Abstract

Objective

Rotation work involves travelling to work in remote areas for a block of time and alternate with spending another block of time at home; such work arrangements have become common in the resources sector. The intermittent absence of workers from the home may adversely affect the health of the workers’ families. This study synthesises research on mental and physical health outcomes in partners and children of rotation workers in the resources sector.

Design

A systematic review was conducted. Studies were retrieved from PubMed, Medline, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Scopus. Nineteen studies were included and findings were summarised narratively.

Results

The impact of rotation work on the mental health and well-being of partners and children of rotation workers remains unclear. However, on days where workers are away, partners may experience greater loneliness and poorer sleep quality.

Conclusion

Partners may benefit from support, particularly when they have younger children and/or their spouses first begin rotation work. Research is limited, particularly regarding the impact on health-related behaviours and physical health outcomes.

Registration

This review was registered on PROSPERO (ID: CRD42020167649).

Introduction

Definition of rotation work and the impact on families

Rotation work, also known as Fly-In Fly-Out (FIFO) (Storey, Citation2016), involves travelling to work for a typical 12 hour day or night shift and staying for a specified number of days, ranging from 5 days to 6 weeks, after which the worker returns home to spend another specified period at home (Meredith et al., Citation2014; Storey, Citation2016). Rotation work arrangements initially developed for serving offshore oil and gas installations in the Gulf of Mexico, are nowadays increasingly used globally in the onshore mining and construction industry (Storey, Citation2016).

Rotation work arrangements present families with benefits including higher incomes, the maintenance of social networks and urban settlements, and chance to spend blocks of time with family and friends during leave periods (Gallegos, Citation2006). However, the rotation work lifestyle of alternating presence and absence from home over some time also has disadvantages for social and family life, and workers’ wellbeing. These include workers missing family and social events (Langdon et al., Citation2016), potentially overburdening partners with their home obligations (Gallegos, Citation2006; Langdon et al., Citation2016), and recurrently having to emotionally and functionally adjust to separations and reunions (Gallegos, Citation2006; Meredith et al., Citation2014) often leading to disruption of family lives (Parker et al., Citation2018).

A literature review suggested that the partners experience more stress, social isolation and loneliness, and that the absence of the worker could negatively impact children’s development, wellbeing and family functioning (Parker et al., Citation2018). Another review reported that children of rotation workers may experience more adverse emotions including anger, sadness, and hate; and more behavioural problems such as hyperactivity, conduct and peer problems due to the long absence of rotation work parent from the home (Meredith et al., Citation2014).

Theoretical frameworks

Little effort has been made to consider the effects of rotation work on families within the available theories and frameworks (Dittman, Citation2018; Parker et al., Citation2018). Both Work-Family Conflict Theory (Greenhaus & Beutell, Citation1985) and the Spillover-Crossover Model (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2013) could explain how the pressures of rotation work demands impact the wellbeing of partners and children of workers. Studies have employed the aforementioned theories to explain in what ways the pressures of job demands and resources of spouses who both earn income influence the wellbeing of their partners (Shimazu et al., Citation2009) and children (Shimazu et al., Citation2020).

Furthermore, Attachment Theory (Bowlby, Citation1980) and Social Ecological Theory (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1994) could offer the means to understand potential effects on partners and children of temporary separations due to rotation work. Studies acknowledge the significance of Attachment Theory (Diamond et al., Citation2008; Medway et al., Citation1995) and Social Ecological Theory (Dittman, Citation2018; Orthner & Rose, Citation2009) in explaining the effects of temporary parental and partner separations; for instance, due to military deployment on children and partners’ wellbeing (Orthner & Rose, Citation2009). Full descriptions of frameworks are presented in supplementary Appendix 1.

Aim of the present study

Rotation work in relation to family life differ from other work arrangements. The intermittent absence of workers from the home may adversely affect the health of the families of workers. As rotation work becomes more popular globally, it is necessary to explore the impact of this work on the health and wellbeing of workers and their families. We conducted a systematic review of studies examining the impact of rotation work on the health and wellbeing of workers’ partners and children, including psychological health and well-being, physical health, sleep and health-related behavioural patterns, and emotional and behavioural patterns of children. Providing a comprehensive review in global resource and related construction sectors could provide clarity and highlight the consequences of rotation work arrangement on families.

Methods

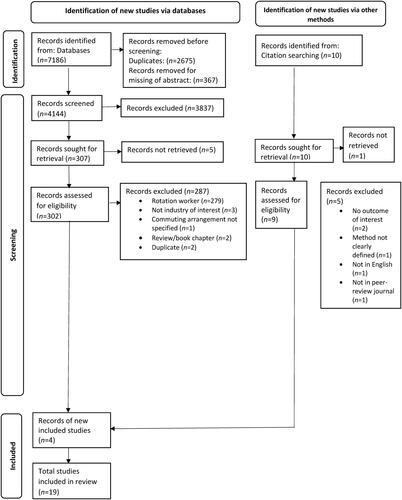

This systematic review of the literature was conducted in line with Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) for quantitative and qualitative reviews guidelines (Lizarondo et al., Citation2020), and reported in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., Citation2020). This review was part of a broader review of which the protocol was pre-registered on PROSPERO (ID: CRD42020167649) assessing the overall mental and physical health of rotation workers, reported elsewhere (Asare et al., Citation2021).

Eligibility criteria

Original articles of quantitative, qualitative and/or mixed-method studies published in peer-reviewed journals and English were included. Qualitative findings can give in-depth insights into the health outcomes of rotation workers’ partners and children, and support the understanding of quantitative findings. The study population were partners (with or without children) and/or children (of any age) of rotation workers who worked in the resource (offshore oil and gas, and mining) and related construction industry. Rotation workers were defined as workers who work on rotational schedules of travelling away from home to work for a block of time and alternate with spending another block of time at home. Quantitative studies were included, if they reported psychological health outcomes, children’s behavioural and emotional problems, physical health outcomes, sleep problems or health-related behaviours. Qualitative studies that reported the perceptions of the impact of rotation work arrangement on the physical and mental wellbeing of partners and children of rotation workers were included. We also included studies that reported parents’ perceptions about the impact of rotation work on children. The clearly defined quantitative and qualitative components of mixed-method studies were included. Studies were excluded if they were reviews, letters, book chapters, study designs were not clearly defined, and only reported on family relationships and functioning, and parenting (but not on any health-related outcomes).

Data sources and search procedure

Searches were conducted in PubMed, Medline, EMBASE, CINAHL with Full Text, PsycINFO, and Scopus on 1st May 2020 for relevant articles as part of a bigger review (Asare et al., Citation2021) and updated on 21st April 2021, using search strategies presented in Supplement Appendix 2. Searches were not restricted by study design, publication dates and geographic location. The references of the included studies were also hand searched.

Study screening and selection

shows the PRISMA flow diagram for the selection of studies into the review. Studies identified were screened for inclusion/exclusion in the Covidence software. The titles and abstracts of articles and then full texts for all potentially eligible studies were retrieved and screened by two of the authors (BYAA and DK) for suitability. The agreement between raters (interrater reliability) for screening of studies at both the title and abstract, and full text stages were high with a Cohen’s Kappa statistic of 0.98 and 0.92 respectively. Disagreements at all stages of the screening were resolved through discussion until consensus between the two authors (BYAA and DK) and any that could not be agreed were referred to the other two authors (DP and SR) to resolve by consensus. Articles excluded at the full-text screening were recorded and the reasons that informed the exclusion of studies per the inclusion criteria reported ().

Assessment of methodological quality

Two of the authors (BYAA and DK) independently evaluated included studies for methodological quality using tools for appraisal of quantitative descriptive studies in the Meta-Analysis of Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI-MASt ARI) and Qualitative Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI-QARI) (Lockwood et al., Citation2015; Moola et al., Citation2017), and rating discrepancies were deliberated on and resolved. Checklist items of the assessment tools were rated and scored ‘Yes’ (1), ‘No’ (0) and ‘Not clear’ (0), excluding not applicable items. Analytical cross-sectional and cohort studies were rated for methodological quality on 9 to 11 items such as the validity and reliability of exposure and outcome measurements, identifying and stating strategies to dealing with confounding factors, and appropriateness of statistical analysis used (Moola et al., Citation2017) with possible scores between 0 and 11.

Qualitative studies were rated for methodological quality on 10 items such as research methodology agreement with data collection methods used, the representation and analysis of data, and the interpretation of results, and the ample representation of participants and their voices (Lockwood et al., Citation2015) and a study potentially scored between 0 and 10.

For mixed-method studies, each component of the method (quantitative and qualitative) was assessed separately as outlined above. Any inconsistencies in scores that arose were discussed and resolved through consensus. Studies scoring ≥ 7 were categorised as of high quality, scores 4–6 considered medium quality and scores <4 classified low quality and reported in the review. No study was excluded based on quality assessment (Duran, Citation2013; Lucas et al., Citation2007) since there are few available studies examining the outcomes of interest (Duran, Citation2013), and that strict exclusion based on quality assessment may exclude appropriate studies based on not following a particular reporting standard (Lucas et al., Citation2007).

Data extraction

Using the templates from the JBI-MAStARI data extraction tool for quantitative data and JBI-QARI for the qualitative studies, a data extraction sheet was developed and piloted. The key information extracted included study authors, publication year, study design, aims/objectives, study setting (country and industry) and participants (number of study participants, gender, age), health outcomes and measurement tools used and the key findings. One reviewer (BYAA) conducted the data extraction and another reviewer (DK) double-checked 10% of the extracted data; all inconsistencies were discussed and resolved through consensus.

Strategy for data synthesis and analysis

Quantitative and qualitative data extracted in terms of the studies characteristics and key findings were presented in tables and a narrative summary of the included studies done. Based on previous literature (Langdon et al., Citation2016; Meredith et al., Citation2014; Parker et al., Citation2018) studies were categorized into four main themes: psychological health outcomes, physical health outcomes, sleep, and ‘lifestyle’ behaviours. Studies were narratively reviewed within these themes, and based on study findings were further organised into subthemes. A quantitative summary of the study outcomes (meta-analysis) was not feasible due to the largely descriptive nature of studies that did not provide comparable quantitative data and the high heterogeneity of included studies and study outcomes. The effect sizes where available and further statistical details were extracted and are presented in .

Table 1. Summary of studies characteristics and quantitative findings for partners.

Table 2. Summary of studies characteristics and qualitative findings for partners.

Table 3. Summary of studies characteristics and quantitative findings for children.

Table 4. Summary of studies characteristics and qualitative findings for children.

Results

Characteristics of studies

A total of 19 studies, (9 quantitative, 7 qualitative and 3 mixed-method studies) were included in the review. Twelve studies examined outcome data among partners; all 12 studies (5 quantitative, 5 qualitative and 2 mixed-method studies) examined psychological health and wellbeing, 3 quantitative studies investigated sleep, 3 quantitative studies assessed perceived physical health status, and 4 quantitative studies examined health-related behaviours. The majority of the partners in the sample were female (average 99.38%). The age of partners ranged between 18 and 59 years (mean age 35.87 years).

Ten studies investigated outcomes data among children; seven of the studies (4 quantitative and 3 qualitative) investigated children’s psychological health and wellbeing and seven studies (4 quantitative and 3 qualitative) examined children’s behavioural and emotional outcomes. Five studies (3 quantitative and 2 qualitative) included data from parents rating the behavioural and emotional impact of partners’ rotation work on children. The summaries of study characteristics and key findings are presented in .

Out of the 11 quantitative studies (including 2 quantitative clearly defined components of mixed-method studies), seven were rated as high quality, 1 medium, and 3 low. Of the 9 qualitative studies (including 2 qualitative clearly defined components of mixed-method studies), 4 were rated high quality, 4 medium and 1 rated low (see ).

Overall, the majority of studies (84.2%) were of medium to high methodological quality. Almost all of the quantitative studies used and reported common validated scales/scoring for measuring outcomes and showed psychometric analysis of the validity and reliability of scales or pointed to original or previous studies where the validity and reliability of scales had been confirmed. Nine (47.4%) out of the nineteen included studies received external funding; 3 from university/research institutions, 2 each from a governmental agency and non-for-profit organization and industry regulator, but were not involved in the study designs and processes (see ).

Psychological health and wellbeing of partners

Psychological distress and wellbeing

Studies’ findings on partners’ psychological distress compared to the general population were mixed. Two cross-sectional studies used validated scales to examine the prevalence of distress symptoms (Lester et al., Citation2015; Taylor et al., Citation1985). One of the studies reported a higher prevalence of psychological distress (32.0% vs 2.6%) among partners of on-shore rotation workers compared to secondary data source of the general population (Lester et al., Citation2015). Whilst the other study reported comparable proportions of partners of offshore rotation workers to other married women in the general population from a secondary data source (18% vs 16%) showed ‘nervy’, ‘tension’ and ‘depressed’ symptoms (Taylor et al., Citation1985). Two other cross-sectional studies examined the levels of distress using symptoms checklist scores, recruiting comparison groups. One of the studies showed significantly higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress among partners of rotation workers compared to partners of non-rotation workers (Dittman et al., Citation2016) whereas the other study found no significant differences in levels of depression, anxiety, and stress between partners of rotation workers and partners of non-rotation workers (Cooke et al., Citation2019).

Quantitative evidence was not clear on partners’ experience of psychological distress, depression and anxiety in the absence of their partner. Out of three studies, two cross-sectional studies using symptoms checklist scores on validated scale reported higher levels of anxiety among partners in the absence of rotation workers than when at home (Morrice et al., Citation1985; Taylor et al., Citation1985): in one study, 10% were classified as having ‘Intermittent Husband Syndrome’ characterised by changes in mood and behaviour in the partner in the absence of workers (Morrice et al., Citation1985). One other daily study using self-reported diagnosis of mental health problems reported the daily use of medications for mental health problems among partners was not common; and the finding was not significantly different in the absence and presence of rotation workers (Rebar et al., Citation2018).

Quantitative evidence show partners can experience loneliness in the absence of rotation workers. One cross-sectional study examined the levels of social isolation and/or loneliness among partners using symptom checklist scores on a validated scale and reported significantly higher loneliness in the absence of workers than in the presence of workers and when compared to the general population (Wilson et al., Citation2020). Another cross-sectional study using self-reported measure on validated scale reported high proportion of partners (66.4%) indicating loneliness in the absence of workers (Parkes et al., Citation2005).

Qualitative studies emphasise the enhanced emotional strain, anxiety, and burden felt among partners in the absence of workers. The burden highlighted was generally around having to bring up children and do domestic chores alone (Gardner et al., Citation2018; Morrice et al., Citation1985; Parkes et al., Citation2005; Whalen & Schmidt, Citation2016). Partners also reported feeling anxious and frustrated about workers’ physical and psychological health (Gardner et al., Citation2018; Parkes et al., Citation2005), safety (Parkes et al., Citation2005), job insecurity (Parkes et al., Citation2005; Whalen & Schmidt, Citation2016), infidelity (Silva-Segovia & Salinas-Meruane, Citation2016), and long roster patterns (Pini & Mayes, Citation2012) particularly whilst workers were away on rotation.

Again, partners reported feeling anxious about the physical and psychological distance created by rotation work arrangement, which leads to disconnect and tension in relationships (Gardner et al., Citation2018), and were frustrated by poor communication network with partners when at work (Pini & Mayes, Citation2012). There was also evidence to suggest high anxiety among partners who are new to the rotation work lifestyle about becoming too independent as they cope with the rotation work lifestyle (Pini & Mayes, Citation2012).

Qualitative evidence showed partners of rotation workers also indicated experiencing emotions of sadness, loneliness and hopelessness when rotation workers are away from home (Mayes, Citation2020; Morrice et al., Citation1985; Parkes et al., Citation2005; Pini & Mayes, Citation2012; Whalen & Schmidt, Citation2016), and that tended to be magnified in partners with younger children (Pini & Mayes, Citation2012). Partners reported the lack of sympathy from community members and even other FIFO families, and lack of support from organizations toward negotiating the health of FIFO families (Gardner et al., Citation2018).

Evidence also showed partners experience emotional strains and distress during reunions and prior to separations. Four qualitative studies discussed partners are faced with the difficulties in adjusting to this lifestyle of presence and absence of workers, some studies referred to ‘living two lives’, causing role conflicts and disruption to life leading to tension and irritation (Gardner et al., Citation2018; Mayes, Citation2020; Morrice et al., Citation1985; Parkes et al., Citation2005; Silva-Segovia & Salinas-Meruane, Citation2016). Some partners expressed experiencing tensions between showing of and the need to play down their developed emotional capability when FIFO worker returns home (Pini & Mayes, Citation2012). Some partners indicated experiencing emotional strain due to disruption of family life as partners feel separated from workers when at home (Morrice et al., Citation1985; Parkes et al., Citation2005), citing the need for workers to recover from fatigue (Parkes et al., Citation2005) or catching up with lost social events (Morrice et al., Citation1985). Partners also consistently expressed stress and anxiety in the periods prior to workers going away from home to work (Morrice et al., Citation1985; Parkes et al., Citation2005).

Despite the concerns and strains expatiated, there was evidence to show rotation work lifestyle could have positive effects on partners’ personal and emotional development, particularly among those without children/younger children or of long-serving rotation workers. Three of the qualitative studies showed rotation partners, particularly those of long-serving rotation workers, can become more independent and resourceful (developing coping abilities and skills) and overcome emotions as they adapt to the rotation work lifestyle (Morrice et al., Citation1985; Parkes et al., Citation2005; Pini & Mayes, Citation2012). Furthermore, studies indicated that some partners in the absences of workers develop their own capabilities (Morrice et al., Citation1985), personal confidence (Parkes et al., Citation2005) and the sense of control and empowerment in making decision regarding the family (Whalen & Schmidt, Citation2016) over time. Other studies indicated that in the absence of the workers some partners get free time to socialise with others and increase their social networks (Mayes, Citation2020; Morrice et al., Citation1985; Pini & Mayes, Citation2012).

Sleep problems among partners

Three studies examined sleep problems among partners in the absence of rotation workers. Two of the studies examined sleep quality, specifically, and both indicated poorer sleep quality in the absence of workers. One cross-sectional study showed significantly poorer sleep quality among partners in the absence of workers than in their presence at home (Wilson et al., Citation2020). Similarly, a daily diary study examining within-person differences in the sleep quality found significantly poorer sleep quality among partners when workers were on-shift away from home (Rebar et al., Citation2018).

One of the studies examined partners’ sleep duration and reported sleep duration was not significantly longer in the presence of workers than in the absence of workers (Wilson et al., Citation2020). One of the studies examined general sleep difficulties and found more partners of offshore rotation workers experience sleep difficulties when workers were away at work (20%) than when at home (14%) (Taylor et al., Citation1985).

Evidence on partners’ sleep compared to general population was unclear. Of two cross-sectional studies, one study reported statistically significantly shorter sleep duration, excessive sleepiness and poor sleep quality among partners of onshore rotation workers compared to the general population, in the presence or absence of rotation workers (Wilson et al., Citation2020). The other study using symptoms checklist scale found similar proportions of partners (20%) in the absences of workers and less proportion of partners (14%) in the presence of workers compared to a secondary data source of the general population (20%) experience sleep difficulties (Taylor et al., Citation1985).

Physical health

Three quantitative studies that investigated the physical health of partners of rotation workers found perceived good physical health status. Of the studies, two cross-sectional studies reported comparable proportions of partners of rotation workers perceived to have good physical health status as measured by self-rating of general health to that of the comparing group of partners of onshore non-rotation workers (Morrice et al., Citation1985; Taylor et al., Citation1985). Another daily study reported partners’ daily intake of medication for physical impairments (as a self-reported measure of physical health) was not common, but significantly higher during workers’ on-shift than off-shift days (Rebar et al., Citation2018).

Health-related lifestyle behaviours (alcohol intake, smoking, exercise and relaxation)

Alcohol intake

Three quantitative studies examined alcohol intake, and the results suggested some partners may consume more alcohol in the presence than absence of rotation workers, but that alcohol intake or alcohol-related problems were similar to partners of other workgroups and women in the general population. Of the three studies, two examined alcohol intake using checklists scales; one of the study found no statistically significant difference in proportions of alcohol intake problems between partners and comparison groups of partners of non-rotation workers (Cooke et al., Citation2019). Similarly, the other study also found levels of alcohol intake was not statistically significantly different between partners and comparison groups of women in the general population of women (Dittman et al., Citation2016). The third study using self-reported measure examined within-person differences between presence and absence of workers, and found alcohol consumption was significantly higher in the presence of workers (Rebar et al., Citation2018).

Smoking, diet, exercise and relaxation

One daily study examined within-person differences between presence and absence of workers and found partners were more likely to consume foods with poorer nutrition quality, carry out fewer exercises, and have less time to relax in the absence of rotation workers (Rebar et al., Citation2018). The study also reported partners smoke significantly more in the absence of onshore rotation workers (Rebar et al., Citation2018).

Mental health and wellbeing of children

Psychological distress and wellbeing

Evidence of the impact of rotation work on the mental health and wellbeing of children was unclear. Two quantitative studies found high symptoms of mental health outcomes whereas two other studies did not. Three cross-sectional studies using cut-off points on validated scales, examined the prevalence of mental health outcomes. One of the studies reported a significantly higher prevalence of symptoms of anxiety among children of offshore rotation workers than a comparison group of children of onshore based workers (56.2% vs 32.3%, p = 0.03) (Zargham-Boroujeni et al., Citation2015). Another study established prevalence of symptoms of moderate (9.1% vs 6.9%, p = 0.02) and severe (3.0% vs 2.8%, p = 0.03) depression significantly higher in adolescents of onshore rotation parents than in a comparison group of adolescent from non-rotation work families (Lester et al., Citation2016).

The other study established lower proportions of adolescents of onshore rotation parents (2%) show mental health level of clinical significance compared to a secondary data source of the general population (10%) (Lester et al., Citation2015). Similarly, one cross-sectional study using symptoms checklist scores on validated scales reported children of onshore rotation workers had depression and anxiety levels within healthy functioning and found no significant difference between them and the children of military and community families (Kaczmarek & Sibbel, Citation2008).

Qualitative evidence was also unclear. Studies revealed many children enjoy the rotation work lifestyle as it provides enough free days to spend and socialise with parents during the leave period (MacBeth & Sibbel, Citation2012; Parkes et al., Citation2005), expressed feeling relaxed and less stressed when rotation parent was away as they can have friends come over (MacBeth & Sibbel, Citation2012) and feel happy being able to avoid parents taking out their frustration on them or punishment (Mauthner et al., Citation2000). Furthermore, children of offshore rotation workers indicated to see their fathers more (during leave days) than children of onshore office workers (Mauthner et al., Citation2000). However, some children were experiencing incidences of sadness or loneliness when their fathers started working on long-distance commuting job arrangements or rotation job in a qualitative study (Whalen & Schmidt, Citation2016). Some children also indicated feeling hurt by their parent’s absence and expressed worries/anxieties about the safety of their father when away at work (Mauthner et al., Citation2000).

Behavioural and emotional problems

Studies investigated the rotation work impact on children’s behavioural and emotional issues, and findings were unclear. Three quantitative studies examined behaviours and emotions using checklist scores on validated scales. Out of the three studies, one cross-sectional study showed significantly higher levels of emotional and behavioural difficulties including conduct problems, hyperactivity, and peer problems were found among adolescents of onshore rotation parents than in comparison group of adolescents from non-rotation families (Lester et al., Citation2016). However, other two cross-sectional studies reported parents rated their adolescent children as not suffering from emotional difficulties (Lester et al., Citation2015), and that levels of behaviour and emotional difficulties were statistically similar among children in rotation families and a recruited comparison group of non-rotation families (Dittman et al., Citation2016).

However, three cross-sectional studies found parental rotation work characteristics and associated wellbeing were related to children’s behaviour and emotional difficulties. Rotation parent working excessive working hours and being too emotional and exhausted were related to emotional and peer problems in children; working excessive hours was also related to worse hyperactivity in children whereas parental tiredness and sleep disruption were associated with conduct and emotional problems among children (Robinson et al., Citation2017). Similarly, poor parental emotional adaptation, parental weekly working hours and perceived effect of rotation work lifestyle on family were found to predict children’s behaviour and emotional problems (Dittman et al., Citation2016). Parental presence (which is limited by rotation work intermittent presence and absence) was established to be related to adolescents’ behavioural and emotional problems (Dittman et al., Citation2016) and mediated the negative effect of working rotation on adolescents’ emotional and behavioural problems (Lester et al., Citation2016).

Qualitative evidence on emotional and behavioural outcomes also remains unclear. Evidence from two qualitative studies suggested some children of offshore rotation workers develop emotional strain and rejection behaviours towards workers as a result of missing parent and feeling upset about the absence of parent (Mauthner et al., Citation2000; Parkes et al., Citation2005) and parent missing special family events (Mauthner et al., Citation2000); tended to perceive their mother as being bad towards them (Parkes et al., Citation2005); and get annoyed seeing their mothers carry out their father’s house chores (Mauthner et al., Citation2000). However, two qualitative studies reported partners of rotation workers indicated some children become independent and well-adjusted (Parkes et al., Citation2005) and do not exhibit any serious behavioural and emotional problems (Whalen & Schmidt, Citation2016).

Discussion

Impact of rotation work arrangement on mental health and wellbeing of partners

Evidence on the mental health and wellbeing of partners remains unclear. The inconsistencies in the findings of quantitative studies could be attributed to the methodological differences between the included studies, including differences in measurement tools used. However, several qualitative studies suggested some partners of rotation workers experience emotional distress and anxiety, and social isolation and/or loneliness, particularly in the absence of workers. Other studies have found similar results highlighting the negative impact of rotation work on the mental health of partners (Dittman, Citation2018; Parker et al., Citation2018). Evidence from our review is in line with the Work-Family Conflict Theory, and its focus on the inter-role conflicts and the associated stress outcomes (Allen et al., Citation2000; Greenhaus & Beutell, Citation1985). For instance, studies in the review reported that in the absences of workers, at-home partners take up additional domestic and parental roles increasing their demands/burden and the likelihood of work-family conflicts (Greenhaus & Beutell, Citation1985) and could result in stress-related outcomes such as psychological strains and depressive symptoms (Allen et al., Citation2000).

Evidence from our review also showed a spillover of workers’ strains from work into the home domain and in turn cross over to the partner in line with the Spillover Crossover Model. For instance, studies in the current review identified that workers’ job demands make workers tired and exhausted upon their return home (increasing their spillover or work-family conflict), and that impact negatively on their interaction with the family (affecting relationship quality) resulting in feelings of isolation and emotion strains among the at-home partners. It has been demonstrated that workers’ high job demands increased work-family conflicts and poor relationship quality which in turn resulted in increased depressive symptoms and physical complaints among their partners (Shimazu et al., Citation2009).

The findings in our review are also consistent with the Attachment Theory; in the absence of a romantic partner, at-home partners’ sense of safety may be threatened due to the unavailability of their ‘secure base’ and ‘safe haven’, and their need for ‘proximity maintenance’ is diminished (Mikulincer et al., Citation2002); causing them to experience anxiety and depression (Bowlby, Citation1980). The intermittent absence of partners due to rotation work suggests constant disruptions to the accustomed pattern of family life including ‘changes in parenting roles and responsibilities, family dynamics, and day-to-day interactions among family members’ (Dittman, Citation2018, p. 528) which could cause insure attachments.

Similar temporary work-related separations from romantic partners in military families are found to be associated with emotional distress, including increased anxiety, depression, loneliness, and anger in at-home partners (Medway et al., Citation1995). Furthermore, consistent separations over a long period suggesting workers may consistently not be responsive to their partners’ needs and seem neglectful when away, could make at-home partners develop insecure-avoidant attachment where partners exhibit emotional detachment and seems unaffected by separations or reunion (Rholes & Simpson, Citation2004). As reflected in our review, some partners particularly those with long experience of rotation work lifestyle of intermittent separations, expressed overcoming emotions, developing own capabilities, personal confidence and sense of control and empowerment in decision making and becoming more resourceful over time.

The current review findings can also be considered within the framework offered by Social Ecological Theory. At the individual level, the partner’s history/long experience of rotation lifestyle and coping abilities (Pini & Mayes, Citation2012) were notably highlighted to shape the experience of emotional distress. Rotation work is regarded as temporary employment for many families but those who decide to stay on may actively develop and engage in strategies that help them deal with the associated stressors (Gallegos, Citation2006). Interpersonal level factors such as having children and disruptions to routine and parental roles were also noted. Having children could keep at-home partners companion thus mitigating against issues of social isolation and loneliness (Parkes et al., Citation2005; Pini & Mayes, Citation2012), but could also be stressful in helping them (particularly younger children) understand and deal with the rotation lifestyle of an intermittent absence of a parent (Parkes et al., Citation2005). It can also be stressful raising children alone and taking on new parental roles such as ensuring discipline (Parkes et al., Citation2005).

Notable at the community level, there was a general lack of appropriate social support. Support from extended families, community and other rotation work families are suggested to help mitigate against negative stressors of rotation work (Gardner et al., Citation2018). There are now, for example in Australia, several online support networks such as FIFO families that have been indicated to provide support on mental health and family issues (Gardner et al., Citation2018; Lester et al., Citation2015; Meredith et al., Citation2014). Encouraging strong social networks could provide suitable support during separations to reduce the high psychological distress among partners.

At the organisational level, work schedule, communication infrastructure (Pini & Mayes, Citation2012), and the level of job risk and security (Gardner et al., Citation2018; Parkes et al., Citation2005) were highlighted to influence the development of psychological distress among at-home partners. Work schedules allowing for more days for recovery and reducing commuting time could allow workers to spend more time with their families (Gallegos, Citation2006). Improvement in communication infrastructure allows for families to regularly interact, which fosters family relationships (Gardner et al., Citation2018; Whalen & Schmidt, Citation2016) and alleviate the worries of partners’ safety at work (Parkes et al., Citation2005). Organisations could promote a supportive climate for families such as healthcare services (Orthner & Rose, Citation2009), and reliable and quality communication infrastructure to aid and/or improve regular communication with families to foster family connectedness when workers are away (Diamond et al., Citation2008).

There was evidence in the current review to suggest that some partners may experience poor sleep quality in the absence of rotation workers, consistent with the finding of a study that reported at-home partners to experience sleep problems on separation of a romantic partner (Diamond et al., Citation2008). Sleep is a ‘shared behaviour’ in which sleeping together with a partner could provide a sense of security, comfort and the sharing of assurances (Hislop, Citation2007), and as such, the absence of rotation workers could impact negatively on the sleep of their partners. According to the Attachment Theory, inconsistent or neglectful caregiving, which could result from the intermittent absence of rotation workers from home, creates insecure attachment (Holden, Citation2010). Studies have demonstrated partners with insecure attachment (particularly high anxious partners) tend to have poorer sleep quality (Carmichael & Reis, Citation2005; Diamond et al., Citation2008) as they worry over the emotional inaccessibility and responsiveness of attachment figures (Carmichael & Reis, Citation2005).

Furthermore, in the absence of rotation workers, partners are also engaged in multiple roles and the stresses from these roles could contribute to sleep disturbances: partners have indicated ‘stress of work and children’ prevented them from taking a nap or getting enough sleep (Wilson et al., Citation2020). This is in line with the Work-Family Conflict Theory, where high demands increase the likelihood of partners’ work-family conflict which have been demonstrated to be associated with poor sleep outcomes (Borgmann et al., Citation2019).

Our findings also suggest perceived good physical health among at-home partners of rotation workers. However, there are too few studies (which relied on self-rated physical health on single items) to justify overall conclusions about the physical health of partners of rotation workers. This emphasises the necessity for more robust research to explore the physical health of partners of rotation workers, given that in the absence of workers, partners’ job demands increase and in turn experience work-family conflict, which has been indicated to be associated with poor physical health (Allen et al., Citation2000).

Our review suggests level of alcohol consumption among partners of rotation workers is similar to partners of non-rotation workers, and some partners may consume more alcohol when workers are at home (Rebar et al., Citation2018), however studies examining alcohol consumption were few. Drinking alcohol is often a shared experience influenced by family, friends and social groups (Morris et al., Citation2020). Evidence suggests having a spouse who consumes a high level of alcohol is associated with high alcohol consumption in their partners (Polenick et al., Citation2018), and rotation workers are reported to consume high levels of alcohol during off-shift days (Asare et al., Citation2021). The Attachment Theory stipulates persons are more likely to engage in exploration or ‘novelty seeking’ when in environments they feel safe due to the availability and responsiveness of their attachment figures (Holden, Citation2010). Further, negative emotions/distress due to the high job demands of rotation workers (Asare et al., Citation2021) could spillover and crossover to their partners during reunions and that could promote the high intake of alcohol, as studies have demonstrated crossover negative emotions during reunions to be associated with binge drinking behaviour (Liu & Visher, Citation2019).

Limited studies examined partners’ smoking, exercise and relaxation, and nutrition behaviours and again evidence is scarce to make definite conclusions. These findings suggest a need for more research looking at the effects of rotation work arrangements and workers’ presence and absence, and wellbeing on the health-related behaviours of partners owing to their known long-term health consequences. As speculated by Rebar et al. (Citation2018), partners in the absence of workers may have additional responsibilities limiting their time to engage in exercises or relaxation in line with the Work-Family Conflict Theory; and the increased stress in the absence of workers may increase the urges for smoking and influence eating behaviour.

Impact of rotation work arrangement on mental health and wellbeing of children

The findings regarding rotation work impact on the mental health of the children of rotation workers remain unclear. Children form emotional bonds with their parents, and separations from them are indicated to threaten these bonds, which may lead to the experience of anxiety and depressive symptoms (Bowlby, Citation1980). Furthermore, parental job demands through spillover (work-family conflict) and reduced quality of relationship (crossover) could affect the wellbeing of their children (Shimazu, Citation2015). More research is therefore required to examine the influence of rotation workers’ job demands and absence on the mental health of children of rotation workers and the mechanisms employed by at-home parents to mitigate the effects of workers’ absence on children.

The impact of rotation work on the emotions and behaviours of children in rotation workers’ families remains unclear. However, evidence from the current review support the Spillover Crossover Model; in that rotation work demands and their consequential strains were reported to be related to the emotional and behavioural problems of children. As has been suggested, parental work demands could lead to work-family conflict which sequentially could affect parental behaviour (e.g. negative parenting), impart emotions, and family functioning (e.g. poor relationship quality), which potentially affect the wellbeing of children (Shimazu et al., Citation2020).

Evidence also supports the Attachment Theory and its focus on the impact of distressing separations and reunions. For example, studies in the current review suggest that rotation work lifestyle can result in insecure attachment relationships between parents and children, as rotation parents may be inconsistent in responding to the needs of their children, whereby children may ‘show signs of emotional disengagement and withdrawal, and engage in behaviours that keep them distracted from the distress they are feeling’ (Rholes & Simpson, Citation2004, p.6). Children with parents working non-standard work schedules have been found to have emotional and behavioural problems at high levels (Strazdins et al., Citation2006), and as a result of ‘worse family functioning, more parent distress and ineffective parenting’ (Strazdins et al., Citation2006, p.403).

Strategies to reduce the impact of rotation work on the emotions and behaviours of children could include decreasing parental job demands and improving their job resources to promote work-family facilitation and in turn improve parental happiness, which may in-turn reduce the emotional and behavioural problems of their children (Shimazu et al., Citation2020). Secondly, supporting at-home partners where there are challenges with emotions and behaviours of their children. Positive strategies including specifying and reinforcing boundaries, regular open and significant communication; spending quality family time together during leave periods; and maintenance of family routines even in the absence of rotation parent (Lester et al., Citation2015). Social support networks have also been identified to assist in the nurturing of adolescent children of rotation workers (Lester et al., Citation2015). These may be in line with ways of maintaining and reassuring children of the secure attachment relationships between rotation parents and children, where children trust parents to be responsive to their needs when required (Rholes & Simpson, Citation1997).

Strengths and limitations of the study

The inclusion of qualitative findings alongside quantitative studies is a strength of the current review and can support the understanding of quantitative findings by giving in-depth insights into the health outcomes of rotation workers’ partners and children. This was the first review that investigated the impact of rotation work on workers’ families in the global resource and related construction sectors. Due to nature of data collected and heterogeneity of the included studies, we could not produce a funnel plot to demonstrate potential risk of publication bias. The findings of the review could be limited by publication bias, as only peer-review publications in English were included; however, their quality is potentially higher than the quality of non-peer reviewed studies. There were generally few studies examining the health outcomes and lifestyle behaviours of partners and children of rotation workers in relation to rotation work. The available cross-sectional studies were limited in making causal interpretations of the findings. Additional longitudinal studies are required to give insights into how partners and children experience the health impact of intermittent absence and presence of rotation workers and how their predictors change over time.

Other limitations were small sample sizes in some included studies (Kaczmarek & Sibbel, Citation2008; Lester et al., Citation2015; Rebar et al., Citation2018) and studies have generally recruited study sample through convenience sampling, which may affect the representativeness of recruited samples. A few of the included studies (15.8%) had low methodological quality which may limit the accuracy of the study findings, but such studies are relevant for inclusion into narrative reviews (Duran, Citation2013; Lucas et al., Citation2007), particularly with fewer studies examining the outcomes of interest (Duran, Citation2013).

Implications for policy and research

The current review identified a number of key areas for organisations employing rotation work arrangements and research to consider. Organisations wishing to promote the mental health and wellbeing of workers should also extend the support mechanisms to the families of the workers, as evidence suggests at-home partners and children can be negatively impacted by the intermittent presence and absence of the rotation workers, and this, in turn, can impact negatively on workers. Interventions could include the development of training and mentoring programs aimed at increasing the capacity to understand and manage the demands and challenges of rotation work lifestyles (Pini & Mayes, Citation2012); and to deal with the family demands (Parkes et al., Citation2005). Programs could also include developing partners’ stress management skills and their ability to cope with the associated emotions around the intermittent presence and absence of spouses (Parkes et al., Citation2005; Pini & Mayes, Citation2012). Such programs could target partners of new/young rotation work families to support their balancing domestic and family demands in the absence of their spouses, in order to help minimise any distress among partners.

Furthermore, organisations should help facilitate improved communication strategies between workers and their partners to help in reducing the associated sense of loneliness and isolation, and the anxieties of at-home partners in dealing with family demands in the absence of rotation workers (Gardner et al., Citation2018; Parkes et al., Citation2005). The findings suggest that interventions could also include approaches to support at-home parents, where there are challenges with emotions and behaviours of children because of the demands of the rotation work lifestyle. Research suggests that, in general, enhancing positive parenting skills reduces child behavioural problems (Sanders et al., Citation2014). Programs including the Triple P-positive parenting program, which enhances ‘the knowledge, skills, and confidence of parents’ ‘to prevent and treat social, emotional, and behavioural problems in children’ (Sanders et al., Citation2014, p. 339) could be exploited in the rotation work parents.

Additional research is needed, particularly in examining the absence and presence of workers and family demands on the mental health, physical health, sleep problems and health-related behaviours among partners of rotation workers, as limited studies and mixed findings exist to understand the impact of rotation work on the families of workers. Future studies are also required in examining the parental absences and separation, and parental wellbeing influence on mental health and the behaviours and emotional functioning of children, and the parenting strategies that assist to alleviate the effects of workers’ absence on children. Particularly, longitudinal studies with large samples are essential to explore the short and long-term health effects of rotation work on the health outcomes of partners and children of rotation workers to give insight into how partners and children of rotation workers experience health and to determine the factors that influence the health outcomes over time.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (40.7 KB)Acknowledgements

We express our sincere gratitude to Ms Diana Blackwood and Ms Vanessa Varis, Librarians for the Faculty of Health Sciences at Curtin University for their professional assistance in developing the review search strategy.

Conclusion

The impact of rotation work on the mental health and wellbeing of the partners and children of rotation workers remains unclear. On days where spouses are away, partners may experience greater loneliness and poorer sleep quality. Partners may benefit from support in balancing the increased domestic and family demands, particularly when they have younger children and/or their spouses first begin rotation work jobs. Research is limited, particularly in regard to the impact on health-related behaviours and physical health outcomes.

Disclosure statements

No potential conflict of interest declared by the authors.

Data availability statement

All data are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allen, T. D., Herst, D. E., Bruck, C. S., & Sutton, M. (2000). Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(2), 278–308. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.2.278

- Asare, B., Kwasnicka, D., Powell, D., & Robinson, S. (2021). Health and well-being of rotation workers in the mining, offshore oil and gas, and construction industry: A systematic review. BMJ Global Health, 6(7), e005112. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005112

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2013). The spillover – crossover model. In J. G. Grzywacz & E. Demerouti (Eds.), New frontiers in work and family research (pp. 54–70). Taylor & Francis Group.

- Borgmann, L. S., Rattay, P., & Lampert, T. (2019, July). Health-related consequences of work-family conflict from a European perspective: Results of a scoping review. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00189

- Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss: Loss and depression (Vol. 3). Basic Books. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02049873

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). Ecological models of human development. In T. Husen & T. N. Postlethwaite (Eds.), International encyclopedia of education (2nd ed., Vol. 3, pp. 1643–1647). Elsevier Sciences.

- Carmichael, C. L., & Reis, H. T. (2005). Attachment, sleep quality, and depressed affect. Health Psychology, 24(5), 526–531. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.24.5.526

- Cooke, D. C., Kendall, G., Li, J., & Dockery, M. (2019). Association between pregnant women’s experience of stress and partners’ fly-in-fly-out work. Women and Birth, 32(4), e450–e458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2018.09.005

- Diamond, L. M., Hicks, A. M., & Otter-Henderson, K. D. (2008). Every time you go away: Changes in affect, behavior, and physiology associated with travel-related separations from romantic partners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(2), 385–403. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.95.2.385

- Dittman, C. K. (2018). The importance of parenting in influencing the lives of children. In M. R. Sanders & K. M. T. Turner (Eds.), Handbook of parenting and child development across the lifespan (pp. 511–533). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-94598-9_1

- Dittman, C. K., Henriquez, A., & Roxburgh, N. (2016). When a non-resident worker is a non-resident parent: Investigating the family impact of fly-in, fly-out work practices in Australia. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(9), 2778–2796. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0437-2

- Duran, B. (2013). Posttraumatic growth as experienced by childhood cancer curvivors and their families: A narrative synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 30(4), 179–197. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043454213487433

- Gallegos, D. (2006). Fly-in fly-out employment: Managing the parenting transitions. http://researchrepository.murdoch.edu.au/id/eprint/10916/1/aeroplanes.pdf

- Gardner, B., Alfrey, K. L., Vandelanotte, C., & Rebar, A. L. (2018). Mental health and well-being concerns of fly-in fly-out workers and their partners in Australia: A qualitative study. BMJ Open, 8(3), e019516. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019516

- Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. The Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 76–88. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1985.4277352

- Hislop, J. (2007). A bed of roses or a bed of thorns? Negotiating the couple relationship through sleep. Sociological Research Online, 12(5), 146–158. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.1621

- Holden, G. W. (2010). Parenting: A dynamic perspective (3rd ed., pp. 27–54). SAGE Publications Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452204000.n2

- Kaczmarek, E. A., & Sibbel, A. M. (2008). The psychosocial well-being of children from Australian military and fly-in/fly-out (FIFO) mining families. Community, Work and Family, 11(3), 297–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668800801890129

- Langdon, R. R., Biggs, H. C., & Rowland, B. D. (2016). Australian fly-in, fly-out operations: Impacts on communities, safety workers and their families. Work, 55(2), 413–427. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-162412

- Lester, L., Waters, S., Spears, B., Epstein, M., Watson, J., & Wenden, E. (2015). Parenting adolescents: Developing strategies for FIFO parents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(12), 3757–3766. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0183-x

- Lester, L., Watson, J., Waters, S., & Cross, D. (2016). The association of fly-in fly-out employment, family connectedness, parental presence and adolescent wellbeing. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(12), 3619–3626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0512-8

- Liu, L., & Visher, C. A. (2019). The crossover of negative emotions between former prisoners and their family members during reunion: A test of general strain theory. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 58(7), 567–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/10509674.2019.1635243

- Lizarondo, L., Stern, C., Carrier, J., Godfrey, C., Rieger, K., Salmond, S., Apostolo, J., Kirkpatrick, P., & Loveday, H. (2020). Mixed methods systematic reviews. In E. Aromataris & Z. Munn (Eds.), JBI manual for evidence synthesis (pp. 270–307). Jonna Briggs Institute. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-01

- Lockwood, C., Munn, Z., & Porritt, K. (2015). Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 179–187. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000062

- Lucas, P. J., Baird, J., Arai, L., Law, C., & Roberts, H. M. (2007). Worked examples of alternative methods for the synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 7(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-7-4

- MacBeth, M. M., & Sibbel, A. M. (2012). Fathers, adolescent sons and the fly-in/fly-out lifestyle. The Australian Community Psychologist, 24(2), 98–114.

- Mauthner, N. S., Maclean, C., & McKee, L. (2000). ‘My dad hangs out of helicopter doors and takes pictures of oil platforms’: Children’s accounts of parental work in the oil and gas industry. Community, Work & Family, 3(2), 133–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/713658902

- Mayes, R. (2020). Mobility, temporality, and social reproduction: Everyday rhythms of the ‘FIFO family’ in the Australian mining sector. Gender, Place and Culture, 27(1), 126–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2018.1554555

- Medway, F. J., Davis, K. E., Cafferty, T. P., Chappell, K. D., & O’Hearn, R. E. (1995). Family disruption and adult attachment correlates of spouse and child reactions to separation and reunion due to operation desert storm. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 14(2), 97–118. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1995.14.2.97

- Meredith, V., Rush, P., & Robinson, E. (2014). Fly-in fly-out workforce practices in Australia: The effects on children and family relationships. (pp. 1–24). Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Mikulincer, M., Gillath, O., & Shaver, P. R. (2002). Activation of the attachment system in adulthood: Threat-related primes increase the accessibility of mental representations of attachment figures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(4), 881–895. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.4.881

- Moola, S., Munn, Z., Tufanaru, C., Aromataris, E., Sears, K., Sfetcu, R., Currie, M., Qureshi, R., Mattis, P., Lisy, K., & Mu, P.-F. (2017). Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In E. Aromataris & Z. Munn (Eds.), Joanna briggs institute reviewer’s manual (p. 6). The Joanna Briggs Institute. https://doi.org/10.17221/96/2009-CJGPB

- Morrice, J. K. W., Taylor, R. C., Clark, D., & McCann, K. (1985). Oil wives and intermittent husbands. British Journal of Psychiatry, 147(5), 479–483. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.147.5.479

- Morris, H., Larsen, J., Catterall, E., Moss, A. C., & Dombrowski, S. U. (2020). Peer pressure and alcohol consumption in adults living in the UK: A systematic qualitative review. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09060-2

- Orthner, D. K., & Rose, R. (2009). Work separation demands and spouse psychological well-being. Family Relations, 58(4), 392–403. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2009.00561.x

- Page, M., McKenzie, J., Bossuyt, P., Boutron, I., Hoffman, T., Mulrow, C., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J., Akl, E., Brennan, S., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M., Li, T., Loder, E., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2020, September). The PRISMA 2020statement: An updated guidelinefor reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery, 88, 105906. https://osf.io/preprints/metaarxiv/v7gm2/

- Parker, S., Fruhen, L., Burton, C., McQuade, S., Loveny, J., Griffin, M., Page, A., Chikritzhs, T., Crock, S., Jorritsma, K., & Esmond, J. (2018). Impact of FIFO work arrangements on the mental health and wellbeing of FIFO workers. Centre for Transformative Work Design.

- Parkes, K., Carnell, S., & Farmer, E. (2005). “Living two lives”: Perceptions, attitudes and experiences of spouses of UK offshore workers. Community, Work and Family, 8(4), 413–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668800500251755

- Pini, B., & Mayes, R. (2012). Gender, emotions and fly‑in fly‑out work. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 47(1), 71–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1839-4655.2012.tb00235.x

- Polenick, C. A., Birditt, K. S., & Blow, F. C. (2018). Couples’ alcohol use in middle and later life: Stability and mutual influence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 79(1), 111–118. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2017.79.111

- Rebar, A. L., Alfrey, K. L., Gardner, B., & Vandelanotte, C. (2018). Health behaviours of Australian fly-in, fly-out workers and partners during on-shift and off-shift days: An ecological momentary assessment study. BMJ Open, 8(12), e023631. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023631

- Rholes, S. W., & Simpson, J. A. (2004). Attached theory: Basics concepts and contemporary questions. In W. S. Rholes & J. A. Simpson (Eds.), Adult Attachment: Theory, research, and clinical implications. (pp. 3–14). The Guilfold Press.

- Robinson, K., Peetz, D., Murray, G., Griffin, S., & Muurlink, O. (2017). Relationships between children’s behaviour and parents’ work within families of mining and energy workers. Journal of Sociology, 53(3), 557–576. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783316674357

- Sanders, M. R., Kirby, J. N., Tellegen, C. L., & Day, J. J. (2014). The Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a multi-level system of parenting support. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(4), 337–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.04.003

- Shimazu, A. (2015). Heavy work investment and work-family balance among Japanese dual-earner couples. In C. L. Cooper & L. Luo (Eds.), Handbook of research on work-life balance in Asia (Vol. 28, pp. 61–76). Elgar Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781783475094.00009

- Shimazu, A., Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2009). How job demands affect an intimate partner: A test of the spillover–crossover model in Japan Akihito. Journal of Occupational Health, 51(3), 239–248. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.8.3.c2

- Shimazu, A., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., Fujiwara, T., Iwata, N., Shimada, K., Takahashi, M., Tokita, M., Watai, I., & Kawakami, N. (2020). Workaholism, work engagement and child well-being: A test of the spillover-crossover model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6213–6216. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176213

- Silva-Segovia, J., & Salinas-Meruane, P. (2016). With the mine in the veins: Emotional adjustments in female partners of Chilean mining workers. Gender, Place and Culture, 23(12), 1677–1688. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2016.1249344

- Storey, K. (2016). The evolution of commute work in the resource sectors in Canada and Australia. The Extractive Industries and Society, 3(3), 584–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2016.02.009

- Strazdins, L., Clements, M. S., Korda, R. J., Broom, D. H., & D’Souza, R. M. (2006). Unsociable work? Nonstandard work schedules, family relationships, and children’s well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(2), 394–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00260.x

- Taylor, R., Morrice, K., Clark, D., & McCann, K. (1985). The psycho-social consequences of intermittent husband absence: An epidemiological study. Social Science & Medicine, 20(9), 877–885. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(85)90344-2

- Whalen, H., & Schmidt, G. (2016). The women who remain behind: Challenges in the LDC lifestyle. Rural Society, 25(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10371656.2016.1152037

- Wilson, K. I., Ferguson, S. A., Rebar, A., Alfrey, K., & Vincent, G. E. (2020). Comparing the effects of FIFO/DIDO workers being home versus away on sleep and loneliness for partners of Australian mining workers. Clocks & Sleep, 2(1), 86–98. https://doi.org/10.3390/clockssleep2010009

- Zargham-Boroujeni, A., Shahba, Z., & Abedi, H. (2015). Comparison of anxiety prevalence among based and offshore national Iranian drilling company staff’s children in Ahvaz, 2013. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 4(May), 37. https://doi.org/10.4103/2277-9531.157215