ABSTRACT

There is a paucity of research that has effectively listened to children's voices on matters important to them and has asked them how they would like to be listened to. This study used a playful approach to listen to children's voices about play spaces in their primary school. The research questions were: •How can a playful approach be used to listen to children's voices about what children would like their new play space to look like? •Why did children choose particular resources to communicate their thoughts about those spaces?Forty-two primary school children (ages 5-6 years) chose which method/s they would like to engage with to share their voices from blocks, clay, drawings, percussion instruments and loose parts storytelling. In line with our Playful Research Ethics Framework (PREF), interactive ethics sessions were delivered using puppets, music and Makaton and on-going assent was monitored.This article focuses on clay and blocks data; children's favourite and preferred methods to listen to their voices. Rich data were collected through artefacts, photographs and conversations. The findings suggest that incorporating a playful approach and providing multiple ateliers and resources to choose from, can ensure children's voices can be heard and amplified.The study makes several original contributions, namely, designing a Playful Research Ethics Framework, aligning the research design of multiple ateliers with free-flow play and including a large sample size. This study also highlighted children's agency within the research process as children chose how and when their voices should be heard, and invited children to share their preferences for being listened to in future.

Introduction

Research aiming to listen to children’s voices

Listening to a child is an active process which involves mutual communication between the child and adult (or child and child), can include verbal and non-verbal forms, and is considered to be the first step towards children’s participation (Clark Citation2005; Citation2017). Despite claiming to listen to the voices of young children, a recent systematic literature review found that in most of the 74 studies over the period of 2015 and 2020, there was limited evidence of listening to children’s voices (Urbina-Garcia et al. Citation2022). Even when children’s voices were ‘listened to’, authors had used adult-led methods of data collection such as, individual structured and semi-structured interviews (although some used photos, puppets and play-based interviews), and group interviews (similar props), observations and projective techniques. Others used, what can be seen to be child-led ways of listening to their views, such as film-based discussions, children taking photos, draw and tell, school–home or local area tours, and story completion. However, one could argue that they were still adult-led as they were initiated by the researchers with potential power dynamics coming into play, either from the researcher, teacher or in some cases family (Lundy Citation2007), with no option of selecting their preferred method/s from a range of methods and resources (e.g. Burke et al. Citation2024).

Further, it seems to be common practice to use other sources of corroboration or verification of children’s narratives, through triangulation of their data through researcher observations and/or collecting data from other adults (e.g. teachers or parents). This suggests that either the researchers were not confident about young children’s ability to articulate their perspectives about their own lived experiences and/or were not confident about their own ability to understand young children’s perspectives. Either way, it seems that even researchers who aimed to listen to the voices of children were doing it within specified boundaries drawn by them.

It is important to note that there is some evidence of children’s views being different to adults’ views highlighting the significance of listening to their voices (Urbina-Garcia et al. Citation2022). Further, as Hammarsten et al. (Citation2019) have highlighted, there can be additional advantages of approaches aimed at listening to children’s voices (e.g. through walk and talk and taking photos using a tablet); researchers can have those experiences alongside children as well as passing some control over to them by enabling active participation. However, they did not highlight later whether they were actually advantageous and/or effective in doing so, and from whose perspective. Similarly, other research has not clearly articulated children’s views of their choice of resources to communicate their views, thereby missing the opportunity to hear from them first-hand what was of interest to them (Lundy Citation2007; Lundy and McEvoy Citation2012). Therefore, it is imperative to not only use playful approaches to listen to children’s voices about issues of importance to them (Jindal-Snape Citation2012), but also to listen to their voices about their preferences about particular resources. Without doing so, we risk being complacent in our own views of which playful resources should be used, and to what degree they are meaningful for young children (Jindal-Snape Citation2012).

This article meets this gap in research by providing two types of data: (i) visual and verbal data about children’s choice of resources to communicate additions to their play spaces, and (ii) children’s reflective accounts of why they chose that particular resource.

Playful approaches to early childhood research

Most children in Scotland, where this study was undertaken, like elsewhere in the world, would be used to play pedagogies since nursery (Burns Citation2022). This however does not fully translate to the pedagogy they experience in early primary school, despite it being promoted due to its focus on child-centred pedagogy and children’s voices (OECD Citation2017). Using play pedagogy to inform research is desirable as it ensures the use of the approach and resources that children are familiar with, as well as have expertise in, so that they can participate actively in sharing their views.

In this context, one of the most well-respected and well-known child-friendly methods of listening to children’s voices in research is Clark’s ‘mosaic approach’ (e.g. Citation2004; Citation2017; Clark and Moss Citation2005). The mosaic approach is a participatory research method which aims to capture children’s voices through multiple data collection methods (e.g. observations, tours, mapping, ‘magic carpet’), and multiple perspectives (e.g. children, educators and parents/carers).

Similarly, Blaisdell et al. (Citation2019) highlight the relevance of creative, arts-based approaches in listening to children more effectively. Previous research suggests that participation in creative activities can support children in safe exploration of their feelings and views, which can in turn have a positive impact on their wellbeing (Robb et al. Citation2023; Jindal-Snape et al. Citation2013). Other studies reported that children in a creative and playful environment were prepared to spend longer on open tasks compared to the control group experiencing a structured and didactic environment (Whitebread et al. Citation2009), and that it fostered children’s sense of autonomy (Cremin, Burnard, and Craft Citation2006), increased their confidence to use a range of material (Bancroft, Fawcett, and Hay Citation2008), and enhanced their active participation throughout the research process (Pyle Citation2013).

These advantages made the use of a playful approach highly pertinent to this study. However, it is important to be mindful that although open-ended playful activities can ensure that children’s voices are listened to, there can be potential ‘tensions’ due to the researcher’s own agenda (which in the main is not open-ended) as well as how their ‘methods and assumptions shape what “voices” are produced and included’ (Blaisdell et al. Citation2019, 28).

Therefore, we undertook a study that used a playful approach to listen to young children’s views about play spaces in their primary school. To build on previous research in this area, such as the mosaic approach, we also incorporated a cycle of reflection to explore children’s views of preferred resource/s. The main research questions were:

How can a playful approach be used to listen to children’s voices about what children would like their new play space to look like? Why did children choose particular resources to communicate their thoughts about those spaces?

Materials and methods

Theoretically, this study was informed by the four dimensions of voice proposed by Lundy (Citation2007): (i) opportunity (space) to provide their voices about a playful approach, (ii) creating ways to facilitate their participation and contribution (voice), (iii) listening to the voices (audience), and (iv) acting upon it in our future research (influence). Wall and colleagues’ eight principles also influenced this study, namely, definition, power, inclusivity, listening, time and space, approaches, processes, and purposes (Blaisdell et al. Citation2019; Wall, Lorna, and Kanyal Citation2017). Some examples include, how we conceptualised voice as a contested construct but also understanding it as socially constructed, acknowledging power and finding ways to mitigate for it through multiple playful methods (including for ethics), providing time on the day and throughout the week to ensure active listening to the voices of all children. Further, we were mindful that voice is a dialogical activity which requires a speaker, audience and a relationship between the two (Bakhtin Citation1986; Cohen and Uhry Citation2007).

The context of this study was to listen to children’s voices about play spaces in their primary school. To place power and control with children and to listen to their many voices and ‘languages’, multiple research ateliers and resources were presented for children to choose from over a week of data collection. Children had the opportunity to choose from blocks, clay, drawings, percussion and loose parts storytelling to share their voices, as these were indicated to be of preference by them previously (Burke et al. Citation2024, see ). Children could freely move to different ateliers. In this way, it is similar to the concept of ‘free-flow’ play (Bruce Citation2015). They were then invited to share their reasons for choosing particular resources. Further, after the study was complete, children were asked if/how they would like their voices and artefacts shared in a digital story format when disseminating the results. However, it is important to acknowledge that given the study was commissioned by the school, there was an adult-led agenda and although the ateliers were based on observation of which resources were used and preferred by the children (Burke et al. Citation2024), the ateliers presented to them were adult-led.

Table 1. Children’s voices being used to inform the data collection methods, process and dissemination.

Sample and recruitment

This study involved two primary one classes and two primary two classes (88 children, 5–7 years) in a primary school in Central Scotland. Forty-six parents and carers gave consent for their child to participate if they wished. After the playful ethics session, six children decided not to take part but then four again changed their mind and participated. Two, who initially consented, did not participate in any activities. Therefore, overall, 42 children participated.

A playful ethical approach

When conducting research with young children, ethical considerations become even more important. After the Research Ethics Committee at University of Dundee (SREC22-007) and the Local Authority granted approval, the school distributed information and consent forms to parents and carers via their School App. 46 parents and carers gave their consent.

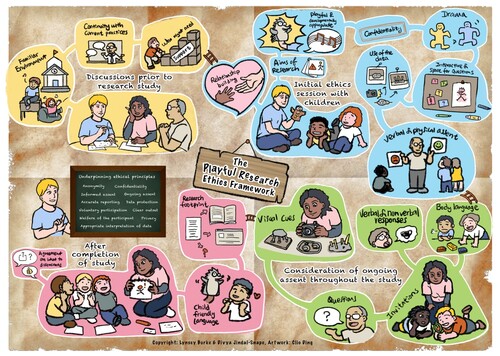

Tensions in the ethos of listening to children’s voices and the non-negotiable systems when working with the local authority and school were obvious, and inadvertently placed the power with the adults (Jago and Bailey Citation2001). We tried to mitigate this throughout the week by ensuring our ethical approach was underpinned by the Playful Research Ethics Framework (PREF) and used songs, puppets, games and movement to explain the purpose of the study and seek informed assent (Burke & Jindal-Snape 2023, ).

As can be seen from the framework, the initial ethics session was designed to be playful and therefore developmentally appropriate for a group of children of this age. The children were told that the 'Playful Researchers', distinguishable due to the pastel-coloured t-shirt they wore with their name on it, were there to:

- Look at the children playing

- Listen to the children playing

- Think about the children’s play

- Talk to the children about their play

In small groups, children were invited to ‘post’ their name on the wall display next to the activity symbols and puppets if they consented to participate. If they did not wish to participate, they were asked to place their names on a separate board.

On-going, informed assent was monitored throughout the week through children’s verbal and non-verbal body language. Children were also reassured that they need not feel pressured to say anything at all if they did not want to participate any longer; their silence was valued.

Data collection

Part of the reason the researchers were invited into the school to do this research project was to increase staff understanding of ways to listen to children’s voices through a playful approach. As such, the original intention was for staff members to participate and to be ‘familiar adults’ in the data collection process (e.g. Irwin and Johnson Citation2006; Leigh Citation2020). Whilst this was the intention, due to staffing shortages in the school, it was not possible for this to happen every day. However, the researchers, having been in the school for a week previously, were known adults, even though not well-known adults. Further, using less familiar adults in the data collection process can combat other potential tensions, such as power differentials that could exist with familiar adults (e.g. Gillett-Swan and Sargeant Citation2018).

To conduct the research, the adult sat near the children’s play space and interacted with them if they initiated engagement, mindful of voice being a mutual and active process (Clark Citation2005) but not making it adult-led. Five ateliers were set up, however, only two which the majority of children engaged with have been presented here due to the limits of the word count (see ). They were asked to respond to the following question using the different ateliers and resources, in this case, clay and blocks:

What would your new play space look like?

Table 2. Number of children/data collection method.

Clay atelier

Research exists which highlights the benefits of using clay as an open-ended material in the early years (e.g. Parker Citation2020; Tovey Citation2016). However, whilst clay has been used in other fields (e.g. Rößler, Pröhl, and Lötters Citation2018) and with different age groups (e.g. Bingley and Milligan Citation2007; Blaisdell et al. Citation2019), there is comparatively less literature on the use of clay specifically as a resource to listen to the primary school-aged children’s views. A clay atelier was set up on tables in the children’s open play space to provide opportunities to create their own clay artefacts or work with others. Each table had clay and a variety of tools, e.g. brushes of different sizes, wooden forks, specific clay carving and cutting tools, pipettes, etc. (see ). The clay was the air drying type, and completed artefacts were placed on open display shelves in the play space, with accompanying titles/labels explaining children’s creations in their own words.

Blocks atelier

There is a variety of research that exists which argues the benefits of blocks (either wooden or plastic) on children’s language (Christakis, Zimmerman, and Garrison Citation2007), mathematical/spatial skills (e.g. Ferrara et al. Citation2011; Park, Chae, and Boyd Citation2009) and creativity (e.g. Aksoy and Belgin Aksoy Citation2023). However, as with clay, a dearth of research exists which has used blocks as a way of listening to children’s voices. Children’s original play area and block shelves were used with additional items added, namely paper, rulers, measuring tapes (see ). Children could choose to come in on their own or with others, and choose any combination, size or number of blocks to convey meaning and share what their new play space might look like.

Children’s engagement with clay and blocks was documented through photographs and notes, to enable discussion with children later. (Please note, it was not to corroborate or verify their views.) When the children decided to move away from an atelier, they were asked reflective prompts used flexibly in conversation with them (Blaisdell et al. Citation2019; Leigh Citation2020), based on the following questions:

- Why did you use (clay, blocks) to tell us about your play spaces? How did you get on using the blocks/clay?

- What other resources would you have preferred?

At the end of the week, they were asked:

- What was your favourite resource and why?

Children’s responses were recorded using the Voices Notes function on an iPad and inserted alongside photographs of their artefacts.

Data analysis

Data reported here were derived from 20 children’s block data and 22 children’s clay data. Data from these resources were treated similarly and consisted of photographs of children’s artefacts, voice note reflections and scribing of their conversation during their play/creation at the ateliers. The voice notes were transcribed, transported into, and coded through QSR International’s NVivo 12 software along with the notes and photographs. These data were analysed in the first instance using Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2019) reflexive thematic analysis. However, an additional layer was incorporated using Brown and Collins’s (Citation2021) visuo-textual analysis framework, providing a rigorous and systematic approach to analysing the photographs of artefacts and their corresponding narratives.

Results and discussion

Clay and blocks were not only the most frequently used but also the majority of children’s favourite way of having their voice heard (see ).

Table 3. Preferences of data collection methods.

Clay

Three overarching themes were identified; children’s use of clay to convey views, children’s use of clay tools, and engagement with clay. For brevity, one to two examples will be used to illustrate each theme. Finally, we will present children’s reflections about their preference/s.

How the clay was used to convey views

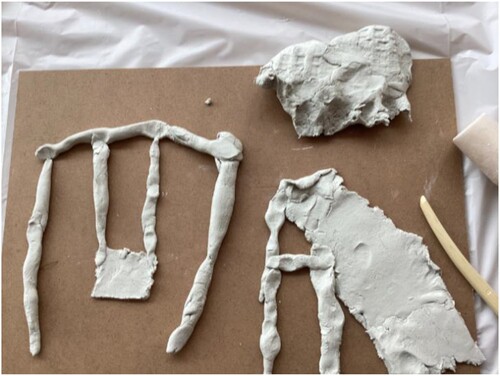

As is to be expected, the clay was used by the majority of children in a malleable way. Children used their hands and fingers to squash, flatten, roll, tease, pull, tear, pierce and separate ().

I would like Monkey bars for my play space. (Child 5)

In this way, clay was shown to be a flexible resource which provided children with the freedom to decide how they wanted to use it. A few children looked for ideas from their peers, teacher and researchers. This could suggest that they preferred to engage with it as a collaborative and dialogical activity (Cohen and Uhry Citation2007) or that prior to using any new playful approaches, exposure to and experience of the resource would be beneficial, so that children are more confident in expressing their voices through this medium. However, it is also possible that as data collection was taking place indoors, in an environment that is typically adult-led, children took on a more passive role, waiting to be ‘taught’ how to use the clay (Coad Citation2007) highlighting how their playfulness can be constrained by adults and primary school practices (Burns Citation2022).

Children’s views through clay tools

Of greater importance than the clay itself, was the selection and use of clay tools (see ).

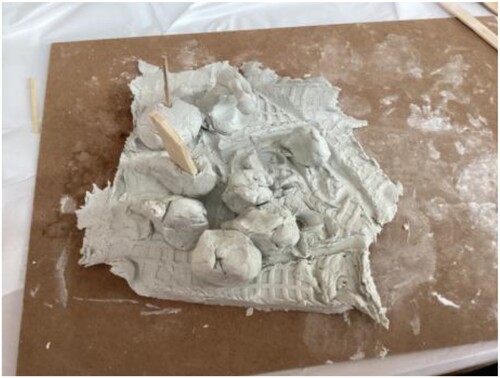

The tools seemed to be essential conduits to help children share their thoughts and ideas and were used in a variety of ways – to shape, mould, mark, cut, define, and to test out and experiment with a variety of ideas. Intricate details and patterns were consistently a feature of many artefacts ().

I made a fruit and veg kitchen. I would like it outdoors. In my kitchen I have made 2 strawberries, an orange, pepper and one watermelon. (Child 28, Voices notes, Clay data)

I made a maze because I really want people to get stuck in it but the entrance is a little square or rectangle but the end is a triangle. (Child 26, Voices Notes, Clay data)

Engagement with clay

Despite children’s relative unfamiliarity with clay as part of their usual school activity, they revealed incremental views of intelligence through their engagement with it (Dweck Citation1999), tending to persevere when its use presented them with challenges (Whitebread et al. Citation2009).

Further, children wanted to provide their voices clearly as can be seen from the precision and attention to detail of their artefacts, their perseverance and patience (Pyle Citation2013), alongside having fun - all recognised dispositions for developing thinking (Burke and Williams Citation2009; Costa and Kallick Citation2014; Perkins, Jay, and Tishman Citation1993) ().

This child (Child 24), during her reflections, also demonstrated her metacognitive awareness of the processes she had been through during the creation of the artefact (Burke and William Citation2012; Beyer Citation2008):

So first I made legs for the trampoline then I put some little sticks in it and then I made the trampoline but then someone helped me and she gave me some little bits to put at the bottom of the legs and that really helped me. Then it was for the tricky bit and I did it! (Child 24, Voices notes, Clay data)

Children seemed to have had fun and enjoyed engaging with the clay. They also took the opportunity to recreate their favourite objects, in line with their own, rather than the adult’s agenda ()

I made glowing jewellery by cutting it out and also by making the dots and the love heart. (Child 29, Voices notes, Clay data)

Children’s reflections on use of clay to communicate their views about their play spaces

Of the 22 children who chose to do this activity, 18 said they liked (or even loved) using the clay (four chose not to answer). Thirteen children also gave reasons for liking it: due to how it felt (e.g. ‘ … because it wasn’t that sticky’, Child 35); because they could use tools (e.g. ‘ … because I used the fork and the rolling thing and the mini one of those sticks and I also used the painting brush’, Child 19); because it was enjoyable (e.g. ‘ … it was fun and because you get to make things with it’, Child 44); because it was challenging (e.g. ‘ … it was so hard but I loved it and I loved making it’, Child 24).

When asked if there was any other way they would prefer to have their voices heard, only two children made specific suggestions.

I would like little pens to draw on the clay. (Child 16)

Rocks but nothing else. (Child 20)

It is interesting that during these final reflections, no child mentioned their preference due to the clay tools. This highlights the importance of listening to children’s voices not only once, but over a period of time, and especially after they have experienced a range of ateliers and resources. The latter also emphasises the importance of using multiple resources (Urbina-Garcia et al. Citation2022; Clark Citation2017).

Blocks

Five main themes emerged from an analysis of the blocks data; use of blocks to convey meaning; blocks as a provocation; engagement with blocks; incorporation of additional resources and using narratives alongside blocks.

Use of blocks to convey meaning

In general, most children began using the blocks with a clear idea of what they wanted to say and how they intended to use the blocks to say it ()

Child 23 led the play by suggesting (to Child 30) they make a Greek structure. They started off stacking the blocks. They worked together carrying and stacking the blocks, passing them to each other purposefully … (Researcher notes, Child 23, Blocks)

Blocks as a provocation

In contrast, a small number of children did not begin with a clear idea of what to create and played with the blocks before deciding on what to build. The idea was sometimes sparked by playing with the blocks, or by watching what other children were doing.

Child 43 began organising and putting down blocks in a row … He said (out loud, without any prompts) he didn’t know what he was building. He organised them all neatly in a square, then added long blocks on top. He worked silently, but with purpose, adding more and more blocks … Once he was satisfied, he said (out loud without any prompts), ‘It holds pencils and pens and glue sticks at the top’. (Researcher notes, Child 43, Blocks)

Engagement with blocks

The majority of the children persevered with the blocks so that they could convey their idea more clearly, even when it constituted a ‘problem’ to solve (Pyle Citation2013). For instance, rather than being dissuaded from using the blocks, Child 31 persevered so that he could convey exactly what he intended to bring his vision to life, overcoming significant structural and balance challenges ().

Loads of Monkey Bars with 3 levels. So the smallest level is for kids the second level can be for teenagers and the third level is for adults if they want to go. (Child 31, Blocks, Voices Notes)

Using narratives alongside blocks

Whilst some children were silent and communicated mainly through the blocks themselves, others provided a continuous narrative to accompany and explain the process as they were doing it without any adult prompts (see Cohen and Uhry Citation2007 on Bakhtinian Approach to dialogical engagement during block play), as in the case of a trio of boys when creating their shared vision (Child 3, 8 and 45). Child 8 worked with them but did not converse.

A secret hideout! I’m so excited! A secret games room is what can go inside it. A computer in it to play some games. Also we could pretend there’s a wee bit for us all to get our … (Child 3)

This is the walls, and the floor … Here’s a new adding bit – an underground bit and a box thing to get in. That wee eye ball is watching out (on the green paper) to see who’s coming. (Child 45)

I just can’t wait to see this actually in real life … It’ll be made from wood and cement. We will play games around it and in it. (Child 3)

This is reflective of Blaisdell et al.’s (Citation2019) view that when conducting arts-based research, process is more important than the final product.

The continuous narrative could also be seen during solitary participation, highlighting the importance of ‘social speech’, whether external (with peers) or internal (with self, see also Child 43’s verbalisation above) (Bakhtin Citation1986).

The train on the track is going to be the flying Scotsman. It’s gonna go through the muga, and right back to the station. There will be four stations. (Child 37, Blocks data)

Incorporating additional resources

Whilst some children created their structures entirely out of blocks, others looked for additional items to incorporate within/to add to their structure to ensure their meaning was clear. For instance, the trio of boys mentioned above (Child 3, 8, 45), added paper (for a spy camera), mesh and cardboard tarpaulin to make a roof ().

Similarly, Child 13 integrated a cardboard box as a key part of her ‘ball game’ design, saying, ‘You put balls in it and you have to catch them before they go in. You only get one shot’ ().

As with clay, there is perhaps an indication here that the children felt this resource is not enough on its own to enable them to convey their ideas closely enough, so they enhanced it with other objects. It is also potentially reflecting Clark’s view of the importance of using a range of approaches (or data collection methods) to afford children the opportunity to share a more holistic and potentially more accurate view of their thoughts (Citation2017). Alternatively, incorporating accessories into their models could simply reflect their block play stage of development (Johnson Citation1933).

Children’s reflections on use of blocks to communicate their views about their play spaces

Immediately after their creations were completed, 13 children (out of 20) responded positively that they liked using the blocks to have their voices heard. Reasons children gave for liking the blocks included a range of responses relating to function (e.g. ‘Because they can stack up on each other’, Child 13), benefits (e.g. ‘They are really stabler than the other blocks’, Child 3), and opportunities for creativity provided by the blocks (e.g. ‘Because you know it can make everything. You can even make what I want’, Child 33). It could be argued that the children gave reasons why they liked playing with the blocks in general, rather than as a way of having their voices heard in relation to the research study.

When asked if they would like to use another resource instead to give their ideas on their play space, the majority of children said no, however three said they preferred clay, e.g.

Clay. Because every time I see it in some videos it look so good with one colour and it looks like the clay is not so hard and they make it a wee bit softer. So, it’s very fun when I see it. (Child 31)

As mentioned earlier, at the end of the week, children were asked again to reflect on and choose their favourite resources. Eight children said blocks were their overall favourite, and the main reason given was because of the opportunities for creativity which blocks afforded (e.g. ‘ … you could build whatever you want’, Child 30).

Only one child said that using the blocks to share his ideas was, ‘a wee bit tricky … I needed to make it up half the wooden top. Then I added a wee ramp to it and that made the chute … I built it using the real tiny blocks’ [so it was hard to balance] (Child 27).

This suggests that overall blocks were seen to be an appropriate resource to communicate their views by young children. However, including a variety of other resources for children to incorporate into their block structures could enhance children’s engagement and provide additional opportunities to express their ideas further.

Conclusions

The study focussed on listening to children’s voices about their play spaces using a playful approach and their voice about their preferred resources. This study is significant as it adds further evidence to existing literature that children are capable and willing to have their voices heard through a playful approach as well as articulating their preference and reasons for that preference. It provides data (both verbal and visual) about the use of clay and blocks as part of a playful approach that can be used by others (after consultation with children), the reasons behind their preference and what could be used instead of, or in combination with, the resources used in this study, i.e. clay and blocks. Further, it provides exemplars of how providing multiple ateliers and resources to choose from, and incorporating free-flow play and play pedagogy in primary school can ensure children’s voices can be heard by schools and researchers.

However, the study is not without its limitations. The tension between the researchers’ belief about children’s voices and non-negotiable systemic rules regarding parental consent was challenging. However, it also provided us the motivation to create a Playful Research Ethics Framework. Despite the focus on a playful approach, the reflective prompts were researcher-led, although some children choosing not to respond to them suggests that their agency came into play. Further, despite providing a range of ateliers and resources based on observation of children’s preferences for a week before data collection started, one could argue that the resources were still researcher-led. Additionally, although as researchers we actively listened as their audience and children’s voices will influence the conduct of our research in future, we are mindful that this might not be the case for their voices regarding their play spaces.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study makes an important contribution by providing a Playful Research Ethics Framework that can assist other researchers (and educators) in ensuring children have an understanding of, and voice in, deciding whether to participate in a research study or not.

Further, it contributes to other research in the area of playful approaches in early childhood education. Blocks and clay have been used in previous research, but typically to do with specific domains (e.g. blocks related to mathematical thinking, clay for arts). In this study, they were used to listen to children’s multiple languages about their play spaces. Furthermore, while there is an emerging area within research looking at how children’s reflections can feed into research evaluations, there is little research that provides an insight into children’s views of what resources they prefer and how they might like their voices to be heard. This study is unique due to the large number of children involved in the study, and in its design of multiple ateliers over a week which allowed children to not only engage with different resources, their preferences and reasons for engagement also came through clearly.

There are several implications for researchers (as well as educators) who would like to listen to the voices of young children by providing them space, voices, audience and influence, especially in terms of what resources should be used and how.

Firstly, there needs to be consideration of children’s level of familiarity with the resources prior to the actual data collection. One possibility is to use resources which children have experience of in their everyday play spaces and classrooms. Otherwise, there should be time taken at the start for children to ‘play’ and experiment with the resources, prior to undertaking data collection. Notwithstanding that, children in this study did use new resources like clay effectively, perhaps due to its open-ended nature and the choice and opportunities it provided for play and creativity. According to the children, they preferred to use clay due to its texture, enjoyment, tools that can be used with clay and the challenge it provided them.

Secondly, future research should continue to present children with a variety of different ateliers and resources from which children can choose which ones they wish to engage with and how. Children should be given as many choices as possible about how they would like to have their voices heard on matters that concern them.

Thirdly, slow pedagogies and ‘wallowing’ are central to a play pedagogy. These key features of play pedagogies are no less important when considering a playful approach to research. Children need to be given the space and time to reflect on their ideas and to demonstrate sustained engagement in play. This should include being given the opportunity to return to the data if necessary, similar to the ‘work in progress’ labels that children are accustomed to placing on their creations during class time.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aksoy, Merve, and Ayşe Belgin Aksoy. 2023. “An Investigation on the Effects of Block Play on the Creativity of Children.” Early Child Development and Care 193 (1): 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2022.2071266.

- Bakhtin, Mikhail Mikhaĭlovich. 1986. Speech Genres and Other Late Essays. Texas: University of Texas press.

- Bancroft, Susi, Mary Fawcett, and Penny Hay. 2008. Researching Children Researching the World: 5(5(5=Creativity. Stoke-on-Trent: Trentham.

- Beyer, Barry. K. 2008. “What Research Tells Us about Teaching Thinking Skills.” The Social Studies 99 (5): 223–232. https://doi.org/10.3200/TSSS.99.5.223-232

- Bingley, Amanda, and Christine Milligan. 2007. “Sandplay, Clay and Sticks’: Multi-Sensory Research Methods to Explore the Long-Term Mental Health Effects of Childhood Play Experience.” Children's Geographies 5 (3): 283–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733280701445879.

- Blaisdell, Caralyn, Lorna Arnott, Kate Wall, and Carol Robinson. 2019. “Look Who’s Talking: Using Creative, Playful Arts-Based Methods in Research with Young Children.” Journal of Early Childhood Research 17 (1): 14–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X18808816

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2019. “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11 (4): 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Brown, Nicole, and Jo Collins. 2021. “Systematic Visuo-Textual Analysis – A Framework for Analysing Visual and Textual Data.” The Qualitative Report 26 (4): 1275–1290.

- Bruce, Tina. 2015. Early Childhood Education (5th ed.). Hachette: Hodder Education.

- Burke, L., D. Jindal-Snape, A. Lindsay, S. Whyte, M. Wallace, D. Mercieca, M. McKenzie, and B. Keatch. 2024. “Spaces for Play: Listening to Children’s Voices.” Education 3-13: 1–24. http://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2024.2318254.

- Burke, L. A., and J. M. Williams. 2009. “Developmental Changes in Children’s Understandings of Intelligence and Thinking Skills.” Early Child Development and Care 179 (7): 949–968. http://doi.org/10.1080/03004430701635491.

- Burke, L. A., and J. M. Williams. 2012. “Two Thinking Skills Assessment Approaches: “Assessment of Pupils’ Thinking Skills” and “Individual Thinking Skills Assessments”.” Thinking Skills and Creativity 7 (1): 62–68.

- Burns, Marion. 2022. “Ready or Not to Adopt a Pedagogy of Play for Children Starting School in Scottish Primary Schools – Is This a Major Transition for Teachers?” International Journal of Educational and Life Transitions 1 (1): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijelt.28.

- Christakis, Dimitri A., Frederick J. Zimmerman, and Michelle M. Garrison. 2007. “Effect of Block Play on Language Acquisition and Attention in Toddlers: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial.” Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 161 (10): 967–971. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.161.10.967

- Clark, Alison. 2004. “The Mosaic Approach and Research with Young Children.” In The Reality of Research with Children and Young People, edited by V. Lewis, M. Kellett, C. Robinson, S. Fraser, and S. Ding, 142–157. London: Sage.

- Clark, Alison. 2005. “Listening to and Involving Young Children: A Review of Research and Practice.” Early Child Development and Care 175 (6): 489–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430500131288.

- Clark, Alison. 2017. Listening to Young Children: A Guide to Understanding and Using the Mosaic Approach. Expanded Third ed. London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Clark, Alison. 2022. Slow Knowledge and the Unhurried Child: Time for Slow Pedagogies in Early Childhood Education. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Clark, Alison, and Peter Moss. 2001. Listening to Young Children: The Mosaic Approach. London: National Children’s Bureau.

- Clark, Alison, and Peter Moss. 2005. Spaces to Play: More Listening to Young Children Using the Mosaic Approach. London: National Children’s Bureau.

- Coad, Jane. 2007. “Using Art-Based Techniques in Engaging Children and Young People in Health Care Consultations and/or Research.” Journal of Research in Nursing 12 (5): 487–497. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987107081250

- Cohen, Lynn, and Joanna Uhry. 2007. “Young Children’s Discourse Strategies during Block Play: A Bakhtinian Approach.” Journal of Research in Childhood Education 21 (3): 302–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/0256854070959459.

- Costa, Arthur, and Bena Kallick. 2014. Disposition: Reframing Teaching and Learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

- Cremin, Teresa., Pamela Burnard, and Anna Craft. 2006. “Pedagogy and Possibility Thinking in the Early Years.” Thinking Skills & Creativity 1 (2): 108–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2006.07.001

- Dweck, Carol. S. 1999. Self-Theories: Their Role in Motivation, Personality, and Development. New York: Psychology Press.

- Ferrara, Katrina, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, Nora S. Newcombe, Roberta Michnick Golinkoff, and Wendy Shallcross Lam. 2011. “Block Talk: Spatial Language During Block Play.” Mind, Brain, and Education 5 (3): 143–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-228X.2011.01122.x

- Gillett-Swan, Jenna K., and Jonathon Sargeant. 2018. “Unintentional Power Plays: Interpersonal Contextual Impacts in Child-Centred Participatory Research.” Educational Research 60 (1): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2017.1410068

- Gull, Carla, Jessica Bogunovich, Suzanne Levenson Goldstein, and Tricia Rosengarten. 2019. “Definitions of Loose Parts in Early Childhood Outdoor Classrooms: A Scoping Review.” International Journal of Early Childhood Environmental Education 6 (3): 37–52.

- Hammarsten, Maria, Per Askerlund, Ellen Almers, Helen Avery, and Tobias Samuelsson. 2019. “Developing Ecological Literacy in a Forest Garden: Children’s Perspectives.” Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning 19 (3): 227–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2018.1517371

- Irwin, Lori G., and Joy Johnson. 2005. “Interviewing Young Children: Explicating Our Practices and Dilemmas.” Qualitative Health Research 15 (6): 821–831. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732304273862

- Jago, Russell, and Richard Bailey. 2001. “Ethics and Paediatric Exercise Science: Issues and Making a Submission to a Local Ethics and Research Committee.” Journal of Sports Sciences 19 (7): 527–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/026404101750238980

- Jindal-Snape, D. 2012. “Portraying Children’s Voices Through Creative Approaches to Enhance their Transition Experience and Improve the Transition Practice.” Learning Landscapes 6 (1): 223–240. http://www.learninglandscapes.ca/.

- Jindal-Snape, D., D. Davies, C. Collier, A. Howe, R. Digby, and P. Hay. 2013. “The Impact of Creative Learning Environments on Learners: A Systematic Literature Review.” Improving Schools 16 (1): 21–31. http://doi.org/10.1177/1365480213478461.

- Johnson, Harriet Merrill. 1933. The Art of Block Building. No. 1. New York: The John Day Company.

- Leigh, Jennifer. 2020. “Using Creative Research Methods and Movement to Encourage Reflection in Children.” Journal of Early Childhood Research 18 (2): 130–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X19885992

- Lundy, Laura. 2007. “‘Voice’ Is Not Enough: Conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.” British Educational Research Journal 33 (6): 927–942. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920701657033

- Lundy, Laura., and Lesley McEvoy. 2012. “Children’s Rights and Research Processes: Assisting Children to (In)formed Views.” Childhood (Copenhagen, Denmark) 19 (1): 129–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568211409078

- Nicholson, Simon. 1971. “How Not to Cheat Children, the Theory of Loose Parts.” Landscape architecture 62 (1): 30–34.

- OECD. 2017. Starting Strong V: Transitions from Early Childhood Education and Care to Primary Education. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Park, Boyoung, Jeong-Lim Chae, and Barbara Foulks Boyd. 2008. “Young Children’s Block Play and Mathematical Learning.” Journal of Research in Childhood Education 23 (2): 157–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568540809594652.

- Parker, Lucy. 2020. A Froebelian Approach: Exploring Clay. Available at https://www.froebel.org.uk/uploads/documents/FT-Exploring-Clay-Pamphlet.pdf [accessed 20 November 2023]

- Perkins, David. N., Eileen Jay, and Sharon Tishman. 1993. “Beyond Abilities: A Dispositional Theory of Thinking.” Merrill-Palmer Quarterly: Journal of Developmental Psychology 39 (1): 1–21.

- Pyle, Angela. 2013. “Engaging Young Children in Research through Photo Elicitation.” Early Child Development and Care 183 (11): 1544–1558. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2012.733944.

- Robb, A., D. Jindal-Snape, D. Asi, A. Barrable, E. Ross, H. Austin, and C. Murray. 2023. “Supporting Children’s Wellbeing Through Music Participation During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from Scotland.” Education 3-13: 1–18. http://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2023.2219271.

- Rößler, Daniela C., Heike Pröhl, and Stefan Lötters. 2018. “The Future of Clay Model Studies.” BMC Zoology 3 (1): 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40850-018-0027-4

- Tovey, Helen. 2016. Bringing the Froebel Approach to Your Early Years Practice. London: Routledge.

- Urbina-Garcia, A., D. Jindal-Snape, A. Lindsay, L. Boath, E. F. S. Hannah, A. Barrable, and A. K. Touloumakos. 2022. “Voices of Young Children Aged 3–7 Years in Educational Research: an International Systematic Literature Review.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 30 (1): 8–31. http://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2021.1992466.

- Wall, Kate, Arnott Lorna, and Mallika. Kanyal. 2017. “Look Who’s Talking – Exploring a Proposed Set of Principles for Voice with Young Children.” Paper Presented at EECERA, Bologna, 29 August–1 September 2017.

- Whitebread, David, Penny Coltman, Helen Jameson, and Rachel Lander. 2009. “Play, Cognition and Self-Regulation: What Exactly Are Children Learning When They Learn Through Play?” Educational and Child Psychology 26 (2): 40–52. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsecp.2009.26.2.40