Abstract

Teacher librarians (TLs) play a central role in developing students’ information literacy capabilities, which are vital for effective participation in formal education and active engagement in society. This research enhances insights into information literacy instruction in Australian secondary schools, by investigating the perceptions of practicing TLs regarding the information literacy needs of teachers and students. This article presents the groundwork for this investigation, employing a phenomenological approach and discussing findings from an initial survey. The study will inform TL education and improve current information literacy education practices, addressing the demand for nurturing 21st century skills embedded in the Australian Curriculum.

Introduction

Proficiency engaging with the rapidly evolving information landscape is not innate for either students or teachers (Becker, Citation2022). Hence the imperative to support Teacher Librarians (TLs), for whom a core responsibility is to foster the development of information literate students, able to locate and use information responsibly and ethically as learners and citizens (ALIA & ASLA, Citation2016; IFLA, Citation2021). Possessing strong information literacy capabilities is a necessary attribute that not only supports participation in formal education but also informed decision making in a range of everyday life contexts (Polizzi, Citation2020; Shuhidan et al., Citation2021; Taala et al., Citation2019).

While there exists some research that investigates information literacy in secondary education through contextual frameworks and comparison of recognized information literacy models, there is far less attention directed to stakeholders’ perceptions of information literacy in this context (Taylor & Digiacomo, Citation2023). This study seeks to bridge this identified research gap by exploring how Australian secondary TLs perceive the information literacy needs of teachers and students. Exploring this area will enhance current knowledge regarding the instruction of information literacy in Australian secondary schools, acknowledging the dynamic nature of information access, evaluation, and utilization. In doing so, it will contribute to improved TL education and will advance the existing pedagogical approaches within both the Australian educational context and globally. The anticipated outcomes of this research will assist educators to more effectively meet requirements to cultivate 21st century skills, the abilities and attributes that are critically necessary for positive engagement with contemporary work and life (Global Partnership for Education, Citation2020).

This study employed phenomenology to examine how practicing secondary TLs in Australia perceive the information literacy needs of students and teachers in the changing information landscape. Our specific research questions included the following:

To what extent do Australian Teacher Librarians engage with students and teachers regarding information literacy awareness and capabilities and has this changed over their time as a Teacher Librarian?

What changes in the information landscape do Australian Teacher Librarians identify and how have these influenced their beliefs about the purpose of information literacy?

Data was gathered through a combination of surveys and interviews. This article discusses the findings of the survey (Appendix A), which established the extent to which TLs have observed and experienced changes in the information landscape during their time as a TL, and the impact of these changes on their own, students’ and teachers’ interactions with information and their information literacy needs.

Literature review

The research team considered it necessary to identify how TLs define the concept of information literacy and its relation to everyday decision-making contexts as a foundation for further study concerning how information literacy is taught. To situate this research, the literature review investigated scholarly definitions of information literacy, the nature of information literacy instruction in schools, and the perceptions of information literacy held by teacher librarians as described in the literature.

Definitions of information literacy

Efforts to define and express the concept of information literacy have been described as “a conundrum” (Lloyd, Citation2017, p. 91), split across the diverging spaces of research and practice (Hider et al., Citation2019; Julien & Williamson, Citation2011; Lloyd, Citation2017). Theoretical definitions tend to highlight the socially situated nature of information literacy; recognizing how information practices are embedded within particular contexts; thereby being socially constructed and continually responsive to changing information landscapes (Bruce, Citation1997; Hepworth et al., Citation2014; Lloyd, Citation2010; Lupton & Bruce, Citation2010). Practitioners, challenged with the task of teaching information literacy have historically defined information literacy through a skills-based lens, focusing on how individuals cultivate information handling abilities (Julien & Williamson, Citation2011).

Stronger emphasis on constructivist pedagogy and the development of critical librarianship have gone some way to close this perceived gap between theory and process (Schachter, Citation2020). Recent definitions of information literacy combine descriptions of skills as well as recognition of the impact of context. This can be seen in the comprehensive definition put forward by Lanning and Gerrity (Citation2022, p. 6):

Information literacy is the ability to recognize and answer an information need across various contexts by engaging critical thinking to formulate questions; responsibly gather information representing diverse perspectives; and evaluate, manage, synthesize, and ethically share information. Information literacy supports the creation of new knowledge to facilitate lifelong learning and informed participation in a global information society.

Information literacy is the ability to think critically and make balanced judgements about any information we find and use. It empowers us as citizens to develop informed views and to engage fully with society.

Information literacy and school education

Much of the research focusing on the teaching of information literacy relates to higher education and academic librarians (Hicks & Lloyd, Citation2021; Rath, Citation2022; Schachter, Citation2020; Tewell, Citation2015). However, the development of information literacy should begin in the primary years, as “information literacy requires sustained development throughout all levels of formal education, primary, secondary and tertiary” (Bundy, Citation2004, p. 6). Reflective on the findings of Hicks et al. (Citation2023), a significant number of investigations of information literacy within the school context take an instrumental view, evaluating students’ information literacy skill levels (Al-Qallaf & Aljiran, Citation2022; Kankam, Citation2023; Majid et al., Citation2020; Moto et al., Citation2018). Fewer articles embrace a broader notion, with Zhu et al. (Citation2019) asserting that no previous research had been conducted to evaluate the influence of personal, behavioral, and contextual factors on students’ information literacy. In their study, the researchers linked aspects of information literacy to factors associated with interest in and use of information and communication technology (ICT), along with self-efficacy, and noted that the research did not comprehensively encompass the intricate and multifaceted nature of information literacy as a whole (Zhu et al., Citation2019).

A second focus area of research is equally skills-based, exploring the transfer of skills between high school and tertiary education (Dolničar et al., Citation2020; Saunders et al., Citation2017; Smith et al., Citation2013). The findings of several papers suggest stronger collaboration between high school and higher education is needed to ensure that during the transition, information literacy skills are carried over (Anderson-Story et al., Citation2014; Martin et al., Citation2017; Saunders et al., Citation2017). However, the limited transfer is also potentially due to discrepancies in what is emphasized during information literacy instruction, and fundamental differences in how information literacy is understood between high school and higher education (Saunders et al., Citation2017; Smith et al., Citation2013). The diversity of conceptualizations of information literacy was underscored by the research of Taylor and Digiacomo (Citation2023), who confirmed that there appears to be limited consensus regarding information literacy between various school stakeholders—including teachers, students, administrators, and parents. The conclusion was drawn that diverse understandings reflect the range of specific information landscapes, values and practices of each group. This implies the necessity of clearly defining the concept of information literacy when it is referenced within a school environment to facilitate collaboration and discussions.

Teacher librarians’ perceptions of information literacy

It is generally accepted that information literacy is an important element of 21st century learning (Australian Government Department of Education, Citation2022; Chalkiadaki, Citation2018; Geisinger, Citation2016) and is often clustered with related literacies including digital literacy and media literacy (Fantin, Citation2010; Mammadova, Citation2022). The proliferation of channels through which students access information and concerns about the impact of mis-, dis-, and mal- information has led to expectations that schools scaffold students’ skills to navigate the complex information landscape (Farmer, Citation2019; Johnston, Citation2020; Jones-Jang et al., Citation2021; Koltay, Citation2011; Lamb, Citation2017; Notley & Dezuanni, Citation2018). Despite this, collaboration between teachers and TLs may be limited by lack of time and support, and research indicates that overall teachers’ confidence and competence in teaching information literacy appears limited (Amram et al., Citation2021; Garrison & Fitzgerald, Citation2019; Mardis, Citation2016; Mckeever et al., Citation2017; Shannon et al., Citation2019; Wu et al., Citation2022).

In Australia, information literacy is contextualized through the Australian Curriculum in the General Capabilities and the teaching of information literacy is a key role of the TL (ALIA & ASLA, Citation2016). Although there is significant research detailing the leading role TLs take in information literacy instruction (Branch & Oberg, Citation2001; Garrison & Fitzgerald, Citation2022; Gregory, Citation2018; Langford, Citation2002; Laretive, Citation2019), literature explicitly exploring the perceptions of information literacy held by TLs is less common. A small study of five school librarians in Finland revealed a variety of different understandings of information literacy, mostly dominated by an emphasis on information seeking and related critical evaluation of the relevance of the information (Ojaranta, Citation2019). As these school librarians were not also teachers, there was a separation between information seeking and other aspects of information literacy, with one participant observing “What happens after the information seeking is the teachers’ work” (Ojaranta, Citation2019, p. 110). Another small study with three school librarians in the United States focused on the perceptions of the importance of information literacy (Spisak, Citation2021). Although not explicitly investigating definitions of information literacy, this research demonstrated a shared recognition of the changing nature of the information environment and underscored the belief that critical evaluation skills as a part of information literacy were of growing importance.

The understanding of information literacy that an instructor brings to their teaching influences their choice of pedagogical strategies, and evidence in the literature suggests that there are diverse conceptualizations of information literacy (Taylor & Digiacomo, Citation2023). Therefore, the current study will contribute to ongoing advocacy highlighting the vital role of the TL as a collaborative support for teaching and learning, and the enhancement of students’ 21st century capabilities.

Methods

Using a phenomenological design, this research sought to investigate the lived experiences of secondary TLs in Australia and how they engage with students and teachers in the development of information literacy skills and understandings (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018). Phenomenology prioritizes the individual voice of the participants to understand the contexts or situations that have influenced their experiences (Butler-Kisber, Citation2018; Patton, Citation2015). This research used purposive sampling by disseminating a survey through social media, listservs, and newsletters for Australian TL associations and organizations (Given, Citation2008) in November and December 2022, the end of the Australian school year. The survey included seven questions asking for demographic information from the respondents like their title, school level, school classification, role qualifications, and Australian state or territory. The remaining ten questions were open-ended and scaled and related to the respondents’ definition of information literacy and their understanding around the changing nature of information literacy in Australian secondary education and their daily lives. The survey instrument used is included in Appendix A. The quantitative questions were analyzed using descriptive statistics while the qualitative questions were examined using a content analysis method to find emerging common themes from the data (Patton, Citation2015).

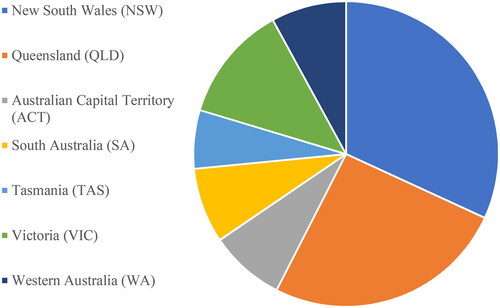

There was a total of 150 respondents to the initial survey. As the inclusion criteria for the study was being a currently practicing, qualified secondary TL, we did not count the survey data from 33 respondents who identified their school as primary and/or their qualifications outside of those accepted for a TL. In Australia, these qualifications include some type of certification, degree, or diploma in both the education and library fields (e.g., Bachelor of Education and Master of Information Science or Master of Education: Teacher Librarianship) (ALIA, Citation2023). The demographic data provided vital insight into the diverse characteristics of TLs and schools. As shown in , the remaining 117 respondents were from a range of Australian states and territories representing all but the Northern Territory and mostly New South Wales (30.8%) and Queensland (24.8%).

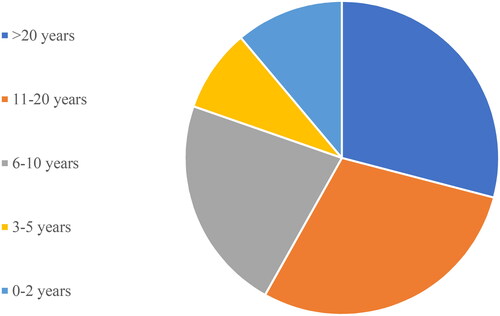

Our respondents also had a range of experience working as a TL as shown in with over half of the sample having taught for 11–20 years (29.1%) or more than 20 years (29.1%).

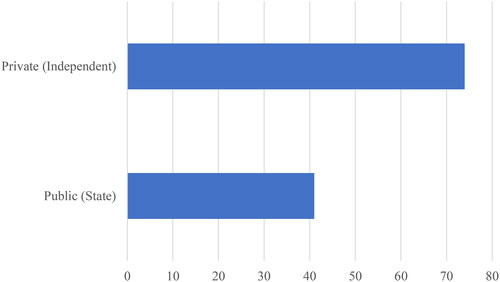

As an inclusion criterion for the study was working in a secondary school, all of our respondents indicated that to some level. While the majority worked at a secondary school with the standard year levels 7–12 in attendance, some operated in the secondary school section of a P/K-12 school to which students of all year levels attend. Smaller numbers worked at schools with further different configurations of students (e.g., Years 7–9 or Years 11–12), reflecting the range of schooling options across Australia. As shown in , most of our respondents were employed in private or independent schools (63.2%) as opposed to public or state schools (35%).

An interesting demographic finding identified by the respondents was the variation of qualifications as evident in . All respondents were qualified teachers; however, while most had completed a Master of Education (Teacher Librarianship) as shown in the top row of the table, others had completed different librarianship qualifications including a Graduate Diploma (Teacher Librarianship) and Bachelor of Education (Teacher Librarianship). This aligns with the ALIA requirement that TLs in Australia must have qualifications that meet eligibility for teacher registration as well as an accredited library and information qualification (ALIA, Citation2023). It also reflects the different courses available in Australia to qualify as a TL that have existed over time and the recent popularity of the Master of Education (Teacher Librarianship), currently the only TL qualification offered to teachers in Australia (ALIA, Citation2023).

Table 1. Librarianship qualifications of respondents.

Alongside the variation of qualifications, there was also a range of titles held by those qualified as TLs. The majority are employed in the role of “Teacher Librarian” (61.5%) with the next highest identifying as “Head of Library” (12%) and “Head of Information Services” (4.3%). Others operate under quite different titles including “Literacy Learning Specialist,” “Teacher in Charge Library Service,” “Consultant-Digital Learning and Library Services,” and “Leader of Research and Resources.” Investigating the differences in these titles and roles is outside of the scope of the present study. Instead of the role titles, we chose to focus on the respondents’ qualifications as noted above in our decision to include their data, and used the definition from ALIA (Citation2023) to determine that. Data from these 117 respondents is discussed in further detail in the following sections.

Results

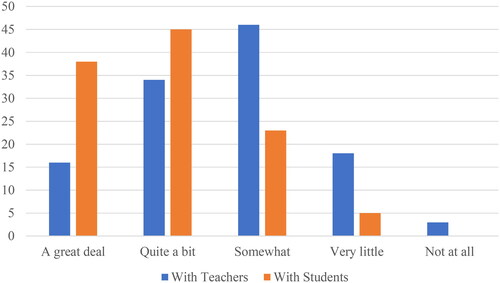

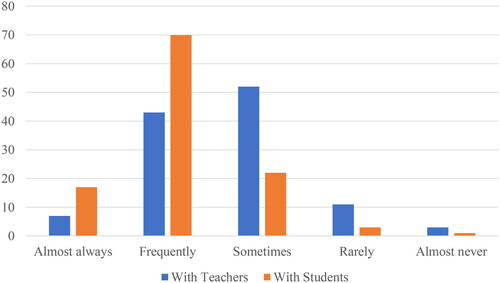

The non-demographic section of the survey included ten questions with eight scaled questions across five levels and two open-ended questions. The scaled questions on the survey asked respondents to consider how the information landscape and their understanding of it have changed during their time as a TL. The first of these questions asked them to describe their role in supporting information literacy with both teachers and students. The results from these two questions are shown comparatively in .

Figure 4. Response to two survey questions—“To what extent does your role as a TL involve supporting the development of information literacy with teachers and with students?

As shown in , respondents felt their role toward supporting information literacy was greater with students than teachers. Almost three-quarters (73.8%) of the total respondents agreed that quite a bit or a great deal of their role involved supporting students in developing information literacy. Similar findings were uncovered in the two questions asking how often they engage in discussions with teachers and with students about information literacy skills and their understanding of these skills. The results from these two questions are shown comparatively in .

Figure 5. Response to two survey questions—“How often do you directly discuss information literacy skills and understandings with teachers and with students?”

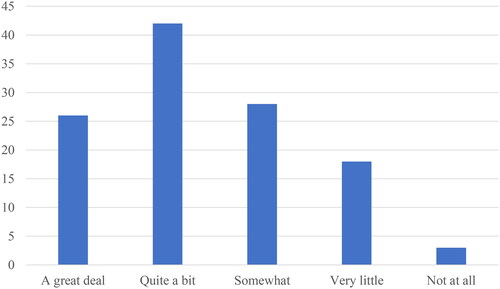

Again, almost three-quarters (73.4%) of the respondents noted that they engage in these discussions frequently or almost always with students. However, they said this happens less often with teachers with just over three-quarters (79.1%) indicating sometimes or frequently as their answer to this question. One question focused on changes in the personal understandings of information literacy and had a range of answers with over half of the total respondents (59.7%) noting that their understandings had changed quite a bit (36.2%) or a great deal (23.5%) during their time as a TL. These findings are shown visually in .

Figure 6. Response to survey question—“To what extent has your understanding of information literacy changed during your time as a TL?”

The varied answers to this question are particularly interesting considering the years of experience the respondents noted in the demographic question shown in with most of our respondents (58.2%) having 11 years or more of experience as a TL.

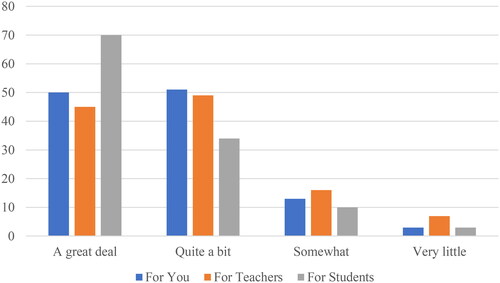

Another question investigating changes in the information landscape asked respondents to consider how changes in areas like media literacy and social media literacy have affected the discovery, use, and sharing of information for the respondents themselves, for the teachers, and for the students. These findings for all three groups are shown in .

Figure 7. Response to three survey questions—“To what extent have changes in the information landscape (e.g., media literacy, social media literacy) affected the discovery, use, and sharing of information for you, for teachers, and for students?”

While respondents identified that these changes have affected information discovery, use, and sharing a great deal for all (including themselves, teachers, and students), this was most frequently noted for students with over 34% of respondents choosing that answer. These findings emphasize the significant changes in the information landscape, particularly with regard to how we navigate and understand sources of information beyond the library, including social media platforms and news media.

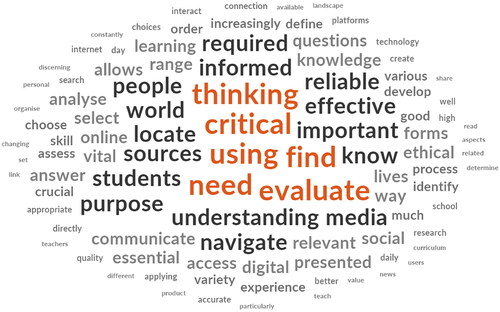

The remaining two questions were open-ended and intended to elicit general definitions about information literacy and its link to everyday life skills. The first broadly asked respondents, “As a TL, how would you define information literacy?” Of the 117 respondents to the survey, 116 included their definitions of information literacy. Their responses are shown in a word cloud in with the most frequent words being larger and in orange and black.

Figure 8. Word cloud response to survey question—“As a TL, how would you define information literacy?”

A content analysis of these responses categorizes them into three themes: (1) nature of information literacy; (2) skills to support and actions involved in information literacy; and (3) value of information literacy.

Responses put into the nature of the information literacy theme reflected a broad, general definition of information literacy. For example, a respondent from VIC with more than 20 years of experience as a TL currently working in a Years 9–12 public school noted it as “the continuous learning of literate practices with an emphasis on a core knowledge of critical and ethical thinking.” Another respondent, a Years 7–12 private school QLD TL with over 20 years of experience, described it as the “ability to navigate the varied and complex systems of information in life in a knowledgeable, productive, and confident manner.” These definitions reflected a more holistic view of information literacy.

Definitions relating to the second theme emphasized specific skills and actions for developing information literacy. As shown in the word cloud in , these responses focused on ideas like finding, selecting, identifying, locating, navigating, analyzing, evaluating, using, communicating, and creating. For example, a TL with 6–10 years of experience working in a P/K-12 private QLD school identified “The knowledge and skills to define, locate, select, organize, present, and assess information” while a NSW Years 7–12 public school TL with 0–2 years of experience noted “The ability to locate, interpret, critically analyze and evaluate information effectively.”

In the third theme, respondents expressed the value of information literacy in rich definitions like “Understanding the world and your capacity to make meaning from it” or “to achieve their personal, social, occupational, and educational goals.” Responses categorized into this theme had a clear focus on information literacy as “lifelong skills” that had deeper meanings for users at personal and societal levels “to make sense of and participate in our world.” For example, a Library Coordinator with over 20 years of experience currently working in a Years 11–12 public school in SA defined information literacy as “essential for democratic and community participation.”

The final survey question was also open-ended and asked respondents, “What do you see as the relationship between developing information skills and making everyday life decisions?” Of the 117 respondents to the survey, 113 answered this question. Their responses are shown in a word cloud in with the most frequent words being larger and in orange and black.

Figure 9. Word cloud response to survey question—“What do you see as the relationship between developing information skills and making everyday life decisions?”

These responses also fell into three themes: (1) ability to locate and evaluate information; (2) applying information literacy skills to make decisions and problem solve; and (3) describing the value of the relationship between information literacy skills and everyday life skills.

Responses categorized under the ability to locate and evaluate information focused on accessing and navigating the changing information landscape, differentiating sources and formats, and assessing credibility as everyday life skills. For example, a TL in an SA Years 7–12 public school with 11–20 years of experience said “Knowing where to find reliable information is important to then be able to make appropriate decisions” while a TL in an ACT Years 7–9 public school with 11–20 years of experience stated how our “information-dense society” makes it challenging to locate authoritative information. However, a proactive Head of Library in a Years 5–12 private NSW school with 11–20 years of experience noted that “If we can teach thinking skills we can access and assess information on any platform.”

Applying information literacy skills to make decisions and problem solve was another emergent theme from this question. Responses in this theme often gave examples of how information literacy skills are necessary to make decisions like “making informed choices about voting,” “how do I pay my road toll?” or “understanding our medications from the doctors,” noting these skills as “integral to almost everything we do.” Again, the issue of credibility and “recognizing bias” came up in these responses about the importance of “highly developed information literacy skills.”

The focus of the last theme included rich descriptions from respondents on the value of the relationship between information literacy skills and everyday life skills, and what could be at stake if youth are not developing high quality skills. Responses stressed this relationship “as a foundation of all decision-making processes.” A NSW TL in a Years 7–12 public school with 6–10 years of experience discussed this specifically in terms of being online when saying, “If people don’t understand how the internet works, with its inherent dangers, they will be at a lifelong disadvantage.” According to a QLD TL at an independent Years 5–12 school with 6–10 years of experience, strong development of these skills “ensures we build resilient and responsible young leaders together with ethical foresight and consideration of others,” emphasizing again the value of the relationship between information literacy and everyday life skills.

Discussion

Three salient themes emerged from the survey findings, initiating the discussion in this section. The first theme relates to the contemporary practices of Australian secondary TLs supporting teachers’ and students’ information literacy. The second theme pertains to the implications of shifts in the information ecosystem for TL practices, highlighting the indispensable role of qualified TLs in supporting teachers and students amid these changes. The third theme sheds light on the ongoing imperative for professional learning among both new and experienced TLs. This learning aims to align the skills-based approach to information literacy, traditionally the central focus, with the social and contextualized understandings necessary for equipping students with skills relevant to both school-based and everyday life decisions and research. The following sections discuss each theme in detail.

Contemporary information literacy practices

While the survey did not ask TLs to delve deeply into sharing the strategies that they use to support students and teachers in developing their information literacy, the data tells a story of school library professionals who are very aware of the skills and abilities that individuals who are information literate possess. TLs work frequently with students to support the development of these capabilities and demonstrate an increasing shift away from a focus on “research skills” to embrace a broader notion of critical and creative thinking that equips students to effectively engage with information both for academic and personal or social goals; as succinctly described by a public school TL in the ACT with more than 20 years of experience: “Knowing how to find, interpret and apply information found is key to a fuller, more productive life.”

Contemporary information literacy practices as understood by Australian secondary TLs involve actively interrogating and engaging with information—as evidenced by the frequency of verbs used in their definitions of the concept. Interestingly, while the words “sources” and “digital” reveal an acknowledgment of the various channels through which information is accessible to students, the common use of terms “locate” and “find” suggest that information literacy practices have not yet shifted from a static view of information that awaits discovery. While information stored in academic databases may still require a search strategy, much of the information with which students will engage will be pushed to them, through platforms driven by algorithms that have determined personalized and customized curations (Head et al., Citation2020, p. 16). In contrast, there is a clear awareness that information students engage with may lack credibility and quality, hence the emphasis on terms, such as “evaluate,” “critically,” “understanding,” and “effectively.” This may be a function of the proliferation of studies about the impact and influence of mis- and dis-information, alongside a surge in the general public’s attention to these concepts, frequently referred to as “fake news,” notable since 2016 (Pangrazio, Citation2018).

The notion that information literacy practices extend beyond the school context was also highly evident in the frequency with which respondents spoke about lifelong learning and engagement in society. Adjectives including “critical,” “required,” and “important” were frequently used by respondents to describe the relationship between information skills and everyday life decisions, while others used words, such as “crucial” and “essential” to describe this relationship. This choice of language represents alignment with findings in the survey that suggest that practicing Australian secondary TLs are generally very cognizant of change within the information ecosystem within which school education exists and this understanding is discussed in the following section.

Implications of the shifting information ecosystem

The survey responses shown in demonstrate that the TLs are mindful of significant alterations within the information landscape, prompting an acknowledgment that their perception of information literacy has shifted accordingly. The frequency of direct discussions regarding information literacy skills and understandings with students, along with the heightened awareness of the necessity for information skills when making everyday decisions indicates that TLs consider information literacy not only as an academic skill but also as a crucial life skill. This is evident in responses, such as this detailed comment from a QLD TL in a Years 5–12 independent school with 6–10 years of experience:

Developing information literacy skills in a school community is more important than ever with compounding multi-model platforms changing the online landscape daily. It ensures we build resilient and responsible young leaders together with ethical foresight and consideration of others. It encompasses four main skills for the future; accessing and analyzing information with critical thinking; adaptability and using initiative to choose multi-modal deliveries for effective presentation to boost curiosity in another. Everyday decisions will be easier to navigate, and a more balanced approach to decision making will be enhanced with well-developed information literacy skilling.

sometimes there is a disconnect between everyday decisions and information literacy skills. I think the students see it as something isolated to library and that the teachers see it as something that they only need in Senior School. We have had to work very hard to get the teachers to realize that it needs to be tackled from kindergarten but in an age-appropriate way. I would say there is a strong connection in that we constantly (should) be questioning the information presented to us.

Cultivating alignment between theory and practice through professional learning

The final emergent theme related to the need for professional learning for both new and experienced TLs to support their position as collaborators with teachers in the development of learning and teaching experiences which reflect the ongoing changes in the information landscape. As evidenced through the observations of the TLs regarding the correlation between information literacy and everyday decisions in , there is a need to move away from a siloed approach to teaching for school-based, subject-specific activities to more real world, everyday life application to using information literacy skills. This need is also exemplified by the divergent definitions of information literacy shared by respondents in the first open-ended question of the survey shown visually in .

Reinforcing the need for TLs to work collaboratively with teachers is the fact that the latest version (9) of the national curriculum in Australia, which all schools in the country are meant to follow, has no explicit reference to information literacy (ACARA, Citation2022a). While information literacy skills are implicitly embedded as digital literacy (called Information and Communication Technologies in previous versions of the curriculum) in the seven General Capabilities, intended to “equip young Australians with the knowledge, skills, behaviors, and dispositions to live and work successfully” (ACARA, Citation2022b, para. 1), their absence in standards with specific outcomes does not align with their importance in everyday life and contemporary society. Our research findings clearly indicate that TLs understand the necessity of integrating information literacy across all learning and teaching programs. However, to effectively convey this knowledge to teachers and to emphasize its fundamental role throughout the entire curriculum, TLs require additional support. Ongoing professional learning will enable TLs to more effectively enhance teachers’ understanding of information literacy and enable them to impart these crucial skills to students through well-structured learning and teaching initiatives.

TLs in the NSW Department of Education (DET) have been working since 2018 (Wall, Citation2018, Citation2019, Citation2021) to develop a more robust vision of information literacy through the Information Fluency Framework (IFF). The IFF was specifically designed to help TLs, students, and teachers “to understand the relationship between information fluency (expertise of the teacher librarian) and learning area content (expertise of the teacher)” (NSW DET, Citation2021, p. 6). As shown in , the IFF is underpinned by five elements (i.e., competencies associated with information fluency) which are connected by the seven General Competencies of the national curriculum (ACARA, Citation2022b) and the NSW state syllabi as well. The embedding of digital literacy skills (labeled as ICT in the original IFF) throughout the IFF makes it a key document for supporting TLs to incorporate these skills into collaborative planning with teachers in NSW and beyond.

Figure 10. Information fluency framework (NSW DET, Citation2021). © State of New South Wales (Department of Education), 2023. Reproduced licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

As most of the TL respondents in our study note, they directly discuss and support information literacy skills “frequently” with students and “somewhat” with teachers, the IFF is an option for expanding these discussions and engaging a more advanced perspective on how changes in the information landscape have affected teaching and learning. The IFF is publicly accessible but is not a recognized curriculum document in any Australian state aside from NSW. Based upon the findings of this research, it is suggested that this framework (or one similar) be introduced Australia-wide, accompanied by relevant professional learning for TLs, to create greater opportunities for information literacy to be embedded within learning and teaching. It would generate greater recognition for TLs and substantiate their leading role in embedding much needed information literacy skills throughout the curriculum.

Providing TLs with strategies to enable them to work collaboratively with teachers and strengthen their knowledge of the evolving concept of information literacy must also be a part of university education in teacher librarianship. As dual qualified practitioners, “TLs can work with teachers to design learning that integrates learning area content, information literacy, and general capabilities” (NSW DET, Citation2021, p. 5), and therefore teachers studying to become TLs must have opportunities to build a firm theoretical understanding of information literacy so that they can effectively advocate for their place in collaborative curriculum planning and teaching.

Limitations

Inherent limitations of this study related to the data collection methods and sample. Firstly, our recruitment strategy enlisted the support of professional organizations related to school libraries and libraries in general as well as listservs and social media promotion to disseminate our survey. This approach may have gathered participants most interested in professional development and curious about information literacy issues so may not be completely representative of the population of Australian secondary TLs sought for participation. Further, while we had a breadth of responses across the country with a focus on the most populated states in the east (NSW, QLD, VIC), there were no responses from the Northern Territory. Secondly, this was a survey of secondary TLs in Australia working in a specific context. While there are plans for a further stage surveying primary school TLs in Australia, generalizations across that population are not advised. Another issue was the identification of participants’ titles, qualifications, and different contexts in their schools. While we specifically sought a sample of qualified secondary TLs working in a school library, not all had that exact title or clear qualifications. These differences in role titles across states and schools may be a future direction for research, especially as it was an issue identified by the Australian Senate Inquiry into School Libraries and resulting report School libraries and teacher librarians in 21st century Australia (House of Representatives Standing Committee on Education & Employment, Citation2011). Despite these limitations, this research helps to serve as a foundation for further work looking at the changing nature of information literacy and everyday life skills. To address and clarify some of the limitations associated with the survey responses and participant demographics, the second phase of the research includes interviews with a range of the responding TLs from various states and territories, school levels, and years of experience. This step will also serve to further illuminate the emergent themes from the survey and go deeper into the findings described here.

Conclusions

Understanding the perspective of Australian secondary TLs on working with teachers and students to support the development of everyday life information literacy skills was an important component of this study. Our findings from the survey suggest that respondents use a diverse range of definitions and contemporary practices around information literacy in collaboration with teachers and students. As more experienced respondents noted, there have been significant changes in the information landscape, influencing TL practice over the years and these shifts highlight the indispensable role of qualified TLs in supporting teachers and students. They also suggest the importance of continuing professional learning for new and experienced TLs aligning the traditional skills-based approach to information literacy (as described in their definitions of information literacy and shown in ) to a more contextualized approach linking skills relevant to both school-based and everyday life decisions. “Being a global citizen,” as highlighted by one of our respondents and noted in our title, maybe the driving aim and crucial link in the relationship between these two approaches.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Al-Qallaf, C. L., & Aljiran, M. A. (2022). The teaching and learning of information literacy skills among high school students: Are we there yet? International Information & Library Review, 54(3), 225–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572317.2021.1973354

- Amram, S. B., Aharony, N., & Bar Ilan, J. (2021). Information literacy education in primary schools: A case study. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 53(2), 349–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000620938132

- Anderson-Story, J., Dow, M., Kane, C., & Ternes, C. (2014). Bridges to the future: Teaching information literacy across standards, institutions, and the workforce. Kansas Library Association College and University Libraries Section Proceedings, 4(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.4148/2160-942X.1035

- Australian Curriculum, Assessment, and Reporting Authority (2022a). Australian curriculum. https://acara.edu.au/curriculum

- Australian Curriculum, Assessment, and Reporting Authority (2022b). General capabilities. https://v9.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/f-10-curriculum-overview/general-capabilities

- Australian Government Department of Education (2022, August 22). Links to 21st century learning. Australian Government. https://www.education.gov.au/australian-curriculum/national-stem-education-resources-toolkit/i-want-know-about-stem-education/what-works-best-when-teaching-stem/links-21st-century-learning

- Australian Library and Information Association (2023). Becoming a library and information professional. Australian Library and Information Association. https://alia.org.au/Web/Web/Careers/Becoming-An-Information-Professional/Becoming-a-Library-and-Information-Professional.aspx

- Australian Library and Information Association, & Australian School Library Association. (2016). Statement on Teacher Librarians in Australia. Australian Library and Information Association. https://read.alia.org.au/alia-asla-statement-teacher-librarians-australia

- Becker, B. (2022). Teaching users – Information and technology literacy instruction. In S. Hirsh (Ed.), Information services today: An introduction (pp. 216–228). Rowman & Littlefield.

- Branch, J. L., & Oberg, D. (2001). The teacher-librarian in the 21st century: The teacher-librarian as instructional leader. School Libraries in Canada, 21(2), 9–11.

- Bruce, C. (1997). The seven faces of information literacy. Auslib Press.

- Bundy, A. L. (2004). Australian and New Zealand information literacy framework: Principles, standards and practice. Australian and New Zealand Institute for Information Literacy.

- Butler-Kisber, L. (2018). Qualitative inquiry: Thematic, narrative and arts-based perspectives (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526417978

- Chalkiadaki, A. (2018). A systematic literature review of 21st century skills and competencies in primary education. International Journal of Instruction, 11(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.12973/iji.2018.1131a

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches (5th ed.). SAGE.

- Dolničar, D., Boh Podgornik, B., Bartol, T., & Šorgo, A. (2020). Added value of secondary school education toward development of information literacy of adolescents. Library & Information Science Research, 42(2), 101016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2020.101016

- Fantin, M. (2010). Perspectives on media literacy, digital literacy and information literacy. International Journal of Digital Literacy and Digital Competence, 1(4), 10–15. https://doi.org/10.4018/jdldc.2010100102

- Farmer, L. (2019). News literacy and fake news curriculum: School librarian perceptions of pedagogical practices. Open Information Science, 3(1), 222–234. https://doi.org/10.1515/opis-2019-0016

- Garrison, K. L., & Fitzgerald, L. (2019). “One interested teacher at a time”: Australian teacher librarian perspectives on collaboration and inquiry. 48th Annual Conference of the International Association of School Librarianship, Dubrovnik, Croatia.

- Garrison, K. L., & Fitzgerald, L. (2022). “On the fly”: Collaboration between teachers and teacher librarians in inquiry learning. In 7th European Conference on Information Literacy (pp. 411–426). Springer.

- Geisinger, K. F. (2016). 21st Century skills: What are they and how do we assess them? Applied Measurement in Education, 29(4), 245–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/08957347.2016.1209207

- Given, L. (2008). The SAGE Encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412963909

- Global Partnership for Education (2020). 21st Century skills: What potential role for the global partnership for education? A landscape review. https://www.globalpartnership.org/sites/default/files/document/file/2020-01-GPE-21-century-skills-report.pdf

- Gregory, J. (2018). The information literate student: Embedding information literacy across disciplines with guided inquiry. Teacher Librarian, 45(5), 27–34.

- Head, A. J., Fister, B., & MacMillan, M. (2020). Information literacy in the age of algorithms. Project Information Research Institute. https://projectinfolit.org/publications/algorithm-study/

- Hepworth, M., Almehmadi, F., & Maynard, S. (2014). A reflection on the relationship between the study of people’s information behaviour and information literacy: Changes in epistemology and focus. In C. Bruce, H. Partridge, K. Davis, H. Hughes, I. Stoodley, & A. Spink (Eds.), Information experience: Approaches to theory and practice. Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Hicks, A., & Lloyd, A. (2021). Deconstructing information literacy discourse: Peeling back the layers in higher education. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 53(4), 559–571. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000620966027

- Hicks, A., Mckinney, P., Inskip, C., Walton, G., & Lloyd, A. (2023). Leveraging information literacy: Mapping the conceptual influence and appropriation of information literacy in other disciplinary landscapes. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 55(3), 548–566. https://doi.org/10.1177/09610006221090677

- Hider, P., White, H., & Jamali, H. R. (2019). Minding the gap: Investigating the alignment of information organisation research and practice. Information Research, 24(3).

- House of Representatives Standing Committee on Education and Employment (2011). School libraries and teacher librarians in 21st century Australia. Commonwealth of Australia. https://www.aph.gov.au/parliamentary_business/committees/house_of_representatives_committees?url=ee/schoollibraries/report.htm

- International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (2021). IFLA School Library Manifesto. IFLA. https://cdn.ifla.org/wp-content/uploads/files/assets/school-libraries-resource-centers/publications/ifla_school_manifesto_2021.pdf

- Johnston, N. (2020). Living in the world of fake news: High school students’ evaluation of information from social media sites. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 69(4), 430–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750158.2020.1821146

- Jones-Jang, S. M., Mortensen, T., & Liu, J. (2021). Does media literacy help Identification of fake news? Information literacy helps, but other literacies don’t. American Behavioral Scientist, 65(2), 371–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764219869406

- Julien, H., & Williamson, K. (2011). Discourse and practice in information literacy and information seeking: Gaps and opportunities. Information Research, 16(1).

- Kankam, P. K. (2023). Information literacy development and competencies of high school students in Accra. Information Discovery and Delivery, 51(4), 393–403. https://doi.org/10.1108/IDD-10-2021-0114

- Koltay, T. (2011). The media and the literacies: Media literacy, information literacy, digital literacy. Media, Culture & Society, 33(2), 211–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443710393382

- Lamb, A. (2017). Fact or fake? Curriculum challenges for school librarians. Teacher Librarian, 45(1), 56–63.

- Langford, L. (2002). Information literacy: Whose view, whose responsibility, and does it really matter? Access, 16(3), 21–24.

- Lanning, S., & Gerrity, C. (2022). Concise guide to information literacy (3rd ed.). ABC-CLIO, LLC.

- Laretive, J. (2019). Information literacy, young learners and the role of the teacher librarian. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 68(3), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750158.2019.1649795

- Lloyd, A. (2010). Information literacy landscapes: Information literacy in education, workplace and everyday contexts (1st ed.). Chandos Publishing.

- Lloyd, A. (2017). Information literacy and literacies of information: A mid-range theory and model. Journal of Information Literacy, 11(1), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.11645/11.1.2185

- Lupton, M., & Bruce, C. (2010). Windows on information literacy worlds: Generic, situated and transformative perspectives. In A. Lloyd & S. Talja (Eds.), Practising information literacy: Bringing theories of learning, practice and information literacy together. Elsevier Science & Technology.

- Majid, S., Foo, S., & Chang, Y. K. (2020). Appraising information literacy skills of students in Singapore. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 72(3), 379–394. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-01-2020-0006

- Mammadova, T. (2022). Academic writing and information literacy instruction in digital environments: A complementary approach. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-19160-2_5

- Mardis, M. A. (2016). Librarians and educators collaborating for success: The international perspective. ABC-CLIO, LLC.

- Martin, C. M., Garcia, E. P., & Mcphee, M. (2017). Information literacy outreach: Building a high school program at California State University Northridge. Education Libraries, 35(1–2), 34–47. https://doi.org/10.26443/el.v35i1-2.314

- Mckeever, C., Bates, J., & Reilly, J. (2017). School library staff perspectives on teacher information literacy and collaboration. Journal of Information Literacy, 11(2), 51–68. https://doi.org/10.11645/11.2.2187

- Moto, S., Ratanaolarn, T., Tuntiwongwanich, S., & Pimdee, P. (2018). A Thai junior high school students’ 21st century information literacy, media literacy, and ICT literacy skills factor analysis. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 13(09), 87. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v13i09.8355

- New South Wales Department of Education (2021). Information fluency framework V1.1. https://education.nsw.gov.au/content/dam/main-education/teaching-and-learning/curriculum/media/documents/Information_fluency_framework.pdf

- Notley, T., & Dezuanni, M. (2018). Advancing children’s news media literacy: Learning from the practices and experiences of young Australians. Media, Culture & Society, 41(5), 689–707. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443718813470

- Ojaranta, A. (2019). Information literacy conceptions in comprehensive school in Finland: Curriculum, teacher and school librarian discourses [Doctoral dissertation]. Åbo Akademi University. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-765-941-3

- Pangrazio, L. (2018). What’s new about ‘fake news’? Critical digital literacies in an era of fake news, post-truth and clickbait. Páginas de Educación, 11(1), 6–22. https://doi.org/10.22235/pe.v11i1.1551

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice (4th ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Polizzi, G. (2020). Information literacy in the digital age: Why critical digital literacy matters for democracy. In A. Whitworth (Ed.), Informed societies (pp. 1–25). American Library Association.

- Rath, L. (2022). Factors that influence librarian definitions of information literacy. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 48(6), 102597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2022.102597

- Saunders, L., Severyn, J., & Caron, J. (2017). Don’t they teach that in high school? Examining the high school to college information literacy gap. Library & Information Science Research, 39(4), 276–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2017.11.006

- Schachter, D. (2020). Theory into practice: Challenges and implications for information literacy teaching. IFLA Journal, 46(2), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0340035219886600

- Secker, J. (2018, June 21). A new definition of information literacy [PowerPoint Slides]. CILIP. https://www.cilip.org.uk/news/421972/What-is-information-literacy.htm

- Shannon, C., Reilly, J., & Bates, J. (2019). Teachers and information literacy: Understandings and perceptions of the concept. Journal of Information Literacy, 13(2), 41–72. https://doi.org/10.11645/13.2.2642

- Shuhidan, S. M., Majid, M. A., Shuhidan, S. M., Anwar, N., & Hakim, A. A. A. (2021). School resource center and students’ civilisation in a digital age. Asian Journal of University Education, 16(4), 190–199. https://doi.org/10.24191/ajue.v16i4.11953

- Smith, J. K., Given, L. M., Julien, H., Ouellette, D., & Delong, K. (2013). Information literacy proficiency: Assessing the gap in high school students’ readiness for undergraduate academic work. Library & Information Science Research, 35(2), 88–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2012.12.001

- Spisak, J. R. (2021). School librarian perceptions of the importance of information literacy. School Libraries Worldwide, 26(1), 151–164. https://doi.org/10.29173/slw8253

- Taala, W., Franco, F. B. Jr., & Teresa, P. H. S. (2019). Library literacy program: Library as battleground for fighting fake news. OALib, 6(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.4236/oalib.1105296

- Taylor, C., & Digiacomo, D. K. (2023). Approaches to information literacy conceptualisation in primary, secondary, and higher education contexts: A review of current scholarly literature. Journal of Information Literacy, 17(1), 89–104. https://doi.org/10.11645/17.1.3258

- Tewell, E. (2015). A decade of critical information literacy: A review of the literature. Comminfolit, 9(1), 24–43. https://doi.org/10.15760/comminfolit.2015.9.1.174

- Wall, J. (2018). Information + competency + literacy = fluency: A thought piece. Scan, 37(6). https://education.nsw.gov.au/content/dam/main-education/teaching-and-learning/professional-learning/scan/media/documents/vol-37/Scan_2018_37-6.pdf

- Wall, J. (2019). Information fluency – A path to explore and innovate? Scan, 38(9), 7–11. https://education.nsw.gov.au/content/dam/main-education/teaching-and-learning/professional-learning/scan/media/documents/vol-38/Scan_2019_38-9.pdf

- Wall, J. (2021). Information fluency: A NSW journey. Scan, 40(5), 4–9. https://education.nsw.gov.au/content/dam/main-education/teaching-and-learning/professional-learning/scan/media/documents/vol-40/Scan_40-9_Oct2021_AEM.pdf

- Wu, D., Zhou, C., Li, Y., & Chen, M. (2022). Factors associated with teachers’ competence to develop students’ information literacy: A multilevel approach. Computers & Education, 176, 104360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104360

- Zhu, S., Harrison Hao, Y., Macleod, J., Yu, L., & Wu, D. (2019). Investigating teenage students’ information literacy in China: A social cognitive theory perspective. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 28(3), 251–263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-019-00433-9

Appendix A:

Survey questions

This aspect of the study involves a 15 min online survey including some demographic questions around your school, area, and position as well as questions targeting your perceptions and ideas of the information literacy needs of teachers and students and the changing landscape of these needs.

Participation in this research is entirely your choice. Only those people who give their informed consent by posting in the online discussion forum will be included in the project. Whether or not you decide to participate is your decision.

The online survey is anonymous up until the last question asking for volunteers to interview for the second phase of the research. If you volunteer for the interview portion of this study by including your name and email address, the rest of your data will be identifiable and the researchers will use it to ensure a diverse range of the ∼10 participants selected for phase two. If you do not include your name here, your data will be completely anonymous.

Demographic questions

Are you currently working in a school in Australia?

What is your job title?

What are your qualifications (e.g. as a teacher librarian)?

How long have you been working as a teacher librarian?

What are the year levels at your school?

How is your school classified?

Which Australian state or territory is your school located?

Information literacy questions

How would you as a TL define information literacy?

_______________________________________________________

To what extent has your understanding of information literacy changed during your time as a TL?

Not at all

Very little

Somewhat

Quite a bit

A great deal

To what extent does your role as a TL involve supporting the development of information literacy with teachers?

Not at all

Very little

Somewhat

Quite a bit

A great deal

To what extent does your role as a TL involve supporting the development of information literacy with students?

Not at all

Very little

Somewhat

Quite a bit

A great deal

To what extent have changes in the information landscape (e.g., media literacy, social media literacy) affected how you discover, use, and share information?

Not at all

Very little

Somewhat

Quite a bit

A great deal

To what extent have changes in the information landscape (e.g., media literacy, social media literacy) affected how high school teachers discover, use, and share information?

Not at all

Very little

Somewhat

Quite a bit

A great deal

To what extent have changes in the information landscape (e.g., media literacy, social media literacy) affected how high school students discover, use, and share information?

Not at all

Very little

Somewhat

Quite a bit

A great deal

How often do you directly discuss information literacy skills and understandings with your teachers?

Almost never

Rarely

Sometimes

Frequently

Almost always

How often do you directly discuss information literacy skills and understandings with your students?

Almost never

Rarely

Sometimes

Frequently

Almost always

What do you see as the relationship between developing information literacy skills and making everyday decisions?

_______________________________________________________

If you would be interested in participating in a second phase of this research involving interviews, please include your name and email address and we will contact you shortly with full information regarding this phase.

Name:_______________________________________________________Email:_______________________________________________________