Abstract

Despite the growing interest in the phenomenon of extreme work amongst academics, policy makers and the media, the area is characterized by different constructs, terminology, and disparate research findings on both contexts and outcomes. The aim of this positional paper, as part of a double Special Issue on extreme work and ‘working extremely’, is to provide a timely review of the field and bring some coherence to it through providing a classification of extreme work and its associated outcomes. Specifically, we use the outputs of a systematic review to capture and map the complexity of this area of research, illustrate the different contexts that influence and shape its emergence, and highlight different employee outcomes. Our typology serves as a heuristic device to categorize the 12 papers that make up this Special Issue, map potential future research questions and avenues, and identify human resource management (HRM) practice implications at multiple levels.

Introduction

In recent years, the ‘extreme’ has received increased attention within the human resource management (HRM) literature (Bader, Schuster, & Dickmann, Citation2019; Gascoigne et al., Citation2015); however, this literature has primarily focused on extreme environments and jobs rather than extreme work. These include the investigation of hostile environments such as global terrorism (Harvey et al., Citation2018) and managing people in hostile environments (Bader, Schuster, Bader, et al., Citation2019; Dickmann et al., Citation2019). In the case of extreme jobs, research has focused on job roles in terrorism endangered countries (Bader, Schuster, & Dickmann, Citation2019) as well as jobs found in firefighting, the ambulance service and hospitals (Wankhade et al., Citation2020). While this macro-level perspective is valuable, many jobs in organizations are not by definition extreme jobs and/or performed in extreme contexts yet they involve extreme work. We define extreme work for the purposes of this Special Issue as elements of day-to-day work that are characterized by the increased effort or intensity that employees must use to deliver work outcomes. It includes hours worked, effort (physical, mental and emotional),time demand in terms of pressure to get things done and work role overload (Granter et al., Citation2019; Green et al., Citation2022). Hewlett and Luce (Citation2006) provide important indicators of these micro level dimensions of extreme work including: unpredictable workflows, fast-paced work involving tight deadlines, scope of responsibility that is too board, and a large number of direct reports. We include work intensification as part of this list; however, we acknowledge that not all work intensification is necessarily extreme and there are challenges delineating the boundaries between extreme and non-extreme. To date scholars have focused on investigating the outcomes flowing from work intensity to make assessments about whether it is extreme or not.

We have limited insights into extreme work in organizations, the contexts in which it arises, its outcomes, including performance, physical and mental health and wellbeing, and the role that HRM practices play in amplifying and/or alleviating extreme work. These are important questions because the label ‘extreme’ increasingly defines what may be described as ‘normal’ or mainstream work (Caligiuri et al., Citation2020; Carnevale & Hatak, Citation2020). The development of theory and research insights on micro conceptualizations of extreme work can help us to understand the role of HRM in exacerbating or alleviating it negative outcomes.

Commentators have suggested that the COVID-19 pandemic represented a turning point in how we understand extreme work. It has significantly blurred the lines between work and non-work, and it is increasingly difficult to distinguish where one stops and the other starts (Grant et al., Citation2023). The empirical evidence highlights a significant reshaping of what work means, and where it is conducted (Kniffin et al., Citation2021). Prior to the pandemic extreme work manifest in work intensification and long working hours had become commonplace with many workers experiencing its negative impacts (Le Fevre et al., Citation2015; Mariappanadar, Citation2014). However, as a direct result of COVID-19, the very notion of the traditional workplace and the ability of employees to compartmentalize work life and home life is challenging due to remote and hybrid working (Farivar et al., Citation2023; McPhail et al., Citation2023). It is therefore not surprising that extreme work, has gained momentum in the academic literature (Cai et al., Citation2021; Mousa et al., Citation2023; Tham et al., Citation2023; Townsend & Loudoun, Citation2023).

While the shift to extreme work has been gradual (Hewlett & Luce, Citation2006), it arguably has been exacerbated by technological advances, market and industry competition, the rise of social media, multi-generational cohorts in the same workspace, and exogenous shocks such as a global pandemic. Consequently, researchers and practitioners seek to understand questions such as: (a) How does context shape extreme work? (b) What are the impacts of extreme work on employees? (c) What are the impacts of HRM practices on extreme work? and (d) What, if anything, can organizations and HRM do to reduce the harmful outcomes of extreme work?

It is these questions that are the focus of this Special Issue on extreme work. We did, however, experience challenges in defining what extreme work means because of fragmentation in the way the concept is defined and researched. It can mean many things including long working hours (Dupret & Pultz, Citation2021; Telford & Briggs, Citation2022), intensity of work (Blagoev et al., Citation2018; Bunner et al., Citation2018), edge work/workers or tasks that involve significant risk (Granter et al., Citation2019; Ward et al., Citation2020) and extreme team contexts (Bell et al., Citation2018; Crust et al., Citation2019; Driskell et al., Citation2018; Golden et al., Citation2018). Some of these labels reflect specific features of what ‘extreme’ means in the context of carrying out work whereas other terms reflect environmental factors that create an ‘extremity’ under which work is carried out, and other terms depict the impacts of ‘extreme work’.

In this paper, we delineate the scope of research on extreme work and highlight its key features and characteristics. To capture its complexity, we conducted a systematic review to highlight the different contexts within which it occurs and the different outcomes. We also provide a typological categorization of extreme work, summarize the 12 papers that make up this Special Issue, and provide a future research agenda.

Systematic review: scope and methodology

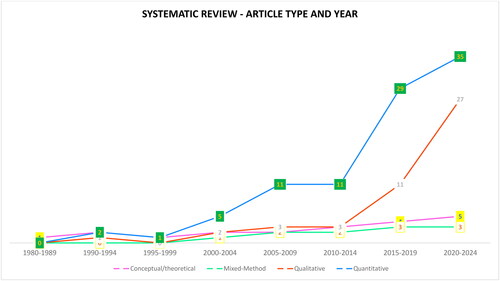

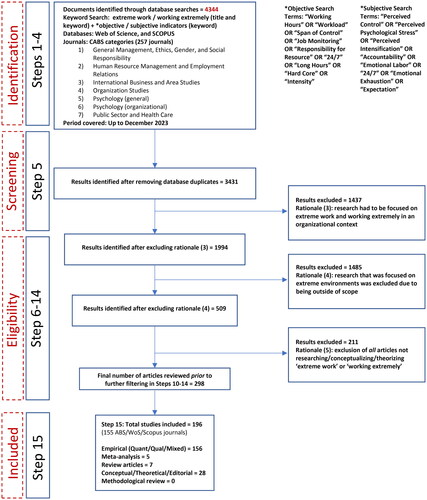

To bring coherence to a fragmented and diverse field of investigation we conducted a systematic review using the 15-step method developed by Bolt et al. (Citation2022) (). Following Bolt et al. (Citation2022), we categorized our approach in ‘bite size’ sections. Steps 1–4 involved identification of the parameters of the field and specification of the search criteria, (see for full list of keywords and search terms). We created search boundaries to frame our database inquiries using the Chartered Association of Business Schools (CABS) Academic Journal Guide [AJG] (CABS, Citation2021) categories: General Management, Ethics, Gender and Social Responsibility; Human Resource Management and Employment Studies; International Business and Area Studies; Organization Studies; Psychology (general & organizational); and Public Sector and Health Care. In all, 314 academic journals formed the boundary for our searches, generated through the Web of Science Journal Citation Reports facility.

Figure 1. Systematic review process for extreme work and working extremely. Source: derived from Pickering and Byrne (Citation2014) and Bolt et al. (Citation2022).

We restricted our search to CABS journals ranked 4*, 4, 3 and 2. We used Web of Science and SCOPUS as our literature search databases given their breath and depth of access to relevant literature, ease of use and reliability of search results. We included only peer-reviewed articles (including early view) and excluded ‘grey’ literature including Government/NGO/Professional body reports and included all paper up to December 2023. In the Clarivate Web of Science database, we entered the Boolean string ‘[All Fields (“extreme work”)] and [All Fields (“working extremely”)] and [All Fields (“internal and external outcomes of extreme work/working extremely”)] AND [Publication Titles (“Academy of Management Journal”)]’. We repeated the same search criteria and process for SCOPUS and in total, we identified 4344 articles. After comparing the two databases and excluding duplicate papers found in both, we narrowed it down to 3431 articles.

The next steps in our process, Steps 5–9, were focused on narrowing down our inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria applied was that all articles had to focus on extreme work and the research had to be located within an organizational setting, which resulted in 1437 articles being excluded from our list. This yielded 1994 articles which fell within our inclusion criteria. Following elimination of articles focused on extreme environments, we eliminated a further 1485 articles, and this resulted in 509 articles remaining. By focusing only on papers that addressed ‘extreme work’ and ‘working extremely’ in an organizational context, this yielded a final total of 298 articles.

We then created an Excel spreadsheet in which the details of each paper in our final list were entered with various important features of the paper included such as author, year, publication title, methodology and theoretical framework. Step 7 established additional categories and subcategories, while Steps 8 and 9 focused on ensuring that all articles included in our final list could be used to develop our typology, Steps 10–14 involved coding the papers into empirical articles, meta-analyses, review articles, conceptual articles and methodological articles. Step 15 involved reviewing the entire list to agree on those articles that should be included and excluded consistent with the inclusion/exclusion criteria. This resulted in 196 articles which we used for the analysis ().

An extreme work typology

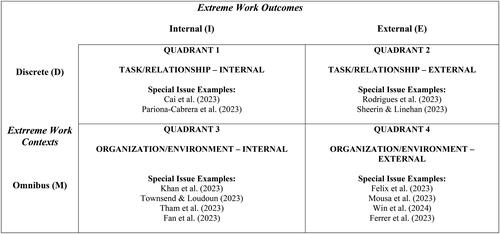

Our typology of extreme work derived from the systematic review is intended to help identify future research issues within this research area. The purpose of the proposed typology is to reduce the plethora of dimensions of extreme work and its outcomes into a smaller number of categories which share key attributes. We present this typology as a heuristic device representing concepts rather than empirical examples and the dimensions that we propose are based on the notion of an ideal type. We critically synthesize the multidisciplinary literatures included in the systematic review into a 2-by-2 figure () which then generates four variants of extreme work and its outcomes. Consistent with Collier et al. (Citation2012), we suggest these resulting types as analytical types for researching extreme work in organizations.

The vertical axis captures the contexts of extreme work informed by ideas proposed by Johns (Citation2006) who described proximate contexts and those that are more distal. The proximate dimensions of context include the task itself, the social, relationship and physical contexts. Examples of the task context include autonomy, uncertainty, accountability and resources; examples of social context include social relationships, social structure and direct social influence; and examples of physical context include temperature, physical space and the built environment. Omnibus context is the larger context within which discrete context is located and it includes the wider organization, the external environment and the professional context. These dimensions of context are more distant or distal.

The horizontal axis of our typology captures the outcomes of extreme work and includes internal and external outcomes. We followed the approach by Allan et al. (Citation2018) who make a distinction between outcomes that occur in the workplace and those that are relevant to outside of work. Internal outcomes include working long hours, amount of tasks, scope of duties and responsibilities, increased accountabilities and lack of perceived organizational support (POS). The external outcomes include health and wellbeing, including dimensions such as exhaustion and burnout, work-family conflict, work-life balance, life dissatisfaction, reduced professional reputation and identity, stigma, career change outside of the organization and unemployment. We categorize burnout and exhaustion as external outcomes because of their potential spillover to the non-work arena. We then suggest four ideal types: (1) Task/Relationship-Internal Quadrant; (2) Task/Relationship-External Quadrant; (3) Organization/Environment-Internal Quadrant; and (4) Organization/Environment-External Quadrant.

Our systematic review informed typology

Task/relationship-internal quadrant

Studies in this quadrant primarily focus on two elements of discrete context-task and relationships, which is consistent with Johns (Citation2006) theorizing, and they report findings related to internal outcomes (see ). Dugan et al. (Citation2022), for example, investigated employees on precarious work schedules characterized by long shifts, non-daytime hours, intensity and unsocial work hours and the scheduling of work involved 6 + days of work without a break. Boddy et al. (Citation2015) investigated five organizational directors and two senior managers who had worked with six corporate psychopaths. They experienced high levels of abusive control, bullying, intimidation, coercion and whimsical decision making, resulting in the immediate work relationships being toxic. Karatepe (Citation2013) found that front-line employees were subjected to increased demands from customers and experienced frequent role conflict. Kelliher and Anderson (Citation2010) focused on the adoption of flexible working practices and found that they led to imposed intensification, enabled intensification and intensification out of desire to give back to the organization.

Table 1. Dimensions of task/relationships and internal outcomes.

Fitzgerald et al. (Citation2019), investigated intensification of Australian public school teachers’ work, in particular the requirement to work long hours to cope with expanded tasks and devolved responsibility. Cooke (Citation2006) also investigated increased work intensification amongst nurses arising for empowerment. However, this empowerment was accompanied by impressed controls with nurses describing their managers as ‘seagull’ managers who were distant, distrustful, defensive and engaged in destructive criticism. This faux flexibility creates what is known as an autonomy-control paradox where the provision of perceived greater autonomy is often combined with greater organizational control (Putnam et al., Citation2014). Hassard and Morris (Citation2020) found that managers were exposed to continual productivity demands that led to feelings of job insecurity, long working hours and significant work intensification. Bittman et al. (Citation2009) investigated the use of the mobile phone as part of day-to-day work, making it impossible to be out of touch and creating significant time pressures. They found in the case of men this led to significant work intensification. Cumulatively, the studies reveal that both task and relationship characteristics as aspects of discrete context were associated with a variety of internal outcomes including intensification manifest in longer working hours, more work to do, excessive control and deterioration in work relationships. While we acknowledge that work intensification can lead to outcomes that are positive, the majority of studies that included in this review focused on reporting negative outcomes.

Task/relationship-external quadrant

Studies in this quadrant also focused on tasks and relationships but emphasized external outcomes (see ). This quadrant is less frequently investigated in the literature. Burrow et al. (Citation2020), for example, investigated the experience of teachers who experienced poor leadership and toxic relationships and who were subjected to homophobic abuse, impossible demands from the principal and these turn increased work overload and pressure to deliver on tasks. Lee et al. (Citation2021) synthesized the literature on long working hours and a range of external outcomes including psychological stress, depression and anxiety, health behaviors including smoking, alcohol consumption and physical inactivity and hypertension. Paškvan et al. (Citation2016) found that increased work intensification impacted psychological stress, employee wellbeing and burnout. Overall, the small number of studies in this quadrant have investigated a relatively narrow range of external outcomes focusing primarily on health and wellbeing.

Table 2. Dimensions of task/relationships and external outcomes.

Organization/environment-internal quadrant

Studies within this quadrant are focused on both organizational and external environmental forces driving extreme work (see ). Telford and Briggs’ (Citation2022) research focused on the reinforcement of targets by managers and the expectation that employees will engage in overwork led to corrosive relationships at work. For example, employees had to work weekends and evenings, they had to significantly increase workload due to efficiency initiatives, and they were also subjected to productivity audits. Bouwmeester et al. (Citation2021) reported similar findings for millennial consultants who had to work on average working week of around 60 h and they had to recalibrate what was ‘normal’ work demands. Dupret and Pultz (Citation2021) focused on not-for-profit organizations and found that a productive self-disciplining strategy emerged that increased work intensification. This was manifest in conflicts around paid work versus free time, self-management versus work intensification seeking meaningfulness versus devotion to the organization’s cause. Hassard and Morris (Citation2020) revealed that middle managers across multiple sectors experienced role expansion, the requirement to do more, constant evolvability through ICT and longer working hours. Stacey et al. (Citation2022) provides an excellent example of the operation of environment context and the emphasis on internal where they interviewed 31 teachers across the state of New South Wales, Australia. They experienced substantial workload increases within a devolved public education context and highlighted the increased accountability for paperwork and reporting requirements which have resulted in fundamental changes in what it means to be a teacher, and the increased workload has resulted in the need to undertake ‘triage’ and leave tasks not fully competed.

Table 3. Dimensions of the organization/environment and internal outcomes.

Wang et al. (Citation2021) also focused on the environmental context and investigated work intensification amongst vice principals in Ontario, Canada and highlighted the impacts of national and regional policies, expansion of duties and responsibilities on the amount of work to be undertaken, and its implications for wellbeing. Wankhade et al. (Citation2020) investigated the UK Ambulance Service and work intensification and found multiple dimensions of the environmental context leading to work intensification including a significant rise in demand for ambulance services, insufficient funding, confusion over response time targets, shortages of paramedic staff, high sickness rates and the challenges of working within an increasingly complex healthcare system. These dimensions resulted in a significant increase in hours worked, the requirement for tight deadlines, fast paced work and unrealistic targets leading to significant stress and wellbeing issues. de Ruyter et al.’s (Citation2008) study of nurses and local authority social workers also illustrates the impact of environmental context dimensions including the emergence of agency contracts, government efforts to modernize public services and the role of highly feminized professions have resulted a deterioration in job quality, increased caseloads, increased audit and inspection reequipments and workload expansions all leading to stress and negative wellbeing outcomes. Finally, Willis et al. (Citation2016) focused on new public sector management in Australia and its impacts on the extreme work in the case of nurses and the use of a rounding a risk reduction strategy. It was used as a strategy to deal with missed care targets and significantly impacted, for example, the amount of work undertaken, control, of work, and increased accendibility demands. These impacted work-family balance and nurse wellbeing. Cumulatively, these study examples reveal that both the organization and the wider environment have impacts at the most micro level and is reflected in a multitude of internal outcomes including working long hours, work intensity, faster work, split shifts, increased auditing, inspections and accountability.

Organization/environment-external quadrant

Studies that investigate the impacts of organizational/environmental context on extremal outcomes are fewer in number (see ). This is not surprising given that HRM as area of investigation focuses on outcomes within the workplace. Brunetto et al. (Citation2022), for example, investigated police in both the UK and Italy and found that despite national policies and a commitment to support police and emergency service employees, these employees experienced significant burnout and poor overall resilience. Lawrence et al. (Citation2019) investigated high school teachers in Australia and the impacts of policies and national regulations on teaching and non-teaching requirements and how these lead to outcome such as burnout and emotional exhaustion. They found that the increased non-teaching requirement was the most significant predictor of burnout. Ogbonna and Harris (Citation2004) focused on university lecturers and the impact that the different and sometimes conflicting demands of various stakeholders, the heightened intensification that the academic process has on their emotional labor and a requirement for professional detachment to cope. Alfes et al. (Citation2018) investigated professionals in state administration in Switzerland and found that due to institutional pressures employees experienced subjective mental and health issues. Pasamar et al. (Citation2020) focused on academics and job intensity due to fears about career progression, which led to significant work family conflict and the flexibility enjoyed by academics was not sufficient to prevent this conflict occurring. Valli and Buese (Citation2007) investigated teachers over a four-year period and found increased intensification in instruction institutional requirements, collaboration and learning. These changes had unanticipated and often negative, consequences for teachers’ relationships with their profession and sense of professional well-being. Cumulatively, the modest number of studies in this quadrant point to significant implications of organizational and wider environment dimensions of extreme on external outcomes such as mental health, well-being, professional standing and identity.

Table 4. Dimensions of the organization/environment and external outcomes.

The special issue papers

We present 12 papers on extreme work in this Special Issue that collectively advance HRM theory, knowledge and practical insights. Each of the papers is positioned within one of the four quadrants in our typology.

Task/relationship-internal quadrant

Two papers in our Special Issue investigate task/relationship context and impacts on internal outcomes. Cai et al. (Citation2023) focused on an important relational aspect of frontline employee work in UK supermarkets. Insights derived from 50 interviews highlighted that customer hostility and physical aggression experienced by these workers juxtaposed with the undervaluing of their critical role as essential workers during the pandemic added to the stress of doing extreme work. They experienced unpredictable working hours, worked at a faster pace and had increased workloads. In addition, they experienced more responsibilities and demands on their skills, and they were exposed to more physical risk. From a HRM practice perspective, the key message was the need for more support to cope with the stress and associated issues of anxiety and alienation that are associated with working in a low paid, semi-skilled but demanding frontline role. Pariona-Cabrera et al. (Citation2023) focused on another frontline group—nurses and personal care assistants in Australia and China—and investigated the impact of workplace violence for frontline nurses and personal care assistants. The study examined the potential role of wellbeing HRM (WBHRM) in helping these groups cope with the emotional burden of workplace violence. These practices were influential in moderating the relationship between workplace violence, job stress and subsequent quality of care.

Task/relationship-external quadrant

Two papers in our Special Issue investigate task/relationship context and impacts on external outcomes. Rodriguez et al. (Citation2023) investigated frontline healthcare workers—Chilean kinesiologists—and how doing extreme work during COVID-19 led to professional enhancement, elevated professional legitimacy, greater professional purpose and the building of a narrative around occupational heroism. This finding suggests that there is scope for HRM practices to focus on achieving wider external outcomes for employees. Sheerin and Linehan (Citation2023) explored the experiences of academic women who attempted to respond to the intensification of elder care needs while managing an academic career during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study highlighted an important external outcome focused on societal ideas of the ‘ideal academic’ and intense work patterns linked to success, which can be seen as a challenge for both academic managers and workers.

Organization/environment-internal quadrant

Four papers in our Special Issue investigated organization/environment context and impacts on internal outcomes. Tham et al. (Citation2023) investigated the impacts of a lack of perceived organizational support impacted burnout during the pandemic. This research was conducted in the state of Victoria, Australia during the pandemic, with Melbourne (the capital), the most locked down city in the world during COVID–19, for over 250 days. This put extreme pressure on the paramedic workforce. They found there where such support existed it had a positive impact on the burnout experienced by paramedics. Townsend and Loudoun (Citation2023), in contrast, focused on police work, which is built around being skilled for extreme events, but which is often punctuated by extended periods of normality. Using a combination of interviews and diaries, the study revealed extreme work resulting from an outdated HRM system and related technology placing HRM at the center of the workforce challenges. HRM as source of extreme work is also investigated by Fan et al. (Citation2023), who investigated work extremes caused by inadequate and problematic HRM systems. They looked at four paradoxical tensions that impeded social workers’ capabilities to do their job effectively. These tensions depleted the physical, psychological and emotional resources of social workers. Khan et al. (Citation2023) points out that there remains a significant gap in the literature regarding the role of HRM in discouraging extreme work and calls for HRM practitioners to show leadership on these issues. They argue that issues of workloads, prolonging working hours and intensifying physical and mental stress are contributing to extreme work, themes already explored in this Special Issue. However, in addressing these topics, they propose that sustainable HRM become the underlying culture drive and explore strategies to counter extreme work.

Organization/environment-external quadrant

Four papers in our Special Issue investigated organization/environment context and impacts on external outcomes. Felix et al. (Citation2023) investigated workers charged with cutting off electricity in the Brazilian favelas. The study illustrates how these workers strive to build positive meanings and professional identification within the work they do in response to the negative judgments of some community that they encounter. The interesting twist of the paper comes in the fact that their mental/psychological approach makes them work more intensely, which is linked to a sense of wellbeing at work. The key implication for HRM is that when they experience situations in which their sense of self is threatened, they reject being subjected to extreme working conditions and limit the intensity of their work. Mousa et al. (Citation2023) investigated public health nurses’ engagement in extreme work and the ethical issues that it presented. They point to a multiplicity of omnibus context factors such as religion, gender inequality and staff shortages as shaping their engagement in extreme work specifically working long hours, accepting intensive workloads and being available 24 h a day, seven days a week. They give prominence to physical and mental health and broader wellbeing outcomes that arise for this set of circumstances. Ferrer et al. (Citation2023) examined what constituted extreme work for Human Resource (HR) professionals themselves, and in turn the extent to which HR professionals were engaged in such work. The paper, which is based on a thematic analysis of interviews with 21 Australian HR managers, found that they experienced major organizational intensity and role complexity due to the requirement to manage multiple stakeholders, having to deal with dark side HR issues and major variations in the amount of work to be undertaken. This posed significant issues for health and wellbeing. Finally, Win et al. (Citation2024) view extreme workers as those professionals who contribute to their works beyond acceptable contractual obligations, either voluntarily for personal rewards or involuntarily due to the menace of penalty, or both. They investigated how accounting professionals in India legitimize extreme work in their workplaces using exploratory qualitative research methods and the applied economies of worth theoretical framework. Our findings demonstrate that senior accounting professionals with the assistance of professional associations can play a key role in mobilizing professional and organizational resources to tackle extreme work in their accounting firms and the wider industry.

Where to next? A look at future research avenues

The 12 papers published in this Special Issue, in addition to the typology derived from our systematic review, provide a foundation for a future research agenda. In the case of the task/relationship-internal quadrant, there is significant scope to focus on backstage as well as frontline employees, and to understand extreme work in different contexts including manufacturing and not-for-profit organizations and to investigate physical discrete context more comprehensively. Scholars have given primacy to the investigation of objective type outcomes of extreme work arising from tasks and relationships as dimensions of discrete context, but less from the physical component of discrete context. There is scope for further investigation of subjective type internal outcomes such as alienation, counterproductive work behaviors and unethical and destructive behaviors. In the case of task/relationship-external quadrant, there is significant scope to investigate a broader range of short and long- term external outcomes including life satisfaction, long term career changes, impacts on unemployment and engagement in the labor market, impacts on access external education opportunities, long term willing and health impacts. There is also potential to investigate outcomes related to occupational stigma, professional reputation and standing, personal identity and multiple aspects of the work-family nexus.

In the case of the organization/environment-internal quadrant, scholars can be more explicit in analyzing aspects of the environment context such as investigation of formal and informal institutions. Examples of formal institutions include labor market characteristics, the impacts of government policies, the role of professional organizations, country specific human capital development, trade unions, external auditing and compliance processes, legislative influences and national regulation of employment standards. Examples of the informal dimension include aspects of international culture, ideas around decent work and fair work, generational differences and societal expectations. At the level of the organization, there is limited understanding of the impacts of strategy, organizational culture and the role of HRM practice in shaping extreme work. To date, scholars have investigated objective and subjective internal outcomes; however, there is scope to explore these outcomes over time and to track, in particular, subjective internal outcomes including engagement, job satisfaction and turnover intentions. In the case of the organization/environment-external quadrant, scholars can link dimensions of omnibus context to a wider range of external outcomes such as wellbeing over time, impacts on external career development and advancement and mobility, long-term impacts on physical health, impacts on the reputation of jobs and professional areas and impacts on different types of occupational stigma.

Our review and the papers included in this Special Issue has highlighted significant opportunities for methodological advancement including the use of mixed methods, longitudinal study designs, the use of national and international data sets and comparative country case studies. Much of the existing research is based on cross-sectional research designs and limited data sources and method triangulation. Most studies in terms of country come from the USA, Canada, Australia, Europe, UK and Japan. We have few insights from the Middle East, Africa, India, China, South America and a significant number of Asian countries. The papers included in the Special issue used quantitative and qualitative methodologies with a bias toward the latter. The primary qualitative methods used were semi-structured interviews and organizational document. We included papers that investigated dimensions of extreme in countries such as India, Brazil, Chile, Australia and the UK and they reported findings from unique contexts including employees engaged in dirty work in the favellas in Brazil, HR managers in Pakistan, academic in Ireland, Nurses in Egypt, China and Australia, accountants in India and paramedics in Australia. We therefore capture dimensions of extreme work in multiple occupations, organizational contexts and countries.

Implications for practice

As we have noted, the focus of this Special Issue has been on the exploration and conceptual clarification of ‘extreme’ work. This is also important from a practical perspective as it increasingly defines what is progressively seen as ‘normal’ or mainstream work (Caligiuri et al., Citation2020; Carnevale & Hatak, Citation2020). This Special Issue has highlighted in several direction and dimensions just how this is impacting on work. Again, from a practical perspective this is important in helping us to understand the role of HRM in exacerbating or alleviating the outcomes of extreme work. While the COVID-19 pandemic is often identified as a catalyst in how we understand extreme work, we would argue that it has more likely accelerated changes already in progress. In particular, COVID-19 has resulted in the significant blurring of the lines between work and non-work time, work and non-workspace and work and non-workplace. As these borders melt away, it is increasingly difficult to distinguish where one stops and the other starts (Grant et al., Citation2023). As such, it has drawn more attention to these issues that might have otherwise been the case (Farivar et al., Citation2023; McPhail et al., Citation2023). We hope that this set of eclectic papers provides fertile ground to HR practitioners in this emerging world of work, to explore these changes from their own perspective.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alfes, K., Shantz, A. D., & Ritz, A. (2018). A multilevel examination of the relationship between role overload and employee subjective health: The buffering effect of support climates. Human Resource Management, 57(2), 659–673. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21859

- Allan, B., Batz-Barbarich, C., Sterling, H., & Tay, L. (2018). Outcomes of meaningful work: A meta-analysis. Journal of Management Studies, 56(3), 500–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12406

- Bader, B., Schuster, T., Bader, A. K., & Shaffer, M. (2019). The dark side of expatriation: Dysfunctional relationships, expatriate crises, predjudice and a VUCA world. Journal of Global Mobility, 7(2), 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1108/JGM-06-2019-070

- Bader, B., Schuster, T., & Dickmann, M. (2019). Managing people in hostile environments: Lessons learned and new grounds in HR research. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(20), 2809–2830. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2018.1548499

- Balducci, C., Avanzi, L., & Fraccaroli, F. (2018). The individual “costs” of workaholism: An analysis based on multisource and prospective data. Journal of Management, 44(7), 2961–2986. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316658348

- Bell, S. T., Fisher, D. M., Brown, S. G., & Mann, K. E. (2018). An approach for conducting actionable research with extreme teams. Journal of Management, 44(7), 2740–2765. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316653805

- Bittman, M., Brown, J., & Wajcman, J. (2009). The mobile phone, perpetual contact and time pressure. Work Employment & Society, 23(4), 673–691. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017009344910

- Blanco-Donoso, L. M., Hodzic, S., Garrosa, E., Carmona-Cobo, I., & Kubicek, B. (2023). Work Intensification and Its Effects on Mental Health: The Role of Workplace Curiosity. Journal of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2023.2235069

- Blagoev, B. & Schreyögg, G. (2019). Why do extreme work hours persist? Temporal uncoupling as a new way of seeing. Academy of Management Journal, 62(6), 1818–1847. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2017.1481

- Blagoev, B., Muhr, S. L., Ortlieb, R., & Schreyögg, G. (2018). Organizational working time regimes: Drivers, consequences and attempts to change patterns of excessive working hours. German Journal of Human Resource Management: Zeitschrift Für Personalforschung, 32(3–4), 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/2397002218791408

- Boddy, C., Miles, D., Sanyal, C., & Hartog, M. (2015). Extreme managers, extreme workplaces: Capitalism, organizations and corporate psychopaths. Organization, 22(4), 530–551. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508415572508

- Bolt, E. E. T., Winterton, J., & Cafferkey, K. (2022). A century of labour turnover research: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Management Reviews, 24(4), 555–576. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12294

- Bouwmeester, O., Atkinson, R., Noury, L., & Ruotsalainen, R. (2021). Work-life balance policies in high performance organisations: A comparative interview study with millennials in Dutch consultancies. German Journal of Human Resource Management: Zeitschrift Für Personalforschung, 35(1), 6–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/2397002220952738

- Brunetto, Y., Farr-Wharton, B., Wankhade, P., Saccon, C., & Xerri, M. (2022). Managing emotional labour: The importance of organisational support for managing police officers in England and Italy. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 34(4), 832–854. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2022.2047755

- Bunner, J., Prem, R., & Korunka, C. (2018). How work intensification relates to organization-level safety performance: The mediating roles of safety climate, safety motivation, and safety knowledge. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2575. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02575

- Burrow, R., Williams, R., & Thomas, D. (2020). Stressed, depressed and exhausted: Six years as a teacher in UK state education. Work Employment and Society, 34(5), 949–958. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017020903040

- Cai, M., Tartanoglu Bennett, S., Stroleny, A., & Tindal, S. (2023). Between mundane and extreme: The nature of work on the UK supermarket frontline during a public health crisis. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2023.2250988

- Cai, M., Velu, J., Tindal, S., & Bennett, S. T. (2021). ‘It’s like a war zone’: Jay’s liminal experience of normal and extreme work in a UK supermarket during the COVID-19 pandemic. Work Employment and Society, 35(2), 386–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017020966527

- Caligiuri, P., De Cieri, H., Minbaeva, D., Verbeke, A., & Zimmermann, A. (2020). International HRM insights for navigating the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for future research and practice. Journal of International Business Studies, 51(5), 697–713. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-020-00335-9

- Carnevale, J. B., & Hatak, I. (2020). Employee adjustment and well-being in the era of COVID-19: Implications for human resource management. Journal of Business Research, 116, 183–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.037

- Chartered Association of Business Schools. (2021). Academic journal guide [Online].

- Collier, D., LaPorte, J., & Seawright, J. (2012). Putting typologies to work: Concept formation, measurement, and analytic rigor. Political Research Quarterly, 65(1), 217–232. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23209571 https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912912437162

- Cooke, H. (2006). Seagull management and the control of nursing work. Work, Employment and Society, 20(2), 223–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017006064112

- Crust, L., Swann, C., & Allen-Collinson, J. (2019). Mentally tough behaviour in extreme environments: Perceptions of elite high-altitude mountaineers. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(3), 334–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2018.1494622

- de Ruyter, A., Kirkpatrick, I., Hoque, K., Lonsdale, C., & Malan, J. (2008). Agency working and the degradation of public service employment: The case of nurses and social workers. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(3), 432–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190801895510

- Dickmann, M., Parry, E., & Keshavjee, N. (2019). Localization of staff in a hostile context: An exploratory investigation in Afghanistan. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(11), 1839–1867. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1291531

- Driskell, T., Salas, E., & Driskell, J. E. (2018). Teams in extreme environments: Alterations in team development and teamwork. Human Resource Management Review, 28(4), 434–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.01.002

- Dugan, A., Decker, R., Zhang, Y., Lombardi, C., Garza, J., Laguerre, R., Suleiman, A., Namazi, S., & Cavallari, J. (2022). Precarious work schedules and sleep: A study of unionized full-time workers. Occupational Health Science, 6(2), 247–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-022-00114-y

- Dupret, K., & Pultz, S. (2021). Hard/heart worker: Work intensification in purpose-driven organizations. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal, 16(3/4), 488–508. https://doi.org/10.1108/QROM-07-2020-1989

- Fan, S. X., Chan, X. W., Murray, L., Houlihan, T., & Gai, S. (2023). Supporting the support services providers: Exploring the invisible aspects of work extremity of social workers. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2023.2237887

- Farivar, F., Eshraghian, F., Hafezieh, N., & Cheng, D. V. (2023). Constant connectivity and boundary management behaviors: The role of human agency. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2023.2271835

- Felix, B., Fernandes, T., & Mansur, J. (2023). Building (and breaking) a vicious cycle formed by extreme working conditions, work intensification, and perceived well-being: A study of dirty workers in Brazilian favelas. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2023.2237864

- Ferrer, J., Saville, K., & Pyman, A. (2023). The HR professional at the centre of extreme work: Working intensely? The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2023.2241813

- Fitzgerald, S., McGrath-Champ, S., Stacey, M., Wilson, R., & Gavin, M. (2019). Intensification of teachers’ work under devolution: A ‘tsunami’ of paperwork. Journal of Industrial Relations, 61(5), 613–636. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185618801396

- Gascoigne, C., Parry, E., & Buchanan, D. (2015). Extreme work, gendered work? How extreme jobs and the discourse of ‘personal choice’ perpetuate gender inequality. Organization, 22(4), 457–475. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508415572511

- Gluschkoff, K., Hakanen, J. J., Elovainio, M., Vanska, J., & Heponiemi, T. (2022). The relative importance of work-releated psychosocial factors in physician burnout. Occupational Medicine-Oxford, 72(1), 28–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kgab147

- Golden, S. J., Chang, C. H., & Kozlowski, S. W. J. (2018). Teams in isolated, confined, and extreme (ICE) environments: Review and integration. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(6), 701–715. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2288

- Grant, K., McQueen, F., Osborn, S., & Holland, P. (2023). Re-configuring the jigsaw puzzle: Balancing time, pace, place and space of work in the Covid-19 era. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 0143831X231195686. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X231195686

- Granter, E., Wankhade, P., McCann, L., Hassard, J., & Hyde, P. (2019). Multiple dimensions of work intensity: Ambulance work as edgework. Work Employment and Society, 33(2), 280–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017018759207

- Green, F., Felstead, A., Gallie, D., & Henseke, G. (2022). Working still harder. ILR Review, 75(2), 458–487. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793920977850

- Huo, M. L., Boxall, P., & Cheung, G. W. (2022). Lean production, work intensification and employee wellbeing: Can line-manager support make a difference? Economic and Industrial Democracy, 43(1), 198–220, Article 0143831x19890678. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X19890678

- Harvey, C. L., Baret, C., Rochefort, C. M., Meyer, A., Ausserhofer, D., Ciutene, R., & Schubert, M. (2018). Discursive practice - lean thinking, nurses’ responsibilities and the cost to care. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 32(6), 762–778. https://doi.org/10.1108/jhom-12-2017-0316

- Hassard, J., & Morris, J. (2020). Corporate restructuring, work intensification and perceptual politics: Exploring the ambiguity of managerial job insecurity. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 41(2), 323–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X17710733

- Hewlett, S. A., & Luce, C. B. (2006). Extreme jobs - The dangerous allure of the 70-hour workweek. Harvard Business Review, 84(12), 49–59, 162.

- Holland, P. J., Tham, T. L., & Gill, F. J. (2018). What nurses and midwives want: Findings from the national survey on workplace climate and well-being. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 24(3), Article e12630. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12630

- Johns, G. (2006). The essential impact of context on organizational behavior. Academy of Management Review, 31(2), 386–408. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.20208687

- Karatepe, O. M. (2013). The effects of work overload and work-family conflict on job embeddedness and job performance: The mediation of emotional exhaustion. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 25(4), 614–634. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596111311322952

- Kellogg, K. C. (2022). Local Adaptation Without Work Intensification: Experimentalist Governance of Digital Technology for Mutually Beneficial Role Reconfiguration in Organizations. Organization Science. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2021.1445

- Kelliher, C., & Anderson, D. (2010). Doing more with less? Flexible working practices and the intensification of work. Human Relations, 63(1), 83–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709349199

- Khan, M., Usman, M., Shafique, I., Ogbonnaya, C., & Roodbari, H. (2023). Can HR managers as ethical leaders cure the menace of precarious work? Important roles of sustainable HRM and HR manager political skill. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2023.2241821

- Kniffin, K. M., Narayanan, J., Anseel, F., Antonakis, J., Ashford, S. P., Bakker, A. B., Bamberger, P., Bapuji, H., Bhave, D. P., Choi, V. K., Creary, S. J., Demerouti, E., Flynn, F. J., Gelfand, M. J., Greer, L. L., Johns, G., Kesebir, S., Klein, P. G., Lee, S. Y., … Vugt, M. V (2021). COVID-19 and the workplace: Implications, issues, and insights for future research and action. The American Psychologist, 76(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000716

- Lawrence, D. F., Loi, N. M., & Gudex, B. W. (2019). Understanding the relationship between work intensification and burnout in secondary teachers. Teachers and Teaching, 25(2), 189–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2018.1544551

- Lee, W., Lee, J., Kim, H. R., Lee, Y. M., Lee, D. W., & Kang, M. Y. (2021). The combined effect of long working hours and individual risk factors on cardiovascular disease: An interaction analysis. Journal of Occupational Health, 63(1), e12204. https://doi.org/10.1002/1348-9585.12204

- Le Fevre, M., Boxall, P., & Macky, K. (2015). Which workers are more vulnerable to work intensification? An analysis of two national surveys. International Journal of Manpower, 36(6), 966–983. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-01-2014-0035

- Mackenzie, E., McGovern, T., Small, A., Hicks, C., & Scurry, T. (2021). ‘Are they out to get us?’ Power and the ‘recognition’ of the subject through a ‘lean’ work regime. Organization Studies, 42(11), 1721–1740, Article 0170840620912708. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840620912708

- Mariappanadar, S. (2014). Stakeholder harm index: A framework to review work intensification from the critical HRM perspective. Human Resource Management Review, 24(4), 313–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2014.03.009

- Mauno, S., Kubicek, B., Minkkinen, J., & Korunka, C. (2019). Antecedents of intensified job demands: evidence from Austria. Employee Relations, 41(4), 694–707. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-04-2018-0094

- Mccann, L., Morris, J., & Hassard, J. (2008). Normalized intensity: The new labour process of middle management. Journal of Management Studies, 45(2), 343–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00762.x

- McPhail, R., Chan, X. W., May, R., & Wilkinson, A. (2023). Post-COVID remote working and its impact on people, productivity, and the planet: An exploratory scoping review. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 35(1), 154–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2023.2221385

- Mousa, M., Arslan, A., Abdelgaffar, H., Luna, J. P., & Velasquez, B. (2023). Extreme work environment and career commitment of nurses: Empirical evidence from Egypt and Peru. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 32(1), 58–79. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-08-2022-3400

- Mousa, M., Arslan, A., Cooper, C. & Tarba, S. (2023). Live like an ant to eat sugar: nurses’ engagement in extreme work conditions and their perceptions of its ethicality, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 35(2), 309–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2023.2237877

- Ogbonna, E., & Harris, L. C. (2004). Work intensification and emotional labour among UK university lecturers: An exploratory study. Organization Studies, 25(7), 1185–1203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840604046315

- Pariona-Cabrera, P., Bartram, T., Cavanagh, J., Halvorsen, B., Shao, B., & Yang, F. (2023). The effects of workplace violence on the job stress of health care workers: Buffering effects of wellbeing HRM practices. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2023.2237876

- Pasamar, S., Johnston, K., & Tanwar, J. (2020). Anticipation of work-life conflict in higher education. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 42(3), 777–797. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-06-2019-0237

- Paškvan, M., Kubicek, B., Prem, R., & Korunka, C. (2016). Cognitive appraisal of work intensification. International Journal of Stress Management, 23(2), 124–146. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039689

- Pickering, C., & Byrne, J. (2014). The benefits of publishing systematic quantitative literature reviews for PhD candidates and other early-career researchers. Higher Education Research & Development, 33(3), 534–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2013.841651

- Pollock, K., Nielsen, R., & Wang, F. (2023). School principals’ emotionally draining situations and student discipline issues in the context of work intensification. Educational Management Administration & Leadership. https://doi.org/10.1177/17411432231165691

- Putnam, L. L., Myers, K. K., & Gailliard, B. M. (2014). Examining the tensions in workplace flexibility and exploring options for new directions. Human Relations, 67(4), 413–440. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726713495704

- Rodriguez, J. K., Procter, S., & Arrau, G. (2023). Doing extreme work in an extreme context: Situated experiences of Chilean frontline healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2023.2237863

- Root, L. S., & Wooten, L. P. (2008). Time out for family: Shift work, fathers, and sports. Human Resource Management, 47(3), 481–499. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20228

- Saritas, C. T. (2020). Precarious contours of workfamily conflict: The case of nurses in Turkey. Economic and Labour Relations Review, 31(1), 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1035304619879327

- Sheerin, C., & Linehan, M. (2023). ‘Everyone should have a wife’–Extreme work, eldercare, and the gendered academy in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2023.2237865

- Stacey, M., Wilson, R., & McGrath-Champ, S. (2022). Triage in teaching: The nature and impact of workload in schools. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 42(4), 772–785. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2020.1777938

- Telford, L., & Briggs, D. (2022). Targets and overwork: Neoliberalism and the maximisation of profitability from the workplace. Capital & Class, 46(1), 59–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/03098168211022208

- Tham, T. L., Alfes, K., Holland, P., Thynne, L., & Vieceli, J. (2023). Extreme work in extraordinary times: The impact of COVID-stress on the resilience and burnout of frontline paramedic workers - the importance of perceived organisational support. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2023.2237871

- Thompson, G., Mockler, N., & Hogan, A. (2022). Making work private: Autonomy, intensification and accountability. European Educational Research Journal, 21(1), 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904121996134

- Townsend, K., & Loudoun, R. (2023). Line managers and extreme work: A case study of human resource management in the police service. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2023.2251875

- Valli, L., & Buese, D. (2007). The changing roles of teachers in an era of high-stakes accountability. American Educational Research Journal, 44(3), 519–558. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30069427 https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831207306859

- Wang, F., Pollock, K., & Hauseman, C. (2021). Complexity and volume: Work intensification of vice-principals in Ontario. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2021.1974097

- Wankhade, P., Stokes, P., Tarba, S., & Rodgers, P. (2020). Work intensification and ambidexterity - the notions of extreme and ‘everyday’ experiences in emergency contexts: Surfacing dynamics in the ambulance service. Public Management Review, 22(1), 48–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1642377

- Ward, J., McMurray, R., & Sutcliffe, S. (2020). Working at the edge: Emotional labour in the spectre of violence. Gender, Work & Organization, 27(1), 82–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12377

- Willis, E., Toffoli, L., Henderson, J., Couzner, L., Hamilton, P., Verrall, C., & Blackman, I. (2016). Rounding, work intensification and new public management. Nursing Inquiry, 23(2), 158–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/nin.12116

- Win, S., Chhatbar, M., Parajuli, M. A., & Clement, S. (2024). Accounting professionals’ legitimacy maintenance of modern slavery inspired extreme work practices in an emerging economy. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2024.2319794

- Zhang, X. Y., Chen, X., Dai, L. Y., Long, Y. L., Wang, Z., & Shindo, K. (2023). The effect of work stress on turnover intention amongst family doctors: A conditional process analysis. International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 38(5), 1300–1313. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.3652