ABSTRACT

Purpose

This study investigates the justice perception of buying group member retailers and examines whether it is an initiator of relationships and a constant driver of attitude through the lens of brand equity and relationship duration. Building upon the findings, this study offers practical implications for the managers of the buying group headquarters.

Design/methodology/approach

A questionnaire survey of 241 key informants of retailers participating in eight different retail buying groups in Japan was conducted. We conducted confirmatory factor analysis to verify measurements, and structural equation modeling to test the hypotheses.

Findings

Distributive justice perception directly affected relationship duration and procedural justice perception had an indirect effect on relationship duration via brand equity. We also found the significant moderating effect of strategic integration. For the group with high strategic integration, distributive justice perception had a greater effect on brand equity, whereas, in the group with low strategic integration, brand equity was more affected by procedural justice perception. Furthermore, the roles of distributive justice perception and procedural justice perception were found to be complementary.

Research Implications

The study expands the perception of justice in an inter-organizational environment to a loosely connected channel structure while examining two endogenous variables of relationship performance (i.e. brand equity and relationship duration). This study also finds the moderating effect that justice perception has on relationship performance. By implementing strategic integration intention as a moderator, this study considers the strategic stance of member retailers in the research setting as well.

Practical Implications

The findings highlight that headquarter managers must understand the role of each sub-dimension of justice perception and balance their application. As the resources for building justice perception can be limited, it is important for managers to allocate resources based on prioritization.

Originality

This research is a pioneering study on the implementation of justice perception in the relationship between member retailers and buying groups. Additionally, it proposes and proves the conditions required for justice perception to induce a positive attitude on the part of member retailers.

Introduction

Developing a healthy and long-term relationship with retail buying groups (also known as voluntary chains) has proven to be a major success factor for independent small retailers, while presenting a formidable managerial challenge in the business-to-business (B2B) context (Ghisi et al. Citation2008; Kennedy Citation2016; Kim, Miao, and Hu Citation2022). Retailer buying groups are loosely and voluntarily connected collaborative and horizontal business associations that work together to conduct purchasing, logistics, and marketing campaigns. Small independent retailers may seek to join retail buying groups to achieve economies of scale and safeguard themselves from intense competition with larger local players and national retail chains (Geyskens, Gielens, and Wuyts Citation2015; Ghauri, Mazzarol, and Soutar Citation2021; Zentes and Swoboda Citation2000).

A practical example can be made of the Zennisshoku Chain that covers independent small supermarket retailers with one or two stores in Japan. Through vigorous joint activities, 1,615 retail stores (as of August 2021) that are members of the Zennisshoku Chain have obtained various advantages or benefits. These include a stable supply of well-known national brands, product differentiation through private brand, price competitiveness through centralized purchasing, efficient logistics management coupled with advanced information technology, and headquarters’ support for store operations and plausible marketing campaigns.

From the perspective of retail buying groups, various attractive benefits and services should be provided to induce the efforts to integrate individual small retailers who voluntarily participate (Hernández-Espallardo and Navarro-Bailón Citation2009; Kim, Miao, and Hu Citation2022). They can expect to adjust the level of participation according to the attractiveness of the benefit provided by the buying group. The unique role of the buying group is recognized as critical as individual small retailers are more vulnerable than large-scale retailers in allocating limited resources (Paruchuri, Baum, and Potere Citation2009). After evaluating the value of the buying group, small retailers decide whether to maintain the relationship with the buying group and make strategic integration efforts (Sandberg and Mena Citation2015). Therefore, the strategic integration intent of the individual retailers can be viewed as an indicator of the satisfaction that they get from such relationships, which is a crucial condition that the buying groups should pursue. In the evaluation process, individual small retailers consider two factors: fulfillment of their expectations and completion of a systematic transaction process with the buying group (Ghauri, Mazzarol, and Soutar Citation2021).

In addition, the performance of inter-organizational activities presupposes consistent integration between organizations (Li et al. Citation2021). However, it is difficult to develop synergy in a quasi-integrated organization and the literature offers many attempts to overcome this problem (Mason, Doyle, and Wong Citation2006). Among these attempts, the role of justice perceived by participating members has received persistent attention in academia and practice (Praxmarer-Carus, Sucky, and Durst Citation2013). Given that the problem of justice perception has its origin in individual-level problems within intra-organization problems, much research has been conducted by management studies scholars (Brown, Cobb, and Lusch Citation2006). A few of these argue that the level of organizational justice corresponds to the level of the fair environment within the organization perceived by the employees (Greenberg Citation1990). Such a perception of justice plays a key role in enhancing relationship performance regardless of the level of analysis. Additionally, the level of justice perceived by the other party enhances relationship quality (Kumar, Scheer, and Steenkamp Citation1995) in terms of knowledge sharing, relational investment (Liu et al. Citation2012), trust (Narasimhan, Narayanan, and Srinivasan Citation2013), and commitment (Zaefarian et al. Citation2016).

This perception of justice is also essential for retail buying groups in the B2B context. For example, in the case of the Zennisshoku Chain, since member retailers have similar demographic characteristics, they expect their buying group and headquarter to treat them equally. The collapse of such expectations is a critical cause of the member-retailer’s departure from the loosely connected inter-organizational relationship structure. As the extent and quality of such buying group benefits largely depend on member-retailers’ justice perception, inducing behaviors or mind-sets that increase justice perception progressively in the joint activities of the retail buying group is crucial. However, managerial guidance on how retail buying groups should handle justice concerns of their member retailers is lacking.

In this regard, early research on justice perception has provided valuable insights by expanding the scope of analysis from the individual employee level to the inter-organizational level (Kumar, Scheer, and Steenkamp Citation1995). Specifically, Bouazzaoui et al. (Citation2020) review study points out that research on inter-organizational justice perception has been limited but emphasizes that the studies of intra- and inter-organizational justice perception were treated in a similar manner (Colquitt et al. Citation2001; Lumineau and Oliveira Citation2018; Whitman et al. Citation2012). Justice perception plays a role in creating positive attitudes and behaviors with regard to relationships with other organizations that may be loosely connected. In B2B relationships, organizations ideally pursue a high level of solidarity with the other party (Barry et al. Citation2021), where most transaction participants exist in a loosely connected relationship. Since this structural state has the possibility to negatively affect the performance of inter-organizational relationships, efforts such as increasing the justice perception are considered essential to strengthen the relationship between organizations (Bouazzaoui et al. Citation2020).

Against this background, raising the justice perception of members can be equated to the ideal state of organization operation that retail buying groups can pursue. Therefore, the study of such justice perception contributes to both practically and academically, which our study covers in threefold. First, this study examines what the justice perception directly drives. In a loosely connected relationship, such as the transaction between a buying group and a small member retailer, it is important to remain a member by maintaining the relationship (Ghauri, Mazzarol, and Soutar Citation2021). Thus, it evaluates how long the relationship would last (Fink, James, and Hatten Citation2008). Extending from this, the sub-dimensions of justice are divided into distributive justice and procedural justice, both of which are examined to find the effect they have on relationship performance.

Second, this study examines whether justice perception is the initiator of the causal relationship between brand equity and relationship duration (Rahman, Rodríguez-Serrano, and Lambkin Citation2018). These two endogenous variables are considered important performance indicators for the buying group. A buying group’s brand equity corresponds to a positive attitude from the member-retailer’s evaluation of the group (Davis and Mentzer Citation2008), while relationship duration corresponds to the member-retailers’ positive behavior toward the buying group (Kumar, Bohling, and Ladda Citation2003). The causal relationship can be considered in this form: attitude initiates behavior, that is, a movement from brand equity to relationship duration. We assume justice perception takes the role of initiating this causality.

Third, this study investigates whether justice perception is a constant driver of member-retailers’ attitudes. Specifically, we check the effect of member-retailers’ intention of strategic integration on the relationship between justice perception and buying group’s brand equity. This identifies the circumstantial conditions under which justice perception is effective in fostering positive attitudes of the member retailers (Luo Citation2008). The findings of this research offer implications for resource allocation decisions in practical application (Liu et al. Citation2012). Furthermore, we augment the literature on justice by demonstrating the roles of justice perception in the constructs of the loosely connected B2B relationship.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we explore existing research that has targeted justice perception. We move onto conceptual framework and hypotheses in Section 3 and provide our methodology in Section 4. Finally, we outline our results in Section 5 and discuss their theoretical and practical implications, study limitations, and research extension ideas in Section 6.

Research background

Justice has been emphasized as the basis for mutual activities within organizations in prior studies investigating organizational behavior. In particular, the role of justice is more important when a series of activities are undertaken as compensation to members (Brown, Cobb, and Lusch Citation2006; Luo et al. Citation2015). With justice playing an important role in improving the relationship performance of members within and between organizations, justice perception improves commitment to relationships (Kumar, Scheer, and Steenkamp Citation1995; Liu et al. Citation2012). The literature on management defines justice as the employee’s evaluation of fairness in the organization’s managerial structures and processes (Greenberg Citation1990). This approach has been extended from an intra-organizational level to understand whether the organization interacts with partners fairly and equally in inter-organizational exchange relationships (Kumar, Scheer, and Steenkamp Citation1995).

Extant research on justice perception has examined and identified its sub-dimensions (Bouazzaoui et al. Citation2020; Colquitt et al. Citation2001). Starting with distributional justice, the distinction of where the reference point is created is important. When members evaluate the relationship quality with the affiliated organization, they consider not only the exchange of the benefit and burden between themselves and the organization but what is being imposed on other members as well (Choi and Chen Citation2007). The differentiating point is whether the criterion for evaluation of relationship quality is placed internally or externally. Members that utilize an internal reference point for evaluation of the organization review their own experience and anticipate future standing with the counterpart in terms of the contributions and rewards exchanged (Kahneman Citation1992; Lee and Shin Citation2000; Rutte and Messick Citation1995). By contrast, members who apply external reference point for assessment, compare the benefits and burdens received by other members to their own (Erdogan and Liden Citation2006; Ghosh, Sekiguchi, and Gurunathan Citation2017).

However, the placement of reference point for evaluation, internal or external, is not exclusive and can occur simultaneously (Ordóñez, Connolly, and Coughlan Citation2000). For instance, the external reference for evaluation can be considered even while utilizing the internal reference. Hence, in strict examinations, the question of which criteria is prioritized as the reference point should be reviewed. When external criteria are considered more important, the homogeneity of members is high (Buchanan Citation2008; Younts and Mueller Citation2001) and the utilization of external criteria may appear more among inter-organizational members than in intra-organizational members (Anderson and Narus Citation1990; Gassenheimer, Houston, and Davis Citation1998).

It is relatively difficult to compare the benefit and burden for members in an intra-organization environment than those in inter-organization environment as they have limitations in identifying members to compare with and access their information (Mannix, Neale, and Northcraft Citation1995). In an inter-organizational context, such as the voluntary chain, it is easier to make comparisons between retailers as the homogeneity of members is high (Rokkan and Buvik Citation2003; Scheer, Kumar, and Steenkamp Citation2003; Shaw, Dawson, and Harris Citation1994). As a result, in the loosely connected structure, member retailers consider distributive justice a key factor in evaluating the relationship quality with the buying group.

Extending from distributive justice, existing research has considered procedural justice as well (Korsgaard, Schweiger, and Sapienza Citation1995; Masterson et al. Citation2000). These two concepts are deeply related as they play a complementary role in practice. The role of procedural justice is emphasized when there is a perceptual ambiguity on whether distributive justice has been established. Joy and Witt’s (Citation1992) study of organizational justice has empirically tested that procedural justice has a moderating effect on the causal relationship between distributive justice and performance. When there is no such ambiguity, the complementary role of procedural justice diminishes and each sub-dimension assumes its own role (Griffith, Harvey, and Lusch Citation2006; Hofer, Knemeyer, and Murphy Citation2012; Konovsky Citation2000).

If an organization’s decision-making is considered to have no proper standards, it means that the level of justice within or between organizations is low (Konovsky Citation2000). Systematization of decision-making procedures and processes increases the probability of members’ expectations that certain results will correspond to certain conditions (Hauenstein, McGonigle, and Flinder Citation2001). In this respect, procedural justice is a priori justice that must be prepared in advance, whereas distributive justice is a posteriori justice (Gilliland Citation1994). In research models from existing inter-organizational justice perception studies, there are only a few cases where justice is applied as a response variable (i.e., endogenous variable) (Blessley et al. Citation2018) or a moderator variable (Crosno, Manolis, and Dahlstrom Citation2013); most of them focus on the role of justice perception as an exogenous variable.

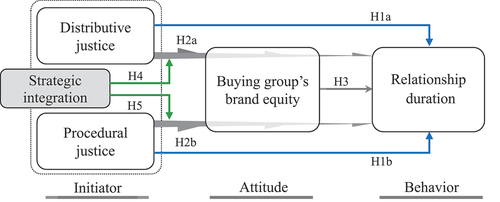

provides a summary of the existing studies that have mainly used distributive and procedural justice as sub-dimensions of justice. It also provides the dependent variables used in each study, along with mediating and moderation variables adopted in the research model. The majority of the models explain the structural paths between justice and relationship performance constructs. In addition, the review of the moderating effect of justice is limited, which requires further examination. By contrast, in our research model, justice perception will be examined in three ways in the research model as visualized in . First, justice perception assumes the role of a direct driving force toward the response variable. Second, it plays the role of initiating the causal relationship between attitude and behavior. Third, by separating and identifying the sub-dimensions of justice perception, the model shows that justice perception induces attitude.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework.

Table 1. Summary of extant research on justice perception.

Conceptual framework and hypotheses development

The research model focuses on reflecting the key roles of justice perception in loosely connected B2B relationships. As shown in , we adopt the concept of justice perception applied in intra- and inter-organizational contexts to address how member-retailers’ justice perception leads to relationship performance. We propose a conceptual framework that examines distributive and procedural justice perception affecting the buying group’s brand equity and the duration of its relationship with a member retailer.

We separate the different roles of justice perception into three in the context of retail buying groups. First, we postulate the direct paths in which distributive (i.e., the extent to which a member retailer perceives justice or fairness in the distribution of outcomes or earnings) and procedural justice (i.e., the extent to which a member retailer perceives the procedure of decision-making) perceptions may significantly affect relationship duration (i.e., the relationship length or continuity of the membership of a member-retailer with the affiliated retail buying group) (Kaynak et al. Citation2015). Second, the two sub-dimensions of justice perception are positioned to be covered before the relationship between the buying group’s brand equity (i.e., the extent to which a member retailer perceives the brand equity of its retail buying group) and the member-retailer’s relationship duration (Poujol et al. Citation2013). We describe this flow as a path driven by justice perception (Jin, Park, and Kim Citation2008). By assigning this position to justice perception, we can use the model to identify the mediating role of brand equity in the B2B channel context (Hernández-Espallardo and Navarro-Bailón Citation2009).

Finally, the member-retailer’s strategic integration (i.e., the extent to which a member retailer gets progressively involved in the joint activities of the affiliated retail buying group) is added as a conditional variable. Applying this moderator, we can examine what conditions allow the effective operation of the two sub-dimensions (Gu and Wang Citation2011; Luo Citation2008; Wang, Craighead, and Li Citation2014). Even though some prior studies include interactional justice or informational justice (Duffy et al. Citation2013; Liu et al. Citation2012), this research focuses on justice perceptions regarding benefits and burdens in terms of how expectations and actual compensations are met and how the buying groups impose them. The former corresponds to distributive justice perception and the latter corresponds to procedural justice perception. The rationale behind using only two of the sub-dimensions of justice perception lies in their importance. Distributive justice ensures fairness in the outcomes of the exchanges in a B2B context, such as allocation of profits, pricing structures, or distribution of resources among partnering organizations. Procedural justice pertains to the fairness of decision-making procedures, contractual negotiations, and the overall transparency of processes within B2B relationships. Narrowing the focus to these dimensions will provide a more comprehensive understanding of justice perception in the context of business exchanges between loosely connected members.

Justice perception as a driver of relationship duration

In this study, we argue that justice perception is positively related to relationship duration. Justice means that all member-retailers are treated equally by the buying group’s headquarters. Equal treatment is defined as follows. The headquarter adequately provides what the member-retailers expect, and such benefits are provided from a perspective of equity without discrimination (Rokkan and Haugland Citation2002). The same applies to the burden borne by member-retailers. Due to the nature of the loosely connected B2B relationship, member-retailers contribute by participating in the operation of the buying group’s operations, where it is important to be treated in equal measure based on their contribution (Choi and Chen Citation2007). Member-retailers treated equally continue to use the buying group’s services, leading to transactions in the long term (Kaynak et al. Citation2015).

The implicit transaction norms are also important for equal treatment of member retailers, but for these norms to function consistently, it is necessary to institutionalize the process and procedures (Andersen, Christensen, and Damgaard Citation2009). As the perception of equal treatment and the predictability of future events are enhanced by the systematic operation of buying group, the intention to continue using the service of buying group increases and leads to a longer relationship duration. This argument is in the same context as existing studies that have shown how the establishment of procedures to achieve fairness precedes the performance of inter-organizational relationships (Liu et al. Citation2020; Luo Citation2008).

As discussed above, member retailers’ perceptions of being treated equally and such treatment being procedurally equal serve as a major cause for member retailers to maintain their relationship with the buying group. This implies that the importance of the quality of benefits and operations goes beyond their existence as key variables in maintaining relationships. Consequently, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1:

Distributive justice (a) and procedural justice (b) have a positive direct impact on the duration of the member-retailer’s relationship with its buying group.

Justice perception as an initiator of the causal relationship between brand equity and relationship duration

This study assumes that the brand equity of the retail buying group leads to the relationship duration between the buying group and member retailers. As we argue that such a causal relationship is initiated by member retailers’ justice perception, we focus on presenting the causal sequences in which brand equity mediates the relationship between justice perception and relationship continuation.

Despite the importance of brand equity management in the B2B context, it is insufficient in terms of quantity compared to the research on brand equity in the B2C context. Despite some commonalities in the conceptual definitions and practical applications of B2C and B2B brand equity, efforts should be made to meet the practical demands that reflect the unique characteristics of the B2B context from an academic perspective (Biedenbach, Hultén, and Tarnovskaya Citation2019; Wang et al. Citation2018; Zhang et al. Citation2015).

B2B managers have begun to recognize the importance of brand equity along with conventional managerial aspects such as low prices and timely delivery of products (Bendixen, Bukasa, and Abratt Citation2004). However, it is difficult to ascertain the results of brand equity management, and there is a limit to clarifying the efforts made to form brand equity (Leek and Christodoulides Citation2011). Rahman, Rodríguez-Serrano, and Lambkin (Citation2018) identified the inputs and outputs of brand management by focusing on brand equity and studying both the causes and consequences of brand equity in the B2B context. This study focuses on the justice perception among member retailers as an input cause and relationship duration as an output consequence of brand management.

Justice perception and brand equity

Existing studies have explored the antecedents of the B2B brand equity in various research contexts. From the resource utilization perspective, these antecedents can be divided into three main categories: promotional activities, innovation initiatives, and relationship management (Rahman, Rodríguez-Serrano, and Lambkin Citation2018). Additionally, van Riel, de Mortanges, and Streukens (Citation2005) adopted value for money, distribution performance, promotional activities, and skilled employees as basic antecedents of B2B brand equity. Biedenbach and Marell (Citation2010) explored customer experience and Zhang et al. (Citation2015) explored brand capability as antecedents. More recently, the antecedents of B2B brand equity have evolved to include normative facets, such as corporate environmentalism (Rahman, Rodríguez-Serrano, and Faroque Citation2021). Justice perception, as an antecedent of brand equity formation, corresponds to relationship management with business partners and the enhancement of the experience of the member retailer as a customer in the retail buying group.

In particular, few studies have considered the antecedents of brand equity formation in relationship management (Biedenbach, Hultén, and Tarnovskaya Citation2019; Han and Sung Citation2008). Justice perception, a representative variable of relationship management, can be considered an input to brand management that contributes to the formation of brand equity (Rahman, Rodríguez-Serrano, and Lambkin Citation2018). As a specific assessment of the policies and operations of the buying group by member retailers in terms of distribution and procedures, the perception of justice leads to a positive attitude toward the retail buying group. This attitude is a comprehensive result of the assessment made by member retailers, which affects the brand equity of the buying group.

The idea that a high level of justice perception is correlated with relationship quality in inter-organizational management is in line with existing research. In the B2B context, the importance of the role played by a brand differs according to the type of relationship (Webster and Keller Citation2004).

This study focuses on loosely connected relationships, where justice perceptions regarding compensations and procedures help build the member-retailers’ attitude toward the buying group (Rokkan and Haugland Citation2002). Therefore, justice perception, as an evaluation of the buying group, affects brand equity as a construct and thereby reflecting the customer’s overall attitude. Consequently, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2:

Distributive justice (a) and procedural justice (b) have a positive direct impact on a buying group’s brand equity.

Brand equity and relationship duration

It is possible to observe that the formation of brand equity affects the performance of a company in B2C and B2B contexts. In existing B2C marketing research, including consumer behavior area, the notion that positive attitude leads to behavior has entered a stage of theorization (Bouazzaoui et al. Citation2020; Colquitt et al. Citation2001; Whitman et al. Citation2012).

van Riel, de Mortanges, and Streukens (Citation2005) showed that brand equity is associated with loyalty by distinguishing it into product and corporate levels. Homburg, Klarmann, and Schmitt (Citation2010) claimed that brand awareness, a sub-dimension of brand equity, has a positive correlation with market performance. Specifically, utilizing differences in customer loyalty against competitors to measure market performance includes both new customer creation and existing customer retention. Wang et al. (Citation2018) followed the resource advantage theory to divide the B2B brand equity into six sub-dimensions and tested their effects on corporate performance. Customer-perceived value and loyalty are adopted as variables for corporate performance.

Extant research emphasizes that increased customer loyalty could be adopted as a key performance variable of brand equity in the B2B context. Customer loyalty, which is the buyer’s increased response to repeated referrals from the seller in the B2B context, can be expanded by the duration of the relationship.

To understand the evaluation of the retail buying group by member-retailers, this study focuses on how relationship duration, is influenced by the buying group’s brand equity (Jin, Park, and Kim Citation2008; Poujol et al. Citation2013). With brand equity as the key mediating construct of member-retailers’ evaluation of buying group’s activities, justice perception by member retailers as participants must be investigated to understand the causal relationship between brand equity and relationship duration as well. Consequently, we propose the following hypotheses.

H3:

The buying group’s brand equity has a positive direct impact on relationship duration.

Justice perception as an inconstant antecedent of brand equity affected by strategic integration

Based on extant literature, one can argue that justice perception is the leading variable of relationship performance. Various studies, such as Bouazzaoui et al. (Citation2020), Colquitt et al. (Citation2001), and Whitman et al. (Citation2012), have generalized that the formulation of members’ justice perception fosters a positive attitude toward the organization. However, at the sub-dimension level, justice perception does not necessarily result in the formation of a positive attitude (Brown, Cobb, and Lusch Citation2006; Dong et al. Citation2019; Duffy et al. Citation2013; Hofer, Knemeyer, and Murphy Citation2012; Hoppner, Griffith, and Yeo Citation2014; Liu et al. Citation2012; Qiu Citation2018; Srinivasan, Narayanan, and Narasimhan Citation2018). Therefore, it is crucial that we find the most effective condition that allows the two sub-dimensions of justice perception to foster a positive attitude among the members (Luo Citation2008; Poujol et al. Citation2013).

It is also important to secure justice perception in loosely connected relationships and to identify the moderating effect on the relationship between justice perception and attitude to determine which sub-dimension to prioritize (Dong et al. Citation2019). In a loosely connected relationship, the diversity in motives for participation in the buying group can be considered based on their status (Reijnders and Verhallen Citation1996). Being smaller in scale and having fewer competitive advantages than large-scale retailers do, these members participate in buying groups to pursue strategic integration to compete against the large retailers (Geyskens, Gielens, and Wuyts Citation2015).

Competitive resources comprise the internal and external assets of an organization (Barney Citation1991). In the dynamic market environment, it is important to strengthen internal assets, but effective use of external assets is essential to maintain competitive advantage and improve business performance (Teece, Pisano, and Shuen Citation1997). In our research context, strategic integration allows small independent retailers to enhance market performance (Picot-Coupey, Viviani, and Amadieu Citation2018), because it enables small independent retailers to complement insufficient internal resources with external resources provided by the buying group (Hernández-Espallardo Citation2006; Sandberg and Mena Citation2015). According to Hernández-Espallardo (Citation2006), the variation in the level of interest for strategic integration among member retailers reflects the difference in the expectations of using external resources.

When the expectation of strategic integration is high, a more positive evaluation of driver variables such as justice perception is likely to strengthen response variables such as positive attitude formation. Small independent retailers have relatively higher expectations of strategic cooperation that lead to strategic integration (Ghisi et al. Citation2008). Such expectations function as a survival strategy in the competition that small retailers face from large-scale retailers who have an advantage in the market. The expectation of strategic integration interlocks with the expectation of justice among the integrated parties resulting in the formation of attitude. Conversely, those with a lower intention of strategic integration are more likely to have no interest in the role of justice perception. Consequently, we posit the following hypotheses.

H4:

A higher level of strategic integration induces more positive relationship between distributive justice and the buying group’s brand equity.

H5:

A higher level of strategic integration induces more positive relationship between procedural justice and the buying group’s brand equity.

Research methodology

Research context

This study examines Japanese retail buying groups in supermarkets for several reasons. Under circumstances in which larger retail chains increasingly dominate the retail market, retail buying groups can be powerful tools for independent small retailers to compete with larger retailers by leveraging scale economies (Kim, Miao, and Hu Citation2022). By joining a buying group, member retailers can achieve a range of goals ranging from survival to sustainable growth. Consequently, retail practitioners and policymakers have increasingly recognized the importance of these groups.

Despite limitations to the generalizability of the findings and discussions, we believe that an examination of retail buying groups in Japan is an appropriate target for addressing managerial challenges in retail buying groups. The rationale for this is as follows: First, based on key findings from interviews with Japanese retail buying groups, both owners of member retailers and the managers at the group headquarters have recognized the significant importance of the group’s justice perception because it can be the driver of relationship performance to combat larger national retail chains. Simultaneously, however, they found it a very demanding task. Second, as supermarket retailers generally deal with a wider range of merchandise than major retailer types do, procedures and processes in decision-making on merchandising (e.g., supplier/merchandise selection, logistics, or marketing campaigns) have become relatively more complex (Kim and Takashima Citation2019). Accordingly, for more progressive involvement by member retailers who are independent owners, the challenge of management skills by the headquarters, such as organizational justice, remains.

In Japan, while CGC Japan and Zennisshoku Chain, the two largest organizations, cover the country-wide supermarket retailer sector, a few retail buying groups focus on specific geographical market areas, such as AKR Kyoueikai in the Kansai district, Marusho Chain in the Tokyo metropolitan district, and Nihon Selco in the Kanto and Hokuriku districts. Smaller retailers with one or two stores have tended to join the Zennisshoku Chain (1,615 stores as of August 2021), while CGC Japan (204 member retailers with 4,218 stores, as of May 2022) represents relatively medium-sized supermarket retailers.

Data collection

We conducted a questionnaire survey of 1,573 small and medium-sized retailers that have a membership of eight different retail buying groups in the supermarket industry. We considered the president or the CEO of each member retailer as the key informant as they have the best understanding of their business as well as of the affiliated retail buying group. For data collection by telephone, we informed prospective respondents about the purpose of the survey and the one-month deadline for returning the completed survey. Shortly after this pre-notification, this study distributed and gathered a survey questionnaire over one month without any additional reminder. Because this study didn’t identify early and late respondents for this reason, we did not check a non-response bias. We obtained 241 usable responses (sample size 241; 15.3% response rate) within the deadline.

A brief description of our respondents follows. The average relationship duration for a member retailer was 14.86 years (median = 12.00, SD = 10.99). Of the 241 samples, while a majority of retailers (163 retailers, 67.63%) had a membership with the Zennisshoku Chain, 26 retailers (10.79%) were affiliated with CGC Japan. The average value of purchase ratio via the affiliated retail buying group to total sales was 47.80% (median = 47.80, SD = 21.14). The average number of stores owned by the member-retailers was 3.86 (Median = 1.00, SD = 8.51), and 173 of them (71.8%) owned one or two stores.

Measurement

presents the final items of our constructs. Except for relationship duration, the other four constructs are multi-item and reflective. This study used a five-point scale (1 = “strongly disagree” and 5 = “strongly agree”).

Table 2. Constructs and measurement assessment.

Building on Crosno, Manolis, and Dahlstrom (Citation2013), we measured both distributive and procedural justice perception of the retail buying groups using three items. Second, based on Hernández-Espallardo and Navarro-Bailón (Citation2009), we measured the buying group’s brand equity using five items ⎯ recognition, image, quality, personality, and loyalty. Third, we measured member-retailers’ strategic integration using four items adopted from Hernández-Espallardo (Citation2006). Fourth, applying insights from Liu et al. (Citation2010), we measured relationship duration by assessing the actual relationship length of the membership of each member-retailer with the affiliated retail buying group.

Finally, this study employed five control variables to explain the observed heterogeneity among our samples: affiliation, number of stores, purchase ratio, geographical distance, and sales performance. Given that independent retailers’ strategies vary with their size and the different types of retailers’ co-operatives (Kennedy Citation2016), we needed to control for the number of stores and affiliations. A value of 1 was assigned to member retailers who are part of the Zennisshoku Chain and 0 to all others, and the actual number of stores owned by each member retailer was examined. As the proxy measure of commitment to the affiliated group, we controlled for the ratio of the purchase made by each member retailer through the affiliated headquarter to its total sales. To control the effect of the physical distance on member-retailers’ behavior in retail buying groups (Rokkan and Buvik Citation2003), we measured the geographical distance between the headquarters and the member-retailers’ store location with one item (1 = very close and 5 = very far). Finally, considering the close relationship between firm performance and membership (Reijnders and Verhallen Citation1996) and the impact of firms’ past performance on the continuity of existing relationships, we measured for each member-retailer’s sales performance (as a proxy measure of firm performance) over three years with one item (1 = highly decreased and 5 = highly increased).

Analysis and results

Following a two-step procedure of the covariance-based structural equation model (CB-SEM) with AMOS 27 (Byrne Citation2010; Niemand and Mai Citation2018), we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis using the measurement model and tested the hypotheses using the structural model. The rationale for this is that, in addition to the provision of useful model fit indices, CB-SEM is superior for factor-based models that our study develops and tests to other techniques, such as partial least squares based structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) with better fit for composite-based models (Dash and Paul Citation2021).

Measurement assessment

Overall, the results of the measurement model suggest a satisfactory fit to the data (χ2(81) = 100.10, p > 0.05, CMIN/DF = 1.24, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, GFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.03). By applying Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981)’s guideline, we checked construct validity (i.e., convergent and discriminant validity) to validate scale items. Specifically, to assess convergent validity, we calculated two values of the average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR). The results in reveal that the values of AVE (0.50 ~ 0.66) and CR (0.79 ~ 0.86) of every construct meet the threshold of 0.5 and 0.6, respectively, implying good convergent validity. Then, to assess discriminant validity, we compared the shared variance (r2) between each pair of constructs with the AVE values between them (). We observe no shared variance (0.18 ~ 0.30) higher than the AVE (0.50 ~ 0.66), implying good discriminant validity.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics and the correlation matrix.

Additionally, to mitigate the concern of common method bias, we conducted a marker variable test. Following Lindell and Whitney (Citation2001), we assumed a theoretically unrelated item (i.e., to what extent can you predict the market environment for your firm over the last three years?) as a covariate (|r| < 0.12, p > 0.05). No significant differences were found between the observed and adjusted correlations, ruling out common method bias in our data.

Results of hypothesis testing

Overall, the results of the structural model suggest a satisfactory fit to the data (χ2(92) = 124.01, p < 0.05, CMIN/DF = 1.35, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, GFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.04). presents the summary of hypothesis testing regarding direct effects (for H1 ~ H3). Specifically, the results show that while distributive justice perception has a positive and significant effect on relationship duration (H1a: β = 0.28, p < 0.01), no procedural justice perception has a significant effect (H1b: β = −0.05, p > 0.05). Thus, H1a is accepted, but H1b is rejected. While procedural justice perception has a positive and significant effect on the buying group’s brand equity (H2b: β = 0.61, p < 0.001), no distributive justice perception has a significant effect (H2a: β = 0.05, p > 0.05). Thus, H2a is rejected, but H2b is accepted. Lastly, the results reveal that the buying group’s brand equity has a positive and significant effect on relationship duration (H3: β = 0.20, p < 0.05); thus, H3 is accepted.

Table 4. Results of path analysis for main effects.

summarizes the summary of hypothesis testing regarding moderating effects (for H4 and H5). Following prior studies (Byrne Citation2010; Kim and Takashima Citation2019), we applied a multi-group analysis. First, based on the mean value of strategic integration (mean = 3.96), we divided 241 samples into two groups: a high group of strategic integration (n = 142) and a low group of strategic integration (n = 99). Then, we developed an unconstrained (i.e., estimating each direct path between the high and low groups freely) and a constrained model (i.e., imposing an equality constraint on the same path). Finally, to test the hypotheses, we conducted an χ2 difference test by comparing the two models.

Table 5. Results for moderating effects of strategic integration.

As shown in , we observe a significant difference between the two models in both H4 (△χ2 (1) = 7.00, p < 0.01) and H5 (△χ2 (1) = 6.45, p < 0.05). However, our results are interesting: strategic integration has differential moderating impacts on the relationship between distributive/procedural justice perception and the buying group’s brand equity. Specifically, the link of distributive justice perception to buying group’s brand equity becomes stronger for the high group of strategic integration (β = 0.17, p > 0.05) under H4 than for the low group (β = −0.36, p < 0.05). Yet, contrary to H5, the link between procedural justice perception and the buying group’s brand equity becomes stronger for the low group of strategic integration (β = 0.93, p < 0.001) than for the high group (β = 0.45, p < 0.001). Hence, H4 is accepted but H5 is rejected.

As a post-hoc analysis, we investigated the indirect effects of the buying group’s brand equity mediating the relationships between distributive/procedural justice perception and relationship duration. Based on the results of the bootstrapping method (Byrne Citation2010), we observe that while procedural justice perception has a positive and significant indirect effect on buying group’s brand equity (β = 0.12, p < 0.05), no distributive justice perception has a significant indirect effect (β = 0.01, p > 0.05). We also checked for additional moderating effects of strategic integration. We find a nonsignificant difference in three other possible links that we did not hypothesize in : the link between distribution justice perception and relationship duration (△χ2 (1) = 0.70, p > 0.05), between procedural justice perception and relationship duration (△χ2 (1) = 2.70, p > 0.05), and between the buying group’s brand equity and relationship duration (△χ2 (1) = 2.86, p > 0.05).

Regarding multicollinearity concerns, an additional analysis reveals that the values of the variance inflation factor in regression are below 1.83, suggesting that multicollinearity does not seem a major issue in our data. None of the control variables – affiliation (β = 0.02, p > 0.05), purchase ratio (β = 0.11, p > 0.05), number of stores (β = 0.12, p > 0.05), geographical distance (β = −0.06, p > 0.05), and sales performance (β = −0.12, p > 0.05) – are significantly associated with relationship duration. The findings are not contingent on the inclusion or exclusion of these control variables.

Finally, although we tried to control the observed heterogeneity among samples, the possible reverse causality on the path between buying group’s brand equity and relationship duration may cause an endogeneity problem. This is because by building relationship trust (Biedenbach, Hultén, and Tarnovskaya Citation2019), member-retailers with a longer membership may increase the perception of the affiliated group’s brand equity. Following the procedure suggested by prior studies (Jean et al. Citation2016; Rutz and Watson Citation2019), we tested for potential endogeneity of this path, employing a two-stage least-squares (2SLS) regression model with the instrumental variable.

Specifically, we examined candid communication (i.e., the buying group is candid in its communication with me) as an instrumental variable. The findings of several interviews show that, from the member-retailers’ perspective, although buying groups’ candid communication with their members is important (Kim, Miao, and Hu Citation2022; Sandberg and Mena Citation2015), the decision about maintaining a relationship with the affiliated buying group significantly depends on the level of various attractive benefits the group offers. Given the significant role of communication in building brand equity (Baumgarth and Schmidt Citation2010), we assume that buying groups’ candid communication can be a theoretically relevant instrumental variable that affects relationship duration by increasing the buying group’s brand equity.

The results of the 2SLS regression model were consistent with the findings of our proposed model (b = 7.32, p < 0.01); that is, the endogeneity of possible reverse causality was not a problem in our data (). Additionally, we conducted a regression of the residual calculated in the 2SLS estimation on the instrumental variable (i.e., candid communication). The results provided concrete evidence that, since we could not reject the null hypothesis that the instrumental variable is not correlated with error, candid communication can be theoretically considered as an exogenous variable (R2 = 0.00, F-statistic [1, 239] = 0.00, p > 0.05).

Table 6. Results of a two-stage least-squares (2SLS).

Discussion and implications

With the retail business environment changing rapidly, the role of quasi-integrated channel structure in maintaining loosely connected relationships between member-retailers and their buying group is becoming important (Hernández-Espallardo and Navarro-Bailón Citation2009). Member-retailers’ justice perception is crucial to deriving cooperation and collaboration within quasi-integrated organizations (Cai, Yang, and Hu Citation2009). The buying group headquarters should be fair in providing benefits to and imposing burdens on participating member retailers. However, existing studies have not thoroughly investigated the role of justice perception in the inter-organizational context, whether there is a difference in the influence on relationship performance by the type of justice perception, and under what conditions justice perception is more effective (Bouazzaoui et al. Citation2020).

This research stands apart from prior research in terms of the effects of the sub-dimensions of justice. As shown in , many studies have not distinguished between distributive and procedural justice as an explanatory element of the dependent variable (Brown, Cobb, and Lusch Citation2006; Griffith, Harvey, and Lusch Citation2006; Hofer, Knemeyer, and Murphy Citation2012; Kaynak et al. Citation2015; Liu et al. Citation2012; Poppo and Zhou Citation2014; Poujol et al. Citation2013; Wang, Craighead, and Li Citation2014). The difference in the explanatory power of the two justice perceptions found in this research is in line with some previous works as well (Duffy et al. Citation2013; Hoppner, Griffith, and Yeo Citation2014; Jia et al. Citation2021; Luo et al. Citation2015; Qiu Citation2018; Srinivasan, Narayanan, and Narasimhan Citation2018; Zaefarian et al. Citation2016). The difference in the moderating effect on the relationship between attitude and behavior was discussed on a theoretical level in this study, unlike in any previous research.

Theoretical implications

This study makes two core contributions to the academic literature. First, we examine the role of justice perceptions in two types of relationship performance in the context of retail buying groups: brand equity and relationship duration. In business performance studies, the measurement of performance has been defined and operationalized as goal achievement (Franco-Santos et al. Citation2007). The diversity in goal-setting based on different business environments calls upon the diversification of defining and measuring performances. By classifying relationship performance into two, this research model shows that process performance (Van Looy and Shafagatova Citation2016) is differentiated from outcome performance, which existing B2B relationship studies have focused on (Jap and Ganesan Citation2000). The evaluation of brand equity and relationship duration included in this research model reflects the sequence, from process goals to outcome goals, of the relationship between member retailers and the buying group. By separating the performance variables, the causality between the two sub-dimensions of justice perception and the two performance variables are clearly identified.

In this study, relationship duration between the buying group and member retailers was considered as outcome performance and member-retailers’ brand equity evaluation was considered as process performance. Distributive justice perception increased relationship duration, which is outcome performance, whereas procedural justice perception improved the evaluation of brand equity, which is process performance. Each sub-dimension was not able to correspond with other performances, confirming that the role of justice perception was matched with the performance of a similar nature.

Specifically, the role of procedural justice perception is more important in deriving process relationship performance, and the role of distributive justice perception is more important in deriving outcome relationship performance. This study also establishes that procedural justice perception has an indirect effect on relationship duration (Luo Citation2008), whereas distributive justice perception has only a direct effect on brand equity (Pan et al. Citation2020). The sequential causality starting from justice perception to attitude and finally, behavior is possible only when procedural justice perception is secured.

Second, we investigate the moderating condition that increases the effectiveness of justice perception in the evaluation of brand equity: attitude toward the buying group (Hernández-Espallardo and Navarro-Bailón Citation2009). Studies have utilized justice perception as a moderating effect (Crosno, Manolis, and Dahlstrom Citation2013) but it is rare to find any with variables that moderate the relationship between justice perception and relationship performance. By suggesting the application of a moderating variable to the relationship between justice perception and relationship performance, this model has shown not only the circumstances in which the sub-dimensions of justice perception are effective but also that justice perception does not always induce relationship performance. All prior research has been based on the notion that justice leads to relationship performance; this study is distinct in that we confirm the difference in the explanatory power of the sub-dimensions of justice perception against performance.

We adopt strategic integration as a moderating factor in this study. It is a construct of the member-retailer’s intention to participate in the buying group (Hernández-Espallardo Citation2006), and reflects their expectations of the cost and benefits of the group. Through differences in expectations, the positive moderating effect of strategic integration works on how brand equity evaluation is affected by distributive justice perception, and not procedural justice perception.

The degree of the member-retailer’s intention toward strategic integration as the motivation for participation affects the evaluation of the effectiveness of the buying group headquarters’ efforts. High strategic integration was partially confirmed as a condition that views the relationship between justice perception and brand equity evaluation more positively. Since the strategic integration intention reflects competition in the retail business environment, it suggests efficient conditions for distributive justice perceptions that are more obvious and prioritized in competition (Brown, Cobb, and Lusch Citation2006; Dong et al. Citation2019).

We find that the relationship between procedural justice perception and brand equity evaluation conflicts with the hypothesis regarding the moderating effect of strategic integration (Luo Citation2008). When strategic integration intention was low, procedural justice perception showed a relatively strong influence on evaluating brand equity. When such intention was high, procedural justice perception had a weaker effect in inducing positive attitude toward the buying group’s brand equity. Comparatively, a lower intention of strategic integration attracted greater effect from the role of procedural justice perception in attitude formation (Viswesvaran and Ones Citation2002). A lower degree of intention for strategic integration to cope with competitors suggests that the role of justice perception in process is more important than that in the size and form of benefits and costs (Paese, Lind, and Kanfer Citation1988).

Managerial implications

The study offers two major implications for headquarter managers of retail buying groups pursuing mutual benefits and assistance networks. First, the managers must have a thorough understanding of the role of justice perception. Justice perception is based on equal compensation and treatment among the members participating in the buying group (Bouazzaoui et al. Citation2020). Member retailers compare their benefits and burdens to those of other participating members, as those participating in the voluntary chain are homogenous and adopt a high level of information-sharing (Mazzarol et al. Citation2018). When the level of information sharing is high among members maintaining both formal and informal communication channels, it is important to ensure that the principles for raising the perception of distributive justice are followed (Griffith, Harvey, and Lusch Citation2006). The role of procedural justice perception can support the establishment of norms and their acceptance (Lin et al. Citation2007). Since the roles of distributive justice and procedural justice perception are complementary, it is necessary to consider their balance and harmony.

In addition, managers should adopt prioritization when resources for building both sub-dimensions of justice perception are limited. Considering the current status of the buying group, the manager needs to determine which is more important: perception of justice in process performance or justice in consequential performance. The relationship life cycle can be considered a representative internal status factor (Dowell, Morrison, and Heffernan Citation2015). From the perspective of a relationship development stage, early-stage relationships are required to establish a perception of distributive justice that improves consequential performance. However, relatively mature relationships can consider the assistance of procedural justice perception that leads to process performance (Blessley et al. Citation2018; Srinivasan, Narayanan, and Narasimhan Citation2018). Of course, if managerial resources are sufficient, efforts to enhance the perception of procedural fairness should be pursued even in the early stages. Also, managers of the buying group headquarters in early relationships with member retailers should continue to review the health of the relationship by monitoring quality before considering entering the next stage (Hennig‐Thurau and Klee Citation1997).

Second, managers of the buying group headquarters should categorize member retailers and manage segments. It is essential to understand the member-retailer’s motivation to participate in the buying group as a basis for segmentation (Cortez, Clarke, and Freytag Citation2021). The classification of member retailers based on the intention of strategic integration, applied as a moderating variable, shows that the two sub-factors of justice perception differ in the formation of attitudes such as brand equity evaluation. The manager should pay attention to the fact that intuition of strategic integration is related to the competitive environment of member retailers. This argument presupposes that a retailer with a high intention of strategic integration wants to secure a competitive advantage (Luo Citation2008).

The manager of the buying group headquarters, which provides merchandise and services to member retailers exposed to tough competition, needs to remember that distributive justice perception affects the formation of positive attitudes (Johnson Citation1999). In addition, when member retailers are exposed to relatively less intense competition, the managers should know that positive attitude formation is affected more by procedural justice perception when retailers have lower intentions for strategic integration. Inducement of strategic integration intention and increasing distributive justice perception can be pursued simultaneously as they interact positively in the formation of positive attitude. On the other hand, it has been found that inducement of strategic integration intention and increasing procedural justice perception’s interaction resulted in negative interaction with positive attitude. This indicates that managers should not pursue the two simultaneously but individually with respect to the competitive environment.

Limitations and further research

The study has five limitations that can prompt future research. First, the challenge in improving scale items remains. The results in indicate that the standardized coefficient of factor loading by one scale item is below the threshold of 0.5. Future research would do well to refine scale items by reflecting the real practices of retail buying groups, which would ensure the accuracy of this study’s results. Second, because of prenotification with a short deadline of return to potential respondents, we did not check a non-response bias. Future research would need to carefully identify early and late respondents to mitigate a non-response bias issue in the survey research. Third, the convenience sample with only Japanese data might limit the generalization of this study’s findings and discussions. Our exploration is expected to further encourage cross-national analysis by testing the pivotal role of management skills (i.e., organizational justice, brand equity, and strategic integration) in predicting relationship duration.

Fourth, a problem arises in adopting only two sub-dimensions of justice perception. Due to the nature of B2B marketing, there are limitations in considering the role of interactional or interpersonal justice, which is founded more heavily upon variables based on psychological perception of individuals. Therefore, existing studies on justice perception in the inter-organizational context focus on distributive justice and procedural justice (Hoppner, Griffith, and Yeo Citation2014; Poppo and Zhou Citation2014). However, if the magnitude of psychological perception can be measured, it could be applied to interactional or interpersonal justice to be incorporated in the models developed in this research.

Fifth, one can question the use of proxy variable in the empirical testing of the research questions. One of the challenges of this study was to review whether justice perception plays a role as a trigger in process performance and consequential performance. In process performance, the formation of attitude in evaluation of brand equity was adopted. For consequential performance, the relationship duration of member retailers was included, but the variables used in the existing B2B relationship performance were not considered.

Based on the above, three directions can be proposed for future research. First, to understand the relationship between justice perception and relationship performance between buying group and small retailers, this study tested the research model with a loosely connected B2B relationship. However, the voluntary chain is one of the alternatives to the distribution channel structure, and there are various types of relationship structures depending on the degree of integration in the buyer-seller relationship (Rokkan and Buvik Citation2003). Further verification and generalization of our research findings can be conducted in the future by looking into other relationship structures, for instance, a franchise system with a strongly integrated relationship.

Second, it is possible to include an additional justice sub-dimension to our research model. Some studies in the B2B context have confirmed interaction justice as a sub-dimension of justice to be important, in the cases where psychological variables between boundary personnel representing each organization play a critical role. Future research should start with this type of inter-organizational context, such as the B2B sales process (Rich and Smith Citation2000). In addition, emerging forms of justice can be considered, such as information justice, used recently in organizational justice research (Duffy et al. Citation2013; Liu et al. Citation2012), or corrective justice introduced in macro-marketing research (Mascarenhas, Kesavan, and Bernacchi Citation2008).

Third, the explanatory power of the research model can be enhanced by adding more performance variables. Two relationship performance constructs introduced in this study represent the relationship quality of loosely connected relationship structures but conventionally adopted constructs such as relational satisfaction, benevolence trust, and affective commitment can be included as well. Considering the perception of interactional justice, variables such as psychological contract (Aselage and Eisenberger Citation2003; Rousseau Citation1998) and psychological ownership (Pierce, Kostova, and Dirks Citation2001) may contribute to making relationship performance diversified.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Andersen, P. H., P. R. Christensen, and T. Damgaard. 2009. Diverging expectations in buyer–seller relationships: Institutional contexts and relationship norms. Industrial Marketing Management 38 (7):814–24. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2008.04.016.

- Anderson, J. C., and J. A. Narus. 1990. A model of distributor firm and manufacturer firm working partnerships. Journal of Marketing 54 (1):42–58. doi:10.1177/002224299005400103.

- Aselage, J., and R. Eisenberger. 2003. Perceived organizational support and psychological contracts: A theoretical integration. Journal of Organizational Behavior 24 (5):491–509. doi:10.1002/job.211.

- Barney, J. 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management 17 (1):99–120. doi:10.1177/014920639101700108.

- Barry, J. M., S. S. Graça, V. P. Kharé, and Y. V. Yurova. 2021. Examining institutional effects on B2B relationships through the lens of transitioning economies. Industrial Marketing Management 93:221–34. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.09.012.

- Baumgarth, C., and M. Schmidt. 2010. How strong is the business-to-business brand in the workforce? An empirically-tested model of ‘internal brand equity’ in a business-to-business setting. Industrial Marketing Management 39 (8):1250–60. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2010.02.022.

- Bendixen, M., K. A. Bukasa, and R. Abratt. 2004. Brand equity in the business-to-business market. Industrial Marketing Management 33 (5):371–80. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2003.10.001.

- Biedenbach, G., P. Hultén, and V. Tarnovskaya. 2019. B2B brand equity: Investigating the effects of human capital and relational trust. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 34 (1):1–11. doi:10.1108/JBIM-01-2018-0003.

- Biedenbach, G., and A. Marell. 2010. The impact of customer experience on brand equity in a business-to-business services setting. Journal of Brand Management 17 (6):446–58. doi:10.1057/bm.2009.37.

- Blessley, M., S. Mir, Z. Zacharia, and J. Aloysius. 2018. Breaching relational obligations in a buyer-supplier relationship: Feelings of violation, fairness perceptions and supplier switching. Industrial Marketing Management 74:215–26. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2018.04.011.

- Bouazzaoui, M., H. J. Wu, J. K. Roehrich, B. Squire, and A. S. Roath. 2020. Justice in inter-organizational relationships: A literature review and future research agenda. Industrial Marketing Management 87:128–37. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.02.003.

- Brown, J. R., A. Cobb, and R. F. Lusch. 2006. The roles played by interorganizational contracts and justice in marketing channel relationships. Journal of Business Research 59 (2):166–75. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2005.04.004.

- Buchanan, T. 2008. The same-sex-referent-work satisfaction relationship: Assessing the mediating role of distributive justice perception. Sociological Focus 41 (2):177–96. doi:10.1080/00380237.2008.10571329.

- Byrne, B. M. 2010. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

- Cai, S., Z. Yang, and Z. Hu. 2009. Exploring the governance mechanisms of quasi-integration in buyer–supplier relationships. Journal of Business Research 62 (6):660–66. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.02.004.

- Choi, J., and C. C. Chen. 2007. The relationships of distributive justice and compensation system fairness to employee attitudes in international joint ventures. Journal of Organizational Behavior 28 (6):687–703. doi:10.1002/job.438.

- Colquitt, J. A., D. E. Conlon, M. J. Wesson, C. O. Porter, and K. Y. Ng. 2001. Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. Journal of Applied Psychology 86 (3):425–45. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.425.

- Cortez, R. M., A. H. Clarke, and P. V. Freytag. 2021. B2B market segmentation: A systematic review and research agenda. Journal of Business Research 126:415–28. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.12.070.

- Crosno, J. L., C. Manolis, and R. Dahlstrom. 2013. Toward understanding passive opportunism in dedicated channel relationships. Marketing Letters 24 (4):353–68. doi:10.1007/s11002-012-9220-3.

- Dash, G., and J. Paul. 2021. CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 173:121092. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121092.

- Davis, D. F., and J. T. Mentzer. 2008. Relational resources in interorganizational exchange: The effects of trade equity and brand equity. Journal of Retailing 84 (4):435–48. doi:10.1016/j.jretai.2008.08.002.

- Dong, X., S. Zou, G. Sun, and Z. Zhang. 2019. Conditional effects of justice on instability in international joint ventures. Journal of Business Research 101:171–82. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.04.027.

- Dowell, D., M. Morrison, and T. Heffernan. 2015. The changing importance of affective trust and cognitive trust across the relationship lifecycle: A study of business-to-business relationships. Industrial Marketing Management 44:119–30. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2014.10.016.

- Duffy, R., A. Fearne, S. Hornibrook, K. Hutchinson, and A. Reid. 2013. Engaging suppliers in CRM: The role of justice in buyer–supplier relationships. International Journal of Information Management 33 (1):20–27. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2012.04.005.

- Erdogan, B., and R. C. Liden. 2006. Collectivism as a moderator of responses to organizational justice: Implications for leader‐member exchange and ingratiation. Journal of Organizational Behavior 27 (1):1–17. doi:10.1002/job.365.

- Fink, R. C., W. L. James, and K. J. Hatten. 2008. Duration and relational choices: Time based effects of customer performance and environmental uncertainty on relational choice. Industrial Marketing Management 37 (4):367–79. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2007.02.004.

- Fornell, C., and D. F. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 18 (1):39–50. doi:10.1177/002224378101800104.

- Franco-Santos, M., M. Kennerley, P. Micheli, V. Martinez, S. Mason, B. Marr, D. Gray, and A. Neely. 2007. Towards a definition of a business performance measurement system. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 27 (8):784–801. doi:10.1108/01443570710763778.

- Gassenheimer, J. B., F. S. Houston, and J. C. Davis. 1998. The role of economic value, social value, and perceptions of fairness in interorganizational relationship retention decisions. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 26 (4):322–37. doi:10.1177/0092070398264005.

- Geyskens, I., K. Gielens, and S. Wuyts. 2015. United we stand: The impact of buying groups on retailer productivity. Journal of Marketing 79 (4):16–33. doi:10.1509/jm.14.0202.

- Ghauri, S., T. Mazzarol, and G. N. Soutar. 2021. Why do SMEs join co-operatives? A comparison of SME owner-managers and co-operative executives views. Journal of Co-Operative Organization and Management 9 (1):100128. doi:10.1016/j.jcom.2020.100128.

- Ghisi, F. A., J. A. G. da Silveira, T. Kristensen, M. Hingley, and A. Lindgreen. 2008. Horizontal alliances amongst small retailers in Brazil. British Food Journal 110 (4/5):514–38. doi:10.1108/00070700810868997.

- Ghosh, D., T. Sekiguchi, and L. Gurunathan. 2017. Organizational embeddedness as a mediator between justice and in-role performance. Journal of Business Research 75:130–37. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.02.013.

- Gilliland, S. W. 1994. Effects of procedural and distributive justice on reactions to a selection system. Journal of Applied Psychology 79 (5):691–701. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.79.5.691.

- Greenberg, J. 1990. Organizational justice: Yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Journal of Management 16 (2):399–432. doi:10.1177/014920639001600208.

- Griffith, D. A., M. G. Harvey, and R. F. Lusch. 2006. Social exchange in supply chain relationships: The resulting benefits of procedural and distributive justice. Journal of Operations Management 24 (2):85–98. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2005.03.003.

- Gu, F. F., and D. T. Wang. 2011. The role of program fairness in asymmetrical channel relationships. Industrial Marketing Management 40 (8):1368–76. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2011.07.005.

- Han, S. L., and H. S. Sung. 2008. Industrial brand value and relationship performance in business markets: A general structural equation model. Industrial Marketing Management 37 (7):807–18. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2008.03.003.

- Hauenstein, N., T. McGonigle, and S. W. Flinder. 2001. A meta-analysis of the relationship between procedural justice and distributive justice: Implications for justice research. Employee Responsibilities & Rights Journal 13 (1):39–56. doi:10.1023/A:1014482124497.

- Hennig‐Thurau, T., and A. Klee. 1997. The impact of customer satisfaction and relationship quality on customer retention: A critical reassessment and model development. Psychology & Marketing 14 (8):737–64. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(199712)14:8<737:AID-MAR2>3.0.CO;2-F.

- Hernández-Espallardo, M. 2006. Interfirm strategic integration in retailer buying groups: Antecedents and consequences on the retailer’s economic satisfaction. The International Review of Retail, Distribution & Consumer Research 16 (1):69–91. doi:10.1080/09593960500453575.

- Hernández-Espallardo, M., and M. Á. Navarro-Bailón. 2009. Accessing retailer equity through integration in retailers’ buying groups. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 37 (1):43–62. doi:10.1108/09590550910927153.

- Hofer, A. R., A. M. Knemeyer, and P. R. Murphy. 2012. The roles of procedural and distributive justice in logistics outsourcing relationships. Journal of Business Logistics 33 (3):196–209. doi:10.1111/j.2158-1592.2012.01052.x.

- Homburg, C., M. Klarmann, and J. Schmitt. 2010. Brand awareness in business markets: When is it related to firm performance? International Journal of Research in Marketing 27 (3):201–12. doi:10.1016/j.ijresmar.2010.03.004.

- Hoppner, J. J., D. A. Griffith, and C. Yeo. 2014. The intertwined relationships of power, justice and dependence. European Journal of Marketing 48 (9/10):1690–708. doi:10.1108/EJM-03-2013-0147.

- Jap, S. D., and S. Ganesan. 2000. Control mechanisms and the relationship life cycle: Implications for safeguarding specific investments and developing commitment. Journal of Marketing Research 37 (2):227–45. doi:10.1509/jmkr.37.2.227.18735.

- Jean, R.-J., Z. Deng, D. Kim, and X. Yuan. 2016. Assessing endogeneity issues in international marketing research. International Marketing Review 33 (3):483–512. doi:10.1108/IMR-02-2015-0020.

- Jia, F., L. Wei, L. Jiang, Z. Hu, and Z. Yang. 2021. Curbing opportunism in marketing channels: The roles of influence strategy and perceived fairness. Journal of Business Research 131:69–80. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.03.039.

- Jin, B., J. Y. Park, and J. Kim. 2008. Cross‐cultural examination of the relationships among firm reputation, e‐satisfaction, e‐trust, and e‐loyalty. International Marketing Review 25 (3):324–37. doi:10.1108/02651330810877243.

- Johnson, J. L. 1999. Strategic integration in industrial distribution channels: Managing the interfirm relationship as a strategic asset. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 27 (1):4–18. doi:10.1177/0092070399271001.

- Joy, V. L., and L. A. Witt. 1992. Delay of gratification as a moderator of the procedural justice distributive justice relationship. Group & Organization Management 17 (3):297–308. doi:10.1177/1059601192173008.

- Kahneman, D. 1992. Reference points, anchors, norms, and mixed feelings. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 51 (2):296–312. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(92)90015-Y.

- Kang, B., and R. P. Jindal. 2015. Opportunism in buyer–seller relationships: Some unexplored antecedents. Journal of Business Research 68 (3):735–42. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.07.009.

- Kaynak, R., T. Sert, G. Sert, and B. Akyuz. 2015. Supply chain unethical behaviors and continuity of relationship: Using the PLS approach for testing moderation effects of inter-organizational justice. International Journal of Production Economics 162:83–91. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2015.01.010.

- Kennedy, A.-M. 2016. Re-imagining retailers’ co-operatives. The International Review of Retail, Distribution & Consumer Research 26 (3):304–22. doi:10.1080/09593969.2015.1096809.

- Kim, C., M. Miao, and B. Hu. 2022. Relations between merchandising information orientation, strategic integration and retail performance. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 50 (1):18–35. doi:10.1108/IJRDM-07-2020-0244.

- Kim, C., and K. Takashima. 2019. Effects of retail organisation design on improving private label merchandising. European Journal of Marketing 53 (12):2582–603. doi:10.1108/EJM-03-2018-0194.

- Konovsky, M. A. 2000. Understanding procedural justice and its impact on business organizations. Journal of Management 26 (3):489–511. doi:10.1177/014920630002600306.

- Korsgaard, M. A., D. M. Schweiger, and H. J. Sapienza. 1995. Building commitment, attachment, and trust in strategic decision-making teams: The role of procedural justice. Academy of Management Journal 38 (1):60–84. doi:10.2307/256728.

- Kumar, V., T. R. Bohling, and R. N. Ladda. 2003. Antecedents and consequences of relationship intention: Implications for transaction and relationship marketing. Industrial Marketing Management 32 (8):667–76. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2003.06.007.