ABSTRACT

The private rental market costs are placing a burden on household budgets, thus significant pressure is on governments and private housing organisations to supply more social and affordable housing solutions. This research evaluates the key elements of medium- and high-density liveable and accessible social and affordable urban housing precincts. Focusing on investigations into an Australian housing case study, the authors establish a liveability framework to improve understanding of whole-of-life needs. Through a comprehensive literature review, a case study and a series of in-depth interviews with key stakeholders from the housing sector five key elements were identified. These key elements include: (1) Liveability, (2) Accessibility, (3) Value equation, (4) Regulatory and policy environment, and (5) Adoption and overcoming barriers. The liveability framework will form the basis of a set of quality standards that can be used to guide precinct planning, design development and management.

摘要

私人租赁市场的成本给家庭预算造成了负担,因此政府和私人住房组织面临着提供更多社会和经济适用房解决方案的巨大压力。本研究评估了中高密度宜居和无障碍社会经济适用房城市住宅区的关键要素。通过对澳大利亚住房案例的调查,作者建立了一个宜居性框架,以提高对整个生活需求的理解。通过全面的文献综述、案例研究以及对住房领域主要利益相关者的一系列深入访谈,作者确定了五个关键要素。这些关键要素包括:(1)宜居性;(2)可达性;(3)价值等式;(4)监管和政策环境;以及(5)采用和克服障碍。宜居性框架将成为一整套质量标准的基础,可用于指导区域规划、设计开发和管理。

1. Introduction

There is a critical shortage of accessible residential housing in Australia that has implications for the 4.4 million Australians living with disability, older Australians and their carers and families (Australian Building Codes Board Citation2020, p. 1). Accessible housing is considered as “any housing that includes features which enable use by people either with a disability or transitioning through their life stages” (Queenslanders with Disability Network, QDN Citation2017, p. 7). Considering the current and projected national prevalence of populations with functional impairments and trends of ageing, the WHO Housing and Health Guidelines established that an adequate proportion of the housing stock should be accessible to people with functional impairments (WHO Citation2018).

The COVID-19 pandemic has further highlighted the need to ensure the liveability of higher density urban housing. Liveability refers to “the degree to which a place, be it a neighbourhood, town or city, supports quality of life, health and wellbeing for the people who live, work or visit” (London Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment as cited in Wu et al. Citation2018, p. 772). There is an urgent need for more liveable and accessible medium- to high-density urban housing precincts to enhance quality of life. While accessibility is people-centric, it is also place-dependent. Hence, planning for liveability is paramount to ensure accessible housing and the people within those housing have access to features that support the quality of life.

The challenge is compounded as many of these Australians requiring accessible housing are under financial stress and reliant on social and affordable housing (SAH). In Australia, the primary providers of SAH are state governments and private housing organisations. However, state social housing registries highlight demand outstrips supply across Australia, and in many other countries (Pawson and Gilmour Citation2010).

Key challenges to embedding accessibility principles in SAH include a lack of client understanding; process (procurement and tendering, timing, cooperation and networking); knowledge and the lack of a common language; and the availability of methods and tools of analysis (Crabtree and Hess Citation2009, Häkkinen and Belloni Citation2011). Information about these characteristics within SAH, particularly in high density precincts, is dispersed and incomplete. This research sought to address how to better embed these features in SAH and improve pathways for the adoption of these outcomes through: (i) clarifying the value equation (both tangible and intangible) to enable the delivery of whole-of-life solutions; and (ii) building community acceptance of such investment in homes and urban precincts.

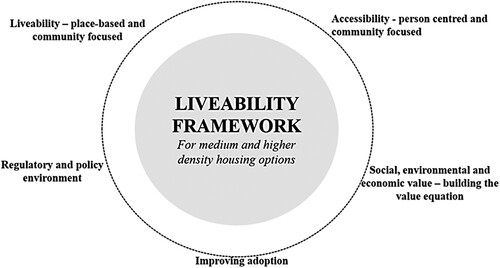

The findings of this research were derived from a comprehensive literature review, a case study and 12 in-depth interviews with key stakeholders from the housing sector (public, private and not-for-profit). The findings form the basis of a Liveability Framework for Social and Affordable Medium to High Density Housing (see and Appendix 2) utilising five key elements: (1) Liveability – place-based and community focused, (2) Accessibility – person centred and community focused, (3) Value equation – cost benefit, (4) Regulatory and policy environment, and (5) Adoption and overcoming barriers. The Australian case study was undertaken in the Green Square Close precinct in Fortitude Valley, Brisbane, which includes 80 social and affordable homes, developed and managed by Brisbane Housing Company (Reid et al. Citation2022). The case study focus was on the larger precinct interaction rather than on the housing itself, thus integrating a people centred precinct approach.

The research and development of the Liveability Framework, contributes to the SAH body of knowledge and practice, highlighting key elements of social and affordable higher density housing. The framework also includes a series of guidelines to be used to develop project and precinct-based, value focussed standards and targets to drive adoption of better outcomes and promote community acceptance of delivering whole-life-solutions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Emergence of Accessible Housing and Design Considerations

Design plays a significant role in the delivery of accessible dwellings. Easthope (Citation2020) pinpoint design quality, both at the building and neighbourhood scale, as critical in medium and higher density housing and precincts to build strong social infrastructure. Easthope et al., building on Parkinson (Citation2014), links the quality of apartment design and the presence of good infrastructure to residents’ wellbeing and satisfaction.

Local services and facilities are also drivers for social networks, creating processes of commonality that support a sense of control of local public space (Atkinson Citation2008). Maclennan et al. (Citation2015, p. 36) suggest that “public investment in infrastructure and this includes housing, can have subtle, sometimes small but catalytic effects for people and place”. For example, housing and neighbourhood outcomes can impact inhabitants’ health, and childhood learning (e.g. school dropout rates and overall performance) and development (e.g. sense of safety, belonging and pro-social behaviour). Maclennan et al. (Citation2015) report highlights walkability, which is not only related to residents’ physical activity, but “reflects land use patterns, residential densities and street layouts, as well as access to public transport” may impact health outcomes for neighbourhoods (Maclennan et al. Citation2015, p. 41).

The global COVID-19 pandemic has further highlighted the impact of “living locally”. Specifically, access to open space and appropriate social infrastructure is integral for residents of SAH (AHURI Citation2020a). AHURI’s research has been crucial to creating an understanding of the main issues related to these areas, and how the interaction of the different forces has over time shaped Australian housing stock. We can divide the AHURI literature covering these issues into two main subjects: (i) design and governance; and (ii) integrated services and housing. Key lessons highlighted in the above AHURI research are summarised in .

Table 1. AHURI research summary.

2.1.1. Barriers and Challenges to Delivering Social and Affordable Housing

There are significant constraints in the delivery of infrastructure and amenities within high density neighbourhoods. The planning process and coordination, as well as securing funding (i.e. developer contributions, voluntary and/or negotiated agreements) between State and locally managed urban re/developments are complex. State-led projects have higher coherence in the governance of processes and outcomes but lack local engagement; while the locally led processes present the opposite problem. Research has highlighted the importance of connectivity in overcoming some of these planning and process challenges (Easthope Citation2020). Whilst there is a strong emphasis on public and active transportation in design there is often a lack of parking areas and car congestion within many high density housing precincts. Researchers have also called for a rethink of the physical connection between employment opportunities, affordable housing and transportation for low-income households to enhance urban productivity (Easthope Citation2020, Pill Citation2020). This highlights the importance of a strong link between good strategic spatial designs and governance.

The governance and financing support for housing and services is essential. Pinnegar (Citation2011) identified a range of international examples where cross-sectoral partnerships have been used within the housing and urban policy context. Their case study demonstrates that a flexible approach to financing rules and policy based on mixed financing strategies are critical in the successful delivery of mixed-tenure housing and neighbourhoods; as well as to facilitate delivery and renewal.

Barriers to the uptake of liveability and accessibility features in housing markets are considered by some to be institutional rather than technological. Research highlights these impediments include economics; a lack of client understanding; process (procurement and tendering, timing, cooperation, and networking); knowledge and the lack of a common language; and the availability of methods and tools of analysis (Crabtree and Hess Citation2009, Häkkinen and Belloni Citation2011). Häkkinen and Belloni (Citation2011, p. 240) note that “hindrances can be reduced by learning what kind of decision-making phases, new tasks, actors, roles and ways of networking are needed”.

2.1.2. Role of Frameworks in Assessing and Understanding Liveability and Research Gap

There is a need for comprehensive assessment combining social, functional and aesthetic dimensions and relationship between city fabric and residential environment. Giap et al. (Citation2014) present a comprehensive assessment of residential environment liveability as a composition of external factors affecting the individual, or group of individuals, impacting their personal development, health, well-being, and the positive development of the entire society.

While there are studies focussed on residential environments in general, there is limited research focussing on a comprehensive framework for assessing SAH. Considering the global and local precedents and barriers to the integration of liveability and accessibility into the housing markets there is a need for a more holistic approach. Addressing the research gap with an integrated approach that incorporates liveability and accessibility, this study develops a holistic liveability framework for medium- and high-density urban precincts.

Case study evidence is utilised to demonstrate across the five key elements of liveability, accessibility, social, environmental and economic value (to build the value equation), the regulatory and policy environment, and improving adoption. synthesises some of the key literature which has informed these five elements.

Table 2. Summary of key literature.

The economic and social burden and impact of integrating sustainable design features into homes have been a long-term discussion for policymakers, industry and consumers (Edenhofer et al. Citation2014). Debate has focussed on up-front versus whole-of-life costs (ABCB Citation2019). It is also evident that building high-density housing, without considering liveability of both the home and the surrounding community, is no longer viable (Reid et al. Citation2022). There remains a lack of knowledge of a holistic and integrated need to deliver affordable and social housing in higher-density urban precincts. The outcomes of this research develop our understanding of liveable and affordable higher density housing precincts.

2.1.3. Proposed Conceptual Framework

Based on the literature review a conceptual framework (presented in ) was developed that identified five elements (). The goal of a conceptual framework was to identify, describe concepts and see the interrelationships between concepts (Rocco and Plakhotnik Citation2009). The conceptual framework provides an understanding of parties with whom engagement will need to occur and in what context impacts can be considered to guide uptake and adoption of improved liveability and accessibility in urban housing precincts. The conceptual framework grounds the study in the existing knowledge bases, through the literature and empirical research, to advance knowledge.

3. Research Approach

An exploratory research approach was undertaken in this study. This approach allows evaluation of key elements of the liveability framework and provides groundwork for further research. The research approach consists of two key methods including a comprehensive literature review and a case study supported by semi-structured interviews. The research methods adopted are based on describing the situation to develop and validate the framework, rather than producing replicable findings (Johansson Citation2007). Exploratory research approaches are effective in identifying and describing narratives to inform policy development.

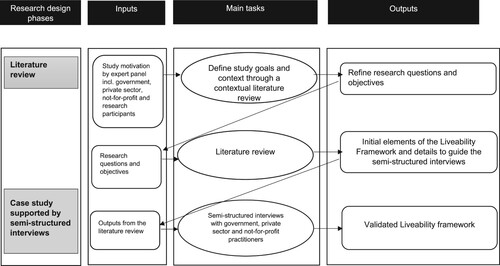

illustrates the key design phases, inputs, tasks and outputs. Firstly, the study goals were defined and a contextual literature review was carried out. Through the literature review, the initial five elements of the liveability framework were identified. Secondly, a case study was selected and a series of semi-structured interviews with expert stakeholders were carried out to evaluate and refine the key elements/sub-elements of the liveability framework.

3.1 Case Study Description

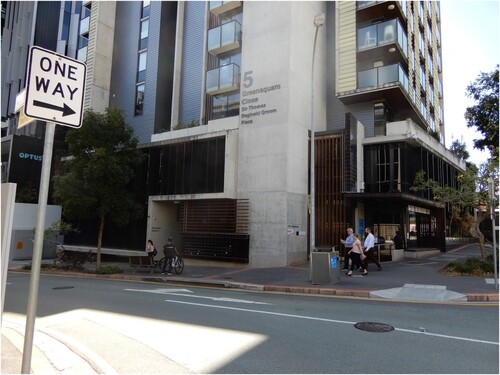

The Green Square Close precinct () was selected for this case study due to the opportunities it offers to test and develop the liveability framework. Situated in Fortitude Valley, approximately 1.5 kilometres from the Brisbane Central Business District, in the state of Queensland, Australia. Fortitude Valley and the adjacent Bowen Hills precinct have undergone significant urban renewal and redevelopment over the last decade. The precinct offers a demonstration of a planned urban environment, with consideration for design quality from social and environmental along with commercial perspectives, and offers opportunities for local, neighbourhood and district scale assessment. Finally, the precinct provides considerable opportunities for connectivity and urban amenity in this area, though not necessarily accessible.

Green Square Close is home to a multi-storey SAH property, for 80 households, that was designed, developed and operated by Brisbane Housing Company (BHC). Opened in 2010 the property was part of a Brisbane City Council (BCC) led development that incorporates within the larger precinct government and commercial offices, social support services and ground level retail outlets. Green Square Close is one of BHC’s 1,700 wholly owned social and affordable housing properties (Minnery and Greenhalgh Citation2016). Incorporated in 2002, BHC is a registered Tier 1 Community Housing Provider (CHP) that has earned a reputation as a solid and reliable organisation, built through effective working relationships and a personalised approach to customer service (Brisbane Housing Company Limited Citation2022).

3.2 Data Collection: Semi-Structured Interviews

Qualitative interviews were undertaken to test and develop the conceptual framework through considering features of an existing urban housing precinct from the expert lived perspective. Semi-structured interviews were undertaken with 12 representatives [coded as SI1-SI12] of expert stakeholder groups as evidenced in . The interview question guide (Appendix 1), derived from the literature review, was developed to inform discussion and test the conceptual liveability framework. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee.

Table 3. Interview participant details.

3.3 Data Analysis: Thematic Analysis of Qualitative Data

Interviews were conducted online, digitally recorded and transcribed. Data reduction methods were used to analyse the information (Miles and Huberman Citation1994). A thematic analysis method was applied to identify emerging themes with a combination of inductive and deductive reasoning approaches (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). The analysis began with a deductive or theory-driven coding system (A-priori codes) using the elements of the liveability framework, while creating additional new nodes/elements (In-vivo codes) inductively from emerging interview data. Content analysis was carried out on the company and related websites, site visit notes, and company tenant survey results, to triangulate data.

4. Findings and Discussion

The five elements from the conceptual liveability framework were used to guide the thematic analyses and form the structure for this section: (1) liveability – place-based and community-focused, (2) accessibility – person centred and community focused, (3) value equation – cost benefit, (4) regulatory and policy environment and (5) adoption and overcoming barriers.

4.1 Liveability – Place-Based and Community-Focussed

Stakeholder insights on liveability features were evident across the key elements of integrated and inclusive place-based planning, connectivity to nature, biodiversity, ventilated spaces, safety (design and awareness), connectedness (natural, social, physical, and virtual), community and social wellbeing, and continuous improvement. highlights some stakeholder comments relating to this element.

Table 4. Liveability sub-elements and selected stakeholder comments.

Stakeholders noted the value of meeting places and green space, with accessibility being important (e.g. level thresholds, compliant ramps). Community engagement and buy-in were essential along with engagement with multiple stakeholders to help deliver sustainable and green outcomes.

The value of connectivity to nature, social networks, and the physical and virtual realms was highlighted. Access to internal green space and significant cross-ventilation, along with alternate circulation routes (especially in a pandemic environment) provide significant benefits. Mesh security doors provide a transition to the unit, moderating ventilation, privacy and access. For example, “Splitting building in and cross and long-way ventilation enable flyscreen doors as transition to the unit” [SI11]. Gardens on private balconies and communal areas can provide residents with opportunities to choose their own plants. The benefits of generous open and communal spaces, and access to support services and activated spaces, were also noted. Virtual access was highlighted as problematic, with wi-fi being unaffordable among many residents on support pensions.

Design for and awareness of safety is crucial with secure entry, lift and floor access (via swipe card) important features. Mechanisms discussed include onsite management and staff (24/7 preferable), cameras, access passes and gates. Building a relationship between residents and local police to talk about personal and community safety was also a benefit.

Community and social well-being benefits from having access to mental health support services onsite, and demonstrating an understanding of liveability, provides dignified opportunities for residents. A central hub or “go-to” housing support agency is needed. For example, “The substring residents do tend to connect with Communify as one of the key support in the area” [SI7].

Continuous improvement is an important element in a changing environment. Evidence of the need for improvement can be gathered via post-occupancy surveys, regular resident surveys, informal feedback and incident reports. Effective ways of managing such data, however, remain a challenge for resource constrained community housing providers.

The case study demonstrated evidence across these five sub-elements, especially with common characteristics such as inclusive spaces (on-site community spaces), connectedness (through natural green spaces, communal areas and activating spaces) and safety design features (swipe card accesses, safety support and awareness) that influences the social wellbeing of residents. The findings align and add to the people and place design framework which defines liveability as the degree to which a place, be it a neighbourhood, town or city, supports quality of life, health and wellbeing for the people who live there (Newman Citation2020).

4.2 Accessibility – Person-Centred and Community-Focused

Accessibility in the context of this study was considered across a range of life needs, including providing for those with temporary or permanent disabilities, aging, and young residents. Accessibility was examined under the five key elements: (1) walkability; (2) accessibility to employment; (3) precinct accessibility; (4) equitable access, and (5) visitability. Most interview participants highlighted access to amenities as a critical enabler towards person centred and community focussed outcomes.

There is a need for accessible and easy-to-negotiate ground planes and footpaths to help enhance walkability in higher density precincts. Siting housing precincts close to train and bus services, community services or other resources to enable easy access for residents, particularly for those with no cars, is needed. Walkability can also help reduce passive commute times and facilitate access to employment to improve quality of life. Equitable, clear and obvious access, for people in wheelchairs, and also the hearing and vision impaired, is important. For example, “Footpaths are pretty accessible through large motorised wheelchairs, lots of tactile markers [S19]”. It was highlighted that Specialist Disability Accommodation (SDA) options available through the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) needs clarity, with accessible housing options remaining problematic. Car parking spaces are also needed to enable drop-off/collection points for those needing support to get to shops, transport or work.

Precinct access to services including health facilities, diverse social support services and free inner-city transport were highlighted, particularly in the context of site selection. Visitability can be improved with dual lift access, easy access to public transport, and access to parking for visitors, disability and support services and maintenance workers. provides examples of quotes elicited from the interviews to support each sub-component.

Table 5. Accessibility sub-elements and selected stakeholder comments.

The emergent sub-elements complement the QDN key recommendations to drive future actions including improving access to affordable private rental housing and improving access to social housing to deliver housing advocacy services that have a dedicated focus on people with disability (QDN Citation2017). This is particularly pertinent due to the aging nature of many societies.

4.3 Social, Environmental and Economic Value – Building the Value Equation

The value of a potential liveable social and affordable higher density housing development depends heavily on who would receive (or perceives that they would receive) that value, based on their needs, and the form of the development project. This theme was evaluated under four sub-elements: (1) whole-of-life benefits, (2) balancing upfront costs, (3) social and economic participation, and (4) long-term sustainability. These elements are further detailed in with key quotes elicited from the case study.

Table 6. Value equation sub-elements and selected stakeholder comments.

A whole-of-life benefits assessment in the business case stage is important, especially in mixed-use developments. This is better facilitated in situations where the asset owner retains the asset (e.g. government agencies, CHPs) as the opportunity exists to lead by demonstration. Considerable evidence demonstrates that it is more costly to retrofit, but the cost benefit of doing this is not the only driver (e.g. homeowner resistance). There are also different value equations for different projects, so benefits can be difficult to demonstrate as the value to be derived will vary significantly among the different stakeholder groups.

Healthier environments and people can take the burden off the system over time, helping to balance upfront costs. Cost–benefit analysis is difficult, however, for a housing development it is envisaged that the benefits accrue over the long term (e.g. 30 years). The difference in returns between residential and industrial/retail/commercial managed investments is also a disincentive to invest, along with land taxes on build-to-rent assets. For example, asset owners “Tend to build, own and manage the long-term needs as housing agency – in it for the long game so demonstrate benefit” [SI12]

Long-term sustainability can be improved in several ways. Floor space on lower levels can be integrated for commercial purposes and to balance the cost of housing above. However, social delinquency issues arise with building vitality if these commercial spaces are not occupied.

The elements identified under the value equation align and further contribute to social, environmental and economic values highlighted in Universal Design New York (Danford and Tauke Citation2001, Levine Citation2003) and a Submission to the Australian Building Codes options paper (ABCB Citation2019). One participant highlighted how challenging it is to demonstrate value creation in non-for-profit organisations. It was clear that there will be different value equations for different types of projects, and that the kind of value to be derived will vary significantly between different stakeholder groups.

4.4 Regulatory and Policy Environment

There was consensus from interviewees on the need for continued state government commitment to accessible housing and an achievable housing standard. This element includes three sub-elements relating to: (1) local, national and state level regulatory issues, (2) lack of whole of life business case and (3) future priority areas. These elements are further detailed in the .

Table 7. Regulatory and policy environment sub-elements of and selected stakeholder comments.

Continued advocacy is needed for SAH to be of an accessible standard. Advocacy is difficult in terms of how to operationalise, as it depends on how it is valued. Building synergies between the local outcomes and federal funding is important, with political cycles potentially presenting opportunities. Project-specific negotiated outcomes in terms of liveability (e.g. internal street, hanging gardens and natural ventilation) need to be embedded in future regulations.

To establish a whole-of-life business case, government agencies need to provide advice at the earliest opportunity (even before the business case stage). This would be easier when the asset owner has a longer time perspective. A whole-of-life business case includes embedding diversity into the community, leading to better outcomes for everyone.

The NDIS and SDA were highlighted as key priority areas which are problematic. Clarification is needed of investment linked with independent living options. The link between eligibility for public and community housing was also noted as problematic. The conflict between town planning requirements and the various state development codes was also problematic. For example, “There's obviously a conflict between the Council town planning requirements and the state development code. Federally I imagine primarily would come through the NDIS or the NDIA” [SI4].

From a consumer perspective there is confusion or a lack of education about what the NDIS is. There is a lack of information about what it is all about and what it might look like for a person which could explain lack of uptake. These findings support existing bodies of work including Queensland Housing Strategy 2017–2027 and Healthy Places, Healthy People; Health and Wellbeing Strategic Framework 2017–2026 (Queensland Health Citation2019).

With medium to high-density housing becoming the predominant property development choice it is critical to address the regulatory and policy issues across local, national and state levels. In parallel, it is important to focus on key priority areas such as consistent planning requirements and meaningful interaction with national regulations, via building codes, if the government and private housing organisations are to achieve inclusive outcomes.

4.5 Improving Adoption

Interviewees highlighted a range of barriers related to liveability, including the utilisation of community spaces and engagement within the building and precinct. Similarly, accessibility barriers focused on internal access, access to community spaces in both the building and precinct, and active and public transport options. Significant barriers within SAH inclusion were identified relating to mixed tenure, financial, regulatory, limited evidence, and accessibility. The findings highlighted that gaps to implementation are also impacted by a lack of developing a whole-of-life business, identifying a suite of targeted design criteria, creating best practice examples, mandatory standards, and forming private and public partnerships for effective investments ().

(a) Liveability

Table 8. Improving adoption sub-elements and selected stakeholder comments.

Mixed tenure is currently seen as a missed opportunity, especially in the Central Business District, where partnerships are being driven by others with a potential contribution back via SAH opportunities. Struggles exist, however, in terms of leasing or selling mixed tenure commercial and retail space, as well as mixed tenure housing options.

Economic barriers exist in delivering accessibility. For example, spending money on common outdoor spaces (though this discussion has changed in light of COVID-19) increases the cost per dwelling. For example, one participant stated “ … spending money on common outdoor spaces – cost per dwelling and the higher the proportion of outside space lifts the cost per dwelling and yield is a barrier for projects they deliver” [SI2].

The adoption of sustainable technologies, such as new ways of storing renewable energy, is also important and requires more capital investments to become affordable. Financial hardship impacts residents on low incomes to access services, like wi-fi, as many residents do not have disposable cash.

Regulatory barriers include those around fire regulations and the creation of internal streets and some development codes. For example, if a property is near train lines, heavy glazing is required. Management plans rather than prescriptions are considered the way forward. Better provision of information on accessibility features and their value, even if not immediately needed, may increase demand. Tax incentives may also increase demand for accessibility features.

There is a lack of evidence and tools to aid decision-making in budgets for accessibility and liveability features. Best-practice examples can help change lifestyles and can orient consumers towards investment in sustainable and affordable living.

(b) Accessibility

Attitudinal and behavioural barriers were evidenced in that “people don’t want to think that regulatory authority can dictate what your house looks like – but these are just guiding design features” [SI8-9]. There is behavioural resistance to grab rails etc., unless you need them, as people do not want to live in a home that looks like a hospital. There also remains a lack of willingness to pay upfront for intangible benefits of sustainability.

There is also still a preference by some to want low-set housing with access to gardens. Anti-social behaviour was also perceived as a deterrent for SAH with people not wanting to be aligned with such behaviours.

Securing development opportunities and suitable sites remains a barrier to market. Unless quantifiable, then accessibility is not included in the equation. In terms of the NDIS, high physical support needs can be funded as part of packages; however, if modifications are to be useful and helpful, they need to be tailored to the needs of the individual. Awareness among plan designers of the NDIS SDA needs improvement. Interview participants suggested a range of approaches to overcome the barriers shown in .

The emergent related to the adoption and overcoming barriers align with the needs to be considered across technical, social and regulatory barriers, using legislative, market and administrative powers highlighted in previous research (Norwegian Ministry of Children and Equality Citation2009, Bringa Citation2019).

Stakeholder viewpoints offer insights to government decision-makers and public and private housing companies to better understand the key features and benefits of SAH. It also provides an important up-front understanding of various parties with whom engagement will need to be undertaken to improve uptake and adoption of liveability and accessibility in urban housing precincts. Medium to high density SAH must have purposefully integrated liveability and accessibility elements to maximise benefits of investment and minimise future risks to communities.

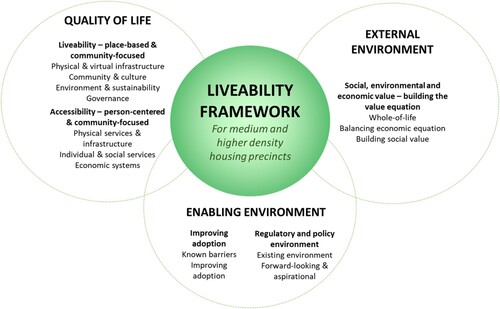

The resultant Liveability Framework and Guidelines ( and Appendix 2) target the delivery of social and affordable higher density urban housing and precincts, responsive to both person and place. The Liveability Framework integrates three key domains: (1) quality of life (i.e. liveability – place based and community focussed; accessibility – person centred, and community focussed); (2) the external environment (i.e. social, environmental, and economic value – building on value equation); and (3) the enabling environment (i.e. improving adoption, regulatory and policy environment).

5. Conclusions and Future Outlook

Through this case study and the development of the Liveability Framework, the authors contribute to the body of knowledge on liveable and accessible SAH. The research also contributes to practice with the Liveability Framework presenting a suite of essential elements to consider in designing and delivering social and affordable higher density housing. The findings can be used to develop project and precinct-based, value focussed standards and targets to drive adoption of better outcomes and promote community acceptance of delivering whole-life-solutions.

The Liveability Framework includes a range of sub-elements and guidelines, across the 5 main elements of liveability, accessibility, value equation, regulatory and policy environment, and adoption and overcoming barriers (see Appendix 2). The findings also highlighted the complexity of the SAH system so that policy and strategic settings can be better addressed by those in the public, private and not-for-profit sector designing and delivering SAH.

Understanding the inter-relatedness of various elements of housing provision in a person-centred, place-based policy environment has also been further advanced through stakeholder insights. This research is intended to guide practitioners and decision makers, and the SAH sector generally, and support decision-making around the design and development of more effective social and affordable higher density housing. It is intended that outputs be modified by users, for example, early in the project development, to communicate intent to a design team, or as a completed project appraisal tool to close the loop on project-based learnings. Thus, not all of the five elements may be relevant for the specific project at a point in time, with relevance to be identified, for example by the project team or client. Organisations are encouraged to take this framework and make it their own through aligning it with their internal systems and processes.

This exploratory study has implications for academics and industry practitioners working in the SAH sector, as well as urban policy and urban research. The development of the framework assists urban policy makers in a comprehensive list of factors that influence the development of liveable and accessible SAH in high density precincts. Clear knowledge of this will influence policy makers and the building codes around building design. In addition, this is integral for the creation of liveable and accessible medium to high density SAH precincts and homes in urban areas that are struggling to keep up with demand and supply.

The study also highlights opportunities for further research to address clear research gaps. For example, further testing and refinement of the Liveability Framework across multiple case study sites is required. The framework would also benefit from research to understand the practical challenges and barriers of implementation within private, public and not-for-profit sectors. The interrelationships, antecedents and links between different elements within the Liveability Framework also need further research and modelling. Finally, the Liveability Framework is but one tool that organisations can utilise in driving or enabling future investment in SAH. Questions arise as to why accessibility is not regulated or incorporated into SAH when so many of our most vulnerable citizens require it.

The authors acknowledge the limitations related to the lack of consumer/tenant voice in the paper and propose future research to specifically focus on consumer perspectives. Furthermore, if liveability is desired by tenants and considered best practice why is value and costs constantly used to overcome liveability provisions. There is a critical need for a targeted approach to enable purposeful investment in SAH to measure co-benefits across the various elements, rather than focussing on the cost of provision.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Queensland Government, 2021, Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design. Retrieved from https://www.police.qld.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-07/Crime%20Prevention%20Through%20Environmental%20Design%20-%20Guidelines%20for%20Queensland%202021%20v1.pdf

2 Brisbane City Council, 2019, New World City Design Guide - Buildings that Breathe. Retrieved from https://www.brisbane.qld.gov.au/planning-and-building/planning-guidelines-and-tools/neighbourhood-planning-and-urban-renewal/new-world-city-design-guide-buildings-that-breathe

3 Danford, GS and B Tauke, Eds. (2001) Universal design New York, New York, Center for Inclusive Design and Environmental Access, School of Architecture and Planning, University at Buffalo. The State University of New York, p. 21.

4 Danford, G. S. and B. Tauke, Eds. (2001). Universal design New York. New York, Center for Inclusive Design and Environmental Access, School of Architecture and Planning, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York (p. 22).

References

- AHURI. 2020a. “What has COVID-19 revealed about the liveability of our homes and neighbourhoods?” AHURI Brief. Available from https://www.ahuri.edu.au/policy/ahuri-briefs/what-has-covid-19-revealed-about-the-liveability-of-our-homes-and-neighbourhoods [Accessed 6 July 2020].

- AHURI. 2020b. “AHURI announces eight COVID-19 research projects to inform housing policy response to pandemic. "Available from https://www.ahuri.edu.au/news-and-media/news/ahuri-announces-eight-covid-19-research-projects-to-inform-housing-policy-response-to-pandemic [Accessed 15 June 2020].

- Atkinson, R., 2008. The politics of gating (A response to private security ad public space by manzi ad smith-bowers). European journal of spatial development, 6 (7), 1–8.

- Australian Building Codes Board. 2019. Accessible housing. Available from https://www.abcb.gov.au/sites/default/files/resources/2022/Consultation-report-accessible-housing-options-paper.pdf [Accessed 6 July 2020].

- Australian Building Codes Board, 2020. Building ministers’ meeting communiqué – 27 November 2020. Australia: ABCB.

- Braun, V., and Clarke, V., 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3 (2), 77–101.

- Bringa, O.R. 2019. “Moving Towards the Universally Designed Home: Part 1.” Available from https://www.betterlivingdesign.org/post/design-a-stunning-blog. [Accessed 20 July 2020].

- Brisbane Housing Company Limited. 2022. About Us. Available from https://bhcl.com.au/about-bhcl. [Accessed 26 May 2022].

- Crabtree, L., and Hess, D., 2009. Sustainability uptake in housing in metropolitan Australia: An institutional problem, not a technological one. Housing studies, 24 (2), 203–224.

- Danford, G.S., and Tauke, B.2001. Universal design New York, New York, center for inclusive design and environmental access, school of architecture and planning. University at Buffalo. The State University of New York.

- Easthope, H., et al. 2020. Improving outcomes for apartment residents and neighbourhoods. AHURI Final Report. Australia: Melbourne.

- Edenhofer, O., et al. 2014. Change 2014: Mitigation of climate change. Contribution of working group III to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press.

- Giap, T.K., Thye, W.W., and Aw, G., 2014. A new approach to measuring the liveability of cities: the global liveable cities index. World review of science, technology and sustainable development, 11 (2), 176–196.

- Häkkinen, T., and Belloni, K., 2011. Barriers and drivers for sustainable building. Building research & information, 39 (3), 239–255.

- Johansson, R., 2007. On case study methodology. Open house international, 32 (3), 48–54. doi:10.1108/OHI-03-2007-B0006.

- Kraatz, J., et al. 2020. Liveable Social and Affordable Higher Density Housing: Review of Literature and Conceptual Framework. Available from https://sbenrc.com.au/app/uploads/2020/11/SBEnrc-1.71-Liveable-Social-and-Affordable-Higher-Density-Housing-Literature-Review.pdfLendlease (2015). Design for dignity guidelines Australia. Available from https://designfordignity.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Design_for_Dignity_Guidelines_Aug_2016.pdf [Accessed 6 July 2020].

- Levine, D.2003. Universal design New York 2. Centrer for inclusive design & environmental access. University of Buffalo, The State University of New York.

- Livable Housing Australia, 2012. Livable housing design guidelines. Australia: Livable Housing Australia.

- Maclennan, D., Ong, R., and Wood, G. 2015. Making connections: Housing, productivity and economic development. Ahuri final report; 251. Melbourne, Australia.

- Miles, M.B., and Huberman, A.M., 1994. Qualitative data analysis. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications Inc.

- Minnery, J., and Greenhalgh, E., 2016. Ideas, interests and institutions in affordable housing: A case study of the Brisbane housing company. Auckland.: Australasian Housing Researchers Conference.

- Newman, P., et al., 2020. Sustainable centres of tomorrow: people and place — final industry report, project 1.62. Australia: Sustainable Built Environment National Research Centre.

- Norwegian Ministry of Children and Equality. 2009. Norway universally designed by 2025 - the Norwegian government’s action plan for universal design and increased accessibility 2009-2013. Norway, Norwegian ministry of children and equality. Available from https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/upload/bld/nedsatt-funksjonsevne/norway-universally-designed-by-2025-web.pdf.

- Parkinson, S., et al. 2014. Wellbeing outcomes of lower income renters: a multilevel analysis of area effects: Final Report. Melbourne, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI).

- Pawson, H., and Gilmour, T., 2010. Transforming Australia’s social housing: pointers from the British stock transfer experience. Urban policy and research, 28 (3), 241–260.

- Pill, M., et al. 2020. Strategic planning, ‘city deals’ and affordable housing: Final Report 331. Melbourne, Australia Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI).

- Pinnegar, S., et al., 2011. Partnership working in the design and delivery of housing policy and programs: final report 163. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI).

- Queenslanders with Disability Network, 2017. Going for gold - accessible, affordable housing now - QDN position paper on housing for people with disability. Brisbane, Australia: QDN.

- Queensland Health, 2019. Health and wellbeing strategic framework 2017 to 2026: performance review 2018–19. Brisbane, Australia.

- Reid, S., Kraatz, J., Caldera, S & Woolcock, G (2022). Creating liveable and accessible social and affordable higher density housing: the case of green square, Brisbane. In: Proceedings of the CIB world building congress (27–30 June 2022), Melbourne, Australia

- Rocco, T., and Plakhotnik, M., 2009. Literature reviews, conceptual frameworks, and theoretical frameworks: terms, functions, and distinctions. Human resource development review, 8 (1), 120–130.

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2018. WHO housing and health guidelines. Available at https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/276001/9789241550376-eng.pdf [Accessed 21 June 2022].

- Wu, H., Sintusingha, S., and Bajraszewski, R., 2018. Suburban liveability in Melbourne: a narrative approach. In: Conference proceedings of the 52nd international conference of the architectural science association, 771–777.