ABSTRACT

The objective of the study is to explore the possibilities of pedagogical translanguaging as a strategy to develop critical language awareness among a group of primary school students from the Basque Autonomous Community (Spain). The study is part of a broader ethnographically based research project, which was developed over two school years in Basque, Spanish and English language subjects. Participants were 51 primary school students studying through the medium of the minority language Basque in an area where the dominant language in society is Spanish, in addition, these students were learning English as a foreign language. The findings show how students’ critical language awareness is developed when sociolinguistically informed didactic strategies are integrated together with translanguaging pedagogies in the classroom. As a result of translanguaging pedagogies and the sociolinguistic reflection carried out during the intervention, the students built up their awareness of minority languages and affective attitudes towards their own. In turn, the simultaneous use of several languages in the classroom brought to the surface the unbalanced power relation among Basque, Spanish and English. This study’s findings reinforce the need for creating and maintaining spaces for minority languages to breathe within the framework of translanguaging pedagogies.

Introduction

In this article, we present findings from qualitative research carried out in a trilingual school in the Basque Autonomous Community (BAC), in Spain. The aim of the project was the fluid and strategic use of the entire linguistic repertoire of bilingual children, taking into account the cultural and linguistic backgrounds of all students in the school. In the development of multilingual pedagogies, García et al. (Citation2012) focused on two aspects: social justice and social practices. It is necessary to look at social justice because the speakers are placed at different levels among other people. Similarly, in the classrooms, teachers need to create opportunities to participate for all constituting thus, a democratic classroom. In addition, the teacher has to aid students when building knowledge through social practice (Vygotsky, Citation1978). That social practice occurs through the trust built between the teacher and the students. The teacher guides the students across the language, comparing different linguistic elements, looking for similarities and differences. This practice within the classroom is what Canagarajah (Citation2011) calls translanguaging strategies. In our view, teaching through translanguaging strategies in the classroom is more than merely an intuitive translanguaging practice (Cenoz & Gorter, Citation2021). In the current study, on the one hand, we explore the potential of a project based on pedagogical translanguaging to boost critical language awareness among a group of primary education students in the Basque Autonomous Community. Research on the development of critical language awareness at school in a regional minority language context is scarce. In addition, due to the weak situation of the Basque language, the introduction of translanguaging in education is causing concern among certain local academics and practitioners. Even Cenoz and Gorter (Citation2017), who support the introduction of translanguaging in mainstream education, have advocated for sustainable translanguaging providing breathing spaces for the minority language. This study aims to shed some light on the influence of pedagogical translanguaging on students’ attitudes. In particular, we investigate how these students’ language perceptions and their status are altered when embodying fluid language practices in the classroom.

Pedagogical translanguaging as a tool to increase language awareness

Research in language awareness is a complex field that draws insights from cognitive linguistics and psycholinguistics (Bialystok, Citation2001). It is closely linked to studies on second language acquisition and multilingualism (Hofer & Jessner, Citation2019; Leonet et al., Citation2020) and has embraced diverse epistemologies, methodologies, and research (Garrett & Cots, Citation2018; Hélot et al., Citation2018). The concept of language awareness has prompted discussions among scholars regarding its various subcategories, dimensions, and levels, with scholars often focusing on specific dimensions such as metalinguistic awareness, which is primarily a cognitive construct (Bialystok, Citation1991, Citation2001; Jessner, Citation1999), or critical language awareness, which emphasises power dynamics (Clark & Ivanic, Citation1997; Hélot & Young, Citation2006). While this study is part of a larger research project aimed at developing students’ multilingual competence, it focuses on students’ critical language awareness, which is understood as the ability to examine ‘how ideologies, politics, and social hierarchies are embodied, reproduced and naturalised through language’ (Leeman & Serafini, Citation2016, p. 12).

Moreover, the concept of language awareness offers an opportunity to involve all students in language-teaching activities at school (Hélot et al., Citation2018). In the European context, some projects that embrace the notion of language awareness have been developed, such as FREPA/CARAP (Candelier et al., Citation2012), or the ‘Guide for the development and implementation of curricula for plurilingual and intercultural education’ (Beacco et al., Citation2016). The pluralistic approach in Europe has been criticised (García & Otheguy, Citation2020) because it aligns with the communicative practices of the neoliberal economy and considers only languages of European nation-states and officially acknowledged linguistic minorities (such as Basque in Spain, Frisian in the Netherlands, Welsh or Gaelic in the United Kingdom) but no other languages spoken by people who actually live in Europe. Some studies suggest that integrating immigrant languages into classrooms provides a better chance of inclusive educational success for all students (Carbonara & Scibetta, Citation2022; Duarte & Günther-van der Meij, Citation2018; Little & Kirwan, Citation2018; Moodley, Citation2007).

In this vein, Wilson and Pascual y Cabo (Citation2019) have advocated for sociolinguistically informed approaches to language teaching that focus on the acknowledgement of language diversity to address their linguistic needs, validate their experiences and create spaces to address their socio-affective needs. Moreover, sociolinguistically informed approaches also focus on the development of critical language awareness (e.g. Beaudrie et al., Citation2021; Holguín Mendoza, Citation2018; Leeman, Citation2018; Leeman & Serafini, Citation2016). For instance, Duran Urrea et al. investigated the effects of a curriculum designed to cultivate Critical Language Awareness among students in two advanced Spanish grammar courses and a Master’s course in Hispanic Linguistics at a public institution in the northeastern United States. The research focused on Latinx students, predominantly from the Dominican Republic, with limited exposure to US education. Quantitative analysis showed significant improvements in critical language awareness across various domains, including language variation, linguistic diversity, language ideologies, Spanish usage in the US, bilingualism, and translanguaging. Additionally, qualitative findings indicated that students initially struggled with linguistic insecurities and questioned their own grammatical knowledge. However, upon completing the course, they transitioned from feeling deficient in grammar to understanding linguistic structures, recognising the socio-political dimensions of language, and gaining empowerment as future language educators. In turn, Gorter et al. (Citation2021) investigated the potential of linguistic landscapes to cultivate language awareness in the multilingual education of the Basque Country. The study drew from data collected in public spaces as well as from primary school students and master’s degree students at university. The authors highlighted the significance of languages present in public spaces as a vital resource for language learning and instruction, while also serving to heighten language awareness among learners.

Translanguaging is probably the most disseminated approach (García & Wei, Citation2014) to enhance language awareness. The term originated in the 1980s in Wales to refer to a pedagogical practice in which students shifted the input and output languages (Welsh and English in their case) for learning purposes (Williams, Citation1994). The term has since rapidly grown in popularity and research on translanguaging as pedagogies and students’ flexible languaging has extended all over the world (Canagarajah, Citation2011; Cenoz & Gorter, Citation2021; García & Wei, Citation2014). Nowadays, as pointed out by Leung and Valdés (Citation2019), ‘translanguaging is a multifaceted and a multi-layered polysemic term’ (p. 365).

Much of the work on translanguaging pedagogies initially occurred with Latinx students in the United States in Spanish-English bilingual education programmes (e.g. Anderson & Lightfoot, Citation2018; Creese & Blackledge, Citation2010; García & Alonso, Citation2021; García & Kleyn, Citation2016; García & Lin, Citation2016; García & Wei, Citation2014). Nowadays, that work continues to influence critical scholars seeking to break away from static language constructs (e.g. Blommaert, Citation2010; Makoni & Pennycook, Citation2005; Otheguy et al., Citation2015).

However, for minoritised language communities such as Basque, with around one million speakers, this opposition towards named languages and fixed language categories arises controversy and is seen with fear by individuals and social agents working in its maintenance and revitalisation (Cenoz & Gorter, Citation2017). Even scholars aligned with the notion of the unitary linguistic repertoire ‘still recognises the material effects of socially constructed named language categories and structuralist language ideologies, especially for minoritised language speakers’ (Vogel & Garcia, Citation2017, p. 4). Taking as an example the Basque context, Cenoz and Gorter (Citation2017) warn of the potential risks translanguaging may provoke when minoritised languages are part of the curriculum and they advocate for sustainable translanguaging practices. Translanguaging practices in such contexts might be consciously planned and designed according to the social context and the school’s features (Leonet et al., Citation2017).

In the current article, we focus on the pedagogical use of translanguaging, following the original use of the term in Wales and go a step further to explore new practices that enhance language awareness in an educational context where a minority language coexists with two strong languages in school. Students were involved in activities to enhance both metalinguistic awareness across the languages of the curriculum (Basque, Spanish and English) and critical language awareness towards language diversity and ideologies. We adopt the view proposed by Cenoz and Gorter (Citation2017; Citation2021) to whom pedagogical translanguaging embraces pedagogical practices that are previously planned by the teacher/researcher and can refer to the use of different languages for input and output or to other strategies based on the use of the students’ entire linguistic repertoire Cenoz and Gorter (Citation2021). For example, when there are activities including input in one language and output in another, the former is usually done using the students’ L1 and the output in the students’ L2 or additional language. For example, the teacher can decide to activate the students’ prior knowledge through a discussion of the topic in the students’ L1 and present the content afterwards in the target language. Therefore, the L1 is used for scaffolding as proposed by Cenoz and Gorter (Citation2021) for building new knowledge on existing cognitive structures. This way pedagogical translanguaging activates and expands existing conceptual and linguistic knowledge encoded in their L1. These kinds of pedagogical practices facilitates organising and mediating mental processes such as the assimilation and accommodation of information and choosing and selecting from the brain storage systems to accomplish communicative tasks (Leonet & Saragueta, Citation2023). Other types of translanguaging activities could include systematic work on the development of metalinguistic awareness. Activities where the students can compare the morphological aspects among the languages in their repertoire, allow them to be aware of word formation for example and can help them understand more complex texts reinforcing the learning of languages as well as content (Leonet & Orcasitas-Vicandi, Citation2022). In addition, the recognition and identification of cognates helps the bilingual or multilingual student infer the meaning of other words in the target language and thus, extend the knowledge of vocabulary (Leonet & Saragueta, Citation2023). Therefore, it is helpful to allow students use the resources they have in their multilingual repertoire as a foundation when learning an additional language because that enhances their competence in that later language (Cenoz & Arocena, Citation2018).

Raising awareness of minority languages through pedagogical translanguaging

The Basque Autonomous Community (BAC) is a multilingual region in Spain with a population of over 2 million inhabitants. In this province, the dominant language Spanish and the regional minority language Basque are co-official languages. According to The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, regional or minority languages are

languages traditionally used within a given territory of a state by nationals of that state who form a group numerically smaller than the rest of the state’s population; they are different from the official language(s) of that state, and they include neither dialects of the official language(s) of the state nor the languages of migrants. (Council of Europe, Citation1992, p. 2)

Traditionally, speakers of regional minority languages have had a strong feeling of protection towards their language in order to protect it from the majority languages (Baker, Citation1992; Lasagabaster, Citation2005). However, today ‘multilingualism is immersed in globalization, technologization and mobility’ (Douglas Fir Group, Citation2016, p. 20) and therefore the attitudes and linguistic practices of younger people are changing. Young people seem to value higher English than any other European language because they perceive it as a major international communication tool that plays an important role in their future (Busse, Citation2017). In the Basque Country, Martínez de Luna (Citation2018) warns that the attractiveness of English can have a negative impact on the minority language and its revitalisation process, and underscores the need for strategies to preserve and revitalise the language beyond mere isolation. He also affirms that in the current globalised world, English has given way to the paradigm of multilingualism against the predominance of monolingualism. Thus, the strategy of language isolation to protect minority languages, Basque in this case, is increasingly being called into question (Cenoz & Gorter, Citation2017; Leonet & Orcasitas-Vicandi, Citation2022).

Raising awareness of language status differences among the students can be worked on in schools. While developing the students’ multilingual competence (Canagarajah & Liyanage, Citation2012; Council of Europe, Citation2001), in addition to the linguistic aspects, the students can gain sociolinguistic knowledge about the difference in the status of the languages coexisting in the territory and the individual, linguistic and social effects derived from these differences. This knowledge can be developed in schools (Leonet et al., Citation2017). In a research project carried out in the Basque Autonomous Community to develop students’ communicative competence in Basque, Spanish and English, Leonet et al. (Citation2017) reported the opinions of the teachers who participated in the pedagogical intervention based on translanguaging pedagogies. According to those teachers, working with three languages simultaneously may contribute to developing metalinguistic awareness, but at the same time, they felt that Basque should be reinforced more than the other languages (see also, Cenoz & Gorter, Citation2017). Those teachers valued positively the critical language awareness activities about Basque and other minority languages because they thought those activities raised awareness regarding the status of languages among the students. Another aspect that they underlined was that working with Basque, Spanish and English together in the pedagogical project had contributed to increasing the prestige of the minority language Basque. That was because Basque had been placed at the same level as the dominant language Spanish and the foreign language English. Leonet et al. (Citation2017) concluded that translanguaging pedagogies can be compatible with the maintenance and revitalisation of minority languages but an appropriate didactic intervention should be tailored to the school’s social context, to its aims regarding multilingual competences and to the students’ language profile. The authors also advocated for sustainable translanguaging pedagogies ‘not only by allowing spaces for the minority languages but also by giving full support to the minority language when using translanguaging pedagogies so as to compensate for its relatively weaker sociolinguistic situation’ (p. 225). However, the authors also alerted about the monolingual ideologies in schools (see, Arocena Egaña et al., Citation2015) that could prevent the use of translanguaging pedagogies and suggested adapting them to the school’s pedagogies by introducing them gradually and evaluating the outcomes.

In the case of migrant minority languages, translanguaging has been described as a pedagogy to provide voice to minoritised children by legitimising their fluid use of the whole linguistic repertoire in the classroom and encouraging parents to be a part of their children’s education (Carbonara & Scibetta, Citation2022; Creese & Blackledge, Citation2010; Little & Kirwan, Citation2018). Carbonara and Scibetta (Citation2022) reported a transformative action-research project based on translanguaging pedagogy at a curricular level. They found that immigrant minority languages had started to be conceived by students as educational resources for learning and meaning-making and that these pedagogies rise to empowerment dynamics and legitimate more flexible multilingual practices. Little and Kirwan (Citation2018) declared that translanguaging pedagogies empower pupils from migrant backgrounds and create emotional bonds among students.

In this paper, we adopt a sociolinguistically informed approach that focuses on the recognition of language diversity and actively engages students in questioning dominant language ideologies. The term language awareness is used as an umbrella term to refer to students’ metalinguistic activity and the cultivation of intercultural and sociolinguistic understanding within the surrounding context (Cenoz & Arocena, Citation2018; Prada & Nikula, Citation2018). Previous studies in the BAC have explored the potential of pedagogical translanguaging to enhance students’ metalinguistic awareness across languages (Leonet & Saragueta, Citation2023, Leonet et al., Citation2020). Alternatively, the present study explores the potential of pedagogical translanguaging to enhance students’ critical language awareness towards the minoritised nature of Basque and language diversity including other minority languages in mainstream classroom interaction. The following research questions guide the study:

To what extent can pedagogical translanguaging develop students’ language awareness?

In what ways has translanguaging pedagogy in class altered students’ perception of languages and their status?

Method

The context of the study

This study was part of a larger project that aimed at developing students’ communicative competence in the three languages of school and increasing their language and metalinguistic awareness (see, Leonet & Saragueta, Citation2023). Regarding anonymity and confidentiality, the project adhered to the procedures and guidelines set forth by the Ethics Committee of the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU). Approval for this project was granted with the identification code: M10/2020/212. The project was carried out in a public school of the BAC where the minority language Basque is the main language of instruction. The project included two didactic units per each of the language subjects (Basque, Spanish and English) consisting of planned and sequenced activities based on pedagogical translanguaging where more than one language was used for specific purposes. The students compared languages in their repertoire and reflected upon the surrounding sociolinguistic context in order to develop language awareness as well as increase knowledge in the three languages.

Participants

Participants were 51 (age = 10.1) students in the 5th grade of primary education, 56.7% female and 43.3% male. They had Spanish (46.7%), Basque (23.3%) or both (26.7%) as their mother tongue and one student (3.3%) had other language (Tamazight) as well. Students had more exposition to academic content in Basque, as it is the main language of instruction in this school. Yet, Spanish is the dominant language in their surrounding sociolinguistic area. Students reported that they use mainly Basque (13.3%), Spanish (3.3%), both Spanish and Basque (83.3%) with their friends in the school; and Spanish (43.3%) or both Basque and Spanish (56.7%) with their friends outside the school. The competence in the English language is substantially lower as it is a foreign language with little presence in students’ daily life. Yet, 60% of the students attend English lessons in private academies.

Fieldwork

The data presented in the following sections was obtained throughout two academic years, from September to June each time. Each year, students worked with the translanguaging materials for 12 weeks, 40–50% of the time in the Basque, Spanish and English language classes. Before the intervention, the researcher spent four weeks immersed in the school environment and observing the pupils. This was followed by another four weeks after the intervention. During the intervention, intensive fieldwork was carried out in one of the three classes in which the pedagogical intervention was conducted over the two years. The fieldwork was developed in four stages and the techniques used for data collection differed at each stage:

First stage. First contact was made with the school during the first year of the project. The school was chosen because of its sociolinguistic situation. At this stage, meetings and interviews were conducted with the principal and some teachers. Classroom observations were also conducted so as to see how the teachers and students work in class. The translanguaging materials were created taking into account schools' curricula and teaching methodology.

Second stage. From February to June, intensive participant observation was carried out. Following Duranti (Citation2000), a non-structured observation was conducted, the students were investigated in their own natural environment. The researcher (second author) observed the students in the classroom and took notes in a notebook. Yet she also had an audio recorder (see Duranti, Citation2000). The recorded data during the intervention was immediately transcribed and codified together with the ethnographers’ diary. The observation carried out in several sessions, was participatory because the researcher was actively involved in the action they were taking part. At the beginning of the research, the researcher explained to the students that she was interested in languages and culture and that she was doing research on it (Jones et al., Citation2000). As the research progressed, when asked by the students, the researcher explained the scope of the research to the students in a broad manner.

Additionally, focus group discussions were conducted with all students during this period (see, Leonet & Saragueta, Citation2023). Students were asked about their experience working with more than one language together. Although the researcher used Basque to guide the discussion, the students were allowed to use any language of their entire repertoire. The focus groups were particularly enriching to this analysis as students were able to reflect on their own experience during the intervention and, therefore, to enhance awareness of their multilingualism. All focus group discussions were audio-recorded gathering a corpus of 290 minutes. Five main themes emerged from the data analyses, of which only one related to language awareness was selected for the purposes of the present article. Axial themes and subthemes comprised the different kinds of language awareness attitudes that had been observed and narrated.

Stage three. During the second year of the project, the second intervention was carried out again during the months of February to June. The same students who participated in the intervention the previous year were observed. At that time, they were in the sixth grade of primary education. As before, intensive participant observation was carried out by the second author of the article, and the recorded data was transcribed and codified together with ethnographers’ diary.

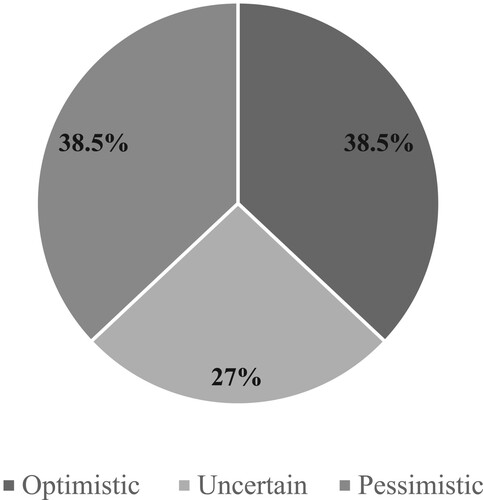

Fourth stage. During the following months, a translanguaging exercise completed by students was used to analyse students’ beliefs about the future of Basque. The exercise consisted of a reading comprehension text analysing the situation of Basque in comparison with other languages followed by four multiple-choice questions to measure the comprehension of the content and an open question: What do you think the situation of Basque will be in the future? This exercise was the starting point for the later Quiz Show activity. The students’ responses were analysed and classified into optimistic future, pessimistic future and uncertain future.

Data analysis

The specific data for the current study was collected as part of a larger project over two academic years. Data was collected through classroom observations, focus group discussions and material analysis. Analysis was carried out using NVivo software for qualitative data analysis. All data was transcribed and converted to PDF for coding in order to identify patterns, themes and significant relationships within the data. The first and second authors of the article rigorously defined the coding framework to ensure validity and reliability. They facilitated a reflective consensus process by independently coding the data, continuously comparing the coding, and resolving any discrepancies through discussion (Onwuegbuzie & Leech, Citation2007; Selvi, Citation2019).

A qualitative content analysis (Selvi, Citation2019) was carried out by triangulating the data from the observations and the focus group discussion. The data analysis was carried out in different steps according to the data collection process. First, the data from the first year of observations were analysed. The audio recordings were transcribed immediately and the researcher’s notes were entered into a field diary after each session. The analysis of the data derived from the observations was not limited to pre-established fixed categories. The data was organised into open codes that resulted in axial categories in terms of language perception and language awareness. As for the data derived from the focus group discussion, both deductive and inductive analytical approaches were used to establish categories. Five main categories emerged from the data analysis (see Leonet & Saragueta, Citation2023), of which only the category labelled language awareness and its related axial categories and subcategories were selected for the specific purpose of the current study. For the analysis of the second year of observation, an open coding categorisation was carried out again, following the axial categorisation, in order to identify new potential categories. The process was completed with selective coding where all categories were linked. Finally, data from the translanguaging exercise about the future of Basque was also transcribed and classified according to the previously stablished categories: optimistic attitude, pessimistic attitude and uncertain attitude. Data were quantified and descriptive statistics were calculated.

Findings

Pedagogical translanguaging as a tool to develop students’ critical language awareness

The data to answer the question To what extent can pedagogical translanguaging develop students’ language awareness? was collected on the one hand through a focus group discussion held during the first year of the two-year long project and through observations of the lessons. The project consisted of a pedagogical intervention that aimed to develop students’ multilingual competence and language awareness.

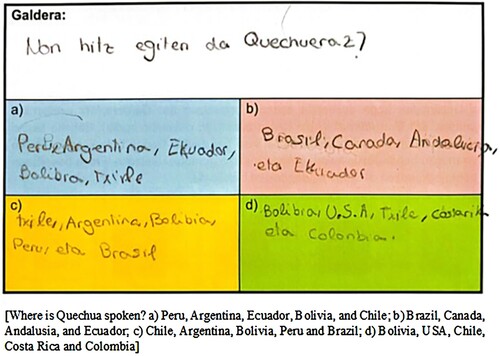

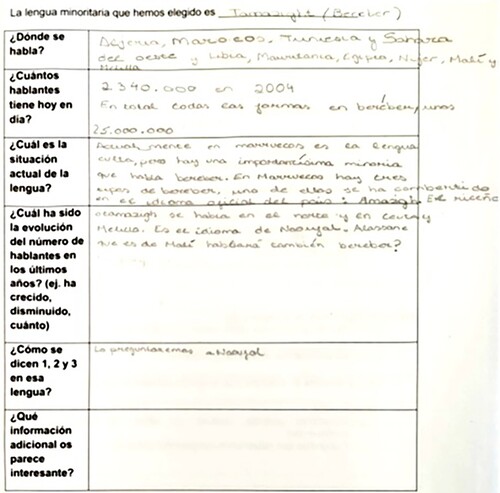

One of the units in the Spanish subject class during the first year was on the topic of sociolinguistics. The outcome of the unit was a monographic work on a minority language that would include both a written essay and an oral presentation with visual support (PPT) for broadcasting later on the school’s television channel. First, the students learned about the history and the sociolinguistic situation of Basque and then, about other six minority languages: Yaaku spoken in Kenya, Ayapaneco in Mexico, Romani in Hungary, Aranese in Spain, Tamazight in Morocco and Sherpa in Nepal. In both cases, the students activated their prior knowledge before watching the different video documentaries and carried out various activities related to the content in the three languages: identification of missing words in transcribed texts in Basque and in English, search for cognate pairs, morphological analysis of complex words and the identification of the characteristics of the expository texts. Afterwards, the students in groups had to choose one of the six minority languages and look for additional information. The final product had to be written in Spanish yet the students were encouraged to look for information in any language they wished. They were provided with a template to organise the information according to the textual characteristics of the expository texts (see ).

Figure 1. Example of a template to organise information for the monographic work on a minority language.

At the end of the unit, the students orally presented their monograph on the minority language of choice to their classmates before broadcasting it on the school’s television channel. Subsequently, there was a conversation guided by the teacher on those minority languages. When it was time to talk about the minority language Ayapaneco spoken in Mexico, the teacher directed their attention towards the comparison of its situation with the situation of Basque. For that, the teacher listed some cultural resources trying to raise awareness about the importance of having access to cultural artefacts and resources in the minority language for its maintenance and revitalisation. The conversation started in Spanish because they were in the Spanish class but changed into Basque once they started talking about types of dictionaries showing a fluid use of languages in class to mediate sociolinguistic knowledge building.

Vamos a comparar la situación del euskera, que es una lengua minoritaria, con la situación del ayapaneco. A ver, qué diferencias veis y qué similitudes. [Let’s compare the situation of Basque which is a minority language with the situation of Ayapanenco.]

el euskera hablan muchas más personas que ayapaneco. [Basque is spoken by many more people than Ayapanenco]

¿Qué más tenemos? ¿Diccionarios? [What else do we have? Dictionaries?]

muchos. [many.]

¿qué tipos? [What type?]

sinónimos y antónimos. [synonyms and antonyms.]

erdera-euskera. [Spanish-Basque.]

ingles-euskera, euskera-ingles. [English-Basque, Basque-English.]

Zuek uste duzue eskola honetan testu liburuak dituztela? [Do you think they have textbooks in this school?]

Ez! [No!]

Eta guk baditugu? [And, do we have them?]

Bai! [Yes!]

liburutegi bat dutela?[[do you think] that they have a library?]

Ez! [No!]

eta guk baditugu?[and, do we have them?]

Bai! [Yes!]

liburuak ditugu?[do we have books?]

Bai! [Yes!]

zer gauza gehiago ditugu.[What else do we have?]

telebista.[Television.]

ba bai. Irratia, … [Yes, indeed. Radio, …]

Orain nire azken galdera, konparatuta Ayapanekok duena eta guk euskaraz duguna, zelan uste duzue izango dela Ayapanekoren geroa eta euskararen geroa? [Comparing what Ayapaneko has and what we have in Basque, how do you think the future of Ayapaneko and the future of Basque will be?]

Zuek nork uste duzue izango duela aukera gehiago aurrera egiteko, ayapanekok ala guk? [Who do you think will have more chances to survive?]

guk! [We will!]

The unit on sociolinguistics of minority languages offered an opportunity for the students to understand the critical role of cultural artefacts as well as the number of speakers in the maintenance and revitalisation of the minority languages and they were able to conclude that Basque has better chances to survive in the future than other minority languages. Furthermore, the Tamazight language was included in the project because one of the participating students (ST22) spoke it. The six students of the group filmed a video and edited it to create a 2:54-minute-long documentary to be broadcast on the school TV channel. The documentary starts by talking about general issues such as the importance of languages, the effects of language loss, etc. Then they added more detailed information about Tamazigh: where it is spoken, number of speakers, language family, its own alphabet (Tifinagh) and the historical development of the language. The video ended with the following message: ‘Let’s respect the diversity of languages!’. During the work on the script, the teacher asked some questions to guide the students in their work and also to help them to develop critical language awareness:

¿Fue este (Tamazigh) tu (ST22) primer idioma? [Was Tamazight your (ST22's) first language?]

Sí [Yes]

y esa será una de las razones para elegirla ¿no? ¿Y en casa qué hablas? ¿Qué? pues tienes que decirnos también ‘es el idioma (Tamazigh) que hablo en casa’, pero también hablas otro idioma en casa (Arabe), ¿no? [And, that will be one of the reasons to choose it, right? And, what language do you speak at home? What? Well, you also have to tell us ‘it is the language (Tamazigh) I speak it at home’, but you also speak another language at home (Arabic), right?]

No mucho. [Not much.]

No mucho? Bueno pero lo cuentas también, para que veamos la realidad, eso es importante. [Not much? Well, you mention it so that we see the reality, what is going on, that is important.]

Yes (nodded).

Hori da (Basque). Y luego lo del francés le voy a preguntar por qué en su país el idioma, eh ST22, el idioma de la cultura, de la universidad, de los estudios es también el francés, por eso tus padres saben francés, ¿vale? Y es un país con un montón de idiomas no solo esos tres (tamazigh, árabe y francés) bastantes más. [That’s it. And then, I’m going to ask him about French, because in your country, the language of culture, of university, of studies is also French. That’s why your parents speak French, right? And it’s a country with many languages, isn’t it? Not just these three languages (Tamazight, Arabic, and French), but many more.]

Sí, ¡pero yo no sé los otros! [Yes, but I don’t know the others.]

¡Claro! ¡No sabes todos los idiomas! [Of course! You don’t know all languages!]

Gogoratzen zara zure eskolaz? [Do you remember your (previous) school?]

Ez asko, baina zen desberdina, honekin konparatuta zen desberdina. Bueno gauza batzuk ez, batzuk ziren antzerakoak, baina besteak desberdinak. [Not much, but it was different compared to this one. Some things were similar, but others were not.]

Again, the students worked on the sociolinguistic aspect of minority languages as well as on the morphological aspect of the three languages of the school. As an activity prior to the Quiz Show, the students read a text about the size of Basque compared to other minority languages (number of speakers, presence on the internet, etc.). They then answered four multiple-choice questions about the content and an open question: What do you think the situation of Basque will be in the future? In order to explore the perceptions of the students towards Basque, the responses were analysed and classified as optimistic future, pessimistic future and uncertain future. According to the responses collected, the future of Basque is optimistic for 38.5% of the students, pessimistic for the other 38.5% and uncertain for the rest 27% (see ). This activity also served to collect the views students had on what helps a minority language to survive.

The use of the language was the most mentioned factor to ensure the future of Basque. Others also mentioned the importance of teaching and learning Basque. For instance, student 06 noted that

Euskara gero eta gehiago hitz egingo da. Gero eta jende gehiago euskara ikasten animatzen delako eta jende gehiago eskoletan D eredura apuntatzen delako. Kaleetatik gehiago entzuten delako euskara [Basque will be spoken more and more. Because more and more people are encouraged to learn Basque and more and more people are enrolled in model D at schools. Because Basque is heard more out in the streets].

Familietan gehiago erabiliko dela, eskoletan, kalean, etxean, telebistan euskaraz kanal gehiago egongo direla eta familiak beren haurrei irakasten badiete gehiago handituko dela pentsatzen dut [I think that it will be used more in families, in schools, out in the street, at home, that there will be more Basque channels on television and that if families teach their children it will increase more].

Among the students who showed pessimism towards the future of the Basque language, there were student 07 and student 09. These two stated that Basque would disappear in time: ‘etorkizunean euskara desagertu egingo da’. The reasons for that are again the use of the language. On the one hand, student 07 admitted that the reason was that he did not speak in Basque with his friends. Student 09 said, on the other hand, that because of the increasing desire to travel abroad, foreign languages would replace Basque in the future:

Jendeak askoz garrantzi handiagoa ematen die beste hizkuntzei, gehienbat bidaiatzea gustatzen zaigulako (…) Orduan, atzerriko hizkuntza erabiliko dute eta euskara atzean utziko dute [people consider other languages more important because we like traveling (…) then, a foreign language will be used and we will leave Basque behind].

The students were aware that although Basque has the opportunity to survive because it will be transmitted within families, taught in schools, and used in and outside school, its maintenance is not guaranteed due to threats such as the use of foreign languages for global communication.

Pedagogical translanguaging and the perception of languages

The second research question aimed at answering the way pedagogical translanguaging can alter students’ perception of languages and their status. Despite the relatively little presence of the English language in the Basque society, the data analysis has brought to the surface the high value of this language among participants. Some activities of the intervention at a certain point might have emphasised this position. There were translanguaging activities intended to develop the metalinguistic awareness of the students by comparing linguistic elements of the three languages. These activities were integrated into the materials of the three language subjects rather than just in one. Many students highlighted that translanguaging materials were particularly useful for learning English even when referring to activities completed in the Basque and Spanish subjects. The following interaction was collected during a focus group discussion about a Spanish unit.

Gehiago, gutxiago edo berdin ikasi duzu hiru hizkuntza batera erabiltzerakoan? [Have you learned more, less or the same when using the three languages at the same time?]

Gehiago. Beste hitz berriak ikasi ditudalako. [More. Because I have learned other new words].

Zein hizkuntzatan ikasi dituzu? [In what language did you learn them?]

Ingelesez.[In English]

Eta euskaraz ikasi dituzu? [And, have you learned them in Basque?]

Gutxiago. [Less]

Zer ikasi duzue hiru hizkuntzekin batera lan eginez? [What have you learned working with the three languages together?]

Ingelesez sinonimoak eta antonimoak. [Synonyms and antonyms in English.]

Gauza asko hizkuntza askotan eta beste hizkuntzekin izenondoak eta gramatikako gauzak lantzea. [Many things in many languages and to work with adjectives and other grammatical aspects in other languages.]

Ingelesa gehiena, ingeleseko sinonimo asko ez nekizkielako. [Mostly in English, because I didn’t know many synonyms in English.]

The high status of English among students was also captured when the researcher directly asked them about the importance each language had for them. For the majority of the students, English and Spanish were the most important languages and although many of them showed a certain emotional attachment to Basque, they did not think that it was as important as the other two languages. In the case of student 04, according to the teacher, both parents were able to speak Basque and used it at home. Yet, the student underlined the importance of Spanish and English above Basque.

Gaztelania da niretzako inportanteagoa ze hitz egiten dut leku askotan eta ingelesa oso inportantea ze niretzako da inportanteena momentu honetan. [Spanish is more important because I use it in many places and English is very important for me because it is the most important one in this moment.]

Oso ondo, eta zuretzako euskara ez da garrantzitsua? [Very well, and Basque is not important to you?]

Ez. [No.]

eta ingelesa? [and English?]

Jende guztiak jakin behar du ze da hizkuntza ofiziala. [Everybody must know it because it’s the official language.]

Discussion

The notion of pedagogical translanguaging includes a variety of instructional strategies with the aim of developing multilingual competence and multiliteracy (Cenoz & Gorter, Citation2021; Leonet & Saragueta, Citation2023). This study aimed to explore the possibilities of pedagogical translanguaging as a strategy to develop critical language awareness among a group of primary school students from the Basque Autonomous Community. Upper primary school students participated in a two-year long intervention based on pedagogical translanguaging to develop multilingual competence and language awareness. Through activities such as the recognition of cognates or the composition of compound and derived words in the three school languages, they developed metalinguistic awareness (see Leonet et al., Citation2020; Leonet & Saragueta, Citation2023). They also worked on comparing the sociolinguist realities of different languages around them and around the world paying special attention to minority languages. Those activities facilitated the development of critical language awareness and fostered the emotional bond with Basque while promoting a positive attitude towards linguistic diversity which the students highly valued. Other studies have also explored the potential of translanguaging pedagogies to enhance awareness and feelings of empowerment among minority students (Carbonara & Scibetta, Citation2022; Creese & Blackledge, Citation2010; Leonet et al., Citation2017; Little & Kirwan, Citation2018). However, the focus was not on regional minority languages in any of those studies.

Regional minority languages are often spoken by a small number of people and are limited to a specific geographic area within a nation-state where a stronger language is the official language. This makes them particularly vulnerable. These languages often coexist with higher-status languages, and even with other minority languages spoken by foreign language communities. In such contexts, we propose a sociolinguistically informed approach (Wilson & Pascual y Cabo, Citation2019) for implementing pedagogical translanguaging strategies in the classroom. This approach should (re)consider language ideologies, politics, and social hierarchies while celebrating linguistic diversity. The students in this study realised of the importance of school and the availability of language learning resources for the maintenance and revitalisation of minority languages, and they acknowledged the importance of family transmission as well. In addition, the reading activity related to the size of Basque and the open question about the future of this language brought insights into students’ awareness towards the situation of Basque. During the two years that the project lasted, students understood that the use of the language is critical if a minority language will survive and some of them even did so by using the first person singular as key members of society to contribute to the maintenance and revitalisation of the Basque. Previously, Leonet et al. (Citation2017) had already found that pedagogical translanguaging might influence the linguistic attitudes and ideological reconfiguration of students and advocated for sustainable translanguaging pedagogies in minority language educational contexts (see also, Cenoz & Gorter, Citation2017).

After the two-year project, during which the three school languages were used fluently in language subjects, the students’ language perception and perception of the status of the three languages had altered. While discussing the future of Basque, some students felt pessimistic because of the importance of foreign languages that is linked to the importance they think English has. Although the acknowledgement of English as the widely used language for communication is understandable, their perception of English being more important than Basque or Spanish when it has very little presence in their lives outside school was not predictable. However, previous studies conducted on language learning beliefs reported that when parents regard English as more important than the minority language the belief is reflected in their children (Arocena Egaña et al., Citation2015). Thus, their perception may be due to the influence their parents and society have on them. However, these students gave more visibility to English even if the activities were designed to strengthen either Basque or Spanish. They reported to have learned more English (grammar and vocabulary) when the outcome should have been that they had learned more in general. These findings show that the students’ perceptions of learning are shaped by their beliefs. More importantly, the analysis of the data collected in this study has surfaced the unbalanced status of the three curriculum languages (Leonet & Orcasitas-Vicandi, Citation2022).

As for the limitations of the study, gathering information about the students was challenging due to the conditions of the pedagogical intervention and the data collection procedures. Despite the students becoming accustomed to the researcher’s presence over time and the impact lessening, it is possible that her presence in the classroom will have influenced the students in some manner. Conducting focus group discussions with 5th and 6th graders was particularly challenging due to their difficulties in expressing thoughts and opinions. The present findings should be interpreted as potential trends that could be confirmed and further explored in future studies with a greater number of participants and different methodological procedures. The study could be extended to other school grades and sociolinguistic contexts both within and outside the Basque context.

In sum, the findings of this study have contributed to shedding some light on the development of critical language awareness and sociolinguistically informed pedagogical approaches, where research is scant. This study also contributes to the field that advocates for sustainable translanguaging pedagogies (Cenoz & Gorter, Citation2017; Leonet et al., Citation2017). The translanguaging project reported in this article included activities to enhance students’ metalinguistic awareness across languages and the use of their whole linguistic repertoire (Cenoz & Gorter, Citation2021), In this vein, we have identified potential risks of translanguaging pedagogies that go against the school’s and even Basque educational system’s language policy to protect Basque. Thus, to compensate for the weaker situation of the language in the social context of the school, specific activities to boost positive attitudes towards Basque were included. In accordance with Cenoz and Gorter (Citation2017), we conclude that in such sociolinguistic environments, the minority language needs its own spaces to breathe and support to compensate for its weaker situation and that translanguaging pedagogies should be previously planned considering the sociolinguistic context (Leonet et al., Citation2017). Although the findings are exploratory, they can guide future research on translanguaging pedagogies, which despite the popularity of the term, remains underdeveloped. The study offers valuable insight into the application of translanguaging pedagogies in regional minority languages, heritage language and indigenous educational contexts. Future research should explore and evaluate further pedagogical translanguaging practices that provide inclusive educational success for all students.

Geolocation information

The study was conducted in the Basque Autonomous Community (Spain).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, J., & Lightfoot, A. (2018). Translingual practices in English classroom in India: Current perceptions and future possibilities. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 24(8), 1210–1231. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1548558

- Arocena Egaña, E., Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2015). Teachers’ beliefs in multilingual education in the Basque country and in Friesland. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education, 3(2), 169–193. https://doi.org/10.1075/jicb.3.2.01aro

- Baker, C. (1992). Attitudes and language. Multilingual Matters.

- Basque Sociolinguistic Cluster. (2021a). Hizkuntzen erabileraren kale neurketa. Euskal Herria 2021. https://soziolinguistika.eus/es/proiektua/hizkuntzen-erabileraren-kale-neurketa-euskal-herria-2021-2/.

- Basque Sociolinguistic Cluster. (2021b). Hizkuntzen erabileraren kale neurketa UEMAko udalerriak eta Tolosaldea, 2021. https://soziolinguistika.eus/es/proiektua/hizkuntzen-erabileraren-kale-neurketa-uemako-udalerriak-eta-tolosaldea/.

- Beacco, J. C., Byram, M., Cavalli, M., Coste, D., Cuenat, M. E., Goullier, F., & Panthier, J. (2016). Guide for the development and implementation of curricula for plurilingual and intercultural education. Council of Europe Publishing.

- Beaudrie, S., Amezcua, A., & Loza, S. (2021). Critical language awareness in the heritage language classroom: Design, implementation, and evaluation of a curricular intervention. International Multilingual Research Journal, 15(1), 61–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313152.2020.1753931

- Bialystok, E. (1991). Metalinguistic dimensions of bilingual language proficiency. In E. Bialystock (Ed.), Language processing in bilingual children (pp. 113–140). Cambridge University Press.

- Bialystok, E. (2001). Metalinguistic aspects of bilingual processing. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 21, 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190501000101

- Blommaert, J. (2010). The sociolinguistics of globalization. Cambridge University Press.

- Busse, V. (2017). Plurilingualism in Europe: Exploring attitudes toward English and other European languages among adolescents in Bulgaria, Germany, The Netherlands, and Spain. The Modern Language Journal, 101(3), 566–582. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12415

- Canagarajah, S. (2011). Translanguaging in the classroom: Emerging issues for research and pedagogy. Applied Linguistics Review, 2(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110239331.1

- Canagarajah, S., & Liyanage, I. (2012). Lessons from pre-colonial multilingualism. In M. Martin-Jones, A. Blackledge, & A. Creese (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of multilingualism (pp. 67–83). Routledge.

- Candelier, M., Camilleri-Grima, A., Castellotti, V., de Pietro, J. F., Lőrincz, I., Meißner, F. J., Noguerol, A., & Schröder-Sura, A. (2012). Framework of reference for pluralistic approaches to languages and cultures (FREPA/CARAP). Council of Europe Publishing.

- Carbonara, V., & Scibetta, A. (2022). Integrating translanguaging pedagogy into Italian primary schools: Implications for language practices and children’s empowerment. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(3), 1049–1069. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2020.1742648

- Cenoz, J., & Arocena, E. (2018). Bilingüismo y multilingüismo/bilingualism and multilingualism. In J. Muñoz-Basols, E. Gironzetti, & M. Lacorte (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of Spanish language teaching (pp. 417–431). Routledge.

- Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2017). Minority languages and sustainable translanguaging: Threat or opportunity? Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 38(10), 901–912. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2017.1284855

- Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2021). Pedagogical translanguaging (elements in language teaching). Cambridge University Press.

- Clark, E. V., & Ivanic, R. (1997). Critical discourse analysis and educational change. In L. van Lier & L. Corson (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education (pp. 217–227). Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Council of Europe. (1992). Regional or minority languages. European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. https://www.coe.int/en/web/european-charter-regional-or-minority-languages.

- Council of Europe. (2001). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge University Press.

- Creese, A., & Blackledge, A. (2010). Translanguaging in the bilingual classroom: A pedagogy for learning and teaching? The Modern Language Journal, 94(1), 103–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2009.00986.x

- Douglas Fir Group. (2016). A transdisciplinary framework for SLA in a multilingual world. The Modern Language Journal, 100(1), 19–47.

- Duarte, J., & Günther-van der Meij, M. (2018). A holistic model for multilingualism in education. EuroAmerican Journal of Applied Linguistics and Languages, 5(2), 24–43. https://doi.org/10.21283/2376905X.9.153

- Duranti, A. (2000). Antropología Lingüística. Cambridge University Press.

- García, O., & Alonso, L. (2021). Reconstituting US Spanish language education: US Latinx occupying classrooms. Journal of Spanish Language Teaching, 8(2), 114–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/23247797.2021.2016230

- García, O., Flores, N., & Woodley, H. (2012). Transgressing monolingualism and bilingual dualities: Translanguaging pedagogies. In A. Yiakoumetti (Ed.), Harnessing linguistic variation to improve education (pp. 45–75). Peter Lang.

- García, O., & Kleyn, T. (2016). Translanguaging theory in education. In O. Garcia, & T. Kleyn (Eds.), Translanguaging with multilingual students: Learning from classroom moments (pp. 9–33). Routledge.

- García, O., & Lin, A. M. Y. (2016). Extending understandings of bilingual and multilingual education. In O. Garcia, A. Lin, & S. May (Eds.), Bilingual and multilingual education (3rd ed., pp. 1–20). Springer.

- García, O., & Otheguy, R. (2020). Plurilingualism and translanguaging: Commonalities and divergences. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 23(1), 17–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2019.1598932

- García, O., & Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Garrett, P., & Cots, J. M. (2018). The Routledge handbook of language awareness. Routledge.

- Gorter, D., Cenoz, J., & der Worp, K. V. (2021). The linguistic landscape as a resource for language learning and raising language awareness. Journal of Spanish Language Teaching, 8(2), 161–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/23247797.2021.2014029

- Hélot, C., Frijns, C., Gorp, K., & Sierens, S. (2018). Language awareness in multilingual classrooms in Europe: From theory to practice. De Gruyter.

- Hélot, C., & Young, A. (2006). Imagining multilingual education in France: A language and cultural awareness project at primary level. Imagining Multilingual Schools: Languages in Education and Glocalization, 69–90.

- Hofer, B., & Jessner, U. (2019). Multilingualism at the primary level in South Tyrol: How does multilingual education affect young learners’ metalinguistic awareness and proficiency in L1, L2 and L3? The Language Learning Journal, 47(1), 76–87.

- Holguín Mendoza, C. (2018). Critical language awareness (CLA) for Spanish heritage language programs: Implementing a complete curriculum. International Multilingual Research Journal, 12(2), 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313152.2017.1401445

- Jessner, U. (1999). Metalinguistic awareness in multilinguals: Cognitive aspects of third language learning. Language Awareness, 8(3-4), 201–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658419908667129

- Jones, K., Martin-Jones, M., & Bhatt, A. (2000). Constructing a critical, dialogic approach to research on multilingual literacy: Participant diaries and diary interviews. In M. Martin-Jones & K. Jones (Eds.), Multilingual literacies: Reading and writing different worlds (pp. 319–351). John Benjamins.

- Lasagabaster, D. (2005). Attitudes towards Basque, Spanish and English: An analysis of the most influential variables. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 26(4), 296–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434630508669084

- Leeman, J. (2018). Critical language awareness and Spanish as a heritage language: Challenging the linguistic subordination of US Latinxs. In J. Leeman (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of Spanish as a heritage language (pp. 345–358). Routledge.

- Leeman, J., & Serafini, E. J. (2016). Sociolinguistics for heritage language educators and students. Innovative strategies for heritage language teaching: A practical guide for the classroom, 56–79.

- Leonet, O., Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2017). Challenging minority language isolation: Translanguaging in a trilingual school in the Basque Country. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 16(4), 216–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2017.1328281

- Leonet, O., Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2020). Developing morphological awareness across languages: Translanguaging pedagogies in third language acquisition. Language Awareness, 29(1), 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2019.1688338

- Leonet, O., & Orcasitas-Vicandi, M. (2022). Learning languages in a globalized world: Understanding young multilinguals’ practices in the Basque Country. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2047986

- Leonet, O., & Saragueta, E. (2023). The case of a pedagogical translanguaging intervention in a trilingual primary school: The students’ voice. International Journal of Multilingualism, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2023.2224009

- Leung, C., & Valdés, G. (2019). Translanguaging and the transdisciplinary framework for language teaching and learning in a multilingual world. The Modern Language Journal, 103(2), 348–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12568

- Little, D., & Kirwan, D. (2018). Translanguaging as a key to educational success: The experience of one Irish primary school. In P. van Avermaet, S. Slembrouck, K. van Gorp, S. Sierens, & K. Maryns (Eds.), The multilingual edge of education (pp. 313–340). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Makoni, S., & Pennycook, A. (2005). Disinventing and (re) constituting languages. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies: An International Journal, 2(3), 137–156.

- Martínez de Luna, I. (2018). Euskararen biziberritzea, eleaniztasunaren garaiko erronka. BAT: Soziolinguistika, 106(1), 47–64. https://soziolinguistika.eus/files/bat106_web_1.pdf#page=48.

- Moodley, V. (2007). Codeswitching in the multilingual English first language classroom. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 10(6), 707–722. https://doi.org/10.2167/beb403.0

- Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Leech, N. L. (2007). Validity and qualitative research: An oxymoron? Quality & Quantity, 41(2), 233–249. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-006-9000-3

- Otheguy, R., García, O., & Reid, W. (2015). Clarifying translanguaging and deconstructing named languages: A perspective from linguistics. Applied Linguistics Review, 6(3), 281–307. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2015-0014

- Prada, J., & Nikula, T. (2018). Introduction to the special issue: On the transgressive nature of translanguaging pedagogies. EuroAmerican Journal of Applied Linguistics and Languages, 5(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.21283/2376905X.9.166

- Selvi, A. F. (2019). Qualitative content analysis. In J. McKinley & H. Rose (Eds.), The Routledge hand-book of research methods in applied linguistics (pp. 440–452). Routledge.

- Vogel, S., & Garcia, O. (2017). Translanguaging. In G. Noblit & L. Moll (Eds.), Oxford research encyclopedia of education (pp. 1–18). Oxford University Press.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). In M. Cole, V. Jolm-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman (Eds.), Mind in society: Development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvjf9vz4

- Williams, C. (1994). Arfarniad o ddulliau dysgu ac addysgu yng nghyddestun addysg uwchradd ddwyieithog [An evaluation of teaching and learning methods in the context of bilingual secondary education] [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. University of Wales.

- Wilson, D., & Pascual y Cabo, D. (2019). Linguistic diversity and student voice: The case of spanish as a heritage language. Journal of Spanish Language Teaching, 6(2), 170–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/23247797.2019.1681639

Appendix

The board for the Quiz Show and examples of the questions/tasks