ABSTRACT

This narrative scoping review examines ethical practice in educational and school psychology from a bioecological systems’ perspective. A search of four databases yielded 34 articles in the final narrative synthesis. Informed by Bronfenbrenner and Morris’ bioecological systems theory, the ethical experiences of educational and school psychologists were analyzed using the concepts of Process, Person, Context and Time. The complexity, intensity and frequency of ethical dilemmas are reviewed in Process. The demand, resource, and force characteristics impacting on psychologists as Person are reviewed. Within Context, studies identified dilemmas that arose for psychologists across systems. In Time, issues including implications of the Fourth Industrial Revolution on psychologists’ ethical practice with the emergence of Artificial Intelligence are examined. This paper demonstrates the synergies and the interrelated influences on psychologists’ ethical practices arising from a systematic review of their experiences and their professional training needs.

A BIOECOLOGICAL SYSTEMS REVIEW OF ETHICAL PRACTICE

Rapid changes in how we work and live are affected by a growing dominance of neoliberalism and the challenge it engenders for educational and school psychologists. According to Rouf (Citation2015), psychologists have a responsibility to confront inappropriate and inequitable practices by working within cultures and systems. However, this practice can impact on their ability to deliver “ethically sound psychological services” (Rouf, Citation2015, p. 94). Psychologists who work with children and young people are particularly vulnerable to ethically challenging events they may encounter in their work (Maki et al., Citation2022). Psychologists have a professional and ethical responsibility to maintain the highest standards in their profession outlined in codes of practice and conduct (American Psychological Association, Citation2017; British Psychological Society, Citation2018). In the United States, the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP, Citation2020) also has an ethical code that informs professional standards, principles, and practices to support school psychologists. These codes are bifunctional by providing a guide for psychologists and simultaneously protecting the public from inappropriate conduct carried out by them (NASP, Citation2020; Maki et al. Citation2022). A key tenet to working as a professional is to engage in ethical behavior, which, from an applied psychology perspective, requires psychologists to work scientifically and objectively in their role (Woody, Citation2011). Ethics codes should underscore the fundamental moral tenets of ethical working in a profession, including, to do good, do no harm, respect others, and treat individuals in an honest and fair manner (Fisher, Citation2023).

Ethical leadership in educational and school psychology

Internationally, educational and school psychologists’ roles are synonymous and are continuously evolving to meet the increasingly complex environments within which they work. These psychologists require a vast knowledge, and an extensive array of skills and competencies in areas such as child development, understanding schools as organizational systems, and being cognizant of the impact of culture and community on student engagement (Booker, Citation2021). Hardy et al. (Citation2020) acknowledge that ethical practice is of central importance to educational psychologists particularly in reflecting on, and revisiting, their applied practice on an ongoing basis. They recognize the plethora of presumptions regarding psychologists’ ways of ethical working “that remain unexamined and out of kilter with what we would want to achieve” (Hardy et al., Citation2020, p. 5). Midgen (Citation2015) identified key individual and contextual factors contributing to ethical and unethical leadership in educational psychology that include “the moral character of leaders, the culture values of society and organizations, the ethical interests of stakeholders both inside and outside an organization, and the ethical behavior of the peer group and systems for dealing with unethical conduct” (p. 81). Despite the challenges that can arise in practice, Winston (Citation2007) suggests that organizations which exhibited the most ethical track record were also the most successful. Fisher (Citation2023) states that a profession that displays its ability to self-monitor is less vulnerable to external regulatory demands.

Psychologists have a responsibility to demonstrate ethical leadership in education, and ethical practice enables them to make a significant and positive impact on the lives of the children and young people with whom they work. To facilitate this positive impact, Midgen and Theodoratou (Citation2020) advise that leadership in educational psychology takes the time to pause and reflect on ethical dilemmas arising in practice, and take responsibility for ensuring the best use of public resources in their decision-making. In business contexts, Winston (Citation2007) highlighted that individuals overestimated their ethical decision-making abilities, by underestimating the impact of their biases, particularly in relation to managerial decision-making in organizational contexts. This is also of relevance to psychologists’ ethical practices in leadership roles.

Responsible ethical leadership in educational and school psychology involves continuous reflective practice on problem formulation to address the impact of multiple interpretations of events that can arise. Moreover, moral leadership and moral practice are intertwined and a distinction cannot be made between who psychologists are and their values, beliefs, will and capacity to empathize with others (Midgen & Theodoratou, Citation2020). Brown et al. (Citation2005) define ethical leadership as comprising of two dimensions, namely the moral person and the moral manager. A moral person is defined as a person who is honest, fair, principled, and caring. A moral manager acts as a paragon of ethical behavior in the work place and leads by example. Midgen (Citation2015) warns of the impact of ethical failure that risks the reputation and trust of an organization. Cunliffe (Citation2009) suggests that ethical leaders develop as philosopher leaders to enable them to think more critically and reflectively about themselves, their actions, and the contexts within which they work. Furthermore, a philosophical understanding of leadership enables thinking and understanding from multiple perspectives (Cunliffe, Citation2009), a core skill required in educational and school psychology. The study of ethics enables ethical leaders to support diversity in school systems, particularly to address complexities that can arise as a result of ethical dilemmas (Shapiro & Stefkovich, Citation2022). To enable psychologists to work at this level requires systemic thinking. The aim of an ethical psychology service is to ensure that an effective systems level approach is implemented to enable schools to meet their students’ educational and psychological needs (Maki et al., Citation2022). Psychologists have a responsibility to practice reflexivity and self-reflexivity to guide their leadership. Moreover, leadership in educational psychology involves the promotion of self-care to ensure the psychological safety and wellbeing of team members. This also includes facilitating adequate supervision. According to Midgen and Theodoratou (Citation2020), a reflexive and self-reflective thinking space enables psychologists to engage in systemic thinking to contain the challenging aspects of their practice to facilitate accountability and sound ethical decision-making. Elder-Vass (Citation2019) suggests that, as humans, we have the reflexivity to shape our own values.

Given the importance of professional ethics, the challenges of inferential practices, and the systems work that psychologists employ, an exploration of ethical issues that arise for educational and school psychologists, from a systems perspective, is warranted. A narrative scoping methodology (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005) guided a systematic examination of the ethical experiences of these psychologists informed by bioecological theory (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Citation2006) to review ethical concerns that arise in applied practice. The rationale for selecting this framework was its usefulness as an approach to map the impact of psychologists’ roles and behavior to the contexts within which they work using a systemic lens. This approach reflects the complex interplay of systems and multiple interpretations of events that can affect ethical practice. The theoretical underpinning of this theory is outlined in more detail below.

In professional developmental contexts, bioecological theory is recognized as a useful tool for analyzing and explaining the forces that impact on human development at each level (Christensen, Citation2016). For psychologists who work in schools, this requires an understanding of the interactions that occur and shape a system which enables them to implement successful cultural change processes. For example, Shapiro and Stefkovich (Citation2022) identified a moral imperative to develop and foster more democratic and inclusive schools. Research has outlined the importance of thinking at a systems level to facilitate effective inclusion of all students (Kinsella & Senior, Citation2008), and the function of professional ethics is to guide this work (Gajewski, Citation2017). It is recognized that psychologists are the only consistent school-based personnel working from a systemic lens who facilitate the implementation of psychological practice to better contextualize their role in supporting students (Burns et al., Citation2015). To advance the profession at a time that is witnessing significant change, there is merit in examining the impact of these changes on psychologists’ ethical experiences from a systems perspective to guide ethical leadership, and to identify psychologists’ professional training needs.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The bioecological theory of human development (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Citation2006) was applied to synthesize the literature identified in this review of ethical practice in educational and school psychology. This section provides an overview of this approach to theoretically frame this narrative scoping review.

Bioecological theory of human development

Bronfenbrenner and Morris’s (Citation2006) bioecological theory of human development is one of the most influential and widely used theoretical frameworks that examines human development within ecological contexts (Navarro et al., Citation2022; Tong & An, Citation2024; Watling Neal & Neal, Citation2013). This theory informs our understanding of how human development is influenced by the interplay of four key concepts of process, person, context and time (PPCT). Ambitious in scope, the complexity of using PPCT as a paradigm to conduct research is acknowledged (Tong & An, Citation2024). Additionally, Bronfenbrenner (Citation1988) recognized the challenge for researchers in examining all four components concurrently. Navarro et al. (Citation2022) recommend that all four components are thoroughly examined when applying bioecological theory and PPCT to research, at a minimum. However, a review conducted in school psychology, identified a dearth in research examining all four components (Burns et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, recent studies acknowledge that the four concepts of PPCT have been inadequately addressed in research (Tang & An, Citation2024; Navarro et al., Citation2022). Additionally, interpreting and implementing the PPCT as a whole is a challenge (Navarro et al., Citation2022). To redress this concern, Navarro et al. (Citation2022) offer guidance on operationalizing PPCT as a heuristic (please see Navarro et al., Citation2022, p. 240, for further details). This paper presents an application of PPCT to inform a narrative scoping review of ethical practice in educational and school psychology.

Table 1. Context, themes and subthemes of studies included.

Proximal processes

Proximal processes, also referred to as Process in PPCT, are recognized as the “engines of development” (Bronfenbrenner, Citation2001, p. 6967) and affect person characteristics, as a concept in PPCT, in a number of ways. Specifically, proximal processes are required to promote development that include assumptions about how individuals interact with people and their environment, and in instances where these interactions become progressively more complex over time. It is acknowledged that these interactions must occur over an extended period to become effective (Navarro et al., Citation2022). From an ethical practice perspective, it is important for psychologists to build positive and sustainable interactions in the multitude of contexts within which they work to enable them to be effective in their role (NASP, Citation2020). To analyze this component thoroughly in psychological research requires an examination of three constructs within proximal processes that include the reciprocity between a developing psychologist and those with whom they interact, the increasing complexity of this role over time, and the duration and frequency of these processes over time (Navarro et al., Citation2022).

Person characteristics

For person characteristics, the PPCT model advises that three constructs are examined including the developing person of interest (the psychologist), their personal characteristics, and the outcome of his or her development (Navarro et al., Citation2022). A person’s characteristics, including their personal and professional experiences, impact on how an individual engages with, and in, their environment (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Citation2006). These characteristics are particularly salient in supporting the development of psychologists’ ethical practice in educational and school psychology. According to Navarro et al. (Citation2022), person characteristics are examined as input and output in the PPCT model. Specifically, input person characteristics precede proximal processes and person characteristics are an outcome of the synergy that it creates among person and context over time.

Bronfenbrenner and Morris (Citation1998) make reference to three types of person characteristics, namely, force, resource, and demand. Force characteristics refer to dynamic personality traits that can facilitate or hinder proximal processes. Traits conducive to development were defined as developmentally generative or developmentally disruptive. For psychologists, developmentally generative traits may include a natural curiosity in people (NASP, Citation2020), thinking systemically (Burns et al., Citation2015; Kapoulitsas & Corcoran, Citation2017; Mendes et al., Citation2016), self-efficacy (Guiney et al., Citation2014; Lockwood et al., Citation2017), and adhering to sound ethical practices (Fisher, Citation2023). Conversely, psychologists who are developmentally disruptive may present with characteristics and behaviors that include difficulties they encounter in managing caseloads (Schilling et al., Citation2018), engaging in ethically dubious practices (Dailor & Jacob, Citation2011; Maki et al., Citation2022), and struggling to maintain professional and personal boundaries that can impact negatively on their ethical practice (Goforth et al., Citation2017; Louvar Reeves & Brock, Citation2018; Perfect & Morris, Citation2011). Resource characteristics are defined as experiential, mental, or biological resources that individuals use to drive proximal processes (Xia et al., Citation2020). For psychologists, these characteristics comprise of sources of biological, psychological, and social information psychologists gather on a client as part of an assessment process, and triangulation of this information to formulate a treatment plan. Demand characteristics refer to tangible factors that promote or impede individuals from interactions they can experience in their environment (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Citation2006). For example, psychologists can experience burnout as an outcome of administrative pressures resulting from unethical requests. Many educational systems provide equitable access to education for learners. However, demand characteristics have the potential to impact on additional supports that learners may need, arising from a student’s interaction with a psychologist. For example, higher-income families typically have the resources to pay for private psychological assessments which impact on equity in how diagnoses are obtained, and the subsequent resources that can be accessed as a result (Harrison, Citation2022). Psychologists recognize the significant role of the environment and how it affects, positively or negatively, on a developing child (Burns et al., Citation2015).

Context

The importance of a person’s environment or context was central to Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1979) theory from the start. For psychologists, an ecological approach examines development in the context of the environments in which a student functions including the environments of home, school and community (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1988). Context is examined from the interactions that occur between four levels, frequently illustrated as nested circles, which include the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem and macrosystem, all of which influence human development (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Citation2006). According to Bronfenbrenner (Citation1979), the microsystem refers to the setting that has a direct impact on individuals’ development including their direct experiences, social roles, and interpersonal relationships. For psychologists, this includes the direct impact on their experiences of professional working environments. The mesosystem level captures the interplay, linkages, and processes between two or more contexts in which a developing person actively participates (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979). For a psychologist, this level includes interactions with children, young people, families, peers, et al. with whom they engage. The exosystem level includes contexts impacting on the developing person but where they do not directly participate. For educational and school psychologists, this can include events that affect psychologists’ ethical practices for which they do not have a direct role. For example, this may involve policy that impacts on their work. Bronfenbrenner (Citation1979) described the macrosystem level as the societal context within which an individual resides. This level relates to members of a particular socio-cultural group who share a sense of identity, beliefs, values, practices, and access to resources, etc. (Xia et al., Citation2020). At this level, the attitudes and ideologies of a culture can have an ethical impact on psychologists’ practices.

Time

Finally, this theory also conceptualizes the impact of the component time at three levels: microtime (experiences that occur during proximal processes, examining duration); mesotime (human experiences that occur over longer time periods, examining frequency); and macrotime (experiences that occur over lengthy time periods, including experiences over generations, acknowledging historical contexts within which data was gathered) (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Citation2006). Initially, time was conceived as macrotime in the chronosystem as part of Bronfenbrenner’s original model. He initially proposed that macrotime was a “change or consistency over time not only in the characteristics of the person but also of the environment in which the person lives” (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1994, p. 40). Two additional levels, microtime and mesotime, were subsequently included in the updated PPCT (Tong & An, Citation2024). For psychologists, microtime includes observations, activities, etc., that occur at a specific moment. In mesotime, psychologists are interested in the developmental impact on a person of activities and interactions that occur with consistency in their environment. For example, psychologists engage in macrotime when examining developmental changes that occur in a person or in their environment. For educational and school psychologists, research on the longitudinal changes in ethical practice, and revisions made to codes of practice and professional standards could be examined in the component time as a developmental component.

Navarro et al. (Citation2022) suggest that studies examine how the integration and interrelation of all PPCT components influence development. It is essential for psychologists to be aware of how systemic changes influence the services they provide, and the impact of their decisions on the children, young people, schools, and communities they serve (Rouf, Citation2015). Despite the recognized impact of this theory in school psychology literature (Burns et al., Citation2015), translating it into empirical approaches has, thus far, proven to be elusive (Koller et al., Citation2020; Navarro et al., Citation2022; Watling Neal & Neal, Citation2013). Additionally, Navarro et al. (Citation2022) highlighted the challenges in interpreting and implementing the PPCT model in research. For example, a review on the application of PPCT in school psychology identified that only four out of 25 articles used at least three out of its four key concepts (Tudge et al., Citation2009). Research suggests that ecological theory could enhance practice for psychologists by promoting systems level working to systemically address concerns that arise in schools (Burns et al., Citation2015). This suggests that PPCT, as a conceptual framework, is a theoretically robust approach to systematically review the development of psychologists’ ethical practices.

METHOD

For the purposes of this review, studies examining the ethical practices of educational and school psychologists were analyzed to identify the synergies and interrelated influences of PPCT on psychologists’ experiences of ethical practice from a bioecological theoretical perspective. This study seeks to operationalize PPCT by applying these four components to a review on ethical practice in educational and school psychology. This process was guided by Arksey and O’Malley’s (Citation2005) five stage narrative review methodology and used PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyzes extension for Scoping Reviews) guidelines (Tricco et al., Citation2018). The research objectives, informed by and mapped to Arksey and O’Malley’s (Citation2005) five stage process, are as follows:

To formulate the research questions (Framework Stage 1);

To identify literature from peer-reviewed papers that included philosophical exercises examining ethical practice in educational and school psychology, specific to papers that were philosophical exercises and/or focused on commentaries, etc. on ethical practice that would not meet criteria for inclusion from robust meta-analysis or meta-synthesis review processes (Framework Stages 2–4);

To synthesize the literature on ethical practice in educational and school psychology, mapped to the four conceptual headings of Process, Person, Context and Time (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Citation2006) (Framework Stage 5).

Critical realism and ethical practice

This narrative review on psychologists’ ethical practice was informed by a critical realist epistemology. Proposed by Bhaskar (Citation2008), critical realism recognizes the value of context, processes, and adaptability to particular situations reflecting a common-sense approach to any investigation (Pilgrim, Citation2020). Bhaskar makes the distinction between empirical, actual, and real domains, analogous to experiences, events, and causal mechanisms that connect an experience to an event for psychologists (Booker, Citation2021). Specifically, this examination recognizes that ethical knowledge and decision-making is informed by evidence (the empirical), psychologists’ prior experiences of ethical and unethical events (the actual event), and their moral compass, ethical code, and fiduciary responsibilities that all guide professional practice (the causal mechanisms). The application of a narrative scoping review methodology supports critical realism’s claims as an open system that is ontologically maximally inclusive by including diverse literature on a topic using a laminated approach. A laminated system refers to distinct levels in social and physical systems that need to be considered when giving a comprehensive explanation of events, which is closely aligned to PPCT (O’Mahoney & Vincent, Citation2014). This approach adopts Sayer’s (Citation2011) view of critical realism as a “congenial philosophical partner in social science” and was particularly applicable to a review on ethical practice from a systems perspective (p. 14). Prendeville and Kinsella (Citation2022) reframe ethical practice within critical realism by presenting Fulford’s (Citation2008) Values Based Practice (VBP) as an approach that could supports educational psychologists in addressing the complexities and diversity they encounter in their work, particularly to navigate ethical tensions that may arise as a result. They propose that VBP could support these psychologists to reflect on their values, facilitating an application of shared decision-making practices (National Institute of Clinical Excellence, Citation2021) to embed a child’s rights approach in ethical practice. A VBP approach could support psychologists to engage with an open (laminated) system that acknowledges diversity in viewpoints, methodologies, and realities reflecting integrative pluralism (Bhaskar & Danermark, Citation2006) to address the complexities of the real world within which psychologists work. Integrative pluralism is promoted in critical realism by examining a wide range of research methodologies. This is facilitated in this paper by using a narrative scoping review to examine psychologists’ ethical experiences captured from a wide range of sources using a broad range of methodologies.

Framework stage 1: identifying the research question

In response to the first research objective, and informed by a critical realist paradigm, the following research questions were addressed in this review:

Can ecological systems theory inform a review of ethical practice in educational and school psychology?

What do we know about ethical practice in educational and school psychology?

Using PPCT as a framework, what are the systemic and interrelated factors impacting on educational and school psychologists’ ethical practice?

The second research objective is addressed in framework stages 2 to 4 outlined below.

Framework stage 2: identifying relevant studies

In this section, the search strategy and inclusion and exclusion criteria applied in this study to identify literature in response to the research questions, are outlined below.

Search strategy

In February 2023, a search of four databases was completed that included Education Resources Information Centre (ERIC), CINAHL, Web of Science and Psychinfo (Proquest). An extensive gray literature search was also conducted. Searches targeted publications on ethical practice between January 1, 2009 to January 31, 2023. An additional gray literature search was conducted in December 2023 to identify publications on the impact of generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) on educational systems to identify the potential ethical issues that could arise for psychologists in response to comments raised during the review process in relation to this paper.

Eligibility criteria

Eligibility for inclusion included peer-reviewed articles published in English that focused on articles, commentaries, and philosophical exercises specific to ethical practice in educational and school psychology, including perspectives on ethical concerns arising from the emergence of generative AI systems in education. This review was particularly interested in capturing literature on ethical practice from non-empirical studies that would not meet the criteria for a robust meta-analysis. The rationale for this approach was to facilitate the inclusion of papers and commentaries that were published as philosophical exercises interrogating professional ethics. The inclusion of these papers provided a valuable perspective, and whose absence would have diminished the richness afforded to a discussion on ethical practice in educational and school psychology.

Stage 3 and stage 4: study selection and charting the data

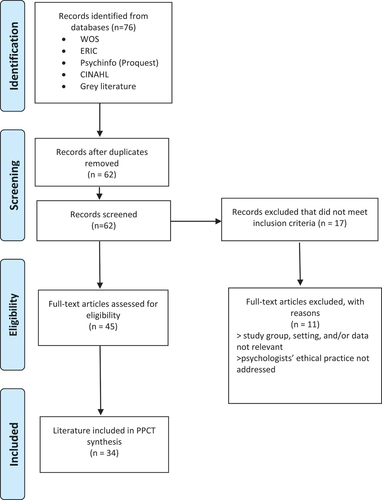

This scoping review was completed using the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al., Citation2018) to identify papers for selection, analysis and review. An initial search yielded a total of 76 articles that were assessed for eligibility. Following the removal of duplicate articles and records that did not meet the inclusion criteria, a total of 34 articles were included in the final review. titled “PRISMA flow diagram” details the process that was applied.

, titled “Context, themes and subthemes of studies included” charts the studies that were identified and mapped to PPCT.

RESULTS

To address the third objective in this narrative review, the literature was synthesized to the four conceptual headings of Process, Person, Context and Time (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Citation2006) in bioecological theory. Navarro et al. (Citation2022) provide a practical guide to support researchers to address the dearth in studies that apply the PPCT model. They provide guidance to accurately operationalize PPCT in research and this was used to analyze research on ethical practice in educational and school psychology. Notably, there is an imbalance in studies examining the four concepts of PPCT, consistent with recent research that explored eight studies on human development demonstrating the practical application of this theory (Navarro et al., Citation2022).

Stage 5: collating, summarizing and reporting the results

In the final stage of Arksey and O’Malley’s (Citation2005) narrative review methodology, the ethical practice concerns that arose for psychologists with respect to their ethical experiencesin the systems within which they work are reviewed. Additionally, the potential impact of generative AI systems for psychologists’ future ethical practices are explored.

Proximal processes

Bronfenbrenner (Citation2001, p. 6967) identified proximal processes, also referenced as Process in the PPCT, as the “engines of development.” He proposed that these processes were influenced by three constructs, namely, reciprocity, increasing complexity, and duration and frequency (Navarro et al., Citation2022). Literature that identified the impact of these constructs on ethical practice in educational and school psychology is examined in this section. Reviewed studies identified the increasing complexity that arose in ethical practice in educational psychology over time that enabled psychologists to become more competent in their roles. There is an expectation that psychologists develop to become ethical leaders over the course of their professional careers and work at senior or management levels to provide supervision and support to novices and less experienced psychologists. Studies also identified the reciprocity challenges psychologists experience in navigating dual relationships (Louvar Reeves & Brock, Citation2018; Mahoney & Morris, Citation2012; Perfect & Morris, Citation2011) and includes the impact of digital dual relationships (Diamond & Whalen, Citation2019; Pham, Citation2014) and telehealth (Edwards & Sullivan, Citation2014) where psychologists experience blurring of boundaries and expectations. Psychologists are spending more time engaging in therapeutic practices online which present with ethical ramifications that have not been fully explored (Pham, Citation2014).

The duration and frequency of ethical challenges that arose in navigating interactions with others were reportedly more prevalent in rural working contexts (Osborn, Citation2012). Psychologists experienced isolation, role confusion, and burnout as a result of working in these contexts (Edwards & Sullivan, Citation2014). Psychologists experienced reciprocal ethical challenges when working in collectivist cultures where their own cultural reference point and training context is based on individualistic perspectives and experiences. Specifically, Louvar Reeves and Brock (Citation2018) emphasized the importance for psychologists to situate themselves culturally and to apply their clinical competencies in a way that was culturally harmonious to the context in which they worked. In these contexts, working with overlapping approaches was considered the most ethical way of working to ensure the best outcomes for clients (Louvar Reeves & Brock, Citation2018; Sewell & Hulusi, Citation2016). A reviewed study called for guidelines on social justice ethics in psychology that include reflecting critically on relational power dynamics, focussing energy and resources on priorities of marginalized communities, and raising awareness of systems’ impacts on community wellbeing (Hailes et al., Citation2021). Johnson et al. highlighted (Citation2019) psychologists’ challenges in applying culturally competent practices even when those competencies are recognized as ethically sound and informed by best practice. Studies have identified the importance for psychologists to engage in self-care, particularly with ethical challenges that occur as a result of practicing while impaired (Mahoney & Morris, Citation2012). The duration and frequency of ethical dilemmas that psychologists experience also overlap with Time as a concept. In the next section, within the conceptual heading of person characteristics, literature was examined under three constructs, persons of interest, antecedent person characteristics, and outcome person characteristics.

Person characteristics

Educational and school psychologists were the developing persons of interest and focus of this review. Their practices across jurisdictional boundaries were reviewed including studies from the United Kingdom (Sewell & Hulusi, Citation2016), the United States (Mayworm & Sharkey, Citation2014) and New Zealand (Bourke & Dharan, Citation2015). The antecedent person characteristics acknowledged the underlying assumption that psychologists were ethical in their practices and encountered contexts and experiences that challenged their ethical practice. A range of antecedent variables were identified from a view of studies including ethical experiences and work contexts, examined in much greater depth in the Context. For example, studies explored the impact of their digital behavior and the public’s perceptions of educational and school psychologists as representatives of the psychology profession (Pham, Citation2014). The outcome person characteristic identified areas where psychologists require supports to enable them to further develop and enhance their ethical skills as an outcome variable of this review. Psychologists’ professional training needs in the area of ethical practice, identified from this review, are outlined in the discussion section.

Context

Bronfenbrenner (Citation1979) outlined the essential role and influence of context on the developing person arising from their interactions across the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem levels. In , studies that identified the ethical impact on educational and school psychologists were thematically mapped to each system. This table illustrates the interrelated factors of each system and their impact on psychologists’ ethical practice.

Microsystem

At the microsystem level, where an educational or school psychologist works in a professional role, there were a number of ethical concerns identified in the literature. Psychologists have a professional and moral obligation to work within their areas of competency. However, at this level, there are times when this is tested when engaging with colleagues. Ethical dilemmas were identified from assessment practices employed by educational and school psychologists. For example, in New Zealand, Bourke and Dharan (Citation2015) found that psychologists struggled ethically when they moved from engaging solely in psychometric assessments to consultancy led working, particularly when there was an expectation on them to be more diagnostic in their practice. In a context where there was no longer a requirement to engage in assessments for special educational needs (SEN) support or funding allocations, this change has resulted in debates on the “role” and “value” of psychologists, impacting on their practice. Ethical issues also emerged regarding psychologists’ lack of professional competencies to engage in assessment practices to identify learning disability (Dombrowski & Gischlar, Citation2014). In this study, dilemmas arose for school psychologists due to a lack of a consistent and accurate approach to assessment particularly with an increasing move away from the discrepancy model in diagnosing learning disabilities and special educational needs. Dilemmas were also identified with regard to the disproportionate impact of psychologists’ decision-making on students with intersectional needs including those from minority and lower socio-economic backgrounds. Psychologists have an ethical duty to conduct assessments using evidence-based practices and scientific decision-making when identifying individuals with SEN (Sadeh & Sullivan, Citation2017).

In the United States, Mayworm and Sharkey (Citation2014) explored the complex and controversial issues that emerged from a response to intervention tiered approach to assessments to inform school discipline decision-making. Specifically, controversies arose in relation to specific methods employed by schools to address disciplinary concerns, where psychologists had a role to play in ensuring that appropriate ethical standards were employed, and also to resolve dilemmas when standards were challenged by poor practices. Ethical issues can arise regarding the professional competencies required to ensure that psychologists adhere to culturally appropriate assessment practices (Harris et al., Citation2015), including assessments to support decision-making for clients with mental health difficulties (Perfect & Morris, Citation2011). Ethical concerns were identified regarding poorly facilitated informed consent practices used by educational psychologists (Louvar Reeves & Brock, Citation2018; Perfect & Morris, Citation2011; Stein & Sharkey, Citation2015).

Psychologists have an obligation to engage ethically in culturally and linguistically responsive practices. Reviewed studies identified that educational psychologists were ill-equipped to engage in such practice and shortcomings were identified in the literature (Harris et al., Citation2015). Gaps in sound professional competencies in the assessment of English language learners revealed that research and resources available in this area were limited (Harris et al., Citation2015). There was a call for a change in assessment practices to ensure that educational and school psychologists engaged in culturally responsive practices (Bourke & Dharan, Citation2015; Goforth et al., Citation2017). Ethical issues identified included psychologists’ lack of access to culturally appropriate assessment tools used in bicultural environments (Bourke & Dharan, Citation2015). Additionally, concerns were highlighted about the importance of establishing and maintaining culturally harmonious working practices with clients in collectivist cultures (Louvar Reeves & Brock, Citation2018). Specifically, psychologists can experience ethical difficulties engaging in culturally competent practices as these may challenge ethically sound best practice guidelines that were initially developed for psychologists practicing in individualistic contexts (Johnson et al., Citation2019). This can lead to a lack of professional autonomy for psychologists, particularly in situations that can result in ethical constraints or dilemmas arising from assessment instruments that were used (Bourke & Dharan, Citation2015).

Notably there were concerns raised regarding educational and school psychologists who have practiced while impaired (Edwards & Sullivan, Citation2014; Mahoney & Morris, Citation2012). Ethical challenges identified included a psychologist’s diminished ability to perform their role (Mahoney & Morris, Citation2012). Edwards and Sullivan (Citation2014) suggest that this is particularly salient for psychologists working in rural contexts where there are increasing pressures to practice, leading to professional distress as a result of an impairment. This paper also highlighted issues of overextension and burnout arising for psychologists in these settings.

Educational psychologists have encountered administrative pressures to act unethically (Helton & Ray, Citation2009; Perfect & Morris, Citation2011). Perfect and Morris (Citation2011) identified ethical issues educational psychologists encountered in meeting the needs of children with mental health difficulties. Psychologists also experienced ethical dilemmas as a result of administrative pressures where there was an expectation on them to respond to these pressures to protect their job, and a belief that it would be futile to resist this pressure (Helton & Ray, Citation2009).

Mesosystem

In the mesosystem, psychologists experienced ethical challenges with multiple and dual relationships where their professional roles were blurred and professional boundaries challenged (Goforth et al., Citation2017; Mahoney & Morris, Citation2012; Perfect & Morris, Citation2011). Dilemmas can arise for psychologists in navigating professional contexts where disparate views of those present can result in ethically compromising scenarios. Concerns were highlighted in the literature about the increase in digital working contexts (Pham, Citation2014), and the challenges psychologists experienced in navigating multiple relationship roles online (Demers & Sullivan, Citation2016). This has become more salient in recent times due to ethical concerns that were exacerbated as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (Khoo & Lantos, Citation2020; Maki et al., Citation2022). Psychologists were faced with difficulties in technological work spaces (Lasser et al., Citation2013), including the management of data security (Demers & Sullivan, Citation2016) and telehealth (Maki et al., Citation2022). Moreover, psychologists need to be mindful of digital working particularly with the potential impact of bias, for example, social media requests from clients (Demers & Sullivan, Citation2016). Psychologists are required to maintain their technological competencies to avoid risks that could emerge as a result (Pham, Citation2014). It is necessary for psychologists to monitor their personal and professional behavior to ensure that it does not ethically impact on their professional responsibilities (Diamond & Whalen, Citation2019). The impact of advances in technology requires psychologists to be vigilant as there were ethical pitfalls to incompetent social media usage identified from both psychologists’ and clients’ perspectives (Demers & Sullivan, Citation2016).

Managing bias is core to ethical practice and psychologists are required to act with integrity including being consistent in their actions including clear and unbiased decision-making (British Psychological Society, Citation2018). Sadeh and Sullivan (Citation2017) advised educational psychologists to safeguard against biases in decision-making and when they were addressing errors that arose from ambiguous interpretations. Psychologists have a professional and ethical responsibility to protect their clients including professional accountability for treatment plans devised for clients.

Ethical issues were identified for educational and school psychologists who have worked with clients on medication (Kubiszyn et al., Citation2012; Perfect & Morris, Citation2011; Roberts et al., Citation2009; Shahidullah, Citation2014). In some work contexts, psychologists interact with students on psychotropic medication to support students’ treatment and to engage in data-based decision-making, particularly in behavioral support contexts (Kubiszyn et al., Citation2012). However, there are legal and ethical considerations as psychologists working with these students require the competencies to meet this need (Roberts et al., Citation2009). Furthermore, psychologists’ involvement in school-based decision-making pertaining to the initiation of a child’s or a young person’s access to medication is unethical, and caution was advised when giving advice to parents (Shahidullah, Citation2014). In addition, psychologists were regularly faced with time constraints in managing the increasing demand for their services from others, while ensuring ethical working was core to their practice (Bowles et al., Citation2016).

Exosystem

In the exosystem, research identified ethical issues that arose for psychologists working in rural contexts (Edwards & Sullivan, Citation2014; Goforth et al., Citation2017; Louvar Reeves & Brock, Citation2018; Osborn, Citation2012; Schank et al., Citation2010). Working in rural settings was an identified challenge for educational and school psychologists (Louvar Reeves & Brock, Citation2018; Osborn, Citation2012). Ethical issues they disclosed included the impact of a lack of resources, a high staff turnover, difficulties filling psychology positions, maintaining confidentiality, and supporting greater mental health needs arising for clients who live in these areas, which challenged psychologists to engage effectively and ethically in their role (Goforth et al., Citation2017). Due to the reported higher visibility of working in rural settings, psychologists experienced a lack of privacy and overlap in their professional and personal boundaries also (Louvar Reeves & Brock, Citation2018). Edwards and Sullivan (Citation2014) suggested that psychologists needed to be particularly vigilant about establishing and maintaining clear communication to avoid their roles becoming blurred. Further ethical concerns reported in rural settings included isolation and burnout among psychologists (Edwards & Sullivan, Citation2014).

Psychologists’ professional practice in the exosystem appeared to be impacted by the concept person characteristics which hindered proximal processes. For example, the literature suggests that psychologists could display developmentally disruptive traits in struggling to manage large caseloads in rural contexts, and may be impacted by the potential challenges to their boundaries of practice that could emerge as a result. Additionally, this review suggests that the demand characteristics of cultural factors may also impact on some psychologists who work in rural contexts. Specifically, a psychologist’s individualistic cultural reference point could deter their application of sound ethical practices when working in collectivist work contexts (Johnson et al., Citation2019). This was also highlighted in the microsystem, demonstrating the overlap and synergy that can arise in applying a bioecological framework to a narrative scoping review. There is a call for further research and training that addresses these ethical dilemmas of concern to psychologists who work in rural contexts (Goforth et al., Citation2017).

Macrosystem

In the macrosystem, research identified the need for educational psychologists to consider context specific ethical working (Lasser et al., Citation2013; Louvar Reeves & Brock, Citation2018; Sewell & Hulusi, Citation2016). Lasser et al. (Citation2013) advised educational psychologists to adopt a context-specific approach to working meaningfully and ethically in schools. Psychologists can be faced with challenging decisions where situational sensitivity is required. Specifically, these psychologists may need to employ a context-specific ethical approach that considers standards along with situational variables, values, and contextual factors. Xia et al. (Citation2020) highlighted that individuals were likely to engage in multiple cultural contexts, for example, their professional roles, their access to racial/ethnic groups, their service priorities, etc. resulting in their access to, or barriers to accessing, various resources. Consequently, there was overlap identified in resource under the construct person characteristics in the PPCT model. For example, Louvar Reeves and Brock (Citation2018) highlighted the ethical challenges psychologists face when working in collectivist cultural contexts where individualist perspectives on roles, values, and decisions were rejected. The tensions and sensitivities to working as a psychologist in these settings may heighten the risk of ethical dilemmas occurring, thus impacting on professional practice. From an applied ethical perspective, this reflected a communitarianism philosophy which rejected individualistic decision-making approaches (Hedgecoe, Citation2004). In this context, psychologists are required to work systemically to address overlapping relationships that arise to enable them to engage therapeutically with clients. Ethical issues can emerge that include managing potential bias and addressing blurring of professional boundaries psychologists experience when working in these contexts. For example, Sewell and Hulusi (Citation2016) provided a very interesting and informative view to assist psychologists in applying contextual ethics when working with radicalized youth in the United Kingdom. They highlighted the unique and specific ethical tensions that arose for educational psychologists when working with this marginalized group.

The ethical use of technology and social media impact on the contexts within which psychologist work also. Psychologists are now working in a digital age (Pham, Citation2014), a time of rapid technological change, and codes are not revised frequently enough to address all the ethical issues that can emerge relating to digital working. The research identified an increase in ethical dilemmas arising in professional practices in this area (Demers & Sullivan, Citation2016; Diamond & Whalen, Citation2019; Pham, Citation2014) due to the widespread use of social media among psychologists. A psychologist’s personal information shared online could jeopardize their professional relationships with clients (Demers & Sullivan, Citation2016). It is essential that psychologists are knowledgeable about the potential benefits and risks associated with its use. There is a dearth in the research that examines the social media habits of psychologists (Demers & Sullivan, Citation2016), and this warrants further investigation. Potential ethical issues include inadvertent self-disclosure, unintended use of personal information, managing social media requests, and searching for information of clients online without their explicit informed consent (Demers & Sullivan, Citation2016). King and Rings (Citation2022) examined the ethical and legal challenges for psychologists when faced with disclosures of adolescent sexting. Ethical dilemmas in protecting the confidentiality of clients and balancing this with regard to clients’ access to pornography were identified. This was recognized as significantly problematic in instances with minors with respect to a psychologist’s legal obligation as a mandatory reporter (King & Rings, Citation2022). It is essential that psychologists outline their fiduciary responsibilities during informed consent processes with clients. King and Rings (Citation2022) also advised that educational supports for psychologists should be targeted at the macro level with clear guidelines for psychologists who work with children and young people. Hardy et al. (Citation2020) identified positives to working ethically in the macrosystem including the development of systems in psychological practice to improve leadership and development by harnessing technology to facilitate online forums to communicate with colleagues nationally or internationally.

Time

Under the conceptual heading of time, Bronfenbrenner and Morris (Citation2006) identified three constructs of microtime, mesotime and macrotime. For psychologists, the immediate ethical concerns that arise on a regular basis would feature in microtime. Ethical issues that happen on a more infrequent basis occur in mesotime. Whereas, macrotime encompasses the changing view on ethical practice over a psychologist’s professional career. The concept of time was not evident in many studies identified in this review which suggests that a longitudinal examination of ethical practice in educational and school psychology would be beneficial to identify how psychologists develop their ethicality over time. Two studies based in the United States examining the ethical practices of school psychologists provide a snapshot of ethical practice at two moments in time. Maki et al. (Citation2022) (n = 240) revisited ethically challenging situations experienced by school psychologists following a similar study that was completed 10 years prior by Dailor and Jacob (Citation2011) (n = 208). In the more recent study, fewer psychologists reported experiences of challenging ethical situations in their practice (Maki et al., Citation2022). The most prevalent issues involved ethical issues arising in the areas of assessment, administrative pressure, interventions, addressing parental conflict, confidentiality, informed consent, job competencies, and conflictual relationships. The previous study also reported that administrative pressure, unsound ethical practices in schools, and assessment-related issues were the most reported ethical dilemmas encountered by psychologists (Dailor & Jacob, Citation2011), indicating some changes in challenging ethical experiences that psychologists encountered over time. Notably, the more recent study identified that the ethical impact of telehealth for psychologists was the second most cited concern, where psychologists reported feeling relatively unprepared to address ethical dilemmas they were experiencing (Maki et al., Citation2022). Comparison of these findings on ethical practice from both studies reflect changes in the professional landscape for psychologists in macrotime. According to Bronfenbrenner (Citation1988), to determine if development has occurred, it was necessary to examine studies over a length of time. This can occur by engaging in longitudinal examinations that are dependent on the developmental outcome of interest. For example, future studies could examine how undergraduates in psychology develop their ethical thinking over the course of their studies, and likewise for psychologists on professional training programs.

Developments in psychology have evolved over time and some ethical practices deemed ethical at a particular time, and in a particular context, may be impacted by the socio-historical period in which they took place. There are many examples of practices in psychology that, at a later time, were acknowledged by the profession as unethical. A review of studies identified two main themes that reflected ethical concerns arising in macrotime under the component “Time” in PPCT. These themes included the potential impact of AI on ethical practice in educational and school psychology and the potential of social justice ethics to assist psychologists to address ethical concerns that may arise in the future. We are now living in a time period coined the Fourth Industrial Revolution (World Economic Forum, Citation2023) which is characterized by fundamental differences in how we now work and live. A technological revolution, as a result of advancements in AI (Bender et al., Citation2021), bioethics and neuroethics (Rahimzadeh et al., Citation2020), is impacting directly and indirectly on children and young people, thus affecting psychologists’ ethical practices and how their clients engage with the world around them. According to Childress-Beatty (Citation2023), Chief of Ethics in the APA, generative AI is proffered as a “game changer” that will revolutionize psychologists’ practice over time. The break-neck speed of this nascent technology holds promise; however, experts have issued stark warnings about the potential risks associated with rapid developments in AI (Timmons et al., Citation2023) over time, including its application to learning contexts (European Commission, Citation2022). These developments have led to an over-representation of the hegemonic lens and its associated biases which have perpetuated stereotypes resulting in the potential for propagating power imbalances and greater inequality in society over time (Bender et al., Citation2021). Research also warns that

work on synthetic human behavior is a bright line in ethical AI development, where downstream effects need to be understood and modelled in order to block foreseeable harm to society and different social groups.

According to Vincent-Lancrin and van der Vlies (Citation2020), the use of AI in education raises two significant issues that include ensuring that it is harnessed for the benefit of students, and using it safely so that it prepares students to develop new skills in an increasingly automated society. There is a concern that AI will perpetuate bias due its use of historical data sets and algorithmic bias, thus creating legacy issues that may differentially impact on clients over time. Research suggests that ethical models used by psychologists to navigate ethically murky terrain are becoming less fit for purpose as a result (Lasser et al., Citation2013). It is important that psychologists anticipate risks that could arise in the use of AI, which includes safeguarding against any potential harm. As our access to knowledge increases and the speed of technological development further accelerates, it will be ethically incumbent on psychologists to keep abreast of these advancements, to harness them positively, and to examine them critically and ethically.

An expert group on AI and data in education advised that ethical guidelines in this area will be “an incremental process of continuous deliberation and learning” (European Commission, Citation2022), suggesting the importance of interrogating ethical concerns on an ongoing basis in macrotime (p. 17). Psychologists need to be vigilant in their endorsement and application of AI in practice due to the impact of the law of unintended consequences. Vincent-Lancrin and van der Vlies (Citation2020) suggest that AI has the potential to transform education, particularly in reaching Sustainable Development Goal 4, to promote inclusive and equitable educational systems globally. Landers and Behrend (Citation2023) define a fair AI system as one which promotes human flourishing with shared human values, defined by a sense of care, core to psychological working. It is a given that AI will become pervasive in education (Vincent-Lancrin & van der Vlies, Citation2020).

The crucial and unique role of educational and school psychologists to systemically examine the ethical impact of technology in learning environments in macrotime, informed by social justice, is one of great potential to progress toward a more inclusive society. This may include personalized learning plans, devised in microtime, and tailored digitized supports for students with special educational needs to enable them to access adaptive learning environments that respond specifically to their needs in mesotime. Assessment of learners’ skills using digital platforms could provide much quicker response times than traditional assessment methods typically used by psychologists. The role of psychologists will be paramount in assuring transparency and accountability of assessment results to inform ethical decision-making. Notwithstanding the benefits, there are ethical challenges that will likely arise from such advancements including ethical issues that question the trustworthiness of AI, and an ethical duty to ensure that the use of AI protects personal data in promoting human centered values (Vincent-Lancrin & van der Vlies, Citation2020). For psychologists, this includes the promotion of a social justice, rights-based approach that places student voice at the center of any decision-making using informed consent and informed assent processes, aligned to Article 12 (United Nations, Citation1989). Additionally, there are warnings of the impact of platformization, privatization and datafication of education on teachers’ and schools’ pedagogical autonomy (Andronikidis, Citation2023; Kerssens & van Dijck, Citation2022). Andronikidis (Citation2023) highlighted concerns about surveillance pedagogy with the implementation of tracking technology in school systems. To address this, the Ethical Compass was developed in the Netherlands as an online tool to assist teachers and schools to gauge the value-based implementation of digital technologies (Kerssens & van Dijck, Citation2022). Additionally, the European Commission (Citation2022) published guidelines on the use of AI and data in teaching and learning that could assist psychologists when consulting with schools. These guidelines advise that “ethical AI” is promoted to “ensure compliance with ethical norms, ethical principles, and related core values” (European Commission, Citation2022, p. 11). Four key ethical considerations are outlined in these guidelines that include human agency, fairness, humanity and justified choice.

DISCUSSION

This narrative scoping review provides a bioecological systemic examination of ethical practice in educational and school psychology at a time that has witnessed unprecedented and rapid changes in work contexts, and in the profession as a whole. Studies have highlighted the impact of these changes on psychologists’ ethical experiences from a bioecological systems perspective to guide ethical leadership, and to identify psychologists’ professional training needs. It is essential that psychologists remain committed to ethical principles and ethical decision-making approaches to guide responsible conduct in psychological science and applied practice (Fisher, Citation2023).

Ethical experiences

The ethical experiences of educational and school psychologists are multifaceted and complex due to a range of systemic interactive factors that impact on them in their professional roles. These studies illustrated how psychologists’ ethical experiences were influenced by a wide range of factors embedded within interacting systems that mutually and simultaneously influenced each other. The complex interplay of these systems, and multiple interpretations of events, impacted ethical practice for these psychologists in a number of ways. These included challenges in assessment practices (Bourke & Dharan, Citation2015; Mayworm & Sharkey, Citation2014; Sadeh & Sullivan, Citation2017), ethical issues in diagnosing special educational needs (Dombrowski & Gischlar, Citation2014), and concerns that arose when supporting clients with mental health issues (Perfect & Morris, Citation2011). This review also revealed how the wellbeing and ethical practices of psychologists were affected as an outcome of practicing while impaired (Edwards & Sullivan, Citation2014; Mahoney & Morris, Citation2012). Psychologists working exclusively in rural environments experienced isolation and burnout which affected their ability to engage in acceptable ethical behavior (Edwards & Sullivan, Citation2014). This included managing bias in these settings (Sadeh & Sullivan, Citation2017). It is important that psychologists are vigilant and act as beacons to promote the highest standards of ethical practice in their work.

Promoting ethical leadership

As educational and school psychologists are recognized as the only consistent school-based personnel working from a systemic lens to enhance students’ experiences in schools (Burns et al., Citation2015), it is important that leadership recognizes the challenges psychologists face and supports them to navigate these challenges in the workplace. This review highlighted the requirement for ethical practice to be promoted at a leadership level and modeled at all levels in a psychological service. It is important to foster consistency in implementing sound ethical practice, guided by practice-based and evidence-informed processes and procedures. In the promotion of good ethical governance, it is necessary that a transparent process exists to tackle unethical conduct in educational and school psychology. This process needs to promote a balanced approach that addresses concerns arising from impaired practices, and exercises reasonable steps to protect a psychologist who experiences these issues. Midgen (Citation2015) identified contextual factors that contribute to ethical leadership that incorporated how an organization dealt with unethical conduct. Accordingly, it is important that ethical leadership promotes behavior congruent in acting as a moral person and a moral manager and, thus, lead by example (Brown et al., Citation2005). Leadership has a duty of care to psychologists, arising from ethical challenges, as an outcome of practicing while impaired. To imbue a positive approach to ethical leadership, this review identified the necessity to take the time to reflect on ethical tensions when they occur (Midgen & Theodoratou, Citation2020). The findings also reinforce the important role of leadership in promoting self-care, and ensuring the psychological safety and wellbeing of team members. For leadership who support psychologists working exclusively in rural contexts over a prolonged period, a number of specific issues arose that included the need to address ethical concerns arising from administrative pressures, the impacts of managing large caseloads, and the importance of addressing sensitivities in ethically informed cultural practices. It is important for psychologists to have access to adequate supervision as required. Additionally, the significance of embedding social justice ethics to assist in ethical decision-making that prioritizes the intersectional needs of marginalized communities was also identified (Hailes et al., Citation2021).

Professional training needs

An outcome person characteristic of this review identified priority professional training needs for educational and school psychologists. This review revealed that psychologists require supports to develop cultural competencies to address ethical concerns that occur due to practicing in unfamiliar cultural contexts. Psychologists would benefit from training supports to meet the needs of culturally diverse populations to enable them to develop clinical competencies in cultural formulation (Louvar Reeves & Brock, Citation2018). Psychologists’ training requirements to work ethically in digital contexts, including practices around the use of social media, advising on the use of generative AI systems to support learners, and addressing ethical concerns arising from adolescent sexting, were also highlighted (Andronikidis, Citation2023; Demers & Sullivan, Citation2016; Diamond & Whalen, Citation2019; King & Rings, Citation2022). Professional development supports that promote the use of ethical models to address ethical concerns when they arise were also identified (Lasser et al., Citation2013). Psychologists would benefit from accessing bias training that includes the effective use of ethical decision-making in schools.

From the praxis of social justice ethics, Hailes et al. (Citation2021) advise that psychologists work creatively and flexibly to address ethical dilemmas that arise in educational systems by empowering clients from marginalized communities through consciousness-raising. Writing prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Osbeck (Citation2019) was prescient in her call to examine psychology to address the unprecedented trials facing humankind, and the ambiguous changes ahead. She explored the conceptual and ethical implications of the terms “persons” and “personhood” given their historical and contextual uses with regard to societal privilege. Osbeck reexamined epistemic priorities in psychology and how it will address the challenges and opportunities for human impact placing values as central. This view will require further interrogation in the context of developments in AI in macrotime, its impact on educational systems, and the evolving role of psychologists in the promotion of ethical practices in schools. A proposal to embed value sensitive design, that includes identifying values, and designing systems to support these values, would mitigate the potential harm of such advances (Bender et al., Citation2021). Therefore, it will be important for psychologists to develop their role as philosopher leaders (Cunliffe, Citation2009), and embed values-based practices (Fulford, Citation2008), to inform this work. This role and these practices could guide an examination of rapid changes using a bioecological approach with the aim of progressing the development of a more inclusive and human-centered future (World Economic Forum).

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study to demonstrate the utility of reviewing the ethical practices of educational and school psychologists from a robust theoretical base, using PPCT as a framework (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Citation2006). This review identified some persistent areas of ethical concern for psychologists, and their professional learning needs. Embedding a systems approach to this narrative scoping review was a novel approach that captured the richness not afforded by an application of other review methodologies. This approach was particularly salient to this investigation on ethical practice as it required the reflexivity to identify, map, and examine ethical issues from a philosophical perspective. This study also provides signposting to potential ethical concerns that are likely to emerge in the profession with the acceleration of generative AI in educational systems. The application of a bioecological approach captured a more reflective perspective on psychologists’ ethical practices. Additionally, an examination of the four concepts of PPCT demonstrated synergistically and simultaneously (Tong & An, Citation2024; Xia et al., Citation2020) the developmental outcomes of psychologists’ ethical practice, informed by a critical realist, laminated approach. This paper suggests that the PPCT model could be used as a heuristic to examine ethical practices in other professions.

Notwithstanding the benefits, this paper also highlighted the significant dearth of research in this area, particularly with regard to developments in psychologists’ ethical practices over time and variations in their ethical practices in different jurisdictions. The limited locations of studies included in this review highlights the dearth of research on ethical practice in educational and school psychology internationally. Additionally, this review identified the dearth in studies informed by PPCT. Tudge et al. (Citation2009) advised that all elements should be present in studies when applying bioecological theory. However, if all elements are not clearly present, or cannot be analyzed, then this should be acknowledged by authors to preserve the integrity of an application of this model (Tudge et al., Citation2009). In this study, a significant dearth in longitudinal studies on psychological ethical practice was identified. Notably, the absence of a wide range of studies may also be due to inclusion criteria that only specified an examination of studies published in English.

This paper suggests that psychologists will continue to play an important and unique role in addressing ethical concerns that are likely to emerge due to the continued rapid systemic and technological changes in educational systems. Applying the PPCT framework was, at times, a challenge to use as it was not a linear process due to the overlap and synergy that occurred between concepts. Despite this challenge, this paper demonstrated how this model can positively mediate the interrelated influences that impact on the development of psychologists’ ethical practices over time.

Recommendations for future research

Xia et al. (Citation2020) identified that Brofenbrenner’s ecological transitions, as a concept, was largely neglected in studies. Bronfenbrenner defined transitions as changes in a person’s role and setting over time that may impact on a person’s care or development. Ecological transitions affect development across the concept of person, where transitions are normative or atypical, and this development is also influenced by the concepts of context and proximal processes. Future studies could explore transitions in psychologists’ ethical development over time using the PPCT as a heuristic. Additionally, studies have called for appropriate applications of PPCT model in research that uses all four concepts, particularly due to its identified inadequate adoption in studies to date (Navarro et al., Citation2022; Tong & An, Citation2024; Tudge et al., Citation2009).

Findings also suggest that there is a requirement to examine the ethical experiences of educational and school psychologists in greater depth to identify key issues that are arising in practice that include concerns in macrotime. This could include an examination of the effects of rapid advancements in generative AI, and its potential impact on educational systems, particularly in the promotion of equity in educational access and opportunity for diverse learners. Having an international perspective on ethical practice in educational and school psychology globally is pressing, given the potential challenges that could emerge in educational systems as a consequence. It would be helpful to gain a greater insight into ethical practice in educational and school psychology from collectivist cultures to advance priority professional training needs for psychologists in this area.

Research has highlighted the importance for psychologists to engage in professional development in ethics education throughout their careers and this requires further examination (Dailor & Jacob, Citation2011; Maki et al., Citation2022). Additionally, this paper identified the importance for psychologists to develop their ethical leadership. Examining an application of value-based practice (Fulford, Citation2008) could assist psychologists to further develop their ethical practice as a way of integrating values, rights, autonomy and evidence to inform professional practice (Prendeville & Kinsella, Citation2022). An application of a value-based practice approach has merit in creatively addressing ethical concerns that will continue to arise from advancements that include embedding value-sensitive design in generative AI systems. It would be beneficial to explore the systemic issues emerging for psychologists at more regular intervals to track the impact of technological changes on their work practices in macrotime and to identify the ethical issues that may emerge in learning contexts as a result. Psychologists’ professional training in ethics signals their essential role in continuing to support educational systems to examine ethically problematic practices when they arise.

CONCLUSION

It was the intention of this paper to explore how bioecological theory, using the PPCT as a conceptual framework, could be applied systematically to a narrative scoping review of ethical practices in educational and school psychology. While some concepts were examined in much greater depth than others, this paper demonstrates how this approach could support researchers to synthesize research on the impact of systems on the development of professional and ethical practices over time.

Data statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. APA.

- Andronikidis, K. (2023). Meaningful and ethical use of data in schools. In Data4Learning Webinar Series. Brussels, Belgium: European Schoolnet.

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Bender, E. M., Gebru, T., McMillan-Major, A., & Shmitchell, S. (2021). On the dangers of stochastic parrots: Can language models be too big? Conference on fairness, accountability, and transparency (FAccT ’21) (pp. 610–623). March 3–10, 2021 Virtual Event, Canada. New York, NY, USA, ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445922

- Bhaskar, R. (2008). A realist theory of science. Routledge.

- Bhaskar, R., & Danermark, B. (2006). Metatheory, interdisciplinarity and disability research: A critical realist perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 8(4), 278–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/15017410600914329

- Booker, R. (2021). A psychological perspective of agency and structure within critical realist theory: A specific application to the construct of self-efficacy. Journal of Critical Realism, 20(3), 239–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2021.1958281

- Bourke, R., & Dharan, V. (2015). Assessment practices of educational psychologists in Aotearoa/New Zealand: From diagnostic to dialogic ways of working. Educational Psychology in Practice, 31(4), 369–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2015.1070709

- Bowles, T., Scull, J., Hattie, J., Clinton, J., Larkins, G., Cicconi, V., Kumar, D., & Arnup, J. L. (2016). Conducting psychological assessments in schools: Adapting for converging skills and expanding knowledge. Issues in Educational Research, 26(1), 10–28.

- British Psychological Society. (2018). Code of ethics and conduct. BPS.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1988). Interacting systems in human development. Research paradigms: Present and future. In N. Bolger, A. Caspi, G. Downey, & M. Moorehouse (Eds.), Persons in context: Developmental processes (pp. 25–49). Cambridge University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). Ecological models of human development. In M. Gauvain & M. Cole (Eds.), International encyclopedia of education (pp. 37–43). New York, NY: Freeman.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (2001). The bioecological theory of human development. In N. J. Smelser & P. B. Baltes (Eds.), International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences (Vol. 10, pp. 6963–6970). Elsevier.

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (1998). The ecology of developmental processes. In W. Damon (Series Ed.) & R. M. Lerner (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development 5th (pp. 993–1028). John Wiley.