?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Policies regulating individuals convicted of sexual offenses (ICSOs) are widely supported, despite little empirical evidence that they promote public safety. While research suggests this support is unresponsive to counterevidence, the mechanisms underlying these findings remain unclear. Here we consider whether assessments of an expert’s credibility are impacted by advocating for non-punitive approaches to ICSOs (vs. individuals convicted of drunk driving [ICDDs]), and if these effects carry over to subsequent, unrelated, claims by that expert. Based on a factorial survey experiment with a web-based opt-in panel of US adults, we use structural equation modeling to estimate associations between offense population and the expert source of a claim, perceptions of the expert’s credibility, and subsequent belief. We find that advocating rehabilitation for ICSOs reduces an expert’s credibility compared to advocating similar claims for ICDDs. Respondents subsequently express less belief in that expert’s claim, and this effect carries over to subsequent, unrelated claims.

Policies enacted to regulate the behavior of individuals convicted of sexual offenses (ICSOs) in the community enjoy widespread support among the public (Mears et al., Citation2008). Prominent examples—such as sex offender residence restrictions (SORR)—are routinely endorsed by upwards of 75% of respondents across statewide (Mancini et al., Citation2010) and national survey samples (Harris & Socia, Citation2016; Rydberg et al., Citation2018). Yet, this high level of support exists despite a lack of empirical evidence suggesting that these policies are effective in enhancing public safety (Huebner et al., Citation2014). The deficit model of science communication (Bauer et al., Citation2007) assumes that to the extent that the general public is unaware of criminological evidence on ICSO policies, exposure to this information should pull general attitudes closer to those of scientific experts (Hart & Nisbet, Citation2012). However, multiple surveys have suggested that the public would hypothetically continue to support such policies even if there was no scientific evidence that they work (Levenson et al., Citation2007; Socia & Harris, Citation2016). Recent survey experiments confirm this, as individuals’ support for policies such as SORR and sex offender registration and notification (SORN) was unresponsive to counterevidence suggesting their ineffectiveness (Campbell & Newheiser, Citation2019; Koon-Magnin, Citation2015). Further, support did not vary when manipulating either the nature of counterevidence (i.e. public safety or collateral consequences), or how that counterevidence was presented (Rydberg et al., Citation2018).

It is important to emphasize that this situation is not specific to the public’s response to ICSO policy. Research on jurors’ reactions to expert testimony finds that while jurors typically misunderstand how factors such as human memory can impact eyewitness testimony in trials (Schmechel et al., Citation2005), being presented with scientific evidence on the matter does little to change either the juror’s confidence in eyewitness identification or the verdict towards the defendant (Blandon-Gitlin et al., Citation2011). There are parallels between this state of affairs and science communication in other areas, such as climate science and vaccine hesitancy, where there has been incongruence between public perception and broad scientific consensus (Gust et al., Citation2008; Kvaløy et al., Citation2012).

To date, the mechanisms underlying this persistent public support for ICSO policies in the face of criminological evidence are not well understood. In examining the responsiveness of public opinion on climate change to research, one line of inquiry focuses on how individuals assess the credibility of expert claims about policy positions. Such research finds that the public does not passively incorporate expert claims into their own opinions, but rather relies on relatively superficial heuristics and cognitive biases to determine whether an expert is to be believed (Brennan, Citation2020). Importantly, when expert claims contradict strongly held beliefs, individuals engage in motivated reasoning to preserve their preferred orientation (i.e. their initial beliefs), including negative evaluations of the sources’ credibility (Vraga et al., Citation2018).

This prior research presents important implications for criminological science communication and the potential for evidence-based practices to be implemented. Public support, or the lack thereof, can enhance or constrain the capacity for evidence-based criminal justice reform (Apel, Citation2013). Yet it is unclear whether assessments of source credibility are a latent construct underlying high support for ICSO policies even in the face of empirical evidence. Given the public generally favors punitive responses to ICSOs (Pickett et al., Citation2013), but also stigmatized groups more generally (e.g. “opioid users” [Kennedy-Hendricks et al., Citation2017], “the homeless” [Clifford & Piston, Citation2017]), advancing policies that are less punitive towards stigmatized groups, but more impactful towards public safety, may be risky to the public credibility of criminologists and other social science experts (Beall et al., Citation2017). Another troubling possibility is that criminologists who make empirically accurate (but unpopular) claims about an issue may subsequently find their credibility questioned when it comes to claims regarding different issues on crime and justice policy.

In the current research, we employ a factorial survey experiment with a nationally representative US-based online opt-in panel to address three primary research objectives:

To test whether a claim advancing a less-punitive approach towards ICSOs results in a negative assessment of an experts’ credibility, as compared to a similar claim about individuals convicted of drunk driving (ICDDs).

To consider whether this effect varies depending on the nature of the expert presenting the claim (academic knowledge versus practitioner experience).

To determine whether this impact on credibility carries over to respondent beliefs about the expert’s position on a subsequent unrelated criminal justice issue.

While we focus on the subject of ICSOs, the implications of this study speak to larger concerns around credibility of criminal justice experts and public willingness to change their opinions about criminal justice issues. As the criminology and criminal justice disciplines seek to educate the public and influence policy, our study provides important insight into barriers and pathways for success.

Empirical Background

A small body of survey evidence has gauged the extent to which the public would hypothetically endorse a variety of ICSO policies even if there was no evidence that they increased public safety. For instance, 73% of a convenience sample of Florida residents at least partially agreed with the statement “I would support [sex offender policies] even if there is no scientific evidence showing that they reduce sexual abuse” (Levenson et al., Citation2007). Similarly, 51% of a sample of Ohio residents agreed with the notion that ICSO policies should be enforced even if there is no scientific evidence in their favor (Levenson et al., Citation2014). A more recent inquiry using a representative online panel of US adults observed that 58% of respondents would not change their views of SORN based on research findings (Socia & Harris, Citation2016).

Although these previous examples reflect considerations in hypothetical scenarios, more recent studies have progressed this line of research by attempting to determine whether support for ICSO policies can be changed via actual presentation of evidence. Using convenience samples of Alabama residents, Koon-Magnin (Citation2015) surveyed support for a variety of community notification-related ICSO policies (e.g. fliers, neighborhood meetings), while randomly prompting some respondents with a disclaimer that there is no scientific evidence that these policies reduced sexual abuse. They observed that receiving the prompt did not influence support for the policies, with both groups expressing a high degree of support for all approaches. However, Campbell and Newheiser (Citation2019) took an additional step of measuring support for SORN and SORR both before and after presenting counterevidence suggesting their ineffectiveness, which was tailored based on respondents’ initial reasons for supporting these policies (e.g. prevent sex crimes). In a series of experiments with their crowdsourced sample, Campbell and Newheiser (Citation2019) found that presenting counterevidence reduced support for these policies, but not enough to generate negative opinions—instead, average post-manipulation support for the policies remained neutral.

Theoretical Background

Crime Control Theater and Science Skepticism

What theoretical mechanisms can explain the lack of public opinion response to evidence suggesting ICSO policies are ineffective? An initial factor centers on the public’s motivations for supporting these policies, considering whether they are instrumental in nature. Understanding ICSO policies as instances of crime control theater offers a useful perspective, as such policies are designed to give the appearance of addressing crime, without typically being research-based or effective. Thus, these policies generate public support precisely because the value is primarily symbolic (DeVault et al., Citation2016; Sample et al., Citation2011). Indeed, if policy support largely serves symbolic benefits, then support for punitive ICSO approaches would be de-coupled from their actual effectiveness, and no counterevidence would shift this support. In a similar vein, the public is more likely to support policies they perceive as intuitively reasonable, regardless of how effective they believe they are (Tyler, Citation2006). Several studies lend credence to these ideas (e.g. Levenson et al., Citation2014; Schiavone & Jeglic, Citation2009; Tewksbury et al., Citation2011), observing that while both the public and practitioners are skeptical about the efficacy of ICSO policies, they simultaneously offer them broad support.

On the other hand, if instrumental goals were to underlie some of the support for punitive ICSO policies, how can we explain the public’s resistance to scientific counterevidence? Skepticism in science offers a potential avenue. Since the early 2000s, public distrust in science in the US has grown, especially among conservatives (Gauchat, Citation2012), and particularly in politicized arenas such as climate change and vaccination (Rutjens et al., Citation2018, Citation2021). As applied to criminal justice policies, penal populist discourse has disparaged the potential of professional (detached) experts to provide guidance to crime control efforts (Garland, Citation2021; Stuntz, Citation2011). Instead, street-oriented practitioners—such as experienced police officers—have been presented by the popular media as the most legitimate sources of knowledge on crime (Stone & Socia, Citation2019; Uggen & Inderbitzin, Citation2010), especially on matters of crime control policy (Welch et al., Citation1998).

To explore this issue, Rydberg et al. (Citation2018) considered whether opinion on SORR could be shifted by manipulating the attributed source of a claim on the policy’s ineffectiveness. The results of the survey experiment suggested that the overall high level of support or strong support for SORR (83%) did not meaningfully vary when the attributed source of the claim was a criminal justice practitioner (parole officer or department crime analyst) versus a summary of scientific evidence. Similarly, Krauss et al. (Citation2022) observed that both factual and more emotionally engaged videos were able to reduce respondent support for ICSO policies, but did not shift evaluations of policy effectiveness. These findings further necessitate exploration of latent constructs underlying respondents’ processing of claims regarding ICSO policies. That the expert source did not seem to impact the (in)effectiveness of the counterevidence raises additional questions regarding how respondents were processing the information presented. One possibility is that respondents used these instances to critically evaluate the credibility of the expert sources.

Evaluations of Expert Credibility – the Roles of Dissonance and Congruity

A relatively unexamined consideration in the crime control theater-counterevidence research is how respondents perceive the credibility of the information and its source. In the Campbell and Newheiser (Citation2019) experiment, opinions did not change even when the respondents viewed the counterevidence as credible. Prior research suggests that the public tends to focus on the credibility of the messenger as a heuristic for deciding whether they will accept the message (i.e. a scientific claim to knowledge), as opposed to directly judging the content of the claim itself (Brewer & Ley, Citation2013). Individuals will have imperfect information on any given issue and rely on experts to various degrees to form their own position (Lachapelle et al., Citation2014). However, what happens when an individual receives a message from an expert that contradicts an existing belief, such as that concerning the effectiveness of ICSO policies?

Cognitive dissonance theory in social psychology (Festinger, Citation1964) posits that inconsistencies between cognitions—such as supporting an ICSO policy and receiving a message suggesting such a policy is ineffective—produces a state of psychological discomfort which individuals will attempt to reconcile. This reconciliation can be accomplished through several avenues, such as the individual updating their beliefs in light of new information. However, Festinger (Citation1964) suggests that it is more likely that respondents will form negative judgements about the messenger, because it is easier to dismiss the source than to either specifically counter-argue the content of the message or to change ones’ beliefs on the subject matter (Kotcher et al., Citation2017). Yet in forming these judgements, laypersons are also typically ill-suited for evaluating the credibility of scientific experts. The public tends to have little familiarity with scientists, and thus their perceptions of scientific goals and political orientations are based on superficial cognitive biases stemming from the interaction between the source, the message, and the current beliefs of the respondent (Brennan, Citation2020). For instance, confirmation bias may lead respondents to reject experts who present messages incongruent with their current beliefs, while still relying on experts for matters where the respondent is ambivalent about the argument being made (Nickerson, Citation1998; Inglis & Mejia-Ramos, Citation2009). As it relates to ICSOs, the strong baseline support for punitive ICSO policies may result in respondents dismissing expert positions of leniency on the matter regardless of the source.

If the public negatively evaluates the credibility of the source to the point of rejecting the source’s claim about a subject (in this case, ICSO policies), then a troubling implication is that this decreased credibility may “stick” to the source when they make subsequent, even unrelated claims. A relevant theoretical perspective is offered by congruity theory in communication research (Osgood & Tannenbaum, Citation1955). Similar to cognitive dissonance, congruity theory offers a model for directionality in how individuals resolve information inconsistency. The theory posits that when an individual receives communication from a source concerning negative information about a subject, the extent of attitude change will depend on the individual’s valence towards both the messenger and the subject. If the individual likes the subject, then to maintain consistency, the (negative) attitude change will be “absorbed” by the messenger (Tannenbaum & Gengel, Citation1966). This impact on source credibility is consistent with the marketing concept of “brand-to-endorser” reverse meaning transfer effects (McCracken, Citation1989), in that negative perceptions of a faulty or undesirable product may transfer to negatively influence perceptions of the celebrity’s endorsers credibility.

Design Choices and Hypotheses

Drawing on these theoretical perspectives, to test whether expert statements concerning a stigmatized group would produce a negative assessment of credibility, and what the potential implications of such effects may be, the current research compares messages concerning the effectiveness of ICSO policies using a similar but relatively less stigma-driven comparison condition. As highlighted by Levenson et al. (Citation2014), individuals convicted of drunk driving (ICDDs) and the laws regulating these behaviors provide a useful comparison to ICSOs in a number of respects. Like sex crimes, drunk driving is a behavior for which a motivated public, particularly parents (e.g. Mothers Against Drunk Driving), has been successful in constructing an array of specialized policy responses (e.g. lower blood alcohol thresholds) (Mancini et al., Citation2010). Further, national surveys show a majority of the public (∼80%) perceive drunk driving as a major threat to their personal safety, and as such, offer these policies widespread support (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, Citation2010; Stringer, Citation2021a). Drunk driving also represents an offending behavior with causes grounded in pathologies that may not be amenable to punitive deterrence (Bouffard et al., Citation2017; Stringer, Citation2021b), and in which recidivism is perceived to be common and of significant concern (Freiburger & Sheeran, Citation2019; Levenson et al., Citation2014). Simultaneously, ICDDs as a class of individuals does not elicit the same level of disgust or anger as ICSOs (Craun et al., Citation2011). Because a substantial minority of the population engages in driving under the influence (in 2020 1.2% of adults reported driving drunk in the past 30 days [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2022]) an expert expressing leniency toward these individuals may represent a less controversial opinion relative to ICSOs. Thus, we hypothesize:

H1a: Relative to claims regarding ICDDs, respondents will evaluate experts making claims regarding the rehabilitation of ICSOs as less credible.

H1b: Relative to claims about ICDDs, respondents will express lower levels of belief in the experts’ message when it concerns ICSOs.

However, Asplund (Citation2018) observed that Swedish farmers evaluated sources and policy advocacy on climate change as more credible when they believed that advice came from the messenger’s practical experience as opposed to scientific analysis. Further, Beall et al. (Citation2017) found that taking advocacy positions weakened perceived credibility based on whether the respondents viewed the communicator as motivated to persuade the public, as opposed to acting in a position to serve the public. Relevant practitioners in this context would be police officers, who are seen as both having practical knowledge of criminals and occupying a role that serves the public. To this extent, in an ICSO policy context, we hypothesize:

H2a: Compared to the practitioner expert, respondents will evaluate the academic expert as less credible.

H2b: Compared to the practitioner expert, respondents will express lower levels of belief in the academic expert’s claim.

H3: Perceptions of expert credibility will partially mediate the association between the offense type or expert source and the level of belief in their claim.

Finally, on the basis of congruity theory, we should expect that negative evaluations of expert credibility will “stick”, such that experts making unpopular (but empirically sound) claims about ICSO policy may also be viewed as less credible when speaking in other contexts. Specifically, we expect:

H4: Offense type (ICSO vs. ICDD) will partially mediate the association between perceptions of expert credibility and level of belief in a subsequent claim made by the same expert.

The Current Inquiry

Sampling Design

The current study employed a factorial survey experiment conducted with a web-based nationally-matched opt-in panel of US adults from YouGov, commissioned by the Center for Public Opinion at the University of Massachusetts Lowell (Dyck et al., 2018). Relative to unmatched alternatives (e.g. MTurk), matched opt-in panels make specific efforts to reduce potential confounding from selection bias, constructing a sampling frame designed to mimic higher quality probability samples (see Graham et al., Citation2021 or Thompson & Pickett, Citation2020 for additional details on opt-in survey samples). Specifically, YouGov uses a multistage sampling process with propensity score matching and post-stratification weights on gender, age, race, and education (see Ansolabehere & Rivers, Citation2013; Ansolabehere & Schaffner, Citation2014 for additional technical detail on YouGov methods). This combination of matching and weighting produced an analysis sample of 1,000 US adults designed to represent a simple random sample of the target population. The Kish approximation for the survey weight design effect is relatively small at 1.52 (Kish, Citation1965), and all parameter estimates and statistical conclusions were highly similar between weighted and unweighted analyses. All subsequent reported analyses apply the YouGov survey weights.

Although not preferrable to high-quality, national probability samples such as the General Social Survey (GSS), matched opt-in samples have been demonstrated to produce more generalizable results than unmatched opt-in platforms (e.g. MTurk) (Graham et al., Citation2021; Thompson & Pickett, Citation2020). Similar YouGov samples have been used in several recent criminological studies (Novick et al., Citation2022; Socia, Citation2022; Socia et al., Citation2021).

Vignette Protocol and Manipulations

We asked survey participants to consider a short vignette containing testimony attributed to an expert source, randomly assigned to either be a professor of criminology or a police chief. We provided participants with a stock picture of the expert (both middle-aged white males), including credentials such as their title, education/experience, and professional memberships (see the Appendix for full expert source manipulations). The decision to include both a photo and credentials was to standardize the presentation of information, increasing the likelihood that respondents within each expert source condition would have interindividual comparability (Shamon et al., Citation2022). The testimony presented participants with a claim that policies designed to solely enhance punishment severity actually made the targeted individuals more likely to recidivate (e.g. Lowenkamp et al., Citation2010), and instead advocated for enhanced rehabilitation practices. We randomly assigned participants to the offense type that the claim concerned—either “sex offenders” or “drunk drivers.”Footnote1 This manipulation was informed by previous research contrasting ICSOs with ICDDs, based on both being subject to policy campaigns driven by a motivated public (Levenson et al., Citation2014). The rehabilitation claim vignette specifically read:

“In the past 20 years we have learned a lot about effective ways to reduce reoffending among [Offender_Type]. There are programs that only seek to increase the severity of punishments that [Offender_Type] receive for their offenses. But these sorts of ‘get tough’ initiatives aren’t an effective way to reduce reoffending – they actually end up making offenders worse, and more likely to reoffend in the future. Instead of just increasing punishments, the best way to reduce reoffending among [Offender_Type] is to address the root causes of those behaviors, which involves treatment and rehabilitation.”

“A sizable proportion of people in prison are diagnosed with some form of mental illness – larger than you see in the general population – people not in prison, that is. If these conditions go without treatment, they can get worse during incarceration, and could extend to the period after the prisoner is eventually released to the community. However, not all prisons offer mental health treatment. I would recommend that more resources be put towards providing mental health treatment in prison – if a prisoner has some form of mental illness, it should be treated.”

Measures

Manipulations

The vignette conditions are represented with two binary variables, with half of the respondents randomly assigned to each value for each condition. Offense type is coded 0 for “drunk driver” (51.2%) and 1 for “sex offender” (48.8%). Expert source is coded 0 for police chief (50.3%) and 1 for professor (49.7%). The two conditions are fully-crossed, placing roughly one-quarter of the sample into each combination of the expert source and offense type conditions, ranging from 23.5% to 26.2%.

Outcome Variables

Perceived credibility

Following the presentation of the vignette, the respondents were prompted with “[a]fter reading the testimony above, please indicate your impression of the credibility of the person giving the testimony by identifying the appropriate number between the pairs of adjectives below.” The perceived credibility of the expert source was based on the source credibility scale developed by McCroskey and Teven (Citation1999). This scale contains 15 items across three sub-dimensions—competence, trustworthiness, and goodwill. Respectively, these represent the perception that the expert knows what they are talking about, the perception that the expert is honest, and the degree to which the expert is perceived to have the participant’s interests at heart (McCroskey & Teven, Citation1999). Each individual item is a 7-point semantic differential, requesting the participant’s impression of the expert (e.g. unintelligent—intelligent, dishonest—honest). All items and subdimensions are displayed in .

Table 1. Survey Weighted descriptive statistics (N = 990).

Belief in Claims

Following the credibility assessment, the respondents were prompted with “[a]fter reading the testimony above, please indicate the degree to which the statement below represents what you believe by identifying the appropriate number between the pairs of adjectives.” Based on the testimony offered in the vignettes, for the rehabilitation claim the statement was “Instead of increasing punishments, the best way to reduce reoffending among [sex offenders/drunk drivers] is to address the root causes of those behaviors, which involves treatment and rehabilitation.” For the subsequent mental health claim, the statement was “[m]ore resources should be put towards providing mental health treatment in prison.” The degree of the participants’ belief is represented by an adaptation of generalized belief scales (McCroskey & Richmond, Citation1996). These scales use four 7-point semantic differentials (e.g. disagree—agree, false—true) to capture the dimensions of the participants’ belief in each claim.

Analytic Strategy

We utilize structural equation modeling (SEM) to perform our analyses, for two primary reasons. First, our hypotheses concern unobservable traits which we have measured through an array of observed variables (e.g. credibility, belief in a claim). SEM provides a mechanism for connecting these latent constructs to observed data (Merkle et al., Citation2020). Second, several of our hypotheses concern indirect associations between the expert source and offense type, the latent construct of perceived credibility, and subsequent belief in those experts’ claims. SEM provides functionality for statistical inference on these indirect effects (Bollen, Citation1989).

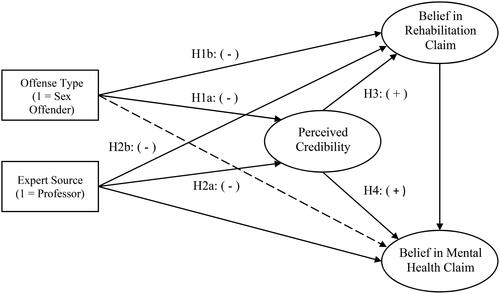

Our proposed structural equation model is presented in .

Figure 1. Proposed structural equation model. Note: Dashed line represents that the vignette topic (sex offender/drunk driver) should only be indirectly associated with belief in the mental health claim, as that vignette does not explicitly concern a specific offender group. Squares represent the experimental manipulations, and the ovals are latent constructs.

Mathematically, the structural regression components of this model can be represented through the following matrix equation (EquationEquation 1(1)

(1) ):

(1)

(1)

Specifically, ,

, and

, represent the latent endogenous variables credibility, belief in the rehabilitation claim, and belief in the mental health claim, respectively. Relevant to Hypotheses 1 and 2, the effect of the experimental manipulations X on these constructs is represented by the matrix of

parameters. The matrix of

parameters describe the structure of associations between the latent constructs. Finally, the

and

parameters are estimates of latent variable intercepts and residuals, respectively (Lin, Citation2022). Relevant to addressing Hypotheses 3 and 4, indirect pathways between observed or latent variables can then be estimated as linear functions of the

and

parameters (Bollen, Citation1989).

Parameter estimates are derived using robust maximum likelihood via the “lavaan” package in R (Rosseel, Citation2012). As there was a non-trivial degree of missingness across respondents (n = 94 [9.4%] missing at least one item) the use of a maximum likelihood estimator further allows full information maximum likelihood (FIML) to be used for unbiased parameter estimates in the presence of data missing at random. Prior to modeling, we removed respondents who were missing more than two items for any given construct (n = 10), producing a final analysis sample of N = 990.

Our analyses initially used confirmatory factor analysis to fit a measurement model for the perceived credibility and generalized belief latent constructs. Goodness of fit was assessed using the robust versions of the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), where values in excess of .95 suggest good model fit (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). We additionally use the robust root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), where values less than .05 and .08 suggest good fit, respectively (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). This analysis supported the use of a second-order factor model, in which latent constructs for competence, goodwill, and trustworthiness were indicated by the observed variables, and these constructs were subsequent indicators of a general perceived credibility latent factor (CFI = .984, TLI = .982, RMSEA = .042, SRMR = .022).

We additionally explored the use of a single factor model, in which credibility is a single latent factor indicated by the McCroskey and Teven (Citation1999) items, as well as a multifactor model which used the competence, goodwill, and trustworthiness subdimensions as separate latent constructs with no subsequent overall credibility construct. The single-order factor was summarily dismissed as an option by this comparison. The multi-factor model produced similar fit to the second-order factor model, and was favored by the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) (62,128 for multi-factor, 62,142 for second-order). We present the second-order factor model here for a number of reasons. The substantive findings were similar between the two sets of models, where the competence and goodwill credibility subdimension had paths to the endogenous variables that were of similar sign, magnitude, and statistical significance. The exception was the trustworthiness subdimension, which was similarly signed but the null hypothesis could not be rejected. Further, the structural equation model using the multi-factor model produced poor fit to the data (CLI = .858, TLI = .836, RMSEA = .118, SRMR = .385).

We then considered measurement invariance of the second-order factor model across the vignette conditions. This is important when the goal of an analysis is to compare latent constructs across groups, as non-invariance would suggest that the construct has a different meaning or structure for each group, precluding the ability to make comparisons (Putnick & Bornstein, Citation2016). Following Widaman and Reise (Citation1997), we test four forms of measurement invariance for our second-order factor model across the four combinations of the expert source and offense type variables; 1) configural invariance, 2) metric or weak invariance, 3) scalar or strong invariance, and 4) strict invariance. Determinations of invariance are made by comparing changes in model fit as invariance assumptions become more stringent. Using the criteria of a −0.01 change in CFI, coupled with respective RMSEA and SRMR changes of .015 and .3 (Chen, Citation2007), we determined our second-order factor model meets criteria for strong/scalar invariance (equal factor loadings and latent variable means), which is the stage necessary for meaningful comparisons of latent factor means across conditions (Putnick & Bornstein, Citation2016).

Results

Structural Equation Model Direct Paths

The results of the SEM are presented in . Fit indices suggest that the model fits the data well (CLI = .984, TLI = .982, RMSEA = .039, SRMR = .022). Parameter estimates are presented as coefficients standardized on the latent variables (std.lv in lavaan). The results suggest the vignette conditions were significantly associated with perceived credibility in the directions hypothesized (1a, 2a). Relative to ICDD, respondents in the ICSO condition evaluated the expert’s credibility as lower by −0.307 standard deviations (95% CI: −0.463, −0.152), and similarly evaluated the academic expert as less credible than the practitioner expert (−0.253 [−0.402, −0.104]). Consistent with hypothesis 1b, respondents expressed less belief in the rehabilitation claim when it concerned ICSOs, although the effect size was small (−0.103 [−0.206, −0.001]). Contrary to hypothesis 2b, respondents did not systematically express less belief in the academic expert’s rehabilitation claim. The point estimate was in the opposite direction (0.088), but could not be distinguished from zero with sufficient certainty (95% CI: −0.003, 0.178).

Table 2. Survey Weighted structural equation model results (N = 990).

Respondents who view experts as more credible expressed greater belief in both the rehabilitation (0.826 [0.779, 0.873]) and mental health claims (0.254 [0.053, 0.454]), and greater belief in the rehabilitation claim was positively associated with belief in the mental health claim (0.546 [0.359, 0.733]). Unexpectedly, compared to ICDD, respondents in the ICSO condition expressed 0.147 standard deviations greater belief in the mental health claim (95% CI: 0.037, 0.256), despite not being directly tied to the offense group from the rehabilitation claim.

As the vignettes followed a 2 × 2 design, we additionally considered the possibility of an interactive effect of the vignette conditions on the latent constructs. Parameter estimates for this model are presented in . In all instances, parameter estimates for the interaction effect could not be distinguished from zero. Comparison of model BICs suggested strong evidence in favor of the main effects model, further suggesting the interaction parameter is unnecessary to capture the impact of the vignette conditions on any latent construct. We move forward with the main effects model for calculation and inference on indirect effects.

Mediation Analyses

Hypotheses 3 and 4 concern mediation, in which the effects of the offense type and expert source conditions on belief in claims will be mediated by perceived credibility. Mediation is established when there is a statistically significant indirect path from the independent variables (vignette conditions) to the mediator (perceived credibility) to the dependent variables (belief in claim) (McLean, Citation2020; Zhao et al., Citation2010). presents indirect and total effects among vignette conditions and latent constructs, computed from the SEM presented in .

Table 3. Structural equation model indirect and total effects (N = 990).

Consistent with hypothesis 3, the results suggest that respondents in the ICSO condition perceive the expert source as less credible, and as a result, ascribe less belief in the rehabilitation claim (−0.254 [−0.384, −0.124]). Similarly, respondents view the academic expert as less credible than the practitioner, subsequently endorsing less belief in their rehabilitation claim (−0.209 [−0.332, −0.086]). However, only the offense type variable produced a statistically significant total effect on belief in the rehabilitation claim, where the ICSO condition reduced belief in the claim by −0.357 standard deviations (95% CI: −0.498, −0.217). These results suggest partial or complementary mediation between offense type, credibility, and belief in the initial rehabilitation claim, and full or indirect-only mediation for the expert source condition (Zhao et al., Citation2010).

Partial support for hypothesis 4 is found. The results suggest that assignment to the ICSO condition reduces perceived credibility, which produces a small decrease in belief in the subsequent (and seemingly unrelated) mental health claim (−0.078 [−0.138, −0.018]). Following the same path, less belief in the rehabilitation claim is estimated to produce less belief in the mental health claim (−0.139 [−0.238, −0.039]). Because of the uncertainty in the total effect for the ICSO condition on the mental health claim (0.069 [−0.054, 0.191]), there is evidence of full or indirect-only mediation (Zhao et al., Citation2010). Concerning the expert source conditions, assignment to the academic expert does not support partial mediation of the association between credibility and belief in the mental health claim (−0.064 [−0.137, 0.008]). However, as respondents viewed the academic expert as less credible, and expressed less belief in the rehabilitation claim made, they subsequently ascribed less belief to the mental health claim (−0.114 [−0.183, −0.045]). The uncertainty in the total effect for the academic expert condition on the mental health claim (−0.107 [−0.228, 0.015]) is evidence of indirect-only mediation.

Discussion

A small body of research has found that a majority of the US public not only supports punitive ICSO policies but are generally unwilling to change their opinions about these policies, even when presented with evidence suggesting their ineffectiveness in improving public safety (Campbell & Newheiser, Citation2019; Rydberg et al., Citation2018; Lachapelle et al., 2014). Relatedly, research on public engagement with science—particularly around politically charged topics like climate change—finds that expert claims that contradict pre-existing beliefs can lead to negative evaluations of that source’s credibility (Vraga et al., Citation2018). These empirical trends suggest troubling possibilities for criminology and criminal justice. Specifically, public-facing experts advocating for evidence-based policies that are less punitive toward stigmatized groups such as ICSOs may find their credibility questioned, thus reducing their ability to influence evidence-based policy reform. The purpose of the present study was to consider such a possibility—whether negative assessments of source credibility are a mechanism for maintaining support for ICSO policies in the face of contradictory empirical evidence. We considered whether these effects would vary based on the source of expertise, and importantly, whether any credibility deficits carry over to subsequent, unrelated claims made by that expert. Based on the results of our factorial survey experiment, three primary conclusions are warranted.

First, we found that respondents viewed an expert as less credible when the expert made claims about ICSOs, compared to similar claims about ICDDs. This effect held for both the academic and practitioner experts. In other words, regardless of whether the statement came from an academic (professor) or a practitioner (police chief) expert, when the claim advocated for less punitive approaches to ICSOs (vs. ICDDs), participants viewed those experts as less credible. This suggests that when faced with a claim that ran counter to popular ‘get tough’ policies for ICSOs, rather than consider the merits of the claim itself, respondents simply discounted the messenger’s credibility.

These findings help explain connections between research that finds the public is particularly punitive towards ICSOs (e.g. Dum et al., Citation2017; Cochran et al., Citation2021; Imhoff & Jahnke, Citation2018), and that these punitive views are especially resistant to change (e.g. Campbell & Newheiser, Citation2019; Rydberg et al., Citation2018). That is, one way that these punitive beliefs can persist and be so resilient to scientific evidence is through discounting the credibility of the source of counter messages. This directly supports prior research on how the public evaluates experts and their credibility when faced with claims that contradict existing beliefs (see Brewer & Ley, Citation2013; Vraga et al., Citation2018).

Second, we observed that expert credibility partially mediated the association between offense type and belief in the expert’s claim, in line with hypothesis 3. Since respondents viewed the experts making claims about ICSOs as less credible, they subsequently expressed less belief in their rehabilitation claim. A similar indirect effect was observed for expert source. An academic expert was viewed as less credible than a practitioner expert and, as a result, respondents were less inclined to believe the claim that they had made.

This has implications for how evidence-based ICSO policies, or other policies involving highly stigmatized populations, might best be presented to the public. For example, earlier findings suggest the public is more receptive to claims concerning general summaries of science, relative to advocating for specific policy approaches (Kotcher et al., Citation2017). Thus, experts making claims about the benefits of rehabilitation may want to start with general statements about its effectiveness, and then follow up with population-specific recommendations that may be more controversial. By first establishing a baseline credibility with the public through non-controversial ‘general’ claims, this might help mitigate the later credibility hit that comes from subsequent claims about more stigmatizing or otherwise controversial issues (such as focusing on rehabilitation over punishment for ICSOs). However, further empirical research is needed to support this suggestion as an effective method to increase (or protect) overall expert credibility with the public, particularly in cases of stigmatized populations.

Further, respondents saw the practitioner as more credible overall than the academic expert, even when they delivered identical messages. One way to overcome the “professor credibility deficit” is for academic researchers to explore strategic collaborations with respected practitioners for messaging purposes. Such a collaboration would provide mutual benefits, as the practitioners would have better access to scientific data, analysis, and evidence-based recommendations, while academic researchers might see their credibility bolstered with the public and, in turn, increase the likelihood of the public believing their scientific recommendations. This might help overcome the problems of penal populist discourse and skepticism of professional experts that have been noted by others (e.g. Garland, Citation2021; Stuntz, Citation2011; Stone & Socia, 2019).

In the same way that policymakers self-label themselves in public statements to identify as a member of the local community (e.g. “As a father…”, “As a Granite Stater…”; see Socia & Brown, Citation2016), researchers may want to consider ways to self-label themselves in interviews and other public-facing media, to help bridge the divide between the public and the (perceived) ivory tower persona. This may be particularly useful for “practademics” in the criminology field, who are academic experts with a prior background in practice (e.g. a professor who was previously a police officer). Future research might investigate whether, and what kind of self-labeling helps increase an expert’s credibility with the public when making scientific claims.

Third, the negative effect on an expert’s perceived credibility from making an empirically valid, but unpopular statement regarding ICSO policies carried over to a subsequent claim on an entirely different issue made by that expert. That is, when the expert advocated for rehabilitation of ICSOs, respondents viewed them as less credible and consequently were less likely to believe their rehabilitation claim. Because they were less likely to believe the rehabilitation claim, participants were also less likely to believe the expert’s subsequent unrelated claim about mental health in prison. As applied to public evaluations of criminologists, this finding is both novel and troubling, but it aligns with more general social psychological research on message-messenger interactions, particularly in marketing applications. Consistent with the expectations of congruity theory (Osgood & Tannenbaum, Citation1955; Tannenbaum & Gengel, Citation1966), when faced with a controversial message from an expert source, attitude change appeared to be transferred to the source, which was then factored into the evaluation of (what should have been) a less controversial message from that source. Prior research in celebrity endorsement has suggested that this direction of meaning transfer—where the endorser’s (messenger) image is impacted by the brand (the message)—is more common when the strength of the brand is more recognizable than that of the messenger (Roy & Moorthi, Citation2012). This seems especially relevant to our current study, where the respondent is expected to have a relatively strong opinion on the message, but likely has little familiarity with the messenger (especially the academic expert).

With regard to effective science communication, the implication here is that claims by a given expert may need to be separated from one another (or reordered) when presented to the public, so that a controversial or otherwise unpopular claim does not indirectly “taint” any subsequent claims or policy recommendations. This is particularly true for those experts who may study controversial or stigmatizing subtopics (e.g. child sexual abuse; drug legalization) within a larger field (e.g. violent crime; harm reduction). For example, when discussing the general mental health needs of incarcerated individuals and what these might imply for policy and practice within prison and jail facilities, care should be taken to avoid referencing other, less popular claims by the expert that are not directly related to the topic at hand (e.g. police defunding, prison abolishment), that may damage their credibility with the public.Footnote2 This also unfortunately provides a strategy for discounting the credibility of an expert and their claims in the media. That is, by first mentioning a controversial or otherwise unpopular claim or recommendation made previously by that same expert, the expert’s current claim can be presented in the negative light cast by the earlier claim.Footnote3

Finally, one potential path forward involves shifting the focus away from presenting scientific claims about ICSOs to the public, and instead, attempting to build positive connections between ICSOs and the public by reducing stigma toward ICSOs. Studies have used art, writing, and video presentations by justice-involved individuals to reduce stigma (Miner-Romanoff, Citation2014; Dum et al., Citation2022), and concerning ICSOs specifically, both written communication and first-person narratives by ICSOs have reduced the stigma applied by the public (Harper & Bartels, Citation2017; Jahnke et al., Citation2015). This strategy, called “narrative humanization” (Harper & Bartels, Citation2017) may offer a more practical way to create contact between ICSOs and the public that portrays ICSOs in a more positive light. Given the focus of the current study, one direction for future research would be to examine how narrative (not scientific) claims about ICSOs from academic and practitioner experts affect public opinion, compared to either first-person narratives by ICSOs, and/or scientific claims about ICSOs from academics and practitioners.

Limitations

These findings should be considered in the context of several limitations. The external validity of the findings is shaped by mode of the treatment—text-based vignettes accompanied by a stock photo meant to represent an expert. Prior research has suggested that more involved modalities, such as live lectures, may be more impactful in changing opinions among skeptical audiences (Webb & Hayhoe, Citation2017). Specifically considering attitudes towards ICSOs, lengthy psychoeducation fliers (Kleban & Jeglic, Citation2012), and semester-length courses (Wurtele, Citation2018) can reduce punitive attitudes towards this group. It is possible that more involved modalities may result in different assessments of source credibility than those observed here (however, the general public may be less likely to engage or encounter these compared to the short messages akin to those in our vignette). We have some confidence that the vignettes were able to communicate some meaningful threshold of information to respondents, given the variation in outcomes observed in this analysis. In retrospect, we would have benefitted from manipulation checks to enhance our confidence in the respondent’s understanding of the vignette materials.

Relatedly, the “sex offender” component of the treatment only took on a single form—literally the words “sex offender” as opposed to “drunk driver”—not explicitly representing heterogeneity in sex offenses and subsequently relying on the respondents to answer based on their own mental images of this construct, which have been found to often align with unrealistic stereotypes (Pickett et al., Citation2013; Socia & Harris, Citation2016). The specific images respondents conjure could be meaningful, as prior research has suggested that the public endorses varying levels of punitivity towards sex offenses based on factors such as the gender of the perpetrator and victim, and the age of the victim (Socia et al., Citation2021). It is possible that experts making similar claims may be met with varying degrees of perceived credibility based on more granular “types” of ICSOs.

Further, the crafting of the expert messenger components of the vignettes may limit the construct and external validity of conclusions drawn. Our choice of presenting a professor and a police chief to represent “academic” or “practitioner” expertise are somewhat arbitrary, in that other configurations of roles may communicate similar information to respondents. Yet, there is little empirical evidence to guide our decision-making in this respect, instead working from subjective priors regarding how the public may perceive particular representations of expertise. We believe that this work provides some baseline empirical evidence for the notion that the public perceived the practitioner expert as more credible than academic expert, at least as it relates to the rehabilitation subject matter in this vignette. Future research may benefit from systematic studies into how the public understands knowledge and expertise in the realm of criminology and criminal justice. One area of inquiry may consider how perceptions of credibility vary over factors such as the race/ethnicity and gender of the messenger. These factors were not designed to vary in the vignettes used in this study, but recent research supports the notion that the public reacts differently (i.e. fear response) based on the combinations of the respondent characteristics and those of the police (e.g. a black respondent and a white police officer) (Pickett et al., Citation2022). Further, in using different photos for each messenger, it’s possible that attractiveness biases may have influenced participants responses (e.g. participants systematically perceiving one expert to be better looking than the other), and the potential impact of any such bias remains unassessed in this analysis.

The sample is also a source of limitation. Online samples have been documented to overrepresent certain segments of the population (e.g. young people, whites, liberals, college educated) (Thompson & Pickett, Citation2020). Although YouGov’s internet-based, matched opt-in panels may be more representative of US adults than unmatched panels, such as those produced by MTurk, this sample cannot claim the same generalizability as a nationally representative probability sample (Graham et al., Citation2021). Further, although online self-administered surveys may lack some of the quality control and oversight that a computer assisted personal interview (CAPI) may afford (Tourangeau & Smith, Citation1996), the use of systematic attention checks through YouGov can limit the impact of some of these concerns.

Conclusion

Prior research has suggested that when it comes to charged issues like how to orient correctional approaches to ICSO populations, not only does the public write off expert opinions (e.g. Campbell & Newheiser, Citation2019; Levenson et al., Citation2007), this research suggests that this translates into the public potentially writing off the experts themselves. As a problem of science communication, in some instances this “public criminology” may be detrimental to the overall goal of advancing evidence-based public policy with contributions from criminological expertise.

Our findings regarding this dilemma present a clear need for additional lines of research into public attitudes towards ICSOs, and receptiveness to criminological science communication. Although a variety of framing mechanisms may be useful in mitigating pre-disposed beliefs on polarized science topics such as climate change or vaccines (Hart & Nisbet, Citation2012; Kotcher et al., Citation2017), additional research is needed to determine if such approaches can be generalized to heavily stigmatized populations such as ICSOs. Empirical attention to the motivated reasoning processes that underly how the public engages with information on ICSO policies may suggest more tailored strategies for effective communication and persuasion. As we witnessed during the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists and policymakers face significant obstacles when trying to advocate for evidence-based policy that produces friction when meeting public opinion. The key is to identify the best ways to persuade the public to accept unpopular, but empirically supported policy recommendations, and the best representatives to present the recommendations in the first place. Our findings therefore provide important insights into what challenges are present and what is required to effectively communicate with the public about contentious criminal justice issues.

Author’s Note

This research was supported by the Center for Public Opinion and the Office of the Dean of Fine Arts, Social Sciences, and Humanities at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. If this paper ever sees the light of day, it is in spite of the “contributions” of the second author.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (139.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 While “sex offender” is a loaded term associated with stereotypes regarding the high risk of reoffending or intractability to treatment, this is the commonly used term within public discourse and thus is practical to employ for the purposes of this study (Harris & Socia, Citation2016).

2 On a related note, research on juror’s perceptions of expert witnesses finds that the way scientific evidence is conveyed can impact expert credibility. That is, jurors saw experts as more credible when they could explain scientific evidence in ways that were accessible and understandable to the lay public (Wilcox & NicDaeid, Citation2018). While we believe the scientific claims contained in our study’s vignettes were written in a clear and accessible manner, the advice to avoid scientific jargon and overly complex explanations is important for scientific experts to keep in mind when conveying their research to the public.

3 The authors humbly request that these findings not be used for evil.

References

- Apel, R. (2013). Sanctions, perceptions, and crime: Implications for criminal deterrence. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 29(1), 67–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-012-9170-1

- Ansolabehere, S., & Rivers, D. (2013). Cooperative survey research. Annual Review of Political Science, 16(1), 307–329. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-022811-160625

- Ansolabehere, S., & Schaffner, B. F. (2014). Does survey mode still matter? Findings from a 2010 multi-mode comparison. Political Analysis, 22(3), 285–303. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpt025

- Asplund, T. (2018). Communicating Climate Science: A Matter of Credibility: Swedish Farmers’ Perceptions of Climate-Change Information. The International Journal of Climate Change: Impacts and Responses, 10(1), 23–38. https://doi.org/10.18848/1835-7156/CGP/v10i01/23-38

- Bauer, M. W., Allum, N., & Miller, S. (2007). What can we learn from 25 years of PUS survey research? Liberating and expanding the agenda. Public Understanding of Science, 16(1), 79–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662506071287

- Beall, L., Myers, T. A., Kotcher, J. E., Vraga, E. K., & Maibach, E. W. (2017). Controversy matters: Impacts of topic and solution controversy on the perceived credibility of a scientist who advocates. PloS One, 12(11), e0187511. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187511

- Blandon-Gitlin, I., Sperry, K., & Leo, R. (2011). Jurors believe interrogation tactics are not likely to elicit false confessions: Will expert witness testimony inform them otherwise? Psychology, Crime & Law, 17(3), 239–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160903113699

- Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. John Wiley & Sons.

- Bouffard, J. A., Niebuhr, N., & Exum, M. L. (2017). Examining specific deterrence effects on DWI among serious offenders. Crime & Delinquency, 63(14), 1923–1945. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128716675359

- Brennan, J. (2020). Can novices trust themselves to choose trustworthy experts? Reasons for (reserved) optimism. Social Epistemology, 34(3), 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2019.1703056

- Brewer, P. R., & Ley, B. L. (2013). Whose science do you believe? Explaining trust in sources of scientific information about the environment. Science Communication, 35(1), 115–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547012441691

- Campbell, D. S., & Newheiser, A. K. (2019). Must the show go on? The (in) ability of counterevidence to change attitudes toward crime control theater policies. Law and Human Behavior, 43(6), 568–584. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000338

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2022). Impaired driving: Get the facts. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. https://www.cdc.gov/transportationsafety/impaired_driving/impaired-drv_factsheet.html

- Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834

- Clifford, S., & Piston, S. (2017). Explaining public support for counterproductive homelessness policy: The role of disgust. Political Behavior, 39(2), 503–525. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-016-9366-4

- Cochran, J. C., Toman, E. L., Shields, R. T., & Mears, D. P. (2021). A uniquely punitive turn? Sex offenders and the persistence of punitive sanctioning. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 58(1), 74–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427820941172

- Craun, S. W., Kernsmith, P. D., & Butler, N. K. (2011). “Anything that can be a danger to the public”: Desire to extend registries beyond sex offenses. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 22(3), 375–391. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403410378734

- DeVault, A., Miller, M. K., & Griffin, T. (2016). Crime control theater: Past, present, and future. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 22(4), 341–348. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000099

- Dum, C. P., Socia, K. M., George, B., & Neiderman, H. M. (2022). The effect of reading prisoner poetry on stigma and public attitudes: Results from a multigroup survey experiment. The Prison Journal, 102(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/00328855211069127

- Dum, C. P., Socia, K. M., & Rydberg, J. (2017). Public support for emergency shelter housing interventions concerning stigmatized populations: Results from a factorial survey. Criminology & Public Policy, 16(3), 835–877. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12311

- Festinger, L. (1964). Conflict, decision, and dissonance. Stanford University Press.

- Freiburger, T. L., & Sheeran, A. M. (2019). Evaluation of safe streets treatment option to reduce recidivism among repeat drunk driving offenders. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 30(9), 1368–1384. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403418789473

- Garland, B., Wodahl, E., & Cota, L. (2016). Measuring public support for prisoner reentry options. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 60(12), 1406–1424. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X15578438

- Garland, D. (2021). What’s wrong with penal populism? Politics, the public, and criminological expertise. Asian Journal of Criminology, 16(3), 257–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-021-09354-3

- Gauchat, G. (2012). Politicization of science in the public sphere: A study of public trust in the United States, 1974 to 2010. American Sociological Review, 77(2), 167–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122412438225

- Graham, A., Pickett, J. T., & Cullen, F. T. (2021). Advantages of matched over unmatched opt-in samples for studying criminal justice attitudes: A research note. Crime & Delinquency, 67(12), 1962–1981. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128720977439

- Gust, D. A., Darling, N., Kennedy, A., & Schwartz, B. (2008). Parents with doubts about vaccines: Which vaccines and reasons why. Pediatrics, 122(4), 718–725. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-0538

- Harper, C. A., & Bartels, R. M. (2017). The influence of implicit theories and offender characteristics on judgements of sexual offenders: A moderated mediation analysis. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 23(2), 139–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600.2016.1250963

- Harris, A. J., & Socia, K. M. (2016). What’s in a name? Evaluating the effects of the “sex offender” label on public opinions and beliefs. Sexual Abuse : A Journal of Research and Treatment, 28(7), 660–678. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063214564391

- Hart, P. S., & Nisbet, E. C. (2012). Boomerang effects in science communication: How motivated reasoning and identity cues amplify opinion polarization about climate mitigation policies. Communication Research, 39(6), 701–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650211416646

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Huebner, B. M., Kras, K. R., Rydberg, J., Bynum, T. S., Grommon, E., & Pleggenkuhle, B. (2014). The effect and implications of sex offender residence restrictions: Evidence from a two-state evaluation. Criminology & Public Policy, 13(1), 139–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12066

- Imhoff, R., & Jahnke, S. (2018). Punitive attitudes against pedophiles or persons with sexual interest in children: Does the label matter? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(2), 353–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0439-3

- Inglis, M., & Mejia-Ramos, J. P. (2009). The effect of authority on the persuasiveness of mathematical arguments. Cognition and Instruction, 27(1), 25–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370000802584513

- Jahnke, S., Schmidt, A. F., Geradt, M., & Hoyer, J. (2015). Stigma-related stress and its correlates among men with pedophilic sexual interests. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(8), 2173–2187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0503-7

- Kennedy-Hendricks, A., Barry, C. L., Gollust, S. E., Ensminger, M. E., Chisolm, M. S., & McGinty, E. E. (2017). Social stigma toward persons with prescription opioid use disorder: associations with public support for punitive and public health–oriented policies. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 68(5), 462–469. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201600056

- Kish, L. (1965). Survey sampling (1st ed). John Wiley & Sons.

- Kleban, H., & Jeglic, E. (2012). Dispelling the myths: Can psychoeducation change public attitudes towards sex offenders? Journal of Sexual Aggression, 18(2), 179–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600.2011.552795

- Koon-Magnin, S. (2015). Perceptions of and support for sex offender policies: Testing Levenson, Brannon, Fortney, and Baker’s findings. Journal of Criminal Justice, 43(1), 80–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2014.12.007

- Kotcher, J. E., Myers, T. A., Vraga, E. K., Stenhouse, N., & Maibach, E. W. (2017). Does engagement in advocacy hurt the credibility of scientists? Results from a randomized national survey experiment. Environmental Communication, 11(3), 415–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2016.1275736

- Krauss, D. A., Cook, G. I., Umanath, S., & Song, E. (2022). Changing the public’s crime control theater attitudes. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 28(4), 595–615. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000340

- Kvaløy, B., Finseraas, H., & Listhaug, O. (2012). The publics’ concern for global warming: A cross-national study of 47 countries. Journal of Peace Research, 49(1), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343311425841

- Lachapelle, E., Montpetit, É., & Gauvin, J. P. (2014). Public perceptions of expert credibility on policy issues: The role of expert framing and political worldviews. Policy Studies Journal, 42(4), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12073

- Levenson, J. S., Brannon, Y. N., Fortney, T., & Baker, J. (2007). Public perceptions about sex offenders and community protection policies. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 19(4), 369–379. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-2415.2007.00119.x

- Levenson, J. S., Shields, R. T., & Singleton, D. A. (2014). Collateral punishments and sentencing policy: Perceptions of residence restrictions for sex offenders and drunk drivers. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 25(2), 135–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403412462385

- Lin, J. (2022). Introduction to structural equation modeling (SEM) in R with lavaan. UCLA Advanced Research Computing. https://stats.oarc.ucla.edu/r/seminars/rsem/

- Lowenkamp, C. T., Flores, A. W., Holsinger, A. M., Makarios, M. D., & Latessa, E. J. (2010). Intensive supervision programs: Does program philosophy and the principles of effective intervention matter? Journal of Criminal Justice, 38(4), 368–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2010.04.004

- Mancini, C., Shields, R. T., Mears, D. P., & Beaver, K. M. (2010). Sex offender residence restriction laws: Parental perceptions and public policy. Journal of Criminal Justice, 38(5), 1022–1030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2010.07.004

- McCracken, G. (1989). Who is the celebrity endorser? Cultural foundations of the endorsement process. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(3), 310–321. https://doi.org/10.1086/209217

- McCroskey, J. C., & Richmond, V. P. (1996). Fundamentals of human communication. Prospect Heights, IL.

- McCroskey, J. C., & Teven, J. J. (1999). Goodwill: A reexamination of the construct and its measurement. Communication Monographs, 66(1), 90–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637759909376464

- McLean, K. (2020). Revisiting the role of distributive justice in Tyler’s legitimacy theory. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 16(2), 335–346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-019-09370-5

- Merkle, E. C., Fitzsimmons, E., Uanhoro, J., & Goodrich, B. (2020). Efficient Bayesian structural equation modeling in Stan. arXiv preprint arXiv:2008.07733.

- Mears, D. P., Mancini, C., Gertz, M., & Bratton, J. (2008). Sex crimes, children, and pornography: Public views and public policy. Crime & Delinquency, 54(4), 532–559. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128707308160

- Metzger, M. J., & Flanagin, A. J. (2013). Credibility and trust of information in online environments: The use of cognitive heuristics. Journal of Pragmatics, 59, 210–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2013.07.012

- Miner-Romanoff, K. (2014). Student perceptions of juvenile offender accounts in criminal justice education. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 39(3), 611–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-013-9223-5

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. (2010). National survey of drinking and driving attitudes and behaviors. U.S. Department of Transportation.

- Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology, 2(2), 175–220. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.2.175

- Novick, R., Socia, K. M., & Pickett, J. T. (2022). Asymmetric Compassion Collapse, Collateral Consequences, and Reintegration: An Experimental Study. Justice Quarterly, 39(7), 1475–1498. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2022.2119157

- Osgood, C. E., & Tannenbaum, P. H. (1955). The principle of congruity in the prediction of attitude change. Psychological Review, 62(1), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0048153

- Pickett, J. T., Graham, A., Nix, J., & Cullen, F. T. (2022). Officer Diversity Reduces Black Americans’ Fear of the Police. CrimRxiv. https://doi.org/10.21428/cb6ab371.f07bcfc5

- Pickett, J. T., Mancini, C., & Mears, D. P. (2013). Vulnerable victims, monstrous offenders, and unmanageable risk: Explaining public opinion on the social control of sex crime. Criminology, 51(3), 729–759. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9125.12018

- Putnick, D. L., & Bornstein, M. H. (2016). Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: The state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Developmental Review : DR, 41, 71–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2016.06.004

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

- Roy, S., & Moorthi, Y. L. R. (2012). Investigating endorser personality effects on brand personality: Causation and reverse causation in India. Journal of Brand Strategy, 1(2), 164–179.

- Rutjens, B. T., Sutton, R. M., & van der Lee, R. (2018). Not all skepticism is equal: Exploring the ideological antecedents of science acceptance and rejection. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(3), 384–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167217741314

- Rutjens, B. T., van der Linden, S., & van der Lee, R. (2021). Science skepticism in times of COVID-19. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 24(2), 276–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430220981415

- Rydberg, J., Dum, C. P., & Socia, K. M. (2018). Nobody gives a#% &!: A factorial survey examining the effect of criminological evidence on opposition to sex offender residence restrictions. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 14(4), 541–550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-018-9335-5

- Sample, L. L., Evans, M. K., & Anderson, A. L. (2011). Sex offender community notification laws: Are their effects symbolic or instrumental in nature? Criminal Justice Policy Review, 22(1), 27–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403410373698

- Schiavone, S. K., & Jeglic, E. L. (2009). Public perception of sex offender social policies and the impact on sex offenders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 53(6), 679–695. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X08323454

- Schmechel, R. S., O’Toole, T. P., Easterly, C., & Loftus, E. F. (2005). Beyond the ken-Testing jurors’ understanding of eyewitness reliability evidence. Jurimetrics, 46, 177.

- Shamon, H., Dülmer, H., & Giza, A. (2022). The factorial survey: The impact of the presentation format of vignettes on answer behavior and processing time. Sociological Methods & Research, 51(1), 396–438. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124119852382

- Socia, K. M. (2022). Driving public support: Support for a law is higher when the law is named after a victim. Justice Quarterly, 39(7), 1449–1474. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2022.2064329

- Socia, K. M., & Brown, E. K. (2016). “This isn’t about Casey Anthony anymore” political rhetoric and Caylee’s law. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 27(4), 348–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403414551000

- Socia, K. M., & Harris, A. J. (2016). Evaluating public perceptions of the risk presented by registered sex offenders: Evidence of crime control theater? Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 22(4), 375–385. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000081

- Socia, K. M., Rydberg, J., & Dum, C. P. (2021). Punitive attitudes toward individuals convicted of sex offenses: A vignette study. Justice Quarterly, 38(6), 1262–1289. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2019.1683218

- Stone, R., & Socia, K. M. (2019). Boy with toy or black male with gun: An analysis of online news articles covering the shooting of Tamir Rice. Race and Justice, 9(3), 330–358. https://doi.org/10.1177/2153368716689594

- Stringer, R. J. (2021a). Drunk driving and deterrence: Exploring the reconceptualized deterrence hypothesis and self-reported drunk driving. Journal of Crime and Justice, 44(3), 316–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/0735648X.2020.1795903

- Stringer, R. J. (2021). Deterring the drunk driver: An examination of conditional deterrence and self-reported drunk driving. Crime & Delinquency, https://doi.org/10.1177/00111287211054721

- Stuntz, W. (2011). The collapse of American criminal justice. Harvard University Press.

- Tannenbaum, P. H., & Gengel, R. W. (1966). Generalization of attitude change through congruity principle relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3(3), 299–304. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0023030

- Tewksbury, R., Mustaine, E. E., & Payne, B. K. (2011). Community corrections professionals’ views of sex offenders, sex offender registration and community notification and residency restrictions. Federal Probation, 75, 45–50.

- Thompson, A. J., & Pickett, J. T. (2020). Are relational inferences from crowdsourced and opt-in samples generalizable? Comparing criminal justice attitudes in the GSS and five online samples. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 36(4), 907–932. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-019-09436-7

- Tourangeau, R., & Smith, T. W. (1996). Asking sensitive questions: The impact of data collection mode, question format, and question context. Public Opinion Quarterly, 60(2), 275–304. https://doi.org/10.1086/297751

- Tyler, T. R. (2006). Psychological perspectives on legitimacy and legitimation. Annual Review of Psychology, 57(1), 375–400. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190038

- Uggen, C., & Inderbitzin, M. (2010). Public criminologies. Criminology & Public Policy, 9(4), 725–749. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9133.2010.00666.x

- Vraga, E., Myers, T., Kotcher, J., Beall, L., & Maibach, E. (2018). Scientific risk communication about controversial issues influences public perceptions of scientists’ political orientations and credibility. Royal Society Open Science, 5(2), 170505. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.170505

- Webb, B. S., & Hayhoe, D. (2017). Assessing the influence of an educational presentation on climate change beliefs at an Evangelical Christian College. Journal of Geoscience Education, 65(3), 272–282. https://doi.org/10.5408/16-220.1

- Welch, M., Fenwick, M., & Roberts, M. (1998). State managers, intellectuals, and the media: A content analysis of ideology in experts’ quotes in feature newspaper articles on crime. Justice Quarterly, 15(2), 219–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418829800093721

- Widaman, K. F., & Reise, S. P. (1997). Exploring the measurement invariance of psychological instruments: Applications in the substance use domain. In K. J. Bryant, M. Windle, & S. G. West (Eds.), The science of prevention: Methodological advances from alcohol and substance abuse research (pp. 281–324). American Psychological Association.

- Wilcox, A. M., & NicDaeid, N. (2018). Jurors’ perceptions of forensic science expert witnesses: Experience, qualifications, testimony style and credibility. Forensic Science International, 291, 100–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2018.07.030

- Wurtele, S. K. (2018). University students’ perceptions of child sexual offenders: Impact of classroom instruction. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 27(3), 276–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2018.1435598

- Zhao, X., Lynch, J. G., Jr,., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 197–206. https://doi.org/10.1086/651257

Appendix

Table A1. Vignette conditions.