ABSTRACT

Within infrastructure governance research, conceptual gaps remain in how to understand public accountability’s manifestations in complex collaborative planning projects. Contrasted with literature, this case study of infrastructure governance in the Western Parkland City project in Sydney, Australia explores social understandings of accountability drawn from 56 stakeholder interviews. Multiple intersecting accountability conceptions are revealed, including institutional transparency, clear communication, social legitimacy and community engagement, governance coherence, and effective implementation capacities. In seeking meaningful accountability approaches, we emphasise the need for multidimensional, and contextually and collaboratively developed understandings of accountability towards rebuilding public trust foundations and embracing relational and systemic approaches.

摘要

在基础设施治理研究中,对于公众问责的理解在复杂合作规划项目中的表现形式仍存在概念差距。与文献形成对比的是,澳大利亚悉尼西部公园城项目的基础设施治理案例研究通过对56名利益相关者的访谈,探讨了社会对问责制的理解。其中揭示了多重交叉的问责概念,包括机构透明度、明确沟通、社会合法性和社区参与、治理一致性和有效执行能力。在寻求有意义的问责制方法时,我们强调需要对问责制进行多维度、结合背景和协作性的理解,以重建公众信任基础,并采用关系性和系统性方法。

1. Introduction

Public accountability is a critical factor for just, equitable, and effective infrastructure governance. It is generally seen as facilitating democratic constraints on power in public policy (Schedler Citation1999, Bovens and Schillemans Citation2014b), with deep (albeit complex) connections to the social legitimacy of governance (Curtin and Meijer Citation2006, Moore Citation2014, Cheyne Citation2015). The legitimacy of contemporary urban and infrastructure planning is deeply challenged by contexts of neoliberal and post-political urbanism obscuring public interests in planning (Searle and Legacy Citation2021). Existing approaches to accountability (such as via community engagement or elected politicians) are often perceived by the public as limited, superficial, or depoliticised (Hodge and Coghill Citation2007, Siemiatycki Citation2009, Amin Citation2011). Reinvigorating the democratic legitimacy of infrastructure planning requires critical attention to accountability. However, while widely viewed as a virtue within infrastructure governance scholarship, conceptual gaps remain about diverse prevailing and normative understandings of accountability and how to meaningfully foster it within complex collaborative spatial projects.

We explore manifestations of accountability through a case study of collaborative infrastructure governance in a large-scale, high-stakes urban development project: the Western Parkland City (WPC) of Sydney, New South Wales (NSW) in Australia. The findings of this case have international relevance due to common dynamics such as neoliberal planning contexts and multiscalar government collaboration. To develop conceptual foundations of public accountability, this paper first reviews literature within public administration, political science, and urban infrastructure governance fields. After introducing the case study rationale and methods, the findings sections explore diverse social understandings of accountability drawn from key institutional stakeholders. Considering the multiple intersecting conceptions of, and demands for, accountability, the discussion section presents arguments for building foundations of trust, and relational and systematic approaches to accountabilities.

2. Public Accountability in the Literature

Public accountability has been given substantial attention in public administration and political science disciplines. However, it is conceptually developed through fragmented frameworks and typologies and frequently discussed in terms of shared assumptions about first principles rather than explicit definitions (Bovens et al. Citation2014a). Accountability in governance is broadly understood as a relationship of oversight and “answerability towards others with a legitimate claim to demand an account” (Bovens et al. Citation2014a, p. 7); decision-makers being called to account with potential consequences by social systems expecting justifications for ideas and actions (Tetlock Citation1992). Public accountability notions are broad (Papadopoulos Citation2016), encompassing relational dimensions (e.g. institutional openness to the public or mechanisms to constrain the use of power) or normative dimensions of which matters require accounting due to public interests (e.g. the importance of scrutinising public investment or adapting governance to specific public interests) (Vibert Citation2014).

With shifts towards more networked or collaborative forms of governance, where government service delivery occurs in partnership with other actors, traditional understandings of centralised or hierarchical public-sector responsibilities and simple accountability systems are inadequate for the complex dynamics and relationships at play (Romzek Citation2014). Not only do accountability approaches have to make sense in complex governance systems, but they also need to be socially meaningful to effectively deliver public benefits (Fenster Citation2006). Simplistic conceptions of accountability can render governance less accessible to the public, which, in turn, effectively leads to the further weakening of accountability because of poor communication (Taşan-Kok et al. Citation2020), information transparency without the capacity to interpret it (Estache and Fay Citation2010, Meijer Citation2014), or reductive approaches such as deferring to performance measurement to avoid other approaches (Vibert Citation2014). Even frequent “conceptually empty” usage of the term is easily instrumentalised politically to avoid more substantive challenges to power (Scholtes Citation2012). It is critical that we closely consider and unpack what forms of accountability might be most socially and politically relevant within contemporary complex urban place governance.

While much-existing literature focuses on issues of governance accountability deficits, Bovens and Schillemans (Citation2014b) emphasise the importance of developing an understanding of “meaningful accountability”; shifting the normative purpose from shallow or defensive approaches to compliance and punishment (often counter-productive “box ticking” exercises) towards more deliberatively designed accountability focused on contextually relevant values and goals. For example, many scholars have championed more open governance forms focused on cross-boundary interdependencies such as co-creation or coproduction (formal authorities collaborating with end users and citizens in planning and managing public services and framing problems and solutions) (Ansell and Torfing Citation2021). In complex long-term place governance projects, developing contextual understandings of “meaningful accountability” offers compelling inroads into ways of rejuvenating planning’s social legitimacy and better-targeting governance changes.

Complementing this lens, Vibert (Citation2014) suggests the need for systemic approaches to accountability based on the integrity of whole systems, not singular institutions. Common political and bureaucratic discourses centre on individual institutional accountability and fragmented compliance (i.e. monitoring obligations or decision-making structures). This narrow view is often inadequate as particular actors’ behaviour is a poor proxy for wider systems, and patterns of authority and legitimacy are in constant flux. A systems lens is well suited to complex urban planning contexts; it implicates “big picture” questions of whether whole governance and political systems are working as intended to achieve social goals, considering how power, authority, and coordination flow within and through a totality of different systems and bodies. Together, these frameworks point to more relational perspectives on accountability focused on interdependencies towards shared goals, oriented to feeding back into questions of how to effectively adapt and transform systems.

Reviewing the literature on urban infrastructure governance provides a closer contextual basis for this paper's interrogation. A recent systematic literature review (Clements Citation2023) revealed accountability and transparency, which are both highly referenced themes but are typically mentioned briefly without conceptual elaboration. Discussions focus on accountability’s broad importance (Curtis and James Citation2004) or governance deficits (Wegrich and Hammerschmid Citation2017) such as reduced capacities for scrutiny in neoliberal or networked governance contexts (Estache and Fay Citation2010, Taşan-Kok et al. Citation2020, Searle and Legacy Citation2021). Few detailed cases of effective implementation (e.g. via independent authorities or coproduction) (Schwartz et al. Citation2009, Becker et al. Citation2017). Within increasingly entrepreneurial neoliberal infrastructure planning contexts, accountability is commonly identified as fragmented, reductive, and ineffective, creating market dependence at the expense of public interests. This is exemplified in the work by Taşan-Kok et al. (Citation2020, p. 2) where the sheer complexity of contractual relations and control instruments produced (such as funding and regulation) makes mapping institutional and actor relations “difficult to follow, analyse, conceptualise and evaluate”.

A central facet of public accountability is attentiveness to power. In the NSW context, scholars have detailed the multiple structural, regulatory, and political ways that planning has become dominated by state government authority; setting agendas, controlling major decisions and funding, and privileging the interests of political-economic elites (Farid Uddin and Piracha Citation2023). Limited roles for local government agencies and community participation in an antagonistic post-political environment have exacerbated spatial inequalities (Haughton and McManus Citation2019, Harris Citation2022). Scholars have recommended transforming NSW’s urban governance through more unbiased structures, transparent processes, and collaborative partnerships and participation between institutions and communities.

City Deal (CD) agreements represent recent governance experiments in Australia seeking greater institutional collaboration in planning places, the largest nationally being the Western Sydney CD adopted in 2018 between federal, state, and eight local governments (detailed below). However, scholars have criticised it for fundamentally lacking the devolved governance aspects seen in UK counterparts, such as local government funding capacities and “downwards” government accountability measures (to local communities), instead maintaining top-down power structures and an “upwards” accountability focus (to higher government levels) (Pill Citation2021, Harris Citation2022). Therefore, close attention to questions of accountability in this evolving governance experiment offers productive insights into how alternative power relationships might be forged.

3. Case Study: The WPC

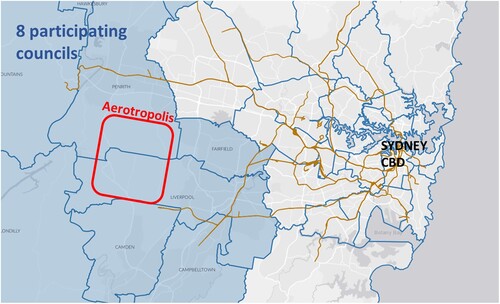

This paper focuses on interrogating social understandings of accountability from diverse stakeholders as a starting point for considering more meaningful accountability approaches. It draws on a case study exploring the early stages of infrastructure governance in the WPC; a major development project aiming at restructuring Sydney’s metropolis (). The WPC project is premised on the Greenfield development of the “Aerotropolis”, a major urban centre currently named Bradfield representing Sydney’s “Third City” being built alongside a new metropolitan airport, generating regional growth amongst adjacent established suburban centres within Western Sydney. The project’s funding through a CD agreement aimed to improve inter-government collaboration within a prevailing context of siloed planning (Pettit Citation2019, Harris Citation2022). Typically, in Australia, states fund major infrastructure and local governments are heavily resource-constrained, unable to raise taxes and often reliant on local rates. In contrast, this CD involves substantial infrastructure funding from the federal government with matching contributions at other levels, distributed among state and local governments for agreed projects to meet 38 collaboratively determined commitments, including a connecting rail line and the Planning Partnership Office to facilitate integrated planning at state and local levels (such as uniform design standards).

Figure 1. A map showing the general location of the Aerotropolis relative to the existing eastern harbour Sydney Central Business District and current rail network (thin lines branching from the CBD). The shaded areas on the left show the jurisdiction of eight local councils engaged in the CD.

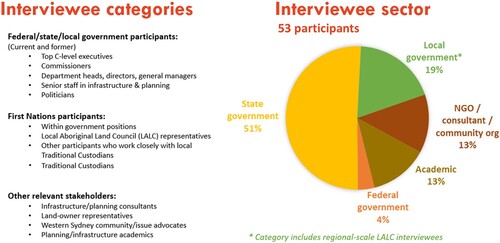

The paper’s focus on accountability is one part of the broader WPC case study research conducted by the Infrastructure Governance Incubator (involving the University of Sydney, the University of Melbourne, and Monash University), examining diverse aspects of infrastructure governance. The case research primarily involved conducting and analysing 56 semi-structured stakeholder interviews (53 distinct participants with three follow-up interviews) from late 2021 to late 2022, complemented with desktop policy and media analysis. Interviews were premised on protecting participant anonymity through mindful reporting; a pertinent aspect facilitating many interviewees with ongoing project roles to disclose personal or professional opinions. Participants were initially identified through existing project contacts and then through snowball approaches, and transcriptions of the 1-h online interviews were analysed qualitatively. shows the diversity of participant role types and the proportion of represented sectors. Questions focused on themes identified through literature review (see Clements Citation2023). Further themes emerged inductively through the analysis of responses, including the importance of accountability and the diverse and often overlapping notions offered.

4. Findings

4.1. Multiscalar Governance Structure: Unclear Responsibilities and Collaborative Forums

One of the most common issues of accountability noted by participants was related to the clarity of planning and delivery responsibilities in the multiscalar governance structure. Many expressed confusion around the roles and responsibilities of the major state organisations, such as the Greater Sydney Commission (GSC, later renamed the Greater Cities Commission) and the Western Parkland City Authority (WPCA), both now dissolved (detailed later). While potentially attributable to the new collaborative governance structure and an array of new agency relationships (challenging attribution of decisions to single agencies), there was heavy criticism of the lack of a clear governance map and ongoing confusion over the core agency remits. The WPCA was set up to attract investment and coordinate development with some master planning roles, but many saw it as too narrow for effective coordination, others noting coordination gaps not adequately covered by other organisations. Coherence gaps were noted in the overall project visioning; deeper visioning work beyond the GSC’s high-level ideas was yet to be done without clarity on who should lead it.

I don't think there is a Parklands City project … there's a Bradfield activation project, and then there's the development of the centres in the Parklands City. But they clearly don't have the governance to have a Parklands City project . . . there's a risk that there's a lack of clarity between accountability and delivery, funding, and prioritization, . . . if you can't have clarity on those things, then you can't have a framework for decision-making. (Planning consultant)

The level of autonomy local governments have to challenge the proposals or demands put forward was emphasised as critical:

If there were things that they put on the table that wouldn't work for us, we didn't feel held to ransom, it was a matter of “okay, let's have a discussion about that”. And if we need to push back . . . It wasn't a situation where you tell us to do something, and we'll just go and do it. It was actually “does it work for us?”. (Local government representative)

4.2. Accountability Through Electoral Politics: Ministerial Oversight and Political Attention

Participants expressed that the WPC and CD had experienced strong ministerial commitment and cross-portfolio collaboration in the initial stages. Nevertheless, a major concern was that the WPC ultimately lacked political accountability over time for such a long-term, speculative planning approach and could fail through the multiple elections and likely ministerial changes across the project’s horizon. After a 2022 federal party change, the incumbent Minister of Infrastructure criticised and sought to adapt the prevailing CD governance. Interviewees anticipated major changes to the project’s key authorities after the March 2023 state election, which indeed saw the GSC and WPCA both effectively dissolved by the incoming government (“folded” into the state planning department). The potential for “political backflips” and failure to deliver on commitments was emphasised as impacting the already strained levels of local community trust in systems:

If the same government stays in power for long enough, this stays real. But if they lose the next election, I think there's a real chance that the Aerotropolis shifts from being a place where people live to being an airport and a bunch of warehouses and a train line that gets people to where they live somewhere else … . (Advocacy organisation representative)

I think we make movement forward. And then the politics changes again . . . New government comes in, plan is thrown back in our faces, because we're using words like “equity” and “resilience” and “liveability”, and those words were not admissible in the new way forward . . . so you feel like you've gone three steps forward and 20 steps back. We've now come interestingly enough to a point where we probably were about 10 years ago. (Local government official)

Participant views contrasted strikingly on which planning commitments ought to be accountable and through which bureaucracy. Views diverged on the value of agency project proximity and integration capacities or political power proximity and influence capacities (i.e. to high state-level political seats such as the Premier's office). There were common concerns about high-level institutions lacking the bandwidth and capacity to prioritise oversight of particular planning matters, whether centralised political seats with broad portfolios and responsibilities across the state or major state-level planning agencies. In short, maintaining political attention was seen as critical for project accountability (to meet aims, and to survive) over time, but there was little consensus on how to achieve this. Loading so much expectation for accountability – especially regarding the massive amounts of public funding and years of planning and resourcing – within the realms of electoral politics where political attention is constantly in demand and shifting presents deep challenges.

4.3. Accountability as Effective Capacity: Resourcing and Empowering Responsibilities

Another major accountability issue emphasised was limited regulatory authority and resourcing (financial and otherwise) to deliver, particularly regarding chronic legacies of under-resourced local governments. The CD approach facilitated “seats at the table” and short-term funding for specific projects. However, by catalysing regional development growth, it exacerbated pressure on local governments that lacked the fundamental capacity to generate and use funds for general infrastructure development for existing and new communities:

The more that the [CD] commitments roll out, the more that pulls on [local government] purses … there's just not the money there. It's not they're trying to be difficult. They just can't do it. So that's where I get a little bit frustrated because state and federal government, at the end of the day, really have MUCH deeper pockets and the ability to MAKE money by increasing taxes or changing laws in a way that we cannot. (Local government official)

There's ALL these implications for council in terms of work safety, in terms of actually implementing that project, in terms of the ongoing asset, because there's no op-ex being provided. So then it's like, “who's paying for this?” . . . None of those questions were really dealt with . . . Nine times out of ten, it's council, but there's been no real consideration of that. (Local government representative)

4.4. Accountability Through Independent Oversight

The WPC involves various institutions providing degrees of independent input, such as Infrastructure Australia and Infrastructure NSW; organisations with formal, legislated roles providing advice to the government and producing reports, funding audits and priority lists. While based within the GSC and not fully independent, various GSC commissioner roles were created at the project’s outset to provide forms of public accountability regarding important issues (such as the Environmental Commissioner) and to specific districts (such as the Western Sydney Commissioner). While opinions were mixed, interviewees generally viewed the commissioner roles positively; as providing useful influence and social legitimacy when highly engaged with projects and collaborative forums (such as acting as strong advocates for district councils or in shaping planning themes). Commissioners themselves also shared highly mixed experiences of the utility and autonomy of their roles. Several were praised for their work in supporting collaborative governance. Others had wanted to substantially challenge processes or express stronger critique, detailing major points of dissatisfaction with top-down constraints put upon the roles, particularly in the earlier GSC period. Some resultingly left their commissioner positions, citing failed expectations for autonomy or institutional acceptance of creative input into governance and policy goals.

I had expected the Commissioners to be much more outspoken than they are. I don't actually fully understand why that is, because for a lot of them, it's a part time gig, they're experienced professionals in their own right . . . I think there is an extent to which this can't be done by public servants. (ex-GSC Commissioner)

I didn't bother applying for the future going ahead with it. I found it an extremely frustrating organization to work with. Some really good people. But I just felt that they missed what was, in my view, a phenomenal opportunity to really do something . . . But the reality was just not that. I'm not entirely sure why. But we seemed to be constrained in what we could actually do. (ex-GSC Commissioner)

If some of the things [the commissioner] suggested didn't happen, the whole policy would fall over. Because it doesn't have the social license. [The commissioner] saved it from completely hitting the wall because the media would have been so terrible in the run up to an election, that the whole policy would have gone down . . . There's a lot to be said for an independent person who can [escalate issues to political levels]. (Government official)

It ended up very ugly at the end where [the state government] wanted to change the report, and there was a whole, “No, you can’t change what people have seen” . . . you can’t have an independent evaluation if it’s not going to be independent. . . The report remained the way we finalized it. But there were a lot of difficult meetings about that. (Government official)

The only way you can do this work is not care about your career . . . you see in the appointment of GSC commissioners, they're often people who are in the later stages of their career. . . It's not a job you can do without [critiquing people] and pointing out the failure of the systems that they're part of, and their perspectives. (State government official)

4.5. Structural Constraints on Personal Accountability

While references to personal and professional senses of responsibility were made by several interviewees, the expression of a strong sense of cultural accountability was prevalent amongst First Nations participants. In these discussions, project ambitions and personal commitments were often framed in relation to supporting a broader politics of Indigenous sovereignties, rights, equity, well-being, and power. Such political and cultural accountabilities were sometimes represented through references to existing personal and community relationships. Where circumstances and resources allowed, these connections and commitments drove approaches to building strong accountability structures within institutions, such as the Aboriginal Land Councils, Traditional Custodian land management groups, and Aboriginal-led planning programmes (e.g. the Roads to Home programme facilitating Indigenous-led infrastructure governance). Conversely, such high political and cultural stakes could be overwhelming when clashing with systemic limitations or resistance and result in deep moral tensions:

Trying to balance your own moral and political standing with not missing out on opportunities, it's gonna be difficult for some people, I think. . . I had to do a lot of thinking around, “have I gone to the dark side?” (Aboriginal participant)

I really am using my platform here . . . to elevate my community and the members within my community to make sure that they're getting a fair go, and also to just break the cycle in some cases. (Aboriginal participant)

Everyone is so busy at all times, that it's very hard to have a self-check on your visibility and accountability for things just because you literally get into just the day-to-day . . . Some people have a core role, but only a few. Other people have day-to-day roles, and this becomes a secondary thing for them . . . I think that's for the majority of people. And that affects accountability. (State government representative)

I think the weakness in strategic planning is you'll have a group of people who do a plan. And when it's finished, they'll just be disbanded and go to other jobs. And then five years later, you say “we're re-doing the plan”. But everyone who's involved is gone. (State government representative)

If I did get promoted, then I wonder how much time I would still have to maintain those relationships . . . (Aboriginal participant)

4.6. Social Legitimacy Through Public Discussions of Stakes and Hard Truths

Government willingness to openly address political planning challenges was viewed as a critical element of project accountability. Many expressed that developing meaningful social legitimacy (let alone equitable and effective infrastructure delivery) in the WPC project will require honest conversations with communities and stakeholders regarding politically challenging issues core to achieving goals. Issues included addressing the roots of socioeconomic disadvantage in Western Sydney, truth-telling about the permutations of settler-coloniality in infrastructure development, the outsized political influence of the NSW development industry, and the need to explore politically unpopular options for generating infrastructure funding such as taxation and development contributions reform. Yet, interviewees often struggled to imagine any formal actor with such political willingness, acknowledging this vacuum can lead to political evasion of problems or plan abandonment:

There's not always political appetite to do that, there's . . . at times a preference to either stay silent on that or to abandon the implementation and the upkeep of plans, because of the some of the hard truths associated with it. (State government official)

It can be often tempting to want to hide your dirty laundry, if you like, or try and make sure you've got all your ducks in a row before you say anything publicly. But that works against actually collaborating in a really honest fashion, because you often need to know “what's the problem?” Or “what are the obstacles?” to be able to then help. But if they're trying to work it all out before they say anything, then nothing ever moves forward. So, I think all three levels of government are guilty of doing that. (Local government official)

4.7. Transparency and Openness: Withholding Key Publications and Community Legibility

Transparency was strongly positioned by participants as key to public accountability including through publication of key documents such as infrastructure business cases or governance reviews. While various agencies publish a wide range of plans and reports online, several major reports have not been publicly released. Participants often expressed the need for greater government commitment to continuous publication and public dialogue:

Accountability and transparency is actually to publish, and is to be upfront . . . be transparent about the way in which you go through that process . . . about what it would cost, what the funding shortfall is, who pays for what, and to publish that . . . Then the most essential thing, which is often where systems get disrupted because of the nature of political cycles, and so on . . . is to refresh and to have a continuous programmatic dialogue, openly and transparently. It's not good enough to publish static plans anymore. (State government official)

The reason it hasn't been released is it made some pretty strong recommendations that I don't think the state government's prepared to respond to. So, I think it's going to be a watered-down version. (Former state government official)

I think that's a big issue that the full report should be made public, that the recommendations should be made public, and then the three levels of government are held to account to deliver on those recommendations, because how else do you see change happen than that way? So, I would hope that that happens in the future, because I think it was quite independent and pragmatic, the advice that is given in the recommendations. (Local government official)

And where's the business case? … Where's the business case? Find the business case. (State government official)

My personal view is that the more transparent you are, the more accountable you are … we should be publishing our business cases, the strategic planning work that has underpinned those, and the evidence that has afforded those and we've got a long way to go. (Senior state government official)

I think every study and everything they should do should be in the public domain. I think that there's no excuse to say it's commercial-in-confidence . . . I don't know how you'd make it more transparent, because with these big dollops of money like an airport and the metro, those business cases are very tightly held . . . the most region plans can do is have a structure logical enough that you can see where the infrastructure needs to be. (State government official)

4.8. Weak Links with Non-Government Stakeholders: Planning Without Community

There were widespread participant views that both community infrastructure and service organisations and the general public were not meaningfully engaged or involved in the governance of the project to date. Some questioned whether the focus on getting the multigovernment collaboration right had come at a cost of neglecting community representation and voices:

There was a view that [WPCA] was so focused on three levels of government coming together, there wasn't a mechanism for the way that you could have community representation. And then when you think about the way businesses operate, even state-owned corporations, they have a customer Council, or they have a community representative, or they have a community reference group, and I think that voice along with a voice of business is an improvement that could be made in the governance arrangements that go forward. And somehow, measuring people's perceptions and on a regular basis, and it's an important feedback loop in terms of, “are we achieving on the outcomes?” We don't take the voice of the community and business with us. (Former state government official)

I don't think there is a democratic nexus around planning in Sydney anymore. I think it's as severe as that. I think the mechanisms of accountability have actually broken down. (Planning consultant)

Where these infrastructure projects get decided, [community are] often a missing part of the conversation, then brought in too late when things have been decided, and things are almost underway. (Local government official)

I think that they've been convinced the only function that community serves is to stop development, and so therefore, since development is good, we must stop the community. So to be honest, I think it's still a failed area of discussion, because I still believe that if you involve people in the strategy for your area, then you're much likely to get a better result (Planning consultant)

5. Discussion

The case study reveals a complex landscape of shifting approaches to, and claims for, accountability within the context of governance changes and ambitions entangled with prevailing structures and forces. In a large-scale, long-term project with multiple frontiers of planning and development and a vast array of actors and stakeholders (and stakes) diverse understandings of accountability arise as relevant, including institutional openness and transparency, clear and ongoing communication, social legitimacy and community engagement, governance coherence, and the capacity for effective implementation. Many understandings intersect across lines of decision-making and steering power, group or issue-based representation, processes of planning and monitoring, and matching responsibility to capacity (e.g. authority and resourcing).

This work emphasises that accountability is a critical challenge for contemporary complex urban governance projects that require a much deeper and more pointed focus in infrastructure governance research given the prevailing neoliberal, and post-political planning contexts, fractured social trust in public planning, and complex pressures to realise major social goals such as sustainability and equity. This research reinforces existing scholarly work (Pill Citation2021, Harris Citation2022, Farid Uddin and Piracha Citation2023) detailing the ways in which NSW’s prevailing power dynamics (top-down, state centralised planning) remained relatively unchallenged by the structural, project-based limitations of the Western Sydney CD, with even long-term regional equity outcomes questionable given the major political changes to the WPC. Through interrogating contextual understandings of accountability challenges, we contribute to a normative research agenda asking what meaningful accountability might encompass (and look like) in contemporary infrastructure planning. We lastly focus on three important insights: building foundations for trust and embracing relational and systemic approaches to accountabilities.

5.1. Collaboratively Building Foundations for Trust

Prevailing trust (and trustworthiness) issues permeate all aspects of this project – within and between institutions, and with wider publics and communities – with significant impacts on its social legitimacy and enabling political environment. Some issues concern local- or project-level governance, but others relate to diverse historical and systemic legacies at play, such as entrenched post-political infrastructure planning in NSW (Haughton and McManus Citation2019), institutional competition for funding, or Indigenous struggles against settler-coloniality. Establishing more collaborative inter-government structures such as the CD has represented welcome steps forward; however, stakeholder concerns demonstrate that changes have not yet been as extensive or systemic as necessary to address deep legacies of mistrust at play, risking project failure on multiple fronts.

We argue that effective collaborative governance relies on actors working proactively to rebuild foundations of trust between parties and communities. This rebuilding requires the centring of public accountability approaches in the principles guiding planning and, vitally, into the actual planning, procurement, and delivery processes of projects. Rethinking accountability and employing instruments and approaches that secure it in practice could help address current governance contradictions. This is, of course, a challenging task given the post-political context of NSW planning, where there are deep power imbalances across the infrastructure and planning system, which is designed to avert many government elements to transparency, openness, and potential project risks, with the view to minimise community-led challenges that could present risks to a project’s overall delivery. Critical dialogues on accountability approaches likely need to be driven outside of government and by independent actors. However, the findings also reveal that there is a substantial appetite among many in diverse government positions to engage in such discussions and embrace publicly open practices, in addition to the demonstrated interest in building collaborative governance from key WPC actors. Reform attention must acknowledge ongoing legacies of mistrust at play and explicitly centre commitments to accountability approaches in upfront and ongoing governance structures and principles.

This research has also demonstrated that an important foundation for thinking through more meaningful accountability approaches is identifying social understandings of what accountability does and could mean to diverse actors and communities involved or affected, and how they evolve over time. This is almost certainly best initiated by independent actors as it not only requires broad identification of key stakeholders (within and outside of government) but also provides anonymous or “safe” forums for honest opinions, even from those currently involved or embedded within project organisations. We suggest that accountability issues and goals should be (at least in part) contextually developed, reviewed, and adapted, reflecting the understandings, priorities, relationships, and experiences of diverse stakeholders – ideally forged collaboratively, inviting key groups into governance design. The three-year CD review exemplifies both a strong reflective process centring partner experiences and understandings in governance adaptation, and a concerning example of governments withholding critical, but perhaps uncomfortable, information from the publics. Seeking ways to collaboratively define accountability challenges and reshape approaches raises a multitude of questions for urban governance researchers and practitioners, but our research suggests that there is critical importance and wide interest in seriously tackling these challenges.

5.2. Relational Approaches to Building Accountability

Building on the previous point, this case points to the importance of more relational understandings of, and approaches to, building accountabilities. The WPC case illustrates aspects of at least partially successful relationships being built between government levels, particularly with local governments securing greater governance roles and through new forums and alliances, amassing enough power and voice to strategically re-negotiate terms. A critical task in the WPC and other major NSW projects is how similar collaborations might be fostered with non-government partners, community infrastructure providers, wider public and local communities, and First Nations groups such as Traditional Custodians. To expand collaborative governance beyond government and traditional infrastructure agencies like this, accountability approaches cannot be singular, rigid, viewed as objective or universal, de-contextualised, or top-down. The complexity of collaborative place governance requires acknowledging and giving attention to the importance of building new and sustaining new relationships and partnerships; accountability frameworks are negotiated at the outset and over time between new groups and communities in ways that directly address the deeply challenging issues that complex infrastructure planning typically attracts. In other words, accountability is dynamically cultivated through deliberations with all stakeholders and communities alike.

Fostering more relational approaches to generating accountability beyond traditional top-down, government-centred, or regulatory forms raises highly challenging questions for research and policy. In this case, state and federal governments would be confronted with demands for power sharing and challenges to change status quo processes (such as decision-making) in what is widely acknowledged to be a risk-averse, and often antagonistic governance environment (see Legacy et al. Citation2017); characteristics of post-political infrastructural planning in NSW (Haughton and McManus Citation2019, Harris Citation2022). Furthermore, researchers and policy makers must attend to the challenging structural realities outlined in this research, including staffing and communication issues that confound even basic community attempts to engage with government agencies over time.

5.3. Systemic Approaches to Understanding Accountabilities

This research demonstrates that a systemic perspective of accountability is an important lens for understanding the interconnections and overlaps between diverse areas of concern, need, responsibility, and capacity. Returning to Vibert’s (Citation2014) conceptual framework focused on approaches in accountability research; in this paper, we established the suitability of applying this lens to complex urban infrastructure and planning projects, where so many dimensions of accountability intersect throughout and beyond project boundaries, including flows of power and knowledge, evolving patterns of authority and influence, and spatial and place dynamics. A system lens facilitates recognition of interconnected accountability issues across traditional project and institutional boundaries and scope, enabling the identification of broader systemic integrity regarding how planning and infrastructure systems are working to meet societal ambitions. While infrastructure governance literature commonly discusses accountability in terms of institutional contexts (Wegrich and Hammerschmid Citation2017) or transparency to the general publics (Becker et al. Citation2017), it is less common to consider accountability at a broad systems level. Beyond critique or identification of problems, a systemic accountability lens may also give weight to systems-level solutions, such as suggestions to systematise successful aspects of new collaborative governance experiments such as City Deals beyond projects or help build political momentum towards transforming chronic (but politically challenging) planning issues such as local government funding capacities.

6. Conclusion

Through interviews with key multiscalar institutional stakeholders in a major place-based infrastructure project, this research has revealed a wide range of intersecting aspects of accountability. In seeking approaches to meaningful accountability in major collaborative governance infrastructure projects, we suggest that accountability should be seen through a systems lens to better understand the wide array of interconnecting issues and stakes. Additionally, given the deep contextual legacies of mistrust and the evolving complexities of place transformation, understandings of and approaches to accountability must be overtly and collaboratively forged, with more attention given to relational aspects of building collaborative governance with diverse groups, beyond government. Through these focuses, this research aims to contribute to renewed attention in infrastructure governance research towards the nature of building accountability in public-sector governance formations.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Amin, A., 2011. Urban planning in an uncertain world. In: Gary Bridge and Sophie Watson, eds. The New Blackwell companion to the city. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 631–642. doi:10.1002/9781444395105.ch55.

- Ansell, C., and Torfing, J., 2021. Public governance as co-creation: a strategy for revitalizing the public sector and rejuvenating democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Becker, S., Naumann, M., and Moss, T., 2017. Between coproduction and commons: understanding initiatives to reclaim urban energy provision in Berlin and Hamburg. Urban research & practice, 10 (1), 63–85.

- Bovens, M., and Schillemans, T., 2014b. Meaningful accountability. In: M. Bovens, R. E. Goodin, and T. Schillemans, eds. The Oxford handbook of public accountability. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 673–682.

- Bovens, M., Schillemans, T., and Goodin, R.E., 2014a. Public accountability. In: M. Bovens, R. E. Goodin, and T. Schillemans, eds. The Oxford handbook of public accountability. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1–20.

- Cheyne, C., 2015. Changing urban governance in New Zealand: public participation and democratic legitimacy in local authority planning and decision-making 1989–2014. Urban policy and research, 33 (4), 416–432. doi:10.1080/08111146.2014.994740.

- Clements, R., et al., 2023. A systematic literature review of infrastructure governance: cross-sectoral lessons for transformative governance approaches. Journal of planning literature, 38 (1), 70–87. doi:10.1177/08854122221112317.

- Curtin, D., and Meijer, A.J., 2006. Does transparency strengthen legitimacy? Information polity, 11 (2), 109–122.

- Curtis, C., and James, B., 2004. An institutional model for land use and transport integration. Urban policy and research, 22 (3), 277–297. doi:10.1080/0811114042000269308.

- Denham, T., and Dodson, J. 2018, December. Cost benefit analysis: the state of the art in Australia. In Australian Transport Research Forum (ATRF).

- Estache, A., and Fay, M., 2010. Current debates on infrastructure policy. In: Michael Spence and Danny Leipziger, eds. Globalization and growth implications for a post-crisis world. Washington, DC: World Bank, 151–193.

- Farid Uddin, K., and Piracha, A., 2023. Urban planning as a game of power: the case of New South Wales (NSW), Australia. Habitat international, 133, 102751. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2023.102751.

- Fenster, M., 2006. The opacity of transparency. Iowa law review, 91 (3), 885–950.

- Harris, P., et al., 2022. City deals and health equity in Sydney, Australia. Health & place, 73, 102711. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2021.102711.

- Haughton, G., and McManus, P., 2019. Participation in postpolitical times: protesting westconnex in Sydney, Australia. Journal of the American planning association, 85 (3), 321–334.

- Hodge, G.A., and Coghill, K., 2007. Accountability in the privatized state. Governance, 20 (4), 675–702. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0491.2007.00377.x.

- Hunter Research Foundation Centre. 2021, 27 August. Independent community commissioner report. Available from: https://www.hrf.com.au/news-events/news/independent-community-commissioner-report [Accessed 20 February].

- Legacy, C., Curtis, C., and Scheurer, J., 2017. Planning transport infrastructure: examining the politics of transport planning in Melbourne, Sydney and Perth. Urban policy and research, 35 (1), 44–60.

- Meijer, A., 2014. Transparency. In: M. Bovens, R. E. Goodin, and T. Schillemans, eds. The Oxford handbook of public accountability. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 507–524.

- Moore, M.H., 2014. Accountability, legitimacy, and the court of public opinion. In: M. Bovens, R. E. Goodin, and T. Schillemans, eds. The Oxford handbook of public accountability. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 632–646. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199641253.013.0024.

- Papadopoulos, Y., 2016. Accountability. In: C. Ansell, and J. Torfing, eds. Handbook on theories of governance. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing, 215–225.

- Pettit, C.J., et al., 2019. Breaking down the silos through geodesign – envisioning Sydney’s urban future. Environment and planning B: urban analytics and city science, 46 (8), 1387–1404. doi:10.1177/2399808318812887.

- Pill, M., 2021. Governing cities: politics and policy. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Romzek, B.S., 2014. Accountable public services. In: M. Bovens, R. E. Goodin, and T. Schillemans, eds. The Oxford handbook of public accountability. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 307–323.

- Schedler, A., 1999. Conceptualizing accountability. In: A. Schedler, L. Diamond, and M. F. Plattner, eds. The self-restraining state: power and accountability in new democracies. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 11–28.

- Scholtes, H.H.M., 2012. Transparantie, icoon van een dolende overheid. The Netherlands: Boom Lemma Den Haag.

- Schwartz, J.Z., Andres, L.A., and Dragoiu, G., 2009. Crisis in Latin America: infrastructure investment, employment and the expectations of stimulus. Journal of infrastructure development, 1 (2), 111–131. doi:10.1177/09749306090010.

- Searle, G., and Legacy, C., 2021. Locating the public interest in mega infrastructure planning: the case of Sydney’s West Connex. Urban studies, 58 (4), 826–844. doi:10.1177/0042098020927835.

- Siemiatycki, M., 2009. Delivering transportation infrastructure through public-private partnerships: planning concerns. Journal of the American planning association, 76 (1), 43–58. doi:10.1080/01944360903329295.

- Taşan-Kok, T., Atkinson, R., and Martins, M.L.R., 2020. Hybrid contractual landscapes of governance: generation of fragmented regimes of public accountability through urban regeneration. Environment and planning C: politics and space, 39 (2), 371–392. doi:10.1177/2399654420932577.

- Tetlock, P.E., 1992. The impact of accountability on judgment and choice: toward a social contingency model. In: Mark Zanna and James Olson, eds. Advances in experimental social psychology. Burlingon: Elsevier, 331–376.

- Vibert, F., 2014. The need for a systemic approach. In: M. Bovens, R. E. Goodin, and T. Schillemans, eds. The Oxford handbook of public accountability. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 655–660.

- Wegrich, K., and Hammerschmid, G., 2017. Infrastructure governance as political choice. In: Kai Wegrich, Genia Kostka, and Gerhard Hammerschmid, eds. The governance of infrastructure. First Edition Oxford: Oxford University Press, 21–42.