Abstract

Purpose: This paper explores the thresholds that firms apply when classifying discontinued operations in accordance with the requirement in IFRS 5 Non-current Assets Held for Sale and Discontinued Operations (IFRS 5).

Motivation: The IFRS 5 requirement, that only major operations may be classified as discontinued operations, is vague and open to interpretation. Existing literature is largely silent on what firms deem as major, whether diversity exists in practice, and whether the classification decision can be linked to earnings management.

Methodology: The sample includes financial statement data of listed South African firms for the financial years ending 2016 to 2022. Univariate analyses and graphical presentations are used to address the research questions.

Main findings: Diversity exists as to what firms deem as major discontinued operations. A non-negligible portion of firms classify relatively minor operations as discontinued. Evidence shows that firms’ classification decision is related to whether the discontinued operations incurred losses and whether a firm is audited by a Big Four auditor. No evidence of earnings management through meeting or beating performance benchmarks is found.

Practical implications: The paper contributes to a long-standing request to the International Accounting Standards Board to provide guidance on the classification of discontinued operations. The observed thresholds can be used in the decision-making process of practitioners and tertiary educators when assessing whether an operation meets the size requirement of IFRS 5.

Contribution: The paper contributes to the limited literature on the topic and relies on hand-collected data that could not be found on commonly used databases.

1. Introduction

The disaggregation of earnings in financial reports enables investors to make more accurate predictions about a firm’s future earnings (Fairfield et al., Citation1996; Lipe, Citation1986). One area of disaggregation is the separate presentation of discontinued operations in financial statements. International Financial Reporting Standard 5 Non-Current Assets Held for Sale and Discontinued Operations (IFRS 5) (International Accounting Standards Board (IASB), Citation2022a) requires the results of discontinued operations to be presented separately from continuing operations on the income statement. Although such disaggregation can be informative, by improving predictions about the persistence of earnings, evidence exists of potential earnings management through shifting core expenses from continuing operations to discontinued operations (Barua et al., Citation2010; Ji et al., Citation2020). Before managers can shift continuing expenses to discontinued operations, however, they need to classify an operation as discontinued.

The requirement in IFRS 5, as to when an operation can be classified as a discontinued operation, is vague and, open to interpretation. In terms of IFRS 5 a component of business, that is to be disposed of, can be classified as discontinued if that component is a “separate major line of business or geographical area of operations” (emphasis added) (IASB, Citation2022a, para. 32). No guidance is provided as to what constitutes major. This vagueness in the classification requirement of discontinued operations prompts this paper to investigate the quantitative levels at which firms classify operations as discontinued and, following this, to investigate possible reasons why firms classify minor operations as discontinued, contrary to the IFRS 5 requirement.

The absence of guidance of what is deemed as a major operation may, at best, result in the non-comparability of financial statements due to preparers having different interpretations of the measure or, worse, detract from usefulness through the intentional misclassification of recurring expenses as part of discontinued operations. This intentional ‘classification shifting’ between line items in the financial statements is seen as a relatively cheap form of earnings management (McVay, Citation2006, p. 504), which can lead to biasedFootnote1 disclosure by artificially changing the results of continuing operations, although not the bottom-line earnings. Furthermore, the disclosure requirements of IFRS 5 do not stipulate the level of detail required about the income and expenses of discontinued operations. For instance, IFRS 5 (IASB, Citation2022a, para. 33) requires the revenue and expenses of discontinued operations to be disclosed, with no clear stipulation of the level of detail or disaggregation required. Absent the detailed disclosure, even informed users of financial statements may need help to unravel instances when firms shift core expenses to discontinued operations.

It may then come as no surprise when external auditors view the appropriate classification of discontinued operations in terms of the requirements of IFRS 5 as an area of concern. More specifically, misclassifying minor components as discontinued operations increases auditors’ risk when expressing an opinion about whether a firm’s financial statements is a fair presentation. An example of auditors expressing their concern is in the 2021 annual financial statements of MPact Group Limited, where its auditors, Deloitte, raised as a key audit matter their decision on whether Mpact’s discontinued operations did indeed represent a separate major line of business or geographical area of operations and whether the resulting classification of a discontinued operation was valid (Mpact Limited Group, Citation2021, p. 17). Because ‘discontinued operations’ is primarily a presentation and classification issue, classification shifting is intrinsically linked to it in instances of intentional misclassification. Although this paper often refers to classification shifting, the initial, potentially incorrect classification of operations as discontinued is being investigated, not whether firms engage in classification shifting.

The paper makes the following two contributions. Firstly, by shedding light on the quantitative thresholds at which firms classify discontinued operations, the findings can be used as input in the decision-making process of firms, auditors and academics when deciding whether a component to be classified as discontinued is major. Where IFRS accounting standards are unclear, International Accounting Standard 8 (IASB, Citation2022b, para. 12) states that accounting literature and industry practices can be used to provide guidance. Providing evidence of current industry practices can help to establish objective thresholds which, in turn, can improve the quality of financial reporting (Rapaccioli & Schiff, Citation1991, p. 59). In this way, the paper satisfies the International Accounting Standards Board’s (IASB) research objective of providing evidence-based research that may offer insights to IASB staff when assessing the adequacy of existing standards (IASB, Citation2023). To date, a call by the IFRS Interpretation Committee for the IASB to clarify the classification of discontinued operations, specifically about when a component is deemed a major line of business or geographical area of operations (IFRS Interpretation Committee (IFRIC), Citation2016, p. 6) remains unanswered. Secondly, using a South African sample of listed firms, the paper contributes to IFRS 5 literature on the disaggregation of financial statement line items, by providing evidence from a developing economy perspective. Because country specific factors often play a big role in influencing accounting choice (Stadler & Nobes, Citation2014), the findings from existing studies that focus on firms in developed economies may not be generalisable to firms in developing economies. In this regard, Frank (Citation2020, 120) observes a lack of evidence on the initial classification of discontinued operations and calls for more research. In addition, by showing that some Big Four auditors allow relatively minor operations to be classified as discontinued and finding no evidence that the classification decision is linked to indicators of earnings management, the paper adds to the debate of whether the narrow scope definition of discontinued operations is justified, or whether, as raised by Curtis et al. (Citation2014), a broader scope classification of discontinued operations (i.e. not limited to major operations only) will enable users to better predict future continuing earnings.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2, the literature review, commences with the theoretical basis that can help explain management’s decision to classify minor operations as discontinued. Section 2 continues, by putting into context the size-requirement contained in accounting standards when classifying discontinued operations. This is done by discussing how the size-requirement in US GAAP evolved and contrasts the requirement with that in IFRS 5. Section 2 concludes with how the size requirement in IFRS 5 can be interpreted. Section 3 sets out the research questions and related hypotheses. Section 4 discusses the sample, data collection, and research method. Section 5 provides the results and Section 6 concludes.

2. Literature review

2.1. Theoretical basis

Lipe (Citation1986) provides early evidence that decomposing net earnings in its compiling parts contain incremental information to explain variation in share returns beyond that contained in a single net earnings line. Furthermore, more persistent earnings enable investors to better predict future share returns than non-recurring earnings (Bradshaw & Sloan, Citation2002; Collins & Kothari, Citation1989; Kormendi & Lipe, Citation1987). In the context of presenting ‘special items’ (i.e. non-recurring items) in the financial statements to convey to users an understanding of the persistence of earnings, Riedl and Srinivasan (Citation2010) provide evidence that special items presented on the face of the income statement are more persistent than those shown in the notes. In the context of discontinued operations, presenting the results of continuing operations separately from those of discontinued operations communicates to investors and lenders that the results of the discontinued operation will not recur in future since the firm divests from that line of business or geographical area of operations.

In contrast to the information content of discontinued operations, discussed above, agency theory may explain management’s classification decision where incentives exist for management to achieve a particular presentation. On the one hand, the separate presentation of discontinued operations (distinguishable from continuing operations) can convey either good news (e.g., the closure of loss-making operations) or bad news (e.g., forced sales to alleviate liquidity problems). If managers are punished for prior poor investment decisions, they may have incentives to avoid highlighting the discontinuance of an operation through separate presentation. On the other hand, management could use the separate presentation as a way of intentionally misclassifying items between continuing and discontinued operations (Barua et al., Citation2010, p. 1489). Indeed, early evidence show that management uses the classification of special items to smooth core earnings (Ronen and Sadan, Citation1975; Barnea, Ronen and Sadan, Citation1976). Therefore, management may be tempted to shift recurring expenses to a non-recurring line item if they believe that investors place a higher value on recurring earnings (Kaplan et al., Citation2020, p. 294). Mcvay (Citation2006, p. 502) argues that the attractiveness of classification shifting, as a form of earnings management, in contrast to accrual management or real earnings management, is that it can be done at a relatively low cost to management. Whereas both accrual management and real earnings management have real cost implications, e.g., through the reversal of accruals and reducing income-producing activities, respectively, classification shifting does not change the bottom-line earnings and may attract less auditor scrutiny (McVay, Citation2006, p. 502). This could make classification shifting the more attractive alternative for management to achieve a particular presentation.

The classification of discontinued operations may also be used to shift expenses from continuing operations to meet or beat performance benchmarks. Degeorge et al. (Citation1999, p. 30) conclude that some investors often rely on heuristics when evaluating firm performance, giving more weight to gains than losses. Barth et al. (Citation1999) provide evidence of firms being rewarded by higher price-earnings multiples when they exceed a prior year’s earnings. Matsunaga and Park (Citation2001) provide supporting evidence of CEOs being penalised with lower bonuses when missing earnings benchmarks. As a result, managers have incentives to attempt to meet or beat earnings benchmarks used to evaluate firms’ performance. These benchmarks commonly include instances where a firm avoids presenting a loss, avoids presenting a decline in earnings, and avoids a negative earnings surprise (Brown & Caylor, Citation2005; Degeorge et al., Citation1999; Jiang, Citation2008).

In summary, although the separate presentation of discontinued operations contains decision-useful information, managers can use it to improve the outlook of recurring earnings artificially. Such misuse, through classification shifting, requires operations to be classified as discontinued operations in the first place. In this regard, Barua et al. (Citation2010, p. 1491) posit that managers have a greater incentive to shift expenses to discontinued operations than to other non-recurring line items but that it remains “ … an empirical question as to whether they have the opportunity to do so.” Accepting standard setters’ contention that the separate presentation of minor operations, as discontinued, will not provide useful information (e.g. IASB, Citation2022c, para. 69), agency theory is used as main theoretical underpinning to explain why firms would classify minor operations as discontinued. The following section explores accounting requirements in classifying discontinued operations, specifically focusing on the potential for misuse of the classification.

2.2. Accounting requirements in the classification of discontinued operations

The primary focus of the study is on discontinued operations within the context of IFRS 5. Nevertheless, its counterpart in United States Generally Accepted Accounting Practice (US GAAP), Accounting Standards Update (ASU) 2014-08, Reporting Discontinued Operations and Disclosures of Disposals of Components of an Entity (ASU 2014-08) (Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), Citation2014), or more specifically the evolvement to it, provides insight into the size requirement contained in IFRS 5. In addition, this section identifies four potential factors that may influence firms’ decision when classifying operations as discontinued: the loss-making status of discontinued operations, auditor size, avoiding a loss and avoiding earnings decrease from continuing operations.

2.2.1. US GAAP

The US Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) issued ASU 2014-08’s predecessor, the Statement of Financial Accounting Standards 144 (SFAS 144), in 2001 (FASB, Citation2001a). In turn, SFAS 144 expanded the criterion for inclusion as a discontinued operation from its predecessor, APB 30 Reporting the Results of Operations – Reporting the Effects of Disposal of a Segment of a Business, and Extraordinary, Unusual and Infrequently Occurring Events and Transactions (APB 30) (FASB, Citation2001b), by relaxing the requirement that a discontinued operation must be a segment, and thus a major part of an entity, to simply being a component of the entity. SFAS 144, therefore, removed the size requirement for classification purposes. Dickins et al. (Citation2017) observed that, following the adoption of SFAS 144, the number of US firms that disclosed components as discontinued increased sharply and that the increase was primarily driven by firms that disclosed smaller size disposals as discontinued operations.

The increase in the scope of discontinued operations from APB 30 to SFAS 144 prompted researchers to question whether SFAS 144’s broader definition facilitated the presentation of decision-useful information or, instead, enabled firms to misuse the broader classification (which now included small, discontinued operations) to improve results from continuing operations. Consistent with their hypothesis that the broader scope of SFAS 144 provided more opportunity for classification shifting, Barua et al. (Citation2010, p. 1501) find evidence that US firms with loss-making discontinued operations intentionally classify recurring expenses as part of discontinued operations in the SFAS 144 period. Frank (Citation2020, p. 169) finds similar evidence of firms that present financial statements based on IFRS. Kaplan et al. (Citation2020, p. 294) follow up on the findings of Barua et al. (Citation2010) that firms with loss-making discontinued operations engage in classification shifting and argue that acquirers of loss-making operations are unlikely to continue to operate the operation in the same manner and will therefore discount any losses the loss-making operation incurred. Resultantly, Kaplan et al. (Citation2020, p. 294) argue that management has a greater incentive to shift recurring expenses to loss-making discontinuing operations. In contrast, an acquirer of an income-increasing discontinued operation will likely continue to operate the discontinued operation as before. Therefore, shifting recurring expenses to income-increasing discontinued operations will lower its valuation, resulting in real costs for the disposing manager (Kaplan et al., Citation2020, p. 294). Consequently, whether operations are loss-making appears to influence management’s decision to engage in classification shifting. Whether the loss-making status also affects the decision to classify an operation as discontinued is unclear.

In addressing concerns that firms use classification shifting through discontinued operations to meet or beat performance benchmarks, Barua et al. (Citation2010) find weak evidence that firms do so to avoid making a loss and avoid an earnings decline in continuing operations but find more substantial evidence in favour of firms attempting to meet or beat analyst’s forecasts. In a follow-up study, Ji et al. (Citation2020) corroborate the findings of Barua et al. (Citation2010), although they find no evidence that firms use classification shifting through discontinued operations to avoid losses. In contrast to these studies that investigate the misuse of the discontinued operations classification, Curtis et al. (Citation2014) find that the earnings of continuing operations of firms became more persistent after SFAS 144, suggesting a greater decision-usefulness by enabling firms to define minor operations as discontinued operations. However, their findings (Curtis et al., Citation2014, p. 199) are limited to single-segment firms. Therefore, when firms can classify minor operations as discontinued, mixed evidence exists of whether discontinued operations are used to convey decision-useful information or to misclassify items.

In April of 2014, the FASB changed the accounting requirement once again, this time more closely aligned with the size requirement in IFRS 5, when it issued ASU 2014-08. In terms of ASU 2014-08 paragraph 205-20-45-1B (FASB, Citation2014), the disposal of a component can be classified as a discontinued operation “if the disposal represents a strategic shift that has (or will have) a major effect on an entity’s operations and financial results” (own emphasis). Examples of such a strategic shift are provided in paragraph 205-20-45-1C and include “a disposal of a major geographical area, a major line of business, a major equity method investment, or other major parts of an entity” (FASB, Citation2014). This change, from no size requirement to requiring discontinued operations to be major operations, prompted Ji et al. (Citation2020) to investigate whether the more restrictive definition led to less classification shifting than that found in the SFAS 144 period. Consistent with their hypothesis, Ji et al. (Citation2020, p. 1212) find that the more restrictive ASU 2014-08 is associated with less shifting of core expenses from continuing to discontinued operations (than before), but they are unable to show that the decrease is a direct result of the more restrictive size requirement in ASU 2014-08 (Citation2020, p. 1218). However, Ji et al. (Citation2020, p. 1217) make the major/minor distinction based on the median earnings of loss-making discontinued operations. Since ASU 2014-08 already limited firms to large, discontinued operations, their (Ji et al., Citation2020) findings about small, discontinued operations in the more restrictive ASU 2014-08 period appear inconclusive.

In addition to the performance benchmarks, Ji et al. (Citation2020, p. 1220) explore how external auditor size affects their results and find that in the less restrictive SFAS 144 period, firms audited by either Big Four (i.e., Deloitte, EY, KPMG and PwC) or non-Big Four auditors engaged in classification shifting, but that only firms with Big Four auditors showed a decrease in classification shifting in the more restrictive ASU 2014-08 period. This evidence suggests that the Big Four auditors, commonly perceived as having higher audit quality (DeFond & Zhang, Citation2014, p. 299), apply more scrutiny to the classification and presentation of discontinued operations than non-Big Four auditors.

It may be argued that sophisticated users are not likely to be fooled by these artificial earnings management techniques, but Beyer et al. (Citation2021, p. 14) provide evidence to the contrary by finding a significant positive association between income-decreasing discontinued operations and analyst forecast error. By restricting firms from defining discontinued operations as a major component of operations, accounting standards can help ensure higher quality (less opportunistic) disclosure practices. Any lack of guidance in accounting standards as to what constitutes a major line of business increases the risk that firms misuse the discontinued operation classification to shift expenses, resulting in information that is not decision-useful. In this regard, IFRS 5, which is discussed next, provides much leeway.

2.2.2. IFRS 5

IFRS 5 (IASB, Citation2022a, para. 32) defines a discontinued operation as a component of an entity that either has been disposed of or is classified as held for sale and:

| a) | Represents a separate major line of business or geographical area of operations, | ||||

| b) | Is part of a single coordinated plan to dispose of a separate major line of business or geographical area of operations … (emphasis added) | ||||

From the definition in IFRS 5, it can be concluded that a component that does not form a major line of business or geographical area of operations does not meet the definition of a discontinued operation and may detract from the decision-usefulness of financial statements, if presented. Consequently, the results of minor operations in the disposal process should not be separately disclosed as discontinued but as part of continuing operations. In determining whether an operation is major, one could argue that the size requirement relates to materiality and, in line with the Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting (IASB, Citation2022d, Chapter 2), that users find material information useful. Neither US GAAP nor IFRS 5 provides quantitative guidance to decide whether an operation is major. In contrast to the lack of guidance on what can be conceived as a major, the concept of materiality has more guidance available and is discussed next.

2.3. Major versus material

In the context of discontinued operations, research on what constitutes a major line of business and geographical area of operations is limited. US-based studies primarily use the profit or loss of the discontinued operations as indicators of size. Curtis et al. (2014, p. 195) distinguish between minor and major discontinued operations, deeming those with a magnitude less than 1% of lagged assets as minor. Ji et al. (Citation2020, p. 1227) view minor, discontinued operations as those with net income, scaled by total revenue, below the median level of observations. The choice of profit or loss from discontinued operations as size indicator in the US-based studies may be attributable to a lack of financial statement disclosure. Before ASU 2014-08 became effective, US GAAP accounting standards did not require revenue and expenses of discontinued operations to be disclosed (Ji et al., Citation2020, p. 1205). In contrast, IFRS 5 has, since it was initially issued in 2004, required that the revenue of the discontinued operation be separately disclosed (IASB, Citation2022a, para. 33).Footnote2

Contrary to the US-based studies, the IFRS-based study of Frank (Citation2020) uses revenue and total assets of the discontinued operation as primary size indicators when investigating how listed firms in the UK, Switzerland and Germany classify components as discontinued in terms of IFRS. In assessing the size of an operation, specifically when operations are loss-making, as may often be the case when operations are discontinued, revenue and total assets may be more appropriate indicators of the size of a discontinued operation than profit or loss (Frank, Citation2020, p. 113). In the absence of guidance of what is deemed as major, and because more guidance exists of when amounts can be considered material, Frank (Citation2020) uses materiality benchmarks commonly used by accounting firms to categorise discontinued operations as major or minor. Frank (Citation2020, p. 114) argues that a component is major if its revenue is 5% or more of continuing operation’s revenue,Footnote3 contestable if it is between 2% and 5% and suspect if below 2%. In contrast to Frank’s (Citation2020) lower limit of 2%, a survey of accounting firms by the UK Financial Reporting Council (FRC) (Citation2017, p. 15) indicates that overall materiality is set to between 0.5% and 2% of revenue. These levels align with South African guidance of 0.5% to 1% of revenue (Marx et al., Citation2019, Chapter 8). In addition, when considering the materiality of a component of a business, 50% of overall materiality can be regarded as material (FRC, Citation2017, p. 17).Footnote4 When a firm then presents a discontinued operation with revenue that are less than 0.25% of revenue from continuing operations, it becomes questionable whether the size requirement of major has been met, and furthermore, what purpose management would have to classify a minor operation as discontinued, when doing so breaches the requirements in the accounting standard.

3. Research questions and related hypotheses

The literature review highlighted the risk that management may classify minor operations as discontinued, not to provide decision-useful information but to use the separate presentation to shift continuing expenses to the discontinued operation section on the income statement. Two research questions are investigated. The primary research question, Research question 1 (RQ1), seeks to answer whether firms apply different quantitative materiality thresholds when classifying discontinued operations.Footnote5 Given the lack of guidance in IFRS 5, diversity is expected. Thus, the first research hypothesis, stated in alternative form, is:

H1: South African firms apply different levels of quantitative materiality thresholds when classifying operations as discontinued.

Following on the results from RQ1, Research question 2 (RQ2) explores four possible reasons why diversity in the applied quantitative thresholds may exist. The following secondary questions are explored: Is there a relation between the materiality thresholds identified in RQ1 and:Footnote6

| 2.1 | the loss-making status of discontinued operations? | ||||

| 2.2 | whether a firm is audited by a Big Four auditor? | ||||

| 2.3 | whether a firm avoids a loss on continuing operations? | ||||

| 2.4 | whether a firm avoids a decrease in earnings from continuing operations? | ||||

RQ2.1 explores the relation between the results of the discontinued operation and the threshold levels used in classifying discontinued operations. Barua et al. (Citation2010, p. 1501) provide evidence that firms with loss-making discontinued operations engage in classification shifting. In contrast, Ji et al. (Citation2020, p. 1218) find that firms engage in classification shifting regardless of the results of the discontinued operations. It is therefore unclear what impact the loss-making status of discontinued operations has on firms’ classification decision. This leads to the following research hypothesis, stated in the null form:

H2.1: The quantitative materiality thresholds that South African firms apply, when classifying operations as discontinued, are not associated with the loss-making status of their discontinued operations.

RQ2.2 explores the relationship between auditor size and the materiality thresholds used. Following Ji et al. (Citation2020, p. 1227), auditor size is differentiated between whether a firm is audited by one of the Big Four auditing firms. Because larger auditors are often linked to higher audit quality (DeFond & Zhang, Citation2014), the financial statements audited by the Big Four auditors are likely to be subject to more scrutiny, resulting in only major components being classified as discontinued (Ji et al., Citation2020, p. 1203). This leads to the following research hypothesis, stated in the alternative form:

H2.2: The quantitative materiality thresholds that South African firms apply, when classifying operations as discontinued, are associated with whether a firm has a Big Four auditor.

RQ2.3 explores the first of two characteristics linked with earnings management by exploring the relation between whether a firm avoids making a loss from continuing operations and the materiality thresholds used.Footnote7 RQ2.4 explores another characteristic linked to earnings management by examining the relation between whether a firm avoids earnings decrease in continuing operations compared to the prior year's earnings. In line with Barua et al. (Citation2010) and Ji et al. (Citation2020), whether a firm avoids making a loss and avoids earnings decline in continuing operations are two performance benchmarks often linked to earnings management. However, neither study found convincing evidence of any association between firms’ classification choice and preventing a loss or earnings decrease. Thus, the final two research hypotheses, both in the null form, are:

H2.3: The quantitative materiality thresholds that South African firms apply, when classifying operations as discontinued, are not associated with whether a firm avoids a loss on continuing operations.

H2.4: The quantitative materiality thresholds that South African firms apply, when classifying operations as discontinued, are not associated with whether a firm avoids a decrease in earnings from continuing operations.

4. Sample, data collection and research method

4.1 Sample

The sample consists of all JSE-listed firms on the IRESS Expert database that disclosed a discontinued operation in their annual financial statements for financial years ending in 2016 to 2022.Footnote8 The sample period is selected to provide a sufficient sample size for analysis. depicts the sample selection process.

Table 1. Sample selection process.

After excluding 1 839 firm-years with no results for discontinued operations on the income statement, 324 firm-years with discontinued operations remain. Because this study explores the thresholds that firms use when initially classifying operations as discontinued, 148 firm-years that classified an operation as discontinued in a prior year are excluded, with some remnant income and expenses in the current year. From the remaining 176 firm-years, two remaining firm-years with firms in the financial industry are removed. For firms in the financial services industry, the distinction between investing and operating activities and the resultant effect on the classification of income statement line items (e.g., turnover) are often very different from other industries. Lastly, 35 firm-years that presented financial statements in a currency other than South African Rand are excluded because converting income statement amounts to South African Rand introduces noise in calculating the quantitative threshold levels used to classify discontinued operations. The final sample consists of 139 firm-years.

4.2. Data collection

Published financial statement data are obtained from the IRESS Expert database and data on firms’ external auditors from the Bloomberg database. For every firm-year, the data includes information on the revenue from continuing operations, a firm’s total assets, profit or loss from discontinued operations, and earnings per share from continuing operations. The revenue and total assets of discontinued operations, and restated prior year data for earnings per share from continuing operations are unavailable from the databases and are hand collected from the published financial statements, as available through the IRESS database. On some instances a firm classified and disposed of discontinued operations in the same financial year. In such cases, the total assets of the discontinued operations are not held for sale any longer and the carrying amount of the total assets at date of sale is used instead.

4.3. Research method

To test H1, in which it is hypothesised that South African firms apply different levels of quantitative materiality thresholds when classifying operations as discontinued, discontinued operations are categorised according to thresholds derived from commonly accepted materiality levels. This paper follows Frank (Citation2020, p. 113) and uses revenue and total assets as indicators of the size of the operations that are classified as discontinued. In line with Frank (Citation2020, p. 113), the materiality levels used by accounting firms, read together with South African guidance (Marx et al., Citation2019, Chapter 8), establish thresholds at which discontinued operations can be considered major. Bar plots will illustrate the frequencies within the respective size categories. In testing whether a statistically significant difference exists between the size categories, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) will be used to compare the revenue and asset ratios upon which the materiality threshold categories are based. The revenue ratio is the ratio of revenue from discontinued operations to revenue from continuing operations. The asset ratio is the ratio of the total assets of the discontinued operation to firm total assets. The use of a one-way ANOVA is deemed appropriate as it is used when testing whether a difference in means of continuous variables (the revenue and asset ratios) exists between categories (the materiality threshold categories) (Keller & Warrack, Citation2003, p. 472).

presents the materiality threshold categories used to classify the discontinued operations according to size.

Table 2. Materiality threshold categories used to categorise the size of discontinued operations.

Firm-years in the ‘clearly material’ category have discontinued operations that exceed the upper thresholds of accepted materiality based on either revenue or total assets. Firm-years in the ‘normal materiality’ category fall within the documented range of overall materiality (FRC, Citation2017; Marx et al., Citation2019). Because these two categories meet or exceed the accepted levels of overall materiality, discontinued operations that fall in the top two categories are deemed major. Where discontinued operations fall in the ‘component materiality’ category, deciding whether a discontinued operation is major becomes less apparent and more subjective. Discontinued operations that fall in the ‘sub-minimum threshold’ category fall below the minimum component materiality level, which raises the concern of whether those discontinued operations meet the size requirement of major as required by IFRS 5. Consequently, if the discontinued operations in the ‘sub-minimum threshold’ are not deemed as major, the question of possible misuse of the discontinued operation classification arises.

To test H2.1 to H2.4, which examine the association between the quantitative materiality thresholds applied by South African firms in classifying discontinued operations and, respectively, the loss-making status of discontinued operations, whether a firm is audited by a Big Four auditor, whether a firm avoided a loss from continuing operations and whether a firm avoided a decrease in earnings from continuing operations, the chi-squared test of independence is used. The chi-squared test of independence is used to determine whether there is sufficient evidence to infer that two nominal variables are related or whether there are differences between two or more populations of nominal variables (Keller & Warrack, Citation2003, p. 538). Because all the variables (see below), including the materiality thresholds, are categorical, the chi-squared test of independence is appropriate to address H2.1 to H2.4.

The following classifications of categorical variables are used in H2.1 to H2.4:

H2.1: ‘Loss-making discontinued operations’ equals one for firm-years with discontinued operations that incur losses, and zero otherwise.

H2.2: ‘Big Four auditor’ equals one for firm-years in which the firm is audited by a Big Four auditor,Footnote9 and zero otherwise.

H2.3: Consistent with Barua et al. (Citation2010) and Ji et al. (Citation2020), ‘Avoid loss’ equals one for firm-years in which the basic earnings per share from continuing operations for the current year is positive, and zero otherwise.

H2.4: Also consistent with Barua et al. (Citation2010) and Ji et al. (Citation2020) ‘Avoid earnings decrease’ equals one for firm-years in which the change in basic earnings per share from continuing operations is positive compared to the prior year, and zero otherwise.

Where the expected frequency of observations on any variable is five or less, the chi-squared test of independence may, although not necessarily, lead to inadequate approximations (Agresti, Citation1996, p. 194). In such cases, Fisher’s exact test, which overcomes the shortcomings of the low frequencies (Agresti, Citation1996, p. 194), is used to test the validity of the results of the chi-squared test of independence.

5. Results

5.1. H1: South African firms apply different levels of quantitative materiality thresholds when classifying operations as discontinued

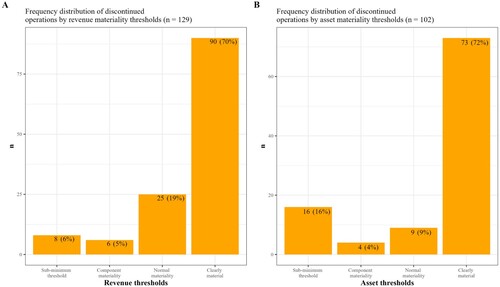

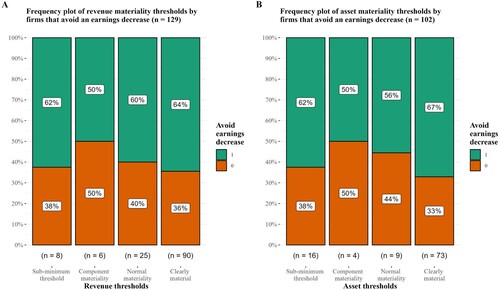

shows the frequency distribution of discontinued operations, categorised according to materiality thresholds. A shows the distribution when materiality is based on revenue from discontinued operations to continuing revenues (referred to hereafter as the revenue threshold or revenue ratio). B shows the frequency distribution when thresholds are determined based on the total assets of discontinued operations to total firm assets (referred to hereafter as the asset threshold or asset ratio).

Observations with missing data on revenue and assets were excluded from the original sample of 139 firm-years, resulting in a reduced sample of 129 for revenue thresholds and 102 for asset thresholds. shows that applying either revenue or asset thresholds results in a similar outcome on the ‘clearly material’ category but that the distribution across the bottom three categories appears different. Focusing firstly on revenue-based materiality, A shows that the majority (70% of 129 firm-years) fall in the ‘clearly material’ category. This leaves 30% in the below 2% threshold. In contrast, Frank (Citation2020, p. 124) finds 21% of his sample of firms from the UK, Switzerland, and Germany, classified operations as discontinued when revenues were below 2%. It seems that South African firms tend to classify discontinued operations at lower materiality levels, when compared to firms in developed economies. The next category is the ‘normal materiality’ category with 19% of the sample of 129. Of the remaining firm-years, 5% (six firm years) had revenues that met component materiality thresholds (between 0.25% and 0.5% of continuing revenues) and 6% (eight firm-years) in the ‘sub-minimum threshold’ had revenues below 0.25% of continuing revenues. Turning now to asset thresholds, B shows that, like the distribution in A, most observations fall in the upper two categories (‘normal materiality’ and ‘clearly material’). The higher concentration of firm-years in the ‘sub-minimum category’ with 16% of firm-years is slightly different, thus leaving 4% in the ‘component materiality’ category. From a revenue or asset perspective, a non-negligible portion of firms classified operations below component materiality as discontinued. Consequently, the firms in the sub-minimum threshold category deemed an operation they classified as discontinued as a ‘separate major line of business or geographical area of operations’. Whether such classification meets the ‘size’ requirement of IFRS 5 is debatable in the context of quantitative materiality thresholds.

provides descriptive statistics on the total sample, and and provide a breakdown of discontinued operations categorised according to revenue and asset thresholds, respectively. The p-values relate to one-way ANOVA on continuous variables and Pearson chi-squared test of independence on categorical variables. Fisher’s exact test results are also reported where the expected frequency of categorical variables falls below five. Initial descriptive statistics identified various extreme outliers on continuous variables. Consequently, all continuous variables are winsorised at the first and 99th percentiles to mitigate the effect of those outliers.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics on the total sample.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics based on revenue thresholds (n = 129).

Table 5. Descriptive statistics based on total assets thresholds (n = 102).

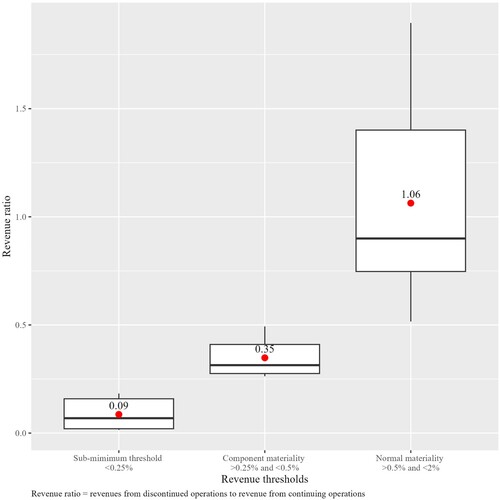

shows that the mean revenue threshold evident from the classification of discontinued operations is 30.22% (median = 6.08%), with a statistically significant difference between the categories (F(3, 125) = 2.93, p = .036).Footnote10 The relatively high mean revenue ratio is primarily the result of influential observations in the ‘clearly material’ category, where a mean of 42.98% and a median of 12.86% apply. In deciding whether an operation is major, thus meeting the IFRS 5 classification requirement, the large operations in the ‘clearly material’ category pose no difficulty as they are material to the firm. The revenue thresholds of the bottom three categories are much lower and more closely aligned. provides box plots to compare the mean (depicted by a red dot and value label) and median size of discontinued operations in the bottom three categories, expressed in terms of the revenue ratio.

Figure 2. Box plots of the revenue ratios of the bottom three revenue materiality threshold categories (n=39).

shows that the effect of outliers is far less prominent in the bottom three categories, as the mean and median revenue thresholds are closely aligned per category. Firms in the category ‘normal materiality’ classified as discontinued, those operations with a mean revenue threshold of 1.06% of continuing revenues (median 0.90%). Firms in the ‘component materiality’ category classified as discontinued operations, those with revenues making up 0.35% of continuing revenues (median 0.31%). Although these firm-years meet the component materiality threshold, the lower bounds introduce more subjectivity in deciding whether an operation is major, which raises the risk of incorrectly classifying an operation as discontinued, contrary to the requirements of IFRS 5. Lastly, shows that firms in the ‘sub-minimum’ category deemed operations with revenues of only 0.09% (median = 0.07%) of continuing revenues as major. It is questionable whether operations with revenues in the sub-minimum category meet the IFRS 5 requirement of a ‘major line of business or geographical area of operations’, as these operations fall well below the lower range of component materiality of 0.25% of continuing revenues.

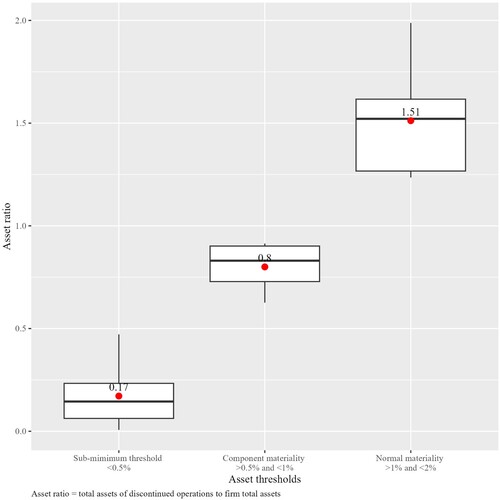

Turning to the asset thresholds, shows that the mean total assets of discontinued operations in the entire sample are 14.29% of firm total assets, with a median of 4.66% and a statistically significant difference between the categories (F(3, 98) = 4.79, p = .004).Footnote11 As with the revenue thresholds, the high asset thresholds are mainly the result of the increased mean values in the ‘clearly material’ category, with mean total assets of discontinued operations to firm total assets being 19.69% (median 9.22%). As before, the ‘clearly material’ category poses no challenge to the discontinued operation classification of IFRS 5, and the focus is placed on the bottom three categories. provides box plots to compare the mean (depicted by a red dot and value label) and median size of discontinued operations in the bottom three categories, expressed in terms of the asset ratio.

Figure 3. Box plots of the total asset ratios of the bottom three asset materiality threshold categories (n=29).

illustrates that the bottom three categories’ mean and median asset thresholds are closely aligned. In the ‘normal materiality’ category (between 1% and 2% of firm total assets), firms classified operations as discontinued when the mean total assets were 1.51% of firm total assets (median 1.52%) and in the component materiality threshold (between 0.5% and 1% of firm total assets) a mean of 0.80% (median 0.83%). As with the revenue thresholds, the asset ratio of 0.17% (median = 0.14%) in the ‘sub-minimum threshold’ category is well below the bottom level of component materiality when total assets are used as a size indicator, namely 0.5% of firm total assets.

In summary, where discontinued operations fall in the categories ‘normal materiality’ or ‘clearly material’, firms have little discretion in deciding whether a component is major. It is, however, at the lower thresholds (component materiality and below) where more discretion can be applied and, therefore, where the risk of misclassification between the continuing and discontinuing categories is higher. When considering the size of discontinued operations from either a revenue or asset perspective, the collective results from and indicate that some firms deem operations, which are arguably very small in terms of the firm’s total operations, as meeting the IFRS 5 size requirement of being a major part of the operations.

This section provided evidence in favour of H1, that firms use different levels of materiality thresholds when classifying discontinued operations. The evidence shows that firms classify operations as discontinued even when those operations fall well below minimum component materiality thresholds.

5.2. Results: H2.1 to H2.4

5.2.1. H2.1: The quantitative materiality thresholds that South African firms apply, when classifying operations as discontinued, are not associated with the loss-making status of their discontinued operations

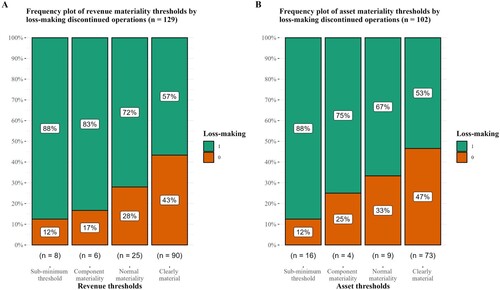

illustrates the results of and , where the revenue and asset thresholds, respectively, are compared in the context of the loss-making status of discontinued operations.

Using revenue as a size indicator, and A shows that almost all (seven of the eight) firms that applied a sub-minimum threshold based on revenue incurred losses in their discontinued operations. Although A shows the frequency of loss-making firms increase towards the smaller materiality categories, , which reports the results of the chi-squared test of independence, shows no statistically significant difference between the categories (Χ2(3, N = 129) = 5.53, p = .14). Fisher’s exact test confirms the results (p = .17). At first glance, firms with loss-making discontinued operations do not appear to be more likely to use sub-minimum revenue thresholds. However, the higher concentration of loss-making discontinued operations seems present in all three bottom threshold categories, i.e., where discontinued operations’ revenue falls below 2% of continuing revenues. In contrast, in the ‘clearly material’ category, the frequency of firms with loss-making discontinued operations is much closer to those that made profits (57% and 43%, respectively). Accepting, as done by Frank (Citation2020, p. 114), that discontinued operations with revenues below 2% of continuing operations are minor and collapsing the bottom three categories into one, untabled results show a statically significant difference between the below 2% and above 2% categories, based on loss-making operations. These results do not appear to be influenced by the size of firms nor by the actual results of discontinued operations, e.g., the extent of losses ( shows no statistically significant difference between the categories on firm total revenue (F(3, 125) = 0.56, p = .64), firm total assets (F(3, 125) = 0.272, p = .85) and profit or loss from discontinued operations (F(3, 125) = 0.188, p = .90)).

When comparing the frequency of loss-making discontinued operations between the asset threshold categories, and B complement the results of the revenue thresholds. indicates that the loss-making status and the size of discontinued operations (when expressed in terms of total assets) are related at 10% level of significance (Χ2(3, N = 102) = 6.92, p = .075). Fisher’s exact test validates the chi-squared test results (p = .059). further shows that loss-making discontinued operations are more prevalent in the ‘sub-minimum’ category (88%) when compared to the expected concentration of loss-making discontinued operations in the sample (61%).

Considering the evidence, H2.1 is rejected where firms use asset thresholds to classify discontinued operations but cannot be rejected where firms use revenue thresholds as basis for the classification. The combined results from and and suggest that firms ignore the size requirement in IFRS 5 by intentionally classifying minor operations, that are loss-making, as discontinued. Given the small size of the operations, which is evident in the sub-minimum categories, it becomes questionable whether the classification as discontinued, is done to provide users with a positive signal that management is committed to dispose of a loss-making venture or whether it is done as a precursor to classification shifting of recurring expenses.

5.2.2. H2.2: The quantitative materiality thresholds that South African firms apply, when classifying operations as discontinued, are associated with whether a firm has a Big Four auditor

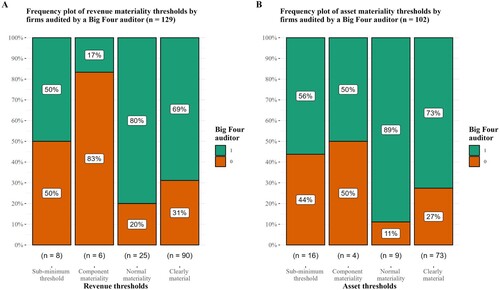

illustrates the results, reported by and , on the difference between the materiality thresholds and whether a firm is audited by a Big Four auditor.

Based on revenue thresholds first, A shows a clear difference in the distribution of auditor size across the revenue threshold categories (statistically significant as reported by ; Χ2(3, N = 129) = 10.03, p = .018). Similarly, results from Fisher’s exact test show a statistically significant difference (p = .019). In the ‘sub-minimum’ category, half of the firms are audited by Big Four auditors. By itself, this is interesting because it suggests that some Big Four auditors are content to sign off on financial statements that classify relatively minor operations, as discontinued. It could be argued that those auditors feel, that despite the operation being minor, the resultant disaggregation of the earnings from that of continuing operations is useful to the financial statement users. In the ‘component materiality’ category, only 17% of firms were audited by a Big Four auditor, still less than the expected sample concentration of 67%. In contrast, firms that classified discontinued operations with revenues in the upper two categories show a far higher concentration of Big Four auditors: 80% in the ‘normal materiality’ category and 69% in the ‘clearly material’ category. Collectively, the higher proportion of Big Four auditors seen in the upper two revenue materiality categories, compared to the ‘sub-minimum threshold’ and ‘component materiality’ categories, suggests that Big Four auditors are more conservative than smaller-sized auditors by not accepting the classification of a minor operation as meeting the size requirement of IFRS 5. The result is not purely mechanical. Although larger firms are often audited by Big Four auditors, indicates that firm size (expressed in terms of firm total revenue) does not statistically differ between the materiality categories (F(3, 125) = 0.56, p = .642). Therefore, the Big Four auditors are not automatically concentrated in the upper categories of the revenue materiality thresholds.

In comparison with the results based on revenue thresholds, if firms used total assets of the discontinued operations to measure its size, B and show the frequency of the Big Four auditors remains high in the top two size categories (89% in the ‘normal materiality’ category and 73% in the ‘clearly material’ category), but that the bottom two asset materiality categories increase, closer to the overall concentration of 67% (as depicted in ). Based on asset thresholds, indicates no statistically significant association with auditor size (Χ2(3, N = 102) = 4.00, p = .26)). Fisher’s exact test confirms the results (p = .25). Because auditors need to be satisfied that a firm’s financial statements meet the requirements of IFRS 5, the insignificant result on asset thresholds may instead suggest that firms focus on revenue thresholds when determining the size of discontinued operations.

In summary, when it comes to firms that apply revenue materiality thresholds when classifying discontinued operations, the evidence is consistent with H2.2, that a firm’s classification decision may be related to whether the firm is audited by a Big Four auditor.

5.2.3. H2.3: The quantitative materiality thresholds that South African firms apply, when classifying operations as discontinued, are not associated with whether a firm avoids a loss on continuing operations

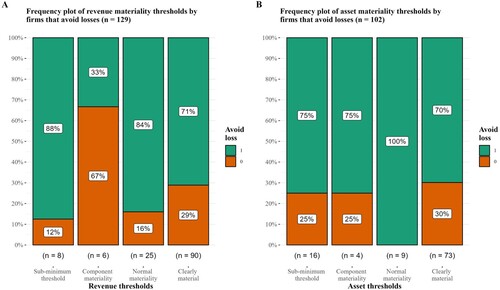

illustrates the results of and to show the frequency of firms that reported positive earnings per share from continuing operations across the materiality threshold categories of discontinued operations.

reports a statistically significant association between the revenue materiality categories and instances where firms avoid losses (Χ2(3, N = 129) = 7.32, p = .062). Fisher’s exact test shows a p-value of 0.076. A shows that the frequency of firms in the ‘sub-minimum’ category is 88%, much higher than 73% of all firms that avoid losses, as seen in . Similar results are found in the ‘normal materiality’ category with a frequency of 84% of firms that avoid losses. In contrast, in the ‘component materiality’ category, the proportion of firms that avoid losses is much less at 33%. Therefore, it appears that the ‘component materiality’ category may be driving the difference between the categories and that loss avoidance does not unduly influence firms to classify minor operations as discontinued. If the bottom three materiality categories are again collapsed into one, the chi-squared test shows no significant difference with the ‘clearly material’ category.

Turning to asset thresholds, reports that no statistically significant association between the asset materiality categories and loss avoidance could be found (Χ2(3, N = 102) = 3.77, p = 0.29). The result is confirmed by Fisher’s exact test (p = .26). These results give some credibility to the prior suggestion that the results of the revenue thresholds may be unduly driven by the differing proportion in the ‘component materiality’ category. In addressing H2.3, the results indicate that the materiality thresholds that firms use when classifying discontinued operations are independent of whether a firm avoids a loss on continuing operations. If loss avoidance is an incentive to intentionally present minor operations as discontinued, to then be able to apply earnings management through classification shifting, the results do not support it. Such conjecture aligns with Ji et al. (Citation2020, p. 1214), who find no evidence that firms shift expenses to discontinued operations to avoid losses. Thus, H2.3 cannot be rejected.

5.2.4. H2.4: The quantitative materiality thresholds that South African firms apply, when classifying operations as discontinued, are not associated with whether a firm avoids a decrease in earnings from continuing operations

illustrates the results of and to show the frequency of firms that reported an increase in earnings per share from continuing operations compared to a prior year across the materiality threshold categories of discontinued operations.

A and B show similar frequencies across the materiality categories, which is consistent with H2.4 that no association exist between the materiality thresholds used in classifying discontinued operations and whether firms avoid an earnings decrease. and confirm this, as no statistically significant difference between either the revenue or asset size categories, in respect of avoiding an earnings decrease, is evident (: (Χ2(3) = .61; p = 0.89); : (Χ2(3) = 0.93; p = .82). Inferences remain unaltered after performing Fisher’s exact test. Therefore, no evidence is found to suggest that firms intentionally classify minor operations as discontinued to prevent a decrease in earnings from continuing operations.

6. Summary and conclusion

This paper set out to investigate the quantitative levels at which listed South African firms classify operations as discontinued and, following this, to investigate possible reasons why some firms classify minor operations as discontinued, contrary to the IFRS 5 requirement. The sample period includes financial years ending 2016 to 2022.

The paper provides evidence of the quantitative materiality thresholds at which firms classify discontinued operations. It finds that a non-negligible portion of the sample firms classify operations, that may be seen as minor, and contrary to the IFRS 5 requirement, as discontinued operations. These findings may be of value to the IASB, because the IASB, before issuing guidance or revising standards, requires evidence of the nature of divergence in accounting practise and of how widespread such divergence is.

Attempting to understand why firms would classify relatively minor operations as discontinued, the paper finds evidence that firms with loss-making discontinued operations may be more likely to classify minor operations as discontinued. Prior studies have shown that the loss-making status of discontinued operations could influence a firm’s decision to engage in classification shifting. The possible relation between the size of discontinued operations and the loss-making status of discontinued operations, may indicate a risk of classification shifting. It is left to future research to investigate whether South African firms with loss-making discontinued operations engage in classification shifting.

The paper also finds the size of discontinued operations and whether a firm is audited by a Big Four auditor to be related. This finding, which is consistent with prior studies that deem auditor size as proxy for audit quality, suggest that firms audited by a Big Four auditor are more likely to apply the requirements in IFRS more strictly and, therefore, that firms with Big Four auditors are less likely to classify minor operations as discontinued. By showing that different auditors interpret the size requirement of IFRS 5 differently, the paper emphasises the need for the IASB to provide guidance in this respect. Although less likely to classify minor operations as discontinued, an interesting finding is that some Big Four auditors allow relatively minor operations to be classified as discontinued, which suggests they deem the information useful in estimating future continuing earnings. Such conjecture is supported by Curtis et al. (Citation2014) who find evidence that a broader scope in the classification of discontinued operations (i.e. not limited to major operations) allows for a better prediction of future continuing income. This raises the issue of whether the IASB should, instead of providing guidance of when operations are deemed as major, remove the size requirement in IFRS 5 to enable firms to provide more decision-useful information. To provide the IASB with support for such a suggestion reiterates the need for further research of whether firms intentionally classify minor operations as discontinued to then apply classification shifting or whether they do so to provide more decision-useful information.

Lastly, the paper finds no evidence that firms intentionally classify minor operations as discontinued, if doing so enables a firm to meet or beat strategic benchmarks, specifically the avoidance of losses and avoidance of a decrease in prior year earnings. This finding aligns with that of existing literature that finds less evidence of classification shifting to meet or beat earnings benchmarks when accounting standards are more restrictive (Ji et al., Citation2020, p. 1214). Whether the size requirement of major, as contained in IFRS 5, helps prevent earnings management through benchmark beating, even if indirectly through more auditor scrutiny, is open to future research.

Certain limitations should be acknowledged. Although the study covers a period of seven years, the use of a South African sample of firms with discontinued operations restricts the number of data points that can be analysed, which could influence the power of the statistical tests. In addition, due to sample size restrictions the paper relies mainly on univariate analyses instead of logistical regressions. The latter may have helped to better understand the strength of association and partial effects between the variables. A key indication of earnings management that is used in prior literature is to determine whether firms’ earnings meet or beat analysts’ forecasts. However, a lack of available data prevented the use of this indicator in the present study. Therefore, the findings from the effect of earnings management may be sensitive to the exclusion of this variable. As stated earlier, the study measures the size of discontinued operations in relation to quantitative materiality levels. In the absence of clear guidance, what IFRS 5 deems as major may also be interpreted from a qualitative materiality perspective, thus influencing the results. Lastly, because the study uses a South African sample, extrapolation should be done with circumspection.

In conclusion, the evidence suggests that firms interpret the size requirement in IFRS 5, that only major lines of business or geographical area of operations can be classified as discontinued operations, very broadly to include relatively small operations. The decision does not appear to be driven by opportunistic reasons.

Ethical clearance

Project number: ACC-2023-27181 (Research Ethics Committee: Social, Behavioural and Education Research (REC: SBE) Stellenbosch University, South Africa).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 The word ‘biased’ is used in the context of the Conceptual Framework section 2, paragraph 15 (IASB, Citation2022d), which relates to a non-neutral depiction of information in the financial statements to influence users’ decisions.

2 The predecessor to IFRS 5, International Accounting Standard IAS 35 Discontinuing Operations, issued in 1998 included the same disclosure requirement to disclose revenue (International Accounting Standards Council, Citation1998).

3 Using a materiality level expressed in terms of continuing operations (and not all operations) is in line with auditing standard 320 par. A14 to adjust materiality when a major part of the business is disposed of.

4 From the survey (FRC Citation2017), component materiality ranged between 50% and 90% of overall materiality, but for purposes of this paper a lower bound is used. Expressed as overall materiality, a component is material if revenue is 0.25% of continuing revenues.

5 Although a firm’s decision-making process is not observable, it is posited that materiality thresholds will necessarily play a role in deciding whether an operation formed a major part of operations.

6 Ibid.

7 A third benchmark, whether earnings meet or beat analyst forecasts, is not explored due to a lack of data in the South African sample. This limitation, which could potentially be overcome by including only large firms with sufficient analyst following, is left to future research.

8 All JSE-listed firms for which financial statement data was available on the IRESS Expert database at the end of May 2023 were selected.

9 The Big Four auditors are Deloitte, EY, KPMG and PwC.

10 The nonparametric counterpart of the one-way ANOVA, the Kruskal-Wallis test, was performed to address potential violations of the ANOVA’s underlying assumptions of normality and equal variances. Untabled results indicate that the difference in means remains significant (p < 0.001).

11 Ibid.

References

- Agresti, A. (1996). An introduction to categorical data analysis. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Barnea, A., Ronen, J., & Sadan, S. (1976). Classificatory smoothing of income with extraordinary items. The Accounting Review, 51(1), 110–122.

- Barth, M. E., Elliott, J. A., & Finn, M. W. (1999). Market rewards associated with patterns of increasing earnings. Journal of Accounting Research, 37(2), 387–413. https://doi.org/10.2307/2491414

- Barua, A., Lin, S., & Sbaraglia, A. M. (2010). Earnings management using discontinued operations. The Accounting Review, 85(5), 1485–1509. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2010.85.5.1485

- Beyer, B., Guragai, B., & Rapley, E. T. (2021). Discontinued operations and analyst forecast accuracy. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 57(2), 595–627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-021-00956-7

- Bradshaw, M. T., & Sloan, R. G. (2002). GAAP versus The Street: An empirical assessment of two alternative definitions of earnings. Journal of Accounting Research, 40(1), 41–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.00038

- Brown, L. D., & Caylor, M. L. (2005). A temporal analysis of quarterly earnings thresholds: Propensities and valuation consequences. The Accounting Review, 80(2), 423–440. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2005.80.2.423

- Collins, D. W., & Kothari, S. P. (1989). An analysis of intertemporal and cross-sectional determinants of earnings response coefficients*. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 11, 143–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-4101(89)90004-9

- Curtis, A., McVay, S., & Wolfe, M. (2014). An analysis of the implications of discontinued operations for continuing income. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 33(2), 190–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2014.01.002

- DeFond, M., & Zhang, J. (2014). A review of archival auditing research. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 58(2–3), 275–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2014.09.002

- Degeorge, F., Patel, J., & Zeckhauser, R. (1999). Earnings management to exceed thresholds. The Journal of Business, 72(1), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1086/209601

- Dickins, D., O’Reilly, D., McCarthy, M., & Schneider, D. (2017, February). Reporting of Discontinued Operations. Past, Present, and Future. The CPA Journal. [Online]. https://www.cpajournal.com/2017/02/15/reporting-of-discontinued-operations-past-present-and-future/

- Fairfield, P. M., Sweeney, R. J., & Yohn, T. L. (1996). Accounting classification and the predictive content of earnings. The Accounting Review, 71(3), 337–355. https://www.jstor.org/stable/248292

- Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). (2001a). Statement No. 144 Accounting for the Impairment or Disposal of Long-Lived Assets. [Online]. https://www.fasb.org/page/PageContent?pageId=/reference-library/superseded-standards.html&isStaticPage=true&bcPath=tff

- Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). (2001b). Summary of Statement No. 144. [Online]. https://www.fasb.org/page/PageContent?pageId=/reference-library/superseded-standards/summary-of-statement-no-144.html&bcpath=tff

- Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). (2014). Accounting standards update 2014-08. [Online]. https://www.fasb.org/page/PageContent?pageId=/standards/accounting-standards-updates-issued.html

- Financial Reporting Council. (2017, December). Audit Quality Thematic Review: Materiality. Retrieved from https://media.frc.org.uk/documents/Audit_Quality_Thematic_Review_-_Materiality.pdf

- Frank, C. (2020). Discontinued operations under IFRS – interpretation and management. [Online]. https://arro.anglia.ac.uk/id/eprint/706824

- IFRS Interpretation Committee (IFRIC). (2016). IFRIC Update January 2016. [Online]. https://cdn.ifrs.org/-/media/feature/news/updates/ifrs-ic/2016/ifric-update-january-2016.pdf

- International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). (2022a). IFRS 5 Non-current assets held for sale and discontinued operations. In The Annotated IFRS Standards. London: IFRS Foundation.

- International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). (2022b). IAS 8 Accounting Policies, Changes in Accounting Estimates and Errors. In The Annotated IFRS Standards. London: IFRS Foundation.

- International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). (2022c). Non-current Assets Held for Sale and Discontinued Operations – Basis for Conclusions. In The Annotated IFRS Standards. London: IFRS Foundation.

- International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). (2022d). The Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting. In The Annotated IFRS Standards. London: IFRS Foundation.

- International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). (2023). Resources for academics. Evidence-based standard-setting. [Online]. https://www.ifrs.org/academics/#evidence-based-standard-setting

- International Accounting Standards Council. (1998). International Accounting Standard IAS 35 Discontinuing Operations. [Online]. https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/#bound-volumes—translations

- Ji, Y., Potepa, J., & Rozenbaum, O. (2020). The effect of ASU 2014–08 on the use of discontinued operations to manage earnings. Review of Accounting Studies, 25(4), 1201–1229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-020-09535-y

- Jiang, J. (2008). Beating earnings benchmarks and the cost of debt. The Accounting Review, 83(2), 377–416. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2008.83.2.377

- Kaplan, S. E., Kenchington, D. G., & Wenzel, B. S. (2020). The valuation of discontinued operations and its effect on classification shifting. The Accounting Review, 95(4), 291–311. https://doi.org/10.2308/tar-2016-0235

- Keller, G., & Warrack, B. (2003). Statistics for management and economics (6th ed.). Pacific Grove, CA: Thomson/Brooks/Cole.

- Kormendi, R., & Lipe, R. (1987). Earnings innovations, earnings persistence, and stock returns. The Journal of Business, 60(3), 323–345. https://doi.org/10.1086/296400

- Lipe, R. C. (1986). The Information contained in the components of earnings. Journal of Accounting Research, 24, 37–64. https://doi.org/10.2307/2490728

- Marx, B., Van der Watt, A., Bourne, P., & Moloi, T. (2019). Dynamic auditing (14th ed.). Johannesburg: LexisNexis.

- Matsunaga, S. R., & Park, C. W. (2001). The effect of missing a quarterly earnings benchmark on the CEO’s annual bonus. The Accounting Review, 76(3), 313–332. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2001.76.3.313

- McVay, S. E. (2006). Earnings management using classification shifting: An examination of core earnings and special items. The Accounting Review, 81(3), 501–531. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2006.81.3.501

- Mpact Limited Group. (2021). MPact Limited Group Audited consolidated annual financial statements for the year ended 31 December 2021. https://www.mpact.co.za/investor-relations/financial-reports

- Rapaccioli, D., & Schiff, A. (1991). Reporting Sales of Segments Under APB Opinion No. 30. Accounting Horizons, 5(4), 53–59.

- Riedl, E. J., & Srinivasan, S. (2010). Signaling firm performance through financial statement presentation: An analysis using special items. Contemporary Accounting Research, 27(1), 289–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.2010.01009.x

- Ronen, J., & Sadan, S. (1975). Classificatory smoothing: Alternative income models. Journal of Accounting Research, 13, 133–149. https://doi.org/10.2307/2490652

- Stadler, C., & Nobes, C. W. (2014). The influence of country, industry, and topic factors on IFRS policy choice. Abacus, 50(4), 386–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/abac.12035