ABSTRACT

This article explores the impact of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on party-system dynamics in Russia by analyzing the war-related communication of the five main “systemic opposition” parties, their leaders, and three Communist MPs who initially criticized the invasion. Examining their adoption of established pro-war regime propaganda (anti-Ukrainian, anti-Western, “Z-talk”) or anti-war rhetoric, we assess the extent of rhetorical convergence in the party system. Based on a dictionary analysis of over 60,000 posts between February 2021 and February 2023, we find the Communist Party to be the most proactive in its pro-war jingoism, Just Russia leader Sergey Mironov to be the clearest case of a regime mouthpiece for Z-talk, and only Yabloko to provide weak but consistent dissent, while New People and the three Communist MPs avoid both pro-war and anti-war rhetoric. Our findings indicate a functional reconfiguration of the party system, stopping short of full-fledged rhetorical harmonization toward “GDR-ization.”

Introduction

With its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia’s political leadership set the country on a path of both sudden and creeping but fundamental change. This had an immediate impact on the country’s foreign relations, including a complete rupture of its already tense relations with the West and with Ukraine, and unprecedented shifts in its economic relations, including its resource exports. But the change also engulfed the domestic front. The stabilization of the country’s finances amidst the comprehensive economic sanctions surprised many observers but comes at a very high long-term cost that means reduced scope for spending on patronage and social cohesion, while returning veterans bring trauma and violence into thousands of homes. In terms of regime-opposition relations, the full-scale invasion accelerates and intensifies a trend that had been ongoing for several years: the creeping transformation of Russia’s modern, “informational” authoritarianism (Guriev and Treisman Citation2022) – a system in which leaders rule through persuasion and manipulation – into a more classical authoritarian regime (Dollbaum, Lallouet, and Noble Citation2021), where sophisticated schemes to shape public opinion and tinker with the political supply side give way to overt repression. It could be expected that such fundamental change would not leave the Russian party system untouched. Forged in the era of “managed democracy” in Putin’s early years as president (March Citation2009; Robertson Citation2009), the carefully curated composition of formally independent “systemic opposition” parties formed an important part of a system that created a façade of choice and (controlled) dissent. Entering an era of forced unification through aggressive propaganda and amplified repression, we may legitimately ask whether such an institution still has a place in today’s Russia. In particular, the question would be to what extent the war would erase, change, or maintain meaningful differences between the systemic opposition parties in their positioning and messaging on the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, including the extent to which they adopt the regime’s highly recognizable pro-war propaganda and justificatory tropes.

Addressing this question may yield insights not least into the nature of Russia’s changing political system in the aftermath of the epochal event that is the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine. If Russia’s formally multi-party system under the authoritarian rule of Putin (briefly also in tandem with Dmitry Medvedev) has broadly oscillated “between Mexico and the GDR” (Gel’man Citation2008), the scenario of “GDR-ization” with fully regime-loyal parties that are distinct only in name has become an ever more real prospect under wartime conditions, with the leaders of Just Russia and the Liberal Democratic Party even openly floating the idea of merging into a unity party (Pertsev Citation2023). By examining the extent of rhetorical convergence in the systemic opposition parties’ war-related communication, we can establish to what extent something like “GDR-ization” is indeed happening in relation to the key issue of the regime’s war effort and thus to what extent the political system as a whole is developing in the direction of erasure of meaningful difference between the various parties. More generally, our study sheds light on the variations in party positions that can emerge within the fairly unique constellation of an autocratic regime with a formally multi-party system in relation to a full-scale war of aggression launched by that state.

Despite the uniqueness of the case in question, it can still contribute to understanding more general behavioural patterns of formal opposition actors in an authoritarian multi-party system. Regimes with ruling parties have long been found to be more stable than personalistic or military regimes (Geddes Citation1999), but the neo-institutionalist literature also sees a function for opposition parties in stabilizing authoritarian rule. Regimes use opposition parties to create the impression of pluralism (Schedler Citation2006) and to co-opt opposition groups by (1) offering them limited access to the policy process (Gandhi Citation2008) and (2) supplying their leaders with opportunities for career development and self-enrichment (Ezrow and Frantz Citation2011; Gandhi and Lust-Okar Citation2009, 410). In exchange, authorities expect these groups to withhold their mobilizational capacity when required. In addition, allowing only some groups access to the regime’s institutions creates “divided structures of contestation” (Lust-Okar Citation2005, 65) that can fragment the opposition (Arriola, Devaro, and Meng Citation2021). Empirical tests of the causal mechanisms behind these arguments have been based on parliamentary queries (Malesky and Schuler Citation2010), party affiliations (Golosov Citation2014), or protest mobilization (Dollbaum Citation2017; Reuter and Robertson Citation2015). Public communication as an important element of parties’ strategic behaviour offers an additional way to study the mechanisms of legitimation and co-optation in authoritarian multi-party systems.

In combining these wider interests with our focus on the specific development of the Russian political system, we take into account the nuances of the Russian experience by considering the nature and trajectories of the systemic opposition parties in order to formulate expectations regarding the positions they might be expected to take on the war. Against this background, we examine the extent to which these parties and their leaders adopted the regime framing of the invasion by deploying a dictionary approach. We capture different facets of war propaganda and measure the frequency with which these terms appeared in these parties’ and their leaders’ public communication of over 60,000 social media posts and website entries, totaling over 15 million tokens, published in the first year after and (as a frame of reference) the year before the full-scale invasion starting on 24 February 2022. A dictionary approach is particularly suitable for examining the extent of formally oppositional actors’ adoption of Russian state propaganda on the war given the tightly controlled nature of the domestic information space under wartime conditions – with the very use of terms such as “war” and “invasion” providing grounds for criminal prosecution – in addition to the emergence of recognizable tropes of pro-war propaganda in the information space, from derogatory terms (“Ukrofascists,” “Anglosacks”) and justificatory concepts (“demilitarization,” “denazification”) to the emergence of distinct symbols (the “Z”), the very use of which may indicate varying degrees of endorsement of regime framing of the invasion by formally independent actors (see Alyukov, Kunilovskaya, and Semenov Citation2022a, Citation2022b for analyses of war propaganda in the media and on social media). Our approach is one of few contributions thus far that use fine-grained behavioural indicators – in our case online communication – to study the domestic political reactions within Russia to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

In the following, the paper proceeds in four main steps. First, we draw on existing secondary literature to formulate expectations on the positions that systemic opposition parties may be expected to take (as well as the differences among them). Second, we outline our data corpus and methodological framework, including the dictionaries developed for the analysis. Third, we present the results of the analysis, from the differences across dictionary categories between the parties to shifts over time. Fourth, we discuss the results and foreground in particular two dimensions – a jingoism scale and the degree of proactivity/reactivity – for classifying the systemic opposition parties’ messaging. Our analysis shows that, while none of the five systemic opposition parties except Yabloko engages in anti-war rhetoric, some notable differences emerge, such as the proactively anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western rhetoric of the KPRF, which displays levels well higher than those of the other parties in the year before the full-scale invasion, and the embracing of Z-talk by Just Russia and especially its leader Sergey Mironov in assuming the function of a full-fledged mouthpiece of the regime. These differences suggest that, while full-fledged “GDR-ization” in the sense of thoroughgoing harmonization in rhetorical patterns of all opposition parties has not taken place, all of these parties except Yabloko have settled into a functional differentiation when it comes to how (and to what extent) pro-war positions are communicated in the domestic political space.

“Systemic opposition” parties in Russia: an overview

As a starting point, the term “systemic opposition” can be understood to encompass the relatively narrow set of political organizations in Russia enjoying institutionally recognized status as registered political parties and regularly contesting legislative elections to the State Duma as well as (to varying degrees) local and regional-level elections (e.g. Dollbaum Citation2017; Gel’man Citation2015). In the context of the emergence of United Russia (ER) in the early 2000s as a clear-cut, vertically integrated “party of power” supporting the authoritarian presidency of Vladimir Putin (Reuter Citation2017), the notion of “systemic opposition” came to refer to a “dying species” (Gel’man Citation2005) of non-ER parties inhabiting the shrinking space for political competition, from the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (KPRF) to the ultranationalist Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR) to the social-liberal Yabloko and the conservative-liberal Union of Right Forces (SPS). The KPRF and LDPR, with their longtime leaders Gennady Zyuganov and Vladimir Zhirinovsky, respectively, were leading fixtures of party politics during Boris Yeltsin’s presidency in the 1990s, with the KPRF finishing as the largest party in the 1995 and 1999 Duma elections. The formation of ER in 2001 signaled a far-reaching process of elite consolidation and co-optation, absorbing the various blocs of local and regional executive power holders organized around Unity and Fatherland (the two parties that finished behind the KPRF in the 1999 Duma elections). The authoritarian consolidation of the party-competitive space in the 2000s saw Yabloko and SPS falling out of contention in Duma elections, while Zhirinovsky’s LDPR and the Kremlin-created centre-left party Just Russia (SR) (March Citation2009) led by Putin’s old acquaintance Sergei Mironov took on the function of de facto regime-loyal parties supporting the Kremlin’s initiatives in the Duma. As the barriers of entry to new party-political actors have increased (such as with the requirements for new party registration and the raising of the threshold for proportional representation to 7%, albeit reduced to 5% after the 2011 elections), there has been little turnover in the party composition of the Duma. Accordingly, Smyth and Gill (Citation2022) calls the party system “frozen.” New People (NL), a Kremlin-sponsored spoiler party positioning itself as a business-oriented centre-right force (Smyth Citation2022), became a rare addition when it entered the Duma with 5.3% in the 2021 legislative elections. KPRF, SR, LDPR, and NL are the four systemic opposition parties currently represented in the Duma by virtue of having cleared the 5% threshold in the 2021 elections; in our study, we examine these four parties and their leaders in addition to Yabloko, which was represented in the Duma from 1993 to 2007 and continues to have a certain degree of visibility as an officially registered and recognized party with representation in several regional assemblies (including its relative stronghold of Moscow) as well as vote shares fluctuating between 1 and 4% according to official results in Duma elections.

The existing literature on the systemic opposition to ER and Putin has classified these parties along a continuum of proximity to or distance from the Kremlin (Gel’man Citation2005, Citation2008, Citation2015; White Citation2012). Following Gel’man’s (Citation2005) initial classification, the KPRF and Yabloko were situated between “principal opposition” and “semi-opposition,” oscillating between bargaining with the regime on the one hand (e.g. the KPRF in the 1999–2003 legislature, which helped it retain the Duma presidency and numerous committee chairs) and holding up the flame of opposition with at times radical rhetoric under conditions of exclusion from institutional power on the other (an analysis largely confirmed with additional nuances by Dollbaum Citation2017; Gel’man Citation2008, Citation2015; White Citation2012).Footnote1 At the other end of the spectrum, LDPR and SR have been classified as “satellite parties,” lending more or less full legislative backing to the president (combined with occasional token criticism of United Russia) and providing a façade of political opposition with their ultranationalist and socialist rhetoric, respectively (Gel’man Citation2008; White Citation2012). The origins of both parties reflect their status as variously state-initiated products of “political technology”: the LDPR was engineered as a state-controlled pseudo-opposition party toward the end of the Soviet Union and SR was conceived as a second “party of power” or even the “left leg” to ER during Putin’s second presidential term. In this vein, NL can likewise be situated as the latest Kremlin-sponsored spoiler party – in this case with an outwardly liberal and entrepreneurial image – created and granted registration by the authorities in 2020 (Smyth Citation2022).

In addition to this established dimension of proximity to or distance from the authoritarian regime, an additional aspect of relevance for our considerations is the extent to which these parties had established track records of imperialist, nationalist, and anti-Western position-taking, especially in the context of Russian military intervention in Ukraine since 2014. Korgunyuk (Citation2017) has shown that following the 2014 Russian invasion and annexation of Crimea, the primary dividing line in Russian party politics became that of imperialist/anti-Western against anti-imperialist/pro-Western, with KPRF, LDPR, and SR concentrated on the far end of the first camp and Yabloko holding its ground in the second. While Korgunyuk’s analysis situates the emergence of this “cleavage” in its own right in 2014, these parties each had an established history of taking such positions. At one extreme, the LDPR had long been known for its aggressive nationalist rhetoric since the 1990s, with far-fetched and headline-grabbing rhetoric by Zhirinovsky calling for the restoration of imperial Russian territorial possessions, the expulsion of “foreign” peoples from Russia, and irredentist saber-rattling in the name of protecting Russian-speaking populations in former Soviet republics such as the Baltic states and Ukraine. In sum, the LDPR’s ultranationalism has been known to encompass domestic racism and xenophobia on the one hand (Laruelle Citation2014) as well as a stridently anti-Western and “imperialist”-irredentist foreign policy on the other (Korgunyuk Citation2011). The KPRF, while seemingly representing the opposite historical pole of the red/white or communist/monarchist divide, has always featured a social-conservative and Russian nationalist strain of Soviet nostalgia (Korgunyuk Citation2017; Levintova Citation2011; March Citation2002; Sakwa Citation2012), incorporating themes such as not only large-scale nationalizations and investment in public services, but also the restoration of Soviet-era geopolitical greatness, celebration of traditional Russian culture against Western influences, and proximity to the Orthodox Church. LDPR and, to a less drastic extent, KPRF thus belonged to the anti-Western Greater Russia nationalist end of the spectrum well before 2014. In the case of SR, the 2014 annexation of Crimea and the party’s absorption of Patriots of Russia and For Truth in 2021, which made former National Bolshevik activist and ultranationalist writer Zakhar Prilepin vice-chairman and a prominent voice within SR, have signaled an increasing prominence of ultranationalist positions taken by Mironov’s party as well, albeit with a less established track record than LDPR and KPRF. Notably, Korgunyuk’s (Citation2017) factor analysis based on 2016 Duma election campaign materials situated SR slightly ahead of the KPRF, in turn slightly ahead of the LDPR, in their respective placements on the anti-Western and imperialist end of the spectrum, in contrast to the pro-Western and anti-imperialist Yabloko.

The KPRF, LDPR, and SR all firmly supported the 2014 annexation of Crimea, with the sole vote against it in the Duma coming from SR MP Ilya Ponomarev, who was subsequently forced to leave the country (and has since become a prominent anti-Kremlin voice in Ukrainian exile). Indeed, the invasion and annexation of Crimea became a rallying point around which all major systemic opposition parties – with the exception of the extra-parliamentary Yabloko, which was against – unwaveringly backed the Kremlin’s aggressive foreign policy against Ukraine, including the Russian-backed separatist insurgency in the Donbas (Korgunyuk Citation2017). This was the case in spite of varying degrees of opposition to the Kremlin on social and economic policy, especially from the KPRF with its participation in protest mobilizations against the Platon toll system for truckers or the pension reform that raised the retirement age (Dollbaum Citation2021). In the run-up to the February 2022 invasion as well, with recent legislative elections in the rearview mirror, all parties in the Duma rallied around the Kremlin’s course and voted for the recognition of the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics – with the notable exception of NL, which voted against. Ever since the beginning of Russian aggression against Ukraine in 2014, therefore, there is a clear pattern of at least the KPRF, LDPR, and SR rallying behind a pro-Kremlin “patriotic consensus” on foreign policy, in addition to these parties’ varying degrees of long-standing anti-Western, irredentist Russian nationalism.

“Systemic opposition” under wartime conditions: some initial considerations

In light of this background, what general expectations can we develop regarding the stances adopted by these “systemic opposition” parties under conditions of full-scale war launched by the Russian state against Ukraine? We have identified two dimensions of relevance for formulating initial expectations regarding the positions taken by these parties on the invasion: (1) proximity to or distance from the Kremlin in the context of Russia’s highly stage-managed multi-party system; (2) the track record of anti-Western, imperialist, and Russian nationalist position-taking, especially within the wider arc of the Kremlin’s aggressive foreign policy against Ukraine since 2014. This latter dimension becomes all the more relevant in light of studies that have shown the prominent interplay of anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western tropes in the information conditions as well as justificatory tropes set by the regime both during and in the run-up to the full-scale invasion (see, for example, Alyukov, Kunilovskaya, and Semenov Citation2022a, Citation2022b on war propaganda in Russian media and Onuch and Hale Citation2022 for a content analysis of Putin’s 21 February and 24 February 2022 speeches).

In addition to the orientations of individual parties, we may also be able to formulate expectations about the overall relational dynamics of the party system as a whole: whether, for example, the parties develop in the direction of uniformization and loss of positional autonomy under wartime conditions. Gel’man (Citation2008) had situated the Russian party system at the tail end of Putin’s first two presidential terms as somewhere “between Mexico and the GDR” (“Mexico” here referring to the period of uninterrupted decades-long rule by the Institutional Revolutionary Party and “GDR” to the German Democratic Republic): between a semi-authoritarian dominant-party system tolerating independently operating opposition parties on the one hand and an openly repressive autocracy with firmly regime-loyal “bloc parties” on the other. Indeed, recent instances of LDPR and SR leaders openly floating the idea of merging the parties in the Duma into a “unity party” during the war would point in the direction of (and even exceeding) this GDR-ization scenario (Pertsev Citation2023); the question for our analysis would be to what extent our background knowledge of Russian party politics up to 24 February 2022 would lead us to expect the parties’ positions on the war to converge in the direction of greater uniformity. While our analysis does not cover issue areas beyond our war-related dictionary (see Methods section), the minimum criterion for GDR-ization would be rhetorical convergence around the adoption of regime propaganda in relation to the invasion of Ukraine as a defining issue in Russian political life and, indeed, a key indicator of regime loyalty in the current context.

In this context, we formulate our first general expectation for the analysis as follows. When it comes to the adoption of anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western rhetorical tropes in the context of the full-scale invasion, we would expect the extent of such rhetoric to align with the imperialist/anti-Western vs. anti-imperialist/pro-Western continuum. The LDPR, to begin with, can be expected to be at the forefront given its long-standing history of both irredentist ultranationalism and functioning as a satellite party backing the Kremlin’s initiatives, not least in the area of foreign policy against Ukraine. The same applies in effect for SR given its high degree of proximity to the regime and, since the 2014 annexation of Crimea and 2021 mergers at the latest, its prominent adoption of an aggressively nationalist profile. While the KPRF has been classified as more distant and independent from the Kremlin, its adoption of a Russian nationalist profile is well established, especially in the context of Kremlin foreign policy against Ukraine, which leads us to expect a high level of anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western war-related rhetoric on par with LDPR and SR. For all the differences between these three parties in terms of regime proximity, the adoption of anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western rhetoric in support of the war can be expected to be a point of convergence between them from the very beginning of the invasion. Conversely, we can expect Yabloko to not only display low levels of such rhetoric, but also to persist in being the sole party to oppose Russian aggression against Ukraine, continuing its clearly established profile of relatively principled opposition to the Kremlin as well as generally anti-imperialist and pro-Western stances. NL is something of an unknown quantity given its much shorter history; while it opposed the recognition of the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics, there are clear indications that the party is, in effect, a Kremlin satellite as previously noted. At the same time, given its function as an outwardly liberal and non-nationalist regime-loyal opposition, it is entirely conceivable that avoiding the anti-Western and anti-Ukrainian rhetoric of the other parties (while also staying clear of open anti-war dissent) allows the party to enact this role of a Kremlin satellite tasked with staking out a liberal and entrepreneurial position within the regime-loyal camp. Therefore, we expect that NL will display low levels of anti-Western and anti-Ukrainian rhetoric while, at the same time, avoiding anti-war positions.

Another set of expectations relates to the extent of systemic opposition parties’ adoption of pro-war regime propaganda designed to develop a positive identification with the war effort, on top of the negative anti-Western and anti-Ukrainian messaging. We might refer to this positive dimension as “Z-talk”: the emergence of new symbols such as the “Z” and motivational slogans such as “Victory will be ours” or “We do not abandon our own.” When it comes to the adoption of this kind of highly top-down, regimented pro-war propaganda neologisms designed to popularize the invasion in the public sphere, we expect the field to be somewhat more complex in light of the differing classifications of these parties along the dimension of regime proximity/distance. Given the KPRF’s established track record of greater distance from the regime, we would expect that it would at least try to maintain a pretense of greater rhetorical autonomy even while firmly backing the Russian invasion of Ukraine and faithfully adopting anti-Western and anti-Ukrainian tropes. One indication of this might consist in differing degrees of adoption of Z-talk, with LDPR and SR displaying the highest levels, followed by the KPRF, while Yabloko will avoid it altogether. NL again presents an interestingly ambivalent case: while we expect it to not adopt much in the way of anti-Western and anti-Ukrainian rhetoric, we would expect it to take up the regime’s Z-talk by virtue of its satellite function. In other words, we expect the extent of adoption of Z-talk propaganda to align with the dimension of proximity to or distance from the regime: LDPR, SR, and NL will display high levels of “Z-talk” propaganda, followed by the KPRF, while Yabloko will avoid it altogether.Footnote2

Given that the war has arguably become the defining issue in Russian politics for the foreseeable future, our results might hold indications for the development of the authoritarian party system more generally. If the foregoing expectations formulated on the basis of the parties’ pre-war behaviour were to be confirmed, this would indicate that the systemic opposition parties would be positioning themselves in accordance with their established individual profiles and, in effect, continuing their pre-war trajectories even after the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine. If, on the other hand, these parties start moving away from these established trajectories after the beginning of the invasion and we observe rhetorical convergence over time toward official propaganda tropes at least among the four Duma parties, this would suggest that we might be witnessing substantive change in the set-up of the Russian system of “systemic opposition” parties as a whole, perhaps in the direction of something like “GDR-ization” whereby KPRF, LDPR, SR, and NL take on the function of “bloc parties” with more or less total conformity in terms of regime loyalty. Whereas we previously formulated the expectation that NL, for instance, would adopt Z-talk but eschew anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western rhetoric, the uniformization scenario would be one in which even NL – as the parliamentary party that is decidedly least likely to adopt anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western tropes based on its pre-invasion profile – embraces high levels of anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western rhetoric in addition to Z-talk, thus pointing to a dynamic of all Duma parties falling into line behind regime propaganda.

In addition to differences between the parties in national office as reflected by their official websites and social media communication, we conduct the same analysis for the leaders of the five parties as well as the leader of United Russia, ex-president Dmitry Medvedev. In addition, we include three KPRF MPs (and the only Duma members in this regard) who are known to have initially positioned themselves against the full-scale invasion: Vyacheslav Markhaev, Mikhail Matveev, and Oleg Smolin. Including these three MPs in the analysis can thus shed light on how the communication practices of the lone federal public officeholders who (at least initially) openly questioned the invasion square with those of their own party and to what extent they indeed adopt anti-war rhetorical tropes following our dictionary. Examining the extent of anti-war dissent from these three Duma representatives for the KPRF is worthwhile not least in light of sporadic instances of anti-war dissent from politicians and activists from the rank and file as well as regional branches of the party, which are otherwise not covered by our analysis centred on the party in national office. When it comes to examining the extent of rhetorical harmonization among the systemic opposition parties as a minimal condition for possible GDR-ization, the three initial KPRF dissenters constitute least likely cases of such harmonization, making any adoption of pro-war propaganda on their part particularly meaningful.

To summarize our expectations:

We expect the extent of adoption of anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western tropes to vary based on the systemic opposition parties’ established records of position-taking along the imperialist/anti-Western vs. anti-imperialist/pro-Western continuum (including in relation to Russian aggression in Ukraine since 2014). As such, we expect high wartime levels of such rhetoric from KPRF, LDPR, and SR, low levels coupled with an avoidance of anti-war rhetoric from NL, and a high level of anti-war rhetoric coupled with an avoidance of anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western rhetoric from Yabloko.

We expect the extent of adoption of Z-talk to be a function of regime proximity, such that high levels can be expected from LDPR, SR, and NL followed by the KPRF, with Yabloko avoiding such rhetoric altogether.

Data, methods, and operationalization

In order to capture a sufficient share of the war-related public communication of systemic opposition parties, their leaders, and selected critical MPs, we analyze both their websites and their social media channels.Footnote3 In terms of social media, we focus on VKontakte (VK) and Telegram as the two most common outlets in the Russian context. VK, commonly referred to as the Russian equivalent of Facebook, has been highly popular for many years and continues to be one of the most used social media platforms, especially in the Russian regions. In March 2023, a Levada poll showed that 66% of respondents use VK (Levada Center Citation2023). Owned by Alisher Usmanov’s Mail.ru group since 2014, VK has been rumoured to provide user details to the secret services and is therefore considered unsafe by regime critics. Telegram, by contrast, has turned into the most important messenger for Russian (and not only Russian) dissidents, due to founder and owner Pavel Durov’s categorical refusal to collaborate with law enforcement agencies. Recently, the use of Telegram has expanded as authorities blocked many critical news websites that now operate through the messenger service instead (see Levada Center Citation2023). In addition to offering an almost complete coverage of our five opposition parties plus ER and 10 individuals (the only exception is the KPRF, which has no Telegram channel), this choice therefore allows an efficient check on whether the rhetoric differs across these two channels that arguably have rather different audiences and provide different affordances (see also Dollbaum Citation2021). We provide such robustness checks in the online Appendix.

We scraped all posts by the 16 actors on VK and Telegram published between 24 February 2021 and 24 February 2023 – one year before and one year after the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion. We then added the complete body of press releases and official statements published on their websites for the same period (for details of the process see online Appendix A). The resulting corpus consists of 60,798 posts.Footnote4 As shown in Table A1 in the online Appendix, this number is distributed unequally across the 16 parties and individuals. United Russia tops the list with 18,708 posts or 31% of the total corpus, while NL has the fewest posts of the five parties with 1,541 or 2.6% of the corpus. A similar discrepancy exists between the KPRF’s deputy Vyacheslav Markhaev (189 posts) and SR’s leader Sergey Mironov (7,529 posts), which likely reflects differences in resources devoted to public communication. As shown below, we circumvent this unbalanced distribution by focusing on the relative shares of the different speech categories within the communication of each actor.

After replacing URLs in Latin script with the generic term “URL” to exclude as many latin letters “z” as possible and thus to limit false positives on the “Z-Talk” category, the full corpus contains 801,000 sentences and over 15 million tokens. With hand-coding of the material thus ruled out, our main method of analysis is the quantitative comparison of terms and collocations across parties using a dictionary approach (Stone et al. Citation1966). This method relies on pre-specified words and phrases manually curated by researchers. The computer identifies these phrases across the corpus and marks posts accordingly as belonging or not belonging to the respective category (Guo et al. Citation2016). In comparison to a machine learning classifier (be it an unsupervised method such as topic modeling or a supervised method such as a large language model refined with training data), the dictionary approach is less inclusive but more accurate. In relation to the task at hand – to identify the share of certain themes among the parties’ overall online communication – one can think of a dictionary approach as maximizing precision at the expense of recall: it identifies 100% of the targeted phrases while generating few false positives, but it does not capture thematically related content that is expressed in other terms than those specified in the dictionary. We consider this an acceptable trade-off because we are most interested in identifying to what degree parties and politicians use specific and established rhetorical devices that permeate the discursive space of Russian party politics – anti-Ukrainian, anti-Western, anti-war, and “Z-Talk” phrases – thus making the dictionary approach suitable for the purpose of our analysis. Still, in a dictionary approach, the results can vary strongly with the selection of single terms. To address concerns that our results depend on our concrete specification (even if well justified), we run two robustness checks, each time randomly excluding 20% of terms from the dictionaries, finding that the results are virtually identical in substance (see online Appendix G).

We constructed the dictionary around four categories (see ), as they shed light on distinct (if interconnected) aspects of pro-war regime propaganda, drawing also on studies in the existing literature on rhetorical tropes surrounding the invasion such as Alyukov, Kunilovskaya and Semenov’s (Citation2022b) analysis of war-related discourse on Russian social media and Onuch and Hale’s (Citation2022) content analysis of Putin’s speeches on 21 and 24 February 2022. Onuch and Hale show that in these two speeches directly justifying Russia’s decision to invade Ukraine, the notion of recent “NATO and Western aggression” in conjunction with an image of Ukraine as a creation of Lenin’s supposed historical error of caving in to Ukrainian “nationalists” and as a currently “Nazi/Nazism”-dominated state was central to Putin’s justificatory narrative. In our dictionary, anti-Ukrainian rhetoric refers to this equating of Ukraine-ness with “nationalists” and “Nazis” (including defamatory neologisms such as “Ukronationalist” and “Ukrofascist”), whereas anti-Western rhetoric is centred on notions of Western expansion and aggression directed specifically against Russia (e.g. “NATO expansion,” “the collective West”). In addition to these separate but closely interlinked aspects, what we refer to as “Z-talk” consists of propaganda neologisms expressly coined by the regime after the beginning of the full-scale invasion to create positive domestic identification with the war effort, centred on the letter “Z” and derived terms (such as “For victory” with the Latin “Z” in “Za,” “We do not abandon our own”). Finally, the category of anti-war rhetoric takes up mobilizing slogans widely used in anti-war protests and social media activity, such as “No to war,” “Against the war,” etc.

Table 1. Dictionary categories for invasion-related statements.

Overall, 10.5% of the corpus contains at least one of the words or phrases specified in the dictionary. If divided into one-year periods before and after the beginning of the invasion, the shares stand at 2.7% and 16.5%, showing that our dictionary captures a substantive share of the parties’ overall communication and that, while some actors espoused terms included in the dictionary before Russia’s attack, the invasion clearly catalyzed the adoption of the rhetoric we measure. Both observations underline that we capture an empirically meaningful phenomenon.

In the following, we compare the share that a particular category occupies in a party’s or politician’s overall communication to the corresponding share of the other parties and politicians. This acknowledges that, depending on funds and strategic calculations, actors may direct different resources to their outside communication. Focusing on the relative frequency of categories for each actor separately, we thereby control for the absolute number of posts that, as shown above, strongly differs across parties and politicians. We now proceed to an analysis of the quantitative data. Where appropriate, we describe the results of qualitative validity checks.

Analysis

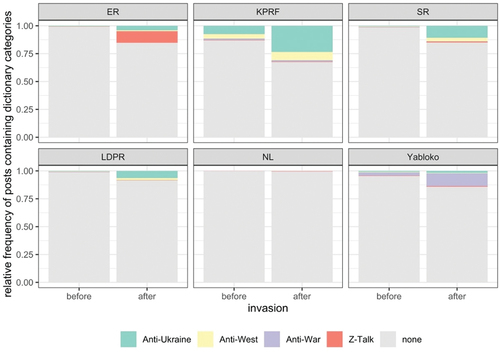

We begin by graphically comparing the shares of all five systemic opposition parties and the dominant party before and after the invasion. plots the relative frequency of posts that contain the dictionary categories. Some of the patterns unfold as expected, whereas others are more surprising. First, there are clear differences in the categories across actors. United Russia, perhaps surprisingly, uses less anti-Ukrainian and less anti-Western rhetoric than the KPRF, LDPR, and SR as a percentage of its total communication. Instead, it almost exclusively focuses on “Z-Talk,” pushing the regime’s PR campaign to create positive identification with the war. In contrast, the systemic opposition parties do not engage in much Z-Talk, with the partial exception of SR.

Figure 1. Shares of dictionary categories among overall communication, by party and time period.

Second, within the systemic opposition, the KPRF comes out clearly as the party that uses the most anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western tropes as a share of its overall communication. There are also 58 instances of anti-war messaging, but a qualitative validity check shows that none of these should be taken as criticism of the invasion. They can be grouped in two broad categories: (1) citations and denials as well as (2) nationalist appropriations. The first category comprises terms like “Ukraine was allegedly subject to ‘Russian aggression’” (identifying phrase italicized). The second category comprises vocabulary that is usually used to criticize Russia’s invasion (Alyukov, Kunilovskaya, and Semenov Citation2022b) but that the KPRF appropriates in its own nationalist discourse: “The neo-Nazis were aiming to take over Donbass and Crimea” or “we must ensure victory over the Nazi-Bandera mob that has occupied Ukraine,” implying that Ukraine or its government is the real aggressor.

Third, this leaves Yabloko as the only one of the five systemic opposition parties to substantially engage in anti-war rhetoric. Even before the full-scale invasion, Yabloko deployed anti-war slogans in the context of the Russian troop build-up along the Ukrainian border, including an online petition “against war with Ukraine” and a 10-point plan for lasting peace in the Donbas in February 2022. Following the full-scale invasion, the party continued this anti-war course by openly displaying slogans such as “No to war” on its website and releasing statements calling for an “immediate ceasefire” with the withdrawal of Russian troops from Ukraine. In March 2022, however, amid increasing repression of anti-war language in the public sphere within Russia, Yabloko began redacting references to “war” in its statements by replacing the word voina with the letter i (й). This, in turn, may account for at least part of the subsequent decline in anti-war rhetoric in Yabloko’s communication as captured by our dictionary.Footnote5

Fourth, in terms of differences in timing, it is clear that all categories strongly gain in salience in the period of Russia’s “special military operation.” This basic difference in time is true for all parties except New People, which appears to avoid addressing the topic altogether. Here, perhaps the most striking result in this comparison concerns the KPRF, which emerges as the only party with a substantial share of anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western rhetoric—13% of all communication—before the onset of the full-scale invasion, with the share roughly increasing by a factor of 2.5 to 33% thereafter. In contrast, the corresponding shares for SR and the LDPR increase by a factor of 7–10 (see Table D1 in the online Appendix), indicating much lower relative levels before the invasion compared to the KPRF. Yabloko, on the other hand, was proactive with its anti-war slogans before the full-scale invasion – especially in the first 23 days of February 2022, when posts containing anti-war rhetoric made up 25% of its communication.

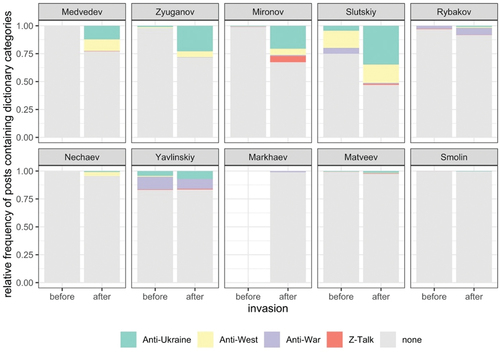

Next, we repeat the analysis for the individual politicians (see ). For the leaders of the systemic opposition parties (and former party leader Grigoriy Yavlinskiy for Yabloko), we observe similar patterns compared to their parties. KPRF leader Zyuganov, SR leader Mironov, and LDPR leader Slutskiy engage in considerable anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western rhetoric after the invasion, on par with – or even exceeding – ER leader Dmitri Medvedev who has made a name for himself with his particularly hawkish (and borderline outlandish) Telegram statements. In contrast to the parties, however, it is in this case Slutskiy who had a history of such rhetorical aggressiveness even before the war (perhaps one reason why he was chosen as new party leader after Vladimir Zhirinovskiy’s death in April 2022).Footnote6 This included statements in February and March 2021 rejecting Ukrainian opposition to the “reintegration” of Crimea into Russia as well as, starting in September 2021, posts denouncing “fake news” about a potential “Russian attack on Ukraine.” Mironov, in addition to his sudden strong anti-Ukrainian communication following the full-scale invasion, also took up a considerable amount of Z-Talk, with 5.6% of all his posts after the invasion mentioning at least one of the propaganda terms, making Slutskiy a distant second in this category. Furthermore, Mironov shows the largest increase of rhetoric measured with our dictionary, moving from 1.0% of posts before the invasion to 32.6% thereafter – a 32-fold increase (see Table D1). Finally, the two Yabloko politicians again are the only ones to substantively engage in anti-war statements, while Nechaev, leader of New People, largely avoids the topics – though less so than his party.

Figure 2. Shares of dictionary categories among overall communication, by party and time period.

The last three panels in show the results for the three KPRF deputies, who voiced some early criticism of the invasion: Markhaev (who only started his social media channels in March 2022), Matveev, and Smolin. In contrast to their party and their leader Zyuganov, they make virtually no use of the pro-war dictionary terms. However, they also do not engage in any measurable anti-war messaging, in contrast to the much more outspoken Yabloko politicians. While the three thus clearly do not join the pro-war choir of their party, it would also not be appropriate to call them “dissidents.”

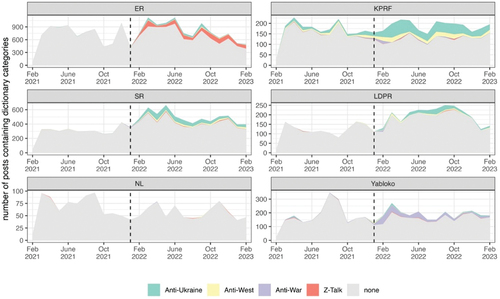

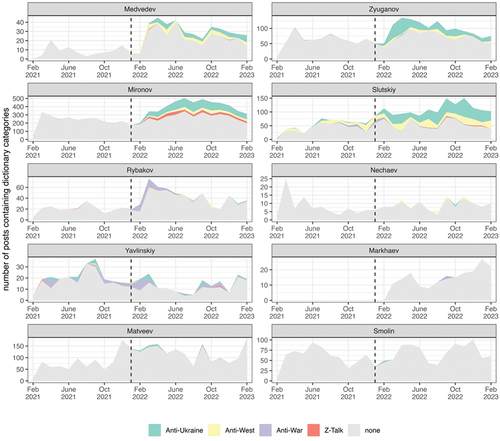

In a second step, plot the posts over time aggregated by month, which yields several additional insights. displays the parties, while shows the politicians, with the vertical dashed line separating the plots into the period before and after the beginning of the invasion. These figures additionally bring out five observations. First, the KPRF’s level of anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western messages was constant in the entire year preceding the all-out war with only a slight increase in January 2022. Second, there also appear to be no stark patterns in the ebbs and flows of all actors’ anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western rhetoric after the invasion. Levels remain relatively stable with the exception of Slutskiy who, if anything, appears to be radicalizing. Third, this stability is especially striking for the “Z-Talk” of both United Russia and Sergey Mironov, which makes up a constant stream in their communication throughout the first year of the war. Fourth, the only distribution that shows strong, systematic variation over time is the anti-war category for Yabloko, Yavlinskiy, and Rybakov, all peaking in February-March 2022 and then steadily declining, presumably in response to the repressive legislation introduced to curb critical discussion of the war.

Figure 3. Absolute numbers of posts containing dictionary categories among overall communication, by party over time.

Figure 4. Absolute numbers of posts containing dictionary categories among overall communication, by politician over time.

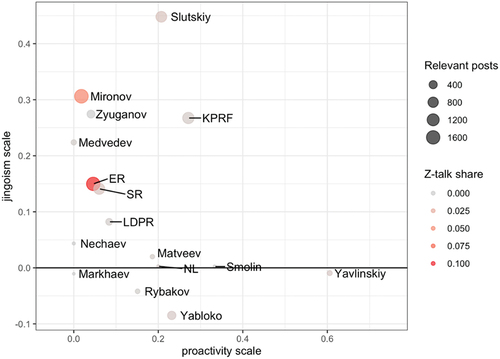

We now proceed toward systematizing these observations by introducing two dimensions and placing the actors on both to attain a spatial picture of the Russian party system in relation to the full-scale invasion, plotted in . The first dimension, “jingoism,” refers to each actor’s share of anti-Ukrainian, anti-Western, Z-talk, and anti-war statements after the invasion. To arrive at our jingoism scale (see online Appendix E for the formulas), we first add the numbers of each actor’s posts that contain anti-Ukrainian, anti-Western, and Z-talk statements and divide the result by the full number of posts (scale 1). We proceed similarly for the anti-war statements (scale 2) and then subtract scale 2 from scale 1. This way, the zero line separates those whose anti-war statements outweigh their pro-war rhetoric (Yabloko, Yavlinskiy, and Rybakov), but also shows the difference within the jingoist camp, with Slutskiy, Mironov, Medvedev, Zyuganov, and the KPRF leading the field.

Figure 5. Two-dimensional space for actors’ messaging on the Russian invasion.

The second dimension, “proactivity,” refers to the quantitative difference of each actor’s posts before and after the invasion. We arrive at it by adding up the posts from all dictionaries issues (anti-Ukraine, anti-West, anti-war, and Z-talk) for the whole two-year period and calculating the share of the pre-invasion posts of this total. The higher this share, the more proactive an actor is, i.e. the more they talked about the issues before the invasion. Conversely, the lower the share, the more radical the change in rhetoric after the invasion, signifying a reactive stance. For instance, shows that Mironov and the KPRF score similarly on jingoism, but the KPRF’s position reflects its substantial anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western output before the invasion, while Mironov is almost exclusively reactive.

Finally, to underscore the conceptual difference between Z-talk on the one hand and anti-Ukrainian/anti-Western statements on the other, we use color grading to display each actor’s share of Z-talk among their overall communication. Here, Mironov clearly stands out among the rest as the only one who comes close to United Russia’s share of pro-war Z-propaganda.Footnote7

To summarize, we see: (1) an (unsurprising) anti-war faction of Yabloko and its leaders, internally differentiated along the proactivity scale; (2) a cluster of actors whose defining feature is their silence on war-related issues, comprising NL and its leader Nechaev as well as the three erstwhile dissident deputies of the KPRF; and (3) a pro-war faction of the other parliamentary factions and their leaders. In this cluster, the individuals are much more aggressive than the parties – with the exception of the KPRF, which not only displays the highest jingoism of all parties, but is also the most proactive. Importantly, however, jingoism does not appear to correlate with Z-talk. Here, Mironov stands out as a clear and solitary case of a full-fledged mouthpiece of the regime.

Discussion

The results point to numerous patterns that have implications for the future development of the Russian party system under conditions of war. First, a distinction can be made between the largely reactive messaging of the established systemic opposition parties and the partly proactive nature of the KPRF’s anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western rhetoric. Especially when compared to the KPRF, the LDPR and SR are characterized by a largely reactive approach to war-related communication as measured by our data, with their shares of anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western rhetoric seeing a sudden spike following the full-scale invasion – perhaps an indication of the regime’s relative lack of systematic preparation of the domestic information space for full-scale war. As illustrates, this post-invasion spike is even more pronounced for the party leaders (Zyuganov, Slutskiy, Mironov). What is notable here is that these three parties’ pro-war communication is oriented toward anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western rhetoric rather than Z-talk, whereas United Russia concentrates on the “positive” Z-talk messaging and largely eschews the antagonism of the three aforementioned parties. In this, KPRF, LDPR, and SR take on a kind of scarecrow function with their aggressively anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western rhetoric, which, however, is largely reactive. Against this backdrop, it is striking how the KPRF emerges as the single most nationalist party in terms of the share of anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western rhetoric in its overall communication, both in the year before and after the full-scale invasion. The proactive nature of the KPRF’s cheerleading for the war can also be seen beyond the context of our analysis in the example of so-called partial mobilization, which the KPRF was the first party to openly advocate at a press conference held by Zyuganov in September 2022. The fact that the KPRF as the largest party of the systemic opposition has proactively advanced anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western tropes even before the full-scale invasion can be considered a boon for the Kremlin in sustaining the domestic information conditions behind its war of aggression against Ukraine.

Second, we can see in the communication practices of New People and the three initially critical KPRF MPs a strategic use of silence that cannot be explained by repression alone. Notably, NL largely avoids anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western rhetoric as well as Z-talk altogether, contrary to our expectation that it would take up Z-talk by virtue of its proximity to the Presidential Administration (an expectation that is borne out in the case of ER as ruling party and Kremlin mouthpiece Mironov, with their high levels of Z-talk). At the same time, it also avoids anti-war rhetoric, with Yabloko being the only one of the five parties with meaningful use of anti-war communication according to our measurement. The case of Yabloko shows that maintaining an openly anti-war profile was possible at least a few months into the full-scale invasion; the subsequent decrease in its use of anti-war language can be read as a response to the trade-off between securing its immediate survival in the context of heightened repression on the one hand and maintaining its principled stance on the other, possibly also with a view to a post-Putin future in which it can claim to be the only systemic opposition party that was against the war from the outset. The strategy of silence or minimalism adopted by NL and the three KPRF “dissidents” points to a different approach to this trade-off, maintaining a low profile on the war practically from the beginning so as to keep their profiles open and adaptable in one direction or the other. This minimalism also means that the NL’s and the three KPRF MPs’ values on the proactivity scale are based on very few observations and, as such, not meaningful in relation to the proactivity/reactivity dimension.

Finally, a notable development is that of SR leader Mironov assuming the function of a full-fledged mouthpiece of the regime, in terms of anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western rhetoric as well as Z-talk. Indeed, Mironov is the only one of the party leaders who systematically adopts Z-talk as a staple of his communication. At the same time, Mironov exhibits the largest increase in anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western rhetoric compared to the period before the invasion, indicating that his pro-war communication is highly reactive rather than proactive. What is also notable is that Mironov displays his Z-Talk almost exclusively on VKontakte (see disaggregation by source in online Appendix C), which suggests a strategic use of VK as a medium through which “the people” can supposedly be reached best; this pattern is the exact same as for ER, suggesting the possibility of coordinated action. Mironov’s highly bellicose rhetoric can be understood as part of SR’s transformation into a frontrunner of jingoistic pro-Kremlin satellite party politics in the context of the war, even more so than the LDPR – a notable development in itself when considering the fact that SR once served as a platform for prominent opposition politicians such as Ilya Ponomarev and Dmitry Gudkov barely a decade prior.

Overall, our results suggest that the full-scale invasion has further limited the systemic opposition parties’ rhetorical independence – as accentuated by the reactive spikes in pro-war propaganda in reaction to the full-scale invasion – accelerating a process that has been underway for almost two decades. However, we do not observe full-fledged GDR-ization, insofar as the parties do not fully converge around the regime’s pro-war rhetoric – especially when it comes to Z-talk, but also in terms of the minimal use of anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western rhetoric by NL and lower-than-expected levels for LDPR and SR.Footnote8 These differences are arguably minor insofar as all of the Duma parties (including NL, even with its lower shares of pro-war rhetoric) stand firmly behind the war and, at the same time, very much meaningful insofar as they point to shifting forms of functional differentiation (albeit highly stage-managed) among the systemic opposition parties as well as between them and ER. The fact that the systemic opposition parties do not fully converge can be interpreted both as a sign that they are maintaining a modicum of rhetorical autonomy and as a way of finding a new functional division of labour within their reduced scope for autonomy, albeit with the roles slightly rearranged – something that has constituted an element of continuity throughout Putin’s presidency and arguably suits regime interests in maintaining a high level of pro-war conformity in the domestic political space behind the façade of a formally multi-party system.

Beyond the insights on the Russian case, we believe the results hold at least three lessons for the research on authoritarian multi-partism more generally. First, they provide insights into how the authorities can use opposition parties to further the regime’s legitimacy that go beyond the appearance of pluralism (Schedler Citation2006) or using them explicitly for procedural legitimacy claims (von Soest and Grauvogel Citation2017). By employing pro-war rhetorical tropes, parties strengthen the impression that the war is not simply a project of the Kremlin but is supported in wider circles of the population. Here, a degree of (real or perceived) independence as manifested by the KPRF is, in fact, beneficial for the regime insofar as it increases the perception of authenticity. Second, the highly aggressive language employed by Leonid Slutskiy, the KPRF, or even Dmitry Medvedev creates a radical foil against which the ruling party and the authoritarian ruler himself can appear moderate and statesmanlike – another possible source of legitimacy.

Third, the analysis sheds new light on co-optation of opposition parties (Gandhi Citation2008; Kavasoglu Citation2022). Rather than thinking of this in binary terms of inclusion/exclusion and loyalty/disloyalty, the results encourage adopting a more nuanced perspective. Evidently, all observed actors adapt to the changing realities. But while, for instance, New People appears to do the bare minimum to survive organizationally, others go above and beyond – particularly Mironov, who openly embraces the regime’s Z-talk propaganda neologisms. Whether they do this to score extra points with the regime in expectation of greater access to spoils or because of higher demands from the Presidential Administration is impossible to know. What our results do show, however, is that observing the public communication of opposition actors is a way to study how these actors interpret their own role in the political system in fine-grained detail (which is also helpful for the regime to check on parties’ current commitments to the co-optation equilibrium).

Finally, there is a methodological aspect. The escalation of repression since the full-scale invasion means that researching Russian politics is becoming increasingly difficult for reasons of deteriorating access and data quality. In this situation, using data directly generated by political actors has important advantages. Political communication is public by nature and is thus not filtered through censored or self-censored media (like protest event data) or regime-controlled electoral commissions (in the case of electoral data), making it more trustworthy than other data that has been used to study opposition party behaviour in authoritarian regimes.

Conclusion

This paper set out to examine the wartime communication practices of Russia’s five main “systemic opposition” parties (KPRF, LDPR, SR, NL, Yabloko) and the extent of their adoption of pro-war regime propaganda in particular, drawing on a combination of official websites and social media activities (Telegram, VKontakte) of these parties and their leaders. To this end, we developed a dictionary encompassing different layers of pro-war propaganda (in addition to anti-war rhetoric) and applied it to our corpus of scraped web posts. We conducted the same analysis for the ruling party United Russia (ER) as a baseline for the other parties. In developing a classificatory scheme of the positions taken by the five systemic opposition parties, we identify two dimensions of relevance: (1) a “jingoism scale” as an aggregate measure of the extent of anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western rhetoric in addition to Z-talk; and (2) a “proactivity scale” measuring the degree of continuity between the communicative patterns observable in the first year of the full-scale invasion and in the year prior.

Our analysis finds that the KPRF has established itself as the most jingoistic (and the most proactively such) party by some distance, even more so than ER along both dimensions, with NL exhibiting minimal levels of jingoism and Yabloko firmly situated on the anti-war side of the spectrum (with a high degree of proactivity that is second only to the KPRF). The KPRF’s emergence as the most proactive party of pro-war jingoism is a notable development, in addition to SR leader Mironov’s embracing of Z-talk (making him the sole party leader to do so) on top of high levels of anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western rhetoric. These differences suggest that, while all of the systemic opposition parties with the consistent exception of Yabloko stand firmly behind the war, some shifts and nuances in functional differentiation across the nominally independent parties can be seen in the context of the full-scale invasion. Gone are the days in which the LDPR could be expected to be the go-to standard-bearer of the most radical jingoist rhetoric, with the KPRF and SR finding ways to distinguish themselves with vehemently anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western orientations (couched in the language of anti-imperialism) or the leader’s active Z-talk cheerleading, respectively. To what extent these parties evolve in their communication in the subsequent phases of the war remains to be seen, but our analysis suggests that all five parties have settled into their roles with different ways of communicating their pro-war (or anti-war in the exceptional case of Yabloko) positions in the domestic informational space.

In light of these considerations, the question what role these systemic opposition parties might play in a post-war Russian political landscape becomes all the more interesting (if speculative). The KPRF’s function as a proactive pro-war party of anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western nationalism, but also one with dissident elements and rhetorical distance from the regime’s Z-talk, suggests that the party may become a key player in whichever direction the outcome of the war and the political dynamics surrounding its settlement may take: whether as a more “respectable” alternative to the Z-brandishing ER and SR or, on the contrary, as a radical opposition to any move toward stopping short of total victory over Ukraine and the West. Indeed, this speculative potential for systemic opposition parties to develop into a radical pro-war opposition to the Kremlin could also be seen with SR, as rumours in late 2022 of Yevgeny Prigozhin’s attempts to commandeer the St. Petersburg branch of the SR illustrate. Yabloko, on the other hand, constitutes the sole party consistently positioning itself as a “party of peace” for a potential post-Putin future, even if this requires painful compromises to avoid being fully banned and dismantled.

It is also worth noting here the limitations of our findings and, at the same time, the avenues for future research that they open up. Our study draws on the official communication of the five main systemic opposition parties at the federal level and is thus centred on the “party in national office” while missing potential variation in the regions. In the KPRF, in particular, there have been notable cases of regional officeholders voicing opposition to the war, such as Yevgeny Stupin in the Moscow City Council and two anti-war parliamentarians in the Primorye Regional Council, all of whom were suspended from the party for their actions. Nonetheless, our study does integrate the three KPRF MPs in the Duma who were known to oppose the full-scale invasion at the beginning and, according to our findings, subsequently de-emphasized or avoided open anti-war dissent entirely. Future research could examine differences in the extent of anti-war dissent within the parties at the regional level and, in the process, identify differing survival strategies of (initial) anti-war dissenters. This may include more indirect or subtle forms of dissent – such as by criticizing the socio-economic consequences of the “special military operation” without deploying openly anti-war slogans – which go beyond the scope of our dictionary and can be captured using machine learning-based methods, for example, of identifying certain rhetorical patterns across multiple policy fields. These and other contributions, for which our systematic analysis at the federal level provides a sound foundation, can collectively shed much-needed light on the domestic political dynamics within the aggressor state in the ongoing war.

Dollbaum_Online_Appendix.docx

Download MS Word (1.6 MB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank colloquium participants at the Research Centre for East European Studies at the University of Bremen for their comments on an earlier draft.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/1060586X.2024.2324628

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. While Yabloko appears at first sight to constitute a more clear-cut case of “principal opposition,” it, too, has been noted for its preference for “loyalty” over “exit” in supporting legislative initiatives of the Presidential Administration as well as its stubborn unwillingness to align itself with more radical or “non-systemic” opposition forces (Gel’man Citation2005, Citation2015).

2. It should be noted that even among actors not necessarily considered structurally close to the regime (e.g. so-called “milbloggers” or “war correspondents”), the choice of adopting Z-talk can be seen as a marker of identification with the regime. Igor Strelkov (Girkin), for instance, eschewed Z-talk in an effort to position himself as a critic of the regime’s conduct of the war.

3. As detailed above, we analyzed the communication of five opposition parties and their current leaders, the regime party United Russia and its current leader, one important Yabloko politician (Yavlinskiy), and three “dissident” Communist MPs, totaling 16 actors. We have scraped former LDPR leader Vladimir Zhirinovskiy’s posts as well, but due to his death shortly after the full-scale invasion, we refrain from a full analysis. We therefore refer to 16 actors in the text.

4. While some actors clearly post very similar content on the three different platforms (VK, Telegram, party websites), the amount of fully identical material is exceedingly low (45 posts).

5. Surprisingly, shows noticeable bands of anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western rhetoric as well as Z-talk for Yabloko. Our qualitative check reveals, however, that these relate to citations or critical mentions rather than genuine uses: In several cases, the party refers to the titles of public events held by authorities that include “Z” or “Za” and also mentions the phrase “we don’t abandon our own” (svoikh ne brosaem) when it reports that intruders shouted it while raiding a Yabloko office in Nizhnii Novgorod. In addition, there are numerous critical mentions of terms used in pro-war propaganda, such as: ‘“We will not abandon our own?’ This slogan is questionable when you see how our state treats its OWN citizens”; “Propaganda and the Kremlin called ‘the threat of NATO’ one of the reasons for the SVO [special military operation].”

6. We found that despite his well-known ostentatious nationalism, Zhirinovskiy hardly used the terms specified in the dictionary in his own communication from the beginning of the full-scale invasion until his death in April 2022.

7. In online appendix E, we reproduce the figure, removing Z-talk from our jingoism scale. The only meaningful difference is the position of ER, which considerably drops on the jingoism scale.

8. We provide a quantitative way to measure rhetorical convergence for our four dictionary categories in online Appendix G. Based on an analysis of how the differences between the parties with regard to their use of the dictionaries change over time, we show a minor tendency towards convergence in the anti-Ukrainian and anti-war dictionary and no such evidence for the anti-Western and Z-talk dictionaries (see Figure G1).

References

- Alyukov, Maksim, Maria Kunilovskaya, and Andrei Semenov. 2022a. “Firehose of (Useless) Propaganda.” Riddle (Blog). July 10. Accessed February 17, 2024. https://ridl.io/firehose-of-useless-propaganda/?fbclid=IwAR3bfGlEMpz84nsYRsyaWdTLnXNoy1JHJ2yonxktRwQAXBOQNsaa1BM_Bg0.

- Alyukov, Maksim, Maria Kunilovskaya, and Andrei Semenov. 2022b. “Putin Fans or Kremlin Bots? War and Mobilisation Across Russian Social Media Platforms.” Re: Russia (Blog). July 11. Accessed February 17, 2024. https://re-russia.net/en/expertise/031/.

- Arriola, Leonardo R., Jed Devaro, and Anne Meng. 2021. “Democratic Subversion: Elite Cooptation and Opposition Fragmentation.” American Political Science Review 115 (4): 1358–1372. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000629.

- Dollbaum, Jan Matti. 2017. “Curbing Protest Through Elite Co-Optation? Regional Protest Mobilization by the Russian Systemic Opposition During the ‘For Fair Elections’ Protests 2011–2012.” Journal of Eurasian Studies 8 (2): 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euras.2017.01.002.

- Dollbaum, Jan Matti. 2021. “Social Policy on Social Media: How Opposition Actors Used Twitter and VKontakte to Oppose the Russian Pension Reform.” Problems of Post-Communism 68 (6): 509–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2020.1800492.

- Dollbaum, Jan Matti, Morvan Lallouet, and Ben Noble. 2021. Navalny: Putin’s Nemesis, Russia’s Future?. London: Hurst.

- Ezrow, Natasha M., and Erica Frantz. 2011. “State Institutions and the Survival of Dictatorships.” Journal of International Affairs 65 (1): 1–13.

- Gandhi, Jennifer. 2008. Political Institutions Under Dictatorship. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Gandhi, Jennifer, and Ellen Lust-Okar. 2009. “Elections Under Authoritarianism.” Annual Review of Political Science 12 (1): 403–422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.060106.095434.

- Geddes, Barbara. 1999. “What Do We Know About Democratization After Twenty Years?” Annual Review of Political Science 2 (1): 115–144. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.2.1.115.

- Gel’man, Vladimir. 2005. “Political Opposition in Russia: A Dying Species?” Post-Soviet Affairs 21 (3): 226–246. https://doi.org/10.2747/1060-586X.21.3.226.

- Gel’man, Vladimir. 2008. “Party Politics in Russia: From Competition to Hierarchy.” Europe-Asia Studies 60 (6): 913–930. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668130802161165.

- Gel’man, Vladimir. 2015. “Political Opposition in Russia: A Troubled Transformation.” Europe-Asia Studies 67 (2): 177–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2014.1001577.

- Golosov, Grigorii V. 2014. “Co-Optation in the Process of Dominant Party System Building: The Case of Russia.” East European Politics 30 (2): 271–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2014.899211.

- Guo, Lei, Chris J. Vargo, Zixuan Pan, Weicong Ding, and Prakash Ishwar. 2016. “Big Social Data Analytics in Journalism and Mass Communication: Comparing Dictionary-Based Text Analysis and Unsupervised Topic Modeling.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 93 (2): 332–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699016639231.

- Guriev, Sergei, and Daniel Treisman. 2022. Spin Dictators: The Changing Face of Tyranny in the 21st Century. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Kavasoglu, Berker. 2022. “Opposition Party Organizational Features, Ideological Orientations, and Elite Co-optation in Electoral Autocracies.” Democratization 29 (4): 634–654. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.1994552.

- Korgunyuk, Yuri. 2011. “Populist Tactics and Populist Rhetoric in Political Parties of Post-Soviet Russia.” Sociedade e Cultura 13 (2): https://doi.org/10.5216/sec.v13i2.13427.

- Korgunyuk, Yuri. 2017. “Classification of Russian Parties.” Russian Politics 2 (3): 255–286. https://doi.org/10.1163/2451-8921-00203001.

- Laruelle, Marlene. 2014. “Alexei Navalny and Challenges in Reconciling ‘Nationalism’ and ‘Liberalism’.” Post-Soviet Affairs 30 (4): 276–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/1060586X.2013.872453.

- Levada Center. 2023. “Auditoriya sotsial’nykh setei i messendzherov [The Audience of Social Networks and Instant Messengers].” April 18. Accessed February 17, 2024. https://www.levada.ru/2023/04/18/auditoriya-sotsialnyh-setej-i-messendzherov/.

- Levintova, Ekaterina. 2011. “Being the Opposition in Contemporary Russia: The Communist Party of the Russian Federation (KPRF) Among Social-Democratic, Marxist–Leninist, and Nationalist–Socialist Discourses.” Party Politics 18 (5): 727–747. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068810389637.

- Lust-Okar, Ellen. 2005. Structuring Conflict in the Arab World: Incumbents, Opponents, and Institutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Malesky, Edmund, and Paul Schuler. 2010. “Nodding or Needling: Analyzing Delegate Responsiveness in an Authoritarian Parliament.” American Political Science Review 104 (3): 482–502. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055410000250.

- March, Luke. 2002. The Communist Party in Post-Soviet Russia. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- March, Luke. 2009. “Managing Opposition in a Hybrid Regime: Just Russia and Parastatal Opposition.” Slavic Review 68 (3): 504–527. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0037677900019707.

- Onuch, Olga, and Henry E. Hale. 2022. The Zelensky Effect. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Pertsev, Andrei. 2023. “Partii bol’she net. Pis’mo o tom, kak Putin vozrozhdaet GDR [There are No More Parties. A Newsletter About How Putin Revives the GDR].” March 3. Accessed February 17, 2024. https://us5.campaign-archive.com/?u=4ea5740c1fe71d71fea4212ee&id=430d8e8e9f&utm_source=Bear+Market+Brief&utm_campaign=a1e4724922-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2023_03_10_09_02&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_-a1e4724922-%5BLIST_EMAIL_ID%5D.

- Reuter, Ora John. 2017. The Origins of Dominant Parties: Building Authoritarian Institutions in Post-Soviet Russia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Reuter, Ora John, and Graeme B. Robertson. 2015. “Legislatures, Cooptation, and Social Protest in Contemporary Authoritarian Regimes.” The Journal of Politics 77 (1): 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1086/678390.

- Robertson, Graeme B. 2009. “Managing Society: Protest, Civil Society, and Regime in Putin’s Russia.” Slavic Review 68 (3): 528–547. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0037677900019719.

- Sakwa, Richard. 2012. “Party and Power: Between Representation and Mobilisation in Contemporary Russia.” East European Politics 28 (3): 310–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2012.683784.

- Schedler, Andreas, ed. 2006. Electoral Authoritarianism: The Dynamics of Unfree Competition. Boulder, CO: L. Rienner Publishers, Inc.

- Smyth, Regina. 2022. “State Intervention and Russia’s Frozen Dominant Party System.” In Vol. 2.Routledge Handbook of Russian Politics and Society, edited by Graeme J. Gill. 127–137. 2nd ed. London/New York: Routledge.

- Soest, Christian von, and Julia Grauvogel. 2017. “Identity, Procedures and Performance: How Authoritarian Regimes Legitimize Their Rule.” Contemporary Politics 23 (3): 287–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2017.1304319.

- Stone, Philip J., Dexter C. Dunphy, Marshall S. Smith, and Daniel M. Ogilvie. 1966. The General Inquirer: A Computer Approach to Content Analysis. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- White, David. 2012. “Re-Conceptualising Russian Party Politics.” East European Politics 28 (3): 210–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2012.688815.