Abstract

Investigators undertaking goal-setting research in sport have often focused on the effects of goal content, while those writing professional practice literature have suggested how practitioners could set goals with clients. Few empirical investigations have concentrated on understanding how and why sport psychology practitioners (SPPs) use goal setting or the active ingredients contributing to intervention effectiveness. By adopting a 2-stage, multiple methods approach, we aimed to identify how and why SPPs used goal setting and what contributed to their successful and unsuccessful experiences of setting goals. In Stage 1, 84 accredited/certified SPPs and 16 SPPs in training on an accreditation/certification pathway completed an online survey to identify how and why they set goals. In Stage 2, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 14 participants that explored their experiences of goal setting and elaborated on findings generated in Stage 1. Our findings illustrate that goal setting is a dynamic process, and we identified several common steps across participants. Goal setting was used to enhance psychological and performance outcomes, but the process was influenced by client, contextual, and practitioner factors. Aspects perceived to influence the effectiveness of goal setting included: the attitude of the client toward goal setting; setting appropriate goals; and reflecting, tracking, and monitoring progress. When implementing goal setting in practice, our findings suggest that SPPs can expect steps of the intervention to differ between clients. Furthermore, practitioners might consider the commitment of the client to the process and following up after the intervention as factors that could contribute to successful outcomes.

Lay summary: Sport psychology practitioners (SPPs) reported taking different steps to educate and evaluate their clients before they set goals. After setting goals, SPPs prepared clients to work toward them and followed up on their progress. A client’s attitude toward goal setting, setting appropriate goals, and monitoring progress were reported to contribute to successful goal-setting interventions.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Goal setting is a dynamic process, dependent on the client, context, and practitioner.

Setting the right type of goals with the client and following-up on their progress are important parts of the goal-setting process.

Sport psychology practitioners should collaborate with clients through the goal-setting process, but also provide clients autonomy to select their own goals.

Goal setting has been widely researched and written about in sport psychology (Lochbaum et al., Citation2022). Meta-analytic evidence shows goal setting is an effective strategy for enhancing performance (e.g., Kyllo & Landers, Citation1995; Lochbaum & Gottardy, Citation2015), with recent evidence accumulating on the effects of goals in the sport domain (e.g., the content of goals that are most effective—see Williamson et al., Citation2022) and the application of theories in interventions (e.g., Jeong et al., Citation2023). Applied sport psychology service delivery, however, involves more than knowledge of the effectiveness of specific interventions (e.g., what are the most effective types of goals to set?)—it also demands understanding of how to tailor services to clients when attempting to navigate the complexities of applying psychological interventions in real-world sport settings. Although suggestions have been offered within the professional practice literature on processes to follow when setting goals (e.g., Widmeyer & Ducharme, Citation1997), little consideration in current goal-setting research has been given to the experiences of sport psychology practitioners (SPPs) when using goal setting in practice. Therefore, further study into the experiences of SPPs when setting goals is warranted to inform recommendations on how to implement goal setting effectively with clients.

There appears to be agreement in the existing sport psychology literature that goal setting is a more complex process than just determining an aim. A recent review on ways to implement goal setting presented a synthesized model for SPPs that could guide practice (i.e., steps before, during, and after goal setting; Bird et al., Citation2024). The model comprised four broad stages, with only one stage specifically dedicated to the action of setting a goal. Within the preparation stage, SPPs were encouraged to conduct a needs analysis, identify goal motives, and offer goal-setting education. The goal-setting stage focused on factors that SPPs might consider when setting goals, such as goal content and the prioritization of any set goals. The planning stage was described as a point to develop goal commitment, identify strategies and barriers to attainment, and specify strategies for feedback and monitoring. Lastly, the follow-up stage was proposed to involve reinforcement of goal progress, revision of goals, and rewarding goal achievement after (and during) a period of goal striving.

Although guidance on how to conduct goal-setting interventions has been offered in the sport psychology field, there is a limited amount of literature on practitioners’ reflections when setting goals. The limited existing research in this area, however, shows goal setting can be complex and challenging to implement. For instance, when reflecting on goal setting with a women’s collegiate soccer team, Gillham and Weiler (Citation2013) found positive outcomes associated with setting goals, including increased effort and focus during training, but also identified several issues. The authors stated they found it difficult to follow their proposed goal-setting plan as the limited availability of coaches to regularly record goals prevented them from evaluating progress and providing feedback. Further difficulties were related to coaches sharing goals with players and coaches adjusting goals on a match-to-match basis. Similarly, Maitland and Gervis (Citation2010) recognized the difficulties of setting goals when investigating a goal-setting intervention in youth soccer. In concluding that goal setting is more complex than simply following the “SMART” principles (i.e., setting specific, measurable, adjustable, realistic, and time-oriented goals), the authors suggested that player motives and individual preferences, as well as coach influences, may impact the effectiveness of goal setting. Alongside these practitioner reflections, findings from intervention studies have highlighted challenges with different parts of the goal-setting process. For example, Wanlin et al. (Citation1997) reported contrasting participant engagement in, and enjoyment of, using a logbook for tracking goal progress, while Burton (Citation1989) described how reduced confidence, concentration, and effort resulted from having unrealistic goals. Additionally, in a focus group study, Bell et al. (Citation2022) explained that youth athletes discussed difficulties with differentiating between goal types and some felt setting goals was detrimental to their performance. Previous empirical studies, therefore, begin to highlight the challenges of delivering goal setting in practice, but further research is needed to better understand the nuances and complexities of the goal-setting process. As the SPP plays a critical role in the delivery and effectiveness of sport psychology services (Poczwardowski, Citation2019), such research would offer insights into how practitioners can better execute stages in the goal-setting process, thereby enhancing the likelihood of achieving the expected outcomes from this intervention.

To advance the understanding of goal setting in applied sport psychology practice, our aim was to identify how goal setting is used by SPPs. To achieve this aim, we sought to address four research questions (a) what factors influenced SPPs’ use of goal setting?; (b) how do SPPs set goals with clients?; (c) what outcomes do SPPs expect from setting goals?; (d) what do SPPs perceive contributes to successful and unsuccessful experiences of goal setting. By exploring the lived experiences of SPPs, we sought to generate novel insights into the real-world application of goal-setting interventions in sport. In turn, this evidence could support the professional development and educational needs of SPPs and enable them to implement goal setting more effectively in practice.

Methods

Research approach

In the current study, we were guided philosophically by pragmatism (Creswell, Citation2009). We deemed a pragmatic stance to be appropriate to address our research questions as it places emphasis on understanding human experiences and addressing practical, real-world problems (Creswell & Clark, Citation2017). In adopting a pragmatic philosophical position, we assumed that the process of creating knowledge was social and shaped by the contexts (e.g., sport psychology consultancy) in which the phenomenon (i.e., goal setting) and research occurred (Creswell, Citation2009). Coherent with a pragmatist position, we used multiple methods to generate data across two stages. In Stage 1, a multi-methods online survey was created to identify what influenced SPPs in using goal setting, how they set goals, and the outcomes they expected because of setting goals. As interviews can develop an in-depth account of people’s experiences (Sparkes & Smith, Citation2014), we chose to conduct interviews in Stage 2 to explore SPPs’ successful and unsuccessful experiences of setting goals with clients, with this stage also used to obtain additional insight on how practitioners set goals developed through Stage 1. We obtained ethical approval for the study from the first author’s institution (Ref: 9039).

Stage 1 - survey

Participants and recruitment

Individuals were eligible to take part in Stage 1 if they were accredited/certified SPPs or were in training on a pathway to accreditation/certification in sport psychology. We used two approaches to recruit participants. First, we sent direct emails on two occasions, two weeks apart, to accredited SPPs who listed their email address online through an accrediting body’s website (e.g., Association for Applied Sport Psychology [AASP]). Second, we recruited participants via posts on social media. Recruitment messages outlined the purpose of the study, inclusion criteria, and contained a link to the information sheet, consent form, and survey. A total of 84 accredited practitioners and 16 trainees (N = 100; M age = 38.73 years, SD = 11.15), with an average of 10.34 years (SD = 8.34) experience delivering sport psychology services, completed the online survey. Participant demographic information for Stage 1 can be found in .

Table 1. Participant demographic characteristics from stage 1 and stage 2.

Data collection

After providing informed consent, we presented participants with a series of demographic and background items. In the next section, we posed a series of questions related to goal-setting practices. We asked participants to report on the proportion of clients (i.e., individual and groups/teams) they used goal setting with, as well as the frequency with which they employed goal setting with them. Following these multiple-choice questions, we asked participants to respond to a series of open-ended questions. We chose this approach as online qualitative survey questions can be useful when seeking to capture a diverse range of perspectives and when researchers are interested in gathering relatively focused information on a topic (Braun et al., Citation2021). In line with our research questions, we asked participants to list and define the types of goals they used (“What types of goals do you use in your work with clients? Please list and define the different types of goals you use in the following format: ‘Goal type – Definition of goal type.’”), the stages involved in goal setting (“Can you describe the steps involved [i.e., before goal setting, during goal setting, and after goal setting] in your use of goal setting when working with a client?”), what influenced their decision to use goal setting (“What influences your decision to use goal setting when working with clients?”), and any outcomes they expected from goal setting (“What outcomes do you expect as a result of using goal setting with your clients?”). We lastly asked participants if they were willing to take part in a follow-up interview by providing their email address. Completion of the survey took between 15 and 20 minutes.

Data analysis

Data analysis during Stage 1 was led by the first author. As a certified mental performance consultant, the first author had been educated on goal setting and had extensive experience of using goal setting in their practice. As a result, the first author held a degree of experiential ‘insider-ness’ (Dwyer & Buckle, Citation2009) in relation to core topic of the research project. Although this conferred some benefits (e.g., the first author had insights into the complexity of applied practice), the first author remained cognizant throughout of the importance of retaining a ‘critical distance’ from the insights shared, an outcome supported by his engagement in critical friends’ discussions (Smith & McGannon, Citation2018) with the fourth author throughout the duration of the project (see Rigor).

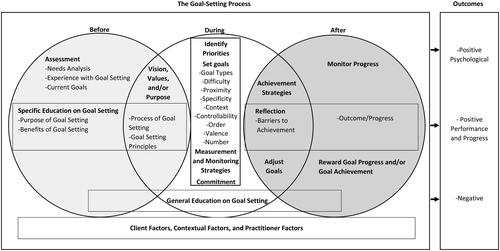

Descriptive and frequency statistics were calculated for quantitative items using SPSS version 28. Responses to each open-ended question were analyzed following guidelines for content analysis (Schreier, Citation2012). After familiarization with responses that addressed our research questions, the first author identified relevant segments of text and generated codes by summarizing the meaning of its content (e.g., the text segment ‘increase in confidence when those goals are attained’ was coded as ‘confidence’). The first author then grouped codes together to create more substantive categories for each research question (e.g., the codes ‘confidence’ and ‘motivation’ were clustered into the category ‘positive psychological outcomes’). To synthesize findings related to the stages of goal setting, we created a visual map that sequentially depicted the goal-setting processes before, during, and after setting goals. This process enabled the development of an initial model illustrating the process of goal setting and highlighted overlaps and distinctions between the different stages.

Stage 2 - interview

Participants and recruitment

Thirty-five participants from Stage 1 agreed to be contacted about a follow-up interview. For Stage 2, all 35 participants were emailed directly and invited to take part in an online interview. Of the participants who responded, 14 agreed (two declined) to take part (male n = 7, female n = 7; M age = 35.64 years, SD = 9.82). Demographic characteristics of participants in Stage 2 can be found in .

Data collection

Participants completed a separate consent form before their online interview with the first author. We used a semi-structured interview approach, whereby the first author asked questions from an interview guide but retained the flexibility to pose curiosity-driven questions to generate discussion and more elaborative information (Smith & Sparkes, Citation2016). The semi-structured interview guide comprised three sections and 10 questions. To elicit information about each participant, we asked a series of questions about their background in sport psychology and their current practice. The main interview section then focused on their experiences of using goal setting. We asked participants how they used goal setting in their applied work (“How do you use goal setting within your applied work?”), before prompting them to describe any examples of successful (“Can you tell me about your successful goal-setting experiences with clients?”), and then unsuccessful (“Can you tell me about your unsuccessful goal-setting experiences with clients?”) goal-setting experiences with clients. In the final section of the interview, we presented participants with the preliminary visual model developed in Stage 1 detailing the stages involved in goal setting. Consistent with the member reflections process (Tracy, Citation2010), we viewed the final part of the interview as an opportunity to seek additional insight on the process of goal setting. Specifically, we asked participants to comment on how the initial findings resonated with their approach, if anything else should be considered, and if they had any further comments or questions. The interviews lasted 59 minutes and 20 seconds on average (range 47:33 to 76:25) and were recorded and transcribed verbatim by the first author in preparation for data analysis.

Data analysis

To analyze data generated in Stage 2, we again followed guidelines for content analysis (Schreier, Citation2012). The first author initially familiarized himself further with the dataset by listening on multiple occasions to the interview audio recordings. After this period of indwelling (Maykut & Morehouse, Citation2002), the first author searched for data related to factors that contributed to SPPs’ successful and unsuccessful experiences of setting goals and condensed relevant segments of text into codes (e.g., the quote “But they weren’t realistic in terms of… OK, how about how frequently are you actually going to work on this? Like, do you have enough time in the day to go to the bullpen.” was coded as ‘realistic goals’). The first author then collated similar codes into more substantive categories (e.g., the codes ‘realistic goals’ and ‘controllable goals’ were integrated into the category ‘setting appropriate goals’). A final feature of this stage of the analysis was consideration of additional data generated in relation to the process of goal setting through Stage 2 interviews, with relevant data analyzed in accordance with the process outlined in Stage 1 and added to that analysis.

Rigor

In the current study, we took several actions to enhance rigor. We sought to achieve rich rigor (Tracy, Citation2010) by collecting data in two stages and recruiting SPPs practicing in different countries. Furthermore, we also aimed for rich rigor by engaging in the ‘critical friends’ process (Sparkes & Smith, Citation2014). During the analysis, the first and fourth authors met regularly to discuss progress made on the analysis, with the fourth author acting as a critical friend (Smith & McGannon, Citation2018). In these meetings, the first author shared and justified their interpretations of the dataset, while the fourth author’s role was to offer feedback on, and challenge, the first author’s interpretation via questioning (e.g., What led you to arrive at that interpretation?). In addition, the fourth author offered alternative suggestions on how the dataset could be interpreted and represented (e.g., suggested the inclusion of ‘working alliance’ as a positive psychological outcome), and encouraged the first author to consider how the findings could be useful for practitioners (e.g., What might a practical implication of this be?). By seeking additional insight in Stage 2 on the initial findings concerning the process of goal setting developed in Stage 1, we sought to increase the credibility of our research through the member reflections process (Tracy, Citation2010). For instance, because of opening dialogue with participants about our initial analysis, we gained further elaboration on the model developed (e.g., how education is an underlying factor to all steps in the process) and enhanced our confidence in the findings generated. Furthermore, the dialogue helped us to sense the resonance of the findings (Tracy, Citation2010), with the participants’ responses suggesting that the findings appeared to hold the potential for naturalistic generalizability (Stake, Citation1995). Finally, we sought to make a significant contribution (Tracy, Citation2010) by presenting findings that could have practical significance for SPPs.

Results

Most participants used goal setting and more than two-thirds reported using goal setting with at least half of their individual clients (none of them = 3%, some of them = 25%, half of them = 14%, most of them = 28%, and all of them = 30%) and group clients (none of them = 6%, some of them = 26%, half of them = 15%, most of them = 34%, and all of them = 19%). More than 75% of participants reported using goal setting on at least some occasions with their individual clients (never = 1%, rarely = 11%, sometimes = 29%, often = 33%, and always = 26%) and group clients (never = 7%, rarely = 8%, sometimes = 39%, often = 32%, and always = 14%). The characteristics and definitions of goals set with are presented in . Consistent with our research questions, the findings are presented in four sections: goal-setting influences; how goals are set: steps in the goal-setting process; goal-setting outcomes; and goal-setting experiences: common factors of successful goal setting.

Table 2. Goal characteristics, participant definitions, and number of participant endorsements.

Goal-setting influences

Participants described several factors that influenced their decision to set goals and we organized these into three categories: client factors; contextual factors; and practitioner factors. Client factors included the personality (e.g., goal-orientations), preferences (i.e., desire to engage in goal setting), and readiness/commitment of the client for goal setting. Illustrating the role of readiness/commitment, participants explained that goal setting was more likely to commence sooner if clients displayed a strong desire to change a behavior in an initial meeting. Further factors reported by participants to influence whether goal setting was used, when it was used, and how it was used included a client’s history with goal setting (e.g., prior experience, structures, or success), their knowledge of goal setting, their age/developmental level, and the composition of their support networks (e.g., could goal pursuit be supported?). Participants consistently highlighted the importance of the needs analysis, when deciding on the use of goal setting. Goal setting could be used if a desired outcome was changes in motivation, confidence, or focus (i.e., shifting from an outcome to task focus). Summarizing many of these client factors, one participant stated that influences included “what they need/want, the use of current goal-setting structures, whether motivation is an issue, whether it is for themselves or an external body (coach/organization), athlete age and knowledge of their sport” (Survey participant 25).

Numerous contextual factors were described as influencing SPPs’ use of goal setting. Common considerations included the time to complete goal setting or the stage within the season (e.g., pre-season), and the team culture and sport type. One participant discussed how the nature of the environment influenced their practice: “traditional goal setting also doesn’t always seem as productive in this environment [professional sport] for me due to the nature of the sport of baseball. [There is] Too much failure and too many uncontrollables” (Survey participant 45). As many athletes in professional baseball are working toward the same target, this SPP placed increased focus on the consistent challenges they would face in reaching their aims, rather than the goals themselves. Participants also referred to the impact of conducting goal setting at the group or individual level, the influence of the coach, and resources available to the athlete. For instance, survey participant 87 reported it is “often is requested by coaches as well, particularly when working with youth,” highlighting the influences of contextual- and client-related factors.

A core practitioner factor influencing the use of goal setting reported was the education of a practitioner, whereby SPPs were likely to use goal setting as they had been trained to implement it. Other factors inherent to the SPP that influenced the use of goal setting included a consulting philosophy/theoretical paradigm and their understanding of scientific literature supporting the use of goal setting. Many practitioner factors were captured in the following extract from a response by one participant:

The major reason I use goal setting is that I believe it’s a fundamental mental skill to use with athletes/teams. It helps with focus and motivation. Provides direction to both athletes/teams and the consultant. Plus, the literature is quite robust in that goal setting is very effective. (Survey participant 68)

How goals are set: steps in the goal-setting process

Based on our analysis of the survey responses and interviews, we interpreted a set of common steps SPPs engaged in when implementing goal setting. These steps appeared to occur in different stages (i.e., before, during, and after goal setting), with some happening specifically within a single stage, while others overlapped across multiple stages. The process of goal setting, therefore, was fluid, with iterative shifts between stages identified. In , we present a map depicting the steps involved in the goal-setting process. It should be noted that the approaches to goal setting described by participants were idiosyncratic and that the composite map represents an amalgamation of the steps reported by participants across the sample. As some steps in the goal-setting process shared a similar purpose, we have organized our presentation of findings for this research question into five categories: education; evaluation; goal setting; preparation; and following-up.

Figure 1. A composite conceptual map of steps in the goal-setting process, goal-setting influences, and outcomes associated with setting goals.

Education

Education was a prominent feature of the goal-setting process, with steps related to general education on goal setting and specific education on goal setting being reported. Specific education on goal setting (i.e., education as a specific step in the process) tended to be provided before any goals had been set or while setting goals. Participants described the provision of general education (i.e., how the SPPs taught clients to conduct all steps to goal setting) as a factor that potentially underpinned all other steps. When specific education on goal setting occurred before goal setting, participants reported educating clients on the purpose and benefits of setting goals. Specific education could also happen when participants were setting goals with clients. Discussions in this step usually included information about the process of setting goals and the different goal-setting principles (e.g., goal types, goal difficulty, goal controllability). One participant elaborated on how they educated athletes on the different types of goals:

I explain the different types of goals, namely; outcome, performance and process. I mention that the outcome goals will always be there because the athlete will always want to win, so we don’t need to focus on these. Then, I introduce the performance and process goals as goals that are under the athlete’s control, and he or she should be focused on them. I often explore with the athletes if they had performances in which they lost but felt good with their performance, and times when they felt bad about the performance. Then we explore what will make the athlete feel like they had a good performance regardless of outcome for the upcoming competition or practice. (Survey participant 13)

Evaluation

Participants explained that an evaluation of the client took place before or during goal setting. A step of assessment was reported to take place before goal setting with participants stating they conducted a needs analysis to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the client. In the current study participants also explained how they understood any client factors that may influence the goal-setting process using reflection. Identifying the current goals of a client, including any progress and strategies used to move toward that goal, was also mentioned, as existing goals could inform if any new goals needed to be set. For some, the type of assessment varied depending on contextual factors, such as the stage of the season:

Before the start of the season, I will invite a client to reflect on the purpose for their sport participation. Goal setting will align with that purpose. During the season, the athlete will consider context and the challenge of the race in developing competitive goals for each race. (Survey participant 28)

Evaluating the vision, values, and/or purpose of the client was a step reported to take place before or during goal setting, but the way this was achieved appeared to be determined by a SPP’s consulting philosophy/theoretical paradigm. For example, one practitioner adopting a humanistic approach stated they would “start with establishing some overarching purpose or vision associated with the goal-setting exercise” (Survey participant 46). In contrast, a practitioner taking a cognitive-behavioral approach reported they would “look at the clients foundation for values and morals to assist them with goal setting” (Survey participant 36). More specifically, SPPs who aimed to identify a client’s values reported using these to guide the types of goals they set, as indicated by one participant: “Identify clear values, then identify process goals that support those values” (Survey participant 66). Practitioners working from an existential approach mentioned that they might help the athlete identify their purpose in life. Thus, our analysis suggested that how the vision, values, and/or purpose of the client were established depends on the approach to practice taken by the SPP.

Goal setting

After a client evaluation had taken place, a preparatory step for setting goals was identifying priorities. As stated by one participant, identifying priorities allowed the client to “consider what is important for you to improve in order to achieve your goal” (Survey participant 35). Identifying the priorities of the client was based on the assessment and vision, values, and/or purpose of the client and was used to highlight areas where clients might set goals.

Once priority areas had been identified, participants set goals with their clients in the during stages of the goal-setting process. When setting a goal, participants described using numerous principles of goal setting. Principles included goal types, difficulty, proximity, specificity, context (i.e., setting goals in training and competition), controllability, order (e.g., set outcome goals first followed by process goals), valence, and the number of goals set (typically ranging between one to three depending on the type of goal).

Preparation

Steps to prepare the client to strive toward their goals were reported to take place once goals had been set. Participants reported the identification of measurement and monitoring strategies, which included planning ways to provide athletes with feedback. By devising measurement and monitoring strategies, participants explained that this prepared both the SPP and client for a micro-needs analysis within the goal-setting process and provided them with the capacity to determine when athletes would know their goals have been reached. As stated by one participant: “Assessment of goals that are important to client [discussion, reflection, performance profiling scale assessments] and how we will track progress [journaling, logging, post routines]” (Survey participant 69), multiple measurement and monitoring strategies might be used.

After goals have been set, a further step reported by participants to prepare a client for goal striving was the identification and enhancement of goal commitment. Participants suggested that identifying commitment to a goal could help in planning achievement strategies and if the right goal has been set for the client: “We have to be 100% committed to this and we can’t go to plan B and plan C because we have to know if this goal is going to stick or not, or this is the right goal for you” (Interview participant 13). As indicated in the quote, commitment was considered key to the effectiveness of the process.

To help clients prepare for reaching their goals, participants reported the identification of achievement strategies during and after setting goals. Strategies could be a series of actions or plans related to how they may strive toward their goals, such as “Mak[ing] the goals visible [and] put[ting] them in the locker room or somewhere else frequently visited” (Survey participant 5). In some cases, linking identification of achievement strategies to barriers faced when goal striving, the use of mental contrasting with implementation intentions was described, as some stated that they worked with clients to identify obstacles and ways to overcome them through the formation of ‘if…then…’ plans.

Reflection was another step reported by participants to help prepare the client to strive toward their goals, but this step was also used to follow-up on progress. The timing of reflection within the goal-setting process appeared to influence how it was used. In the during stage, participants reported that reflection helped prepare the client by focusing on identifying barriers to achievement that could prevent clients from reaching their goals. As one participant stated: “we’re checking-in on goals and discussing contingency plans for when setbacks, roadblocks, and failure are encountered” (Survey participant 83). Continually checking in appeared to provide the SPPs with an avenue to adjust a newly-set goal if it seemed unattainable. In the after stage, participants explained that reflection was used to follow-up on progress. Reflection in this later stage could include a reflection on whether the goal was achieved and identifying the reasons for achievement. One participant spoke about “checking in and re-evaluating goals [biweekly, weekly, monthly, etc.], reflecting on what went well, what could be improved, was goal achieved, why or why not” (Survey participant 23). As portrayed here, reflecting on the progress after a period of goal striving could be connected to goal monitoring and adjustment.

Following-up

A step to monitor progress was used to follow-up with the client and occurred after goals had been set. One participant reported how monitoring was linked to reflection: “We then lay out the goal plan within a desired timeframe, often 60–90 days and establish periods for evaluation during the plan. After completing the goal plan for the predetermined period, then we reflect on how it went” (Survey participant 46). This response highlights the temporal aspect to goal setting and how short-term and long-term goals can help facilitate goal monitoring.

Another step to follow-up with a client was to adjust goals. Participants reported that goals could be adjusted within the during and after stages of the goal-setting process. In the during stage, participants explained goals may be adjusted depending on any barriers that had been identified when setting goals. In the after stage, participants outlined that adjustments might be facilitated by the earlier step of measurement and monitoring strategies, as this set the opportunity for adjustments to be made following progress monitoring (i.e., in the after stage), with goals being revised based on progress toward them. Participants reported that adjustment could occur if the goal was too challenging: “resetting of goals that are more realistic and the cycle continues” (Survey participant 15). This participant quote also reflects the continual nature of goal setting through the adjustment/creation of new goals after a period of goal striving.

When following-up with clients after goal setting, participants reported a step to reward goal progress and/or goal achievement when steps toward the goal had been made, or once the goal had been completed. Occurring after monitoring progress and achievement, rewards reported by participants included using positive reinforcement, celebrations of goal achievement, or the creation of a success list (e.g., “Adding ‘achieved goal’ to an evidence list and adjusting or reaffirming long and short-term goals” [Survey participant 69]). Some also reported that discussion around how goal setting could be continually used might also occur, which could result in a re-start of the process, or progression of the client’s ability to set goals by themselves.

Goal-setting outcomes

A range of outcomes were attributed to setting goals with clients. SPPs reported many positive psychological outcomes they expected from goal setting, including enhanced accountability, commitment, responsibility, confidence, enjoyment, and motivation. Some practitioners expected positive outcomes for a client including improved focus, greater attention to aspects of performance they can control, and a change in mindset (e.g., development of a process-orientation compared to an outcome-orientation). Increased self-awareness, identifying goal progress, knowing what is needed to achieve a goal, and helping clients gain clarity of their values were also reported as further outcomes. Better self-regulation was noted, with one participant stating they used goal setting “for clients to develop their self-regulation abilities [and] for clients to be educated on a goal-setting process they could undergo outside of sport psychology sessions” (Survey participant 1). Finally, increased client satisfaction and an improved working alliance were reported as other expected outcomes of goal setting.

Participants identified positive performance- and progress-related outcomes because of goal setting. Expectations for increased performance were often attributed to enhanced psychological outcomes, such that some participants reported using goal setting for clients to “increase motivation, focus on control, feel confident in selves for accomplishing goals, enjoyment, and hopefully increase performance” (Survey participant 67). Making progress toward a goal, or identifying clear strategies or pathways, were outcomes related to progress:

I want them to complete all of the tasks they can control knowing that improved performance or a specific outcome isn’t guaranteed by compliance with the goal-setting program. Rather, I want them to simplify their approach to pursuing improvement. (Survey participant 46)

Two participants outlined negative outcomes of setting goals with clients. These outcomes included heightened expectations, stress, and anxiety. An unwanted focus on the outcome, decreased resilience, lowered enjoyment, and more rigid thinking patterns, in addition to avoidance-habit loops, burnout, and a lower likelihood of entering a flow state, were also reported: “Based on personal experience, goal setting often leads to increased anxiety and stress. It can also lead to higher expectations and can turn even process-oriented goals into outcomes themselves” (Survey participant 57). Overall, the anticipated outcomes of goal setting were positive, but this participant shared insight into some negative consequences of goal setting.

Goal-setting experiences: common factors of successful goal setting

Findings from the online interview provided insight into factors that participants felt influenced goal setting based on their experiences-both successful and unsuccessful-of setting goals with clients. Four themes related to common factors of successful goal setting were developed: the attitude of the client toward goal setting; collaboration and autonomy; setting appropriate goals; and reflecting, tracking, and monitoring progress.

The attitude of the client toward goal setting

SPPs recognized how the client’s attitude toward goal setting impacted the intervention’s effectiveness, from the onset of goal setting through to goal completion. Successful experiences of setting goals were generally attributed to clients approaching goal setting with a positive attitude, which could be indicated by the excitement and buy-in to the process of setting goals. As one participant pointed out:

So much of what we do depends on their level of buy-in right and their commitment to being able to do this was really important. And they committed to, you know the accountability or the checking in on themselves and following up they were, they have to be the ones that follow through with that and that’s something that they had a really strong buy-in for. (Interview participant 3)

Another characteristic of a positive attitude toward goal setting was the perceived level of client engagement. Illustrating this, several participants spoke about purposeful attempts to ensure client engagement, with one participant stating:

I strategically plan when we can do goal setting so that like when they’re ready for it, they’re like they’re ready to embrace it, which is, yeah, you need. You still need to get a read on the person on the first call and situation to even make that. (Interview participant 11)

Other factors participants described as being indicative of a positive attitude toward goal setting were the commitment to, and ownership of, the goals. Overall, if athletes took ownership of their goals, and remained committed and accountable throughout the process, goal setting was considered successful. Participants associated a positive attitude toward goal setting with successful experiences, but a negative attitude (e.g., lack of accountability, lack of motivation to monitor progress) was linked to unsuccessful experiences.

Collaboration and autonomy

Collaborating with a client and providing them autonomy when setting goals were associated with successful goal-setting experiences. Interview participant 5 identified the importance of taking into consideration the wants of a client during any needs analysis, noting the need to “be open to what they think they need and then also be observant and giving them some things that I see that they may be able to benefit from.” In some cases, collaboration was not only between the SPP and client, but also the coach. Engaging with a coach during goal setting could lead to clarity around the needs of the athlete:

The coaches are your reality check because, you know, an athlete may say to me, “I can do this outcome” and the coach is like “well, no, no, no, they can’t really do it yet”… So I love to bring the coaches in and that’s a really soft piece for athletes to go to a coach with. (Interview participant 14)

She said, ‘well, I would have to talk to this coach and see what we come up with.’ And I thought please, this is brilliant like that, that’s a great idea. And then she came back with a couple of, you know, ideas and. And I know for a fact she talked to him and said, hey, we need to find something to think about, to work on, which is obviously, you know, honey for a coach. (Interview participant 2)

I also want to stress it’s always what the athlete wants. It’s never what I want. It’s not effective like everyone has different definitions of success, and it’s not my job to judge who’s like what your definition of success is. It really is like if they’re totally invested in their goals, then yeah, I'm just the facilitator and they’re doing all the work. So ideally, they should be able to go set on their own eventually. (Interview participant 11)

Setting appropriate goals

Participants felt the types of goals that clients set could determine if goal setting was successful or unsuccessful. Many factors related to setting appropriate goals were identified. These factors included setting goals based on the needs analysis and client preferences; in multiple areas (e.g., sport and life); that could be monitored and measured; and that were controllable and challenging. Interview participant 7 mentioned the importance of understanding client preferences:

What I'm learning is there are some clients that love to have goals to follow along to, that really just keeps them on track. They like to know they’re making progress. There’s other ones that it feels a little bit stuffy.

With elite athletes, their purpose is not grounded in one singular sentence. It’s often a cluster of different component pieces, because there’s things that they understand they can’t have 100% control over. But, they want to have touch points in all of these various realms, and it’s, you know, their social media presence or their branding. It’s things around their training and pushing their bodies and relationships that they have.

Another factor related to the types of goals and, more specifically, their adjustability, was mentioned by Interview participant 4. Understanding how sensitive goals are to the dynamic and ever-changing environment was described as an important consideration: “We’re not setting good goals because we’re not like bringing in what’s happening in the environment, we get injured, or we are changing it [the environment]. Are we continuing and making it challenging?” The need to remain flexible and to adapt to the different challenges and obstacles that can arise in an athletic journey was considered key by this participant.

Some factors related to setting goals were identified as causes of unsuccessful goal-setting experiences. These included setting too many goals, goals that were unrealistic, or ones that placed focus on the outcome. Some participants also suggested that their unsuccessful experiences could be due to poor decision making, specifically when they had used goal setting just because it was an evidence-based intervention: “feeling like I have to go there [goal setting] because it’s a good technique. It’s a good mental skill to have only to realize that it wasn’t needed, it wasn’t what the athlete truly wanted or needed now (Interview participant 2).” As pointed out in this quote, using goal setting because it has been shown to be an effective intervention may not have been beneficial for the client as it did not address their needs.

Reflecting, tracking, and monitoring progress

Reflecting, tracking and monitoring the progress of a client after a period of goal striving was a factor identified to play an important step in the goal-setting process. Many successful goal-setting experiences discussed by SPPs included tracking and monitoring a client’s progress toward a goal in a follow-up session:

What isn’t stressed enough in the literature and also in the education, I guess, is the monitoring of it and the following up on it. What we said in the beginning is that if you just set goals in the beginning, it’s good in the beginning for the atmosphere and for the cohesion. If you’re looking for and also for maybe motivation. But if you don’t monitor them, it’s basically a waste of time in the end. Because, you know, the likelihood of the goal is coming true are very small if you don’t monitor it. (Interview participant 10)

Tracking and monitoring progress allowed clients to evaluate any progress they had made and reflect on any barriers or obstacles stopping them from achieving their goals. Participants realized the time and space given to clients for tracking and monitoring progress was important and not reflecting could lead to numerous unwanted outcomes:

I think this goes with this accountability piece to make sure that it’s actually still helping them and not hurting them, because I can see this other side of goal setting if we’re not checking in or if we’re setting like these expectations and things change. That leads to burnout. That leads to maybe injury or like more of like these negative outcomes that we don’t want. (Interview participant 4)

Discussion

This research offers insight into how SPPs conduct goal setting in applied sport psychology practice and is, to the best of our knowledge, the first study to explore such processes within sport psychology. Through our analysis, we identified that three types of factors influence SPP’s use of goal setting: client factors, contextual factors; and practitioner factors. The findings show there are a set of separate but interrelated steps that practitioners may consider using throughout the goal-setting process. Expected outcomes of goal setting were categorized into positive psychological outcomes, positive performance and progress outcomes, and negative outcomes. Lastly, we developed four categories related to successful and unsuccessful goal-setting experiences. Together, the findings from the current study complement and extend the extant understanding of goal setting in sport and can be used to inform applied suggestions for SPPs when implementing goal setting.

Learning about the application of knowledge and skills by SPPs in applied practice and how to overcome challenges faced in real-world practice is important for the professional development of SPPs (Hutter et al., Citation2015). By exploring the lived experiences of SPPs’ use of goal setting, our findings build on previous professional practice perspectives on goal setting in sport (see Bird et al., Citation2024 for a review) by generating novel insights into how client factors, contextual factors, and practitioner factors influence SPPs’ use of goal setting and how these factors can underpin successful goal-setting experiences. Researchers writing about context-driven practice (CDP; see Schinke & Stambulova, Citation2017 for an overview) have implied that sport psychology interventions should be individually tailored to the client (client factor) and driven by the context (contextual factor) where the intervention occurs. Our findings offered initial evidence, specific to goal setting, illustrating how client and contextual factors (e.g., individual differences of a client and sport environment) influence the use of goal setting with an individual to ensure that the intervention is sensitized to client and context. Furthermore, our findings show how practitioner factors may influence how different steps in the goal-setting process are delivered. For example, SPPs who consult from contrasting philosophical perspectives implemented the vision, values, and/or purpose step of the goal setting process in different ways that aligned with their chosen philosophy (e.g., an SPP with an existential philosophy focused on uncovering a client’s purpose in life). Taken together, our findings highlight the role of professional judgment and decision-making expertise (Smith et al., Citation2019) when using goal setting in practice and suggests SPPs should consider the who (i.e., client), when/where (i.e., context), and why (i.e., practitioner approach) before using goal setting.

When reporting how they set goals, participants in this study identified many steps that occurred before, during, and after any goals were set. When compared to previously suggested goal-setting processes (e.g., Symonds & Tapps, Citation2016), participants identified similar steps, such as conducting a needs analysis, identifying strategies that help goal attainment, and revising/adjusting a goal. However, we also established additional and novel considerations for SPPs that have not been commonly discussed in the goal-setting literature. For example, generally educating a client on all steps in the goal-setting process was mentioned. Stages related to education when implementing an intervention are hallmarks of psychological skills training and have been evident since early research in this area (e.g., Daw & Burton, Citation1994). Many existing goal-setting processes posed by researchers and practitioners have focused on specific education, like teaching athletes about different goal-setting principles (see Bird et al., Citation2024 for a review), and do not consider educating clients about other steps within the process (e.g., how to monitor and track progress). Based on the current findings, SPPs might consider how to educate athletes on all steps in the process of goal setting to help them acquire the skill of setting a goal. When setting goals in practice, the current findings also illustrate the contingent-dependent nature of implementing some steps. For example, specific education on goal setting might only be considered if clients are new to setting goals, or if they have been unsuccessful in their previous goal pursuits. As with previous research (e.g., Bird et al., Citation2024), findings from our study show steps should be regarded as fluid and likely to change dependent on with whom and where a practitioner is working. Findings from our study, therefore, resonate with research on the professional development of SPPs (Fogaça et al., Citation2024) by highlighting the importance being adaptable in the use of goal-setting knowledge and the application of this intervention in a flexible rather than rigid, ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach.

Expected outcomes from goal setting included positive psychological outcomes, positive performance and progress outcomes, and negative outcomes. Meta-analytic evidence shows goals have a positive effect on performance (Kyllo & Landers, Citation1995; Williamson et al., Citation2022) and there is consensus that goal setting to be a valuable skill within psychological training approaches (e.g., Diment et al., Citation2020). There is also some (albeit limited) evidence to support positive psychological effects of goal setting for enjoyment, self-confidence, motivation, and effort (Williamson et al., Citation2022). Despite this general support for goal setting, findings from this study begin to highlight potential detrimental effects of setting goals, with some SPPs noting negative outcomes associated with this intervention. Researchers have previously shown that outcome goals, for example, might be associated with increased cognitive anxiety compared to self-referenced goals (Williamson et al., Citation2022). Increased stress appraisals, anxiety, and an unwanted focus on the outcome were perceived to arise because of goal setting by some participants in this study. SPPs should therefore be aware of the potential negative consequences of setting goals with clients. In addition, although participants in this study stated they may use goal setting as it was part of their approach, or because they acknowledge it as an evidence-based practice, it was noted that using goal setting just because it was backed by evidence may be detrimental to the client (and client-practitioner relationship) if it was selected inappropriately.

Knowing about an intervention alone does not determine how it is delivered or the client’s use of it. Active ingredients (e.g., essential components), such as qualities of the practitioner (e.g., empathy), can help clients benefit from their interactions with a SPP (Tod et al., Citation2019). Findings from our study offer a set of active ingredients (e.g., essential components) that apply specifically to successful and unsuccessful experiences of goal setting. Active ingredients identified related to the attitude of the client toward goal setting; collaboration and autonomy between practitioner and client when setting goals; making sure goals are appropriate for the client; and reflecting, tracking, and monitoring progress. Findings concerning the importance of attitude in the current study resonate with propositions within the multidimensional model of sport psychology service provision (M2SP2: Martin et al., Citation2012), which highlighted the role of client attitudes and their relationship with future intentions, behaviors, and satisfaction with services. Furthermore, attitudinal variables like openness (or readiness, as noted in findings of the current study) have been associated with willingness to seek sport psychology support (Zakrajsek et al., Citation2011). Given the emphasis placed on the attitude of the client toward goal setting by participants, nurturing a positive client attitude toward goal setting before and during the goal-setting process would seem valuable.

Collaboration and autonomy throughout the goal-setting process, and setting appropriate goals with clients, also contributed to successful experiences. Aligned with previous literature, collaborative goal setting, defined in health settings as the process where health care professionals and patients agree on health outcomes (Bodenheimer & Handley, Citation2009), has been shown to have numerous benefits. Improving client participation (e.g., an active role the goal-setting process; Wressle et al., Citation2002) and fostering independent task management (Foley, Citation1998) are positive outcomes of this collaborative practice. Moreover, drawing upon the self-concordance model (Sheldon & Elliot, Citation1999), setting goals that are personally relevant and valued by the client can provide benefits associated with autonomous goal motives, such as increased goal persistence, higher positive affect, and enhanced future task engagement (Ntoumanis et al., Citation2014). Collaborative goal-setting has been shown to be an important consideration for sport coaches when setting goals with athletes (Weinberg et al., Citation2001), but there is little research on how SPPs maintain a collaborative approach when goal setting with clients. Ensuring the goals of the client were appropriate was another key to success. Consideration of the many principles of goal setting, like goal proximity, goal difficulty, and goal type, are evident in past interventions (e.g., McCarthy et al., Citation2010). When setting goals with athletes, our findings suggest that SPPs may wish to consider the views and perspectives of the client due to the many benefits associated with collaborative goal setting and goals with autonomous motives, but at the same time also ensuring the goals of the client are appropriate.

One final aspect to successful and unsuccessful goal-setting experiences involved reflecting, tracking, and monitoring progress. While these processes can be undertaken in many ways, one method used by participants to do this was using feedback. Theoretically, feedback is an important moderator in the relationship between goal setting and performance according to goal-setting theory (Locke & Latham, Citation2006). Feedback prompts evaluation of progress made toward a goal and guides subsequent strategies for future goal striving. Making sure clients gain feedback as they strive toward their goals should be something SPPs provide or help clients receive (e.g., based on measurement strategies). Engaging in reflection was another prominent ingredient to success. Reflection serves three functions; (a) self-explanation; (b) data verification; and (c) performance and task feedback (Ellis et al., Citation2014). Moreover, it can be used to help a client understand what worked well or not so well in relation to recent performance. Reflecting enhances underlying principles to optimal performance such as self-awareness and self-regulation (Kirschenbaum, Citation1997). As self-regulation can help clients manage their own behaviors, SPPs might consider utilizing reflection throughout the goal-setting process to promote autonomous monitoring, evaluations of progress, and goal adjustment.

Limitations and future directions

Findings from this study should not be interpreted without considering its limitations. Firstly, findings from this study show a composite conceptual model of the goal-setting process based on the responses of all participants’ online survey and interview data. Although the model shows the general steps involved in setting goals, variation exists when cases are analyzed individually. Variation would be expected as SPPs reported practicing from various philosophical perspectives, within numerous contexts, and with different clients, but when presenting data collectively, the specific details or nuances that occurred when setting goals from different perspectives was not focused upon. Future goal-setting research could benefit from a case study approach, allowing a more in-depth exploration of the goal-setting process, based on practitioner philosophy, to be undertaken. Secondly, most participants in this study held (or were working toward) accreditation/certification from a governing body in North America (i.e., AASP or CSPA), suggesting most resided and worked in the United States of America or Canada. Findings of this study therefore might not resonate with those providing sport and exercise psychology support elsewhere (e.g., Asia, Africa). As researchers have written about the importance of exploring unique cultural standpoints (e.g., cultural sport psychology; Schinke et al., Citation2019) for applied practice and research purposes, future investigations on goal setting should look to consider participants from wider cultural and contextual backgrounds.

Applied implications

In the current study, we have provided novel insights into the complexities and nuances of goal setting based on the lived experiences of SPPs. Our findings help address a need for research into the experiences of SPPs delivering goal setting and can be used to support the professional development and educational needs of those wishing to implement goal setting more effectively in their practice. There are several important applied implications for practitioners related to how SPPs may conduct goal setting based on findings from this study. Firstly, our findings highlight the many stages and steps that might be considered when setting goals with clients in applied practice and show the importance of generally educating clients on all steps in the process, not just the step of setting goals, so they can set goals autonomously. Secondly, our findings provide insight into influences (e.g., client factors, contextual factors, and practitioner factors) that may determine the individual nature of goal setting, and how the implementation of each process should consider the importance of context-driven practice and the professional judgment and decision making of the SPP. Thirdly, our findings identify active ingredients that contribute to successful goal-setting experiences, such as making sure the client is ready to set goals, collaborating with the client to facilitate the process and providing the client autonomy to set their own goals, setting goals that are appropriate for the client, and following up after goals have been set by reflecting, tracking, and monitoring progress.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to understand how goal setting is used by SPPs in applied practice. To this end, we identified what factors influenced SPP’s use of goal setting, how SPPs set goals with clients, what outcomes SPPs expected from setting goals, and what SPPs perceive contributes to successful and unsuccessful experiences of goal setting. Our findings make a novel contribution to the existing goal-setting literature in sport psychology by showing the influence of client, contextual, and practitioner factors on how goals are set; the multiple stages and steps practitioners undertake when setting goals; the intended uses of goal setting by SPPs (including important considerations on how goal setting can be detrimental to clients); and important active ingredients that contribute to a successful goal-setting process. Overall, findings from this study should encourage SPPs to consider the complexities and nuances of this intervention by recognizing how the process of goal setting goes above and beyond simply setting a goal.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bell, A. F., Knight, C. J., Lovett, V. E., & Shearer, C. (2022). Understanding elite youth athletes’ knowledge and perceptions of sport psychology. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 34(1), 155–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2020.1719556

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Boulton, E., Davey, L., & McEvoy, C. (2021). The online survey as a qualitative research tool. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 24(6), 641–654. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2020.1805550

- Bird, M. D., Swann, C., & Jackman, P. C. (2024). The what, why, and how of goal setting: A review of the goal-setting process in applied sport psychology practice. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 36(1), 75–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2023.2185699

- Bodenheimer, T., & Handley, M. A. (2009). Goal-setting for behavior change in primary care: An exploration and status report. Patient Education and Counseling, 76(2), 174–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.06.001

- Burton, D. (1989). Winning isn’t everything: Examining the impact of performance goals on collegiate swimmers’ cognitions and performance. The Sport Psychologist, 3(2), 105–132. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.3.2.105

- Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage.

- Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage.

- Daw, J., & Burton, D. (1994). Evaluation of a comprehensive psychological skills training program for collegiate tennis players. The Sport Psychologist, 8(1), 37–57. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.8.1.37

- Diment, G., Henriksen, K., & Larsen, C. H. (2020). Team Denmark’s sport psychology professional philosophy 2.0. Scandinavian Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 2, 26–32. https://doi.org/10.7146/sjsep.v2i0.115660

- Dwyer, S. C., & Buckle, J. L. (2009). The space between: On being an insider-outsider in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(1), 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690900800105

- Ellis, S., Carette, B., Anseel, F., & Lievens, F. (2014). Systematic reflection: Implications for learning from failures and successes. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(1), 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721413504106

- Fogaça, J. L., Quartiroli, A., & Wagstaff, C. (2024). Professional development of sport psychology practitioners: From systematic review to a model of development. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 70, 102550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2023.102550

- Foley, A. (1998). A review of goal planning in the rehabilitation of the spinal cord injured person. Journal of Orthopaedic Nursing, 2(3), 148–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1361-3111(98)80030-7

- Gillham, A., & Weiler, D. (2013). Goal setting with a college soccer team: What went right, and less-than-right. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 4(2), 97–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2013.764560

- Hutter, R. V., Oldenhof-Veldman, T., & Oudejans, R. R. (2015). What trainee sport psychologists want to learn in supervision. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 16, 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.08.003

- Jeong, Y. H., Healy, L. C., & McEwan, D. (2023). The application of goal setting theory to goal setting interventions in sport: A systematic review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 16(1), 474–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2021.1901298

- Kirschenbaum, D. (1997). Mind matters: 7 steps to smarter sport performance. Cooper Publishing.

- Kyllo, L. B., & Landers, D. M. (1995). Goal setting in sport and exercise: A research synthesis to resolve the controversy. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 17(2), 117–137. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.17.2.117

- Lochbaum, M., & Gottardy, J. (2015). A meta-analytic review of the approach-avoidance achievement goals and performance relationships in the sport psychology literature. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 4(2), 164–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2013.12.004

- Lochbaum, M., Stoner, E., Hefner, T., Cooper, S., Lane, A. M., & Terry, P. C. (2022). Sport psychology and performance meta-analyses: A systematic review of the literature. PloS One, 17(2), e0263408. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263408

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2006). New directions in goal-setting theory. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(5), 265–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00449.x

- Maitland, A., & Gervis, M. (2010). Goal-setting in youth football. Are coaches missing an opportunity? Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy, 15(4), 323–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408980903413461

- Maykut, P., & Morehouse, R. (2002). Beginning qualitative research: A philosophical and practical guide. Routledge.

- Martin, S. B., Zakrajsek, R. A., & Wrisberg, C. A. (2012). Attitudes toward sport psychology and seeking assistance: Key factors and a proposed model. In C. D. Hogan & M. I. Hodges (Eds.), Psychology of attitudes (pp. 1–33). Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

- McCarthy, P. J., Jones, M. V., Harwood, C. G., & Davenport, L. (2010). Using goal setting to enhance positive affect among junior multievent athletes. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 4(1), 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.4.1.53

- Ntoumanis, N., Healy, L. C., Sedikides, C., Duda, J., Stewart, B., Smith, A., & Bond, J. (2014). When the going gets tough: The “why” of goal striving matters. Journal of Personality, 82(3), 225–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12047

- Poczwardowski, A. (2019). Deconstructing sport and performance psychology consultant: Expert, person, performer, and self-regulator. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 17(5), 427–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2017.1390484

- Schinke, R. J., Blodgett, A. T., Ryba, T. V., Kao, S. F., & Middleton, T. R. F. (2019). Cultural sport psychology as a pathway to advances in identity and settlement research to practice. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 42, 58–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.09.004

- Schinke, R. J., & Stambulova, N. (2017). Context-driven sport and exercise psychology practice: Widening our lens beyond the athlete. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 8(2), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2017.1299470

- Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice. Sage.

- Sheldon, K. M., & Elliot, A. J. (1999). Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: The self-concordance model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(3), 482–497. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.3.482

- Smith, M., McEwan, H. E., Tod, D., & Martindale, A. (2019). UK Trainee sport and exercise psychologists’ perspectives on developing professional judgement and decision-making expertise during training. The Sport Psychologist, 33(4), 334–343. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2018-0112

- Smith, B., & McGannon, K. R. (2018). Developing rigor in qualitative research: Problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(1), 101–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357

- Smith, B., & Sparkes, A. C. (2016). Interviews: Qualitative interviewing in the sport and exercise sciences. In B. Smith & A. C. Sparkes (Eds.), Routledge handbook of qualitative research methods in sport and exercise (pp. 103–123). Routledge.

- Sparkes, A. C., & Smith, B. (2014). Qualitative research methods in sport, exercise and health. Routledge.

- Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research. Sage.

- Symonds, M. L., & Tapps, T. (2016). Goal-prioritization for teachers, coaches, and students: A developmental model. Strategies, 29(3), 34–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/08924562.2016.1159155

- Tod, D., Hardy, J., Lavallee, D., Eubank, M., & Ronkainen, N. (2019). Practitioners’ narratives regarding active ingredients in service delivery: Collaboration-based problem solving. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 43, 350–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.04.009

- Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837–851. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410383121

- Wanlin, C. M., Hrycaiko, D. W., Martin, G. L., & Mahon, M. (1997). The effects of a goal-setting package on the performance of speed skaters. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 9(2), 212–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413209708406483

- Weinberg, R., Butt, J., Knight, B., & Perritt, N. (2001). Collegiate coaches’ perceptions of their goal-setting practices: A qualitative investigation. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 13(4), 374–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/104132001753226256

- Widmeyer, W. N., & Ducharme, K. (1997). Team building through team goal setting. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 9(1), 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413209708415386

- Williamson, O., Swann, C., Bennett, K. J., Bird, M. D., Goddard, S. G., Schweickle, M. J., & Jackman, P. C. (2022). The performance and psychological effects of goal setting in sport: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1–29. (Advanced online publication). https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2022.2116723

- Wressle, E., Eeg-Olofsson, A. M., Marcusson, J., & Henriksson, C. (2002). Improved client participation in the rehabilitation process using a client-centred goal formulation structure. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 34(1), 5–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/165019702317242640

- Zakrajsek, R. A., Martin, S. B., & Zizzi, S. J. (2011). American high school football coaches’ attitudes toward sport psychology consultation and intentions to use sport psychology services. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 6(3), 461–478. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.6.3.461