ABSTRACT

This essay details research into feminist digital activism in the Australian context through analysing the themes that emerged from the Teach Us Consent website. It provides a preliminary analysis of its contents as a means to continue and deepen the conversation around issues of gender, consent, and the education system. It also examines the difficulties and potentials of this digital type of feminist activism and research while highlighting the importance of technology as a ‘testimonial space’ [Gilmore 2017. Tainted Witness: Why We Doubt What Women Say About Their Lives. New York: Columbia University Press, 159].

Introduction

While the #MeToo movement can trace its origins to Tarana Burke's activism in 2006 (Citation2021), and the later imbroglio involving Harvey Weinstein – among others, in Australia, our #MeToo moment (or rather, moments) of women speaking publicly about their experiences of sexual violence and predation by powerful men can be traced to a series of recent controversies. For example, in January 2021 sexual assault survivor and activist, Grace Tame was named Australian of the Year and spoke passionately in public debates regarding sexual assault, domestic violence, and sexual harassment at work. In the intense period of the week beginning 15 March 2021 hundreds of thousands of Australian women and their supporters rallied to ‘march4justice’ on State and Federal Parliament Houses shouting ‘Enough!’ Just prior to this time when the Australian parliament became the focus of sexual assault and harassment allegations,Footnote1 the Teach Us Consent petition and website https://www.teachusconsent.com/ – which documented high school girls’ stories of rape and assault and our primary concern in this discussion – was launched. Indeed, 2021 can be considered a watershed for Australia in the public visibility given to the sexual assault and harassment of women and girls, suggesting the disgraceful extent of the problem, the poor attempts at redress and understanding by masculinist politicians and institutions, and the widespread public engagement with issues once seen as marginal and/or only relevant to feminists and victim-survivors.

This essay details our research into one element of this heightened visibility of gendered violence – the Teach Us Consent website and petition. It provides a preliminary analysis of its contents to continue and deepen the conversation around issues of gender, consent, and the education system. It also examines the difficulties and potentials of this digital type of feminist activism and research while highlighting the importance of technology as a ‘testimonial space’ (Gilmore Citation2017, 159). Our research project was motivated by the overwhelming sense that Australia had entered into a critical moment in gender relations. We noticed the rapid and massive support garnered for the Teach Us Consent website, and as feminist university teachers working in sites where issues of consent and sexual assault have long been a problem for young women, we felt it was our response-ability to pay attention and listen. When we speak of response-ability we speak of a place ‘where emotions become entangled with experience and epistemology so that all and everything we have left is our response-ability’ (Mackinlay Citation2015, 1438). Further, despite claims that we are now living in a ‘postfeminist’ moment (Gill Citation2007; Henderson and Taylor Citation2020; McRobbie Citation2009), and following more than half a century of feminists challenging rape culture, harassment, and sexual violence (Mendes, Ringrose, and Keller Citation2019), the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (Citation2022) reports that 1 in 5 women have experienced sexual violence since the age of 15, 85% of Australian women have been sexually harassed, and 1 in 6 women have experienced stalking since the age of 15.

In this discussion, we first provide a brief history of the Teach Us Consent petition and website, and provide a brief summary of literature relevant to consent education in Australia. Next, we outline the research project which gave rise to this exploration, paying attention to the overarching agenda we have related to consent education in university residential colleges and the feminist theoretical and methodological approaches that underpin our work. We then highlight some of the obstacles faced in research of this kind which explicitly takes up the sensitive topic of girls, young women, violence, and consent, and move on to share some of the preliminary findings of our analysis. We conclude with reflection on the insights we have gained from our engagement with the content of the Teach Us Consent testimonies as a form of digital activism and the ways we might put these to work in our academic research in the context of consent education in university residential colleges.

Introducing ‘Teach Us Consent’

The Australian-based Teach Us Consent movement was initiated by former Kambala SchoolFootnote2 student, Chanel Contos’ call for young women and girls to share their experiences of sexual assault at school on the Teach Us Consent website, and her associated petition to provide ‘holistic consent and sexuality education’ (www.teachusconsent.com.au) at schools. As the website uncompromisingly puts it: ‘Teach us to demolish rape culture’. During a late-night conversation about sexual assault while in high school, Contos and her friends reflected on the negative impact of their experiences on their lives today and lamented, ‘Do they even know they did this to us?’Footnote3 Hours later Contos used Instagram to ask her followers, ‘If you live in Sydney: have you or has anyone close to you ever experienced sexual assault from someone who went to an all-boys school?’ ‘Within 24 hours, over 200 people replied “yes”’ (www.teachusconsent.com.au). A website where women and girls could submit their stories of sexual assault and a petition soon followed. At the time of writing, the Teach Us Consent website states that it has received more than 44,000 signatures on the petition and over 6700 testimonies.

Chanel Contos's Instagram petition is an example of new digital feminist activism which highlights not only how often the voices and lived bodily experiences of young women are silenced, but also how women's voices can be activated through such activism. After years of erasure and silencing, technology is providing young women with what Gilmore terms a ‘testimonial space’ (Citation2017, 159), that is a public space of politics, a space that replicates the concept of the public square where their embodied accounts of everyday sexism and sexual assault are pervasive and stored. Moreover, the creation of remedies is dependent on the voices of these girls and young women being heard.

The ‘Teach Us Consent’ petition resulting from the Instagram poll shed light on the ways in which consent education is addressed in Australian schools – and policy makers, administrators, teachers and researchers in education started to tune in and turn up the conversation. However, it is important to note that there is a significant body of literature in Australia which document curricula and approaches including pedagogic resources which have been available for gender equality and justice work in schools (including in relation to consent) for decades. Amanda Keddie (Citation2023), for example, notes the important work of Martino and Pallotta-Chiarolli (Citation2005) and their work assisting teachers to educate about dominant gender norms and specifically the work of leading gender justice education scholar Debbie Ollis and the development of Victoria's Building Respectful Relationships: Stepping Out Against Gender-Based Violence (Citation2018).

The Australian literature on curricula and approaches to sexuality education, gendered violence education, and consent education is often housed under the umbrella term 'respectful relationships education' (Kearney et al. Citation2016, 19). Recognizing that schools operate as ‘mini-communities’ where gender ‘respect and equality can be modelled’ (Kearney et al. Citation2016, 4), in 2015 the government, through the Australian curriculum, directed schools to consider their role in the prevention of gender-based violence through the Respectful Relationships Education in Schools (RREiS) pilot. The 2016 report on the RREiS pilot highlighted that while it is possible to significantly improve knowledge, attitudes and skills amongst staff and students in relation to gender-based violence, success is dependent on whether or not school and education systems and cultures are prepared to ‘walk the talk’ of gender equality and respect beyond a curriculum document (Kearney et al. Citation2016, 16). The curriculum resource Building Respectful Relationships: Stepping Out Against Gender-Based Violence developed by Debbie Ollis is now used across schools in Victoria to promote seven elements necessary for effective practice and change: addressing the drivers of gender-based violence; having a long-term vision, approach and funding; taking a whole school approach; establishing mechanisms for collaboration and coordinated effort; ensuring integrated evaluation and continual improvement; providing resources and support for teachers; and, using age-appropriate interactive and participatory curriculum (Kearney et al. Citation2016, 19). While this suite of resources and reports is not directly linked to the Contos petition, as Keddie and Ollis (Citation2019, Citation2021) and Ollis et al. (Citation2022) point out, the change agenda established by the Respectful Relationships Education pilot in 2015 for inclusion of gender-based violence education in Australian schools cannot be underestimated. In 2022 state and territory education ministers, along with the (then) federal education minister agreed and announced they would move to make consent education compulsory in all Australian schools (ACARA Citation2022b; Maunder Citation2022), and in the newest version of the Australian curriculum (Version 9.0), it resides in the Health and Physical Education (HPE) syllabus (ACARA Citation2022a). Prior to the announcement, some jurisdictions, such as Victoria, had already begun to produce a significant focus on consent education through the Resilience, Rights and Respectful Relationships learning materials (Cahill and Dadvand Citation2021), and while mandatory inclusion of consent education in schools across Australia is generally viewed as positive, questions regarding how consent will be taught, when it should be taught and who should be taught about consent, remain. There is still much work to be done to implement, monitor and evaluate the short and long-term impact of Respectful Relationships Education in Australian schools – Victoria and Queensland are in the process of piloting what appears to be a successful respectful relationships education for the primary years (Our Watch Citation2021) and in 2022, the Australian Human Rights Commission was charged with conducting a national survey to ascertain the extent of secondary students’ knowledge and understanding of consent and consent education (Citation2022).

As an interdisciplinary team of five Gender Studies scholars spanning across education, literature, feminist and cultural studies, and media and communication then, we feel it is our response-ability to respond to the urgent questions raised by the Teach Us Consent statements. Although this is not the first online archive collecting the experiences of sexual assault survivors – previous examples include the Everyday Sexism Project (Citationn.d.), which collected day-to-day experiences of sexism, and Everyone’s Invited (Citation2020), a collection of over 50,000 testimonies from survivors, alongside lists of the schools and universities mentioned in the testimonies – the Teach Us Consent archive is unique in the Australian context, and in its clear call for schools and education systems to act. Without doubt, Teach Us Consent is an extensive and historically significant dataset with troubling layers of effect and affect that seem to become even more troubled the closer and closer we look. Our intention in this essay is to provide a preliminary slice of some of the insights shared from girls and young women about the lived bodily experiences of consent, sexual harassment, assault, and violence shared in the online campaign and what they are telling us about the kind of consent education being called for.

Positioning ourselves to listen: our research approach

The ‘we’ who write this paper are five Gender Studies scholars based at The University of Queensland and Southern Cross University. Our analysis of the Teach Us Consent testimonies is funded by The University of Queensland's Vice-Chancellor's Strategic Fund, and forms part of a larger university interdisciplinary 12-month research initiative into sexual assault, gender violence, and consent in Australia. That we have been given this financial support suggests that a number of Australian universities realize that the incidents of sexual assault described in Teach Us Consent are not exclusive to secondary schools and flow into experiences on university campuses, and particularly in university residential colleges. Witness the Universities Australia's continuing initiative Respect. Now. Always, which aims to ‘prevent sexual violence in university communities and improve how universities respond to and support those who have been affected’ (Citation2016). Coinciding with the release and screening of The Hunting Ground documentary on rape on US campuses, in 2016 Universities Australia commenced its Respect. Now. Always initiative to prevent sexual violence in university settings and to improve responses and support. This initiative was the result of student activism and surveys over the years highlighting women students’ lack of safety on campus and in residential colleges. Subsequent to this, in 2017, the Australian Human Rights Commission released its report Change the Course: National Report on Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment at Australian Universities. It represented 39 universities and more than 30,000 students and found that one in five students were sexually harassed in university settings. Further, in 2018 End Rape on Campus (EROC) released the Red Zone Report during O-week to draw attention to the spike in rates of sexual assault that occur during this one week – research found that 1 in 8 sexual assaults at the University of Sydney colleges happen during a single week of the year.

Yet, despite this research work change in attitudes and experiences appears to be barely moving. In March 2022, the National Student Safety Survey (Universities Australia and Social Research Centre) released the most recent data on safety and well-being on university campuses. Of the almost 44,000 students who participated, 1 in 6 had experienced sexual harassment since starting university, while 1 in 20 had experienced sexual assault. Of the assaults, more than 25% occurred in student accommodation or residences. Together, these reports highlight that finding more effective ways to educate on sexual harassment, sexual assault, sexual violence, and consent in these locations is an urgent matter.

On female body experience: a methodology

Our over-arching approach to understanding the experiences of sexual assault, violence and consent detailed in the petition statements is explicitly feminist, corporeal, and phenomenological. We are committed to feminist research practice that ‘begins with understanding that human experience is embodied, inter-subjective, and contingent, and woven into personal and cultural webs of signification’ (Simms and Stawarska Citation2013, 12). In focussing on lived bodily experience we ground our work in the feminist philosophy and phenomenology developed by Simone de Beauvoir (‘One is not born but rather becomes woman’) ([1949] Citation2011, 293), Edith Stein (‘The children in school … do not need merely what we have but rather what we are’) ([1959] Citation2017, 6) and perhaps most notably, Iris Marion Young (‘A woman experiences her body as a thing as well as a capacity’) (Citation2005, 35). Broadly speaking phenomenology looks to understand ‘life as we live it, as it is’ (Van Manen Citation2016, 39) and feminist phenomenology seeks to turn-up the volume on ‘life as we live it, as it is’ through the situated and intercorporeal-subjectivity of a becoming body and the social and political lenses of gender. Our feminist phenomenological approach adopts an ‘evocative’ method (Van Manen Citation2016, 249) for deriving meaning from the ‘experiential narratives’ shared by girls and young women on the Teach Us Consent digital archive of the ‘lived thoroughness’ of sexual assault and violence. The evocative phenomenological methods make it possible for us to draw near to the text and let the text ‘speak to us’ and ‘reverberate with meanings’ that demand we pay attention. Feminist phenomenology thus goes some way to address the flattening effects of digital culture on subjectivity, and the depersonalizing outcomes of big data research.

In doing so, we also build on feminist phenomenological and philosophical understandings of sexual violence. Drawing on Beauvoir, feminist phenomenology by scholars like Megan Burke and Fiona Vera-Grey demonstrates how the threat of sexual violence and its realization are woven into women's everyday lived experiences. Burke uses a metaphor of haunting to argue that the threat of sexual violence characterizes the temporality of feminine existence – women are ‘haunted by rape’ (Citation2019, 106) in that the threat of rape is always a ‘possibility that it is yet to come’ (Citation2019, 114). Vera-Grey's work, on the other hand, explores what she terms a continuum of sexual violence, which describes ‘what is lived by women as an experiential continuum of men's intrusive practices’ (Citation2017, p. 21), from more ordinary interruptions like catcalls to experiences of violence. In working with survivor testimonies that range from more everyday violations of consent to violent sexual assaults, continuum thinking may allow us to draw connections between very different experiences across the dataset.

Furthermore, we look to the analysis of first-person accounts of rape survival by academics and philosophers, particularly Linda Alcoff and Susan Brison, when thinking about the harm of sexual violence. Alcoff argues that one of the primary harms of sexual violence to persons is to their sexual subjectivity: ‘our capacity to have sexual agency in our lives’ (Citation2018, 111). Thus, sexual violence inhibits ‘the very possibility of sexual self-making’ (Citation2018, 145). These comments are echoed by Brison, whose first-person account of surviving sexual violence emphasizes the embodied dimensions of trauma and its radical challenge to stable conceptions of the self, and points to the importance of narratives in healing from trauma. Brison particularly notes that survivors turning their traumatic memories into narratives can help them integrate these experiences into ‘the survivor's sense of self and view of the world’ but also, in being heard by others, ‘reintegrates the survivor into a community’ (Citation2003, xi). As this project works with testimony that narrativizes the loss of sexual subjectivity, both Alcoff and Brison give important insight into how these testimonies may be interpreted and understood, and what function they may serve for survivors.

As feminist researchers, as well as presence we pay attention to the absences in the research dataset – what isn’t being articulated and who isn’t speaking. Although only in the early stages of our data collection we are beginning to see a specific speaking subject emerge in the data, in terms of class and the sexuality of the bodies that contribute to this testimony. Some of our early data indicate that many of the stories highlight allegations of offences perpetrated by those in boys’ private schools. This could be explained because of the original call by Chanel Contos that encouraged testimony from a private girls’ school cohort who tend to socialize with students from private boys’ schools. Concurrently, there is also a high proportion of focus on schools in metropolitan Australia, rather than rural or regional areas. The prevalence of allegations and focus on the private sector does mean an absence of voices from young people who attended school in rural or regional areas, public schools, or areas of socio-economic disadvantage. We do recognize that since our original analysis the now over 6000 testimonials now also contain testimonies from public schools including historical accounts. However, when we were conducting preliminary analysis, this was not the case. We therefore cannot make comments about whether the issue of sexual harassment in school is an issue that solely relates to private schools (we certainly doubt that is the case). However, these limitations are actually quite valuable and are worth studying as issues in the public interest. These schools receive a significant amount of government funding annually (Karp Citation2021; Ore Citation2022). They make promises, both publicly and privately, about not only the quality of education they provide but of the standard of care and values they strive to uphold. Additionally, the network of ‘old boys’ created through these schools funnels these men into positions of great power and financial benefit. These informal, but strategic networks often result in the exclusion of women from ‘tacit knowledge and ultimately, organisational resources and power’ (Durbin Citation2011, 90).

Masculinities research has also highlighted the importance of the need for an intersectional, social justice approach when engaging with young men on the issue of gender-based violence and consent. While it is important to acknowledge the intersecting disadvantages some young men experience being in the world, it is clear they still benefit in terms of ongoing gender privilege and power (Keddie, Flood and Hewson-Munro Citation2022). Educating young men on issues around consent and reducing gender-based harm requires a focus on empathy and a consideration of the ways young men must consider women's lived experiences of gender violence and inequality (Keddie Citation2020; Rawlings Citation2019). This is not easy work and for many men, truly transformative gender justice will require them to engage with significant discomfort (Keddie Citation2021).

Researching digital feminist activism and working with digital data, we are not the first to examine what scholars are increasingly terming ‘networked feminism, or networked feminist activism, or digital feminist activism’ (e.g. Baer Citation2016; Fotopoulou Citation2016; Mendes, Ringrose, and Keller, Citation2019). Regardless, the scale, intensity, and geographical specificity of the testimonies means our research is a significant contribution to this growing body of work. We draw on the work of Mendes, Ringrose and Keller whose work explores the experiences of girls and women using digital platforms to challenge rape culture. Furthermore, their work examines the ways that engaging feminism with digital technologies transforms through connection, solidarity, and social change (Citation2019). Platforms like Teach Us Consent are the places, Baer suggests, where digital feminisms highlight ‘the relationship of personal experience to structural inequalities’ (2016, 29). Additionally, following Dobson's lead and taking seriously women and girls as media and cultural producers, we are mindful that researchers take care when evaluating girls and young women's digital representations (Citation2015, 1) – we do care and we do take care.

The use of social media as a form of feminist activism requires specific tools of analysis to manage the large quantities of rich and potentially ephemeral data, and research into sexual violence, and especially when this is in a digital media context, requires us to consider particular sensitivities as well as the potential for absences to be ignored. We follow the work of Aristea Fotopoulou and remember that digital feminist activism and, in our case these testimonies of trauma, engage in a type of ‘biodigital vulnerability’, that is, these are ‘contradictory spaces of both vulnerability and empowerment’ (Citation2016, 4). The data also reinforce the findings of other digital feminist researchers in that often these testimonies are not related to instances of sexual violence that have occurred recently, but rather many are reporting historic experiences of many years earlier (Mendes, Ringrose, and Keller Citation2019). As we alluded to earlier, we approach this research project with an understanding that there is power hidden within data itself. By engaging with a ‘data feminism’ approach we think about the dataset, both its uses and limits in a way that is informed ‘by direct experience, by a commitment to action, and by intersectional feminist thought’ (D’Ignazio and Klein Citation2020, 8). We are aware of the trap of falling into digital positivism, being cognisant of the fact that data are not neutral or an unproblematic access to the truth, but rather is enmeshed in systems of power that continue to benefit the elite. As feminists, we aim to resist these inequalities while also using data to expose inequitable distributions of power, which often result in harmful and violent outcomes.

The ethics of this research has always been of significant concern to us, not least of all because we are working with narratives of trauma shared on social media. As noted by Townsend and Wallace (Citation2016, 4), online spaces hold vast quantities of naturally occurring data and are fast becoming ‘popular fields sites for data collection’. In Social Media Research: A Guide to Ethics now widely used by Human Research Ethics Committees in Australia,Footnote4 they suggest three areas of concern need to be navigated by researchers working with social media data: legal (i.e. What are the terms and conditions of the social media platform for use of data by researchers?); privacy and risk (i.e. Would the Social Media User expect their data to be public or private?); and, re-use and publication (i.e. Is anonymity possible in published outputs? Is the data set shareable?) Guided by this framework, we contacted Chanel Contos and she and her team straightforwardly granted us permission to access, use and analyse the online statements. This generosity suggests that Contos wants the public to know what is happening in our schools. Ethical clearance also had to be sought from our university – this was obtained, with the main concern of preserving the anonymity of respondents. Although all of those who posted testimonies did so anonymously, a reader familiar with the schools, year and cohort may be able to ‘join the dots’ on the page itself. Of course, those who posted testimonies did so knowing their words would be made public, however, they were unaware that their words would be used for research purposes. We take this concern seriously and so we take care with their words – the names of other people (including nicknames), schools, suburbs, specific locations and situations or events have all been anonymized in our published work. It would seem then that we have ticked all of the institutional ethics boxes; however, we are keenly aware of the relational ethics associated with researching and writing trauma. Here we are drawn to the work of gender violence and trauma researcher Sophie Tamas (Citation2011, Citation2012) who acknowledges that writing and representing experiences of trauma is difficult to do and difficult to do well – trauma itself is not neat, linear or abstract, traumatic events in and of themselves are ‘unthinkable and thus unspeakable in conventional terms’ (Tamas Citation2012, 43). However like Tamas, we write this essay thinking carefully about ‘how we could – and perhaps should – represent trauma’, and in this respect, our work has only just begun.

Introducing and working with the Teach Us Consent data

As a team of qualitative researchers, the large amount of Teach Us Consent narrative was, at first glance, quite simply, overwhelming. To begin to make sense of this dataset, we followed the ‘data feminist’ approach of Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren Klein (Citation2020, 19) which includes embracing the following core principles: examining and challenging power which may be in the data; valuing multiple forms of knowledge, such as emotion and embodiment; and, rethinking and considering context, such as the fact data are created from unequal social relations and are therefore not objective nor neutral. D’Ignazio and Klein's work is important because it uses a feminist lens to argue that behind data are individuals, each with their own situated knowledges and subject positions (Citation2020, 83). In doing so this avoids conveying the view that the data comes from ‘no body’, that is ‘an imaginary and impossible standpoint that does not and cannot exist’ (Citation2020, 96) – indeed, behind each testimony is a human who is describing what is often a traumatic and violent experience, and while they have placed this testimony in the public domain, they have not necessarily expected that it would be used for research purposes. We therefore study these testimonies not judging them in terms of veracity, but rather as representations that are partly determined by the technological affordances of digital media. Following a data feminism approach allows us to acknowledge the power imbalances between us as researchers and the unnamed, unknown, mostly women's testimonies that we examine.

For the initial data run, we scraped 1479 testimonies from the Teach Us Consent website. Initially, this constituted around half of the testimonies, but the website is still a live document and now contains more than 6700 uploaded testimonies. It is important to note that, in embodying the core principles of the data feminist approach outlined earlier, this paper presents data and findings in relation to a small sample of the 1479 testimonials scraped and thus the findings need to be considered in this light.

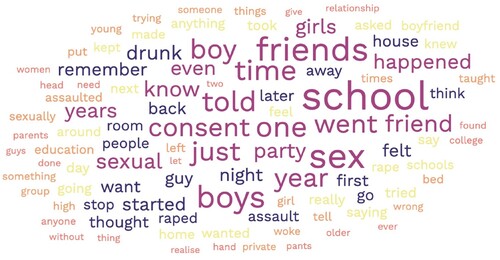

The word cloud pictured in represents our first glance at the themes in the raw data and highlights the 100 most occurring words. The words which appear have been helpful in focussing our analysis of the embodied experiences of sexual violence and consent. To assist us in unpacking the themes, we have utilized the popular and well-known qualitative data analysis tool ‘Nvivo’, designed to assist researchers to visualize areas of study and organize analytical work according to key themes.

An example from the data: naming the embodied experience of assault as ‘rape’

While we do not have space to unpack in detail the themes we are exploring in this work, we would like to share an example of the language which surrounds one of the high-frequency words in the testimonies: rape, which occurs 317 times. Although it does not occur as frequently as other words such as ‘school’ (1145 times), ‘sex’ (996 times), ‘friends’ (929 times), ‘consent’ (701 times), or ‘drunk’ (497 times), we have deliberately chosen this word as a significant lexical choice to voice trauma which is at once often times ‘unspeakable and unthinkable’ (Tamas Citation2012, 41) – there are other ways to describe sexual assault, but respondents chose to use the word ‘rape’, a tough and political word (Harris Citation2011). In her study of the word ‘rape’, Harris points to the importance of understanding the disjuncture between women's lived experiences of sexual assault and the more powerful or official interpretations which may not accurately represent those experiences (Citation2011, 45). Harris points to the fact that women's experiences may be personal but they also help to generate an understanding of the social world. The simple act of naming ‘has powerful effects on social reality’ (45).

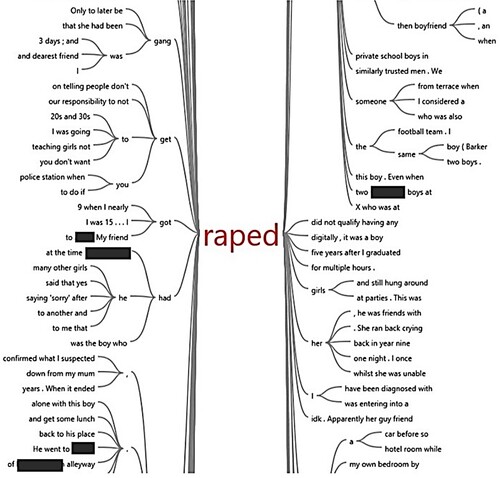

is an illustration of the ‘word tree’ NVivo created when we searched for the term ‘rape’, including stemmed words such as ‘raped’. The following two testimonies are examples of the ways in which each narrative threads together the sentiments expressed in these data strings (underlined) in a very powerful way:

I was at a party at a friends house. Parents were on site. I was raped in the garden of the boy's house. Yes we’d been drinking. Yes, I said no, repeatedly. Yes, others knew. No, nobody stepped in to help. Yes I blamed myself. No, I didn’t report because I felt responsible. I can tell you for sure and certain, this was not a one off amongst my friends. This is common. Consent? I didn’t give it! He knew it, so did others present. Yet there was a cone of silence as though this was normal.

Shortly after turning 16, and still completely sexually inexperienced, someone who attended my school attempted to rape me. What put the idea of raping me into his head? A friend later discovered that he had won me in a poker game. I doubt the other players would have assumed the right to my body if they had ‘won’ me. But he did. Having won me, there was no place for consent. He was claiming his prize.

Figure 2. An example of a text search query in NVivo showing the link between rape and issues of consent.

Reflecting on these statements as researchers, we are drawn near to the ways these words tell us something significant about the threat of objectification and subsequent invasion of her body that a woman lives. Even in situations where self and society construct barriers to keep her safe – with friends, at a friend's house, with friends at school – her female body is perceived and projected as an invitation to objectification. These words show us how in these situations, the two young women felt themselves as a body becoming grasped by others as a thing, becoming invisible, becoming unheard, becoming trapped in the prison of their skins. One of the girls screamed, the other didn’t, but both statements screamed of their pain and for us to pay attention.

Unsurprisingly, within these testimonies is the demand for consent education. Integral to those calls is the entanglement with issues of young masculinity – its sense of sexual entitlement and the influence of porn on its imaginary. As one Teach Us Consent testimony, from a writer who reports being raped repeatedly by private schoolboy states: ‘It's of course essential, and well overdue, for both schools and parents to have frank and honest conversations with boys about consent and also about the damaging messages of porn.’ And to return to the example above: how does a young man in twenty-first century Australia learn that he can win a young woman in a poker game? Any programme of consent education needs to make sure that it is not only targeted at young women (as if it is their problem alone); rather, young men need to take ownership of issues of consent (that also implies coercion). They will need to be willing to have an honest conversation regarding their embodiment, desires, and need to control, and what these have to do with flesh and blood young women (Rawlings Citation2017).

In many of the testimonies we have studied thus far, the concept of consent seems somewhat intangible, as if those contributing to the conversation on Teach Us Consent are not quite sure what they should be learning about, but they are sure that the education that they are receiving is not sufficient. They report that what consent education they have been provided is mocked by the sexual offenders, and that when it is offered, what is offered is not satisfactory, that it does not help them in the situations they had found themselves in.

Other significant issues arising from the testimonies

Interpreting and communicating consent

These accounts reflect not only sexual assault, but the spaces and locations, where it occurs, and the kinds of acts involved. Effective consent education has to be realistic about the scenarios of socializing for school students and their level of ‘sexual literacy’ – how they interpret and speak sex. Note, for instance, our earlier example above where the young woman asks: ‘What put the idea of raping me into his head?’ as evidence of the chasm between young women's and men's interpretive frameworks for sexual activity. Given that the Teach Us Consent call to action centred around experiences where consent was not given, within the testimonies themselves there is a surprising lack of discussion about consent. People who posted testimonies often went into great detail about the sexual assault or harassment that occurred, but less into what happened before the event and any discussion that might have taken place to prevent it happening in the first place. Along with friends and teachers the word parent is common, but occurs in varying ways in the text. At times parents are supervising a party where the assault occurs, at times young people fear telling their parents, other times they tell their parents, but not the police. Whatever, the situation there is no doubt that parents and care givers are seen, for better or worse, as an authority with a response-ability. Silence, as much as voice, filters through this data. There are so few testimonies where the victim carried her complaint through legal avenues. Furthermore, few accessed counselling services.

Consent has an alcohol problem

The following two statements are examples from the Teach Us Consent data which point to another significant issue in relation to issues of consent, the prevalence of alcohol:

I was at a party when I had too much to drink and was taken advantage of. He was someone I trusted, and it was my first time with him knowing it. He believed it was okay as I was drunk and he had been drinking as well.

I was in year X the first time. I had one alcoholic beverage and woke up in a bathroom in my friends [sic] granny flat. Feeling like I was missing a huge chunk of the evening I consulted my girlfriends who then told me that one of the guys we were hanging out with had a video on his phone of all the guys taking turns with me in the back seat of one of their cars.

It only lasted a few seconds but in those few seconds my friends had taken a photo of me lying there on that pool table, incoherently drunk. I would never have consented to public sex had I been sober and I definitely was not able to give consent when I was drunk.

So, where to now? Concluding reflections

As we bring this initial analysis to a close, we are first and foremost taken aback by the ways in which the Teach Us Consent testimonies exist as an ongoing digital archive of pain – as a repository of sexual trauma experienced by girls and young women in Australia in and around school life. We consider the Teach Us Consent testimonies critical historical documentation of a vast array of embodied voices speaking the collective trauma of being a young woman in Australia in the early twenty-first century. The enormity of and disturbingly repetitive qualities of these trauma narratives are too significant to be ignored, silenced or hidden away, and here our feminist-activist-archivist-researcher hearts and minds make a plea for the website and its testimonies from subjects underrepresented in official culture, to be lodged and preserved in the National Library of Australia Trove facility. This is a moment where the power of witnessing cannot be underestimated and we further wonder, what the relationship is between these testimonies as Australian digital archives of pain, and the feminist goals of ending rape culture in an age of testimony and judgement.

When we began looking at Teach Us Consent, we were hopeful that given the scale and rapid growth of this data set, by tuning into and turning up the volume of girls and young women's voices on consent education we would gain understanding of the social, educational, and cultural experiences related to sexual assault that high school students bring into university residential colleges, and that these would provide valuable insight into how we might approach our work in that tertiary setting. We heard the repeated narrative of young women feeling in some way either incapable of giving consent to sexual activity, or their lack of consent being ignored by perpetrators. We heard a call for ‘real world’ sexual consent education, before-during-and after-high school years. Again, it will not just be schools, it will also require a commitment to an honest appraisal of young men and masculinity by parents and their old boys’ associations. Concomitantly, some of the codes of femininity such as being compliant, being trusting of men and boys, not complaining, needing to conform, and feeling body shame, will need to be unpacked.

While we are aware of the increasing amount of work being undertaken in primary and secondary school contexts in relation to consent education, little or no attention has been given to the ways in which consent education and its effects are performed in university residential colleges from the embodied and lived experience of students. With the latest National Student Safety Survey showing that sexual harassment and assault continues at university campuses, clubs, societies and even lecture theatres (see the Australian Universities’ Respect. Now. Always report and follow up surveys, e.g. Universities Australia Citation2021), we now hope to extend this research to tertiary education settings. This task is made even more urgent by the situation in which there is a reasonable probability that some young women already assaulted while attending private secondary schools will move to a residential college and be subjected to yet another iteration of sexual violence. The statements shared on Teach Us Consent then, provide a glimpse into a disturbing cycle of sexual trauma and as a form of digital activism and testimonial space, have an enormous contribution to make to intervening, enriching and transforming consent education in university residential colleges – and it is time we paid attention.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the work and support of Chanel Contos and contributors to the Teach Us Consent website.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [RM] upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Elizabeth Mackinlay

With 25 years in the discipline, Professor Elizabeth Mackinlay is a leading Australian teacher and researcher in the fields of feminist theory, gender and education, and qualitative research methods. Associate Professor Mackinlay is a leader in her field with an extensive list of publications. Most recently she has published ‘Critical Writing for embodied approaches: autoethnography, feminism and decoloniality’ (2019), ‘We only talk feminist here: Feminist academics, voice and agency in the neoliberal university’ (2017) (with Briony Lipton) and ‘Teaching and learning like a feminist: storying our experiences in higher education’ (2016). Associate Professor Mackinlay draws on this expertise to lead the intellectual and practical directions of this project.

Renée T. Mickelburgh

Dr Renée Mickelburgh is an Associate Lecturer in Strategic Communication at the University of Queensland. With a specific focus on gender equality and environmental concerns, Renée has had success as a journalist and communications practitioner, educator, and researcher. At the heart of Renée's work is a strong commitment to listening and empowering the communities and organisations she works and researches with.

Margaret Henderson

Associate Professor Margaret Henderson is a leading feminist scholar and has published widely in the fields of feminist cultural studies and literary studies, including supervising projects on young women and representations of sexual violence. She has particular expertise in feminist textual analysis and contemporary Australian popular culture. Her most publications include ‘Postfeminism in Context: Women, Australian Popular Culture, and the Unsettling of postfeminism’ (2019) (with Anthea Taylor) and Marking Feminist Times: Remembering the Longest Revolution in Australia (2006).

Bonnie Evans

Dr Bonnie Evans is an Associate Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Queensland. Her research examines the connections between sexual violence, feminism, and recent horror and true crime film and television.

Christina Gowlett

Dr Christina Gowlett is a senior lecturer in the School of Education at The University of Queensland. She draws from philosophy and sociology to examine contemporary practices and policies in education. Prior to working at UQ, Christina held a prestigious McKenzie Postdoctoral Research Fellowship at The University of Melbourne. She also has experience working in schools as both a humanities teacher and head of department.

Notes

1 Former federal government staffer Brittany Higgins alleged a colleague raped her after hours in a Parliament house ministerial office in 2019 (Nicols et al. Citation2021). This and further revelations about sexual harassment at Australian parliament house led to nation-wide March 4 Justice rallies (Wahlquist Citation2019). Higgins alleged rape and the subsequent rallies triggered Australia’s sex discrimination commissioner Kate Jenkins to launch an inquiry into federal parliament’s workplace culture. She found that a third of staffers had experienced sexual harassment (Murphy Citation2021). Following the release of the review by Kate Jenkins, Prime Minister Scott Morrison apologized in federal parliament to Higgins and for the poor workplace culture at parliament house (Murphy Citation2022).

2 Kambala School is an elite Anglican private girls school in inner Sydney. It’s website tagline is ‘Empowering young women of integrity’.

3 ‘Do they even know they did this to us?’: why I launched the school sexual assault petition | Chanel Contos | The Guardian.

4 Elizabeth Mackinlay was the Chair of the Human Research Ethics Committee at The University of Queensland from 2017 to 2022 and is currently the Chair of the Human Research Ethics Committee at Southern Cross University. In her experience, the framework by Townsend and Wallace has been widely embraced by Ethics Reviews Committees as it provides institutions and individuals with valuable legal, professional and procedural consideration to ensure social media research is conducted ethically.

References

- Alcoff, Linda Martín. 2018. Rape and Resistance. Newark: Polity Press.

- Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). 2022a. The Australian Curriculum: Version 9.0. https://v9.australiancurriculum.edu.au/.

- Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). 2022b. Media Release: Updated Australian Curriculum Raises Standards. endorsement-ac-media-release-2022.pdf (acara.edu.au).

- Australian Human Rights Commission. 2022. Media Statement: National Survey on Understanding and Experiences of Consent. https://humanrights.gov.au/about/news/media-statement-national-survey-understanding-and-experiences-consent.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2022. Family, Domestic and Sexual Violence Data in Australia. AIHW, Australian Government. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/348b5559-ad3b-48a7-8e79-cea0a6c02076/Family-domestic-and-sexual-violence-data-in-Australia.pdf.aspx?inline=true.

- Baer, Hester. 2016. “Redoing Feminism: Digital Activism, Body Politics, and Neoliberalism.” Feminist Media Studies 16 (1): 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2015.1093070.

- Brison, Susan J. 2003. Aftermath: Violence and the Remaking of a Self. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Burke, Megan. 2019. When Time Warps: The Lived Experience of Gender, Race, and Sexual Violence. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Burke, Tarana. 2021. Unbound: My Story of Liberation and the Birth of the Me Too Movement. London: Headline Book Publishing.

- Cahill, Helen, and Babak Dadvand. 2021. “Triadic Labour in Teaching for the Prevention of Gender-Based Violence.” Gender and Education 33 (2): 252–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2020.1722070.

- de Beauvoir, Simone. (1949) 2011. The Second Sex. London: Vintage.

- D'Ignazio, Catherine, and Lauren F. Klein. 2020. Data Feminism. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Dobson, Amy. S. 2015. Postfeminist Digital Cultures Femininity, Social Media, and Self-Representation. 1st ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Durbin, Susan. 2011. “Creating Knowledge through Networks: A Gender Perspective.” Gender, Work, and Organization 18 (1): 90–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2010.00536.x.

- The Everyday Sexism Project. n.d. Retrieved March 18, 2022, from https://everydaysexism.com/.

- Everyone’s Invited. 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2022, from https://www.everyonesinvited.uk/.

- Fotopoulou, Aristea. 2016. Feminist Activism and Digital Networks between Empowerment and Vulnerability. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gill, Rosalind. 2007. Gender and the Media. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Gilmore, Leigh. 2017. Tainted Witness: Why We Doubt What Women Say About Their Lives. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Harris, Kate. 2011. “The Next Problem with No Name: The Politics and Pragmatics of the Word Rape.” Women’s Studies in Communication 34 (1): 42–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/07491409.2011.566533.

- Henderson, Margaret, and Anthea Taylor. 2020. Postfeminism in Context: Women, Australian Popular Culture, and the Unsettling of Postfeminism. New York: Routledge.

- Karp, Paul. 2021. “Australian Government Funding for Private Schools Still Growing Faster than for Public.” The Guardian, February 2. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/feb/02/australian-government-funding-for-private-schools-still-growing-faster-than-for-public.

- Kearney, Sarah, Cara Gleeson, Loksee Leung, Debbie Ollis, and Andrew Joyce. 2016. Respectful Relationships Education in Schools: The Beginnings of Change – Final Evaluation Report. Melbourne: Our Watch.

- Keddie, Amanda. 2020. “Engaging Boys and Young Men in Gender Transformation: The Possibilities and Limits of a Pedagogy of Empathy.” NORMA: International Journal for Masculinity Studies 15 (2): 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/18902138.2019.1706883

- Keddie, Amanda. 2021. “Engaging Boys in Gender Activism: Issues of Discomfort and Emotion.” Gender and Education 33 (2): 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2020.1716956

- Keddie, Amanda. 2023. “Student activism, sexual consent and gender justice: enduring difficulties and tensions for schools.” The Australian Educational Researcher 50 (2): 503–518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-021-00474-4

- Keddie, Amanda, Michael Flood, and Shelley Hewson-Munro. 2022. “Intersectionality and social justice in programs for boys and men.” NORMA: International Journal for Masculinity Studies 17 (3): 148–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/18902138.2022.2026684.

- Keddie, Amanda, and Deb Ollis. 2019. “Teaching for Gender Justice: Free to Be Me?” Australian Educational Researcher 46 (3): 533–547. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00301-x.

- Keddie, Amanda, and Debbie Ollis. 2021. “Context Matters: The Take Up of Respectful Relationships Education in Two Primary Schools.” Australian Educational Researcher 48 (2): 211–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-020-00398-5.

- Mackinlay, Elizabeth. 2015. “Making an Appearance on the Shelves of the Room We Call Research: Autoethnography-As-Storyline-As Interpretation in Education.” In International Handbook of Interpretation in Educational Research, edited by Paul Smeyers, 1437–1456. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Martino, W., and M. Pallotta-Chiarolli. 2005. Being Normal Is the Only Way to be. Sydney: UNSW Press.

- Maunder, Sarah. 2022. Consent Education to be Added to Australian Curriculum From Next Year. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-02-17/mandatory-consent-lessons-to-be-taught-in-schools/100841202.

- McRobbie, Angela. 2009. The Aftermath of Feminism Gender, Culture and Social Change. London: Sage.

- Mendes, Kaitlynn, Jessica Ringrose, and Jessalynn Keller. 2019. Digital Feminist Activism: Girls and Women Fight Back Against Rape Culture. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Murphy, Katharine. 2021. “Sex Discrimination Commissioner Finds Gender Inequality Key Driver of Toxic Culture in Federal Parliament.” The Guardian, November, 30. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/nov/30/sex-discrimination-commissioner-finds-gender-inequality-key-driver-of-toxic-culture-in-federal-parliament.

- Murphy, Katharine. 2022. “Australian PM apologises for ‘Terrible’ Parliamentary culture after Canberra’s #MeToo reckoning.” The Guardian, March 8. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/feb/08/australian-pm-apologises-for-terrible-parliamentary-culture-after-canberras-metoo-reckoning.

- Nicols, Sean, Sashka Koloff, Naomi Selvaratnam, and Ali Russell. 2021. “Parliament House Security Guard Nikola Anderson Describes Finding Brittany Higgins on Night of Alleged Rape in Minister’s Office.” ABC Online, March 22. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-03-22/four-corners-security-guard-brittany-higgins/13259262.

- Ollis, Debbie. 2018. Building Respectful Relationships: Stepping Out Against Gender-Based Violence. Melbourne: Victorian Department of Education and Training.

- Ollis, Debbie, Cassandra Iannucci, Amanda Keddie, Elise Holland, Maria Delaney, and Sarah Kearney. 2022. “'Bulldozers Aren't Just for Boys’: Respectful Relationships Education Challenges Gender Bias in Early Primary Students.” International Journal of Health Promotion and Education 60 (4): 229–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/14635240.2021.1875020.

- Ore, Adeshola. 2022. “Private School Funding in Australia has Increased at Five Times Rate of Public Schools, Analysis Shows.” The Guardian, February 16. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/feb/16/private-school-funding-has-increased-at-five-times-rate-of-public-schools-analysis-shows.

- Our Watch. 2021. Respectful Relationships Education to Prevent Gender-Based Violence: Lessons from a Multi-Year Pilot in Primary Schools. https://media-cdn.ourwatch.org.au/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2021/04/28133853/RREiPS-evaluation-report-accessible-280421.pdf.

- Rawlings, Victoria. 2017. Gender Regulation, Violence and Social Hierarchies in School ‘Sluts’, ‘Gays’ and ‘Scrubs’. London: Palgrave.

- Rawlings, Victoria. 2019. ‘It's not Bullying’, ‘It's Just a Joke’: Teacher and Student Discursive Manoeuvres Around Gendered Violence.” British Educational Research Journal 45 (4): 698–716. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3521.

- Simms, E. M., and B. Stawarska. 2013. “Introduction: Concepts and Methods in Interdisciplinary Feminist Phenomenology.” Janus Head 3 (1): 6–16.

- Stein, Edith. (1959) 2017. Essays on Woman: The Collected Works of Edith Stein (Book 2). Washington: ICS.

- Tamas, Sophie. 2011. “Biting the Tongue That Speaks You.” International Review of Qualitative Research 4 (4): 431–459. https://doi.org/10.1525/irqr.2011.4.4.431.

- Tamas, Sophie. 2012. “Writing Trauma: Collisions at the Corner of Art and Scholarship.” Theatre Topics 22 (1): 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1353/tt.2012.0009.

- Townsend, Leanne, and Clare Wallace. 2016. Social Media Research: A Guide to Ethics. https://www.gla.ac.uk/media/Media_487729_smxx.pdf.

- Universities Australia. 2016. Respect. Now. Always. https://www.universitiesaustralia.edu.au/project/respect-now-always/.

- Universities Australia. 2022. 2021 National Student Safety Survey. https://www.universitiesaustralia.edu.au/policy-submissions/safety-wellbeing/nsss/.

- Van Manen, M. 2016. Phenomenology of Practice: Meaning-giving Methods in Phenomenological Research and Writing. Abingdon, OX: Routledge.

- Vera-Grey, Fiona. 2017. Men’s Intrusion, Women’s Embodiment: A Critical Analysis of Street Harassment. London: Routledge.

- Wahlquist, Carla. 2019. “Brittany Higgins Addresses March 4 Justice Rally as Women Demand Action Across Australia.” The Guardian, March 15. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/mar/15/brittany-higgins-addresses-march-4-justice-rally-as-women-demand-action-across-australia.

- Young, Iris Marion. 2005. On Female Body Experience: “Throwing Like a Girl” and Other Essays. New York: Oxford University Press.