ABSTRACT

The objective of this scoping review was to systematically review the literature on how non-financial conflicts of interest (nfCOI) are defined and evaluated, and the strategies suggested for their management in health-related and biomedical journals. PubMed, Embase, Scopus and Web of Science were searched for peer reviewed studies published in English between 1970 and December 2023 that addressed at least one of the following: the definition, evaluation, or management of non-financial conflicts of interest. From 658 studies, 190 studies were included in the review. nfCOI were discussed most commonly in empirical (22%; 42/190), theoretical (15%; 29/190) and “other” studies (18%; 34/190) – including commentary, perspective, and opinion articles. nfCOI were addressed frequently in the research domain (36%; 68/190), publication domain (29%; 55/190) and clinical practice domain (17%; 32/190). Attitudes toward nfCOI and their management were divided into two distinct groups. The first larger group claimed that nfCOI were problematic and required some form of management, whereas the second group argued that nfCOI were not problematic, and therefore, did not require management. Despite ongoing debates about the nature, definition, and management of nfCOI, many articles included in this review agreed that serious consideration needs to be given to the prevalence, impact and optimal mitigation of non-financial COI.

Introduction

Conflicts of interest (COI) in biomedicine have been the focus of extensive and increasing academic inquiry in recent years – with the number of publications on COI rising considerably from the mid-2000s onwards (Science Citation2024).

Most of this attention has been directed toward financial COI (in particular, those associated with the pharmaceutical and medical device industry) and their potential impact on the quality and integrity of research and publication processes, clinical care, policy development, and medical education (McKinney and Pierce Citation2017). However, growing concerns have been raised about the potential influence of non-financial COI (nfCOI) across these domains (Saver Citation2012; Wiersma, Kerridge, and Lipworth Citation2018). Non-financial COI include those that are relationship-based (e.g., personal or professional friendships or rivalries), belief-based (e.g., intellectual commitments and political, philosophical or religious viewpoints), and career-based (e.g., the desire for career advancement or recognition). As attention has turned to non-financial COI, debates have arisen about whether non-financial interests “count” as COI and if so, how best to define, categorize and manage them (L. Bero Citation2014; L. A. Bero and Grundy Citation2016; Grundy et al. Citation2020; Rodwin Citation2017).

Despite growing recognition of their potential impact on biomedicine, nfCOI remain poorly defined with no clear consensus about how they should be categorized and mitigated. This is a significant lacuna because in order to move forward with research into the prevalence, impact and mitigation of nfCOI, definitional consistency and a broadly agreed upon taxonomy of non-financial interests are required.

To address this gap, we conducted a scoping review of nfCOI in health-related journals. Scoping reviews are systematic and enable one to “map” evidence on a particular topic of interest (Arksey and O’Malley Citation2005; Munn et al. Citation2018). While often used to address specific healthcare questions, they can also be used to address conceptual issues that have policy implications in biomedicine (Arksey and O’Malley Citation2005; Colquhoun et al. Citation2017). The primary objective of this scoping review was to explore how nfCOI have been defined and evaluated, and what strategies have been suggested for their management in health-related and biomedical scientific journals. Secondary objectives were to identify the domains in which non-financial COIs were most frequently discussed, and the publication types in which these discussions typically take place (e.g., empirical studies, opinion or editorial articles). These objectives should allow for the identification of key gaps in the literature to determine where future research into non-financial COI should be directed.

Methods

Protocol

A protocol was prepared in advance of the study (see Appendix A). Scoping reviews are not eligible for registration in Prospero.

Our methods are reported according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyzes extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-SCR) (Tricco et al. Citation2018) (see Appendix B).

Eligibility criteria

Qualitative and quantitative research studies, reviews, commentary, and editorial articles published between 1970 and 2023 were included in this scoping review. The time frame was chosen as conflicts of interest first began to attract attention in the 1970s. Commentary, opinion and editorial articles were included because there has been a great deal written in opinion pieces about nfCOI, and because we were analyzing a concept and associated forms of reasoning, rather than answering a specific empirical question.

In order to be included in the review, an article had to be published in English, be peer reviewed (unless a letter or invited commentary) and address at least one of the following: the definition of non-financial COI, an assessment of nfCOI (i.e., whether or not they were problematic and, if so, why), or the management of nfCOI. The inclusion and exclusion criteria can be viewed in .

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Information sources and search strategy

In order to develop the search strategy, a librarian with expertise in systematic database searching and systematic reviews from the University of Sydney was consulted. PubMed, Scopus, Embase and Web of Science were searched in December 2023. The search terms used included “conflict of interest” and “non-financial” or “non-fiscal” or nonfinancial” or “non-pecuniary.” Searches were limited to full-text articles published in English from 1970 onward. The specific searches conducted can be viewed in Appendix C.

Reference lists of included studies as well as websites of journals that have numerous publications on non-financial conflicts of interest (including for example, the BMJ and JAMA) were also hand-searched using keywords related to non-financial conflicts of interest.

Study selection process

All search results were imported into Endnote for the removal of duplicates and then underwent two stages of screening. In the first stage, title and abstracts were screened to confirm that they were published in English and to check that they explicitly mentioned nfCOI. In the second stage, the full text of articles was evaluated against the inclusion criteria – with any articles that did not mention either the definition, evaluation or management of nfCOI excluded at this stage. The screening process was performed by Author 1, with any uncertainty about the eligibility of articles discussed at regular team meetings with Author 2 and Author 3.

Data items and data collection process

A data charting form was developed in Excel at the protocol stage and used to organize the information extracted from selected articles. The development of this charting form was informed by prior work on non-financial COI by the authors (Komesaroff, Kerridge, and Lipworth Citation2019; Wiersma, Ghinea, and Lipworth Citation2019; Wiersma, Kerridge, and Lipworth Citation2018; Wiersma et al. Citation2018), and can be viewed in .

Table 2. Data charting form.

The data extracted included general article information (including the first author’s last name and initial, title, journal where it was published and year of publication); the type of publication (e.g., research, commentary, perspective); the domain in which nfCOI were discussed (e.g., clinical or research context); the level at which COI were discussed (i.e., individual, institutional or both); the definition of COI and nfCOI, as well as attitudes toward nfCOI (i.e., whether or not they are problematic) and their management.

Synthesis

Basic quantitative analysis was used to explore and report on the type of publications that discussed nfCOI; the domains in which nfCOI were discussed; the level at which nfCOI were discussed; the definition of COI and whether nfCOI should be managed. Qualitative analysis – using a coding procedure informed by Charmaz’s work on grounded theory and Morse’s work on the cognitive basis of qualitative analysis – was used to analyze definitions of nfCOI and attitudes toward non-financial COI and their management (Charmaz Citation2006; Morse Citation1994). This process involved line by line coding, with the resulting codes then organized into categories. The process was iterative with codes and categories refined and reworked as new codes and categories were identified (Wiersma, Kerridge, and Lipworth Citation2020).

Results

Literature review

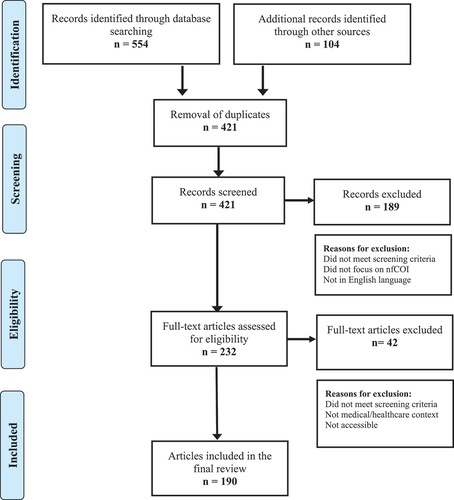

Five hundred and fifty-four articles were identified through database searching, with an additional 104 articles sourced via the authors personal Endnote libraries. Following the removal of duplicate articles, the titles and abstracts of 421 articles were screened. At this stage, 189 articles were excluded because they did not meet screening criteria. The full text of the remaining 232 articles were then screened, with a total of 42 articles excluded. The reason for the exclusion of articles at this stage included that they did not meet screening criteria, were not specific to the medical/healthcare context, were not accessible. We did not do a formal quality assessment of articles because of the heterogeneity of methods in included pieces and our interest in the full range of views on the topic. A total of 190 articles were included in the final review and their characteristics can be viewed in . provides an overview of articles that made specific claims. The screening process is outlined in . The complete data sheet can be viewed in Appendix D.

Table 3. Characteristics of 190 included studies.

Table 4. Overview of key claims made by articles.

Quantitative results

Types of publications that discuss non-financial COI

The most common publication type to explore nfCOI were empirical studies – including quantitative (e.g., surveys and cross-sectional studies) (Daou et al. Citation2018; D. B. Menkes et al. Citation2018; Shawwa et al. Citation2016) and qualitative studies (e.g., interview studies and qualitative context analyses) (Grundy, Mazzarello, and Bero Citation2020; Wiersma, Kerridge, and Lipworth Citation2020). Twenty-two percent (42/190) of articles were empirical research studies, while 15% (29/190) were theoretical research studies. The discussion of nfCOI also took place frequently in “other” articles 18% (34/190), editorials 17% (32/190) and letters 10% (19/190). nfCOI were discussed less frequently in review, 9% (17/190) feature 6% (12/190) and policy articles 3% (5/190).

Domains in which non-financial COI were discussed

Several broad domains in health and medicine in which nfCOI were frequently discussed were used in the data charting form. A brief description of these domains is provided below:

Research domain: activities that are part of the research process – e.g., the design of the study, choice of outcome variables and data analysis, and the roles of different individuals (e.g., researchers) and institutions (e.g., funders or sponsors) in this process.

Publication domain: activities that are part of the publication of research and the roles of different individuals (such as authors, reviewers, and editors) and institutions in this process.

Clinical practice domain: activities that take place in medical or health settings, and the roles of individuals and institutions in these settings.

Policy domain: the activities and roles of policymakers.

Education domain: educational activities that take place in undergraduate and postgraduate training, and in continuing medical education (CME) for medical professionals.

Medicine broadly: this domain was used to capture articles that addressed three or more of the above categories (if two domains were covered, these were included in both specific domains).

Most articles included in the review discussed nfCOI in the research domain (36%; 68/190) or publication domain (29%; 55/190). nfCOI were also discussed in the clinical practice domain (17%; 32/190) and policy domain (15%; 28/190). Ten percent (20/190) of articles discussed nfCOI in multiple domains (“medicine broadly”), while only 2% (4/190) of articles discussed nfCOI in the education domain.

Level at which COI were discussed

In this review, most articles 81% (154/190) focused on individual nfCOI. Eighteen percent (35/190) addressed both individual and institutional nfCOI, and one article addressed institutional nfCOI (i.e., COI that occur at the level of the institution, for example, an institution adopting a specific advocacy position).

Definition of COI

Given that the term “conflict of interest” remains contested, data on the definitions of COI provided by articles were collated. Forty-one percent (77/190) of articles failed to provide a definition of COI, while 23% (44/190) used the definition (or a close variation thereof) provided by the United States Institute of Medicine:

A conflict of interest exists when an individual or institution has a secondary interest that creates a risk of undue influence on decisions or actions affecting a primary interest. P 26 (Medicine Citation2009)

Thirty-two percent (60/190) offered a different definition of COI, while 5% (9/190) of articles critiqued multiple definitions of COI.

Management of nfCOI

Regarding the question of whether nfCOI require management, 55% (104/190) of articles argued that nfCOI should be managed, 11% (21/190) of articles claimed that nfCOI did not require management, while 22% (41/190) did not make recommendations regarding the management of nfCOI.

Qualitative results

Definition of non-financial Conflict of Interest (nfCOI)

Numerous terms were used to refer to nfCOI – including non-financial interests, intrinsic interests (Tsai Citation2011), relational interests (Epstein Citation2007), intellectual interests (Guyatt et al. Citation2010; Shawwa et al. Citation2016), non-financial sources of bias (Brown et al. Citation2014), competing interests (Rivera and Panduro Citation2018), intellectual bias (Dellinger and Durbin Citation2007), secondary interests (Thompson Citation1993; Hurst and Mauron Citation2008), academic interests (Annane et al. Citation2019), and perspectives of interest (Cook Citation2009). One author argued that nfCOI should not be considered conflicts of interest at all , i.e., that the definition of COI should refer only to financial conflicts (L. A. Bero and Grundy Citation2016).

Non-financial COI were described in varied ways across articles. Five broad types of nfCOI were identified: belief or viewpoint based; career related; interpersonal; research related; and status related Some articles focused solely on one type of nfCOI (Akl et al. Citation2014; Akl, Karl, and Guyatt Citation2012; Cook Citation2009; Twisselmann Citation2018), whereas others addressed multiple types of nfCOI (L. A. Bero and Grundy Citation2016; N. Editors Citation2018; Gjersvik Citation2015; Goozner et al. Citation2009; Graham, Alderson, and Stokes Citation2015; Sugarman Citation2005).

Belief or viewpoint based nfCOI

Numerous articles described non-financial COI as arising from an individual’s religious, moral, philosophical, ideological or political belief. Religious beliefs, in particular, were frequently singled out as a potential source of nfCOI, with several articles focused specifically on religious or spiritual beliefs (Cook Citation2009; Ghinea et al. Citation2020; Smith and Blazeby Citation2018; Twisselmann Citation2018). Strongly held viewpoints about contentious issues such as vaccination, abortion and sterilization were also seen to be a potential source of nfCOI (Guibilini and Savulescu Citation2020; McKinney and Pierce Citation2017). Some articles claimed that research on cognitive biases demonstrates that strongly held beliefs can influence individuals’ behavior, which in turn, was used to argue for greater recognition of beliefs and values as an important source of nfCOI (Radan Citation2021).

Career-related nfCOI

Numerous articles drew attention to career-related nfCOI – including the desire for career advancement and professional recognition; institutional-related pressures; professional and institutional loyalties; intellectual legacy; affiliation with a particular specialty; and commitment to particular methodology or approach. For example, in regard to nutritional research, Ioannidis argued that an individual’s commitment to theory can have far-reaching effects (J. P. A. Ioannidis and J. F. Trepanowski Citation2018a, Citation2018b), while Levinsky claimed that research-related deaths had been connected to an investigator’s “excessive zeal to complete a project” (Levinsky Citation2002). Other articles described the importance of recognizing the entwinement between non-financial and financial COI, with the desire for career advancement linked with financial incentives (Flier Citation2017; Swanson and Brown Citation2018).

Career-related nfCOI were discussed commonly in the research domain. Research-related nfCOI included researchers receiving prestigious grants; publishing in high-impact journals (Abbas et al. Citation2018; DiRisio et al. Citation2019; Romain Citation2015); their desire to strengthen one’s scientific position or to prove a hypothesis (Brody Citation2011; Cherla et al. Citation2018; Malay Citation2016; Schwab Citation2018); fulfilling academic requirements (Geiderman et al. Citation2017; Goldrick, Larson, and Lyons Citation1994); vindicating one’s intellectual ability and receiving awards or recognition (Korn Citation2000; Romain Citation2015; Sollitto et al. Citation2003; Sollitto, Youngner, and Lederman Citation2002; Young Citation2009).

Interpersonal nfCOI

Interpersonal nfCOI were also raised frequently in articles. These included personal relationships (Hansen et al. Citation2019; Rivera and Panduro Citation2018; Thompson Citation1993), professional relationships (including additional roles held by clinicians or researchers such as advocacy positions, advisory board memberships or editorial positions) (Braillon Citation2018; N. Editors Citation2018; Pacheco et al. Citation2021). institutional relationships; friendships and rivalries (Horton Citation1997; Marcovitch et al. Citation2010); and group-related interests such as the desire to belong, get along with others, impress or influence others (da Silva et al. Citation2019; Geiderman et al. Citation2017; Korn Citation2000; Pellegrino Citation1992). Typically, interpersonal nfCOI were discussed alongside multiple types of nfCOI (often in lengthy lists of nfCOI) and it was rare for an article to focus solely on interpersonal nfCOI.

Status-related nfCOI

Status-related nfCOI – including the desire for status, prestige, fame or desire to be first – were raised in a minority of articles. Similar to interpersonal nfCOI, status-related nfCOI were typically discussed in conjunction with other non-financial interests – with, for example, a qualitative study by Wiersma et al. finding that medical professionals were able to identify specific nfCOI including status, respect and the avoidance of stigma (Citation2020).

Views about the significance of nfCOI

Of those articles that expressed an opinion toward non-financial COI, perspectives were sharply divided between those that perceived non-financial interests and associated COI as problematic, and those that did not.

Non-financial conflicts of interest are problematic

Articles in this category made a number of claims to support the argument that nfCOI are problematic. These claims included that nfCOI are pervasive and relatively under-explored (Annane and Chapentier Citation2018; Caplan Citation2012; Flier Citation2017; Robbins Citation2018; Rosenberg Citation2017; Williams-Jones Citation2011) that they have an equal or greater impact than fCOI (Ancker and Flanagin Citation2007; Bion Citation2009; Ghinea et al. Citation2020; Horrobin Citation1999; Shimazawa and Ikeda Citation2014) that non-financial interests are a significant source of bias (Bion Citation2009; Lo and Ott Citation2013; McKinney and Pierce Citation2017; Shaw Citation2014; West Citation2009) and that non-financial COI have adverse effects (DiRisio et al. Citation2019; P. M. Editors Citation2008, Citation2009; Geiderman et al. Citation2017; Nahai Citation2019; Romain Citation2015) – such as compromising public trust in the medical profession and scientific community (Krutsinger, Halpern, and DeMartino Citation2018; Saver Citation2012; Etzel et al. Citation2005; American College of Emergency Physicians Citation2017).

nfCOI are pervasive and under-explored

The claim that nfCOI are pervasive was raised both by articles that perceived nfCOI as problematic and those that did not. For those who saw nfCOI as problematic, it was their pervasiveness, the relative lack of attention they have received and absence of robust management strategies that was seen to be problematic (Flier Citation2017; Lipworth, Ghinea, and Kerridge Citation2019; Rosenberg Citation2017; Wiersma, Kerridge, and Lipworth Citation2018; Williams-Jones Citation2011). Several articles noted that while financial COI had received the most attention, certain types of nfCOI were likely to be more prevalent – yet nfCOI had remained largely ignored (Annane et al. Citation2019; Caplan Citation2007; Flier Citation2017; Williams-Jones Citation2011). The comparative lack of awareness about nfCOI, was in turn, seen to be a significant barrier to developing a more comprehensive and nuanced account of COIs (including both financial and non-financial COI) (Wiersma, Kerridge, and Lipworth Citation2018), and to developing appropriate management strategies able to account for the various types of COI (Rosenberg Citation2017; Wiersma, Kerridge, and Lipworth Citation2018; Williams-Jones Citation2011).

nfCOI have equal or greater impact than fCOI

Several articles claimed that nfCOI have an equal or greater impact than financial COI (Bion Citation2009; Horrobin Citation1999; Horton Citation1997; Jansen and Sulmasy Citation2003; Shimazawa and Ikeda Citation2014; Hirsch and Guyatt Citation2009). In the late 1999s, Horrobin claimed that nfCOI were “much more serious barriers” to the conduct and evaluation of research, including “fanaticism” as a type of nfCOI (Horrobin Citation1999). Horton argued that while non-financial COI may be less easily identified than financial COI, they may exert a powerful influence on an individual (Citation1997). Other more recent articles claimed that non-financial and financial COI equally influence the authors of clinical guidelines; (Hirsch and Guyatt Citation2009) cited evidence that patients perceive non-financial interests to be as much of a problem as financial sources of bias (Bion Citation2009); and argued that certain non-financial interests (for example, the desire for professional advancement) may be “more corrupting” than financial incentives (Shimazawa and Ikeda Citation2014). Claims of the equivalent impact of non-financial to financial COI were often followed by the argument that there is no logical rationale as to why financial COI should be highlighted and non-financial COI ignored (Jansen and Sulmasy Citation2003; Wiersma, Kerridge, and Lipworth Citation2018), and therefore, that both should be managed (Wiersma, Kerridge, and Lipworth Citation2018).

Non-financial interests are a source of bias

Some articles stated explicitly that COI cause bias (Etzel et al. Citation2005; Lo and Ott Citation2013; McKinney and Pierce Citation2017), while others were unclear on the relationship between the concepts (Abdoul et al. Citation2012; Allison Citation2009; Shaw Citation2014). Overall, most articles claimed that non-financial interests were a significant source of either bias or COI (Babor and Miller Citation2014; Detsky Citation2006; Lo and Ott Citation2013; Malay Citation2016; McKinney and Pierce Citation2017; Saver Citation2012; Shaw Citation2014; West Citation2009). Several articles noted that bias often occurs at an unconscious level (Romain Citation2015; West Citation2009), and is often overlooked (Bion Citation2009; West Citation2009).

Several articles emphasized that not all bias is bad (Romain Citation2015; West Citation2009). However, claims made by articles included that non-financial interests could bias an individual’s objectivity (Detsky Citation2006; Shaw Citation2014), the conduct and interpretation of research (Malay Citation2016; McKinney and Pierce Citation2017; Saver Citation2012), and unduly influence clinical decision-making (McKinney and Pierce Citation2017). Few articles provided supporting evidence for these claims, with the exception of Malay, who cited evidence that in the psychotherapy context, researchers’ belief in the effectiveness of a specific treatment impacts the outcome of clinical trials in a positive direction (Citation2016).

nfCOI have negative effects

The most frequently made argument to support the claim that non-financial COI were problematic was that they have a negative impact on the integrity of research, the publication process, clinical decision-making and patient care (Bernstein Citation2013; DiRisio et al. Citation2019; P. M. Editors Citation2008, Citation2009; El Moheb et al. Citation2021; Lundh et al. Citation2020; Nahai Citation2019; Romain Citation2015; Saver Citation2012). (Akl et al. Citation2022; Chimonas et al. Citation2021; Montgomery and Weisman Citation2021; Quaia Citation2023; D. Resnik Citation2023)

At the individual level, nfCOI were seen to have the potential to disrupt the research process(P. M. Editors Citation2008, Citation2009; El Moheb et al. Citation2021; Lundh et al. Citation2020; Nahai Citation2019; Romain Citation2015; Rosenbaum Citation2015b; Saver Citation2012) influencing the design, conduct and reporting of research (Bosch et al. Citation2013; Lundh et al. Citation2020; Saver Citation2012) and threatening participant safety (Saver Citation2012). Several articles viewed nfCOI as a potential source of scientific misconduct (Abbas et al. Citation2018; Annane et al. Citation2019; Bion Citation2009; Levinsky Citation2002) with Abbas claiming that non-financial COI were, at times, the likely reason for the retraction of scientific publications (Abbas et al. Citation2018). Additionally, institutional pressure placed on researchers to publish and researchers “excessive zeal” to complete a study were seen to drive misconduct, such as the failure to report adverse events (Levinsky Citation2002), and even to underpin fraud (Abbas et al. Citation2018; Annane et al. Citation2019; Bion Citation2009). Specific examples of nfCOI negatively impacting the research process were provided, with for example, several articles pointing out that financial interests did not feature strongly in the infamous Tuskegee study (Saver Citation2012; Wiersma, Kerridge, and Lipworth Citation2018), and that it was not only financial interests that played a role in the tragic death of Jesse Gelsinger, but also non-financial interests, such as excitement about the potential efficacy of gene therapy (Rosenbaum Citation2015a).

nfCOI were also perceived to compromise the integrity of the publication process (PLoS Med Anstey Citation2015; P. M. Editors Citation2008, Citation2009; Nahai Citation2019; Radan Citation2021). the development of clinical guidelines (Alexander et al. Citation2016) and the evaluation of academic grants (Abdoul et al. Citation2012). Concerns were raised that peer reviewers were not able to critique a competitor’s research objectively (Annane and Chapentier Citation2018; Gasparyan et al. Citation2013), while Alexander provided evidence that non-financial COI, including individuals’ political agendas, were seen to be a source of discordant recommendations by members of the World Health Organization (WHO) guideline development panels (Alexander et al. Citation2016). Abdoul et al. reported that those involved in the evaluation of academic grants were concerned that non-financial COI, such as rivalry or cronyism, had impacted the review process (Abdoul et al. Citation2012).

nfCOI were seen to influence clinical care and doctors’ decision-making processes (Anstey Citation2015; Geiderman et al. Citation2017; Romain Citation2015) – with for example, the enhanced status, reputation and academic standing associated with the use of novel surgical devices acting as powerful incentives for surgeons (Bernstein Citation2013; DiRisio et al. Citation2019). Clinicians’ desire to advance scientific and medical knowledge was also perceived to impact upon their clinical decision-making (Kesselheim and Maisel Citation2010).

While the impact of non-financial COI on institutions was discussed less frequently, several articles noted that non-financial interests (such as reputational concerns and the desire for status) could influence the decision-making processes of health and medical research institutions (DiRisio et al. Citation2019; Saver Citation2012). At the institutional level, non-financial interests were seen to be entwined with financial interests – with for example, doctors’ use of novel technologies improving the reputation of an institution, which increased patient volume and in turn, the profit made by the institution (DiRisio et al. Citation2019).

Non-financial COI are not problematic

Articles in this category pushed back against calls for attention to non-financial COI – with most claiming that financial COI are the “more serious problem” (Lenzer and Brownlee Citation2015, 1) that require attention and careful management (L. A. Bero and Grundy Citation2016; Lenzer and Brownlee Citation2015; Mintzes and Grundy Citation2018). Some articles considered non-financial COI too diverse to be able to be identified and managed effectively, whereas others argued that non-financial “interests” or “influences” should not be considered to be a type of COI. (Bero and Grundy Citation2018) Key differences between financial and non-financial interests were also emphasized, with several articles noting that financial interests could be avoided or eliminated, whereas non-financial interests could not as they were intrinsic to an individual (L. Bero Citation2014; Garattini, Padula, and Mannucci Citation2020; Goldberg Citation2020; Rodwin Citation2017). These claims were then used to support calls to focus attention on fCOI (L. Bero Citation2014; Goldberg Citation2020; Rodwin Citation2017).

Non-financial COI are poorly defined

Numerous articles noted that non-financial interests and COI were defined in vague and variable ways (L. Bero Citation2014, Mintzes and Grundy Citation2018; Garattini and Padula Citation2019; Garattini, Padula, and Mannucci Citation2020), which was seen to generate confusion about the concept and the nature of the issues associated with COI (L. A. Bero and Grundy Citation2016). While the original definition of COI was closely aligned to the traditional legal conceptualization of COI and focused on financial interests (Lankarani, Alavian, and Haghdoost Citation2011; Rodwin Citation2017), definition “creep” was perceived to have occurred over the years – with various types of non-financial interests incorporated into the definition of COI (L. A. Bero and Grundy Citation2016; Grundy Citation2021; Grundy et al. Citation2020; Rodwin Citation2017; Vincent, Christopher, and McLean Citation2018). Articles viewed this as problematic because it causes confusion and could result in the development of policies that are impractical (Rodwin Citation2017); make COI appear so pervasive that they were unmanageable (Grundy Citation2021); and result in the exclusion of diverse perspectives (Grundy et al. Citation2020). It was also claimed that definition creep had rendered the concept of COI “meaningless” or “useless,” with “almost everything” considered a potential conflict (Rodwin Citation2017; Vincent, Christopher, and McLean Citation2018).

Non-financial “interests” or “influences” are not a type of COI

Another argument commonly made by articles in this category was that non-financial interests or influences should not be considered to be a type of “conflict of interest” or treated as such. Several articles simply stated that non-financial interests were not a form of COI (Hanson et al. Citation2009; Rivera and Panduro Citation2018), whereas others attempted to explain why this was the case (L. Bero Citation2014, Bero and Grundy Citation2018; Rodwin Citation2017). Rodwin, for example, claimed that while intellectual interests may cause bias, this does not mean that they constitute a COI. This is because they do not fall within the original legal concept of COI, and including such interests would, Rodwin argues, “unmoor the concept from its original meaning and make it merely another phrase for bias” (Rodwin Citation2017, 74).

Bero argued that many non-financial influences (for example, a researcher’s training) were not a type of “secondary interest” and therefore, were not a COI (L. Bero Citation2014; Bero and Grundy Citation2018). Labelling non-financial interests or influences as COI was perceived to “ignore the reality that science is not value free” (L. Bero Citation2017) and to act as a type of “ethical shorthand” for other influences on research – such as institutional structures, political factors and issues related to diversity and representation (Bero and Grundy Citation2018; Grundy et al. Citation2020). While these influences were perceived to be significant, they were not considered a form of COI and were seen to require their own distinct management strategies (Bero and Grundy Citation2018; Grundy et al. Citation2020).

There is little evidence for nfCOI and their impact

Several articles emphasized that there was very little evidence for the nature and impact of non-financial COI on research, publication and clinical care (L. Bero Citation2014, Bero and Grundy Citation2018; Mintzes and Grundy Citation2018; Grundy, Mazzarello, and Bero Citation2020). Some pointed to the need for additional research to identify situations where non-financial influences were relevant (L. Bero Citation2014; Bero and Grundy Citation2018), whereas others used the lack of evidence to support calls for focusing attention on financial COI (Grundy, Mazzarello, and Bero Citation2020; Mintzes and Grundy Citation2018).

Financial COI are more problematic than nfCOI

Closely related to the above claim was the argument that financial COI are more problematic than non-financial interests, with numerous articles citing evidence that fCOI have an adverse impact on the integrity of research, publication processes and clinical care (L. A. Bero and Grundy Citation2016; Garattini, Padula, and Mannucci Citation2020; Goldberg Citation2020; Lenzer and Brownlee Citation2015; Mintzes and Grundy Citation2018). Articles making this claim tended to focus on the pharmaceutical industry and associated financial COI – noting that there is a significant body of research documenting the negative effects of industry sponsorship on all aspects of the research process (L. A. Bero and Grundy Citation2016; Lenzer and Brownlee Citation2015; Mintzes and Grundy Citation2018). Financial COI associated with industry were seen to be highly problematic because of the vast resources available to industry to influence researchers, policymakers and clinicians (Goldberg Citation2020; Lenzer and Brownlee Citation2015). Articles also claimed that industry-related financial COI were more problematic because they were unidirectional – consistently in favor of the commercial sponsor – whereas personal biases were multidirectional and likely to balance each other out over time (Lenzer and Brownlee Citation2015; Ludwig, Kushi, and Heymsfield Citation2018). The impact of fCOI was, therefore, perceived to be much more significant than that of nfCOI (L. A. Bero and Grundy Citation2016; Goldberg Citation2020; Lenzer and Brownlee Citation2015).

Perspectives regarding the management of non-financial COI

Attitudes toward the management of non-financial COI were similarly divided into two groups, with those articles that viewed non-financial COI as problematic likely to argue in favor of their management, and those that did not view non-financial COI as problematic likely to either argue against the need for their management or to suggest that alternative strategies were required for non-financial “interests or influences.”

nfCOI should be managed

Of those articles that viewed nfCOI as problematic and in need of management, numerous strategies were proposed. Before these management strategies are discussed, however, it is important to note that several articles in this category called for the need for a clearer definition of nfCOI and conflict of interest in general (Ancker and Flanagin Citation2007; Daou et al. Citation2018; Dunn et al. Citation2016; Kesselheim et al. Citation2012; D. Resnik Citation2023), and for the necessity of further research into nfCOI, their relationship with fCOI and their impact on research, publication, guideline development and clinical care (P. M. Editors Citation2008; Flier Citation2017; Klitzman Citation2011; Norris et al. Citation2011; Rosenberg Citation2017; Saitz Citation2013; Shawwa et al. Citation2016). This was seen to be important given the lack of evidence for the prevalence and impact of nfCOI, and to guide a more consistent approach to the management of COI in general (P. M. Editors Citation2008; Flier Citation2017; Klitzman Citation2011; Norris et al. Citation2011; Rosenberg Citation2017; Shawwa et al. Citation2016).

Disclosure

One of the most commonly suggested strategies for the management of nfCOI across all domains was disclosure. Some articles simply stated for the need for the disclosure of nfCOI (Bauchner, Fontanarosa, and Flanagin Citation2018; Biswas Citation2013; Borysowski, Lewis, and Górski Citation2021; Braillon Citation2018; Donaldson Citation2019; Fauser and Macklon Citation2019; D. Menkes Citation2018; D. B. Menkes et al. Citation2018; Munufo Citation2016; Sagner et al. Citation2016; Smith et al. Citation2009; Sollitto, Youngner, and Lederman Citation2002; H. C. Williams et al. Citation2006), whereas others provided more specific disclosure requirements (Fava Citation2010; Ghinea et al. Citation2020; Griebenow et al. Citation2015; Saper Citation2014; Shaw Citation2014; Smith and Blazeby Citation2018; Vieta Citation2007), such as the type of nfCOI to be disclosed – with religious beliefs (Smith and Blazeby Citation2018) and personal medical experiences specified (Shaw Citation2014). Others provided more explicit recommendations – Ghinea, for example outlining three criteria that should be met for a claim to be made that an individual’s personal beliefs should be declared (Ghinea et al. Citation2020). These included: 1) that the belief must generate an interest; 2) that the interest must be material; and 3) there must be a clear justification for declaring the material interest (Ghinea et al. Citation2020). This was to ensure that disclosure statements are relevant to the specific situation, to prevent lengthy “laundry lists” of irrelevant disclosures and to protect against potential discrimination (Ghinea et al. Citation2020).

Other articles agreed that while disclosure of nfCOI was important, it alone was insufficient as a management strategy (Johnson and Rogers Citation2014; Kesselheim and Maisel Citation2010; Nahai Citation2019; Shimazawa and Ikeda Citation2014; J. Williams et al. Citation2017). This was because disclosure alone was seen to do little to mitigate the effects of COI (both fCOI and nfCOI) (Horton Citation1997; Johnson and Rogers Citation2014; Rosenberg Citation2017). Furthermore, concerns were raised about moral licensing, whereby individuals become less objective and cautious following the disclosure of COI (Bernstein Citation2013; Nahai Citation2019; J. Williams et al. Citation2017), and the burden that disclosure places on patients to interpret COI declarations (Kesselheim and Maisel Citation2010; J. Williams et al. Citation2017). The criticism of disclosure was often followed by calls for strengthening other management strategies – such as for example, developing enforceable rules about the types of relationships permitted (J. Williams et al. Citation2017), and public reporting and regular institutional review of clinicians’ COI (Kesselheim and Maisel Citation2010).

Open discussion

Several articles suggested that open discussion about nfCOI was needed both to increase awareness of the issues associated with nfCOI (Clark et al. Citation2015; Leas and Umscheid Citation2016; Rosenberg Citation2017) and to reduce the stigma around COI in general (Horton Citation1997; Rosenberg Citation2017). Several authors noted that people may be deterred from disclosing of COI because the term “conflict of interest” is associated with negative connotations, unethical behavior and at times, even fraud (Horton Citation1997; Maj Citation2008; Rosenberg Citation2017). The stigma around COI was also seen to act as a deterrent for individuals to disclose either fCOI or nfCOI (Rosenberg Citation2017). In response, a number of authors suggested that it is important to non-pejoratively acknowledge the multiple directions in which researchers and clinicians could be pulled, and that this could both be facilitated by, and facilitate a culture of open discussion (Clark et al. Citation2015; Horton Citation1997; Leas and Umscheid Citation2016; Rosenberg Citation2017). Others called for greater awareness about non-financial COI in clinical settings (Maj Citation2008, Citation2009).

Reflexivity

Reflexivity, a tool borrowed from the social sciences, was perceived by several articles to be an important prerequisite for addressing non-financial COI (Clark et al. Citation2015; Gruppen et al. Citation2008; Marshall Citation1992; Montgomery and Weisman Citation2021; Nahai Citation2019). Reflexivity involves an awareness of one’s own subjectivity, preconceptions and biases and how they may influence one’s work and interpretation of others work (Clark et al. Citation2015). Interestingly, reflexivity was also raised as a potential management strategy for non-financial “interests or influences” by a number of articles who were critical of the term “non-financial COI” (L. A. Bero and Grundy Citation2016; Rivera and Panduro Citation2018). Bero, for example, a vocal critic of non-financial COI, who has frequently claimed that they “distract” from financial COI, emphasized that reflexivity was an important tool to manage non-financial interests or influences – providing a series of questions to prompt reflexivity in researchers (L. A. Bero and Grundy Citation2016). Most articles promoting reflexivity as a tool for managing non-financial interests were focused on the research domain and claimed that it was important for researchers to engage in personal reflection about the potential impact of their beliefs, values and preconceptions on their research (L. A. Bero and Grundy Citation2016; Clark et al. Citation2015; Gruppen et al. Citation2008; Nahai Citation2019). For the most part, this was seen to be the responsibility of the individual researcher, however, several articles called for the need for training in reflexivity throughout research programs (Clark et al. Citation2015) and the necessity of integrating reflexivity into institutional processes in order to ensure it is effective (L. A. Bero and Grundy Citation2016).

Management according to the severity of the COI

Several articles were in favor of tailoring management of COI (both fCOI and nfCOI) according to their severity – with “low-risk” or “minor” COI managed via disclosure, and “high-risk” or “major” COI managed via strategies such as recusal or exclusion (Akl et al. Citation2022; Jones et al. Citation2012; Ngo-Metzger et al. Citation2018; West Citation2009). West, for example, suggests a simple “traffic light” system for the management of COI in the research domain – with the “red” category indicating the most serious COI (such as funding from interested parties or religious beliefs), which require strong management strategies, while the “green” category denoted less serious COI (West Citation2009). Similarly, in the context of clinical guideline development, Jones claimed that the best way to approach COI is through proportionality, whereby COI management processes are calibrated according to risk (Jones et al. Citation2012). Simple disclosure was seen to be appropriate for low-risk COI, whereas limitation or exclusion was to be used for high-risk COI (Jones et al. Citation2012).

This kind of tailored approach was described in three articles from professional societies outlining their policies and procedures for the management of COI in clinical guideline development (Ngo-Metzger et al. Citation2018; Qaseem and Wilt Citation2019; Waters et al. Citation2020). COI disclosures were reviewed by a panel or committee chair, allocated into a category based on their severity ranging from low-level to high-level COI and then managed accordingly. This could range from no restrictions being imposed on those with low-level COI, whereas limitation of duties or recusal could be required by those with high-level COI (Ngo-Metzger et al. Citation2018; Qaseem and Wilt Citation2019; Waters et al. Citation2020). Importantly, articles were not uniform in how they allocated non-financial COI to categories – some allocated most nfCOI into the low-level category (Waters et al. Citation2020), whereas others allocated certain nfCOI to the high-level category (Ngo-Metzger et al. Citation2018; Qaseem and Wilt Citation2019).

Use of scientific methods

A small number of articles claimed that returning to the “foundational principles of science” would negate the risk of bias from nfCOI (Allison Citation2009; Brown et al. Citation2014; Caplan Citation2007, Citation2012; McKinney and Pierce Citation2017, 1727). McKinney, for example, claimed that science has long had the tools available to deal with the issues of bias, such as prospective peer review of research designs, and that these tools could help minimize bias from nfCOI (McKinney and Pierce Citation2017). Similarly, Caplan perceived rigorous peer review as the “antidote” to bias in the research domain (Caplan Citation2007, Citation2012). They claimed that the quality of peer review had slipped in recent years and that universities should be required to provide training on peer review as a way of minimizing COI (both fCOI and nfCOI) and that journals should publish anonymized reviews (Caplan Citation2007, Citation2012). Others called upon researchers to make their data available to other researchers, so that they can evaluate whether or not the conclusions made are reasonable (Allison Citation2009; Tsai Citation2011), along with the disclosure of non-financial interests to research participants (Sollitto, Youngner, and Lederman Citation2002).

Balancing competing interests

Some articles claimed that the process of “balancing” individuals’ interests (i.e., ensuring that there was a balance of different perspectives, values and experiences across individuals contributing to a group-based decision-making process) was an effective way of minimizing nfCOI (Viswanathan et al. Citation2014; Wang et al. Citation2018). This was seen to be particularly important in guideline development groups (Wang et al. Citation2018) and in the authorship groups of systematic reviews (Viswanathan et al. Citation2014).

Other management suggestions – registries and policies

Several articles suggested that a national electronic, open-access registry of health professionals’ and researchers’ financial and non-financial interests was an important part of managing nfCOI (Bion Citation2009; Dunn et al. Citation2016). Dunn et al. outlined five criteria to promote the growth and ensure the utility of a global public registry of researchers fCOI and nfCOI. These criteria included: a taxonomy (clear definitions of both financial and non-financial COI); enforceability (mandated by publishers, institutions, etc.); transparency (including an archive of any changes made to the registry); interoperability and automatic disclosures (i.e., the ability to generate COI declarations for use in journals) (Dunn et al. Citation2016).

A number of articles pointed to the need for clear and consistent policies on nfCOI (P. M. Editors Citation2008, Citation2009; Shimazawa and Ikeda Citation2014), or at the very least, for policies addressing COI to include nfCOI (Annane et al. Citation2019; Braillon Citation2018; Ngo-Metzger et al. Citation2018; Qaseem and Wilt Citation2019; Schunemann et al. Citation2015). The editors of PLoS Medicine, for example, emphasized the need for journals to provide clear policies that include definitions of non-financial COI and outline expectations for authors, reviewers and editors (P. M. Editors Citation2008). Several articles also noted the need for the enforcement of policies through regular monitoring of individuals compliance with policy requirements (Annane et al. Citation2019; Ngo-Metzger et al. Citation2018; Qaseem and Wilt Citation2019). Resnik recommended additional disclosures to the ICMJE form in the publication process – including the disclosure of direct research interests, direct professional interests, expert testimony and other litigation involvement, providing unpaid advice to non-government organizations, and personal or professional relationships (D. Resnik Citation2023). These disclosures are to be made by authors, reviewers and editors (D. Resnik Citation2023).

nfCOI cannot or should not be managed

Several different kinds of arguments were made for why nfCOI should not be managed, or at least not managed alongside financial COIs as types of conflicts of interest.

nfCOI are too broad and heterogenous to be managed

A commonly made argument was that non-financial COI are too broad and heterogenous to be readily identified and effectively managed (L. Bero Citation2014; Cook Citation2009; Garattini and Padula Citation2019; Garattini, Padula, and Mannucci Citation2020; Rodwin Citation2017; Thompson Citation1993). Some articles compared financial COI to non-financial COI – claiming that financial COI were far easier to identify and manage (Garattini and Padula Citation2019; Garattini, Padula, and Mannucci Citation2020; Lenzer and Brownlee Citation2015; Rodwin Citation2017; Thompson Citation1993), whereas non-financial COI were so widespread and varied that they were “potentially impossible to eradicate” (Garattini, Padula, and Mannucci Citation2020, 358).

Non-financial interests are not optional

Articles also frequently claimed that many non-financial interests, such as the desire for career advancement or recognition for one’s work, were intrinsic to an individual and could not be reduced or eliminated, whereas financial COI, as they were optional, could be effectively managed via elimination (L. Bero Citation2014; Kassirer and Angell Citation1993; Lenzer and Brownlee Citation2015; Robbins Citation2018; Rodwin Citation2017).

Non-financial interests are obvious

Some articles argued that non-financial interests are typically shared by all individuals, which nullifies the need for their disclosure (L. Bero Citation2014; Kassirer and Angell Citation1993; Lenzer and Brownlee Citation2015; Robbins Citation2018; Rodwin Citation2017).

Management of nfCOI is itself harmful

Attempts to manage nfCOI, and in particular, intellectual COI in the research domain, were perceived by some articles to be threat to science (Lenzer and Brownlee Citation2015). Several articles pointed out that it is neither possible or desirable for research to be value-free or for researchers to be completely objective (Cook Citation2009; Garattini and Padula Citation2019; Lenzer Citation2016; Rodwin Citation2017; Vincent, Christopher, and McLean Citation2018). Genuine scientific disagreement was seen to have been confused with intellectual COI (Lenzer Citation2016), with articles noting that scientific disagreement is a healthy part of the research endeavor that can lead to scientific advancement through robust debate (Cook Citation2009; Garattini, Padula, and Mannucci Citation2020; Lenzer Citation2016; Rodwin Citation2017). Certain non-financial interests were also seen to have a positive impact on the research process, with for example, strong beliefs seen to drive researchers’ curiosity and desire to conduct research (Cook Citation2009), and because diverse opinions enrich the research process (Garattini, Padula, and Mannucci Citation2020; Lenzer Citation2016; Rodwin Citation2017).

Management of nfCOI detracts from management of financial COI

Numerous articles claimed that attention to non-financial COIs detracts from attention to financial COI (L. Bero Citation2014; L. A. Bero and Grundy Citation2018, Citation2016; Garattini and Padula Citation2019; Garattini, Padula, and Mannucci Citation2020; Lenzer Citation2016; Lenzer and Brownlee Citation2015). Labelling personal beliefs, intellectual commitments or personal experiences as “COI” was seen to divert attention from financial COI and to “muddy the water” about how best to manage financial COI (L. Bero Citation2014; L. A. Bero and Grundy Citation2018, Citation2016). Garattini, for example, argued that requiring mandatory disclosure of nfCOI was confounding and distracted attention from the real issue of bias – financial COI (Garattini and Padula Citation2019; Garattini, Padula, and Mannucci Citation2020). Others claimed that allegations of nfCOI had been strategically utilized to undermine individuals or to exclude them from participation in important committee processes (such as the United States Food and Drug Administration Drug Advisory Committee), while including individuals with financial COI (Grundy, Mazzarello, and Bero Citation2020; Lenzer Citation2016).

nfCOI should not be managed using the same strategies as those used to manage financial COI

More specifically, some articles that were critical of the using the concept of COI to describe non-financial “interests or influences,” argued that the strategies used for fCOI should not be applied to non-financial influences. The strategies commonly used to manage fCOI, particularly disclosure or recusal, were seen to be inappropriate for the management of non-financial influences, such as social values, beliefs, relationships and personal experiences (Bero and Grundy Citation2018; L. A. Bero and Grundy Citation2016; Grundy Citation2021; Grundy, Mazzarello, and Bero Citation2020; Grundy et al. Citation2020). Bero, for example, argued that treating non-financial influences in the same way as financial COI obscures other significant influences on the scientific process – such as broader institutional factors and issues relating to lack of representation and diversity (Bero and Grundy Citation2018). Grundy, on the other hand, provided evidence that when policymakers apply similar principles to non-financial influences as to financial COI it led to the over-regulation of non-financial influences and under-regulation of fCOI (Citation2020). In several other articles, Grundy argued for the necessity of new conceptual tools to address non-financial influences such as personal beliefs, experiences and relationships (Grundy Citation2021; Grundy et al. Citation2020).

Numerous articles claimed that requiring the disclosure of non-financial interests or COI raises ethical issues, including privacy, discrimination, exclusion and marginalization concerns. (e.g L. Bero Citation2017; Cook Citation2009; Garattini and Padula Citation2019; Garattini, Padula, and Mannucci Citation2020; Grundy Citation2021; Grundy, Mazzarello, and Bero Citation2020; Grundy et al. Citation2020). As non-financial interests were perceived to be intrinsic to an individual, concerns were raised that requiring their disclosure could violate the individual’s privacy and place them at risk of discrimination (L. Bero Citation2017; Cook Citation2009; Garattini and Padula Citation2019; Garattini, Padula, and Mannucci Citation2020). This was seen to be particularly problematic for individuals who belonged to minority or marginalized groups and who could be subjected to further marginalization if required to disclose their personal beliefs or experiences (Grundy Citation2021; Grundy et al. Citation2020).

Discussion

This scoping review provides a comprehensive overview of how non-financial COI have been defined and evaluated, and the strategies that have been suggested for their management in health-related and biomedical journals.

The definition of COI and in particular, non-financial COI remains contested. This is, in part, due to opposing views as to whether the term “conflict of interest” should be used to describe non-financial interests (L. A. Bero and Grundy Citation2016; Grundy Citation2021; Grundy et al. Citation2020; Rodwin Citation2017), as well as ambiguity around associated terms including influence and bias (Abdoul et al. Citation2012; Allison Citation2009; Shaw Citation2014). Despite disagreement about how nfCOI should be defined, articles broadly focused on five types of nfCOI:

Belief or viewpoint-based COI: moral, political, philosophical, ideological, or religious views.

Career-related COI: the desire for professional recognition or career advancement, institutional pressures or loyalties, affiliation with a specialty or commitment to a specific methodology.

Interpersonal COI: personal and professional relationships, institutional relationships, friendships and rivalries.

Research-related COI: receiving grants, publishing in high-impact journals, proving a hypothesis, fulfilling academic requirements, receiving rewards or recognition.

Status-related COI: the desire for status, prestige, and respect.

With the exception of articles that adopted a neutral approach, perspectives toward nfCOI were divided into two opposing groups. Articles in the first group argued that nfCOI are problematic and therefore require some form of management. Articles in the second group tended to adopt one of two core claims: either that nfCOI are not problematic and don’t require management, or that non-financial influences are not conflicts of interest nor should they be managed as such. Those who claimed the latter occasionally suggested alternative ways of managing non-financial influences.

Of articles that claimed that nfCOI were problematic and require management, five strategies were frequently suggested. These included: open discussion, disclosure, reflexivity, management according to the severity of the nfCOI (e.g., disclosure for low-risk COI and recusal for high-risk COI) and use of scientific methods. Less commonly suggested management strategies included the use of registries, improving COI policies and “balancing” interests.

Despite at times polemic debate about the definition and management of nfCOI, many articles agreed that further research is required to determine the nature, impact and mitigation of nfCOI in the research and publication processes, education, clinical care and policy development. Several articles emphasized the need for clear and consistent terminology, including operational definitions. Others noted the lack of evidence for the prevalence and impact of nfCOI and need for further investigation into these areas. Additional research was also seen to be necessary to determine what types of nfCOI require management, and to evaluate and improve existing management strategies.

It is beyond the scope of this review to consider the merits of the recommendations made by different authors for the management of nfCOI. We suggest, however, that the recommendations made in the literature may provide a useful starting point for developing systematic approaches to the management of nfCOI. Akl and colleagues, for example, for example, address some of these issues by presenting a comprehensive framework that defines and categorizes COI and facilitates the assessment of COI in health research (Akl et al. Citation2022). Based on a literature review, series of methodological studies and expert review, Akl et al. developed a definition of COI and an approach for assessing whether an interest qualifies as a COI:

A COI exists when a past, current, or expected interest creates a significant risk of inappropriately influencing an individual’s judgment, decision or action when carrying out a specific duty. (Akl et al. Citation2022, 238)

Although limited to the research domain and yet to undergo a feasibility evaluation and validation, Akl et al.’s definition and approach offers several advantages. First, both non-financial and financial interests are clearly categorized and seen to have the potential to give rise to a COI (Citation2022). Second, it is the relevance, nature, magnitude and recency of an interest in relation to an individual’s specific duty that creates a COI. Focusing on these factors should ensure that disclosures made are relevant, therefore, avoiding lengthy “laundry list” disclosures, which have been the subject of some criticism (Ghinea et al. Citation2020). Finally, the management of COI is linke d to the risk that it may inappropriately influence an individual’s decision-making process or behavior, with authors suggesting that different management strategies are required for low risk versus high-risk COI (Akl et al. Citation2022). While further research, particularly into the prevalence, impact, and management of nfCOI is necessary, this framework offers a clear operational definition and taxonomy of interests, and a practical method for assessing the risk of COI (Akl et al. Citation2022).

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this review include its novelty and that it was carried out in a systematic and rigorous way, drawing together and synthesizing research on nfCOI in health-related journals. The ongoing disagreement about nfCOI in medicine is well-known (D. Resnik Citation2023), however, this review is the first to clearly and systematically document different perspectives toward the definition of nfCOI and their management.

There are several limitations to this review including that due to time constraints it did not include gray literature or articles published in a language other than English. This may have meant that important perspectives were missed. Furthermore, consultation with key stakeholders is recommended in some scoping review methodologies (Arksey and O’Malley Citation2005), however, this was beyond the purview of this review. It is also important to acknowledge that the authors of this review have argued previously that nfCOI are problematic and require management (indeed, this could be considered a nfCOI), however, as this is a descriptive article that draws its own conclusions this is unlikely to have distorted the review (Wiersma, Kerridge, and Lipworth Citation2018, Citation2020).

Finally, there was a significant difference between the number of articles that argued in favor of managing nfCOI versus those that explicitly stated that they should not be managed. This may reflect the fact that those who view a phenomenon as problematic are more likely to write about it than those who are content with the status quo.

Conclusion

This scoping review has provided an overview of how nfCOI are defined and evaluated, and the strategies that have been suggested for their management in the health-related literature. This review also provided a comprehensive analysis of the criticisms of the concept of nfCOI, and of attempts to manage nfCOIs alongside fCOIs. It is clear there is a need for more rigorous empirical research and theoretical analysis to better understand their prevalence and impact and to devise optimal management strategies.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (613.1 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ms Bernadette Carr (Academic Liaison Librarian at the University of Sydney) for her assistance with developing the database search strategies for this scoping review.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest. While the authors have a scholarly interest in the topic of non-financial conflicts of interest and have published previously on the topic, which is arguably a type of non-financial conflict of interest, we take the position that intellectual commitments such as these do not generally need to be declared as conflicts of interest in publications.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2024.2337046.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abbas, M., D. Pires, A. Peters, C. Morel, S. Hurst, H. Holmes, H. Saito, B. Allegranzi, J. Lucet, W. Zingg, S. Harbarth, and D. Pittet. 2018. “Conflicts of Interest in Infection Prevention and Control Research: No Smoke without Fire. A Narrative Review.” Intensive Care Medicine 44 (10): 1679–1690. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-018-5361-z.

- Abdoul, H., C. Perrey, F. Tubach, P. Amiel, I. Durand-Zaleski, and C. Alberti. 2012. “Non-Financial Conflicts of Interest in Academic Grant Evaluation: A Qualitative Study of Multiple Stakeholders in France.” PLoS One 7 (4): e35247. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035247.

- Akl, E. A., P. El-Hachem, H. Abou-Haidar, I. Neumann, H. J. Schunemann, and G. H. Guyatt. 2014. “Considering Intellectual, in Addition to Financial, Conflicts of Interest Proved Important in a Clinical Practice Guideline: A Descriptive Study.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 67 (11): 1222–1228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.05.006.

- Akl, E. A., M. Hakoum, A. Khamis, J. Khabsa, M. Vassar, and G. Guyatt. 2022. “A Framework is Proposed for Defining, Categorizing, and Assessing Conflicts of Interest in Health Research.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 149:236–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.06.001.

- Akl, E. A., R. Karl, and G. H. Guyatt. 2012. “Methodologists and Context Experts Disagreed Regarding Managing Conflicts of Interest of Clinical Practice Guidelines Panels.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 65 (7): 734–739. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.12.013.

- Alexander, P., R. J. S. Gionfriddo, I. Neumann, J. P. Brito, B. Djulbegovic, V. M. Montori, H. J. Schunemann, and G. H. Guyatt. 2016. “Senior GRADE Methodologists Encounter Challenges as Part of WHO Guideline Development Panels: An Inductive Content Analysis.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 70:123–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.09.003.

- Allison, D. B. 2009. “The Antidote to Bias in Research.” Science 326 (5952): 522–523. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.326_522b.

- American College of Emergency Physicians. 2017. “Conflict of Interest.” Annals of Emergency Medicine 70 (1): 3.

- Ancker, J. S., and A. Flanagin. 2007. “A Comparison of Conflict of Interest Policies at Peer-Reviewed Journals in Different Scientific Disciplines.” Science and Engineering Ethics 1 (2): 147–157.

- Annane, D., and B. Chapentier. 2018. “Do I have a Conflict of Interest? Yes.” Intensive Care Medicine 44 (3): 1741–1743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-018-5285-7.

- Annane, D., N. Lerolle, S. Meuris, J. Sibilla, and K. M. Olsen. 2019. “Academic Conflict of Interest.” Intensive Care Medicine 45 (1): 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-018-5458-4.

- Anstey, A. 2015. “Conflicts and Heuristics in Dermatology: Time to Ask Ourselves, ‘What Might I do in this Situation?” The British Journal of Dermatology 173 (3): 631–632. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.14060.

- Arksey, H., and L. O’Malley. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1): 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Babor, T., and P. Miller. 2014. “McCarthyism, Conflict of Interest and Addiction’s New Transparency Declaration Procedures.” Addiction 109 (3): 341–344. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12384.

- Bauchner, H., P. Fontanarosa, and A. Flanagin. 2018. “Conflicts of Interests, Authors, and Journals: New Challenges for a Persistent Problem.” JAMA 320 (22): 4.

- Bernstein, J. 2013. “Everyone (Else) Is Conflicted.” Clin Orthop Relat Res 471 (8): 2434–2438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-013-3071-y.

- Bero, L. 2014. “What is in a Name? Nonfinancial Influences on the Outcomes of Systematic Reviews and Guidelines.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 67 (11): 1239–1241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.06.015.

- Bero, L. 2017. “Addressing Bias and Conflict of Interest Among Biomedical Researchers.” JAMA 317 (17): 2.

- Bero, L. A., and Q. Grundy. 2016. “Why Having a (Nonfinancial) Interest is not a Conflict of Interest.” PLoS Biology 14 (12). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2001221.

- Bero, L., and Q. Grundy. 2018. “Not All Influences on Science are Conflicts of Interest.” American Journal of Public Health 108 (5): 632–633. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304334.

- Bion, J. 2009. “Financial and Intellectual Conflicts of Interest: Confusion and Clarity.” Current Opinion in Critical Care 15 (6): 583–590. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCC.0b013e328332f53a.

- Biswas, T. 2013. “Understanding Non-Financial Conflicts of Interest.” Indian Pediatrics 50 (3): 347–348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13312-013-0082-4.

- Borysowski, J., A. Lewis, and A. Górski. 2021. “Conflicts of Interest in Oncology Expanded Access Studies.” International Journal of Cancer 149 (10): 1809–1816. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.33733.

- Bosch, X., J. Pericas, C. Hernández, and P. Doti. 2013. “Financial, Nonfinancial and editors’ Conflicts of Interest in High‐Impact Biomedical Journals.” European Journal of Clinical Investigation 43 (7): 660–667. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.12090.

- Bou-Karroum, L., M. B. Hakoum, M. Z. Hammoud, A. M. Khamis, M. Al-Gibbawi, S. Badour, D. Justina Hasbani, L. Lopes, H. El-Rayess, F. El-Jardali, G. Guyatt, and E. Akl. 2018. “Reporting of Financial and Non-Financial Conflicts of Interest in Systematic Reviews on Health Policy and Systems Research: A Cross Sectional Survey.” International Journal of Health Policy and Management 7 (8): 711–717. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2017.146.

- Boyd, E., E. A. Akl, M. Baumann, J. R. Curtis, M. J. Field, R. Jaeschke, M. Osborne, H. J. Schunemann, and Ats Ers Ad Hoc Committee on Integrating, and Copd Guideline Development Coordinating Efforts in. 2012. “Guideline Funding and Conflicts of Interest: Article 4 in Integrating and Coordinating Efforts in COPD Guideline Development. An Official ATS/ERS Workshop Report.” Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society 9 (5): 234–242. https://doi.org/10.1513/pats.201208-057ST.

- Braillon, A. 2018. “Non-Financial Conflicts of Interest: Moving Forward!” Accountability in Research 25 (5): 310. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2018.1476144.

- Brody, H. 2010. “Professional Medical Organizations and Commercial Conflicts of Interest: Ethical Issues.” Annals of Family Medicine 8 (4): 354–358. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1140.

- Brody, H. 2011. “Clarifying Conflict of Interest.” The American Journal of Bioethics 11 (1): 23–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2010.534530.

- Brown, A., J. Ioannidis, C. Cope, D. Bier, and D. Allison. 2014. “Unscientific Beliefs About Scientific Topics in Nutrition.” Advances in Nutrition 5 (5): 3. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.114.006577.

- Caplan, A. 2007. “Halfway There: The Struggle to Manage Conflicts of Interest.” Journal of Clinical Investigation 117 (3): 2.

- Caplan, A. 2012. “Is Industry Money the Root of All Conflicts of Interets in Biomedical Research?” Annals of Emergency Medicine 59 (2): 2.

- Charmaz, K. 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory: APractical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. Great Britain: Sage Publications Ltd.

- Cherla, D. C., O. Viso, A. Olavarria, K. Bernardi, J. Holihan, K. Mueck, J. Flores-Gonzalez, M. Liang, and S. Adams. 2018. “The Impact of Financial Conflict of Interest on Surgical Research: An Observational Study of Published Manuscripts.” World Journal of Surgery 42 (9): 2757–2762. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-018-4532-y.

- Chimonas, S., M. Mamoor, S. A. Zimbalist, B. Barrow, P. B. Bach, and D. Korenstein. 2021. “Mapping Conflict of Interests: Scoping Review.” BMJ-British Medical Journal 375. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2021-066576.

- Citrome, L. 2015. “Conflicts of Interest: A Matter of Transparency.” International Journal of Clinical Practice 69 (3): 267–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.12638.

- Clark, A., A. Choby, K. Ainsworth, and D. Thompson. 2015. “Addressing Conflict of Interest in Non-Pharmacological Research.” International Journal of Clinical Practice 69 (3): 3.

- Cohen, J. 2001. “Trust us to Make a Difference: Ensuring Confidence in the Integrity of Clinical Research.” Academic Medicine 76 (2): 7.

- Colquhoun, H. K. C., K. W. Eva, J. M. Grimshaw, N. Ivers, S. Michie, A. Sales, and J. C. Brehaut. 2017. “Advancing the Literature on Designing Audit and Feedback Interventions: Identifying Theory-Informed Hypotheses.” Implementation Science 12 (1): 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0646-0.

- Cook, C. 2009. “Perspectives of Beliefs and Values Are Not Conflicts of Interest.” Addiction 105 (4): 760–761. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02921.

- Daou, K. N., M. B. Hakoum, A. M. Khamis, L. Bou-Karroum, A. Ali, J. R. Habib, A. T. Semaan, G. Guyatt, and E. A. Akl. 2018. “Public Health journals’ Requirements for Authors to Disclose Funding and Conflicts of Interest: A Cross-Sectional Study.” BMC Public Health 18 (1): 533. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5456-z.

- da Silva, J., J. Dobranszki, R. Bhar, and C. Mehlman. 2019. “Editors should Declare Conflicts of Interest.” Journal of Bioethical Inquiry 16:19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-019-09908-2.

- Dellinger, R., and C. Durbin. 2007. “Reply Letter.” Critical Care Medicine 35 (11): 2.

- Detsky, A. 2006. “Sources of Bias for Authors of Clinical Practice Guidelines.” CMAJ 175 (9): 1.

- DiRisio, A. C., I. S. Muskens, D. J. Cote, M. Babu, W. B. Gormley, T. R. Smith, W. A. Moojen, and M. L. Broekman. 2019. “Oversight and Ethical Regulation of Conflicts of Interest in Neurosurgery in the United States.” Neurosurgery 84 (2): 305–312. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyy227.

- Donaldson, C. M. 2019. “Conflict of Interest Blind Spots in Emergency Medicine: Ideological and Financial Conflicts of Interest in the Gender Bias Literature.” Academic Emergency Medicine 26 (11): 1300–1302. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.13829.

- Dunn, A., E. Coiera, K. Mandl, and F. Bourgeois. 2016. “Conflict of Interest Disclosure in Biomedical Research: A Review of Current Practices, Biases, and the Role of Public Registries in Improving Transparency.” Research Integrity and Peer Review 1 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-016-0006-7.

- Durbin, C. 2008. “When does a Point of View Become an Intellectual Conflict of Interest? Author’s Reply.” Critical Care Medicine 36 (5): 1688. author reply 1688–1689. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e318171045d.

- Editors, N. 2018. “Outside interests.” Nature 554 (7690): 1.

- Editors, P. M. 2008. “Making Sense of Non-Financial Competing Interests.” PLoS Medicine 5 (9): e199. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0050199.

- Editors, P. M. 2009. “An Unbiased Scientific Record Should Be everyone’s Agenda.” PLoS Medicine 6 (2): e1000038. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000038.

- El Moheb, M., B. S. Karam, L. Assi, M. Armache, A. M. Khamis, and E. A. Akl. 2021. “The Policies for the Disclosure of Funding and Conflict of Interest in Surgery Journals: A Cross-Sectional Survey.” World Journal of Surgery 45 (1): 97–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-020-05771-0.

- Epstein, R. A. 2007. “Conflicts of Interest in Health Care: Who Guards the Guardians?” Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 50 (1): 72–88. https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.2007.0002.

- Etzel, R., P. G. Szilagyi, W. Cooper, B. P. Dreyer, C. B. Forrest, D. P. McCormick, J. Serwint, et al. 2005. “Ambulatory Pediatric Association Policy Statement: Ensuring Integrity for Research with Children.” Ambulatory Pediatrics Association Research Committee (2003-2004) 5 (1): 3–5. https://doi.org/10.1367/1539-4409(2005)5<3:APAPSE>2.0.CO;2.

- Fauser, B. C. J. M., and N. S. Macklon. 2019. “May the Colleague Who Truly Has No Conflict of Interest Now Please Stand Up!” Reproductive BioMedicine Online 39 (4): 541–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2019.09.001.

- Fava, G. 2010. “Unmasking Special Interest Groups: The Key to Addressing Conflicts of Interest in Medicine.” Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics 79 (4): 6. https://doi.org/10.1159/000313688.

- Flier, J. 2017. “Conflict of Interest Among Medical School Faculty Achieving a Coherent and Objective Approach.” JAMA 317 (17): 2.

- Galea, S. 2018. “A Typology of Nonfinancial Conflict in Population Health Research.” American Journal of Public Health 108 (5): 631–632. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304333.

- Garattini, L., and A. Padula. 2019. “Conflicts of Interest Disclosure: Striking a Balance.” The European Journal of Health Economics 20:4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-018-1028-.

- Garattini, L., A. Padula, and P. M. Mannucci. 2020. “Conflicts of Interest in Medicine: A Never-Ending Story.” Internal and Emergency Medicine 15 (3): 357–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-020-02293-4.

- Gasparyan, A. Y., L. Ayvazyan, N. A. Akazhanov, and G. D. Kitas. 2013. “Conflicts of Interest in Biomedical Publications: Considerations for Authors, Peer Reviewers, and Editors.” Croatian Medical Journal 54 (6): 600–608. https://doi.org/10.3325/cmj.2013.54.600.

- Geiderman, J. M., K. V. Iserson, C. A. Marco, J. Jesus, and A. Venkat. 2017. “Conflicts of Interest in Emergency Medicine.” Academic Emergency Medicine 24 (12): 1517–1526. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.13253.

- Ghinea, N., M. Wiersma, I. Kerridge, and W. Lipworth. 2020. “Are My Religious Beliefs anyone’s Business? A Framework for Declarations in Health and Biomedicine.” Journal of Medical Ethics 27:27. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2020-106087.

- Gjersvik, P. 2015. “Conflicts of Interest in Medical Publishing: It’s All About Trustworthiness.” The British Journal of Dermatology 173 (5): 1255–1257. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.14157.