ABSTRACT

Although there is a substantial difference in turnout between local and national elections, a significant number of citizens are locally mobilised yet they do not vote in national elections. While some previous studies have predominantly attributed this pattern to a municipal size, this study ascertains that locally bound motives and attitudinal factors also exert influence, independent of the municipality size. The research reveals that citizens who report personal acquaintance with local councillors also express an overall satisfaction with the local election outcomes and perceive a notable change in council politics are more inclined to vote only in local elections. Although displaying lower support of central government, these locally mobilised citizens exhibit greater satisfaction with the state of democracy and local political dynamics in comparison to non-voters. Consequently, these significant findings offer an optimistic outlook from a democratic theory perspective.

Introduction

Local elections are seen as fairly insignificant and have low turnout levels, similar to those for regional assemblies and the European Parliament. This is worrisome because a high turnout in any elections is perceived as the necessary precondition for a healthy democracy (Dahl Citation1989). It is believed that with a higher turnout, there is a higher equality in representation, which is at the core of the democratic ideal (Wolfinger and Rosenstone Citation1980). Although most studies show that in majority of countries the turnout in local elections is substantially lower than in national elections (Bhatti et al. Citation2019; Gendźwiłł Citation2021; Gendźwiłł and Kjaer Citation2021; Górecki and Gendźwiłł Citation2021; Morlan Citation1984; Rallings and Thrasher Citation2007; Sciarini et al. Citation2015), electoral data indicates that a significant group of citizens tends to vote only in these ‘second-order‘ (SOE) municipal elections (Schakel and Jeffery Citation2013), whilst abstaining from voting in, arguably, more important national elections.

Studies on the national-local turnout gap (Gendzwill Citation2021; Gendźwiłł and Kjaer Citation2021; Morlan Citation1984) show that the aggregate turnout in local elections is almost always lower than the turnout in the preceding parliamentary elections. However, we see variance across municipalities with different population sizes. The larger the municipality, the fewer eligible voters turn out at local elections compared to national elections, and vice versa. As argued in their seminal research by Dahl and Tufte (Citation1973), the local-level participation is more effective in smaller units such as rural municipalities. As a result, electoral turnout (Ryšavý and Bernard Citation2013; Swianiewicz Citation2002) and trust (Denters Citation2002, 793) in local government elections rise as the size of the municipality decreases. The citizens residing in smaller municipalities seem to exhibit a genuine concern for local democracy; however, what factors contribute to their lack of participation in national politics? Is municipal size solely responsible for the disparity in voter turnout, or do individual-level traits, such as political attitudes and beliefs, also influence their choices? Moreover, could these individual characteristics shed light on the paradox between the mobilisation observed at the local level, and the lack of engagement at the national level? The current research provides only a limited set of explanations.

A prominent SOE theory (Reif and Schmitt Citation1980) does not seem to explain why a specific group of people vote only in local elections because the theory states that the voters are more concerned with national issues and that less is at stake in local elections. Although the existing research concerning the factors related to the turnout in local elections (Górecki and Gendźwiłł Citation2021; Kouba, Novák, and Strnad Citation2021) indicates that the predictors are largely the same as in parliamentary elections, we know relatively little about the kind of voters who turn out only in local elections and not in the national ones as we have only a limited number of studies focusing explicitly on this voters’ group. For example, Rallings and Thrasher (Citation2007) focus mostly on those who vote in both national and local elections, as opposed to those who vote only in national elections and, as such, they neglect the group of citizens voting only in local elections. Bhatti et al. (Citation2019) analysed the core and ‘peripheral voters across local, European and national elections in Denmark, using a large pool of official electoral and census statistics and focusing on the sociodemographic factors affecting the decision to participate in elections at a different level and across time. Similarly, some studies from Switzerland (Sciarini et al. Citation2015) and Sweden (Dehdari, Meriläinen, and Oskarsson Citation2021) show that the ‘selective voters have a similar profile as abstainers. None of the papers mentioned above provided any other explanation beyond the basic sociodemographics.

The studies on voter turnout highlight that voters who vote only in local elections have their own intrinsic and specific place-bound reasons for voting, such as the personal knowledge of local councillors (Pietryka and DeBats Citation2017), trust, and support of continuity in local politics (Dodeigne et al. Citation2022). However, what makes a group of voters who vote only in local elections distinct from the citizens who vote only in the national ones? Perhaps they feel distant from the national politics and see it less important to them than the local politics, or they may even feel distrustful and alienated from the national level. Additionally, given the lack of participation at the national level, what makes this group distinct from the non-voters who also refrain from participating at the national level?

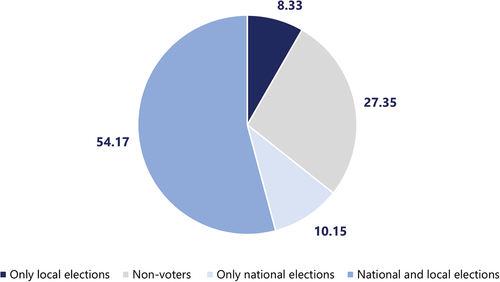

Utilising the distinctive post-election survey data collected immediately after the 2018 Czech municipal elections, this paper aims to examine whether the underlying reasons for individuals voting in local elections but abstaining from the first-order (national) elections can be attributed to locally-oriented motivations and psychological characteristics, while taking into account the influence of municipal size as a contextual factor. We focus predominantly on a significant group of citizens (approximately 8% of all eligible voters (see ) who vote in local elections but refrain from electoral participation at the national level. The data revealed that this group of citizens is driven by local motives. Besides the fact that they are citizens of smaller municipalities, their familiarity with specific candidates, desire for a change in council politics and satisfaction with the results of local elections hold when controlling for the municipal size. Moreover, the analysis indicates that their limited trust in national institutions might explain their lack of participation in parliamentary elections. However, this group appears to exhibit higher satisfaction with democracy at the systemic level compared to non-voters. Although these results may seem perplexing, they importantly align with the assumptions that engaging in local-level participation can potentially mitigate citizens’ political discontent with the democratic systems.

Figure 1. Self-reported turnout in 2018 post-election study.

The paper proceeds as follows. Initially, we discuss the motives for electoral participation and propose a theoretical framework in which we argue that the SOE theory is not well-suited as an explanation for the motives of local-only election voters but that local motives play a role. This part is followed by a brief introduction of the research design and the Czech context. Subsequently, we proceed with the operationalisation of the concepts, data and methods. The analytical section predicts different categories of voters using a multinomial regression model. The discussion then focuses on an analysis of attitudinal political concepts and the implications for the current state of democracy. The concluding section discusses the results thereof.

Factors of local level mobilisation and national level demobilisation: why do people vote only in local elections?

In every election, we can conceptualise the electorate as consisting of a diverse range of groups. There is a group of core voters who regularly and consistently across time vote in all types of elections; a group of core abstainers who do not participate in any elections whatsoever; and a group of selective voters who choose to occasionally participate in the elections held in the country at various levels and across time (Dehdari, Meriläinen, and Oskarsson Citation2021). A selective voter may prefer to vote only in local elections or other SOE (regional, European, etc.), and, in the next national elections, a voter may decide not to participate but in time he/she may change the decision. The selective voters thus decide ad hoc before each elections whether or not they will participate. Additionally, there may be a group of core local voters voting only in local elections, and a group of core national voters voting only in national elections. The category can be analogous to any type of election (e.g., the regional and European Parliament ones). The categories are presented in which, for the sake of simplicity, shows local and national elections only.

Table 1. Examples of voters` group and conceptualisation.

Because this study employs a single individual-level post-election survey with a self-reported turnout, we are methodologically unable to differentiate between the ideal categories and, instead, we must utilise the four categories presented in above. Consequently, the group of voters who self-reported their turnout only in local elections may practically consist of two subgroups: the selective voters who specifically participate in local elections without previous participation in the parliamentary ones (yet they may have participated in national elections in previous electoral cycles), and the core voters engaged exclusively in local elections. Considering the stability of turnout patterns in local and national elections over time (see Maškarinec Citation2022), it is reasonable to assume that roughly majority of individuals who self-reported their turnout only in local elections belongs to the group of core local voters and minority to the group of selective ones. Needless to say, we are not able to derive the exact proportion as both groups’ electoral participation may be driven by different motivations.

The vast amount of academic literature and research on individual participation data focuses on predictors simply explaining the turnout as opposed to abstention (Cancela and Geys Citation2016; Górecki and Gendźwiłł Citation2021; Smets and van Ham Citation2013) and they do not differentiate between different voters’ groups, and if so, they analyse them just in terms of the voters` sociodemographics (Bhatti et al. Citation2019; Dehdari, Meriläinen, and Oskarsson Citation2021; Sciarini et al. Citation2015). Generally, the predominant individual predictor of turnout at both the local and the national levels is the socioeconomic status of a voter (SES) (i.e., income level, occupational status and education) (Rosenstone and Hansen Citation1993; Verba and Nie Citation1972; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Citation1995). This ‘resource model‘ (Smets and van Ham Citation2013) clearly states that the more resources a citizen possesses, the more likely he or she is to participate in the electoral process. The citizens with higher education and income have the competencies, skills, and time to participate in various types of elections, as opposed to low SES citizens. We may thus generally suppose that the politically engaged citizens voting in all types of elections will have the highest SES as opposed to the selective voters or voters voting only in other but the national elections.

Complementary to this model are psychological factors that can intervene with the SES or have an independent effect on participation, such as, for example, political interest, political knowledge, satisfaction with democracy, political alienation, or political cynicism (see a review article by Smets and van Ham Citation2013). Those classical determinants of individual-level turnout thus poorly explain why voters choose different arenas to participate because they presume roughly a similar effect across the different election types. Indeed, a recent study by Górecki and Gendźwiłł (Citation2021, 42) on a large dataset of individual-level predictors across the European countries shows that the individual determinants for the turnout are similar for the national and local elections and have nearly the same effect size. However, how can we theoretically explain the different turnout levels on both the aggregated and individual-level studies? Why do people choose to vote only in some types of elections?

At the first glance, the SOE theory might offer a plausible explanation. The SOE theory simply states that the voter turnout is lower in less significant elections because less is at stake (Reif and Schmitt Citation1980). This seems to be a promising explanation of the turnout gap across elections, namely the lower overall turnout rate in local elections compared to national elections. The SOE thus offers a good explanation for the group of people who vote only in national and more important elections (Rallings and Thrasher Citation2005, Citation2007). Nevertheless, one group of voters (the core local voters) regularly turns out in local elections but does not vote in national elections thus contradicting the SOE theory. Above all, within a group of selective voters, there may be individuals who gradually develop a preference for local elections over the national ones, despite occasionally participating in the national elections, too. This is puzzling and contradicts the SOE theory. These voters prefer to vote in less important elections rather than in those which are supposedly more important. This raises the questions: who are these voters? What are their motives for voting in local elections? What individual characteristics can predict their choice?

As the focus of this study is on voters who declared that they voted only in local elections, we need to deal with the specific details related to the local level of governance and, most importantly, to test plausible hypotheses that would explain the variations in people’s choices to selectively turn out for different kinds of elections. First and foremost, the effects of the individual-level factors may be moderated by the context of the elections, as local elections are distinct from the national elections in many aspects (see Baekgaard et al. Citation2014; Kjaer and Steyvers Citation2019; Lefevere and Van Aelst Citation2014; Rallings, Temple, and Thrasher Citation1996). We can particularly see a large degree of variation in the kind of elections within a country across municipalities. As argued by Kjaer and Steyvers (Citation2019), the classical SOE model does not take this variation into account. The current research concludes that the primary factor explaining the differences in the aggregated level turnout is the population size of a municipality (Cancela and Geys Citation2016; Górecki and Gendźwiłł Citation2021; Kouba, Novák, and Strnad Citation2021; Oliver Citation2000; van Houwelingen Citation2017). The electoral turnout in local elections is higher in smaller municipalities than in the larger ones. In contrast, the electoral turnout in national elections is either positively correlated with the municipal size (as is the case of the Czech Republic, see Ryšavý and Bernard Citation2013) or not related at all (Górecki and Gendźwiłł Citation2021). This may suggest that the local elections in smaller municipalities could be perceived by their citizens as higher stake elections than the national elections. This does not necessarily negate the SOE theory; it just implies that, for a specific group of voters, local elections have certain characteristics that make these voters turn out only in local elections. Therefore, the stakes vary on a continuum between the local and national, whereas the exact position differs among the individuals, localities, and countries (Kjaer and Steyvers Citation2019).

There are several causal mechanisms theorised in the literature that explain why the municipal size is negatively associated with the local election turnout. As a municipality grows, people are less socially connected (Oliver Citation2000, 371), and, as a result, they are less informed about the local issues and politics (van Houwelingen Citation2017). This leads to lower interest and low participation in local civic affairs. Dahl and Tufte (Citation1973) argue that participation in smaller municipalities is more effective. A Danish study (Lassen and Serritzlew Citation2011) that employed a quasi-experimental research design proved that a smaller size of a municipality has a considerable and detrimental effect on internal political efficacy perceived by citizens. An additional, distinctive and quite counter-intuitive causal mechanism is suggested by the studies on the competitiveness of elections. Kjaer (Citation2007) demonstrates that higher competitiveness in smaller Danish municipalities is due to the flourishing supply side of the respective local political scenes. In the USA, Lappie and Marschall (Citation2018) found that a distinctive sense of place or local community is a predictor of competitiveness. Similar findings are presented by Voda et al. (Citation2017) concerning the Czech municipalities, stating that a small size also maximises the mobilisation of voters by increasing the (relative) number of candidates in municipalities. Derived from the rational choice perspective, the smaller the population, the higher the opportunity for a voter to cast a decisive ballot (Breux, Couture, and Goodman Citation2017; Cancela and Geys Citation2016, 268).

Likewise, political efficacy seems to be higher as a citizen of a smaller municipality can easily contact a local councillor or initiate contact with a civil servant (van Houwelingen Citation2017). The composition of small municipalities is rather homogenous as opposed to the larger ones. As argued by Denters et al. (Citation2014, 309), municipal size has a negative impact on social embeddedness. Individuals are more isolated and less interconnected with others, and shaped by social norms, values, and interactions. By contrast, in small municipalities, communities may have stronger social ties, greater familiarity with their neighbours and a greater sense of community cohesion. Political complexity is lower in small municipalities and this reduces the cost of political participation for citizens with low resources (SES) and low civic skills.

This can partially account for the higher turnout in local elections compared to national elections in smaller municipalities, despite the demographic composition of citizens. According to the Czech census data, smaller municipalities, particularly those in rural peripheries, are predominantly populated by a less educated electorate and face economic challenges, such as higher unemployment rates (Bernard Citation2018). These are the factors negatively correlated with the turnout on the individual level across various election types (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Citation1995). Indeed, the socioeconomic variables have a great effect on voter turnout in the Czech municipal elections. As argued by Školník and Haman (Citation2020), better living conditions in municipalities increase voter turnout. Additionally, the recent research by Kouba and Lysek (Citation2023) on the Czech uncontested local elections showed that the limited competition and low turnout levels occur in specific small municipalities that are characterised by a high influx of new inhabitants with a higher SES status. These municipalities are located in suburban areas of large metropolitan cities like Prague. This suggests that not only the size but also the sociodemographic composition may explain various voters’ motives.

The causal mechanisms discussed earlier relate primarily to studies conducted at the aggregated level and offer limited insights into understanding the individual-level motives of voters who choose to participate exclusively in local elections while abstaining from higher-level national participation. Consequently, we will treat municipal size as a contextual control factor and shift our focus towards investigating individual explanations for voter turnout, particularly since we rely on the data from an opinion poll survey. The central theoretical question revolves around how the group of voters who only participate in local elections differs from the abstainers and those who vote in national elections? These two contrasting categories are of particular interest as the existing literature on voting turnout provides relatively satisfactory information on the impact of individual predictors on general turnout, and because most of the factors in the academic predicting of the local level participation naturally explain the participation of the group that votes in both local and national elections. For theoretical and analytical simplicity, we refrain from the comparison of local-only voters with the group of voters voting only in national elections, and we treat this group as the category of national (and local) voters. Therefore, our focus will be on exploring the individual-level explanations of voter turnout that are locally bound and motivated, because these factors should have not only independent effects on voters` turnout but they should also theoretically explain why the citizens choose to vote only in local elections as opposed to abstaining or voting (also) in the national arena.

Complementary to the ‘small is beautiful’ argument, a typical local motive for voting is the personal proximity of a citizen to candidates. A study by Pietryka and DeBats (Citation2017) demonstrates that the individuals that are more socially proximate to elites turn out to vote at a higher rate than those without such close links. Social proximity increases people’s access to political information and thus reduces the cost of voting. It amplifies their voices within the local political system, increases their perceived political efficacy, and increases the social pressure to vote. Dodeigne et al. (Citation2022) demonstrate that proximity to and personal knowledge of a candidate was one of the self-reported reasons for voting in the recent Belgian local elections. Although the so-called friends’ and neighbourhood effects are more likely to be present in smaller rural areas, they may also be present in larger urban areas. This inherent motivation of voters may have a distinct impact on turnout, irrespective of the contextual factors related to a municipal size.

Hypothesis 1:

Citizens who know people from the local council are more likely to vote only in local elections rather than abstainers and voters turning out at national elections.

That a locally bound motives might not be entirely related to the population size is demonstrated by a recent Belgian study by Dodeigne et al. (Citation2022), which ascertained that self-proclaimed local motives play a crucial role to a majority of voters, even in largely nationalised local political systems. A significant group of voters reported that their motivation to turn out was to support the current local leaders. Continuity is preferred to change. In this regard, older voters tend to emphasise the desirability of a stable political environment. In a recent paper by Kouba and Lysek (Citation2023, 1542) on uncontested local elections, it was found that despite the fact that uncontested races in small municipalities decreased electoral turnout by 17% points, the turnout remained relatively high in municipalities composed mostly of the elderly and low SES voters, suggesting higher satisfaction with the council’s functioning. Satisfied voters are likely to declare their desire for continuity (Dodeigne et al. Citation2022). A study by Bernard (Citation2012) on the Czech municipalities ascertained that incumbents were consistently successful in local council elections. Therefore, we can expect that a significant share of voters’ motives includes retrospective evaluations of a municipality`s performance and politics, and that they generally support the current local leaders. As a result, those voters may vote only in local elections to support their favourite councillors and to prevent any changes. Most likely these voters may come from smaller municipalities and may be theoretically aligned with the core local voters who vote regularly in local elections. While the satisfaction with the activities of the municipal council may be the reason for those voting in both national and local elections, this locally bound motive may be a stronger reason for those participating only in local elections.

Hypothesis 2:

The higher the satisfaction with the activities of the council of a municipality and its management in the last election period, the higher the likelihood of voting only in local elections (as opposed to abstaining or voting in national elections).

Supporting the status quo is not the only motive for electoral participation. Alternatively, some voters seek change and thus may be motivated to turn out (Dodeigne et al. Citation2022). This is not exclusively related to dissatisfaction with local politics. Local elections under specific local context may attract individuals who want to challenge the status quo and support new ideas and perspectives into local governance. In general, elections serve to hold incumbent officials accountable, thus the voters may advocate for change by supporting the candidates who offer alternative visions or solutions to the existing local challenges. This mobilisation is frequently accompanied by an increased turnout (Holbrook and Weinschenk Citation2014). In terms of the local elections, while the support of an incumbent may be driven by core local voters, the desire for change may be driven by the voters who vote selectively. The group of ‘local-only voters’ is composed of both groups and the motive for change may attract rather fluctuating voters. In any case, these motives should strongly predict the group of ‘local-only voters’. The following hypothesis does not contradict the previous one as both relate to locally bound motives or the specific context of the local elections. These motives, consequently, may explain why the local elections are more important to voters declaring they voted only in recent local elections and deciding not to participate in the national ones.

Hypothesis 3:

The local-only voters will more likely self-report that the local elections brought a change to local politics in their town as opposed to the non-voters and voters who vote only in national elections.

Locally bound motives may explain why this group of citizens turns out in allegedly less significant local elections, but they fail to explain why these voters abstain from the national parliamentary elections. This is a perplexing question because, according to the theory of participatory democracy, citizens should acquire the skills and knowledge to participate not only in local politics but also in the national arena (Pateman Citation1970). A higher level of participation is believed to be associated with a higher trust in institutions (Putnam Citation1992), which, in turn, is an attitudinal factor explaining the voters` turnout. Yet, why does the local level participation fail to spill over easily to the higher stake national parliamentary elections? Despite the perception of the locally engaged citizens who can see the instant results of their participation and know that they can make a difference (Craig, Niemi, and Silver Citation1990), this somehow does not translate into the ‘distant’ national politics. Therefore, although we can assume that the trust in local level institutions should be positively related to a decision to turn out at the local elections (Dodeigne et al. Citation2022), a lack of trust in national institutions may separate this group of voters from those participating only in the national elections or from those participating in both the local and national elections, as it is likely that the two groups have different perceptions of the trustworthiness of national institutions. However, the voters voting only in local elections should have more trust in local institutions than abstainers, but they are unlikely to differ from them in the level of trust in the national institutions. Therefore, the following hypothesis contrasts exclusively with the group of voters voting in the national elections.

Hypothesis 4:

The higher the trust in local institutions in contrast to the national ones, the higher the likelihood of people voting only in local elections (as opposed to the voters voting in national elections).

Data and method

The Czech Republic is an ideal case for the study of discrepancies in the electoral participation across different levels of governance. The Czech Republic has one of the most fragmented municipal structures in Europe. The large number of municipalities (in total 6,252 municipalities in 2022) means that approximately 30% of the population lives in municipalities with less than 2,000 inhabitants. There was a negative turnout gap in 37% of the municipalities; the voter turnout was higher in local elections than in the most approximate parliamentary elections (Gendźwiłł and Kjaer Citation2021, 19). Therefore, almost one third of the population lives in municipalities of a size that provide ideal conditions for local participation and political mobilisation through the ‘friends-and-neighbours‘ (Górecki and Gendźwiłł Citation2021), personal contacts, and more intense social connections (Oliver Citation2000). The general voting pattern is such that in local elections the turnout is higher in smaller municipalities, but in parliamentary elections the turnout is higher in metropolitan areas. In absolute numbers, parliamentary elections have a 20% points higher turnout rate than local elections. Despite the electoral statistics, citizens regularly report higher trust in local institutions (over 65%) than in national institutions, such as the central government, the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate (varying around 30%) (CVVM Citation2023).

Both forms of elections are held under the proportional list system with a 5% electoral threshold, and they provide proportional results. In addition to the fragmented municipal structure, Czech municipal law grants large statutory cities the flexibility to sub-divide themselves into Sub-Municipal Units (SMUs), i.e., the city parts with their own sub-municipal council and mayor) to counterbalance the negative effects of size in big cities and to bring decision-making closer to the citizens (Lysek Citation2018, 58). Finally, in spite of the rules favouring political parties, independent local lists win in most municipalities, yet the penetration by nationwide parties increases with municipal size (Kostelecký Citation2007). The results of the study may be generalised particularly to countries with fragmented municipal structures and a varying turnout gap between the local and national elections. This generalisation is also relevant in the contexts where individuals tend to place a greater trust in local institutions compared to the national ones.

We employed the classic quantitative techniques of individual-level survey analysis. In comparison to the aggregate level studies, using individual data helps tackle the problem of ecological fallacy, which stems from the different sociodemographic composition of aggregated-level units. However, the disadvantage is that the respondents may tend to give invalid responses due to their social desirability bias or simply because they do not remember or do not know (see Selb and Munzert Citation2013). An individual-level data survey (a representative sample of 1023 respondents) was carried out by the Public Opinion Research Centre (CVVM) of the Sociological Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences after the local-level elections held in the Czech Republic in October 2018 (Šaradín et al. Citation2021). So far, the CVVM of the Sociological Institute of the Czech Academy of Science has had only limited knowledge about overreporting local elections. As for the elections in 2022, no survey by the CVVM was conducted. The CVVM uses its own predefined or standardised battery of questions to measure various concepts, mostly derived from large international surveys, such as the European Social Survey or World Values Survey. Typically, an index is created from a set of items as a simple sum of values and then standardised. Before the construction of an index, a factor analysis was conducted in order to examine whether the items measure the concept of interest.

Since the dependent variable is categorical (three categories of voters; see below), multinomial logistic regression has been employed. Before the calculation of a model, the regression analysis‘ assumptions were checked (including the absence of multicollinearity). Additionally, multiple imputations (n = 10) by chained equations were used to replace the missing data (see Azur et al. Citation2011). The results from the model are presented by series of plots of predicted probabilities (see Long and Freese Citation2014) using the ‘mimrgns’ package for STATA software developed by Daniel Klein (Citation2022) for imputed datasets. All non-indicator independent variables are standardised. In the Online Appendix, further information on the descriptive statistics and measurement is provided as well as an alternative model specification for a four categorical dependent variable model. The next section briefly describes the variables employed in the final model; for exact operationalisation and items used please see the Online Appendix.

Operationalisation of variables

Voter turnout

The grouping of voters is based on the questions related to the possibility of voting in the parliamentary elections to the Chamber of Deputies, and on whether a respondent voted in the recent local elections held on the 5th and 6th of October 2018. A dichotomised four-point scale regarding the hypothetical voting in general elections (yes/no) is combined with the question on local election turnout (which is already dichotomous) producing four groups of voters. For the sake of simplicity, we relax the group of citizens indicating to have cast a vote only in general elections. Hence, the dependent variable has three categories: 1) Core non-voters (N = 256); 2) Citizens voting only in local elections (N = 78); 3) Citizens voting in both general and local elections or only in general elections (N = 602). The total self-reported turnout in the 2018 local elections is 62.5%. This is higher than the actual electoral turnout in 2018, which was 47.34%.

Independent variables

We focus predominantly on the locally bound and attitudinal factors that should be related to the intention to vote only in local elections and abstain from voting in national elections. Two specific questions that CVVM incorporated into its survey are related to local politics and locally bound motives for voting. One question asks whether the respondent knows people from the local council (H1) (dummy variable, YES = 1, No = 0). Another variable of the hypothesised factors asks whether the respondent is satisfied with the activities of the council of a municipality and its management in the last election period (H2). It enters as it is (5-point ordinal scale). For the third hypothesis, we have included a dummy variable (YES = 1, No = 0) if a voter declared that the election has brought about a change to the local politics of the council (H3). Regarding the last hypothesis, two indices of institutional trust have been computed. The Trust in local institutions (H4) is measured through the questions where the respondents indicate their trust in the regional council, municipal council, the Mayor, and the chief executive. The Trust in national institutions (component of H4) is determined upon on the citizens’ responses regarding their trust in the government, the Chamber of Deputies, and the Senate. We include both indices into the model to see their marginal effect.

There are two specific controls related to the analysis of the local level of politics. The first variable, the population size as four indicator categories, 0–1999; 2000–29999; 30000–999999; and Prague). We have merged several categories of the former eight size categorical default variable by the CVVM because it was too precise for an individual level survey. A four-point scale better captures the substantial differences in local politics in the Czech Republic with the first category being regarded as small municipalities, the second category as smaller-or mid-sized municipalities, the third category as large statutory cities and the fourth one as the Capital City of Prague with the population of 1 million. The second largest city is Brno with more than 300k inhabitants. The second control variable measures satisfaction with the local election results (5-point ordinal scale). This variable is not part of the theoretical discussion but it forms a complete battery of questions by the CVVM related to the local elections. The variable may partly capture the local motives of supporting the status quo or desire for a change. But for theoretical and methodological reasons, this variable is not directly capturing each one of the two hypotheses (H3 and H4) because this retrospective evaluation may not explain the initial motives to turnout in local elections.

Since the number of studies focusing only on local voters is limited, we employed a wide range of independent control variables both sociodemographic as well as psychological and attitudinal factors. The classic sociodemographic control variables are: gender, age and SES. The SES is measured as a composite index comprising both objective and subjective questions about people s well-being, income and education attained. In addition, we also control for other attitudinal or psychological factors that, according to the literature on electoral participation, are believed to explain various turnout levels (Smets and van Ham Citation2013). The model controls for the political interest (index variable) and following politics (indicator variable) on TV, radio, in the newspapers, or on the internet. Both variables are predictors of electoral turnout and political engagement in general. The non-electoral political participation and interest in politics may be independently linked to electoral participation, regardless of the municipal size, because citizens may be active in neighbourhood councils or in the parts of large cities and country capitals divided into sub-municipal units (SMUs) (Hlepas et al. Citation2018). The index of non-electoral political participation is based on the respondents participation in the activities, such as contacting a politician; working in a political party or action group; wearing or displaying a campaign badge/sticker; signing a petition.

The literature on the electoral turnout and political participation has identified two important concepts: the internal political efficacy and external political efficacy. Internal political efficacy is the confidence in one’s own competence to participate in politics, while external political efficacy refers to the perceived ability to have an influence on politics as a consequence of the responsiveness of political institutions (Balch Citation1974; Craig, Niemi, and Silver Citation1990). People who participate more than most people, arguably, perceive themselves as having a higher political efficacy than others, i.e., they believe they can make a difference through their active involvement, and they also see higher responsiveness of the political institutions to their demands (Niemi et al. Citation1991, 1407). Since some voters prefer to turn out only in local elections, they may be more politically active and it is expected that they would participate more in their neighbourhoods than non-voters. However, as compared to national voters, they may have lower external political efficacy. A concept similar to political efficacy is the opinion leadership, which means the perception of one’s own persuasiveness on other people (see Myers and Robertson Citation1972). Finally, we also control for the level of political knowledge based on 10 statements concerning the facts about the Czech Republic and international politics. Citizens were asked to state whether the claims were true, but they were instructed not to take a guess and rather respond don’t know. The maximum number of correct and completed answers is 10 as there were 10 questions. Political knowledge is the final variable from the set of controls on political participation and political engagement.

It has been assumed in the literature that for some voters a cost and benefit analysis (Downs Citation1957; Riker and Ordeshook Citation1968) is essential in their decision to vote in local elections (see Cancela and Geys Citation2016, 268; Kouba, Novák, and Strnad Citation2021, 3). Since the PORC agency does not provide any information on the residency of anonymous respondents (also, the temporary residency and permanent residency may differ as regards the eligibility to vote in local elections), we are not able to control the patterns of political competition. Although we do not have any objective measure of the closeness of an election race, as a proxy we can measure the subjective sense of the perceived unimportance of one’s vote. A battery of questions concerning the importance of one’s vote in elections is used. The questions are part of the ‘sense of citizen duty scale’ developed by Campbell et al. (Citation1954), yet Blais (Citation2000) argues that the scale measures the perceived probabilities of being a decisive voter and the self-interest in voting (see François and Gergaud Citation2019).

Since the erosion of democracy and the rise of populism are salient topic in current academic debate (see the special issue edited by Little and Meng Citation2024), the model probe variables measuring democratic support (coded as 1 for ‘democracy is the best form of government’, 0 otherwise) and satisfaction with the functioning of democracy (4-point scale) enters as a factor variable because of the nonlinear relationship. To measure citizens’ populist attitudes, the control variable based on the question ‘The people and not the politicians should make the most important political decisions’ is included in the model. Respondents indicated their level of approval on a 5-point scale. Supposedly, a populist attitude is a concept that is not directly related to other concepts, such as political trust or external political efficacy (see Geurkink et al. Citation2020). We have no strong theoretical assumptions on the effect of democratic support and populist attitudes on voters’ decision to vote only in local elections. However, it is reasonable to suppose either no effect or that those voters will assess the democratic system more positively than non-voters.

shows descriptive statistics of the imputed data. All indices were standardised as well as the long ordinal scale (5-points). The list of items used to construct the aforesaid indices can be found in the Online Appendix.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

Results and discussion

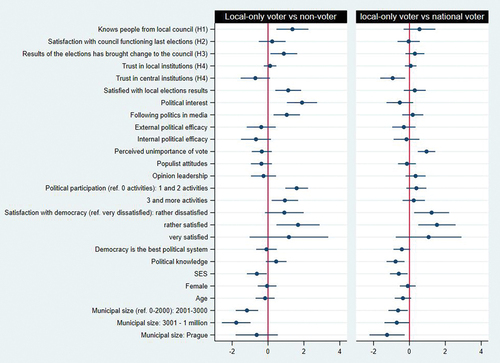

presents the outcomes of a multinomial logistic regression model. In this analysis, the goal is to compare only the local voters with two distinct reference groups: non-voters and voters in national elections. To achieve this, the non-voters and voters in national elections have been designated as the contrasting reference categories when examining the results for ‘local-only voters’. The figure illustrates the results of a single multinomial regression model with the coefficients displayed in two separate subgraphs. These subgraphs enable precise comparisons to be made between ‘local-only voters’ and both reference groups, non-voters and voters in national elections (similarly to classical logistic regression output). For easier comparison, the non-binary continuous and ordinal variables were standardised by a factor of two standard deviations, following the approach suggested by Andrew Gelman (Citation2008). This scaling method makes the scaled variables approximately comparable to dichotomous variables, such as gender.

Figure 2. Multinomial logistic regression.

The results generally support the previous findings that the likelihood of people voting only in local elections as opposed to abstainers decreases with an increased municipal size (Górecki and Gendźwiłł Citation2021), yet for the Capital City of Prague, this is not statistically significant. However, when contrasting ‘local-only voters’ with ‘only national voters’, the respondents living in Prague were less likely to be ‘local-only voters’ rather than ‘voters in both elections’. While the municipal size is a good predictor of local-level participation as opposed to non-participation, it performs poorly in differentiating between ‘local-only voters’ and those who vote either in national elections or both. Although the municipal size is a key variable in explaining the local election turnout, it only indirectly explains individual motives for turning out only in local elections.

In examining how locally bound motives or attitudinal factors predict why people vote only in local elections, we ascertained support for Hypothesis 1. The individuals who know local councillors are more likely to be ‘local-only voters’ compared to ‘abstainers’. The individuals living in smaller municipalities are more likely to be acquainted with local councillors and may feel socially obliged to support their neighbours and friends running in local elections. Interestingly enough, there was no statistically significant difference in the level of knowing councillors between the individuals voting in both local and national elections and those who are ‘local-only voters’.

There are two additional locally bound motives that can provide strong reasons for individuals to vote exclusively in local elections: a desire for keeping the status quo or a desire for change. The data predominantly supports the latter. While the satisfaction with the functioning of a council (H2) does not predict why citizens voted in local elections, those who believe that the election results have brought about a change in the local council (H3) are more likely (with a factor of 0.881 in log odds units) to be ‘local-only voters’ rather than ‘abstainers’. It is important to note that the post-election evaluation of the council’s change is an imperfect measure of motives and their connection to the decision to vote, as the election outcomes can differ from a voter’s desire for change. Nevertheless, the strong associations found with ‘local-only voters’ suggest that a desire for change may be a motivating factor that mobilises former non-voters to participate in local elections and potentially constitutes a majority of those who vote exclusively in local elections.

This conclusion is further supported by a supplementary control variable measuring the satisfaction with the results of local elections. The individuals who reported higher satisfaction with the local election outcomes are more likely to be ‘local-only voters’ compared to ‘abstainers’ although no difference has been observed among the individuals voting in both elections. While the satisfaction with the election results encompasses various aspects of voters’ motives, including the desire for change or keeping the status quo, it indicates that the local context effectively mobilises voters to participate in allegedly less significant elections.

Locally bound motives effectively account for the differences between ‘local-only voters’ and those who do not participate in any elections. However, as expected, they perform poorly in distinguishing ‘local-only voters’ from the voters who participate in both national and, at the same time, in local elections. The distinction does not stem from a higher level of trust in local institutions as the ‘local-only voters’ do not differ significantly from other voter groups in terms of trust in local government institutions (H4). Similarly, they do not exhibit a greater level of trust in local politics compared to the voters who participate in both national and local elections. In fact, there is no discernible difference between all of the groups in terms of trust in local politics. This could be attributed to the fact that local institutions enjoy a high level of trust among the general public, which appears to be evenly distributed across various societal groups, regardless of their electoral participation. However, the group of ‘local-only voters’ exhibits significantly less trust in national institutions compared to those who participate in both national and local elections. The lack of trust in national institutions (H4) explains their decision to abstain from what is perceived as more significant national elections. This variable is key in understanding why ‘local-only voters’ refuse to participate at the national level, even when controlling for the municipal size. The model suggests that the ‘local-only voters’ might have even lover trust in national institutions than the core abstainers, yet due to the limited size of an opinion poll survey, the coefficient is not statistically significant to zero.

An additional control variable provides support for the assertion that these voters perceive national politics as distant and believe that their participation in national elections would not make a difference. The higher the perception that one’s vote is insignificant (vote unimportance), the greater the likelihood (by 0.954 log odds) that a citizen will vote exclusively in local elections rather than participating in both national and local elections. This finding is somewhat perplexing because this perception is typically associated with abstaining from all elections. Thus, it appears that for some voters, local elections are not necessarily deemed more important than national elections; rather, they feel that they cannot effectively engage in national politics, although they may effectively participate at the local community level.

As indicated by other control variables, this group of citizens who vote only in local elections exhibits several distinct characteristics. While they do not vote in national elections, they indeed seem to have a better knowledge of their community and local leaders (see Pietryka and DeBats Citation2017), and it is likely that they feel more related to politics and politicians at the local level. Being satisfied with local politics and trustful to local institutions, these voters may also participate in civic duties (see François and Gergaud Citation2019). Although they do not possess more political knowledge about the Czech political system and international politics than abstainers, they display a greater interest in politics and engage at higher levels of non-electoral participation at the local level, involving one or two activities. Thus in contrast to core abstainers, they actively acquire local political information and follow municipal politics. Taken together, these factors contribute to their decision to participate in local elections rather than national elections, which they may perceive as more distant and complex. Overall, local motives, such as a desire for change in local politics, knowledge of the candidates, satisfaction with the results, and distrust of national institutions are the factors that voters consider to be important in their decision to vote. Hence, local elections are not always ‘second-order‘ elections to all citizens.

In terms of democratic theory, it appears that ‘local-only voters’ express a higher level of trust in the democratic system compared to abstainers. The model demonstrates that citizens who express a moderate level of satisfaction with democracy on a 4-point scale are more likely to be voting exclusively in local elections, as opposed to abstaining. Intriguingly, neither external political efficacy nor populist attitudes (people should decide) (Geurkink et al. Citation2020) explain why people vote only in local elections. These individuals might be categorised as apathetic or disenchanted with national politics, displaying a degree of scepticism, yet not experiencing complete alienation (see Christensen Citation2016). This outcome carries promising implications for the potential influence of local participation on overall political satisfaction. However, the absence of observable effects from variables measuring political discontent could be attributed to the possibility that voters in national parliamentary elections may also include highly mobilised individuals who, despite their alienation, choose to express their discontent by voting for populist parties. Given the fact that ‘local-only voters’ also exhibit a higher level of disbelief in the impact of their own vote, it is less likely that their decision to abstain from national elections is driven primarily by political alienation.

When comparing these Czech ‘local-only voters’ to the findings of the Swiss study by Sciarini et al. (Citation2015, 89), it can be inferred that the Czech ‘local-only voters’ align more closely with the core voters rather than abstainers in terms of political interest, political competence, and participation. While this is a secondary finding of the present study, it holds significant importance for the ongoing debate regarding the impact of local-level participation on the democratic support by citizens of low socioeconomic status residing in rural areas. The Czech data reveals that the group of ‘local-only voters’ possesses the same socioeconomic status as the non-voters but a lower socioeconomic status when compared to national voters. This finding is consistent with other studies as the Danish (Bhatti et al. Citation2019) and Swedish (Dehdari, Meriläinen, and Oskarsson Citation2021) cases demonstrated that a disproportionately higher number of SES and older citizens participated in all types of elections, while the selective voters tended to have the sociodemographic characteristics similar to those of abstainers.

Conclusion

A significant number of citizens participate only in local elections and do not participate in parliamentary elections. The objective of this study was to shed the light on the characteristics of these voters, understand their motives for participating solely in local elections, and explore how they differ from other voter groups. Typically, the voter voting only in local elections usually resides in smaller municipalities. While this finding may not come as a surprise, the data also indicates that some locally bound motives and the local context play a significant role in driving the participation of this particular group of citizens, distinguishing them from the abstainers and individuals who vote solely in national elections. Specifically, ‘local-only voters’ express familiarity with local councillors and generally exhibit higher levels of satisfaction with the outcomes of local elections. Additionally, for some of these voters, the desire to challenge the status quo appears to be a motivating factor, as they more frequently reported that the elections have brought about changes in local council politics.

The overall findings of the model indicate that majority of the respondents who voted exclusively in local elections showed a preference for change rather than maintaining the status quo as there was no significant association between their satisfaction with the council’s performance in the previous electoral cycle. However, it is important to note that among some of these ‘local-only voters’, their motivation to turn out may have been to support the current council politics and the councillors they personally know. Similarly, as per the respondents who expressed high satisfaction with the election results, their primary motive to vote might have been to endorse the existing council politics. Nevertheless, it is crucial to acknowledge that this retrospective evaluation of locally bound motives does not (methodologically) precisely distinguish between the desire for change and the support of the status quo as mobilising electoral mechanisms. Therefore, future studies utilising panel data and longitudinal models would be valuable in investigating whether the core local voters tend to support the status quo, while the selective voters are more inclined towards desiring change in local politics.

Despite the mobilisation of this group of citizens at the local level, their opinions of and attitudes towards national politics and democracy are rather complex. The primary distinction between the ‘local-only voters’ and those who vote in both local and national elections lies in their distrust of national institutions and their perception that their vote does not hold significance at the national level. While this result may raise concerns, it might not pose a significant threat to democracy. Although this locally mobilised group of citizens appears to be less supportive of central government institutions, it expresses a greater overall satisfaction with the state of democracy and politics in their local communities compared to core abstainers. Moreover, this group demonstrates a higher rate of non-electoral political participation and a greater interest in politics than non-voters. Furthermore, in terms of sociodemographic characteristics, these citizens bear resemblance to abstainers, as both groups have a lower socioeconomic status than core voters (Bhatti et al. Citation2019; Dehdari, Meriläinen, and Oskarsson Citation2021). However, they do not differ significantly from the core voters in several key attitudinal aspects regarding the democratic theory.

Therefore, it seems that the local participation, interest in local community and local politics may foster democratic attitudes for the low SES citizens, despite the fact that they are not mirrored in the decision to vote at national elections. From the macro-perspective, we can speculate that the fragmented municipal Czech structure and the 216,472 candidates running in the 2018 local elections could be a structural factor that may explain why the state of democracy is, ultimately, far better than in the neighbouring countries where the local politics is limited in many ways. Furthermore, it is worrying that a similar size group of voters who only turn out for national elections seems to be indifferent to local politics. A practical implication of this study might be that in large cities the local political elite should institutionally enhance the citizens‘ opportunities in the local level participation – for example, by creating SMUs (Hlepas et al. Citation2018), or neighbourhood councils (Kersting and Vetter Citation2003, 15), or by improving their own performance in terms of democratic innovations, such as participatory budgeting and urban planning. Further studies on voters participating only at the local level under different institutional and societal context are thus more than welcome.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (850.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2024.2341234

Additional information

Funding

References

- Azur, M. J., E. A. Stuart, C. Frangakis, and P. J. Leaf. 2011. “Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations: What is it and How Does it Work?” International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 20 (1): 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.329.

- Baekgaard, M., C. Jensen, P. B. Mortensen, and S. Serritzlew. 2014. “Local News Media and Voter Turnout.” Local Government Studies 40 (4): 518–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2013.834253.

- Balch, G. I. 1974. “Multiple Indicators in Survey Research: The Concept Sense of Political Efficacy.” Political Methodology 1 (2): 1–43.

- Bernard, J. 2012. “Individuální charakteristiky kandidátů ve volbách do zastupitelstev obcí a jejich vliv na volební výsledky.” Sociologický časopis/Czech Sociological Review 48 (4): 613–640. https://doi.org/10.13060/00380288.2012.48.4.05.

- Bernard, J. 2018. “Rural Quality of Life–Poverty, Satisfaction and Opportunity Deprivation in Different Types of Rural Territories.” European Countryside 10 (2): 191–209. https://doi.org/10.2478/euco-2018-0012.

- Bhatti, Y., J. O. Dahlgaard, J. H. Hansen, and K. M. Hansen. 2019. “Core and Peripheral Voters: Predictors of Turnout Across Three Types of Elections.” Political Studies 67 (2): 348–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321718766246.

- Blais, A. 2000. To Vote or Not to Vote?: The Merits and Limits of Rational Choice Theory. Pittsburgh, USA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Breux, S., J. Couture, and N. Goodman. 2017. “Fewer Voters, Higher Stakes? The Applicability of Rational Choice for Voter Turnout in Quebec Municipalities.” Environment & Planning C Politics & Space 35 (6): 990–1009. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X16676272.

- Campbell, A., G. Gurin, and W. E. Miller. 1954. The voter decides. New York: Row, Pererson & Co.

- Cancela, J., and B. Geys. 2016. “Explaining Voter Turnout: A Meta-Analysis of National and Subnational Elections.” Electoral Studies 42:264–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2016.03.005.

- Christensen, H. S. 2016. “All the Same? Examining the Link Between Three Kinds of Political Dissatisfaction and Protest.” Comparative European Politics 14 (6): 781–801. https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2014.52.

- Craig, S. C., R. G. Niemi, and G. E. Silver. 1990. “Political Efficacy and Trust: A Report on the NES Pilot Study Items.” Political Behavior 12 (3): 289–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00992337.

- CVVM. 2023. “Czech Public Attitudes to Foreigners.” https://cvvm.soc.cas.cz/en/press-releases/political/politicians-political-institutions/5675-czech-publics-attitudes-to-foreigners-2.

- Dahl, R. A. 1989. Democracy and Its Critics. New Haven, USA: Yale University Press.

- Dahl, R. A., and E. R. Tufte. 1973. Size and Democracy. Stanford, USA: Stanford University Press.

- Dehdari, S. H., J. Meriläinen, and S. Oskarsson. 2021. “Selective Abstention in Simultaneous Elections: Understanding the Turnout Gap.” Electoral Studies 71:102302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102302.

- Denters, B. 2002. “Size and Political Trust: Evidence from Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway, and the United Kingdom.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 20 (6): 793–812. https://doi.org/10.1068/c0225.

- Denters, B., M. Goldsmith, A. Ladner, P. E. Mouritzen, and L. E. Rose. 2014. Size and Local Democracy. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Dodeigne, J., M. Reuchamps, K. Steyvers, and F. Teuber. 2022. “Local Voters Have Their Reasons. Mapping Voting Motives in Local Elections in Belgium.” Swiss Political Science Review 28 (4): 624–652. https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12522.

- Downs, A. 1957. An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper & Row.

- François, A., and O. Gergaud. 2019. “Is Civic Duty the Solution to the Paradox of Voting?” Public Choice 180 (3–4): 257–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-018-00635-7.

- Gelman, A. 2008. “Scaling Regression Inputs by Dividing by Two Standard Deviations.” Statistics in Medicine 27 (15): 2865–2873. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.3107.

- Gendzwill, A. 2021. “Local Autonomy and National–Local Turnout Gap: Higher Stakes, Higher Turnout?” Regional & Federal Studies 31 (4): 519–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2019.1706496.

- Gendźwiłł, A., and U. Kjaer. 2021. “Mind the Gap, Please! Pinpointing the Influence of Municipal Size on Local Electoral Participation.” Local Government Studies 47 (1): 11–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2020.1777107.

- Geurkink, B., A. Zaslove, R. Sluiter, and K. Jacobs. 2020. “Populist Attitudes, Political Trust, and External Political Efficacy: Old Wine in New Bottles?” Political Studies 68 (1): 247–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321719842768.

- Górecki, M. A., and A. Gendźwiłł. 2021. “Polity Size and Voter Turnout Revisited: Micro-Level Evidence from 14 Countries of Central and Eastern Europe.” Local Government Studies 47 (1): 31–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2020.1787165.

- Hlepas, N., N. Kersting, S. Kuhlman, P. Swianiewicz, and F. Teles, ed. 2018. Sub-Municipal Governance in Europe: Decentralization Beyond the Municipal Tier. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Holbrook, T. M., and A. C. Weinschenk. 2014. “Campaigns, Mobilization, and Turnout in Mayoral Elections.” Political Research Quarterly 67 (1): 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912913494018.

- Kersting, N., and A. Vetter, ed. 2003. Reforming Local Government in Europe. Wiesbaden, DE: Springer Fachmedien.

- Kjaer, U. 2007. “The Decreasing Number of Candidates at Danish Local Elections: Local Democracy in Crisis?” Local Government Studies 33 (2): 195–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930701198599.

- Kjaer, U., and K. Steyvers. 2019. “Second Thoughts on Second-Order? Towards a Second-Tier Model of Local Government Elections and Voting.” In The Routledge Handbook of International Local Government, edited by R. Kerley, J. Liddle, and P. T. Dunning, 405–417. London, UK: Routledge.

- Klein, D. 2022. “MIMRGNS: Stata Module to Run Margins after mi Estimate” Statistical Software Components S457795. Boston College Department of Economics. Accessed July 25, 2022.

- Kostelecký, T. 2007. “Political Parties and Their Role in Local Politics in the Post-Communist Czech Republic.” In Local Government Reforms in Countries in Transition, edited by F. Lazin, M. Evans, V. Hoffmann-Martinot, and H. Wollmann, 121–139. Lanham, USA: Lexington Books.

- Kouba, K., and J. Lysek. 2023. “The Return of Silent Elections: Democracy, Uncontested Elections, and Citizen Participation in Czechia.” Democratization 30 (8): 1527–1551. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2023.2246148.

- Kouba, K., J. Novák, and M. Strnad. 2021. “Explaining Voter Turnout in Local Elections: a Global Comparative Perspective.” Contemporary Politics 27 (1): 58–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2020.1831764.

- Lappie, J., and M. Marschall. 2018. “Place and Participation in Local Elections.” Political Geography 64:33–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2018.02.003.

- Lassen, D. D., and S. Serritzlew. 2011. “Jurisdiction Size and Local Democracy: Evidence on Internal Political Efficacy from Large-Scale Municipal Reform.” American Political Science Review 105 (2): 238–258. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000305541100013X.

- Lefevere, J., and P. Van Aelst. 2014. “First-Order, Second-Order or Third-Rate? A Comparison of Turnout in European, Local and National Elections in the Netherlands.” Electoral Studies 35:159–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2014.06.005.

- Little, A. T., and A. Meng. 2024. “What We Do and Do Not Know About Democratic Backsliding.” PS: Political Science & Politics 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096523001038.

- Long, J. S., and J. Freese. 2014. Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables Using Stata. Texas, USA: Stata Press.

- Lysek, J. 2018. “The “Little Town-Halls” in the Czech Republic: An Unexploited Potential of Functional Decentralization.” In Sub-Municipal Governance in Europe, edited by N. Hlepas, N. Kersting, S. Kuhlman, P. Swianiewicz, and F. Teles, 41–68. London: Palgrave-Macmillan.

- Maškarinec, P. 2022. “Mapping the Territorial Distribution of Voter Turnout in Czech Local Elections (1994–2018) Spatial Dimensions of Electoral Participation.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 55 (3): 163–180. https://doi.org/10.1525/cpcs.2022.1706946.

- Morlan, R. L. 1984. “Municipal Vs. National Election Voter Turnout: Europe and the United States.” Political Science Quarterly 99 (3): 457–470. https://doi.org/10.2307/2149943.

- Myers, J. H., and T. S. Robertson. 1972. “Dimensions of Opinion Leadership.” Journal of Marketing Research 9 (1): 41–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224377200900109.

- Niemi, R. G., C. Stephen, F. M. Craig, and F. Mattei. 1991. “Measuring Internal Political Efficiency in the 1988 National Election Study.” American Political Science Review 85 (4): 1407–1413. https://doi.org/10.2307/1963953.

- Oliver, J. E. 2000. “City Size and Civic Involvement in Metropolitan America.” The American Political Science Review 94 (2): 361–373. https://doi.org/10.2307/2586017.

- Pateman, C. 1970. Participation and Democratic Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pietryka, M. T., and D. A. DeBats. 2017. “It’s Not Just What You Have, but Who You Know: Networks, Social Proximity to Elites, and Voting in State and Local Elections.” The American Political Science Review 111 (2): 360–378.

- Putnam, R. D. 1992. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton, NJ USA: Princeton University Press.

- Rallings, C., M. Temple, and M. Thrasher. 1996. “Participation in Local Elections.” In Local Democracy and Local Government. Government Beyond the Centre, edited by L. Pratchett and D. Wilson, 62–83. London: Palgrave-Macmillan.

- Rallings, C., and M. Thrasher. 2005. “Not All ‘Second-Order’ Contests are the Same: Turnout and Party Choice at the Concurrent 2004 Local and European Parliament Elections in England.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 7 (4): 584–597. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-856x.2005.00207.x.

- Rallings, C., and M. Thrasher. 2007. “The Turnout ‘Gap’ and the Costs of Voting – A Comparison of Participation at the 2001 General and 2002 Local Elections in England.” Public Choice 131 (3–4): 333–344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-006-9118-9.

- Reif, K., and H. Schmitt. 1980. “Nine Second-Order National Elections – A Conceptual Framework for the Analysis of European Election Results.” European Journal of Political Research 8 (1): 3–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.1980.tb00737.x.

- Riker, W. H., and P. C. Ordeshook. 1968. “A Theory of the Calculus of Voting.” American Political Science Review 62 (1): 25–42. https://doi.org/10.2307/1953324.

- Rosenstone, S. J., and J. M. Hansen. 1993. Mobilization, Participation, and Democracy in America. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company.

- Ryšavý, D., and J. Bernard. 2013. “Size and Local Democracy: The Case of Czech Municipal Representatives.” Local Government Studies 39 (6): 833–852. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2012.675329.

- Šaradín, P., T. Lebeda, J. Lysek, M. Soukop, D. Ostrá, and E. Lebedová. 2021. “Post-Election Survey Data: Local Democracy and the 2018 Local Elections in the Czech Republic.” Data in Brief 36:107039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2021.107039.

- Schakel, A. H., and C. Jeffery. 2013. “Are Regional Elections Really ‘Second-Order’ Elections?” Regional Studies 47 (3): 323–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.690069.

- Sciarini, P., F. Cappelletti, A. C. Goldberg, and S. Lanz. 2015. “The Underexplored Species: Selective Participation in Direct Democratic Votes.” Swiss Political Science Review 22 (1): 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12178.

- Selb, P., and S. Munzert. 2013. “Voter Overrepresentation, Vote Misreporting, and Turnout Bias in Postelection Surveys.” Electoral Studies 32 (1): 186–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2012.11.004.

- Školník, M., and M. Haman. 2020. “Socioeconomic or Political Variables? The Determinants of Voter Turnout in Czech Municipalities.” Sociológia - Slovak Sociological Review 52 (3): 222–244. https://doi.org/10.31577/sociologia.2020.52.3.10.

- Smets, K., and C. van Ham. 2013. “The Embarrassment of Riches? A Meta-Analysis of Individual-Level Research on Voter Turnout.” Electoral Studies 32 (2): 344–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2012.12.006.

- Swianiewicz, P., ed. 2002. Consolidation or Fragmentation? The Size of Local Governments in Central and Eastern Europe. Budapest: LGI - Open Society Institute.

- van Houwelingen, P. 2017. “Political Participation and Municipal Population Size: A Meta-Study.” Local Government Studies 43 (3): 408–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2017.1300147.

- Verba, S., and N. H. Nie. 1972. Participation in America. Political Democracy and Social Equality. New York: Harper & Row.

- Verba, S., K. Schlozman, and H. E. Brady. 1995. Voice and Equality. Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Voda, P., P. Svačinová, A. Smolková, and S. Balík. 2017. “Local and More Local: Impact of Size and Organization Type of Settlement Units on Candidacy.” Political Geography 59:24–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.02.010.

- Wolfinger, R. E., and S. J. Rosenstone. 1980. Who Votes? New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.