ABSTRACT

This paper delves into the critical importance of ethical considerations in research, with a primary focus on gender, sex, and sexual orientation. Recognizing the vulnerabilities and complexities inherent in these communities, we emphasize here the necessity of ethical awareness throughout all research phases. Ethical obligations may extend to ensuring cultural sensitivity, safety, and equitable resource distribution. The core ethical principles of autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice are promoted here to serve as a viable framework for ethical research. These principles require meticulous attention to informed consent, minimizing harm, maximizing benefits, and promoting fairness throughout the research process. The paper delves into the intricacies of queer identities, highlighting the fluidity and intersections among gender, sex, and sexual orientation. Recommendations are proposed to integrate ethical principles seamlessly into research. This paper underscores that ethical considerations are not just a regulatory requirement but a moral obligation, essential for upholding the rights and well-being of all individuals. By embedding ethical principles into research, we can contribute to a more inclusive, equitable, and just society, amplifying the voices and experiences of marginalized communities while minimizing harm and promoting social change.

Introduction

Ethical considerations are foundational during research decision-making processes to ensure data quality and validity are not compromised by study procedures (Newman and Kaloupek Citation2009). This aspect is particularly important when research involves marginalized communities such as LGBTQIA+Footnote1 people. This line of ethical considerations in human research is particularly relevant and important in the current climate, which is complex, diverse, intersectional, and could be messy for all stakeholders. Without the awareness and understanding of the nuances in queer identities and intersectionality, researchers would fail to elicit valid data or capture the essence of underlying intersectional identities in their survey research. For example, transgender or queer-identified participants may opt out of responding to the survey that is only associated with and limited in cis-/heteronormative and binary items, and lacking considerations of gender diversity and inclusivity. Given the primacy of ethics in any research, we seek to provide researchers with actionable recommendations that can improve population research methodology, protect ethics, and highlight the value of intersecting individual identities when designing population study surveys.

In the following, we first review and unpack how ethics are considered and enacted in human research, particularly concerning queer cohorts and their intersectional identities. This lays the foundations for understanding how to approach these communities with humility, respect, and most of all, deep listening, akin to Indigenous research approaches (Bobongie-Harris, Hromek, and O’Brien Citation2021). Here we illustrate methodological considerations and caveats that may be included in conducting queer-related research, focusing on population study survey design. Survey design includes creating questions, analysing and interpreting data, and disseminating findings with participants whose diverse backgrounds intersect with their queer identities. We conclude our paper with viable and actionable recommendations for future research. Our hope is to raise ethical awareness and enactment while celebrating gender diversity and inclusivity in any type of human research involving vulnerable, marginalized communities. The time has also come to bring social justice and thus fairness, equity of resources, opportunities, and privileges back to the centre of research by contesting research bias, (un)intentional ignorance, discrimination, and stereotypes.

Overview of ethical considerations in LGBTQIA+ research

Research involving humans is inherently risky (Resnik Citation2020), although it is vital in supporting informed decision-making processes and providing evidence for targeted outcomes (Aguessivognon Citation2022). Research has a deplorable history of exploiting, harming, and abusing marginalized communities (Paquin, Tao, and Budge Citation2019).

Ideologies such as eugenics were considered popular science at the time (How Nature Citation2022), but to avoid what are now considered unacceptable acts, ethical considerations rose to prominence following the horrors of World War II. This included establishing institutional review boards (IRBs), also known as ethics committees, to review and approve medical and behavioural science research projects involving human research participants (Paquin, Tao, and Budge Citation2019; Steinert et al. Citation2021; Tseng and Wang Citation2021). IRBs intended to protect the rights and welfare of the studied participants and ensure that research is conducted ethically (Adams et al. Citation2017). These ethical rules and guidelines must be enforced by researchers and participants to avoid potential risks to themselves and others (Shirmohammadi et al. Citation2018). It could be argued that beyond IRB protocols, the researcher has a personal moral obligation to consider ethics when conducting, analysing, and disseminating the research findings.

Thriving during 1962–1975 in the British Commonwealth were cases where the researchers did not exercise personal morals, values, or relational accountability (Barlo et al. Citation2021). Instead, researchers relied on IRBs alone, leading to an increase in research attempting to ‘cure homosexuality’ (Davison Citation2021). This conversion therapy is now deemed inappropriate and harmful, contributing to higher depression and internalized homophobia (Meanley et al. Citation2020). However, it was seen as acceptable research to conduct by IRBs because homosexuality was a listed mental illness within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) until 1973 (Davison Citation2021). The lack of researchers’ own personal ethical review introspection, reflection and review may have further contributed to the extensive damage to the queer community through these testings of conversion therapies. The dangerous and damaging practice of LGBTQIA+ conversion continues today, with some states in Australia recently enacting legislation to finally ban the practice, whilst others continue to allow the practice to flourish (Parkinson and Morris Citation2021). Thus, regrettably, the destructive impacts of these research studies are still ongoing.

Within the broader context of ethical considerations in research and the impact of harmful practices like conversion therapies, the role of human rights enters the consciousness and requires contemplation and reflection of research practices. Carpenter (Citation2021) emphasizes the need for a comprehensive understanding of human rights principles to inform ethical research practices, as exemplified in the Yogyakarta Principles regarding the application of international human rights law in relation to sexual orientation, gender, and sex (International Commission of Jurists Citation2017). The discussion on surgical interventions still done without consent, and with no medical basis, on young children reinforces how a lack of adherence to human rights principles can lead to ethically harmful research and practice, including modern-day eugenic practices. Evidently, researchers must not solely rely on IRBs but also engage in ethical introspection, considering the potential harm to marginalized communities (Zwickl et al. Citation2021). As highlighted by Carpenter (Citation2021), integrating human rights considerations into research regarding gender, sexual orientation, and sex, can serve as a crucial ethical compass in research, preventing the perpetuation of harm and promoting inclusivity and respect for diverse identities.

According to Staples et al. (Citation2018), the researcher is further obliged to review the research process and confirm that it is culturally sensitive and safe. In communities affected by heterosexism and gender binarism such as the queer community, this requires understanding the trauma and victimization that continues to be perpetuated by ‘unethical’ human research (Campbell, Goodman-Williams, and Javorka Citation2019; Krieger Citation2020). The inherent bias in research is further propagated by participants (formally labelled as ‘subjects’ in human research) who are typically Western, white, heterosexual, cisgender, and male (Paquin, Tao, and Budge Citation2019; Rogers and Kelly Citation2011). According to Saxena et al. (Citation2022), there also continues to be an ongoing absence of attention to sex and gender by ethics committees such as IRBs, including a lack of guidelines and rules when evaluating research through a gender lens – this inequity can reinforce injustice. To compound and potentially confound ethics and the (survey) data gathered, the complexity of diverse identities and lived experiences may be so profound that researchers’ ethical awareness and sensitivity to sociocultural and intersectional diversities plays an even more pivotal role in this regard. Therefore, any patterns found to support or reject hypotheses must either remain (explicitly) exclusive to the homogenous group studied or require extremely large heterogeneous sample sizes to generalize or apply findings to population scales.

To a certain extent, targeting groups already occurs during the promotion of surveying where people are requested to only participate if they are within certain age brackets or other loosely defined parameters. The promotion style may unintentionally exclude specific populations (e.g. online advertisement may exclude rural people who do not have reliable internet access). However, other identity factors not requested or recorded may allow determination of the homogeneity or heterogeneity of the sample group participants, or any biases that arose from the dissemination of that survey. For example, a survey promoted at a university for participants between the ages of 18–25 years old that investigated the level of exercise per week may be influenced by the health background of students such as socioeconomic status, social support, employment, food, housing etc. However, researchers may fail to recognize that education in and of itself is a social determinant of health and then apply findings more broadly. There may also be more nuanced factors, such as where flyers were placed, the time of the year it was advertised, and the length of advertisement before the study occurred.

All these considerations may be considered ethical ones, although they are often not disclosed in methodology, or even considered prior when restricting the findings to small sample sizes of unknown heterogeneity. In essence, how studies are conducted in terms of ethical considerations will inevitably require trade-offs between time, effort, and funding, but also need to recognize the impact on findings in terms of who, where, what, and the purpose of the study. Indeed, while having more questions included in a survey could allow for a greater understanding of the participant’s identity, it may also be an invasion of privacy (regardless of the anonymity of data) because it could potentially distress the participant to disclose such personal information.

What are the guiding principles for ethical considerations?

It is often stated that contemporary researchers must professionally and morally adhere to the highest ethical standards in research (Dubé, Santaguida, and Anctil Citation2022). Nevertheless, many researchers may not be proficient in the requirements of ethical considerations, including the self-criticism and consciousness-raising that should be conducted throughout the entire research process (Campbell, Goodman-Williams, and Javorka Citation2019). Rogers and Kelly (Citation2011) argue that critical reflection is particularly relevant in disseminating results due to the inherent power hierarchy between researcher and participants. Ethics express the values and can guide the researcher on how to achieve them (Paquin, Tao, and Budge Citation2019). Beauchamp and Childress posit four principles that could assist navigation of ethical considerations: autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice (Page Citation2012; Tomson Citation2018; Tseng and Wang Citation2021). Ethical considerations must be balanced to ensure no principle is treated more significantly than another (Tseng and Wang Citation2021), and should all be considered in the research methodology by each researcher.

Autonomy

The principle of autonomy lies in respect for life and self-determination (Aguessivognon Citation2022; Dubé, Santaguida, and Anctil Citation2022; Humbyrd Citation2019) and recognizes the research participants’ capacity and right to make their own informed decisions (Tomson Citation2018). Ethically, this impacts gendered norms and heteronormativity, which should be considered in research (Lee, Rexrode, and Rexrode Citation2021), and heavily aligns with the research principle of informed consent (Humbyrd Citation2019; Newman and Kaloupek Citation2009; Tomson Citation2018). Informed consent requires voluntary agreement without duress or coercion (Folayan et al. Citation2015; Moore et al. Citation2016). Thus, the capability of the individual should be considered, including the impact of trauma, and interpersonal violence which could unduly influence the individual in research (Newman and Kaloupek Citation2009). Considering the inequalities experienced by gender or sexually diverse individuals (Bauer Citation2014), and violence experienced through macro-and-microaggressions (Kung and Johansson Citation2022; Staples et al. Citation2018), it could be argued that autonomy should be a specific focus in research design due to the marginalization experienced by this vulnerable population.

Beneficence

Maximizing beneficence is ensuring that people are helped (Munyaradzi Citation2012; Paquin, Tao, and Budge Citation2019; Tomson Citation2018) and that the research design is methodically sound to ensure there are tangible benefits to the participants (Ellsberg and Heise Citation2002), and society (Aguessivognon Citation2022; Dubé, Santaguida, and Anctil Citation2022). Cost and risk should be weighed against benefits to the participants (Munyaradzi Citation2012). Beckford-Jarrett et al. (Citation2020) state that privacy concerning intersex, gender-diverse or sexually diverse individuals is paramount as it can be a considerable risk for the participant, as can undesirable locations, inconvenient timings, lack of trust in the research team, and lack of community input in research planning and design. Therefore, lived experiences and community involvement from marginalized populations is essential to ensure adequate beneficence during the research project.

Non-maleficence

The principle of non-maleficence is referred to as ‘do no harm’ and is a central tenant of the work of all researchers (Dubé, Santaguida, and Anctil Citation2022; Munyaradzi Citation2012; Tseng and Wang Citation2021). Ellsberg and Heise (Citation2002) believe this principle should extend further and encompass the researcher, especially when they risk hearing stories that could be upsetting or triggering. Physical and mental harm can manifest through ignorance, biases, or insensitive normative language, alienating vulnerable populations (Kung and Johansson Citation2022). Higher rates of suicide, unemployment, sexual abuse and assault, lower income (Staples et al. Citation2018; Tomson Citation2018), and higher reported suicidal thoughts and behaviours (de Graaf et al. Citation2021) are found within gender-diverse and sexually diverse communities due to marginalization. The impact of these social and emotional factors may burden the researcher to ensure the research design, instruments used, and analysis and interpretation elicit no harm. According to Paquin, Tao, and Budge (Citation2019), this may involve the researcher addressing systemic problems, and highlighting oppression in their research to bring these potentially unseen problems to the knowledge of the general public, indicating this principle also engenders the dissemination of research.

Justice

Research can still be deemed ethical, whilst not aligning with the justice principle, when the research does not reduce inequities (Paquin, Tao, and Budge Citation2019). Justice requires resources to be distributed fairly (Tomson Citation2018). It manifests throughout the research design and ensures participant recruitment does not disproportionately include or exclude any individual, and that the risks and benefits amongst the study subgroups are balanced and equitable (Aguessivognon Citation2022; Kung and Johansson Citation2022). Integration of feminist intersectionality in research (Crenshaw Citation1989; Rogers and Kelly Citation2011) whereby a person’s race, class, gender, and sexuality are considered in relation to their impact on all individual’s identities (Warner and Shields Citation2013) during data analysis (Henrickson et al. Citation2020) is essential. It should also appropriately incorporate both qualitative and quantitative methods to provide a holistic view of the study participants (Bauer Citation2014; Rogers and Kelly Citation2011). Therefore, validating, and respecting gender diverse participants through research design and analysis can help achieve justice.

Intersecting queer identities

Queer identities may be limited to a single spectrum, be intersecting, and/or require intersection from another identity. For example, a gay cis man is only queer in his sexual orientation. An intersecting queer identity may be a transgender lesbian, where gender, sex, and sexual orientation are all queer factors. Gender and sex are required to intersect for transgender people, as gender and sex assigned at birth was, or is not currently aligned. Thus, queer identities may have single and intersecting factors to consider when pursuing an ethical research approach. The interaction of queer identity factors may be related to definitions of intersectionality, where identities may intersect in an individual to create a lived experience unique to either single or other intersecting identity factors. When the term intersectionality was first described by Crenshaw (Citation1989) to describe unique discrimination experienced by Black women, but not Black men or white men and women, this may assume static identity factors. However, identities may develop over time and can be fluid (Cass Citation1979, Citation1984, Citation1996), especially true for queer identities. Additionally, novel terminology and concepts are rapidly evolving as queer discourse becomes more socially acceptable and safe spaces for individuals are created to explore. Therefore, it is imperative to recognize that participants may have varying levels of prior knowledge, self-awareness, and/or willingness to disclose identity factors.

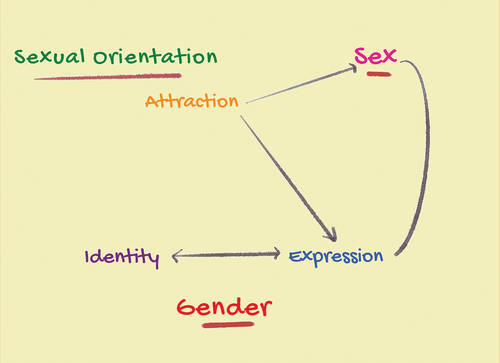

Indeed, critical and thoughtful contemplation on the phrasing of the survey items is vital to affirm the ethical considerations of non-maleficence, autonomy, and justice. Given that queer identities in and of themselves have many complex intersections but can be broadly delineated along three major spectrums of gender, sex, and sexual orientation, each intertwines (see ) and requires deconstruction regarding ethical considerations and caveats as discussed below.

Gender

As gender is often used synonymously with sex, for gender to be used as a separate identity indicator in surveys, the terms may require simple but clear definitions or further explanations to participants. Gender is defined here as the external expression of femininity, masculinity or a lack of either (as expressed by some, but not all non-binary peoples) (AHRC, Australian Human Rights Commission Citation2015). The gender binary, or genderism, incorrectly perpetuates the idea that gender is binary and is linked to the sex assigned at birth (Staples et al. Citation2018) and that nonconforming gender identities are unnatural. It reinforces class, gender, racial/ethnic injustice, and the impacts negatively on cultural differences (Staples et al. Citation2018). The strict gender roles, oppression, heterosexism, along with masculine and feminine ‘rules’, as well as a dimorphic view of sex at birth can ignore the existence of intersex people (Hyde et al. Citation2019) and those who identify as non-binary (between or outside the gender binary) (de Graaf et al. Citation2021). The gender binary also upholds heteronormativity and systemic systems of oppression (Rogers and Kelly Citation2011).

As the understanding of gender as a social construct has become recognized, hence, legitimate (Henrickson et al. Citation2020; Staples et al. Citation2018), some research fields such as sexology have begun to focus on gender-diverse, non-binary, and transgender populations (Henrickson et al. Citation2020). In some instances, inclusive gender demographic data is necessary to increase equity, human rights, and data quality (Bauer et al. Citation2017), indicating a need for ethical considerations (beneficence, and justice) when including this population in research. To be truly inclusive of gender as an identity factor, participants may require a brief explanation as to the difference between gender and sex, as researchers cannot assume this to be prior knowledge (even for targeted studies or participants with queer identities). We also note a concerning trend in transgender, gender diverse, and non-binary research whereby all of these potentially different gender meanings and expressions are being categorized under ‘Trans’. This leads to the reinforcement of a new binary between ‘cis’ and ‘Trans’, and contributes to the erasure of individual identities.

Sex

Biological characteristics of sex are complex, interrelated, and still the topic of novel research outcomes (Bale and Epperson Citation2017). Somewhat ironically, sex is often presented as a false dichotomy, despite the definition of sex relying on multiple biological factors. Genetic, physical, and/or hormonal sex characteristics should all be considered. Genetic sex characteristics typically refers to assemblages of X and Y sex chromosomes, where in humans XY is male, XX is female, and variations are considered intersex (Callahan Citation2009). However, physical sex characteristics are influenced by hormones which may or may not be naturally produced by the individual. Indeed, rather than simplify to a false dichotomy of male or female individuals, with all others being dubbed intersex, the complexity of biological expression in relation to sex suggests another intersecting series of biological spectrums that produces and develops an individual over time. Hormone levels are well documented as changing over time, and the impact of hormones on an individual varies, meaning expression may be affected short or long-term, and even on other identity factors such as sexuality (Auer et al. Citation2014). For example, female menstrual cycle impacts may vary short-term, but going through menopause may yield long-term impacts (Greendale, Lee, and Arriola Citation1999).

Similarly, physical sex characteristics can impact hormones. For example, some cultural practices include castrating males to avoid deepening their vocal cords so that they may continue to sing at higher frequencies (Wilson and Roehrborn Citation1999). Individuals are often unaware of where they are situated at a population level for these biological spectrums, and how other factors in their lives may impact or influence their development over time. Thus, many may remain unaware of variations from the ‘norm’ and not be able to identify their intersex status, even if there is no resistance otherwise.

Despite sex being used as a biological variable for centuries of scientific studies, there are still extreme biases and a lack of ethical considerations in implementation (Shansky and Murphy Citation2021), even when applied as a false binary. The largest historical bias is still being perpetrated as studies are performed using exclusively male participants – that is, male mice are continuing to be used as the default model organism prior to human testing (Shansky and Murphy Citation2021). As rodents do not – to our knowledge – recognize gender as a social construct, and sex in these studies is being assumed by the presence of typical male genitalia (rather than perhaps the more expensive sex-chromosomal and hormone profile testing); the delineation of sex and gender is often not considered applicable to such studies. However, depending on the purpose, findings, and later application, even these early stages of investigation on non- human participants may warrant further ethical considerations including beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice.

Sexual orientation

Sexual orientation relates to a person’s sexual and/or emotional attraction to others (AHRC, Australian Human Rights Commission Citation2015). Diverse sexual orientation is defined here as variation or deviation from heterosexuality, namely, attraction between a cis-woman (female assigned at birth and identifies as a woman) and cis-man (male assigned at birth and identifies as a man). However, the term heterosexuality may also be applied to people who are attracted to the opposite sex and/or gender. For example, a transwoman and a transman may pursue a heterosexual relationship if mutually attracted to each other. However, a typically heteronormative perspective may exclude the latter as heteronormativity by definition excludes those with queer identity factors as being unnatural and therefore ‘lesser than’ (Henrickson et al. Citation2020). Ethical approaches to surveying participants require recognition and respect for self-determination and identity formation. Sexual orientation, like other queer spectrums, has many complex, interacting, and overlapping factors. Again, based on Cass’s identity formation theory (Cass Citation1979), identities can change over time as individuals go through stages of realization before fully accepting an identity, but they may also identify more strongly with new terminology as their knowledge expands. Due to the dynamic terminology and advances in concepts beyond the reviewed literature spaces, it is advisable to have short-answer options for any identity factors to enhance autonomy. Self-descriptions could be included alongside common terms such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, but terms provided by researchers should also have definitions accessible to participants to ensure a common understanding and interpretation of the terms used in line with the ethical consideration of non- maleficence.

Implications of ethical considerations for LGBTQIA+ population research

Opportunity for self-determination in surveying participants with queer identities may foster agency and empowerment for typically oppressed peoples; affirming a right to the ethical principle of autonomy and reinforcing justice. Indeed, amplifying oppressed voices may better inform practices to safeguard beneficence, ensure non-maleficence, and illuminate previously unforeseen issues, as oppressed perspectives are not often made visible without pointed intervention. Safety and anonymity are paramount, not just for protection, but in terms of duty of care, and the acquisition of honest and accurate data. The three main identity factors (gender, sex, and sexual orientation), when defined in accessible language, should be included for participants in a comprehensive, holistic, and rigorous surveying approach, to reinforce all the ethical considerations. However, this is assuming that these identity factors are relevant to the purpose and outcomes of the study. Too often single identity factors such as gender and/or sex are included in forms unnecessarily and inappropriately. For example, a dentist does not need to know the sex (sometimes inappropriately exchanged with the term gender) in order to treat a patient, yet most health forms will contain questions to capture this irrelevant data. Indeed, capturing such data without further contextualization results in biased or inaccurate data and potential harm to the participant, thereby failing the ethical consideration of non-maleficence. As such, ethical considerations in surveying participants require critical analysis and scrutiny of the methodology and purpose of the study during all stages of research methodology and development, especially regarding the relevance of identity data to the study. Thus, the intentions and outcomes of the study should be disclosed to participants to further a sense of safety and informed consent whilst reinforcing autonomy.

Rogers and Kelly (Citation2011) also note that identity factors are often treated as individual factors and used to rank groups hierarchically (i.e. more or less vulnerable). Perpetuating this privilege reinforces a cultural blindness and bias in research spaces and can demoralize population groups. Conversely, inclusion can empower and allow for stronger awareness raising when applied purposefully and ethically. As emphasized by Newman and Kaloupek (Citation2009), ethical considerations can profoundly impact data quality and validity of results by affecting how individuals engage with the study procedures. For this reason, it is important to note that publications in journals are in and of themselves privileged spaces – often there is a lack of accessibility and dissemination of information/results to the actual study participants, or the communities affected by the research and its results. Further to this, systemic barriers reinforced by an inherently cis-/heteronormative society can limit the type and style of research conducted.

Other limitations to the research process include short grant or political cycles and pressure by institutions to produce ‘high impact’ outputs in Q1 journals (Brembs, Button, and Munafò Citation2013). Although longitudinal studies are often considered best practice for social and population studies, these are often not feasible due to limitations in time, effort and funding (Caruana et al. Citation2015). Saxena et al. (Citation2022) further expand on these issues, stressing that the research funding systems, agencies, and IRBs ultimately decide on the research that is funded, ethically approved, and published – defining for themselves what is rigour, quality, and knowledge. As such, it can limit the researcher and be confusing and complex to ensure that they are being inclusive, unbiased, and not culturally blind throughout the research process, including when interpreting data.

Recommendations

Our following recommendations are proposed to reinforce Beauchamp and Childress’s four ethical principles of autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice in all phases of research and decision-making. Effort has been made to strengthen the creation of an inclusive, informed, and culturally safe environment for researchers and participants when working with data that includes sex, gender and/or sexual orientation. below outlines the best practices for making informed decisions on ethical considerations in relation to different stages of population research. Related literature and ethical principles that guide each decision-making process are also provided.

Table 1. Recommendations for ethical considerations in population research.

Conclusion

The ethical principles of autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice are essential considerations for all researchers during their research design, analysis, and dissemination. Gender-diverse, intersex, and sexually diverse populations experience many microaggressions and oppression in general society; therefore, reducing harm whilst increasing benefits to the participants and society is vital. Research should address systemic societal problems while raising awareness of oppression and its role in people’s health and well-being. Building ethical principles and considerations throughout all stages of research, including the pre- planning stage, helps achieve this goal. Acall for more empirical evidence on the integration of intersectionality in research is needed to maximize its value.

Acknowledgment

We wish to express gratitude to our colleagues, whose unwavering commitment to equity, social justice, and human rights has been a guiding light throughout this research journey. Their steadfast belief in the dignity and worth of every individual, and dedication to breaking down barriers of inequality, have not only enriched this work but have also served as a testament to the power of collective action in the pursuit of a just and inclusive society. We are fortunate to have been surrounded by such conscientious and passionate individuals, and we are proud to stand alongside our allies for a world that recognizes the inherent rights and potential of all.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. LGBTQIA+ is an inclusive and evolving acronym that stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, intersex, asexual/ace and other diverse gender and sexualities. It is often interchangeable with the term ‘Queer’. For full definitions, please visit https://shorturl.at/hzV25

References

- Adams, Noah, Ruth Pearce, Jaimie Veale, Asa Radix, Danielle Castro, Amrita Sarkar, and Kai C. Thom. 2017. “Guidance and Ethical Considerations for Undertaking Transgender Health Research and Institutional Review Boards Adjudicating This Research.” Transgender Health 2 (1): 165–175. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2017.0012.

- Aguessivognon, Togla A. 2022. “Research on African Adolescents’ Sexual and Reproductive Health: Ethical Practices and Challenges.” African Journal of Reproductive Health 26 (3): 13–19. https://doi.org/10.29063/ajrh2022/v26i3.2.

- AHRC (Australian Human Rights Commission). 2015. Resilient Individuals: Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, and Intersex Rights. Sydney, NSW: Australia.

- Auer, Matthias K., Johannes Fuss, Nina Höhne, Günter K. Stalla, Caroline Sievers, and M. J. Coleman. 2014. “Transgender Transitioning and Change of Self-Reported Sexual Orientation.” PLOS ONE 9 (10): e110016. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110016.

- Bale, Tracy L., and Neill C. Epperson. 2017. “Sex As a Biological Variable: Who, What, When, Why, and How.” Neuropsychopharmacol 42 (2): 386–396. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2016.215.

- Barlo, Stuart, William E. Boyd, Margaret Hughes, Shawn Wilson, and Alessandro Pelizzon. 2021. “Yarning As Protected Space: Relational Accountability in Research.” AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 17 (1): 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180120986151.

- Bauer, Greta R. 2014. “Incorporating Intersectionality Theory into Population Health Research Methodology: Challenges and the Potential to Advance Health Equity.” Social Science and Medicine 110: 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.022.

- Bauer, Greta R. Jessica Braimoh, Ayden I. Scheim, Christoffer Dharma, and A. R. Dalby. 2017. “Transgender-Inclusive Measures of Sex/Gender for Population Surveys: Mixed-Methods Evaluation and Recommendations.” Public Library of Science ONE 12 (5): e0178043. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0178043.

- Beckford-Jarrett, Sharlene, Robin Flanagan, Annie Coriolan, Orlando Harris, Andrea Campbell, and Nicola Skyers. 2020. “Barriers and Facilitators to Participation of Men Who Have Sex with Men and Transgender Women in HIV Research in Jamaica.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 22 (8): 887–903. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2019.1634222.

- Bobongie-Harris, Francis, Daniele Hromek, and Grace O’Brien. 2021. “Country, Community and Indigenous Research: A Research Framework That Uses Indigenous Research Methodologies (Storytelling, Deep Listening and Yarning).” Australian Aboriginal Studies 2: 14–24. https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/informit.625130518148928.

- Brembs, Björn, Katherine Button, and Marcus Munafò. 2013. “Deep Impact: Unintended Consequences of Journal Rank.” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 7: 291. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00291.

- Callahan, Gerald 2009. Between XX and XY: Intersexuality and the Myth of Two Sexes. Chicago Review Press. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=HlG-8bSgDBgC.

- Campbell, Rebecca, Rachael Goodman-Williams, and McKenzie Javorka. 2019. “A Trauma-Informed Approach to Sexual Violence Research Ethics and Open Science.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 34 (23–24): 4765–4793. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519871530.

- Carpenter, M. 2021. “Intersex Human Rights, Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, Sex Characteristics and the Yogyakarta Principles Plus 10.” Culture, Health and Sexuality 23 (4): 516–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2020.1781262.

- Caruana, Edward J. Marius Roman, Jules Hernández-Sánchez, and Piergiorgio Solli. 2015. “Longitudinal Studies.” Journal of Thoracic Disease 7 (11): E537–540. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.10.63.

- Cass, Vivienne C. 1979. “Homosexuality Identity Formation: A Theoretical Model.” Journal of Homosexuality 4 (3): 219–235. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v04n03_01.

- Cass, Vivienne C. 1984. “Homosexual Identity Formation: Testing a Theoretical Model.” The Journal of Sex Research 20 (2): 143–167. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3812348.

- Cass, Vivienne C. 1996. “Sexual Orientation Identity Formation: A Western Phenomenon.” In Textbook of Homosexuality and Mental Health, edited by Robert. P. Cabaj and Terry. S. Stein, 227–251. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

- Crenshaw, Kimberle 1989. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989 (1): Article 8. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8.

- Davison, Kate 2021. “Cold War Pavlov: Homosexual Aversion Therapy in the 1960s.” History of the Human Sciences 34 (1): 89–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/0952695120911593.

- de Graaf, Nastasja M., Bodi Huisman, Peggy T. Cohen-Kettenis, Jos Twist, Kris Hage, Polly Carmichael, Baudewikntje P. C. Kreukels, and Thomas. D. Steensma. 2021. “Psychological Functioning in Non-Binary Identifying Adolescents and Adults.” Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy 47 (8): 773–784. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2021.1950087.

- Dubé, Simon, Maria Santaguida, and Dave Anctil. 2022. “Erobots As Research Tools: Overcoming the Ethical and Methodological Challenges of Sexology.” Journal of Future Robot Life 3 (2): 207–221. https://doi.org/10.3233/FRL-210017.

- Ellsberg, Mary, and Lori Heise. 2002. “Bearing Witness: Ethics in Domestic Violence Research.” The Lancet 359 (9317): 1599–1604. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08521-5.

- Folayan, Morenike O., Bridget Haire, Abigail Harrison, Morolake Odetoyingbo, Olawunmi Fatusi, and Brandon Brown. 2015. “Ethical Issues in adolescents’ Sexual and Reproductive Health Research in Nigeria.” Developing World Bioethics 15 (3): 191–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/dewb.12061.

- Greendale, Gail A., Nancy P. Lee, and Edga R. Arriola. 1999. “The Menopause.” The Lancet 353 (9152): 571–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(98)05352-5.

- Henrickson, Mark, Sulaimon Giwa, Trish Hafford-Letchfield, Christine Cocker, Nick J. Mulé, Jason Schaub, and Alexandre Baril. 2020. “Research Ethics with Gender and Sexually Diverse Persons.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (18): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186615.

- ”How Nature Contributed to science’s Discriminatory Legacy.” 2022. Nature. 609 (7929): 875–876. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-03035-6.

- Humbyrd, Casey 2019. “Virtue Ethics in a Value-Driven World: Can I Respect Autonomy without Respecting the Person?” Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 477 (2): 293–294. https://doi.org/10.1097/CORR.0000000000000575.

- Hyde, Janet S., Rebecca S. Bigler, Daphna Joel, Charlotte C. Tate, and Sari M. van Anders. 2019. “The Future of Sex and Gender in Psychology: Five Challenges to the Gender Binary.” The American Psychologist 74 (2): 171–193. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000307.

- International Commision of Jurists. 2017. “The Yogyakarta Principles Plus 10 – Additional Principles and State Obligation on the Application of International Human Rights Law in Relation to Sexual Orientation, Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics to Complement the Yogyakarta Principles.” https://yogyakartaprinciples.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/A5_yogyakartaWEB-2.pdf.

- Krieger, Nancy 2020. “Measures of Racism, Sexism, Heterosexism, and Gender Binarism for Health Equity Research: From Structural Injustice to Embodied Harm–an Ecosocial Analysis.” Annual Review of Public Health 41 (1): 37–62. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094017.

- Kung, Winnie W, and Sarah Johansson. 2022. “Ethical Mental Health Practice in Diverse Cultures and Races.” Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work 31 (3–5): 248–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/15313204.2022.2070889.

- Lee, Yeonsoo S., Kathryn M. Rexrode, and K. M. Rexrode. 2021. “Women’s Health in Times of Emergency: We Must Take Action.” Journal of Women’s Health 30 (3): 289–292. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2020.8600.

- Meanley, Steven, Sabina A. Haberlen, Chukwuemeka N. Okafor, Andre Brown, Mark Brennan-Ing, Deanna Ware, James E. Egan, et al. 2020. “Lifetime Exposure to Conversion Therapy and Psychosocial Health Among Midlife and Older Adult Men Who Have Sex with Men.” The Gerontologist 60 (7): 1291–1302. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa069.

- Moore, Quianta L., Amy L. McGuire, Mary A. Majumder, and M. A. Majumder. 2016. “Legal Barriers to Adolescent Participation in Research About HIV and Other Sexually Transmitted Infections.” American Journal of Public Health 106 (1): 40–44. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302940.

- Munyaradzi, Mawere 2012. “Critical Reflections on the Principle of Beneficence in Biomedicine.” The Pan African Medial Journal 11 (29). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22514763/.

- Newman, Elana, and Danny Kaloupek. 2009. “Overview of Research Addressing Ethical Dimensions of Participation in Traumatic Stress Studies: Autonomy and Beneficence.” Journal of Traumatic Stress 22 (6): 595–602. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20465.

- Page, Katie 2012. “The Four Principles: Can They Be Measured and Do They Predict Ethical Decision Making?” BMC Medical Ethics 13 (1): 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6939-13-10.

- Paquin, Jill D., Karen W. Tao, and Stephanie L. Budge. 2019. “Toward a Psychotherapy Science for All: Conducting Ethical and Socially Just Research.” Psychotherapy Theory, Research, Practice, Training 56 (4): 491–502. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000271.

- Parkinson, Patrick, and Philip Morris. 2021. “Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and the Criminalisation of ‘Conversion Therapy’ in Australia.” Australasian Psychiatry 29 (4): 409–411. https://doi.org/10.1177/10398562211014220.

- Resnik, David B. 2020. “Environmental Health Research Involving Human Subjects: Ethical Issues.” Environmental Health Insights 2 (1): EHI.S892. https://doi.org/10.4137/EHI.S892.

- Rogers, Jamie, and Ursula A. Kelly. 2011. “Feminist Intersectionality: Bringing Social Justice to Health Disparities Research.” Nursing Ethics 18 (3): 397–407. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733011398094.

- Saxena, Abha, Emily Lasher, Claire Somerville, and Shirin Heidari. 2022. “Considerations of Sex and Gender Dimensions by Research Ethics Committees: A Scoping Review.” International Health 14 (6): 554–561. https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/ihab093.

- Shansky, Rebecca M., and Anne Z. Murphy. 2021. “Considering Sex as a Biological Variable Will Require a Global Shift in Science Culture.” Nature Neuroscience 24 (4): 457–464. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-021-00806-8.

- Shirmohammadi, Maryam, Shahnaz Kohan, Ehsan Shamsi-Gooshki, and Mohsen Shahriari. 2018. “Ethical Considerations in Sexual Health Research: A Narrative Review.” Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research 23 (3): 157. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijnmr.IJNMR_60_17.

- Staples, Jennifer M., Elizabeth R. Bird, Tatiana N. Masters, and William H. George. 2018. “Considerations for Culturally Sensitive Research with Transgender Adults: A Qualitative Analysis.” The Journal of Sex Research 55 (8): 1065–1076. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1292419.

- Steinert., Janina I, David Atika Nyarige, Milan Jacobi, Jana Kuhnt, and Lennart Kaplan. 2021. “A Systematic Review on Ethical Challenges of ‘Field’ Research in Low- Income and Middle-Income Countries: Respect, Justice and Beneficence for Research Staff?” BMJ Global Health 6 (7): e005380. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005380.

- Tomson, Anastacia 2018. “Gender-Affirming Care in the Context of Medical Ethics – Gatekeeping V. Informed Consent.” South African Journal of Bioethics and Law 11 (1): 24. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAJBL.2018.v11i1.00616.

- Tseng, Po-En, and Ya-Huei Wang. 2021. “Deontological or Utilitarian? An Eternal Ethical Dilemma in Outbreak.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (16): 8565. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168565.

- Warner, Leah R., and Stephanie A. Shields. 2013. “The Intersections of Sexuality, Gender, and Race: Identity Research at the Crossroads.” Sex Roles 68 (11–12): 803–810. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-013-0281-4.

- Wilson, Jean D., and Claus Roehrborn. 1999. “Long-Term Consequences of Castration in Men: Lessons from the Skoptzy and the Eunuchs of the Chinese and Ottoman Courts.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 84 (12): 4324–4331. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.84.12.6206.

- Zwickl, S., Alex F.Q. Wong, Eden Dowers, Shalem Y-L. Leemaqz, Ingrid Bretherton, Teddy Cook, Jeffery D. Zajac, Paul S.F. Yip, and Ada S. Cheung. 2021. “Factors Associated with Suicide Attempts Among Australian Transgender Adults.” BMC Psychiatry 21 (1): 81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03084-7.