space can be opened for (co-)reflection and the development of their own views and opinions. This dynamic collaborative understanding of participation generates the possibility that not only can the children develop their thoughts, ideas and thus contribute to the process, but also that the adult in joint reflection with the children can develop their understanding of the requirements that increase the quality of the tool. This provides a deeper and more thorough exploration of opportunities and needs, as well as the assessment of the choices made in the process.

Meaningful participation

Some of the issues involved in such an approach concern the limitations or obstacles related to skewed power differences between adults and children, as well as the challenges encountered when having to perform in an unfamiliar context, in addition to what extent the children should be involved in the process. When Archard and Skivenes (Citation2009) discuss meaningful participation, they emphasize that it is not enough that the children ‘are heard’, but that what the children contribute must be of importance to the case itself. This can influence the feeling of power disposition and the different roles in such an adult-child collaboration. In this project, the adult already had a pre-made draft to a tool intended for children, and the task that the children were to help with was to discuss this from their perspectives and understandings. The adult’s contribution was therefore already demonstrably insufficient, and the children had the assignment of correcting/assessing it from their perspective. Bennett Woodhouse (Citation2003) describes a child-centered approach as a method that incorporates the children’s voices and treats the children based on a confidence in their capacity. This approach emphasizes that the children’s needs and views lead the process, which can highlight the value of the children’s contribution compared to the adult’s one. The children’s autonomous voice in such a qualitative child-centered process will thus be given greater space than if there had been less emphasis on a dynamic and collaborative approach. Through this assignment, the adult opened for increasing the children’s power from the start, and the roles were more “equal.” Even though the roles between children and adults can rarely be completely equal (and perhaps should not be either), the co-validation process and the collaboration between adults and children created an opportunity to utilize the potential and capacity of the children’s resources. To prevent the participating children experiencing the situation as limited through an adult-controlling context, a natural and organic participation can more easily take place through a qualitative and dynamic process. The children’s contribution thus becomes more authentic and real through the fact that the collaborative process facilitates an exploratory approach that does not emphasize right and wrong, but on improving the tool based on the children’s own assessments.

Limitations

This study was conducted in a Norwegian context and the elements in the tool were originally in Norwegian. Some of the nuances and meanings in the linguistic formulations may therefore have been lost in translation and do not represent the tool’s final English-language version. These details nevertheless became secondary as the SEIC in this article functioned as an example of a child-centered approach that included child participation in a co-research process. The focus of this article is therefore on which type of changes were made and the co-creation process that affected this.

This paper presents a case study with seven Norwegian girls linked to the same school, leisure activity, and relatively similar socio-economic status. This must be considered in the transfer of these experiences to general knowledge. It nevertheless presents a valuable example of how child participation can be carried out in practice and the potential of such collaborations. This study is linked to a specific case and presents a participation process with girls aged 12-13. The transfer value to other situations is thus limited, and it is not discussed how this type of participation process can consider, for example, age, maturity, gender or socio-cultural conditions. This article nevertheless contributes by exemplifying how children can contribute to the development and validation of structured tools.

Concluding remarks

This study discusses the impact of child participation in research, and how this can contribute to enhanced value in a validation process for structured tools. The purpose of this investigation was to discuss and report on the significance of child participation in a validation process in the development of a new empowerment tool (SEIC). By inviting children to take part in a participatory process, children and adults have reflected together and collaborated on the tool’s clarity, unambiguity, reasonableness, and relevance related to the intention and implementation of the tool. This was accomplished in a dynamic interaction between the children’s interests, thoughts and needs on the one hand, and the research-related and thematic considerations on the other. The findings revealed that a child-centered approach to a qualitative face validation process led to several changes based on the children’s assessments of the adult’s preparation.

The experiences from this project show that children’s participation can be understood as a dynamic and dyadic process where the children’s knowledge and skills complement those of the adults. A process understanding of participation allows for the inclusion of children regardless of age, function, experiences, and prior knowledge, and is important for being able to understand children’s views from the relevant context. The finished “product” is therefore a product of both parts interest and engagement and gives the adult the conditions to make good and considerate decisions. A collaborative understanding of participation involves mutual orientation, inspiration, understanding and influence, and opens for a more thorough exploration of opportunities and needs. Participation will thus mean moving from an adult-controlled context to a qualitative and dynamic process where children have an increased sense of empowerment.

Child participation in the development of structured tools is little methodologically described in formal collaborative relationships with adults, but the importance of using user-centred methods to develop more usable innovations through systematic collection of input has been suggested (Bennett Woodhouse, Citation2003; Lyon et al., Citation2019a). A co-research process with children as experts in assessing the tool’s appearance can thus be an essential step for the tool’s validation and implementation value for children as a user group, although more work remains in terms of determining the reliability and validity of this instrument. This approach highlights children’s right to participation through the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC),) (Citation1989), and sheds light on the usefulness of active participation with children in research.

Facilitating children’s autonomous voices requires time and support to form one’s views, and this is difficult in a survey context. It necessitates more than giving the children ‘a microphone stand’ but involves instead facilitating participation through collaboration with the adult. These are arguments against developing and using a structured questionnaire in the work of mapping children’s experience of empowerment and participation, and perhaps this questionnaire is not intended to be the decisive element itself so that the children can have their say but is more intended to clarify key factors for facilitating participation such as knowledge dissemination and opportunities for practice development for the adults. In addition, such a tool could also be used to a certain extent to survey on a larger scale whether services meet the facilitation for participation, results that can also be compared across different services and subject areas, as well as help to measure the effect of intervention projects that intend to increase children’s sense of participation.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank all the young people who participated in this research project for their time and commitment. I would also like to thank the supervisors and colleagues at the Department of Education and Lifelong Learning, NTNU for valuable advice and feedback in the process.

Disclosure statement

No possible conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Antonovsky, A. (1993). The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Social Science & Medicine, 36(6), 725–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(93)90033-z

- Archard, D., & Skivenes, M. (2009). Hearing the child. Child & Family Social Work, 14(4), 391–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2008.00606.x

- Askheim, O. P. (2017). Brukermedvirkningsdiskurser i den norske velferdspolitikken. Tidsskrift for velferdsforskning, 20(2), 134–149. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.2464-3076-2017-02-03

- Bennett Woodhouse, B. (2003). Enhancing children’s participation in policy formulation. Arizona Law Review, 45, 750–763.

- Churchill, G. A., Jr. (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224377901600110

- Clark, H., Coll-Seck, A. M., Banerjee, A., Peterson, S., Dalglish, S. L., Ameratunga, S., Balabanova, D., Bhan, M. K., Bhutta, Z. A., Borrazzo, J., Claeson, M., Doherty, T., El-Jardali, F., George, A. S., Gichaga, A., Gram, L., Hipgrave, D. B., Kwamie, A., Meng, Q., … Costello, A. (2020). A future for the world’s children? A WHO–UNICEF–Lancet Commission. The Lancet, 395(10224), 605–658. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32540-1

- Collins, T. W., Grineski, S. E., Shenberger, J., Morales, X., Morera, O. F., & Echegoyen, L. E. (2017). Undergraduate research participation is associated with improved student outcomes at a Hispanic-serving institution. Journal of College Student Development, 58(4), 583–600. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2017.0044

- De Oliveira, C., Firmino, R., De Morais Ferreira, F., Vargas, A., & Ferreira e Ferreira, E. (2022). Development and validation of the quality of life in the neighborhood questionnaire for children 8 to 10 years of age (QoL-N-Kids 8–10). Child Indicators Research, 15(5), 1847–1870. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-022-09944-2

- Desai, S., & Patel, N. (2020). ABC of face validity for questionnaire. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences Review and Research, 65(1), 164–168. https://doi.org/10.47583/ijpsrr.2020.v65i01.025

- DeVon, H. A., Block, M. E., Moyle-Wright, P., Ernst, D. M., Hayden, S. J., Lazzara, D. J., Savoy, S. M., & Kostas-Polston, E. (2007). A psychometric toolbox for testing validity and reliability. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 39(2), 155–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00161.x

- Dillon, J., Rickinson, M., & Teamey, K. (2016). The value of outdoor learning: Evidence from research in the UK and elsewhere. In J. Dillon (Ed.), Towards a convergence between science and environmental education (pp. 193–200). Routledge.

- Fauskanger, J., & Mosvold, R. (2014). Innholdsanalysens muligheter i utdanningsforskning. Norsk pedagogisk tidsskrift, 98(2), 127–139. https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1504-2987-2014-02-07

- Fitzgerald, R., Graham, A., Smith, A., & Taylor, N. (2009). Children’s participation as a struggle over recognition. In B. Percy-Smith & N. P. Thomas (Eds.), A handbook of children and young people’s participation (pp. 315–327). Routledge.

- Gulbrandsen, L. M., Seim, S., & Ulvik, O. S. (2012). Barns rett til deltakelse i barnevernet: Samspill og meningsarbeid. Sosiologi i Dag, 42(3–4), 54–78. http://ojs.novus.no/index.php/SID/article/view/1019.

- Haladyna, T., & Hess, R. (1999). An evaluation of conjunctive and compensatory standard-setting strategies for test decisions. Educational Assessment, 6(2), 129–153. 53. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326977EA0602_03

- Hardesty, D. M., & Bearden, W. O. (2004). The use of expert judges in scale development: Implications for improving face validity of measures of unobservable constructs. Journal of Business Research, 57(2), 98–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(01)00295-8

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Hunleth, J. M., Spray, J. S., Meehan, C., Lang, C. W., & Njelesani, J. (2022). What is the state of children’s participation in qualitative research on health interventions?: A scoping study. BMC Pediatrics, 22(1), 328. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-022-03391-2

- Jerusalem, M., & Schwarzer, R. (1979). The general self-efficacy scale (GSE). Acessado 12 (03), 2007. Disponível: www.healthpsych.de.com.

- Kellett, M. (2011). Empowering children and young people as researchers: Overcoming barriers and building capacity. Child Indicators Research, 4(2), 205–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-010-9103-1

- Kennan, D., Brady, B., & Forkan, C. (2019). Space, voice, audience and influence: The Lundy model of participation (2007) in child welfare practice. Practice, 31(3), 205–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503153.2018.1483494

- Kennan, D., Brady, B., Forkan, C., & Tierney, E. (2021). Developing, implementing and critiquing an evaluation framework to assess the extent to which a child’s right to be heard is embedded at an organisational level. Child Indicators Research, 14(5), 1931–1948. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-021-09842-z

- Klassen, A. F., Rae, C., Gallo, L., Norris, J. H., Bogart, K., Johnson, D., Van Laeken, N., Baltzer, H. L., Murray, D. J., Hol, M. L. F., O, T., Wong Riff, K. W. Y., Cano, S. J., & Pusic, A. L. (2022). Psychometric validation of the FACE-Q craniofacial module for facial nerve paralysis. Facial Plastic Surgery & Aesthetic Medicine, 24(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1089/fpsam.2020.0575

- Krippendorff, K. (2012). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. SAGE Publications.

- Lansdown, G., & O’Kane, C. (2014). A Toolkit for Monitoring and Evaluating Children’s Participation—Introduction (No. 1; A Toolkit for Monitoring and Evaluating Children’s Participation). Save the Children. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/ME_toolkit_Booklet_1.pdf

- Lansdown, G. (2018). Conceptual framework for measuring outcomes of adolescent participation. 1–23. Accessed 07.10.2022. https://www.unicef.org/media/59006/file.

- Loewenthal, K., & Lewis, C. A. (2018). An introduction to psychological tests and scales. Psychology Press.

- Lundy, L. (2007). ‘Voice’ is not enough: Conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. British Educational Research Journal, 33(6), 927–942. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920701657033

- Lundy, L., & McEvoy, L. (2012). Children’s rights and research processes: Assisting children to (in) formed views. Childhood, 19(1), 129–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568211409078

- Lundy, L., McEvoy, L., & Byrne, B. (2011). Working with young children as co-researchers: An approach informed by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Early Education & Development, 22(5), 714–736. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2011.596463

- Lundy, L., & O’Donnell, A. (2021). Partnering for child participation: Reflections from a policy-maker and a professor. In D. Horgan & D. Kennan (Eds.), Child and youth participation in policy, practice and research (pp. 15–29). Routledge.

- Lyon, A. R., Koerner, K., & Chung, J. (2019). How implementable is that evidence-based practice? A methodology for assessing complex innovation usability [Paper presentation]. Proceedings from the 11th Annual Conference on the Science of Dissemination and Implementation, Washington, DC. Implementation Science, Vol. 14, 878. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0878-2

- Lyon, A. R., Munson, S. A., Renn, B. N., Atkins, D. C., Pullmann, M. D., Friedman, E., & Areán, P. A. (2019a). Use of human-centered design to improve implementation of evidence-based psychotherapies in low-resource communities: Protocol for studies applying a framework to assess usability. JMIR Research Protocols, 8(10), e14990. https://doi.org/10.2196/14990

- Mageau, G. A., Ranger, F., Joussemet, M., Koestner, R., Moreau, E., & Forest, J. (2015). Validation of the Perceived Parental Autonomy Support Scale (P-PASS). Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 47(3), 251–262. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039325

- Norman, D. A., & Draper, S. W. (1986). User centered system design: New perspectives on human-computer interaction. L Erlbaum Associates.

- NOU. (2020). 14. Ny barnelov—Til barnets beste. Barne- og familiedepartementet. Accessed 07.10.2022. Download from https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/nou-2020-14/id2788399/?ch=1.

- Olsen, R. K. (2022). “Now I understand why she needs our help”: A qualitative case study on collaborative alliances with children in research. The International Journal of Children’s Rights, 30(4), 990–1020. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718182-30040007

- Olsen, R. K., Stenseng, F., & Kvello, Ø. (2022). Key factors in facilitating collaborative research with children: A self-determination approach. Academic Quarter, (24), 135–148. https://doi.org/10.54337/academicquarter.vi24.7256

- Paulsen, V. (2016). Ungdommers erfaringer med medvirkning i barnevernet. Fontene forskning, 1(2016), 4–15.

- Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2006). The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Research in Nursing & Health, 29(5), 489–497. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20147

- Rap, S., Verkroost, D., & Bruning, M. (2019). Children’s participation in Dutch youth care practice: An exploratory study into the opportunities for child participation in youth care from professionals’ perspective. Child Care in Practice, 25(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2018.1521382

- Shaw, C., Brady, L. M., & Davey, C. (2011). Guidelines for research with children and young people. National Children’s Bureau Research Centre.

- Shier, H. (2022). How is it that young people do not have a more prominent seat at the decision-making table? International Journal of Youth-Led Research, 1(1), 1–3 (Inaugural Issue). https://doi.org/10.56299/oxu976

- Sinclair, R., Cronin, K., Lanyon, C., Stone, V., & Hulusi, A. (2002). Aim high stay real: Outcomes for children and young people: The views of children, parents and practitioners. Children and Young People’s Unit.

- Skauge, B., Storhaug, A. S., & Marthinsen, E. (2021). The what, why and how of child participation—A review of the conceptualization of “child participation” in child welfare. Social Sciences, 10(2), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10020054

- Stjernqvist, N. W., Elsborg, P., Ljungmann, C. K., Benn, J., & Bonde, A. H. (2021). Development and validation of a food literacy instrument for school children in a Danish context. Appetite, 156, 104848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.104848

- Tingstad, V. (2019). Hvordan forstår vi barn og barndom? Nordisk tidsskrift for pedagogikk og kritikk, 5(0), 96. https://doi.org/10.23865/ntpk.v5.1512

- Trochim, W. M., & Donnelly, J. P. (2001). Research methods knowledge base (Vol. 2). Atomic Dog.

- Tveitnes, M. S. (2018). Sakkyndighet med mål og mening: En analyse av sakkyndighetens institusjonaliserte kjennetegn; et grunnlag for refleksjon og endring. http://hdl.handle.net/11250/2499868

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). (1989). Assembly, U. G. United Nations Treaty Series 1577(3), 1–23.

- Van Bijleveld, G. G., de Vetten, M., & Dedding, C. W. (2021). Co-creating participation tools with children within child protection services: What lessons we can learn from the children. Action Research, 19(4), 693–709. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750319899715

- Van Bijleveld, G. G., Dedding, C. W., & Bunders‐Aelen, J. F. (2015). Children’s and young people’s participation within child welfare and child protection services: A state‐of‐the‐art review. Child & Family Social Work, 20(2), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12082

- Vis, S. A., Strandbu, A., Holtan, A., & Thomas, N. (2011). Participation and health—A research review of child participation in planning and decision‐making. Child & Family Social Work, 16(3), 325–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2010.00743.x

- Vis, S. A., & Thomas, N. (2009). Beyond talking—Children’s participation in Norwegian care and protection cases: Ikke bare snakk–barns deltakelse i Norske barnevernssaker. European Journal of Social Work, 12(2), 155–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691450802567465